Abstract

Infection with a single influenza A virus (IAV) is only rarely sufficient to initiate productive infection. Instead, multiple viral genomes are often required within a given cell. Here, we show that IAV reliance on multiple infection can form an important species barrier. Namely, we find that avian H9N2 viruses representative of those circulating widely at the poultry-human interface exhibit acute dependence on collective interactions in mammalian systems. This need for multiple infection is greatly reduced in the natural host. Quantification of incomplete viral genomes showed that their complementation accounts for the moderate reliance on multiple infection seen in avian cells, but not the added reliance seen in mammalian cells. In mammals, an additional form of virus-virus interaction is needed. We find that the PA gene segment is a major driver of this phenotype and that both viral replication and transcription are affected. These data indicate that multiple distinct mechanisms underlie IAV reliance on multiple infection and underscore the importance of virus-virus interactions in IAV infection, evolution and emergence.

Classically, an infectious unit has been defined as a single virus particle which delivers its genome to a cell, initiates the viral reproductive program, and yields progeny viruses. Recently, however, the importance of collective interactions among viruses is being increasingly recognized1–3. The delivery of multiple viral genomes to a cell allows antagonistic and beneficial interactions which have the potential to shape transmission, pathogenicity and evolution.

In the case of IAV, several lines of evidence point to a major role in infection for complementation between genomes lacking one or more functional segments4–8. Conversely, deleteriously mutated genes act in a dominant negative fashion, suppressing production of infectious progeny9–11. Importantly, multiple infection with identical viral genomes can also alter infection outcomes8,12–14 and may be particularly relevant for facilitating viral growth under adverse conditions, such as antiviral drug treatment3,15. For IAV, an important adverse condition to consider is that of a novel host environment. IAVs occupy a broad host range16,17, but host barriers to infection typically confine a given lineage to one or a small number of related species18,19. Spillovers occur occasionally, however. When a novel IAV lineage is established in humans, the result is a pandemic of major public health consequence20,21.

Here, we examined the multiplicity dependence of human and avian-origin viruses in different host systems and found that the extent to which viral progeny production is concentrated within multiply-infected cells varies greatly with virus-host context. Our data point to an important role for collective interactions in determining the potential for IAV replication in diverse hosts.

Results

Multiplicity dependence varies with strain and cell type

To evaluate the extent to which IAV relies on multiple infection for productive infection, we initially used reassortment and coinfection as readouts. While singly-infected cells yield only parental progeny, reassortment is highly efficient within coinfected cells22. Monitoring reassortment therefore indicates the proportion of progeny in a bulk virus population that were produced from multiply-infected cells. Coinfections were performed under single-cycle conditions with homologous viruses that differ only by a silent mutation in each segment and the presence of either an HA or HIS epitope tag. The silent mutations allow identification of reassortant viruses. The epitope tags enable quantification of cellular coinfection. Homologous coinfection partners, termed WT and VAR, were generated in A/Netherlands/602/2009 (H1N1) (NL09), A/mallard/199106/99 (H3N8) (MaMN99) and A/guinea fowl/HK/WF10/99 (GFHK99) backgrounds.

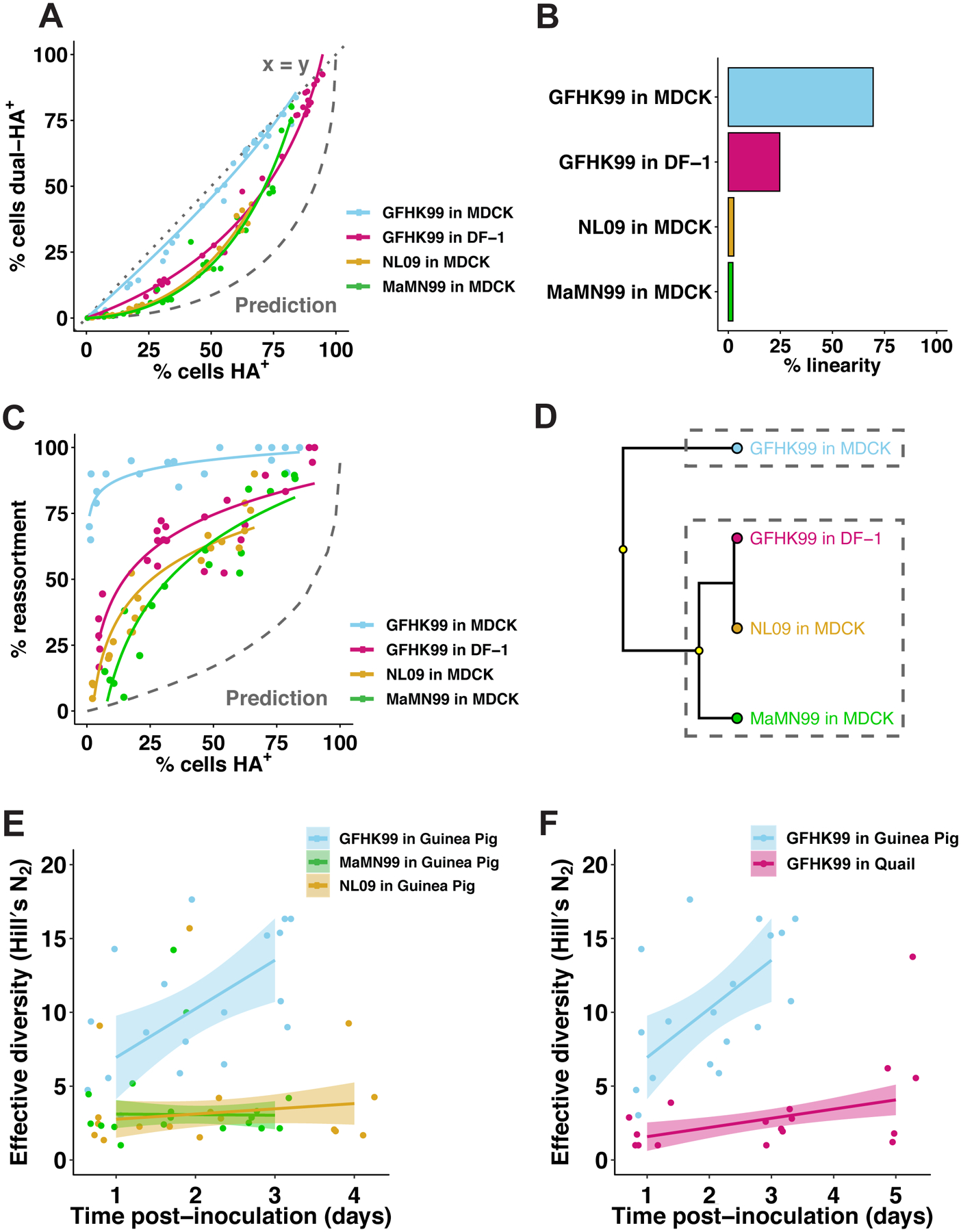

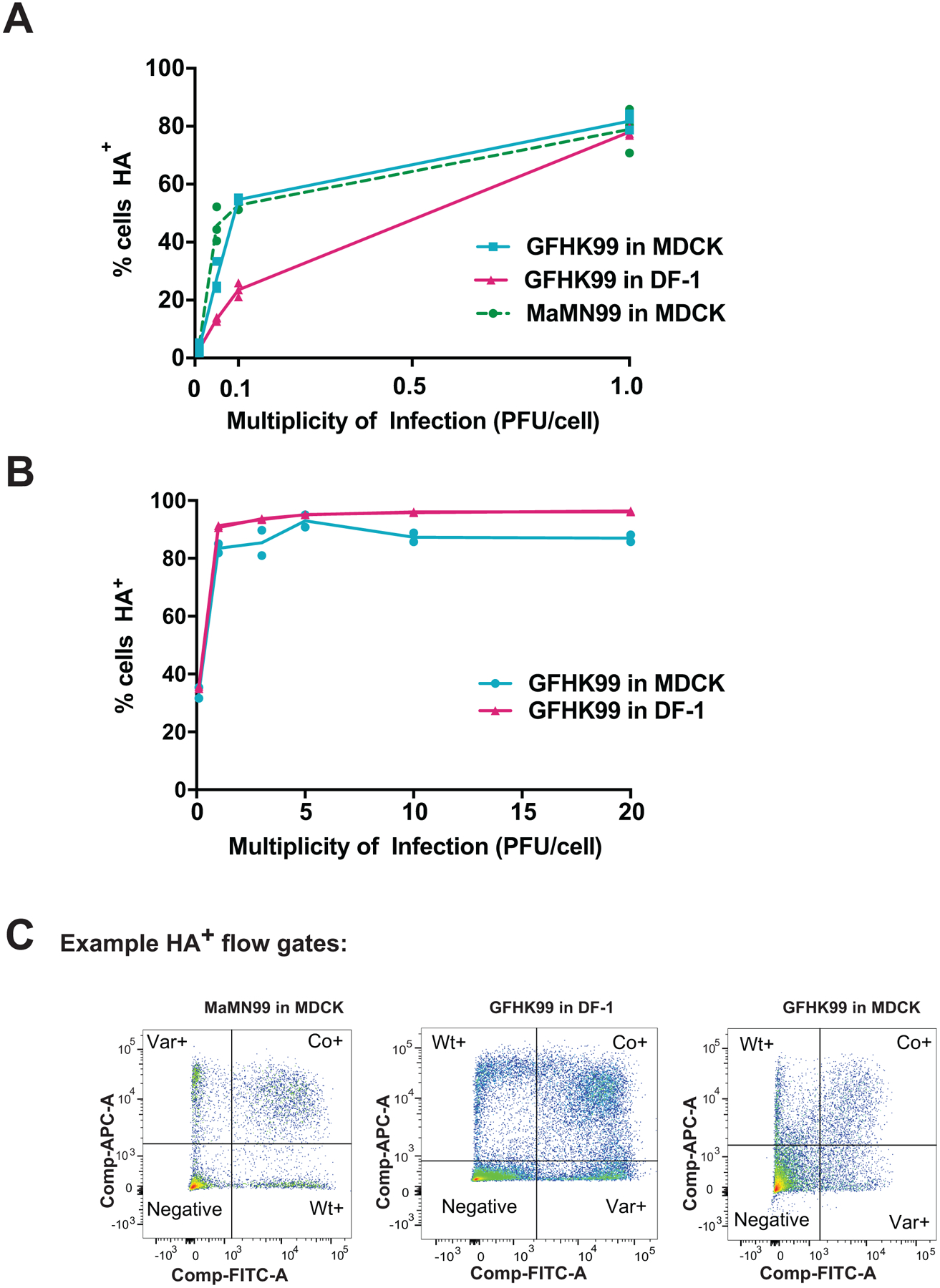

Coinfection and reassortment were examined in canine MDCK and chicken DF-1 cells (Figure 1). In MDCK cells, GFHK99 viruses showed a near linear relationship between total HA+ cells and dual-HA+ cells, suggesting a strict dependence on multiple infection for HA expression (Figure 1A). By contrast, HA expression resulting from infection with a single strain was more common for GFHK99 in DF-1 cells, MaMN99 in MDCK cells and NL09 in MDCK cells (Figure 1A). The more dependent expression of any HA protein is on coinfection, the more linear the relationship between dual-HA+ cells and HA+ cells becomes. Conversely, a relationship closer to the Poisson expectation indicates less dependence on coinfection. Among the viruses tested, we found that only GFHK99 virus in MDCK cells exhibits strong linearity (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Coinfection and reassortment frequencies indicate that IAV multiplicity dependence varies with virus strain and host species.

A–D) MDCK or DF-1 cells were coinfected with homologous WT and VAR viruses of either GFHK99, MaMN99, or NL09 strain backgrounds at MOIs ranging from 10 to 0.01 PFU/cell. The relationship between % cells HA+ and % cells dual-HA+ (A) varies with strain and cell type, resulting in curves of differing % linearity (B). GFHK99, MaMN99, and NL09 viruses exhibit different reassortment levels in MDCK cells, but all show high reassortment relative to a theoretical prediction in which singly infected and multiply infected cells have equivalent burst sizes (C). GFHK99 virus reassortment levels differ in MDCK and DF-1 cells, but again reassortment in DF-1 cells remains high relative to the theoretical prediction in which multiple infection confers no advantage (C). Clustering analysis of reassortment and HA co-expression regression models determines that GFHK99 virus exhibits unique behavior in MDCK cells compared to DF-1 cells or other viruses in MDCK cells (D). Yellow circles indicate nodes with >95% bootstrap support. Panels (E) and (F) show results of WT/VAR coinfections performed in vivo. Because multicycle replication in vivo allows the propagation of reassortants, analysis of genotypic diversity rather than percent reassortment is more informative for these experiments. Thus, the effective diversity was calculated for each dataset and plotted as a function of time post-inoculation. In guinea pigs (n=6), GFHK99 WT and VAR1 viruses exhibit higher reassortment than MaMN99 or NL09 WT and VAR viruses, as indicated by increased genotypic diversity (E). The GFHK99 WT and VAR1 viruses exhibit higher reassortment in guinea pigs than in quail (n=5) (F). Guinea pig data shown in panels E and F are the same. NL09 virus reassortment data shown in (C) were reported previously57. Lines and shading represent prediction mean and 95% prediction interval (mean ± 1.96 * standard error) of robust linear regression.

