Abstract

Objective

Exposure to interpersonal violence is a known risk factor for psychopathology. However, it is unclear whether there are sensitive periods when exposure is most deleterious. We aimed to determine if there were time-periods when physical or sexual violence exposure was associated with greater child psychopathology.

Method

This study (N=4,580) was embedded in Generation R, a population-based prospective birth-cohort. Timing of violence exposure, reported through maternal reports (child age=10 years) was categorized by age at first exposure, defined as: very early (0–3 years), early (4–5 years), middle (6–7 years), and late childhood (8+ years). Using Poisson regression, we assessed the association between timing of first exposure and levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms, using the Child Behavior Checklist at age 10.

Results

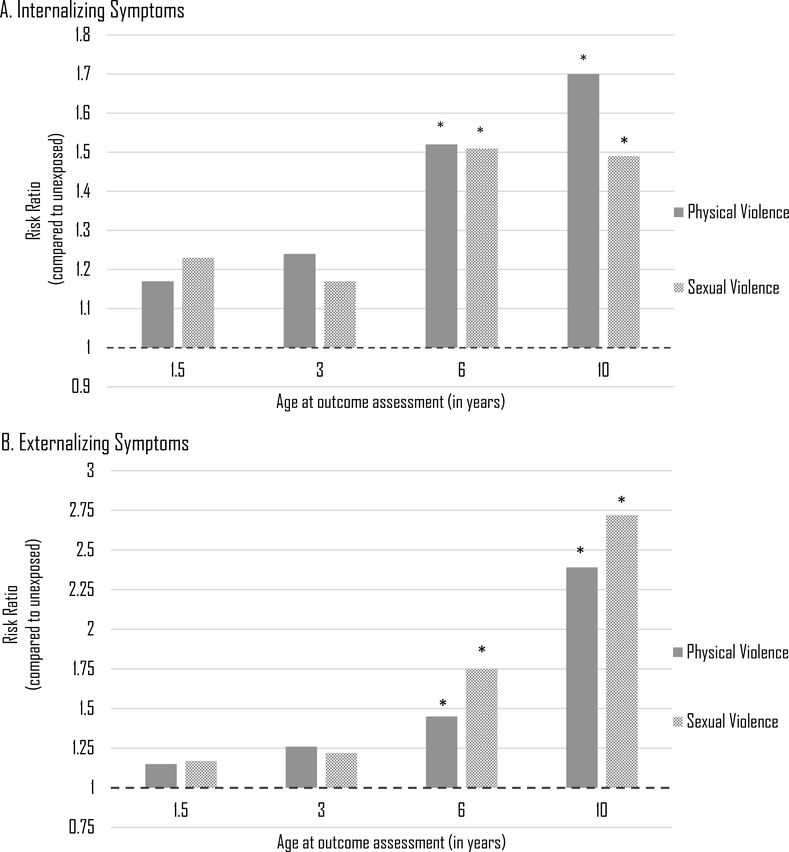

Violence exposure at any age was associated with higher internalizing (physical violence: RR=1.46, p<0.0001; sexual violence: RR=1.30, p<.0001) and externalizing symptoms (physical violence: RR=1.52, p<0.0001; sexual violence: RR=1.31, p=0.0005). However, the effects of violence were time-dependent: compared to children exposed at older ages, children first exposed during very early childhood had greater externalizing symptoms. Sensitivity analyses suggested that these time-based differences emerged slowly across ages 1.5, 3, 6 and 10, showing a latency between onset of violence exposure and emergence of symptoms, and were unlikely explained by co-occurring adversities.

Conclusion

Interpersonal violence is harmful to childhood mental health regardless of when it occurs. However, very early childhood may be a particularly sensitive period when exposure results in worse psychopathology outcomes. Results should be replicated in fully prospective designs.

Keywords: interpersonal violence, sensitive periods, psychopathology, children, latency

Introduction

Across multiple disciplines, there is a long-standing belief that there are windows of time when experiences can have lasting effects on behavior, health, and risk for disease.1,2 During these “sensitive periods”, specific exposure events that coincide with peak periods of brain development1,3 are posited to shape brain structure and function more than the same exposure occurring earlier or later in the lifecourse.4 These sensitive periods can therefore be conceptualized both as “high-risk” periods when adverse experiences, including exposure to stress or other types of adversity, are most potent in conferring risk to disease – but also “high-reward” periods when enriching experiences, including interventions, could be even more beneficial in promoting long-term positive health outcomes.

Despite widespread belief in the existence of sensitive periods regulating the etiology and course of mental health problems, there are not yet clearly identified sensitive periods linking experiences after birth to risk for psychopathology. To date, the most thorough work to identify postnatal sensitive periods in humans comes from observational studies that have examined the time-dependent effect of different forms of child exposure to interpersonal violence, as interpersonal violence exposure is known to substantially increase risk for later internalizing5–8 and externalizing7,9,10 problems. However, these prior observational studies on the time-dependent effects of interpersonal violence have generally yielded mixed results within both population-based and high-risk samples. Some studies comparing the effect of age at first exposure to violence have found that maltreatment early in childhood, defined previously as before age 5 or age 12, is associated with greater risk for psychopathology11–15 compared to exposure at latest stages. For example, a prospective study of 578 children by Keiley and colleagues of maternal-reported maltreatment found that children maltreated between ages 0 and 5 had significantly higher teacher-reported internalizing and externalizing symptoms by early adolescence, compared to unexposed children and children exposed between ages 6 and 9.14 However, other studies have found that a first experience of maltreatment later in childhood, meaning after age 10 or during adolescence, was associated with more substantially increased psychopathology risk.16–18 For instance, a prospective study by Thornberry and colleagues compared the effect of maltreatment across childhood on behavioral problems in 738 late-adolescents; maltreatment in adolescence led to 13% increased odds of internalizing problems and 35% increased odds of externalizing problems, whereas maltreatment during early or late childhood conferred no increased behavioral risk.18 Furthermore, other studies have found no differential effects on psychopathology symptoms based on the developmental timing of exposure.19–24 For example, among 4,361 youth followed across childhood, the timing of exposure to cumulative adversity in four developmental periods did not differentially impact internalizing or externalizing symptoms.23

These mixed findings contrast those obtained from a seminal experimental study, which followed very young Romanian orphan children who were randomized to high-quality foster care or continued institutionalized care; this study has demonstrated the wide ranging negative effects of institutionalized care in the first years of life on multiple outcomes, including less secure attachment, lower cognitive performance, and higher rates of psychiatric disorders.25 Although hard to directly compare a randomized control trial and a specific form of early deprivation to any observational study, results from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project underscore the salience of very early childhood adversity on a host of later outcomes in childhood and beyond. These collective set of mixed observations from human studies on the importance of the developmental timing of violence, deprivation, or other types of interpersonal adversity conflict with numerous animal studies, which have generally found more consistent time-dependent effects of different forms of social adversity on a range of outcomes, including not only anxious and depressive symptoms,26 but also social, emotional, and behavioral processes (e.g., fear conditioning, stress reactivity, aggressive behavior)27–29 and brain structure and function.30,31

