Abstract

This study used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to measure positive and negative affect among people who inject drugs (PWID), and examined associations with borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptoms and difficulties with emotion regulation, in the context of injection drug use. We recruited PWID, age 18–35, through syringe exchange program sites in Chicago, Illinois, USA. After completing a baseline interview including a screener for BPD and the Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), participants used a mobile phone app to report mood, substance use, and injection behavior for two weeks. Participants who completed at least two EMA assessments were included in the analysis (N = 161). The mean age was 30, about one-third were women, 63% were non-Hispanic white, and 23% were Hispanic. In multivariable mixed effects regression models, positive BPD screen was associated with greater momentary negative affect (NA) intensity, and greater instability of both NA and positive affect (PA). Independent of BPD screening status, DERS score was associated positively with momentary NA intensity and instability, and negatively with positive affect (PA) intensity. This finding suggests that emotion dysregulation is an appropriate target for assessment and intervention. While concurrent withdrawal was associated with both greater NA and less PA, opioid intoxication was associated only with greater PA. We did not find support for our hypothesis that emotion dysregulation would moderate the effect of withdrawal on NA. Findings support the validity of the EMA mood measure and the utility of studying mood and behavior among PWID using EMA on mobile phones.

Keywords: ecological momentary assessment, injection drug use, positive and negative affect, emotion dysregulation, anhedonia

It is widely recognized that substance use and mental health disorders often co-occur (Carpenter, Wood, & Trull, 2016; Compton, Thomas, Stinson, & Grant, 2007; Conway, Compton, Stinson, & Grant, 2006; Grant, Hasin, et al., 2004; Grant, Stinson, et al., 2004; Hall, Degenhardt, & Teesson, 2009; Mackesy-Amiti, Donenberg, & Ouellet, 2012; Myrick & Brady, 2003; Rodriguez-Llera et al., 2006; Torrens, Gilchrist, & Domingo-Salvany, 2011), and that comorbidity complicates treatment for both problems (Grella, 2003; Grella, Stein, Weisner, Chi, & Moos, 2010; Havassy, Alvidrez, & Mericle, 2009; Schäfer & Najavits, 2007). In particular, borderline personality disorder (BPD) is common among people who use drugs (Chen et al., 2011; Mackesy-Amiti et al., 2012; Mills, Teesson, Darke, Ross, & Lynskey, 2004; Rounsaville et al., 1998; Torrens et al., 2011; Trull, Sher, Minks-Brown, Durbin, & Burr, 2000; Verheul, 2001), but is often unrecognized or misdiagnosed (Comtois & Carmel, 2016; Paris & Black, 2015; Zimmerman, 1999, 2017). People who inject drugs (PWID) with BPD are often regarded as difficult to treat by both substance abuse treatment and mental health treatment providers. A better understanding of how BPD affects the lives of PWID can help to inform treatment strategies and harm reduction interventions.

Emotion dysregulation and affective instability are central features of BPD (Zimmerman, 2017), and may drive substance use, accounting in part for the overlap. It is important to distinguish between emotionality and emotion dysregulation (Tull & Aldao, 2015); intense emotions may result from emotion dysregulation, and may be more difficult to control, but intense emotion in itself is not necessarily an indication of an emotion regulation deficit. Individuals with BPD experience rapid mood swings, heightened emotional reactivity, vulnerability to negative affect, and slow recovery from dysphoric states (Crowell, Beauchaine, & Linehan, 2009; Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan, & Bohus, 2004; Linehan, 1993). They also tend to have a deficit of appropriate emotion regulation strategies (Carpenter & Trull, 2013; Glenn & Klonsky, 2009), leading to dysfunctional response patterns, namely drug use and in extreme cases, self-injury and suicidal behavior, during emotionally challenging events (Baer & Sauer, 2011; Rosenthal, Cheavens, Lejuez, & Lynch, 2005; Selby, Anestis, Bender, & Joiner Jr, 2009). These patterns may be related to substance use, as a strategy to “self-medicate” uncomfortable, negative, and dysregulated moods. They may also contribute to impulsive behavior such as syringe sharing that places PWID at risk of HIV and hepatitis C (HCV) infection.

The relief of negative affect is considered to be a predominant motivational force driving substance use (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004; Cheetham, Allen, Yucel, & Lubman, 2010; Kassel et al., 2007; Koob, 2013). For individuals who are substance dependent, the avoidance of withdrawal-induced negative affective states is an important motivating factor for continuing use. Indeed, avoiding withdrawal is a prime motivator of PWID behavior, including escalation of use, engaging in illegal behavior to procure drugs, engaging in risky injection behavior such as using shared syringes, and delaying treatment. Similarly, for individuals with BPD, substance use may provide temporary relief from mood instability, imbuing a sense of calm from otherwise turbulent emotions. Since people with BPD experience high reactivity to stressful events, and withdrawal is arguably a highly distressing experience, the impact on PWID with BPD is likely to be greater compared to PWID without BPD.

By contrast, enhancement of positive affect (PA) can also be an influential factor in driving substance use, particularly for individuals with anhedonia (impaired capacity to feel pleasure) (Lubman et al., 2009), whether pre-existing or substance-induced. Differentiating withdrawal reversal from affect enhancement effects of substance use (independent of withdrawal) is important to both theory development and intervention efforts (Kassel et al., 2007).

The linkages between emotion dysregulation, affective states, and injection drug use remain unclear, in part because of the difficulty capturing the shifting dynamics of mood in the context of substance use, and the limitations of retrospective reporting. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is an optimal method to study dynamic processes and to minimize problems of retrospective recall bias (Ebner-Priemer & Trull, 2009a, 2009b; Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008), and has been used extensively to study BPD (Nica & Links, 2009; Santangelo, Bohus, & Ebner-Priemer, 2012). Biases in retrospective reporting of past events and experiences have been demonstrated in a number of empirical studies and may be exacerbated by mental health problems. For example, individuals with BPD may underestimate positive emotions and overestimate negative emotions in retrospective accounts, while healthy control participants exhibit the opposite pattern (Ebner-Priemer et al., 2006). EMA allows the study of within-person variability that is not possible with cross-sectional observational studies that provide information about between-person differences only. Moreover, EMA allows the study of the interplay of mood and behavior over time in a real-life context.

