Abstract

The Silencing Mediator of Retinoid and Thyroid Hormone Receptors (SMRT) is a nuclear corepressor, regulating the transcriptional activity of many transcription factors critical for metabolic processes. While the importance of the role of SMRT in the adipocyte has been well-established, our comprehensive understanding of its in vivo function in the context of homeostatic maintenance is limited due to contradictory phenotypes yielded by prior generalized knockout mouse models. Multiple such models agree that SMRT deficiency leads to increased adiposity, although the effects of SMRT loss on glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity have been variable. We therefore generated an adipocyte-specific SMRT knockout (adSMRT-/-) mouse to more clearly define the metabolic contributions of SMRT. In doing so, we found that SMRT deletion in the adipocyte does not cause obesity—even when mice are challenged with a high-fat diet. This suggests that adiposity phenotypes of previously described models were due to effects of SMRT loss beyond the adipocyte. However, an adipocyte-specific SMRT deficiency still led to dramatic effects on systemic glucose tolerance and adipocyte insulin sensitivity, impairing both. This metabolically deleterious outcome was coupled with a surprising immune phenotype, wherein most genes differentially expressed in the adipose tissue of adSMRT-/- mice were upregulated in pro-inflammatory pathways. Flow cytometry and conditioned media experiments demonstrated that secreted factors from knockout adipose tissue strongly informed resident macrophages to develop a pro-inflammatory, MMe (metabolically activated) phenotype. Together, these studies suggest a novel role for SMRT as an integrator of metabolic and inflammatory signals to maintain physiological homeostasis.

Keywords: SMRT, NCoR2, nuclear corepressor, hormone receptor, transcription regulation, gene knockout, adipose tissue, metabolism, inflammation, homeostasis

While the adipocyte was once considered a passive vehicle for energy storage, this one-dimensional understanding has since expanded in light of research demonstrating the active role of adipose tissue in metabolism (1-3). As an endocrine organ, adipocytes collectively express and secrete a vast profile of adipokines that influence a diverse array of metabolic processes (4); as such, adipocyte dysregulation is a major contributor to the pathogenesis of metabolic disease (5-7). In the setting of over-nutrition, for example, adipokine production shifts towards factors that induce insulin resistance (8, 9); while this may be protective from the perspective of the hypertrophic adipocyte by attenuating additional lipid storage, the net effect of insulin resistance is deleterious on a macrophysiological scale (10). In addition to exacerbating the general development of metabolic syndrome, adipocyte insulin resistance itself can have a compounding metabolic consequence by propagating dysregulated lipolysis and release of fatty acids that interfere with signaling in other metabolic tissues (11, 12). Obesity is also characterized by adipose tissue inflammation (13, 14), and it has been shown that metabolically activated (MMe) macrophages, recruited by adipocytes to aid in the clearance of excess lipid, worsen and sustain the pro-inflammatory microenvironment (15, 16). This impairs proper function of the adipocyte, significantly contributing to altered energy storage and utilization (17). While the mechanisms by which the adipocyte regulates the infiltration of MMe macrophages are not fully understood, it is clear that adipocyte endocrine signaling regulates metabolism, both locally and systemically.

Regarding the adipocyte’s ability to maintain homeostasis, it is evident that nuclear cofactors play a critical role by regulating the transcription of metabolically essential genes. For example, the coactivator PGC1α is a master regulator for mitochondrial remodeling (18); when exposed to cold, stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system activates Pgc1α through the PKA/CREB pathway, which in turn strongly induces expression of Ucp1 in brown adipose tissue, thus increasing thermogenesis (19). In white adipose tissue, the Silencing Mediator of Retinoid and Thyroid Hormone Receptors (SMRT, or NCoR2) has been identified as an important factor in the maintenance of metabolic signaling (20). SMRT is a nuclear corepressor, responsible for decreasing the transcriptional activity of its target transcription factors (TFs); in the absence of ligand, TFs complex with SMRT, leading to recruitment of factors with histone deacetylase activity (particularly, HDAC3) at the TF promoter site and, ultimately, transcriptional repression (21, 22). SMRT interacts with a variety of said nuclear receptors (NRs) via so-called CoRNR boxes in its receptor interacting domains (RIDs) (23).

Nearly all genetic models seeking to better understand the molecular and macrophysiological roles of SMRT in vivo have reported metabolic phenotypes with significant increases in weight or adiposity, coupled with alterations in insulin sensitivity and energy expenditure (24). Because of its strong association to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), a powerful effector of adipogenesis, insulin sensitivity, and glucose metabolism (25, 26), phenotypes resulting from perturbations of Smrt are often ascribed to PPARγ derepression. However, while there is clear consensus that SMRT strongly influences metabolism, results from these various knockout and knockin models have led to conflicting conclusions (24). In addition, a ChiP-Seq study by Raghav et al in 3T3-L1 cells suggested that SMRT is not recruited to PPARγ target genes during adipogenesis, and instead regulates 3T3-L1 adipogenesis via effects on KAISO and C/EBPb (27). Thus, the comprehensive role of SMRT in the adipocyte in vivo remains poorly understood, and even its targets remain unclear. For this reason, we generated an adipocyte-specific SMRT knockout (adSMRT-/-) mouse to address our central hypothesis: SMRT regulates metabolic homeostasis in a complex, tissue-specific fashion by integrating signaling from a number of pathways (eg, inflammation, lipid metabolism, etc.), and that it is able to moderate the confluence of various metabolic events through the adipocyte, a major effector of metabolic homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Model generation

Floxed Smrt mice have been reported previously (28). To generate knockout adSMRT-/- mice experimental cohorts, floxed Smrt mice (SMRTloxP/loxP) were crossed with mice hemizygously expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the adiponectin promoter (Adipoq-Cre+/−) [B6.FVB-Tg(Adipoq-cre)1Evdr/J; Jackson Laboratory]. Using this line, Cre is expressed exclusively in white and brown adipose tissue, without activation in resident macrophages. Resulting cohorts were either wild-type (Adipoq-Cre-/- SMRTloxP/loxP) or knockout (Adipoq-Cre−/+ SMRTloxP/loxP). All experimental mice were developed on a C57/B6J strain background, and littermate controls from the cohorts developed were used in experiments. Validation by Western blot utilized primary antibodies anti-AKT (2920S, Cell Signaling) (29), and anti-SMRT (17-10057, Millipore Sigma) (30).