The current study aimed to increase knowledge on sensitive periods shaping risk for psychopathology by exploring the relationship between the developmental timing of exposure to physical and sexual violence on child internalizing and externalizing symptoms measured at age 9 using data from a unique population-based sample of children. We focused on physical and sexual violence because these two types of exposures are most consistently linked to subsequent mental health and psychosocial functioning, potentially due to their interpersonal nature and serving as a possible indicator of a violent family environment.32–34 Identification of sensitive periods when these two common forms of violence increase susceptibility to psychopathology symptoms could provide important new clues into when and through what pathways psychopathology emerges and ultimately help determine when to optimally time interventions to reduce the consequences of exposure to adversity.

Method

Sample and Procedures

Data came from Generation R, a population-based prospective study of children followed from fetal life onwards in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The goal of Generation R was to examine the social, biological, and environmental factors shaping child growth, health, and development. Details about the cohort have been described elsewhere.35–38 In brief, 9,778 mothers living in Rotterdam at the time of their estimated delivery date (between April 2002 and January 2006) were enrolled during their first prenatal visit, at the birth visit, or in the first few months post-childbirth. Following the prenatal visit, mothers and their offspring were eligible to participate in two additional data collection periods completed via in-person structured interviews at the Generation R study center at child age 10. Ethical approval of the study was obtained by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam and the study was conducted in accordance with World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

The current study is based on an analytic subsample of 4,580 children whose caregivers (95.7% of whom were mothers) completed the age 10 assessment and had complete exposure and outcome data (n=7,393 caregivers completed the age 10 assessment, representing 86.5% of the 8,548 caregivers contacted). Children were excluded from the subsample due to incomplete exposure data (24.6%; n=1,822), incomplete outcome data (12.9%; n=953), or unreliable answers due to language barriers (0.51%; n=38). Although the reasons for data missingness were not recorded, data were missing because the child either did not present for the interview or the day-long data collection session ran late (and thus the self-reported sections of the interview where this data came from were skipped). Children included in our analytic sample (N=4,580) did not differ from those who were excluded (n=2,813) with respect to age, race/ethnicity, sex, and poverty level. However, the excluded sample comprised more children from families living in rural areas (23.1% versus 14.8%; p=0.05) and mothers with less than a high school education (26.6% versus 15.4%; p<0.01).

Measures

Childhood Adversity

Children’s exposure to physical and sexual violence was determined using a major life events inventory, which asked mothers to indicate whether the child had experienced specific life events at child age 10. The interview in Generation R was based on questionnaires previously used in the TRAILS study and on items in the Life Event and Difficulty Schedule (LEDS).s39,40 The TRAILS self-report questionnaires were changed to an interview format with a caregiver to allow the opportunity for discussion between participant and interviewer. Exposure to physical violence was defined based on two items: “someone threatened violence to the child” or “someone was violent to the child”. Exposure to sexual violence was also defined based on two items, translated as follows: “someone made sexual comments or gestures to the child” or “the child was subject to inappropriate sexual misconduct”. Children were coded as exposed to physical violence if either or both items were endorsed. Similarly, children were coded as exposed to sexual violence if either or both items were endorsed.

Among children exposed to either type of violence, mother’s reported the age (in years) of the child when the event happened. For events occurring multiple times, the interviewer recorded the age at worst or most negative occurrence. The decision to collect the date information in this format was based on a small pilot study suggesting that mothers could not reliably report the exact time of the first occurrence of a series of multiple events, but reliably could remember severe events. If all instances of exposure to violence were of equal severity, the interviewer recorded the age at first occurrence. Using this data, we categorized children as exposed to violence in one of the following developmental time periods; our age groupings were defined to balance sample size across age groups, as well as maintain general consistency with prior studies,4,13,23 and accepted definitions of developmental stages. These developmental stages were thus defined here as: very early childhood (age 0–3), early childhood (age 4–5), middle childhood (age 6–7), and late childhood (ages 8+). When both items corresponding to a specific violence type were endorsed, age at event occurrence was defined based on the earlier of the two ages reported. Although a limitation of this approach is that we are unable to consistently classify age of exposure with respect to its severity, it does enable us to include all children in the analysis who have been exposed to both violence events. Importantly, among children exposed to both forms of violence within a given type, reported age at exposure for each form were comparable, suggesting that the classification by developmental stage is unlikely to be inconsistent with respect to severity of exposure (see Table S1, available online). Prior studies have also shown that caregiver retrospective reporting of their young child’s adversity exposure is generally accurate,41 and using developmental periods, rather than specific ages, reduces potential recall bias compared to exposures focused on single ages.

Outcomes: Child Psychopathology Symptoms

Mothers completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/6–18)42 at the child age 10 assessment.43 Using a 3-point scale (0=not true; 1=sometimes true; 2=very true or often true), mothers rated their child’s behavior on 51 items that comprise both internalizing and externalizing behavior. We analyzed raw total scores from the Internalizing (Cronbach’s α=0.88) and Externalizing subscales (Cronbach’s α=0.91), the two main classification schemes for child psychopathology symptoms.44 Subscales included in these broadband scales are summarized in supplemental material (Measures in Supplement 1, available online).

Covariates

All models controlled for the following covariates, measured closest to the time of the child’s birth: child sex, child race/ethnicity, gestational birth status, household income, highest level of maternal education, parental marital status, and maternal psychopathology symptoms (see Measures in Supplement 1, available online). The covariates were included because they were found in our study to be potential confounders or are routinely included in birth cohort studies of child health outcomes.45,46 For example, maternal psychopathology symptoms measured at the time of the child’s birth using the Global Severity Index derived from the Brief Symptom Inventory47 were included to reduce potential impacts of both confounding and common rater bias,48 as mothers reported about their child’s emotional and behavioral problems, mothers were the primary reporters of their child’s exposure to adversity, and maternal mood or other factors may influence reports of adversity exposure49 and psychopathology.50,51 Of note, we did not adjust for co-occurring violence exposure (meaning adjustment for sexual violence when examining the role of physical violence and vice versa), due to their lack of strong overlap (Measures in Supplement 1, available online).

