Abstract

BACKGROUND

Transendoscopic enteral tubing (TET) has been used in China as a novel delivery route for fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) into the whole colon with a high degree of patient satisfaction among adults.

AIM

To explore the recognition and attitudes of FMT through TET in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

METHODS

An anonymous questionnaire, evaluating their awareness and attitudes toward FMT and TET was distributed among IBD patients in two provinces of Eastern and Southwestern China. Question formats included single-choice questions, multiple-choice questions and sorting questions. Patients who had not undergone FMT were mainly investigated for their cognition and acceptance of FMT and TET. Patients who had experience of FMT, the way they underwent FMT and acceptance of TET were the main interest. Then all the patients were asked whether they would recommend FMT and TET. This study also analyzed the preference of FMT delivery in IBD patients and the patient-related factors associated with it.

RESULTS

A total of 620 eligible questionnaires were included in the analysis. The survey showed that 44.6% (228/511) of patients did not know that FMT is a therapeutic option in IBD, and 80.6% (412/511) of them did not know the concept of TET. More than half (63.2%, 323/511) of the participants stated that they would agree to undergo FMT through TET. Of the patients who underwent FMT via TET [62.4% (68/109)], the majority [95.6% (65/68)] of them were satisfied with TET. Patients who had undergone FMT and TET were more likely to recommend FMT than patients who had not (94.5% vs 86.3%, P = 0.018 and 98.5% vs 87.8%, P = 0.017). Patients’ choice for the delivery way of FMT would be affected by the type of disease and whether the patient had the experience of FMT. When compared to patients without experience of FMT, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patients who had experience of FMT preferred mid-gut TET (P < 0.001) and colonic TET (P < 0.001), respectively.

CONCLUSION

Patients’ experience of FMT through TET lead them to maintain a positive attitude towards FMT. The present findings highlighted the significance of patient education on FMT and TET.

Keywords: Recognition, Fecal microbiota transplant, Washed microbiota transplantation, Transendoscopic enteral tubing, Attitude

Core tip: Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has shown its therapeutic potential in inflammatory bowel disease. Transendoscopic enteral tubing (TET) has been used in China as a novel delivery route for FMT. Perception and attitude towards FMT and TET by physicians and patients play an important role in determining its acceptability. We investigated Chinese inflammatory bowel disease patients’ attitude towards FMT and TET and also examined their preference of FMT delivery. This is the first large-scale study of inflammatory bowel disease patients’ perceptions and attitude towards FMT and TET.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) continues to increase steadily in Western countries and has a rapidly increasing incidence in China[1,2]. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has shown its therapeutic potential in IBD[3-6]. The rate of clinical response in randomized controlled trials involving FMT in ulcerative colitis (UC) ranged between 39% and 55%[6-9]. Since the first case of severe Crohn’s disease (CD) treated with FMT through the mid-gut[10], another large study has shown that multiple fresh FMTs were effective to induce and maintain clinical remission in CD with intraabdominal inflammatory mass[4]. The concept of FMT was traced back in China to at least 1700 years ago[11] in which the gut microbiota was transferred from healthy people to the patients to treat dysbiosis related diseases[12], such as metabolic syndrome[13], gut-brain axis-related diseases[14] and even hypertension[15]. However, the efficacy and safety reports by different research centers varied due to many reasons including the methodology of preparation of fecal microbiota and the delivery way of FMT[3,6,16]. These controversial reports might be the evidence for questioning the scientific basis of gut microbiome studies and criticizing that many of them are farfetched[17]. Therefore, the useful delivery of microbiota to gut is the core issue to result in the real efficacy of FMT.

Ding et al[3] reported that a lower rate of FMT-related adverse events was found in patients with colonic transendoscopic enteral tubing (TET) as the delivery method. TET is the latest progression on FMT delivery way, including the mid-gut/naso-jejunal TET and colonic TET[18,19]. The tiny colonic TET tube is fixed onto the wall by clips after it is inserted into the cecum through the endoscopic channel. It has been a safe and convenient procedure for multiple FMTs and colonic medication administration with a high degree of satisfaction among adult patients[3,18].

