Abstract

Serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of α-fetoprotein and β-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin are used as biomarkers for the management of central nervous system (CNS) germ cell tumors (GCTs). However, additional discriminating biomarkers are required. Especially, biomarkers to differentiate non-germinomatous germ cell tumors (NGGCTs) from germinomas are critical, as these have a distinct prognosis. We investigated CSF samples from 12 patients with CNS-GCT patients (8 germinomas and 4 NGGCTs). We analyzed circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in CSF to detect mutated genes. We also used liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to characterize metabolites in CSF. We detected KIT and/or NRAS mutation, known as frequently mutated genes in GCTs, in 3/12 (25%) patients. We also found significant differences in the abundance of 15 metabolites between control and GCT, with unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis. Metabolites related to the TCA cycle were increased in GCTs. Urea, ornithine, and short-chain acylcarnitines were decreased in GCTs. Moreover, we also detected several metabolites (e.g., betaine, guanidine acetic acid, and 2-aminoheptanoic acid) that displayed significant differences in abundance in patients with germinomas and NGGCTs. Our results suggest that ctDNA and metabolites in CSF can serve as novel biomarkers for CNS-GCTs and can be useful to differentiate germinomas from NGGCTs.

Subject terms: CNS cancer, Germ cell tumours, Cancer metabolism, Oncogenes

Introduction

Germ cell tumors (GCTs) in the central nervous system (CNS) are rare comprising less than 3% of primary brain tumors1–3. The incidence is different among races, being higher in Asians (0.136–0.179/100,000 people) than in Whites (0.078/100,000 people)1,2. GCTs occur in higher proportion in male patients, with a male: female ratio greater than 3:11,2. GCTs in the CNS predominantly occur in children and adolescents and usually occur in midline structures, typically in the pineal region, third ventricular region, and neurohypophysis. Germinoma is the most common type of GCTs and it is highly radiosensitive. The 5-year survival rate of germinoma exceeds 99%, according to a recent study3. In contrast, non-germinomatous GCTs (NGGCTs) require intense chemotherapy, craniospinal irradiation, and sometimes salvage surgical resection4,5, and have an unfavorable prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of 71.4–87.3%3. Thus, distinguishing between these tumor types is essential to determine the appropriate treatment strategy.

Serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of α-fetoprotein (AFP) and β-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG), and placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) levels in CSF are used as biomarkers for current clinical management of CNS GCTs4–6 and in some cases, initial treatment is based on the levels of AFP, β-HCG, and PLAP without tissue confirmation. The pineal region is one of the most frequent sites in which GCTs occur and they often cause non-communicating hydrocephalus.

Intraventricular endoscopy is a feasible and minimally invasive technique, allowing both, access to the lesion for histological analysis as well as CSF diversion via endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV). However, biopsied samples for histological analysis, particularly from neuro-endoscopy are often small, representing only a partial region of the tumor, which can lead to inaccuracies in histologic diagnosis due to sampling bias7,8. Histologically, GCTs are classified as pure germinoma or non-germinomatous germ cell tumors (NGGCT). However, NGGCT can contain germinoma components, which makes accurate histological diagnosis on small biopsies challenging, and in some cases, inaccurate. Moreover, some patients undergo treatment based on the levels of AFP and β-HCG, without biopsy or surgical resection. Therefore, additional diagnostic biomarkers for GCTs are of critical importance in neuro-oncology. Even though germinomas and NGGCTs are managed with chemotherapy and radiotherapy (not with surgery), therapeutic regimens such as radiation dose, are different and germinomas respond better to treatment4,5. Therefore, the distinction between germinoma and NGGCTs is crucial in providing patients with the optimal treatment.

In recent years, CSF has been shown to be a relevant source of informative biomarkers for CNS tumors9–13. We have previously reported on the analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and metabolites in the CSF of patients with lymphoma, gliomas, and metastatic CNS tumors14–16. In this study, we analyzed both ctDNA and metabolites in CSF from CNS GCT patients, with the aim of identifying biomarkers that could potentially be utilized in clinical practice.