In our analytic sample of 4,580 children, missingness for each covariate ranged from 1.0% (n=47) for race/ethnicity, to 5.7% (n=263) for maternal education, 6.2% (n=284) for marital status, 19.4% (n=889) for income, and 23.0% (n=1,054) for maternal psychopathology; there was no missing data for child sex and gestational birth age. Prior to analysis, we imputed missing covariate data using the MI procedure in SAS, creating 25 imputed datasets in order to reduce bias associated with missing data.52 The reported regression results were obtained by pooling estimates from the 25 multiply imputed datasets with the MIANALYZE procedure (further details on Missingness and Multiple Imputation in Supplement 2, available online).

Analysis

We performed univariate analyses to determine the prevalence of exposure to each type of violence and the distribution of violence exposure by covariates. We then estimated two pairs of multiple Poisson regression models with robust standard errors, corresponding to each type of exposure and outcome. We modeled these associations with a Poisson variable, due to the large number of children with no symptoms, which was coded as an outcome value of zero (internalizing symptoms n=682, 14.9%; externalizing symptoms n=1,202, 26.2%). We also modeled these associations using robust standard errors, given the over-dispersion in raw symptom scores (internalizing symptoms mean=4.73, SD=4.9; externalizing symptoms mean=3.85, SD=4.8).

In Model 1, we estimated the effect of exposure to each type of violence (vs. unexposed) on internalizing and externalizing symptoms, after adjusting for covariates. In Model 2, we estimated the effect of the developmental timing of exposure to violence (vs. unexposed) on each CBCL score, adjusting for covariates. For Model 2, we used omnibus tests of homogeneity to evaluate whether the beta coefficients (indicating the effect of age at exposure compared to unexposed) for the developmental time periods (very early childhood, early childhood, middle childhood, and late childhood) were significantly different from each other. For these tests, the null hypothesis is that the covariate only model is preferred to the developmental timing model, and the alternative hypothesis is that the developmental timing variable significantly improves the model fit. When the omnibus test for homogeneity was rejected (the null hypothesis was that the beta coefficients corresponding to each age at exposure were equal; two-sided p-value<.05), we conducted post-hoc Tukey tests to determine if there were pair-wise differences between the developmental time period effects, adjusting for multiple testing. All data analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

The mean age of the analytic sample was 9.7 years (SD=0.3). As shown in Table 1, the analytic sample was approximately half girls (50.7%), and mostly Dutch (65.5%). The sample varied with respect to maternal education (52.0% had mothers with middle-high to high education) and household income level (53.5% had high income), with the majority of mothers reporting either being married (46.8%) or living with a partner (37.9%). Most children were born full term (93.3%). Maternal psychopathology symptoms varied (mean Global Severity Index=0.24, SD=0.31), with 8.3% of mothers reporting severe psychological distress.

Table 1.

Distribution of Baseline Covariates in the Total Analytic Sample and by Exposure to Violence and Child Emotional/Behavior Problem Scores in the Generation R Analytic Sample (N=4,580)

| Total Sample | Exposed to Physical Violence | Exposed to Sexual Violence | Internalizing CBCL | Externalizing CBCL | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | p | n | % | p | Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD | p | |

| Covariates | ||||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.799 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Male Participants | 2,259 | 49.32 | 482 | 21.34 | 75 | 3.32 | 4.71 | 5.05 | 4.42 | 5.27 | ||||

| Female Participants | 2,321 | 50.68 | 250 | 10.77 | 136 | 5.86 | 4.74 | 4.78 | 3.31 | 4.21 | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.009 | 0.158 | 0.001 | 0.054 | ||||||||||

| Dutch | 3,000 | 65.50 | 453 | 15.10 | 128 | 4.27 | 4.62 | 4.87 | 3.75 | 4.62 | ||||

| Non-Dutch European | 355 | 7.75 | 52 | 14.65 | 23 | 6.48 | 4.22 | 4.51 | 3.73 | 5.00 | ||||

| Non-Dutch Non-European | 1,178 | 25.72 | 222 | 18.85 | 56 | 4.75 | 5.13 | 5.11 | 4.14 | 5.11 | ||||

| Maternal Education | <0.001 | 0.097 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| High | 1,316 | 28.73 | 152 | 11.55 | 45 | 3.42 | 4.20 | 4.39 | 3.42 | 4.38 | ||||

| Mid-High | 1,064 | 23.23 | 167 | 15.70 | 44 | 4.14 | 4.68 | 4.68 | 3.81 | 4.64 | ||||

| Mid-Low | 1,290 | 28.17 | 244 | 18.91 | 66 | 5.12 | 4.83 | 5.09 | 3.97 | 4.82 | ||||

| Low | 647 | 14.13 | 133 | 20.56 | 35 | 5.41 | 5.50 | 5.49 | 4.43 | 5.42 | ||||

| Household Income Level | <0.001 | 0.009 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| High | 2,448 | 53.45 | 334 | 13.64 | 90 | 3.68 | 4.27 | 4.39 | 3.45 | 4.25 | ||||

| Middle | 697 | 15.22 | 138 | 19.80 | 41 | 5.88 | 4.96 | 5.17 | 4.15 | 5.35 | ||||

| Low | 545 | 11.90 | 107 | 19.63 | 32 | 5.87 | 5.83 | 5.86 | 4.66 | 5.60 | ||||

| Maternal Marital Status | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Married | 2,145 | 46.83 | 300 | 13.99 | 87 | 4.06 | 4.51 | 4.69 | 3.43 | 4.35 | ||||

| Living Together | 1,734 | 37.86 | 294 | 16.96 | 63 | 3.63 | 4.67 | 4.70 | 3.93 | 4.70 | ||||

| No Partner | 416 | 9.08 | 102 | 24.52 | 38 | 9.13 | 6.15 | 6.37 | 5.49 | 6.36 | ||||

| Gestational Birth Status | 0.080 | 0.525 | 0.610 | 0.635 | ||||||||||

| Full Term | 4,271 | 93.25 | 694 | 16.25 | 194 | 4.54 | 4.72 | 4.89 | 3.84 | 4.79 | ||||

| Pre-Term | 309 | 6.75 | 38 | 12.30 | 17 | 5.50 | 4.86 | 5.26 | 3.98 | 4.86 | ||||

| Maternal Psychopathology | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Absent | 4,201 | 91.72 | 624 | 14.85 | 180 | 4.28 | 4.51 | 4.69 | 3.69 | 4.60 | ||||

| Present | 379 | 8.30 | 108 | 28.50 | 31 | 8.18 | 7.10 | 6.47 | 5.68 | 6.29 | ||||

Note: Descriptive statistics are presented for the analytic sample without imputation. Simple linear regressions were performed for each covariate by each exposure and outcome with p-values reported. Maternal education: High (University), Mid-high (Some higher education), Mid-low (Secondary), Low (Primary/some secondary). Household income level: High (>2,200 Euros/month), Middle (1,400–2,200 Euros/month), Low (<1,400 Euros/month). Maternal psychopathology was assessed using a global severity score of psychological distress reported at the time of the child’s birth; presence was defined as the top 90th percentile while absence was defined as anything lower. In our analysis, we controlled for continuous symptoms to allow for greater variation. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist.