A new clinical therapeutic application depends not only on its efficacy but also on the recognition and attitudes of physicians and patients. Ren et al[20] reported that Chinese physicians have a high awareness and acceptance of FMT, and one of the physicians’ greatest concerns was patient acceptability. Previous studies in our center have shown that the clinical efficacy of FMT maintains a positive attitude among CD patients[21]. However, there has been no large-scale survey that focuses on the recognition and attitude of IBD patients toward FMT and TET. This survey aimed to demonstrate the current attitudes of Chinese IBD patients toward FMT through TET and further provide recommendations for physicians in China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, setting and participants

A questionnaire survey among the IBD patients were conducted in three centers, including the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, the Affiliated Huaian No. 1 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University and the First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University. Questionnaires were distributed by electronic form to 652 patients from April 2019 to November 2019. They completed the questionnaires voluntarily under anonymous and uncompensated conditions. In this article, we use “patients” and “participants” interchangeably to refer to the respondents. This study was approved by the institutional ethical review board.

Questionnaire design

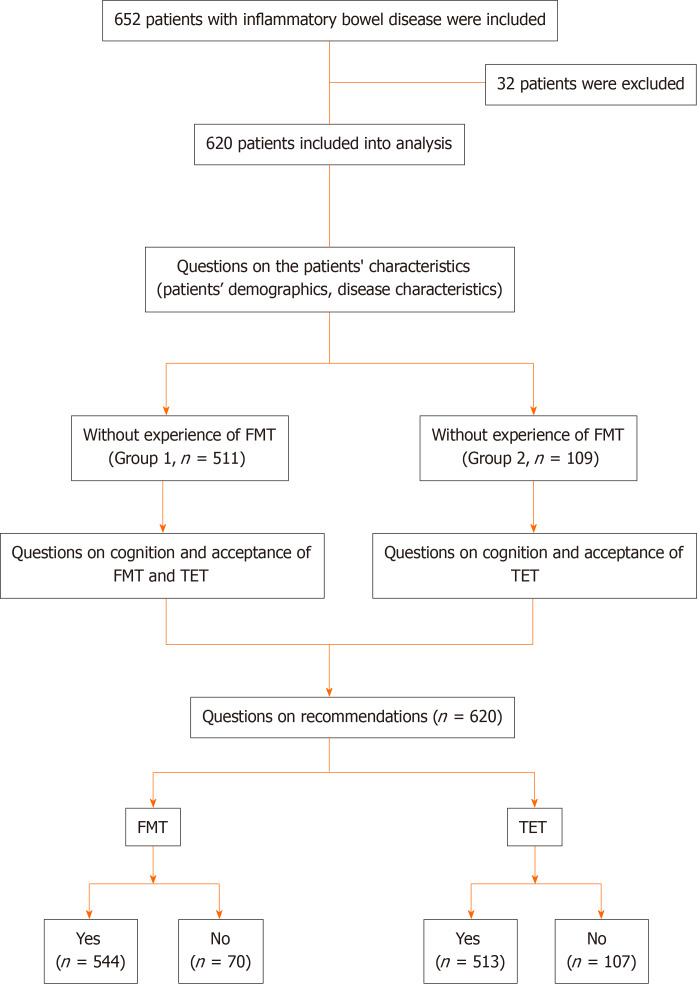

An anonymous questionnaire was developed according to our experiences in performing FMT and TET (partially detailed in Supplementary Table 1). Question format included single choice, multiple choice and sorting questions. After the questions on patients’ demographics (age, gender, etc), and disease characteristics (disease category, self-reported disease severity, etc), patients were asked about the experience of FMT. In particular, the participants were divided into two groups: (1) Group 1: Patients without experience of FMT; and (2) Group 2: Patients with experience of FMT. The flow chart of the questionnaire is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study. FMT: Fecal microbiota transplantation; TET: Transendoscopic enteral tubing.

Statistical analysis

Data collection and its statistical analysis were carried out using the SPSS software system (SPSS for Windows, Version 23.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The general knowledge and attitude towards the FMT and TET were compared with the use of multivariate analysis, Pearson Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Qualitative variables were expressed as percentages, whereas quantitative variables were expressed as a median. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics

In total, 652 surveys were returned and 620 were qualified for analysis (32 questionnaires with missing items) yielding an effective rate of 95.1%. Patients’ ranged in age from 14 years to 76 years (median: 35 years), and 30 patients were below 18-years-old at the time of the study (completed under parents’ guidance). Among them, 109 (17.6%) patients had undergone FMT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants

| Items |

Result |

|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |

| Total number | 511 | 109 |

| Age, median (range), yr | 45.0 (35.5-51.0) | 35.0 (29.0-42.0) |

| Age at diagnosis, median (range), yr | 28.5 (21.0-38.0) | 26.0 (29.0-33.0) |

| Duration of disease, median (range), yr | 3.0 (1.5-7.5) | 8.0 (5.0-12.0) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 326 (63.8) | 68 (62.4) |

