Abstract

Although the outcomes of viral infectious diseases are remarkably varied, most infections cause acute diseases after a short period. Novel coronavirus disease 2019, which recently spread worldwide, is no exception. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are small circulating membrane-enclosed entities shed from the cell surface in response to cell activation or apoptosis. EVs transport various kinds of bioactive molecules between cells, including functional RNAs, such as viral RNAs and proteins. Therefore, when EVs are at high levels, changes in cell activation, inflammation, angioplasty and transportation suggest that EVs are associated with various diseases. Clinical research on EVs includes studies on the coagulatory system. In particular, abnormal enhancement of the coagulatory system through EVs can cause thrombosis. In this review, we address the functions of EVs, thrombosis, and their involvement in viral infection.

Keywords: viral infection, thrombosis, extracellular vesicle, exosome, microvesicle

Introduction

Most viruses are small sized (typically 0.02 to 0.3 μm), unlike large and mega-viruses whose maximum lengths can reach 1 μm in length at the maximum.1–3 The reproduction of a virus depends on bacterial, plant, and animal cells including those in humans.4 Viruses are classified according to genomic properties and structures as well as their reproduction method, and not according to the disease that each virus causes.5 Replication in DNA viruses typically occurs in the nucleus of the host cell, whereas RNA virus replication typically occurs in the cytoplasm.5,6 There are exceptions, however. For example, H1N1 (an RNA virus) cannot reproduce in the host’s cytoplasm, whereas vaccinia (a DNA virus) does not need the nucleus to reproduce. After reproduction of a complete virus particle, the host cell typically perishes and the virus is released to infect other host cells.4–6 Although the outcomes of viral infectious diseases are remarkably varied, most infections cause acute disease after a short period.7 Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which recently spread worldwide, is no exception.8,9

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are small circulating membrane-enclosed entities shed from cell surface in response to cell activation or apoptosis.10 Although detailed understanding of EVs is lacking, information about EVs has been accumulating.11–13 EVs measure 0.01-4 μm and are generated by various processes.11,12 EVs transport various types of molecules between cells, such as viral RNAs and proteins.14–16 Therefore, when EVs are at high levels, cell activation, inflammation, angioplasty and states involving transportation occur, indicating the association of EVs with various diseases.11,14,17–19 Clinical research of EVs includes studies on the coagulatory system. In particular, abnormal enhancement of the coagulatory system by EVs can cause thrombosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Such an abnormality after a viral infectious disease can become a significant clinical problem. In this review, we address the functions of EVs, thrombosis, and their involvement in viral infection.

Classification of EVs

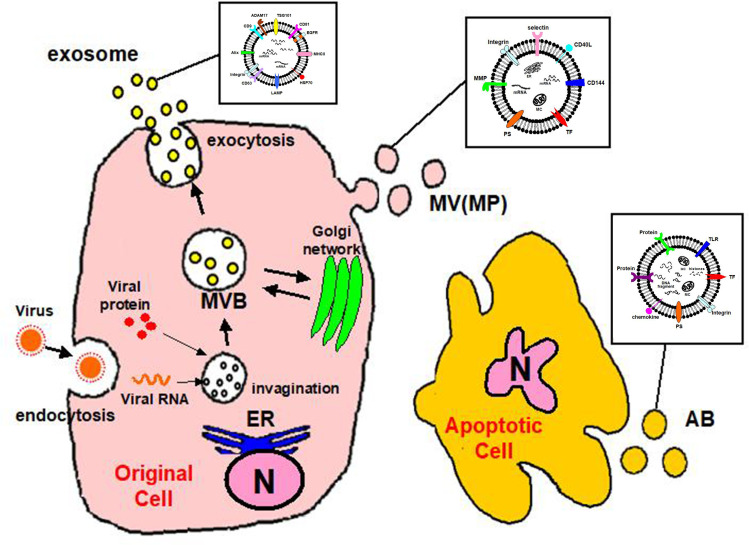

EVs are classified into three groups by size, namely exosomes, microvesicles (MVs), and apoptotic bodies (ABs) (Table 1).11 Exosomes are EVs with diameters of 30–200 nm, and these membrane-bound vesicles can be precipitated by ultracentrifugation at 100,000×g.11,12,15,20 Most exosomes carry specific proteins reflecting the characteristics of the origin cell.21–23 They form through multi-vesicular bodies (MVBs) that fuse with the cell membrane for release.15,24,25 Exosomes are released from a cell via a mechanism of endosomal complexes required for transport (Figure 1).26

Table 1.

Population and Characteristics of EVs

| Exosome | MV (MP) | AB | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | 30–200 nm | 100–1000 nm | 1000–3000 nm |

| Shape | Homogeneous | Variable | Variable |

| Origine | MBV fusion with the plasma membrane | Budding from the plasma membrane | Budding from the plasma membrane |

| Markers | Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) Alix, TSG101, HSP70 | Annexin V, Integrin, Selectin, CD40 ligand, metalloproteinase | Annexin V, DNA fragment Caspase 3, Histones |

| Isolation | Ultracentrifugation (100,000g) | Ultracentrifugation (10,000–100,000g) | Ultracentrifugation (6000–10,000g) |

| P-Act | Weak | Powerful | Powerful |

Notes: Data from Nomura.11 All vesicles preparations are heterogeneous with different protocols allowing the enrichment of one type over another.

Abbreviations: MV, microvesicle; MP, microparticle; AB, apoptotic body; MBV, multivesicular body; TSG101, tumor susceptibility gene 101; HSP70, heat shock protein 70; P-Act, procoagulant activity.

Figure 1.

Convergence of EV and virus biogenesis. Original cell owns the endocytic and secretory pathways. Viruses share effectors of EV production for their assembly and release. Exosomes produced in the MVB and shed MV (MP) budding of the plasma membrane. Apoptotic cell finally releases shedding AB.

