Abstract

Objective:

There is an urgent need to understand high HIV-infection rates among young women in sub-Saharan Africa. While age-disparate partnerships have been characterised with higher risk sexual behaviours, the mechanisms through which these partnerships may increase HIV-risk are not fully understood. This study assessed the association between age-disparate partnerships and herpes simplex virus type-2 (HSV-2) infection, a factor known to increase HIV-infection risk.

Methods:

Cross-sectional face-to-face questionnaire data, and laboratory HSV-2 and HIV antibody data were collected among a representative sample in the 2014/15 household survey of the HIV Incidence Provincial Surveillance System (HIPSS) in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Among 15–24 year-old women who reported having ever had sex (N=1550), the association between age-disparate partnerships (ie, male partner ≥5 years older) and HSV-2 antibody status was assessed using multivariable Poisson regression models with robust variance. Analyses were repeated among HIV-negative women.

Results:

HSV-2 prevalence was 55% among 15–24 year-old women. Women who reported an age-disparate partnership with their most recent partner were more likely to test HSV-2 positive compared to women with age-similar partners (64% vs 51%; adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR):1.19 (95% CI: 1.07–1.32, p<0.01)). HSV-2 prevalence was also significantly higher among HIV-negative women who reported age-disparate partnerships (51% vs 40%; aPR:1.25 (95% CI:1.05–1.50, p=0.014)).

Conclusions:

Results indicate that age-disparate partnerships are associated with a greater risk of HSV-2 among young women. These findings point towards an additional mechanism through which age-disparate partnerships could increase HIV-infection risk. Importantly, by increasing HSV-2 risk, age-disparate partnerships have the potential to increase HIV-infection risk within subsequent partnerships, regardless of the partner age-difference in those relationships.

Keywords: intergenerational partnerships, age discordant partners, herpes simplex virus type 2, HIV prevention, young women, sub-Saharan Africa

INTRODUCTION

HIV-infection rates among young women in sub-Saharan Africa remain among the highest of any population globally.1 Adolescent girls and young women (15–24 years old) accounted for approximately one quarter of new HIV infections among adults in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015.2 In South Africa alone, approximately 2,000 new infections occurred weekly among 15–24 year-old women in 2016.3 A better understanding of factors that influence young women’s HIV infection risk is critical for the success of efforts to reduce the burden of disease among this population.

Conflicting evidence has generated uncertainty about the role that age-disparate partnerships (ie, those in which the male partner is 5 or more years older) play in young women’s HIV risk.4–9 While a recent study found that age-disparate partnerships increase risk of HIV-acquisition for young women,4 and several others demonstrate a positive association between age-disparate partnerships and living with HIV,5–7 other studies found a lack of evidence that these partnerships increase HIV acquisition risk.8,9 Consistent with the hypothesis that age-disparate partnerships do increase HIV-infection risk, studies have demonstrated that young women’s age-disparate partnerships are more likely to involve riskier sexual behaviours,10–12 and male partners who are more likely to be HIV-positive and have an unsuppressed viral load.13 However, little is known about the relationship between other biological risk factors for HIV and age-disparate partnerships.

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) significantly increases HIV-infection risk.14 HSV-2 is an incurable sexually transmitted infection, which is positively associated with age among both men and women.15,16 As HSV-2 prevalence among men (15–49) is typically higher among older compared to younger men, one would expect that young women in partnerships with older men would be more likely to acquire HSV-2 than their peers in partnerships with similar-aged partners. However, few studies have documented a positive association between HSV-2 risk among women and age-differentials between women and their male partners. In one study among adults reporting multiple sexual partners in the past year in the United States of America, age-mixing (ie, sex with people outside of one’s age group) was positively associated with HSV-2.17 Among pregnant Zimbabwean women of all ages, HSV-2 infection was more likely among women with older partners.18 In South Africa, a study conducted in 1999 that assessed the association between partner concurrency and HSV-2 among 14–24 year-old women found that having an older partner was significantly associated with HSV-2 infection.19 These studies were either conducted in the earlier stages of the HIV epidemic or among adult women in general and there is accordingly a paucity of current evidence on the interplay between age-disparate partnerships and HSV-2 risk among young women. Moreover, due to the bi-directionality of the relationship between HSV-2 and HIV,20 and the lack of biomarker data in many previous studies on both HIV and HSV-2, little is known about the role of age-disparate partnerships in HSV-2 infection among HIV-negative women.