Animal husbandry

Unless otherwise stated, mice used in this study were male, generated on a C57/BL6 background in-house, and fed a standard chow diet until 8 weeks of age, at which point a 45% high-fat diet (HFD) (Teklad Custom Research Diet, TD.06415; Envigo, Madison, WI), matched to our standard chow diet (Teklad Global 18% Protein Diet 2018; Envigo, Madison, WI), was provided ad libitum for 12 weeks. All mice were sacrificed at 20 weeks of age via isoflurane overdose; euthanasia was confirmed via cervical dislocation. Weights were taken weekly, and genotype was determined via PCR using tail clippings obtained at weaning (3 weeks of age). Tissues collected for experimentation were either snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C or immediately used. All mice were housed under standard conditions, and no single-housed mice were used for experimentation. Animals were treated in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Chicago.

Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Tests (IP-GTT)

Following 12 weeks of 45% HFD feeding, mice were fasted for 4 hours, at which point baseline blood glucose readings were obtained from all mice via tail vein blood sampling following application of local anesthetic (2% viscous lidocaine, Water-Jel, Carlstadt, NJ). Dextrose was injected intraperitoneally at a concentration of 1 g/kg body weight. Blood glucose levels were measured at 10, 20, 30, 40, 60, 90, and 120 minutes following injection using a Freestyle Lite Glucometer (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). Percentage difference in blood glucose clearance was determined by measuring and comparing areas under the curve (AUC) between wild-type and knockout.

Adipocyte insulin sensitivity

Primary whole fat tissue from mice fed a 45% HFD was thoroughly minced in KRBH buffer supplemented with 4% endotoxin-free BSA, 0.5 mM glucose, and 1 mM PIA. Adipocytes were then isolated by the addition of T1 Collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, NJ), and subsequent incubation at 37 °C for 30 minutes with agitation (125 rpm). The resultant mixture was passed through a cell filter to remove debris and hand-spun to achieve separation. Adipocytes were placed into clean tubes and washed in BSA-free KRBH to then be treated with increasing doses of 0, 0.5, 1, and 5 nM insulin for 15 minutes. The reaction was halted and samples were prepared for SDS-PAGE via cell lysis by addition of RIPA buffer and subsequent sonication at an amplitude of 40 Hz with an ultrasonic processor (Sonics & Materials, Inc., Newtown, CT). Samples were incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes and then centrifuged at 4 °C at 13 200 rpm for 30 minutes to isolate the infranatant. Protein concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay (23227, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) to standardize protein concentration loaded into gel. After addition of dye, samples were then reduced using 2-mercaptoethanol, boiled for 10 minutes, and analyzed via SDS-PAGE. Insulin sensitivity was determined by pAKT:AKT. Primary antibodies utilized included anti-AKT (2920S, Cell Signaling) (29), and anti-phosphorylated AKT targeting serine 473 (4060S, Cell Signaling) (31).

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

Body composition was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) (Lunar PIXImus densitometer system, GE Healthcare) using PIXImus 2 software. The system was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s instructions prior to the start of the experiment. Mice were anesthetized prior to imaging using a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (80-120 mg/kg body weight of ketamine and 5-10 mg/kg body weight of xylazine injected intraperitoneally).

Metabolic cages

Indirect calorimetric measurements were carried out using the LabMaster System (TSE Systems, Chesterfield, MO) on individually housed mice, maintained under standard housing conditions. Mice were provided ad libitum access to food and water. Following a 2-day acclimation period, O2 consumption, CO2 production, energy expenditure, ambulatory activity, and food/water consumption were monitored over 30-minute periods for 5 consecutive light-dark cycles over. The respiratory exchange ratio (RER) was calculated as the ratio of O2 consumption to CO2 production.

Histology

Adipose tissue samples were fixed for 24 to 48 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. Cassettes containing samples were then washed with and stored in 70% ethanol short-term. Samples were sent to the University of Chicago Human Tissue Resource Center core for sectioning (5 μm), paraffin embedding, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the sections were performed using standard techniques. Images of sections were taken at 10× magnification and adipocyte cell size was analyzed using a custom macro script on Fiji (ImageJ); size was quantified by measuring negative space within cell borders.

RNA sequencing

RNA sequencing (RNAseq) on HFD-fed mice was conducted on a total of 8 mouse perigonadal whole adipose tissue samples, which were collected from either wild-type or knockout age- and weight-matched mice (4 mice/genotype). Following sample homogenization, RNA was collected using a commercially available kit (E.Z.N.A Total RNA Kit, Omega Bio-Tek, GA) per manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were then prepared for RNAseq on the Illumina HiSeq4000 platform and provided to the University of Chicago’s Center for Research Informatics core for sequencing. The quality of raw sequencing reads was assessed using FastQC v0.11.2 (32). Reads were mapped to UCSC mouse genome model (mm10) using STAR v2.4.0g1 (33). Gene transcripts were assembled and quantified on their corresponding mouse genome separately using Cufflinks v2.2.1 (34) with the corresponding RefSeq gene annotation file as a guide for transcript assembly and bias detection/correction. Sample-based assemblies were merged together using Cuffmerge wrapped in Cufflinks v2.2.1 before quantification of transcripts using count-based method featureCounts (35). Differentially expressed genes were identified using count-based methods via edgeR (36, 37). Finally, clusterProfiler, an R/Bioconductor package (38), and IPA were used to conduct functional annotation analyses with identified differentially expressed genes. Raw data were deposited to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (39).

Gut microbiome

Fecal samples were collected from mice at 8, 14, and 20 weeks of age. The harvesting method employed ensured that stool pellets were fresh and did not come into contact with any materials other than the sterile tubes used for collection. All samples were stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from fecal samples using standard, published protocols. Samples were then sequenced by MiSeq at the Next Generation Sequencing Core in the Biosciences Division at Argonne National Laboratory. DNA sequences were analyzed by Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME). Samples with less than 3000 sequences were excluded from the analyses. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were picked at 97% sequence identity using the GreenGenes Database (2013). Analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) was performed using QIIME to examine the impacts of genotype, diet, and age on fecal microbiota. The number of permutations was 10 000 or the maximum number of permutations allowed by the data. Permutation testing with 10 000 permutations was performed using R to compare the UniFrac distances of animals between cohorts.

Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction

Adipocytes and associated stromal vascular fraction (SVF) were isolated from perigonadal fat depots. Adipocyte and SVF isolation followed the same procedure described above for adipocyte isolation in the preparation of Western blot samples, up until hand-spinning. At this point, samples were spun at 300g at 4°C for 8 minutes to separate adipocytes while also pelleting the SVF. RNA was then prepared from each fraction separately using a commercially available kit (Quick-RNA MiniPrep Kit, ZymoResearch, CA). Following analysis for purity and concentration, RNA was then reverse transcribed to cDNA using qScript cDNA mix. Utilizing ThermoFisher’s TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (FAM probes) and the TaqMan Fast Advanced materials (4444964) and protocol for cycling (CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System), all biological replicates were run in triplicate for 11 RNAseq-identified significantly differentially expressed targets. Each plate was repeated once for a total of two technical replicates per biological replicate. 18S Eukaryotic rRNA Endogenous Control was used as a reference gene (4333760F).

Flow cytometry

Fluorochrome labeled cells were analyzed according to the following workflow. Following analysis for cell size and granularity (FSC-A vs SSC-A), a gate for analysis of single cells was applied. Of this population of cells, a gate for live cells was selected (determined by Calcein Blue). From this subset, macrophages were identified by gating for cells that were both CD11b (557396, Abcam) (40) and F4/80 (123117, Abcam) (41) positive. For cells positive for both CD11b and F4/80 (gate applied), M1 macrophages were identified via proinflammatory markers CD38 (562770, BD Biosciences) (42) and CD274 (124313, BD Biosciences) (43), while M2 macrophages were identified via anti-inflammatory markers CD36 (562702, BD Biosciences) (44) and CD206 (565250, BD Biosciences) (45). Analyses were conducted using a Canto-II or LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software v.9.4.11.

Conditioned media

Adipose tissue from wild-type and knockout mice were cultured separately in RPMI serum-free media overnight to obtain conditioned media. Hematopoietic stem-cells were then obtained from the long bones of a young, wild-type male mouse, and plated with L-cell conditioned media for 6 days, followed treatment with adipose tissue–conditioned media at concentrations of 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000 for 24 hours. Macrophages were then collected and processed for RNA isolation and subsequent conversion to cDNA for quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis to determine macrophage differentiation phenotype. Markers used for identifying M1-type cells include Il1b and Tnfα (Mm00434228_m1, Mm00443258_m1); markers used for identifying M2-type cells include Arg1 and Fizz1 (Mm00475988_m1); markers used for identifying metabolically activated MMe-type cells include Abca1 and Plin2 (Mm00442646_m1, Mm00475794_m1). All probes were obtained via Life Technologies, and qRT-PCR was conducted as described.

Statistical analyses

Unless otherwise noted, data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) with statistical significance determined using a 2-tailed, Student t-test to compare wild-type and adSMRT-/- groups. A threshold of P < 0.05 was used to identify statistically significant data. Graph generation and statistical methods were carried out in GraphPad Prism, version 6.0, and Microsoft Excel.

Results

Generation of the adipocyte-specific SMRT knockout (adSMRT-/-) mouse

To define the role of SMRT in the adipocyte, we generated an adipocyte-specific SMRT knockout mouse (adSMRT-/-) by crossing mice homozygously floxed for Smrt (the generation of which is described previously (46)) with mice hemizygously expressing Cre driven by the adiponectin promoter (Fig. 1A). Therefore, half of the resultant offspring lost Smrt expression specifically in adipocytes, as evidenced by a lower molecular weight band (Fig. 1B). Fidelity of the genotype was validated by qRT-PCR analysis of isolated adipocytes and their associated stromal vascular components from primary, mature fat tissue. Here, we observe a significant decrease in Smrt expression of ~80% in the adipocytes of knockout mice compared with wild-type; the associated SVF showed no change in Smrt expression (Fig. 1C), confirming specificity of the model. Western blot analysis confirmed that protein levels of SMRT were specifically decreased in adipose tissue (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Genetics of adSMRT-/- mouse. A: Smrt receives a single loxP site on both alleles, inserted 187 bp downstream of exon 11; mice hemizygously expressing adiponectin-driven Cre excise this site such that a frameshift mutation is introduced, rendering SMRT protein nonfunctional exclusively in adipocytes. B: Mice expressing Cre display 2 bands at ~320bp and ~250bp while wild-type mice display a darker band (2 overlapping bands) at ~320bp; all mice used in this study are floxed on both alleles, displaying a band at ~450bp; Cre+/-, Flox+/+ mice are crossed with Cre-/-, Flox+/+ mice to generate adSMRT-/- mice. C: qRT-PCR model validation shows that adSMRT-/- mice have ~80% reduction in Smrt expression exclusively in adipocytes while the associated stromal vascular fraction remains unaffected. N = 5 per genotype. Data are means ± SEM; *P < 0.01. D: Western blot for SMRT (274 kDa) using nuclear protein extracts from a panel of tissues demonstrates adipose tissue-specific decrease in expression of SMRT in adSMRT-/- (KO) samples compared with wild-type (WT). Total AKT (60 kDa) was measured as a loading control; Abbreviations: BAT, brown adipose tissue; EPIDID, epididymal; SUBCUT, subcutaneous; SVF, stromal vascular fraction;.

