Abstract

Background

Obesity and long term health condition (LTHC) are major public health concerns that have an impact on productivity losses at work. Little is known about the longitudinal association between obesity and LTHC with impaired productivity.

Objective

This study aims to explore the longitudinal association between obesity and LTHC with presenteeism or working while sick.

Design

Longitudinal research design

Setting

Australian workplaces

Methods

This study pooled individual-level data of 111,086 employees collected in wave 6 through wave 18 from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. The study used a Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) model with logistic link function to estimate the association.

Results

The findings suggest that overweight (Odds Ratios [OR]: 1.09, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.05–1.14), obesity (OR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.31–1.45), and LTHC (OR: 3.03, 95% CI: 2.90–3.16) are significantly positively associated with presenteeism.

Conclusions

The longitudinal association between obesity and LTHC with presenteeism among Australian employees implies that interventions to improve workers' health and well-being will reduce the risk of presenteeism at work.

Introduction

The global obesity prevalence has nearly tripled since 1975. In 2016, 13% (over 650 million) of adults aged 18 years and over were obese, worldwide [1]. In 2017–18, nearly 2 in 3 (67%, 12.5 million) Australian adults were either overweight or obese, and 1 in 3 adults was obese [2]. The rising prevalence of overweight and obesity is a serious public health concern in Australia as this trend has high health and financial costs to the economy [3]. In 2015, 8.4% of the disease burden was attributable to overweight and obesity in Australia [2]. Overweight and obesity cost AUD 8.6 billion to the Australian economy in 2011–12 [4].

Excessive weight in workers caused direct (e.g. patient care and medical supplies) and indirect (e.g. lost productivity) cost burdens to employers. The indirect costs of obesity can be grouped into six categories [5] and both absenteeism and presenteeism have contributed highly to indirect costs. Presenteeism is the second main component of measuring workplace productivity and is defined as impaired functioning while being present at work due to the presence of mental or physical health complications [6]. Presenteeism is difficult to identify and measure compared with absenteeism [7]. However, there is evidence that the annual cost of presenteeism is higher than that of absenteeism in the US economy [8]. Like the US, productivity loss through presenteeism is a persistent and ongoing problem in the Australian economy. A landmark study revealed that the estimated cost of presenteeism was AUD 34.1 billion in 2010 and will cost AUD 35.8 billion in 2050 to the Australian economy [7].

It is assumed that obesity negatively impacts workers’ performance as obese people often suffer from comorbidities, including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and musculoskeletal disorders. The existing empirical evidence shows that obesity is positively associated with presenteeism [9–13]. Findings from two recent studies conducted in Canada and Belgium suggests that obesity is positively and significantly associated with impaired productivity [10, 11]. Moreover, three studies conducted in the US reported similar findings [9, 12, 13]. One study utilized data of 59,772 adult workers in different US occupations and found that work productivity impairment is significantly higher among obese workers than normal-weight peers [9]. Another study in the US precisely concluded that the rate of presenteeism is 12% higher among obese workers compared with healthy weight counterparts [12]. Similarly, another study of 341 manufacturing employees in the US found that obese workers are less productive than their healthy weight counterparts [13]. The study design of all of these research studies was cross-sectional and based in the US, Canada, or European countries. As a result, a systematic review study suggested conducting a longitudinal study to reconfirm the association between obesity and productivity loss at workplace [5].

No studies have quantified the longitudinal association between workers’ health and impaired productivity. Longitudinal studies can track individual changes over time, and thus can estimate the association more precisely than cross-sectional studies. Additionally, much research has measured presenteeism through a single question and not incorporated important job-related characteristics. To overcome these limitations, the present study aimed to quantify the association between Body Mass Index (BMI) and LTHC with presenteeism using longitudinal data. Three questions will be used to validate the measure of presenteeism. Further, this study will incorporate several health-related, socio-economic, lifestyle, and job-related characteristics as confounders to precisely measure the association. This study may help health policymakers and employers to identify the characteristics of employees associated with a higher rate of presenteeism and make policy interventions to improve workers’ health, thereby improving productivity in the workplace.

Conceptual framework

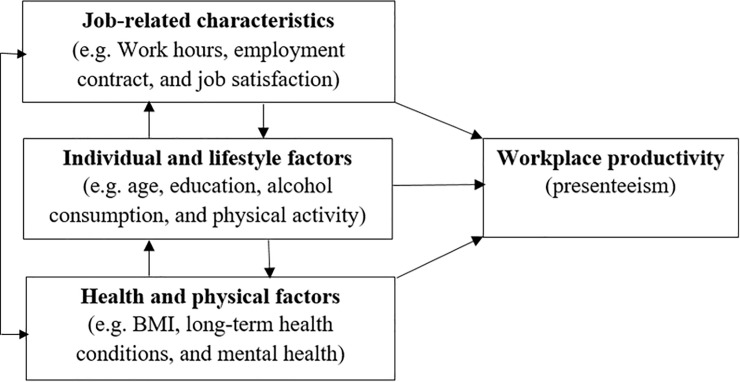

To explore the association between obesity and LTHC with presenteeism, this study followed the conceptual framework of Hafner et al. [14]. Fig 1 highlights that factors of workplace productivity are broadly categorized into three groups: job-related factors, individual and lifestyle factors, and health and physical factors. Job-related factors refer to aspects of the work environment, such as work hours, employment contracts, and overall job satisfaction of the workers. Individual and lifestyle factors are related to personal characteristics and behavior, such as age, education, family commitments, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. Health and physical factors include aspects of the health and well-being of the workers, such as weight status, long term health condition, and mental health. The conceptual model posits that job-related characteristics, individual and lifestyle factors, and health and physical factors may have a direct association with workers’ productivity. However, these factors are interrelated dynamically. For example, a worker may develop mental-health problems due to bullying in the workplace. To capture this dynamic effect, Hafner et al. [14] suggested using longitudinal data that can track the same individual over a long period.

Fig 1. Factors potentially associated with presenteeism.

Source: Hafner et al. [14].

