Abstract

Objective:

Seriously ill adults with multiple chronic conditions (MCC) who receive palliative care may benefit from improved symptom burden, healthcare utilization and cost, caregiver stress, and quality of life. To guide research involving serious illness and MCC, palliative care can be integrated into a conceptual model to develop future research studies to improve care strategies and outcomes in this population.

Methods:

The adapted conceptual model was developed based on a thorough review of the literature, in which current evidence and conceptual models related to serious illness, MCC, and palliative care were appraised. Factors contributing to patients’ needs, services received, and service-related variables were identified. Relevant patient outcomes and evidence gaps are also highlighted.

Results:

Fifty-eight articles were synthesized to inform the development of an adapted conceptual model including serious illness, MCC, and palliative care. Concepts were organized into four main conceptual groups including Factors Affecting Needs (sociodemographic and social determinants of health), Factors Affecting Services Received (health system; research, evidence base, dissemination, and health policy; community resources), Service-Related Variables (patient visits, service mix, quality of care, patient information, experience), and Outcomes (symptom burden, quality of life, function, advance care planning, goal-concordant care, utilization, cost, death, site of death, satisfaction).

Discussion:

The adapted conceptual model integrates palliative care with serious illness and multiple chronic conditions. The model is intended to guide the development of research studies involving seriously ill adults with MCC and aid researchers in addressing relevant evidence gaps.

Keywords: conceptual model, palliative care, serious illness, multiple chronic conditions, research, clinical complexity

Introduction

Adults with multiple chronic conditions (MCC) possess two or more chronic conditions that result in limitations in activities of daily living and require regular medical care.23 In the U.S., over 40% of adults have MCC.1,2,61 The complexity of MCC increases in the setting of serious illness, which is characterized by complex care, high symptom burden, compromised quality of life, increased healthcare utilization and cost, and significant caregiver strain.12 To provide optimal care for seriously ill adults with MCC, research priorities must focus on the complexity of serious illness and MCC, and the integration of palliative care is essential in improving outcomes for this complex population.3 For a seriously ill adult with MCC, the likelihood of experiencing inappropriate or fragmented care rises across the healthcare spectrum, which creates a gap between the needs of the patients and the services they receive.4 In light of the fact that improving health outcomes and reducing costs for seriously ill adults with MCC has been prioritized by healthcare systems, it is imperative that research priorities focus on the integration of palliative care in the context of serious illness and MCC. The underlying evidence base with which to address the clinical complexity of MCC using palliative care in seriously ill adults is limited. Furthermore, the development and execution of conceptually sound studies with this population is needed.19 A comprehensive and integrative conceptual model is useful for researchers seeking to study how to integrate palliative care in serious illness and MCC care paradigms. This paper presents a conceptual model that integrates palliative care within the conceptual realm of serious illness and MCC.

In recent years, the evidence base enhancing the understanding of serious illness has grown.5,6 Kelley and colleagues5 developed a conceptual framework to aid clinicians in identifying factors associated with treatment intensity in individuals with serious illness to improve the quality and efficiency of care. Sanders et al.6 created a conceptual framework to ascertain the relationship between serious illness communication and goal-concordant care, which is care that aligns with the individual’s values, preferences and goals. While these frameworks touch on issues of clinical complexity in serious illness, they are not specifically focused on seriously ill adults with MCC. Other models have integrated palliative care into a serious illness framework without including a focus on MCC.7–10 Hodiamont and colleagues11 explored the concept of complexity as it relates to palliative care to describe resulting needs and care demands associated with an individual’s clinical complexity by describing a ‘complex adaptive system’ consisting of physical, psycho-spiritual, and socio-cultural subsystems.11 The aforementioned models all provide conceptualization of care or research involving palliative care, serious illness or MCC. However, a conceptual model that integrates palliative care within the serious illness and MCC research paradigm has not been developed.

