Abstract

Background

The declaration of COVID pandemic by the WHO can certainly be seen as a watershed era the world has witnessed in modern times. All non-essential industries and services have taken a back seat including aesthetic medicine. Over the last decade, India has witnessed a steady growth in medical tourism owing to global standards of care and services at a relatively modest cost. The following study was conducted to ascertain the sea change that this pandemic has brought into aesthetic surgeons’ practice, patient management, planning and consultation. This paper throws light on the journey of Indian aesthetic surgery from its infancy to its current presence in the global market as a context of the study. We have also discussed the impact of social media on aesthetic surgeons’ practice, lifestyle and its role as an emerging new method of medical education.

Methods

A questionnaire consisting of 62 questions divided in 3 sections was rolled out to 150 Indian aesthetic surgeons who have been practising either independently in their clinics or are associated with hospitals. A: Pre-COVID practice management and lifestyle; B: life during the lockdown; C: anticipated changes in post-COVID era.

Results

In the pre-COVID era, an average aesthetic surgeon was finely balancing his profession, personal lifestyle, learning, and recreation. The lockdown clamped their practices which lead into a financial drought; despite which, they were able to maintain their productivity by engaging in webinars, reading, and research. The post-COVID times demand an implementation of safety protocols along with changes in set-up, regulating patient traffic, engaging in distant learning through virtual conferences, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle acquired during the lockdown.

Conclusions

India was rightly witnessing a surge in popularity of aesthetic surgery and medical tourism over the last decade. The corona pandemic has definitely hit this escalating growth curve hard, and it will take some time for the demand to recover. Our study revealed the following conclusions: The effect of COVID 19 demands a major change in aesthetic surgeons’ professional practice like limiting consultations, changing hospital floor plan, following COVID testing, and having new safety protocols. Social media is rightly poised to be a major tool for education and marketing as also for recreation and leisure. The role of teleconsultation needs to be reprised and legalised. Webinars and virtual conferences will find more takers in future.

Level of evidence: not ratable.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00238-020-01730-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pandemic, Evolution of aesthetic surgery, India, COVID

Introduction

The human race has survived many calamities, but this situation of a global pandemic is unprecedented to the current generation. Ever since the World Health Organization declared the COVID as a pandemic, the majority of countries around the world underwent a lockdown of varying duration with suspension of non-essential activities and businesses. The novel coronavirus responsible for COVID 19 was first identified in Wuhan in December 2019 [1, 2]. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic [3]. As of today, 17.5 million cases have been diagnosed and 677,185 deaths have occurred, and the numbers do not seem to be abating any time soon. The health industry witnessed cancellations of routine appointments and procedures and suspension of surgeries which were not lifesaving or emergent. The aesthetic surgeons who were otherwise leading a busy and active lifestyle were rendered absolutely workless in this situation.

India saw the advent of plastic surgery as early as 600 BC with the works of Sushrut which he compiled in his manuscript titled Sushrut Samhita. Modern plastic surgery was born as a specialty after World War I and II due to the need to treat the traumatised and disfigured survivors of these wars. Plastic surgery in modern India owes a great deal to Sir Harold Gillies, Eric Peet, and BK Rank for developing this speciality [4–11].

Aesthetic surgery as a distinct entity in India began as late as the 1990s, and there has since been a steady progression in the number of aesthetic procedures performed. ISAPS 2018 database stated that India stood at number 5 in the number of aesthetic procedures conducted around the world, and it was only in the year 2014 that India did not have any mention in the top 8. A total of 895,896 surgical and non-surgical procedures were performed. Also, India witnessed 54,234 rhinoplasties being performed, second only to Brazil. ISAPS states that 12.5% of the aesthetic procedures in India were performed on overseas patients. As per the data from our study, every one in three surgeons operate on overseas patients. India has seen the emergence of medical tourism in the last decade due to certain other factors as well. The combination of modest pricings, state of the art centres, and highly skilled surgeons invite a lot of patients from other countries thus making a significant contribution to forex reserve. The bulk of such visitors come from neighbouring countries of Bangladesh, Afghanistan and the Middle East. In 2015, India ranked as the third most popular destination for medical tourism, when the industry was worth $3 billion. The number of foreign tourists coming into the country on medical visas sat at nearly 234,000 which had grown to 495,056 by 2017 [12]. The medical tourism industry was expected to grow at an astronomical 200% touching a corpus of $9 billion by 2020 according to the Ministry of Tourism data [13]. Hair transplant is estimated to be a 700 crore rupees (almost 100 million dollars) business in India already [14]. The Indian Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (IAAPS) was founded in 1995, and since then, it has been playing a pivotal role in creating opportunities, streamlining residency format, conducting fellowships, creating awareness, and encouraging research for aesthetic surgeons in India. Presently, India has north of 2000 practising plastic surgeons of which 1000 have been added in the last 6–7 years itself. While most practise a combination of reconstructive and aesthetic surgery, there is an increasing number of young surgeons who occupy themselves exclusively with aesthetic surgery and have their own centres. In a study conducted by Puri et al. [15], aesthetic surgery is the most sought after speciality for plastic surgery trainees.