In this study, we assessed the association between age-disparate partnerships and HSV-2 among 15–24 year-old women living in an HIV hyper-endemic setting in South Africa. To assess the potential for age-disparate partnerships to increase future risk of HIV infection, via an increased risk of HSV-2 infection, we examined whether HIV-negative women who reported age-disparate partnerships were more likely to have HSV-2.

METHODS

Data

This study used data from the first baseline survey conducted from June 2014 to June 2015 for the HIV Incidence Provincial Surveillance System (HIPSS).21 This cross-sectional household-based survey was conducted in two areas (Vulindlela (rural) and Greater Edendale (urban)) of the uMgungundlovu district in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Households were randomly selected using a multi-stage random sampling of enumeration areas (EA), households and individuals. One individual per household, within the age range 15–49 years, was randomly selected from a roster of eligible household members. A total of 9812 individuals were enrolled. Overall, 2144 (14.7%) households and 577 (5.1%) individuals refused participation.

Venous blood samples were collected from all participants for HSV-2 and HIV antibody tests. A face-to-face questionnaire was administered to collect data on, inter alia, demographics, socioeconomic status, and health related information. Details on participants’ first and three most recent sexual partners were recorded. Specifically, the introduction to questions on recent partnerships read ‘Now I am going to ask you more details about the 3 most recent partners that you have had sex with. Please tell me about them starting with the most recent (newest) partner.’ Data were collected on participants’ last three partners regardless of timeframe.

HSV-2 testing was conducted using HSV-2 ELISA (Kalon, Guildford, United Kingdom). HIV testing was done using fourth generation HIV enzyme immunoassays to test for HIV antibodies and antigens using enzyme Biomerieux Vironostika Uniform II Antigen / Antibody Microelisa system (BioMérieux, Marcy I’Etoile, France) and HIV 1/2 Combi Roche Elecys (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany). Positive HIV-tests were confirmed with a Western-Blot (Biorad assay, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Redmond, WA 98052, USA). All tests were performed by an accredited laboratory (via the South African National Accreditation System) according to the manufacturers’ manuals and were validated in the laboratories that were conducting the testing.

The study was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee, University of KwaZulu-Natal, (BF269/13), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States of America, and by the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Department of Health in South Africa (HRKM 08/14). Eligible participants provided informed written consent prior to study enrolment. All study procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Measures

All study participants were asked the age of their three most recent sexual partners. Based on the The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) definition,22 and consistent with the literature, age-disparate partnerships were defined as those in which the male partner was 5 or more years older. Partnerships in which women were >2 years older than their partner were rare (eg, only 0.7% of the most recent partnerships reported by 15–24 year old women) and were coded as age-similar partnerships. Our primary measure of age-disparate partnering was a binary variable created to identify women who reported an age-disparity in their most recent partnership.

Intergenerational partnerships (ie, those with an age-gap between partners of 10 or more years) have been a specific target of HIV prevention campaigns in South Africa. Accordingly, we created an additional variable with a category to represent women with age-similar partners, and separate categories to represent women with age-disparate partners within different age-ranges: 1) male partners 5–9 years older, and 2) male partners 10 or more years older.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted with Stata 15 (Stata Corporation LP, College Station, TX). All analyses used sampling weights. The weights accounted for the multi-stage cluster sampling survey design and for non-response, and were rescaled to the size of the population in the survey area with the Statistics South Africa 2011 Census population. Details on the sampling weights are presented in online supplementary file 1. Descriptive statistics with unweighted counts and population-weighted percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented. All analyses were restricted to women who reported ever having had sex, and women with complete data on HSV-2 status and their most recent partner’s age.

Differences in the prevalence of HSV-2 by partnership type (age-similar vs age-disparate) were assessed in a bivariate analysis using chi-squared tests. Multivariable Poisson regression models with robust variance,23 were used to assess the association between HSV-2 status and our primary independent variable: a binary variable for whether a participant’s most recent partnership was age-disparate or not. Adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) are presented. Models controlled for factors that could be correlated with both the dependent variable and the formation or dissolution of age-disparate partnerships (past and present). Control variables in all models included age of the woman (years); education; monthly household income; number of lifetime sexual partners; whether the participant reported using condoms at first sex; and age at first sex. Given 23% (n=352) of our sample had missing data on age at first sex, for this control measure we used a categorical variable based on quartiles (1=younger than 17 years old, 2=17 years old, 3=18 or 19 years old, 4=20–24 years old), with an additional fifth category representing individuals with missing data.

