Abstract

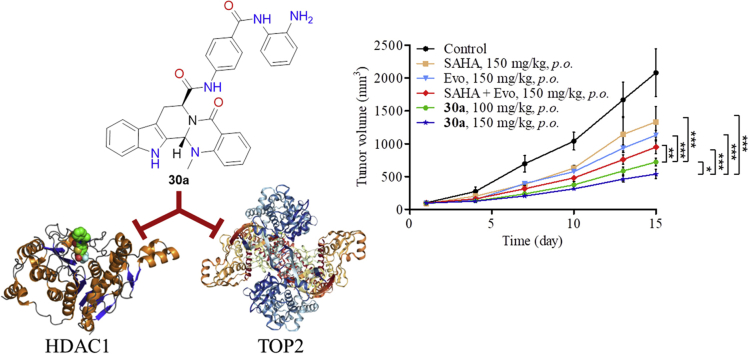

A great challenge in multi-targeting drug discovery is to identify drug-like lead compounds with therapeutic advantages over single target inhibitors and drug combinations. Inspired by our previous efforts in designing antitumor evodiamine derivatives, herein selective histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and topoisomerase 2 (TOP2) dual inhibitors were successfully identified, which showed potent in vitro and in vivo antitumor potency. Particularly, compound 30a was orally active and possessed excellent in vivo antitumor activity in the HCT116 xenograft model (TGI = 75.2%, 150 mg/kg, p.o.) without significant toxicity, which was more potent than HDAC inhibitor vorinostat, TOP inhibitor evodiamine and their combination. Taken together, this study highlights the therapeutic advantages of evodiamine-based HDAC1/TOP2 dual inhibitors and provides valuable leads for the development of novel multi-targeting antitumor agents.

Key words: Evodiamine, Histone deacetylase, Topoisomerase, Dual inhibitors, Antitumor activity

Abbreviations: BSA, bovine serum albumin; CCK-8, cell counting kit-8; CPT, camptothecin; DIPEA, N,N-diisopropylethylamine; DMF, dimethylformamide; Eto, etoposide; HATU, 1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate; HDAC, histone deacetylase; IP, intraperitoneal injection; OD, optical density; PI, propidium iodide; SD, Sprague–Dawley; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; TAE, Tris-acetate-EDTA; TGI, tumor growth inhibition; TOP, topoisomerase; ZBG, zinc-binding group

Graphical abstract

Evodiamine derivative 30a is a dual-selective inhibitor against histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and topoisomerase 2 (TOP2), which possesses excellent in vivo antitumor activity in the HCT116 xenograft model without significant toxicity.

1. Introduction

In recent years, antitumor drug discovery aimed to develop bioactive molecules acting on a single molecular target with high potency and selectivity. However, these single target drugs could hardly achieve an effective and durable control of the malignant process, due to the complex alterations of tumor cells and the redundancy of survival signaling pathways1,2. Thus, the use of drug combinations towards different targets is a well-established approach to overcome these limitations3. However, the unique pharmacokinetic features of each drug and unpredictable drug–drug interactions often leads to the difficulty in setting reasonable doses/schedules and increased possibility of adverse effects4,5. An alternative is to design a single molecule simultaneously interacting with multiple targets with synergistic effects. Ideally, a single multi-targeting molecule can offer the potential for higher efficacy, more favorable pharmacokinetic profiles and less adverse effects4. This strategy has been verified by numerous studies covering various kinds of targets and gained considerable interests in drug discovery5, 6, 7. However, the discovery of multi-targeting antitumor agents with therapeutic advantages over single-targeting drugs and their combination is still highly challenging.

In recent decades, there has been a dramatic improvement in understanding of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms and the dysregulation of epigenetic control has been frequently associated with cancer8. Epigenetic modifications including DNA methylation and histone modification serve as a contributor to carcinogenesis, driving the transformation of normal cells into malignant cells together with genetic mutations, resulting in the onset and development of tumor9, 10, 11, 12, 13. Therefore, epigenetic modifications have been considered as effective targets for the treatment of cancer. Among the epigenetic targets, histone deacetylases (HDACs) are highly overexpressed in various cancer cells14,15, and HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) were proven to be effective in many biological processes of cancer cells, including cell differentiation induction, growth inhibition, apoptosis promotion, enhancement sensitivity to chemotherapy and angiogenesis inhibition16, 17, 18, 19. Up to now, four HDACi, namely vorinostat (1, SAHA), romidepsin (2, FK228), belinostat (3, PXD-101), and panobinostat (4, LBH589), have been approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and chidamide (5) was marketed in China for the treatment of hematologic cancer (Fig. 1A)20, 21, 22, 23. However, clinical studies of HDACi for the treatment of solid tumors were still disappointing24. Recent evidence showed that HDACi sensitized cancer cells when used in combination with various antitumor agents (e.g., DNA damaging agents and antimicrotubule agents), leading to synergistic cell apoptosis and improvement of therapeutic efficacy25. Thus, intensive interests have been focused on the design of HDAC-based multifunctional molecules to simultaneously interact with multiple targets in order to achieve superior efficacy and reduced side effects26,27. Among these targets, topoisomerase (TOP1 and/or TOP2) is a good starting point for multi-targeting drug design because the isoforms HDAC1-2 and TOP2 were co-localized in functional complexes28,29.

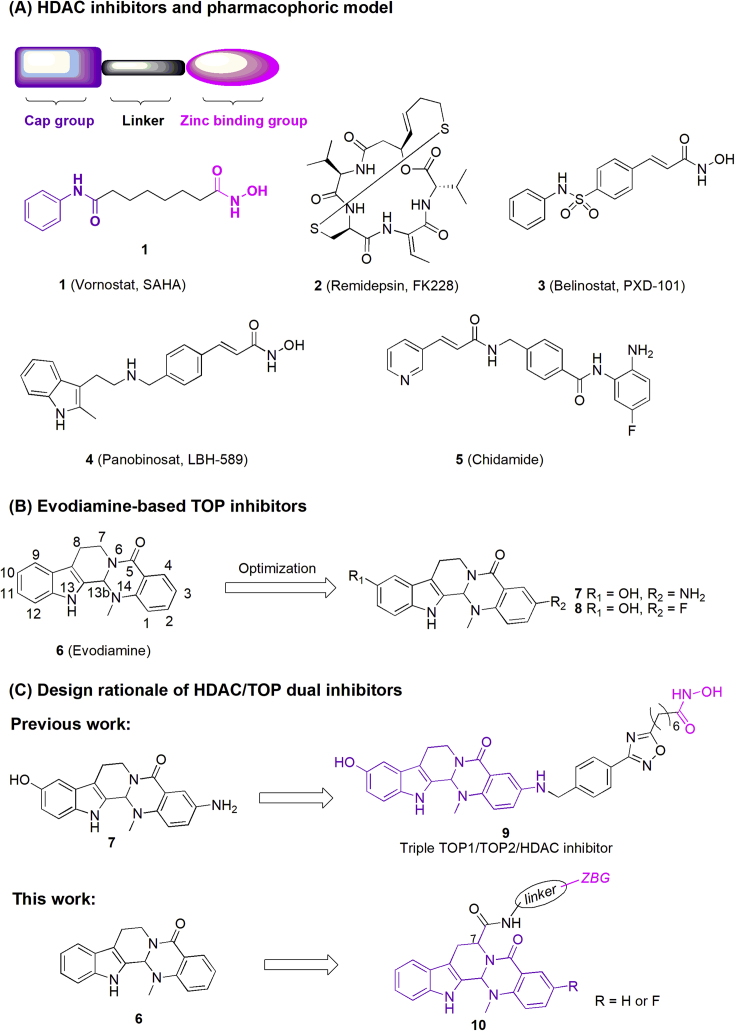

Figure 1.

(A) Chemical structures of approved HDAC inhibitors and their pharmacophore; (B) chemical structures of evodiamine and its potent derivatives; (C) design rationale of HDAC/TOP dual inhibitors.

Evodiamine (6, Fig. 1B) is a quinazolinocarboline alkaloid isolated from traditional Chinese herb Evodiae Fructus with diverse biological activities such as antitumor and anti-inflammatory efficacy30,31. In our previous studies, systemic structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies of evodiamine were performed and several highly active derivatives (compounds 7 and 8, Fig. 1B) with excellent antitumor potency were identified32, 33, 34, 35. Antitumor mechanism studies indicated that evodiamine and its derivatives were dual TOP1/TOP2 inhibitors. Based on the synergistic effect between TOP and HDAC inhibitors, a series of evodiamine–SAHA hybrids were designed and synthesized in our previous studies (Fig. 1C), in which compound 9 was confirmed to be a triple inhibitor of TOP1/2 and HDAC with good antitumor activity and remarkable pro-apoptotic effect36. This study validated the effectiveness of evodiamine-based bifunctional inhibitors as novel antitumor agents. However, poor in vivo antitumor efficacy of compound 9 limited its further development. In order to design new evodiamine-based HDAC/TOP dual inhibitors with improved in vivo antitumor potency, herein we designed and synthesized a series of novel evodiamine derivatives (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, they were proven to be selective dual HDAC1/TOP2 inhibitors with excellent in vitro and in vivo antitumor efficacy.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Design rationale

Generally, the pharmacophore of typical HDACi can be divided into three parts: a zinc-binding group (ZBG, ortho-aminobenzamide or hydroxamic acid), a recognition cap group and a hydrophobic linker (Fig. 1A). Previously, evodiamine-based TOP/HDAC inhibitors were designed by attaching the ZBG at the C3-amino of compound 7 through various linkers (Fig. 1C). It was reported that the introduction of side chain at the C7 position was favorable for developing potent evodiamine derivatives37,38. Inspired by these results, a series of novel evodiamine derivatives, characterized by bearing various linkers and ZBGs at the C7 (compounds 20a, 20b, 25a, 25b, 30a, 30b, 32 and their epimers) were designed, synthesized and assayed. Moreover, ZBG-containing side chains were also introduced at the C10 and N14 position of evodiamine (compounds 37 and 46, Supporting Information Schemes S1 and S2) to investigate the effect of connection position on the activity.