Abbreviations: MV, microvesicle; MP, microparticle; AB, apoptotic body; N, nucleus; MBV, multivesicular body; ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

MVs are EVs of 10–1000 nm in size.11 MVs are also called microparticles (MPs).10,11,27 The differences between MVs and exosomes other than their size are the processes of formation and secretion.15,28 MVs are generated by the surface of the cell breaking off, which is controlled by cell activation.29 The plasma membrane includes several kinds of phospholipids.11,30 The internal leaflet contains aminophosphatides (eg, phosphatidylserine:PS) for a negative charge.30 MV biogenesis, which occurs via blebbing, is a fragmentation phenomenon whereby nascent MVs are released into the extracellular space via pinching off from the plasma membrane.31,32 MVs contain distinct protein and lipid components from the plasma membrane.32 During cell activation, the charge of the leaflet changes the structure of the normal lipid layer, and PS is exposed to MV (Figure 1).33 This leads to procoagulant activity in the MVs.34

EVs generated by apoptosis are called apoptotic bodies (ABs).11,35,36 During its final phase of apoptotic death, the cell divides into several Ab,32 the size of which are 1000–3000 nm.37,38 Similar to MVs, ABs are formed by PS moving to the cell surface.33–35 ABs may contain a wide variety of cellular components, such as micronuclei, chromatin remnants, cytosol portions, degraded proteins, DNA fragments, and even intact organelles.32 The main difference between ABs and MVs is the existence of materials derived from the nucleus such as histones and DNA fragments (Figure 1).39,40

Function of EVs

EVs can carry activated coagulation factors, by expressing phosphatides on their surface.11 Therefore, it is thought that the existence of EVs is related to several diseases, indicating a coagulatory promotion tendency.11,27 Because EVs promote intravascular coagulation to support thrombin generation, they may be linked with coagulation abnormalities.27 The procoagulant activity observed on platelet-derived EV surfaces is 50 to 100-fold higher than that observed on activated platelets.41 This suggests that the coagulatory promotion by EVs is an important defense mechanism for bleeding risk.11 EVs also carry tissue factor (TF) that is important to activate the coagulation system.42

The main characteristics of atherosclerosis are the adhesion of monocytes to the endothelium and movement of monocytes into the subendothelium.27 When a monocyte is activated by platelet-derived EVs and adheres to the endothelium, several inflammatory cytokines are generated.43 Furthermore, stimulation or activation of the endothelium by EVs increases the expression of adhesion molecules on the endothelial surface.43,44 Atherosclerotic lesions can develop and progress in severity via the apoptosis of endothelial cells, a process induced by a substantial number of EV-dependent coagulatory factors.11,27,45

EV appear to constitute a new system of cell-cell communication.16,46,47 EVs have various important functions such as coagulatory promotion, immunosuppression, and angioplasty.48,49 EVs may be the most suitable mechanism through which cells communicate with others.15,48 For example, EVs produced by one kind of cell stimulate another specific cell.50,51 EVs carry tetraspanin protein and may employ a mechanism that can return in a specific organization.52,53 Another mechanism involves fusion with the cell membrane, which results in the transfer of mRNA, micro(mi)RNA, proteins, and signaling molecules by EVs.54,55 The existence of miRNAs has been found in EVs released with biological fluid of patients with various viral infectious diseases.13,56–58 EVs might play a crucial role in dissemination of pathogens as well as host-derived molecules during infection.58 Therefore, EVs may be strongly involved in progression of the post-viral condition and the origin of complications.59

Viral Infection and Thrombosis

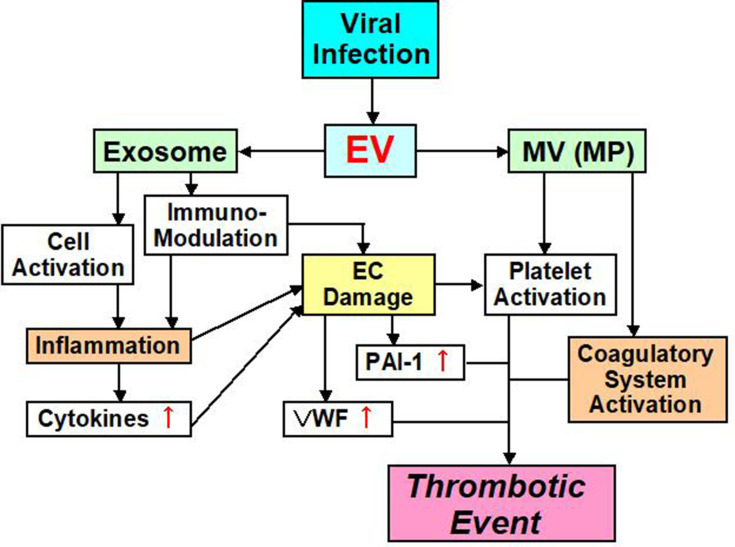

Ebola, H1N1 influenza, cytomegalovirus, chickenpox – herpes zoster, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), coxsackie virus B3, herpes simplex virus-1, dengue, and Junin virus are accompanied by thrombotic complications and bleeding.60–71 There are at least two major factors underlying the onset of thrombosis that are associated with these viral infections (Figure 2).72,73 One factor influencing the blood vessel system is the viruses themselves, because they can influence monocytes, neutrophils and the blood vessel endothelium and also induce the expression of TF.74 Some viruses can also directly influence platelets and enhance PS expression during their infections.75–77 Plasma from influenza patients may also contain MVs with TF activity.78 This leads to strong thrombosis onset, by enhancing the activity of the exogenous coagulatory system. The second mechanism influences the immune system. The viral infection influences the immune system, and inflammation with the cell which immunity decreased spreads, and an imbalance between coagulation and anti-coagulation occurs.79 This mechanism is related to interactions between the virus and Toll-like receptors (TLRs).70,79

Figure 2.

EV mediated thrombotic event pathway.