To assess whether the association between HSV-2 status and age-disparate partnering varied between age-disparate partnerships with different age-differentials (partners 5–9 year older and partners ≥10 years older), we repeated the regression models using our categorical measure of age-disparate partnering instead of the binary measure.

As the relationship between HSV-2 and HIV is bi-directional,20 we repeated all analyses with the sample of HIV-negative women to assess the association between age-disparate partnerships and HSV-2 positivity independent of HIV status. This analysis provides an indication of the potential for age-disparate partnerships, via increasing the risk of HSV-2 infection, to increase future risk of HIV infection.

Given that HSV-2 infection may have occurred in partnerships preceding the most recent partnership, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with the binary independent variable in all models identifying women who reported an age-disparity in any of their three most recent partnerships. In all regression analyses, standard errors were adjusted for clustering at the enumeration area level to account for all potential within-cluster error correlation.

RESULTS

Sample of 15–24 year-old women

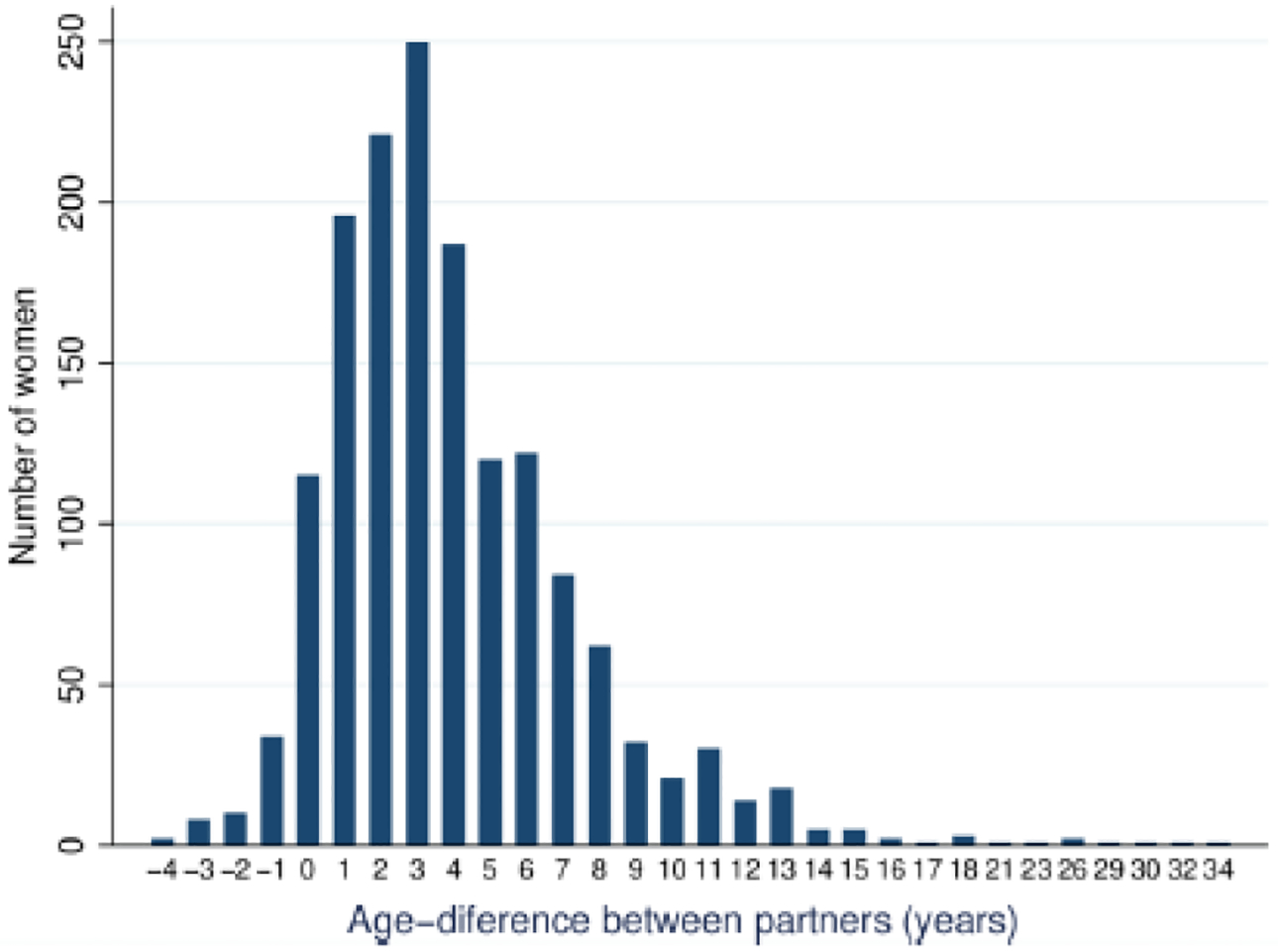

A total of 1550 women aged 15–24 years old were included in our analysis. The following exclusions were made from the initial HIPSS sample of 2224 women in this age group: 667 women reported never having had sex, 1 woman was missing data on her most recent partner’s age, and 6 women were missing data on HSV-2 status. Sample characteristics for the 1550 women included in this analysis are presented in Table 1. The majority (67.5%) were 20–24 years old, and the average age was 20.6 years old. The population-weighted HSV-2 prevalence was 55.3% (95% CI: 52–59). 31.8% (95% CI: 28.3–35.3) reported that their most recent partnership involved an age-disparate partner, while 36.1% (95% CI: 32.5–39.6) reported at least one age-disparate partner among their three most recent partnerships. Among women’s most recent partners, 29.2% (95% CI: 26.2–32.2) were 5–9 years older than they were, and 6.9% (95% CI: 5.3–8.5) were 10 or more years older. The distribution of age-differences between partners in the most recent partnership reported by women is presented in Figure 1. Among the HIV-negative 15–24 year-old women (N=1059), 29.2% (95% CI: 25.4–32.9) had an age-disparate partner in their last partnership. HSV-2 prevalence among the HIV-negative women in our sample was 43.5% (95% CI: 39.6–47.3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample of 15–24 year-old women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa (2014/15)

| Women 15–24 years old who reported a sexual partnership | HIV-negative women (15–24 years old) who reported a sexual partnership | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | Population-weighted % (95% CI) | n/N | Population-weighted % (95% CI) | |