| Disease category, n (%) | ||

| UC | 260 (50.9) | 40 (36.7) |

| CD | 211 (41.3) | 62 (56.9) |

| IBD unclassified | 40 (7.8) | 7 (6.4) |

| Level of education, n (%) | ||

| At or below primary school | 51 (10.0) | 6 (5.5) |

| Middle school or equivalent | 188 (36.8) | 35 (32.1) |

| At or above undergraduate | 272 (52.2) | 68 (62.4) |

| Medicine education background, n (%) | ||

| With | 48 (9.4) | 6 (5.5) |

| Without | 463 (90.6) | 103 (94.5) |

| Family history of IBD, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 38 (7.4) | 9 (8.3) |

| No | 473 (92.6) | 100 (91.7) |

| Self-reported disease severity, n (%) | ||

| Mild | 194 (38.0) | 36 (33.0) |

| Moderate | 248 (48.5) | 49 (45.0) |

| Severe | 69 (13.5) | 24 (22.0) |

CD: Crohn’s disease; FMT: Fecal microbiota transplantation; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; UC: Ulcerative colitis.

Questions on fecal microbiota transplant

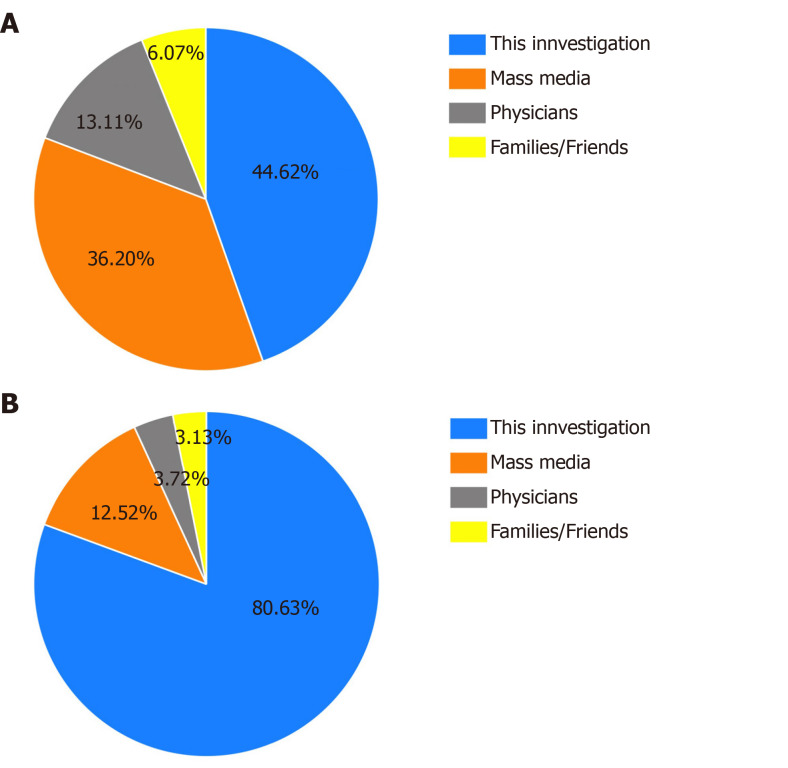

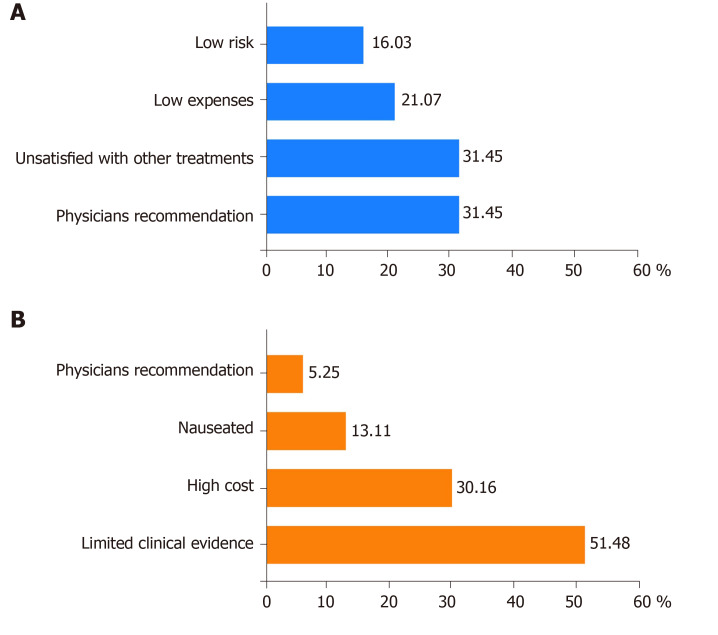

Nearly half of participants (44.6%, 228/511) with no experience of FMT were unaware of FMT. Of them, CD patients (144/211) showed significantly higher awareness of FMT when compared to UC patients (115/260) (P = 0.012, odds ratio (OR) = 0.369, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.25-0.54). Figure 2A showed the different approaches for patients to learn about FMT. Mass media (36.2%) and physician’s recommendation (21.1%) were the most common sources of information. In all, 61.5% of patients (314/511) supported FMT based on their current state of knowledge, whereas 35.6% (182/511) were not sure about it. The main reasons for patients supporting FMT or not were displayed in Figure 3A and 3B. UC patients showed a higher percentage of willingness to undergo FMT than CD patients (51.9% vs 39.2%, P = 0.03). No other significant difference was found based on gender, disease category, level of education, medical professional, family history of IBD or disease severity.

Figure 2.

Approaches to learn about fecal microbiota transplantation and transendoscopic enteral tubing for the first time. A, B: All respondents’ approaches to primarily knowing about fecal microbiota transplantation (A) and transendoscopic enteral tubing (B) in patients without experience of fecal microbiota transplantation.

Figure 3.

Reasons for supporting fecal microbiota transplantation (A) and not supporting fecal microbiota transplantation (B).

In the present study, 86.3% (441/511) of the patients agreed to recommend FMT as a treatment for IBD to others. Whereas, the relevant analysis showed that patients in Group 2 were more likely to recommend FMT than those in Group 1 (94.5% vs 86.3%, P = 0.018). Multivariate analysis showed that no significant difference was observed in gender (male vs female), disease category (CD vs UC) and disease severity (mild vs severe) parameters. In addition, patients who had undergone TET showed a more positive attitude toward FMT than patients who never underwent TET (98.5% vs 87.8%, P = 0.017).

Questions on the delivery of fecal microbiota transplantation

Up to 80.6% (412/511) of the patients in Group 1 were unaware of TET prior to this survey. The first approach for them to learn about TET is shown in Figure 2B. More than half (63.2%, 323/511) of the participants stated that they would agree to undergo FMT through TET. When comparing male vs female (OR = 0.769, 95%CI: 0.512-1.157, P = 0.208), CD vs UC (OR = 1.378, 95%CI: 0.926-2.051, P = 0.114), patients with mild vs severe disease (OR = 0.959, 95%CI: 0.720-1.278, P = 0.775), the differences were not significant.