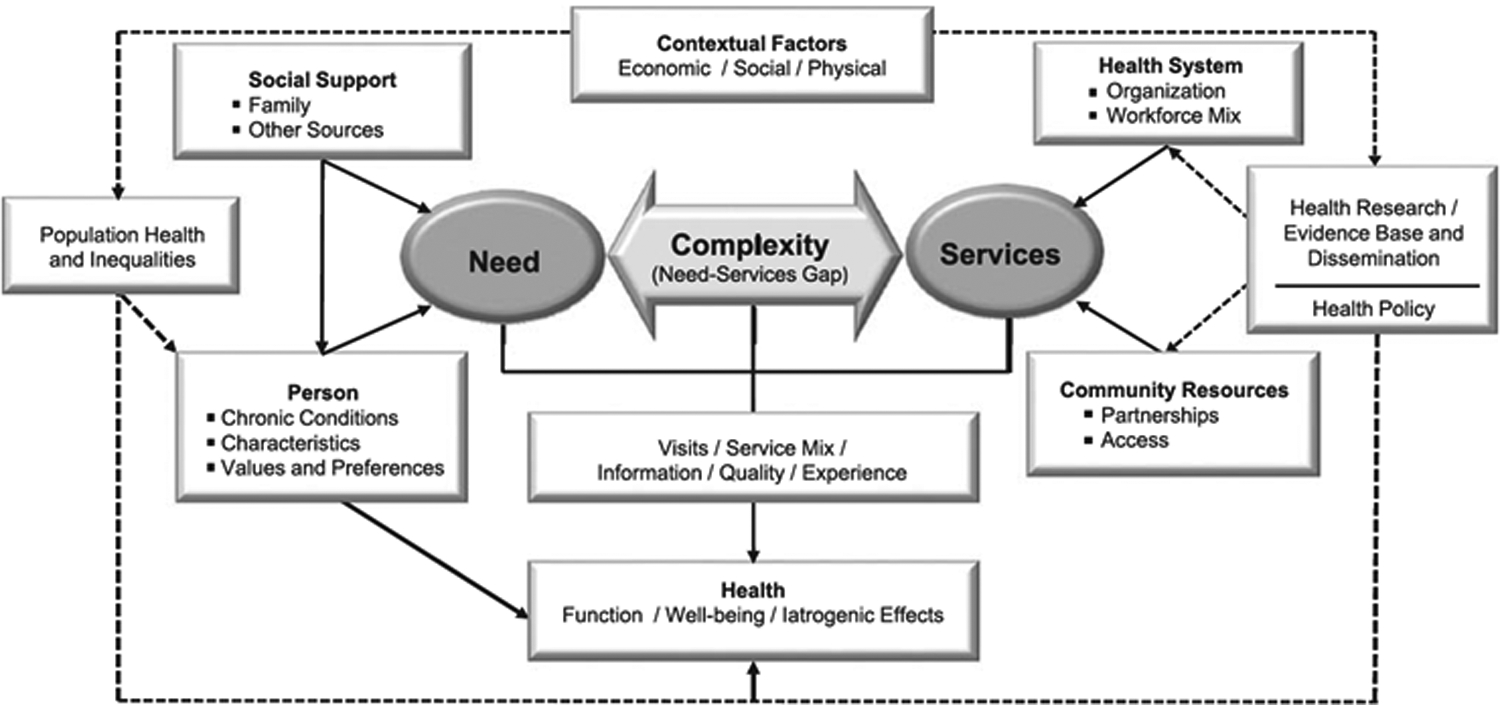

The AHRQ MCCRN Conceptual Model

A conceptual model that addresses the complexity of MCC in research and practice was presented by Grembowski and colleagues24 (Figure 1). This model was developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality MCC Research Network (AHRQ MCCRN) and operationalized complexity as the mitigating factor in the gap between the needs of adults with MCC and services they receive.25–31 Three main concepts were highlighted in the model including patient’s needs, complexity, and services received. The need side of the model incorporates contextual factors such as population health and inequalities, person-specific factors such as a diagnoses, characteristics, values, preferences, and social support. On the service side of the model, health system factors (i.e., organization and workforce mix), community resources (i.e., partnerships and access), research, evidence base, dissemination, and health policy are presented. Clinical complexity is central in this model as contributing to the gap between need and services for individuals with MCC. Complexity is influenced by the service mix, the number of patient visits, patient information, quality of care, and the patient experience. Person-specific factors include outcomes (i.e., health status, function, well-being of the patient, iatrogenic effects). While this model conceptualizes MCC, serious illness is not addressed within its framework. It is crucial to differentiate seriously ill adults with MCC to properly address the complexity of care, which sets the groundwork for research studies seeking to improve patient outcomes. For example, an individual with well-managed hypertension and type 2 diabetes may not be considered seriously ill. In comparison, an individual with congestive heart failure and lymphoma may have a burdensome symptom profile and perhaps a worse quality of life.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of the role of clinical complexity in the care of patients with multiple chronic conditions (MCC) (reprinted with permission from Grembowski et al.24)

Palliative care provides person- and family-centered care to those with serious illness to help manage symptom burden and improve quality of life19,58 Through expert assessment and management of pain and other symptoms, palliative care addresses the multifaceted consequences of serious illness (i.e. functional, psychological, practical, and spiritual) and provides caregiver support.19,20,58,59 There are three widely accepted types of palliative care.21 Primary palliative care is delivered across settings by non-specialist providers who manage symptoms, address spiritual and psychosocial needs, and provide therapeutic communication about advanced care planning and end of life care. Secondary palliative care is provided in palliative care clinics or inpatient settings where specialty-trained practitioners are consultants or supplementary to other inpatient teams to address serious illness needs of patients. Those who deliver tertiary palliative care provide primary management of illness, palliative sedation or delirium management.21 Patient and caregiver outcomes have been studied and shown to improve across a variety of palliative care approaches.22 The purpose of this paper is to present an adapted conceptual model integrating palliative care in serious illness and MCC research. The development of a conceptual model of this nature has potential to inform research that focuses on integrating palliative care for seriously ill adults with MCC.