Results

AFP and β-HCG levels

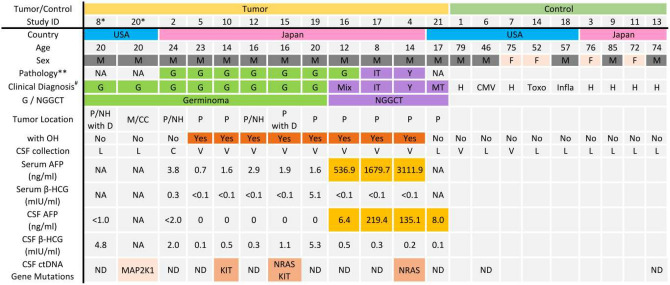

The biomarker levels of patients are summarized in Fig. 1. All patients with a histologic diagnosis of germinoma, but one, had low CSF AFP level of less than 2.0 ng/ml. One patient’s pathology report indicated germinoma (case #16), but his AFP levels in CSF and serum were 6.4 ng/ml and 536.9 ng/ml, respectively. Given the elevated AFP levels, it was considered that his tumor must have contained teratoma or embryonal tumor components, and it was decided to treat the patient with intensive chemotherapy and radiation. Other NGGCT patients had increased AFP levels in both CSF and serum, which were consistent with their histologic diagnosis. No patients from UTHealth/MHH underwent surgery for tumor resection, and the diagnosis was based on imaging and biomarker levels in CSF.

Figure 1.

Patient demographics, biomarker levels in GCT patients, and detected mutations in CSF ctDNA are shown. ** represents the histological diagnosis of each patient. # represents the final diagnosis based on the histological report, imaging diagnosis, and biomarkers. *: Case #20 was a recurrence of case #8. M male, F female, G germinoma, MT mature teratoma, Y yolk-sac tumor, Mix mixed germ cell tumor, IT immature teratoma, H normal pressure hydrocephalus, CMV cytomegalovirus infection, Toxo toxoplasmosis, Infla granulomatous inflammation, NGGGCT non-germinomatous germ cell tumor, P pineal, NH neurohypophysis, D dissemination, M medulla, CC corpus callosum, OH obstructive hydrocephalus, L lumbar puncture, C cistern, V ventricle, ND not detected.

Detection of mutations in ctDNA from CSF

We purified CSF ctDNA from 12 samples with CNS GCTs and 9 samples from control patients. There was a limited volume of CSF available and on average 1.71 ml of CSF were used to extract ctDNA. Among tumors, the median concentration and the median amount of extracted cell-free DNA for library preparation were 0.494 ng/μl (range 0.216–45.2) and 5.13 ng (range 2.25–20.0), respectively. Only two samples reached the manufacturer’s recommended amount of 20 ng (Table 1). We detected several gene mutations in CSF-ctDNA from intracranial GCT patients. KIT, NRAS, and MAP2K1 (Fig. 1, Table 1) mutations were found in 4 of 12 patients. The mutant allele fraction (MAF) ranged from 1.63 to 40.3%. No mutations were detected in the remaining 8 patients with GCTs or any of the control patients.

Table 1.

Extracted cfDNA amount and detected genetic alterations.

| ID | Tumor/control | Clinical diagnosis | CSF volume for ctDNA extraction (ml) | cfDNA concentration (ng/μL) | Input cfDNA (ng) | Genetic alterations | AF% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 06 | Control | CMV | 1.28 | 17.5 | 20.00 | ND | |

| 13 | Control | NPH | 2.88 | 0.876 | 9.11 | ND | |

| 08 | Tumor | Germinoma | 2.88 | 0.684 | 7.11 | ND | |

| 20 | Tumor | Recurrent germinoma | 1.78 | 0.556 | 5.78 | MAP2K1 p.F129L | 1.6 |

| 21 | Tumor | Mature teratoma | 2.28 | 45.2 | 20.00 | ND | |

| 02 | Tumor | Germinoma | 2.88 | 2.52 | 20.00 | ND | |

| 04 | Tumor | Yolk-sac tumor | 1.38 | 0.302 | 3.14 | NRAS p.Q61R | 34.6 |

| 05 | Tumor | Germinoma | 1.38 | 0.266 | 2.77 | ND | |

| 10 | Tumor | Germinoma | 1.38 | 0.466 | 4.85 | KIT p.D820G | 18.7 |

| 12 | Tumor | GERMINOMA | 0.88 | 0.264 | 2.75 | ND | |

| 15 | Tumor | Germinoma | 1.38 | 0.536 | 5.57 | NRAS p.G12S | 40.3 |

| KIT p.N822Y | 32.3 | ||||||

| 16 | Tumor | Germinoma | 1.38 | 0.216 | 2.25 | ND | |

| 17 | Tumor | Immature teratoma | 1.38 | 0.342 | 3.56 | ND | |

| 19 | Tumor | Germinoma | 0.38 | 0.518 | 5.39 | ND |

CMV cytomegalovirus infection, NPH normal pressure hydrocephalus, AF allele frequency, ND not detected.