In the pre-pandemic world, India was being seen as an emerging market for medical tourism in aesthetic surgery, with an increasing number of procedures being conducted every year. We have designed a questionnaire to estimate the sea change that it has brought into aesthetic surgeons’ practice, patient management, planning and consultation. This paper also throws light on the impact of social media on aesthetic surgeons’ practice, lifestyle and as emerging new methods of medical education.

Materials and methods

A questionnaire consisting of 62 questions was rolled out to 150 Indian aesthetic surgeons who have been practising either independently in their clinics or are associated with hospitals. The surgeons were picked on a random basis from all parts of the country based on the fact that the bulk of their work was aesthetic. We had a total of 108 respondents for this study. Although the respondents provided us with their names and address for correspondence, this information has been kept confidential and was used only to rule out any unwanted entries.

This questionnaire which has been attached as a part of annexures (No. 1) had 3 sections consisting of:

-

(A)

Pre-COVID practice management and lifestyle

-

(B)

Life during COVID lockdown and pandemic

-

(C)

Anticipated changes in post-COVID era

Most of the items in the questionnaire had two options, while a small number had three options too. The option with maximum response was plotted on the graph, and in some questions, responses from two options were combined and plotted as a single bar.

Aims

The aim of this study is to estimate the sea change brought into an Indian aesthetic surgeons’ practice management and lifestyle by the COVID pandemic.

Objectives

To study the progression of aesthetic surgery in India as well as practice management and lifestyle of an Indian aesthetic surgeon in the pre-COVID era.

To assess the modifications ensued in practice and lifestyle due to COVID lockdown and pandemic and predicting the longevity of such changes and relevance in future.

To establish the role of social media as a tool for marketing, education and leisure in the COVID and post-COVID era.

