The optimal role for involving parents in adolescent obesity treatment remains unclear, and many opportunities for future research in this area are described.

Abstract

Video Abstract

CONTEXT:

Family-based lifestyle interventions are recommended for adolescent obesity treatment, yet the optimal role of parents in treatment is unclear.

OBJECTIVE:

To examine systematically the evidence from prospective randomized controlled and/or clinical trials (RCTs) to identify how parents have been involved in adolescent obesity treatment and to identify the optimal type of parental involvement to improve adolescent weight outcomes.

DATA SOURCES:

Data sources included PubMed, PsychINFO, and Medline (inception to July 2019).

STUDY SELECTION:

RCTs evaluating adolescent (12–18 years of age) obesity treatment interventions that included parents were reviewed. Studies had to include a weight-related primary outcome (BMI and BMI z score).

DATA EXTRACTION:

Eligible studies were identified and reviewed, following the Preferred Reporting for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Study quality and risk of bias were evaluated by using the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool.

RESULTS:

This search identified 32 studies, of which 23 were unique RCTs. Only 5 trials experimentally manipulated the role of parents. There was diversity in the treatment target (parent, adolescent, or both) and format (group sessions, separate sessions, or mixed) of the behavioral weight loss interventions. Many studies lacked detail and/or assessments of parent-related behavioral strategies. In ∼40% of unique trials, no parent-related outcomes were reported, whereas parent weight was reported in 26% and associations between parent and adolescent weight change were examined in 17%.

LIMITATIONS:

Only RCTs published in English in peer-reviewed journals were eligible for inclusion.

CONCLUSIONS:

Further research, with detailed reporting, is needed to inform clinical guidelines related to optimizing the role of parents in adolescent obesity treatment.

More than one-third of children in the United States have overweight or obesity; rates are even greater among adolescents and racial and ethnic minorities.1 Youth with obesity face a significant lifelong burden of cardiometabolic disease, including type 2 diabetes2–5; thus, the need for effective adolescent obesity treatment is urgent. Family-based lifestyle interventions are recommended for pediatric obesity treatment, and clinical guidelines consistently emphasize the importance of including parents in these interventions.6–10 Indeed, a systematic review of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, position, and consensus statements on the management of pediatric obesity found that all of the included statements recommended that parents be involved in an adolescent lifestyle intervention.11 More recently, the American Psychological Association published evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the behavioral treatment of obesity in children and adolescents and recommended family-based multicomponent behavioral interventions for children and adolescents with overweight or obesity. Specifically, the policy states, “the intervention is not solely provided to the…adolescent; rather…involves the parents and potentially other family members as active participants.…”12 Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends involving parents in obesity treatment through strategies such as parental monitoring, limit setting, reducing barriers, managing family conflict, and modifying the home environment.13 However, despite these clear recommendations to involve parents in their adolescents’ obesity treatment, there are limited data to support which specific parental involvement strategies should be used, and there is even less information about which strategies are most effective in improving adolescent weight outcomes.11 Evidence-based guidance addressing the optimal role of parents in adolescent obesity treatment is needed to inform empirical investigations, enhance treatment effectiveness, and provide clear and consistent guidance to providers.

Obesity during adolescence is likely to persist into adulthood.14 This developmental stage is a unique, yet vital, opportunity for family-based treatment. In general, family-based adolescent obesity treatment yields modest improvements in BMI and metabolic risk factors.15–17 Parental involvement in treatment is associated with even better health outcomes,18,19 with results of a meta-analysis suggesting that it accounts for ∼20% of the variance in child weight.18 Most studies targeting obesity in youth were conducted with school-aged children; less is known about adolescent populations. Adolescence can present substantial challenges to family-based care because it is marked by a developmentally normative period of opposition to authority, role transformations, and increasing personal responsibility.20,21 Adolescents experience an increased desire for independence and autonomy, yet they still rely on parents for many needs.21 Given these challenges, it is not surprising that research investigating specific clinical paradigms for parent involvement in adolescent obesity treatment is inconsistent, with mixed findings regarding the ideal level of parental involvement and the specific parenting strategies that can optimize treatment.11,22

A focus on parents is vital for childhood obesity treatment for numerous reasons. For example, parental obesity is associated with child overweight,8,23 parents are powerful role models of eating and exercise behaviors,24,25 parent feeding behaviors influence children’s eating habits and weight,26–29 and the home environment strongly influences children’s lifestyle choices.30,31 Yet a closer examination of the literature reveals that few studies have investigated the role of parents in adolescent treatment.22,32,33 In addition, there is no consensus regarding how to optimize parental involvement across developmental stages.11,13,18,19,34–36 In an integrative review of parent participation in obesity interventions with African American adolescent girls, the authors noted the lack of data regarding the ideal type of parental involvement; they further highlighted the need for evidence regarding which parent variables are associated with adolescent BMI reduction.32 Although clinical guidelines consistently emphasize the importance of including parents in pediatric behavioral weight loss interventions, the optimal way in which to operationalize this involvement is unknown. As such, our goal for this article is to systematically review the research on behavioral lifestyle interventions (ie, those that address diet, physical activity, and/or behavior change to achieve weight loss) for adolescent obesity that involve parents to identify (1) how parents are included in treatment and (2) the optimal role of parents within treatment to enhance adolescent weight loss (eg, BMI), specifically, which elements of parental involvement are positively associated with adolescent weight loss.

Methods

The conduct and reporting of this review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses.37 This review was deemed exempt from institutional review board review.

Study Selection

Randomized controlled and/or clinical trials (RCTs) (either active comparator or control group) used to evaluate a behavioral weight loss intervention (ie, addressed diet, physical activity, and/or behavior change) among adolescents aged 12 to 18 years without major intellectual or developmental disabilities were considered. Trials had to be conducted in the United States (given that the obesogenic environment, parenting roles, and family structure vary geographically) and had to include some degree of parental involvement with a weight-related primary adolescent outcome (eg, BMI, BMI z score). Published articles had to be peer reviewed, had to be written in English, and had to have full text available. Studies were excluded if the trial did not include a control or comparison group, was focused on obesity and/or weight gain prevention or weight within the context of a medical condition (eg, diabetes), or tested a drug and/or surgical intervention.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

The search strategy was developed in consultation with an information specialist (Mrs Nita Bryant, Virginia Commonwealth University). A comprehensive literature search was conducted through the electronic databases PubMed, Medline, and PsychINFO. The following search terms were included to retrieve studies based on participants and outcomes, with the Boolean phrase “AND” used between groups and “OR” used within groups, to maximize the search’s sensitivity: (adolescent* OR teen*) AND (obes* OR overweight OR weight loss OR weight management OR weight control) AND (parent* OR caregiv* OR family) AND (intervention OR trial OR treatment OR behavior therapy OR randomized controlled trial). Searches were limited to “English,” “human,” and “RCT” when appropriate. Reference lists of systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and related articles were hand searched for potential citations. Searches were conducted independently by 2 authors (L.J.C. and C.B.B.) in April 2018. An updated search was conducted in July 2019 by using the same search terms and databases above to identify any studies published in the previous year that met inclusion criteria.

Screening and Data Extraction

All retrieved citations were screened by 2 independent authors following predetermined inclusion criteria (L.J.C. and C.B.B.). Duplicates were removed; multiple articles published from the same trial were included if the outcome measure, follow-up time frame, or parent variables differed. Titles and abstracts of all articles were reviewed, followed by full-text articles if inclusion could not be determined from the title and abstract. In the case of disagreements at each stage of the selection process, consensus was reached through discussion with a third author (M.K.B.). A data extraction template was then developed to meet the aims of this review. This form was pilot tested on a sample of studies and revised before use. Two authors (L.J.C. and C.B.B.) independently extracted data from each included article, including bibliographic information, population (demographics, sample size, and baseline characteristics), parent involvement, study design (duration, contact, and format), adolescent intervention approach, parent intervention approach, adolescent weight outcomes, and parent outcomes (if reported).

