Abstract

During the last few decades, the global incidence of dengue virus (DENV) has increased dramatically, and it is now endemic in more than 100 countries. To establish a productive infection in humans, DENV uses different strategies to inhibit or avoid the host innate immune system. Several DENV proteins have been shown to strategically target crucial components of the type I interferon system. Here, we report that the DENV NS2B protease cofactor targets the DNA sensor cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) for lysosomal degradation to avoid the detection of mitochondrial DNA during infection. Such degradation subsequently results in the inhibition of type I interferon production in the infected cell. Our data demonstrate a mechanism by which cGAS senses cellular damage upon DENV infection.

Numerous reports show that pathogenic human viruses have acquired specific molecular mechanisms to strategically avoid detection by the innate immune system. Some of these strategies are passive, consisting of hiding viral products with pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from the intracellular sensors known as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs)1,2. Active strategies, instead, are used by viruses to target crucial sensing components, minimizing the ability of cells to detect and respond to the infection3. This allows sufficient time for the production of viral progeny, before the antiviral state can be established in infected cells and before adaptive immune responses are generated.

Dengue virus (DENV) is the most prevalent mosquito-transmitted human virus, with an estimated infection rate of almost 400 million people per year4, and thus representing a global health threat. DENV has been reported to use a hiding strategy to avoid PRR recognition by replicating its viral RNA inside semi-isolated membrane vesicle packets5. These vesicles are virus-induced intracellular membrane rearrangements, which serve as the scaffold necessary for viral RNA replication and as a physical barrier to prevent viral PAMPs encountering cytosolic sensors1.

Functional studies of individual DENV proteins have elucidated the mechanisms by which the virus interferes or degrades crucial components of the host innate immune system. Some reports describe how non-structural viral proteins (NS2A, NS4A, NS4B and NS5) target signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins (STATs) 1 and 2, and interfere with their function or induce their degradation6,7. Given that STATs are required for type I interferon (IFN) signalling, these phenomena minimize the expression of hundreds of antiviral genes induced by type I IFNs (ISGs)8.

In addition to hiding viral PAMPs, DENV actively inhibits host sensing pathways that lead to IFN induction. In this Article, we show that cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) is degraded during DENV infection. cGAS is a cytosolic DNA sensor that, upon binding to DNA, synthesizes the second messenger cGAMP, which activates the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resident host protein STING, leading to type I IFN production9. We describe that the DENV-encoded protease cofactor NS2B promotes cGAS degradation in an autophagy–lysosome-dependent mechanism. We also show that DENV infection induces cGAS degradation to prevent its activation by mitochondrial DNA released during DENV infection, establishing the recognition of cellular mitochondrial damage as a mechanism by which cells detect virus infection. We propose that cGAS degradation cooperates with the DENV NS2B3 protease-mediated cleavage of STING, as previously shown by us and others10,11, to prevent the activation of the cGAS/cGAMP/STING sensing pathway of the induction of type I IFN during DENV infection, minimizing the host innate antiviral response and promoting viral replication and disease.

Results

Dengue virus infection results in loss of cGAS.

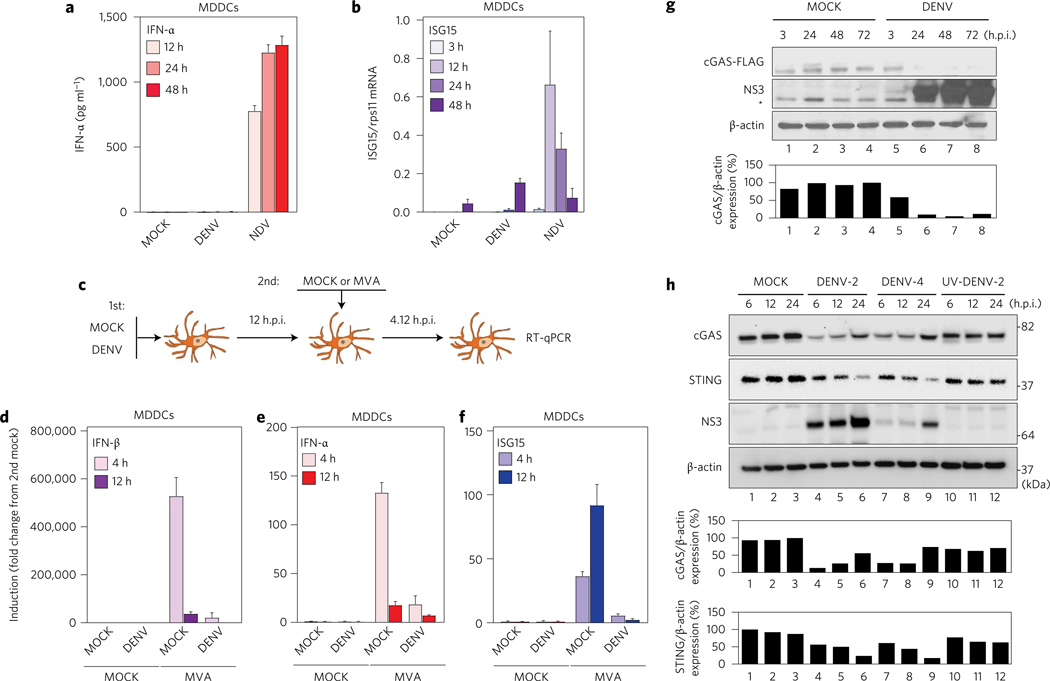

Previous studies by our group and others have demonstrated that DENV uses different mechanisms of immune evasion7,10,12–14. Using an ex vivo system to evaluate the ability of primary human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MDDCs) to sense infection by DENV, we compared the competence of these immune cells to produce type I IFNs and ISGs upon infection with DENV-2 (16681), or Newcastle disease virus (NDV-La Sota) used as control15, at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5. MDDCs showed high levels of IFN-α production after infection with NDV, but no significant induction was detected after DENV infection (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). Also, and consistent with our previous results, a weak induction of ISG15 mRNA was observed when cells were infected with DENV-2 (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1 |. cGAS is degraded during DENV infection.

Human MDDCs were infected with MOCK, DENV or NDV at MOI = 0.5, and samples of cells and supernatants were collected at 3, 12, 24 and 48 h.p.i. a, Quantification of IFN-α protein in cell supernatants by ELISA. b, Quantification of ISG15 mRNA by RT-qPCR (relative to rps11 mRNA). Results are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological replicates. c, Scheme for co-infection experiment. d, IFN-β mRNA quantification by RT–qPCR (relative to rps11). e, As in d, for IFN-α mRNA. f, As in d, for ISG15 mRNA. Results are representative of two independent experiments and are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological replicates. g, Western blot analysis of human cGAS during MOCK or DENV-2 infection (MOI = 5) conditions. cGAS-FLAG tagged was detected using anti-FLAG antibody. DENV infection was detected using a polyclonal rabbit serum raised against the helicase domain of DENV-2 NS3 protein. *Unspecific band. Antibody anti-β-actin was used to measure total loaded protein in western blot. h, Protein analysis by western blot of primary MDDCs treated with MOCK, DENV-2 (MOI = 10), DENV-4 (MOI = 10) or same number of UV-DENV-2 particles. Detection of endogenous human cGAS, human STING and DENV NS3 protein (anti-NS3 serum was raised against DENV-2 NS3 but can also detect DENV-4 NS3, although less efficiently). Antibody anti-β-actin was used to measure total loaded protein in western blot. Densitometry analysis of cGAS and/or STING relative to β-actin is expressed as a percentage using ImageJ software for g and h, and plotted as bar graphs.

To further evaluate the ability of DENV to counteract the STING-dependent DNA sensing pathway, we performed DENV and modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) virus co-infection experiments in human primary cells10,12 (Fig. 1c; see Methods). MVA is a DNA virus known to trigger type I IFN production through the cGAS/cGAMP/STING pathway16. In this experimental context, MDDCs first treated with infectious DENV showed a reduction in their ability to induce IFN-β, IFN-α and ISG15 mRNA after MVA infection as compared to MOCK (Fig. 1d–f ). Infection by MVA was confirmed by its expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a reporter gene in the infected MDDCs (Supplementary Fig. 1c). These results confirm that DENV can antagonize the cGAS/cGAMP/STING pathway triggered by a DNA virus.

STING is an adaptor molecule that has been shown to cooperate with mitochondrial antiviral-signalling protein during cytoplasmic viral RNA sensing for induction of IFN after viral infection17. However, STING is best known by its ability to be activated by cGAMP, a second messenger synthesized by cGAS, leading to IFN induction during infections with DNA viruses and retroviruses9,18. Because STING is cleaved during DENV infection10,11, we investigated the direct impact of DENV infection on cGAS. We generated cGAS-FLAG expressing 293T cells and assessed cGAS status by western blot after infection with DENV-2 (16681) (MOI = 5).