Abbreviations: EV, extracellular vesicle; MV, microvesicle; MP, microparticle; EC, endothelial cell; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; VWF, von Willebrand factor.

Ebola Virus (EBOV)

EBOV is a negative-sense RNA virus that causes a severe disease characterized by high fever, diarrhea, and unexpected onset of vomiting.80 Additionally, this virus causes a serious procoagulatory abnormality with liver damage.80 EBOV infection induces TF expression in infected cells and serum D-dimer rises, finally causing DIC.81 EBOV disrupts the functions of dendritic cells coordinating a T cell increase.82,83 Therefore, it is thought that EBOV infectious disease develops a thrombotic tendency by failure of the immune system and enhancement of coagulation.70,84

Influenza A Virus (IAV)

Influenza A virus (IAV) is a negative-sense RNA virus that commonly causes death.85 Cardiovascular system disorders, such as acute myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, are observed.86–90 Disorder of the blood vessel wall barrier by IAV may contribute to the development of pulmonary damage in patients with influenza.91,92 H5N1-infected chickens show microthrombosis and thrombocytopenia.93 IAV infectious disease causes a high level of plasma von Willebrand factor (vWF) and a decrease of a disintegrin-like and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motifs 13 (ADAMTS13), which may result in clot-related microangiopathy.94,95 Therefore, IAV infectious disease is thought to cause immunity and aggravation of the wall system, which results in inflammatory induction and coagulatory enhancement.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a positive-sense single-stranded enveloped RNA virus of the Retroviridae family.96 One cause of death in HIV-infected patients is cardiovascular disease (CVD), and functional disorder in the blood walls caused by HIV reproduction is a considerable determinant of it.96–98 Additionally, the immune reaction and inflammation caused by HIV infection may be cardiovascular risks.99,100 The death rate is strongly related to interleukin (IL)-6, high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), and D-dimer. In particular, IL-6 and hsCRP are related to the development of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.101,102 Funderburg et al103,104 reported that TF expression on the surface of monocytes increases in HIV patients. Additionally, Harley et al105 reported that T-cell kinetics and activity of the thrombin-PAR1 signaling axis are increased by proinflammatory cytokines during HIV infection and contribute to adaptive immunoreactions. Furthermore, young patients with HIV infection have a high level of vWF and a low level of ADAMTS13, which are related to stroke.106 Therefore, HIV infection has a thrombotic risk through various mechanisms.107,108

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family. HCV infection carry the risk of thrombosis, which increases with expression of TF, fibrinolysis interference, and increased platelet aggregation and activation.109 HCV viral RNA activates TLR-3 in endothelial cells (ECs), leading to inflammation and expression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α.110 Damaged ECs can affect immune cells through CXCL12 chemokine expression.111 Through these mechanisms, increased TNF-α induces expression of TF and downregulation of thrombomodulin (TM).112 Hodowanec et al113 confirmed that elevation of TF expression and enhancement of coagulatory activity increase in some chronic HCV patients. Similarly, during chronic HCV infectious disease, wall functional disorder caused by plasma vWF levels increases.114

Coxsackievirus (CoxV)

Coxsackievirus (CoxV) is negative-sense RNA virus of the Picornaviridae family.70 It is accompanied by a considerable risk of thromboembolism caused by myocarditis.115 Additionally, myocarditis coagulopathy and hepatic necrosis occur, and ventricular clot formation increases significantly because of platelet activation.116

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is double-stranded, linear DNA genome virus of the herpesvirus family.70 Infection of blood vessel ECs by HSV increases TF activity and reduces TM expression.69,117 Sutherland et al118 reported that HSV type 1 (HSV-1) is a cofactor for PAR-1 that induces TF and glycoprotein C, causing thrombin production. HSV-1 and HSV-2 move FX to the cell surface via internal mechanism phosphatides.117–119 It is thought that these viruses drive thrombin generation on the cell surface via this mechanism.117

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) belongs to the herpesvirus family and has double-stranded DNA. Its name was changed to human herpesvirus type 4 (HHV-4), but the former name is still widely used.70 EBV triggers autoantibody-producing autoimmunity in response to various autoimmune diseases.120 Patients with EBV experience portal vein thrombosis caused by hypercoagulable syndrome.121

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) has double-stranded DNA with the generic name of herpesvirus characterized by forming a characteristic inclusion body of the observable “eyes of the owl” state in the nucleus of the host cell under an optical microscope. CMV transforms monocytes and induces production of inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, the incidence of thrombosis in patients with acute CMV infection is common.121,122

Corona Virus (CoV)

Corona virus (CoV) causes disease in mammals and birds, and has a single strand plus chain RNA genome.123 In 2003, a CoV epidemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome CoV (SARS-CoV-1) emerged in China.124 SARS-CoV-1 was associated with severe thrombotic complications.124 Several SARS-CoV-1 cases exhibited pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis.125 The characteristics of SARS-CoV-1 are a prolonged prothrombin time, prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time, elevated D-dimer, and worsening thrombocytopenia.126 These findings are consistent with DIC. Furthermore, interestingly, thrombopoietin levels increase in SARS-CoV-1 patients at the convalescent phase compared with normal controls.127 These findings have also been reported in patients with septic DIC.128

Another CoV infection was reported in 2012.129 This CoV was responsible for “Middle East respiratory syndrome” (MERS-CoV).129 MARS-CoV is similar to SARS-CoV-1 and associated with thrombotic complications. Specifically, DIC is one of the major complications reported in fatal MERS-CoV cases.130

In 2019, another CoV caused a global pandemic. CoV disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a novel CoV strain disease.8,9 COVID-19 patients suffer from severe respiratory or systemic manifestations. Therefore, COVID-19 is also called SARS-CoV-2.131 Thrombotic complications also emerge in patients with COVID-19.132–135 COVID-19 patients have elevated D-dimer levels, prolonged prothrombin times, and thrombocytopenia similar to DIC.132,136–138 Both elevated D-dimer levels and thrombocytopenia can be explained by excessive activation of platelets and the coagulation cascade. In contrast, phagocytosis or direct viral targeting by the immune system can also cause these abnormal clinical findings. Thus, viral infections elicit systemic inflammatory immune responses resulting in imbalanced coagulation.70

