Abstract

The skeletal muscle mass is known to be controlled by the balance between protein synthesis and degradation. The fractional rate of protein synthesis has been reported to decrease age-dependently from 1 to 4 weeks of age in the chicken breast muscle (pectoralis major muscle). On the other hand, age-dependent change of the fractional protein degradation rate was reported to be less in the skeletal muscle of chickens. These findings suggest that protein synthesis is age-dependently downregulated in chicken muscle. We herein investigated the age-dependent changes in protein synthesis or proteolysis-related factors in the breast muscle of 7, 14, 28, and 49-day old broiler chickens. IGF-1 mRNA level, phosphorylation rate of Akt, and phospho-S6 content were coordinately decreased in an age-dependent manner, suggesting that IGF-1-stimulated protein synthesis is downregulated with age in chicken breast muscle. In contrast, atrogin-1, one of the proteolysis-related factors, gradually increased with age at mRNA levels. However, plasma Nτ-methylhistidine concentration, an indicator of skeletal muscle proteolysis, did not coordinately change with atrogin-1 mRNA levels. Taken together, our results suggest that the IGF-1/Akt/S6 signaling pathway is age-dependently downregulated in the chicken breast muscle.

Keywords: broiler chicken, protein metabolism, skeletal muscle

Introduction

The skeletal muscle mass is controlled by the balance between protein synthesis and degradation. When the rate of protein synthesis exceeds that of protein degradation, skeletal muscle mass increases. Insulin and insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) are important positive regulators in protein synthesis (Glass, 2005; Tesseraud et al., 2007; Sandri, 2008; Schiaffino et al., 2013). They induce phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 (S6), which is a critical event in protein translation (Shah et al., 2000), through phosphorylation of Akt. In contrast, myostatin is known to inhibit the IGF-1/Akt signaling pathway (Gumucio and Mendias, 2013).

The degradation of skeletal muscle protein is regulated by a cascade of proteolytic events. Apoptotic caspase-3 and Ca2+-dependent calpains are involved especially in an initial step of myofibrillar proteolysis (Baltoli and Richard, 2005; Goll et al., 1992; Du et al., 2004), and the resulting partially-degraded myofibrillar protein is further broken down by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (Glass, 2005; Sandri, 2013; Schiaffino et al., 2013). This system contributes to approximately 90% of proteolysis in a cell (Neel et al., 2013), and is upregulated by myostatin through forkhead box class O (FOXO)-induced transcription of ubiquitin ligases, such as atrogin-1 and muscle ring-finger protein 1 (MuRF-1) (Glass, 2005; Gumucio and Mendias, 2013; Lokireddy et al., 2011; Sanchez et al., 2014; Sandri, 2008, 2013; Sandri et al., 2004; Schiaffino et al., 2013). As a result of myofibrillar protein degradation, Nτ -methylhistidine, which is neither broken down nor reused for protein synthesis after proteolysis (Young et al., 1972; Long et al., 1975), is released.

Broiler chickens have been genetically selected to improve the performance of meat production, and genetic selection has led to high growth rate, feed efficiency, and meat (especially breast muscle) yield (Arthur and Albers, 2003). Although the important selection traits change according to production and market trends, growth rate has consistently been the prime selection trait because of its large impact on total meat production cost (Arthur and Albers, 2003). However, growth rate was reported to decrease with age in chickens (Kang et al., 1985; Reiprich et al., 1995), suggesting that the regulation of protein turnover changes with age in chicken skeletal muscle. For example, fractional rates of protein synthesis have been shown to decrease in chicken breast muscle during the period of 1–4 weeks of age, but the fractional protein degradation rate changed little to none during the same period (Kang et al., 1985; Tesseraud et al., 1996). These findings suggest that the protein synthetic system is age-dependently downregulated, whereas the proteolytic system changes little with age. Thus, fully understanding the molecular mechanisms that underlie the age-dependent change in the regulation of protein synthesis and degradation in the chicken skeletal muscle will provide a new strategy for improving broiler performance.