A pronounced reduction in cGAS levels was observed, concomitant with the appearance of DENV non-structural protein 3 (NS3) (Fig. 1g). To validate this observation, human MDDCs were infected MOCK, with DENV-2 (16681), DENV-4 (1036, Indonesia 1976) or the same number of ultraviolet-inactivated DENV-2 particles. In this context, we also observed an early reduction of cGAS protein for DENV-2 and DENV-4 as compared with MOCK and ultraviolet-inactivated DENV-2 treated cells. These results suggest a DENV replication-dependent cGAS degradation (Fig. 1h). We also observed STING degradation concomitant with the accumulation of NS3 protein (shown to monitor DENV infection) and consistent with a previous report from our group10 (Fig. 1h).

DENV protease complex counteracts the cGAS/STING pathway.

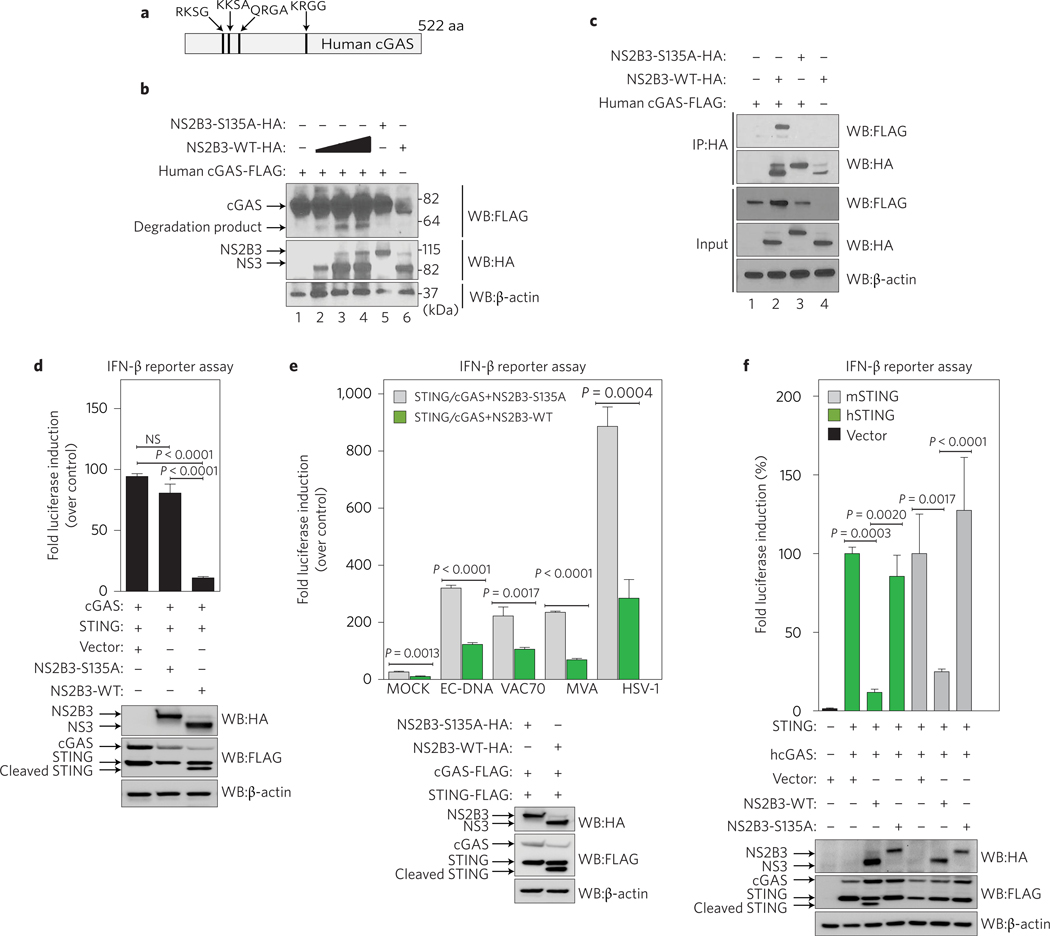

To evaluate the mechanism of cGAS degradation during DENV infection, we tested to see whether cGAS, similarly to STING10, was targeted for cleavage by the DENV NS2B3 protease complex. We therefore performed an in silico analysis of the cGAS amino-acid sequence and identified four potential NS2B3 target signatures (Fig. 2a). This prompted us to evaluate the ability of NS2B3 to interact with and cleave cGAS. After co-expression of human cGAS with DENV NS2B3, we observed the appearance of a modest amount of cGAS degradation product in an NS2B3 dose-dependent manner. Such a cGAS degradation product was absent when a catalytically inactive mutant NS2B3–S135A was expressed, suggesting that the cGAS degradation was dependent on NS2B3 proteolytic activity (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, cGAS co-immunoprecipitated with DENV NS2B3 wild type (WT) but not with the NS2B3–S135A mutant (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2 |. DENV protease complex counteracts the cGAS/STING pathway.

a, Graphic representation of human cGAS protein with the predicted DENV NS2B3 potential cleavage sites indicated. b, Co-expression of human cGAS and different amounts of DENV NS2B3 WT (0.2, 1 and 2 μg) or NS2B3–S135A (1 μg) analysed by western blot using anti-HA, anti-FLAG and anti-β-actin antibodies. c, Co-immunoprecipitation of cGAS by DENV NS2B3 WT or NS2B3–S135A and analysis by western blot using the same antibodies as in b. d, Evaluation of DENV NS2B3 protease complex as an antagonist of the cGAS/STING pathway by IFN-β reporter assay. 293T–IFN-β–FFLuc cells were transfected with plasmids encoding human STING, cGAS and either empty vector, DENV NS2B3 WT or proteolytically inactive mutant NS2B3–S135A. Results are representative of two independent experiments and are expressed as mean ± s.e. m. from three biological replicates (one-way ANOVA). e, IFN-β reporter assay. Cells expressing the same plasmids as in d were treated with MOCK, or purified E. coli DNA (EC DNA), synthetic 70mer of Vaccinia virus DNA (VAC70), infection by modified vaccinia Ankara virus (MVA), or infection by HSV-1 to trigger the cGAS/STING pathway. Results are representative of two independent experiments and are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological replicates. (unpaired Student’s t-test). f, IFN-β reporter assay using cells expressing (human cGAS and human STING) or (human cGAS and murine STING) to induce the promoter in the presence of empty vector, DENV NS2B3 WT or NS2B3–S135A for each case. Results are representative of two independent experiments and are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological replicates (one-way ANOVA). WB, western blot; IP, immunoprecipitation; NS, not significant.

The ability of the DENV NS2B3 protease complex to affect STING-mediated type I IFN induction has been shown to rely on its proteolytic activity10,11,13. To explore the DENV protease inhibition of cGAS/STING-dependent DNA sensing, we used an IFN-β reporter cell system13 (lacking detectable levels of endogenous STING or cGAS (ref. 9), Supplementary Fig. 2a). Next, we tested cGAS-dependent IFN-β-luciferase activation, by co-transfecting STING and cGAS along with either an empty vector, NS2B3 WT protease or the S135A mutant. Under these conditions, NS2B3 WT significantly inhibited the promoter activity as compared to empty vector and the S135A mutant protease (Fig. 2d). Luciferase induction in the presence of NS2B3–S135A was similar to empty vector (Fig. 2d).

We validated this observation using four different DNA ligands described to stimulate the cGAS/cGAMP/STING pathway9,16,19,20. WT NS2B3 protease significantly inhibited IFN-β promoter activity with all four cGAS ligands, when compared to the proteolytically inactive mutant control, demonstrating that NS2B3 catalytic activity is necessary for its antagonistic effect (Fig. 2e). Finally, to address the independent contribution of NS2B3 on cGAS inhibition versus STING inhibition, we used either human cGAS and human STING (hcGAS+hSTING) or human cGAS and murine STING (hcGAS+mSTING), which cannot be cleaved by the DENV protease but can efficiently stimulate the IFN-β promoter in human cells (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Even with a cleavage-resistant STING (mSTING), DENV NS2B3 is able to significantly inhibit cGAS-dependent IFN-β promoter activation (Fig. 2f ). These results demonstrate that DENV NS2B3 can antagonize both cGAS and STING functions.

cGAS degradation is mediated by the NS2B protease cofactor.

To characterize cGAS degradation by the DENV protease complex, we performed systematic mutations of the potential NS2B3 cleavage sites in cGAS (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, alanine substitutions in the predicted site did not prevent cGAS processing by the DENV protease (Supplementary Fig. 3a), suggesting that cGAS is not a substrate for the DENV NS2B3 protease as defined by its known cleavage target sequences21. We then evaluated the involvement of the individual NS2B3 components, NS2B and NS3, in cGAS degradation.