| Black African | 1549/1550 | 100 (99.9–100) | 1058/1059 | 99.9 (99.9–100) |

| Age categories | ||||

| 15–19 | 453/1550 | 32.5 (29.4–35.7) | 366/1059 | 37.9 (33.7–42.2) |

| 20–24 | 1097/1550 | 67.5 (64.3–70.1) | 693/1059 | 62.1 (57.9–66.3) |

| Education completed^ | ||||

| <secondary | 55/1550 | 3.0 (1.8–4.2) | 25/1059 | 1.7 (0.8–2.6) |

| some secondary | 611/1550 | 41.4 (38.1–44.7) | 404/1059 | 40.7 (36.8–44.5) |

| grade 12 | 786/1550 | 50.1 (46.6–53.5) | 555/1059 | 51.8 (47.8–55.7) |

| tertiary | 98/1550 | 5.5 (3.8–7.2) | 75/1059 | 5.8 (4.0–7.6) |

| Household monthly income^ | ||||

| <R500 | 319/1419 | 16.5 (13.0–20.0) | 202/969 | 15.1 (11.3–18.8) |

| R501-R2500 | 711/1419 | 48.6 (44.5–52.7) | 489/969 | 48.4 (43.3–53.4) |

| R2501-R6000 | 303/1419 | 27.3 (23.4–31.2) | 210/969 | 28.6 (24.3–32.9) |

| >R6000 | 86/1419 | 7.5 (5.1–10.0) | 68/969 | 8.0 (5.2–10.7) |

| HSV-2 positive | 875/1550 | 55.3 (52.1–58.6) | 460/1059 | 43.5 (39.6–47.3) |

| HIV positive | 491/1550 | 29.5 (26.8–32.1) | 0/1059 | 0 |

| Lifetime sexual partners^ | ||||

| 1 | 768/1428 | 47.5 (43.5–51.4) | 517/985 | 53.0 (48.5–57.4) |

| 2 | 351/1428 | 24.4 (21.3–27.5) | 242/985 | 24.6 (20.6–28.6) |

| 3 | 214/1428 | 16.0 (13.4–18.6) | 118/985 | 13.2 (10.4–16.1) |

| 4 or more | 203/1428 | 12.1 (10.0–14.2) | 108/985 | 9.3 (7.1–11.4) |

| Condom used at first sex | ||||

| no | 1079/1550 | 69.5 (66.2–72.8) | 734/1059 | 69.2 (65.4–72.9) |

| yes | 416/1550 | 28.0 (24.6–31.4) | 287/1059 | 28.7 (24.9–32.5) |

| do not remember | 55/1550 | 2.5 (1.6–3.4) | 38/1059 | 2.1 (1.2–2.9) |

| Last partner age-disparate | ||||

| ≥5 years older | 527/1550 | 31.8 (28.3–35.3) | 325/1059 | 29.2 (25.4–32.9) |

| 5–9 years older | 420/1550 | 25.9 (23.1–28.8) | 269/1059 | 24.6 (21.2–28.0) |

| ≥10 years older | 107/1550 | 5.9 (4.3–7.4) | 56/1059 | 4.5 (2.7–6.4) |

| Any of last 3 partners age-disparate | ||||

| ≥5 years older | 581/1550 | 36.1 (32.5–39.6) | 356/1059 | 32.6 (28.8–36.4) |

| 5–9 years older | 457/1550 | 29.2 (26.2–32.2) | 293/1059 | 27.4 (23.9–31.0) |

| ≥10 years older | 124/1550 | 6.9 (5.3–8.5) | 63/1059 | 5.2 (3.3–7.1) |

The N for these variables varies from the total sample size due a small amount of missing data.

Figure 1.

The distribution of age-differences between partners for the most recent partnership reported by 15–24 year-old women. Positive numbers indicate partnerships in which the male partner was older.

HSV-2 among all women

The population-weighted HSV-2 prevalence was greater among women who reported their last partnership as age-disparate, compared to those reporting a partnership age-gap of <5 years (64% vs 51%; prevalence ratio (PR):1.24, p<0.01). Results were substantively similar after controlling for potential confounders (Table 2, Model 2: aPR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.07–1.32, p<0.01). The full multivariable Poisson regression models, including coefficients for the control variables, are presented in online supplementary file 2, Table S1.