Methods

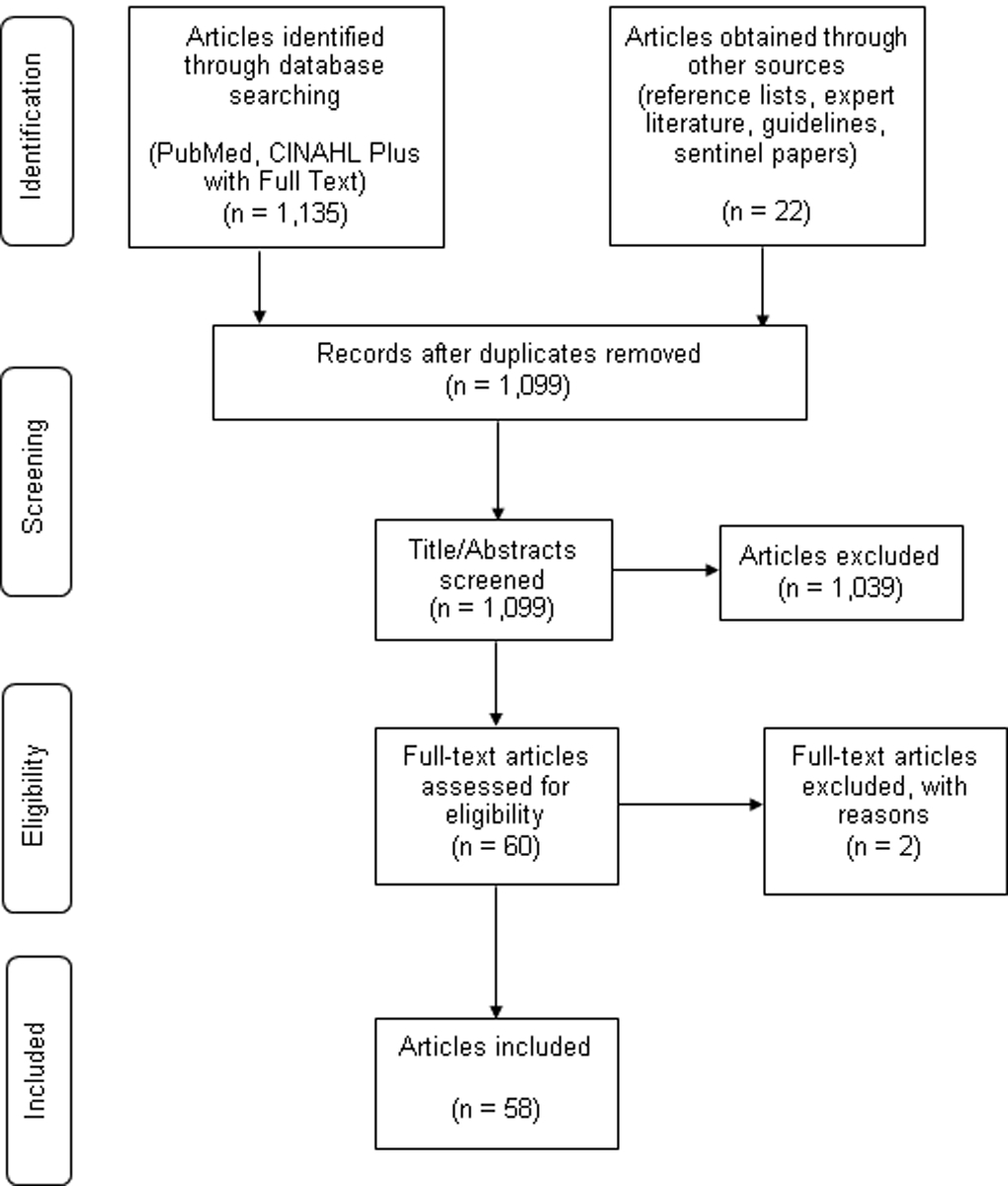

The adapted model was created by identifying factors contributing to the needs of the seriously ill adult with MCC in conjunction with the factors associated with healthcare services. Service-related factors including those specific to palliative care, patient visits and service mix, quality of care, information received, and patient experience are presented. Relevant patient and caregiver outcomes are included in the model. Finally, relevant evidence gaps and ideas for future research that appeared as common themes were derived from the articles (Table 1). In order to complete the adaptation of the model, a review of the literature was conducted to appraise existing evidence and conceptual models related to palliative care, serious illness and MCC. Articles were identified through database searching, searching reference lists, identifying expert literature, reviewing current practice guidelines, and appraising sentinel articles. Figure 4 provides a flow diagram of the literature search strategy. The literature review derived supporting evidence to adapt broader concepts proposed in the original model by Grembowski et al.24 The adapted model expanded on the original model by integrating palliative care in the conceptualization of serious illness and MCC.

Table 1.

Concepts and Associated Variables Presented in the Model and Relevant Evidence Gaps and Research Needs

| Concept and Variables | Evidence Gaps and Research Needs |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 4.