Materials and methods

Data source and sample selection

The data of the present study were taken from the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey in Australia. HILDA is a nationally representative household-based panel survey that collects data on three main areas: economic and subjective well-being, labour market dynamics, and family life. More specifically, the survey collects data on a wide range of topics covering family relationships, wealth, income, employment, health, and education [15]. The HILDA survey was commenced in 2001 and since then has been conducted every year. Each year HILDA survey collects data on the lives of over 13,000 Australian adults from more than 7,000 households following a multi-stage sampling approach [16]. The survey collects information from individuals aged 15 years or over in the household through a personal interview by trained interviewers as well as self-completed questionnaires. The details of the survey design have been described previously [15]. The survey is funded by the Australian Government through the Department of Social Services and designed and managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research.

Questions on BMI were included in the HILDA survey from wave 6, and questions on LTHC and presenteeism have been incorporated since wave 1 (see later for details). As a result, the study utilized the most recent thirteen waves (6 to 18) from the HILDA dataset. Given the study’s focus on workplace presenteeism, the analysis was restricted to individuals who are currently employed and aged 15 to 64 years. Further, the study excluded pregnant employees from the subsample analyses to avoid potential bias. Additionally, this study restricted the sample to those with no missing information on the outcome variable (presenteeism) and main exposure variables (obesity and LTHC). After exercising the exclusion criteria, the unbalanced panel consists of 19,087 participants and 111,086 observations for the subsample analysis.

Outcome variable

The main outcome variable of the present study is presenteeism at work. The variable presenteeism was derived from the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaire. The details of the survey can be found elsewhere [17]. Participants were asked three questions through the self-completed questionnaire. More specifically, participants were asked whether they have experienced any of the following three events in the past four weeks due to any physical problems: “cut down the amount of time spent on work or other activities”; “accomplished less than would like”; and “were limited in the kind of work”. The responses were recorded in binary form: yes or no. Using these responses the present study formed a presenteeism variable which is a binary indicator. Presenteeism variable takes the value of 1 if a participant answered “yes” to any of the above three questions, and 0 otherwise.

Exposure variable

Two health-related characteristics served as the main variables of interest in the present study: obesity and LTHC. The present study used BMI to measure obesity. BMI of the respondents has been derived using the formula weight (in kilograms) divided by square of the height (in meters). BMI has been categorized into four groups following the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines; underweight (BMI <18.50), normal/healthy weight (BMI 18.50 to <25.00), overweight/pre-obesity (BMI 25.00 to <30.00), and obesity (BMI ≥30) [1]. Underweight is not a concern of the present study. As a result, this study forms a new category, BMI <25, by merging underweight and healthy weight categories following previous studies [18, 19].

The HILDA survey collects data on an individual’s LTHC following the guidelines of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) under the WHO framework [20]. Participants were presented a show-card that listed examples of long term health condition, impairments, or disabilities and asked if they have any of these conditions which restrict them in their daily activities that had lasted or were likely to last six months or more. Responses were taken in binary form, either yes or no. Respondents who answered ‘yes’ were considered as a worker with LTHC, and 0 otherwise.

Other covariates

This study selected covariates following previous studies on presenteeism at work [10, 11, 21–24]. Socio-demographic covariates included are age (15–35, 36–55, and 56–64 years), gender (male and female), civil status (partnered and non-cohabitating), education (year 12 or below, professional qualification, and university qualification), ethnicity (not of indigenous origin, and Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander [ATSI]), remoteness (major cities, regional, and remote or very remote), and equivalized household income. Household income variable was categorized into quintiles: quintile 1 (bottom quintile) though 5 (top quintile). In addition to the socio-demographic controls, this study included lifestyle factors and job-related characteristics. Lifestyle factors included smoking status (non-smoker and current smoker), alcohol consumption (non-drinker and current drinker), and physical activity (inactive, some activity, and regular activity). The HILDA survey collects data on an individual’s physical activity by asking how often they participate in physical activity. Responses were taken in 6 forms: not at all, less than once a week, 1 to 2 times a week, 3 times a week, more than 3 times a week, and every day. Respondents who answered ‘not at all’ were classified as inactive, less than once a week, 1 to 2 times a week, and 3 times a week were classified as some activity; and more than 3 times a week and every day were classified as a regular activity.

The present study included the following employment controls: hours worked per week (<35, 35–40, and >40 hours/week), employment contract (permanent, casual, and fixed-term), occupation (8 categories), industry (13 categories), supervisory responsibilities (yes or no), member of employee association (yes or no), provision of paid sick leave (yes or no), and overall job satisfaction (from 0 = worst to 10 = best).

Estimation strategy

The authors constructed an unbalanced longitudinal data set by linking individual’s records who participated in wave 6 through wave 18 of the HILDA survey. To summarise the characteristics of the cohort, the present study used descriptive statistics in the form of frequency (n) and percentage (%) along with 95% confidence intervals (CI) or mean with standard deviation (SD). Further, this study calculated the frequencies of presenteeism among the study participants by BMI categories, LTHC, and other covariates. Chi-square tests or t-test have been employed to assess the bivariate relationship between presenteeism, obesity, LTHC, and other covariates. This study included covariates in the multivariate analysis if a covariate is significant at p-value equals to 0.05 in the bivariate analysis.

Given the discrete nature of the dependent variable, presenteeism, the present study explores the association between obesity and LTHC with presenteeism using Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) with a logistic link function. The econometric model developed to capture the association is as follows.

| (1) |

In Eq 1, Yit represents presenteeism that a worker i may experience in period t; BMIit is the indicator of obesity, and LTHCit is the indicator of long term health condition. Finally, SDit,LSit, and JRit represent the vector of socio-demographic, lifestyle and job-related characteristics, respectively and εit is the error term.