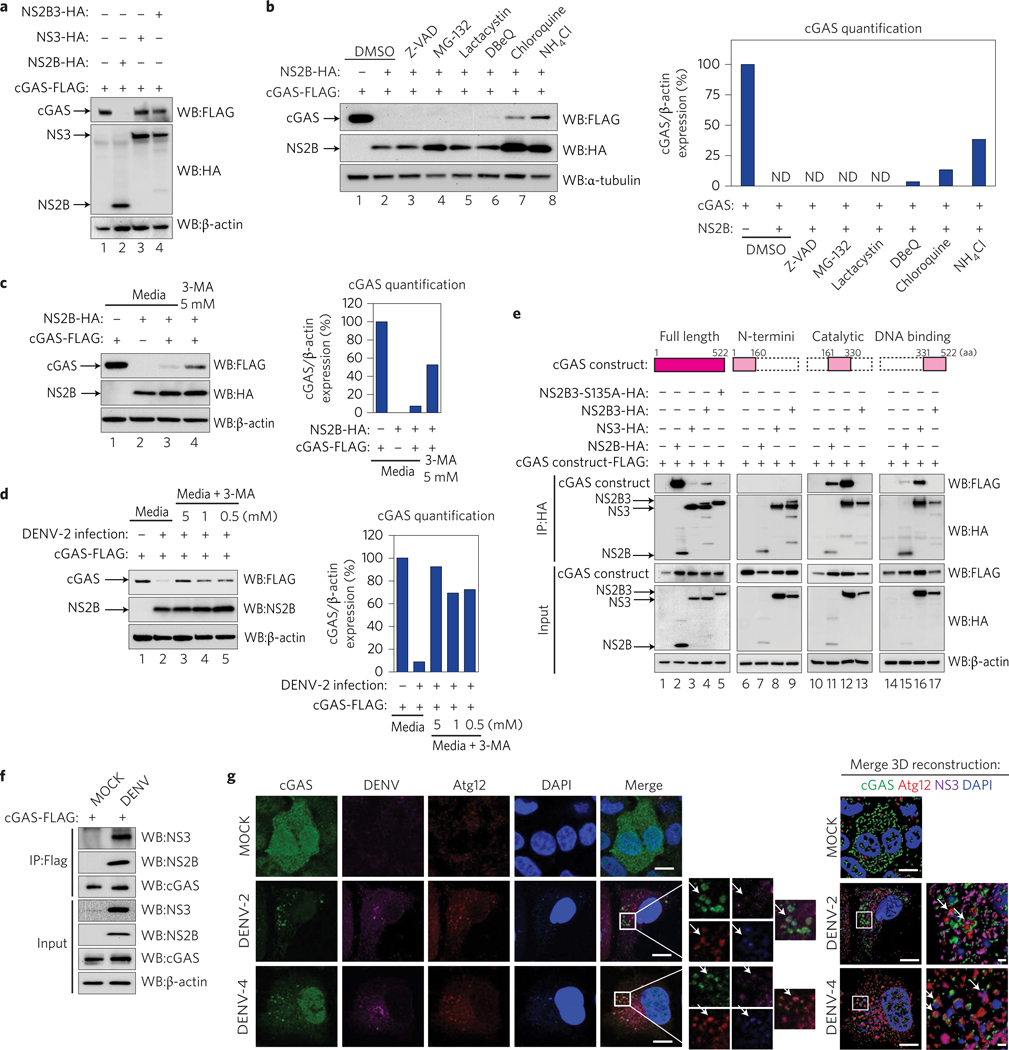

We performed co-expression experiments of human cGAS alongside either NS2B alone, NS3 alone, or the complete NS2B3 WT (Fig. 3a). Surprisingly, this analysis showed a drastic degradation of cGAS in the presence of the protease cofactor NS2B expressed by itself, whereas no degradation was observed with NS3 alone (Fig. 3a). These results indicate that NS2B alone is able to mediate cGAS degradation, and that the NS2B3 catalytic activity we found to be necessary is required to liberate NS2B, by self-cleavage, from the DENV polyprotein. NS2B expression did not affect an unrelated protein when tested (Supplementary Fig. 3b).We also observed that, similarly to the human version of cGAS, murine cGAS is efficiently degraded by NS2B (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

Figure 3 |. NS2B protease cofactor degrades cGAS in an autophagy–lysosome-dependent mechanism.

a, Evaluation of cGAS degradation by NS2B3 protease or its components. Expression analysis of human cGAS and empty vector, DENV NS2B, NS3 or NS2B3, performed in 293T cells (48 h) by SDS–PAGE/western blot. b, Evaluation of the mechanism of cGAS degradation by DENV NS2B. Co-expression of cGAS-FLAG and DENV NS2B-HA in 293T cells in the presence of DMSO, Z-VAD-FMK (5uM), MG-132 (5 μM), clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (lactacystin) (1 μM), DBeQ (5 μM), chloroquine (5 μM) or NH4Cl (2 mM). cGAS, DENV NS2B and α-tubulin expression levels were analysed by western blot. Bar graph: densitometry analysis of cGAS protein by ImageJ software. c,d, Analysis of cGAS degradation by NS2B (c) or DENV-2 infection (MOI = 10) (d) in the presence of 3-MA (autophagosome formation inhibitor). Densitometry analysis of cGAS protein by ImageJ software. e, Analysis of the interaction between DENV HA-tagged NS2B, NS3, NS2B3 protease complex WT or S135A mutant with human full-length cGAS-FLAG or cGAS domains by co-immunoprecipitation in 293T cells. f, Analysis of cGAS and viral proteins interaction during infection. Immunoprecipitation of cGAS-FLAG in 293T cells MOCK or DENV-2 infected for 12 h. Immunodetection of viral proteins NS3 and NS2B by western blot, using specific antibodies. g, Analysis of cGAS in DENV-infected cells by immunofluorescence: A549 cells expressing cGAS-V5 were infected MOCK or with DENV-2 or DENV-4. At 24 or 48 h.p.i., cells were fixed and processed for indirect immunofluorescence (see Methods). Primary antibodies against V5 (cGAS), autophagy marker (Atg12) or DENV NS3 protein were used. Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies −488 (green), −568 (red) and −647 (magenta) were used to detect the primary antibodies, respectively. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Images on the right correspond to the squared zoomed images in each panel. Scale bars, 10 μm. A detailed three-dimensional reconstruction of the Z-stacks is shown top right. Scale bars, 0.5 μm. Arrows mark co-localization of cGAS with autophagosomes and viral protein. ND, not detected.

To determine the cellular machinery responsible for cGAS degradation by NS2B, we performed co-expression experiments in the presence of compounds shown to inhibit different protein degradation pathways, as indicated in the following. As expected, NS2B was able to degrade cGAS in the presence of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, vehicle control), but also in the presence of Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspases inhibitor), MG-132 or clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (proteasome inhibitors) (Fig. 3b, lanes 2–5). A modest recovery of cGAS expression was observed in the presence of the DBeQ inhibitor of P97 (involved in ER-dependent degradation and, to a lesser extent, autophagosome maturation) (Fig. 3b, lane 6). Interestingly, when we tested NSB2-dependent cGAS degradation in the presence of the lysosomal acidification inhibitors chloroquine and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), a more robust recovery of cGAS expression was observed (Fig. 3b, lanes 7 and 8).

Cellular autophagy is a mechanism that has been shown to be induced early during DENV infection22. Thus, to confirm the involvement of the autophagy pathway in cGAS degradation via DENV NS2B, we co-expressed cGAS and NS2B in cells cultured in the presence or absence of the autophagosome-formation inhibitor 3-MA (ref. 23). Inhibition of autophagy by 3-MA (0.5–5 mM) clearly recovered the expression of cGAS in the presence of overexpressed DENV NS2B (Fig. 3c) as well as in the context of DENV infection (Fig. 3d).Taken together, our results show that DENV NS2B efficiently interacts with cGAS and specifically promotes its degradation via an autophagy–lysosomal-dependent pathway (Fig. 3b–d).

We then studied the interaction of the DENV protease and its individual components with cGAS and mapped their physical interplay by expressing the three most relevant cGAS domains individually, as shown in Fig. 3e and the Methods.

293T cells were transfected overnight with plasmids encoding individual components of the DENV protease and the specified cGAS constructs and samples were co-immunoprecipitated. Figure 3e shows that NS2B efficiently co-immunoprecipitates with cGAS (full-length, FL) (Fig. 3e, lane 2). NS3 and the NS2B3 complex also bound cGAS, although less efficiently (Fig. 3e, lanes 3 and 4). Furthermore, the lack of interaction observed between the proteolytically inactive mutant NS2B3–S135A and cGAS (FL) was highly reproducible (Fig. 3e, lane 5 and Fig. 2c). The N-terminal domain of cGAS did not show interaction with the DENV protease or its components. However, the catalytic and DNA binding domains show interactions with both NS2B and NS3 (Fig. 3e, lanes 11, 12, 15 and 16) indicating that both components of the DENV protease (NS2B and NS3) physically interact with the two most crucial functional domains of cGAS (ref. 24). Interestingly, NS2B3 did not show any interaction with these individual domains of cGAS by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 3e, lanes 13 and 17). We then validated the observed interaction between cGAS and NS2B3 in the context of DENV infection. For this, 293T cells transiently expressing cGAS-FLAG were infected MOCK or with DENV-2 for 12 h, then cGAS was immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG antibody. We detected the presence of both DENV NS3 and NS2B bound to cGAS by western blot analysis using specific antibodies (Fig. 3f ).

