Significance

Ubiquitylation affects many important cellular processes and has been linked to a number of human diseases. It has become a synonym for protein degradation, but ubiquitylation also has important nonproteolytic signaling functions. Understanding the molecular concepts that govern ubiquitin signaling is of great importance for development of diagnostics and therapeutics. The cadmium-induced inactivation of the SCFMet30 ubiquitin ligase via the disassembly of the multisubunit ligase complex illustrates an example for nonproteolytic signaling pathways. Dissociation is triggered by autoubiquitylation of the F-box protein Met30, which is the recruiting signal for the highly conserved AAA-ATPase Cdc48/p97. Here we show that the UBX cofactor Shp1/p47 is important for this ubiquitin-dependent active remodeling of a multiprotein complex in response to a specific environmental signal.

Keywords: SCF-Met30, Cdc48/p97, Shp1

Abstract

Organisms can adapt to a broad spectrum of sudden and dramatic changes in their environment. These abrupt changes are often perceived as stress and trigger responses that facilitate survival and eventual adaptation. The ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) is involved in most cellular processes. Unsurprisingly, components of the UPS also play crucial roles during various stress response programs. The budding yeast SCFMet30 complex is an essential cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase that connects metabolic and heavy metal stress to cell cycle regulation. Cadmium exposure results in the active dissociation of the F-box protein Met30 from the core ligase, leading to SCFMet30 inactivation. Consequently, SCFMet30 substrate ubiquitylation is blocked and triggers a downstream cascade to activate a specific transcriptional stress response program. Signal-induced dissociation is initiated by autoubiquitylation of Met30 and serves as a recruitment signal for the AAA-ATPase Cdc48/p97, which actively disassembles the complex. Here we show that the UBX cofactor Shp1/p47 is an additional key element for SCFMet30 disassembly during heavy metal stress. Although the cofactor can directly interact with the ATPase, Cdc48 and Shp1 are recruited independently to SCFMet30 during cadmium stress. An intact UBX domain is crucial for effective SCFMet30 disassembly, and a concentration threshold of Shp1 recruited to SCFMet30 needs to be exceeded to initiate Met30 dissociation. The latter is likely related to Shp1-mediated control of Cdc48 ATPase activity. This study identifies Shp1 as the crucial Cdc48 cofactor for signal-induced selective disassembly of a multisubunit protein complex to modulate activity.

The maintenance of protein homeostasis is crucial for eukaryotic cells. The posttranslational modification of a protein by ubiquitin conjugation was first described as the major nonlysosomal mechanism by which proteins are targeted for degradation (1). However, destruction of proteins via the proteasomal pathway is only one of many outcomes of ubiquitylation. The fate of a protein is decided depending on how many ubiquitin molecules are covalently attached and in which fashion ubiquitin chains are formed. The outcomes can be versatile, and, for example, influence abundance, activity, or localization of proteins (2–5). The process of ubiquitin conjugation requires the coordinated reaction of the E1–E2–E3 enzyme cascade. E3 ligases mediate the final step of substrate-0specific conjugation (6–8). E3s are the most diverse components in the ubiquitylation machinery and are divided in several classes. The largest group is represented by the multisubunit cullin-RING ligases (CRLs), which include the well-studied subfamily of SCF (Skp1-cullin-F-box) ligases (9, 10). SCFs are composed of four principal components: the RING finger protein Rbx1, the scaffold Cul1, and the linker Skp1 that forms an association platform with different substrate-specific F-box proteins (11, 12).

The punctual degradation of several SCF substrates is essential to ensure normal cell growth. Hence, alterations in SCF component expression or function can often be linked to cancer and other diseases (13, 14). This highlights the importance to better understand SCF ligase regulation and enable their therapeutic targeting. It has long been thought that ubiquitylation by SCF ligases is solely regulated at the level of substrate binding (11, 15). However, an additional mode of CRL regulation was recently discovered. Specific SCF ligases can be inhibited by signal-induced dissociation of the F-box subunit from the core ligase (16, 17). The best studied example is SCFMet30, which controls ubiquitylation of a number of different substrates (16, 18–20). The transcriptional activator Met4 and the cell-cycle inhibitor Met32 are the most critical ones. Together they orchestrate induction of cell cycle arrest and activation of a specific transcriptional response during nutritional or heavy metal stress. This stress response protects cellular integrity, restores normal levels of sulfur-containing metabolites, and activates a defense system for protection against heavy metal stress (18, 21–25). Under normal growth conditions, SCFMet30 mediates Met4 and Met32 ubiquitylation. Even though both are modified with the classical canonical destruction signal, a lysine-48–linked ubiquitin chain, only Met32 is degraded via the proteasomal pathway. In contrast, Met4 is kept in an inactive state by the attached ubiquitin chain (19, 26). Both nutrient and heavy metal stress block SCFMet30-dependent ubiquitylation of Met4 and Met32, but through profoundly distinctive mechanisms. Nutrient stress prevents the interaction between the SCFMet30 ligase and its substrate following the canonical mode of regulation, but cadmium stress leads to active dissociation of the F-box subunit Met30 from the core ligase (21, 22). Remarkably, dissociation is initiated by autoubiquitylation of the F-box protein Met30, which serves as the recruiting signal for the conserved AAA-ATPase Cdc48/p97 (16). Importantly, ubiquitin-dependent recruitment of Cdc48 and dissociation of Met30 from the core ligase are independent of proteasome activity (16).

Cdc48 is involved in many diverse cellular pathways, including extraction of unfolded proteins from the ER (27, 28), discharge of membrane-bound transcription factors (29, 30), and chromatin-associated protein extraction (31–36). However, Cdc48 itself rarely displays substrate specificity. An ensemble of regulatory cofactors tightly controls functions of the ATPase by recruiting it to different cellular pathways (37–39). Shp1 (Suppressor of High copy protein Phosphatase 1 or p47 in mammals) is part of the UBA-UBX family of Cdc48 cofactors (40). The UBA domain binds ubiquitin, with a preference for multiubiquitin chains (41, 42), and the UBX domain is structurally similar to ubiquitin and directly interacts with Cdc48 by mimicking a monoubiquitylated substrate (43–46). An additional domain, the SEP (Shp1/Eyeless/P47) domain, is involved in trimerization of the cofactor (47, 48). N-terminal of the UBX domain, a short hydrophobic sequence in Shp1 represents an additional Cdc48 binding motif (BS1), which enables a bipartite mode of Shp1 binding to Cdc48 (39, 44, 46, 49).

In yeast, Shp1 is involved in Cdc48-dependent protein degradation via the UPS (43). The Cdc48Shp1 complex also interacts with the ubiquitin-fold autophagy protein Atg8 and is a component of autophagosome biogenesis (50). The best studied function of Shp1 relates to activation of protein phosphatase 1 (Glc7), which is important for cell cycle progression (51, 52). Hence, deletion of Shp1 leads to a severe growth phenotype, and cells are prone to genomic instability (43, 52, 53). Here we show that Shp1 is the crucial Cdc48 cofactor for SCFMet30 disassembly in response to heavy metal stress. We identified the very C-terminal 22 amino acids to be important for disassembly. Surprisingly, Cdc48 and Shp1 get independently recruited to SCFMet30 during cadmium stress, and recruitment depends on SCFMet30 autoubiquitylation. Furthermore, initiation of SCFMet30 disassembly is triggered by an Shp1 threshold level likely necessary for stimulating ATP hydrolysis by Cdc48 (54).

Results

Shp1 Is Involved in the Cellular Response during Cadmium Stress.