To address these methodological weaknesses, we conducted EMA with PWID using a mobile phone app to assess mood, substance use, and injection risk behavior over a period of two weeks (Mackesy-Amiti & Boodram, 2018). In a baseline interview, participants completed a screening for BPD and other mental health problems, and measures of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity. The primary aim of the study was to investigate the effects of emotion dysregulation and negative affect on injection risk behavior. In this paper, we examine the contributions of BPD symptoms and difficulties with emotion regulation to positive and negative affect among PWID, in the context of intoxication and withdrawal effects associated with injection heroin use. We expected that a positive BPD screen would be associated with heightened negative affect and unstable affect (negative and positive), and would be unrelated to positive affect intensity. We expected that difficulties with emotion regulation would be associated with heightened negative affect and affect instability independent of BPD screening status. We also hypothesized that a positive BPD screen and emotion dysregulation would be associated with greater affective reactivity to withdrawal, that is, more intense negative affect during withdrawal. Study results may inform future intervention design and clinical practice with PWID who have difficulties with emotion regulation.

Methods

Participant recruitment

The research was conducted from February 2016 to June 2017 at two storefronts operated by Community Outreach Intervention Projects (COIP) in Chicago, Illinois, U.S. These locations provide harm reduction services including a syringe services program (SSP), HIV and HCV testing, counseling and case management, and prevention-focused street outreach. The focus of the study was injection risk behavior related to HIV and HCV injection, which especially affects younger PWID. People between the ages of 18 and 35 who injected illicit drugs in the past 30 days were eligible for the study. COIP’s SSP clients were invited to participate and were encouraged to refer other PWID to the study. Current injection was verified by trained counselors who inspected for injection stigmata and, when stigmata were absent or questionable, evaluated knowledge of the injection process. Age was verified with a driver’s license or a state identification card. Individuals who met the eligibility criteria were offered $10 to complete a screening questionnaire assessing symptoms of borderline personality disorder (MacLean Screening Instrument for BPD) (Zanarini et al., 2003). This screening was initially planned to ensure that at least 50% of our sample met the screening criteria for BPD. We expected 30–40% of subjects would score above the cutoff. It soon became clear that there would be no need to selectively sample on BPD screening, however we retained the 2-step procedure.

Procedures

Clients were recruited as they exited the SSP. After the interviewer administered the written informed consent procedure, participants completed a 45-minute baseline audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) and were compensated $25. Participants were then trained to use a mobile phone app to access the EMA survey and answer the questions. An Android mobile phone (4.4 KitKat OS, retail value $50) was provided, or participants could choose to use their own device. Phones were encrypted, password protected, and the EMA app and study-related messages were protected with an app lock. A mobile contact number was provided for participants to ask questions or report technical problems. Participants received mobile surveys four to six times a day for up to 15 days (including partial first day); they were paid for each survey completed and could earn up to $9/day. At the end of the observation period, participants were notified to return to the storefront for a 20-minute follow-up survey, and to collect their compensation. Study procedures were approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Ecological momentary assessment.

We used the ilumivu mEMA platform (ilumivu, Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA; www.ilumivu.com), that includes a web site for creating and managing surveys and data, and a mobile phone app to deliver the assessments. The mEMA app allows responses to be entered on the cell phone even when there is no active internet connection, although an internet connection is needed to upload data. Assessments were scheduled to occur 4, 5, or 6 times per day at random time-points within a 12-hour window (for more information see Mackesy-Amiti & Boodram (2018). Start and end time were decided by the participant at the beginning of the study to accommodate individual schedules (nearly all within 08:00 to 23:00). Each day for 2 weeks, participants received a notification when an assessment was requested, and reminders after 5 minutes and 10 minutes if the survey was not accessed. After 20 minutes the survey became unavailable until the next scheduled assessment. Participants received daily text message updates on their progress showing the number of assessments completed, and the number needed to reach the bonus level. If a participant missed all assessments on any day, he/she received a text reminder to contact study personnel for assistance. If a participant failed to complete any assessments for a second consecutive day, the site study coordinator attempted to contact the participant to offer assistance. If a participant failed to complete any assessments for a third day, he/she was notified to return to the storefront.

As reported in a previous paper (Mackesy-Amiti & Boodram, 2018), we varied the number of daily assessments across participants to examine the impact on participation and completion. All participants could potentially earn up to $9.00/day regardless of the assigned number of assessments. Participants earned a bonus of $10 for completing at least 80% of the assessments, and an additional $10 if they completed 90% of the assessments. Participants who used their own mobile phone received $25 to offset data usage. Participants who used a project phone received a minimum payout of $25 for returning the phone. Detailed information on participation rates is reported in our previous paper (Mackesy-Amiti & Boodram, 2018).

Measures

Baseline Assessment.

The following measures were included in the baseline ACASI (average time to complete 45 minutes).

Borderline Personality Disorder.

The McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder consists of ten yes/no items. The score is computed as the total number of items positively endorsed. Minor changes were made to adapt the instrument for computer-assisted self-administration. Internal consistency in the current sample was acceptable (alpha = 0.77). A cutoff score of 7 or above is suggested to identify persons with a high probability of BPD (Zanarini et al., 2003).

Sociodemographic and geographic characteristics.

The questionnaire assessed demographic characteristics including sex, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and highest level of education attained. Residential zip code, sources of income, places lived or slept, homelessness, and drug treatment were assessed with reference to the past six months. Current participation in drug treatment was also assessed.

Emotion dysregulation.

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scales (DERS) (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is a self-report instrument with six sub-scales, including (a) non-acceptance of emotional responses, reflecting a tendency to have negative secondary emotional responses to one’s negative emotions, (b) difficulties engaging in goal directed behavior, reflecting difficulties concentrating and accomplishing tasks when experiencing negative emotions (c) impulse control difficulties, reflecting difficulties remaining in control of one’s behavior when experiencing negative emotions, (d) lack of emotional awareness, reflecting the tendency to attend to and acknowledge emotions, (e) limited access to emotion regulation strategies, reflecting the belief that there is little that can be done to regulate emotions effectively, once an individual is upset, and (f) lack of emotional clarity, reflecting the extent to which individuals know and are clear about the emotions they are experiencing. Total and subscale scores are computed as the sum of item ratings, with higher scores indicating poorer emotion regulation. The DERS has been validated in samples of cocaine (Fox, Axelrod, Paliwal, Sleeper, & Sinha, 2007) and alcohol (Fox, Hong, & Sinha, 2008) dependent respondents. In the current sample, internal consistency was excellent for the total scale (alpha = 0.95) and good for all subscales (alpha = 0.82 − 0.87).

