The Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak in 2015 was an unprecedented challenge to academic medical centres in the Republic of Korea. It involved 186 confirmed cases and 38 fatalities across the country, and notably, nearly half of the cases were nosocomial infections [1]. This tragic outbreak led to a call for fundamental changes in the Korean health-care system to prepare for potential infectious disease outbreaks in the future [2,3]. Academic medical centres set out to transform their environment with two major goals of (i) preparedness for emerging infectious diseases, and (ii) reduction of nosocomial infections [4]. Here we describe an example of a major academic institution, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (SNUBH), focusing on three key aspects of preparedness: renovating infrastructure, training health-care professionals and constructing a community-based response system to infectious disease outbreaks.

Renovating infrastructure

On 1 September 2016, the national health insurance in Korea introduced a new policy providing reimbursements for hospitals equipped with infection control and prevention measures meeting new standards. Eligible hospitals could be reimbursed at a per diem rate for every inpatient. The rate was determined by the number of infection control nurses per inpatient bed (one per 150 beds for tier 1, one per 200 beds for tier 2) [5]. To meet the tier 1 reimbursement policy, SNUBH newly hired qualified personnel to increase the number from three full-time and two part-time staff to nine full-time staff. They developed hospital protocols for responding to emerging infectious diseases, conducted surveillance of nosocomial infections, and educated hospital staff. An enhanced workforce improved the hospital's capacity for nosocomial infection control and pandemic preparedness.

Another important change was the installation of high-level isolation units (HLIUs) [6]. Because of the ever-increasing trend of international travel and immigration, there was an urgent need to renovate the hospital infrastructure to prepare for novel infectious diseases without compromising the health and safety of the health-care workers. SNUBH leadership formed a new task force in February 2016 to develop HLIUs. A total of nine single-patient rooms were installed by August 2017. All rooms were designed to generate a negative pressure environment to minimize nosocomial transmissions amidst a highly transmissible disease outbreak. Five of those were also equipped to provide critical care including mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The costs of installing HLIUs were partly funded by the government through the initiative of the Korea Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) for nationally designated isolation units. As of 2019, there were a total of 535 beds within nationally designated isolation units in 29 hospitals nationwide, established through this initiative. Among them, 198 beds were in negative pressure isolation units, including nine at SNUBH [7].

To guide the clinical management of patients with highly contagious diseases in HLIUs, the infection control office of the hospital developed an in-house protocol with the aim of preventing secondary transmissions of pathogens. To develop this, infection control officers reviewed relevant KCDC protocols and adapted them through discussions with a multidisciplinary group of hospital staff. Additionally, they defined an organizational structure in which members of the Infectious Control Task Force would be activated in times of active infectious disease threats with predefined roles to enable organized decision-making and to facilitate effective communication. Furthermore, the infection control office stratified the hospital's responses according to the level of the national alert system for infectious diseases (Table 1 ). Detailed practice manuals—for example, environment and waste management and close contact management—were also developed to be readily applicable in epidemic situations. For intra- and inter-hospital HLIU patient transfers, patient flows were specified in order to minimize the transmission risks to other patients and hospital staff. An entrance was also designated for exclusive use for transporting patients requiring HLIUs or contaminated materials. The first version of the protocol was approved by the Medical Executive Committee at SNUBH, enacted in August 2017, and updated on a yearly basis (see Supplementary material, Table S1).

Table 1.

Hospital response protocols by the national alert level for infectious diseases

| National alert levels | Hospital response |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Departments in charge of infectious disease control | Infectious diseases control task force | Management of patient with EIDs | Control of the hospital entrances | Education and training of all hospital staff | Promotion of infection control measures | Mobilization of health-care workers and resources | |

|

Attention (Blue) EIDs overseas with no immediate threat of importation |

|

||||||

|

Caution (Yellow) Domestic importation of EIDs from abroad |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alert (Orange) Confined spread of EIDs within the country |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Serious (Red) Spread of EIDs in communities across the country |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: EIDs, emerging infectious diseases; HLIU, high-level isolation units; PPE, personal protective equipment.

The screening stations at the hospital entrances are aimed to screen patients and visitors for symptoms related to EIDs (e.g. fever, respiratory symptoms) or epidemiological risk factors (e.g. recent travel history to an endemic region) to prevent any unprepared entry into the hospital. Suspected people are triaged to the screening clinic, a temporary facility located outside the main hospital building, for further evaluation for EID.

Lastly, to protect the health-care workers caring for patients in the HLIUs, SNUBH procured a large supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) through coordination with the Korean government. This step was prompted by the hospital's experiences of admitting patients suspected of having Ebola or MERS, prior cardiopulmonary resuscitations in HLIUs, and PPE training for hospital staff.