Results

Demography

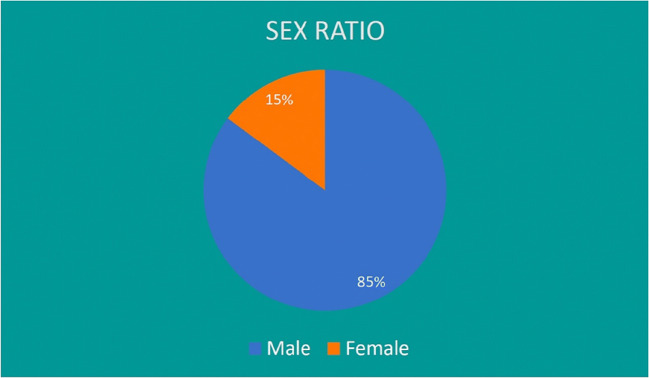

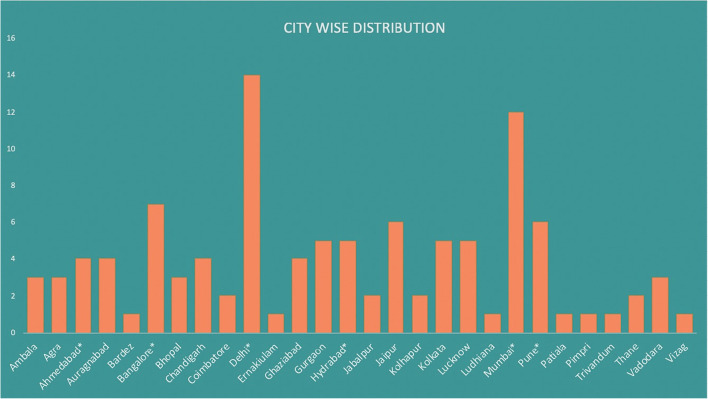

Eighty-five percent of the surgeons were males, while women comprised 15% of the cohort (Fig. 1). Our study included surgeons from all around the nation including 48 from metro cities (Fig. 2). Eighty percent of the surgeons were young surgeons with less than 15 years of practice.

Fig. 1.

Sex ratio of the respondents

Fig. 2.

City-wise distribution

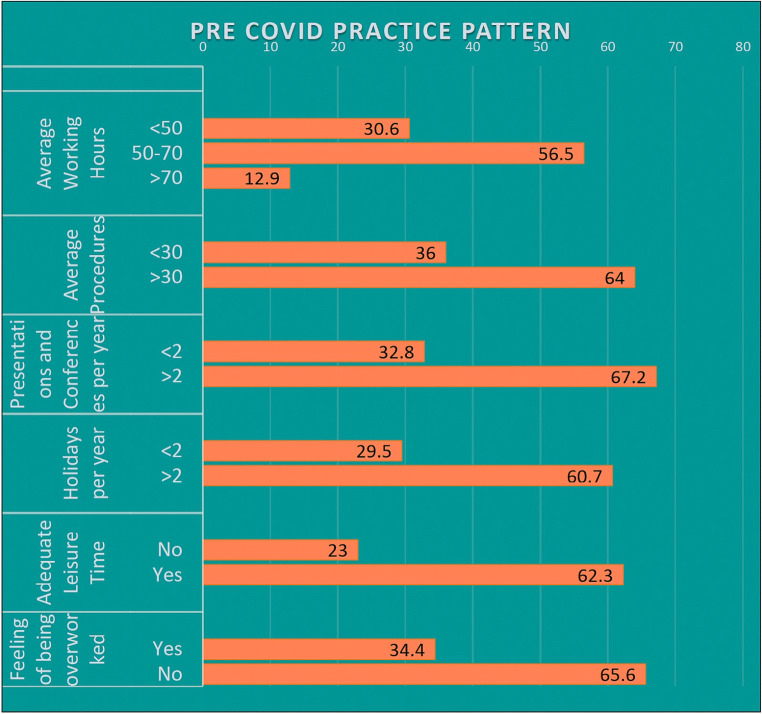

Pre-COVID practice management and lifestyle

In the first set of questions, we have determined the practice management and lifestyle of an Indian aesthetic surgeon (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pre-COVID practice pattern

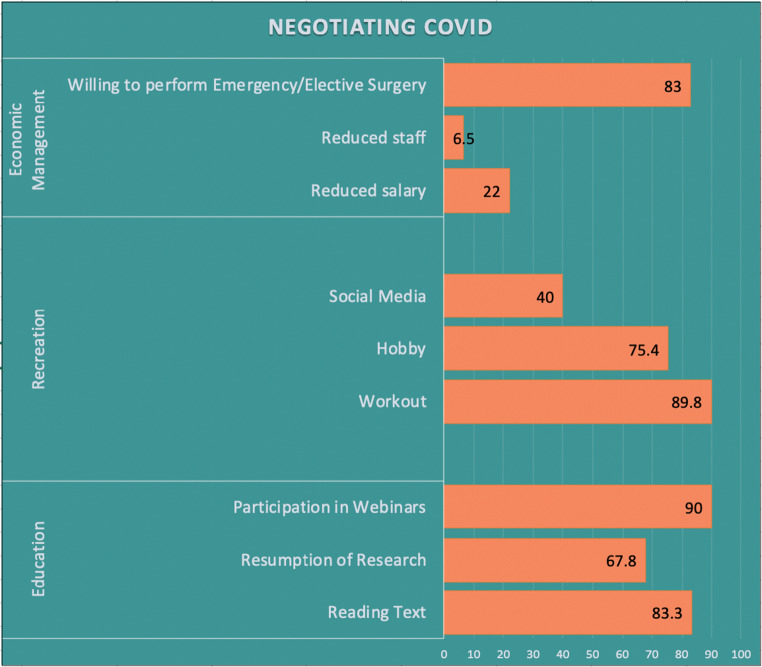

Life during COVID pandemic

The second set of questions was designed to understand the changes that a surgeon has gone through during the lockdown phase of the COVID pandemic (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Negotiating COVID