In line with observed levels of coinfection, GFHK99 virus exhibits high reassortment in MDCK cells, indicating that nearly all progeny virus is produced from WT-VAR coinfected cells (Figure 1C). MaMN99 or NL09 viruses infecting MDCK cells show lower reassortment. Moreover, GFHK99 reassortment is markedly reduced in DF-1 compared to MDCK cells (Figure 1C). These results clearly implicate virus-host interactions in determining multiplicity dependence.

That all virus-cell pairings tested show multiplicity dependence is highlighted by comparison of the experimental reassortment data to a theoretical prediction7 (Figure 1C). This prediction is derived from a model in which singly- and multiply-infected cells make equivalent numbers of progeny. Reassortment is therefore predicted to increase only gradually at low levels of infection where coinfection is rare. The experimental observation that reassortment rapidly reaches high levels indicates that viral progeny production is enriched in the proportion of the infected cell population that is multiply infected.

Frequent reassortment and the linear relationship between overall HA expression and HA co-expression provide two measures of multiplicity dependence. To summarize these two measures and analyze the relationships between the virus-cell pairings tested, we conducted a hierarchical clustering analysis using the parameters of the regression models shown in Figure 1A and 1C. MaMN99 and NL09 viruses in MDCK cells, and GFHK99 virus in DF-1 cells, represent one cluster, while GFHK99 virus in MDCK cells partitioned into its own cluster (Figure 1D). Although evident in all virus-cell pairings, multiple-infection dependence is particularly strong for GFHK99 virus in MDCK cells.

Strain- and host-specific phenotypes are evident in vivo

To determine whether host-dependent reliance on multiple infection extended to in vivo models, we performed coinfections in guinea pigs and quail. GFHK99, MaMN99, and NL09 viruses were tested in guinea pigs and GFHK99 virus in quail. To ensure use of comparable effective doses for each virus/host pairing, 50% infectious dose (ID50) was determined. Guinea pigs were then infected with 102 GPID50 and quail were infected with 102 QID50. To evaluate the frequency of reassortment, plaque isolates from upper respiratory samples were genotyped for each animal on each day. The viruses collected from GFHK99-infected guinea pigs show much higher genotypic diversity throughout the course of infection than viruses isolated from MaMN99- or NL09-infected guinea pigs (Figure 1E) or GFHK99-infected quail (Figure 1F). These data indicate that the virus-host interactions which determine dependence on multiple infection in cell culture extend to in vivo infection.

Multiple infection enhances viral growth

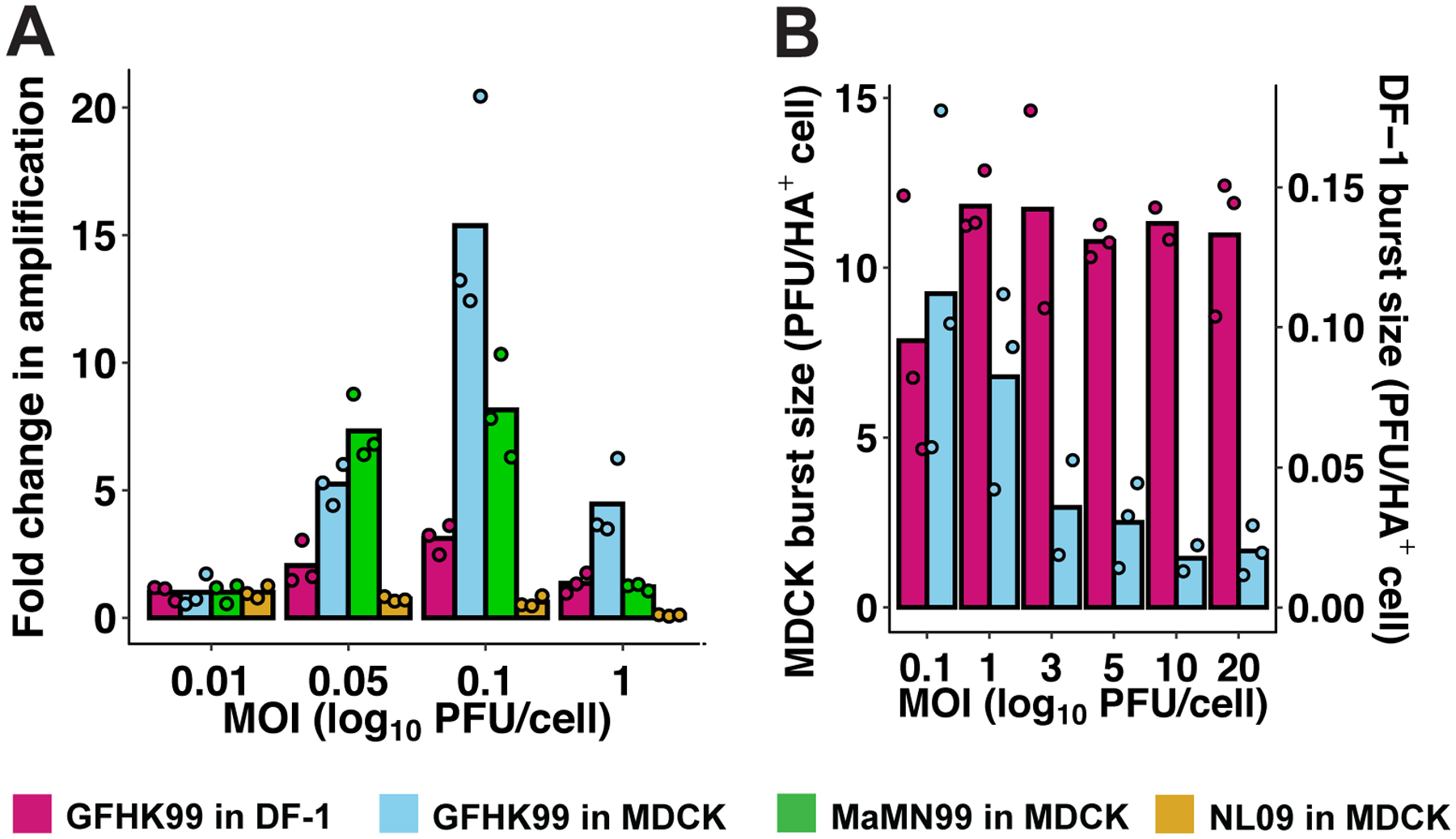

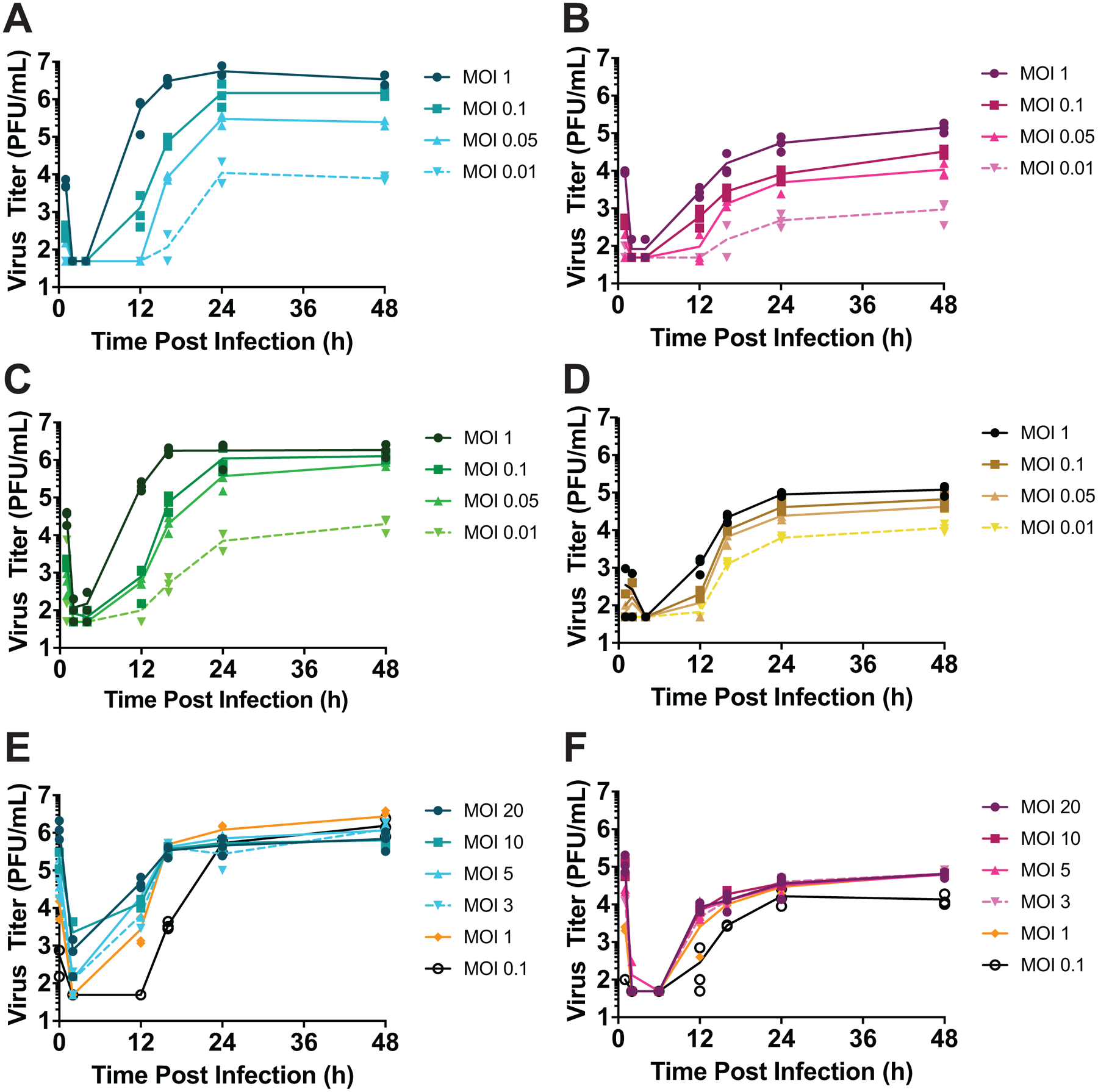

Our reassortment analyses suggest that increased multiplicity augments viral output. As a direct test of this, we infected over a range of MOIs and then measured PFU produced per cell under single-cycle conditions. Input MOIs of less than 1 PFU per cell were found to be non-saturating by flow cytometry in MDCK and DF-1 cells (Extended Data Figure 1). Under these non-saturating conditions, increasing MOI resulted in accelerated growth and higher yield for all virus/cell pairings tested (Extended Data Figure 2A–D). Enhancement of viral amplification was, however, greatest for GFHK99 virus in MDCK cells (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Increasing MOI increases viral productivity at sub-saturating, but not saturating MOIs.

MDCK or DF-1 cells were infected under single-cycle conditions at a range of MOIs with the viruses indicated, and released virus was sampled over the course of 24 h. A) Fold change in amplification (maximum PFU output / PFU input) relative to the MOI=0.01 PFU per cell condition is plotted for each virus-cell pairing. B) Burst size, calculated as maximum PFU output / number of HA+ cells detected by flow cytometry, is plotted for each virus-cell pairing tested in the higher MOI range. MOIs shown are in units of PFU per cell, as determined in MDCK cells. Data are shown from n=3 replicate cell cultures per condition; bars show the mean.

We reasoned that the cooperative effect observed might result from i) complementation of incomplete viral genomes or ii) a benefit of increased viral genome copy number per cell. In an effort to differentiate between these possibilities, we measured growth of GFHK99 virus in MDCK and DF-1 cells infected over a range of saturating MOIs (Extended Data Figure 1). Here, incomplete viral genomes are unlikely to be prevalent and any benefit of increasing MOI would be attributable to increased genome copies per cell. In DF-1 cells, burst size is constant over an MOI range of 1 to 20 PFU per cell, while in MDCK cells, burst size declines about 4-fold, indicative of an antagonistic interaction (Figure 2B and Extended Data Figure 2E, F). Thus, increasing levels of multiple infection was found to be beneficial at lower MOIs but either neutral or detrimental to viral productivity once saturating levels of infection were achieved. Whether this threshold effect is imposed by a need for complementation or another mechanism sensitive to saturation remained unclear.