Adipocyte-specific loss of SMRT causes metabolic dysregulation without obesity

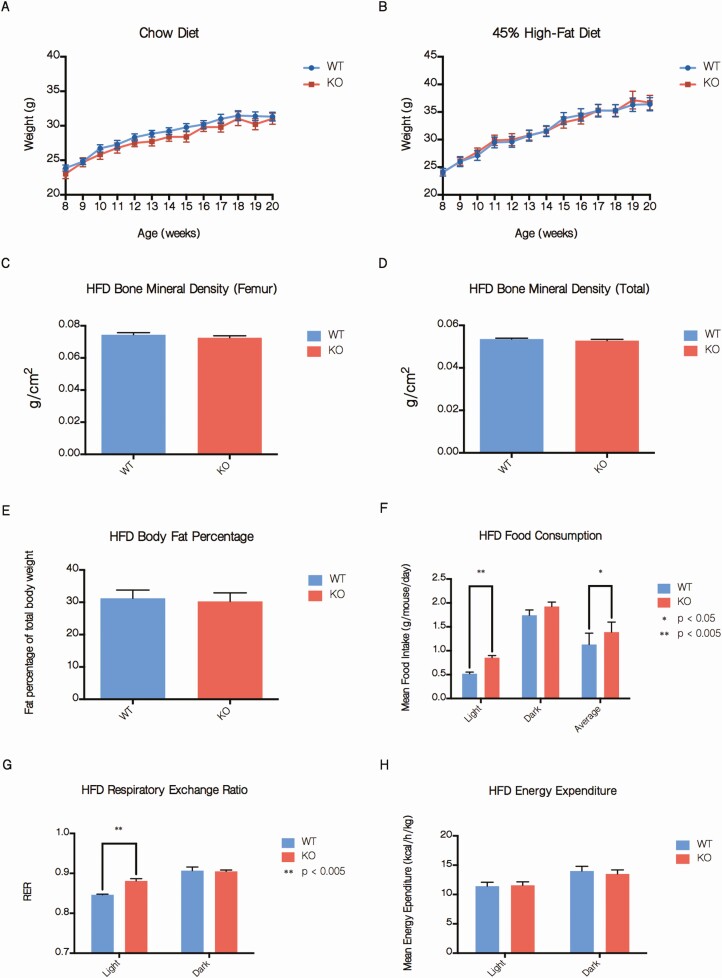

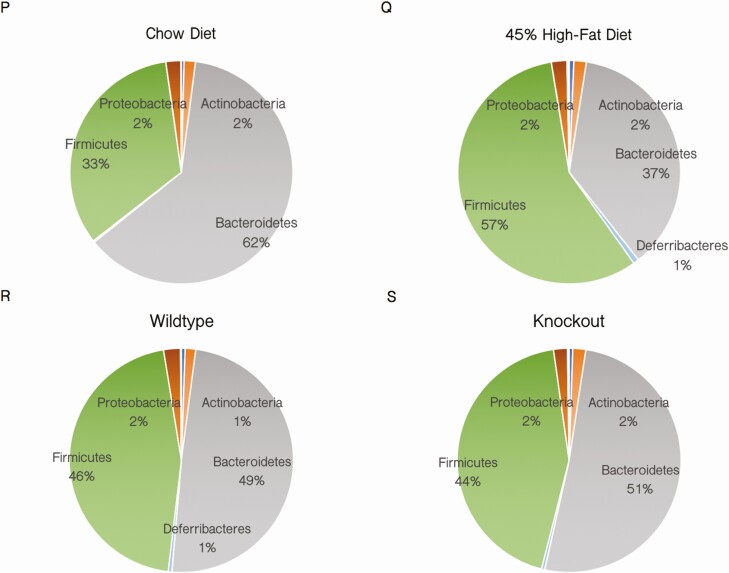

In prior in vivo SMRT models, whether created by knockout or RID knockin mutations, mice demonstrated variable degrees of increased adiposity (24). However, on both 45% HFD and standard chow, no differences in weight were observed between adSMRT-/- and wild-type mice (Fig. 2A and 2B). In addition, DEXA scanning showed no changes in body fat percentage or bone mineral density (Fig. 2C-2E), although metabolic cage studies indicated increased total caloric intake, specifically during the light cycle, as well as increased respiratory exchange ratio (RER) in adSMRT-/- mice (Fig. 2F and 2G); in fact, when analyzing the diurnal RER patterns between genotypes, adSMRT-/- mice demonstrate metabolic inflexibility by an inability to efficiently switch to fat utilization as an energy source (indicated by depressed amplitudes) during the resting light cycle (not shown); this occurred despite no differences in energy expenditure (Fig. 2H). Additionally, we assessed for adipocyte hypertrophy via histological analyses, and found no significant differences in adipocyte size between adSMRT-/- and wild-type mice for both subcutaneous and epidydimal fat tissue (Fig. 2I-2L). Triglyceride content was also unchanged (Fig. 2M and 2N), and adipose tissue leptin expression was similar between wild-type and adSMRT-/- mice (Fig. 2O). We also assessed for any differences in gut flora species; while we found that mice fed a 45% HFD saw a strong shift in the composition of their gut flora from Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes compared with their chow counterparts (the anticipated outcome following HFD feeding), there were no genotype-dependent changes in the microbiome (Fig. 2P-2S).

Figure 2.

adSMRT-/- mice exhibit altered energy consumption and utilization without obesity or hypertrophy. A, B: Total body weight measured weekly between ages 8 and 20 weeks for mice on a chow diet (A) and mice fed a 45% high-fat diet (HFD) (B). N = 15–25 per genotype. Data are means ± SEM. C, D, E: Determinations of femur bone mineral density (C), total bone mineral density (D), and body fat percentage (E) by DEXA scanning for 20-week old mice fed a 45% HFD. N = 10-15 per genotype. Data are means ± SEM. F, G, H: Determinations of average food consumption (F), respiratory exchange ratio (RER) (G), and energy expenditure (H) for 20-week old mice fed a 45% HFD by metabolic cage analysis. N = 4 per genotype. Data are means ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001. I-L: Sample histological sections of H&E-stained subcutaneous (I) and epididymal (J) adipose tissue for mice fed a 45% HFD, and the respective quantifications for adipocyte size via ImageJ quantification of negative space in arbitrary units (K, L). Figure 2. Continued. M, N: Triglyceride quantification of whole adipose tissue from subcutaneous (M) and epididymal (N) depots via colorimetric assay demonstrates no difference in triglyceride concentration. N = 5 per genotype. Data are means ± SEM. O: qRT-PCR expression data from wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) isolated adipocytes show no difference in levels of target leptin (Lep), expressed as fold change from wild-type. N = 5 per genotype. Data are means ± SEM. P-S: Phylum diversity of gut microbiota for mice following 12 weeks of diet, compared by diet (chow vs HFD) (M-N) and genotype (WT vs KO) (O-P). N = 12 per genotype or diet comparison.

adSMRT-/- mice exhibit glucose intolerance

Compared with wild-type mice, adSMRT-/- mice did not develop further obesity when challenged with a 45% HFD; however, SMRT deficiency still negatively impacted adipocyte function and metabolic homeostasis. adSMRT-/- mice fed a 45% HFD displayed significant glucose intolerance by ~20% compared with wild-type, though glucose tolerance remained unaffected between genotypes for mice fed a chow diet (Fig. 3A-3D). Thus, further experiments were exclusively conducted on mice fed a 45% HFD. In fact, adipocytes isolated from adSMRT-/- mice fed a 45% HFD exhibited impaired insulin sensitivity as measured by the ratio of pAKT:AKT signaling following treatment with insulin (Fig. 3E-3H), a result inconsistent with our previous, generalized SMRT+/- mice.