Finally, we performed immunofluorescence assays to visualize the localization of cGAS during DENV infection. A549 cells were transduced with a lentivirus expressing cGAS-V5. In MOCK-treated cells we observed a homogeneous distribution of cGAS throughout the cells (Fig. 3g, top row). In contrast, in DENV-2 and DENV-4 infected cells, we confirmed the degradation and observed a redistribution of cGAS, forming puncta-like structures (Fig. 3g). These cGAS-containing puncta co-localized with the autophagosome formation marker Atg12, with the NS3 protein and with DAPI stained areas, suggesting the presence of DNA in the autophagosomes during DENV infection.

These data indicate that during DENV infection, cGAS co-localizes with autophagosomes together with viral proteins, and this may facilitate the observed degradation of cGAS in the lysosome.

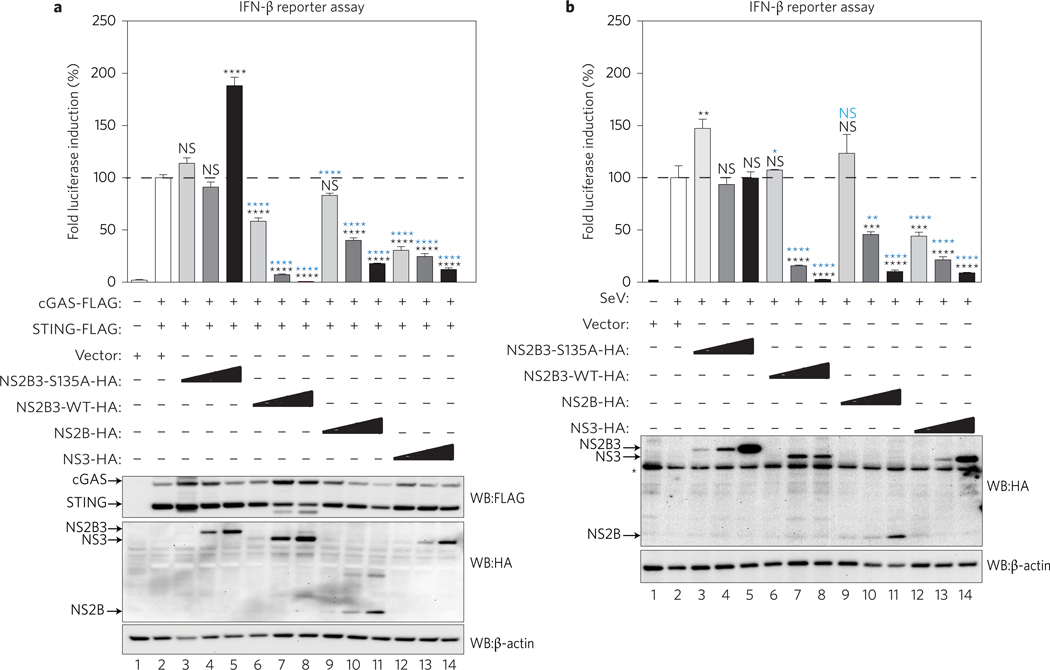

DENV protease components counteract the cGAS/STING pathway.

To evaluate the impact of the DENV protease individual components on the activation of the cGAS/STING pathway, we overexpressed these proteins in IFN-β reporter cells (Fig. 4a). In parallel, we also evaluated the impact of the DENV protease components on the RIG-I like receptors (RLR) pathway after infection with Sendai virus (SeV) (Fig. 4b). We co-expressed cGAS and STING with three different concentrations of the DENV NS2B, NS3, NS2B3 WT, as well as mutant NS2B3–S135A into our reporter cells. The complete NS2B3 protease and its individual components, NS2B and NS3, reduced the ability of cGAS/STING to induce the IFN-β promoter in a dose-dependent manner, as compared to empty vector and the catalytically mutant protease NS2B3–S135A (Fig. 4a). DENV NS2B inhibition was shown to be cGAS-specific because no direct interaction with STING was observed by co-immunoprecipitation (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The inhibition observed with NS3 expression could be mediated by physical interaction with the two most critical cGAS domains (Fig. 3e) and STING (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The antagonistic properties of the protease components were also validated using other sources of stimulatory DNA, named Poly dA:dT, Escherichia coli DNA and MVA infection (Supplementary Fig. 4b).

Figure 4 |. DENV protease complex and its components counteract the cGAS/STING pathway.

Evaluation of the DENV protease components as antagonists of the cGAS/STING pathway by IFN-β reporter assay. 293T reporter cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding human cGAS, STING, plus empty vector, proteolytically inactive NS2B3 mutant (NS2B3–S135A), DENV WT protease (NS2B3 WT), NS2B or NS3 expressed individually. In every case, three different plasmids concentrations were used to evaluate a dose-dependent effect. a, The cGAS/STING pathway was activated by co-expression of the two proteins. Results are representative of two independent experiments and are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological replicates. P values: lanes 2–3, P = 0.2783; lanes 2–4, P = 0.8536; lanes 2–5, 2–6, 2–7 and 2–8, P < 0.0001; lanes 2–9, P = 0.0822; lanes 2–10, 2–11, 2–12, 2–13 and 2–14, P < 0.0001; lanes 3–6, 3–9 and 3–12, P < 0.0001; lanes 4–7, 4–10 and 4–13, P < 0.0001; lanes 5–8, 5–11 and 5–14, P < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA). b, Infection with Sendai virus (SeV) as an inducer of the RIG-I-like receptors pathway. Results are representative of two independent experiments and are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological replicates. P values: lanes 2–3, P = 0.0022; lanes 2–4, P > 0.999; lanes 2–5, P > 0.999; lanes 2–6, P > 0.999; lanes 2–7 and 2–8, P < 0.0001; lanes 2–9, P = 0.4737; lanes 2–10, P = 0.0003; lanes 2–11, P < 0.0001; lanes 2–12, P = 0.0002; lanes 2–13 and 2–14, P < 0.0001; lanes 3–6, P = 0.0152; lanes 3–9, P = 0.4481; lanes 3–12, P < 0.0001; lanes 4–7, P < 0.0001; lanes 4–10, P = 0.0018; lanes 4–13, P < 0.0001; lanes 5–8, 5–11 and 5–14, P < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA). NS, not significant. Protein expression control for a and b is shown. *Unspecific band. Asterisk in black represents specific P values obtained against empty vector control (lane 2 condition). Asterisk in blue represents P values obtained against the corresponding concentration of NS2B3–S135A plasmid (lanes 3 to 5 conditions).

In agreement with previous reports13,25, Fig. 4b shows that NS2B3 WT and NS3 also inhibited the RLR pathway triggered by SeV infection, although less efficiently than the inhibition observed for the cGAS/STING DNA sensing pathway shown in Fig. 4a. Furthermore, NS2B also inhibited the RLR pathway when compared with empty vector and the catalytically mutant protease control NS2B3–S135A, but less efficiently than NS2B3 or NS3 (Fig. 4b, lanes 9–11). These results confirm the ability of the DENV protease complex and its individual components to efficiently counteract cGAS/STING-mediated type I IFN production.

cGAS restricts DENV replication.

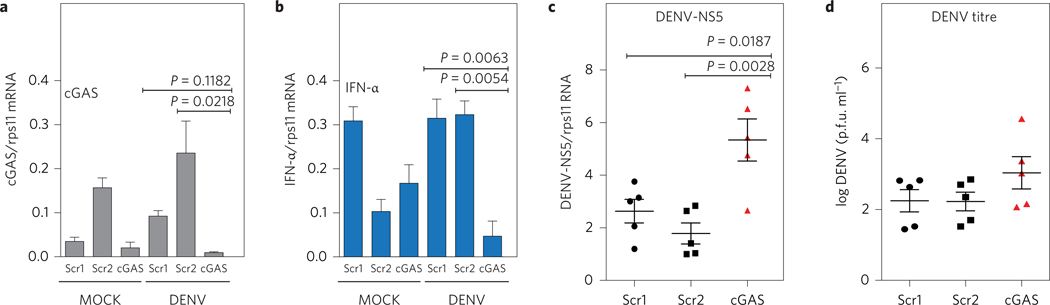

To investigate the impact of cGAS on DENV replication, we transfected either a cGAS-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) or two scrambled siRNAs as control into human MDDCs, and subsequently infected them with an MOI = 0.5 of DENV-2 (Fig. 5a). Specific silencing of cGAS significantly affected the ability of MDDCs to produce IFN-α mRNA after DENV infection (Fig. 5b). We also observed a significantly higher accumulation of viral RNA in MDDCs from all five donors tested, when pretreated with cGAS-specific siRNA as compared with two control siRNAs (Fig. 5c). Additionally, we could detect a modest increase in the production of infectious viral particles in the supernatant of these cells (Fig. 5d), suggesting that cGAS has an inhibitory role in DENV replication. Interestingly, a similar observation was reported for another flavivirus, West Nile virus (WNV), in cGAS KO mice26. Alongside our previous observations about the role of STING in DENV replication10, these data suggest a general inhibitory effect of the cGAS–STING pathway in reducing flavivirus infection.

Figure 5 |. cGAS restricts DENV replication.