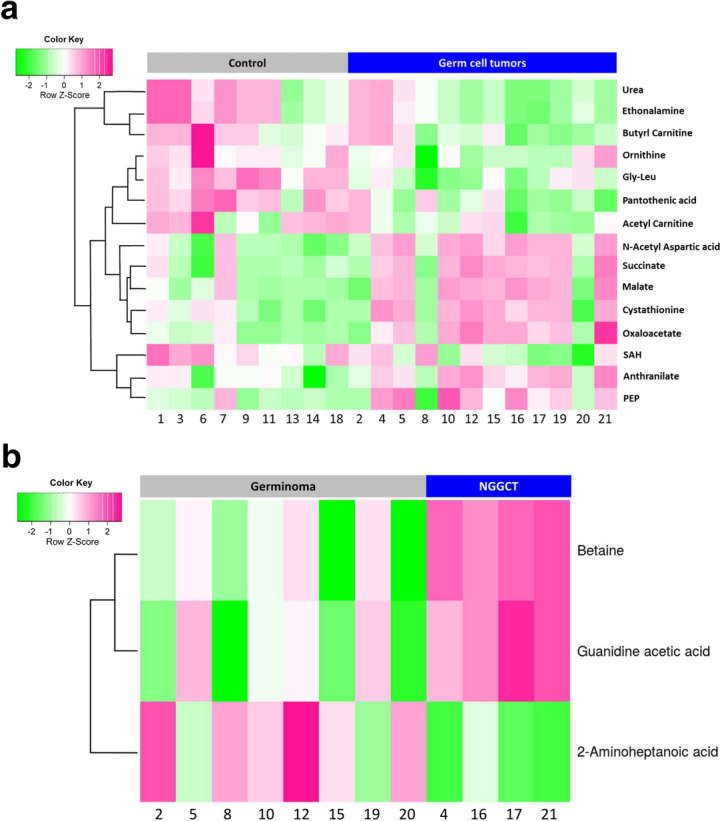

Comparison of metabolites in the CSF between germ cell tumors and controls

Using targeted metabolomics, we detected 146 named metabolites (in ESI positive ionization and negative ionization mode) in the CSF samples. We found differences in the abundance of 15 metabolites between control patients and intracranial GCT patients (FDR < 0.25) (Fig. 2A). Urea and ornithine, urea cycle metabolites, were decreased in GCTs. Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle metabolites, including succinate, malate, and oxaloacetate, were found to be elevated in the CSF from patients with GCTs. In addition, the TCA cycle-related metabolite phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), increased in the CSF from tumor patients. Pantothenic acid showed a significant decrease in GCTs. Metabolites related to methionine cycle, S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) decreased in GCTs, though cystathionine levels were increased. Acetylcarnitine and butyrlcarnitine showed decreased levels in GCTs, whereas N-acetylaspartic acid (NAA) was elevated in a majority of CSF samples from tumor patients.

Figure 2.

(A) Heat map of unsupervised hierarchical clustering of metabolites showing metabolite levels in the CSF of GCT patients and control CSF obtained from patients with no history of cancer. There are 15 differentially expressed metabolites between CSF from GCTs and controls (FDR < 0.25). (B) Heat map of unsupervised hierarchical clustering of metabolites showing 3 metabolites (Betaine, Guanidine acetic acid, and 2-aminoheptanoic acid) that are significantly different in the CSF from patients with NGGCTs and germinomas (FDR < 0.3).