Multiple infection enhances viral RNA replication

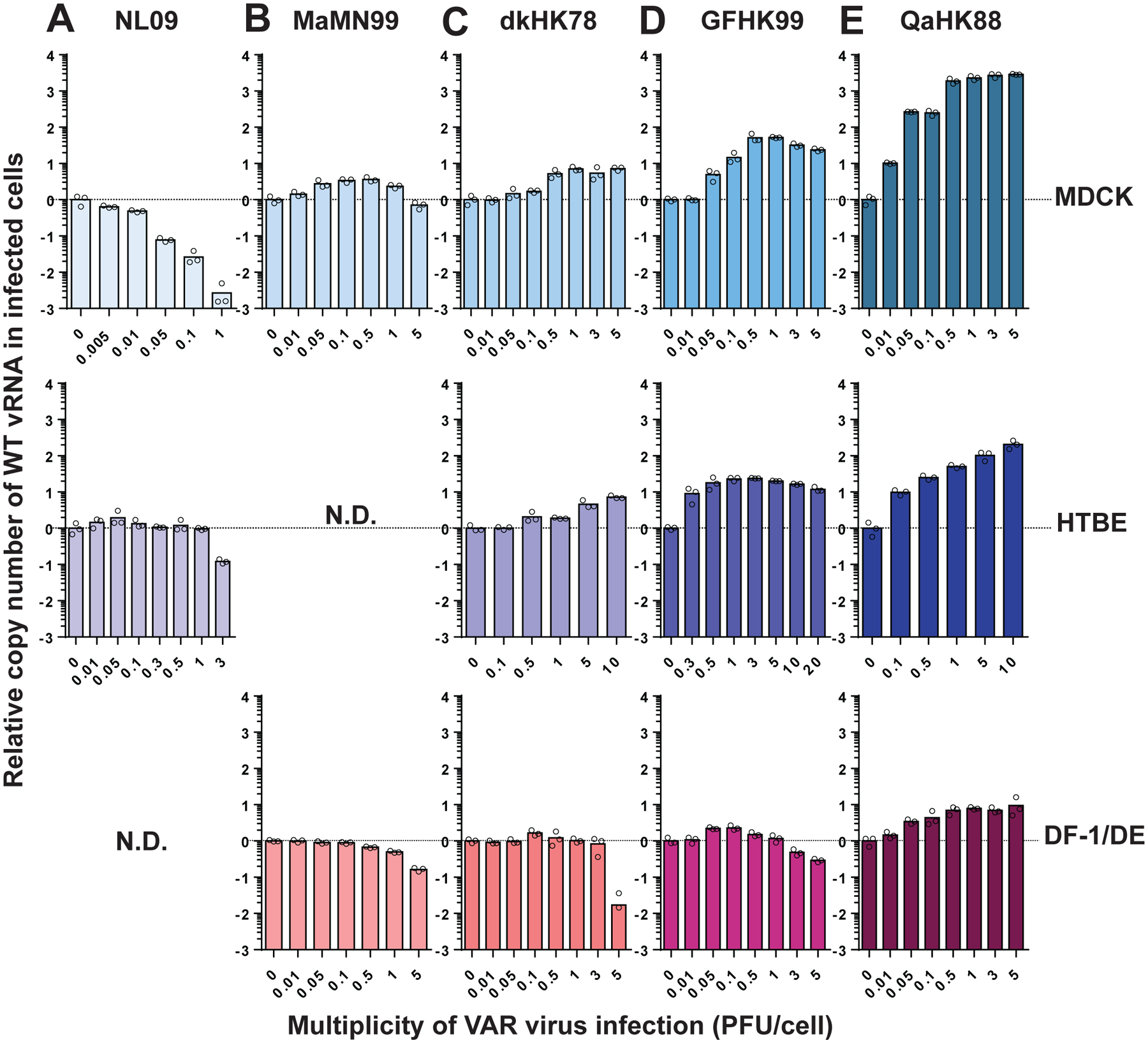

To evaluate the impact of multiple infection on genome replication, we measured WT viral RNA synthesis in the absence and presence of increasing amounts of homologous coinfecting virus. We also broadened the panel of viruses examined to include A/duck/HK/448/78 (H9N2) (DkHK78), a wild bird isolate that predates the establishment of H9N2 viruses in poultry, and A/quail/HK/88 (H9N2) (Qa/HK/88), an early isolate of the H9N2 poultry lineage23. Mammalian or avian cells were infected at low MOI with WT virus to ensure receipt of a single WT virus genome and, concurrently, with increasing doses of VAR virus. Replication of WT genomes was then quantified using primer/probe sets that do not detect VAR templates.

The results for NL09 and MaMN99 viruses show little to no increase in WT vRNA production with VAR virus addition, in all cell types tested (Figure 3A and B). DkHK78 virus exhibits an intermediate phenotype, with 7-fold enhancement in mammalian cells and 1.6-fold enhancement in avian cells (Figure 3C). GFHK99 and QaHK88 viruses show much stronger increases of WT vRNA replication with coinfection: in MDCK and NHBE cells, respectively, GFHK99 virus shows increases of 60-fold and 20-fold, while QaHK88 virus shows increases of >2000-fold and 200-fold. In contrast, these two poultry isolates show markedly less enhancement in avian DF-1 cells (Figure 3D and E). Of note, addition of VAR at high doses suppresses WT vRNA production in several virus/cell pairings, likely indicating competition for limited resources in the cell. This antagonistic interaction is stronger in systems where little benefit of coinfection is detected.

Figure 3. Coinfection enhances GFHK99 vRNA synthesis in a dose and host dependent manner.

Cells were coinfected with WT virus and increasing doses of VAR virus. WT virus MOI was 0.05 PFU per cell in NHBE cells and 0.005 PFU per cell in all other cell types. The fold change in WT vRNA copy number, relative to that detected in the VAR virus, is plotted for NL09 virus in MDCK and NHBE cells (A), MaMN99 virus in MDCK and duck embryo (DE) cells (B), dkHK78 virus in MDCK, NHBE, and DF-1 cells (C), GFHK99 virus in MDCK, NHBE, and DF-1 cells (D) and QaHK88 virus in MDCK, NHBE, and DF-1 cells (E). Bars represent the mean of n=3 cell cultures per condition.

In summary, for GFHK99 and QaHK88 viruses, the introduction of coinfecting virus reveals a cooperative effect acting at the level of RNA synthesis, which is particularly potent in mammalian cells. That the replication of NL09 and MaMN99 viruses is not detectably enhanced by the addition of VAR virus suggests reduced reliance on multiple infection, consistent with reassortment and dual-HA positivity data presented above.

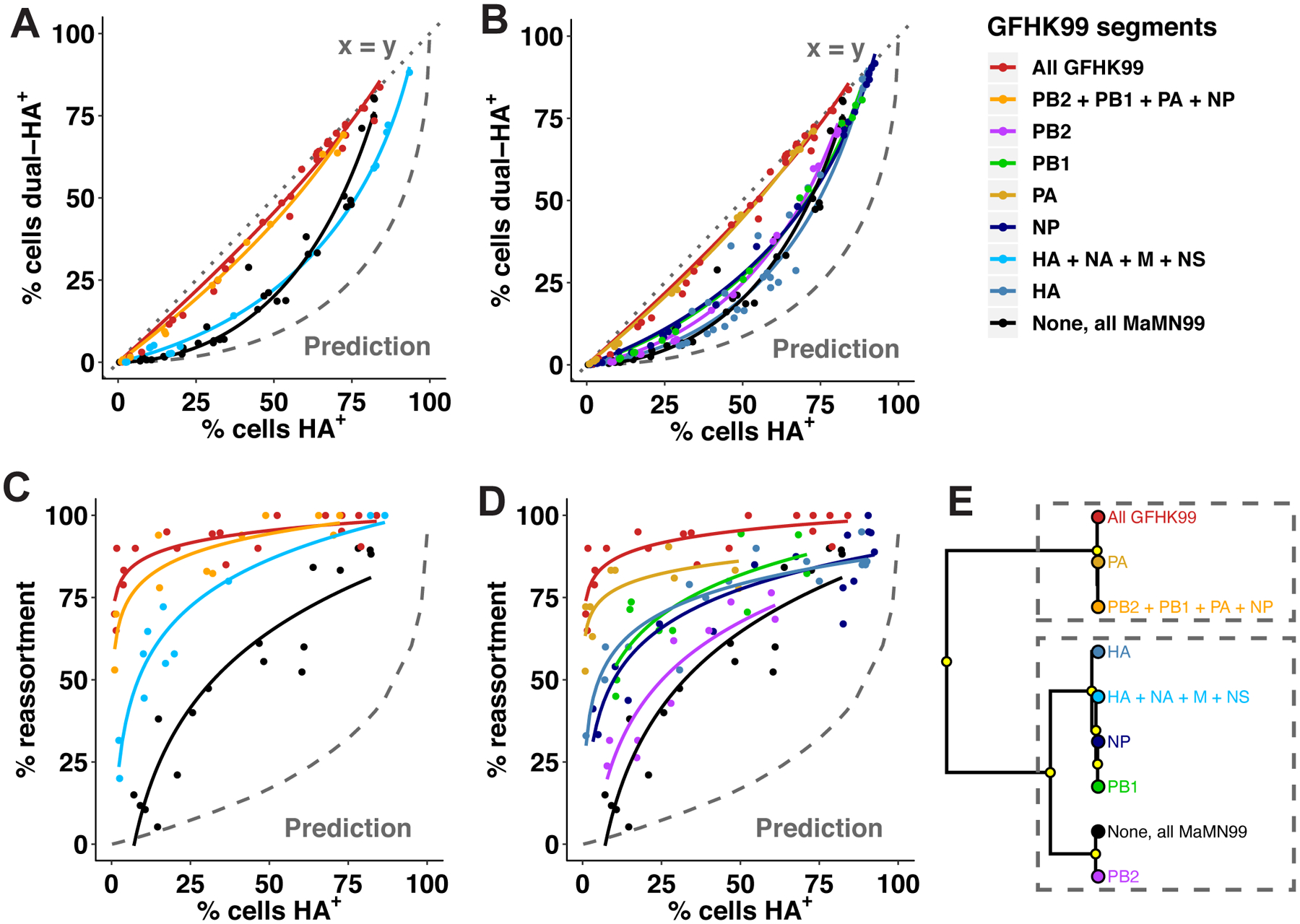

The PA segment is a major determinant of multiple-infection dependence

To identify viral determinants of multiple-infection dependence, we mapped segments responsible for the high reassortment of GFHK99 virus in MDCK cells. Segments of GFHK99 virus were placed into a MaMN99 background and, for each chimeric genotype, WT and VAR strains were generated. Coinfections were performed in MDCK cells and HA expression and reassortment were measured. Two viruses are similar to the parental GFHK99 virus in the levels of dual HA positivity observed: MaMN99:GFHK99 3PNP and MaMN99:GFHK99 PA (Figure 4A–B). Quantification of reassortment revealed that several chimeric viruses reassort at a higher frequency than MaMN99, but that the MaMN99:GFHK99 3PNP and MaMN99:GFHK99 PA viruses show the highest reassortment, comparable to that seen for the parental GFHK99 genotype (Figure 4C–D). Clustering analysis revealed that only these two genotypes group with GFHK99 parental virus, while each of the other genotypes groups with MaMN99 virus (Figure 4E). Thus, while other viral genes may contribute, PA is the primary genetic determinant of the high reassortment exhibited by GFHK99 virus in MDCK cells and defines a need for cooperation between coinfecting viruses. To verify the contribution of the PA segment by a second approach, we evaluated the impact of VAR virus coinfection on WT vRNA synthesis for the MaMN99:GFHK99 PA strain. The results confirm that the GFHK99 PA segment increases reliance on multiple infection, specifically in mammalian cells (Extended Data Figure 3).

Figure 4. Coinfection and reassortment of chimeric viruses reveal a major role for the viral PA gene segment.

Reverse genetics was used to place one or more genes from GFHK99 virus into a MaMN99 background. Coinfections with homologous WT and VAR strains were performed in MDCK cells as in Figure 1. The relationship between % cells HA positive and % cells dually HA positive (A, B) and reassortment levels (C, D) are shown for each genotype. Experimental results are compared to a theoretical prediction based on Poisson statistics and in which singly infected and multiply infected cells have equivalent burst sizes (Prediction). Clustering analysis of the regression models shown in (A-D) is used to partition the behavior of each chimeric genotype into one of two clusters, denoting closer similarity to GFHK99 or MaMN99 (E). Yellow circles indicate nodes with >95% bootstrap support. Data shown for GFHK99 and MaMN99 viruses are the same as those displayed in Figure 1.