Silencing of endogenous cGAS in primary human MDDCs. MDDCs from five independent donors were transfected with a specific cGAS siRNA or two different scramble siRNA as described in the Methods. At 48 h.p.i., cells were MOCK or DENV-2-infected (MOI = 0.5). a, Relative levels of cGAS mRNA were quantified by RT–qPCR at 4 h.p.i. b, Relative levels of IFN-α mRNA were quantified by RT–qPCR at 24 h.p.i. (data shows one representative donor out of five). Results are one representative of five independent experiments and are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological replicates (one-way ANOVA). c, Accumulation of DENV RNA was measured by RT–qPCR at 48 h.p.i. for the five donors tested. Results are expressed as mean from each of the five independent donors. Error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. d, Infectious DENV particles were quantified in the supernatant at 24 h.p.i. by plaque assay. Data show the mean ± s.e.m for five independent donors tested and showed a normal distribution.

cGAS detects mitochondrial DNA during DENV infection.

Although cGAS has been characterized as a DNA sensor, it has been demonstrated to have antiviral properties against different positive-strand RNA viruses26. However, how cGAS is involved in the detection of RNA viruses remains unknown. Consistent with a previously published report19, we did not observe detectable amounts of RNA bound to cGAS in DENV-infected cells (Supplementary Fig. 5a).

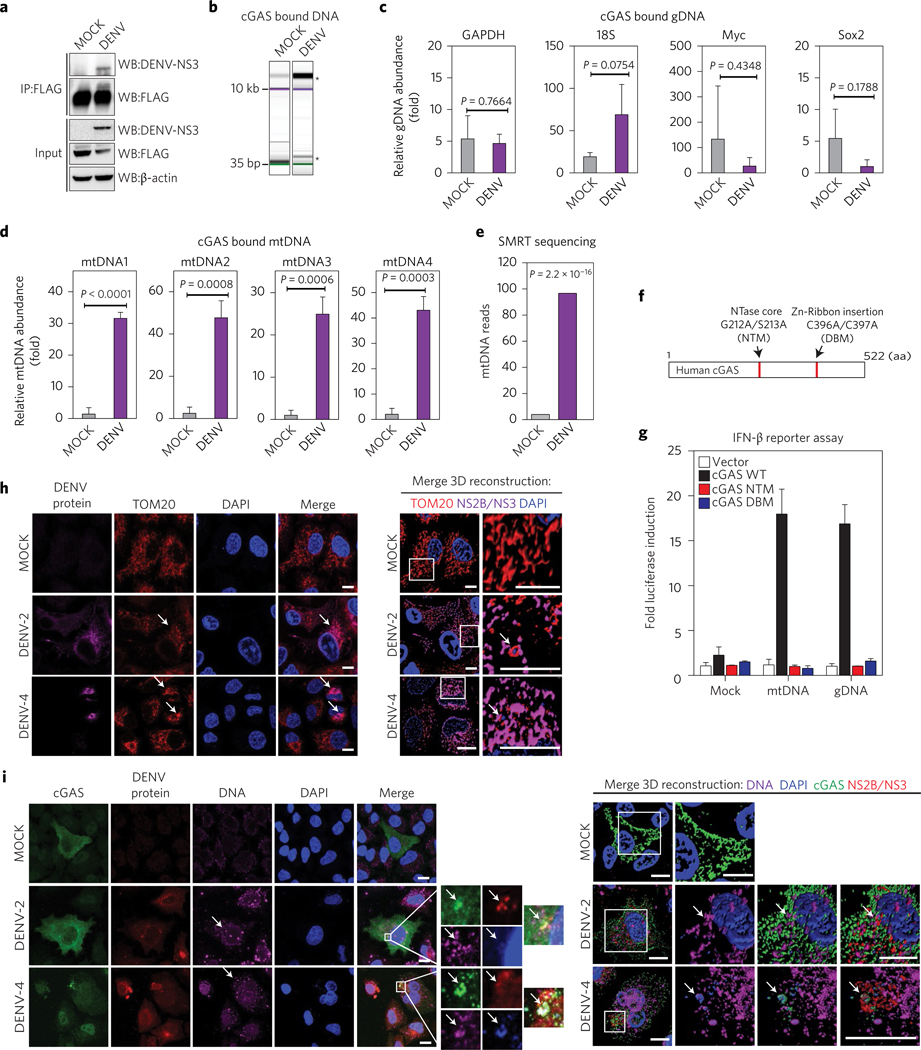

Thus, to explore and characterize the DNA that could trigger the cGAS/STING pathway in DENV-infected cells, we used 293T-cGAS-FLAG cells to perform experiments that sequentially included immunoprecipitation, specific quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and single molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing. We treated either MOCK or DENV (MOI = 5) infected samples of 1 × 107 cells for 24 h. The cells were then pelleted and the lysates were subjected to cGAS pulldown using an anti-FLAG-specific antibody. Whole-cell extracts (Input) and immunoprecipitated fractions were analysed by western blot (Fig. 6a). The DNA bound to cGAS in both conditions was extracted, purified and analysed by electrophoresis. Bioanalyser data showed a wide range of distribution of DNA sizes for both MOCK and DENV conditions (∼20 kbp to ∼35 bp). For DENV-infected conditions, in particular, a high-molecular-weight band (∼15–20 kbp) was enriched for three independent immunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 6b). We then evaluated the relative abundance of different (randomly selected) genomic (gDNA) versus mitochondrial (mtDNA) DNA in samples from three independent pulldown experiments by qPCR, using enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) DNA as reference (see Methods for primer sequences). No significant differences in the abundance of gDNA fragments bound to cGAS were detected between MOCK and DENV-infected cells, which suggests a stochastic abundance of these DNAs for the two analysed conditions (Fig. 6c). On the other hand, quantification of mitochondrial DNA bound to cGAS using the same approach showed an average enrichment of at least 20-fold for all mtDNA fragments tested in DENV-infected versus MOCK-infected conditions, which demonstrates that mtDNA is enriched and is bound to cGAS during DENV infection (Fig. 6d). This was confirmed by SMRT sequencing analysis of the two DNA fractions. Figure 6e shows the number of reads mapped for the human mitochondrial DNA genome in purified cGAS from MOCK- and DENV-infected cells.

Figure 6 |. cGAS binds mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) during DENV infection.

a, cGAS immunoprecipitation (IP). Total lysates and IP fractions were used to detect cGAS-FLAG, DENV NS3 and β-actin by SDS–PAGE/western blot. b, Analysis of DNA bound to IP cGAS from MOCK, DENV conditions by DNA electrophoresis (Bioanalyzer). *Enriched DNA bands. Relative enrichment of genomic DNA in cGAS pulldown from MOCK and DENV conditions. c, RT–qPCR for GAPDH, 18S, Myc and Sox2 DNAs, relative to EGFP DNA. d, Relative enrichment of mtDNA in cGAS pulldown from both conditions. RT–qPCR for four sets of primers that amplify fragments from different regions of the human mtDNA43. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. from three IP experiments, (unpaired Student’s t-test). e, SMRT sequencing analysis of purified DNA from cGAS pulldowns in MOCK or DENV conditions (Fisher’s exact test). f, Schematic representation of human cGAS aminoacidic sequence, NTase mutant (G212A/S213A) or DNA binding core domain mutant (C396A/C397A). NTM, nucleotidyltransferase mutant; DBM, DNA binding mutant. g, IFN-reporter assay. 293T–STING–IFN-β–Luc expressing cGAS WT, or cGAS mutants were stimulated with MOCK, mtDNA or gDNA and luciferase induction was measured. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological replicates h, Analysis of mitochondria distribution and morphology during DENV infection by immunofluorescence. A549 cells were infected MOCK or with DENV-2 or DENV-4. At 24 h.p.i. cells were fixed and stained with TOM20, DENV-2 NS2B or DENV-4 NS3. Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies −568 (red) and −647 (magenta) were used to detect the primary antibodies, respectively. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Arrows mark co-localization of aggregated mitochondria and viral proteins. A detailed three-dimensional reconstruction of the Z-stacks is shown on the right. i, Detection of cytoplasmic DNA by immunofluorescence. A549 cells expressing cGAS-V5 were infected MOCK or with DENV-2 or DENV-4. Primary antibodies against V5 (cGAS), single-stranded DNA, DENV-2 NS2B or DENV-4 NS3 protein were used. Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies −488 (green), −647 (magenta) and −568 (red) were used to detect the primary antibodies, respectively. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Images on the right indicate the squared zoom in each panel. A detailed three-dimensional reconstruction of the Z-stacks is shown on the right. Scale bars, 10 μm. Arrows mark co-localization of cGAS with viral protein and DNA.