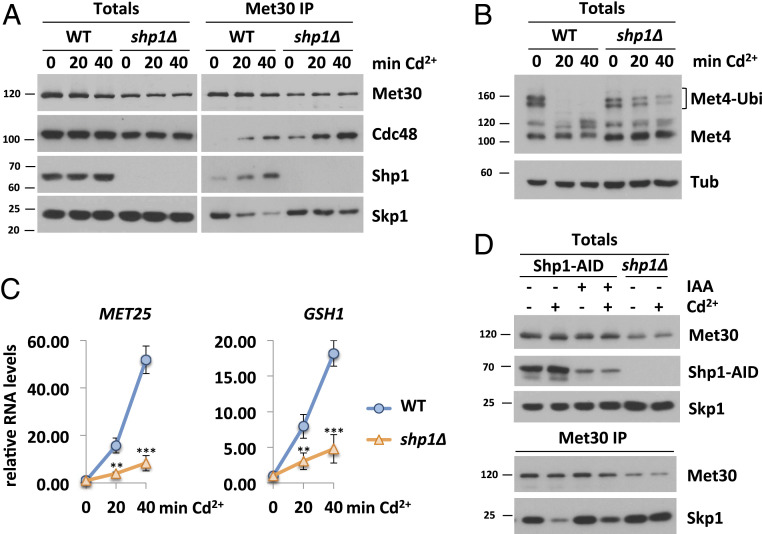

The distinct functions of Cdc48/p97 in diverse cellular processes are tightly controlled by a large number of cofactors (38). For mechanical reasons, Cdc48 requires at least two anchor points to generate physical force and make Met30 dissociation possible. We reasoned that deletion of a cofactor necessary for SCFMet30 disassembly would result in cadmium sensitivity because defense pathways would not be activated. Deletion of SHP1 rendered yeast cells cadmium-sensitive (16, 43), and we therefore considered Shp1 as a potential cofactor for SCFMet30 disassembly. This hypothesis was supported by immunoprecipitation experiments of Met30 that showed Cdc48 and Shp1 are recruited to SCFMet30 in response to cadmium exposure (Fig. 1A). We have previously demonstrated that Met30 dissociates rapidly from Skp1 concomitant with Cdc48 recruitment to SCFMet30 when cells are exposed to cadmium (16) (Fig. 1A). In shp1∆ deletion mutants, Met30 dissociation kinetics were severely delayed. Additionally, the amount of Cdc48 in complex with Met30 in the absence of Shp1 was significantly increased even under unstressed growth conditions, and accumulated to even higher levels during cadmium stress (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Increased Cdc48 binding suggests that the dissociation complex intermediate is trapped in shp1∆ mutants, and, importantly, that Shp1 is not required for Cdc48 recruitment, but to trigger Cdc48-catalyzed Met30 dissociation (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A).

Fig. 1.

Shp1 is involved in the cellular response during cadmium stress. (A) Shp1 is recruited to SCFMet30 during cadmium stress. Dissociation kinetics of Met30 from the SCF core ligase are decreased in shp1∆ deletion mutants (K.O.). Strains expressing endogenous 12xMycMet30, Cdc48RGS6H, Skp1, and Shp13xHA in WT or shp1∆ cells were cultured at 30 °C in YEPD medium and treated with 100 µM CdCl2, and samples were harvested at indicated time points. 12xMycMet30 was immunoprecipitated, and coprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blot. (B) Shp1 is necessary for Met4 activation during heavy metal stress. Whole-cell lysates (Totals) of samples shown in Fig. 1A were analyzed by Western blot using a Met4 antibody to follow the ubiquitylation and phosphorylation status of Met4. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) Cadmium-induced gene expression is altered in the absence of Shp1. RNA was extracted from samples shown in Fig. 1A. Expression of Met4 target genes MET25 and GSH1 was analyzed by RT-qPCR and normalized to 18S rRNA levels (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SD (t test *P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01). (D) Temporal down-regulation of Shp1 shows its importance during cadmium stress. Strains expressing endogenous 12xMycMet30, Shp13xHA-AID, and the F-Box protein 2xFLAGOsTir under the constitutive ADH promoter were cultured at 30 °C in YEPD medium in the absence and presence of 500 µM auxin for 4 h to deplete endogenous Shp1. Cells were treated with 100 µM cadmium, and samples were harvested after 20 min of heavy metal exposure. 12xMycMet30 was immunoprecipitated, and coprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blot. Results shown in A, B, and D are representative blots from three independent experiments.

Under normal growth conditions, SCFMet30 facilitates the ubiquitylation of Met4 and thereby represses the cadmium-related stress response (21, 22). Cadmium-triggered dissociation of Met30 leads to SCFMet30 inhibition and thereby blocks Met4 ubiquitylation, leading to cell cycle arrest and induction of the transcription of glutathione and sulfur amino acid biosynthesis-regulating genes (25). Consistent with Shp1 requirement for SCFMet30 disassembly, Met4 remained ubiquitylated during cadmium stress in shp1∆ mutants (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the lack of Met4 activation in the absence of Shp1 is reflected in blunted cadmium-induced Met4 target gene activation (Fig. 1C). These results and cadmium hypersensitivity of shp1∆ cells (16, 43) suggest that Shp1 is critical for the Met4-mediated cadmium stress program.

However, Shp1 is essential for normal mitotic progression, and shp1∆ mutants grow very slowly (ref. 52 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B) or are inviable in certain genetic backgrounds (43). Thus, as with all mutations that severely compromise cell proliferation, we were concerned that shp1∆ deletion strains acquired compensatory mutations that could lead to misinterpretation of results (55). Therefore, we decided to use the auxin-inducible degron (AID) system (56, 57) to acutely down-regulate Shp1 protein levels. Auxin (IAA) mediates the interaction of the F-box protein Tir1 and an AID-tagged protein, leading to the ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of the AID-tagged substrate. Shp1 was tagged with a 3×HA-AID-fragment and coexpressed with OsTir in the presence of IAA. Within 30 min of IAA supplementation, Shp1-AID levels were significantly decreased (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). Even though Shp1 levels were severely down-regulated for several hours, no significant growth defect was observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D), indicating that the remaining Shp1 amount was enough to fulfill its function in mitotic progression, or that genomic instability associated with shp1∆ mutants leads to accumulation of growth-inhibiting mutations over time. We compared cadmium-induced Met30 dissociation between shp1∆ deletion mutants and auxin-mediated knockdown strains. When Shp1 levels were low (<10% of endogenous amount), cadmium-induced Met30 dissociation was compromised. Although this dissociation phenotype was not as pronounced as in the complete absence of Shp1 (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1E), these results confirm an important role of Shp1 in SCFMet30 disassembly during heavy metal stress.

Mutation of Functional Domains in Shp1.