In an effort to understand this change in protein synthesis and degradation, we investigated the mRNA and protein levels of protein metabolism-related factors in the breast muscle of 7 to 49 day-old broiler chickens. Our results showed that IGF-1 mRNA levels, phosphorylation rate of Akt, and phospho-S6 protein contents were coordinately decreased with age, suggesting that the IGF-1/Akt/S6 signaling pathway is age-dependently downregulated in the chicken breast muscle.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Sampling

Day-old male broiler (chunky) chicks were purchased from a local hatchery (Ishii Poultry Farming Cooperative Association, Tokushima, Japan). During the experimental period, they were given free access to water and a commercial chicken starter diet (23.5% crude protein and 3,050 kcal/kg, Nippon Formula Feed Mfg. Co. Ltd., Kanagawa, Japan). At 7, 14, 28, and 49 days of age, six chickens were randomly selected, and their body weights were measured. The chickens were then sacrificed by decapitation, and their blood was collected. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid was used as an anticoagulant. Plasma was separated immediately by centrifugation at 3,000×g for 10 min at 4°C, then frozen using liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for analysis. The left breast muscle (pectoralis major muscle) was dissected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80°C for real-time PCR and western blot analysis. The right breast muscles were also excised and weighed. This animal experiment was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and carried out according to the Kobe University Animal Experimental Regulation.

Plasma Insulin and Nτ-methylhistidine

Plasma insulin concentration was measured using a commercial kit (Rat Insulin ELISAKIT (TMB), Shibayagi, Gunma, Japan). To determine plasma Nτ-methylhistidine concentration, 200 µL plasma samples were mixed with 68 µL of 20% sulfosalicylic acid and centrifuged at 8,000×g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatants were freeze-dried and dissolved in 100 µL of 50 mmol/L SDS/acetonitrile/phosphoric acid (610:390:3). Nτ-methylhistidine levels were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography as previously described (Yamaoka et al., 2008)

Real-time PCR Analysis

The expression pattern of calpain isozymes is largely different between mammals and chickens (Baltoli and Richard, 2005; Lee et al., 2007; Sorimachi et al., 1995). For example, m-calpain, a major isozyme in mammalian skeletal muscle, is transcribed from the gene but not translated to protein in chickens (Lee et al., 2007). Mu/m-calpain, which has no counterpart in mammals, is a major isozyme in all chicken tissues (Lee et al., 2007). We therefore investigated the mRNA levels of µ/m-calpain.

Total RNA was extracted from the muscles using Sepazol-RNA I (Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 5 µg of DNase I (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX, USA)-treated total RNA using ReverTra Ace® qPCR RT Kit (Toyobo Co. Ltd, Osaka, Japan). mRNA levels were quantified using each primer (Table 1), Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and THUNDERBIRD™ SYBR qPCR® Mix (Toyobo Co. Ltd, Osaka, Japan) according to the supplier's recommendations. The expression levels of target genes were normalized to those of ribosomal protein S17 (RPS17).

Table 1. Primer sequences used for real-time PCR analysis.

| Gene name | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Product size (bp) | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrogin-1 | 5′-cac ctt ggg aga agc ctt caa-3′ | 5′-ccg gga gtc cag gat agc a-3′ | 58 | NM_001030956 |

| Caspase 3 | 5′-gga aca cgc cag gaa act tg-3′ | 5′-tct gcc act ctg cga ttt aca-3′ | 64 | AF083029 |

| FOXO1 | 5′-tct ggt cag gag gga aat gg-3′ | 5′-gct tgc agg cca ctt tga g-3′ | 60 | NM 204328 |

| FOXO3 | 5′-ggg aag agc tcc tgg at-3′ | 5′-ggg cgc ctt gcc aac t-3′ | 57 | XM 001234495 |

| IGF-1 | 5′-gct gcc ggc cca gaa-3′ | 5′-acg aac tga aga gca tca acc a-3′ | 56 | NM 001004384 |