In the case of longitudinal data, repeated measurements on the same adult have been collected over time. For example, data on presenteeism, weight status, and LTHC of the same adult were taken repeatedly over the study period. As a result, observations from an individual are correlated and failure to take into account this correlation may lead to bias estimates. GEE can take into account the correlation of within-individual data. GEE estimate is a quasi-likelihood method where first mean and covariance are important. In the case of longitudinal data, observations on each individual are correlated. As a result, the Generalized Linear Model (GLM) cannot estimate parameters and make inferences as it assumes errors are independent and distributed individually. GEE can handle this issue by relaxing the assumption that observations were generated from a certain distribution. GEE estimates the population-averaged effects of the parameters. The main advantage of using GEE is that it is computationally simpler compared with Maximum Likelihood Estimates (MLE) in the case of categorical data. Besides, GEE offers a better prediction of the within-subject covariance structure. The main limitation of the GEE estimate is that likelihood-based methods cannot be applied to estimate the statistical inference.

This study revealed the adjusted association between obesity and LTHC with presenteeism by incorporating socio-demographic (age, gender, civil status, education, ethnicity, remoteness, and equivalized household income), lifestyle (smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity) and job-related characteristics (hours worked per week, employment contract, occupation, industry, supervisory responsibilities, member of an employee association, paid sick leave and overall job satisfaction). The study results are presented in the form of Odds Ratio (OR) for each explanatory variable. This study set a P-value at <0.05 level for statistical significance. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 16, Windows version.

Ethics approval

This study requires no ethics approval for the authors as the analysis used only de-identified existing unit record data from the HILDA survey. However, the authors completed and signed the Confidentiality Deed Poll and sent it to NCLD (ncldresearch@dss.gov.au) and ADA (ada@anu.edu.au) before the data applications’ approval. Therefore, datasets analyzed and/or generated during the current study are subject to the signed confidentiality deed.

Results

Table 1 provides a summary of the prevalence of presenteeism, BMI class, presence of LTHC, socio-demographic, lifestyle and employment characteristics of the study participants. A total of 111,086 workers were included in the final analysis. Among the participants, approximately 19% of workers reported presenteeism. Table 1 showed that approximately 35% of workers were overweight, 22% were obese and 16% had LTHC.

Table 1. Background characteristics of the study participants.

| Variables | n | % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: Presenteeism | ||

| No | 90,172 | 81.17 (80.94–81.40) |

| Yes | 20,914 | 18.83 (18.60–19.06) |

| Health-related characteristics | ||

| BMI categories | ||

| BMI (<25) | 47,723 | 42.96 (42.67–43.25) |

| Overweight (25.00–29.99) | 38,564 | 34.72 (34.44–35.10) |

| Obesity (≥30) | 24,799 | 22.32 (22.08–22.57) |

| Long term health condition | ||

| No | 92,955 | 83.68 (83.46–83.89) |

| Yes | 18,131 | 16.32 (16.11–16.54) |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| 15–35 years | 46,943 | 42.26 (41.97–42.55) |

| 36–55 years | 50,047 | 45.05 (44.76–45.34) |

| 56–64 years | 14,096 | 12.69 (12.49–12.89) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 56,126 | 50.52 (50.23–50.82) |

| Female | 54,960 | 49.48 (49.18–49.77) |

| Civil status | ||

| Married / partnered) | 69,914 | 62.94 (62.65–63.22) |

| Non-cohabitating | 41,172 | 37.06 (36.78–37.35) |

| Education | ||

| Year 12 or below | 40,270 | 36.25 (35.97–36.53) |

| Professional qualification | 37,150 | 33.44 (33.17–33.72) |

| University qualification | 33,666 | 30.31 (30.04–30.58) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Not of indigenous origin | 108,323 | 97.51 (97.42–97.60) |

| ATSI | 2,763 | 2.49 (2.40–2.58) |

| Remoteness | ||

| Major Cities | 76,583 | 68.94 (68.67–69.21) |

| Regional | 32,862 | 29.58 (29.31–29.85) |

| Remote or very remote | 1,641 | 1.48 (1.41–1.55) |

| Household income quintile | ||

| Quintile 1 (bottom quintile) | 16,592 | 14.94 (14.73–15.15) |

| Quintile 2 | 20,722 | 18.65 (18.43–18.88) |

| Quintile 3 | 22,763 | 20.49 (20.25–20.73) |

| Quintile 4 | 25,289 | 22.77 (22.52–23.01) |

| Quintile 5 (top quintile) | 25,720 | 23.15 (22.91–23.40) |

| Lifestyle factors | ||

| Smoking status | ||

| Non-smoker | 89,749 | 80.79 (80.56–81.02) |

| Current Smoker | 21,337 | 19.21 (18.98–19.44) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| Former/non-drinker | 14,279 | 12.85 (12.66–13.05) |