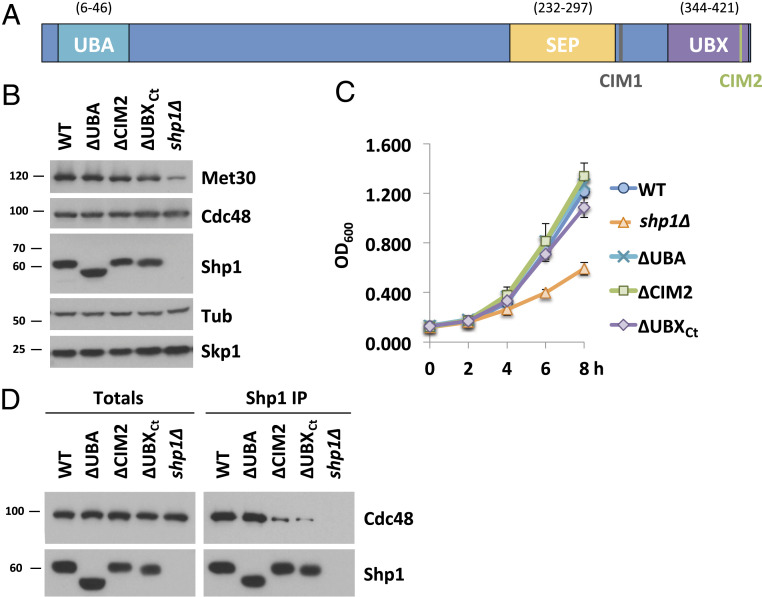

Several conserved functional domains have been characterized in Shp1 and its mammalian ortholog p47 (39). These include the UBA and UBX domains that characterize this family of Cdc48 cofactors. We wanted to evaluate the importance of these domains and the role of Shp1/Cdc48 interaction for SCFMet30 disassembly. The crystal structure of p97 bound to p47, the human orthologs of yeast Cdc48 and Shp1, respectively, has been reported (48). Several regions of p47 contact p97 in this structure. Most notably, the S3/S4 loop (residues 342 to 345 in p47 and 396 to 398) located in the UBX domain inserts into a hydrophobic pocket formed between two p97 N subdomains. Additional contacts are formed by evolutionarily conserved residues at the very C terminus of p47 (48). Furthermore, we deleted another evolutionarily conserved region (residues 304 to 314 in Shp1) referred to as binding site 1 (BS1) or SHP box, a motif that mediates binding of other proteins to Cdc48 (49, 52, 58, 59). To simplify the nomenclature, we refer to BS1 as Cdc48 interacting domain 1 (CIM1), to the S3/S4 loop as CIM2, and to the last 22 residues of Shp1 as UBXCt (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). The latter two binding elements are embedded in the UBX domain, but mutation of one element does not interfere with integrity of Cdc48 binding ability through the other element. All mutations were generated at the endogenous locus by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing. The CIM1 mutation was generated by deleting residues 304 to 314 and the CIM2 mutation by changing the important FPI sequence to GAG. As previously reported (52), mutation of either the CIM1, CIM2, or UBXCt severely reduced steady-state interaction of endogenous proteins with Cdc48, while deletion of the UBA domain had no effect (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S2E). Mutant Shp1 proteins were expressed at similar levels, and, in contrast to shp1∆ deletion mutants, none of the mutant strains showed substantial growth defects (Fig. 2 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 C and D). We noticed significantly reduced Met30 levels in shp1∆ mutants, which was not observed in any of the domain mutations (Fig. 2B). Met30 protein stability was not affected, but shp1∆ mutants showed reduced MET30 RNA expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 F and G). The reason for the expression effect is unknown.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of functional domains in Shp1. (A) Schematic of Shp1 and its known functional domains and motifs. UBA, ubiquitin-associated domain (6 to 46); SEP, Shp1, eyeless and p47 domain (238 to 313); UBX, ubiquitin regulatory X domain (346 to 420); CIM 1, Cdc48-interacting motif 1 (LGGFSGQGQRL; 304 to 314 distal of SEP domain, also known as BS1); CIM2, Cdc48-interacting motif 1 (FPI; 396 to 398 in the UBX domain). (B) Expression levels of Shp1 mutants. Steady-state levels of indicated proteins were compared from strains expressing endogenous 12xMycMet30, Cdc48RGS6H, Skp1, and the various Shp1 mutants as indicated (all 3×HA-tagged). ∆UBA, deletion of residues 1 to 50; ∆CIM2, 396 to 398 FPI residues were replaced with GAG; ∆UBXCt, deletion of aa 401 to 423 or shp1 gene knocked out (K.O.). Proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with tubulin as a loading control. (C) Shp1 mutants do not show a significant growth defect at 30 °C. Wild-type cells, shp1 mutant variants as indicated, and shp1∆ (K.O.) strains were grown at 30 °C in YEPD medium, and samples were taken at indicated time points to measure optic density at 600 nm. (D) Cdc48 binding is significantly decreased in ∆CIM2 and ∆UBXCt Shp1 mutants. SHP13xHA variants were immunoprecipitated, and coprecipitation of Cdc48RGS6H was analyzed by Western blotting. The Shp1 K.O. strain was used as a background control. Results shown in B and D are representative blots from three independent experiments.

The UBX Domain of Shp1 Is Required for SCFMet30 Disassembly during Cadmium Stress.

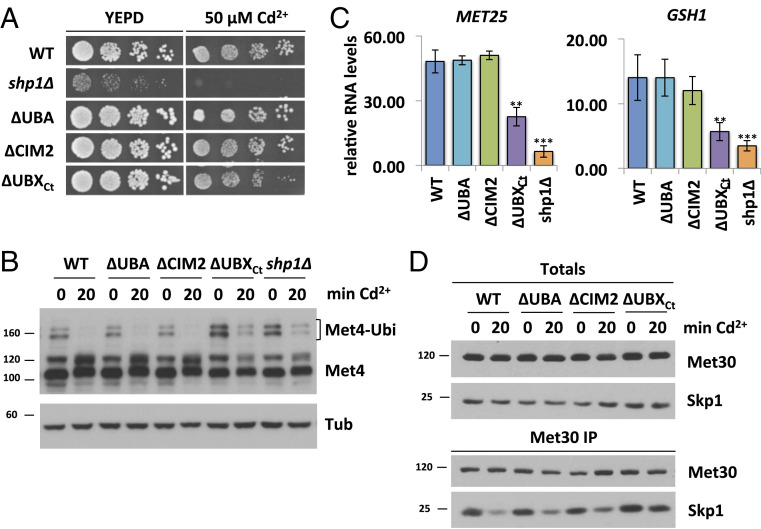

We next analyzed the impact of different Shp1 mutants on the response to cadmium stress. We focused these studies on Shp1∆CIM2, ∆UBA, and ∆UBXCt mutants because Shp1 with either ∆CIM1 and ∆CIM2 mutations showed identical behavior in initial experiments (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). As previously shown, the shp1∆ deletion mutants were hypersensitive toward cadmium exposure (16, 43) (Fig. 3A). ∆UBXCt mutants were also cadmium-sensitive, albeit only moderately, whereas all other Shp1 domain mutants tolerated cadmium exposure (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Cadmium sensitivity caused by defects in the SCFMet30 system is due to a lack of Met4 activation and the resulting blocked induction of a defense program mediated by Met4-dependent gene transcription. Met4 activation can be monitored by appearance of deubiquitylated Met4 and induction of genes such as MET25 and GSH1 in response to cadmium stress (16, 21, 22). These are sensitive indicators to monitor functionality of the SCFMet30 system. Consistent with the cadmium sensitivity assay, shp1∆ and ∆ubxCt mutants were unable to fully activate Met4 as demonstrated by maintained ubiquitylated Met4 during cadmium stress (Fig. 3B). All other Shp1 variants responded similarly to wild-type cells and completely blocked Met4 ubiquitylation (Fig. 3B). These findings were further confirmed by analysis of cadmium-induced expression of Met4 target genes. shp1-∆UBA and shp1-∆CIM2 showed induction of MET25 and GSH1 similarly to wild-type Met4. However, shp1-∆ubxCt mutants failed to efficiently activate gene expression, consistent with persistent Met4 ubiquitylation and cadmium sensitivity of this mutant (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

The UBX domain of Shp1 is required for SCFMet30 disassembly during cadmium stress. (A) shp1-∆UBXCt mutants are cadmium-sensitive. Indicated strains were cultured to logarithmic growth phase, cells were counted, and serial dilutions spotted onto YEPD plates supplemented with or without 50 µM CdCl2. Plates were incubated for 2 d at 30 °C. (B) The UBX domain is important for Met4 activation during heavy metal stress. Strains shown in Fig. 3A were cultured at 30 °C in YEPD medium and treated with 100 µM CdCl2 for 20 min. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using a Met4 antibody to follow the ubiquitylation and phosphorylation status of Met4. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) Insufficient Met4 activation in shp1-∆UBXCt mutants is reflected in MET25 and GSH1 RNA levels. Strains as indicated were grown at 30 °C in YEPD medium treated with 100 µM CdCl2, and samples were harvested after 40 min exposure. RNA was extracted, and expression of Met4 target genes MET25 and GSH1 was analyzed by RT-qPCR and normalized to 18S rRNA levels (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SD (t test *P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01). (D) shp1∆UBXCt mutants show altered dissociation kinetics during cadmium stress. 12xMycMet30 of lysates shown in Fig. 3B was immunoprecipitated, and copurified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. Results shown in B and D are representative blots from three independent experiments.