| MuRF-1 | 5′-tgg aga ttg agc aag gct at-3′ | 5′-gcg agg tgc tca aga ctg act-3′ | 64 | XM 424369 |

| Myostatin | 5′-atg cag atc gcg gtt gat c-3′ | 5′-gcg ttc tct gtg ggc tga ct-3′ | 59 | NM 001001461 |

| μ/m-Calpain | 5′-cac aca agg agg ccg act tc-3′ | 5′-tcc gct gtg tct gac tgc tt-3′ | 61 | NM 205303 |

| RPS17 | 5′-gcg ggt gat cat cga gaa gt-3′ | 5′-gcg ctt gtt ggt gtg aag t-3′ | 61 | NM_204217 |

FOXO, forkhead box class O; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; MuRF-1, muscle ring-finger protein 1; RPS17, ribosomal protein S17.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (Ibuki et al., 2014; Saneyasu et al., 2015). Anti-p-S6 (S235/236) (#2211), anti-Akt (#9272), anti-p-Akt (S473) (#9271), and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (#7074) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). As a loading control, anti-vinculin (V4139) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC (St. Louis, MO, USA). After the detection of bands, membranes were rinsed with Restore™ Plus Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL, USA), and used for reprobing with proper antibodies.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Tukey-Kramer method. All statistical analyses were performed using the commercial package (StatView version 5, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA, 1998).

Results

The results of body weight, breast muscle weight, and plasma concentrations of insulin and Nτ-methylhistidine are shown in Table 2. Body and breast muscle weight significantly increased with age. The concentrations of plasma Nτ-methylhistidine were significantly higher at 49 days of age than at 28 days of age. In contrast, no significant change was observed in plasma insulin concentration during the experimental period.

Table 2. Changes in body weight, breast muscle weight, and plasma concentrations of insulin and Nτ-methylhistidine in chickens.

| Days of age |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 14 | 28 | 49 | |

| Body weight (g) | 150.8±6.8a | 521.7±21.6b | 1862.5±34.3c | 4124.0±77.4d |

| Right breast muscle (g) | 6.2±0.4a | 36.9±1.9b | 185.9±3.2c | 503.5±20.1d |

| Plasma insulin (ng/ml) | 1.90±0.37 | 1.47±0.38 | 1.34±0.21 | 0.87±0.19 |

| Plasma Nτ-methylhistidine (nmol/ml) | 22.55±2.27ab | 19.08±1.96ab | 15.74±1.55a | 28.36±4.26b |

Values are means±SEM of six chickens in each group. Data were analyzed by the Tukey-Kramer method. Groups with different letters were significantly different (P<0.05).