| Current drinker | 96,807 | 87.15 (86.95–87.34) |

| Physical activity | ||

| Inactive | 29,499 | 26.56 (26.30–26.82) |

| Some activity | 35,845 | 32.27 (31.99–32.54) |

| Regular activity | 45,742 | 41.18 (40.89–41.47) |

| Job-related characteristics | ||

| Farm Size | ||

| Small | 47,902 | 43.12 (42.83–43.41) |

| Medium | 30,658 | 27.60 (27.34–27.86) |

| Large | 32,526 | 29.28 (29.01–29.55) |

| Hours worked/week | ||

| <35 hours a week | 36,153 | 32.55 (32.27–32.82) |

| 35–40 hours a week | 40,110 | 36.11 (35.83–36.39) |

| >40 hours a week | 34,823 | 31.35 (31.08–31.62) |

| Employment contract | ||

| Permanent | 74,694 | 67.24 (66.96–67.52) |

| Casual | 10,836 | 9.75 (9.58–9.93) |

| Fixed-term | 25,556 | 23.01 (22.76–23.25) |

| Occupation | ||

| Professional | 27,209 | 24.49 (24.24–24.75) |

| Managerial | 14,550 | 13.10 (12.90–13.30) |

| Technical trade | 14,596 | 13.14 (12.94–13.34) |

| Personal services | 12,809 | 11.53 (11.34–11.72) |

| Clerical | 15,878 | 14.29 (14.09–14.50) |

| Sales | 10,007 | 9.01 (8.84–9.18) |

| Machinery | 6,373 | 5.74 (5.60–5.88) |

| Labour work | 9,664 | 8.70 (8.54–8.87) |

| Industry | ||

| Public services | 7,444 | 6.70 (6.56–6.85) |

| Agriculture | 2,681 | 2.41 (2.32–2.51) |

| Mining | 1,972 | 1.78 (1.70–1.85) |

| Manufacturing | 8,911 | 8.02 (7.86–8.18) |

| Electricity | 1,104 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) |

| Construction | 8,938 | 8.05 (7.89–8.21) |

| Trade | 14,621 | 13.16 (12.96–13.36) |

| Hospitality | 7,153 | 6.44 (6.30–6.59) |

| Transport | 6,943 | 6.25 (6.11–6.39) |

| Finance | 4,006 | 3.61 (3.50–3.72) |

| Education | 11,417 | 10.28 (10.10–10.42) |

| Health | 15,819 | 14.24 (14.04–14.45) |

| Other services | 20,077 | 18.07 (17.85–18.30) |

| Supervisory responsibilities | ||

| Yes | 50,524 | 45.48 (45.19–45.77) |

| No | 60,562 | 54.52 (54.23–54.81) |

| Employee association | ||

| Yes | 26,021 | 23.42 (23.18–23.67) |

| No | 85,065 | 76.58 (76.33–76.82) |

| Paid sick leave | ||

| Yes | 81,543 | 73.41 (73.14–73.66) |

| No | 29,543 | 26.59 (26.34–26.86) |

| Overall job satisfaction (Mean [SD]) | 111,086 | 7.65 (1.62) |

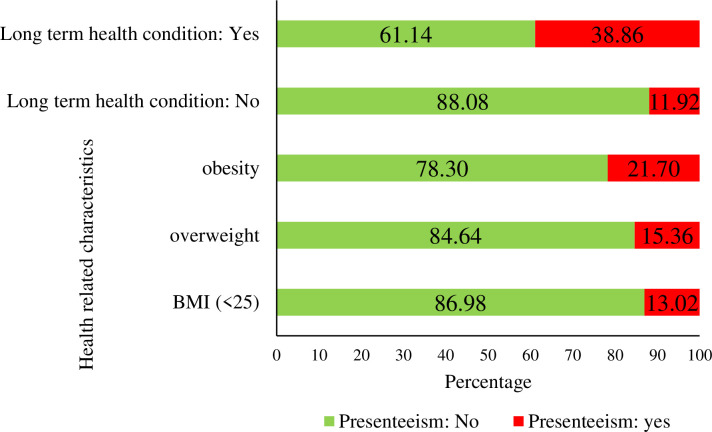

Fig 2 demonstrates the reported presenteeism by weight status and presence of LTHC. There was a substantial difference in the prevalence of presenteeism by BMI categories and LTHC variables. The prevalence of presenteeism was found highest among obese workers (22%), following overweight (16%), and workers with BMI<25 (13%). Approximately, 39% of workers having LTHC reported presenteeism.

Fig 2. Prevalence of presenteeism by weight status and long term health condition.

Table 2 presents the distribution of reported presenteeism by BMI categories, health, socio-demographic, lifestyle, and job-related characteristics. Table 2 also reports the bivariate relationship between presenteeism, obesity, LTHC along with other covariates achieved through the Chi-square tests or t-tests. The results showed that BMI, LTHC, and all the confounders were significantly associated with presenteeism in the bivariate analyses.

Table 2. Bivariate analysis between health, socio-demographic, lifestyle, and job-related characteristics with presenteeism in Australian workers.

| Variables | No presenteeism | Presenteeism | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | ||

| Health-related characteristics | |||||

| BMI categories | <0.001 | ||||

| BMI (<25) | 39,904 | 83.62 (83.28–83.95) | 7,819 | 16.38 (16.05–16.72) | |

| Overweight (25.00–29.99) | 31,708 | 82.22 (81.84–82.60) | 6,856 | 17.78 (17.40–18.16) | |

| Obesity (≥30) | 18,560 | 74.84 (74.30–75.38) | 6,239 | 25.16 (24.62–25.70) | |

| Long term health condition | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 80,047 | 86.11 (85.89–86.33) | 12,908 | 13.89 (13.67–14.11) | |

| Yes | 10,125 | 55.84 (55.12–56.57) | 8,006 | 44.16 (43.43–44.88) | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age | <0.001 | ||||

| 15–35 years | 39,739 | 84.65 (84.32–84.98) | 7,204 | 15.35 (15.02–15.68) | |

| 36–55 years | 39,952 | 79.83 (79.48–80.18) | 10,095 | 20.17 (19.82–20.52) | |

| 56–64 years | 10,481 | 74.35 (73.63–75.07) | 3,615 | 25.65 (24.93–26.37) | |

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 46,766 | 83.32 (83.01–83.63) | 9,360 | 16.68 (16.37–16.99) | |

| Female | 43,406 | 78.98 (78.63–79.32) | 11,554 | 21.02 (20.68–21.37) | |

| Civil status | <0.01 | ||||

| Married / partnered) | 57,065 | 81.62 (81.33–81.91) | 12,849 | 18.38 (18.09–18.67) | |

| Non-cohabitating | 33,107 | 80.41 (80.03–80.79) | 8,065 | 19.59 (19.21–19.97) | |

| Education | <0.01 | ||||

| Year 12 or below | 32,986 | 81.91 (81.53–82.29) | 7,284 | 18.09 (17.71–18.47) | |

| Professional qualification | 29,814 | 80.25 (79.85–80.65) | 7,336 | 19.75 (19.35–20.15) | |

| University qualification | 27,372 | 81.30 (80.88–81.72) | 6,294 | 18.70 (18.28–19.12) | |

| Ethnicity | <0.01 | ||||

| Not of indigenous origin | 88,000 | 81.24 (81.00–81.47) | 20,323 | 18.76 (18.53–19.00) | |

| ATSI | 2,172 | 78.61 (77.04–80.10) | 591 | 21.39 (19.90–22.96) | |

| Remoteness | <0.01 | ||||

| Major Cities | 62,455 | 81.55 (81.28–81.83) | 14,128 | 18.45 (18.17–18.72) | |

| Regional | 26,349 | 80.18 (79.75–80.61) | 6,513 | 19.82 (19.39–20.25) | |

| Remote or very remote | 1,368 | 83.36 (81.48–85.09) | 273 | 16.64 (14.91–18.52) | |