Physical violence exposure was reported in 16.0% of the cohort while sexual violence was reported in 4.6%. Physical and sexual violence exposure were weakly correlated with one another (tetrachoric correlation=0.27; p<0.001).

As shown in Table 1, physical violence was more commonly reported for boys, with 21.3% of boys experiencing physical violence compared to 10.8% of girls. In contrast, sexual violence was more commonly reported for girls, with 5.9% of girls experiencing sexual violence compared to 3.3% of boys. The prevalence of exposure to physical violence was higher among children from minority racial or ethnic groups, and children who had lower socioeconomic status, mothers with no partner, and mothers with a history of psychopathology. The prevalence of exposure to sexual violence also differed by household income level, maternal marital status, and maternal psychopathology, but not by race/ethnicity, maternal education, or gestational age (all p<0.05).

Both internalizing and externalizing symptoms were higher among children who were non-Dutch, non-European, whose mothers had less education, less household income, lived in a household with no partner present, and had a history of maternal psychopathology (all p<0.05) (Table 1). Boys had higher externalizing symptoms compared to girls (p<0.0001), while internalizing symptoms did not significantly differ between boys and girls (p=0.80).

The distribution of age at first or worst exposure to violence is displayed in Table 2. As shown, both physical and sexual violence exposure was most commonly reported as having occurred recently, during late childhood (8+ years old) (60.0% and 46.0% of exposure occurring in this age group, respectively).

Table 2.

Age at Exposure to Violence (N=4,580)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Violence | ||

| Ever Exposed | 732 | 15.98 |

| Age at First or Worst Exposure | ||

| Very Early Childhood (0–3) | 31 | 4.23 |

| Early Childhood (4–5) | 66 | 9.02 |

| Middle Childhood (6–7) | 196 | 26.78 |

| Late Childhood (8+) | 439 | 59.97 |

| Sexual Violence | ||

| Ever Exposed | 211 | 4.61 |

| Age at First or Worst Exposure | ||

| Very Early Childhood (0–3) | 13 | 6.16 |

| Early Childhood (4–5) | 43 | 20.38 |

| Middle Childhood (6–7) | 58 | 27.49 |

| Late Childhood (8+) | 97 | 45.97 |

Note: The first row, labeled exposed, indicates the lifetime prevalence of exposure to violence. The remaining rows indicate the age at first or worse exposure in years.

Exposure to Violence and Child Psychopathology Symptoms

Children exposed to either type of violence had significantly higher internalizing and externalizing symptoms relative to their peers who were never exposed (Table 3). Specifically, exposure to physical violence was associated with 1.46 times higher risk of internalizing symptoms (RR=1.46, 95% CI=1.36, 1.57) and 1.52 times higher risk of externalizing symptoms (RR=1.52, 95% CI=1.39, 1.67), after adjusting for covariates. Additionally, exposure to sexual violence was associated with 1.30 times higher risk of internalizing symptoms (RR=1.30, 95% CI=1.15, 1.45) and 1.31 times higher risk of externalizing symptoms (RR=1.31, 95% CI=1.13, 1.52), after adjusting for covariates.

Table 3.

Association Between Violence Exposure and the Timing of Exposure to Violence on Child Emotional/Behavioral Problems at Age 10

| Internalizing Symptoms | Externalizing Symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | homogeneity p | RR | 95% CI | homogeneity p | |

| Physical Violence | ||||||

| Ever exposed | 1.46* | (1.36, 1.57) | 1.52* | (1.39, 1.67) | ||

| Timing of Physical Violence | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Very Early Childhood | 1.70* | (1.38, 2.12) | 2.39* | (1.84, 3.13) | ||

| Early Childhood | 1.73* | (1.38, 2.18) | 1.63* | (1.27, 2.12) | ||

| Middle Childhood | 1.45* | (1.28, 1.65) | 1.40*a | (1.21, 1.63) | ||

| Late Childhood | 1.40* | (1.28, 1.54) | 1.49*a | (1.34, 1.67) | ||

| Sexual Violence | ||||||

| Ever Exposed | 1.30* | (1.15, 1.45) | 1.31* | (1.13, 1.52) | ||

| Timing of Sexual Abuse | 0.004 | 0.028 | ||||

| Very Early Childhood | 1.49 | (0.99, 2.25) | 2.72* | (1.77, 4.18) | ||

| Early Childhood | 1.35* | (1.04, 1.75) | 1.23a | (0.83, 1.82) | ||

| Middle Childhood | 1.28* | (1.05, 1.57) | 1.20a | (0.90, 1.58) | ||

| Late Childhood | 1.25* | (1.06, 1.45) | 1.23*a | (1.02, 1.49) | ||

Note: Risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals are shown. Poisson regression models with robust standard errors are adjusted for household income, maternal education, race/ethnicity, gender, parental marital status, gestational birth status, and maternal psychopathology. The reference group for all models is unexposed, making each effect estimate an indicator of the effect of being exposed (at any time period or at a certain time period) relative to being never exposed. After tests of homogeneity, for which p-values are shown, post-hoc Tukey pairwise comparisons were estimated. Significant differences are shown using superscript letters as detailed below. Tukey pairwise comparisons may be non-significant even in cases of significant tests of homogeneity, as tests of homogeneity assess global differences across groups rather than two-way comparisons and Tukey p-values are adjusted for multiple comparisons. RR = risk ratio

Significantly different from very early childhood based on post-hoc Tukey test.

p < .05

Developmental Timing of Exposure to Violence and Child Psychopathology Symptoms

As indicated by the significant tests of homogeneity (all p<0.05), the effects of violence exposure on child psychopathology symptoms differed based on the age at first or worst exposure, especially for externalizing symptoms (Table 3).

Specifically, children exposed to physical violence in very early childhood had 2.39 times higher risk of externalizing symptoms (RR=2.39, 95% CI=1.84, 3.13), relative to unexposed children. Based on the Tukey two-way comparison, this effect of exposure during very early childhood (RR=2.39) was significantly larger than the effects of exposure during middle (RR=1.40) and late childhood (RR=1.49); see Table S2, available online, for all Tukey comparisons.

Similarly, children exposed to sexual violence in very early childhood also had significantly higher externalizing symptoms (RR=2.72, 95% CI=1.77, 4.18). This effect during very early childhood (RR=2.72) was also significantly larger than the effects of exposure at all later time periods (compared to early (RR=1.23), middle (RR=1.20), and late (RR=1.23) childhood); Tukey two-way comparison p<0.05).