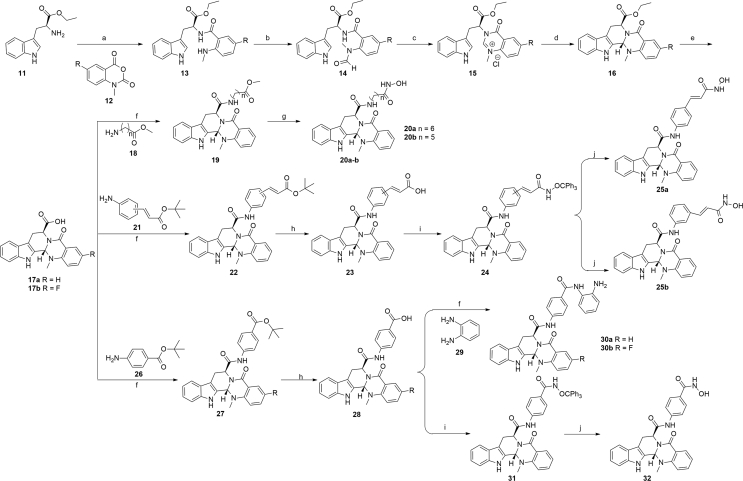

2.2. Chemistry

The chemical synthesis of the target compounds containing C7 substituted linkers and ZBGs is described in Scheme 1, and the compounds bearing linkers and ZBGs on C10 and N14 position (compounds 37 and 46) were depicted in Schemes S1 and S2. As shown in Scheme 1, starting from l-tryptophan ethyl ester hydrochloride (11) and 12, the key intermediate 17a was synthesized via five steps according to the literature procedures, with C13 b S configuration of 17a as the main product39. Then, compounds 20a and 20b were prepared via the condensation and ammonolysis reaction. Using the similar protocol, compounds 25a, 25b, 30a, 30b and 32 were prepared. The enantiomeric compounds of 20a, 20b, 25a, 25b, 30a and 32 were synthesized by using the d-tryptophan ethyl ester hydrochloride as the starting material (ent-20a, ent-20b, 25a, 25b, 30a and 32).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of target compounds. Reagents and conditions: (a) pyridine, NaHCO3, 12 h, 44%–57%; (b) HCOOH, (Ac)2O, THF, 2 h, 56%–76%; (c) dioxane, HCl, 6 h; (d) pyridine, reflux, 8 h, 78%–86%, over two steps; (e) LiOH, THF, H2O, reflux, 4 h, 88%–95%; (f) DIPEA, HATU, DMF, 4 h, 66%–79%; (g) NH2OK, anhydrous CH3OH, 1 h, 56%–85%; (h) 50% TFA in dry CH2Cl2, r.t., 2 h, 53%–65%; (i) NH2OCPh3, DIPEA, HATU, DMF, 4 h, 46%–68%; (j) BF3⋅Et2O, dry CH2Cl2, r.t., 2 h, 38%–56%.

2.3. In vitro HDAC1 inhibition

Initially, the inhibitory activity of target compounds against human recombinant HDAC1 enzyme was tested using the method previously described by Bradner et al.40 Compound 1 was used as the reference drug. As depicted in Table 1, most of compounds bearing C7 substitutions exhibited good to excellent inhibitory activity toward HDAC1, while the compounds containing C10 or N14 substitutions almost lost the HDAC1 inhibitory activity (Supporting Information Table S1), suggesting that substitutions on C7 position were more favorable than that of on C10 and N14 position. More specifically, for the compounds containing alkyl linkers, compounds 20a and 20b bearing five or six methylene showed nanomolar inhibitory activity against HDAC with the IC50 value of 27 and 53 nmol/L, respectively. Compounds 25a, 25b, ent-25a and ent-25b with N-hydroxycinnamamide moiety showed slightly decreased inhibitory activity. Furthermore, compounds containing the ortho-aminoanilide ZBG exhibited weaker potency than those with hydroxyamic acid (30a vs. 32). Moreover, the introduction of 3-fluoro group on compound 30a led to decreased activity. Interestingly, 7R,13bR-enantiomers seemed to be slightly more active than the 7S,13bS-enantiomers.

Table 1.

In vitro HDAC1 inhibition and antitumor activity of target compounds.

| Compd. | C7 Config. | C13b Config. | IC50 (nmol/L) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDAC1 | HCT116 | MCF-7 | A549 | |||

| 20a | S | S | 27 ± 2.3 | 7.2 ± 0.52 | 15 ± 2.5 | 27 ± 2.1 |

| ent-20a | R | R | 13 ± 1.4 | 10 ± 1.1 | 9.7 ± 8.0 | 19 ± 1.8 |

| 20b | S | S | 53 ± 4.5 | 11 ± 1.3 | >50 | >50 |

| ent-20b | R | R | 15 ± 1.2 | 16 ± 1.7 | 34 ± 3.5 | >50 |

| 25a | S | S | 89 ± 6.2 | 0.63 ± 0.52 | 3.0 ± 0.25 | 10 ± 1.2 |

| ent-25a | R | R | 18 ± 1.6 | 0.53 ± 0.45 | 1.6 ± 0.14 | 2.8 ± 0.22 |

| 25b | S | S | 31 ± 2.3 | 0.52 ± 0.36 | 2.2 ± 0.18 | 15 ± 1.4 |

| ent-25b | R | R | 10 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.28 | 12 ± 1.5 | 20 ± 2.4 |

| 30a | S | S | 160 ± 15 | 1.6 ± 0.15 | 18 ± 2.0 | 7.8 ± 0.65 |

| ent-30a | R | R | 22 ± 2.1 | 2.9 ± 2.0 | 17 ± 1.8 | 5.4 ± 0.48 |

| 30b | S | S | 180 ± 20 | 2.4 ± 0.22 | >50 | 7.9 ± 0.68 |

| 32 | S | S | 260 ± 24 | 2.2 ± 0.18 | 13 ± 1.4 | 11 ± 1.2 |

| ent-32 | R | R | 10 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.13 | 5.3 ± 0.50 | 12 ± 1.5 |

| 1 | – | – | 39 ± 2.6 | 3.7 ± 0.30 | 4.8 ± 0.41 | 4.9 ± 0.45 |

| 6 | – | – | – | >100 | >50 | >50 |

| 1 + 6 (1:1) | – | – | – | 2.8 ± 0.54 | 3.5 ± 0.32 | 3.7 ± 0.24 |

–Not applicable.

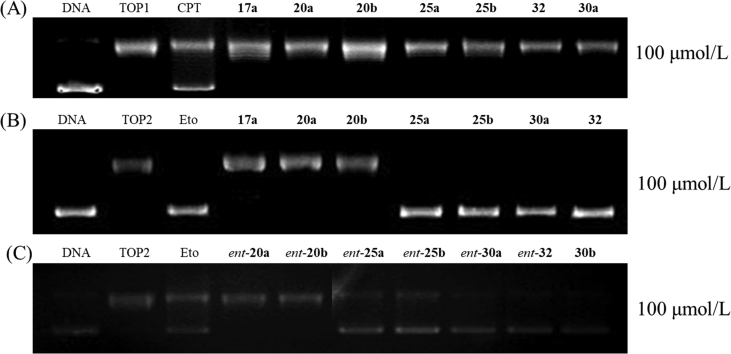

2.4. TOP inhibitory activity

Previously, evodiamine and its derivatives were identified as TOP1/TOP2 dual inhibitors by biological assays in combination with computational target prediction calculations32,33. Herein, we investigated the TOP inhibitory activity of the target compounds using TOP1- and TOP2-mediated pBR322 DNA relaxation assays (Fig. 2). Camptothecin (CPT, a TOP1 inhibitor) and etoposide (Eto, a TOP2 inhibitor) were used as the reference drugs. Treatment of DNA with TOP1 led to an extensive DNA relaxation (Fig. 2A, lane 2) and addition of CPT resulted in an obviously supercoiled DNA accumulation (Fig. 2A, lane 3). Unexpectedly, no supercoiled DNA bands were observed for the tested compounds (Fig. 2A, lanes 4–10) at the concentration of 100 μmol/L, indicating that they lost inhibitory activity against TOP1. As depicted in Fig. 2B and C, compounds containing alkyl linkers (20a, 20b and their epimers) were also inactive against TOP2 at the concentration of 100 μmol/L (lanes 5 and 6). Instead, compounds with aromatic ring linkers (25a, 25b, 30a, 32 and their epimers) showed remarkable TOP2 inhibitory activities at the concentration of 100 μmol/L (Fig. 2B, lanes 7–10, and Fig. 2C, lanes 4–10) and 50 μmol/L (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Similarly, compounds 37 and 46 showed inhibitory activity against TOP2 at 50 μmol/L (Supporting Information Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Effect of the target compounds on TOP relaxation activity. (A) TOP1 relaxation activity of compounds at the concentration of 100 μmol/L. Lane 1, supercoiled plasmid DNA; lane 2, DNA + TOP1; lane 3, DNA + TOP1+CPT; lanes 4–10, DNA + TOP1+target compounds (17a, 20a, 20b, 25a, 25b, 32 and 30a). (B) TOP2 relaxation activity of compounds at the concentration of 100 μmol/L. Lane 1, supercoiled plasmid DNA; lane 2, DNA + TOP2; lane 3, DNA + TOP2+Eto; lanes 4–10, DNA + TOP2+compounds (17a, 20a, 20b, 25a, 25b, 30a and 32). (C) Lanes 1–3 are equally as the (B); lanes 4–10, DNA + TOP2+compounds (ent-20a,ent-20b, ent-25a,ent-25b, ent-30a, ent-32 and 30b).