Conceptual Model Literature Review Flow Diagram

Results

Adapted Conceptual Model

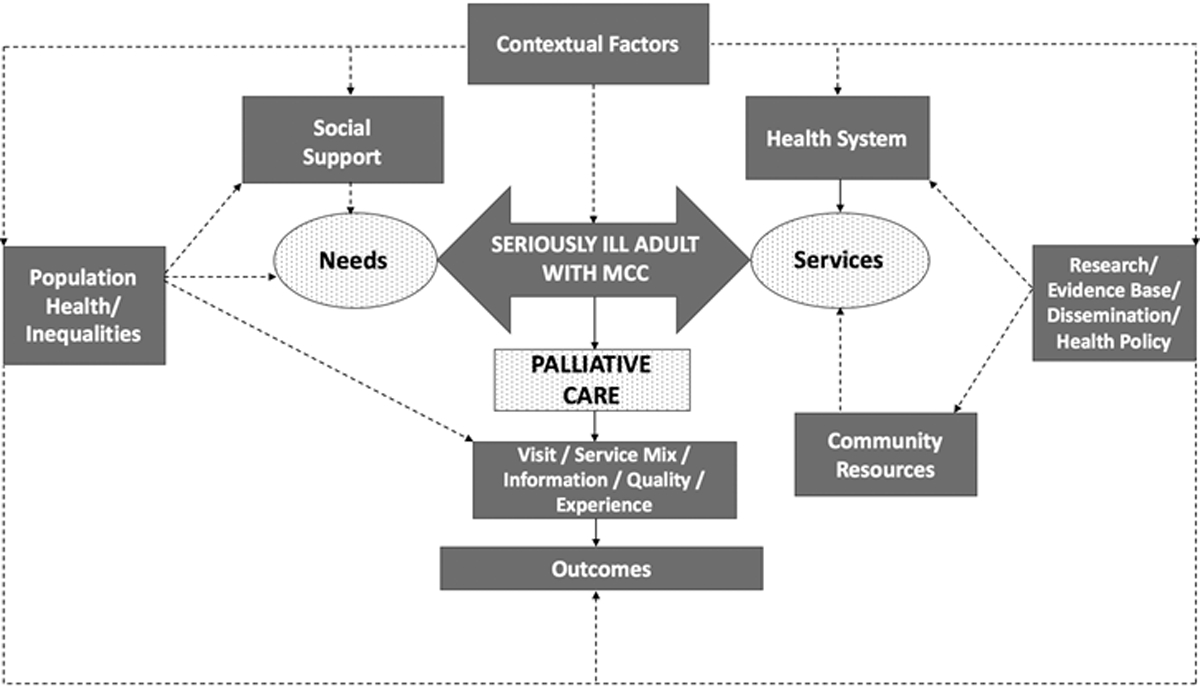

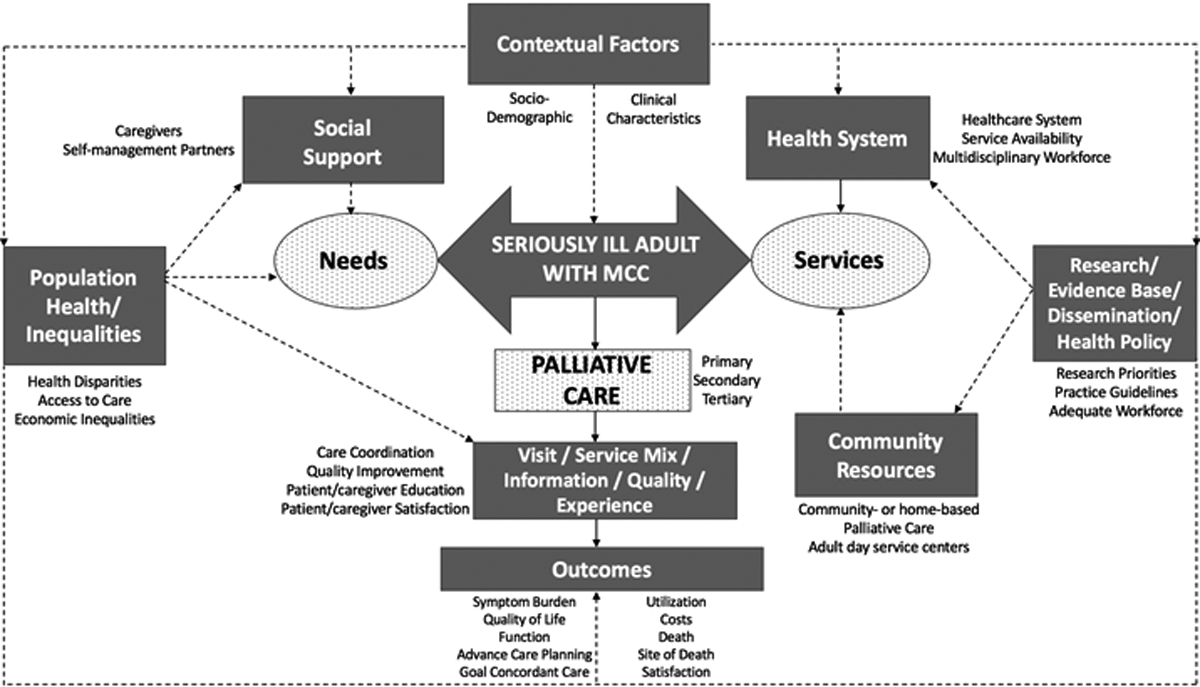

Fifty-eight articles were reviewed including existing conceptual models or frameworks, concept analyses, guidelines, and research articles presenting evidence about clinical complexity in MCC, serious illness, palliative care, and related outcomes. In the adapted model, the gap between needs and services is presented in the context of a seriously ill adult with MCC (Figure 2). Palliative care is incorporated to show the mitigating relationship between contributing factors and relevant outcomes. Contextual and person-specific factors such as sociodemographic variables, clinical characteristics, social support, and population health and inequalities are shown. The right side of the model shows the factors that affect the services received such as the health system; research, evidence base, dissemination, and health policy; and community resources. Service-related variables that contribute to clinical complexity and influence outcomes include patient visits, service mix, quality of care, patient information, experience. Relevant outcomes including symptom burden, quality of life, function, advance care planning, goal-concordant care, death, site of death, satisfaction, utilization, and cost are highlighted. To provide more detail, Figure 3 shows specific components related each concept in the adapted model.

Figure 2.

An adapted conceptual model integrating palliative care in serious illness and multiple chronic conditions (MCC) (adapted with permission from Grembowski et al.24)

Figure 3.

A detailed conceptual model featuring the conceptual mapping of the adapted model

Factors Affecting Needs of the Individual

Contextual Factors

In the original model, contextual factors that influence the needs of a complex individual consisted of economic, social or physical factors that affect the individual’s experience with healthcare.24 In the adapted model, the concepts are altered to represent factors impacting needs of the individual with serious illness and MCC as they relate to palliative care. Contextual factors that are separate from the individual include social support and social determinants of health that may influence needs and health outcomes.