Quality Assessment

The Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool was used to assess the risk of bias among the RCTs in this review.38,39 Two authors (L.J.C. and C.B.B.) independently applied these criteria. Discrepancies were discussed, and if consensus could not be reached, a third author was consulted (M.K.B.). Each study was given an overall rating of low risk, high risk, or unclear risk by using guidelines from the Cochrane tool.

Results

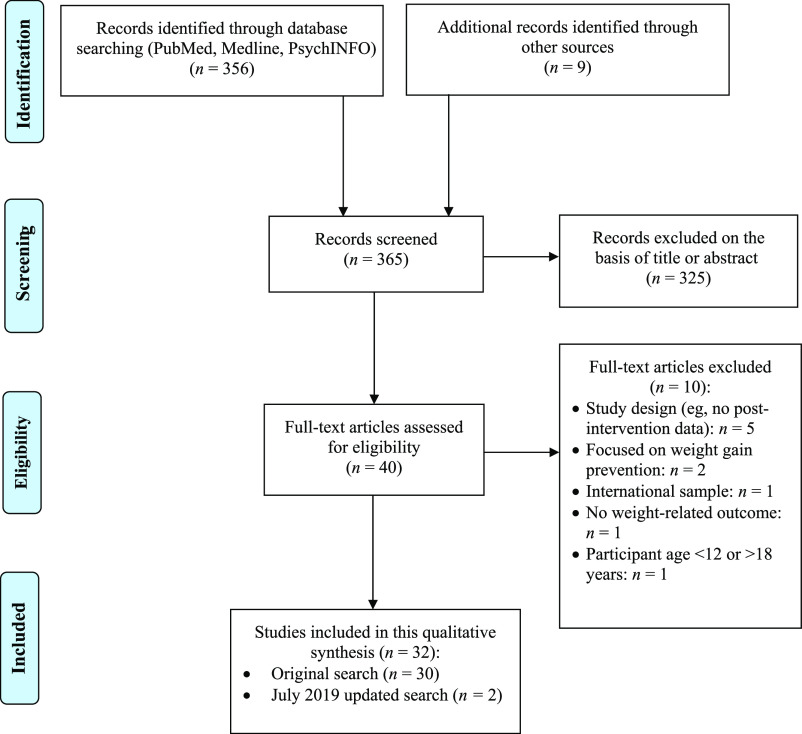

In the initial PubMed search, we retrieved 1070 articles. Search results from all databases were filtered to include only RCTs and were consolidated to remove duplicates, resulting in 356 unique articles (Fig 1). An additional 9 articles were retrieved from bibliographies of relevant reviews. Ultimately, 32 articles met criteria to be included in this systematic review (n = 30 from the original search; n = 2 from the updated search conducted in July 2019). Of these 32 articles, there were 23 unique trials, with 6 trials having >1 published article included in this review.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

There was strong consistency in bias ratings between raters (99.1%); 100% of discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Of the 23 unique trials, 56.5% were rated as low risk, 34.8% were rated as unclear risk, and 8.7% were rated as high risk of bias (Table 1). Of the studies with an unclear risk, most did not report when randomization occurred, how procedures were applied, and/or if participants were masked (although it is typically not feasible to keep participants masked in behavioral treatment).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Studies Included in a Systematic Review on the Role of Parents in Adolescent Obesity Treatment

| Study (Year) | n; Age; Sex; Race and/or Ethnicitya | Adolescent Intervention | Parent Involvement Methods | Treatment Length | Primary Adolescent wt Outcomes | Parent Outcomes or Relation of Parents to Adolescent Outcomes | Implications Related to Role of Parents | Risk of Biasb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berkowitz et al40 (2011) | n = 113; 15 ± 1.3 y; female sex: 81%; African American: 62%, white: 26%, other or unknown: 12% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) LMP and LCD for 12 mo; (2) LMP and MR for 4 mo, LCD for 8 mo; (3) LMP and MR for 12 mo | All groups: parents in separate groups from adolescents (parent groups not described) | 12 mo | At 4 mo, adolescents in LMP and MR group had greater %BMI reduction (6.3% ± 0.6%) than adolescents in LMP and LCD group; from 5 to 12 mo, no group differences in Δ%BMI | None reported | The role of parents in treatment outcomes is unclear because of design and lack of reporting on parent variables. | Low |

| Xanthopoulos et al41 (2013)c | See Berkowitz et al40 (2011) | See Berkowitz et al40 (2011) | See Berkowitz et al40 (2011) | 12 mo | See Berkowitz et al40 (2011) | Parents lost 2.0% of initial BMI at 4 mo and maintained a 1.3% loss at 12 mo; significant association between parent and adolescent Δ%BMI from 0 to 4 mo and from 0 to 12 mo; when parents lost more than the median at 4 mo, adolescents had greater wt loss at 12 mo compared with adolescents whose parents lost less than the median at 4 mo | When both the adolescent and parent(s) have excess wt, it appears especially beneficial for long-term adolescent wt loss that parents engage in their own wt loss efforts. | Low |

| Berkowitz et al42 (2013) | n = 169; 14.6 ± 1.4 y; female sex: 77%; African American: 47%, white: 47% | Adolescents randomly assigned to: (1) group LMP, (2) self-guided LMP (met with health coach and reviewed self-guided lessons) | Group: parents in separate groups from adolescents (parent groups not described); self-guided: parent and adolescent grouped together (parent in a supporting role) | 12 mo | Adolescents in both groups had significant Δ%BMI reduction from 0 to 12 mo (group: 1.3% ± 0.95%; self-guided: 1.2% ± 1.0%); no group differences in Δ%BMI | None reported | Both groups included parents and had comparable outcomes; the role of parents is unclear because of design and lack of reporting on parent variables. | Low |

| Brownell et al43 (1983) | n = 42; 13.8 ± 1.4 y; female sex: 78%; white: 100% | All adolescents received group LMP, randomly assigned to (1) MCS (concurrent groups), (2) MCT, (3) CA | MCS: mothers told they were crucial to success and encouraged to communicate and/or work together with adolescents; MCT: participants were told being together in groups was optimal; CA: no parent involvement | 16 wk | MCS adolescents had greater Δwt from 0 to 16 wk (8.4 kg) than other groups (5.3 and 3.3 kg); magnitude of differences increased at 1 y | No differences in mother Δwt between groups; Mother Δwt was not correlated with child Δwt | Greatest adolescent wt loss achieved when mothers and adolescents were treated separately but concurrently | Unclear |

| Coates et al44 (1982) | n = 31; 15.6 (age range:13–17) y; female sex: 65% | All adolescents received group LMP, randomly assigned to (1) PP, (2) NP | PP: parents (separate from teenagers) taught to support adolescent wt loss through modeling, role play, and self-monitoring; parents deposited $95 and refunded on the basis of adherence and post completion; NP: parents deposited $35, refunded at post intervention. | 20 wk | PP adolescents had greatest decrease in percentage above ideal wt (8.4% by end of intervention and maintained at follow-up); PP adolescents and NP adolescents had comparable decrease in percentage above ideal wt at 9-mo follow-up | None reported | Parent participation in treatment enhanced short-term adolescent wt loss but no long-term effect | High |

| DeBar et al45 (2012) | n = 208; 14.1 ± 1.4 y; female sex: 100%; white: 75% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) LMP with a multicomponent developmentally tailored behavioral intervention, (2) UC | Intervention: parents attended separate weekly group meetings in mo 1–3 with the same nutrition and PA content as adolescents; family meals, role modeling, and adolescent autonomy support emphasized; UC: parents received a guide to help adolescents make healthy changes | 5 mo | Change in BMIz across 12 mo was greater for intervention adolescents compared with UC adolescents (−0.15 vs −0.08 BMIz) | None reported | Home environment changes, role modeling, and fostering adolescent autonomy was effective as part of a comprehensive treatment. However, with limited or no parent data, the role of parents in treatment outcomes is unclear. | Low |