2.5. In vitro cell viability assay

Antiproliferative activities of the target compounds were tested against human cancer cell lines HCT116 (colon cancer), MCF-7 (breast cancer) and A549 (lung cancer) by CCK8 assays, using compounds 1 and 6 as the positive controls. From the results listed in Table 1, the majority of the compounds bearing linkers and ZBGs at C7 position of evodiamine skeleton showed moderate to good antitumor activity. In general, HCT116 cell line exhibited more sensitive to the target compounds than A549 and MCF-7 cell lines, with the IC50 values in the range of 0.52–16 μmol/L. For the compounds bearing long alkyl chain as the linker, the antiproliferative activity was changed with the length of the carbon chain (20a, 20b, ent-20a and ent-20b). Compounds with seven methylene units (20a and ent-20a) only showed moderate antitumor potency against the three tested cell lines (IC50 range: 7.2−27 μmol/L). Shortening linker length to six methylene units (20b and ent-20b) resulted in decrease or even loss of anticancer activity. Besides, the 7S,13bS-evodiamine derivatives seemed to be more active than their corresponding epimers (20a vs. ent-20a, 20b vs. ent-20b). When the alkyl chains were replaced by cinnamide, antitumor activities of compounds 25a, 25b, ent-25a and ent-25b were significantly improved. In particular, compounds 25a, 25b, and ent-25a showed the best antitumor activities against the HCT116 cell line, which were much more potent than positive controls 1, 6 and their combination. Compounds bearing ortho-aminoanilide ZBG maintained potent antitumor activity against HCT116 (30a, IC50 = 1.6 μmol/L), whereas its 3-fluoro derivative (30b, IC50 = 3.6 μmol/L) was less active. In contrast, C10 and N14 substituted compounds (37 and 46) were inactive against the three tested cancer cell lines (Table S1).

On the basis of the HDAC and TOP inhibitory activity, antitumor potency and structural diversity, compounds 25a and 30a were chosen for further antitumor evaluations. First, they were assayed for inhibitory activity against hematological cell lines (HL60, K562 and HEL). The results indicated that compounds 25a (IC50 range: 0.34–1 μmol/L) and 30a (IC50 range: 0.56–1.9 μmol/L) exhibited potent antiproliferative activity toward hematological cell lines (Supporting Information Table S2). Second, their inhibitory activity against human normal cell line HUVEC was determined. Both of them showed low cytotoxicity and compound 30a (IC50 = 48 μmol/L) was highly selective between human cancer and normal cell lines (Table S2).

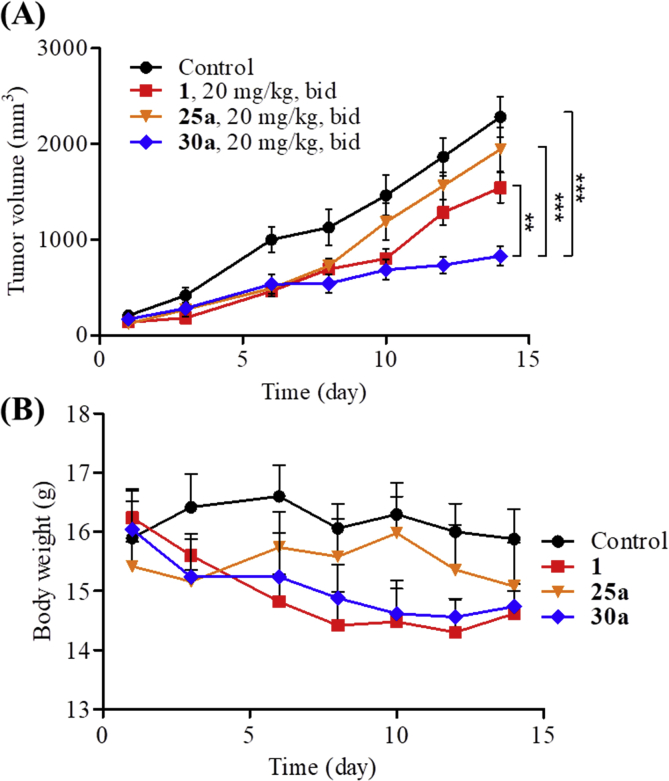

2.6. Preliminary in vivo antitumor activity of compounds 25a and 30a

To evaluate the in vivo antitumor effects of compounds 25a and 30a, a subcutaneous HCT116 xenograft model was established in BALB/c nude mice, using compound 1 as the positive control. Female BABL/c nude mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 400 × 104 HCT116 colon cancer cells per mouse. After two weeks later (tumor volumes reaching to about 100 mm3), mice were divided randomly into four groups (five mice per group) and were administered with vehicle, 25a (20 mg/kg, bid), 30a (20 mg/kg, bid), and compound 1 (20 mg/kg, bid) by intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) for 14 consecutive days, respectively. The changes in body weight and tumor size were measured every three days during the treatment. As shown in Fig. 3, compound 30a exhibited excellent tumor growth inhibition (TGI = 63.6%), which was much more effective than compound 1 (TGI = 32.4%). In contrast, compound 25a was totally inactive (TGI = 2.2%). To explain why compounds 25a and 30a had different in vivo antitumor activities, the in vitro metabolic stabilities were investigated by liver microsome assay. As depicted in Table 2 and Supporting Information Fig. S3, the terminal half-life (t1/2) of compound 30a was 34.95 min, which was almost 3-fold longer than that of compound 25a (t1/2 = 9.86 min). Based on the in vivo results, compound 30a was chosen for further biological evaluations.

Figure 3.

Preliminary in vivo anticancer activity of compounds 25a and 30a. (A) Antitumor potency of compounds 25a and 30a in the HCT116 xenograft models implanted in BALB/c nude mice. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 5 per group). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, determined with Student's t test. (B) The change of body weight during the test.

Table 2.

The mice microsomal stability of compounds 25a and 30a.

Half-life.

Clearance.

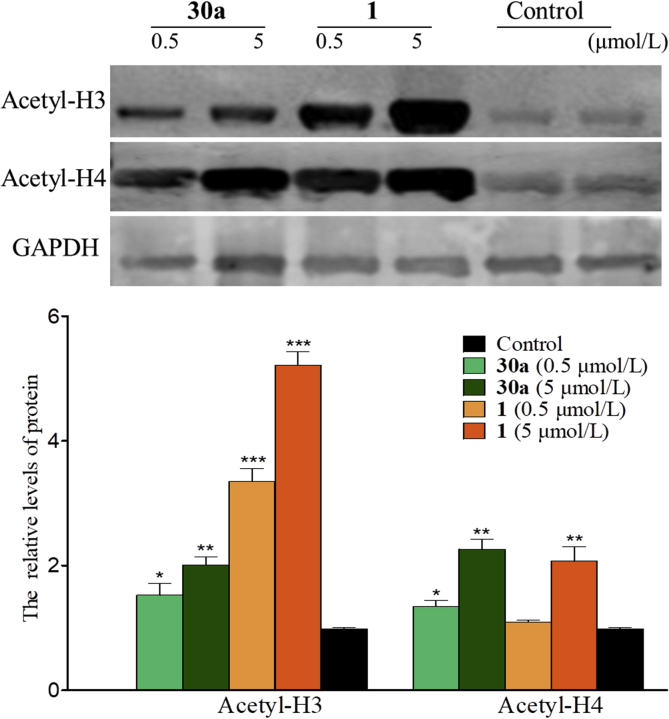

2.7. In vitro HDAC isoform selectivity and cellular HDAC1 inhibition of compound 30a

To investigate the HDAC isoform selectivity, compound 30a was examined against representative HDAC isoforms. As depicted in Table 3, compound 30a showed the best inhibitory potency against HDAC1 (IC50 = 0.16 μmol/L). In contrast, it exhibited relatively weak HDAC2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 11 inhibitory activity (IC50 range: 5.5 to >100 μmol/L). Furthermore, evaluation of cellular HDAC1 inhibition of compound 30a was performed. HCT116 cells were treated with compound 30a at the concentrations of 0.5 and 5 μmol/L for 24 h. Compound 1 at the same concentration or vehicle (DMSO) was employed as the controls. As shown in Fig. 4, compound 30a exhibited the hyperacetylation effect of histone 3 and 4 (Acetyl-H3 and Acetyl-H4) in a dose-dependent manner.

Table 3.

HDAC isoform profiling of compound 30a.

| Isoform | HDAC class | IC50 (μmol/L) |

|---|---|---|

| HDAC1 | I | 0.16 ± 0.015 |

| HDAC2 | I | 10 ± 1.4 |

| HDAC3 | I | 27 ± 4.8 |

| HDAC4 | IIa | >100 |

| HDAC6 | IIb | >100 |

| HDAC8 | I | >100 |

| HDAC10 | IIb | 5.5 ± 1.5 |

| HDAC11 | IV | >100 |

Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Figure 4.

Western blot probing for acetylated histones H3 and H4 in HCT116 cells treated with compounds 1 and 30a. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control group, determined with Student's t test. Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

2.8. DNA damage effects of compound 30a

Due to the TOP2–DNA cleavage complex stabilization effect of compound 30a in TOP2-mediated pBR322 DNA relaxation assays, we investigated the DNA damage effect of compound 30a by measuring the expression of γH2AX using Western blot41. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S4, after the treatment with compounds 1, 6 and 30a at concentrations of 0.5 and 5 μmol/L for 24 h, compound 30a increased the expression of γH2AX in HCT116 cells. In contrast, incubation with compounds 1 and 6 led to no increase of the expression of γH2AX. The results indicated that compound 30a might exhibit cellular damage activity through inhibiting the TOP2 activity, while compounds 1 and 6 had no such effect.