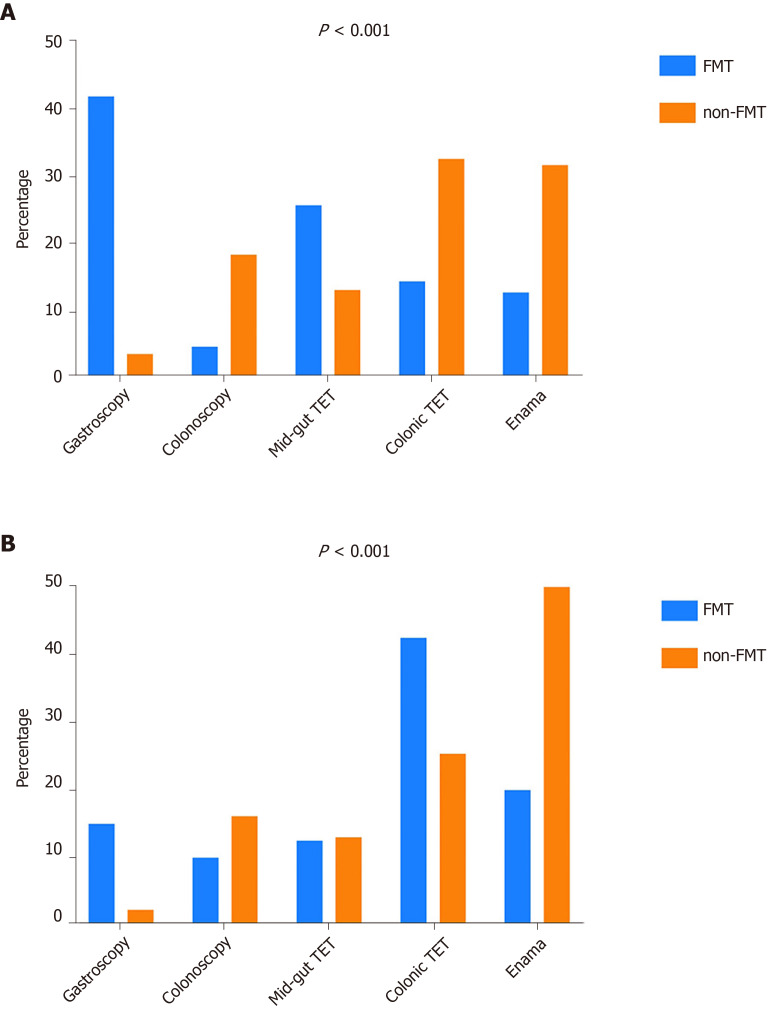

Among the five options offered: Gastroscopy, colonoscopy, mid-gut TET, colonic TET and enema, the patients were further asked which transplant route they preferred. In patients of Group 1, 216/511(42.3%) of the participants preferred enema, while 31.2% of the participants were more likely to choose gastroscopy in Group 2, with a significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.001). If we focus on the choice of TET, CD patients in Group 2 were more likely to choose mid-gut TET than patients in Group 1 (29.0% vs 13.3%, P < 0.001) (Figure 4A). Meanwhile, for UC patients, Group 2 had a larger proportion of patients who preferred colonic TET than Group 1 (42.5% vs 25.4%, P < 0.001) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Optimal methods of undergoing fecal microbiota transplantation. A: The preferred delivery of Crohn’s disease patients with and without experience of fecal microbiota transplantation; B: The preferred delivery way of ulcerative colitis patients with and without experience of fecal microbiota transplantation. FMT: Fecal microbiota transplantation; TET: Transendoscopic enteral tubing.

In terms of the willingness to recommend TET, 82.7% (513/620) of patients were willing to recommend it, and there was a significant difference in type of disease (P = 0.022) and gender (P = 0.047). A multivariate analysis showed that the type of disease (OR = 0.614, 95%CI: 0.423-0.891, P = 0.01) was an independent factor influencing the recommendations. UC patients were more likely to recommend TET than CD patients (50.7% vs 41.5%, P =0.01).

DISCUSSION

This study delineated that nearly half of IBD patients were unaware that FMT is a therapeutic option, and a large proportion of patients did not know the concept of TET prior to this survey. Overall, the results indicated a poor recognition of FMT and TET amongst IBD patients in China. This finding was in line with the survey conducted in Switzerland and the United States that revealed the poor recognition of FMT in IBD patients[22,23]. The reasons that IBD patients have a low awareness of FMT and TET need to be explored. FMT is a relatively new technique and has only been written into the guidelines for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection since 2013[24]. TET is also a new interventional method, which was first published in 2016[18] and only used in some hospitals in China mainland[25,26,27] and China Taiwan[28] up to 2019.

The results suggest that mass media and physician’s recommendation are the most common approaches for patients to learn about FMT and TET. Although mass media is a powerful way to disseminate knowledge, the coverage of this emerging therapy is limited with varying degrees of depth and attention. It is hard to make sure patients do not receive misleading information from mass media. This may explain why the cognition of FMT among IBD patients has not improved significantly in recent years[22,23]. Chinese clinicians who have a negative attitude toward media that exaggerate and mystify the effects of FMT as “magic” and “miraculous” fear that this may mislead patients[29]. Another survey showed that the physician’s perceptions of FMT can indirectly affect patient’s acceptance[23]. The approach of physician’s recommendation will be more effective in improving patient’s cognition on FMT and TET than mass media in the future.

In previous studies, the stigma or “yuck” factor associated with FMT and the lack of evidence on the safety and efficacy of FMT have affected patients’ interest in this therapy[22,23]. However, many studies have demonstrated that FMT is a safe and promising therapy for IBD[3,4,7]. Since 2014, the methodology of FMT preparation in our group was different from the traditional manual FMT. The new methodology of FMT was recently coined as washed microbiota transplantation (WMT), which is dependent on the automatic facilities and washing process in a laboratory room with biosafety level 3[30]. It was demonstrated that WMT is better than the manual preparation of FMT in improving safety, enriching the precise amount of microbiota and improving quality control in practice[30,31]. WMT has been used in China in most of the microbiota therapy centers and the methodology was released by the consensus statement from the FMT-standardization Study Group in 2019[31]. In addition, patients may refuse to undergo FMT repeatedly in a short time because of repeated endoscopic procedures and bowel preparation, but the effectiveness from a single FMT might be limited in severe and refractory microbiota-related conditions. TET can solve the limitations of repeating FMT in a short time, avoiding intestinal injury and bleeding caused by repeated insertion of the enema tube or colonoscopy. Patients in the present study showed a great interest in TET.