CSF metabolites in germinoma versus Non-germinomatous germ cell tumors

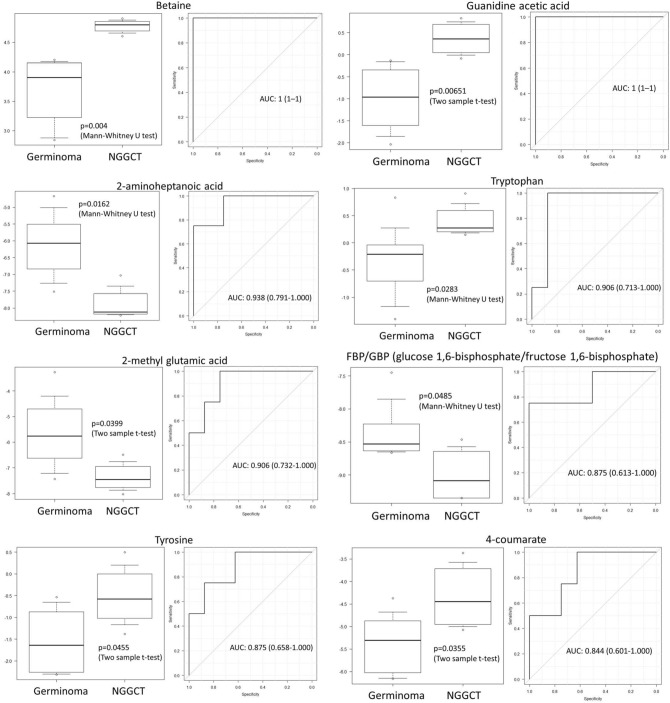

Distinguishing NGGCT form germinoma is important in clinical practice, therefore we compared metabolites in CSF derived from patients with germinoma and NGGCT. We identified three discriminating metabolites with FDR < 0.3 (Fig. 2B). Betaine and guanidine acetic acid were elevated in NGGCTs, and 2-aminoheptanoic acid was decreased in NGGCTs. Moreover, several additional metabolites, such as 4-coumarate, FBP/GBP, 2-methyl glutamic acid, tryptophan, and tyrosine, showed a significant difference between germinomas and NGGCTs (Fig. 3). We investigated the area under the receiver operator characteristics curve (AUC) for each of these differentially abundant metabolites for distinguishing between germinoma and NGGCT. Levels of betaine and guanidine acetic acid had shown AUC = 1, indicating great discriminating power. Six additional metabolites showed AUCs ranging from 0.844 to 0.938 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Box plots and area under the ROC curve of 8 metabolites. The levels of these metabolites are significantly different between germinoma and NGGCT. The CSF from patients with NGGCTs have elevated levels of Betaine, guanidine acetic acid, and tryptophan when compared with germinoma patients.

Discussion

Our study shows that genetic alterations frequently present in GCTs are detectable by analysis of CSF-ctDNA. We detected KIT and/or NRAS mutations in 3/12 patients (25%). We also identified a MAP2K1 mutation with a low MAF (case #20). This mutation was not observed in the CSF sample acquired at diagnosis in the same patient (case #8). Therefore, this mutation could have been acquired during tumor progression and/or treatment and might represent tumor evolution. Our validation experiments using CSF samples from patients without CNS tumors indicate that we can confidently identify mutations at a MAF greater than 0.25% (data not shown). Therefore, we favor that the MAP2K1 change is an acquired mutation that represents tumor evolution.

The mutations detected in CSF-ctDNA from patients with GCTs included in our study are consistent with reported mutations in GCTs tissue. Several studies have reported that mutations in MAPK and/or PI3K pathways are the dominant genetic drivers of GCTs17–19. A recent study from Japan with 124 CNS GCTs identified mutations in MAPK and/or PI3K pathways such as KIT (27.4%), MTOR (6.5%), KRAS (5.6%), and NRAS (3.2%)17. The rate of mutation detection in CSF-ctDNA in our study (25% of cases) was lower when compared to the literature showing that ~ 54% of GCTs had mutations in at least one of the genes involved in MAPK or PI3K pathways17,18 which are mostly covered by the Oncomine NGS assay. However, it is unclear what mutations were present in the tumors from patients in this study because mutation analysis of tumor tissues was not available.

An average of 1.71 ml of CSF from tumor patients was utilized to extract ctDNA, and the median amount of extracted cell-free DNA (cfDNA) for library preparation was 5.13 ng (Table 1). Considering the recommended cfDNA input for the Oncomine assay is 20 ng, the low volumes of CSF and low amounts of cfDNA might affect the rate of detecting mutations in this study. Our results suggest that volumes larger than 1.7 ml of CSF will be required to increase the sensitivity of CSF-ctDNA analysis in patients with GCTs using the Oncomine assay. However, we successfully detected mutations in case #4, starting with 1.38 ml of CSF volume and 3.14 ng of cfDNA used for library preparation and sequencing, indicating that small cfDNA amounts can provide good results in isolated cases.