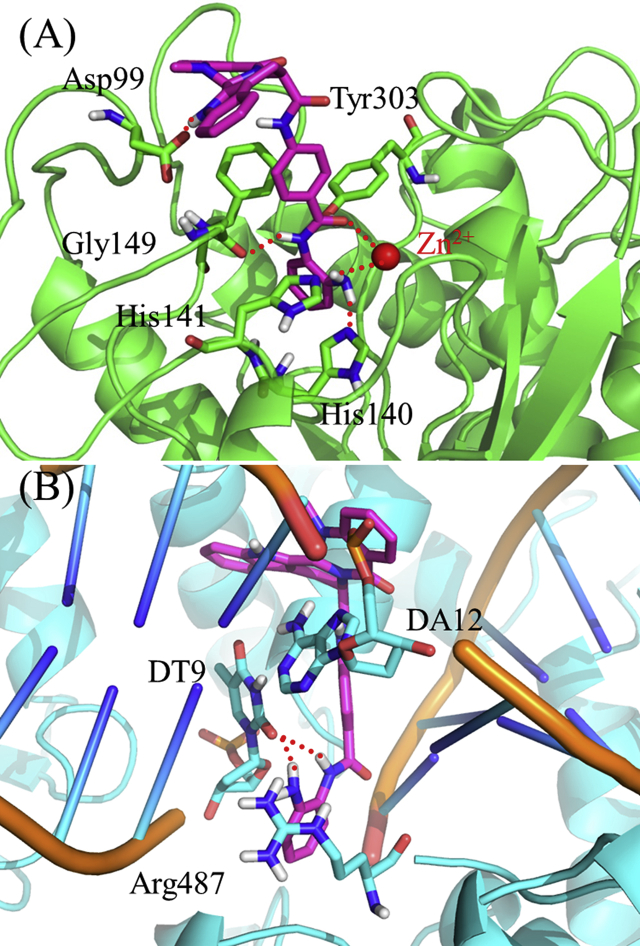

2.9. Modeling studies of compound 30a with HDAC1 and TOP2α

To determine the binding mode of compound 30a with HDAC1 (PDB ID: 4BKX)42 and TOP2α (PDB ID: 5GWK)43, molecular docking study was performed. As shown in Fig. 5A, the ZBG and evodiamine skeleton of compound 30a formed main interactions with HDAC1. The terminal NH2 group was found to form two hydrogen bonds with His140 and His141, respectively. The NH group on the N-(2-aminophenyl)benzamide moiety formed another hydrogen bond with Gly149. More importantly, both of the phenyl group and carbonyl group on the N-(2-aminophenyl)benzamide moiety formed coordination interactions with Zn2+, and the carbonyl group formed a hydrogen bond with Tyr303. Besides, π–π interactions were observed between the indole moiety (rings A and B) of the evodiamine skeleton and the residues of Phe150 and Phe205, and the 13-NH group formed a hydrogen bond with Asp99. As for TOP2α, compound 30a bound to the TOP2α-DNA cleavage site (Fig. 5B). The NH2 group and the NH group in the N-(2-aminophenyl)benzamide moiety formed a hydrogen bond with the DNA, respectively. Besides, the π–π interactions between the phenyl group on the N-(2-aminophenyl)benzamide moiety and Arg487 was observed. The quinazoline moiety in the evodiamine skeleton was found to form additional π–π interactions with the adenine base of DNA.

Figure 5.

Molecular docking of compound 30a in the active site of HDAC1 (PDB ID: 4BKX, A) and TOP2α-DNA cleavage site (PDB ID: 5GWK, B). Hydrogen bonds are indicated with dashed lines. The carbons of compound 30a are colored in purple, nitrogen atoms in blue, and oxygen atoms in red.

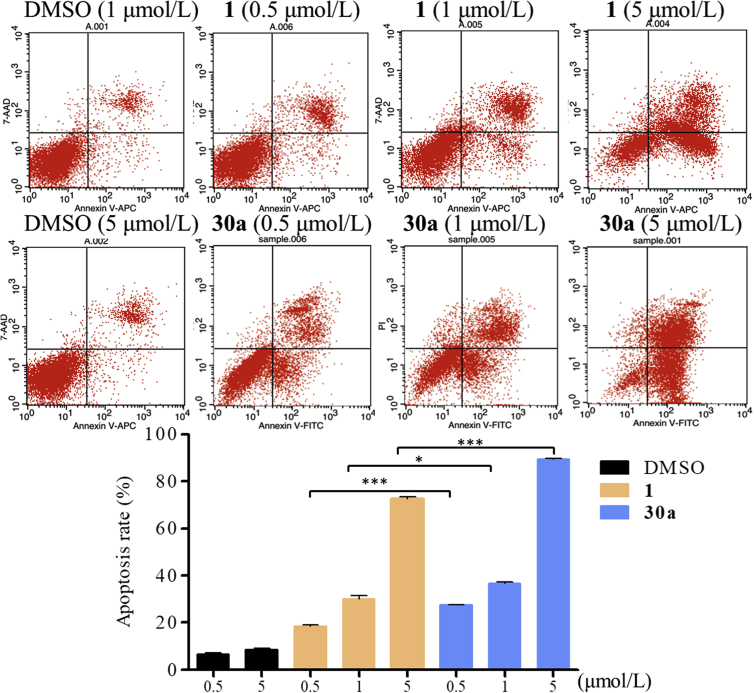

2.10. Compound 30a induces apoptosis in HCT116 cells

To determine whether compound 30a could induce cancer cell apoptosis, flow cytometry analysis and FITC-annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) assay were performed, and the percentages of apoptotic cells were evaluated. HCT116 cells were incubated with the test compounds (1 or 30a) at the concentrations of 0.5, 1 and 5 μmol/L. As shown in Fig. 6, compound 30a significantly induced the apoptosis in HCT116 cells in a dose-dependent manner. After calculating the apoptotic cells treated with compound 30a, the percentage were 27.6%, 37.1%, and 88.8%, respectively, which were much higher than compound 1 at the same concentration (18.3%, 39.8% and 71.4%, respectively, P < 0.05), indicating the notable cellular potency of compound 30a.

Figure 6.

Compound 30a induced HCT116 cell apoptosis in vitro. HCT116 cells were treated with different concentrations of compounds 1 and 30a for 48 h, followed by flow cytometry. Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

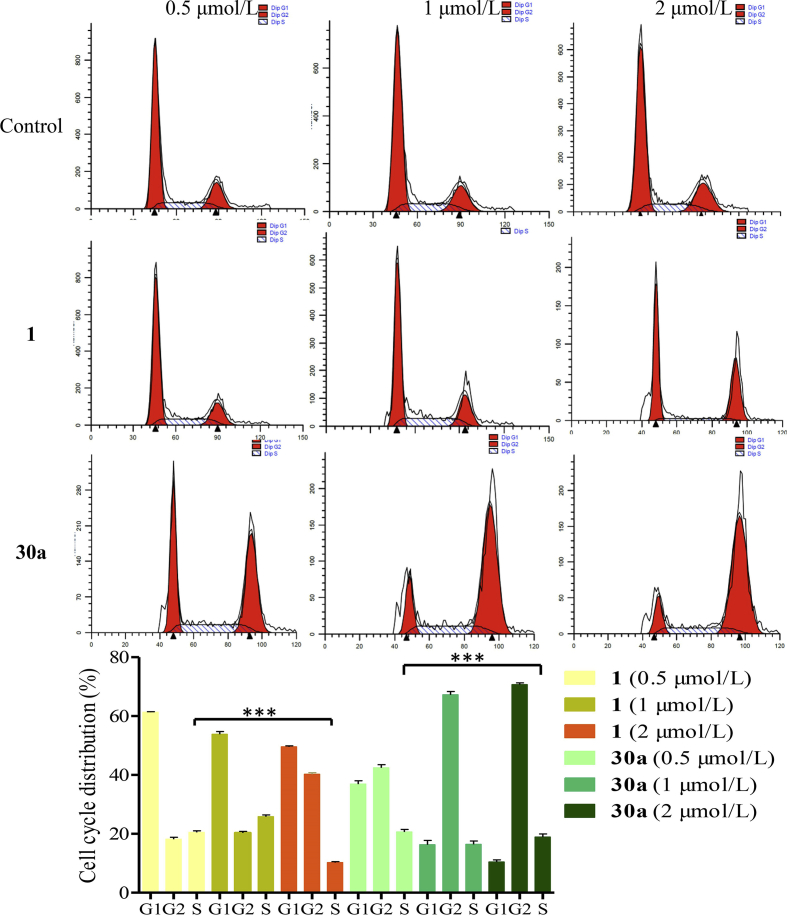

2.11. Compound 30a arrests the HCT116 cell cycle at the G2/M phase

To investigate the effect of compound 30a on cell cycle progression in HCT116 cells, the flow cytometric assay was performed, using equivalent DMSO and compound 1 as the control (Fig. 7). After incubating with compound 30a at 0.5, 1 and 2 μmol/L, the ratios of cells at the G2/M phase were changed dramatically (32.9%, 36.4% and 38.8%, respectively). Besides, the ratios of cells exposed to compound 1 at G2/M phase of cell cycle were 17.9%, 20.1% and 38.9%, respectively. Instead, the ratios of HCT116 cells incubated with vehicle at the G2/M phase were 10.8%. Compared to the control population, compound 30a significantly arrested the HCT116 cell cycle at the G2/M phase.

Figure 7.

Compound 30a arrests cell cycle at the G2/M Phase. HCT116 cells exposed to compound 30a (0.5, 1 and 2 μmol/L) for 48 h were examined by flow cytometry assay. Cells incubated with compound 1 were used as the control group. Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). ***P < 0.001, determined with Student's t test.