No significant Tukey two-way comparisons were found for the effect of timing of physical or sexual violence on internalizing symptoms, despite the significant tests of homogeneity (p<0.05), which evaluates global differences across means of all groups rather than specific two-way comparisons. Tukey test p-values also adjust for multiple comparisons, thus are a more conservative test.

Sensitivity Analysis

Although these results are suggestive of a very early childhood sensitive period when violence exposure may be most harmful, they may also reflect the effects of adversity accumulation, as children exposed to violence during very early childhood could have been exposed for longer period of time and a greater duration of exposure could have contributed to higher psychopathology symptoms. To explore this possibility, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the impact of very early childhood exposure to violence on the development of psychopathology symptoms across early and middle childhood. Specifically, we compared the effect of violence exposure in very early childhood, relative to those never exposed at all time periods, on internalizing and externalizing symptoms assessed when the child was 1.5, 3, and 6 years of age (CBCL/1.5–553 and CBCL/6–1842). These repeated psychopathology symptom assessments across development allowed us to determine patterns in symptoms across childhood following exposure to violence in very early childhood and thus evaluate whether psychopathology symptoms emerged early in development. Of note, although the instruments vary in the specific items used to assess psychopathology,42 such differences reflect developmental competencies, making comparisons of elevated symptoms across time comparable.

Children exposed to violence during very early childhood generally did not have greater psychopathology symptoms at either age 1.5 or 3 years of age as compared to children who were unexposed to violence (Figure 1). However, at age 6, differences in psychopathology symptoms began to emerge. Internalizing symptoms were significantly higher at age 6 among children with very early childhood exposure to physical violence (RR=1.52 95% CI=1.14, 2.03) or sexual violence (RR=1.45, 95% CI=1.11, 1.88. Similarly, externalizing symptoms were significantly higher among children with very early childhood exposure to physical violence (RR=1.50 95% CI=1.03, 2.19) or sexual violence (RR=1.75, 95% CI=1.34, 2.29).

Figure 1. Effect of Violence Exposure in Very Early Childhood on Internalizing and Externalizing Behavioral Symptoms at Ages 1.5, 3, 6, and 10 Years Compared to Never Exposed.

Note: The figure displays the estimated risk ratios in behavioral symptoms at age 1.5, 3, 6 and 10 for exposure to violence in very early childhood (age 0–3) relative to children who were never exposed to violence. Results were derived from a set of Poisson regression models with robust standard errors, adjusting for covariates. Panel A presents the results for internalizing symptoms and Panel B presents the results for externalizing symptoms. Exposures are physical violence and sexual violence (as indicated by the key). The effect estimates shown here for age 10 were previously reported in Table 3.

*p < 0.05

Recognizing that childhood adversities often co-occur, we also conducted additional analyses to determine if the impact of physical and sexual violence in very early childhood may be due to the occurrence of other forms of adversity occurring during the same time period. For these analyses, we re-ran the primary analytic models to determine the impact of physical and sexual violence on psychopathology symptoms at age 10, after further adjustment for experiences of other very early childhood adversity exposures. The measure of other adversity exposure was derived as a count variable (ranging from 0–11) that captured the total number of other adversities reported during age 0 to 3 based on a list of 11 events that could have occurred at these ages (Measures in Supplement 1, available online).

Most of the sample (n=2,394, 52.3%) were unexposed to other adversities in the very early childhood period, meaning during the first three years of their life, with 1,422 (31.0%) exposed to one event, 362 (7.9%) to two events, and 95 (2.1%) to three or more events. Children exposed to any physical violence reported a greater number of other adversities in very early childhood compared to those with no physical violence exposure (mean=0.76; SD=0.9 vs. mean=0.54; SD=0.7, respectively, p<.0001). However, the number of reported other adversities did not differ between children exposed or unexposed to sexual violence (mean=0.64; SD=0.8 vs. mean=0.57; SD=0.8, respectively, p=0.21).

As shown in Table 4, the general pattern of findings mirrored the main findings, with very early childhood exposure to physical and sexual violence associating with higher externalizing symptoms, though as expected most effect estimates were attenuated slightly after adjusting for other very early adversities. For example, the magnitude effect of very early childhood physical violence on externalizing symptoms decreased from RR=2.39 (95% CI=1.84, 3.13) to RR=2.18 (95% CI=1.68, 2.93), adjusting for other very early adversities. However, despite such adjustments, exposure to both physical and sexual violence in very early childhood still conferred the greatest risk for externalizing symptoms when compared to children who were unexposed, as well as compared to those exposed at most later time periods.

Table 4.

Association Between Violence Exposure and the Timing of Exposure to Violence on Child Emotional/Behavioral Problems at Age 10, Adjusting for Burden of Other Adversity Exposure in Very Early Childhood

| Internalizing Symptoms | Externalizing Symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | homogeneity p | RR | 95% CI | homogeneity p | |

| Physical Violence | ||||||

| Ever exposed | 1.43* | (1.34, 1.55) | 1.49* | (1.36, 1.63) | ||

| Timing of Physical Violence | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Very Early Childhood | 1.55* | (1.25, 1.92) | 2.18* | (1.68, 2.93) | ||

| Early Childhood | 1.65* | (1.31, 2.08) | 1.57* | (1.22, 2.01) | ||

| Middle Childhood | 1.43* | (1.27, 1.63) | 1.39*a | (1.20, 1.62) | ||

| Late Childhood | 1.39* | (1.28, 1.52) | 1.48*a | (1.31, 1.65) | ||

| Sexual Violence | ||||||

| Ever Exposed | 1.27* | (1.14, 1.43) | 1.31* | (1.13, 1.52) | ||

| Timing of Sexual Abuse | 0.007 | 0.034 | ||||

| Very Early Childhood | 1.40 | (0.91, 2.16) | 2.59* | (1.68, 3.94) | ||

| Early Childhood | 1.36* | (1.04, 1.79) | 1.26 a | (0.85, 3.94) | ||

| Middle Childhood | 1.31* | (1.08, 1.58) | 1.23 a | (0.94, 1.62) | ||

| Late Childhood | 1.20* | (1.02, 1.40) | 1.20 a | (0.99, 1.45) | ||

Note: Risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals are shown. Poisson regression models with robust standard errors are adjusted for household income, maternal education, race/ethnicity, gender, parental marital status, gestational birth status, maternal psychopathology, and a count of other adversity exposure in very early childhood. A count of other adversity exposure in very early childhood was determined by counting the number of types of other events the child was exposed to during the same time period: child illness, household member illness, someone else close to the child experienced an illness, parent/caregiver death, death or someone else who was close to the child, unsafe neighborhood, financial problems, household experienced enduring conflict, divorce, parent job loss, and moved homes. The reference group for all models is unexposed, making each effect estimate an indicator of the effect of being exposed (at any time period or at a certain time period) relative to being never exposed. After tests of homogeneity, for which p-values are shown, post-hoc Tukey pairwise comparisons were estimated. Significant differences are shown using superscript letters as detailed below. Tukey pairwise comparisons may be non-significant even in cases of significant tests of homogeneity, as tests of homogeneity assess global differences across groups rather than two-way comparisons and Tukey p-values are adjusted for multiple comparisons. RR = risk ratio

Significantly different from very early childhood based on post-hoc Tukey test.

p < .05.