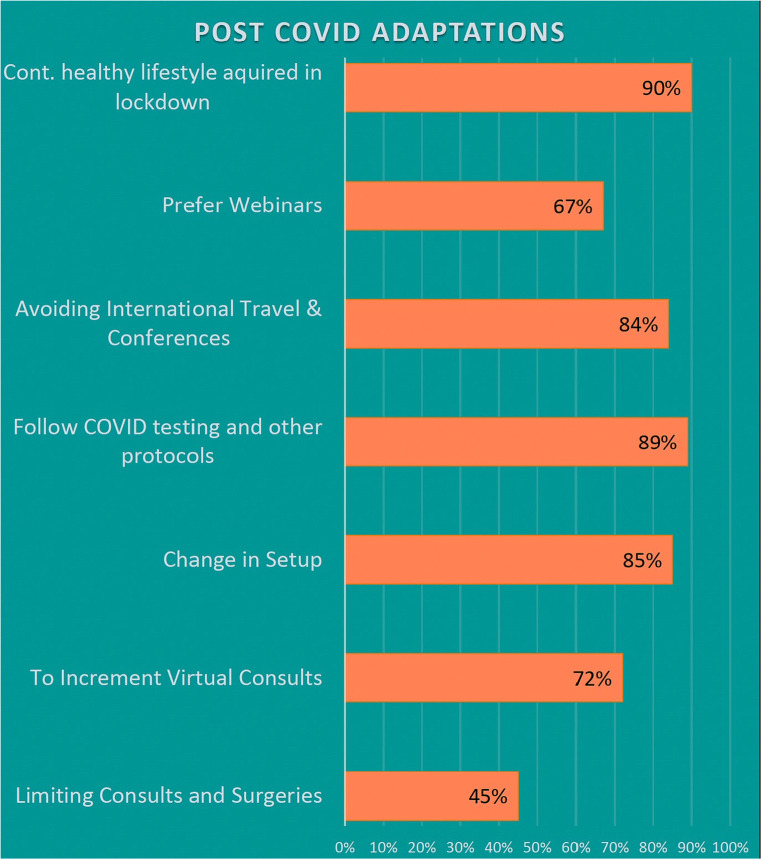

Anticipated changes in post-COVID era

From the last part of the questionnaire, we have tried to understand what changes are expected in a surgeons’ practice and lifestyle and which one of these will become standard norms in the near future (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Post-COVID adaptations