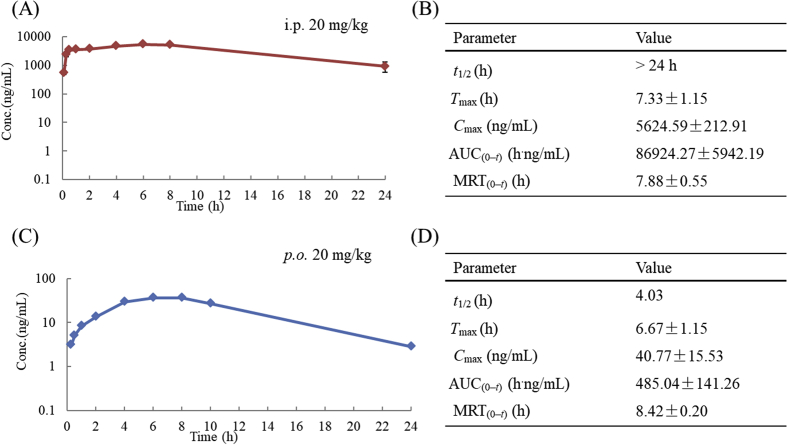

2.12. Preliminary pharmacokinetic profiles of compound 30a

Due to its good HDAC1/TOP2 inhibitory activity and potent antitumor efficacy, compound 30a was progressed into an in vivo pharmacokinetic study in Sprague−Dawley (SD) rats. As shown in Fig. 8, the half-life of compound 30a was more than 24 h when administered i.p. at 20 mg/kg. In contrast, when it was orally administered (p.o.) at 20 mg/kg, the half-life was reduced to 4.03 h. The area under the curve (AUC) of compound 30a under i.p. or p.o. administration was 86,924.27 and 485.04 h⋅ng/mL, respectively.

Figure 8.

PK parameters of compound 30a under i.p. administration (A) and (B), and p.o. administration (C) and (D).

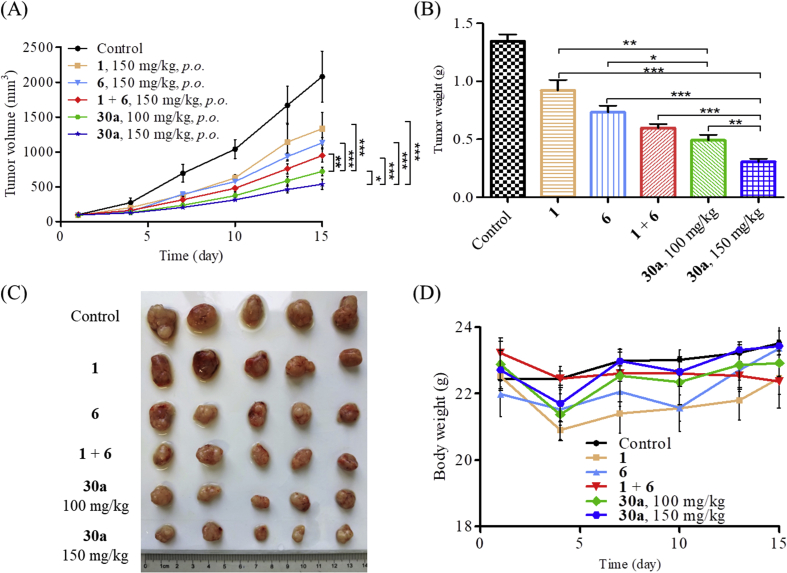

2.13. In vivo antitumor activity of compound 30a

Due to the suitable half-life of 30a, it was feasible to examine the antitumor activity orally. We established a HCT116 xenograft BALB/c nude mice model to evaluate the in vivo antitumor potency of compound 30a. Compound 30a was administrated orally (100 or 150 mg/kg, bid) over 21 days. Compounds 1 (150 mg/kg, bid), 6 (150 mg/kg, bid) and their combination were used as reference drugs. The changes in body weights and tumor volumes were monitored every three days during the treatment. As shown in Fig. 9, treatment with compound 30a (150 mg/kg, bid) led to significant tumor growth inhibition (TGI = 75.2%), which was much more potent than compounds 1 (TGI = 40.81%), 6 (TGI = 45.53%) and their combination (TGI = 54.5%). Importantly, even at lower dosage (100 mg/kg, bid), compound 30a still exhibited potent in vivo antitumor efficacy (TGI = 65.42%). Moreover, there was no significant difference in body weight during the test, suggesting a low toxicity of compound 30a. The in vivo studies clearly demonstrated that the evodiamine-based dual HDAC1/TOP2 inhibitors 30a possessed excellent therapeutic advantages over single HDAC inhibitor and TOP inhibitor.

Figure 9.

Compound 30a suppressed tumor growth in vivo. (A) The efficacy of compound 30a in an implanted HCT116 xenograft model. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, determined with Student's t test. (B) Tumor weight. (C) Picture of dissected tumor tissue. (D) Body weight of the BALB/c nude mice in HCT116 xenograft model.

3. Conclusions

In summary, a series of novel evodiamine-based HDAC1/TOP2 dual inhibitors were designed and synthesized. Among them, compound 30a exhibited excellent in vitro and in vivo antitumor efficacy. It effectively induced the apoptosis with a G2/M cell cycle arrest in HCT116 cells. Importantly, compound 30a was superior to HDAC inhibitor 1, TOP inhibitor 6 and their combination in vivo antitumor potency in HCT116 bearing xenograft models (TGI = 75.2%, 150 mg/kg, p.o., bid) with no significant toxicity. These studies highlighted the therapeutic potential of selective HDAC1/TOP2 dual inhibitors for the treatment of colon cancer. Also, the design of multi-targeting inhibitors provided a promising approach to improve the in vivo activity for evodiamine derivatives. Further structural optimizations of 30a will be focused on improving the oral bioavailability and in vivo antitumor potency.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. Materials and instruments

All starting materials and solvents were obtained commercially from Aladdin (Shanghai, China) and Sigma−Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany) without further purification. The Bruker AVANCE300, AVANCE500, or AVANCE600 spectrometers (Bruker Company, Leipzig, Germany) were applied to record 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra, using TMS as an internal standard and DMSO-d6 as solvents. Chemical shifts are reported in δ unit (ppm). Mass spectra (MS) were recorded on an Esquire 3000 LC−MS mass spectrometer (Bruker Company, Leipzig, Germany). Silica gel TLC was performed to monitor reactions using silica gel GF-254 (Haiyang Chemical, Qingdao, China) and visualized under UV light at 254 and 365 nmol/L. Purity of the compounds was determined by HPLC analysis (Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity, Palo Alto, USA). The conditions were: mobile phase: methanol/aqueous solution=60:40; rate: 0.8 mL/min; wavelength: 254 nmol/L; pressure: 75−134 kg; temperature: 25 °C. All compounds were of >98% purity.

4.1.2. Synthesis procedures

4.1.2.1. (7S,13bS)-N-(7-(Hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,13,13b,14-hexahydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (20a)

Compound 17a was synthesized via five steps according to the literature procedures38. To a solution of compound 17a (0.1 g, 0.26 mmol) in 5 mL anhydrous DMF was added DIPEA (99 μL, 0.52 mmol), HATU (0.16 g, 0.28 mmol) and compound 18a (0.07 g, 0.26 mmol), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h. Then, the resulting solution was poured into ice water and extracted with EtOAc. The organic phase was combined and dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography hexane/EtOAc = 2:1 to give intermediate 19a (0.09 g, 68%) as off-white solid. To a freshly prepared hydroxylamine solution in anhydrous MeOH was compound 19a (0.09 g, 0.2 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h, and MeOH was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was adjusted to pH 7 with acetic acid. After filtration, the filtrate was dried to give compound 20a as off-white solid (Yield: 51%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.35 (s, 1H), 10.28 (s, 1H), 8.62 (s, 1H), 7.97 (t, J = 5.76 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (dd, J = 1.22, 7.93 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (t, J = 7.62 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 7.93 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 7.93 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 7.93 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (t, J = 7.32 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (t, J = 7.32 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 7.32 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (s, 1H), 5.34 (d, J = 5.93 Hz, 1H), 3.37 (d, J = 15.52 Hz, 1H), 3.17 (s, 1H), 3.10 (dd, J = 5.94, 15.44 Hz, 1H), 2.88–2.91 (m, 2H), 2.51 (s, 3H), 1.84 (t, J = 7.38 Hz, 2H), 1.28–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.18–1.24 (m, 3H), 1.00–1.04 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 170.38, 169.00, 164.10, 150.55, 136.80, 133.20, 128.30, 127.99, 125.62, 122.25, 122.00, 121.92, 120.66, 118.85, 118.21, 111.52, 108.77, 67.72, 52.89, 38.51, 35.59, 32.15, 28.83, 28.19, 25.72, 24.87, 23.64. ESI-MS (m/z): 490.58 [M+H]+.

Compounds 20b, ent-20a and ent-20b were obtained from a similar protocol described for compound 20a.

4.1.2.2. (7S,13bS)-N-(6-(Hydroxyamino)-6-oxohexyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,13,13b,14-hexahydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (20b)

Off-white solid (Yield: 41%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.34 (s, 1H), 10.25 (s, 1H), 7.98 (t, J = 5.70 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (dd, J = 1.36, 7.88 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (t, J = 7.61 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.15 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.15 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.15 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (t, J = 7.61 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (t, J = 7.61 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (t, J = 7.61 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (s, 1H), 5.33 (d, J = 4.89 Hz, 1H), 3.09–3.11 (m, 1H), 2.85–2.91 (m, 2H), 2.50 (s, 3H), 1.78 (t, J = 7.49 Hz, 1H), 1.27–1.32 (m, 2H), 1.18–1.23 (m, 2H), 0.98–1.02 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 170.50, 169.21, 164.27, 150.44, 136.68, 133.24, 128.36, 127.93, 125.57, 122.27, 121.99, 121.84, 120.57, 118.90, 118.26, 108.72, 67.81, 52.92, 38.51, 35.51, 32.06, 28.60, 25.68, 24.66, 23.65. ESI-MS (m/z): 476.49 [M+H]+.