Trait negative affect.

The Personality Inventory for DSM-5 – Brief Form assesses 5 personality trait domains, each measured with 5 items rated on a 4-point scale from “very false or often false” to “very true or often true.” Trait negative affect is measured by items such as “I worry about almost everything,” and “I get irritated easily by all sorts of things.” We computed the average domain score. Internal consistency in the current sample was adequate (alpha = 0.76).

Depression screen.

The DSM-5 Self-Rated Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) was used to assess possible psychiatric problems across 13 domains. The instrument consists of 23 questions about problems experienced in the previous 2 weeks, with participants rating how much they have been bothered by these problems on a 5-point scale, from “not at all (0)” to “nearly every day (4)”. Potential depression was measured by the maximum rating on two items: 1) “Little interest or pleasure in doing things” and 2) “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless,” with a score of 3 to 4 indicating possible moderate to severe depression.

EMA Measures.

The EMA assessments included questions on current mood, context (where and with whom), current intoxication or withdrawal, injection since last report, and if applicable, recency of injection, and syringe and equipment sharing at last injection.

Momentary affect.

Participants were presented with a list of 20 mood descriptors, and were instructed to select up to four that described their current mood. Options also included “not sure” and “none of these”. The item set was developed largely based on the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule - Expanded Form (PANAS-X) (Watson & Clark, 1999; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) through three rounds of pretesting with PWID recruited at COIP store fronts. The items retained included two “serenity” items (calm, relaxed), six positive affect (PA) items (happy, energetic, excited, confident, determined, inspired) and ten PANAS negative affect (NA) items (angry, angry at self, ashamed, disgusted, distressed, downhearted, irritable, sad, scared, upset). We also included two new NA items relevant to this population (frustrated and worried). In pretesting, internal reliability was high for both the 6-item PA scale (alpha=0.81) and the 12-item NA scale (alpha=0.91), and the pick-4 format did not affect NA or PA intensity.

For each selected item, participants rated their mood intensity on a 10-point slider scale. Unselected items were scored zero, and the 12 mood ratings were averaged for all negative mood descriptors to create a measure of general NA at each assessment. Similarly, the six positive mood ratings were averaged to create a measure of general PA. When a participant selected “none” or “not sure” and no mood items were rated, affect intensity was scored as zero. PA and NA instability was measured by the mean absolute successive difference (MASD) (Ebner-Priemer et al., 2007), computed at the day level using only consecutive observations. In computing MASDs, observations with no mood ratings (none or not sure selected) were treated as missing rather than zero.

Context.

Participants were asked to indicate where they were: a) at home b) someone else’s home c) in a vehicle d) in a public place, or e) somewhere else; and who they were with (multiple selection): a) family b) friends c) boyfriend/girlfriend d) acquaintances e) strangers, f) no one.

Current state of intoxication/withdrawal.

Participants were asked, “Are you currently under the influence of alcohol or any drug (buzzed, high)?” and if they answered affirmatively they were asked which substance(s) (alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, opiate med, other). They were also asked, “Are you currently feeling any hangover or withdrawal effect?” and if so, related to which substance(s)? (alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, opiate med, other). “Other” substances specified were coded and categorized. Based on responses to these questions, we created indicators of opioid intoxication and opioid withdrawal.

Injection drug use.

Participants were asked, “Did you inject any drug since your last report?” and if they answered affirmatively they were asked “When did you last inject?” (7 options from “less than 1 hour ago” to “more than 12 hours ago.” If injection was reported, participants were asked additional questions about syringe and equipment sharing. Based on responses to these questions, we created a measure of recent injection indicating injection in the past 2 hours.

Analysis

We conducted mixed effects linear regression analyses on NA and PA intensity and instability, described in detail below, and mixed effects logistic regression on binary outcomes of selecting “none of these” and “not sure”. Analyses were conducted in Stata (version 15).

Affect intensity.

Invalid mood intensity scores due to participants rating more than four items or selecting mood items but not rating intensity were removed. We estimated associations between BPD screener and NA, DERS score and NA, and between BPD screener and DERS score. We estimated the association between DERS scores and BPD screen, adjusting for subject level covariates in an ordinary least squares regression model. DERS scores were converted to a standardized scale with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1 for the analysis. We conducted 3-level mixed effects regression analyses on total NA and PA intensity scores, with random intercepts for subject and day (i.e. observations nested within day, nested within subject), and an exponential residual error structure (a generalization of the AR covariance model that allows for unequally spaced and non-integer time values). We first entered within-subject factors in the model including time of day (morning, afternoon, evening/night), recent injection (within past two hours), current state of intoxication and withdrawal, and being in the company of friends, family, or romantic/sexual partner. Variables with p-values less than 0.20 were retained in the model. We next added between subject factors including sex, sexual orientation, age, race/ethnicity, drug treatment in the past six months, and baseline BPD screening result (score < 7 vs. ≥ 7), retaining covariates with p-values less than 0.20. We then added the DERS score in a separate model to test the independent contributions of positive BPD screen and emotion dysregulation. We also tested the interactions of BPD screen and DERS score with opioid withdrawal and intoxication.

Affect instability.

We conducted 2-level mixed effects regressions on NA and PA instability scores (MASD) with auto-regressive residual structure and robust standard errors. We tested the contributions of BPD screen and DERS score separately and together, adjusting for demographic variables of age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Results