Clinical Characteristics

The clinical characteristics of individual diagnoses that may intensify the experience of serious illness are critical to consider when discussing the needs of a patient with MCC. For example, the cumulative effect of symptoms of MCC can result in high symptom burden.36 An individual with advanced cancer and congestive heart failure who is receiving cancer treatment can be highly symptomatic due to pain and nausea and have complications from fluid volume overload and shortness of breath. Therefore, clinical complexity of MCC and its impact on the serious illness experience is critically important in addressing the individual’s needs.37

Sociodemographic Factors

On a sociodemographic level, the needs of the seriously ill person with MCC can be influenced by age, gender, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, level of income, and level of education.32 Sociodemographic characteristics have been shown to impact health outcomes as they can impact access to care or ability to pay for healthcare and result in disparities related to race, ethnicity, age, or gender.32,33,34,35 The adapted model accounts for goals, values or preferences of the individual.6 Social, cultural, or religious beliefs that influence the needs of a seriously ill person with MCC are also relevant.

Social Support

Social support is a key factor that moderates an individual’s level of need. Social support has been shown to be beneficial in improving outcomes such as quality of life and psychosocial well-being, and lowering risk of mortality.38 In the context of serious illness and palliative care, well-established social support can be a crucial part of the care that one receives. Caregivers are critical in alleviating the individual burden of serious illness by acting as ‘self-management partners’ who take on several roles, from supporting in treatment decision-making to aiding in self-management of having serious illness.39 Surrounding the seriously ill individual is a complex social system that either supports or impedes their health outcomes.11 This social system consists of family members, friends and colleagues, community resource persons, ethnically diverse and culturally sensitive adult day service centers, and other individuals with serious illness in the form of support groups.8,40,41 Alternatively, social isolation and lack of social support has been shown to negatively impact seriously ill adults by increasing risk of mortality, psychological and emotional distress, and clinical depression.42–44

Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health include economic and social forces that influence an individual’s overall health. The population health inequalities that arise based on ineffective social policies or unjust economic structures can influence an individual’s healthcare needs.45 Despite an increasing awareness of health disparities, substantial inequalities still exist in healthcare, especially in access to palliative care, resulting in adverse events and poor health outcomes.35,45 Economic inequalities that impact affordability of food, housing, in-home care, transportation, and resources can also greatly impact the needs of seriously ill adults with MCC.46

Factors Affecting Services Received

Contextual Factors

The adapted model incorporates contextual factors including health system, research, evidence base, dissemination, health policy, and community resources specific to palliative care, serious illness and MCC. Factors that moderate the services one might receive are related to the overall health system and its capacity to care for seriously ill adults with MCC. External factors that impact services include research priorities, available evidence and translation into clinical practice, and health policy that addresses palliative and serious illness care, such as training of healthcare workers and ensuring workforce availability.19,47

Health System

Given the rising prevalence of serious illness and MCC in the United States, the challenge of caring for this complex population must be met by the current healthcare system.15 The health system has seen an increase in the availability of palliative care services, which is available in over two-thirds of U.S. hospitals.21,48 For seriously ill individuals with MCC, a well-equipped and trained multidisciplinary workforce is imperative to provide comprehensive palliative care. Improving health outcomes such as symptom burden and quality of life are as critical as ameliorating exorbitant healthcare utilization and costs.19,21,23

Research, Evidence Base, Dissemination, & Health Policy

Research priorities for palliative care, serious illness, and MCC must be expanded. It is imperative to conduct prospective observational studies and clinical trials to study effective interventions in caring for this population.2,19 In order to support research efforts, health policy can influence prioritization of funding and legislation that seeks to improve care for this population among stakeholders at the state and national level. Health care policy can impact the availability and affordability of services that seriously ill individuals receive. For example, policy decisions can help increase focus on developing an adequate workforce to deliver care to seriously ill individuals through palliative care, like the Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training Act (PCHETA) (HR 647).47,49

Community Resources

Community resources play an integral role in supporting the seriously ill individual in self-management and can aid individuals in navigating the healthcare system.46 Community-based palliative care programs have been increasingly available for individuals who do not quality for hospice.19 In addition, community-based models that provide care for serious illness like home-based palliative care have positive associated outcomes such as improved symptom burden and quality of life, lower healthcare costs, and high patient and caregiver satisfaction.50,51

Service-Related Variables

Service-related variables are factors associated with the clinical complexity of interacting with the healthcare system with serious illness and MCC. The adapted conceptual model incorporates five service-related variables including the number of patients visits, the service mix, quality of care, information received (i.e., patient education), and the patient experience (i.e., patient and family satisfaction).

Patient Visits and Service Mix

Clinical complexity can be associated with the number of patients visits an individual may have for a multitude of ongoing chronic illnesses.24 The service mix also contributes to clinical complexity as care coordination becomes difficult. If an individual with MCC is seeing numerous providers for a variety of conditions, care coordination becomes increasingly complicated in the setting of serious illness.19

Quality of Care

An important factor of consideration when discussing services received by seriously ill individuals with MCC is the quality of care that is being provided. Of importance, there is a lack of evidence for what constitutes high quality care for those with serious illness and MCC. To ensure high-quality care, practice standards are necessary to establish and resulting care guidelines should be followed. The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care released the updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care in 2018.20,52 In order to standardize and consistently provide high quality care, the latest version of the guidelines calls on providing palliative care to all individuals with serious illness.

Patient Information

Information received by individuals with serious illness and MCC can greatly impact health outcomes. Information is largely tied to patient education, patient-provider-caregiver communication, and achieving goal-concordant or care that prioritizes the patient’s wishes.6,57,60 Serious illness communication can be used to relay prognostication and treatment options, facilitate goals of care and illness trajectory discussions, and ascertain patient or caregiver goals, values, and preferences.34

Experience

An essential service-related variable is the patient experience. The inclusion of patient and caregiver experience in the adapted conceptual model is key because one of the goals of palliative care is to improve patient and caregiver satisfaction. Aligning care with the patient’s priorities and goals are crucial in palliative care.4,18 Given that clinical complexity greatly impacts one’s experience within the healthcare system, measuring patient and caregiver satisfaction is necessary for ongoing quality improvement initiatives.