Additionally, effects from the primary models did not substantially change when excluding children whose mothers had severe psychological distress (Table S3, available online).

Discussion

The main finding from this study is that very early childhood, here defined as the time period from birth to the third birthday, may be a sensitive period when exposure to interpersonal violence is associated with the greatest risk for psychopathology symptoms in later childhood. These results did not appear to be explained by a greater number of exposures to multiple types of adversity. That is, even after controlling for the effects of exposure to other co-occurring early life adversities, we continued to see a heightened risk for psychopathology symptoms at age 10 among children exposed to physical and sexual violence during very early childhood compared to children who were never exposed to these types of violence.

These results are consistent with findings from a randomized control trial on the effects of institutional care in young children25,54 and both prospective12,14 and retrospective55 epidemiological studies showing that adversity exposure before age 5 is most associated with risk for child psychopathology symptoms. Our findings are also consistent with studies of rodents and primates in showing the existence of sensitive periods, particularly shortly after birth, when parental care disruptions and other environmental inputs produce worse outcomes across social, emotional, behavioral and biological processes domains.28,31,56

There are a number of reasons why exposure to interpersonal violence in the first three years of life could be more harmful than later violence exposure. From the perspective of developmental psychopathology theories,57 early violence exposure likely compromises a child’s ability to successfully master early stage-salient developmental tasks, such as self-regulation or the development of secure attachments, which in turn hinders the ability to master subsequent developmental tasks. Moreover, according to developmental neuroscience, early life adversities may be more deleterious because they occur when the foundation of brain architecture and neurobiological systems involved in regulating arousal, emotion, stress responses, and reward processing are being wired.58,59 Exposure to violence early in life can therefore disrupt the development of neural circuits that interfere with typical patterns of brain development, heightening vulnerability to a variety of mental health problems.60–63 Thus, “early life” adversity likely predicts a cascade of many negative consequences.

Although the general pattern of findings did not differ between physical and sexual violence, there may be different risk factors associated with each form of violence and thus more long-term consequences associated with each type of violence.64 For example, low maternal involvement and perinatal problems are found to increase risk for physical abuse, while being female and living with a stepfather increases risk for sexual abuse.64 Therefore, physical and sexual violence in very early childhood may be associated with different patterns of risk factors and differentially comorbid with other adversities.

We also found evidence suggesting that the behavioral effects of these sensitive period may not emerge immediately. Specifically, early psychopathology symptoms scores, measured at age 1.5 and 3, were generally indistinguishable across children with versus without exposure to interpersonal violence during very early childhood. However, at age 6, significant differences in psychopathology symptoms began to emerge between the very early childhood exposed and never exposed groups; these differences then persisted to age 10.

There are a number of possible explanations for such findings. First, the lack of observable differences between exposed and non-exposed groups in psychopathology symptoms at ages 1.5 and 3 could reflect challenges inherent to measuring psychopathology symptoms in very young children. The limited ability for young children to articulate their emotional states requires the use of assessments largely based on observation.65 Age-related variation in the manifestation of symptoms across development have also been noted.44

Second, the lack of early differences across exposure groups could also suggest that the consequences of adversity during a sensitive period may not be immediately detectable, but rather that there may be a lag in time or latency period from the occurrence of exposure to presentation of behavioral symptoms. Curiously, there is little evidence from either empirical research or theoretical work to pin-point exactly when symptoms would be expected to emerge following stress exposure. For example, studies on the effects of interpersonal stress, including child physical or sexual abuse, on risk for depression have shown that the time from onset of stress to the occurrence of depression could vary from a period of several months,66–68 to a few years,69 and even up to a decade.8,70

The strongest evidence available addressing this question comes from studies of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which distinguish between immediate (e.g., within days to three months following trauma exposure) and delayed-onset (e.g., six months or more following trauma) responses of symptom onset following trauma exposure.71,72 Epidemiological studies suggest that the majority of young people exposed to trauma who develop PTSD will manifest symptoms within six months.73,74 In children and adolescents, the timing and presentation of PTSD symptoms following acute trauma depends in part on level of developmental maturation of brain structures, functional physiological correlates, and cognitive and emotional regulation.71

However, the notion of a delayed “time to impact” associated with exposure to adversity during sensitive periods is consistent with work from animal studies on the neural underpinnings of critical periods, which have found that the effects on behavior of early postnatal experience do not occur immediately, but rather gradually over time.75 Andersen and Teicher76 have also specifically posited that the expression of symptoms resulting from exposure to adversity during earlier-life sensitive periods may only manifest later in life, such as during adolescence, when specific maturational events occur that trigger the presentation of symptoms among vulnerable individuals. Their hypothesis is consistent with the notion of a “latent vulnerability”, wherein exposure to maltreatment is thought to cause alterations across neurobiological systems that are at first adaptive, but later prove harmful in navigating subsequent experiences outside of the maltreatment environment.77

A third possibility for the lack of observable differences in psychopathology symptoms at ages 1.5 and 3 could be based on how violence and other co-occurring adversities accumulate across time. Accumulation of risk models propose that every additional year of exposure (or greater levels of exposure to multiple adversities across time) increase risk of poor health in a dose-response manner.78,79 Although there were no measures available in this dataset that would allow us to determine if children were exposed to violence repeatedly, it is possible that children experiencing violence early had more chronic exposure to violence and other adversities. Indeed, violence exposure is often correlated with other environmental risk factors, suggesting that very early violence exposure may be indicative of a dysfunctional home environment. Descriptive analyses somewhat hinted at this possibility (see Table S1, available online, for distribution of covariates by age at exposure to violence). Thus, as children age, the effects of violence could accumulate, increasing risk of psychopathology symptoms in an additive fashion.

This study had several strengths. Data came from a large population-based sample of youth, enabling us to obtain more generalizable results as compared to clinical or community-based samples. Although interpersonal violence was retrospectively assessed via maternal reports at child age 10, we were able to leverage the longitudinal nature of this large birth cohort to investigate the development of psychopathology symptoms across early to late childhood, as internalizing and externalizing symptoms were measured repeatedly during the study (at child age 1.5, 3, 6, and 10 years old).