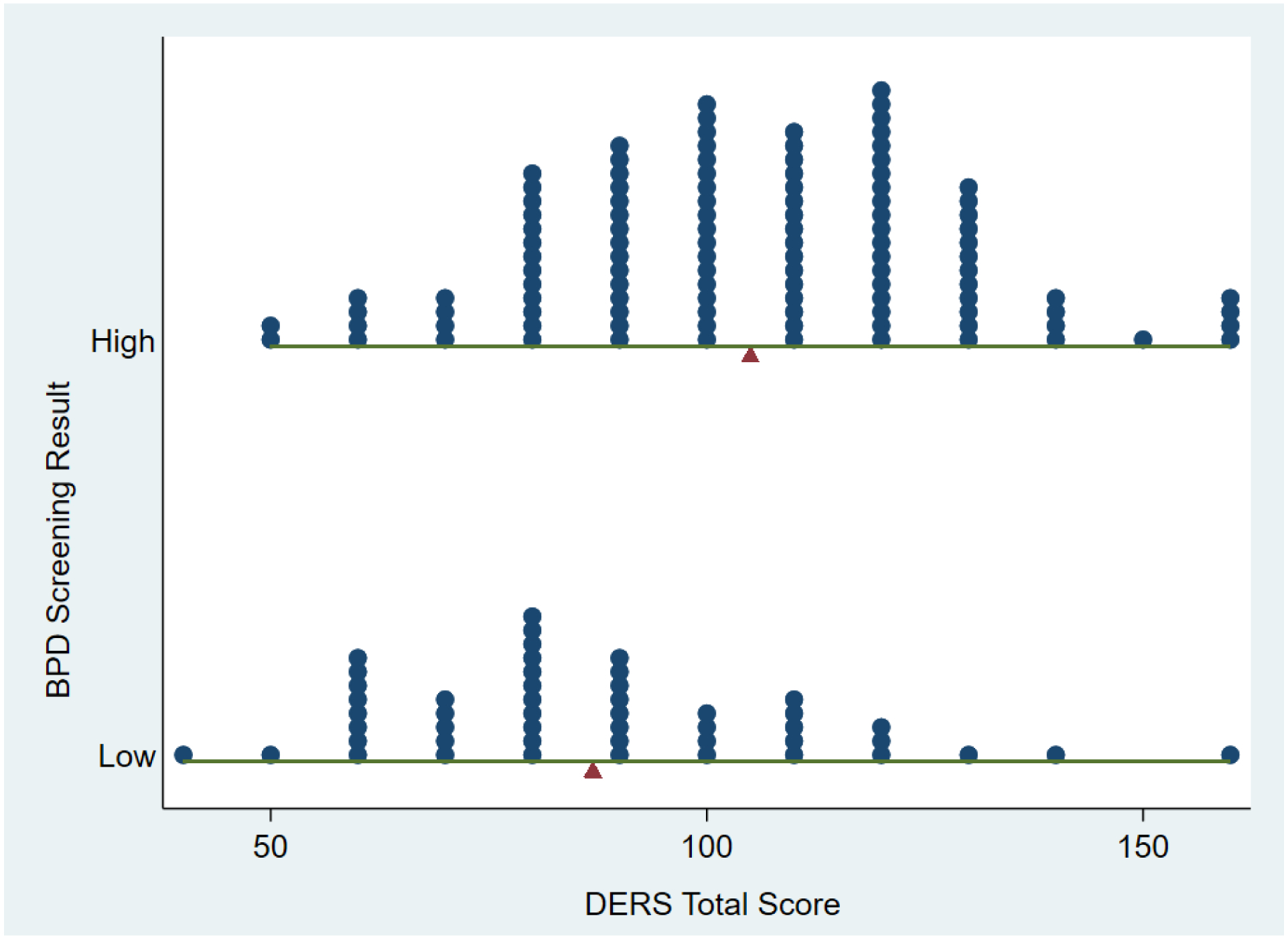

All eligible subjects agreed to participate and were enrolled in the study. Out of 185 participants with baseline data, 165 (89%) completed at least two mobile assessments; additionally four subjects were excluded due to missing data on the baseline instrument, leaving a sample of N = 161. Out of 5,429 EMA observations, 43 affect intensity scores were invalid, leaving a total of 5,386 EMA observations nested within 1,661 days for this analysis. Characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Seventy percent of subjects scored at or above the cutoff (≥ 7) on the BPD screener. Subjects with a positive BPD screen had higher DERS scores (t(159) = 4.41, p < 0.0001), greater trait negative affect (t(159) = 5.62, p < 0.0001), and were more likely to screen positive for potential depression (72% vs. 45%, X2(1, N = 161) = 11.12, p = 0.001). The distribution of DERS scores by BPD screening group is shown in Figure 1. In OLS regression, total DERS score was associated with BPD screen after adjusting for demographic covariates (bSTD = 0.71, SE = 0.17, 95% CI 0.38, 1.04).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample (N= 161)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 110 | 68.3 |

| Female | 51 | 31.7 |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 29.6 (3.9) | |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 137 | 85.1 |

| Non-Heterosexual | 24 | 14.9 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 101 | 62.7 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 12 | 7.5 |

| Hispanic | 37 | 23.0 |

| Other, non-Hispanica | 11 | 6.8 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| 8th grade or less | 9 | 5.6 |

| Some high school (9th to 11th grade) | 24 | 14.9 |

| High school graduate (12th grade) or GED | 63 | 39.1 |

| Some college or technical training | 50 | 31.1 |

| College graduate or higher | 15 | 9.3 |

| Residence (place slept most past 6 months) | ||

| Chicago | 95 | 59.0 |

| Outside of Chicago | 66 | 41.0 |

| Homelessness past 6 months | ||

| Not homeless | 63 | 39.1 |

| Thought of as homeless | 34 | 21.1 |

| Slept in non-dwelling > 7 nights | 64 | 39.8 |

| Frequency of injection past 6 months | ||

| Less than 4 days per week | 21 | 13.0 |

| Four to six days per week | 23 | 14.3 |

| Daily, 1 to 4 times per day | 71 | 44.1 |

| Daily, 5 or more times per day | 46 | 28.6 |

| In drug treatment past 6 months | ||

| No | 100 | 62.1 |

| Yes | 61 | 37.9 |

| Currently in drug treatment | ||

| No | 139 | 86.3 |

| Yes | 22 | 13.7 |

Includes Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, Black/African-American, mixed race, and unidentified race.

Figure 1.

Distribution of DERS Total Score by BPD Screening Result

Note: Pointer indicates group mean. Low BPD score: < 7; High BPD score ≥ 7

On average, participants completed 44% of scheduled EMA surveys, or 34 EMA observations per subject. Recent injection was reported on 35% of occasions, current opioid intoxication on 47% of occasions, and current opioid withdrawal on 17% of occasions. Recent injection was accompanied by opioid intoxication 87% of the time, and 65% of occasions of opioid intoxication were recent injection events. On mood assessment, “none of these” was selected at least once by 40% of participants on a total of 4% of all responses, and was selected more often by women (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 2.75, SE =1.17, 95% CI 1.19, 6.32, adjusted for within and between subjects covariates). Persons with a positive BPD screen were more likely to endorse “not sure” as a response (61% vs. 35% of persons endorsed at least once, 7.1% vs. 3.8% of all responses; OR = 3.07, SE = 1.15, 95% CI [1.47, 6.41]. DERS score also had an effect on “not sure” responses independent of positive BPD screen (Model X2 (2, N = 161) = 14.25, p = 0.0008; BPD aOR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.04, 5.11; DERS aOR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.03, 1.79).