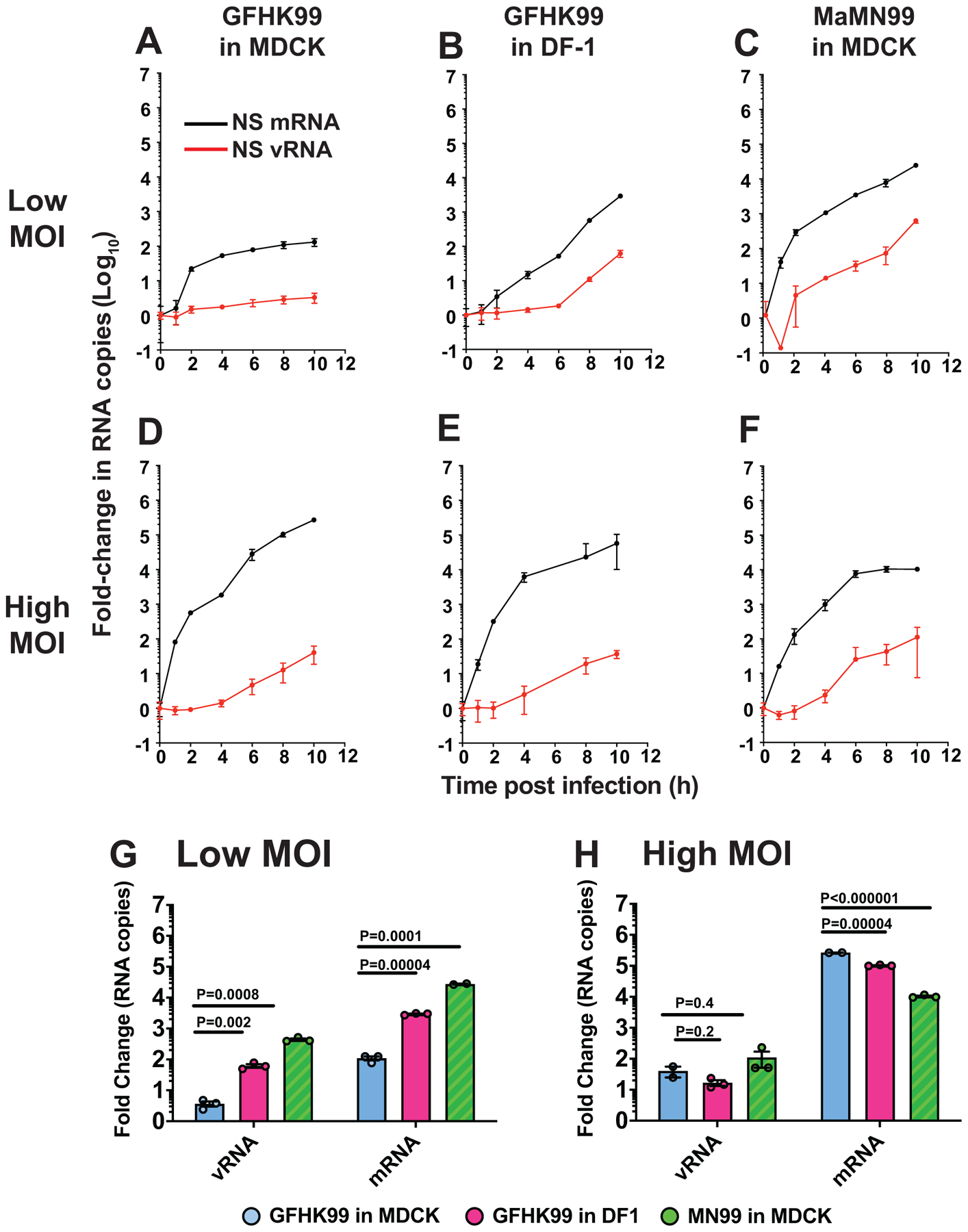

Multiple infection accelerates viral replication and transcription

Because genetic mapping implicated PA, we tested the effects of multiple infection on viral replication and transcription by measuring accumulation of vRNA and mRNA following low or high MOI infection (Extended Data Figure 4). GFHK99 virus was examined in DF-1 and MDCK cells and MaMN99 virus was tested in MDCK cells. Under low MOI conditions in MDCK cells, GFHK99 vRNA levels remain low throughout the time course. GFHK99 mRNA increases early, perhaps reflecting robust primary transcription, then accumulates relatively slowly. Both viral RNA species accumulate at a significantly higher rate for GFHK99 virus in DF-1 cells and MaMN99 virus in MDCK cells. At high MOI, accumulation of GFHK99 mRNA and vRNA in MDCK cells occurs at a similar rate to that seen for GFHK99 virus in DF-1 cells or MaMN99 virus in MDCK cells. Thus, a host-specific defect in GFHK99 polymerase activity that affects both replication and transcription is seen at low MOI. This defect is, however, resolved under conditions where multiple infection is prevalent.

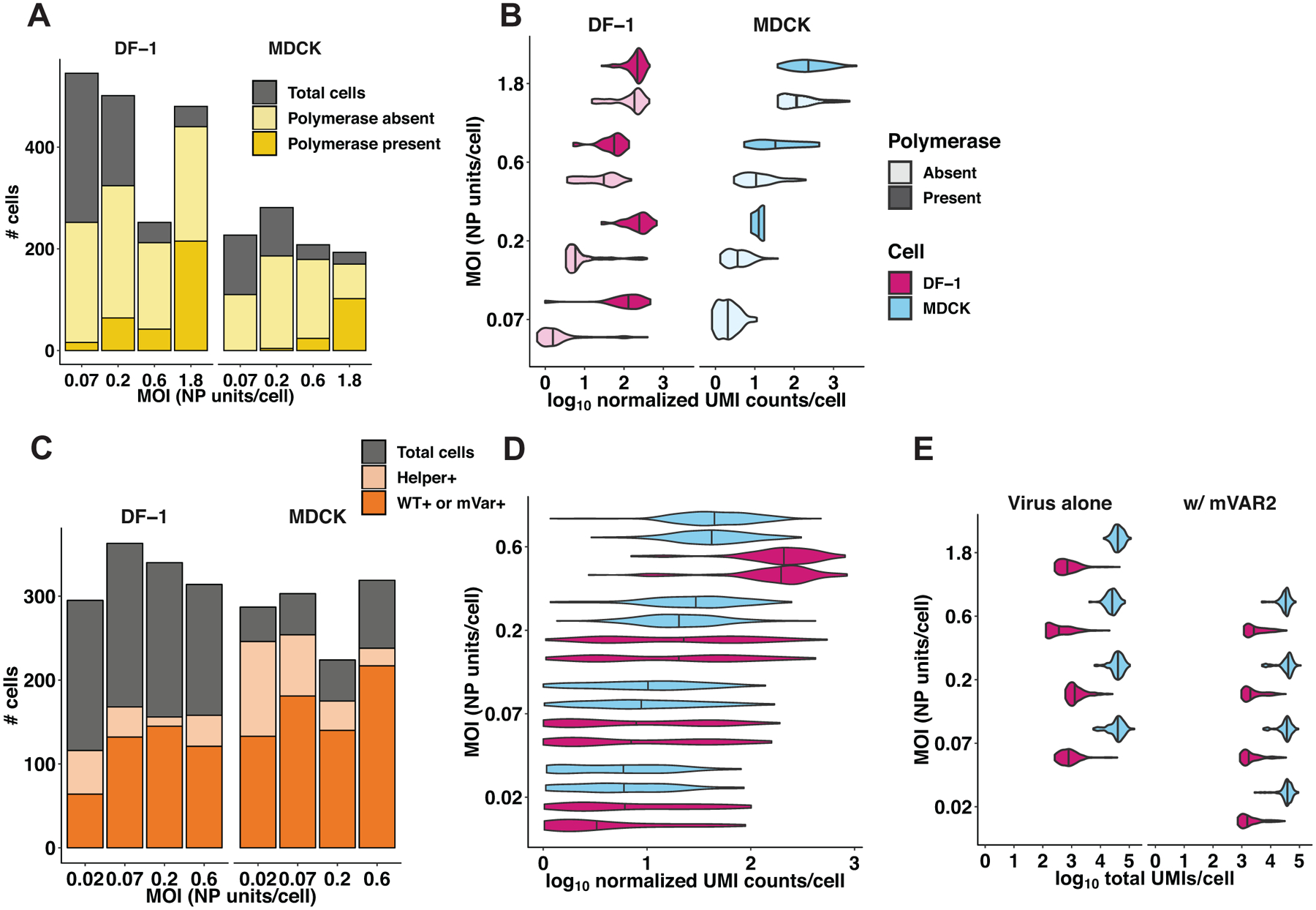

Single-cell mRNA sequencing reveals a need for cooperation

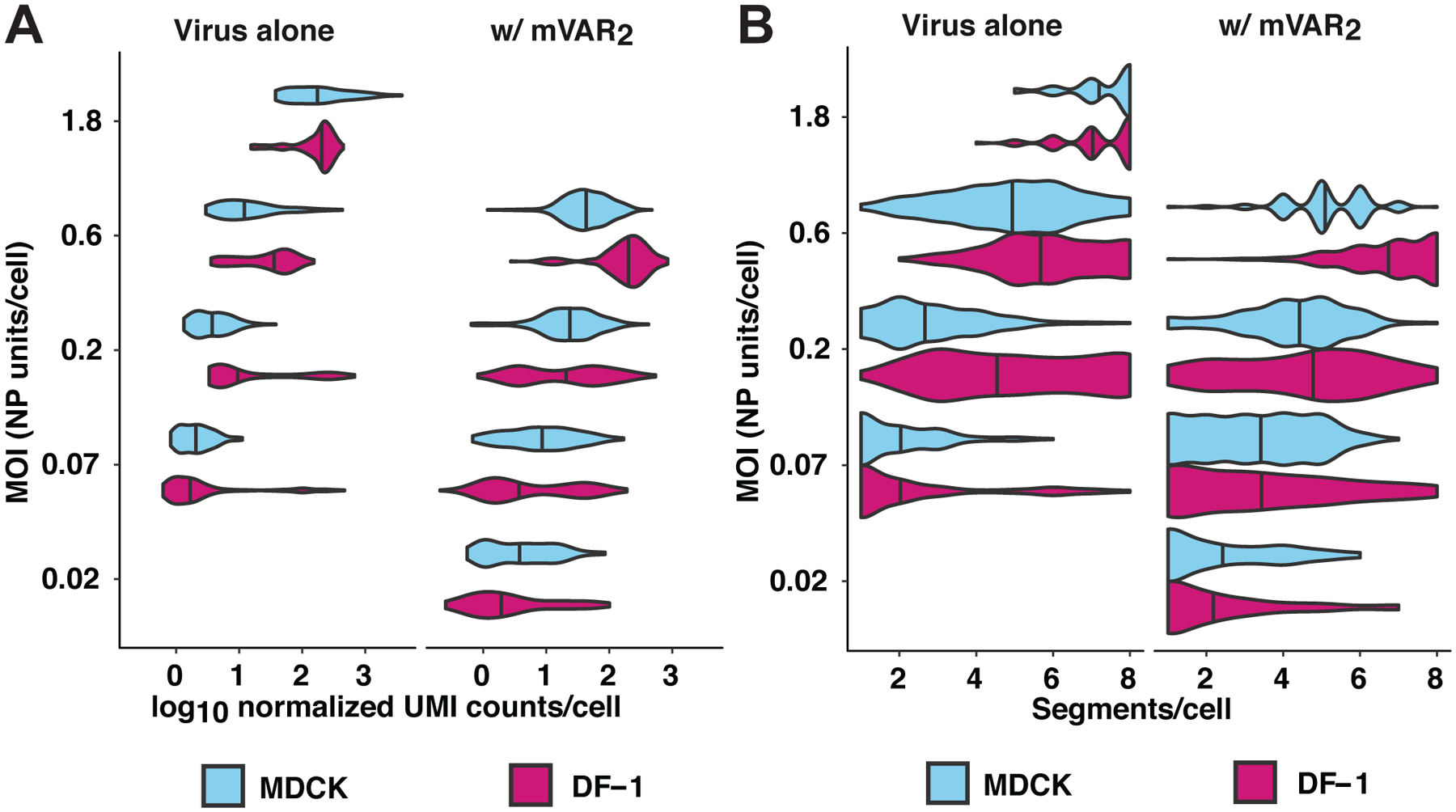

To assess the heterogeneity of viral RNA synthesis, we evaluated GFHK99 virus-infected DF-1 and MDCK cells by single-cell mRNA sequencing. We used a thresholding approach to exclude cells that were unlikely to be infected, but may carry small amounts of viral mRNA owing to lysis of neighboring cells (Extended Data Figure 5). To allow comparison between cell types and experiments, each cell’s total transcript abundance was normalized to the median number of transcripts per cell in the relevant sample. The normalized and log10 transformed counts of viral transcripts per cell were then compared across conditions. We found that the amount of detected GFHK99 viral mRNA varies widely between individual DF-1 cells, consistent with previous observations24–26. In contrast, GFHK99 viral mRNA levels are uniformly low in MDCK cells, especially at the lower MOIs tested (Figure 5A, left facet).

Figure 5. Homologous coinfecting virus boosts GFHK99 viral transcription in single cells and reveals comparable rates of segment detection in MDCK and DF-1 cells.