These experiments cannot distinguish between a general requirement of Shp1 for Met4 activation and the cadmium signal-specific pathway we propose. In addition to heavy metal stress, methionine starvation blocks Met4 ubiquitylation and induces a similar transcriptional response program (18). However, Met4 activation by methionine stress is achieved through disruption of the Met30/Met4 interaction and not by SCFMet30 disassembly (16, 22). Importantly, Met4 activation in response to methionine starvation was unaffected in shp1 mutants, demonstrating a specific requirement for Shp1 in the SCFMet30 disassembly pathway (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B and C).

We next directly evaluated cadmium-induced SCFMet30 disassembly in shp1 mutants. shp1-∆ubxCt mutants showed very slow Met30 dissociation, and the majority of Met30 remained in complex with the core ligase during heavy metal stress (Fig. 3D). In contrast, all other mutants were indistinguishable from wild-type cells (Fig. 3D). In summary, our results indicate that an intact UBX domain of Shp1 is required for SCFMet30 disassembly during cadmium stress. Importantly, even though both ∆CIM2 and ∆UBXCt mutants showed severely decreased Shp1 interaction with Cdc48 (Fig. 2C), only shp1-∆ubxCt mutants were deficient in SCFMet30 disassembly. Hence, the role of Shp1 in SCFMet30 during heavy metal stress is independent of a stable Cdc48–Shp1 interaction, but requires a specific contact between Cdc48 and Shp1 that is mediated by a contact interface at the very C terminus of Shp1.

Met30 Dissociation Kinetics during Heavy Metal Stress Are Dependent on Shp1 Abundance.

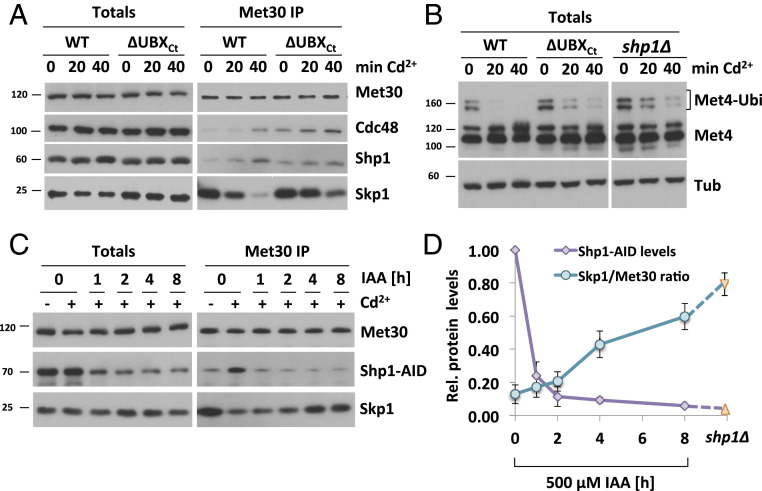

We next monitored Cdc48 and cofactor recruitment, as well as kinetics of SCFMet30 disassembly in the shp1-∆ubxCt mutant. Immunoprecipitated SCFMet30 formed a complex with Cdc48 and Shp1∆UBXCt even under unstressed growth conditions (Fig. 4A), further supporting that stable Cdc48–Shp1 binding is not required for recruitment of either. However, disassembly kinetics of SCFMet30 in shp1∆ and shp1-∆ubxCt mutants were severely delayed, demonstrating that physical separation of Met30 from the core SCF relies on Shp1, and specifically on its very C-terminal residues (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). The slow disassembly of SCFMet30 in shp1-∆ubxCt mutants is also reflected in delayed Met4 activation indicated by persisting Met4 ubiquitylation (Fig. 4B). Surprisingly, similar to shp1∆ deletion mutants, the amount of Cdc48 in complex with Met30 under unstressed growth conditions was significantly increased in shp1-∆ubxCt mutants (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). This increased steady-state binding of Cdc48 to SCFMet30 in shp1 mutants may be a result of the blocked dissociation and likely reflects accumulation of a dissociation intermediate (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). Furthermore, even though Shp1-∆UBXCt does not efficiently interact with Cdc48 (Fig. 2D), both Cdc48 and Shp1∆UBXCt are efficiently recruited to SCFMet30 (Fig. 4A), indicating that both proteins are independently recruited to SCFMet30. However, due to the higher steady-state binding of both Cdc48 and Shp1∆UBXCt in shp1-∆ubxCt mutants, the fold recruitment induced by cadmium stress was reduced for both proteins (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). This decreased enrichment was not due to partial loss of Cdc48 binding because Shp1∆CIM2, which shows a similar reduction in Cdc48 binding (Fig. 2D), was recruited to SCFMet30 at similar levels as wild-type Shp1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E). Importantly, despite the decreased fold enrichment, the total amount of bound Cdc48 during cadmium stress is significantly higher in shp1∆ and shp1-∆ubxCt mutants than wild-type cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D), likely a reflection of accumulation of the usually transient enzyme/substrate (SCFMet30/Cdc48) complex due to the blocked dissociation process. These results suggest that both Cdc48 and Shp1 are independently recruited to SCFMet30. However, their interaction through the C-terminal portion of the UBX domain on Sph1 is necessary to mediate Met30 dissociation.

Fig. 4.

Met30 dissociation during cadmium stress depends on Shp1 abundance. (A) Cadmium-induced recruitment of Shp1 to SCFMet30 is significantly decreased in ∆UBXCt mutants. Strains expressing endogenous 12xMycMet30, Cdc48RGS6H, Skp1, and Shp13xHA, or ∆UBXCt Shp13xHA, were cultured at 30 °C in YEPD medium treated with 100 µM CdCl2, and samples were harvested at indicated time points. Whole-cell lysates (Totals) were prepared, 12xMycMet30 was immunoprecipitated, and copurified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. (B) shp1-∆UBXCt mutants show delayed Met4 activation. Whole-cell lysates shown in Fig. 4A were analyzed by Western blotting using a Met4 antibody to follow the ubiquitylation and phosphorylation status of Met4. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) Met30 dissociation kinetics dependent on Shp1 abundance. Strains expressing endogenous 12xMycMet30, Shp13xHA-AID, and the F-Box protein 2xFLAGOsTir under the constitutive ADH promoter were cultured at 30 °C in YEPD medium in the absence and presence of 500 µM auxin for the indicated time to gradually down-regulate endogenous Shp1-AID levels. Cells were exposed to 100 µM CdCl2, and samples were harvested after 20 min. 12xMycMet30 was immunoprecipitated, and copurified Skp1 and Shp1-AID were analyzed by Western blotting. Results shown in A–C are representative blots from three independent experiments. (D) Densitometric analysis of Fig. 4C shows a correlation between Shp1-AID abundance and Met30 dissociation from the SCF core during cadmium stress. Purple line indicates densitometric analysis of Western blot band intensities of Shp1-AID totals. Time point 0 was set to 1. Turquoise line indicates coimmunoprecipitated Skp1 signals normalized to immunoprecipitated 12xMycMet30 signals to quantify F-box protein dissociation from the core ligase after 20 min of cadmium exposure. Orange triangles correspond to the values obtained from Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A, quantifications of shp1∆ mutants.