Table 2.

Poisson regression models of the association between HSV-2 and partner age-gap within the most recent partnerships reported by 15–24 year-old women in KwaZulu-Natal South Africa (2014/15)

| model number | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dependent variable | HSV-2 | HSV-2 | HSV-2 | HSV-2 |

| PR (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI) | |

| Partnership age-gap (ref: <5 years) | ||||

| ≥5 years | 1.24*** | 1.19*** | ||

| (1.13 – 1.37) | (1.07 – 1.32) | |||

| 5–9 years | 1.22*** | 1.18*** | ||

| (1.11 – 1.34) | (1.06 – 1.32) | |||

| ≥10 years | 1.35*** | 1.24** | ||

| (1.11 – 1.64) | (1.00 – 1.53) | |||

| ^Control variables | no | yes | no | yes |

| Observations | 1,550 | 1,550 | 1,550 | 1,550 |

Notes:

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1.

PR: unadjusted prevalence ratio; aPR: adjusted prevalence ratio; 95% CI: 95% Confidence interval.

Robust standard errors, clustered at the enumeration area level.

See Supplementary File 2, Table S1, for the full multivariable Poisson regression models presented in column 2 & 4, including coefficients for the control variables in each model.

Control variables in all models included age of the woman (years); education; monthly household income; number of lifetime sexual partners; whether the participant reported using condoms at first sex, and age at first sex.

Analysis based on separate categories of age-disparate partners (Table 2, Model 4) found a significant, positive association between HSV-2 and both 1) women who reported a partner 5–9 years older (aPR:1.18, 95% CI: 1.06–1.32, p=0.003), and 2) women who reported an intergenerational partnership (aPR:1.24, 95% CI: 1.00–1.53, p=0.05). The relatively wide 95% confidence interval is reflective of the small percentage of partnerships involving male partners ≥10 years older than participants. The coefficients for the category with partners 5–9 years older and for the category with partners ≥10 years older (ie, intergenerational partnership) were not significantly different from one another.

HSV-2 among HIV-negative women

The population-weighted prevalence of HSV-2 among 15–24 year-old HIV-negative women was 43.5% (95% CI:39.6–47.3). The weighted prevalence of HSV-2 was 51% among women who reported their most recent partner as age-disparate and 40% among women with age-similar partners (PR:1.26, 95% CI: 1.06–1.50, p=0.010). After controlling for potential confounding factors, HIV-negative women reporting age-disparate partnerships were significantly more likely to test HSV-2 positive (aPR:1.25, 95% CI: 1.05–1.50, p=0.014) compared to HIV-negative women with age-similar partners.