DF-1 or MDCK cells were infected with GFHK99 virus (left facet) at MOIs of 0.07, 0.2, 0.6, or 1.8 NP-expressing units per cell (n = 1,228 DF-1 cells, 645 MDCK cells), or a 1:1 mixture of GFHK99 WT and GFHK99 mVAR1 viruses at four different total MOIs (0.02, 0.07, 0.2, 0.6 NP-expressing units per cell, n = 462 DF-1 cells, 671 MDCK cells) and a constant amount of GFHK99 mVAR2 virus (0.1 PFU per cell in DF-1 cells, 1.0 PFU per cell in MDCK cells) (right facet). Per condition, two replicate wells were infected and cells from these replicates were pooled prior to analysis, giving n=1 sequencing replicate per infection condition. The number of cells analyzed per condition is shown in Extended Data Figure 6. Each violin plot shows the full distribution of total viral RNA (A) or distinct viral genome segments (B) per cell in each cell-MOI infection condition. Vertical lines denote the median of each distribution. UMI = unique molecular identifier.

To evaluate whether low transcript abundance corresponded with failure to detect polymerase-encoding segments, we stratified the data based on detection of PB2, PB1, PA and NP. Consistent with prior reports24, viral transcript levels are higher in cells that contained PB2, PB1, PA and NP transcripts compared to those in which one or more of these transcripts was not detected (Extended Data Figure 6). We noted that PB2, PB1 and PA mRNAs are markedly less abundant than the other viral transcripts, however. Thus, the correspondence between failure to detect polymerase transcripts and low viral mRNA abundance may simply be due to the higher likelihood of these mRNAs falling below the limit of detection in cells that have low overall viral transcription.

To measure the impact of coinfecting viruses in individual cells, we repeated the single-cell sequencing experiment with the addition of two variants, GFHK99 mVAR1 and GFHK99 mVAR2. Cells were inoculated with GFHK99 WT and GFHK99 mVAR1 viruses in a 1:1 ratio. Simultaneous coinfection with GFHK99 mVAR2 virus was performed at the concentration found to give optimal support of WT RNA replication in Figure 3D: 0.1 PFU per cell in DF-1 cells and 1.0 PFU per cell in MDCK cells. After mRNA sequencing, only cells in which transcripts from all eight mVAR2 segments were detected were analyzed further and cells that likely obtained viral RNA through lysis were excluded (Extended Data Figure 5). In cells infected with both WT and mVAR1 viruses, viral transcript abundance is calculated separately for each, so that coinfected cells contribute two distinct measurements to the dataset. Viral transcript levels per cell are shown in Figure 5A alongside data from the first experiment. In comparing the two infections, we observe that total viral transcript abundance is markedly lower in MDCK compared to DF-1 cells in the first infection, but this effect is almost entirely mitigated by the presence of mVAR2 virus in the second infection. This reduction in the disparity between DF-1 and MDCK cells resulted from the fact that mVAR2 virus increased transcript abundance by 149% in DF-1 cells, but 258% in MDCK cells (p<10–4, linear mixed effects model) (Figure 5A). These data underscore the significance of collective interaction to ensure productive infection in diverse hosts.

Because only a subset of a cell’s transcripts is captured and therefore reliably detected27, single cell mRNA sequencing does not allow a robust determination of segment presence or absence in a cell. The addition of mVAR2 virus improves the sensitivity with which WT transcripts can be detected, however, and – as noted above – levels the playing field between MDCK and DF-1 cells. We therefore evaluated the number of distinct viral gene segments detected per cell, as indicated by the presence of the corresponding mRNAs. Failure to detect a subset of segments is common in our datasets, as with others’24,26. Addition of mVAR2 virus increases the number of segments per cell detected, however, suggesting that failure to detect is often a result of the limit of detection (Figure 5B). Importantly, in the presence of mVAR2 virus, segments detected per cell was comparable between MDCK and DF-1 cells across all MOIs tested (Figure 5B). Thus, the frequency with which incomplete GFHK99 viral genomes are expressed is similar between these mammalian and avian cell lines.

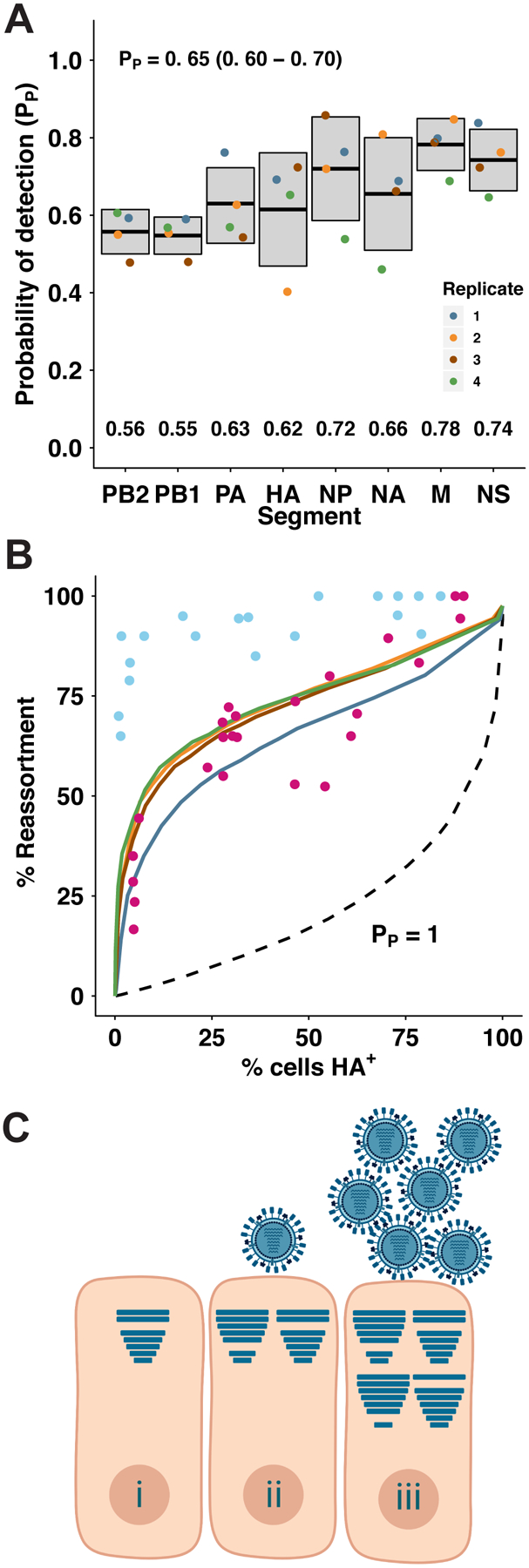

Frequency of incomplete GFHK99 genomes is moderate

Given the limitations of single-cell mRNA sequencing for the detection of rare transcripts, we employed a second single-cell approach to quantify the frequency with which fewer than eight vRNAs are replicated in GFHK99-infected MDCK cells8. MDCK cells were coinfected with a low MOI of GFHK99 WT virus and a high MOI of GFHK99 VAR2 virus. Single cells were then sorted onto a naïve cell monolayer and multicycle replication was allowed. During this time, the GFHK99 VAR2 virus propagates WT segments, even when less than the full WT genome is available. To determine which viral gene segments were present in the initially sorted cell, RT-qPCR with primers that differentiate WT and VAR2 gene segments was applied. The results were then used to calculate the probability that a cell infected with a single WT virus contains a given segment. The observed Probability Present (PP) varies among the segments from 0.56 to 0.8 (Figure 6A). The product of the eight PP values gives an estimate of the proportion of singular infections in which all segments are replicated. This estimate is 3.2% for GFHK99 virus in MDCK cells.

Figure 6. Incomplete GFHK99 virus genomes are present but not sufficiently abundant to account for observed reassortment in MDCK cells.

Incomplete viral genomes were quantified experimentally by a single-cell assay which relies on the amplification of incomplete viral genomes of GFHK99 WT virus (0.018 PFU per cell) by a genetically similar coinfecting virus, GFHK99 VAR2. Based on the rate of detection of GFHK99 WT virus segments in this assay, the probability that a given segment would be present and replicated in a singly infected MDCK cell is reported as PP. A) Summary of experimental PP data. n = 4 biological replicates, distinguished by color. Horizontal bars and shading represent mean ± standard deviation. Mean PP,i values for each segment are indicated at the bottom of the plot area. Average PP for each experiment was calculated as the geometric mean of the eight PP,i values, and the mean ± standard deviation of those four summary PP values is shown at the top of the plot area. B) Experimentally obtained PP,i values in (A) were used to parameterize a computational model7. Levels of reassortment predicted using the experimentally determined parameters are shown with colors corresponding to points in (A). Levels of reassortment predicted if PP=1.0 are shown with the dashed line. Observed reassortment of GFHK99 WT and VAR viruses in MDCK cells are shown with blue circles. Observed reassortment of GFHK99 WT and VAR viruses in DF-1 cells are shown with pink circles. Observed data are the same as those plotted in Figure 1. C) Model: complementation of incomplete viral genomes is necessary but not sufficient for robust progeny production from mammalian cells infected with GFHK99 virus. Cells infected with single virions often replicate incomplete viral genomes and therefore do not produce viral progeny (i). In mammalian cells, complementation of incomplete viral genomes through coinfection may allow progeny production (ii), but robust viral yields require the delivery of additional genomes to the cell, beyond the levels needed for complementation (iii). Horizontal bars within cells represent segments successfully delivered and replicated.

We used these data together with our model of IAV coinfection and reassortment7 to evaluate whether incomplete viral genomes account for the focusing of GFHK99 virus production within multiply infected cells. In the model, the frequency of successful segment replication is governed by eight PP parameters and an infected cell only produces virus if at least one copy of all eight segments are replicated. Importantly, the amount of virus produced from productively infected cells is constant in this model – there is no additional benefit to multiple infection. When the eight experimentally determined PP values for GFHK99 virus in MDCK cells are used as parameters, the theoretical prediction of reassortment frequency is much lower than that observed for GFHK99 viruses in MDCK cells, but a good match with the reassortment seen in DF-1 cells (Figure 6B). Clearly, the frequency with which GFHK99 segments fail to be replicated cannot fully account for the high reassortment seen in MDCK cells, but can account for the more moderate reliance on multiple infection seen in DF-1 cells. Thus, in mammalian cells, a full GFHK99 viral genome is necessary but not sufficient to support robust replication.

Discussion

Our data reveal that moderate reliance of IAV on multiple infection is the norm. An exceptionally high need for multiple infection can, however, occur when an IAV infects a new species. Thus, our findings identify increased reliance on multiple infection as a novel component of IAV host restriction. Since not all mismatched virus-host combinations show a high reliance on multiple infection, the data indicate that a need for collective interactions is a potential manifestation of IAV host restriction, not a universal feature. Dependence on multiple infection is of particular interest as a barrier to cross-species transfer for two reasons: first, it can be overcome in the absence of genetic adaptation, through high dose infection; and second, it leads to high levels of reassortment, which in turn can facilitate adaptation to a new host.

As has been seen for other IAVs5,8,24,26, complementation of incomplete genomes is often needed for productive GFHK99 infection. Additional cooperative interactions are, however, evident in mammalian cells. These data point to a model in which the presence of not just complete genomes, but rather multiple copies of the viral genome, are needed to overcome host-specific barriers to infection (Figure 6C). Our data suggest that this phenotype is a feature of poultry-adapted H9N2 viruses; whether a need for multiple infection in mammalian cells extends to other poultry-adapted lineages is of interest for future study. H9N2 viruses are, however, highly relevant in the context of zoonotic infection due to their prevalence at the poultry-human interface and their shared gene pool with H5N1 and H7N9 viruses that have caused hundreds of severe human infections28–33.

We previously showed that localized spread within a tissue facilitates complementation of incomplete viral genomes, allowing relatively efficient conversion of non-productive infection events to productive ones34. In the context of transmission between hosts, however, the potential for multiple infection may be limited. Indeed, the tight genetic bottleneck observed in human–human transmission is consistent with infection initiated by single particles35,36. In line with this concept, our prior work in a guinea pig transmission model revealed that a seasonal IAV engineered to be fully reliant on multiple infection replicated efficiently but did not transmit to contacts34. Thus, we favor a model in which transmission of IAV among native hosts is typically mediated by rare single infections that result in productive infection. Conversely, our present work with GFHK99 and related viruses suggests that this mechanism may not be operational in the context of zoonotic transmission, owing to more extreme inefficiency of single infections. Here, the coordinated transfer of multiple virions between hosts (e.g. in a single respiratory droplet) may be critical to overcome species barriers.