Our study has the limitation that we were not able to evaluate some genetic alterations reported in CNS GCTs, such as NF1, CBL, and FGD6, which are not covered by the Oncomine Pan-Cancer Cell-Free Assay. Despite these limitations, our results suggest that evaluation of ctDNA in the CSF of patients with GCTs can be informative and identify mutations that are common drivers of CNS GCTs. Larger CSF volumes and NGS assays specifically designed to interrogate genes known to be altered in GCTs might be required to increase the sensitivity of this method.

We also investigated metabolites in the CSF from GCT patients and found significant differences in the levels of metabolites between GCT and control samples. We observed several altered metabolites related to the TCA cycle including succinate, malate, oxaloacetate, and PEP. Elevated succinate, malate (malic acid), and PEP levels were also demonstrated in the CSF of IDH-mutant glioma patients, in our previous study14, suggesting that elevations of these metabolites might be a common finding in the CSF of patients with various types of CNS tumors20. SAH and cystathionine levels were decreased and increased in GCTs, respectively. These metabolites are involved in the methionine cycle21–23. A recent study reported accumulated cystathionine in tissue samples from 1p/19q co-deleted gliomas, due to deletions of enzyme genes located in chromosome 1p22. However, the mechanisms for altered levels of SAH and cystathionine in the CSF of patients with GCTs remain to be elucidated.

Acylcarnitines are essential for the oxidative catabolism of fatty acids. They transport fatty acids into the mitochondria, and fatty acids are oxidized (β-oxidation) and converted to energy through the TCA cycle24. A study showed that plasma levels of acetylcarnitine negatively correlated with tumor grade in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma24. Studies on plasma metabolites indicate that changes in the MAPK or PI3K pathways are associated with alterations in metabolites including amino acids, acylcarnitines, and phosphatidylcholines25,26. Therefore, we assumed that GCTs, often associated with mutations in either MAPK or PI3K pathways, exhibited decreased levels of acetylcarnitine and butyrlcarnitine. However, samples were not available for us to explore this relationship further with tissue-based experiments.

NAA is the second most abundant metabolite in the brain, and it is synthesized from aspartate and acetyl-coenzyme A in neurons, by the enzyme aspartate N-acetyltransferase (Asp-NAT)27. Therefore, NAA is used as a neuron-specific marker, for instance, lower NAA concentration in CSF have been reported to correlate with worse clinical functioning and lower brain volume in multiple sclerosis patients28. We detected increased NAA in the CSF of most GCT patients. However, the interpretation of NAA levels should be done with caution, since NAA levels in CSF can be influenced by age and intracranial pressure29. The majority of GCT patients in this study were children or adolescents with non-communicating hydrocephalus with slightly or moderately increased intracranial pressure. In contrast, many of the control CSF samples in our study were elderly patients with NPH. Interestingly, recent studies have shown high expression of NAA metabolism enzymes in brown adipocytes suggesting that that NAA may be involved in lipid synthesis and histone acetylation. Higher expression of NAA synthesizing enzyme and increased amount of NAA, have been associated with worse survival in various cancer types30. Elevated NAA was also seen in the CSF from patients with both IDH-mutant and IDH-wildtype gliomas in our previous study14.

The levels of several metabolites were significantly different between germinomas and NGGCT. Differentiation between germinomas and NGGCTs is of crucial clinical importance. Increased levels of AFP in serum/CSF indicate that the GCT contains a component of a yolk sac tumor or immature teratoma. Except for germinoma with syncytiotrophoblastic cells, elevated β-HCG suggests an association with choriocarcinoma, embryonal tumor, or immature teratoma. GCTs with a highly malignant component require intensive chemotherapy and corticospinal irradiation4,5. Therefore, reliable diagnosis differentiating germinoma from NGGCT is essential to determine optimal patient treatment. Identification of the teratoma/immature teratoma component is also important because these components can cause large cystic masses (growing teratoma syndrome), during treatment31. We detected significantly elevated levels of betaine in NGGCT (Figs. 2B and 3). Betaine is known as an important osmotic regulator, has antioxidative or anti-inflammatory activity, and is a methyl group donor. Betaine distributes, particularly, to the kidneys, liver, and brain23,32. Although our sample size is small (4 NGGCTs vs. 8 germinomas), our findings indicate that several metabolites have the potential to discriminate germinomas from NGGCT. Therefore, the analysis of CSF metabolites could be instructive in identifying the presence of GCTs with malignant components that should be treated more aggressively.