However, there are several limitations. First, exposure to violence was assessed retrospectively at age 10 via maternal self-report. Although prospective reports may be more reliable and valid than retrospective reports, especially in recording information about the age at exposure, both retrospective and prospective study designs are vulnerable to under-reporting with parental self-reporters, who may be reluctant to disclose such personal matters, especially if they are implicated in their occurrence.41 Yet, even if such reporting biases were present, prior work has shown that retrospective and prospective measures produce similar estimates of association with mental disorders,81 suggesting that adversity exposure is detected as harmful regardless of ascertainment strategy. Exposure measures were also derived from only four items, which could affect the precision of these estimates. However, the prevalence estimates of exposure to physical (16%) and sexual violence (5%) derived here were comparable to estimates obtained from nationally-representative epidemiological samples of youth across the globe.82,83 Potentially key features of adversity were also not measured in Generation R, including the severity, chronicity, or duration of violence and the relationship of the child to the perpetrator of violence. Other forms of interpersonal violence, such as neglect or emotional abuse, were also unmeasured. There was also a small number of children exposed to sexual violence in very early childhood (n=13), suggesting that these findings should be interpreted with caution. Further, despite the rich cohort data, there may be additional unmeasured factors, such as relationships with siblings, parental divorce, presence of a non-biological parent caregiver, or other indicators of cumulative environmental risk that could confound the relationship between violence exposure and behavioral symptoms. Of note, however, we did not find a strong relationship between maternal reports of her own exposure to violence and her reporting of children’s violence exposure (correlations ranged from 0.04–0.14), suggesting that these findings were not explained by maternal problems. Finally, there was also attrition over time, which we attempted to address using multiple imputation.

In summary, results from this study suggest that even though exposure to violence is harmful across childhood, it may be particularly damaging when it occurs before age 3. These insights could be used to guide the tailoring of screening efforts to improve detection of experiences of adversity among all children, but especially among the youngest children who may be the most vulnerable. They may also be used to help guide policy decisions and the allocation of limited resources towards children most in need.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01MH102403 (Dunn) and 1R01MH113930 (Dunn). A. Neumann and H. Tiemeier are supported by a grant of the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO grant No. 024.001.003, Consortium on Individual Development). The work of H. Tiemeier is further supported by a European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Contract grant number: 633595, DynaHealth) and a NWO-VICI grant (NWO-ZonMW: 016.VICI.170.200). C.C. is supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant ref: ES/N001273/1). The Generation R Study is conducted by the Erasmus Medical Center in close collaboration with the Erasmus University Rotterdam, Faculty of Social Sciences, the Municipal Health Service Rotterdam area, and the Stichting Trombosedienst and Artsenlaboratorium Rijnmond (STAR), Rotterdam. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of general practitioners, hospitals, midwives and pharmacies in Rotterdam. The Generation R Study is made possible by financial support from: Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Social Media

Facebook: Study using @GenerationR_010 data finds time-dependent effects of exposure to interpersonal violence. Children exposed during very early childhood had greater externalizing symptoms than children who were exposed at older ages. These findings suggest the first three years of life may be a sensitive period when exposure to adversity is most harmful #sensitiveperiod <link to article placeholder>

Twitter: New study finds the effects of interpersonal violence were time-dependent suggesting a sensitive period in very early childhood @GenerationR_010 @ErinDunnScD @CAM_Cecil #sensitiveperiod <link to article placeholder>