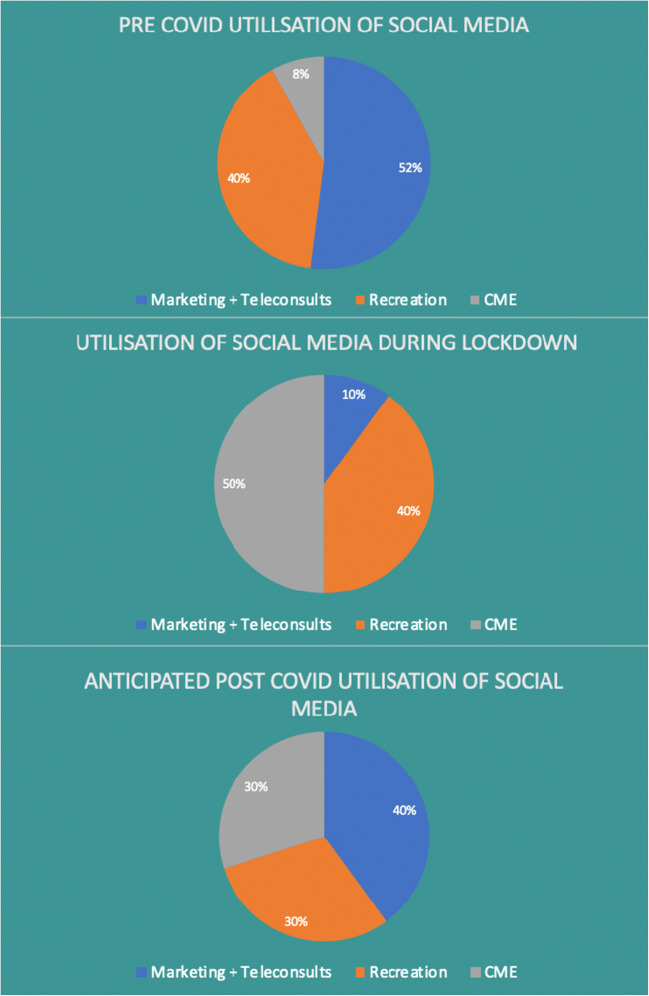

Changing social media trends

The role of social media has escalated during the pandemic, and this is expected to continue in the future. Social media is expected to play a major role in continuing medical education (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Changing social media trends

Discussion

Pre-COVID practice of aesthetic surgeons in India

A surgeon’s practice is usually considered a busy one in India where there is no cap to the working hours. NHS recommends maximum average working hours of 48 per week with doctors who opt out of the WTR (working time regulations) capped at a maximum average of 56 working hours per week. In our study, the majority of the surgeons had 50–70 working hours in a week and 13% had more than 70. The average number of daily consultations was 11–15 for most, and surgeries performed in a month were in the range 20–35. On an average, approximately 60% of the surgeons had a waiting period of less than a week. Approximately two-thirds of our surgeons attended two or more conferences each year and more than half were involved in research work and regularly presented in conferences. The number of aesthetic surgery conferences held has seen an upward trend in the last few years. There were as many as 6–7 IAAPS endorsed conferences with national and international speakers and many more workshops organised by regional associations.

Barely 35% complained about having less family time and felt overworked. Overall, 85% aesthetic surgeons from our survey labelled their work life balance as good.

To conclude, Indian aesthetic surgeon was leading a professionally busy and satisfied life, and more than 60% were able to make time for family, education and leisure as well. He was economically settled and was poised to grow commensurate with his western counterparts given the flourishing market of medical tourism in India. The COVID halted the meteoric progress of what could have been the most affordable, accessible and state of the art aesthetic surgery industry in the world.

During COVID times; the lockdown

With the realisation of the pandemic, a majority of the nations went into lockdown in various intensities bringing all non-essential activities and services to a grinding halt. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the global economy is expected to shrink by over 3% in 2020—the steepest slowdown since the Great Depression of the 1930s. In the USA, the number of people filing for unemployment has hit a record high. Expectedly, the Indian aesthetic surgeons’ practice during the lockdown was virtually nil, and almost 95% future bookings involving local and overseas patients were cancelled. For most surgeons, the cash inflow in the second quarter of 2020 was negligible and yet 78% claim to be paying their staff full salary. A very small proportion (6.5%) of our participants however agreed to have laid off the excess staff. Hence, it has been a challenging phase of worklessness, economic issues, anxiety, and uncertainty for the fraternity as a whole. And it did not come as a surprise that 83% of our cohort were willing to perform emergency procedures given the chance.

True to the indomitable human spirit, we observed a significant increase in recreational activities such as workout and hobbies during the lockdown. Three out of four felt more rested and refreshed during this phase. A total of 67% started or resumed their research activity and two-thirds utilised this time to read more books in their field of interest. Lockdown gave the surgeons an opportunity to do things for leisure which they have revelled in so much that now they (90%) resolve to make amends in their lifestyle to make time for all such new acquired passions like yoga, meditation and workout.

The lockdown saw an increase in the internet hours by majority of our respondents. They were spending an average of 2–3 h online in various ways. COVID has had a negative impact on almost everything, but it has given surgeons some time to reflect, breathe and realise the importance of a balanced life and has inspired them to work positively towards it in the future as well.

COVID 19: the impact

Routine aesthetic surgeries and procedures which are non-essential and non-life saving have understandably taken a back seat in this conundrum. In response, the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health have published information about COVID-19 and recommendations on how to protect medical personnel and curb the spread of the disease [16–19].