Comparing HIV-negative women in age-similar partnerships to different categories of age-disparate partnering (Table 3, Model 4), the adjusted prevalence ratio was 1.45 (95% CI:0.98–2.13, p=0.061) for women who reported a partner ≥10 years older; and 1.22 (95% CI:1.01–1.47, p=0.041) for women who reported a partner 5–9 years older. The coefficients for the category with partners 5–9 years older and for the category with partners ≥10 years older were not significantly different from one another.

Table 3.

Poisson regression models of the association between HSV-2 and partner age-gap within the most recent partnerships reported by HIV-negative 15–24 year old women in KwaZulu-Natal South Africa (2014/15)

| model number | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dependent variable | HSV-2 | HSV-2 | HSV-2 | HSV-2 |

| PR (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI) | |

| Partnership age-gap (ref: <5 years) | ||||

| ≥5 years | 1.26*** | 1.25** | ||

| (1.06 – 1.50) | (1.05 – 1.50) | |||

| 5–9 years | 1.23** | 1.22** | ||

| (1.03 – 1.47) | (1.01 – 1.47) | |||

| ≥10 years | 1.43* | 1.45* | ||

| (0.98 – 2.08) | (0.98 – 2.13) | |||

| ^Control variables | no | yes | no | yes |

| Observations | 1,059 | 1,059 | 1,059 | 1,059 |

Notes:

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1.

PR: unadjusted prevalence ratio; aPR: Adjusted prevalence ratio; 95% CI: 95% Confidence interval.

Robust standard errors, clustered at the enumeration area level.

See Supplementary File 2, Table S2, for the full multivariable regression models presented in column 2 & 4, including coefficients for the control variables in each model.

Control variables in all models included age of the woman (years); education; monthly household income; number of lifetime sexual partners; whether the participant reported using condoms at first sex, and age at first sex.

The sensitivity analysis using age-disparate measures based on data from women’s three most recent partnerships (see supplementary file 2, Tables S3 and S4), showed substantively similar results. A total of 196 women (12.6%) provided data on more than one sexual partnership. Among the full sample, women who reported an age-disparity in any partnership were more likely to test HSV-2 positive (aPR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.06–1.32, p<0.01). A positive association between HSV-2 and report of any age-disparate partnership was also found among the subset of HIV-negative women (aPR:1.21, 95% CI:1.02–1.45, p=0.034).

DISCUSSION

The high prevalence of HSV-2 among women globally,24 together with its negative impact on sexual and reproductive health, including HIV-infection risk,14 underscores the importance of understanding factors that increase young women’s HSV-2 risk. This study found a high prevalence of HSV-2 infection (55%) among 15–24 year-old women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, who reported having had sex. High HSV-2 prevalence has previously been found in general population surveys of young women in South Africa, with 53% prevalence among 14–24 year-old women in a mining town in Gauteng province,25 and recent estimates of 28.7% HSV-2 prevalence among 15–24 year-old women in rural KwaZulu-Natal.26

Our study found that age-disparate partnerships were common among young women, which is consistent with previous South African studies,5 and that age-disparate partnerships were positively associated with HSV-2. Results were similar among the subset of HIV-negative women. A positive association between age-disparate partnerships and HSV-2 risk is consonant with results from several studies showing that a range of risky sexual behaviours, including condomless sex, transactional sex, and concurrent sexual partnering, is more prevalent in age-disparate partnerships.10,11 Study findings also align with those from a previous analysis of the survey data used in this study (ie, of 15–24 year-old women participating in the 2014/15 HIPSS survey), which found that women who reported age-disparate partnerships were significantly more likely to have HIV than women who reported only age-similar partners.13

Our findings further indicate the need for interventions to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections within age-disparate partnerships. Such interventions will need to be multidimensional given the complex array of motives that prompt men and women to engage in age-disparate partnerships.27 Structural interventions to improve economic well-being may reduce risks from age-disparate partnerships among women where these partnerships are motivated by financial or material gain. In one promising study, for example, a randomised controlled trial testing the efficacy of a cash transfer programme to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections in young women (13–22) in Malawi, found that receipt of monthly cash amounts was associated with a significantly lower prevalence of HSV-2, as well as with a lower prevalence of sex with a partner aged 25 years or older.28 Interventions to improve early STI-screening, including HIV-diagnosis, among 25–34 year old men may also be effective in reducing risks associated with age-disparate partnerships.