Outcomes

In the original model, Grembowski et al.24 outlined health outcomes to consider after accounting for clinical complexity in caring for adults with MCC such as function, well-being, and iatrogenic effects. In this adapted model, after incorporating palliative care and the clinical complexity of having serious illness and MCC, several outcomes were brought to the forefront. The outcomes that are relevant to palliative care, serious illness and MCC consist of symptom burden, quality of life, function, advance care planning, goal-concordant care, utilization, costs, death, site of death, and satisfaction. Palliative care studies in seriously ill patients have shown positive outcomes associated with symptom burden, quality of life, advance care planning, lowered utilization and cost, as well as high patient and caregiver satisfaction.22,50,53–55 For example, Bakitas and colleagues53 conducted a randomized controlled trial of 322 patients with advanced cancer to examine the effect of a palliative care intervention (Project ENABLE) on quality of life, symptom intensity, mood and resource utilization. The intervention was administered via telephone by advanced practice nurses and involved an educational case management approach to support patient self-management and empowerment. The results were improved quality of life, reduced symptom intensity and depressed mood in the intervention group. Similarly, palliative care provided in the home setting, or home-based palliative care, can improve quality of life and symptom burden and decrease health care utilization and costs in the cancer population.55,56 A Cochrane systematic review of the effectiveness of home-based palliative care in adults with serious illness and their caregivers revealed that it is cost-effective and results in more deaths occurring outside of the hospital setting.50

Kavalieratos and colleagues22 identified the patient and caregiver outcomes associated with palliative care in a systematic review and meta-analysis. In this study, several outcomes and measures including quality of life, symptom burden, site of death, satisfaction, resource utilization, and health care expenditures were examined in 43 randomized controlled trials. The meta-analysis revealed that palliative care was significantly associated with improvements in quality of life at 1- to 3-month follow up and remained significant after sensitivity analyses were conducted using studies with low risk of bias. While the study found a statistically significant relationship between palliative care and symptom burden; after adjusting for varying types of bias, the relationship was not significant. Palliative care was shown to be associated with improved advance care planning, greater patient and caregiver satisfaction, and decreased healthcare utilization. In terms of costs and survival, the evidence showed mixed results. Portz et al.36 examined baseline data from a statin discontinuation clinical trial to explore the relationship between multimorbidity, symptom burden, and functional status among seriously ill patients and found that MCC was associated with lower functional status. Finally, there is a compelling case for including goal-concordant care as another outcome of palliative care as effective communication between the patient and provider will result in care that aligns with the patient’s goals.6 The adapted model illuminates the relationships between palliative care and associated outcomes, which have been shown to alleviate the impact of serious illness through improved symptom burden, quality of life, and decreased healthcare utilization.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this adapted model is the first to integrate palliative care in the conceptualization of serious illness and MCC. The adapted model has potential to guide the development of conceptually sound research studies that seek to address care challenges involving seriously ill adults and MCC. The adapted model differs from the original model by Grembowski et al.24 in that it includes palliative care and places special emphasis on serious illness in the setting of MCC. There are also palliative care specific outcomes included in the adapted model, which also differentiates this adapted model from the original model. The adapted model was intended to guide research that seeks to improve the outcomes of serious illness and MCC through the conceptual integration of palliative care. There is potential for the model to be used in clinical practice; however, the adapted model has not been tested empirically. A major shortfall of the model is that it may not account for every aspect of palliative care and it does not specific the type of palliative care delivered nor does it account for the key interdisciplinary workforce that is involved. Furthermore, the concepts, factors, and relationships presented in the model would have to be tested in smaller studies. Testing of the model would require multiple phases in order to ensure feasibility.

Given the rising prevalence of MCC and additional burden of serious illness, about a half of the visits to subspecialty clinics in the United States are attributed to MCC.15 Because seriously ill adults with MCC have greater complex care needs, they often face ineffective and fragmented care across the healthcare spectrum with a multitude of providers, which has potential to negatively impact quality of life.4,13,16–18 This core issue of clinical complexity, which was the impetus for the creation of this model, must be further examined. The primary goal of the adapted model is to provide a comprehensive conceptualization of all of the key concepts associated with palliative care, serious illness and MCC. While every attempt was made to provide a comprehensive model, it is possible that important components are missing. The review of the literature that informed the development of the adapted model uncovered fundamental gaps in the literature. The major gaps in the evidence and suggestions for future research are delineated in Table 1.

To effectively research seriously ill adults with MCC, the contextual factors that impact the individual’s needs must be acknowledged and outside of the individual, societal factors influence needs such as social support, social determinants of health, and population health or inequalities should also be considered. Given the clinical complexity of serious illness, especially in the context of MCC, this conceptual model can aid researchers in developing research questions to address the care needs of those with serious illness and MCC.