The present study demonstrated that patient’s attitude towards FMT would be influenced by the FMT and TET experience of a patient. The patients who had experience of FMT and TET exhibited more positive attitudes toward FMT and were more likely to recommend FMT. Undergoing FMT through TET may improve the understanding of FMT and eliminate patients’ concerns about the aesthetics of FMT. Patients’ choice for the delivery of FMT was influenced by the type of disease and whether the patient had undergone FMT. Patients with experience of FMT were more willing to choose TET as the preferred route. UC patients preferred colonic TET and CD patients preferred mid-gut TET. The reason for this difference could be, other than FMT administration, that the TET tube could be useful in giving enteral nutrition for CD patients through mid-gut TET, while UC patients benefited by whole-colon medication administrations via colonic TET.

There is no single best universal delivery that matches all patients, but the efficacy and safety should be the most important considerations when choosing the delivery method. For example, capsulized microbiota is convenient for adults and Clostridium difficile infection but not for children and IBD, especially for children diagnosed with autism. When considering the delivery route of FMT, disease condition, aesthetic factors, psychology and privacy should be considered carefully during the entire workflow. The researchers and practitioners must pay attention to when the improper delivery caused the negative results, which could increase the medical cost, social cost related to the disease treatment and misleading from patients and medical research.

The long-standing goals of our team are to promote the development of FMT and FMT-related technologies. It can provide recommendations for us to move standardized FMT by understanding patients’ perspectives of FMT and TET, thus bringing benefits to more patients. There are several limitations in this study. The participants we surveyed were from Jiangsu and Yunnan province, which might not be representative of all populations. A larger sample is necessary for future research. The current findings might be unsuitable to draw conclusions on the patients’ attitude to WMT.

In conclusion, this study showed the significance of education to patients due to low awareness or knowledge of FMT. TET as a novel delivery route of FMT needs increasing attention. If the awareness about FMT and TET is increased, then more positive attitudes will be exhibited toward FMT. Therefore, it is important to determine the knowledge, attitude and preferences of patients for FMT though TET. This study indicates that better education for patients should promote the development of FMT.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has shown its therapeutic potential in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Transendoscopic enteral tubing (TET) has been used in China as a safe and convenient procedure for multiple FMTs and colonic medication administration with a high degree of satisfaction among adult patients.

Research motivation

A new clinical therapeutic application depends not only on its efficacy but also on the recognition and attitudes of physicians and patients.

Research objectives

The main objectives of this study were to explore the recognition and attitudes of FMT through TET in patients with IBD and the preference of FMT delivery.

Research methods

An anonymous questionnaire was distributed among IBD patients in two provinces of Eastern and Southwestern China. The participants were divided into two groups: (1) Group 1: Patients without experience of FMT; and (2) Group 2: Patients with experience of FMT. We also evaluated their awareness and attitudes toward FMT and TET and their preference of FMT delivery.

Research results

Nearly half of the IBD patients were unaware that FMT was a therapeutic option, and a large proportion of patients did not know the concept of TET prior to this survey. Mass media and physician’s recommendation were the most common sources of information. Patients’ choice for the delivery of FMT was affected by the type of disease and whether the patient had experience with FMT. Crohn’s disease patients in Group 2 were more likely to choose mid-gut TET than patients in Group 1. Meanwhile, for ulcerative colitis patients, Group 2 had a larger proportion of patients who preferred colonic TET than Group 1. The relevant analysis showed that patients in Group 2 were more likely to recommend FMT than those in Group 1. The type of disease was an independent factor influencing the recommendations of TET. Ulcerative colitis patients were more likely to recommend TET than Crohn’s disease patients.

Research conclusions

IBD patients have a low awareness of FMT and TET in China. If awareness about FMT and TET increases, then a more positive attitude will be exhibited toward FMT, thus showing the significance of education to patients.

Research perspectives

Further studies need to clarify the patients’ attitude to the washed microbiota transplantation, which has been regarded as the new technology of FMT.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the participants for who voluntarily participated in the survey for their time and efforts. The authors also thank Ms. Heena Buch for her careful language assistance.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University.