| Ellis et al46 (2010) | n = 49; 14.5 ± 1.6 y; female sex: 77%; African American: 100% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) MST: intensive, family-centered, community-based treatment delivered in home, school, or neighborhood; (2) control: Shapedown manualized group intervention | MST: parents learned healthy dietary practices, importance of regular meal and exercise times, role modeling of healthy behaviors, and reinforcement of adolescent success; Control: parents and adolescents together | 6 mo | Effect of treatment on BMI not reported; adolescents receiving MST had increased family support for healthy eating and exercise | MST participants had greater improvements in family encouragement and decreased family discouragement compared with control participants. Increased family support for exercise was negatively correlated to 7-mo adolescent BMI, percentage overweight, and body fat; however, analyses did not control for baseline BMI. | Family participation in exercise might be associated with better adolescent wt loss outcomes. | Low |

| Fleischman et al47 (2016) | n = 40; 14.3 ± 1.9 y; female sex: 78%; white: 88%, other or unknown: 13% | All adolescents received LMP, randomly assigned to (1) PCP visits plus televisits with obesity specialists (PCP + specialists) for 6 mo, then PCP visits only for 6 mo, (2) PCP visits only for 6 mo then PCP + specialist visits for 6 mo | Both groups: parents and adolescents were together in dietitian and psychologist televisits | 12 mo | BMIz decreased in both groups by 12 mo (−0.11 ± 0.05); no group differences in ΔBMI | Parents reported acceptability of televisits, and many indicated they would not have otherwise sought treatment. | Offering telehealth might help increase parent engagement in adolescent treatment. | Unclear |

| Janicke et al48 (2008) | n = 93; >50% ≥11 y (age range: 8–14 y); female sex: 61%; white: 67%–81%, African American: 4%–14%, Asian American: 4%–17%, mixed race: 0%–11.5% | Families randomly assigned to (1) FB, (2) PO, (3) WLC | FB: parents and children attended simultaneous (separate) groups that included (1) review of progress; (2) nutrition, PA, and behavior education and skills training; (3) children and parents reconvened for goal setting. PO: same content as FB, but only parents attended sessions; parents trained to work with children on goal setting. | 4 mo | PO adolescents had a greater decrease in BMIz at 4 mo relative to WLC (mean difference, 0.13). There was no difference between WLC and FB. PO and FB had a greater decrease in BMIz at 10 mo relative to WLC (0.12 and 0.14, respectively). There was no difference in ΔBMIz between PO and FB at 4 or 10 mo. For children ≥11 y, FB had a 50% greater decrease in BMIz than PO. | No differences in parent ΔBMI between treatment conditions at either assessment time point. No associations between parent ΔBMI and change in child wt status at either assessment time point. | Potential moderating effect of age suggested that adolescents (aged 11 y and older) might benefit more from a family-based intervention. These children might be more developmentally ready to employ the skills taught and thus should be included in treatment. | High |

| Jelalian et al49 (2006) | n = 76; 14.5 ± 0.9 y; female sex: 72%; white: 78%, other or unknown: 22% | All adolescents received weekly group CBT LMP, randomly assigned to (1) CBT plus supervised traditional cardiovascular PA (CBT + EXER), (2) CBT + PEAT | Both groups: parents and adolescents in separate groups plus biweekly parent-adolescent dyad meetings. Parents received similar content and information on family-level implementation of behavior changes | 16 wk | Adolescents lost wt in both treatment conditions, with no group differences at 16 wk (−5.31 kg for CBT + PEAT and−3.20 kg for CBT + EXER); percentage of participants maintaining 10 lb wt loss at 10 mo greater for CBT + PEAT (35%) than for CBT + EXER (12%); age by treatment group interaction with older adolescents in CBT + PEAT >4 times greater wt loss than older adolescents in CBT + EXER | Parents of adolescents in the CBT + EXER group did not differ from parents of adolescents in the CBT + PEAT group on an overall measure of treatment satisfaction | Parental satisfaction equivalent for both groups; with limited or no parent data, the role of parents in treatment outcomes is unclear | Low |

| Jelalian et al50 (2008)c | n = 76; 14.5 ± 0.9 y; female sex: 72%; white: 78%, other or unknown: 22% | See Jelalian et al49 (2006) | See Jelalian et al49 (2006) | 16 wk | Male sex, nonminority race, higher attendance, and early wt loss predicted greater wt loss at 16 wk | Higher baseline parent BMI predicted attrition at 4 mo (adolescents of heavier parents were 4.6 times more likely to drop out). Family support for eating and/or PA was unrelated to wt loss. | Potential importance of attending to parental BMI in efforts to retain participants in treatment | Low |

| Jelalian et al51 (2010) | n = 118; 14.3 ± 1.0 y; female sex: 68%; white: 72%–82%, African American: 11%–16%, other or unknown: 7%–10% | All adolescents received weekly group CBT-based LMP, randomly assigned to (1) CBT + EXER, (2) CBT + PEAT | Both groups: parents and adolescents in separate groups with parallel content; provided guidance on implementing family-level change and supporting positive eating and PA habits in adolescents | 16 wk | Compared with baseline BMIs (CBT + EXER: 31.3 ± 3.1 BMI; CBT + PEAT: 31.5 ± 3.5 BMI), there was a decrease in wt loss outcomes at 16 wk (CBT + EXER 30.0 ± 3.4 BMI; CBT + PEAT 30.0 ± 3.8 BMI) and 12-mo follow-up (CBT + EXER 30.6 ± 3.8 BMI; CBT + PEAT 30.3 ± 3.9 BMI); no differences by treatment condition | None reported | Attendance and dietary record completion were related to BMI reduction. Parents are instrumental in supporting adolescent session attendance and could facilitate the completion of weekly diet records. Thus, it is possible that parental support facilitated the adolescent changes that led to wt reduction. With limited or no parent data, the role of parents in treatment outcomes is unclear | Low |

| Sato et al52 (2011)c | n = 86; 14.3 ± 1.0 y; female sex: 70.9%; white: 76%, African American: 15%, other or unknown or mixed race: 9% | See Jelalian et al51 (2010) | See Jelalian et al51 (2010) | 16 wk | See Jelalian et al51 (2010) | Decrease in parent BMI (baseline BMI 30.4 ± 6.9) with no effect of treatment condition; relationship between decreases in parent and adolescent BMI from 0 to 4 mo | Parental wt loss and involvement (including parental monitoring of own eating and exercise behaviors) associated with adolescent BMI decrease | Low |

| Jelalian et al53 (2015) | n = 49; 15.1 ± 1.3 y; female sex: 76%; white: 67%, Hispanic: 12%, other or unknown: 21% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) SBT with LMP and cognitive restructuring, (2) SBT + EP | SBT: parents attended 3 sessions about general wt control strategies, reviewed adolescent progress; SBT + EP: parents attended separate (concurrent) sessions focused on role modeling healthy wt control practices and improved parent-adolescent communication about wt-related behaviors | 16 wk | Significant decrease in adolescent BMI observed across both conditions; ANCOVA revealed trend for greater reduction in wt among SBT versus SBT + EP participants (30.8 vs 31.8 mean BMI, respectively) | Increase in parental self-monitoring observed across both conditions; parents in both conditions reported increase in wt control behaviors but no decrease in parent BMI | Targeting parent-adolescent communication and parental modeling did not lead to better adolescent wt outcomes. | Low |

| Hadley et al54 (2015)c | n = 38; 15.1 ± 1.3 y; female sex: 76%; white: 63%, African American: 11%, Asian American: 3%, American Indian: 5%, mixed race: 8%, other or unknown: 11% | See Jelalian et al53 2015 | See Jelalian et al53 2015 | 16 wk | See Jelalian et al53 2015 | No differences in quality of mother-adolescent communication between conditions; baseline communication quality not related to adolescent wt loss; decline in communication quality related to better wt outcomes for adolescents in SBT | The decline in communication quality related to wt loss could reflect increased adolescent autonomy, although this is not clear. | Low |

| Kitzman-Ulrich et al55 (2009) | n = 42; 13.3 y; female sex: 100%; white: 55% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) multifamily therapy plus psychoeducation (a behavioral skill–building wt loss program), (2) psychoeducation only, (3) WLC | Multifamily: parents attended the group sessions with adolescents; psychoeducation: parents received the psychoeducational curriculum in group sessions with adolescents. | 16 wk | No changes in BMIz from baseline to post intervention by group; psychoeducational-only adolescents had greater energy intake decreases than adolescents in other conditions. | Changes in family nurturance (warmth and caring) were inversely related to adolescent energy intake. Family conflict scores worsened in participants in multifamily therapy relative to those in the other conditions. | Family nurturance could be an important variable to target in an adolescent wt loss intervention. | Unclear |