4.1.2.3. (7S,13bS)-N-(4-((E)-3-(Hydroxyamino)-3-oxoprop-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,13,13b,14-hexahydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (25a)

Intermediate 22a was obtained from the similar protocol described for compound 19a. To a solution of compound 22a (0.1 g, 0.18 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) was added TFA (2 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. After the reaction, the resulting mixture was concentrated, and the residue was adjusted to pH 4 with NaHCO3 solution. The precipitate was filtered and dried to afford the intermediate 23a as yellow solid (0.07 g, Yield: 78%). Intermediate compound 23a (0.07 g, 0.14 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DMF (5 mL), and Ph3ONH2 (0.05 g, 0.17 mmol), DIPEA (46 μL, 0.28 mmol) and HATU (0.06 g, 0.17 mmol) were added, and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 4 h. After the reaction, the resulting mixture was poured into ice water (40 mL) and filtered. The precipitate was dried and purified by column chromatography (hexane/EtOAc = 2:1) to give intermediate 24a (0.06 g, 57%) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.44 (s, 1H), 10.43 (s, 1H), 7.95 (dd, J1 = 7.77 Hz, J2 = 1.37 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (t, J = 7.77 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.17 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.17 Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.40 (m, 15H), 7.21 (t, J = 6.66 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (t, J = 7.27 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 7.27 Hz, 1H), 6.25 (s, 1H), 5.59 (d, J = 7.87 Hz, 1H), 4.28 (t, J = 6.98 Hz, 1H), 3.44 (d, J = 15.63 Hz, 1H), 2.58 (s, 3H). ESI-MS (m/z): 748.26 [M–H]−. To a stirred solution of compound 24a (0.06 g, 0.08 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) was added dropwise a solution of BBr3⋅Et2O (0.1 mL) at room temperature for 2 h. After the reaction, solvent was evaporated in vacuo, and the resultant residue was washed with brine and filtrated. The filtrate was collected and dried to give target compound 25a as yellow solid (Yield: 74%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.45 (s, 1H), 10.67 (s, 1H), 10.46 (s, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 6.31 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (t, J = 7.84 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.68 Hz, 3H), 7.46 (d, J = 8.68 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.13 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 15.35 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 7.86 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (t, J = 7.31 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (t, J = 7.31 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (d, J = 15.35 Hz, 1H), 6.27 (s, 1H), 5.61 (d, J = 6.58 Hz, 1H), 2.59 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 170.35, 164.71, 150.81, 139.79, 137.86, 136.83, 133.49, 129.75, 128.29, 128.11, 127.99, 127.69, 127.50, 125.50, 122.46, 122.09, 121.61, 120.94, 119.05, 118.93, 118.32, 117.35, 111.59, 107.95, 68.02, 53.43, 35.48, 23.64. ESI-MS (m/z): 508.56 [M+H]+. HPLC purity: 96.5%.

Compounds 25b, 32, ent-25a, ent-25b and ent-32 were obtained from to a similar protocol described for compound 25a.

4.1.2.4. (7S,13bS)-N-(3-((E)-3-(Hydroxyamino)-3-oxoprop-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,13,13b,14-hexahydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (25b)

Yellow solid (Yield: 87%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.44 (s, 1H), 10.64 (s, 1H), 10.45 (s, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.86 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (t, J = 8.42 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.86 Hz, 3H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.42 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.35 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (t, J = 7.35 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 7.70 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (t, J = 7.35 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (t, J = 7.41 Hz, 1H), 6.3 (d, J = 16.17 Hz, 1H), 6.23 (s, 1H), 5.57 (d, J = 6.96 Hz, 1H), 2.55 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 170.34, 164.67, 150.76, 147.67, 143.76, 128.96, 128.31, 127.73, 127.51, 126.64, 126.20, 125.52, 122.48, 122.12, 121.59, 120.96, 119.08, 118.37, 111.57, 107.90, 80.60, 68.05, 55.79, 35.44, 28.86, 23.70. ESI-MS (m/z): 508.46 [M+H]+.

4.1.2.5. (7S,13bS)-N-(4-((2-Aminophenyl)carbamoyl)phenyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,13,13b,14-hexahydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (30a)

Intermediate 27a was obtained from a similar protocol described for compound 19a. To a solution of compound 27a (0.25 g, 0.48 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) was added TFA (2 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. After the reaction, solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the resultant residue was adjusted to pH 4 with NaHCO3 solution and filtrated. The precipitate was collected and washed with water and dried to yield intermediate 28a (0.18 g, Yield: 80%) as yellow solid. Intermediate compound 28a (0.17 g, 0.15 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DMF (5 mL), and DIPEA (52 μL, 0.3 mmol), HATU (0.07 g, 0.18 mmol) and o-phenylenediamine (0.02 g, 0.18 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h. After the reaction, the resulting mixture was poured into ice water and extracted with EtOAc. The organic layers were combined and concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexane/EtOAc = 1:1) to give compound 30a (0.03 g, Yield: 35%) as yellow solid. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.45 (s, 1H), 10.57 (s, 1H), 9.54 (s, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.56 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 8.69 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.95 Hz, 3H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.83 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 7.83 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.83 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (t, J = 7.22 Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.01 (t, J = 7.58 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (t, J = 7.45 Hz, 1H), 6.74 (d, J = 7.94 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (t, J = 7.94 Hz, 1H), 6.24 (s, 1H), 5.61 (d, J = 6.45 Hz, 1H), 4.82 (s, 2H), 2.56 (s, 3H), 0.84 (t, J = 6.62 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 170.66, 164.64, 150.92, 142.98, 141.53, 136.96, 133.59, 129.00, 128.63, 128.33, 127.99, 126.61, 126.39, 125.52, 123.37, 122.50, 122.11, 121.58, 120.93, 119.00, 118.35, 118.17, 116.34, 116.16, 111.63, 107.92, 68.04, 64.95, 35.45, 31.24, 23.61, 15.16. HRMS (ESI, positive) m/z Calcd. for C33H29N6O3 [M+H]+: 557.2296; Found 557.2299. HPLC purity: 99.9%.

Compounds 30b, ent-30a were obtained from a similar protocol described for compound 30a.

4.1.2.6. (7S,13bS)-N-(4-((2-Aminophenyl)carbamoyl)phenyl)-3-fluoro-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,13,13b,14-hexahydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (30b)

Yellow solid (Yield: 32%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.47 (s, 1H), 10.57 (s, 1H), 9.54 (s, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.70 Hz, 2H), 7.64 (dd, J = 2.97, 8.66 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 8.66 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (d, J = 7.92 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 8.73 Hz, 1H), 7.38–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.11–7.15 (m, 2H), 7.02 (t, J = 7.64 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (t, J = 7.82 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 7.82 Hz, 1H), 6.57 (t, J = 7.82 Hz, 1H), 6.27 (s, 1H), 5.62 (d, J = 6.63 Hz, 1H), 4.84 (s, 2H), 3.47 (d, J = 16.07 Hz, 1H), 2.50 (s, 3H), 0.85 (t, J = 6.91 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 170.50, 164.87, 163.69, 158.77, 157.13, 147.28, 143.06, 141.42, 136.96, 129.01, 128.60, 127.79, 126.65, 126.49, 125.43, 124.21, 123.30, 122.119, 121.08, 120.91, 119.02, 118.36, 118.25, 116.47, 116.19, 113.60, 113.43, 111.66, 107.88, 68.33, 53.67, 35.83, 23.61. ESI-MS (m/z): 575.56 [M+H]+.

4.1.2.7. (7S,13bS)-N-(4-(Hydroxycarbamoyl)phenyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,13,13b,14-hexahydroindolo[2′,3':3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (32)

Yellow solid (yield: 81%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 11.44 (s, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 3.23 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.31 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.31 Hz, 2H), 7.59 (t, J = 8.31 Hz, 3H), 7.53 (t, J = 8.31 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 7.39 Hz, 2H), 7.29 (t, J = 7.39 Hz, 3H), 7.19 (d, J = 6.47 Hz, 2H), 7.10–7.14 (m, 2H), 6.24 (s, 1H), 5.59 (s, 1H), 2.55 (s, 3H), 2.38 (s, 1H). ESI-MS (m/z): 480.46 [M+H]+.

4.1.2.8. (7R,13bR)-N-(7-(Hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,8a,13,13a,13b,14-octahydroindeno[2′,1′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (ent-20a)

Light yellow solid (Yield: 55%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.37 (s, 1H), 10.30 (s, 1H), 8.64 (s, 1H), 8.00 (t, J = 5.84 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (dd, J = 1.12, 7.86 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (t, J = 7.59 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 7.59 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 7.59 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 7.74 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (t, J = 7.19 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (t, J = 7.19 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 7.19 Hz, 1H), 6.19 (s, 1H), 5.35 (d, J = 5.19 Hz, 1H), 3.73 (d, J = 13.85 Hz, 1H), 3.10–3.13 (m, 1H), 2.88–2.91 (m, 2H), 2.51 (s, 3H), 1.84 (t, J = 7.77 Hz, 2H), 1.28–1.33 (m, 2H), 1.18–1.23 (m, 2H), 1.00–1.04 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 150.54, 136.81, 133.19, 128.32, 128.03, 125.67, 122.26, 122.00, 121.94, 120.65, 118.84, 118.22, 111.52, 108.78, 67.73, 52.90, 38.51, 35.56, 32.15, 28.82, 28.15, 25.72, 24.87, 23.67. ESI-MS (m/z): 490.62 [M+H]+.