Affect intensity

NA scores had a range of 0 to 3.33 (40/12), a mean of 0.67 (SDB = 0.52, SDW = 0.72), and intra-class correlation of 0.31; PA scores had a range of 0 to 6.67 (40/6), a mean of 0.73 (SDB = 0.74, SDW = 1.00), and intra-class correlation of 0.32. In initial mixed regression models with only time of day as a covariate, total NA was associated weakly negatively with opioid intoxication (b = −0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI −0.11, 0.01), and strongly positively with withdrawal (b = 0.29, SE = 0.04, 95% CI 0.22, 0.36). Total PA was positively associated with recent injection (b = 0.09, SE = 0.03, 95% CI 0.03, 0.15) and opioid intoxication (b = 0.20, SE = 0.04, 95% CI 0.12, 0.28), and negatively associated with withdrawal (b = −0.33, SE = 0.05, 95% CI −0.42, −0.24). Intoxication was not associated with NA after adjusting for withdrawal, and recent injection was not associated with PA after adjusting for intoxication.

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariable mixed effects regression models on affect intensity. In the first model including BPD screen and covariates, NA increased from morning to evening, current withdrawal symptoms and recent injection were associated with greater NA, and being with friends was associated with less NA. To understand the association between recent injection and NA, we conducted supplemental analyses (not shown) to test the association between recent injection and each component of NA in mixed effects ordinal logistic regressions adjusting for time of day and withdrawal. The association with recent injection was significant (p < .01) for ratings of ashamed (b=0.40, 95% CI 0.11–0.68), angry at self (b=0.49, 95% CI 0.19–0.79), and disgusted (b=0.39, 95% CI 0.10–0.69). Older age, non-heterosexual orientation, and non-white non-Hispanic race/ethnicity were associated with greater mean NA, as was a positive BPD screen. Drug treatment was not associated with NA. DERS score was positively associated with NA independently of BPD screening status (Model 2). No interactions between BPD screen or DERS and opioid withdrawal or intoxication on NA were detected, i.e. the effect of withdrawal on NA was not moderated by positive BPD screen or emotion dysregulation (Table 3).

Table 2.

Mixed effects regression model results for negative and positive affect Intensity (N=161)

| Negative affect | Positive affect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | 95% Conf. Int. | p-value | Coef. | Std. Err. | 95% Conf. Int. | p-value | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| With friends | −0.071 | 0.029 | (−0.128 – −0.014) | 0.015 | 0.194 | 0.054 | (0.088 – 0.300) | < 0.001 |

| With rom. partner | - | 0.109 | 0.051 | (0.009 – 0.209) | 0.033 | |||

| Injected past 2 hours | 0.063 | 0.028 | (0.008 – 0.118) | 0.025 | −0.052 | 0.033 | (−0.115 – 0.012) | 0.112 |

| High on opioids | - | 0.143 | 0.045 | (0.055 – 0.232) | 0.002 | |||

| Withdrawal | 0.308 | 0.037 | (0.235 – 0.382) | < 0.001 | −0.271 | 0.046 | (−0.362 – −0.180) | < 0.001 |

| Female vs. Male | 0.101 | 0.081 | (−0.057 – 0.260) | 0.211 | −0.219 | 0.124 | (−0.462 – 0.023) | 0.076 |

| Heterosexual | −0.259 | 0.130 | (−0.513 – −0.004) | 0.047 | - | |||

| Age | 0.024 | 0.008 | (0.008 – 0.041) | 0.004 | −0.026 | 0.017 | (−0.059 – 0.006) | 0.112 |

| Race/ethnicity (vs. NH White) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | −0.068 | 0.077 | (−0.219 – 0.083) | 0.375 | 0.213 | 0.162 | (−0.104 – 0.529) | 0.188 |

| Other (NH) | 0.273 | 0.121 | (0.037 – 0.510) | 0.023 | 0.646 | 0.183 | (0.287 – 1.005) | < 0.001 |

| Drug treatment, 6 mo. | −0.036 | 0.075 | (−0.182 – 0.110) | 0.631 | 0.209 | 0.124 | (−0.035 – 0.453) | 0.093 |

| Time of day (vs. Morning) | ||||||||

| Afternoon | 0.054 | 0.024 | (0.007 – 0.100) | 0.023 | - | |||

| Evening/Night | 0.084 | 0.027 | (0.032 – 0.136) | 0.002 | - | |||

| BPD pos. screen | 0.152 | 0.073 | (0.009 – 0.296) | 0.038 | 0.113 | 0.125 | (−0.131 – 0.358) | 0.365 |

| Random intercepts (variance) | ||||||||

| Subject | 0.177 | 0.039 | (0.115 – 0.272) | 0.408 | 0.084 | (0.272 – 0.612) | ||

| Day | 0.082 | 0.017 | (0.055 – 0.122) | 0.154 | 0.031 | (0.104 – 0.228) | ||

| Residual: Exponential | ||||||||

| rho | 0.233 | 0.085 | (0.107 – 0.435) | 0.288 | 0.051 | (0.199 – 0.397) | ||

| var(e) | 0.443 | 0.030 | (0.388 – 0.505) | 0.874 | 0.077 | (0.736 – 1.039) | ||

| Model 2a | ||||||||

| BPD pos. screen | 0.084 | 0.069 | (−0.051 – 0.218) | 0.221 | 0.200 | 0.129 | (−0.052 – 0.453) | 0.120 |

| DERS (standardized) | 0.092 | 0.039 | (0.017 – 0.168) | 0.017 | −0.118 | 0.057 | (−0.230 – −0.007) | 0.037 |

Model 2 included all the covariates from Model 1

NH: Non-Hispanic

Table 3.