| Mellin et al56 (1987) | n = 66; 15.6 y; female sex: 79%; white: 88%, Hispanic: 8%, Asian American: 2%, African American: 3% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) Shapedown LMP, (2) WLC | Shapedown: parents attended 2 sessions focused on strategies to support child wt loss and improve family diet, activity, and communication skills. | 3 mo | Shapedown adolescents had improvement in relative wt at 3 mo (−9.9% ± 15%) compared with controls (−0.1% ± 13.2%). At 15 mo, wt change for Shapedown adolescents compared with controls was −5.15 kgd | Parent participation in 2 sessions versus 0 or 1 was associated with greater adolescent wt loss | Parent participation in treatment is associated with adolescent wt loss | Unclear |

| Naar-King et al57 (2009) | n = 48; 14.5 ± 1.6 y; female sex: 77%; African American: 100% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) MST with adaptations to increase adolescent and family adherence to dietary and exercise recommendations, (2) control: Shapedown LMP | Parents were involved in sessions in both conditions (parent involvement not described further) | 6 mo | MST adolescents significantly reduced %OW, percentage body fat, and BMI (baseline BMI: 38.1 ± 9.3 vs 7 mo BMI: 37.2 ± 7.9); no changes in control groupd | 83% of MST families attended treatment (although l.4 sessions per week rather than 2–3 as designed), whereas no families completed 10-wk Shapedown program | Targeting multiple systems and including the family in a more intensive treatment could be effective. | Low |

| Naar-King et al58 (2016)e | n = 181; 13.8 ± 1.4 y; female sex: 67%; African American: 100% | Adolescents randomly assigned to 3 mo of (1) HB-MIS, (2) OB-MIS; rerandomly assigned for next 3 mo; nonresponders randomly assigned to (1) CS, (2) CM; responders assigned to relapse prevention | Both groups: parents integrated into all sessions and involved in targeting relevant skills and supporting their adolescent’s behavior change; CM (nonresponders): parents received vouchers for delivering adolescent incentives, attending sessions, and monitoring youth’s daily weigh-ins | 6 mo | HB-MIS and OB-MIS both reduced wt from 0 to 6 mo and reduced %OW by 2.96%; there were no group differences. For nonresponders, both CM and CS participants reduced wt in phase 2, with no differences between conditions. | Greater family attendance was observed in HB-MIS. Those receiving home-based treatment in phase 1 were more likely to be retained in phase 2 compared with those who received office-based treatment. Those receiving CM in phase 2 attended more sessions than those receiving CS. | Because both conditions involved families in treatment but did not assess parent or family variables, it is unclear what role the caregivers had in contributing to wt loss | Low |

| Campbell-Voytal et al59 (2018)c,e | n = 136; 13 y; female sex: 69%; African American: 100% | See Naar-King et al58 2016 | See Naar-King et al58 2016 | 6 mo | Families with the most wt loss worked together, had high adolescent motivation, and continued caregiver support. | Families with parents trying to influence change rather than collaborate with adolescents had less successful wt loss. | Parental collaboration, persistence, encouragement, and support of autonomy are critical to adolescent success. | Low |

| Jacques-Tiura et al60 (2019)c,e | n = 164; 13.64–13.86 ± 1.29–1.41 y; female sex:74.4%–60.4%; African American: 100% | See Naar-King et al58 2016 | See Naar-King et al58 2016 | 6 mo | Greater use of wt loss skills was associated with a greater reduction in %OW at 6 mo; no difference in wt loss skill use at 6 mo on wt change at 9-mo follow-up | Greater attendance was associated with greater use of wt loss skills, with no group differences in use of wt loss skills at 6 mo. | Attendance in treatment is important for increasing wt loss skill use. Greater wt loss skill use can improve wt outcomes during the treatment period. | Low |

| Naar et al61 (2019)c,e | n = 181; 14.3 ± 1.4 y; female sex: 67%; African American: 100% | See Naar-King et al58 2016 | See Naar-King et al58 2016 | 6 mo | Adolescents with higher baseline confidence had greater reduction in %OW, regardless of group. When baseline confidence was low, reduction in %OW was greater in the CM group than the CS group. Older adolescents had greater reduction in %OW for CM compared to CS, and vice versa for younger adolescents. | N/A | Higher baseline confidence appears advantageous for wt loss success. Older adolescents or those with lower baseline confidence may do better with an incentive-based treatment program. | Low |

| Patrick et al62 (2013) | n = 101; 14.3 ± 1.5 y; female sex: 63.4%; white: 18%, African American: 16%, American Indian: 1%, Asian American: 4%, mixed race: 3%, other or unknown: 58% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) W, (2) WG, (3) WSMS, (4) UC | W, WG, and WSMS: parents completed adult version of Web site–based program and Web site–based monthly group sessions; WG parents had follow-up calls and participated in group counseling aimed at skill building to support their adolescent’s behavior goals; parents did not receive calls or text messages | 12 mo | No significant time or treatment effects on BMIz; all treatment arms reduced sedentary behavior, but compared with UC group, adolescents in W group showed greatest decreases (from 4.9 to 2.8 h/d) | None reported | N/A | Low |

| Resnicow et al63 (2005) | n = 123; 13.6 ± 1.4 y; female sex: 100%; African American: 100% | 10 churches with adolescent participants were randomly assigned to (1) high-intensity LMP with weekly behavioral group sessions over 6 mo, plus a 1-d retreat, 4–6 MI calls, and a pager that sent reminders; (2) moderate-intensity LMP with 6 monthly behavioral group sessions and no calls or pagers | Both groups: parents invited to attend every other LMP session with adolescents; they met separately for half of the session and then joined daughters for PA and snack | 6 mo | At 6 and 12 mo, no group differences in ΔBMI; adolescents who attended >75% of sessions reduced BMI more than those with <75% attendance | None reported | N/A | Unclear |

| Saelens et al64 (2002) | n = 44; 14.2 ± 1.2 y; female sex: 40.9%; white: 71%, Hispanic: 16%, African American: 5%, Asian American: 2%, mixed race: 7% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) LMP (HH), (2) single session of physician wt counseling (TC) | HH: parents received information sheets in mail that promoted support of adolescent behavior change at the same intervals as when adolescents participated in manualized sessions; TC: parent in the session | 4 mo | Significant group time interaction from 0 to 4 mo; BMIz decreased for HH adolescents and increased for TC adolescents; ΔBMIz stable through 7 mo; no 0- to 7-mo group differences in ΔBMIz | None reported | N/A | Low |

| Savoye et al65 (2007) | n = 209; 11.9–12.4 ± 2.5–2.3 y (age range: 8–16 y); female sex: 56%–68%; white: 38%–39%, African American: 38%–39%, Hispanic: 24%–26% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) Brighter Bodies LMP, an intensive family-based program; (2) control, clinical wt management counseling every 6 mo | Brighter Bodies: parents attended nutrition classes together with adolescents, with separate parent behavioral modification classes; parents encouraged to be weighed; control: parents attended their child’s obesity clinic visits and helped with goal setting | 12 mo | Adolescents in Brighter Bodies decreased BMI (−1.7 vs 1.6), percentage body fat, and total body fat at 12 mo, compared with controls; controls increased BMI, body wt, percentage body fat, and total body fat at 12 mo. | None reported | Family-based program is beneficial for BMI reduction, but it is unknown how parental involvement is related to study outcomes. | Unclear |