| Household income quintile | <0.001 | ||||

| Quintile 1 (bottom quintile) | 13,017 | 78.45 (77.82–79.07) | 3,575 | 21.55 (20.93–22.18) | |

| Quintile 2 | 16,620 | 80.20 (79.66–80.74) | 4,102 | 19.80 (19.26–20.34) | |

| Quintile 3 | 18,304 | 80.41 (79.89–80.92) | 4,459 | 19.59 (19.08–20.11) | |

| Quintile 4 | 20,799 | 82.25 (81.77–82.71) | 4,490 | 17.75 (17.29–18.23) | |

| Quintile 5 (top quintile) | 21,432 | 83.33 (82.87–83.78) | 4,288 | 16.67 (16.22–17.13) | |

| Lifestyle factors | |||||

| Smoking status | 73,379 | 81.76 (81.51–82.01) | 16370 | 18.24 (17.99–18.49) | <0.001 |

| Non-smoker | 16,793 | 78.70 (78.15–79.25) | 4,544 | 21.30 (20.75–21.85) | |

| Current Smoker | |||||

| Alcohol consumption | <0.001 | ||||

| Former/non-drinker | 10,948 | 76.67 (75.97–77.36) | 3,331 | 23.33 (22.64–24.03) | |

| Current drinker | 79,224 | 81.84 (81.59–82.08) | 17,583 | 18.16 (17.92–18.41) | |

| Physical activity | <0.001 | ||||

| Inactive | 23,282 | 78.92 (78.46–79.39) | 6,217 | 21.08 (20.61–21.54) | |

| Some activity | 29,095 | 81.17 (80.76–81.57) | 6,750 | 18.83 (18.43–19.24) | |

| Regular activity | 37,795 | 82.63 (82.28–82.97) | 7,947 | 17.37 (17.03–17.72) | |

| Job-related characteristics | |||||

| Farm Size | <0.001 | ||||

| Small | 38,510 | 80.39 (80.04–80.75) | 9,392 | 19.61 (19.25–19.96) | |

| Medium | 25,148 | 82.03 (81.59–82.45) | 5,510 | 17.97 (17.55–18.41) | |

| Large | 26,514 | 81.52 (81.09–81.93) | 6,012 | 18.48 (18.07–18.91) | |

| Hours worked/week | <0.001 | ||||

| <35 hours a week | 28,288 | 78.25 (77.82–78.67) | 7,865 | 21.75 (21.33–22.18) | |

| 35–40 hours a week | 33,049 | 82.40 (82.02–82.77) | 7,061 | 17.60 (17.23–17.98) | |

| >40 hours a week | 28,835 | 82.80 (82.40–83.20) | 5,988 | 17.20 (16.80–17.60) | |

| Employment contract | <0.001 | ||||

| Permanent | 61,060 | 81.75 (81.47–82.02) | 13,634 | 18.25 (17.98–18.53) | |

| Casual | 8,865 | 81.81 (81.07–82.53) | 1,971 | 18.19 (17.47–18.93) | |

| Fixed-term | 20,247 | 79.23 (78.72–79.72) | 5,309 | 20.77 (20.28–21.28) | |

| Occupation | <0.001 | ||||

| Professional | 22,060 | 81.08 (80.61–81.54) | 5,149 | 18.92 (18.46–19.39) | |

| Managerial | 11,986 | 82.38 (81.75–82.99) | 2,564 | 17.62 (17.01–18.25) | |

| Technical trade | 12,078 | 82.75 (82.13–83.35) | 2,518 | 17.25 (16.65–17.87) | |

| Personal services | 10,093 | 78.80 (78.08–79.50) | 2,716 | 21.20 (20.50–21.92) | |

| Clerical | 12,941 | 81.50 (80.89–82.10) | 2,937 | 18.50 (17.90–19.11) | |

| Sales | 8,199 | 81.93 (81.17–82.67) | 1,808 | 18.07 (17.33–18.83) | |

| Machinery | 5,193 | 81.48 (80.51–82.42) | 1,180 | 18.52 (17.58–19.49) | |

| Labour work | 7,622 | 78.87 (78.04–79.67) | 2,042 | 21.13 (20.33–21.96) | |

| Industry | <0.001 | ||||

| Public services | 6,076 | 81.62 (80.73–82.49) | 1,368 | 18.38 (17.51–19.27) | |

| Agriculture | 2,052 | 76.54 (74.90–78.10) | 629 | 23.46 (21.90–25.10) | |

| Mining | 1,667 | 84.53 (82.87–86.06) | 305 | 15.47 (13.94–17.13) | |

| Manufacturing | 7,327 | 82.22 (81.42–83.00) | 1,584 | 17.78 (17.00–18.58) | |

| Electricity | 927 | 83.97 (81.68–86.02) | 177 | 16.03 (13.98–18.32) | |

| Construction | 7,489 | 83.79 (83.01–84.54) | 1,449 | 16.21 (15.46–16.99) | |

| Trade | 12,034 | 82.31 (81.68–82.92) | 2,587 | 17.69 (17.08–18.32) | |

| Hospitality | 5,787 | 80.90 (79.98–81.80) | 1,366 | 19.10 (18.20–20.02) | |

| Transport | 5,633 | 81.13 (80.19–82.04) | 1,310 | 18.87 (17.96–19.81) | |

| Finance | 3,379 | 84.35 (83.19–85.44) | 627 | 15.65 (14.56–16.81) | |

| Education | 9,143 | 80.08 (79.34–80.80) | 2,274 | 19.92 (19.20–20.66) | |

| Health | 12,259 | 77.50 (76.84–78.14) | 3,560 | 22.50 (21.86–23.16) | |

| Other services | 16,399 | 81.68 (81.14–82.21) | 3,678 | 18.32 (17.79–18.86) | |

| Supervisory responsibilities | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 41,342 | 81.83 (81.49–82.16) | 9,182 | 18.17 (17.84–18.51) | |

| No | 48,830 | 80.63 (80.31–80.94) | 11,732 | 19.37 (19.06–19.69) | |

| Employee association | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 20,599 | 79.16 (78.67–79.65) | 5,422 | 20.84 (20.35–21.33) | |

| No | 69,573 | 81.79 (81.53–82.05) | 15,492 | 18.21 (17.95–18.47) | |

| Paid sick leave | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 66,664 | 81.75 (81.49–82.02) | 14,879 | 18.25 (17.98–18.51) | |

| No | 23,508 | 79.57 (79.11–80.03) | 6,035 | 20.43 (19.97–20.89) | |

| Overall job satisfaction | 90,172 | 7.73 (1.56) | 20,914 | 7.32 (1.81) | <0.001 |