Tests of moderation effects in mixed effects regression models on negative and positive affect intensity (N=161)

| Negative affecta | Positive affectb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | 95% Conf. Int. | p-value | Coef. | Std. Err. | 95% Conf. Int. | p-value | |

| Opioid withdrawal | 0.279 | 0.064 | (0.154 – 0.405) | < 0.001 | −0.178 | 0.085 | (−0.344 – −0.011) | 0.036 |

| BPD screen positive | 0.146 | 0.072 | (0.005 – 0.287) | 0.043 | 0.134 | 0.126 | (−0.112 – 0.380) | 0.287 |

| Opioid withdrawal × BPD screen | 0.039 | 0.076 | (−0.111 – 0.188) | 0.613 | −0.126 | 0.099 | (−0.321 – 0.069) | 0.204 |

| Opioid withdrawal | 0.309 | 0.040 | (0.230 – 0.388) | < 0.001 | −0.273 | 0.049 | (−0.369 – −0.178) | < 0.001 |

| DERS score (std) | 0.107 | 0.040 | (0.029 – 0.184) | 0.007 | −0.089 | 0.056 | (−0.199 – 0.020) | 0.110 |

| Opioid withdrawal × DERS (std) | −0.010 | 0.036 | (−0.080 – 0.060) | 0.776 | 0.014 | 0.043 | (−0.070 – 0.097) | 0.750 |

| Opioid intoxication | 0.036 | 0.055 | (−0.073 – 0.144) | 0.517 | 0.054 | 0.064 | (−0.072 – 0.180) | 0.402 |

| BPD screen positive | 0.086 | 0.074 | (−0.059 – 0.231) | 0.246 | 0.053 | 0.132 | (−0.206 – 0.312) | 0.687 |

| Opioid intoxication × BPD screen | −0.005 | 0.066 | (−0.135 – 0.125) | 0.938 | 0.124 | 0.076 | (−0.024 – 0.272) | 0.102 |

| Opioid intoxication | 0.031 | 0.032 | (−0.033 – 0.094) | 0.342 | 0.139 | 0.046 | (0.049 – 0.228) | 0.002 |

| DERS score (std) | 0.088 | 0.042 | (0.005 – 0.172) | 0.037 | −0.101 | 0.057 | (−0.212 – 0.010) | 0.075 |

| Opioid intoxication × DERS (std) | 0.010 | 0.026 | (−0.041 – 0.061) | 0.710 | 0.029 | 0.029 | (−0.027 – 0.085) | 0.317 |

adjusted for time of day, recent injection, opioid withdrawal, being with friends, sex, sexual orientation, age, race/ethnicity, and drug treatment in the past six months

adjusted for recent injection, opioid intoxication, opioid withdrawal, being with friends, being with a romantic partner, sex, age, race/ethnicity, and drug treatment in the past six months

Greater PA was associated with being with friends or a romantic partner, opioid intoxication, absence of withdrawal, and non-white non-Hispanic race/ethnicity, and weakly associated with receiving drug treatment in the past six months. PA was not associated with BPD screen, but was negatively associated with DERS score adjusting for covariates. There were no statistically significant interactions between BPD screen or DERS and opioid withdrawal or intoxication on PA. However, the marginal effect of opioid intoxication on PA was significantly greater than zero only for subjects with a positive BPD screen (dy/dx | BPD screen positive = 0.18, 95% CI 0.07 – 0.28).

Affect instability.

Table 4 shows the results of mixed effects regressions on affect instability; 10 participants were missing MASD instability scores as they did not have any consecutive valid observations. A total of 2,707 difference scores nested within 1,139 days contributed to the analysis. A positive BPD screen was associated with greater instability of both PA and NA, while DERS score was associated only with instability of NA.

Table 4.

Mixed effects regression models on negative and positive affect instability (N=151)

| Negative affect instability | Positive affect instability | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | 95% Conf. Int. | p-value | Coef. | Std. Err. | 95% Conf. Int. | p-value | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| Female vs. Male | 0.205 | 0.060 | (0.088 – 0.322) | 0.001 | −0.028 | 0.099 | (−0.223 – 0.166) | 0.774 |

| Age | 0.004 | 0.008 | (−0.012 – 0.019) | 0.633 | −0.025 | 0.013 | (−0.050 – 0.001) | 0.056 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.028 | 0.065 | (−0.100 – 0.156) | 0.668 | −0.030 | 0.117 | (−0.259 – 0.198) | 0.795 |

| Other (NH) vs. White (NH) | 0.217 | 0.085 | (0.052 – 0.383) | 0.010 | 0.336 | 0.123 | (0.094 – 0.577) | 0.007 |

| BPD pos. screen | 0.119 | 0.051 | (0.020 – 0.219) | 0.019 | 0.178 | 0.088 | (0.004 – 0.351) | 0.045 |

| Random intercepts (variance) | ||||||||

| Subject | 0.058 | 0.013 | (0.037 – 0.091) | 0.173 | 0.052 | (0.096 – 0.313) | ||

| Residual: AR(1) | ||||||||

| rho | −0.089 | 0.037 | (−0.160 – −0.016) | 0.148 | 0.052 | (0.044 – 0.248) | ||

| var(e) | 0.286 | 0.028 | (0.237 – 0.346) | 0.571 | 0.057 | (0.470 – 0.694) | ||

| Model 2a | ||||||||

| BPD pos. screen | 0.065 | 0.054 | (−0.040 – 0.171) | 0.226 | 0.210 | 0.091 | (0.031 – 0.389) | 0.021 |

| DERS (standardized) | 0.065 | 0.027 | (0.013 – 0.118) | 0.014 | −0.041 | 0.047 | (−0.132 – 0.051) | 0.382 |

Model 2 included all the covariates from Model 1

Discussion

This study evaluated the associations of negative and positive affect intensity and instability as measured by EMA with borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptoms and difficulties with emotion regulation among PWID, in the context of intoxication and withdrawal effects. Consistent with prior research, participants who screened positive for BPD reported higher levels of momentary negative affect (NA) during the two-week observation period. We also detected greater instability of NA and PA among PWID with a positive BPD screen in this study that had a sampling frequency of 2 to 3 hours. Furthermore, evidence supported the independent role of difficulties with emotion regulation on NA intensity and instability. These findings indicate that emotion dysregulation is an appropriate target for assessment and intervention in this population, more so than BPD screening. Contrary to expectations, we found no evidence that BPD symptoms or emotion dysregulation moderated affective response to withdrawal.