Moreover, findings point towards an additional mechanism through which age-disparate partnerships could increase HIV-infection risk. As HSV-2 significantly increases HIV-infection risk,14 age-disparate partnerships may increase risk of HIV acquisition by increasing HSV-2 prevalence among HIV-negative women. Our findings therefore indicate a mechanism through which age-disparate partnerships could increase HIV-infection risk within both current and subsequent partnerships, regardless of the partner age-difference in future relationships. Further research on the influence of age-disparate partnerships on HIV risk should consider the interplay between age-disparate partnerships, HSV-2, and HIV risk.

These results should be interpreted in the context of the study limitations. While the use of biomedical data reduces the potential for social desirability bias on the key dependent variables, it is possible that social desirability bias, recall bias and incorrect knowledge might have resulted in misreporting, and incomplete reporting of partnership data. In particular, we had incomplete data on women’s second or third most recent partners, which is a common problem in surveys.29 Among women in our sample who reported more than one lifetime partner (n=768), 25% provided data on multiple partnerships. While the intention was to collect data on participants’ last three partners regardless of timeframe, the use of the term ‘recent’ in the request for details about participants’ three ‘most recent partners’ may have resulted in a failure to consider partnerships that ended several months prior to the survey. This limitation may have influenced the results from our sensitivity analysis. There is also the potential of misreporting the age of partners,30 and therefore measurement error in identifying age-disparate partnerships. While we controlled for several potential confounding factors, there is the potential that unmeasured factors, such as risk-taking preferences, might have confounded results. The size and direction of this bias is unclear. Furthermore, the timing of HSV-2 infection within our sample is unknown, which prevents causal inference regarding the effect of age-disparate partnerships on a young woman’s HSV-2 infection risk. Further research is required using longitudinal data that can precisely identify the chronological sequence for the formation of age-disparate partnerships, HSV-2 infection, and HIV infection among young women.

Overall, the results of this study suggest that addressing the additional sexual and reproductive health risks posed to young women by age-disparate partnerships could produce substantial health gains. Interventions targeting the risk factors associated with age-disparate partnerships could potentially reduce both HSV-2 and HIV incidence among adolescent girls and young women.

Supplementary Material

Key messages.

A positive association was found between age disparate partnerships and the likelihood of testing HSV-2 positive among 15–24 year-old women.

HSV-2 prevalence was also significantly higher among HIV-negative women who reported age-disparate partnerships.

Study findings point towards an additional mechanism through which age-disparate partnerships could increase HIV-infection risk.

By increasing HSV-2 risk, age-disparate partnerships have the potential to increase HIV-infection risk within subsequent partnerships, regardless of the partner age-difference in those relationships.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants of the HIV Incidence Provincial Surveillance System (HIPSS), as well as HIPSS co-investigators and members of the HIPSS study team from the following organisations: Epicentre, CAPRISA, HEARD, NICD and CDC. We thank the HIPSS collaborating partners: The National Department of Health, Provincial KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health, uMgungundlovu Health District, the uMgungundlovu District AIDS Council, local municipal and traditional leaders, and community members for all their support throughout the HIPPS study. We are extremely grateful to Kassahun Ayalew, Kaymarlin Govender and Marelize Van Wyk for valuable feedback on previous versions of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest and source of funding