The human Shp1 homolog p47 has a concentration-dependent effect on Cdc48 activity (54). We therefore investigated if SCFMet30 bound Shp1 levels correlated with Met30 dissociation during cadmium stress, and whether blocked disassembly in shp1-∆ubxCt mutants was due to reduced Shp1∆UBXCt in the dissociation complex. The AID system enabled us to titrate Shp1 levels, ranging from endogenous to about 10-fold lower levels (Fig. 4C). Met30 dissociation was attenuated when Shp1-AID levels were decreased, revealing a correlation between Shp1 abundance and cadmium-induced SCFMet30 disassembly (Fig. 4D and SI Appendix, Fig. S4F). A significant dissociation defect was observed only when Shp1-AID levels were reduced by more than 75%. Importantly, Shp1∆UBXCt amounts recruited to the SCFMe30/Cdc48 complex are significantly above the Shp1 threshold level necessary for complete SCFMe30 disassembly (Fig. 4 A and C, 1 h IAA, and SI Appendix, Fig. S4H). Thus, the defect of Met30 dissociation observed in shp1-∆ubxCt mutants is not due to reduced Shp1∆UBXCt recruitment, but reflects requirement of UBX-mediated interaction with Cdc48 to stabilize the complex and trigger the dissociation process.

Shp1 Trimerization Regulates Met30 Dissociation during Heavy Metal Stress.

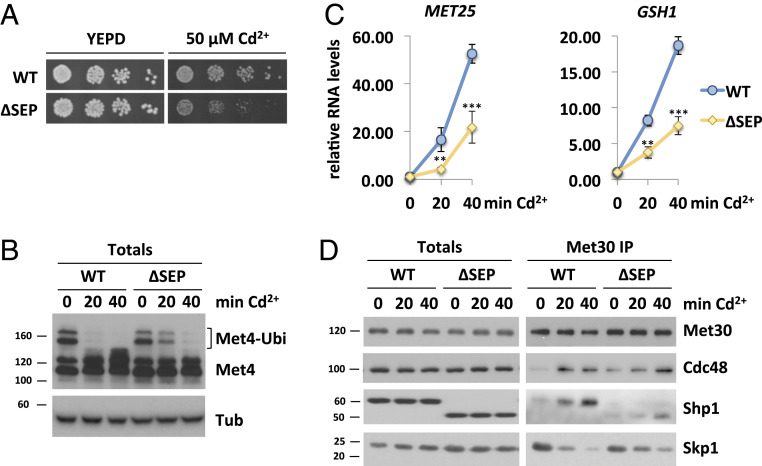

The ATPase activity of p97/Cdc48 can be influenced by its cofactors, and, initially, human p47 was described to inhibit p97 activity (60). Yet, a more recent study suggests that ATPase regulation by p47 is more complex. In vitro, p47 showed a biphasic regulation of p97 (54). ATPase activity was strongly inhibited at relatively low p47 concentration (phase 1). However, at higher stoichiometric amounts of the cofactor, ATPase activity was stimulated (phase 2). The authors suggest, that in phase 1, p47 is found as a monomer on p97, whereas phase 2 reaches maximum p97 activity when the majority of p47 is in the form of trimers (54). We hypothesized that, at low amounts, Shp1 facilitates maximum inhibition of Cdc48 ATPase activity. Upon cadmium exposure, Shp1 is recruited to SCFMet30, increasing the local concentration of the cofactor. This increase might lead to Shp1 trimerization and stimulation of ATP hydrolysis, followed by separation of Met30 from the core SCF. Hence, we next deleted the SEP domain (aa 232 to 297) required for the trimerization of the cofactor. Consistent with previous reports (61), the SEP domain is not important for Cdc48/Shp1 interaction (SI Appendix, Fig. S5G). Deletion of Shp1 leads to cadmium hypersensitivity (16, 43), and also the shp1-∆sep cells showed sensitivity toward cadmium exposure, indicating the importance of Shp1 trimerization (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Importantly, unlike shp1∆ cells under unstressed conditions, the trimerization mutants do not manifest a growth phenotype, demonstrating that the SEP domain deletion does not affect general Shp1 function (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). As mentioned earlier, cadmium sensitivity indicates a defect in the Met4-regulated transcriptional defense program. Indeed, upon heavy metal exposure, shp1-∆sep mutants did not show fully activated Met4, indicated by persistent Met4 ubiquitylation (Fig. 5B) and attenuated Met4 target gene response during cadmium stress (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, shp1-∆sep mutants did not show a defect in Met4 activation in response to methionine starvation, demonstrating a specific requirement of Shp1 trimerization for SCFMet30 regulation in response to cadmium (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). Consistent with these findings, dissociation of Met30 from the core ligase as well as Cdc48 and Shp1 recruitment in response to cadmium stress were severely delayed in the shp1-∆sep trimerization mutant. Similar to shp1∆ and shp1-∆ubxct, shp1-∆sep was deficient in SCFMet30 disassembly (Fig. 5D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5D). Under unstressed conditions, immunoprecipitated SCFMet30 formed a complex with Cdc48 and Shp1∆SEP. The fold enrichment of Shp1∆SEP into SCFMet30 is significantly decreased, most likely due to inability of trimerization of the cofactor (Fig. 5D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5E). Similar to shp1∆ and the c-terminal truncation mutants, the amount of Cdc48 in complex with Met30 in shp1-∆sep mutants was increased, and accumulated to even higher levels upon heavy metal exposure, indicating an accumulation of a usual transient intermediate state of the dissociation reaction (Fig. 5D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5F). Taken together, these results support that trimerization, and therewith local increase of the cofactor concentration on SCFMet30, might lead to Cdc48 ATPase stimulation necessary for active complex dissociation.

Fig. 5.

Shp1 trimerization regulates Met30 dissociation during heavy metal stress. (A) shp1-∆sep mutants indicate cadmium sensitivity. Strains expressing endogenous 12xMycMet30, Cdc48RGS6H, Skp1, and Shp13xHA, or ∆SEP Shp13xHA, were cultured to logarithmic growth phase, cells were counted, and serial dilutions spotted onto YEPD plates supplemented with or without 50 µM CdCl2. Plates were incubated for 2 d at 30 °C. (B) The SEP domain is necessary for Met4 activation during heavy metal stress. Whole-cell lysates (Totals) of strains shown in Fig. 5A were analyzed by Western blot using a Met4 antibody to follow the ubiquitylation and phosphorylation status of Met4. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) Decreased cadmium-induced gene expression in the absence of the SEP domain. RNA was extracted from samples shown in Fig. 5B. Expression of Met4 target genes MET25 and GSH1 was analyzed by RT-qPCR and normalized to 18S rRNA levels (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SD (t test *P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01). (D) Dissociation kinetics of Met30 from the SCF core ligase are decreased in shp1-∆sep mutants. Indicated strains were cultured at 30 °C in YEPD medium and treated with 100 µM CdCl2, and samples were harvested after 20 and 40 min, respectively. 12xMycMet30 was immunoprecipitated, and coprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blot. Results shown in B and D are representative blots from three independent experiments.

Discussion

Cdc48 is an exceptionally versatile protein, and substrate specificity is thought to depend on cofactors (38). During heavy metal stress, Cdc48 plays a critical role in signal-induced disassembly of the SCFMet30 ubiquitin ligase complex (16). Our results show that the UBA-UBX cofactor Shp1 is critical for this process. Like Cdc48, Shp1 is recruited into SCFMet30 upon cadmium exposure (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Interestingly, the prominent heterodimeric Ufd1/Npl4 cofactor pair also gets recruited to Met30 under heavy metal stress conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). However, temperature-sensitive ufd1-2 and npl4-1 mutants do not exhibit cadmium sensitivity, Met4 activation defects, or a dissociation phenotype during heavy metal stress (16). Likely cadmium-induced recruitment of Ufd1/Npl4 reflects their canonical function in this context and is necessary for targeting dissociated Met30 for degradation by the proteasome. Cadmium stress generates an excess of ubiquitylated “Skp1-free” Met30, which is rapidly degraded by a noncanonical pathway via a Cdc53-dependent, but Skp1-independent, proteolytic pathway (62). This pathway is necessary to prevent substrate shielding by Met30 that is separated from SCF (62). Consistent with this model, Met30 that cannot associate with Skp1 due to deletion of the F-box motif (Met30∆F-box) is stabilized in temperature-sensitive ufd1-2 and npl4-2 mutants (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). Therefore, we speculate that there might be two populations of Cdc48 complexes involved in processing of SCFMet30 during cadmium stress. The Cdc48Shp1 complex is required for the disassembly of the SCFMet30 complex and Cdc48Ufd1/Npl4 for degradation of unbound Met30 via the proteasomal pathway.