| St George et al66 (2013) | n = 73; 12.5 ± 1.5 y; female sex: 60%; African American: 100% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) Project SHINE, an interactive parent-based LMP; (2) control, general health education (weekly health content, no behavioral strategies provided) | Parents attended all sessions; Project SHINE: parents learned communication skills to support adolescent behavioral change; control: parents received general health content and did not receive any parenting strategies | 6 wk | No significant between-group differences in adolescent ΔBMIz | Neither parent-adolescent communication nor parental monitoring was associated with adolescent ΔBMIz. Project SHINE families increased health behavior communication and reduced adolescent SB; families with more positive communication had less adolescent SB than those with less positive communication | Parental communication about health behaviors appears to be related to adolescent SB. | Low |

| Steele et al67 (2012) | n = 93; 11.6 ± 2.6 y (age range: 7–17 y); female sex: 59.1%; white: 71%, African American: 14%, Hispanic: 4.3%, mixed race: 4.3%, other or unknown: 6.5% | Children and adolescents randomly assigned to LMP: (1) PF intervention, (2) BFI | PF: parents attended separate sessions for nutrition and/or PA education and behavioral components; joined together with child or adolescent for summary and goal setting; BFI: parents attended 3 visits with their child or adolescent led by a registered dietitian and received a self-help manual | 10 wk | Children and adolescents in both groups had BMIz reductions at post intervention and follow-up (−0.12 and −0.19 BMIz units); there were no group differences. Subgroup analyses revealed across conditions that children (7–12 y) had greater outcomes than adolescents (13–17 y) | None reported | N/A | Unclear |

| Wadden et al36 (1990) | n = 47; 13.8 y; female sex: 100%; African American: 100% | All adolescents received group LMP, randomly assigned to (1) CA, (2) MCT, (3) MCS | CA: adolescents encouraged to discuss treatment with parents; MCT: parents attended all sessions with adolescents, optional parent weekly weigh-ins; MCS: parents met separately for a manualized parent group, received weekly reading and homework assignments that were focused on parental support and monitoring | 16 wk | Adolescent wt loss was observed across conditions, with greater (not significant) wt loss in MCT and MCS groups; at follow-up, 54% of adolescents were below the baseline BMI and 46% were above the baseline BMI; across conditions mother attendance was positively correlated with adolescent wt loss | None reported | Maternal involvement appeared to be beneficial in short-term adolescent wt loss, regardless of format | Low |

| White et al68 (2004) | n = 57; 13.9 ± 1.4 y; female sex: 100%; African American: 100% | Adolescents randomly assigned to (1) HIP-Teens, family-based Internet LMP; (2) Internet control, general nutrition | Both groups: parents had separate logins to access study Web site to complete activities | 6 mo | Adolescents in HIP-Teens lost more body fat (−1.0 ± 2.0) than control adolescents (0.38 ± 3.0) at 6 mo. | Parent variables related to life and family satisfaction were strongest mediators of adolescent wt loss. | Greater parent family and life satisfaction related to body fat decrease in behavioral condition suggests that family climate influences intervention success. | Unclear |

| Williamson et al69 (2005)c | See White et al68 (2004) | See White et al68 (2004) | See White et al68 (2004) | 6 mo | Group differences in Δ%BMI; Δwt approached significance (P = .057 and .055, respectively), favoring HIP-Teens | Parents in HIP-Teens lost more wt than controls at 6 mo (2.78 kg); parent and adolescent Web site usage were correlated; adolescent and parent participants in HIP-Teens had greater Web site usage. | When parents are more engaged in treatment, adolescents may be more engaged. | Unclear |

| Williamson, et al70 (2006)c | See White et al68 (2004) | See White et al68 (2004) | See White et al68 (2004) | 6 mo | By 24 mo, parents and adolescents had gained wt, and there were no differences between conditions. | Adolescent baseline body wt was a significant covariate for body wt change in parents. Parents in HIP-Teens lost more body wt than control parents at 6 and 12 mo but not at 18 and 24 mo. | N/A | Unclear |

ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; BFI, brief family intervention; BMIz, BMI z score; CA, child alone; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; CBT + EXER, cognitive behavioral therapy with exercise; CBT + PEAT, cognitive behavioral therapy with peer-enhanced adventure therapy; CM, contingency management; CS, continued skills; FB, family-based lifestyle modification program; HB-MIS, home-based motivational interviewing skills; HH, Healthy Habits; HIP-Teens, Health Improvement Program for Teens; LCD, low-calorie diet; LMP, lifestyle modification program; MCS, mother and child separate; MCT, mother and child together; MI, motivational interviewing; MR, meal replacement; MST, multisystemic therapy; N/A, not applicable; NP, no parent participation; OB-MIS, office-based motivational interviewing skills; PA, physical activity; PCP, primary care physician; PF, Positively Fit; PO, parent-only lifestyle modification program; PP, parent participation; SB, sedentary behavior; SBT, standard behavioral treatment; SBT + EP, standard behavioral treatment and lifestyle modification program plus enhanced parenting; SHINE, supporting health interactively through nutrition and exercise; TC, typical care; UC, usual care; W, lifestyle modification program delivered via Web site; WG, lifestyle modification program delivered via Web site, monthly in-person group session, and follow-up calls; WLC, wait list control; WSMS, lifestyle modification program delivered via Web site and SMS texts; %BMI, BMI percentile; %OW, percentage overweight; ΔBMI, change in BMI; ΔBMIz, change in BMI z score; Δ%BMI, change in BMI percentile; Δwt, change in weight.

Adolescent.

Risk of bias based on the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool.

Studies from a trial previously included in the table (the trial directly above the entry); reported separately if distinct outcomes related to parents were reported or if the follow-up duration or outcomes differed.

Results were based on within-group, rather than between-group, analyses.

Study was a sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trial, rather than a traditional randomized controlled trial, and was included in this review given that randomization occurs at each stage and resembles many aspects of a traditional randomized controlled trial.

Overall Description of Included Studies

Most trials contained <100 participants (n = 31–209). In all but 1 trial,64 the majority of adolescent participants were female (∼60%–80%); 5 trials only enrolled girls.36,45,55,63,68 In 11 trials,* the majority of participants were white (55%–100%); in 8 trials,36,40,46,57,58,63,66,68 the majority of participants were African American (in 7 trials, only African Americans were enrolled).

Most interventions had a 4- to 6-month treatment duration.† The remaining had a treatment duration of <4 months56,66,67 or 1 year.40,42,47,62,65 Twelve trials had no follow-up to assess weight loss maintenance.‡ Of the trials that did assess maintenance, follow-up periods varied at 3,64 6,36,45,48,49,63 8,51 9,44 and 1243,56,67 months in duration.

All of the interventions included a lifestyle modification program targeting diet and exercise behaviors to promote healthy weight loss. Studies varied in their description of the adolescent intervention, but most described using self-monitoring,§ stimulus control,‖ and problem-solving or goal setting¶ to promote behavior change. Other behavioral strategies included relapse prevention and/or maintenance,49,51,53,65,67 stress management,40,42,49,53,66 contingency management,40,42,65 cognitive restructuring or managing beliefs about weight loss,40,42,43,53,57,65 depression management,45 promoting social support,40,42,43,45,55,62,64,67 managing cravings,53,57,58 use of incentives and/or rewards,36,44,46,58,64,67 sleep education,66 and addressing disordered eating or promoting a healthy body image.45,53

BMI was the most common variable used to measure adolescent treatment outcomes, yet it was operationalized in different ways across studies, including change in BMI percentage,40,42 BMI,36,47,51,57,63,65,69 and BMI z score.45,47,48,55,62,64,66,67 A few studies that reported BMI outcomes also reported kilograms of weight lost36,69 and/or body composition, body fat percentage, or other measures of adiposity.57,65,68,69 Studies that did not report BMI outcomes tended to report change in weight (kilograms or percentage) instead,43,49,56 whereas one trial reported percentage change in overweight as the primary outcome.58 In 11 trials, intervention group differences in weight outcomes were found,# and in 1 trial, a trend for group differences on BMI reduction was found.53 In 10 trials, no intervention group differences in weight outcomes were found,** but of these, 6 trials resulted in weight loss for all study groups.36,42,47,51,58,67