EVs and Coagulatory Abnormalities During Viral Infection

EVs from a virally infected cell include not only the virus, but also information on the host.139 Therefore, EVs are involved in interactions between a virus and various cells of the host. As we have mentioned, the function and role of EVs are varied.15,27,46,47 Most importantly, EVs that participate in post-viral coagulatory abnormalities may be MVs (or MPs), because it appears that most characteristic functions of MVs promote coagulation depending on TF (Figure 2). In addition, MVs can substantially increase procoagulant activity on platelet surfaces, thereby contributing to coagulant abnormality during viral infection.11,41 In contrast, exosomes contain many functional features, one of which concerns the immune system (Figure 2).56,139–142 For example, lymphatic exosomes promote dendritic cell migration along guidance cues, thereby regulating the immune system.142 Therefore, it is possible that exosomes do not influence the coagulatory system.

EVs are involved in some aspects of viral infectious disease.143 After infection, for example, EBOV packages the protein moiety characteristic of this virus in EVs. Apoptosis of immune cells in the host is guided by inflammatory cytokines.144 This drives failure of the homeostasis mechanism in blood vessels, leading to coagulatory abnormalities such as vein clots and DIC. Airway epithelial cells release EVs that neutralize human influenza virus.145 This mechanism of EVs might play an important role in defense against respiratory viruses.146 EVs after HIV infection have a significant influence on the immune system.147–149 CMV-related EVs are useful to reinforce infectivity of CMV.143,150 Human CMV infection is controlled by T cell-mediated immunity and CMV infects ECs.151,152 One of the functions of EC-derived EVs after CMV infection might be contributing to innate surveillance.151

One role played by post-viral EVs exosomes is their participation in maintaining the pathological state and promoting the spread of viral infection. The main roles of MVs and MPs appear to be in coagulation abnormality.59,153–161 Regarding COVID-19, reports involving EVs are still rare.162–165 However, a similar role of exosomes and MVs is assumed in COVID-19 as other virus infectious diseases.166–170 In particular, concerning thrombosis, there is no doubt that COVID-19 causes more symptoms in comparison with the past virus infectious disease.171 Accumulation of important reports of EVs in conjunction with COVID-19 is expected in the future.

Conclusions

We have addressed the functions of EVs in thrombosis, and their involvement in viral infections. Clinical research on EVs should include studies on the coagulatory system. In particular, abnormal enhancement of the coagulatory system by EVs can cause thrombosis and DIC (Figure 2). There are reports about EVs in some virus infectious diseases. Apoptosis of immune cells in the host is guided by inflammatory cytokines. As a role of post-viral EVs, exosomes participate in pathological maintenance and infection spreading. The main roles of MVs appear to be in coagulation abnormalities. Although many viral infections involve EVs, the role of EVs in COVID-19 is unclear. Nevertheless, thrombosis is a major problem that affects the prognosis of COVID-19 patients. Accumulation of important reports of EVs in conjunction with COVID-19 is expected in the future.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported in part by grants (15K08657 and 19K07948 to S.N.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science and Technology of Japan. We thank Edanz Group for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this study.