Surprisingly, Met30 protein levels were significantly decreased in shp1∆ mutants compared to wild-type cells (Figs. 1A and 2B). While Shp1 is involved in the degradation of a Cdc48-dependent model substrate (43), the half-life of Met30 is unaffected in shp1∆ cells and all other shp1 mutant variants we tested (SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). However, MET30 RNA levels were significantly decreased in the shp1∆ knockout strain (SI Appendix, Fig. S2G). Accordingly, low Met30 protein levels are due to a transcriptional defect. Since all other Shp1 mutants showed normal RNA levels, we hypothesize that altered transcription might be associated with other aspects of Shp1 function (52).

Closer examination of functional domains in Shp1 revealed several interesting findings. We expected that the UBA domain with its ubiquitin binding ability plays a role in Shp1 recruitment to Met30, which is autoubiquitylated during heavy metal stress (16). Additionally, it has been proposed that UBA domains can inhibit ubiquitin chain elongation (63). However, deletion of the UBA domain in Shp1 did not show any cadmium-specific phenotypes and is not required for SCFMet30 or Met4 regulation (Fig. 3).

It was also unexpected that Cdc48 and Shp1 were independently recruited to SCFMet30 upon cadmium exposure (Figs. 1A and 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4E) because Shp1 is believed to be constitutively bound to Cdc48 to fulfill its cellular tasks (44, 49, 50). While independent recruitment of Cdc48 is supported by results in cells lacking Shp1 (Fig. 1A), autonomous recruitment of Shp1 was suggested based on experiments using mutant versions of Shp1 with dramatically reduced Cdc48 steady-state binding activity. We can therefore not completely exclude that, under normal conditions, Shp1 is corecruited as a Cdc48-associated cofactor. However, we can conclude that independent binding sites for Cdc48 and Shp1 exist on SCFMet30 that drive recruitment. Furthermore, the interaction of Shp1∆CIM2 with Cdc48 is dramatically compromised (Fig. 2D), yet Shp1∆CIM2 is efficiently recruited to SCFMet30, and shp1-∆cim2 mutants disassemble and effectively inactivate SCFMet30, indistinguishable from wild-type cells (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4E). These findings further support two independent binding sites for Cdc48 and Shp1 on SCFMet30, and the proposed model that mechanical transmission of forces to separate Met30 from the core SCF requires at least two anchor points.

Truncation of the last 22 residues of Shp1 (∆UBXCt), like mutation of the CIM2 domain, results in severely reduced steady-state binding to Cdc48 (Fig. 2D). However, in contrast to shp1-∆cim2 mutants, shp1-∆UBXCt mutants fail to efficiently disassemble SCFMet30 and activate Met4 (Fig. 3). The reduced interaction with Cdc48 cannot be the reason for failure to dissociate Met30 because Shp1∆CIM2 is equally deficient in Cdc48 interaction, yet recruitment to SCFMet30 and Met30 dissociation is undistinguishable from wild-type cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E). Our results more likely suggest that the C terminus of the UBX domain is important for proper topological assembly of a functional disassembly complex to stimulate the Cdc48 ATPase activity and generate the required force for Met30 dissociation. In addition, the residues we deleted are potential posttranslational modification sites in the human ortholog p47 (64, 65). Lack of these modifications might hinder correct interactions of the disassembly complex.

This necessity for the 22 C-terminal residues of Shp1 to trigger disassembly but dispensability for recruitment presents as a separation of function mutant that allows formation but not activation of the disassembly complex. Consequently, we observed accumulation of Cdc48 on SCFMet30 in shp1-∆UBXCt mutants, which likely presents a dissociation intermediate, trapped just before the step of SCFMet30 disassembly. Surprisingly, even during normal, unstressed growth conditions, the usually very low amount of Cdc48 in complex with Met30 is significantly increased in shp1-∆UBXCt mutants (Fig. 4A), suggesting continuous low-level dissociation of Met30 from the core SCF. This process may be part of a quality control mechanism that monitors proper assembly of the ubiquitin–ligase complex.

While Cdc48/p97 can bind to ubiquitin directly in vitro (29), UBX cofactors are thought to be adaptors that regulate the interaction between Cdc48 and ubiquitylated substrates (44). Under normal growth conditions, Met30 is ubiquitylated at low levels, but cadmium stress drastically increases Met30 autoubiquitylation (16). This autoubiquitylation is the recruitment signal for Cdc48, and, given that Cdc48 recruitment is independent of Shp1 and Npl4/Ufd1 (Figs. 1A and 3A) (16), a direct interaction with ubiquitylated Met30 is likely. However, we conclude that Shp1 is likely required to properly orient the complex, activate the ATPase activity, and provide a second attachment point for transmission of the mechanical force.

Initially, we used the AID system for induced down-regulation of Shp1 to study acute loss of Shp1 function and eliminate possible indirect effects caused by secondary mutations acquired by the shp1∆ deletion strain. However, it also became a handy tool to closer examine dependence of SCFMet30 disassembly on different levels of Shp1. This question was interesting because different concentration-dependent binding modes of p47 to p97 have been suggested to control p97 ATPase activity (54). Decreased Shp1-AID levels resulted in impaired SCFMet30 dissociation (Fig. 1D), and titration of Shp1-AID levels uncovered a correlation between Shp1 abundance and disassembly (Fig. 4 C and D). This phenomenon is likely related to a need for a minimum concentration of Shp1 in the dissociation complex to activate Cdc48. When first discovered, human p47 was described as an inhibitor of p97 activity (60). However, a later study showed a more complex mechanism of ATPase regulation by p47, in which higher concentrations of p47 bound to p97 relieve inhibition of p97 ATPase activity (54). The authors suggest that a transition from monomeric to trimeric p47 on p97 is responsible for this effect (54). We hypothesized that, when Shp1 is present at low amounts, Cdc48 activity is maximally inhibited. During heavy metal stress, the recruitment of the cofactor leads to a local increase of Shp1 in SCFMet30. This might trigger trimerization of Shp1, potentially leading to Ccd48 ATPase stimulation necessary for Met30 dissociation. Accordingly, we show that deletion of the SEP domain, which is important for Shp1 trimerization, leads to a Met30 dissociation defect during cadmium stress.

In summary, our study identifies the UBA-UBX family member Shp1 as the key cofactor for signal-induced disassembly of SCFMet30. We show that the ATPase Cdc48 and Shp1 are recruited independently to SCFMet30 during cadmium stress, but interaction through the C-terminal end of the Shp1 UBX domain is necessary to activate the dissociation complex and catalyze separation of Met30. Additionally, the local increase of Shp1 in SCFMet30 might lead to ATPase stimulation required for efficient complex dissociation. These results provide insight into ubiquitin-dependent, signal-induced, active remodeling of multiprotein complexes to control their activity.

Methods

Plasmids, Yeast Strains, and Growth Conditions.