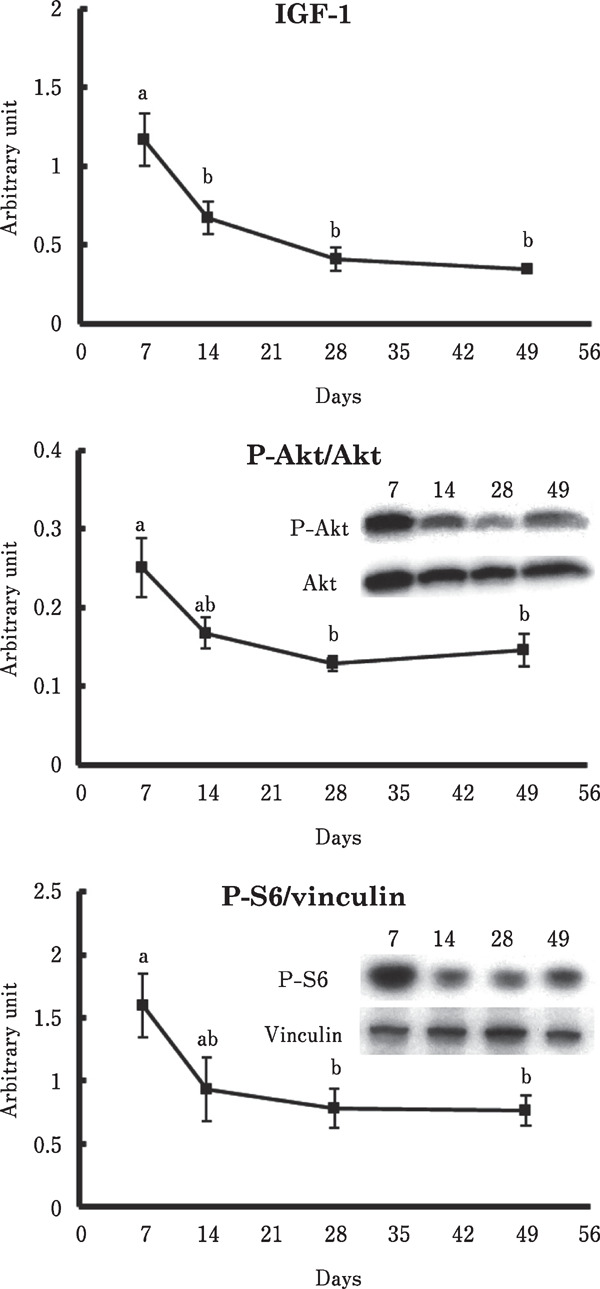

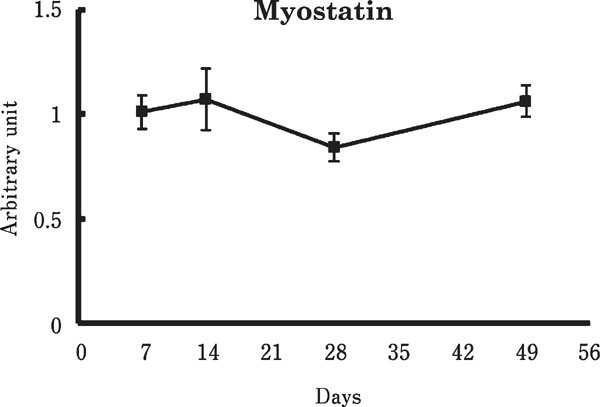

Figure 1 shows the changes of mRNA and protein levels involved in protein synthesis in the chicken breast muscle. The IGF-1 mRNA level was markedly decreased from 7 to 14 days old. Also, phosphorylation of Akt and protein contents of phosphorylated S6 (p-S6) were age-dependently decreased. In contrast, no significant change was observed in the myostatin mRNA level (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Changes in the IGF-1 mRNA level, phosphorylation of Akt, and protein content of phosphorylated S6 in the chicken breast muscle. Values are means±SEM of six chickens in each group. Data were analyzed by the Tukey-Kramer method was performed. Groups with different letters were significantly different (P<0.05).

Fig. 2.

Change in the myostatin mRNA level in the chicken breast muscle. Values are means±SEM of six chickens in each group. Data were analyzed by the Tukey-Kramer method was performed.