References

- 1.La Scola B, Audic S, Robert C, et al. A giant virus in amoebae. Science. 2003;299(5615):2033. doi: 10.1126/science.1081867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iyer LM, Balaji S, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Evolutionary genomics of nucleo – cytoplasmic large DNA viruses. Virus Res. 2006;117(1):156–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koonin EV, Yutin N. Evolution of the large nucleocytoplasmic DNA viruses of eukaryotes and convergent origins of viral gigantism. Adv Virus Res. 2019;103:167–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali H, Ali AA, Atta MS, Cepica A. Common, emerging, vector-bone and infrequent abortgenic virus infections of cattle. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2012;59(1):11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poirier EZ, Vignuzzi M. Virus population dynamics during infection. Curr Opin Virol. 2017;23:82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan B, Gao SJ. RNA epitranscriptomics: regulation of infection of RNA and DNA viruses by N6- methyladenosine (M6A). Rev Med Virol. 2018;28(4):e1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayo MA, Pringle CR. Virus taxonomy – 1997. J Gen Virol. 1998;79(Pt 4):649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Liu Q, Guo D. Emerging coronaviruses: genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(4):418–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nomura S, Ozaki Y, Ikeda Y. Function and role of microparticles in various clinical settings. Thromb Res. 2008;123(1):8–23. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nomura S. Extracellular vesicles and blood diseases. Int J Hematol. 2017;105(4):392–405. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2180-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raposo G, Stoovogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200(4):373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciardiello C, Cavallini L, Spinelli C, et al. Focus on extracellular vesicles: new frontiers of cell-to-cell communication in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(2):175–191. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thery C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(8):581–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoen EN, Cremer T, Gallo RC, Margolis LB. Extracellular vesicles and viruses: are they close relatives? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(33):9155–9161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang ME, Leonard JN. A platform for actively loading cargo RNA to elucidate limiting steps in EV-mediated delivery. J Extracell Vesicles. 2016;5:31027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iraci N, Leonardi T, Gessler F, Vega B, Pluchino S. Focus on extracellular vesicles: physiological role and signalling properties of extracellular membrane vesicles. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(2):171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberro A, Sáenz-Cuesta M, Muñoz-Culla M, et al. Inflammaging and frailty status do not result in an increased extracellular vesicle concentration in circulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(7):1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conde-Vancells J, Rodriguez-Suarez E, Embade N, et al. Characterization and comprehensive proteome profiling of exosomes secreted by hepatocytes. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(12):5157–5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ. Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J Proteomics. 2010;73(10):1907–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Yin H, Betts C, Lakhal S, Wood MJ. Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(4):341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baietti MF, Zhang Z, Mortier E, et al. Syndecan-synternin-ALIX regulates the biogenesis of exosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(7):677–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.György B, Szabó TG, Pásztói M, et al. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(16):2667–2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muhsin-Sharafaldine MR, Saunderson SC, Dunn AC, Faed JM, McLellan AD. Procoagulant and immunogenic properties of melanoma exosomes, microvesicles and apoptotic vesicles. Oncotarget. 2016;7(35):56279–56294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colombo M, Moita C, van Niel G, et al. Analysis of ESCRT functions in exosome biogenesis, composition and secretion highlights the heterogeneity of extracellular vesicles. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 24):5553–5565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nomura S. Microparticle and atherothrombotic diseases. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23(1):1–9. doi: 10.5551/jat.32326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jayachandran M, Miller VM, Heit JA, Owen WG. Methodology for isolation, identification and characterization of microvesicles in peripheral blood. J Immunol Methods. 2012;375(1–2):207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabatier F, Camoin-Jau L, Anfosso F, Sampol J, Dignat-George F. Circulating endothelial cells, microparticles and progenitors: key players towards the definition of vascular competence. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(3):454–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angelillo-Scherrer A. Leukocyte-derived microparticles in vascular homeostasis. Circ Res. 2012;110(2):356–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tricarico C, Clancy J, D’Souza-Schorey C. Biology and biogenesis of shed microvesicles. Small GTPases. 2017;8(4):220–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Battistelli M, Falcieri E. Apoptotic bodies: particular extracellular vesicles involved in intercellular communication. Biology (Basel). 2020;9(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leventis PA, Grinstein S. The distribution and function of phosphatidylserine in cellular membranes. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:407–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplan ZS, Jackson SP. The role of platelets in atherothrombosis. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akers JC, Gonda D, Kim R, Carter BS, Chen CC. Biogenesis of extracellular vesicles (EV): exosomes, microvesicles, retrovirus-like vesicles, and apoptotic bodies. J Neurooncol. 2013;113(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Black LV, Saunderson SC, Coutinho FP, et al. The CD169 sialoadhesin molecule mediates cytotoxic T-cell responses to tumour apoptotic vesicles. Immunol Cell Biol. 2015;94(5):430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thery C, Boussac M, Véron P, et al. Proteomic analysis of dendritic cell-derived exosomes: a secreted subcellular compartment distinct from apoptotic vesicles. J Immunol. 2001;166(12):7309–7318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bilyy RO, Shkandina T, Tomin A, et al. Macrophages discriminate glycosylation patterns of apoptotic cell-derived microparticles. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(1):496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hristov M, Erl W, Linder S, Weber PC. Apoptotic bodies from endothelial cells enhance the number and initiate the differentiation of human endothelial progenitor cells in vitro. Blood. 2004;104(9):2761–2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turiak L, Misjak P, Szabo TG, et al. Proteomic characterization of thymocyte-derived microvesicles and apoptotic bodies in BALB/C mice. J Proteome. 2011;74(10):2025–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sinauridze EI, Kireev DA, Popenko NY, et al. Platelet microparticle membranes have 50- to 100-fold higher specific procoagulant activity than activated platelets. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97(3):425–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolberg AS, Monroe DM, Roberts HR, Hoffman MR. Tissue factor de-encryption: ionophore treatment induces changes in tissue factor activity by phosphatidylserine-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1999;10(4):201–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nomura S, Tandon NN, Nakamura T, Cone J, Kambayashi J. High-shear-stress-induced activation of platelets and microparticles enhances expression of cell adhesion molecules in THP-1 and endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2001;158(2):277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barry OP, Praticò D, Savani RC, FitzGerald GA. Modulation of monocyte-endothelial cell interactions by platelet microparticles. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(1):136–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mallat Z, Hugel B, Ohan J, Lesèche G, Freyssinet JM, Tedgui A. Shed membrane microparticles with procoagulant potential in human atherosclerotic plaques: a role for apoptosis in plaque thrombogenicity. Circulation. 