Table 3 displays the estimates of the association between obesity, LTHC, and presenteeism. To facilitate interpretation, this study presents the results in the form of odds ratios which indicate a change in the odds of presenteeism associated with a change in the level of an explanatory variable. The present study found that both obesity and LTHC were significant predictors of high presenteeism at work. The adjusted model demonstrates that the odds of presenteeism among the overweight and obese workers were 1.09 (95% CI: 1.05–1.14) and 1.38 (95% CI: 1.31–1.45) times higher, respectively, compared with workers with BMI<25. The results also revealed that workers having LTHC were 3.03 times (95% CI: 2.90–3.16) more likely to report presenteeism compared with peers not having LTHC.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis using Generalized Estimating Equation for factors associated with presenteeisma.

| Variables | Fully adjusted model |

|---|---|

| OR (95% CI), P-value | |

| Health-related characteristics | |

| BMI categories | |

| BMI (<25) (ref) | |

| Overweight (25.00–29.99) | 1.09 (1.05–1.14), <0.001 |

| Obesity (≥30) | 1.38 (1.31–1.45), <0.001 |

| Long term health condition (LTHC) | |

| No (ref) | |

| Yes | 3.03 (2.90–3.16), <0.001 |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |

| Age | |

| 15–35 years (ref) | |

| 36–55 years | 1.22 (1.16–1.27), <0.001 |

| 56–64 years | 1.45 (1.36–1.55), <0.001 |

| Gender | |

| Male (ref) | |

| Female | 1.29 (1.23–1.36), <0.001 |

| Civil status | |

| Married / partnered (ref) | |

| Non-cohabitating | 1.07 (1.02–1.11), 0.005 |

| Education | |

| Year 12 or below (ref) | |

| Professional qualification | 1.10 (1.04–1.16), 0.001 |

| University qualification | 1.13 (1.05–1.20), <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Not of indigenous origin (ref) | |

| ATSI | 1.11 (0.97–1.26), 0.119 |

| Remoteness | |

| Major Cities | |

| Regional | 1.01 (0.96–1.06), 0.795 |

| Remote or very remote | 0.92 (0.78–1.08), 0.317 |

| Household income quintile | |

| Quintile 1 (bottom quintile) | 1.11 (1.05–1.18), <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 1.05 (0.99–1.10), 0.114 |

| Quintile 3 | 1.00 (0.95–1.06), 0.994 |

| Quintile 4 | 0.99 (0.94–1.04), 0.786 |

| Quintile 5 (top quintile) (ref) | |

| Lifestyle factors | |

| Smoking status | |

| Non-smoker (ref) | |

| Current Smoker | 1.20 (1.15–1.26), <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| Former/non-drinker (ref) | |

| Current drinker | 0.75 (0.72–0.80), <0.001 |

| Physical activity | |

| Inactive (ref) | |

| Some activity | 0.68 (0.65–0.72), <0.001 |

| Regular activity | 0.53 (0.50–0.56), <0.001 |

| Job-related characteristics | |

| Farm Size | |

| Small (ref) | |

| Medium | 0.93 (0.89–0.98), 0.003 |

| Large | 0.96 (0.91–1.00), 0.071 |

| Hours worked/week | |

| <35 hours a week | 1.10 (1.05–1.15), <0.001 |

| 35–40 hours a week (ref) | |

| >40 hours a week | 0.97 (0.93–1.02), 0.202 |

| Employment contract | |

| Permanent (ref) | |

| Casual | 1.04 (0.97–1.13), 0.304 |

| Fixed-term | 0.97 (0.91–1.03), 0.283 |

| Occupation | |

| Professional (ref) | |

| Managerial | 0.97 (0.90–1.04), 0.343 |

| Technical trade | 1.03 (0.95–1.12), 0.431 |

| Personal services | 1.04 (0.97–1.12), 0.293 |

| Clerical | 0.93 (0.87–1.01), 0.052 |

| Sales | 1.00 (0.92–1.09), 0.978 |

| Machinery | 0.98 (0.88–1.08), 0.681 |

| Labour work | 1.08 (0.99–1.18), 0.075 |

| Industry | |

| Public services (ref) | |

| Agriculture | 1.15 (0.98–1.34), 0.083 |

| Mining | 1.01 (0.85–1.19), 0.942 |

| Manufacturing | 0.93 (0.83–1.03), 0.152 |

| Electricity | 0.92 (0.75–1.11), 0.367 |

| Construction | 0.98 (0.88–1.09), 0.701 |

| Trade | 0.91 (0.83–1.01), 0.075 |

| Hospitality | 0.94 (0.84–1.04), 0.236 |

| Transport | 0.99 (0.88–1.10), 0.795 |

| Finance | 0.86 (0.75–0.98), 0.024 |

| Education | 0.99 (0.89–1.09), 0.795 |

| Health | 1.00 (0.91–1.10), 0.992 |

| Other services | 0.96 (0.88–1.05), 0.429 |

| Supervisory responsibilities | |

| Yes (ref) | |

| No | 0.97 (0.94–1.01), 0.157 |

| Employee association | |

| Yes (ref) | |

| No | 0.93 (0.89–0.98), 0.004 |

| Paid sick leave | |

| Yes (ref) | |

| No | 0.98 (0.91–1.05), 0.537 |

| Overall job satisfaction (from 0 = worst to 10 = best) | 0.91 (0.90–0.92), <0.001 |

Abbreviations: OR Odds Ratios; CI Confidence Interval; Ref Reference.

aValues in bold are statistically significant at p<0.05.