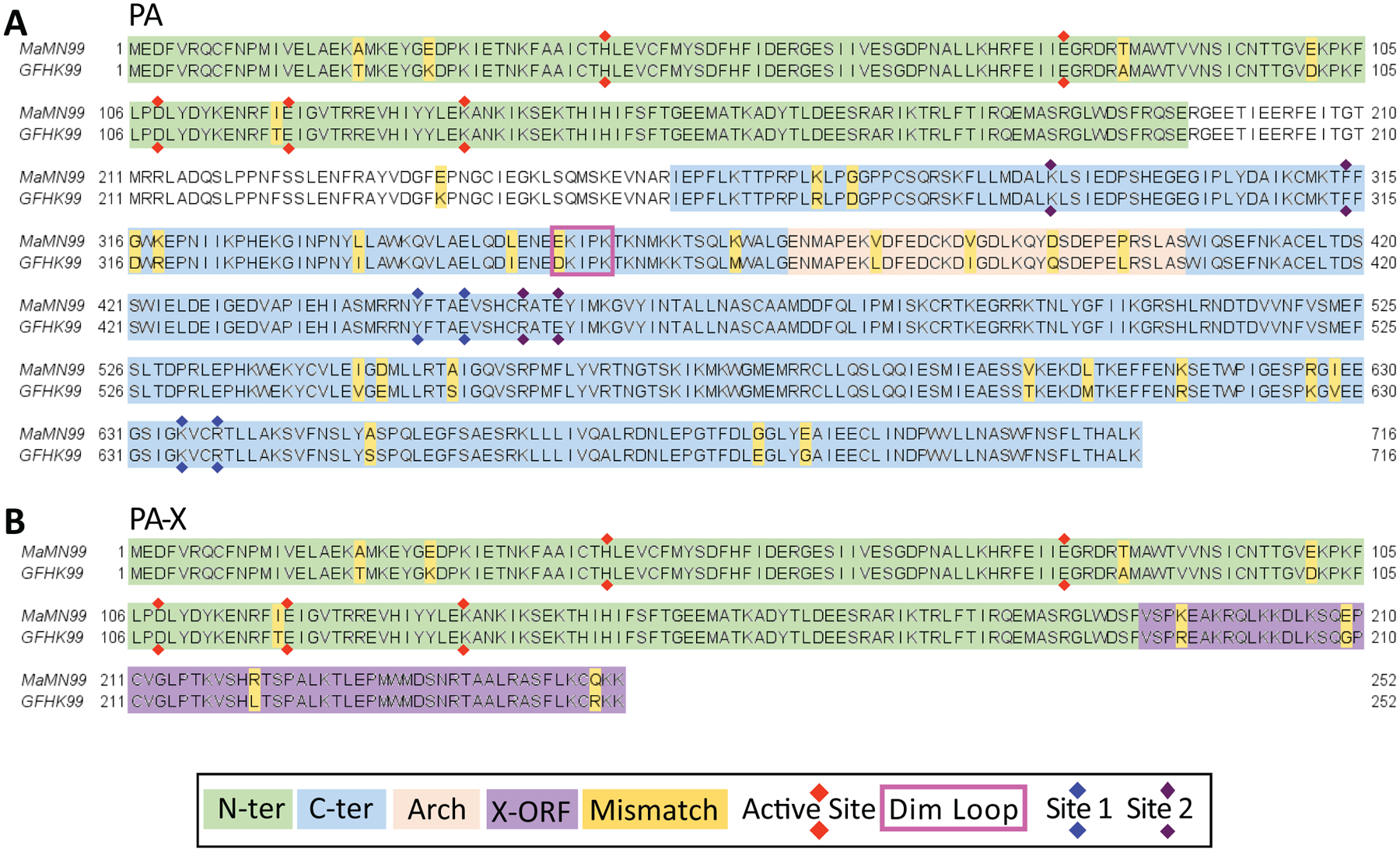

Our data implicate the PA segment, which encodes PA and PA-X37, in defining an acute reliance on cooperation. PA is an essential component of the polymerase38. It carries the endonuclease required for cap-snatching, an activity essential for viral transcription39. PA also comprises much of the interface for viral polymerase dimerization, which is needed for viral replication40. PA-X contributes to the shut-off of host protein synthesis41,42. Alignment of these proteins encoded by GFHK99 and MaMN99 viruses reveals 29 differences in PA and 9 in PA-X (Extended Data Figure 7). Three-dimensional modeling based on a recently reported structure40 did not predict marked differences. Nevertheless, polymorphisms noted in and near the dimerization loop suggest a model in which the reliance of GFHK99 virus on multiple infection may result from an inefficiency of dimerization and consequent inefficiency of vRNA synthesis40. This model is attractive in that aberrant in vitro initiation of vRNA synthesis by a dimerization mutant was ameliorated with increased polymerase concentration40. We speculate that multiple infection could lead to a similar effect within the cell. Finer mapping of the phenotype within PA and targeted functional studies are needed to test this model and explore other possible mechanisms.

Importantly, we show that viral cooperation is not limited to complementation of defects; rather, interactions among homologous coinfecting viruses can be highly biologically significant. Such cooperation is expected to have a strong impact on viral fitness and evolution by modulating the efficiency of spread within and between hosts and by changing how a virus population samples sequence space43–46. Thus, multiple infection dependence is likely to play an important role in determining the outcomes of IAV infection and evolution in diverse hosts.

Methods

Cells and cell culture media

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, a gift from Peter Palese, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, were used in all experiments. MDCK cells from Daniel Perez at University of Georgia were used for plaque assays as this variant of the MDCK line was found to yield more distinct plaques for the GFHK99 strain. Both MDCK cell lines were maintained in minimal essential medium (MEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals), penicillin (100 IU), and streptomycin (100 μg per mL) (PS; Corning). 293T cells (ATCC CRL-3216) and DF-1 cells (ATCC CRL-12203) were maintained in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and PS. Duck embryo cells (ATCC CCL-141) were maintained in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM; ATCC) supplemented with 10% FBS and PS. Normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells were acquired from Lonza and were amplified and differentiated into air-liquid interface cultures as recommended by Lonza and described in Danzy et al.47. All cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. Cell lines were not authenticated. All cells were tested monthly for mycoplasma contamination while in use. Medium for culture of IAV in each cell line (virus medium) was prepared by supplementing the appropriate media with 4.3% bovine serum albumin and penicillin (100 IU), and streptomycin (100 μg per mL). Ammonium chloride-containing virus medium was prepared by the addition of HEPES buffer and NH4Cl at final concentrations of 50 mM and 20 mM, respectively.

Viruses

All viruses were generated by reverse genetics48. For avian viruses, 293T cells transfected with reverse genetics plasmids 16–24 h prior were injected into the allantoic cavity of 9–11 day old embryonated chicken eggs and incubated at 37°C for 40–48 h. The resultant egg passage 1 stocks were used in experiments. For NL09-based viruses, 293T cells transfected with reverse genetics plasmids 16–24 h prior were co-cultured with MDCK cells at 37°C for 40–48 h. Supernatants were then propagated in MDCK cells from low MOI to generate NL09 working stocks. Defective interfering segment content of PB2, PB1, and PA segments was confirmed to be minimal for each virus stock, as described previously49 (Extended Data Figure 8). All plaque assays were performed in MDCK cells; viruses were also titered by flow cytometry and/or RT qPCR-based methods where indicated. The reverse genetics system for influenza A/guinea fowl/Hong Kong/WF10/99 (H9N2) virus was reported previously50,51. This strain has been referred to as WF10 in previous publications50–52. For consistency with other strains used in the present manuscript, it is referred to herein as GFHK99. A low passage isolate of influenza A/mallard/Minnesota/199106/99 (H3N8) virus, referred to herein as MaMN99, was obtained from David Stallknecht at the University of Georgia53. The virus was passaged once in eggs and then the eight cDNAs were generated and cloned into the ambisense pDP2002 vector54. Reverse genetics systems for influenza A/duck/Hong Kong/448/78 (H9N2) and A/quail/Hong Kong/A28945/88 (H9N2), referred to herein as dkHK78 and QaHK88, were similarly generated following culture in eggs. To increase the recovery efficiency of viruses containing polymerase components from the MaMN99 virus, pCAGGS support plasmids encoding PB2, PB1, PA and NP proteins of the A/WSN/33 (H1N1) strain were supplied.

GFHK99 WT, MaMN99 VAR and NL09 VAR viruses were engineered to contain a 6XHis epitope tag plus GGGS linker at the N-terminus of the HA protein following the signal peptide. GFHK99 VAR1, MaMN99 WT and NL09 VAR viruses contain similarly modified HA genes, with an HA epitope tag plus a GGGS linker inserted at the N-terminus of the HA protein22. All assays except single-cell mRNA sequencing used viruses carrying these epitope tags.

Silent mutations were introduced into VAR viruses by site-directed mutagenesis to allow genotyping of WT and VAR segment origin. The specific changes introduced into all VAR viruses used here are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Mutations introduced into GFHK99 VAR1, MaMN99 VAR, and NL09 VAR viruses enable detection by high-resolution melt analysis or probe-based droplet digital PCR. Mutations introduced into the GFHK99 VAR2 strain were designed to confer unique primer binding sites relative to GFHK99 WT virus. Viruses used for single-cell mRNA sequencing, GFHK99 mVAR1 and GFHK99 mVAR2, carry mutations near the 3’ end of each transcript to allow detection by sequencing following oligo-dT priming24.

Synchronized, single-cycle infection conditions

Conditions designed to synchronize viral entry and prevent propagation of progeny viruses were used for all cell culture-based infections with the exception of those performed for measurement of PP values. Synchronized, single-cycle infections were performed as follows: Cell monolayers were washed three times with PBS and placed on ice. Chilled virus inoculum was added to each well and incubated at 4°C for 45 minutes with occasional rocking to allow attachment without entry55. Inoculum was aspirated and cell monolayer was washed three times with cold PBS before addition of warm virus medium lacking trypsin. Cultures were incubated at 37°C. At 3 h post-infection, virus medium was replaced with ammonium chloride-containing virus medium. Addition of ammonium chloride to the medium prevents acidification of endosomes, thereby blocking further IAV infection56. Cultures were returned to 37°C for the remainder of the incubation time.

Infection of cultured cells for quantification of coinfection and reassortment

MDCK or DF-1 cells were seeded at a density of 4 ×105 cells per well in 6-well dishes 24 h before inoculation. Virus inoculum was prepared by combining WT and VAR viruses at high titer in a 1:1 ratio based on PFU titers, and then diluting in PBS to achieve MOIs ranging from 10 to 0.01 PFU per cell. Synchronized, single cycle infection conditions were used. In addition, owing to the low yield of IAV in DF-1 cells, acid inactivation of inoculum virus was performed at 1 h post-infection for this cell type. This procedure is needed if residual inoculum virus would otherwise comprise an appreciable proportion of the virus sampled at 12 or 16 h post-inoculation. For acid inactivation, media was aspirated and replaced with 500 μL of PBS-HCl, pH 3.00 and incubated 5 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed once with PBS before the addition of virus medium. GFHK99 virus-infected cells were harvested at 12 h post-infection due to high amounts of cytopathic effects at later time points. Cells infected with MaMN99 virus and MaMN99:GFHK99 chimeric viruses were harvested at 16 h post-infection. NL09 virus reassortment data shown in Figure 1C were reported previously57 and are included here to allow comparison to the avian strains used.