The current scenario demands a change across all levels including working protocol, operating guidelines, staff administration and also in the office set-up and as many as 85% of our participants intend to carry out changes in the office setting as per norms. It is in the authors opinion that the changes in the set-up would expectedly include spacing the consults by time and distance, expanding waiting area, regulating and redirecting the traffic of staff and patients to maintain one way, creating dedicated donning and doffing areas, earmarking well-ventilated room for minor procedures, and changing the OT to make it corona-proof by installing filters. These may entail major renovation work for some, while for others, it may warrant moving on to a new office location altogether. Despite the majority agreeing to set up changes, only 45% thought that reduction in the number of consultations and procedures was needed.

As per the guidelines set up by ICMR and other similar agencies, the patient’s COVID-19 status should be determined prior to surgery [20, 21] through RT PCR which is the preferred laboratory test to date [22, 23], with diagnostic accuracy in the range of 56–83%. Patients who are positive should be operated only for life saving surgeries in designated negative pressure airflow operating rooms with a team dedicated to their care [24–26]. Since the viral pathogen survives on environmental surfaces for extended periods of time, usual cleaning practices may be inadequate and need adjustment [27–29].

One of the most commonly debated topics in the setting of COVID-19 is the choice of personal protective equipment (PPE) for COVID-negative elective surgical patients which will be the situation faced by aesthetic surgeons in their practices. Despite conflicting practices worldwide, the authors suggest use of respirator masks that efficiently filtrate airborne particles (i.e. N95 respirator), loupes with face shields and isolation gowns and PPE for all head and neck surgeries [30, 31]. Most institutions have developed individual protocols adapted from guidelines of the World Health Organization [32]. A total of 89% of our respondents seem mentally prepared to embrace all the given protocols for their and their patient’s safety and seem eager to join work as early as June.

Financial implications of bringing about all these changes are in no way miniscule and have a bearing on all aesthetic surgeons especially the ones who are in the initial phases of getting established. Ninety-percent anticipate reduction in their practice volume in the coming times with a reduction in yearly income to the tune of 40% for a few more years. Probably, that is the reason the Indian aesthetic surgeon is not very keen on buying the new energy-based devices (non-invasive fat reduction and skin tightening), an option which is very sought out and routinely offered by western aesthetic clinics and which should presumably be more in demand in post-COVID era than surgery.

COVID has changed every aspect of a surgeon’s practice and most of it irreversibly. It is a long road to recovery, but we are already on it with the lifting of lockdown and resumption of all activities. The growth curve has nevertheless been hit hard.

A similar such study was conducted by Fuertes et al. and published in EJPS in May 2020 wherein they assessed the impact of COVID 19 on the working capacity and protocols of plastic surgery departments across Spain at the height of the pandemic similar to the state which India is going through, currently standing third in the world as far as the number of cases is concerned. These departments were involved in burn care, oncological reconstructions and trauma among other routine plastic surgery procedures. Many common parameters were assessed, and similar conclusions were reached like the 0–40% decrease in volume of consults and surgeries, drastic reduction in number of non-emergency procedures, adoption of virus protective protocols and encouraging teleconsults. Since our study was focussed entirely on individual aesthetic set-ups, the changes in volume were more pronounced. They also enquired about the specific COVID training imparted to the staff and doctors which we feel is worthy of its mention in this article [33]. We enquired about other aspects of an individual’s practice and lifestyle affected by this pandemic.

Escalating the role of social media in a surgeons’ practice and learning

Social media is now recognised to be an important part of an aesthetic surgeons’ practice. Telemedicine services are being offered for many non-urgent appointments, routine surveillance encounters and follow-ups. In the USA, these visits are considered the same as in-person visits and are paid at the same rate as regular, as per CMS guidelines [34–36]. In our study, 72% surgeons say that less than 10% of their consultations or follow-ups were virtual in the pre-pandemic era and they rarely got appointments or queries via these platforms. This is likely to change in the coming times as many surgeons are willing to encourage virtual consultations thus avoiding interhuman contacts and, therefore, contagion [37, 38]. However, with virtual consultations, there is an inadequacy of a comprehensive examination as well as certain medico legal concerns.