Yeast strains used in this study are isogenic to 15DaubD, a bar1D ura3Dns, a derivative of BF264-15D (66). Specific strains are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1. The 9×MYC tag of pADH_OsTir9×MYC::URA (57) was exchanged with a 2×FLAG tag by amplification of the vector using primers 1 and 2 (SI Appendix, Table S3). The PCR fragment was digested with BamHI and ligated to generate pADH_OsTir2×FLAG::URA. The plasmid was linearized with StuI and transformed into yeast strain PY1. Next, The AID fragment was amplified from the pKAN-pCUP1-9×MYC-AID plasmid using primers 3 and 4 (SI Appendix, Table S3) and inserted via Gibson assembly into the AscI linearized pFA6a-3×HA::TRP plasmid to generate the tagging vector pFA6a-3×HA-AID::TRP. A PCR fragment using primers 13 and 14 (SI Appendix, Table S3) was amplified and transformed into PY1+pADH_OsTir2×FLAG::URA. This strain was transformed with YCpLEUpmet30_9×MYCMET30 to generate PY2230. For CRISPR/Cas9-edited yeast strains, the vector pML107 (67), which contains both sgRNA and Cas9 expression cassettes, was used. To generate the guide RNA sequences, the “CRISPR Toolset” (http://wyrickbioinfo2.smb.wsu.edu/crispr.html) was consulted. pML107 was linearized using SwaI, and hybridized primers for gRNAs as shown in SI Appendix, Table S3, were inserted via Gibson assembly to generate pML107-Shp1 vectors (SI Appendix, Table S2). The vectors were transformed together with the hybridized 90mer oligos containing the Shp1-specific repair sequence into PY1630 to generate marker-free Shp1::3×HA mutants shown in SI Appendix, Table S1. All other strains used were generated using classic PCR-based gene modification methods (68). Generated plasmids and strains were verified by sequencing. All strains were cultured in standard media, and standard yeast genetic techniques were used unless stated otherwise (69). References to the use of cadmium (Cd2+) are specifically to cadmium chloride (CdCl2). For cell spotting assays, strains were cultured to logarithmic growth phase, sonicated, and then counted. Serial dilutions were made and spotted onto YEPD plates supplemented with or without indicated amounts of CdCl2 via a pin replicator (V&P Scientific).

Protein Analysis.

For Western blot analyses and immunoprecipitation assays, yeast whole-cell lysates were prepared under native conditions in Triton X-100 buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 0.2% Triton X-100, 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM Na-pyrophosphate, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 50 mM NaF, 0.1 mM orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], and 1 mg/mL each leupeptin and pepstatin). Cells were homogenized in a screw-cap tube with 0.5-mm glass beads and Antifoam Y-30 using an MP FastPrep 24 (speed 4.0, 3 × 20 s). Lysates were separated from glass beads and transferred into 1.5-mL reaction tubes (USA Scientific). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (10 min, 14,000 × g at 4 °C). For Western blot analyses, proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Proteins were detected with the following primary antibodies: anti-Met4 (1:20,000; a gift from M. Tyers), anti-Skp1 (1:5,000; a gift from R. Deshaies, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), anti-Cdc48 (1:20,000; a gift from E. Jarosch, Max-Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany), anti-Myc (1:2,000; Santa Cruz, 9E10), anti-HA (1:2,000; Santa Cruz, F7), anti-RGS6H (1:2,000; Qiagen), and anti-tubulin (1:2,000; Santa Cruz). Western blot results shown are representative blots from three experiments with independent cultures. Band intensities of immunoblots were quantified using either ImageJ or the Bio-Rad Image Lab software. For immunoprecipitation of 9×MYC-tagged proteins, 1 mg of total protein lysate was incubated in Triton X-100 buffer-equilibrated MYC-trap beads (Chromotek) in a final volume of 500 µL overnight at 4 °C on a nutator. The next day, beads and supernatants were separated by centrifugation (2 min, 100 × g at 4 °C). Beads were washed three times in 1 mL Triton X-100 buffer plus inhibitors at 4 °C. Beads were resuspended in 2× Laemmli buffer and boiled for 5 min to elute proteins. For immunoprecipitation of 3×HA-tagged proteins, 1 mg of total protein lysate in a final volume of 500 µL was incubated with 1 µg of anti-HA Y-11 (Santa Cruz; discontinued) for 2 h at 4 °C on a nutator. Triton X-100 buffer-equilibrated protein A Sepharose (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and incubated overnight at 4 °C on a nutator. The next day, beads and supernatants were separated by centrifugation (2 min, 100 × g at 4 °C). Beads were washed three times in 1 mL Triton X-100 buffer plus inhibitors at 4 °C. Beads were resuspended in 2× Laemmli buffer and boiled for 5 min to elute proteins.

RNA and RT-qPCR.