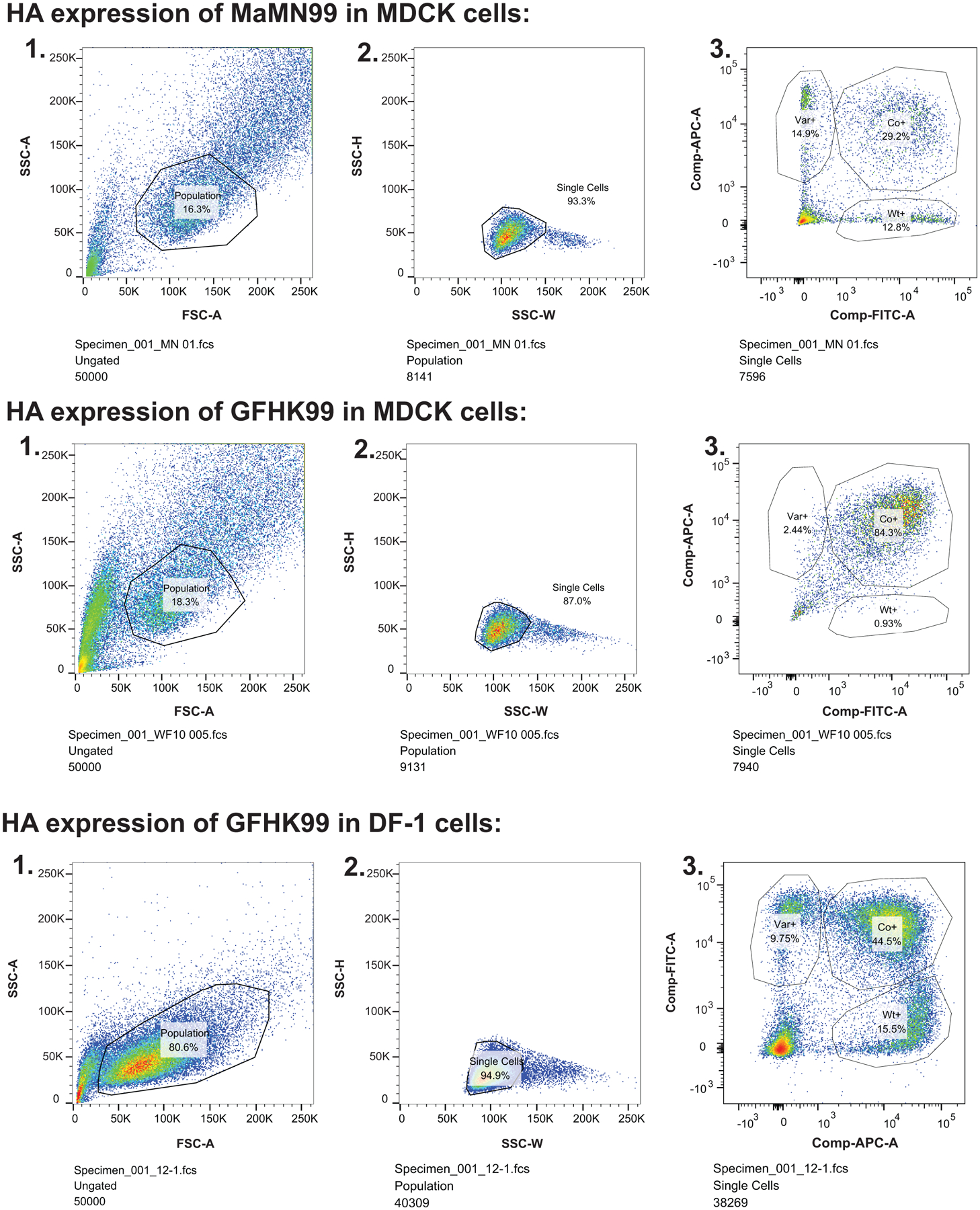

Determination of infection and coinfection levels based on HA surface expression.

To enumerate infected cells, surface expression of HIS and HA epitope tags was detected by flow cytometry (Extended Data Figure 9). This method was previously described in detail22. Cells were fixed following staining by resuspending in FACS buffer and 1% paraformaldehyde. The percentage of cells positive for either or both epitope tags is expressed as % cells HA+. The percentage of cells positive for both epitope tags is expressed as % cells dual-HA+. The relationship between these two parameters was evaluated by plotting % cells dual-HA+ against % cells HA+ and regressing the resultant curve as a polynomial:

where β2 and β1 are genotype-specific. For a given fraction of cells expressing HA, the expected fraction of cells expressing both HA proteins is derived from the Poisson distribution with λ = –ln(1 – % cells HA+):

From the regression models, we then quantified the degree of linearity using the equation:

Animal models and reassortment in vivo

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. Studies were conducted under animal biosafety level 2 (ABSL-2) containment and approved by the IACUC of the University of Georgia (protocols A201506-026-Y3-A2 and A201506-026-Y3-A5) for quail studies or the IACUC of Emory University (protocol PROTO201700595) for guinea pig studies. Animals were humanely euthanized following guidelines approved by the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA).

Quail eggs obtained from the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia, were hatched at the Poultry Diagnostic and Research Center, University of Georgia. Two days before virus inoculation, quail sera were confirmed to be seronegative for IAV exposure by NP ELISA (IDEXX, Westbrook, ME). At 3 weeks of age, birds were moved into a HEPA in/out BSL2 facility and each group divided into individual isolator units.

Groups (n=6) of 3-week old Japanese quail (Coturnix Japonica) were used to determine the 50% quail infectious dose of the 1:1 GFHK99 WT and GFHK99 VAR1 virus mixture. Each quail was inoculated with 500 μl by oculo-naso-tracheal route of virus mixture in PBS, at increasing concentrations of 100 to 106 TCID50 per 500 μL. Tracheal and cloacal swab specimens were collected daily from each bird in brain heart infusion media (BHI). Swab samples were analyzed by TCID50 assay and titers of tracheal swabs collected at 4 d post-inoculation were used to determine the QID50 by the Reed and Muench method58. Virus was not detected in cloacal swabs. QID50 was found to be equivalent to 1 TCID50.

To quantify reassortment in quail, samples collected from quail (n=6) infected with the 102 TCID50 dose of the 1:1 GFHK99 WT and GFHK99 VAR1 virus mixture were used. These were the same birds as used to determine QID50. Virus shedding kinetics were determined by plaque assay of tracheal swab samples and samples from days 1, 3 and 5 were chosen for genotyping of virus isolates.

Female Hartley strain guinea pigs weighing 250–350 g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and housed by Emory University Department of Animal Resources. Prior to intranasal inoculation and nasal washing, guinea pigs were anesthetized by intramuscular injection with 30 mg per kg ketamine/ 4 mg per kg xylazine. The GPID50 of GFHK99 WT/VAR1 and MaMN99 WT/VAR virus mixtures were determined as follows. Groups of four guinea pigs were inoculated intranasally with virus mixture in PBS at doses of 100 to 105 PFU per 300 μL inoculum. Daily nasal washes were collected in 1 mL PBS and titered by plaque assay. Results from day 2 nasal washes were used to determine the GPID50 by the Reed and Muench method58. The GPID50 of GFHK99 virus was found to be 2.1 × 103 PFU; that of MaMN99 virus was 2.1 × 101 PFU. The GPID50 of NL09 virus was previously determined to be 1 × 101 PFU59.

To evaluate reassortment kinetics in guinea pigs, groups of six animals were infected with 102 × GPID50 of the aforementioned GFHK99 WT / VAR1, MaMN99 WT / VAR or NL09 WT / VAR virus mixtures. Virus inoculum was given intranasally in a 300 μL volume of PBS. Nasal washes were performed on days 1–6 post-inoculation and titered for viral shedding by plaque assay. Viral genotyping was performed on samples collected on day 1, 3, and 5 for each guinea pig.

Quantification of reassortment and effective diversity

Reassortment was quantified for in vitro coinfection supernatants, guinea pig nasal washes, and quail tracheal swabs as described previously22. Briefly, plaque assays were performed on MDCK cells in 10 cm dishes to isolate virus clones. 1 mL serological pipettes were used to collect agar plugs into 160 μl PBS. Using a ZR-96 viral RNA kit (Zymo), RNA was extracted from the agar plugs and eluted in 40 μl nuclease free water (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription was performed using Maxima RT (Thermofisher) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting cDNA was diluted 1:4 in nuclease free water and each cDNA was combined with segment specific primers (Supplementary Table 2) and Precision Melt Supermix (Bio-Rad) and analyzed by qPCR in a CFX384 Touch real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) designed to amplify a ~100 bp region of each gene segment which contains a single nucleotide change in the VAR virus. The qPCR was followed by high-resolution melt (HRM) analysis to differentiate WT and VAR amplicons60. Precision Melt Analysis software (Bio-Rad) was used to determine the parental virus origin of each gene segment based on melting properties of the cDNAs and comparison to WT and VAR controls. Each individual plaque was assigned a genotype based on the combination of WT and VAR genome segments, with 2 variants on each of 8 segments allowing for 256 potential genotypes. We note that, despite its high reliance on multiple infection for robust replication, the GFHK99 virus does form very small, clonal plaques on MDCK cells. These plaques were confirmed to be clonal based on the unambiguous typing of each gene segment as either WT or VAR in origin.

Reassortment data were used to calculate viral genotypic diversity; that is, the diversity of the 256 possible WT/VAR genotypes present in a given sample. Diversity was quantified as reported previously61, by calculating Simpson’s Index, given by D = sum(pi2), where pi represents the proportional abundance of each genotype62. Simpson’s Index accounts for both the raw number of species and variation in abundance of each, and is sensitive to the abundance of dominant species. These features are important to ensure that overrepresentation of a single reassortant genotype does not cause a viral population to appear more diverse than it actually is. Because Simpson’s Index does not scale linearly, each sample’s Simpson’s Index value was converted to a corresponding Hill number to derive its effective diversity, N2 = 1/D63, which is defined as the number of equally abundant species required to generate the observed diversity in a sample community. Because it scales linearly, Hill’s N2 allows a more intuitive comparison between communities (i.e., a community with N2 = 10 species is twice as diverse as one with N2 = 5) and is suitable for statistical analysis by basic linear regression methods64. Robust linear models of N2 vs. time were regressed using the R package MASS.

Hierarchical clustering analysis

To compare the behavior of multiple viruses during in vitro coinfections, a hierarchical clustering algorithm was used. In these experiments, multiplicity dependence was measured by analyzing HA co-expression and reassortment as a function of the percentage of cells expressing HA. Each of these regression models contain two parameters (% cells dual-HA+ = β2* Expectation(% cells HA+) + β1*(% cells HA+), and % reassortment = β0 + β1 * ln(% cells HA+). The behavior of a given virus can therefore be expressed as a set of four parameters. These parameters were used to calculate the distance between each pair of viruses, and Ward’s method of aggolomerative hierarchical clustering was then used to organize viruses into clusters based on these distances65. Briefly, this algorithm combines a nearby pair of elements into a cluster with a new position that is halfway between the original individuals. This process is repeated until all elements have been incorporated into one cluster. The R package pvclust was used to calculate statistical support for the existence of each node by multiscale bootstrap resampling, with nodes appearing in 95% of trials being deemed statistically significant. Each dendrogram was then divided into two clusters to determine whether the behavior of GFHK99 virus in MDCK cells represented a true outgroup (Figure 1), or to determine whether each GFHK99:MaMN99 chimeric virus was more similar to GFHK99 or MaMN99 parent virus (Figure 4).

Single-cycle viral growth kinetics

DF-1 or MDCK cells were seeded at 4×105 cells per well in 6-well dishes 24 h prior to infection. Virus was serially diluted using PBS. Synchronized, single-cycle infection conditions with acid inactivation of inoculum virus as described above were used. At each time point, 120 μl supernatant was collected. Viral titers for each sample were assessed by plaque assay in MDCK cells. Each MOI condition was used in 5–6 wells in parallel infections. Three wells served as technical replicates for growth curve sampling while the remaining wells were harvested at 24 h post-infection to enumerate HA-expressing cells via flow cytometry. Flow cytometry data for NL09 in MDCK cells are not included owing to low sensitivity of the assay for this virus. In cases where acid inactivation was inefficient, the replicate was eliminated, and data are plotted in duplicate.

Effect of increasing multiple infection on viral RNA replication

For DF-1 and MDCK cell experiments, 12-well plates were seeded with 3×105 cells per well 24 h prior to infection. For NHBE cells, cells were cultured at an air-liquid interface as previously described47. Cell surfaces were washed three times with PBS prior to inoculation. Triplicate wells were then inoculated with increasing doses of VAR virus, plus 0.005 PFU per cell of WT virus in DF-1 and MDCK cells or 0.05 PFU per cell of WT virus in NHBE cells. VAR viruses used were GFHK99 VAR2, MaMN99 VAR, NL09 VAR, MaMN99-GFHK99-PA VAR, dkHK78 VAR, and QaHK88 VAR. After 55 minutes at 37°C, inoculum was aspirated, cells were washed three times with PBS and 1 ml per well virus medium was added. Media was exchanged for ammonium chloride-containing media 3 h later. At 12 h post-infection, virus media was removed and cells were harvested using RNAprotect Cell Reagent (Qiagen). RNA was extracted using RNeasy columns (Qiagen) and then reverse transcribed with universal influenza primers66 and Maxima RT per protocol instructions. Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) was performed on the resultant cDNA. For GFHK99 virus, QX200™ ddPCR™ EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad) was used with a combination of PB2, M, and NS primers specific for the GFHK99 WT virus (final primer concentration of 200 nM) (Supplementary Table 3). For MaMN99, MaMN99-Anhui-PA, MaMN99-GFHK99-PA, dkHK78, QaHK88 and NL09 viruses, QX200™ ddPCR™ Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad) was used with NP specific primers and probes (Supplementary Table 3).