In the pre-COVID era, nearly half of the social media hours were dedicated to marketing followed by recreation and minimal time was for continuing medical education (CME). As much as 80% of marketing was being done on social media mostly through a professional agency. Fifty-one percent of our cohort has a dedicated Instagram/YouTube handle and more than 40% posted pictures and videos on a weekly basis. Suffice it to say that while the surgeons in the rest of the world use social media regularly to display their results and attract more clients, the Indian fraternity was not far behind. During the lockdown, marketing became virtually irrelevant and our respondents predictably spent more than their pre-COVID average time on the internet, the bulk(90%) of which was for recreation and education. While in the past, 90% rarely took part in webinars, now 78% are actively participating in them. With 84% of them not wishing to visit any virus-affected nation in the year 2020, webinars will remain the predominant source of learning and education in future as well. However, a couple of surgeons in our comments section have expressed copyright and privacy concerns because contents can easily be recorded and photographed. Webinars need to be more structured, and the various societies should be willing to provide the necessary credit points like a few recent ongoing online courses have. Looking at the trend, we predict that online CMEs will continue to consume a good chunk of online time, and marketing share will also increase eventually as economies open and recover. Recreation time will more or less remain the same.

Conclusion

India was rightly witnessing a surge in popularity of aesthetic surgery and medical tourism over the last decade. The corona pandemic has definitely hit this escalating growth curve hard, and it will take some time for the demand to recover. With reduced number of consultations and procedures, along with cancellations both from the country and overseas, the surgeons are feeling anxious and depressed and are resorting to changes to combat the turmoil. Our study revealed the following conclusions:

The effect of COVID-19 demands a major change in aesthetic surgeons’ professional practice like limiting consultations, changing office set-up, following COVID testing, and creating new safety protocols.

Social media is rightly poised to be a major tool for education and marketing as also for recreation and leisure.

The role of teleconsultations needs to be reprised and legalised.

Webinars and virtual conferences will find more takers future.

To conclude, I would wish to quote a few words from our father of the nation, MK Gandhi, “The future depends on what we do in the present.”

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 98 kb).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Sangeeta Thakurani and Samarth Gupta declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Consent to participate

Participants in the survey consented for publication of the results.

Consent for publication

Upon submission, all authors consent to the publication of the manuscript in the European Journal of Plastic Surgery.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, Wang W, Song H, Huang B, Zhu N, Bi Y, Ma X, Zhan F, Wang L, Hu T, Zhou H, Hu Z, Zhou W, Zhao L, Chen J, Meng Y, Wang J, Lin Y, Yuan J, Xie Z, Ma J, Liu WJ, Wang D, Xu W, Holmes EC, Gao GF, Wu G, Chen W, Shi W, Tan W. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-directorgeneral-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-COVID-19%2D%2D-11-march-2020. Accessed March 22, 2020

- 4.Davis L Organization of the Red Army Medical Corps. Surg Gynecol Obstet,79, No. 3,329, September, I94

- 5.Esser JFS. Plastic surgery of the face. Ann Surg. 1917;65:297. doi: 10.1097/00000658-191703000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filatov VP PlastieaTigeRonde. VestnikoftalNo.4and5,AprilandMay,I917

- 7.Gilies HD (1920) The tubed pedicle in plastic surgery. New York Medical Journal 3,x

- 8.Moore JE. UnitedStatesArmyMedicalCorps. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1945;8o:3,333. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McIntire RT. Health conditions in the navy. JAMA. 1945;129:3,215. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rankin FW The mission of surgical specialists in the U.S. Army. Surg Gynecol Obstet, 8o, No. 4, 44I, April, i945

- 11.Smith F (1942) Plastic and maxillofacial surgery. Military surgical manual. W. B.Saunders Co., Philadelphia

- 12.CNN Health (2019) CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2019/02/13/health/india-medical-tourism-industry-intl/index.html. Accessed on 1 May, 2020

- 13.CNN Health (2019) Health, CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2019/02/13/health/india-medical-tourism-industry-intl/index.html. Accessed on 1 May, 2020