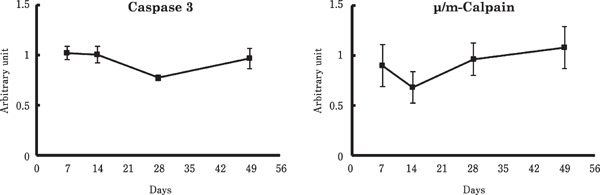

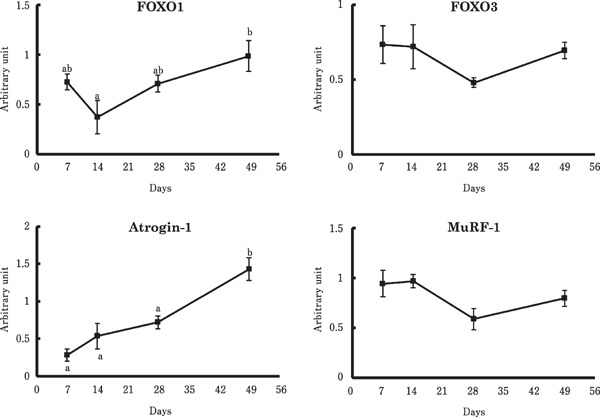

Figures 3 and 4 show the effects of age on expression of genes involved in skeletal muscle proteolysis. The mRNA level of FOXO1 was significantly higher at 49 days old than at 14 days old. Atrogin-1 expression was also increased at 49 days of age, compared to 28 days of age. In contrast, no significant changes were observed in the mRNA levels of caspase-3, µ/m-calpain, FOXO3, or MuRF-1.

Fig. 3.

Changes in the mRNA levels of caspase-3 and µ/m-calpain in the chicken breast muscle. Values are means±SEM of six chickens in each group. Data were analyzed by the Tukey-Kramer method was performed.

Fig. 4.

Changes in the mRNA levels of FOXO1, FOXO3, atrogin-1, and MuRF-1 in the chicken breast muscle. Values are means±SEM of six chickens in each group. Data were analyzed by the Tukey-Kramer method was performed. Groups with different letters were significantly different (P<0.05).

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that the fractional rate of protein synthesis decreases with age in skeletal muscle in both mammals (Davis et al., 1989, 2009) and chickens (Kang et al., 1985; Maeda et al., 1984; Tesseraud et al., 1996). For example, Kang et al. (1985) reported that the fractional synthesis rate in the breast muscle decreased by more than 50% between 1- and 2-week old chickens, and then continued to slowly decrease. In addition, IGF-1 proteins and phosphorylation of Akt were previously reported to be higher in the pectoralis major muscle in 7-day old broiler chickens than in 43-day old broiler chickens (Vaudin et al., 2006). These finding suggest that muscle protein synthesis is downregulated with age, especially from 1 to 2 weeks of age. However, there have been no report on the age-dependent change in the IGF-1 induced protein synthetic pathway. In the present study, we found that the mRNA levels of IGF-1 markedly decreased from 7 to 14 days of age in the breast muscle of chickens (Fig. 1). In addition, Akt phosphorylation and the p-S6 content decreased with corresponding decreased IGF-1 mRNA levels (Fig. 1). Thus, our results provide the first evidence that the skeletal muscle IGF-1/Akt/S6 signaling pathway is age-dependently downregulated in the breast muscle of commercial broiler chickens.

In addition to its production in the skeletal muscle, IGF-1 is known to be produced in the liver and secreted to the bloodstream in chickens. Therefore, it is possible that plasma IGF-1 influences phosphorylation of Akt and S6 in this study. However, there is evidence that plasma IGF-1 concentration increases with growth in chickens (Goddard et al., 1988; McGuinness et al., 1990; Radecki et al., 1997), in contrast to the age-dependent decreasing phosphorylation of Akt and S6 in our study (Fig. 1). All these findings suggest that plasma IGF-1 cannot cause age-dependent downregulation of the Akt/S6 signaling pathway.

The Akt/S6 signaling pathway was also activated by insulin in chicken skeletal muscle (Tesseraud et al., 2007). However, we observed no significant change in the plasma insulin concentration (Table 2), in contrast to the values of p-Akt/Akt and p-S6/vinculin in the breast muscle (Fig. 1). Therefore, insulin might not be the cause of the age-dependent downregulation of protein synthesis in the chicken breast muscle.