Description of Parent Involvement

Intervention Format

In some trials (n = 8), the intervention was delivered to parents and adolescents separately,40,44,45,48,51,53,56,68 and in other trials (n = 6), parents and adolescents were together in joint group sessions.46,47,55,57,58,66 In fewer trials (n = 4), 1 experimental condition was tested with joint group sessions and another experimental condition was tested with separate sessions for parents and adolescents.36,42,43,64 Five trials included at least 1 experimental condition in which parents and adolescents attended both separate and joint group sessions; for example, parents and adolescents attended separate group sessions each week, with joint dyad meetings biweekly.49,62,63,65,67

Behavioral Techniques Involving Parents

All studies listed the behavioral components or strategies taught to parents, but few described them in detail. These parent behavioral techniques included managing the home environment (eg, limiting high-calorie and/or high-fat foods in the home, increasing family meals),36,40,42,45,47,53 parental role modeling of health behaviors,36,40,42,44,65 positive reinforcement of weight loss goals and behaviors,††activities to improve adolescent-parent communication,53,55–57,66 and involving parents in shared decision-making,55 conflict resolution,55 and goal setting.48,55,65,67,68 Some interventions taught parents the same content that adolescents were learning so parents could support their adolescent and reduce potential barriers.36,45,49,51,58,62,63 Parent group sessions also provided opportunities for parents to discuss successes, concerns, and coping strategies and to receive peer support.36,42,43,55 The direct associations between parent behavioral techniques and adolescent weight outcomes were examined in few studies (Table 1); thus, possible mechanisms of action cannot be inferred. Among the trials that found between- and/or within-group differences on adolescent weight loss, the parent behavioral strategies used included positive reinforcement,36,40,42,49,53,64 managing the home environment,36,40,42,45,47,51 goal setting,48,65,67,68 parent-adolescent communication,51,56,57 role modeling,36,40,42,44,65 teaching parents the same content as adolescents,36,45,49,53,58 and parent group sessions to discuss successes, concerns, and coping strategies and to provide peer support.36,42,43 Of note, many of these same strategies (eg, goal setting, positive reinforcement, and activities to improve parent-adolescent communication) were also used in the trials that did not find significant differences on adolescent weight outcomes.55,62,63,66

Parent Outcome Measures

Of the 23 unique trials, 9 did not report any parent-related outcome measures.36,42,44,45,62–65,67 Six trials reported parent weight-related outcomes, such as change in parent weight or BMI41,43,48,52,53,69; half of these trials found significant decreases in parent weight or BMI, and half did not. There was no clear pattern in the behavioral strategies used for trials that resulted in parent weight loss versus trials that did not. In addition, of the 6 studies that measured parent weight, 2 studies found significant associations between parent and adolescent change in BMI over the intervention period,41,52 2 studies found no significant association,43,48 and 2 studies did not measure associations between parent and adolescent change in BMI.53,69

Other parent-related outcome variables reported included family dynamics (eg, family encouragement, nurturance, conflict, and communication)46,50,54,55,59,66 and treatment adherence or satisfaction.49,56–58 For example, adolescents with greater weight loss reported having higher levels of self-motivation and noted that their family members worked with each other to mutually adopt new behaviors.59 Adolescents with less weight loss reported that parents tried to influence change (eg, force, pushing) and that parents were less engaged in the behavioral intervention (eg, not interested, inconsistent).59 Surprisingly, one study found that a decline in parent-adolescent communication quality was related to better adolescent weight outcomes for those receiving a standard behavioral treatment,54 although St George et al66 found no association between parent-adolescent communication and adolescent weight change.

Interventions That Manipulated the Role of Parents

We highlight here the 5 trials that experimentally manipulated the role of parents, given their greater scientific rigor with respect to our central research questions, which enhances confidence in conclusions drawn regarding parent involvement in adolescent obesity treatment.36,43,44,48,53

Brownell et al43 and Wadden et al36 both tested a similar lifestyle management program delivered 3 ways: (1) to adolescents only, (2) to mother-adolescent dyads in joint group sessions, and (3) to mother-adolescent dyads in separate but concurrent group sessions. Brownell71 developed this intervention and delivered it to a sample of white adolescents,43 whereas Wadden et al36 adapted the intervention for Black adolescents. Brownell et al43 found that adolescents had greater weight loss when the intervention was delivered to mother-adolescent dyads in separate but concurrent group sessions, concluding that the nature of the parental involvement mattered. In contrast, Wadden et al36 found no differences in child weight loss between groups (with significant weight losses observed in all 3 groups). Moreover, the mother’s attendance appeared to be more important than the format, such that superior weight losses were observed among girls whose mothers had better attendance (in either treatment arm) compared with girls whose mothers had low or no (eg, child-alone group) attendance. Although different sample demographics might explain these discrepant findings, Wadden et al36 posited that the dynamics of the mother-child joint group sessions could also explain these differences; Brownell et al43 reported that mothers and adolescents in joint group sessions were “reluctant to voice negative feelings about the problems of dealing with each other,” whereas Wadden et al36 reported that mother-child joint group sessions tended to be “more animated, fun, and supportive than were meetings [with children alone or mothers alone]” and that “children and mothers appeared comfortable together in the same group.” Importantly, both samples were small (fewer than 38 individuals in the analysis samples, with no intent-to-treat analyses conducted), limiting generalizability. Similarly, both Janicke et al48 and Coates et al44 tested lifestyle management programs delivered to parent-adolescent dyads (in joint sessions or in separate sessions, respectively) versus delivery just to adolescents44 or just to parents.48 In both studies, the involvement of both parents and adolescents, rather than just one of these groups individually, resulted in greater adolescent weight loss post treatment, suggesting that involving parents in obesity treatment is beneficial. Specifically, in post hoc analyses, Janicke et al48 reported that parent-only treatment was superior for children <11 years, with combined treatment yielding greater weight loss for adolescents ≥11 years.

In contrast to the trials described above, Jelalian et al53 manipulated intervention content such that one group received a standard behavioral treatment, whereas the other group received the same treatment with an enhanced parenting component. The enhanced parenting component was intended to increase parental modeling and build parent-adolescent communication skills around adolescent weight control. Adolescent BMI decreased in both groups, yet there was a trend for greater BMI reduction and a significant decrease in maternal negative commentary among adolescents who received the standard behavioral treatment rather than behavioral treatment with an enhanced parenting component. These findings suggest that emphasizing parent-adolescent communication around weight might not be an effective behavioral strategy for adolescent weight loss. However, given the small pilot nature of this study, additional research into parent-adolescent communication is warranted.

Discussion

This review has identified and described lifestyle interventions for adolescent obesity treatment that involved parents. Across studies, there was a clear shortage of details regarding parents’ specific involvement in treatment and few assessments of parent outcomes. These challenges, coupled with the lack of diversity in participant demographics, the variety of intervention formats, and different adolescent weight variables, make it difficult to determine the optimal role of parents in adolescent weight loss treatment. As such, we discuss the results in the context of 5 important areas for future research that offer promise in clarifying parents’ optimal role in adolescent weight management. These include vital needs for (1) manipulating experimentally the role of parents, (2) providing greater detail on parents’ specific involvement in treatment and their adherence, (3) including assessments of specific parent variables (eg, parent role modeling of eating and exercise behaviors, parenting style, feeding style, and weight), (4) examining the associations between parent-related factors and adolescent weight outcomes, and (5) conducting additional trials with larger, more diverse samples and longer follow-up periods.