Training health-care workers

SNUBH introduced multiple new education programmes to enhance health-care workers' understanding and preparedness for emerging infectious diseases. A new session entitled ‘Responding to emerging infectious diseases’ was added to the mandatory education programme for all hospital employees. In addition, PPE training programmes were conducted regularly. Every PPE training session included a demonstration of PPE donning and doffing and hands-on exercises. Participants practiced as a pair, using a fluorescent solution to evaluate the degree of contamination during the PPE doffing procedure. Basic supplies of this training included an N95 respirator and a set of level D PPE (defined by the KCDC), which comprised a waterproof coverall with an attached hood, goggles, inner and outer gloves, and shoe covers. An advanced training session was performed with powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs) or level C PPE, comprising chemically resistant clothing and eye protection. Since the first regular PPE training held on 18 January 2017, SNUBH provided 1191 days of staff training between 2017 to 2019, and nearly 40% of the training included the use of PAPRs (see Supplementary material, Table S2). The PPE training was particularly emphasized for clinical staff taking care of patients in HLIUs. Physicians and nurses were required to have completed the PPE training in the previous 6 months in order to work at HLIUs. Staff involved in critical care at HLIUs were also required to participate in annual trainings with PAPRs.

Furthermore, simulation exercises were developed to prepare for complex clinical situations and were first conducted in August 2017, including a clinical scenario of an admission of a patient with MERS-CoV to the HLIU. Participants practiced wearing full sets of PPE, entering a negative pressure room, managing clinical problems, and safely taking off PPEs upon exiting the room. Three months later, the hospital started a biannual multidisciplinary workshop with simulation exercises and subsequent evaluations. Based on feedback, the hospital improved its clinical protocols and equipment, and simulated multiple clinical situations, including an inpatient outbreak from secondary transmission, patient triage and management in the emergency department, cardiopulmonary resuscitation of infected patients, and managing the remains of infected patients who died in the hospital. In 2019, the workshop was expanded into a joint workshop with other neighbouring hospitals in the province that had nationally designated isolation units.

The clinical workforce harnessed experience accumulated from treating patients suspected of MERS-CoV and viral haemorrhagic fevers (137 and 6 patients from 2017 to 2019, respectively). Before the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, patients suspected of emerging infectious diseases were treated in HLIUs, regardless of disease severity. The hospital continuously improved training and preparedness protocols to reflect the lessons learned.

Community-based response network in collaboration with the provincial government

Finally, SNUBH helped to establish a network among other hospitals and governmental agencies to cope with the massive outbreak [8]. SNUBH took on the responsibility of leading the infection control initiatives in Gyeonggi-do, a densely populated province with 13 million residents surrounding metropolitan Seoul. SNUBH initiated the first provincial Gyeonggi-do Infectious Disease Control Centre (GIDCC) in April 2014, accredited by the Gyeonggi provincial government and the KCDC. During the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa, GIDCC held simulation exercises with multiple stakeholders, based on a clinical scenario of an Ebola outbreak. These pre-emptive preparations and drills helped Gyeonggi-do to respond to individuals with MERS-CoV during the outbreak in 2015. For example, the province rapidly created a bed allocation system by disease severity, which was a new strategy developed during the outbreak to isolate all patients through risk stratification. In Gyeonggi-do, two hospitals were designated for the treatment of individuals with MERS. While coordinating the GIDCC, SNUBH focused on treating patients with severe clinical presentations of MERS. Meanwhile, a public community hospital took charge of individuals with less severe disease. Through local collaboration, the Gyeonggi province was able to contain the MERS-CoV cases efficiently in its area.

Since then, SNUBH continued to provide support for infection control in the community. Infection control education programmes were held for staff at long-term care facilities, school nurses and infection control nurses at local hospitals. SNUBH worked with public health authorities and other hospitals to reassess and promote provincial preparedness for infectious disease threats following the MERS outbreak. This long-term collaboration paved the way for better communication and collaboration among key parties (hospitals, local governments and communities) that ultimately allowed a rapid activation of the regional response system when the current COVID-19 pandemic began [9,10].