Discussion

This population-based study found that the main effect of obesity and LTHC is strikingly similar. The study showed positive associations between obesity and LTHC with presenteeism among workers in different occupations in Australia.

Obese workers have higher odds of presenteeism than non-obese workers (BMI<25). The large disparity in the odds of diminished productivity at work associated with obesity is expected given that participants were explicitly asked about productivity loss stemming from physical problems. This finding is in line with previous studies where obesity has been identified as a strong predictor of presenteeism [10, 11]. Other observational studies conducted in the US have confirmed that obesity had a negative impact on work through presenteeism [9, 12, 13]. However, a recent study using a cross-sectional correlational design found that BMI was unrelated to presenteeism [23].

Presenteeism at work may occur due to health problems, such as the functional limitations of the workers. Another striking finding of the present study is that LTHC is linked to an increase in the odds of presenteeism. This finding is in line with an earlier study that found employees with chronic health conditions report higher rates of presenteeism compared with peers without having such health conditions [14]. A prior study also revealed that workers with moderate and severe functional limitations due to health problems were 1.28 and 1.63 times, respectively, more likely to report productivity loss at work [25]. Besides, a recent study claimed that the likelihood of presenteeism is higher among workers with chronic health conditions [10]. However, this finding is contrary to other studies that have suggested that health conditions, such as allergies, asthma, arthritis, back pain, sinus problems, broken bones, heart disease, cancer, and diabetes are not associated with presenteeism in the workplace [23].

There are several reasons behind the positive association between obesity and LTHC with work productivity impairment. Obese workers often face difficulty in moving due to bodyweight/size and excess adiposity. Moreover, body pain, musculoskeletal pain, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis are often associated with weight gain [26]. The presence of these co-morbidities may limit obese workers’ ability to move without pain or discomfort and could result in productivity impairment in a physically demanding job [27]. Another possible explanation is that obese workers with sleep apnea and heart disease may experience weakness and dyspnea (shortness of breath). These health conditions make workers tired or slow to complete their job tasks on time [13].

The study findings confirm the need for effective interventions to reduce obesity in workers and improve their productivity at work. At present, the workplace has been considered as a potential avenue through which interventions could be implemented for managing healthy weight [28]. The findings of this study are expected to serve as useful evidence to health policymakers and employers to initiate workplace-based interventions to combat the obesity epidemic at work and thus reducing the productivity loss of the workers. Organizations should focus on multi-pronged interventions, such as providing information, social support for promoting a healthy lifestyle, and modification of the work environment to facilitate weight management of employees. For example, organizations may introduce sit-stand desks to reduce sitting time at work among desk-based workers, offer healthier food choices in cafeteria menus and vending machines, encourage walking during breaks, support active commuting options, provide educational modules on physical activity, diet, and lifestyle change, and establish gym and activity centers for performing physical activities.

The present study offers an important contribution to the existing body of knowledge by revealing a longitudinal association between obesity and LTHC with workplace performance by using data of 111,086 Australian workers from 2006 through 2018. In the existing literature, the majority of studies were cross-sectionally designed and thus cannot reveal the within-person change in presenteeism due to obesity and LTHC. The present study has several important strengths. First, is that it measured presenteeism using three comprehensive questions. Many of the previous studies assessed presenteeism through a single question [11, 29, 30] and it is difficult to establish the validity of presenteeism measure through a single question. Moreover, this study incorporated a large number of employment controls including less investigated variables (supervisory responsibilities, member of employee association or union, paid sick leave, and overall job satisfaction) to precisely estimate the association between obesity and LTHC with presenteeism. Additionally, this study fills the gap of the lack of studies on the longitudinal association between obesity and LTHC with presenteeism.

The present study has certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the study results might be vulnerable to self-reported bias, as data on BMI and presenteeism along with other covariates were self-reported. Previous studies demonstrated that self-reported BMI is usually less than actual BMI as respondents tend to underreport weight and overreport height [31, 32]. Besides, this study’s unbalanced longitudinal research design prevents inferring the direction of causality. Given these limitations, the present study calls for prospective research that may capture the within-person change in presenteeism due to obesity and LTHC.

Conclusion and recommendations

In summary, the present study utilized a large nationally representative dataset over the period from 2006 to 2018 to examine the longitudinal association between obesity, LTHC, and presenteeism. The study findings demonstrated that obesity and LTHC have longitudinal associations with presenteeism, independent of health, socio-demographic, lifestyle, and job-related confounders. Overweight and obesity among workers increases the costs of employers as overweight and obese workers reported higher presenteeism than under and normal-weight counterparts (BMI<25) at work. This study adds evidence to the existing literature that has shown the negative impact of obesity on presenteeism.

Presenteeism is a perennial and costly problem that should be tackled. The study findings stress the importance of health promotion, more specifically promoting healthy weight maintenance to reduce presenteeism or productivity loss at work. Maintaining healthy weight among workers through a healthy lifestyle may result in lower presenteeism, leading to socio-economic benefits for individual workers, employers, and society as a whole.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research for providing the HILDA data set. This paper uses unit record data from Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey (HILDA) conducted by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Australian Government, DSS, or any of DSS’ contractors or partners. DOI: 10.26193/OFRKRH, ADA Dataverse, V2."

Abbreviation

- ATSI

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander

- AUD

Australian Dollar

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- HILDA

Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey

- LTHC

Long Term Health Condition

- OR

Odds Ratio

- WHO

World Health Organization

Data Availability

The authors completed and signed the Confidentiality Deed Poll and sent it to NCLD (ncldresearch@dss.gov.au) and ADA (ada@anu.edu.au) before the data applications’ approval. Therefore, datasets analyzed and/or generated during the current study are subject to the signed confidentiality deed. The present study used HILDA data set, which is a third-party data set and were collected by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. There are some formalities on accessing and legal restrictions on sharing this data set. Those interested in accessing this data should contact the ADA (ada@anu.edu.au) and the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia (ncldresearch@dss.gov.au).