Only 5 RCTs experimentally manipulated the role of parents in adolescent obesity treatment.36,43,44,48,53 Most of these trials delivered the same intervention to all experimental groups while manipulating the target of the intervention (parent, adolescent, or both). Although some evidence suggests that parental involvement might result in greater adolescent weight loss compared to interventions that included parents or adolescents alone,44,48 the small sample sizes of most of these studies renders findings inconclusive. Moreover, there is even less clarity about the optimal format of parental engagement.36,43 These findings are consistent with existing clinical recommendations citing the need for the involvement of both parents and adolescents in adolescent obesity treatment.6,13 Similar findings were reported in a meta-analysis of children aged 2 to 18 years that demonstrated small treatment effects for interventions involving parents, whether targeted individually or with the child, compared with interventions without parental involvement.9 However, findings of the current study differ from those of a recent overview of 6 Cochrane reviews, which synthesized evidence on overweight and obesity treatment among children and adolescents, including interventions targeting behavior change, pharmacotherapy, and/or surgery.72 This review concluded that parental involvement in obesity treatment of children 12 years and older did not significantly alter the overall effect estimates on weight outcomes.72 These discrepant findings might be due to the variety of treatment approaches (eg, pharmacotherapy and surgical obesity treatment) included in the Cochrane review,72 compared to the current review’s exclusive focus on behavioral lifestyle interventions. It is important to note that how parents are involved in obesity treatment likely plays a significant role in outcomes. Based on the studies included in this review, the optimal intervention format (parent-adolescent separate group sessions versus joint group sessions) remains unclear,36,43 and intervention content emphasizing parent-adolescent communication around weight appeared ineffective in reducing adolescent weight loss in a small pilot study.53 With only a handful of studies on which to base these conclusions, it is apparent that more robust RCTs that manipulate the ways in which parents are involved in adolescent obesity treatment are needed. It is also important to note that in this review, we examined studies that involved parents, but we did not systematically compare studies that included parents with those that did not. In future studies, investigators could consider directly comparing RCTs involving parents with those that do not do so to assess support for clinical recommendations.

Most trials in this review did not describe in detail how parents were involved in treatment or include measures of parents’ adherence, making it challenging to draw conclusions regarding the relative impact of specific behavioral techniques on adolescent weight loss. Clinical guidelines recommend parents’ involvement in adolescent obesity treatment through strategies such as monitoring, limit setting, reducing barriers, managing family conflict, and modifying the home environment.13 These behavioral techniques were used in some studies included in this review, in addition to other strategies, such as positive reinforcement of adolescent weight loss goals, shared decision-making, and goal setting. Interventions using these parenting approaches generally revealed significant reductions in adolescent BMI, yet without direct assessment of the specific parent-related behavioral strategies, it cannot be determined if these specific interventions are effective in modifying these behaviors (or, subsequently, if these parent behaviors are related to adolescent weight loss). Of the trials included in this review, ∼40% did not include any parent-related outcome measures, similar to an earlier review of adolescent obesity interventions.32 This previous review also highlighted a lack of specific measures of parental involvement.32 Moving forward, it is important to determine which parent-related behavioral strategies are effectively targeted and modified within obesity interventions. As such, we recommend that future interventions include specific assessments of parent-related behavioral strategies (eg, stimulus control, feeding styles, and role modeling) and an examination of how these strategies relate to treatment outcomes.

Previous research among younger children has shown that parent weight change is associated with child weight change during family-based obesity treatments,31,73–75 yet far less is known about this association in the adolescent population. In this review, only ∼20% (n = 4) of unique trials quantified associations between parent and adolescent weight change, and findings were mixed (revealing both positive and null associations). Most interventions did not include parent weight loss as a specific intervention target; rather, parents were encouraged to support their adolescents’ weight loss goals and behaviors. Two studies did report that adolescent weight loss was greater when parents also lost weight.41,52 Perhaps these associations were due to factors such as parental role modeling of positive weight loss behaviors (eg, self-monitoring by using food logs),52 environmental changes in the home, and/or greater parental motivation and commitment to the intervention. For example, 3 studies in this review found that when parents were more engaged in treatment (ie, greater attendance or Web site usage), adolescents were also more engaged.36,56,69 These findings identify directions for future research examining parent weight loss and/or engagement for impact on adolescent weight loss within controlled trials.

This review is limited by the inability to conduct a meta-analysis,76 given the limited number of studies identified and the diverse nature of investigations addressing our specific research question, no a priori registered protocol, and concerns regarding the generalizability to trials conducted internationally or among non–English-speaking cultures. This review is strengthened by its focus on a unique, understudied population (ie, adolescents) that has been previously combined with younger children or not included at all in obesity treatment review articles. We conducted a comprehensive search to identify high-quality studies (RCTs), with at least 2 independent reviewers assessing all possible articles for inclusion criteria. We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines37 and rated each article for risk of bias using a standardized tool.38,39

Conclusions

The optimal approach to involving parents in adolescent obesity treatment is unclear because few RCTs have experimentally manipulated parent involvement. There are many opportunities for additional research to clarify the role of parents in adolescent behavioral weight loss trials. In future investigations, researchers should thoroughly describe how parents are involved in obesity treatment, measure parents’ adherence to intervention strategies, assess specific parent-related behavior change techniques and outcomes, and examine associations between parent and adolescent weight outcomes. Such efforts will yield knowledge that can appropriately inform clinical guidelines and ultimately improve the health and well-being of this vulnerable population.

Glossary

- RCT

randomized controlled and/or clinical trial

Footnotes

Dr Bean conceptualized and designed the study (including determination of inclusion and exclusion criteria), conducted a critical review of literature, performed quality assessments, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Adams, Ms Burnette, and Dr Caccavale conducted the systematic review of the literature and determined which studies met inclusion and exclusion criteria, extracted the data and performed quality assessments, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Mazzeo, LaRose, Raynor, and Wickham conceptualized and designed the study and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (R21HD084930 and R01HD095910 to Dr Bean and 2T32CA093423 to Virginia Commonwealth University). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. . Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2292–2299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss R, Dziura J, Burgert TS, et al. . Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2362–2374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li S, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, et al. . Childhood cardiovascular risk factors and carotid vascular changes in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. JAMA. 2003;290(17):2271–2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loria CM, Liu K, Lewis CE, et al. . Early adult risk factor levels and subsequent coronary artery calcification: the CARDIA Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(20):2013–2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrison JA, Friedman LA, Wang P, Glueck CJ. Metabolic syndrome in childhood predicts adult metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus 25 to 30 years later. J Pediatr. 2008;152(2):201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiess W, Galler A, Reich A, et al. . Clinical aspects of obesity in childhood and adolescence. Obes Rev. 2001;2(1):29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorof J, Daniels S. Obesity hypertension in children: a problem of epidemic proportions. Hypertension. 2002;40(4):441–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(13):869–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGovern L, Johnson JN, Paulo R, et al. . Clinical review: treatment of pediatric obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(12):4600–4605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H, et al. . Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD001872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shrewsbury VA, Steinbeck KS, Torvaldsen S, Baur LA. The role of parents in pre-adolescent and adolescent overweight and obesity treatment: a systematic review of clinical recommendations. Obes Rev. 2011;12(10):759–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llabre MM, Ard JD, Bennett G, et al. ; Guideline Development Panel (GDP) for Obesity Treatment of the American Psychological Association (APA). Clinical practice guideline for multicomponent behavioral treatment of obesity and overweight in children and adolescents: current state of the evidence and research needs. 2018. Available at: https://www.apa.org/about/offices/directorates/guidelines/obesity-clinical-practice-guideline.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2020