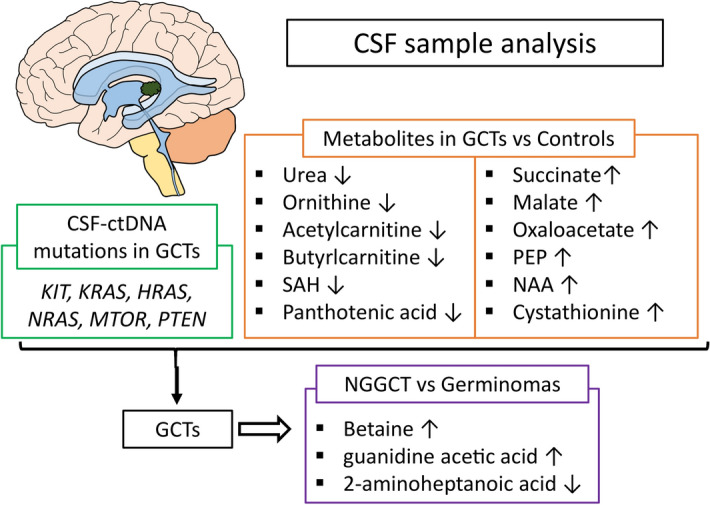

In conclusion, our results for the first time suggest that ctDNA and metabolites in CSF can serve as novel biomarkers for CNS GCTs, and can be useful in differentiating germinomas from NGGCTs (Fig. 4). Such biomarkers could also be potentially used to monitor patients following initial treatment and should be further investigated with a multi-institutional prospective study.

Figure 4.

Summary of alterations in CSF ctDNA and metabolites identified in our study. Evaluation of ctDNA and metabolites in CSF has the potential to differentiate patients with GCTs from patients with non-neoplastic diseases and to discriminate patients with NGGCT from patients with germinomas.

Methods

Patients

We included intracranial GCT patients treated at Hiroshima University Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan, from 2015 to 2018, or at Memorial Hermann Hospital/University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, from 2018 to 2019. Samples from patients (n = 12) and controls (n = 9) were utilized. The cohort consisted of 8 germinomas, 1 mature teratoma, 1 immature teratoma, and 1 yolk-sac tumor. The control group consisted of 6 normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) patients, 1 cytomegalovirus infection, 1 toxoplasmosis, and 1 granulomatous inflammation. CSF was collected during the endoscopic intraventricular intervention (biopsy/ETV) or lumbar puncture (LP) as part of routine clinical practice. Demographic information is summarized in Fig. 1. All CSF samples from GCT patients were obtained before adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy except one patient. A sample from a GCT patient (case #20) was the recurrence of case #8, and we collected the sample after treatment for recurrence. Control patients had no history of cancer.

This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB), at Hiroshima University Hospital and University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; respectively, in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

CSF collection

CSF samples were collected from the endoscopic intraventricular approach intraoperatively or lumbar puncture as part of routine clinical practice. Samples were processed within 3 h from the collection and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet was discarded, and the supernatant was immediately stored at -80 °C until the time of the analysis.

ctDNA analysis

A range of 0.38–2.88 mL of thawed CSF supernatant was used for the extraction of ctDNA. We used QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen, Germany), following manufacturer instructions. The cell-free DNA (cfDNA) concentration was quantified using the Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). For library preparation, we used Oncomine Pan-Cancer Cell-Free Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to detect mutations in CSF-ctDNA as per manufacturer’s instructions. This next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel covers alterations in 52-genes, including hotspot (SNVs) and short indels in AKT1, ALK, AR, ARAF, BRAF, CHEK2, CTNNB1, DDR2, EGFR, ERBB2, ERBB3, ESR1, FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, FGFR4, FLT3, GNA11, GNAQ, GNAS, HRAS, IDH1, IDH2, KIT, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAP2K2, MET, MTOR, NRAS, NTRK1, NTRK3, PDGFRA, PIK3CA, RAF1, RET, ROS1, SF3B1, SMAD4, and SMO. Although the recommended cfDNA input amount is 20 ng, the majority of our tumor samples did not reach 20 ng, the cfDNA input ranged from 2.25–20 ng. We chose 2 control samples with the highest cfDNA concentration. The final ctDNA libraries were purified using AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, Germany) and quantified using 4,200 TapeStation (Agilent, USA). Templating and sequencing were performed using the Ion 540 Chip on the Ion Chef and S5 XL systems with tag sequence technology (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). NGS data was analyzed with Ion Reporter Software (version 5.10).