Conclusion

While palliative care has made great strides in improving serious illness care, broadening its scope across a variety of settings is needed.2 More prospective, observational studies and randomized clinical trials will be necessary to garner empirical evidence upon which to develop targeted palliative care approaches for seriously ill adults with MCC. Further examining outcomes of palliative care in large clinical trials is necessary to fill in evidence gaps. While conceptual models can be useful in guiding research, it is important to remember that they do not encompass every relevant defining concept associated with serious illness, palliative care, and MCC as each individual is unique. Therefore, the adapted model is limited in that it cannot account for every possible defining aspect of the serious illness or MCC. Nonetheless, the adapted conceptual model presented in this paper centers the seriously ill individual with MCC at the nexus of its model for this very reason, that each of the unique individual-, societal-, and system-level factors that make up the clinical complexity of the person can and should be considered. We hope that the adapted conceptual model provides researchers with a comprehensive model from which to develop research studies that seek to inform care for seriously ill adults with MCC. Ensuring comprehensive, high-quality care that improves quality of life of seriously ill individuals with MCC is vitally important in palliative care and using an evidence-driven model to guide research in essential in providing conceptual clarity.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing P20 Center for Precision Health in Diverse Populations (P20NR018075) and the NYU Clinical and Translational Science Institute for their contributions in the development of this manuscript. They would also like to acknowledge support received from the Jonas Philanthropies (Jonas Scholar). Finally, they would like to thank Grembowski et al.24 for the permission to use and adapt Figure 1 via RightsLink.

Funding

This research is supported in part by an NYU CTSA grant (NCATS/NIH: UL1 TR001445, TL1 TR001447).

Contributor Information

Komal P. Murali, NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing.

John D. Merriman, NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing.

Gary Yu, NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing.

Allison Vorderstrasse, Florence S. Downs PhD Program in Nursing Research and Theory, NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing.

Amy Kelley, Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Abraham A. Brody, Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing.

References

- 1.National Quality Forum. Multiple chronic conditions measurement framework. Accessed Nov 10, 2019 https://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/Multiple_Chronic_Conditions_Measurement_Framework.aspx. Updated 2012.

- 2.Ritchie CS, Zulman DM. Research priorities in geriatric palliative care: Multimorbidity. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(8):843–847. Accessed Dec 7, 2018. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd C, Smith CD, Masoudi FA, et al. Decision making for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: Executive summary for the american geriatrics society guiding principles on the care of older adults with multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):665–673. Accessed Nov 18, 2019. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaum CS, Rosen J, Naik AD, et al. Patient‐Centered care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A stepwise approach from the American Geriatrics Society. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(10):1957–1968. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04187.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley AS, Morrison RS, Wenger NS, Ettner SL, Sarkisian CA. Determinants of treatment intensity for patients with serious illness: A new conceptual framework. Journal of palliative medicine. 2010;13(7):807–813. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20636149. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA. Achieving goal-concordant care: A conceptual model and approach to measuring serious illness communication and its impact. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2018;21(S2):S–27. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/jpm.2017.0459. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruera E, Hui D. Conceptual models for integrating palliative care at cancer centers. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2012;15(11):1261–1269. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/jpm.2012.0147. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gazaway S, Stewart M, Schumacher A. Integrating palliative care into the chronic illness continuum: A conceptual model for minority populations. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities. 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31250371. doi: 10.1007/s40615-019-00610-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam DY, Scherer JS, Brown M, Grubbs V, Schell JO. A conceptual framework of palliative care across the continuum of advanced kidney disease. CJASN. 2019;14(4):635–641. Accessed Oct 11, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philip J, Crawford G, Brand C, et al. A conceptual model: Redesigning how we provide palliative care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliative & supportive care. 2018;16(4):452–460. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28560949. doi: 10.1017/S147895151700044X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodiamont F, Jünger S, Leidl R, Maier BO, Schildmann E, Bausewein C. Understanding complexity - the palliative care situation as a complex adaptive system. BMC health services research. 2019;19(1):157 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30866912. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-3961-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelley AS. Defining “serious illness”. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(9):985 Accessed Nov 18, 2019. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelley AS, Covinsky KE, Gorges RJ, et al. Identifying older adults with serious illness: A critical step toward improving the value of health care. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(1):113–131. Accessed Nov 20, 2019. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelley AS, Bollens-Lund E. Identifying the population with serious illness: The “denominator” challenge. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S2):S7–S16. Accessed Oct 9, 2019. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudley N, Lee SJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Ritchie CS. Prevalence of multimorbidity among older adults with advanced illness visits to U.S. subspecialty clinics. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(1):e4–e6. Accessed Dec 17, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frandsen BR, Joynt KE, Rebitzer JB, Jha AK. Care fragmentation, quality, and costs among chronically ill patients. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(5):355–362. Accessed Oct 5, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition--multimorbidity. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2493–2494. Accessed Nov 18, 2019. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tinetti ME, Esterson J, Ferris R, Posner P, Blaum CS. Patient priority-directed decision making and care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(2):261–275. Accessed Nov 18, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(8):747–755. 10.1056/NEJMra1404684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. (2018). Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th edition. Accessed Nov 18, 2019 https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Hughes MT, Smith TJ. The growth of palliative care in the united states. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:459–475. Accessed Oct 17, 2019. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2104–2114. Accessed Dec 7, 2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parekh AK, Goodman RA, Gordon C, Koh HK. Managing multiple chronic conditions: A strategic framework for improving health outcomes and quality of life. Public health reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974). 2011;126(4):460–471. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21800741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grembowski D, Schaefer J, Johnson K, et al. A conceptual model of the role of complexity in the care of patients with multiple chronic conditions. Medical Care. 2014;52 Suppl 3 Suppl 2, ADVANCING THE FIELD: Results from the AHRQ Multiple Chronic Conditions Research Network(3):S7-S14. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&NEWS=n&CSC=Y&PAGE=fulltext&D=ovft&AN=00005650-201403001-00005. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ismail-Beigi F, Moghissi E, Tiktin M, Hirsch IB, Inzucchi SE, Genuth S. Individualizing glycemic targets in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Implications of recent clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(8):554–559. Accessed Oct 11, 2019. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-8-201104190-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patrick DL. Finding health-related quality of life outcomes sensitive to health-care organization and delivery. Med Care. 1997;35(11 Suppl):NS49–57. Accessed Oct 11, 2019. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199711001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):725–731. Accessed Oct 11, 2019. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Safford M, Allison J, Kiefe C. Patient complexity: More than comorbidity. the vector model of complexity. J GEN INTERN MED. 2007;22(S3):382–390. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18026806. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shippee ND, Shah ND, May CR, Mair FS, Montori VM. Cumulative complexity: A functional, patient-centered model of patient complexity can improve research and practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(10):1041–1051. Accessed Oct 11, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):2–4. Accessed Oct 11, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59–65. Accessed Oct 8, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendieta M, Miller A. Sociodemographic characteristics and lengths of stay associated with acute palliative care: A 10-year national perspective. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(12):1512–1517. Accessed Oct 14, 2019. doi: 10.1177/1049909118786409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 2):19–31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3863696/. Accessed Oct 14, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh S, Evans N, Williams M, Sezginis N, Baryeh NAK. Influences of socio-demographic factors and health utilization factors on patient-centered provider communication. Health Commun. 2018;33(7):917–923. Accessed Oct 14, 2019. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1322481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2013;16(11):1329–1334. http://www.liebertonline.com/doi/abs/10.1089/jpm.2013.9468. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portz JD, Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Ritchie CS. High symptom burden and low functional status in the setting of multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(10):2285–2289. Accessed Dec 8, 2018. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gómez-Batiste X, Murray S, Thomas K, et al. Comprehensive and integrated palliative care for people with advanced chronic conditions: An update from several european initiatives and recommendations for policy. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2016;53(3):509–517. https://www.clinicalkey.es/playcontent/1-s2.0-S0885392416312039. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reblin M, Uchino B. Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2008;21(2):201–205. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&NEWS=n&CSC=Y&PAGE=fulltext&D=ovft&AN=00001504-200803000-00021. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f3ad89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulman-Green D, Brody A, Gilbertson-White S, Whittemore R, McCorkle R. Supporting self-management in palliative care throughout the cancer care trajectory. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care. 2018;12(3):299–307. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30036215. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hudson P A conceptual model and key variables for guiding supportive interventions for family caregivers of people receiving palliative care. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2003;1(4):353–365. http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1478951503030426. doi: 10.1017/S1478951503030426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sadarangani TR, Murali KP. Service use, participation, experiences, and outcomes among older adult immigrants in american adult day service centers: An integrative review of the literature. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2018;11(6):317–328. Accessed Oct 15, 2019. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20180629-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dimond M Social support and adaptation to chronic illness: The case of maintenance hemodialysis. Res Nurs Health. 1979;2(3):101–108. Accessed Oct 15, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ell K Social networks, social support and coping with serious illness: The family connection. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42(2):173–183. Accessed Oct 15, 2019. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gallant MP. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: A review and directions for research. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30(2):170–195. Accessed Oct 15, 2019. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arcaya MC, Arcaya AL, Subramanian SV. Inequalities in health: Definitions, concepts, and theories. Global Health Action. 2015;8(1):27106 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3402/gha.v8.27106. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.27106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohn J, Corrigan J, Lynn J, et al. Community-based models of care delivery for people with serious illness. NAM Perspectives. 2017. https://nam.edu/community-based-models-of-care-delivery-for-people-with-serious-illness/. Accessed Oct 18, 2019. doi: 10.31478/201704b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamal AH, Bull JH, Swetz KM, Wolf SP, Shanafelt TD, Myers ER. Future of the palliative care workforce: Preview to an impending crisis. American Journal of Medicine, The. 2016;130(2):113–114. https://www.clinicalkey.es/playcontent/1-s2.0-S0002934316309627. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, Lettang K, Meier DE, Morrison RS. The growth of palliative care in U.S. hospitals: A status report. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(1):8–15. Accessed Oct 3, 2018. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Center for the Advancement of Palliative Care (CAPC). (2019). Key Palliative Care Bill Reintroduced in the House. Accessed Nov 18, 2019 https://www.capc.org/blog/news-bites-key-palliative-care-bill-reintroduced-in-the-house/