1999;99(3):348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colombo M, Raposo G, Théry C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Nedawi K, Meehan B, Micallef J, et al. Intercellular transfer of the oncogenic receptor EGFRvIII by microvesicles derived from tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(5):619–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hood JL, San RS, Wickline SA. Exosomes released by melanoma cells prepare sentinel lymph nodes for tumor metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71(11):3792–3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tomasoni S, Longaretti L, Rota C, et al. Transfer of growth factor receptor mRNA via exosomes unravels the regenerative effect of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(5):772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borges FT, Reis LA, Schor N. Extracellular vesicles: structure, function, and potential clinical uses in renal diseases. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46(10):824–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen TS, Lai RC, Lee MM, Choo AB, Lee CN, Lim SK. Mesenchymal stem cell secretes microparticles enriched in pre-microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(1):215–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mathivanan S, Simpson RJ. ExoCarta: a compendium of exosomal proteins and RNA. Proteomics. 2009;9(21):4997–5000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hemler ME. Tetraspanin proteins mediate cellular penetration, invasion, and fusion events and define a novel type of membrane microdomain. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:397–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tian T, Wang Y, Wang H, Zhu Z, Xiao Z. Visualizing of the cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of exosomes by live-cell microscopy. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111(2):488–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janas T, Janas MM, Sapon K, Janas T. Mechanisms of RNA loading into exosomes. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(13):1391–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kosaka N, Yoshioka Y, Hagiwara K, Tominaga N, Katsuda T, Ochiya T. Trash or treasure: extracellular microRNAs and cell-to-cell communication. Front Genet. 2013;4:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schorey JS, Cheng Y, Singh PP, Smith VL. Exosomes and other extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(1):24–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alenquer M, Amorim MJ. Exosome biogenesis, regulation, and function in viral infection. Viruses. 2015;7(9):5066–5083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller HC, Stephan M. Hemorrhagic varicella: a case report and review of the complications of varicella in children. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11(6):633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uthman IW, Gharavi AE. Viral infections and antiphospholipid antibodies. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;31(4):256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Geisbert TW, Jahrling PB. Exotic emerging viral diseases: progress and challenges. Nat Med. 2004;10(12 Suppl):S110–S121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Squizzato A, Gerdes VE, Buller HR. Effects of human cytomegalovirus infection on the coagulation system. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93(3):403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang CC, Chang CT, Lin CL, Lin IC, Kao CH. Hepatitis C virus infection associated with an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis: a population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(38):e1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bunce PE, High SM, Nadjafi M, Stanley K, Liles WC, Christian MD. Pandemic H1N1 influenza infection and vascular thrombosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(2):e14–e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kiser KL, Badowski ME. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(12):1292–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matta F, Yaekoub AY, Stein D. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and risk of venous thromboembolism. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336(5):402–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kishimoto C, Ochiai H, Sasayama S. Intracardiac thrombus in murine Coxsackievirus B3 myocarditis. Heart Vessels. 1992;7(2):76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Friedman MG, Phillip M, Dagan R. Virus-specific IgA in serum, saliva, and tears of children with measles. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;75(1):58–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hidaka Y, Sakai Y, Toh Y, Mori R. Glycoprotein C of herpes simplex virus type 1 is essential for the virus to evade antibody-independent complement-mediated virus inactivation and lysis of virus-infected cells. J Gen Virol. 1991;72(Pt 4):915–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Key NS, Bach RR, Vercellotti GM, Moldow CF. Herpes simplex virus type I does not require productive infection to induce tissue factor in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Lab Invest. 1993;68(6):645–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Subeamaniam S, Scharrer I. Procoagulant activity during viral infections. Front Biosci. 2018;23:1060–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yu Y, Shen Y, Li J, et al. Viral infection related venous thromboembolism: potential mechanism and therapeutic targets. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(3):1257–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van Gorp EC, Suharti C, Ten Cate H, et al. Review: infectious diseases and coagulation disorders. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(1):176–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koupenova M, Vitseva O, Mackay CR, et al. Platelet-TLR7 mediates host survival and platelet count during viral infection in the absence of platelet-dependent thrombosis. Blood. 2014;124(5):791–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Campbell RA, Schwertz H, Hottz ED, et al. Human megakaryocytes possess intrinsic antiviral immunity through regulated induction of IFITM3. Blood. 2019;133(19):2013–2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koupenova M, Corkrey HA, Visteva O, et al. The role of platelet in mediating a response to human influenza infection. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rondina M, Tatsumi K, Bastarache JA, Mackman N. Microvesicle tissue factor activity and interleukin-8 levels are associated with mortality in patients with influenza A/H1N1 infection. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):e574–e578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van der Poll T, Levi M. Crosstalk between inflammation and coagulation: the lessons of sepsis. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2012;10(5):632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leroy EM, Baize S, Volchkov VE, et al. Human asymptomatic Ebola infection and strong inflammatory response. Lancet. 2000;355(9222):2210–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mohamadzadeh M, Chen L, Schmaljohn AL. How Ebola and Marburg viruses battle the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(7):556–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wong G, Kobinger GP, Qiu X. Characterization of host immune responses in Ebola virus infections. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10(6):781–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mahanty S, Bray M. Pathogenesis of filoviral haemorrhagic fevers. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4(8):487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Antoniak S. The coagulation system in host defense. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2018;2(3):549–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Short KR, Veldhuis Kroeze EJB, Reperant LA, Richard M, Kuiken T. Influenza virus and endothelial cells: a species specific relationship. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barnes M, Heywood AE, Mahimbo A, Rahman B, Newall AT, Macintyre CR. Acute myocardial infarction and influenza: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Heart. 2015;101(21):1738–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Corrales-Medina VF, Madjid M, Musher DM. Role of acute infection in triggering acute coronary syndromes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(2):83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ludwig A, Lucero-Obusan C, Schirmer P, Winston C, Holodniy M. Acute cardiac injury events </=30 days after laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infection among U.S. veterans, 2010–2012. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marsden PA. Inflammation and coagulation in the cardiovascular system: the contribution of influenza. Circ Res. 2006;99(11):1152–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rothberg MB, Haessler SD, Brown RB. Complications of viral influenza. Am J Med. 2008;121(4):258–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Armstrong SM, Darwish I, Lee WL. Endothelial activation and dysfunction in the pathogenesis of influenza A virus infection. Virulence. 