COVID-19 response and conclusion

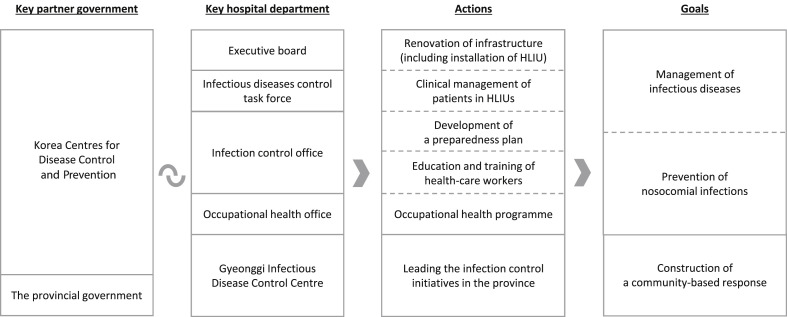

Five years after the MERS-CoV outbreak, Korea was hit by the COVID-19 pandemic in January 2020. Both Korean government and hospitals were better prepared than in 2015 (Fig. 1 ). Since SNUBH admitted Korea's first suspected COVID-19 patient on 7 January 2020, more than a hundred confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases have been treated in the hospital. Through the regional triage system, SNUBH primarily provided advanced care for critically ill COVID-19 patients while moderately ill patients were admitted to the dedicated community hospital. SNUBH also took care of mildly ill patients who were admitted at the Gyeonggi Community Treatment Centre, a repurposed non-medical facility, from 19 March to 29 April 2020. By enacting strict isolation and triage protocols, SNUBH has had no reported cases of nosocomial severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 transmission and has not had to halt the care of non-COVID-19 patients. The timeline of pandemic preparations and the COVID-19 response in South Korea and SNUBH, along with the distribution of admitted patients across different levels of service, are summarized in the Supplementary material (Fig. S1) and Table 2 , respectively.

Fig. 1.

Pandemic preparedness of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. The infectious diseases control task force consists of an executive board, a clinical management team (Department of Infectious Diseases, Respiratory Diseases, Emergency Medicine, and Paediatrics), an infection control team (infection control physicians and nurses, and the occupational health office), a clinical support team (departments of laboratory, radiology, pharmacology and nutrition), a nursing team and an administrative team. HLIU, high-level isolation units.

Table 2.

COVID-19 response of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital: goals, actions and outcomes

| Goals | Actions | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Identify, isolate and report early cases | Identification and report

|

|

| Keep the health-care system functioning for pandemic and non-pandemic patients |

|

|

| Reduce the risk of pandemic acute respiratory infection transmission associated with health care |

|

|

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CTC, community treatment centre; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Note. Goals in the left column were adapted from Infection prevention and control of epidemic-and pandemic-prone acute respiratory infections in health care, by WHO (2014).

Since the MERS-CoV outbreak, many academic medical centres in Korea have taken an active role in not only preparing their facilities and staff, but also their communities and regional governments, allowing the country as a whole to effectively tackle the current wave of COVID-19. Although the level of community spread in Korea has been relatively moderate because of widespread testing, rigorous contact tracing and mandatory quarantine, current efforts will be maintained to prepare for potential future outbreaks of COVID-19. As countries overcome surges and probably face future waves, academic medical centres around the world can continue to take up a similar mantle of preparation, innovation, training, critical care and community leadership.

Transparency declaration

All authors have stated that there are no conflicts of interest to declare. No funding was received for this study.

Authors' contributions

JA-RA and K-HS contributed equally to this work. JA-RA, K-HS, ESK, J-HK, AB and HBK conceived the study. K-HS, ESK, JJ, JYP, JSP, HL, MJS, HYL, SL, KUP and HBK collected data. JA-RA, K-HS, ESK, RK and J-HK wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version for submission.

Editor: L. Leibovici

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.032.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Oh M.D., Park W.B., Park S.W., Choe P.G., Bang J.H., Song K.H. Middle East respiratory syndrome: what we learned from the 2015 outbreak in the Republic of Korea. Kor J Intern Med. 2018;33:233–246. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.OECD. OECD . OECD Publishing; Paris: 2020. Reviews of public health: Korea: A healthier tomorrow. [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeong E.K. Public health emergency preparedness and response in Korea. J Kor Med Assoc. 2017;60:296–299. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014 March. Infection prevention and control of epidemic- and pandemic-prone acute respiratory infections in health care.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK214351/ [Internet] Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health and Welfare Notification No. 2016-152, The Republic of Korea (in Korean).

- 6.Bannister B., Puro V., Fusco F.M., Heptonstall J., Ippolito G., EUNID Working Group Framework for the design and operation of high-level isolation units: consensus of the European Network of Infectious Diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:45–56. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70304-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2019. Protocol for the nationally designated isolation units. (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee V.J., Aguilera X., Heymann D., Wilder-Smith A., Lee V.J., Heymann D.L. Preparedness for emerging epidemic threats: a lancet infectious diseases commission. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:17–19. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30674-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh J., Lee J.K., Schwarz D., Ratcliffe H.L., Markuns J.F., Hirschhorn L.R. National response to COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea and lessons learned for other countries. Health Syst Reform. 2020 doi: 10.1080/23288604.2020.1753464. published online 29 April. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ariadne Labs COVID-19 Global Learning: South Korea Team . Ariadne Labs; Boston: 2020 May. Global learnings evidence brief: protecting health care workers in South Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic.https://covid19.ariadnelabs.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2020/05/Ariadne-Labs-Global-Learnings-Evidence-Brief-Protecting-Health-Care-Workers-in-South-Korea.pdf [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.