Much of the research on substance use and NA comes from studies on tobacco/nicotine or alcohol, and its relevance to heroin/opioid use and injection drug use may be questioned (Kassel et al., 2007). In this study we examined associations between momentary negative and positive affect and concurrent reported states of intoxication and withdrawal, and recent injection. As expected, we found that negative affect was associated with withdrawal, but NA was also higher when recent injection was reported, apparently due to increased shame and self-directed anger. Intoxication was not associated with less NA after adjusting for withdrawal symptoms, but was associated with greater PA. That is, within-person differences in NA between intoxicated and non-intoxicated times could be accounted for by relief of withdrawal symptoms, while enhancement of PA occurred above that due to relief from withdrawal symptoms. Although the test of moderation was not statistically significant, enhancement of PA during opioid intoxication was evident only among PWID with a positive BPD screen. This pattern may be related to symptoms of anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure) in PWID with BPD. Marissen and colleagues (Marissen, Arnold, & Franken, 2012) found that women with BPD reported more symptoms of anhedonia compared to control subjects, and that among women with BPD anhedonia was associated with dysfunctional impulsivity. Chronic opioid use may exacerbate these symptoms (Garfield et al., 2017; Garfield, Lubman, & Yücel, 2013; Lubman et al., 2018); heroin users may experience anhedonia when not intoxicated, and seek stimulation of positive affect through drug use (Lubman et al., 2009).

Whether premorbid or substance-induced, anhedonia can be a significant barrier to cessation of drug use (Garfield et al., 2013). Anhedonia is positively associated with drug cravings among abstinent opioid-dependent subjects (Janiri et al., 2005; Martinotti, Cloninger, & Janiri, 2008), however there is little known about the impact of anhedonia on treatment outcomes (Kiluk, Yip, DeVito, Carroll, & Sofuoglu, 2019). Psychosocial interventions for substance abuse include approaches such as cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) and mindfulness training that focus on building distress tolerance and coping skills while managing negative thought patterns that produce negative affect. Findings in this study suggest that additional approaches should help PWID identify alternative strategies to experience positive feelings. For example, behavior therapy emphasizes engaging in activities that offer “positive rewards” to improve mood. These activities are selected by the individual and can include anything from listening to music, taking a walk, and reaching out for support. It is noteworthy that many of the activities also serve to help individuals wait-out or tolerate emotional distress. Similarly, prevention of relapse during treatment of opioid dependence may require more attention to deficits in PA as well as evidence-based methods to cope with negative affect. PWID may benefit from developing an action plan that identifies triggers of negative affect and facilitators of positive affect, and specific behaviors to avoid/cope with the former and seek out the latter. Interventions to assist with the application of emotion regulation skills in “real-time” may increase the effectiveness of behavioral therapy. In this study, being with friends was a strong predictor of PA, highlighting the importance of building healthy social relationships to support substance use cessation.

We used a momentary mood assessment that allowed participants to select four words from a list to describe their current feelings, and to rate the intensity of their feelings on those four descriptors. This pick-4 measure significantly reduces the burden on the participant, and still provides an adequate assessment of the respondent’s mood on multiple dimensions. This could be an effective tool for clinicians and substance use providers seeking to focus their treatment on the feelings that are most relevant to PWID.

Limitations

Participants in this study completed less than half of scheduled EMA assessments, potentially reducing the quality of the data collected. We reported on correlates of response rate in a previous paper (Mackesy-Amiti & Boodram, 2018). This study did not include a full assessment of borderline personality disorder. Findings related to a positive BPD screen may or may not be true for comparisons between persons with and without the personality disorder.

Conclusions

Our study findings support the viability of EMA using mobile phones to study patterns of affect intensity and instability among PWID. Difficulties with emotion regulation among PWID predicted greater intensity and instability of NA independently of BPD screen, indicating that emotion dysregulation is an appropriate target for assessment and intervention in this population. We did not find evidence of greater affective reactivity to withdrawal due to BPD symptoms or emotion dysregulation. While relief of NA due to withdrawal is understood to be an important motivation for continued drug use, the role of enhancement of PA deserves further study. Future research should consider how to deliver “real-time” interventions for emotion regulation skills.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health grant number R21DA039010. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank study participants for the time and effort they contributed to this study, and acknowledge the dedication of our staff members who conducted the interviews and otherwise operated field sites in a manner welcoming to potential participants.

We thank study participants for the time and effort they contributed to this study, and acknowledge the dedication of our staff members who conducted the interviews and otherwise operated field sites in a manner welcoming to potential participants.

Footnotes

Portions of this research were presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Psychological Science, May 2018. A preprint of this paper has been made available on PsyArXiv, doi: 10.31234/osf.io/ar3nf

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). DSM-5 Self-Rated Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure—Adult.