- 50.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(6):CD007760 Accessed Mar 21, 2017. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007760.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yosick L, Crook RE, Gatto M, et al. Effects of a population health community-based palliative care program on cost and utilization. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(9):1075–1081. Accessed Oct 18, 2019. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meier DE, Twaddle M, Melnick A, Ferrell B Accountability for quality in the care of people living with A serious illness: The national consensus project clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, 4th edition | health affairs. Health Affairs Blog, November 30, 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20181129.33562/full/. Accessed November 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741–749. Accessed Dec 7, 2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1438–1445. Accessed Apr 10, 2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. Journal of palliative medicine. 2003;6(5):715–724. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14622451. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of In‐Home palliative care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55(7):993–1000. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blaum CS, Rosen J, Naik AD, et al. Feasibility of implementing patient priorities care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2018;66(10):2009–2016. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jgs.15465. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nevin M, Smith V, Hynes G. Non-specialist palliative care: A principle-based concept analysis. Palliative Medicine. 2019;33(6):634–649. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0269216319840963. doi: 10.1177/0269216319840963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sawatzky R, Porterfield P, Lee J, et al. Conceptual foundations of a palliative approach: A knowledge synthesis. BMC palliative care. 2016;15(1):5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26772180. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0076-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of patient Priorities–Aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2019. https://search.proquest.com/docview/2301880866. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Buttorff C, Ruder T, & Bauman M (2017). Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. Accessed Mar 18, 2020 https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/tools/TL200/TL221/RAND_TL221.pdf