4.1.2.9. (7R,13bR)-N-(6-(Hydroxyamino)-6-oxohexyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,8a,13,13a,13b,14-octahydroindeno[2′,1′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (ent-20b)

Light yellow solid (Yield: 52%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.36 (s, 1H), 10.27 (s, 1H), 8.63 (s, 1H), 8.01 (t, J = 5.85 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (dd, J = 1.67, 7.94 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (t, J = 7.53 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 7.94 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.36 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.36 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (t, J = 7.68 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (t, J = 7.68 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 7.68 Hz, 1H), 6.19 (s, 1H), 5.39 (d, J = 6.50 Hz, 1H), 3.37 (d, J = 15.86 Hz, 1H), 3.09–3.12 (m, 1H), 2.88–2.90 (m, 2H), 2.51 (s, 3H), 1.80 (t, J = 7.49 Hz, 2H), 1.29–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.19–1.24 (m, 2H), 0.98–1.03 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 170.37, 169.01, 164.10, 150.53, 136.80, 133.19, 128.33, 128.05, 125.68, 122.26, 122.00, 121.93, 120.65, 118.85, 118.25, 111.53, 108.80, 67.73, 52.89, 38.52, 35.58, 32.07, 28.63, 25.71, 24.70, 23.64. ESI-MS (m/z): 476.56 [M+H]+.

4.1.2.10. (7R,13bR)-N-(4-((E)-3-(Hydroxyamino)-3-oxoprop-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,13,13b,14-hexahydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (ent-25a)

Yellow solid (Yield: 41%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.45 (s, 1H), 10.46 (s, 1H), 7.94 (d, J = 7.63 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (t, J = 7.63 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 7.83 Hz, 3H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.83 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 7.93 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (d, J = 15.87 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 7.93 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 7.93 Hz, 1H), 7.11–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.01 (t, J = 7.48 Hz, 1H), 6.25 (s, 1H), 5.59 (d, J = 6.27 Hz, 1H), 2.56 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 170.32, 164.56, 162.88, 150.77, 147.73, 139.84, 137.74, 136.90, 133.44, 129.74, 129.28, 128.99, 128.31, 128.08, 128.02, 127.73, 127.48, 126.59, 126.20, 125.53, 122.47, 122.07, 121.69, 120.99, 119.09, 119.00, 118.92, 118.38, 117.46, 111.60, 107.93, 68.06, 64.86, 53.40, 35.52, 23.67, 15.12. ESI-MS (m/z): 508.42 [M+H]+.

4.1.2.11. (7R,13bR)-N-(3-((E)-3-(Hydroxyamino)-3-oxoprop-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,13,13b,14-hexahydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (ent-25b)

Yellow solid (Yield: 38%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.45 (s, 1H), 10.41 (s, 1H), 7.94 (dd, J = 1.59, 7.74 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (s, 1H), 7.59 (t, J = 7.65 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 7.65 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 7.65 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 15.30 Hz, 2H), 7.27–7.31 (m, 4H), 7.20 (d, J = 7.47 Hz, 2H), 7.13–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.02 (t, J = 7.42 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (d, J = 16.01 Hz, 1H), 6.25 (s, 1H), 5.60 (d, J = 7.23 Hz, 1H), 3.45 (d, J = 15.91 Hz, 1H), 3.36–3.40 (m, 2H), 2.57 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 170.39, 164.58, 162.41, 150.77, 147.73, 139.32, 138.05, 136.89, 135.26, 133.44, 129.30, 128.99, 128.21, 127.99, 127.73, 127.48, 126.59, 125.54, 123.49, 122.50, 121.74, 121.05, 120.06, 119.22, 118.93, 116.45, 111.59, 107.98, 68.06, 64.86, 53.39, 35.53, 23.63, 15.12. ESI-MS (m/z): 508.39 [M+H]+.

4.1.2.12. (7R,13bR)-N-(4-((2-Aminophenyl)carbamoyl)phenyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,13,13b,14-hexahydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (ent-30a)

Yellow solid (Yield: 37%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.47 (s, 1H), 10.57 (s, 1H), 9.56 (s, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 9.46 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 9.46 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.54 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.83 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 8.54 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.54 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (t, J = 7.83 Hz, 1H), 7.12–7.22 (m, 2H), 7.03 (t, J = 7.07 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (t, J = 7.71 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 7.71 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (t, J = 7.71 Hz, 1H), 6.27 (s, 1H), 5.62 (d, J = 6.42 Hz, 1H), 4.91 (s, 1H), 2.57 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 170.56, 164.59, 150.78, 142.98, 141.53, 136.91, 133.47, 129.00, 128.62, 128.33, 128.01, 126.60, 126.30, 125.54, 123.46, 122.49, 122.09, 121.68, 121.01, 118.93, 118.40, 118.15, 116.29, 116.14, 111.62, 107.92, 68.06, 64.86, 53.45, 35.53, 30.73, 23.64, 15.12. ESI-MS (m/z): 557.53 [M+H]+.

4.1.2.13. (7R,13bR)-N-(4-(Hydroxycarbamoyl)phenyl)-14-methyl-5-oxo-5,7,8,13,13b,14-hexahydroindolo[2′,3′:3,4]pyrido[2,1-b]quinazoline-7-carboxamide (ent-32). Yellow solid (Yield: 40%)

1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ 11.45 (s, 1H), 10.50 (s, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 7.63 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 8.96 Hz, 2H), 7.59 (t, J = 7.96 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.96 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 7.96 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 7.96 Hz, 2H), 7.20 (d, J = 7.96 Hz, 1H), 7.11–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.01 (t, J = 7.96 Hz, 1H), 6.25 (s, 1H), 5.60 (d, J = 6.36 Hz, 1H), 3.37–3.40 (m, 2H), 2.56 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6, TMS): δ 170.50, 164.57, 150.77, 136.90, 133.46, 128.99, 128.31, 128.01, 127.73, 127.63, 127.48, 127.24, 126.59, 126.21, 125.53, 122.47, 122.08, 121.67, 120.99, 118.92, 118.38, 118.30, 111.61, 107.90, 68.06, 64.87, 53.41, 35.52, 23.64, 15.12. ESI-MS (m/z): 482.25 [M+H]+.

4.2. Biological studies

4.2.1. HDACs activity assay

All of the HDACs enzymatic reactions were conducted at 37 °C for 30 min. The 50 μL reaction mixture contains HDAC, 2.7 mmol/L KCl, 137 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 25 mmol/L Tris, pH 8.0, 0.1 mg/mL BSA and the enzyme substrate. The compounds were diluted in 10% DMSO and 5 μL of the dilution was added to a 50 μL reaction so that the final concentration of DMSO is 1% in all of reactions. The assay was performed by quantitating the fluorescent product amount of in solution following an enzyme reaction. Fluorescence is then analyzed with an excitation of 350–360 nmol/L and an emission wavelength of 450–460 nmol/L at SpectraMax M5 microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The IC50 values were calculated using nonlinear regression with normalized dose-response fit using Prism GraphPad software (San Diego, CA, USA). All experiments were independently performed at least three times.

4.2.2. TOP1 relaxation assay

The TOP1 inhibition assays were conducted as previously described32, 33, 34. Briefly, the reaction mixture containing 1 unit of TOP1 (TaKaRa Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China), supercoiled pBR322 plasmid DNA (0.25 μg) and the test compounds in a final volume of 20 μL was incubated for 15 min at 37 °C and stopped by the addition of 2 μL of 10× loading buffer (0.9% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 50% glycerol). The sample was separated by applying electrophoresis in a 0.8% agarose gel in TAE (Tris-acetate-EDTA) for 1 h. Ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/mL) was used to stain the resulting gels for 60 min, and the DNA band was transilluminated by UV light and photographed with a Gel Doc Ez imager (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Co., Hercules, CA, USA).

4.2.3. TOP2 relaxation assay

The TOP2 inhibition assay was carried out according to our previous study32, 33, 34. Briefly, the assay mixture included the test drugs (1% DMSO), 0.75 unit of TOP2α (TopoGEN, Inc., Buena Vista, CO, USA), pBR322 plasmid DNA (0.25), 10 mmol/L MgCl2, 30 μg/mL BSA, 5 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 2 mmol/L ATP, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) in a final volume of 20 μL. The resulting mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C and stopped by the addition of 2 μL of 10% SDS. Then, 2 μL of 10×gel loading buffer (0.25% bromophenol blue and 50% glycerol) was added. The sample was separated by applying electrophoresis in a 0.8% agarose gel in TAE (Tris-acetate-EDTA) for 1 h. Ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/mL) was used to stain the resulting gels for 60 min, and the DNA band was transilluminated by UV light and photographed with a Gel Doc Ez imager (Bio-Rad).

4.2.4. In vitro cell viability assay

Three human cancer cell lines, A549 (lung cancer), MCF-7 (breast cancer), HCT116 (colon cancer), were growth in 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated with DMEM at 60%–70% confluency for 24 h. Then, cells were treated with various concentrations of the test agents or vehicle for 48 h. The cell viability assay (CCK8 assay) was performed after drug treatment. 10% of CCK8 solution in culture medium in a final volume of 100 μL was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for additional 1–4 h. Absorbance at 450 nmol/L (optical density, OD) was detected on a micro plate reader (Biotek Synergy H2, Winooski, VT, USA). Drug concentrations inhibited 50% of cellular growth (IC50) were calculated by the Logit method. All experiments were performed three times.

4.2.5. Flow cytometry assay of cell apoptosis

HCT116 cells (35 × 104) were cultured in six-well plates overnight and exposed to different concentrations of compounds 1 (0.5, 1.0 and 5.0 μmol/L), 30a (0.5, 1.0 and 5.0 μmol/L), or vehicle for 48 h. After incubation, cells were harvested, washed twice with cold PBS, and stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The percentage of apoptotic cells was analyzed by flow cytometer (BD Accuri C6, San Jose, CA, USA).

4.2.6. Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle

HCT116 cells (35 × 104) were seeded and exposed to various concentrations of compounds 1 (0.5, 1.0 and 5.0 μmol/L), 30a (0.5, 1.0 and 5.0 μmol/L) or vehicle for 48 h. Then, cells were collected and stained with 25 μg/mL PI and 10 μg/mL RNase buffer. After the incubation period (30 min), the stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6).