Myostatin negatively regulates protein synthesis through the inhibition of Akt phosphorylation and positively regulates proteolysis through the promotion of atrogin-1 transcription in mammalian skeletal muscle (Glass, 2005; Gumucio and Mendias, 2013; Lokireddy et al., 2011; Sandri, 2008; Schiaffino et al., 2013). However, in our study, myostatin expression did not significantly change during the experimental period (Fig. 2), even though the phosphorylation of Akt and the mRNA levels of atrogin-1 significantly changed with age (Fig. 1 and 4). Therefore, it seems likely that myostatin is not involved in the age-dependent downregulation of protein synthesis in chickens. We previously showed that myostatin expression was significantly suppressed by fasting in chickens, whereas atrogin-1 expression was significantly induced (Saneyasu et al., 2015). Similar results were reported concerning myostatin (Guernec et al., 2004) and atrogin-1 (Ohtsuka et al., 2011) in broiler chickens. It is therefore possible that myostatin is not involved in the upregulation of atrogin-1 expression in the chicken skeletal muscle.

Atrogin-1 is one of the key regulators related to skeletal muscle proteolysis (Glass, 2005; Schiaffino et al., 2013). A recent study revealed that atrogin-1 interacts with myosin heavy chain (MyHC) and myosin light chain (MyLC) (Lokireddy et al., 2011). In our study, the mRNA levels of atrogin-1 were gradually increased with age (Fig. 4). Similar to this result, Suryawan and Davis (2014) found that atrogin-1 protein contents in porcine skeletal muscle were significantly higher at 26 days of age than at 5 days of age. However, we found that plasma Nτ-methylhistidine concentration was not increased age-dependently (Table 2). In addition, the mRNA levels of other proteolysis-related factors such as protease (caspase 3 and µ/m-calpain), ubiquitin ligase MuRF-1, and transcription factor FOXO3 did not show significant changes throughout the experimental period (Fig. 3 and 4). These results are in agreement with the previous studies (Kang et al., 1985; Tesseraud et al., 1996): the fractional rate of protein degradation changed little during the period of 1 to 6 weeks of age in the chicken breast muscle. Although the FOXO1 mRNA level was significantly lower at 14 days of age than 49 days of age, this did not show an age-dependent manner. Thus, it is possible that the age-dependent increase of atrogin-1 expression was not sufficient to upregulate proteolysis in the chicken breast muscle.

Transcription of atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 are both promoted by FOXOs (Sanchez et al., 2014; Sandri, 2008; Sandri et al., 2004; Schiaffino et al., 2013). However, we found that the mRNA levels of atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 showed different changes (Fig. 4). Similar results were reported in the mammalian study: the abundance of atrogin-1 but not MuRF-1 was significantly changed with age in porcine skeletal muscle (Suryawan and Davis, 2014). Although the reason why mRNA levels of atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 changed differently remains unclear, several studies reported that the transcriptional control of atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 was different in some cases (Foletta et al., 2011; Frost et al., 2007; Yoshida et al., 2010; Mourkioti et al., 2006; Cai et al., 2004; Carson and Baltgalvis, 2010). For example, interleukin-6 (Yoshida et al., 2010) and angiotensin II (Carson and Baltgalvis, 2010) increase the mRNA level of atorgin-1 but not MuRF-1. Further studies are needed to clarify the difference in the transcription regulation between atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 in chickens.

In summary, we investigated the gene expression and protein levels of protein metabolism-related factors in the breast muscle of chickens. The coordinately age-dependent decreases were observed in the mRNA and protein levels of the IGF-1/Akt/S6 signaling pathway. These results suggest that the IGF-1/Akt/S6 signaling pathway is age-dependently downregulated in chicken breast muscle.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 15K18770.