- Baer R, & Sauer S (2011). Relationships between depressive rumination, anger rumination, and borderline personality features. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 2(2), 142–150. doi: 10.1037/a0019478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, & Fiore MC (2004). Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review, 111(1), 33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter RW, & Trull TJ (2013). Components of emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder: A review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15(1), 335. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0335-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter RW, Wood PK, & Trull TJ (2016). Comorbidity of borderline personality disorder and lifetime substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30(3), 336–350. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2015_29_197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham A, Allen NB, Yucel M, & Lubman DI (2010). The role of affective dysregulation in drug addiction. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(6), 621–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KW, Banducci AN, Guller L, Macatee RJ, Lavelle A, Daughters SB, & Lejuez CW (2011). An examination of psychiatric comorbidities as a function of gender and substance type within an inpatient substance use treatment program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118(2–3), 92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, & Grant BF (2007). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(5), 566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comtois KA, & Carmel A (2016). Borderline personality disorder and high utilization of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization: Concordance between research and clinical diagnosis. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 43(2), 272–280. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9416-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, & Grant BF (2006). Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(2), 247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, & Linehan MM (2009). A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending Linehan’s theory. Psychological Bulletin, 135(3), 495–510. doi: 10.1037/a0015616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Kuo J, Kleindienst N, Welch SS, Reisch T, Reinhard I, … Bohus M (2007). State affective instability in borderline personality disorder assessed by ambulatory monitoring. Psychological Medicine, 37(7), 961–970. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Kuo J, Welch SS, Thielgen T, Witte S, Bohus M, & Linehan MM (2006). A valence-dependent group-specific recall bias of retrospective self-reports - A study of borderline personality disorder in everyday life. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(10), 774–779. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000239900.46595.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, & Trull TJ (2009a). Ambulatory assessment: An innovative and promising approach for clinical psychology. European Psychologist, 14(2), 109–119. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.14.2.109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, & Trull TJ (2009b). Ecological momentary assessment of mood disorders and mood dysregulation. Psychological Assessment, 21(4), 463–475. doi: 10.1037/a0017075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Axelrod SR, Paliwal P, Sleeper J, & Sinha R (2007). Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control during cocaine abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 89(2–3), 298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Hong KA, & Sinha R (2008). Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control in recently abstinent alcoholics compared with social drinkers. Addictive Behaviors, 33(2), 388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield JBB, Cotton SM, Allen NB, Cheetham A, Kras M, Yücel M, & Lubman DI (2017). Evidence that anhedonia is a symptom of opioid dependence associated with recent use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 177, 29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield JBB, Lubman DI, & Yücel M (2013). Anhedonia in substance use disorders: A systematic review of its nature, course and clinical correlates. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48(1), 36–51. doi: 10.1177/0004867413508455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, & Klonsky ED (2009). Emotion dysregulation as a core feature of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 23(1), 20–28. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, & Pickering RP (2004). Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(7), 948–958. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v65n0711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, … Kaplan K (2004). Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(8), 807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. doi: 10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE (2003). Contrasting the views of substance misuse and mental health treatment providers on treating the dually diagnosed. Substance Use and Misuse, 38(10), 1433–1446. doi: 10.1081/JA-120023393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Stein JA, Weisner C, Chi F, & Moos R (2010). Predictors of longitudinal substance use and mental health outcomes for patients in two integrated service delivery systems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 110(1), 92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Degenhardt L, & Teesson M (2009). Understanding comorbidity between substance use, anxiety and affective disorders: Broadening the research base. Addictive Behaviors, 34(6–7), 526–530. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havassy BE, Alvidrez J, & Mericle AA (2009). Disparities in use of mental health and substance abuse services by persons with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatric Services, 60(2), 217–223. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.2.217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janiri L, Martinotti G, Dario T, Reina D, Paparello F, Pozzi G, … De Risio S (2005). Anhedonia and substance-related symptoms in detoxified substance-dependent subjects: A correlation study. Neuropsychobiology, 52(1), 37–44. doi: 10.1159/000086176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Greenstein JE, Evatt DP, Roesch LL, Veilleux JC, Wardle MC, & Yates MC (2007). Negative Affect and Addiction In al’Absi M (Ed.), Stress and Addiction (pp. 171–189). Burlington: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Yip SW, DeVito EE, Carroll KM, & Sofuoglu M (2019). Anhedonia as a key clinical feature in the maintenance and treatment of opioid use disorder. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1190–1206. doi: 10.1177/2167702619855659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF (2013). Negative reinforcement in drug addiction: The darkness within. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 23(4), 559–563. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, & Bohus M (2004). Borderline personality disorder. Lancet, 364(9432), 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (1993). Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Lubman DI, Garfield JBB, Gwini SM, Cheetham A, Cotton SM, Yücel M, & Allen NB (2018). Dynamic associations between opioid use and anhedonia: A longitudinal study in opioid dependence. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 32(9), 957–964. doi: 10.1177/0269881118791741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubman DI, Yucel M, Kettle JWL, Scaffidi A, MacKenzie T, Simmons JG, & Allen NB (2009). Responsiveness to drug cues and natural rewards in opiate addiction: Associations with later heroin use. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(2), 205–212. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackesy-Amiti ME, & Boodram B (2018). Feasibility of ecological momentary assessment to study mood and risk behavior among young people who inject drugs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 187, 227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackesy-Amiti ME, & Donenberg G (2019). Negative affect and emotion dysregulation among people who inject drugs: An ecological momentary assessment study. Preprint. PsyArXiv. DOI: 10.31234/osf.io/ar3nf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackesy-Amiti ME, Donenberg GR, & Ouellet LJ (2012). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among young injection drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 124(1–2), 70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marissen MAE, Arnold N, & Franken IHA (2012). Anhedonia in borderline personality disorder and its relation to symptoms of impulsivity. Psychopathology, 45(3), 179–184. doi: 10.1159/000330893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinotti G, Cloninger CR, & Janiri L (2008). Temperament and character inventory dimensions and anhedonia in detoxified substance-dependent subjects. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 34(2), 177–183. doi: 10.1080/00952990701877078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Darke S, Ross J, & Lynskey M (2004). Young people with heroin dependence: Findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS). Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 27(1), 67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrick H, & Brady K (2003). Current review of the comorbidity of affective, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 16(3), 261–270. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000069080.26384.d8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nica E, & Links P (2009). Affective instability in borderline personality disorder: Experience sampling findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 11, 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris JMD, & Black DWMD (2015). Borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder: What is the difference and why does it matter? Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203(1), 3–7. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Llera MC, Domingo-Salvany A, Brugal MT, Silva TC, Sanchez-Niubo A, & Torrens M (2006). Psychiatric comorbidity in young heroin users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 84(1), 48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M, Cheavens J, Lejuez C, & Lynch T (2005). Thought suppression mediates the relationship between negative affect and borderline personality disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43, 1173–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR, Ball S, Tennen H, Poling J, & Triffleman E (1998). Personality disorders in substance abusers: Relation to substance use. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 186(2), 87–95. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199802000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo P, Bohus M, & Ebner-Priemer UW (2012). Ecological momentary assessment in borderline personality disorder: A review of recent findings and methodological challenges. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28(4), 555–576. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2012_26_067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer I, & Najavits LM (2007). Clinical challenges in the treatment of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(6), 614–618. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f0ffd9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Anestis MD, Bender TW, & Joiner TE Jr (2009). An exploration of the emotional cascade model in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(2), 375–387. doi: 10.1037/a0015711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, & Hufford MR (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrens M, Gilchrist G, & Domingo-Salvany A (2011). Psychiatric comorbidity in illicit drug users: Substance-induced versus independent disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 113(2–3), 147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks-Brown C, Durbin J, & Burr R (2000). Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(2), 235–253. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00028-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, & Aldao A (2015). Editorial overview: New directions in the science of emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, iv–x. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R (2001). Co-morbidity of personality disorders in individuals with substance use disorders. European Psychiatry, 16(5), 274–282. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(01)00578-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, & Clark LA (1999). The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form. University of Iowa; Retrieved from http://www2.psychology.uiowa.edu/faculty/Watson/PANAS-X.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, Boulanger JL, Frankenburg FR, & Hennen J (2003). A screening measure for BPD: The McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(6), 568–573. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.6.568.25355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M (1999). Differences between clinical and research practices in diagnosing borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(10), 1570–1574. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M (2017). Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder Current Psychiatry, 16(10), 13–19. [Google Scholar]