Informed consent statement: The study was a survey of patients’ perceptions using questionnaires. Patients were asked if they would like to complete the questionnaire before starting to fill it out. They would only complete the questionnaire if they wanted to. There was no risk to the participants, and no individual patient information was revealed under the condition of anonymity.

Conflict-of-interest statement: Zhang FM invented the concept of transendoscopic enteral tubing and related devices. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement checklist of items and the manuscript was prepared and revised accordingly.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: March 26, 2020

First decision: April 26, 2020

Article in press: July 30, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Santivañez J, Serban ED S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Min Zhong, Medical Center for Digestive Diseases, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210011, Jiangsu Province, China; Key Lab of Holistic Integrative Enterology, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210011, Jiangsu Province, China.

Yang Sun, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Yunnan Institute of Digestive Disease, Kunming 650032, Yunnan, China.

Hong-Gang Wang, Medical Center for Digestive Diseases, The Affiliated Huaian No. 1 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Huaian 223300, Jiangsu Province, China.

Cicilia Marcella, Medical Center for Digestive Diseases, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210011, Jiangsu Province, China; Key Lab of Holistic Integrative Enterology, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210011, Jiangsu Province, China.

Bo-Ta Cui, Medical Center for Digestive Diseases, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210011, Jiangsu Province, China; Key Lab of Holistic Integrative Enterology, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210011, Jiangsu Province, China.

Ying-Lei Miao, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Yunnan Institute of Digestive Disease, Kunming 650032, Yunnan, China.