To verify the ability of mtDNA to induce type I IFN responses through cGAS, we used isolated DNA from either the mitochondria or nucleus of 293T cells to stimulate 293T–STING reporter cells expressing either WT cGAS or inactive mutant versions (see Methods and Fig. 6f ). Both purified mtDNA and gDNA were able to induce the IFN-β promoter in a cGAS-dependent manner, confirming that DNA detection by this sensor is not sequence-specific and any type of DNA bound to it can trigger the cGAS/cGAMP/STING-dependent type I IFN pathway (Fig. 6g). Mitochondrial dysfunction during DENV infection has been documented by several groups27–29. Using immunofluorescence assay, after staining for mitochondrial marker TOM20 in MOCK- and DENV-infected cells, we observed an altered mitochondria distribution and morphology in DENV-infected cells when compared to MOCK-treated cells (Fig. 6h). In cells infected with both DENV-2 and DENV-4, mitochondria appeared fragmented and aggregated compared to MOCK cells conditions. Also, TOM20 co-localized with NS2B protein (in DENV-2 infection) and NS3 protein (used to detect DENV-4 infection) (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Fig. 5b). Furthermore, staining for DNA with a specific antibody in cGAS-expressing cells showed a higher abundance of free DNA in the cytoplasm of infected cells than in MOCK cells (Fig. 6i). We found that free DNA co-localized with cGAS, with NS2B protein (in DENV-2 infection) and NS3 protein (in DENV-4 infection) and also with DAPI-stained areas. All these data strongly suggest that mitochondrial damage and the subsequent release of mtDNA to the cytoplasm is an intrinsic collateral damage observed during DENV infection. The results shown here identify mtDNA as a ligand of cGAS in DENV-infected cells.

Discussion

Since its characterization, cGAS has been proposed as a DNA sensor that can specifically activate the adaptor STING to induce type I IFNs9. Such activation occurs not only during the detection of infection by DNA viruses9,16,20,30, but also during the sensing of misplaced self DNA in the cell31,32. Interestingly, cGAS has also shown a striking antiviral property against several positive-strand RNA viruses, including members of the Flavivirus family26,33, suggesting that common features observed during the positive-strand RNA virus life cycle, such as the massive rearrangement of internal membranes, may trigger a mislocalization of cellular DNA that could serve as a substrate to activate the cGAS/STING pathway. To evaluate the role of this PRR during DENV infection, we studied the status and expression levels of cGAS and its interplay with the viral NS2B3 protease complex. Performing biochemical and functional analysis in cell lines and primary systems, we observed a drastic degradation of cGAS that was mediated by the DENV protease cofactor NS2B. This degradation was rescued by treatment with inhibitors of autophagosome formation, lysosome acidification and also confirmed by immunofluorescence assays, demonstrating that cGAS is degraded through this mechanism during DENV infection. Furthermore, the proteolytically active NS2B3 complex and the combined effect of its individual components, NS2B and NS3, showed a significant inhibitory effect on the cGAS/STING pathway, highlighting the relevance of this cellular mechanism to detect and respond to DENV infection.

cGAS has been shown to participate not only in the production of type I IFN after the detection of cytoplasmic DNA, but also in autophagy, as a mechanism to eliminate unwanted DNAs in the cytosol. Autophagy is known to be upregulated during DENV infection22, and this would expedite cGAS degradation through its interaction with NS2B.

As DENV translates its polyprotein as one of the first molecular events upon entry into the target cell, DENV proteins quickly colonize the ER membrane to prepare the scaffold necessary for replication. This accumulation of viral proteins also reaches the membrane of the mitochondria, which are in close proximity for calcium interchange with the ER and lipids biosynthesis34. Thus, DENV infection greatly affects this vital organelle, which is also an important hub for innate immune signalling. The interplay between DENV and the mitochondria is a field of increasing interest. It has been reported that the C-terminus of the DENV M protein targets the mitochondrial membrane, causing its permeabilization, matrix swelling and mitochondrial membrane potential loss27,28. A recent report showed that the NS2B3 protease localizes in the mitochondria outer membrane and cleaves mitofusins 1 and 2, affecting mitochondrial architecture and function upon infection35. Here, we provide evidence that cGAS is part of the cellular machinery system that senses mitochondrial damage during DENV infection to initiate type I IFN responses. Our data show that mtDNA is able to trigger the induction of the IFN-β promoter through cGAS, behaving as a danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) released during DENV infection. Furthermore, DENV uses active mechanisms to specifically counteract this pathway by targeting two crucial host proteins involved in cytoplasmic RNA and DNA detection—STING and cGAS10,11,19,26,30. Targeting cGAS not only decreases the activation of STING in the infected cell, but also minimizes the translocation of cGAMPs to bystander cells via tight junctions36. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of a virus targeting cGAS for degradation, paradoxically an RNA virus. This is also the first report of an IFN antagonist function for the DENV protease cofactor NS2B. Finally, we provide data that shed light on the molecular mechanism of virus detection by cGAS and have expanded the knowledge of the strategies used by DENV to evade innate immune responses.

Methods

Cell lines.

293T cells (ATCC CRL-3216) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Baby hamster kidney cells (BHK) (originally from ATCC, obtained from S. Shresta, LaJolla Immunology Institute) were grown in Glasgow minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 20 mM HEPES. Mosquito cells derived from Aedes albopictus, clone C6/36 (originally obtained from J. Munoz-Jordan, CDC, Puerto Rico), were expanded at 33 °C in RPMI medium with 10% FBS. All media were supplemented with 100 U ml−1 L-glutamine and 100 μg ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin. All tissue culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen. The 293T–IFN-β reporter cells described in ref. 13 were transduced with lentiviruses expressing human STING10. These cells were sorted based on GFP expression. Individual clones were isolated and expanded, then tested for reporter gene expression upon SeV infection. The cells generated, named 293T–STING–IFN-β–FFLuc were then maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin and 2 mg ml−1 geneticin. These cells were used for some experiments in this report. 293T cells, as well as the stable 293T–IFN-β–FFluc or STING–293T–IFN-β–FFluc cells were transfected with plasmids encoding for WT cGAS or cGAS NTase core mutant (G212A/S213A) or cGAS Zn-Ribbon insertion mutant (C396A/C397A (pCMV6backbone from Origene).

Cell lines from ATCC were authenticated by ATCC and were not validated further in our laboratory. Cells from the CDC were not validated further in our laboratory. All cell lines and virus preparations used in this manuscript were tested in our laboratory for the presence of mycoplasma using the MycoalertTM mycoplasma detection kit from Lonza (cat. no. LT07–118) and were mycoplasma free.

Viruses.

Dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2) strains 16681, Dengue virus serotype 4 (DENV-4) strain 1036 Indonesia 1976 and Newcastle disease virus (NDV) strain La Sota, were used in this study. DENV-2 and −4 were grown in C6/36 insect cells for 6 days as described elsewhere37. Briefly, C6/36 cells were infected at an MOI of 0.01 and, 6 days after infection, cell supernatants were collected, clarified and stored at 80 °C. The titres of DENV stocks were determined by limiting-dilution plaque assay on BHK cells38. NDV was grown in embryonated chicken eggs and titrated as previously described12. MVA and herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) viral aliquots were provided by B. tenOever and B. Herold, respectively.

Generation of MDDCs.

Human MDDCs were obtained from healthy human blood donors (New York Blood Center), following a standard protocol as previously described12. Briefly, after Ficoll–Hypaque gradient centrifugation, CD14+ cells were isolated from the mononuclear fraction using a MACS CD14 isolation kit (Milteny Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CD14+ cells were then differentiated to naive dendritic cells by incubation for 5–6 days in dendritic cell (DC) medium (RPMI supplemented with 100 U ml−1 L-glutamine, 100 g ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin and 1 mM sodium pyruvate) with the presence of 500 U ml−1 human granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulated factor (GM-CSF) (PeproTech), 1,000 U ml−1 human interleukin 4 (IL-4) (PeproTech) and 10% FBS (Hyclone). The purity of the dendritic cells was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis and at least 99% were CD11c+, CD86low, CD83−, HLA-DRlow and CD14-cultured for 5 days at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Fresh medium was added every 2–3 days. Blood from healthy human donors were obtained from the New York Blood Center. The samples were anonymous. This constitutes exempt research and does not require IRB review.

Dengue infection of MDDCs.

At day 5 of differentiation from monocytes as described above, samples from 3 × 105 to 1 × 106 MDDCs were resuspended in 100 μl of DC medium and were infected for 45 min at 37 °C with the indicated MOI of virus (diluted in DC medium) or with DC medium (mock group) to a total volume of 200 μl. After the adsorption period, DC medium supplemented with 10% FBS was added to a final volume of 1 ml and cells were incubated for the appropriate time at 37 °C.

Virus co-infection of MDDCs.

Primary human MDDCs were treated either with MOCK, or DENV at an MOI of 5, for 12 h. Cells were then MOCK-treated or infected with MVA–GFP virus, which can be sensed by the cGAS/STING pathway using an MOI of 1 (ref. 16). Second infection was stopped at the specified time and total RNA was extracted to analyse gene induction by reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR).

IFN-β reporter assay.