Figure 3.

adSMRT-/- mice are glucose intolerant with insulin resistant adipocytes. A-D: Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests (IP-GTTs) for 20-week old mice fed a chow (A) and 45% high-fat diet (HFD) (B), and their respective area under the curve (AUC) quantifications (C, D). N = 12-13 per genotype for chow GTT data, N = 7-11 for HFD GTT data. Data are means ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005. E, F: Adipocyte insulin sensitivity from mice fed a 45% HFD, determined by Western blotting for pAKT:AKT signaling and, using ImageJ, plotted as a quantification of band intensity in arbitrary units (E), and the respective AUC measurement (F). N = 7 per genotype. Data are means ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005. G, H: Western blots demonstrate insulin resistance in white adipose tissues of knockout (KO) mice compared with wild-type (WT). Following treatment with increasing concentrations of insulin (note different insulin concentration scales used for G, H and E, F), whole-cell protein extracts from subcutaneous (G) and epididymal (H) white adipose tissue were probed for phosphorylated (Ser473) AKT (pAKT, 60 kDa); total AKT (AKT, 60 kDa) was measured as a loading control.

PPARγ derepression fails to explain phenotype

In previously employed mouse models interrogating SMRT, the mechanism driving any phenotypes of weight gain, fat mass expansion, and improved adipocyte insulin sensitivity was thought to be a result of PPARγ derepression due to loss of SMRT (24). However, our phenotype (specifically, no change in weight nor adipocyte size/number, coupled with a decrease in adipocyte insulin sensitivity) suggested that this might not be the case. We therefore assessed the expression of PPARγ target genes Fabp4, Gyk, Pck1, Ucp1, and Cd36 in adSMRT-/- isolated adipocytes by qRT-PCR, and observed no generalized increase in these downstream factors (Fig. 4A-4E); this suggests that altered PPARγ transcriptional activity in adipocytes is not the mechanism for the metabolic effects seen in adSMRT-/- mice. Additionally, when assessing lipogenesis following treatment with radiolabeled glucose and insulin at varying doses, we observed no changes in the ability of adipocytes to incorporate glucose into triglycerides (Fig. 4F), which indirectly supports the idea that PPARγ derepression is not driving our metabolically deleterious phenotype.

Figure 4.

PPARγ derepression fails to explain the phenotype. A-E: qRT-PCR expression data from isolated adipocytes for PPARγ downstream targets Fabp4, Gyk, Pck1, Ucp1, and Cd36. N = 7 per genotype. Data are means ± SEM. F: Lipogenesis assay determining ability of adipocytes to incorporate radiolabeled glucose into triglycerides upon stimulation with insulin; plotted as fold change in radioactivity from baseline. N = 8 per genotype. Data are means ± SEM.

RNA sequencing indicates dysregulation of immune pathways

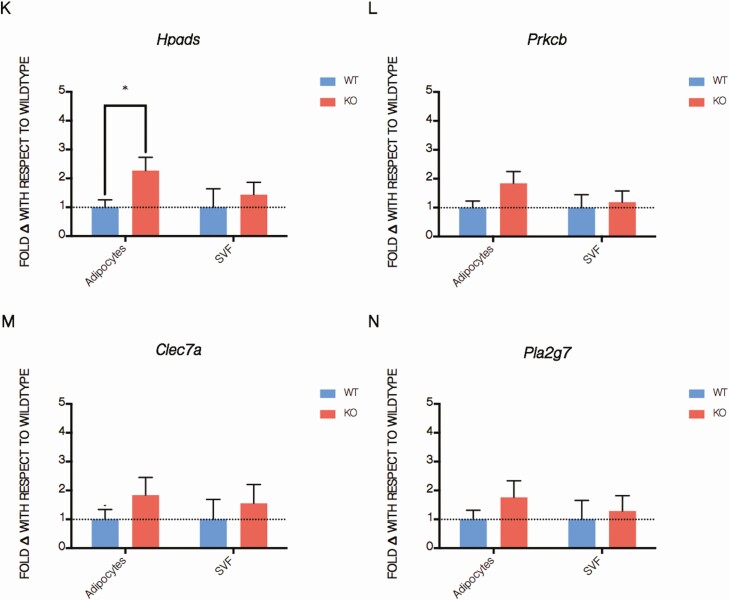

Because our data did not support altered PPARγ transcriptional activity in adSMRT-/- adipocytes, we next wanted to assess large-scale gene expression changes induced by loss of this corepressor to identify possible mechanisms that would explain the knockout phenotype. We therefore performed RNAseq analysis of primary adipose tissue derived from wild-type and adSMRT-/- mice. We found that 67 genes were differentially expressed by at least 50% between our genotypes at a false discovery rate of < 0.05. Of these genes, the vast majority play roles in immune pathways/are involved in pro-inflammatory processes (Fig. 5A-5C). From these 67 genes, 10 were selected for qRT-PCR validation on isolated adipocytes and the associated SVF (Fig. 5D) to both confirm RNAseq findings as well as identify the source of inflammatory signaling (adipocyte, resident immune cell, or both); we found that of these 10 pro-inflammatory genes, 3 were significantly upregulated in adipocytes, with any genes not identified as significantly differentially expressed trending strongly in this direction (Fig. 5E-5N). Together, these data led us to the conclusion that SMRT loss in the adipocyte causes inflammatory dysregulation in adipose tissue, which may in turn inform the microenvironment and resident immune cells to drive local insulin resistance and glucose intolerance.

Figure 5.

RNA sequencing indicates dysregulation of immune pathways in adSMRT-/- mice. A-D: Significantly differentially expressed genes, identified by RNA sequencing of whole adipose tissue samples from mice fed a 45% HFD, plotted as a heatmap and categorized for roles in either immune pathways or other pathways, with category “Other” representing molecular functions spanning histone modifications, homeostasis, cell cycle regulation, and more; red, blue, and yellow colors represent upregulation, downregulation, or no change, respectively, relative to the average expression level for that gene across all eight biological replicates (each column represents a biological replicate) (A); summarizing table identifying differentially expressed genes between wild-type and adSMRT-/- samples at various fold change (FD) and false-discovery rate (FDR) cutoffs (67 differentially expressed genes identified at a FDR of < 0.05 and FD of > 1.5) (B); unbiased GO analysis revealing that the vast majority of pathways identified as differentially regulated between genotypes are those within the functional category of immune processes (C). GO terms that may be classified under multiple functional categories, eg, “leukocyte migration” as either “Immune Response” or “Migration,” were counted as the less frequent category; FDs and FDR-corrected P values of genes selected for qRT-PCR validation (D); N = 4 per genotype. E-N: qRT-PCR validation of RNAseq via genes identified in table C, expressed as fold change with respect to wild-type for both isolated adipocytes and the associate stromal vascular fraction. N = 3 per genotype per sample type (adipocyte vs SVF). Data are means ± SEM; *P < 0.05. Fold changes for targets Slamf9, Prkcb, Clec7a, and Pla2g7 all trended towards significance (P < 0.1).