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and overweight [Internet]. 2018 [cited 7 March 2020]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- 2.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Overweight and obesity: an interactive insight. Cat. no. PHE 251. Canberra: AIHW; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. A picture of overweight and obesity in Australia 2017. Cat. no. PHE 216. Canberra: AIHW; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.PwC Australia. Weighing the cost of obesity: a case for action. Australia: PwC Australia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trogdon JG, Finkelstein EA, Hylands T, Dellea PS, Kamal-Bahl SJ. Indirect costs of obesity: A review of the current literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9: 489–500. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00472.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johns G. Presenteeism in the workplace: A review and research agenda. J Organ Behav. 2010;31: 519–542. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Econtech. Economic modelling of the cost of presenteeism in Australia. 2011. Available: https://www.medibank.com.au/Client/Documents/Pdfs/sick_at_work.pdf

- 8.Hitt HC, McMillen RC, Thornton-Neaves T, Koch K, Cosby AG. Comorbidity of Obesity and Pain in a General Population: Results from the Southern Pain Prevalence Study. J Pain. 2007;8: 430–436. 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kudel I, Huang JC, Ganguly R. Impact of obesity on work productivity in different US occupations: Analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey 2014 to 2015. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60: 6–11. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez Bustillos A, Vargas KG, Gomero-Cuadra R. Work productivity among adults with varied Body Mass Index: Results from a Canadian population-based survey. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2015;5: 191–199. 10.1016/j.jegh.2014.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssens H, Clays E, Kittel F, De Bacquer D, Casini A, Braeckman L. The association between body mass index class, sickness absence, and presenteeism. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54: 604–609. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31824b2133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goetzel RZ, Gibson TB, Short ME, Chu BC, Waddell J, Bowen J, et al. A multi-worksite analysis of the relationships among body mass index, medical utilization, and worker productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52: 1–16. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181c559ea [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gates DM, Succop P, Brehm BJ, Gillespie GL, Sommers BD. Obesity and presenteeism: The impact of body mass index on workplace productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50: 39–45. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31815d8db2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hafner M, Stolk C van, Saunders C, Krapels J, Baruch B. Health, wellbeing and productivity in the workplace [Internet]. 2015. Available: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1000/RR1084/RAND_RR1084.pdf

- 15.Freidin, S., Watson, N. and Wooden M. Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey: Wave 1. Melbourne; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Wilkins R. Families, Incomes, and Jobs. Volume 8: A statistical Report on Waves 1 to 10 of the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey. Melbourne; 2013.

- 17.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Lincoln (RI): QualityMetric Incorporated; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nigatu YT, Roelen CAM, Reijneveld SA, Bültmann U. Overweight and distress have a joint association with long-term sickness absence among Dutch employees. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57: 52–57. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Au N, Hollingsworth B. Employment patterns and changes in body weight among young women. Prev Med. 2011;52: 310–316. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaMontagne AD, Krnjacki L, Milner A, Butterworth P, Kavanagh A. Psychosocial job quality in a national sample of working Australians: A comparison of persons working with versus without disability. SSM—Popul Heal. 2016;2: 175–181. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bubonya M, Cobb-Clark DA, Wooden M. Mental health and productivity at work: Does what you do matter? Labour Econ. 2017;46: 150–165. 10.1016/j.labeco.2017.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bockerman P, Laukkanen E. Predictors of sickness absence and presenteeism: Does the pattern differ by a respondent’s health? J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52: 332–335. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181d2422f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callen BL, Lindley LC, Niederhauser VP. Health risk factors associated with presenteeism in the workplace. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55: 1312–1317. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182a200f4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold D. Determinants of the Annual Duration of Sickness Presenteeism: Empirical Evidence from European Data. Labour. 2016;30: 198–212. 10.1111/labr.12053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alavinia SM, Molenaar D, Burdorf A. Productivity loss in the workforce: Associations with health, work demands, and individual characteristics. Am J Ind Med. 2009;52: 49–56. 10.1002/ajim.20648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersen RE, Crespo CJ, Bartlett SJ, Bathon JM, Fontaine KR. Relationship between body weight gain and significant knee, hip, and back pain in older Americans. Obes Res. 2003;11: 1159–1162. 10.1038/oby.2003.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R. Lost Productive Time and Cost Due to Common Pain Conditions in the US Workforce. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290: 2443–2454. 10.1001/jama.290.18.2443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shrestha N, Pedisic Z, Neil-Sztramko S, Kukkonen-Harjula KT, Hermans V. The Impact of Obesity in the Workplace: a Review of Contributing Factors, Consequences and Potential Solutions. Curr Obes Rep. 2016;5: 344–360. 10.1007/s13679-016-0227-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aronsson G, Gustafsson K, Dallner M. Sick but yet at work. An empirical study of sickness presenteeism. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54: 502–509. 10.1136/jech.54.7.502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergström G, Bodin L, Hagberg J, Aronsson G, Josephson M. Sickness presenteeism today, sickness absenteeism tomorrow? A prospective study on sickness presenteeism and future sickness absenteeism. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51: 629–638. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181a8281b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maukonen M, Männistö S, Tolonen H. A comparison of measured versus self-reported anthropometrics for assessing obesity in adults: a literature review. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46: 565–579. 10.1177/1403494818761971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorber SC, Tremblay M, Moher D, Gorber B. A comparison of direct vs. self-report measures for assessing height, weight and body mass index: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2007;8: 307–326. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00347.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors completed and signed the Confidentiality Deed Poll and sent it to NCLD (ncldresearch@dss.gov.au) and ADA (ada@anu.edu.au) before the data applications’ approval. Therefore, datasets analyzed and/or generated during the current study are subject to the signed confidentiality deed. The present study used HILDA data set, which is a third-party data set and were collected by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. There are some formalities on accessing and legal restrictions on sharing this data set. Those interested in accessing this data should contact the ADA (ada@anu.edu.au) and the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia (ncldresearch@dss.gov.au).