2013;4(6):537–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Feng Y, Hu L, Lu S, et al. Molecular pathology analyses of two fatal human infections of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68(1):57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Muramoto Y, Ozaki H, Takada A, et al. Highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus causes coagulopathy in chickens. Microbiol Immunol. 2006;50(1):73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Akiyama R, Komori I, Hiramoto R, Isonishi A, Matsumoto M, Fujimura Y. H1N1 influenza (Swine flu)-associated thrombotic microangiopathy with a markedly high plasma ratio of von Willebrand factor to ADAMTS13. Intern Med. 2011;50(6):643–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tsujii N, Nogami K, Yoshizawa H, et al. Influenza-associated thrombotic microangiopathy with unbalanced von Willebrand factor and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13 levels in a heterozygous protein S-deficient boy. Pediatr Int. 2016;58(9):926–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Blum A, Hadas V, Burke M, Yust I, Kessler A. Viral load of the human immunodeficiency virus could be an independent risk factor for endothelial dysfunction. Clin Cardiol. 2005;28(3):149–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Baker JV, Duprez D. Biomarkers and HIV-associated cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5(6):511–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Palella FJ Jr., Phair JP. Cardiovascular disease in HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6(4):266–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shen YM, Frenkel EP. Thrombosis and a hypercoagulable state in HIV-infected patients. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2004;10(3):277–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.O’Brien MP, Zafar MU, Rodriguez JC, et al. Targeting thrombogenicity and inflammation in chronic HIV infection. Sci Adv. 2019;5(6):eaav5463. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav5463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, et al. Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS Med. 2008;5(10):e203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rodger AJ, Fox Z, Lundgren JD, et al. Activation and coagulation biomarkers are independent predictors of the development of opportunistic disease in patients with HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(6):973–983. doi: 10.1086/605447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Funderburg NT, Mayne E, Sieg SF, et al. Increased tissue factor expression on circulating monocytes in chronic HIV infection: relationship to in vivo coagulation and immune activation. Blood. 2010;115(2):161–167. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Funderburg NT, Zidar DA, Shive C, et al. Shared monocyte subset phenotypes in HIV-1 infection and in uninfected subjects with acute coronary syndrome. Blood. 2012;120(23):4599–4608. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-433946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hurley A, Smith M, Karpova T, et al. Enhanced effector function of CD8(+) T cells from healthy controls and HIV-infected patients occurs through thrombin activation of protease-activated receptor 1. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(4):638–650. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Allie S, Stanley A, Bryer A, Meiring M, Combrinck MI. High levels of von Willebrand factor and low levels of its cleaving protease, ADAMTS13, are associated with stroke in young HIV-infected patients. Int J Stroke. 2015;10(8):1294–1296. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ellwanger JH, Veit TD, Chies JAB. Exosomes in HIV infection: a review and critical look. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;53:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Welch JL, Stapleton JT, Okeoma CM. Vehicles of intercellular communication: exosomes and HIV-1. J Gen Virol. 2019;100(3):350–366. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gonzalez-Reimers E, Quintero-Platt G, Martin-Gonzalez C, Perez-Hernandez O, Romero-Acevedo L, Santolaria-Fernandez F. Thrombin activation and liver inflammation in advanced hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(18):4427–4437. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i18.4427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pircher J, Czermak T, Merkle M, et al. Hepatitis C virus induced endothelial inflammatory response depends on the functional expression of TNFalpha receptor subtype 2. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e113351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wald O, Pappo O, Safadi R, et al. Involvement of the CXCL12/CXCR4 pathway in the advanced liver disease that is associated with hepatitis C virus or hepatitis B virus. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(4):1164–1174. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Falasca K, Mancino P, Ucciferri C, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and S-100b protein in patients with hepatitis C infection and cryoglobulinemias. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30(5):E167–E176. doi: 10.25011/cim.v30i5.2892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hodowanec AC, Lee RD, Brady KE, et al. A matched cross-sectional study of the association between circulating tissue factor activity, immune activation and advanced liver fibrosis in hepatitis C infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:190. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0920-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Barone M, Viggiani MT, Amoruso A, et al. Endothelial dysfunction correlates with liver fibrosis in chronic HCV infection. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:682174. doi: 10.1155/2015/682174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lee CJ, Huang YC, Yang S, et al. Clinical features of coxsackievirus A4, B3 and B4 infections in children. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Antoniak S, Mackman N. Coagulation, protease-activated receptors, and viral myocarditis. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2014;7(2):203–211. doi: 10.1007/s12265-013-9515-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sutherland MR, Raynor CM, Leenknegt H, Wright JF, Pryzdial EL. Coagulation initiated on herpesviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(25):13510–13514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sutherland MR, Friedman HM, Pryzdial EL. Thrombin enhances herpes simplex virus infection of cells involving protease-activated receptor 1. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(5):1055–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02441.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sutherland MR, Ruf W, Pryzdial EL. Tissue factor and glycoprotein C on herpes simplex virus type 1 are protease-activated receptor 2 cofactors that enhance infection. Blood. 2012;119(15):3638–3645. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-376814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Toussirot E, Roudier J. Epstein-Barr virus in autoimmune diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(5):883–896. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hyakutake M, Steinberg E, Disla E, Heller M. Concomitant infection with Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus infection leading to portal vein thrombosis. J Emerg Med. 2019;57(2):e49–e51. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Justo D, Finn T, Atzmony L, Guy N, Steinvil A. Thrombosis associated with acute cytomegalovirus infection: a meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(2):195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Simmonds P, Aiewsakun P. Virus classification – where do you draw the line? Arch Virol. 2018;163(8):2037–2046. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-3938-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wong RSM, Wu A, To KF, et al. Haematological manifestations in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2003;326(7403):1358–1362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7403.1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Chong PY, Chui P, Ling AE, et al. Analysis of deaths during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Singapore: challenges in determining a SARS diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128(2):195–204. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ng KHL, Wu AKL, Cheng VCC, et al. Pulmonary artery thrombosis in a patient with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(956):e3. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.030049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yang M, Ng MHL, Li CK, et al. Thrombopoietin levels increased in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Thromb Res. 2008;122(4):473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Shimizu M, Konishi A, Nomura S. Examination of biomarker expressions in sepsis-related DIC patients. Int J Gen Med. 2018;11:353–361. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S173684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Assiri A, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(9):752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Singh SK. Middle east respiratory syndrome virus pathogenesis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;37(4):572–577. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1584796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Han H, Yang L, Liu R, et al. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Giannis D, Ziogas IA, Gianni P. Coagulation disorders in coronavirus infected patients: COVID-19, SARS-Cov-1, MERS-CoV and lessons from the past. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104362. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lacour T, Semaan C, Genet T, Ivanes F. Insights for increased risk of failed fibrinolytic therapy and stent thrombosis associated with COVID-19 in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Bikdeli B, Madhaven MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease; implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Griffin DO, Jensen A, Khan M, et al. Pulmonary embolism and increased levels of d-dimer in patients with coronavirus disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Terpos E, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Elalamy I, et al. Hematological findings and complications of COVID-19. Am J Hematol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Schwab A, Meyering SS, Lepence B, et al. Extracellular vesicles from infected cells: potential for direct pathogenesis. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1132. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Rodrigues M, Fan J, Lyon C, Wan M, Hu Y. Role of extracellular vesicles in viral and bacterial infections: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapeutics. Theranostics. 2018;8(10):2709–2721. doi: 10.7150/thno.20576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zhang W, Jiang X, Bao J, Wang Y, Liu H, Tang L. Exosomes in pathogen infections: a bridge to deliver molecules and link functions. Front Immunol. 2018;9:90. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Brown M, Johnson LA, Leone DA, et al. Lymphatic exosomes promote dendritic cell migration along guidance cues. J Cell Biol. 2018;217(6):2205–2221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201612051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Anderson MR, Kashanchi F, Jacobson S. Exosomes in viral disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13(3):535–546. doi: 10.1007/s13311-016-0450-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Pleet ML, DeMarino C, Stonier SW, et al. Extracellular vesicles and Ebola virus: a new mechanism of immune evasion. Viruses. 2019;11(5):410. doi: 10.3390/v11050410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kesimer M, Scull M, Brighton B, et al. Characterization of exosome-like vesicles released from human tracheobronchial ciliated epithelium: a possible role in innate defense. FASEB J. 2009;23(6):1858–1868. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-119131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Suptawiwat O, Ruangrung K, Boonarkart C, et al. Microparticle and anti-influenza activity in human respiratory secretion. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Konadu KA, Huang MB, Roth W, et al. Isolation of exosomes from the plasma of HIV-1 positive individuals. J Vis Exp. 2016;107:e53495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Chettimada S, Lorenz DR, Misra V, et al. Exosome markers associated with immune activation and oxidative stress in HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7227. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25515-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Pérez PS, Romaniuk MA, Duette GA, et al. Extracellular vesicles and chronic inflammation during HIV infection. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019;8(1):1687275. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2019.1687275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Plazolles N, Humbert JM, Vachot L, Verrier B, Hocke C, Halary F. Pivotal advance: the promotion of soluble DC-SIGN release by inflammatory signals and its enhancement of cytomegalovirus -mediated Cis- infection of myeloid dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89(3):329–342. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0710386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Walker JD, Maier CL, Pober JS. Cytomegalovirus-infected human endothelial cells can stimulate allogeneic CD4+ memory T cells by releasing antigenic exosomes. J Immunol. 2009;182(3):1548–1559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Kuo HT, Ye X, Sampaio MS, Reddy P, Bunnapradist S. Cytomegalovirus serostatus pairing and deceased donor kidney transplant outcomes in adult recipients with antiviral prophylaxis. Transplantation. 2010;90(10):1091–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Meckes DG, Raab-Traub N. Microvesicles and viral infection. J Virol. 2011;85(24):12844–12854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Wurdinger T, Gatson NN, Balaj L, Kaur B, Breakefield XO, Pegtel DM. Extracellular vesicles and their convergence with viral pathway. Adv Virol. 2012;2012:767694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Delabranche X, Berger A, Boisramé-Helms J, Meziani F. Microparticles and infectious disease. Med Mal Infect. 2012;42(8):335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Coakley C, Maizels RM, Buck AH. Exosome and other extracellular vesicles: the new communicators in parasite infections. Trends Parasitol. 2015;31(10):477–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Schorey JS, Harding CV. Extracellular vesicles and infectious diseases: new complexity to an old story. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(4):1181–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Raab-Traub N, Dittmer DP. Viral effects on the content and function of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(9):559–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Altan-Bonnet N, Perales C, Domingo E. Extracellular vesicles: vesicles of en bloc viral transmission. Virus Res. 2019;265:143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Urbanelli L, Buratta S, Tancini B, et al. The role of extracellular vesicles in viral infection and transmission. Vaccines (Basel). 2019;7(3):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Goncalves-Alves E, Saferding V, Schliehe C, et al. MicroRNA-155 controls T helper cell activation during viral infection. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.AmraneDjedidi R, Rousseau A, Larsen AK, et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from pancreatic cancer cells BXPC3 or breast cancer cells MCF7 induce a permanent procoagulant shift to endothelial cells. Thromb Res. 2020;187:170–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Deffune E, Prudenciatti A, Moroz A. Mesenchymal stem cell (MSc) seretome: a possible therapeutic strategy for intensive-care COVID-19 patients. Med Hypotheses. 2020;142:109769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.O’Driscoll L. Extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stem cells as a COVID-19 treatment. Drug Discov Today. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Bari E, Ferrarotti I, Saracino L, Perteghella S, Torre ML, Corsico AG. Mesenchymal stromal cell secretome or severe COVID-19 infections: premises for the therapeutic use. Cells. 2020;9(4):924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Kumar S, Zhi K, Mukherji A, Gerth K. Repurposing antiviral protease inhibitors using extracellular vesicles for potential therapy of COVID-19. Viruses. 2020;12(5):E486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Schmedes CM, Grover SP, Hisada YM, et al. Increased circulating extracellular vesicle tissue factor activity during orthohatavirus infection is associated with intravascular coagulation. J Infect Dis. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Felsenstein S, Herbert JA, McNamara PS, Hedrich CM. COVID-19: immunology and treatment options. Clin Immunol. 2020;108448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Myer AD, Rishmawi AR, Kamucheka R, et al. Effect of blood flow on platelets, leukocytes, and extracellular vesicles in thrombosis of simulated neonatal extracorporeal circulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(2):399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Saenz-Pipaon G, San Martin P, Planell N, et al. Functional and transcriptomic analysis of extracellular vesicles identifies calprotectin as a new prognostic marker in peripheral arterial disease (PAD). J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;9:1729646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Zou B, She J, Wang Y, Ma X. Venous thrombosis and arteriosclerosis obliterans of lower extremities in a very severe patient with 2019 novel coronavirus disease: a case report. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]