- 14.Indian Express (2019) A hairs’s breath away. https://indianexpress.com/article/india/a-hairs-breadth-away-6167410/. Accessed on 1 May, 2020

- 15.Khare N, Puri V. Education in plastic surgery: are we headed in the right direction? Indian J Plast Surg. 2014;47(1):109–115. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.129636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus (COVID-19). Available at cdc.govcoronavirus/2019-nCoV/index.html. Accessed March 16, 2020

- 17.National Institutes of Health Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Available at nih.gov/health-information/coronavirus.Accessed March 16, 2020 [PubMed]

- 18.Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD. How willcountry-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395:931–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Givi B, Schiff BA, Chinn SB, Clayburgh D, Iyer NG, Jalisi S, Moore MG, Nathan CA, Orloff LA, O’Neill JP, Parker N, Zender C, Morris LGT, Davies L. Safety recommendations for evaluation and surgery of the head and neck during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146:579. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American College of Surgeons COVID-19: elective case triage guidelines for surgical care. https://www.facs.org/COVID-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case. Accessed April 24, 2020

- 21.Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons SAGES and EAES recommendations regarding surgical response to COVID-19 crisis. https://www.sages.org/recommendations-surgical-response-COVID-19/. Accessed April 24, 2020

- 22.Vashist SK (2020) In vitro diagnostic assays for COVID-19: recent advances and emerging trends. Diagnostics (Basel) 10(4). 10.3390/diagnostics10040202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Lu R, Wang J, Li M, Wang Y, Dong J, Cai W (2020) SARS-CoV-2 detection using digital PCR for COVID-19 diagnosis, treatment monitoring and criteria for discharge. medRxiv

- 24.Tien HC, Chughtai T, Jogeklar A, Cooper AB, Brenneman F (2005) Elective and emergency surgery in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Can J Surg 48(1):71–74 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Dexter F, Parra MC, Brown JR, Loftus RW. Perioperative COVID-19 defense: an evidence-based approach for optimization of infection control and operating room management. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:37–42. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html. Accessed April 24, 2020

- 27.Moore G, Ali S, Cloutman-Green EA, Bradley CR, Wilkinson MAC, Hartley JC, Fraise AP, Wilson APR (2012) Use of UV-C radiation to disinfect non-critical patient care items: a laboratory assessment of the nanoclave cabinet. BMC Infect Dis 12. 10.1186/1471-2334-12-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Loftus RW, Koff MD, Burchman CC, Schwartzman JD, Thorum V, Read ME, Wood TA, Beach ML. Transmission of pathogenic bacterial organisms in the anesthesia work area. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:399–407. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318182c855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loftus RW, Brown JR, Koff MD, Reddy S, Heard SO, Patel HM, Fernandez PG, Beach ML, Corwin HL, Jensen JT, Kispert D, Huysman B, Dodds TM, Ruoff KL, Yeager MP. Multiple reservoirs contribute to intraoperative bacterial transmission. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:1236–1248. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824970a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anesth. 2020;67:568–576. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01591-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for the selection and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/ppe/PPEslides6-29-04.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2020

- 32.World Health Organization. Rational use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331498/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPCPPE_use-2020.2-eng.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2020

- 33.Fuerets et al (2020) Current impact of Covid-19 pandemic on Spanish plastic surgery departments: a multi-center report. Eur J Plast Surg. 10.1007/s00238-020-01686-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Accessed April 24, 2020

- 35.Wagner F, Knipfer C, Holzinger D, Ploder O, Nkenke E. Webinars for continuing education in oral and maxillofacial surgery: the Austrian experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2019;47(4):537–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luze H, Nischwitz SP, Kotzbeck P, Kamolz LP (2020) Can we use Google trends to estimate the demand for plastic surgery? Eur J Plast Surg. 10.1007/s00238-020-01647-7

- 37.Funderburk CD, Batulis NS, Zelones JT, Fisher AH, Prock KL, Markov NP, Evans AE, Nigriny JF. Innovations in the plastic surgery care pathway: using telemedicine for clinical efficiency and patient satisfaction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(2):507–516. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayer HF, Persichetti P. Plastic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic times. Eur J Plast Surg. 2020;43:361–362. doi: 10.1007/s00238-020-01685-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 98 kb).