We have no conflicts of interest to declare. The HIV Incidence Provincial Surveillance System (HIPSS) is funded by a cooperative agreement (3U2GGH000372) between Epicentre and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Support was provided to BMB by the National Research Foundation, South Africa, through the Research Career Advancement Fellowship. ABMK is supported by a joint South Africa–U.S. Program for Collaborative Biomedical Research, National Institutes of Health grant (R01HD083343). The contents of this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harrison A, Colvin CJ, Kuo C, et al. Sustained High HIV Incidence in Young Women in Southern Africa: Social, Behavioral, and Structural Factors and Emerging Intervention Approaches. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2015;12:207–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update 2016. Geneva, UNAIDS; 2016. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/global-AIDS-update-2016_en.pdf (accessed 12 February 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.South African National AIDS Council. Let Our Actions Count. Republic of South Africa National Department of Health; 2017. http://nsp.sanac.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Final-NSP-Document.pdf (accessed 12 February 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaefer R, Gregson S, Eaton JW, et al. Age-disparate relationships and HIV incidence in adolescent girls and young women: evidence from Zimbabwe. AIDS 2017;31:1461–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans M, Risher K, Zungu N, et al. Age-disparate sex and HIV risk for young women from 2002 to 2012 in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beauclair R, Helleringer S, Hens N, et al. Age differences between sexual partners, behavioural and demographic correlates, and HIV infection on Likoma Island, Malawi. Scientific Reports 2016;6:36121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pettifor A, Rees H, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Young people’s sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS 2005;19:1525–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harling G, Newell M-L, Tanser F, et al. Do Age-Disparate Relationships Drive HIV Incidence in Young Women? Evidence from a Population Cohort in Rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66:433–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balkus JE, Nair G, Montgomery ET, et al. Age-Disparate Partnerships and Risk of HIV-1 Acquisition Among South African Women Participating in the VOICE Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;70:212–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maughan-Brown B, Evans M, George G. Sexual Behaviour of Men and Women within Age-Disparate Partnerships in South Africa: Implications for Young Women’s HIV Risk. PLoS ONE 2016;11:e0159162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beauclair R, Kassanjee R, Temmerman M, et al. Age-disparate relationships and implications for STI transmission among young adults in Cape Town, South Africa. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2012;17:30–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volpe E, Hardie T, Cerulli C, et al. What’s Age Got to Do With It? Partner Age Difference, Power, Intimate Partner Violence, and Sexual Risk in Urban Adolescents. J Interpers Violence 2013;28:2068–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maughan-Brown B, George G, Beckett S, et al. HIV Risk Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in Age-Disparate Partnerships. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;78:155–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Looker KJ, Elmes JAR, Gottlieb SL, et al. Effect of HSV-2 infection on subsequent HIV acquisition: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:1303–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniels B, Wand H, Ramjee G. Prevalence of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2) infection and associated risk factors in a cohort of HIV negative women in Durban, South Africa. BMC Research Notes 2016;9:510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okuku HS, Sanders EJ, Nyiro J, et al. Factors Associated With Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Incidence in a Cohort of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1-Seronegative Kenyan Men and Women Reporting High-Risk Sexual Behavior. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:837–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catania JA, Binson D, Stone V. Relationship of sexual mixing across age and ethnic groups to herpes simplex virus-2 among unmarried heterosexual adults with multiple sexual partners. Health Psychology 1996;15:362–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munjoma MW, Kurewa EN, Mapingure MP, et al. The prevalence, incidence and risk factors of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection among pregnant Zimbabwean women followed up nine months after childbirth. BMC Women’s Health 2010;10:243–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenyon C, Colebunders R, Buve A, et al. Partner-concurrency associated with herpes simplex virus 2 infection in young South Africans. Int J STD AIDS 2013;24:804–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnabas RV, Celum C. Infectious co-factors in HIV-1 transmission herpes simplex virus type-2 and HIV-1: new insights and interventions. Curr HIV Res 2012;10:228–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kharsany AB, Cawood C, Khanyile D, et al. Strengthening HIV surveillance in the antiretroviral therapy era: rationale and design of a longitudinal study to monitor HIV prevalence and incidence in the uMgungundlovu District, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UNAIDS. UNAIDS Terminology Guidelines. UNAIDS; 2015. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2015_terminology_guidelines_en.pdf (accessed 12 February 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:761–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Looker KJ, Magaret AS, Turner KME, et al. Global Estimates of Prevalent and Incident Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Infections in 2012. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e114989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auvert B, Ballard R, Campbell C, et al. HIV infection among youth in a South African mining town is associated with herpes simplex virus-2 seropositivity and sexual behaviour. AIDS 2001;15:885–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francis SC, Mthiyane TN, Baisley K, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among young people in South Africa: A nested survey in a health and demographic surveillance site. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Age-disparate Leclerc-Madlala S. and intergenerational sex in southern Africa: the dynamics of hypervulnerability. AIDS 2008;22:S17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baird SJ, Garfein RS, McIntosh CT, et al. Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2012;379:1320–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maughan-Brown B, Venkataramani A. Measuring concurrent partnerships: potential for underestimation in UNAIDS recommended method. AIDS 2011;25:1549–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harling G, Tanser F, Mutevedzi T, et al. Assessing the validity of respondents’ reports of their partners’ ages in a rural South African population-based cohort. BMJ Open 2015;5:e005638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.