Fa-Ming Zhang, Medical Center for Digestive Diseases, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210011, Jiangsu Province, China; Key Lab of Holistic Integrative Enterology, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210011, Jiangsu Province, China. fzhang@njmu.edu.cn.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and Preventing the Global Increase of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:313–321.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng SC, Bernstein CN, Vatn MH, Lakatos PL, Loftus EV, Jr, Tysk C, O'Morain C, Moum B, Colombel JF Epidemiology and Natural History Task Force of the International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IOIBD) Geographical variability and environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62:630–649. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding X, Li Q, Li P, Zhang T, Cui B, Ji G, Lu X, Zhang F. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Fecal Microbiota Transplant in Active Ulcerative Colitis. Drug Saf. 2019;42:869–880. doi: 10.1007/s40264-019-00809-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He Z, Li P, Zhu J, Cui B, Xu L, Xiang J, Zhang T, Long C, Huang G, Ji G, Nie Y, Wu K, Fan D, Zhang F. Multiple fresh fecal microbiota transplants induces and maintains clinical remission in Crohn's disease complicated with inflammatory mass. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4753. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04984-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui B, Feng Q, Wang H, Wang M, Peng Z, Li P, Huang G, Liu Z, Wu P, Fan Z, Ji G, Wang X, Wu K, Fan D, Zhang F. Fecal microbiota transplantation through mid-gut for refractory Crohn's disease: safety, feasibility, and efficacy trial results. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:51–58. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cold F, Browne PD, Günther S, Halkjaer SI, Petersen AM, Al-Gibouri Z, Hansen LH, Christensen AH. Multidonor FMT capsules improve symptoms and decrease fecal calprotectin in ulcerative colitis patients while treated - an open-label pilot study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:289–296. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2019.1585939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moayyedi P, Surette MG, Kim PT, Libertucci J, Wolfe M, Onischi C, Armstrong D, Marshall JK, Kassam Z, Reinisch W, Lee CH. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Induces Remission in Patients With Active Ulcerative Colitis in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:102–109.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossen NG, Fuentes S, van der Spek MJ, Tijssen JG, Hartman JH, Duflou A, Löwenberg M, van den Brink GR, Mathus-Vliegen EM, de Vos WM, Zoetendal EG, D'Haens GR, Ponsioen CY. Findings From a Randomized Controlled Trial of Fecal Transplantation for Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:110–118.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costello SP, Hughes PA, Waters O, Bryant RV, Vincent AD, Blatchford P, Katsikeros R, Makanyanga J, Campaniello MA, Mavrangelos C, Rosewarne CP, Bickley C, Peters C, Schoeman MN, Conlon MA, Roberts-Thomson IC, Andrews JM. Effect of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation on 8-Week Remission in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321:156–164. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.20046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang FM, Wang HG, Wang M, Cui BT, Fan ZN, Ji GZ. Fecal microbiota transplantation for severe enterocolonic fistulizing Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7213–7216. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i41.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang F, Luo W, Shi Y, Fan Z, Ji G. Should we standardize the 1,700-year-old fecal microbiota transplantation? Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1755; author reply p.1755–1755; author reply p.1756. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui B, Li P, Xu L, Peng Z, Xiang J, He Z, Zhang T, Ji G, Nie Y, Wu K, Fan D, Zhang F. Step-up fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) strategy. Gut Microbes. 2016;7:323–328. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1151608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang PX, Deng XR, Zhang CH, Yuan HJ. Gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133:808–816. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun LJ, Li JN, Nie YZ. Gut hormones in microbiota-gut-brain cross-talk. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133:826–833. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Zhang FM, Hu WZ. Hypertension: microbiota-targeting treatment. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133:1353–1354. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, Walsh AJ, van den Bogaerde J, Samuel D, Leong RWL, Connor S, Ng W, Paramsothy R, Xuan W, Lin E, Mitchell HM, Borody TJ. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1218–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li D, Gao C, Zhang F, Yang R, Lan C, Ma Y, Wang J. Seven facts and five initiatives for gut microbiome research. Protein Cell. 2020;11:391–400. doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00697-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng Z, Xiang J, He Z, Zhang T, Xu L, Cui B, Li P, Huang G, Ji G, Nie Y, Wu K, Fan D, Zhang F. Colonic transendoscopic enteral tubing: A novel way of transplanting fecal microbiota. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E610–E613. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-105205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long C, Yu Y, Cui B, Jagessar SAR, Zhang J, Ji G, Huang G, Zhang F. A novel quick transendoscopic enteral tubing in mid-gut: technique and training with video. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:37. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0766-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ren RR, Sun G, Yang YS, Peng LH, Wang SF, Shi XH, Zhao JQ, Ban YL, Pan F, Wang XH, Lu W, Ren JL, Song Y, Wang JB, Lu QM, Bai WY, Wu XP, Wang ZK, Zhang XM, Chen Y. Chinese physicians' perceptions of fecal microbiota transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4757–4765. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i19.4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu L, Zhang T, Cui B, He Z, Xiang J, Long C, Peng Z, Li P, Huang G, Ji G, Zhang F. Clinical efficacy maintains patients' positive attitudes toward fecal microbiota transplantation. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4055. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahn SA, Vachon A, Rodriquez D, Goeppinger SR, Surma B, Marks J, Rubin DT. Patient perceptions of fecal microbiota transplantation for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1506–1513. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318281f520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeitz J, Bissig M, Barthel C, Biedermann L, Scharl S, Pohl D, Frei P, Vavricka SR, Fried M, Rogler G, Scharl M. Patients' views on fecal microbiota transplantation: an acceptable therapeutic option in inflammatory bowel disease? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:322–330. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, Ananthakrishnan AN, Curry SR, Gilligan PH, McFarland LV, Mellow M, Zuckerbraun BS. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478–98; quiz 499. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding X, Li Q, Li P, Chen X, Xiang L, Bi L, Zhu J, Huang X, Cui B, Zhang F. Fecal microbiota transplantation: A promising treatment for radiation enteritis? Radiother Oncol. 2020;143:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie WR, Yang XY, Xia HH, Wu LH, He XX. Hair regrowth following fecal microbiota transplantation in an elderly patient with alopecia areata: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:3074–3081. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang HL, Chen HT, Luo QL, Xu HM, He J, Li YQ, Zhou YL, Yao F, Nie YQ, Zhou YJ. Relief of irritable bowel syndrome by fecal microbiota transplantation is associated with changes in diversity and composition of the gut microbiota. J Dig Dis. 2019;20:401–408. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang JW, Wang YK, Zhang F, Su YC, Wang JY, Wu DC, Hsu WH. Initial experience of fecal microbiota transplantation in gastrointestinal disease: A case series. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2019;35:566–571. doi: 10.1002/kjm2.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma Y, Yang J, Cui B, Xu H, Xiao C, Zhang F. How Chinese clinicians face ethical and social challenges in fecal microbiota transplantation: a questionnaire study. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18:39. doi: 10.1186/s12910-017-0200-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang T, Lu G, Zhao Z, Liu Y, Shen Q, Li P, Chen Y, Yin H, Wang H, Marcella C, Cui B, Cheng L, Ji G, Zhang F. Washed microbiota transplantation vs. manual fecal microbiota transplantation: clinical findings, animal studies and in vitro screening. Protein Cell. 2020;11:251–266. doi: 10.1007/s13238-019-00684-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fecal Microbiota Transplantation-standardization Study Group. Nanjing consensus on methodology of washed microbiota transplantation. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020 doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.