References

- Arthur J, Albers G. Industrial perspective on problems and issues associated with poultry breeding. In: Muir WM, Aggrey SE. (eds), Poultry Genetics, breeding and biotechnology, pp. 1-12. CABI Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baltorli M, Richard I. Calpains in muscle wasting. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 37: 2115-2133. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AA, LeRoith D. Minireview: Tissue-specific versus generalized gene targeting of the igf1 and igf1r genes and their roles in insulin-like growth factor physiology. Endocrinology, 142: 1685-1688. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D, Frantz JD, Tawa NE, Jr, Melendez PA, Oh BC, Lidov HG, Hasselgren PO, Frontera WR, Lee J, Glass DJ, Shoelson SE. IKKbeta/NF-kappaB activation causes severe muscle wasting in mice. Cell, 119: 285-298. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JA, Baltgalvis KA. Interleukin-6 as a key regulator of muscle mass during chachexia. Exercise and sport sciences reviews, 38: 168-176. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TA, Fiorotto ML. Regulation of muscle growth in neonates. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 12: 78-85. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TA, Fiorotto ML, Nguyen HV, Reeds PJ. Protein turnover in skeletal muscle of suckling rats. American Journal of Physiology, 257: R1141-R1146. 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Wang X, Miereles C, Bailey JL, Debigare R, Zheng B, Price SR, Mitch WE. Activation of caspase-3 is an initial step triggering accelerated muscle proteolysis in catabolic conditions. Journal of clinical investigation, 113: 115-23. 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foletta VC, White LJ, Larsen AE, Léger B, Russell AP. The role and regulation of MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in skeletal muscle atrophy. Pflügers Archiv, 61: 325-335. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RA, Nystrom GJ, Jefferson LS, Lang CH. Hormone, cytokine, and nutritional regulation of sepsis-induced increases in atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in skeletal muscle. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism, 292: E501-E512. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DJ. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy signaling pathways. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 37: 1974-1984. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard C, Wilkie RS, Dunn IC. The relationship between insulin-like growth factor-1, growth hormone, thyroid hormones and insulin in chickens selected for growth. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 5: 165-76. 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll DE, Thompson VF, Taylor RG, Christiansen JA. Role of the calpain system in muscle growth. Biochimie, 74: 225-237. 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumucio JP, Mendias CL. Atrogin-1, MurF-1, and sarcopenia. Endicrine, 43: 12-21. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guernec A, Chevalier B, Duclos MJ. Nutrient supply enhances both IGF-1 and MSTN mRNA levels in chcken skeletal muscle. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 26: 143-154. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibuki M, Yoshimoto Y, Inui M, Fukui K, Yonemoto H, Saneyasu T, Honda K, Kamisoyama H. Investigation of the growth-promoting effect of dietary mannanase-hydrolysed copra meal in growing broiler chickens. Animal Science Journal, 85: 562-568. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang CW, Sunde ML, Swick RW. Growth and protein turnover in the skeletal muscles of broiler chicks. Poultry Science, 64: 370-379. 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HL, Santé-Lhoutellier V, Vigouroux S, Briand Y, Briand M. Calpain specificity and expression in chicken tissues. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part B, Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, 146: 88-93. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokireddy S, McFarlane C, Ge X, Zhang H, Sze SK, Sharma M, Kambadur R. Myostatin induces degradation of sarcomeric proteins through a Smad3 signaling mechanism during skeletal muscle wasting. Molecular Endocrinology, 25: 1936-1949. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Long CL, Harverberg LN, Young VR, Kinney JM, Munro HN, Geiger JW. Metabolism of 3-Methylhistidine in man. Metabolism, 24: 929-935. 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Hayashi K, Toyohara S, Hashiguchi T. Variation among chicken stocks in the fractional rates of muscle protein synthesis and degradation. Biochemical Genetics, 22: 687-700. 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness MC, Cogburn LA. Measurement of developmental changes in plasma insulin-like growth factor-I levels of broiler chickens by radioreceptor assay and radioimmunoassay. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 79: 446-58. 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourkioti F, Kratsios P, Luedde T, Song YH, Delafontaine P, Adami R, Parente V, Bottinelli R, Pasparakis M, Rosenthal N. Targeted ablation of IKK2 improves skeletal muscle strength, maintains mass, and promotes regeneration. Journal of clinical investigation, 116: 2945-2954. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neel BA, Lin Y, Pessin JE. Skeletal muscle autophagy: a new metabolic regulator. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 24: 635-643. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka A, Kawatomi N, Nakashima K, Araki T, Hayashi K. Gene expression of muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase, atrogin-1/MAFbx, positively correlates with skeletal muscle proteolysis in food-deprived broiler chickens. Journal of Poultry Science, 48: 92-96. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Radecki SV, Capdevielle MC, Buonomo FC, Scanes CG. Ontogeny of insulin-like growth factors (IGF-I and IGF-II) and IGF-binding proteins in the chicken following hatching. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 107: 109-117. 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiprich K, Mühlbauer E, Decuypere E, Grossmann R. Characterization of growth hormone gene expression in the pituitary and plasma growth hormone concentrations during posthatch development in the chicken. Journal of Endcrinology, 145: 343-353. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez AMJ, Candau RB, Bernardi H. FoxO transcription factors: their roles in the maintenance of skeletal muscle homeostasis. Cell and Molecular Life Sciences, 71: 1657-1671. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandri M, Sandri C, Gilbert A, Skurk C, Calabria E, Picard A, Walsh K, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell, 117: 399-412. 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandri M. Signaling in muscle atrophy and hypertrophy. Physiology, 23: 160-170. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandri M. Protein breakdown in muscle wasting: Role of autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 45: 2121-2129. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saneyasu T, Kimura S, Inui M, Yoshimoto Y, Honda K, Kamisoyama H. Differences in the gene expression involved in skeletal muscle proteolysis during food deprivation between broiler and layer chicks. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 186: 36-42. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiaffino S, Dyer KA, Cicilot S, Blaauw B, Sandi M. Mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle growth and atrophy. FEBS Journal, 280: 4294-4314. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah OJ, Anthony JC, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. 4E-BP1 and S6K1: translational integration sites for nutritional and hormonal information in muscle. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 279: E715-E729. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorimachi H, Tsukahara T, Okada-Ban M, Sugita H, Ishiura S, Suzuki K. Identification of a third ubiquitous calpain species – chicken muscle expresses four distinct calpains. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1261: 381-393. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjögren K, Liu JL, Blad K, Skrtic S, Vidal O, Wallenius V, LeRoith D, Törnell J, Isaksson OG, Jansson JO, Ohlsson C. Liver-derived insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) is the principal source of IGF-I in blood but is not required for postnatal body growth in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96: 7088-7092. 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawan A, Davis TA. Regulation of protein degradation pathways by amino acids and insulin in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 5: 8 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesseraud S, Peresson R, Chagneau A.M. Age-related changes of protein turnover in specific tissues of the chick. Poultry Science, 75: 627-631. 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesseraud S, Métayer S, Duchêne S, Bigot K, Grizard J, Dupont J. Regulation of protein metabolism by insulin: value of different approaches and animal models. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 33: 123-142. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaudin P, Dupont J, Duchêne S, Audouin E, Crochet S, Berri C, Tesseraud S. Phosphatase PTEN in chicken muscle is regulated during ontogenesis. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 31: 123-140. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakar S, Liu JL, Stannard B, Butler A, Accili D, Sauer B, LeRoith D. Normal growth and development in the absence of hepatic insulin-like growth factor I. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96: 7324-7329. 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka I, Mikura M, Nishimura M, Doi M, Kawano Y, Nakayama M. Enhancement of myofibrillar proteolysis following infusion of amino acid mixture correlates positively with elevation of core body temperature in rats. Journal of Nutrition and Vitaminolgy, 54: 467-474. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Semprun-Prieto L, Sukhanov S, Delafontaine P. IGF-1 prevents ANG II-induced skeletal muscle atrophy via Akt- and Foxo-dependent inhibition of the ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 expression. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology, 298: H1565-H1570. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young VR, Alexis SD, Baliga BS, Munro HN, Muecke W. Metabolism of administered 3-methylhistidine. Lack of muscle transfer ribonucleic acid charging and quantitative excretion as 3-methylhistidine and its N-acetyl derivative. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 247: 3592-3600. 1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]