Metabolomic analysis

For metabolomic analysis, 0.12 mL of CSF supernatant from each patient was used for the extraction of metabolites as described previously33,34. Targeted metabolic profiling was carried out by LC–MS/MS, 6,495 QQQ Mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) equipped with electro spray ionization (ESI) source. Single Reaction Monitoring (SRM) mode of ions with mass to charge ratio for metabolites were utilized for relative quantitative analysis of metabolites. We measured the metabolites using three different chromatographic methods (see supplementary methods), in each method metabolites were normalized with the spiked internal standards and data were log2-transformed on a per-sample, per-method basis. For clustering analysis, we performed the moderated t-test in the LIMMA package, to compare the differential metabolite levels between two groups35. Differentially expressed metabolites were identified after adjusting p-values for multiple hypothesis testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method36 and a false discovery rate (FDR) of < 0.25. Unsupervised clustering was used in this study and the analysis was conducted in R (version 3.5.2). AUC (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve) and its 95% confidence interval were evaluated by the “DeLong” method with EZR (version 1.40)37. For the box plot, differences in metabolites between two groups of patients were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test or two-sample t-test, depending on whether the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test showed a significant difference from the normal distribution in each data.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Masako Yoshihiro, and Ms. Yukie Nishiyama for their assistance with the collection and processing of Japanese patients’ samples. We also thank Dr. Tetsuya Takahashi, Department of Neurology, Hiroshima University, for providing control CSF samples of Japanese patients. We also want to acknowledge Satwikreddy Putluri and Aaditya Krishna Arun for assistance with mass spectrometry data anlaysis and peak integration.

Abbreviations

- GCT

Germ cell tumors

- CNS

Central nervous system

- NGGCTs

Non-germinomatous GCTs

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- AFP

α-Fetoprotein

- β-HCG

β-Subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin

- PLAP

Placental alkaline phosphatase

- ETV

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy

- ctDNA

Circulating tumor DNA

- NPH

Normal pressure hydrocephalus

- LP

Lumbar puncture

- cfDNA

Cell-free DNA

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- ESI

Electro spray ionization

- SRM

Single reaction monitoring

- FDR

False discovery rate

- MAF

Mutant allele fraction

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid

- PEP

Phosphoenolpyruvate

- SAH

S-adenosylhomocysteine

- NAA

N-acetylaspartic acid

- Asp-NAT

Aspartate N-acetyltransferase

Author contributions

Conception and design: L.Y.B., Y.E., F.Y. Collection of clinical samples and data: A.D., J.-J.Z., Y.E., S.H., F.Y., H.T., K.S., K.K. Experimental analysis: T.T., M.S., R.B., N.P. Statistical analysis: T.T., Y.Y. Writing and review the manuscript: T.T., M.S., A.D., J.-J.Z., F.Y., K.S., Y.E., L.Y.B.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the Japan-U.S. Brain Research Cooperation Program and Grants-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17K16649). This project was also supported by NIH (P30 CA125123), CPRIT Proteomics and Metabolomics Core Facility (N.P.), (RP170005), and Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Fumiyuki Yamasaki, Email: fyama@hiroshima-u.ac.jp.

Leomar Y. Ballester, Email: Leomar.Y.Ballester@uth.tmc.edu

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-71161-0.