Increased presence of metabolically activated macrophages in adSMRT-/- adipose tissue

We next assessed adipose tissue macrophage phenotypes in vivo via qRT-PCR, and found that markers for the MMe phenotype Abca1, Plin2, and Tnfa were significantly upregulated in macrophages isolated from adSMRT-/- adipose tissue (Fig. 6A). There was also a trend towards increased Il1b expression, though this did not reach statistical significance. To better understand the influence of the microenvironment on macrophage phenotypes, we conducted flow cytometry on the adipose tissue SVF in our mice. We selected 2 general markers for macrophage identification (CD11b, F4/80) from which we gated for M1 (CD38, CD274) and M2 (CD36, CD206) macrophages (not shown). While CD11b and F4/80 markers were analyzed independently, cells would only be considered macrophages and interrogated for M1/M2 phenotypes if cells expressed both markers. In our adSMRT-/- samples, we found a significant increase in the proportion of F4/80 positive cells, while an increase in cells expressing both CD11b and F4/80 trended towards significance; meanwhile, wild-type expressed significantly more non-macrophage immune cells, indicated by the proportion of CD11b, F4/80 negative cells (Fig. 6C). From these data, we hypothesized that dysregulated adipocyte signaling was altering the dynamics of adipose tissue macrophage infiltration, so we next conducted in vitro conditioned media experiments to determine how the adipocyte secretome may be influencing macrophage phenotypes. Naïve macrophages were cultured in media conditioned from adipose tissue derived from wild-type and adSMRT-/- mice, and qRT-PCR was utilized to assess gene expression patterns of cultured macrophages using markers for the MMe phenotype. We found that adipose-conditioned media from adSMRT-/- mice influenced macrophages to develop a pro-inflammatory MMe phenotype, significantly increasing expression of markers Abca1, Plin2, and Il1b, with a trend towards an increase in Tnfa (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, it has been previously shown that the MMe phenotype is enhanced in the presence of certain adipocyte secreted factors, eg, palmitate (47, 48); these data suggest that the microenvironment of our adSMRT-/- adipose tissue, informed by altered signaling/secretions of the adipocyte, encourage resident macrophages to take on a pro-inflammatory, MMe character. This may explain the localized increase in adipose tissue inflammation, which would potentiate the overall deleterious metabolic outcome.

Figure 6.

In vitro and in vivo data suggest adSMRT-/- adipose tissue microenvironment influences development of and is enriched for metabolically activated macrophages. A: qRT-PCR expression data from macrophages isolated from primary epididymal adipose tissue for the MMe/proinflammatory macrophage phenotype targets Abca1, Plin2, Tnfa, and Il1b. N = 5 per genotype. *P < 0.05. Data are means ± SEM. B-C: flow cytometric data for isolated SVF, with data presented as a percentage of cells from the previous gate (indicated on axes); only cells positive for both macrophage markers CD11b and F4/80 were considered downstream analysis, and any samples that contained <65% live cells were excluded. N = 5-8 per genotype. Data are means ± SEM; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. D: Following incubation in media conditioned from wild-type and adSMRT-/- whole fat, naïve macrophages were analyzed via qRT-PCR for expression of metabolically activated macrophage (MMe) phenotype markers IL1, TNFa, Abca1, and Plin2 to determine whether alterations in the KO adipose tissue secretome influence macrophage differentiation. N = 3 per genotype. Data are means ± SEM; **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005.

Discussion

SMRT is a corepressor for nuclear receptors and other transcription factors; it is structurally related to its homolog NCoR1 (49). However, SMRT and NCoR1 have distinct functions, as homozygous knockout of either is embryonic lethal, demonstrated by Jepsen et al (50). Because of this lethality, 2 approaches have been used to develop models to study the metabolic functions of SMRT and NCoR1 in vivo: a generalized heterozygous knockout, or various mutations of the RIDs (24). In the case of the latter, for NCoR1, Astapova et al found that NCoRΔID mice demonstrated increased thyroid hormone-dependent energy expenditure, a result of increased sensitivity (51). However, Nofsinger et al showed that when Smrt is analogously mutated, this somewhat beneficial outcome is replaced by reduced respiration and energy expenditure (52); SMRTmRID mice also showed an increase in fat mass/adipogenesis, via PPARγ derepression. A similar model also interrogating SMRT (SMRTmRID1), utilized by Reilly et al and Fang et al, yielded a mouse with decreased mitochondrial function and worsened insulin resistance (53, 54), whereas Sutanto et al, utilizing a heterozygous knockout (SMRT+/-) model, reported a mixed metabolic outcome: fat mass expansion/enhanced caloric intake combined with improved adipocyte insulin sensitivity, again likely due to PPARγ derepression (46). Because these findings, together, are somewhat contradictory, later studies have focused on tissue-specific knockout models; Yamamoto et al studied NCoR1 through a muscle-specific knockout model (55), whereas Li et al did the same, but in adipocytes (56). However, no such study existed for SMRT—to this end, we generated an adipocyte-specific SMRT knockout (adSMRT-/-) mouse to rigorously define the role of SMRT in the adipocyte, and how it affects metabolic homeostasis. In fact, our model is phenotypically distinct from previous SMRT models, suggesting that earlier phenotypes were influenced at least in part by nonadipose tissues.