4.2.7. Immunoblotting assay

HCT116 cells were seeded (35 × 104 cells/well) into 6-well plates (Corning, New York, NY, USA) and treated with compounds 1 or 30a at concentrations of 0.2 and 5 μmol/L or vehicle for 24 h. After the incubation period, cells were harvested and washed twice with cold PBS. And cells were lysed in RIPA Buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (EpiZyme, Shanghai, China) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (EpiZyme) at ice for 30 min. The protein concentrations were determined by using BCA Protein Assay. Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were separated onto an SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After blocking with 5% BSA for 2 h, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody (anti-Histone H3 (#ab1791, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-Histone H4 (#ab9051, Abcam)). Then the membranes were incubated with the secondary antibody for 1.5 h. The images were captured by Odyssey Infrared Imaging (Lincoln, NE, USA).

4.2.8. In vivo tumor growth inhibition assay against HCT116 xenograft

The experimental procedures and the animal use and care protocols were approved by the Committee on Ethical Use of Animals of The Second Military Medical University (Shanghai, China). BALB/c nude female mice (aging 5 to 6 weeks-old, weighing 18–20 g, Shanghai Experimental Animal Center, Certificate SCXK-2007-0005, China) were inoculated subcutaneously with 400 × 104 HCT116 colon cancer cells per mouse. About two weeks later (tumor volumes reaching to about 100–200 mm3), the mice were randomized into treatment and control groups (five animals per group). The treatment groups were administered by i.p. (or p.o.) with compounds 25a and 30a (indicated dosage), and the control received vehicle (saline with 0.1% Tween 80). Tumor volumes and body weights were monitored every three day. The longest diameter of a tumor (L) and the shortest width (S) were measured by a caliper. Tumor volumes were calculated using Eq. (1):

| (1) |

After the treatment, mice were sacrificed and the tumor tissue was dissected and weighted for analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 81872742 to Guoqiang Dong and 81725020 to Chunquan Sheng), the National Key R&D Program of China (grant 2017YFA0506000 to Chunquan Sheng), and the Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (Grant 2019-01-07-00-07-E00073 to Chunquan Sheng, China).

Author contributions

Chunquan Sheng, Guoqiang Dong and Yahui Huang designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Yahui Huang performed chemical synthesis and biological evaluations. Shuqiang Chen and Shanchao Wu assisted in the biological experiments.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2019.11.011.

Contributor Information

Guoqiang Dong, Email: dgq-81@163.com.

Chunquan Sheng, Email: shengcq@smmu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Haber D.A., Gray N.S., Baselga J. The evolving war on cancer. Cell. 2011;145:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trusolino L., Bertotti A. Compensatory pathways in oncogenic kinase signaling and resistance to targeted therapies: six degrees of separation. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:876–880. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dancey J.E., Chen H.X. Strategies for optimizing combinations of molecularly targeted anticancer agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:649–659. doi: 10.1038/nrd2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters J.U. Polypharmacology—foe or friend? J Med Chem. 2013;56:8955–8971. doi: 10.1021/jm400856t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anighoro A., Bajorath J., Rastelli G. Polypharmacology: challenges and opportunities in drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2014;57:7874–7887. doi: 10.1021/jm5006463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morphy R., Kay C., Rankovic Z. From magic bullets to designed multiple ligands. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9:641–651. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsay R.R., Popovic-Nikolic M.R., Nikolic K., Uliassi E., Bolognesi M.L. A perspective on multi-target drug discovery and design for complex diseases. Clin Transl Med. 2018;7:3. doi: 10.1186/s40169-017-0181-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baylin S.B., Jones P.A. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome‒biological and translational implications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:726–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones P.A., Baylin S.B. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Portela A., Esteller M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1057–1068. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly T.K., de Carvalho D.D., Jones P.A. Epigenetic modifications as therapeutic targets. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1069–1078. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo S.Y., Lam D.C. Oncogenic driver mutations in lung cancer. Transl Respir Med. 2013;1:6. doi: 10.1186/2213-0802-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mummaneni P., Shord S.S. Epigenetics and oncology. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:495–505. doi: 10.1002/phar.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ropero S., Esteller M. The role of histone deacetylases (HDACs) in human cancer. Mol Oncol. 2007;1:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West A.C., Johnstone R.W. New and emerging HDAC inhibitors for cancer treatment. J Clin Investig. 2014;124:30–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI69738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolden J.E., Peart M.J., Johnstone R.W. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:769–784. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nebbioso A., Clarke N., Voltz E., Germain E., Ambrosino C., Bontempo P. Tumor-selective action of HDAC inhibitors involves TRAIL induction in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Nat Med. 2005;11:77–84. doi: 10.1038/nm1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qian D.Z., Kato Y., Shabbeer S., Wei Y., Verheul H.M., Salumbides B. Targeting tumor angiogenesis with histone deacetylase inhibitors: the hydroxamic acid derivative LBH589. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:634–642. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geng L., Cuneo K.C., Fu A., Tu T., Atadja P.W., Hallahan D.E. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor LBH589 increases duration of gamma-H2AX foci and confines HDAC4 to the cytoplasm in irradiated non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11298–11304. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann B.S., Johnson J.R., Cohen M.H., Justice R., Pazdur R. FDA approval summary: vorinostat for treatment of advanced primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The Oncologist. 2007;12:1247–1252. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-10-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ververis K., Hiong A., Karagiannis T.C., Licciardi P.V. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs): multitargeted anticancer agents. Biologics. 2013;7:47–60. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S29965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailey H., Stenehjem D.D., Sharma S. Panobinostat for the treatment of multiple myeloma: the evidence to date. J Blood Med. 2015;6:269–276. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S69140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manal M., Chandrasekar M.J., Gomathi P.J., Nanjan M.J. Inhibitors of histone deacetylase as antitumor agents: a critical review. Bioorg Chem. 2016;67:18–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thurn K.T., Thomas S., Moore A., Munster P.N. Rational therapeutic combinations with histone deacetylase inhibitors for the treatment of cancer. Future Oncol. 2011;7:263–283. doi: 10.2217/fon.11.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perego P., Zuco V., Gatti L., Zunino F. Sensitization of tumor cells by targeting histone deacetylases. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:987–994. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hesham H.M., Lasheen D.S., Abouzid K.A.M. Chimeric HDAC inhibitors: comprehensive review on the HDAC-based strategies developed to combat cancer. Med Res Rev. 2018;38:2058–2109. doi: 10.1002/med.21505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganesan A. Multitarget drugs: an epigenetic epiphany. ChemMedChem. 2016;11:1227–1241. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201500394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson C.A., Padget K., Austin C.A., Turner B.M. Deacetylase activity associates with topoisomerase II and is necessary for etoposide-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4539–4542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchion D.C., Bicaku E., Daud A.I., Richon V., Sullivan D.M., Munster P.N. Sequence-specific potentiation of topoisomerase II inhibitors by the histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:223–237. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang J., Hu C. Evodiamine: a novel anti-cancer alkaloid from Evodia rutaecarpa. Molecules. 2009;14:1852–1859. doi: 10.3390/molecules14051852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu H., Jin H., Gong W., Wang Z., Liang H. Pharmacological actions of multi-target-directed evodiamine. Molecules. 2013;18:1826–1843. doi: 10.3390/molecules18021826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong G., Sheng C., Wang S., Miao Z., Yao J., Zhang W. Selection of evodiamine as a novel topoisomerase I inhibitor by structure-based virtual screening and hit optimization of evodiamine derivatives as antitumor agents. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7521–7531. doi: 10.1021/jm100387d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong G., Wang S., Miao Z., Yao J., Zhang Y., Guo Z. New tricks for an old natural product: discovery of highly potent evodiamine derivatives as novel antitumor agents by systemic structure–activity relationship analysis and biological evaluations. J Med Chem. 2012;55:7593–7613. doi: 10.1021/jm300605m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S., Fang K., Dong G., Chen S., Liu N., Miao Z. Scaffold diversity inspired by the natural product evodiamine: discovery of highly potent and multitargeting antitumor agents. J Med Chem. 2015;58:6678–6696. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen S., Dong G., Wu S., Liu N., Zhang W., Sheng C. Novel fluorescent probes of 10-hydroxyevodiamine: autophagy and apoptosis-inducing anticancer mechanisms. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He S., Dong G., Wang Z., Chen W., Huang Y., Li Z. Discovery of novel multiacting topoisomerase I/II and histone deacetylase Inhibitors. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2015;6:239–243. doi: 10.1021/ml500327q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Petrocellis L., Schiano Moriello A., Fontana G., Sacchetti A., Passarella D., Appendino G. Effect of chirality and lipophilicity in the functional activity of evodiamine and its analogues at TRPV1 channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:2608–2620. doi: 10.1111/bph.12320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christodoulou M.S., Sacchetti A., Ronchetti V., Caufin S., Silvani A., Lesma G. Quinazolinecarboline alkaloid evodiamine as scaffold for targeting topoisomerase I and sirtuins. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:6920–6928. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuo C.C. 2016 Jan 13. Wu KK, inventors. 5-Methoxytryptophan and its derivatives and uses thereof. WO2016115188A1. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bradner J.E., West N., Grachan M.L., Greenberg E.F., Haggarty S.J., Warnow T. Chemical phylogenetics of histone deacetylases. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:238–243. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogakou E.P., Pilch D.R., Orr A.H., Ivanova V.S., Bonner W.M. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5858–5868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Millard C.J., Watson P.J., Celardo I., Gordiyenko Y., Cowley S.M., Robinson C.V. Class I HDACs share a common mechanism of regulation by inositol phosphates. Mol Cell. 2013;51:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y.R., Chen S.F., Wu C.C., Liao Y.W., Lin T.S., Liu K.T. Producing irreversible topoisomerase II-mediated DNA breaks by site-specific Pt(II)-methionine coordination chemistry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:10920. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.