References

- 1.Knudsen E Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16:1412–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bornstein MH. Sensitive periods in development: Structural characteristics and causal interpretations. Psychol Bull. 1989;105(2):179–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey DB, Bruer JT, Symons FJ, Lichtman JW, eds. Critical thinking about critical periods. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Publishing Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn EC, McLaughlin KA, Slopen N, Rosand J, Smoller JW. Developmental timing of child maltreatment and symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation in young adulthood: results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30(10):955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn EC, Gilman SE, Willett JB, Slopen N, Molnar BE. The impact of exposure to interpersonal violence on gender differences in adolescent-onset major depression: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29:392–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication II: Associations with persistence of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):124–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of chilhood abuse and household dysfunction in many of the leading causes of death in adults: the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14:245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication I: Associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahl SK, Larsen JT, Petersen L, et al. Early adversity and risk for moderate to severe unipolar depressive disorder in adolescence and adulthood: A register-based study of 978,647 individuals. Journal of affective disorders. 2017;214:122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duprey EB, Oshri A, Caughy MO. Childhood Neglect, Internalizing Symptoms and Adolescent Substance Use: Does the Neighborhood Context Matter?(Clinical report). Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2017;46(7):1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplow JB, Widom CS. Age of onset of child maltreatment predicts long-term mental health outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(1):176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keiley MK, Howe TR, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Petti GS. The timing of child physical maltreatment: a cross-domain growth analysis of impact on adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(4):891–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thornberry TP, Henry KL, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The causal impact of childhood-limited maltreatment and adolescent maltreatment on early adult adjustment. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(4):359–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harpur LJ, Polek E, van Harmelen AL. The role of timing of maltreatment and child intelligence in pathways to low symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescence. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;47:24–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proctor LJ, Skriner LC, Roesch S, Litrownik AJ. Trajectories of behavioral adjustment following early placement in foster care: Predicting stability and change over 8 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(5):464–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thornberry TP, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The importance of timing: the varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(4):957–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn EC, Soare TW, Raffeld MR, et al. What life course theoretical models best explain the relationship between exposure to childhood adversity and psychopathology symptoms: recency, accumulation, or sensitive periods? Psychological Medicine. 2018;48(15):2562–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.English DJ, Graham JC, Litrownik AJ, Everson M, Bangdiwala SI. Defining maltreatment chronicity: are there differences in child outcomes? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(5):575–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaffee SR, Maikovich-Fong AK. Effects of chronic maltreatment and maltreatment timing on children’s behavior and cognitive abilities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52(2):184–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oldehinkel AJ, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Nederhof E. Childhood adversities and adolescent depression: a matter of both risk and resilience. Dev Psychopathol. 2014;26(4 Pt 1):1067–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slopen N, Koenen KC, Kubzansky LD. Cumulative adversity in childhood and emergent risk factors for long-term health. Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;164(3):631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoon S Child maltreatment characteristics as predictors of heterogeneity in internalizing symptom trajectories among children in the child welfare system. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2017;72:247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson CA, Furtado EA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH. The Deprived Human Brain: Developmental deficits among institutionalized Romanian children—and later improvements—strengthen the case for individualized care. American Scientist. 2009;97(3):222–229. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raineki C, Cortes MR, Belnoue L, Sullivan RM. Effects of early-life abuse differ across development: infant social behavior deficits are followed by adolescent depressive-like behaviors mediated by the amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(22):7758–7765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmes A, le Guisquet AM, Vogel E, Millstein RA, Leman S, Belzung C. Early life genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors shaping emotionality in rodents. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29:1335–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez M, Ladd CO, Plotsky PM. Early adverse experience as a developmental risk factor for later psychopathology: evidence from rodent and primate models. Development and psychopathology. 2001;13(03):419–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veenema AH. Early life stress, the development of aggression and neuroendocrine and neurobiological correlates: What can we learn from animal models. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2009;30:497–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Dietz K, DeLoyht JM, et al. Impaired adult myelination in the prefrontal cortex of socially isolated mice. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15(12):1621–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makinodan M, Rosen KM, Ito S, Corfas G. A critical period for social experience-dependent oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination. Science. 2012;337:1357–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DePrince AP, Weinzierl KM, Combs MD. Executive function performance and trauma exposure in a community sample of children. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2009;33(6):353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindert J, von Ehrenstein OS, Grashow R, Gal G, Braehler E, Weisskopf MG. Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: Systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Public Health. 2014;59(2):359–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Price-Robertson R, Rush P, Wall L, Higgins D. Rarely an isolated incident: Acknowledging the interrelatedness of child maltreatment, victimisation and trauma. AIFS, Child Family Community Information Exchange, Melbourne. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hofman A, Jaddoe VW, Mackenbach JP, et al. Growth, development and health from early fetal life until young adulthood: the Generation R Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18(1):61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaddoe VW, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, et al. The Generation R Study: design and cohort update 2012. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27(9):739–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaddoe VW, van Duijn CM, van der Heijden AJ, et al. The Generation R Study: design and cohort update until the age of 4 years. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23(12):801–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaddoe VW, van Duijn CM, van der Heijden AJ, et al. The Generation R Study: design and cohort update 2010. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(11):823–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amone-P’Olak K, Ormel J, Huisman M, Verhulst FC, Oldehinkel AJ, Burger H. Life stressors as mediators of the relation between socioeconomic position and mental health problems in early adolescence: the TRAILS study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(10):1031–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown GW, Harris TO. Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. New York, NY: Free Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goodman A, Goodman R. Population mean scores predict child mental disorder rates: validating SDQ prevalence estimators in Britain. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52(1):100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Achenbach TM, Rescorla L. Child behavior checklist. Burlington; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. Ratings of relations between DSM-IV diagnostic categories and items of the CBCL/6–18, TRF, and YSR. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campbell SB. Behavior problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Journal of child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36(1):113–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hibbeln JR, Davis JM, Steer C, et al. Maternal seafood consumption in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood (ALSPAC study): An observational cohort study. The Lancet. 2007;369(9561):578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suren P, Gunnes N, Roth C, et al. Parental obesity and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):e1128–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: a review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(8):797–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Does psychiatric history bias mothers’ reports? An application of a new analytic approach. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):971–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ringoot AP, Tiemeier H, Jaddoe VW, et al. Parental depression and child well-being: young children’s self-reports helped addressing biases in parent reports. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2015;68(8):928–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan YC. Multiple imputation for missing data: Concepts and new development (Version 9.0). SAS Institute Inc, Rockville, MD: 2010;49:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pollak SD, Nelson CA, Schlaak MF, et al. Neurodevelopmental effects of early deprivation in postinstitutionalized children. Child development. 2010;81(1):224–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children’s adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(04):759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peña CJ, Kronman HG, Walker DM, et al. Early life stress confers lifelong stress susceptibility in mice via ventral tegmental area OTX2. Science (New York, NY). 2017;356(6343):1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:541–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teicher MH, Samson JA. Annual research review: enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2016;57(3):241–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tottenham N, Sheridan MA. A review of adversity, the amygdala and the hippocampus: A consideration of developmental timing. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2010;3:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fox SE, Levitt P, Nelson CA. How the timing and quality of early experiences influence the development of brain architecture. Child Dev. 2010;81(1):28–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McLaughlin KA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA. Adverse rearing environments and neural development in children: The development of frontal electroencephalogram asymmetry. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:1008–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McLaughlin KA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, Sheridan MA, Marshall P, Nelson CA. Delayed maturation in brain electrical activity partially explains the association between early environmental deprivation and symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sheridan MA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, McLaughlin KA, Nelson CA. Variation in neural development as a result of exposure to institutionalization early in childhood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(32):12927–12932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Salzinger S. A longitudinal analysis of risk factors for child maltreatment: Findings of a 17-year prospective study of officially recorded and self-reported child abuse and neglect. Child abuse & neglect. 1998;22(11):1065–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tandon M, Cardeli E, Luby J. Internalizing Disorders in Early Childhood: A Review of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009;18(3):593–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Stressful life events and major depression: risk period, long-term contextual threat, and diagnostic specificity. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 1998;186(11):661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Livianos-Aldana L, Rojo-Moreno L, Cervera-Martínez G, Dominguez-Carabantes J. Temporal evolution of stress in the year prior to the onset of depressive disorders. Journal of affective disorders. 1999;53(3):253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bebbington P, Der G, Maccarthy B, et al. Stress incubation and the onset of affective disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;162(3):358–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, Buka SL. Socio-economic status, family disruption and residential stability in childhood: Relation to onset, recurrence and remission of major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33(8):1341–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hazel NA, Hammen C, Brennan PA, Najman J. Early childhood adversity and adolescent depression: The mediating role of continued stress. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(4):581–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Andrews B, Brewin CR, Philpott R, Stewart L. Delayed-onset posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1319–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Santiago PN, Ursano RJ, Gray CL, et al. A systematic review of PTSD prevalence and trajectories in DSM-5 defined trauma exposed populations: intentional and non-intentional traumatic events. PloS one. 2013;8(4):e59236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(3):216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yule W, Bolton D, Udwin O, Boyle S, O’Ryan D, Nurrish J. The long-term psychological effects of a disaster experienced in adolescence: I: The incidence and course of PTSD. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2000;41(4):503–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ruggeri M, Bonetto C, Lasalvia A, et al. A multi-element psychosocial intervention for early psychosis (GET UP PIANO TRIAL) conducted in a catchment area of 10 million inhabitants: study protocol for a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Andersen SL, Teicher MH. Stress, sensitive periods and maturational events in adolescent depression. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(4):183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McCrory EJ, Gerin MI, Viding E. Annual research review: childhood maltreatment, latent vulnerability and the shift to preventative psychiatry–the contribution of functional brain imaging. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2017;58(4):338–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Evans GW, Li D, Whipple SS. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;139(1):342–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rutter M Protective factors in children’s responses to stress and disadvantage. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 1979;8(3):324–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Monroe SM, Simons AD. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110(3):406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Scott KM, McLaughlin KA, Smith DAR, Ellis PM. Childhood maltreatment and DSM-IV adult mental disorders: Comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;200(6):469–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):68–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1151–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.