Interestingly, weight, body composition, and adipocyte size all remain unchanged in adSMRT-/- mice, suggesting that altered SMRT function does not influence those characteristics through the adipocyte. Despite this, adSMRT-/- mice still develop a striking metabolic phenotype characterized by increased feeding and RER, decreased glucose tolerance, and worsened adipocyte insulin sensitivity. We next set out to assess whether changes in PPARγ activity could be responsible for the observed effect, but we found that the expression of PPARγ downstream targets were unaltered. Interestingly, insulin-induced lipogenesis appears to be intact, even though there is insulin resistance at the level of the adipocyte itself. Because the canonical paradigm of SMRT impacting metabolism through PPARγ/obesity did not hold for the adSMRT-/- mouse, we took an unbiased approach to define gene transcription changes in adipose tissue by performing an RNAseq analysis. Surprisingly, genes involved in immunity (specifically, pro-inflammatory processes) were dysregulated in the adipose tissue of adSMRT-/- mice. Since we used adipose tissue, containing both adipocytes and resident immune cells, to generate our RNAseq data, we next confirmed our RNAseq results by interrogating the expression levels for a subset of RNAseq-identified genes in both adipocytes and the SVF fraction. While nearly all genes trended in the anticipated pro-inflammatory direction for both sample types, we found that the majority of genes that were significantly differentially expressed originated from adipocytes. We next performed flow cytometry studies, and focused on determining whether metabolically activated macrophages (MMe) could be responsible for driving the phenotype, as the influence of MMe macrophages have recently been shown to lead to detrimental metabolic phenotypes (16), and may more accurately reflect changes in the adipose tissue microenvironment, with free fatty acids (FFAs) also being a primary inducer of the MMe phenotype (16, 17, 47). Through conditioned media experiments, we found that the secretome of our adSMRT-/- mice adipose tissue significantly stimulated MMe macrophage differentiation; qRT-PCR experiments confirmed that naïve macrophages, after being exposed to media conditioned by adSMRT-/- adipose tissue, strongly express MMe markers such as Abca1 and Plin2 (MMe). Coates et al have established that MMe macrophages play important roles in the pro-inflammatory signaling involved in adipocyte insulin resistance and clearance of FFAs from adipocytes (17); thus, increased MMe macrophage infiltration, caused by changes in the adipocytes via decreased Smrt expression likely explains the phenotype in our adSMRT-/- mice. Prior studies have shown that incubating macrophages with media conditioned by adipose tissue from obese mice induces a macrophage phenotypic switch towards a metabolically activated state (16). Our study shows that deficiency of SMRT induces a similar macrophage phenotype and suggests a potential mechanism by which adipocyte regulation of transcription can ultimately alter macrophage function.

Adipocyte-specific knockout of SMRT leads to dramatic effects on metabolic parameters, although this phenotype surprisingly develops independently of both obesity and PPARγ transcriptional activity. These findings are particularly interesting considering the results of prior models, which support an association between SMRT and obesity/PPARγ activity (24, 49, 57); the results of this study indicate that the obesity observed via other models likely result from SMRT deficiency beyond the adipocyte, possibly via alterations in the central nervous system. Furthermore, the discovery of a strong pro-inflammatory environment in the adipose tissue of our adSMRT-/- mice provides a novel function for SMRT as an integrator of signals at the intersection of metabolism and inflammation. Future studies will aim to define the molecular events leading to altered adipocyte secretory function, and what these secreted factors are that lead to MMe macrophage adipose infiltration. One possibility is that SMRT deficiency results in altered lipolytic function/FFA secretion from adipocytes as a result of dysregulated immune signaling—since FFAs, particularly the lipid species palmitate, have been shown to activate MMe macrophages (58). Determination of such a factor, though, is beyond the scope of the current manuscript. However, these data do suggest that SMRT is a key sensor in adipocytes that simultaneously regulate adipose tissue insulin sensitivity and macrophage infiltration.

When comparing the adSMRT-/- mouse to the NCoR1-/- adipocyte-specific knockout model utilized by Li et al (56), the divergence in metabolic phenotypes is stark. While increased food intake was reflected in both models, all other metabolic parameters move in opposite directions. For example, adipocyte-specific NCoR1-/- mice demonstrated increases in both total weight, and subcutaneous/visceral adipose depot mass, whereas these readouts are unaffected in adSMRT-/- mice. Further, Li et al showed improved glucose tolerance and adipocyte insulin sensitivity in their knockouts, while adSMRT-/- mice were worsened for both parameters. Additionally, adipocyte-specific NCoR1-/- mice had less inflamed adipose tissue compared with wild-type; combined with increased PPARγ transcriptional activity, Li et al concluded that loss of NCoR1 in the adipocyte was metabolically protective, via increased expression of PPARγ target genes (56). However, increased inflammation in adSMRT-/- mice, in conjunction with increased MMe macrophage influence and no change in PPARγ target genes, suggests that the mechanism by which SMRT influences metabolism via the adipocyte is entirely different from its analog, NCoR1. In contrasting these models, the idea that NCoR1 and SMRT play distinct roles in the regulation of metabolic processes through the adipocyte is strongly supported. Specifically, SMRT is able to impact metabolism through inflammatory processes by integrating metabolic and immune signaling in a novel way that, to our knowledge, has not been reported with other nuclear corepressors (eg, NCoR1, RIP-140, SUN-CoR, Alien, Hairless) (24, 59).

Taken together, our data suggest that SMRT loss in the adipocyte induces dysregulation of genes involved in inflammatory processes, which in turn alters signaling to the microenvironment in such a way that stimulates resident macrophages in the adipose tissue of our mice to take on a MMe/M1 phenotype. This then promotes the development of a host of deleterious metabolic outcomes, including local insulin resistance and glucose intolerance, ultimately offering a previously unconsidered role for SMRT in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Matthew Brady and Robert Sargis for their invaluable expertise and guidance throughout this project. We would also like to thank the American Diabetes Association (7-13-BS-033) and the National Institutes of Health, NIDDK (R01 DK078125, T32 DK087703, P30DK020595) for supporting this work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AUC