- 13.Spear BA, Barlow SE, Ervin C, et al. . Recommendations for treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2007;120(suppl 4):S254–S288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo SS, Wu W, Chumlea WC, Roche AF. Predicting overweight and obesity in adulthood from body mass index values in childhood and adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(3):653–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wickham EP, Stern M, Evans RK, et al. . Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among obese adolescents enrolled in a multidisciplinary weight management program: clinical correlates and response to treatment. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009;7(3):179–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen AK, Roberts CK, Barnard RJ. Effect of a short-term diet and exercise intervention on metabolic syndrome in overweight children. Metabolism. 2006;55(7):871–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monzavi R, Dreimane D, Geffner ME, et al. . Improvement in risk factors for metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in overweight youth who are treated with lifestyle intervention. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/117/6/e1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitzmann KM, Dalton WT III, Stanley CM, et al. . Lifestyle interventions for youth who are overweight: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. 2010;29(1):91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLean N, Griffin S, Toney K, Hardeman W. Family involvement in weight control, weight maintenance and weight-loss interventions: a systematic review of randomised trials. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(9):987–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brennan L, Walkley J, Wilks R. Parent- and adolescent-reported barriers to participation in an adolescent overweight and obesity intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(6):1319–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmbeck GN. A Model of Family Relational Transformations during the Transition to Adolescence: Parent-Adolescent Conflict and Adaptation In: Graber JA, Brooks-Gun J, Petersen AC, eds.. Transitions Through Adolescence: Interpersonal Domains and Contexts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996:167–199 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faith MS, Van Horn L, Appel LJ, et al. ; American Heart Association Nutrition and Obesity Committees of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease . Evaluating parents and adult caregivers as “agents of change” for treating obese children: evidence for parent behavior change strategies and research gaps: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(9):1186–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Locard E, Mamelle N, Billette A, Miginiac M, Munoz F, Rey S. Risk factors of obesity in a five year old population. Parental versus environmental factors. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1992;16(10):721–729 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher JO, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL. Parental influences on young girls’ fruit and vegetable, micronutrient, and fat intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(1):58–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wardle J, Carnell S, Cooke L. Parental control over feeding and children’s fruit and vegetable intake: how are they related? J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(2):227–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faith MS, Berkowitz RI, Stallings VA, Kerns J, Storey M, Stunkard AJ. Parental feeding attitudes and styles and child body mass index: prospective analysis of a gene-environment interaction. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/114/4/e429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faith MS, Scanlon KS, Birch LL, Francis LA, Sherry B. Parent-child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obes Res. 2004;12(11):1711–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sleddens EF, Gerards SM, Thijs C, de Vries NK, Kremers SP. General parenting, childhood overweight and obesity-inducing behaviors: a review. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(2–2):e12–e27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang J, Matheson BE, Rhee KE, Peterson CB, Rydell S, Boutelle KN. Parental control and overconsumption of snack foods in overweight and obese children. Appetite. 2016;100:181–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindsay AC, Sussner KM, Kim J, Gortmaker S. The role of parents in preventing childhood obesity. Future Child. 2006;16(1):169–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boutelle KN, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, French SA. Fast food for family meals: relationships with parent and adolescent food intake, home food availability and weight status. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(1):16–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nichols M, Newman S, Nemeth LS, Magwood G. The influence of parental participation on obesity interventions in African American adolescent females: an integrative review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(3):485–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niemeier BS, Hektner JM, Enger KB. Parent participation in weight-related health interventions for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2012;55(1):3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golley RK, Hendrie GA, Slater A, Corsini N. Interventions that involve parents to improve children’s weight-related nutrition intake and activity patterns - what nutrition and activity targets and behaviour change techniques are associated with intervention effectiveness? Obes Rev. 2011;12(2):114–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelly SA, Melnyk BM. Systematic review of multicomponent interventions with overweight middle adolescents: implications for clinical practice and research. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2008;5(3):113–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, Rich L, Rubin CJ, Sweidel G, McKinney S. Obesity in black adolescent girls: a controlled clinical trial of treatment by diet, behavior modification, and parental support. Pediatrics. 1990;85(3):345–352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds.. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.0.1. London, United Kingdom: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. ; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group . The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA, Gehrman CA, et al. . Meal replacements in the treatment of adolescent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19(6):1193–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xanthopoulos MS, Moore RH, Wadden TA, Bishop-Gilyard CT, Gehrman CA, Berkowitz RI. The association between weight loss in caregivers and adolescents in a treatment trial of adolescents with obesity. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(7):766–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berkowitz RI, Rukstalis MR, Bishop-Gilyard CT, et al. . Treatment of adolescent obesity comparing self-guided and group lifestyle modification programs: a potential model for primary care. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(9):978–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brownell KD, Kelman JH, Stunkard AJ. Treatment of obese children with and without their mothers: changes in weight and blood pressure. Pediatrics. 1983;71(4):515–523 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coates TJ, Killen JD, Slinkard LA. Parent participation in a treatment program for overweight adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 1982;1(3):37–48 [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeBar LL, Stevens VJ, Perrin N, et al. . A primary care-based, multicomponent lifestyle intervention for overweight adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/129/3/e611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ellis DA, Janisse H, Naar-King S, et al. . The effects of multisystemic therapy on family support for weight loss among obese African-American adolescents: findings from a randomized controlled trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(6):461–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fleischman A, Hourigan SE, Lyon HN, et al. . Creating an integrated care model for childhood obesity: a randomized pilot study utilizing telehealth in a community primary care setting. Clin Obes. 2016;6(6):380–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janicke DM, Sallinen BJ, Perri MG, et al. . Comparison of parent-only vs family-based interventions for overweight children in underserved rural settings: outcomes from project STORY. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(12):1119–1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jelalian E, Mehlenbeck R, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Birmaher V, Wing RR. ‘Adventure therapy’ combined with cognitive-behavioral treatment for overweight adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006;30(1):31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jelalian E, Hart CN, Mehlenbeck RS, et al. . Predictors of attrition and weight loss in an adolescent weight control program. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(6):1318–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jelalian E, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Mehlenbeck RS, et al. . Behavioral weight control treatment with supervised exercise or peer-enhanced adventure for overweight adolescents. J Pediatr. 2010;157(6):923–928.e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sato AF, Jelalian E, Hart CN, et al. . Associations between parent behavior and adolescent weight control. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(4):451–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jelalian E, Hadley W, Sato A, et al. . Adolescent weight control: an intervention targeting parent communication and modeling compared with minimal parental involvement. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(2):203–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hadley W, McCullough MB, Rancourt D, Barker D, Jelalian E. Shaking up the system: the role of change in maternal-adolescent communication quality and adolescent weight loss. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(1):121–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kitzman-Ulrich H, Hampson R, Wilson DK, Presnell K, Brown A, O’Boyle M. An adolescent weight-loss program integrating family variables reduces energy intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(3):491–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mellin LM, Slinkard LA, Irwin CE Jr.. Adolescent obesity intervention: validation of the SHAPEDOWN program. J Am Diet Assoc. 1987;87(3):333–338 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naar-King S, Ellis D, Kolmodin K, et al. . A randomized pilot study of multisystemic therapy targeting obesity in African-American adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(4):417–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Naar-King S, Ellis DA, Idalski Carcone A, et al. . Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART) to construct weight loss interventions for African American adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45(4):428–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Campbell-Voytal KD, Hartlieb KB, Cunningham PB, et al. . African American adolescent-caregiver relationships in a weight loss trial. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(3):835–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jacques-Tiura AJ, Ellis DA, Idalski Carcone A, et al. . African-American adolescents weight loss skills utilization: effects on weight change in a sequential multiple assignment randomized trial. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(3):355–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naar S, Ellis D, Idalski Carcone A, et al. . Outcomes from a sequential multiple assignment randomized trial of weight loss strategies for African American adolescents with obesity. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(10):928–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patrick K, Norman GJ, Davila EP, et al. . Outcomes of a 12-month technology-based intervention to promote weight loss in adolescents at risk for type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7(3):759–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Resnicow K, Taylor R, Baskin M, McCarty F. Results of go girls: a weight control program for overweight African-American adolescent females. Obes Res. 2005;13(10):1739–1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Wilfley DE, Patrick K, Cella JA, Buchta R. Behavioral weight control for overweight adolescents initiated in primary care. Obes Res. 2002;10(1):22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Savoye M, Shaw M, Dziura J, et al. . Effects of a weight management program on body composition and metabolic parameters in overweight children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2697–2704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.St George SM, Wilson DK, Schneider EM, Alia KA. Project SHINE: effects of parent-adolescent communication on sedentary behavior in African American adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(9):997–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Steele RG, Aylward BS, Jensen CD, Cushing CC, Davis AM, Bovaird JA. Comparison of a family-based group intervention for youths with obesity to a brief individual family intervention: a practical clinical trial of positively fit. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37(1):53–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.White MA, Martin PD, Newton RL, et al. . Mediators of weight loss in a family-based intervention presented over the internet. Obes Res. 2004;12(7):1050–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williamson DA, Martin PD, White MA, et al. . Efficacy of an internet-based behavioral weight loss program for overweight adolescent African-American girls. Eat Weight Disord. 2005;10(3):193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williamson DA, Walden HM, White MA, et al. . Two-year internet-based randomized controlled trial for weight loss in African-American girls. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(7):1231–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]