293T cells expressing firefly luciferase under the control of the IFN-β promoter (293T–IFN-β reporter cells13) or 293T–STING–IFN-β reporter cells were transfected by using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Induction of the IFN-β promoter in these reporter cells was measured by detection of firefly luciferase activity as described previously13. The ability of different proteins to inhibit the IFN-β promoter was assessed in 293T–IFN-β reporter cells seeded on 24- or 96-well plates and transiently transfected with a total of 200–400 ng of various expression plasmids expressing human cGAS–pCMV6 (Origene), STING–pcDNA or the DENV proteins cloned in a pCAGGS background as described in refs 10 and 13. Then, 18 or 24 h later, the luciferase activity in the total cell lysate was measured by using the Promega luciferase assay system according to the manufacturer’s directions.

Immunoblot analysis.

Transfection of 293T cells and infection of human dendritic cells was performed as described in the sections ‘Dengue infection of MDDCs’, ‘Virus co-infection of MDDCs’ and ‘IFN-β reporter assay’. Cell lysates were obtained after incubation of cells with RIPA lysis buffer (Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor (Roche) and resuspended in a total of 50 μl of Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad). Crude lysates were boiled for 5 min and then kept on ice. Each sample was loaded in a polyacrylamide–SDS gel and the proteins were electrophoretically separated by conventional methods. The proteins in the polyacrylamide gel were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and blots were incubated with anti-FLAG, anti-haemagglutinin (HA), anti-β-actin (Sigma Aldrich) and rabbit polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies anti-DENV NS3 were validated in refs 10 and 39 anti-DENV NS2B was purchased from GeneTex. Antibodies against cGAS and STING were purchased from Cell Signalling. Antibody–protein complexes were detected using a Western Lighting chemiluminescence system (Perkin Elmer).

Evaluation of the mechanism of cGAS degradation by DENV NS2B.

293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding cGAS-FLAG and DENV NS2B-HA or infected with DENV-2 (MOI = 10). After 30 h, cells were treated with DMSO, Z-VAD-FMK (5 μM, Promega), MG-132 (5 μM, Sigma), clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (1 μM, Sigma), DBeQ (5 μM, Sigma), chloroquine (5 μM, Sigma) or NH4Cl (2 mM, Sigma) 3-MA (0.5–5 mM, Sigma) for 6–12 h. Cells were then lysed, and cell extracts were used to quantify expression of cGAS and DENV NS2B using anti-FLAG, anti-HA or anti-NS2B antibodies.

Generation of cGAS constructs.

To map the interaction of DENV protease components and cGAS, the three most relevant domains of this protein were cloned into pCMV6 plasmid to express the individual fragments. The N-terminal domain (residues 1–160) includes the most variable region and has not been reported to have a known function24. The region spanning amino acids 161–330 encompasses the NTase catalytic domain (involved in the synthesis of cGAMPs), and the region from amino acids 331 to 522 contains a series of residues responsible for the recognition of DNA (Zn thumb) by cGAS. Specific mutations in the latter two domains have been demonstrated to ablate the synthesis of cGAMPs by cGAS and the consequent type I IFN production through this pathway.

Immunofluorescence.

A549 cells expressing V5-cGAS were cultured in glassbottom 12-well plates (MaTtek) or 1.5 coverslips (MaTtek) Cells were infected MOCK or with DENV-2 (16681) or DENV-4 (1036). After 24 or 48 hours post infection (h.p.i.), cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde 4% or cold methanol and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Samples were incubated for the primary antibodies for 2 h, washed three times with PBS and incubated for 1 h with the secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor-conjugated mouse 647, rabbit 594 or goat 488 (Life Technologies), as indicated. Cells were washed again with PBS. Nuclei were stained with 1 μg ml−1 DAPI (Invitrogen).

The antibodies used were as follows: anti-Atg12 rabbit (2010, Cell Signaling), anti-DNA mouse (CBL186, Millipore), anti-TOM20 rabbit (SC11415, Santa Cruz) and anti-V5 goat (83849, Santa Cruz).

Microscope image acquisition.

Confocal laser scanning was performed using a Zeiss LSM 880 Meta (Carl Zeiss Microimaging) fitted with a Plan Apochromatic ×63/1.4 or ×40/1.4 oil objective. Images were collected at 16 bits and a resolution of 1,024×1,024 pixels. Image processing and analysis of intensity profiles were carried out using Fiji/Image J software. Where indicated, Amira 3D software (FEI Visualization Sciences Group) was used to achieve three-dimensional rendering, and image processing and analysis were carried out using Fiji/ImageJ software as described in ref. 40.

Induction of cGAS/STING pathway.

The cGAS/STING pathway was induced by different methods, including transfection of synthetic or purified bacterial DNA, Poly-dA:dT (1 μg per well, Invivogen), Synthetic 70mer of Vaccinia virus DNA (VAC70 from Invivogen), purified E. coli DNA (1 μg per well, Invivogene), purified mtDNA or gDNA from human cells or infection with DNA viruses (MVA or HSV-1, described in the section “Viruses”). Stimulation of the pathway was carried out for 18–24 h.

cGAS alanine substitution of the putative NS2B3 cleavage site.

Alanine substitutions of amino acids 123–125 in the human cGAS sequence were performed by PCR-directed mutagenesis using Primer-F: GTTCTTGCCGCGCGGCGGCCGCGCGCTGCTC and Primer-R: GAGCAGCGCGCGGCCGCCGCGCGGCAAGAAC to change the putative NS2B3 cleavage site. DNA sequence changes were confirmed by cloning and sequencing.

RNA isolations.

RNA from different cells was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogene), followed by a treatment with DNase using DNA-free Ambion. The concentration was evaluated in a spectrophotometer at 260 nm, and 500 ng RNA was reverse-transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Purification of gDNA and mtDNA.

DNA from either mitochondria (mtDNA) or nucleus (gDNA) were isolated using the mitochondria isolation kit from Thermo Scientific (following the manufacturer’s specifications) to first isolate total mitochondria and nuclei. DNA from each fraction was then purified by extraction with phenol:chloroform followed by RNAse treatment. Finally, DNA precipitation was carried out with isopropanol. Samples were sonicated before use as stimulatory molecules. Purity was confirmed by spectrophotometry.

RT–qPCR.

Evaluation of the relative levels of DNA, expression of human cytokines from different cell types and viral RNA was carried out using iQ SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR temperature profile was 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 60 s. Real-time PCR analysis was carried out using the BioRad 1000C Thermal Cycler. Expression levels were calculated based on the Ct values using two different housekeeping genes (rps11 and/or α-tubulin genes) to normalize the data.

siRNA transfection and dengue infection of human MDDCs.

A total of 2.5 × 104 MDDCs were seeded per well in 96-well plates and transfected with the corresponding siRNA using the StemFect RNA transfection kit (Stemgent), according to the manufacturer instructions. Chemically synthesized 21-nucleotide siRNA duplexes were obtained from Qiagen. The sequence of the cGAS siRNA oligonucleotide used in this study was 5′-CTCGTGCATATTACTTTGTGA-3′. Control siRNAs were obtained from Qiagen. At 48 h after transfection, cells were infected with Dengue virus at MOI = 0.5. Briefly, cells were centrifuged (400g, 10 min), the medium was removed, 25 μl of RPMI containing the appropriate amount of virus was added, and the plates were incubated for 45 min at 37 °C. Then, 75 μl RPMI with 10% FBS was added and cells were incubated at 37 °C for the indicated time. The cells were recovered by centrifugation for 10 min at 400g, and the cell pellets were lysed for RNA isolation.

cGAS pulldown.

Preparation of cell lysates.

A total of 1 × 107 293T–cGAS–FLAG cells were infected with either MOCK of DENV (MOI = 5) for 24 h, then were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000 r.p.m. for 10 min at 4 °C. Cells were washed before and after the spin with PBS. Cell pellets were resuspended in polysome lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP40, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), Complete Protease Inhibitors) and then incubated on ice for 10 min before freezing at −80 °C for 1 h. Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 r.p.m. for 15 min at 4 °C.

Immuno-precipitation.

Protein G agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 11719416001) were washed with NT2 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP40) for 30 min at 4 °C. The washed beads were conjugated with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) at 4 °C overnight. The conjugated beads were then washed and incubated with cell lysate at 4 °C for at least 4 h. Before RNA/DNA extraction, a fraction of agarose beads was eluted using Laemmli Sampler Buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. S3401) and boiled for 5 min to confirm cGAS precipitation by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Protein G agarose beads from each condition were treated with protease K (Ambion) for 30 min at 55 °C and RNA or DNA was extracted using either acidic or basic phenol-chlorophorm, respectively (Invitrogen). The aqueous phase was collected and mixed with ethanol, 3 M NaOAc (Ambion) and 5 μl glycogen (Ambion) and stored at −80 °C overnight. RNA or DNA was precipitated by centrifugation for 30 min at 4 °C, washed with ethanol 80% and air-dried before resuspension in pure H2O for further use.

DNA analysis by SMRT sequencing.

DNA samples, purified from cGAS pulldowns under MOCK or DENV conditions, were processed to prepare libraries following standard procedures by the Genomic core facility at The Icahn Institute and Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Single molecule real-time sequencing DNA reads were aligned to the build 38 of the human genome41 using blasr42.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Quantification of IFN-α secretion was analysed using the Multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay from Millipore following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantification of cGAS-bound DNA.