area under the curve

- FFA

free fatty acid

- HFD

high-fat diet

- MMe macrophages

metabolically activated macrophages

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction

- RER

respiratory exchange ratio

- RID

receptor interacting domain

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SMRT

Silencing Mediator of Retinoid and Thyroid Hormone Receptors

- SVF

stromal vascular fraction

- TF

transcription factor

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References

- 1. Kershaw EE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2548-2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coelho M, Oliveira T, Fernandes R. Biochemistry of adipose tissue: an endocrine organ. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9(2):191-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Choe SS, Huh JY, Hwang IJ, Kim JI, Kim JB. Adipose tissue remodeling: its role in energy metabolism and metabolic disorders. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2016;7:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ali Khan A, Hansson J, Weber P, et al. Comparative secretome analyses of primary murine white and brown adipocytes reveal novel adipokines. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2018;17(12):2358-2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rezaee F, Dashty M. Role of adipose tissue in metabolic system disorders: adipose tissue is the initiator of metabolic diseases. J Diabet Metab. 2013;13(8):2155–6156. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ordovas JM, Corella D. Metabolic syndrome pathophysiology: the role of adipose tissue. Kidney Int Suppl. 2008;111:S0-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bremer AA, Devaraj S, Afify A, Jialal I. Adipose tissue dysregulation in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(11):E1782-E1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(2):85-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chatterjee TK, Stoll LL, Denning GM, et al. Proinflammatory phenotype of perivascular adipocytes: influence of high-fat feeding. Circ Res. 2009;104(4):541-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nolan CJ, Ruderman NB, Kahn SE, Pedersen O, Prentki M. Insulin resistance as a physiological defense against metabolic stress: implications for the management of subsets of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(3):673-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Avramoglu RK, Basciano H, Adeli K. Lipid and lipoprotein dysregulation in insulin resistant states. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;368(1-2):1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Delarue J, Magnan C. Free fatty acids and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10(2):142-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ellulu MS, Patimah I, Khaza’ai H, Rahmat A, Abed Y. Obesity and inflammation: the linking mechanism and the complications. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13(4):851-863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Monteiro R, Azevedo I. Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Mediat. Inflamm. 2010. doi: 10.1155/2010/289645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Russo L, Lumeng CN. Properties and functions of adipose tissue macrophages in obesity. Immunology. 2018;155(4):407-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kratz M, Coats BR, Hisert KB, et al. Metabolic dysfunction drives a mechanistically distinct proinflammatory phenotype in adipose tissue macrophages. Cell Metab. 2014;20(4):614-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coats BR, Schoenfelt KQ, Barbosa-Lorenzi VC, et al. Metabolically activated adipose tissue macrophages perform detrimental and beneficial functions during diet-induced obesity. Cell Rep. 2017;20(13):3149-3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Auwerx J. Regulation of PGC-1α, a nodal regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(4):884S-8890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu C, Lin JD. PGC-1 coactivators in the control of energy metabolism. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2011;43(4):248-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feige JN, Auwerx J. Transcriptional coregulators in the control of energy homeostasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(6):292-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mihaylova MM, Shaw RJ. Metabolic reprogramming by class I and II histone deacetylases. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2013;24(1):48-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horwitz KB, Jackson TA, Bain DL, Richer JK, Takimoto GS, Tung L. Nuclear receptor coactivators and corepressors. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10(10):1167-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cohen RN. Nuclear receptor corepressors and PPARgamma. Nucl Recept Signal. 2006;4:e003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mottis A, Mouchiroud L, Auwerx J. Emerging roles of the corepressors NCoR1 and SMRT in homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2013;27(8):819-835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rangwala SM, Lazar MA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in diabetes and metabolism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25(6):331-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miles PD, Barak Y, He W, Evans RM, Olefsky JM. Improved insulin-sensitivity in mice heterozygous for PPAR-gamma deficiency. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(3):287-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Raghav SK, Waszak SM, Krier I, et al. Integrative genomics identifies the corepressor SMRT as a gatekeeper of adipogenesis through the transcription factors C/EBPβ and KAISO. Mol Cell. 2012;46(3):335-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shimizu H, Astapova I, Ye F, Bilban M, Cohen RN, Hollenberg AN. NCoR1 and SMRT play unique roles in thyroid hormone action in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35(3):555-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. RRID: AB_1147620, https://antibodyregistry.org/search.php?q=AB_1147620.

- 30. RRID: AB_11213812, https://antibodyregistry.org/search.php?q=AB_11213812.

- 31. RRID: AB_2315049, https://antibodyregistry.org/search.php?q=AB_2315049.

- 32. Andrews, S. FastQC A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. 2012. http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- 33. Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(1):15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Trapnell C, Williams B, Pertea G, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(7):923–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40(10):4288–4297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterprofiler: an r package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology. 2012;16(5):284–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. SMRT regulates metabolic homeostasis and adipose tissue macrophage phenotypes in tandem. Gene Expression Omnibus. July 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE129369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. RRID: AB_396679, https://antibodyregistry.org/search.php?q=AB_396679.

- 41. RRID: AB_893489, https://antibodyregistry.org/search.php?q=AB_893489.

- 42. RRID: AB_2737782, https://antibodyregistry.org/search.php?q=AB_2737782.

- 43. RRID: AB_10639934, https://antibodyregistry.org/search.php?q=AB_10639934.

- 44. RRID: AB_2737732, https://antibodyregistry.org/search.php?q=AB_2737732.

- 45. RRID: AB_2739133, https://antibodyregistry.org/search.php?q=AB_2739133.

- 46. Sutanto MM, Ferguson KK, Sakuma H, Ye H, Brady MJ, Cohen RN. The silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors (SMRT) regulates adipose tissue accumulation and adipocyte insulin sensitivity in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(24):18485-18495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hubler MJ, Kennedy AJ. Role of lipids in the metabolism and activation of immune cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;34:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tiwari P, Blank A, Cui C, et al. Metabolically activated macrophages in mammary adipose tissue link obesity to triple-negative breast cancer. bioRxiv. 2018. doi: 10.1101/370627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cohen RN, Putney A, Wondisford FE, Hollenberg AN. The nuclear corepressors recognize distinct nuclear receptor complexes. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14(6):900-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jepsen K, Hermanson O, Onami TM, et al. Combinatorial roles of the nuclear receptor corepressor in transcription and development. Cell. 2000;102(6):753-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Astapova I, Lee LJ, Morales C, Tauber S, Bilban M, Hollenberg AN. The nuclear corepressor, NCoR, regulates thyroid hormone action in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(49):19544-19549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nofsinger RR, Li P, Hong SH, et al. SMRT repression of nuclear receptors controls the adipogenic set point and metabolic homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(50):20021-20026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reilly SM, Bhargava P, Liu S, et al. Nuclear receptor corepressor SMRT regulates mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and mediates aging-related metabolic deterioration. Cell Metab. 2010;12(6):643-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fang S, Suh JM, Atkins AR, et al. Corepressor SMRT promotes oxidative phosphorylation in adipose tissue and protects against diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(8):3412-3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yamamoto H, Williams EG, Mouchiroud L, et al. NCoR1 is a conserved physiological modulator of muscle mass and oxidative function. Cell. 2011;147(4):827-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li P, Fan W, Xu J, et al. Adipocyte NCoR knockout decreases PPARγ phosphorylation and enhances PPARγ activity and insulin sensitivity. Cell. 2011;147(4):815-826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yu C, Markan K, Temple KA, Deplewski D, Brady MJ, Cohen RN. The nuclear receptor corepressors NCoR and SMRT decrease peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma transcriptional activity and repress 3T3-L1 adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(14):13600-13605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bhargava P, Lee CH. Role and function of macrophages in the metabolic syndrome. Biochem J. 2012;442(2):253-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Privalsky ML. The role of corepressors in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:315-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]