Yeast RNA was prepared using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA synthesis was performed using Super Script II Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen). A total of 1.5 µg of RNA was transcribed into cDNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The synthesized cDNA was diluted 1:15 in nuclease-free water. qPCR was performed with a Bio-Rad CFX Connect RT-PCR machine using the Bio-Rad iTaq Universal SYBR Green SuperMix, and 4 µL of the cDNA 1:15 dilution was used in a 20-µL reaction as a template. Primers were used at a final concentration of 0.2 µM. Sequences of primers are as follows: MET25F, GCCACCACTTCTTATGTTTTCG; MET25R, AGCAGCAGCACCACCTTC; GSH1F, TGACAGCATCCATCAGGACCAG; GSH1R, GGAAGCCAGTTTCGCCTCTTTG; 18SrRNAF, GTGGTGCTAGCATTTGCTGGTTAT; and 18SrRNAR, CGCTTACTAGGAATTCCTCGTTGAA. 18S rRNA was used as a normalization control for each sample. The ∆∆Ct method was used for analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Jentsch, T. Rapoport, P. Silver, and R. Hampton for yeast strains and R. Deshaies, W. Harper, M. Tyers, T. Sommer, and E. Jarosch for antibodies. This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grant R01 GM-066164 to P.K. and the Hitachi-Nomura Award to L. L.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1922891117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All data discussed are included within the paper and the provided SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Nakatogawa H., Suzuki K., Kamada Y., Ohsumi Y., Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: Lessons from yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 458–467 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershko A., Ciechanover A., The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varshavsky A., Regulated protein degradation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 283–286 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finley D., Ulrich H. D., Sommer T., Kaiser P., The ubiquitin-proteasome system of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 192, 319–360 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komander D., Rape M., The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 203–229 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerscher O., Felberbaum R., Hochstrasser M., Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 159–180 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pickart C. M., Eddins M. J., Ubiquitin: Structures, functions, mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1695, 55–72 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varshavsky A., The ubiquitin system, an immense realm. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 167–176 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshaies R. J., Joazeiro C. A. P., RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 399–434 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duda D. M. et al., Structural regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase complexes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21, 257–264 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petroski M. D., Deshaies R. J., Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 9–20 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin J. et al., Systematic analysis and nomenclature of mammalian F-box proteins. Genes Dev. 18, 2573–2580 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciechanover A., Schwartz A. L., Ubiquitin-mediated degradation of cellular proteins in health and disease. Hepatology 35, 3–6 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt M., Finley D., Regulation of proteasome activity in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 13–25 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skowyra D., Craig K. L., Tyers M., Elledge S. J., Harper J. W., F-box proteins are receptors that recruit phosphorylated substrates to the SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex. Cell 91, 209–219 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yen J. L. L. et al., Signal-induced disassembly of the SCF ubiquitin ligase complex by Cdc48/p97. Mol. Cell 48, 288–297 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li F. N., Johnston M., Grr1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is connected to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through Skp1: Coupling glucose sensing to gene expression and the cell cycle. EMBO J. 16, 5629–5638 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaiser P., Su N.-Y., Yen J. L., Ouni I., Flick K., The yeast ubiquitin ligase SCFMet30: Connecting environmental and intracellular conditions to cell division. Cell Div. 1, 16 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouni I., Flick K., Kaiser P., A transcriptional activator is part of an SCF ubiquitin ligase to control degradation of its cofactors. Mol. Cell 40, 954–964 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rouillon A., Barbey R., Patton E. E., Tyers M., Thomas D., Feedback-regulated degradation of the transcriptional activator Met4 is triggered by the SCF(Met30 )complex. EMBO J. 19, 282–294 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yen J. L., Su N. Y., Kaiser P., The yeast ubiquitin ligase SCFMet30 regulates heavy metal response. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 1872–1882 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbey R. et al., Inducible dissociation of SCF(Met30) ubiquitin ligase mediates a rapid transcriptional response to cadmium. EMBO J. 24, 521–532 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patton E. E. et al., SCF Met30 -mediated control of the transcriptional activator Met4 is required for the G 1–S transition. EMBO J. 19, 1613–1624 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wheeler G. L., Trotter E. W., Dawes I. W., Grant C. M., Coupling of the transcriptional regulation of glutathione biosynthesis to the availability of glutathione and methionine via the Met4 and Yap1 transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 49920–49928 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carrillo E. et al., Characterizing the roles of Met31 and Met32 in coordinating Met4-activated transcription in the absence of Met30. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 1928–1942 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flick K., Raasi S., Zhang H., Yen J. L., Kaiser P., A ubiquitin-interacting motif protects polyubiquitinated Met4 from degradation by the 26S proteasome. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 509–515 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hampton R. Y., ER-associated degradation in protein quality control and cellular regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 476–482 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodnar N. O., Rapoport T. A., Molecular mechanism of substrate processing by the Cdc48 ATPase complex. Cell 169, 722–735.e9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rape M. et al., Mobilization of processed, membrane-tethered SPT23 transcription factor by CDC48(UFD1/NPL4), a ubiquitin-selective chaperone. Cell 107, 667–677 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shcherbik N., Haines D. S., Cdc48p(Npl4p/Ufd1p) binds and segregates membrane-anchored/tethered complexes via a polyubiquitin signal present on the anchors. Mol. Cell 25, 385–397 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acs K. et al., The AAA-ATPase VCP/p97 promotes 53BP1 recruitment by removing L3MBTL1 from DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 1345–1350 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franz A. et al., CDC-48/p97 coordinates CDT-1 degradation with GINS chromatin dissociation to ensure faithful DNA replication. Mol. Cell 44, 85–96 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raman M., Havens C. G., Walter J. C., Harper J. W., A genome-wide screen identifies p97 as an essential regulator of DNA damage-dependent CDT1 destruction. Mol. Cell 44, 72–84 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verma R., Oania R., Fang R., Smith G. T., Deshaies R. J., Cdc48/p97 mediates UV-dependent turnover of RNA Pol II. Mol. Cell 41, 82–92 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilcox A. J., Laney J. D., A ubiquitin-selective AAA-ATPase mediates transcriptional switching by remodelling a repressor-promoter DNA complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1481–1486 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ndoja A., Cohen R. E., Yao T., Ubiquitin signals proteolysis-independent stripping of transcription factors. Mol. Cell 53, 893–903 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer H., Bug M., Bremer S., Emerging functions of the VCP/p97 AAA-ATPase in the ubiquitin system. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 117–123 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rumpf S., Jentsch S., Functional division of substrate processing cofactors of the ubiquitin-selective Cdc48 chaperone. Mol. Cell 21, 261–269 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buchberger A., Schindelin H., Hänzelmann P., Control of p97 function by cofactor binding. FEBS Lett. 589, 2578–2589 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buchberger A., From UBA to UBX: New words in the ubiquitin vocabulary. Trends Cell Biol. 12, 216–221 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bertolaet B. L. et al., UBA domains of DNA damage-inducible proteins interact with ubiquitin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 417–422 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkinson C. R. M. et al., Proteins containing the UBA domain are able to bind to multi-ubiquitin chains. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 939–943 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schuberth C., Richly H., Rumpf S., Buchberger A., Shp1 and Ubx2 are adaptors of Cdc48 involved in ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. EMBO Rep. 5, 818–824 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuberth C., Buchberger A., UBX domain proteins: Major regulators of the AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2360–2371 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kloppsteck P., Ewens C. A., Förster A., Zhang X., Freemont P. S., Regulation of p97 in the ubiquitin-proteasome system by the UBX protein-family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 125–129 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alexandru G. et al., UBXD7 binds multiple ubiquitin ligases and implicates p97 in HIF1α turnover. Cell 134, 804–816 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beuron F. et al., Conformational changes in the AAA ATPase p97-p47 adaptor complex. EMBO J. 25, 1967–1976 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dreveny I. et al., Structural basis of the interaction between the AAA ATPase p97/VCP and its adaptor protein p47. EMBO J. 23, 1030–1039 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bruderer R. M., Brasseur C., Meyer H. H., The AAA ATPase p97/VCP interacts with its alternative co-factors, Ufd1-Npl4 and p47, through a common bipartite binding mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49609–49616 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krick R. et al., Cdc48/p97 and Shp1/p47 regulate autophagosome biogenesis in concert with ubiquitin-like Atg8. J. Cell Biol. 190, 965–973 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang S., Guha S., Volkert F. C., The Saccharomyces SHP1 gene, which encodes a regulator of phosphoprotein phosphatase 1 with differential effects on glycogen metabolism, meiotic differentiation, and mitotic cell cycle progression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 2037–2050 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Böhm S., Buchberger A., The budding yeast Cdc48Shp1 complex promotes cell cycle progression by positive regulation of protein phosphatase 1 (Glc7). PLoS One 8, 22–24 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng Y. L., Chen R. H., The AAA-ATPase Cdc48 and cofactor Shp1 promote chromosome bi-orientation by balancing Aurora B activity. J. Cell Sci. 123, 2025–2034 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang X. et al., Altered cofactor regulation with disease-associated p97/VCP mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E1705–E1714 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giaever G., Nislow C., The yeast deletion collection: A decade of functional genomics. Genetics 197, 451–465 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nishimura K., Fukagawa T., Takisawa H., Kakimoto T., Kanemaki M., An auxin-based degron system for the rapid depletion of proteins in nonplant cells. Nat. Methods 6, 917–922 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morawska M., Ulrich H. D., An expanded tool kit for the auxin-inducible degr on system in budding yeast. Yeast 30, 341–351 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hitt R., Wolf D. H., Der1p, a protein required for degradation of malfolded soluble proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum: Topology and Der1-like proteins. FEMS Yeast Res. 4, 721–729 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sato B. K., Hampton R. Y., Yeast Derlin Dfm1 interacts with Cdc48 and functions in ER homeostasis. Yeast 23, 1053–1064 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meyer H. H., Kondo H., Warren G., The p47 co-factor regulates the ATPase activity of the membrane fusion protein, p97. FEBS Lett. 437, 255–257 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuan X. et al., Structure, dynamics and interactions of p47, a major adaptor of the AAA ATPase, p97. EMBO J. 23, 1463–1473 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mathur R., Yen J. L., Kaiser P., Skp1 independent function of Cdc53/Cul1 in F-box protein homeostasis. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005727 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen L., Shinde U., Ortolan T. G., Madura K., Ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains in Rad23 bind ubiquitin and promote inhibition of multi-ubiquitin chain assembly. EMBO Rep. 2, 933–938 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim W. et al., Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Mol. Cell 44, 325–340 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Akimov V. et al., UbiSite approach for comprehensive mapping of lysine and N-terminal ubiquitination sites. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 631–640 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reed S. I., Hadwiger J. A., Lörincz A. T., Protein kinase activity associated with the product of the yeast cell division cycle gene CDC28. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 4055–4059 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laughery M. F. et al., New vectors for simple and streamlined CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 32, 711–720 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Longtine M. S. et al., Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14, 953–961 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guthrie C., Fink G. R., Methods in Enzymology: Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology, (Academic Press, 1991), Vol. vol. 194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data discussed are included within the paper and the provided SI Appendix.