Total DNA extracted from cGAS pulldowns was quantified and size-analysed using electrophoresis. Under each of the conditions (MOCK or DENV), 20 ng of a purified plasmid encoding for the EGFP gene was added. The mix of endogenous DNA and EGFP plasmid was used to quantify the presence of specific DNA fragments by RT–qPCR. Primer sets for human mtDNA are described in ref. 43 and the sequences are shown below. Relative levels of the DNA molecules of interest were calculated based on the Ct values of EGFP gene amplification using the following primers: EGFP-F: ACGGCGACGTAAACGGCCA C; EGFP-R: GCACGCCGTAGGCTAGGGTG, hSox2-F: TTTTGTCGGAGACGGA GAAG, hSox2-R: CATGAGCGTCTTGGTTTTCC, hMyc-F: AAGGACTATCCT GCTGCCAA, hMyc-R: CCTCTTGACATTCTCCTCGG, hGAPDH-F: CTCTGCT CCTCCTGTTCGAC, hGAPDH-R: AATCCGTTGACTCCGACCTT, 18S-F: TAGA GGGACAAGTGGCGTTC, 18S-R: CGCTGAGCCAGTCAGTGT, mtDNA1-F: CA CCCAAGAACAGGGTTTGT, mtDNA1-R: TGGCCATGGGTATGTTGTTAA, mtDNA2-F CTATCACCCTATTAACCACTCA, mtDNA2-R: TTCGCCTGTAATA TTGAACGTA, mtDNA3-F: AATCGAGTAGTACTCCCGATTG, mtDNA3-R: TTCTAGGACGATGGGCATGAAA, mtDNA4-F: AATCCAAGCCTACGTTTTCA CA, mtDNA4-R: AGTATGAGGAGCGTTATGGAGT.

Statistical analysis.

The statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Tukey’s methods or the unpaired, two-tailed, Student’s t-test. P values were calculated using Graphpad Prism 7.2 program. Fisher’s exact test was used for the SMRT sequencing data. Data considered significant had P values less than 0.05. No statistical methods were used to predetermine the sample size. No samples were excluded from the analysis.

Data availability.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Complete blots for all the figures and corresponding molecular weight markers are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank A. Gamarnik and J. Ashour for critical discussions and input, R. Fenutria-Aumesquet for help with the statistical analysis and R. Sebra and G. Deikus for DNA sequencing. This work was supported by NIH/NIAID grants R01AI073450 and 1R21AI116022 (to A.F.-S.), 1U19AI118610 (to A.F.-S. and A.G.-S.) and a DARPA (Prophecy) grant HR0011-11-C-0094 (to A.F.-S.). J.P.-S. is supported in part by PREP grant R25GM64118 from the NIH/NIGMS. L.C.F.M. is supported by NIH-NIGMS grant R01 GM113886. V.S. is partially supported by NIH-NIAID grants R01 AI089246 and P01 AI090935. C.F.B. is supported by NIH/NIAID grant no. AI109945.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available for this paper.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to S.A. and A.F.S.

References

- 1.Uchida L. et al. The dengue virus conceals double-stranded RNA in the intracellular membrane to escape from an interferon response. Sci. Rep 4, 7395 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Espada-Murao LA & Morita K. Delayed cytosolic exposure of Japanese encephalitis virus double-stranded RNA impedes interferon activation and enhances viral dissemination in porcine cells. J. Virol 85, 6736–6749 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goubau D, Deddouche S & Reis e Sousa C. Cytosolic sensing of viruses. Immunity 38, 855–869 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatt S. et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496, 504–507 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welsch S. et al. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe 5, 365–375 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munoz-Jordan JL, Sanchez-Burgos GG, Laurent-Rolle M & Garcia-Sastre A. Inhibition of interferon signaling by dengue virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14333–14338 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashour J, Laurent-Rolle M, Shi PY & Garcia-Sastre A. NS5 of dengue virus mediates STAT2 binding and degradation. J. Virol 83, 5408–5418 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison J, Aguirre S & Fernandez-Sesma A. Innate immunity evasion by dengue virus. Viruses 4, 397–413 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X & Chen ZJ Cyclic GMP–AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 339, 786–791 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguirre S. et al. DENV inhibits type I IFN production in infected cells by cleaving human STING. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002934 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu CY et al. Dengue virus targets the adaptor protein MITA to subvert host innate immunity. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002780 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez-Madoz JR, Bernal-Rubio D, Kaminski D, Boyd K & Fernandez-Sesma A. Dengue virus inhibits the production of type I interferon in primary human dendritic cells. J. Virol 84, 4845–4850 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Madoz JR et al. Inhibition of the type I interferon response in human dendritic cells by dengue virus infection requires a catalytically active NS2B3 complex. J. Virol 84, 9760–9774 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munoz-Jordan JL et al. Inhibition of alpha/beta interferon signaling by the NS4B protein of flaviviruses. J. Virol 79, 8004–8013 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Sesma A. et al. Influenza virus evades innate and adaptive immunity via the NS1 protein. J. Virol 80, 6295–6304 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai P. et al. Modified vaccinia virus Ankara triggers type I IFN production in murine conventional dendritic cells via a cGAS/STING-mediated cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1003989 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong B. et al. The adaptor protein MITA links virus sensing receptors to IRF3 transcription factor activation. Immunity 29, 538–550 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao D. et al. Cyclic GMP–AMP synthase is an innate immune sensor of HIV and other retroviruses. Science 341, 903–906 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Civril F. et al. Structural mechanism of cytosolic DNA sensing by cGAS. Nature 498, 332–337 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li XD et al. Pivotal roles of cGAS–cGAMP signaling in antiviral defense and immune adjuvant effects. Science 341, 1390–1394 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J. et al. Functional profiling of recombinant NS3 proteases from all four serotypes of dengue virus using tetrapeptide and octapeptide substrate libraries. J. Biol. Chem 280, 28766–28774 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heaton NS & Randall G. Dengue virus-induced autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Cell Host Microbe 8, 422–432 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stroikin Y, Dalen H, Loof S & Terman A. Inhibition of autophagy with 3-methyladenine results in impaired turnover of lysosomes and accumulation of lipofuscin-like material. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 83, 583–590 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kranzusch PJ, Lee AS, Berger JM & Doudna JA Structure of human cGAS reveals a conserved family of second-messenger enzymes in innate immunity. Cell Rep. 3, 1362–1368 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan YK & Gack MU A phosphomimetic-based mechanism of dengue virus to antagonize innate immunity. Nat. Immunol 17, 523–530 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoggins J. Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature 505, 691–695 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Catteau A, Roue G, Yuste VJ, Susin SA & Despres P. Expression of dengue ApoptoM sequence results in disruption of mitochondrial potential and caspase activation. Biochimie 85, 789–793 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Bacha T. et al. Mitochondrial and bioenergetic dysfunction in human hepatic cells infected with dengue 2 virus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1772, 1158–1166 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nasirudeen AM, Wang L & Liu DX Induction of p53-dependent and mitochondria-mediated cell death pathway by dengue virus infection of human and animal cells. Microbes Infect. 10, 1124–1132 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam E, Stein S & Falck-Pedersen E. Adenovirus detection by the cGAS/STING/TBK1 DNA sensing cascade. J. Virol 88, 974–981 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartlova A. et al. DNA damage primes the type I interferon system via the cytosolic DNA sensor STING to promote anti-microbial innate immunity. Immunity 42, 332–343 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.West AP et al. Mitochondrial DNA stress primes the antiviral innate immune response. Nature 520, 553–557 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoggins JW et al. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 472, 481–485 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rowland AA & Voeltz GK Endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria contacts: function of the junction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 607–625 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu CY et al. Dengue virus impairs mitochondrial fusion by cleaving mitofusins. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005350 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ablasser A. et al. Cell intrinsic immunity spreads to bystander cells via the intercellular transfer of cGAMP. Nature 503, 530–534 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diamond MS et al. Modulation of dengue virus infection in human cells by alpha, beta, and gamma interferons. J. Virol 74, 4957–4966 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diamond MS, Edgil D, Roberts TG, Lu B & Harris E. Infection of human cells by dengue virus is modulated by different cell types and viral strains. J. Virol 74, 7814–7823 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gebhard LG et al. A proline-rich N-terminal region of the dengue virus NS3 is crucial for infectious particle production. J. Virol 90, 5451–5461 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanchez-Aparicio MT, Ayllon J, Leo-Macias A, Wolff T & Garcia-Sastre A. Subcellular localizations of RIG-I, TRIM25, and MAVS complexes. J. Virol 91, e01155–16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrow J. et al. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for the ENCODE project. Genome Res. 22, 1760–1774 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaisson MJ & Tesler G. Mapping single molecule sequencing reads using basic local alignment with successive refinement (BLASR): application and theory. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 238 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jayaprakash AD et al. Stable heteroplasmy at the single-cell level is facilitated by intercellular exchange of mtDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 2177–2187 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Complete blots for all the figures and corresponding molecular weight markers are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6.