References

- 1.Gittleman H, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of germ cell tumors of the central nervous system diagnosed in the United States from 2006 to 2015. J. Neurooncol. 2019;143:251–260. doi: 10.1007/s11060-019-03173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SH, et al. Nationwide population-based incidence and survival rates of malignant central nervous system germ cell tumors in Korea, 2005–2012. Cancer Res. Treat. 2017;49:494–501. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brain Tumor Registry of Japan (2005–2008). Neurol. Med. Chir. (Tokyo).57, 9–102 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Bowzyk Al-Naeeb A, et al. Current management of intracranial germ cell tumours. Clin. Oncol. 2018;30:204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray MJ, et al. Consensus on the management of intracranial germ-cell tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e470–e477. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aihara Y, et al. Placental alkaline phosphatase levels in cerebrospinal fluid can have a decisive role in the differential diagnosis of intracranial germ cell tumors. J. Neurosurg. 2019;131:687–694. doi: 10.3171/2018.3.JNS172520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luther N, Edgar MA, Dunkel IJ, Souweidane MM. Correlation of endoscopic biopsy with tumor marker status in primary intracranial germ cell tumors. J. Neurooncol. 2006;79:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-9110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinoshita Y, et al. Pitfalls of neuroendoscopic biopsy of intraventricular germ cell tumors. World Neurosurg. 2017;106:430–434. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontanilles M, Duran-Peña A, Idbaih A. Liquid biopsy in primary brain tumors: Looking for stardust. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2018;18:2. doi: 10.1007/s11910-018-0820-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller AM, et al. Tracking tumour evolution in glioma through liquid biopsies of cerebrospinal fluid. Nature. 2019;565:654–658. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0882-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connolly ID, Li Y, Gephart MH, Nagpal S. The, “Liquid Biopsy”: the role of circulating DNA and RNA in central nervous system tumors. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2016;16:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0629-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan C, et al. Molecular profiling of tumors of the brainstem by sequencing of CSF-derived circulating tumor DNA. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;137:297–306. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1936-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zorofchian S, et al. Circulating tumour DNA, microRNA and metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid as biomarkers for central nervous system malignancies. J. Clin. Pathol. 2019;72:271–280. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2018-205414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballester LY, et al. Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid metabolites in patients with primary or metastatic central nervous system tumors. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018;6:85. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0588-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zorofchian S, et al. Detection of the MYD88 p.L265P mutation in the CSF of a patient with secondary central nervous system lymphoma. Front. Oncol. 2018;8:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballester LY, et al. Evaluating circulating tumor DNA from the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with melanoma and leptomeningeal disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2018;77:628–635. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nly046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ichimura K, et al. Recurrent neomorphic mutations of MTOR in central nervous system and testicular germ cell tumors may be targeted for therapy. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:889–901. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1557-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, et al. Novel somatic and germline mutations in intracranial germ cell tumours. Nature. 2014;511:241–245. doi: 10.1038/nature13296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phi JH, Wang KC, Kim SK. Intracranial germ cell tumor in the molecular era. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2018;61:333–342. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2018.0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu J-Y, et al. Cancer-derived succinate promotes macrophage polarization and cancer metastasis via succinate receptor. Mol. Cell. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanderson SM, Gao X, Dai Z, Locasale JW. Methionine metabolism in health and cancer: A nexus of diet and precision medicine. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2019;19:625–637. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Branzoli F, et al. Cystathionine as a marker for 1p/19q codeleted gliomas by in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neuro. Oncol. 2019;21:765–774. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noz031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohnishi T, et al. Investigation of betaine as a novel psychotherapeutic for schizophrenia. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:432–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Y, et al. Acetylcarnitine is a candidate diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2912–2920. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ang JE, et al. Plasma metabolomic changes following PI3K inhibition as pharmacodynamic biomarkers: Preclinical discovery to phase I trial evaluation. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1412–1424. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ang JE, et al. Modulation of plasma metabolite biomarkers of the MAPK pathway with MEK inhibitor RO4987655: Pharmacodynamic and predictive potential in metastatic melanoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017;16:2315–2323. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moffett JR, Ross B, Arun P, Madhavarao CN, Namboodiri AMA. N-Acetylaspartate in the CNS: From neurodiagnostics to neurobiology. Prog. Neurobiol. 2007;81:89–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jasperse B, et al. N-acetylaspartic acid in cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients determined by gas-chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Neurol. 2007;254:631–637. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0415-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cleeland C, Pipingas A, Scholey A, White D. Neurochemical changes in the aging brain: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019;98:306–319. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogner-Strauss JG. N-acetylaspartate metabolism outside the brain: Lipogenesis, histone acetylation, and cancer. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2017;8:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamasaki F, et al. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy detection of high lipid levels and low apparent diffusion coefficient is characteristic of germinomas. World Neurosurg. 2018;112:e84–e94. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao G, et al. Betaine in inflammation: Mechanistic aspects and applications. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amara CS, et al. Serum metabolic profiling identified a distinct metabolic signature in bladder cancer smokers: A key metabolic enzyme associated with patient survival. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019;28:770–781. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vantaku V, et al. Large-scale profiling of serum metabolites in African American and European American patients with bladder cancer reveals metabolic pathways associated with patient survival. Cancer. 2019;125:921–932. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ritchie ME, et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y, Benjamini HY. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.