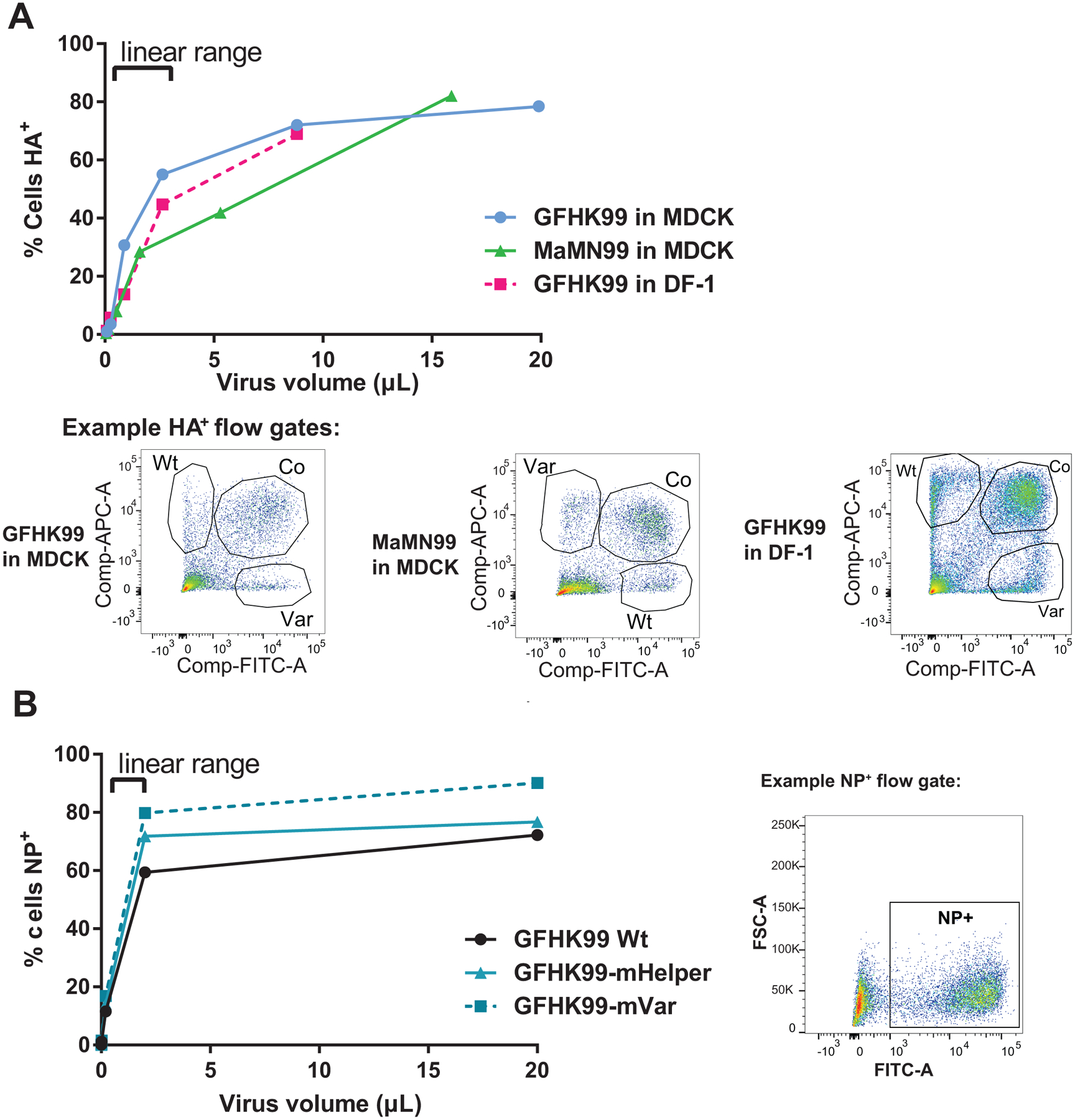

Strand-specific quantification of viral RNA species over time

Viruses used for this experiment were the same GFHK99 WT/VAR1 or MaMN99 WT/VAR virus mixtures used to measure reassortment, but in this case each mixture was considered as a single virus population (i.e. the RT ddPCR assay outlined below to quantify viral m/vRNA does not differentiate between WT and VAR genotypes). To ensure viral genomes were supplied as low or single copies, a dose of 0.5 RNA copies per cell was used for low MOI infection. RNA copy numbers of virus stocks were determined by ddPCR targeting at least four segments (mean values were used). For the high MOI dose, we used 3.0 HA-expressing units per cell, as determined by flow cytometry (Extended Data Figure 10). This measure of infectivity gives a functional readout for polymerase activity, and therefore ensures the vast majority of cells carry an active viral polymerase. HA-expressing units per mL was determined by counting HA+ cells by flow cytometry in the relevant cell type. Specifically, cells were infected with serial dilutions of virus under synchronized, single cycle conditions. At 24 h post-infection, cells were harvested and flow cytometry was performed targeting His and HA epitope tags. HA expressing units per mL for each virus / cell combination was calculated based on the linear range of %HA+ cells plotted as a function of volume of virus added to cells67 (Extended Data Figure 10).

12-well plates were seeded with 2×105 cells per well of MDCK or DF-1 cells and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Synchronized, single-cycle infection conditions were used, as described above. Chilled virus was added at a volume of 125 μL per well. At 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 h post-infection, virus medium was aspirated and cells were harvested using 400 μL of RNAprotect Cell Reagent (Qiagen). RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNAeasy Mini kit. Two reverse transcription reactions per sample were set up with primers targeting mRNA or vRNA of the NS segment, each containing different nucleotide barcode tags (Supplementary Table 4). Maxima RT was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions and combined with 300 ng MDCK or 150 ng DF-1 RNA. Absolute copy number of cDNA was determined by ddPCR. Forward and reverse primers for vRNA or mRNA of NS at a total concentration of 200 nM were combined with diluted cDNA and QX200™ ddPCR™ EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences were based on the method of Kawakami et al.68 and are given in Supplementary Table 4. Thermocycler protocol was 95°C for 5 min, [95°C for 30s, 57°C for 60s] repeat 40x, 4°C for 5 min, 90°C for 5 min, 4°C hold. Copy number was normalized to RNA input to give final results in units of copy number per ng RNA. We did attempt to measure cRNA in this assay but found that primers designed to be specific for cRNA cross-primed on viral mRNA.

Single-cell mRNA sequencing

For this assay, viruses were titered in DF-1 cells using flow cytometry with anti-NP antibody. DF-1 cells were used because they give more sensitive detection of GFHK99 virus infection than MDCK cells. Cells were infected with serial dilutions of virus under synchronized, single-cycle conditions. At 24 h post-infection flow cytometry was performed targeting NP: cells were processed with the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Kit (catalog no. 554714) and stained with anti-NP antibody (Abcam, clone 9G8, catalog no. ab43821) followed by donkey anti-Mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen catalog no. A-21202). NP expression units per were calculated based on the linear range of % cells NP+ plotted as a function of volume of virus added to cells67 (Extended Data Figure 10).

To perform single-cell mRNA sequencing, MDCK and DF-1 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 5×105 cells per well. At 24 h post seeding, cells were infected with synchronized, single cycle conditions. In the first experiment, MDCK or DF-1 cells were inoculated with GFHK99 WT virus at an MOI of 0.07, 0.2, 0.6, or 1.8 NP units per cell. In the second experiment, MDCK or DF-1 cells were inoculated with a 1:1 ratio of GFHK99 WT virus and GFHK99 mVAR1 virus that amounted to a MOI of 0.02, 0.07, 0.2 or 0.6 NP units per cell. GFHK99 mVAR2 virus was added to MDCK and DF-1 cell infections at MOIs of 1 PFU per cell and 0.1 PFU per cell, respectively. Infected cells were incubated for 8 h at 37°C. Culture media was then aspirated and cells washed once with 1X PBS. Cells were then trypsinized with 200 μL of 0.25% Trypsin EDTA until all cells came off the plate and were mono-dispersed. To each well, 0.5 mL of virus medium was added and replicates were pooled (2 wells per MOI). Cells for each sample were counted. Samples were spun at 150 rcf for 3 minutes and washed with 0.5 mL of 1X PBS/0.04% BSA. Washings were performed two more times. Finally, cells were resuspended with 1X PBS/0.04% BSA to give 7 × 105 cells per mL. Preparation for single-cell transcriptomic sequencing followed the protocol for 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell platform.

Analysis of viral transcripts from single cells was performed with the sequencing data from all experiments using Cell Ranger software. Briefly, the Cell Ranger software assigns each read to individual cells and transcripts based on two sets of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) that are ligated prior to amplification. This approach allows the quantification of amplification bias at both the cellular and transcript levels. The first step of the analytical workflow was to map the reads to concatenated transcriptomes of GFHK99 virus with the transcriptomes of dog or chicken to analyze MDCK and DF-1 cell infections, respectively. Protein coding regions for the dog and chicken transcriptomes were identified in the GTF file associated with genome builds CanFam3.1.98 (NCBI accession number GCA_000002285.2) and GRCg6a (NCBI accession number GCA_000002315.5), respectively, while GFHK99 virus coding regions were extracted from the reverse-complement sequences of the GFHK99 strains. The aligned sequencing data is available on the GEO database with the accession number GSE135553. Cell Ranger output in the form of gene and barcode counts were then analyzed in R using the packages CellrangerRkit and Seurat. To account for the issue of cellular lysis, which can allow uninfected cells to acquire viral RNA from the supernatant and thus appear infected, a preliminary analysis was conducted to exclude cells that were likely false positives. This analysis was informed by the reasoning that 1) contaminated cells were likely to contain less viral RNA than truly infected cells, and 2) the amount of viral RNA present in contaminated cells should be less consistent than the amount present in truly infected cells. Within each infection, the proportion of each cell’s transcriptome that was comprised of viral RNA was calculated, and cells were ordered according to this proportion so that the marginal gain in % viral RNA from one cell to the next could be calculated. Excluding cells with no marginal gain (indicating two cells with the same % viral RNA), the marginal gain vs. % viral RNA was plotted for each infection, which showed that this marginal gain is initially a rapidly decreasing function of % viral RNA. The first local minimum of a local regression was derived for each infection, to determine the point at which marginal gain became more consistent and less affected by % viral RNA, and cells with % viral RNA below that threshold were excluded from further analysis (Extended Data Figure 5). To enable comparisons between samples, the median number of UMIs per cell was calculated for each infection, and the UMI counts of each cell within that infection were normalized to this median value (e.g. if the total number of UMIs in a cell was 50% of that detected in the median cell, all of its UMI counts were multiplied by 2). The number of viral RNA transcripts per cell was then calculated and log10-transformed.

Single-cell sorting assay for measurement of PP values

Segment-specific PP values were determined as previously described for influenza A/Panama/2007/99 (H3N2) virus8, and as follows. 4×105 MDCK cells were seeded into each well of a 6-well dish. 24 h later, cells were washed 3x with PBS and inoculated with 0.018 PFU per cell of GFHK99 WT virus and 1 PFU per cell of GFHK99 VAR2 virus in 250 μL of PBS. Virus was allowed to attach at 37°C for 1 h. Inoculum was then removed and cells were rinsed 3x with PBS and 2 mL of virus medium was added to the well. After 1 h at 37°C, medium was removed and cells were washed 3x with PBS and harvested by addition of Cell Dissociation Buffer (Corning). Cells were resuspended in complete medium and washed 3x with 2 mL FACS buffer (2% FBS in PBS). A final resuspension step was performed in PBS containing 1% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, and 0.1% EDTA. Cells were strained through a cell strainer cap (Falcon) and sorted on a BD Aria II cell sorter. Gating was performed to remove debris and multiplets and one event per well was sorted into each well of a 96-well plate containing MDCK monolayers at 30% confluency in 50 μl virus medium supplemented with 1 μg per mL TPCK-treated trypsin. Following the sort, an additional 50 μl of virus medium plus TPCK-treated trypsin was added to each well and plates were centrifuged at 1,800 rpm for 2 minutes to promote cell attachment. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h to allow propagation of virus from the sorted cell.

RNA was extracted from infected cells in the 96-well plate using a ZR-96 Viral RNA Kit (Zymo Research) per manufacturer instructions. Extracted RNA was converted to cDNA using universal influenza primers66 and Maxima RT according to manufacturer instructions. After conversion, cDNA was diluted 1:4 with nuclease-free water and used as template (4 μL per reaction) for segment-specific qPCR using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad) in 10 μl reactions, with 200 nM final primer concentration. Primers employed targeted each segment of GFHK99 WT virus, as well as the PB2 and PB1 segments of GFHK99 VAR2 virus. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Given the MOI of GFHK99 WT virus used in the experiments, an appreciable number of wells are expected to receive two or more viral genomes, and so a mathematical adjustment is needed to estimate the probability of each genome segment being delivered by a single virion. Using the relationship between MOI and the fraction of cells infected from Poisson statistics, i.e., f = 1 – e–MOI, the probability of the ith segment being present in a singly infected cell, or PP,i can be calculated from the 96-well plate using the following equation:

where A is the number of VAR2+ wells, B is the number of WT+ wells (containing any WT segment), and Ci is the number of wells positive for the WT segment in question. Wells that were negative for VAR2 virus segments were excluded from analysis.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Level of infection achieved in single cycle growth assays, as determined by flow cytometric detection of HA protein.

Triplicate or duplicate wells of cells were harvested at 24 h post-infection and stained to detect surface expression of HA and HIS epitope tags. Panel A) corresponds to Extended Data Figure 2 A–C and Panel B) corresponds to Extended Data Figure 2 E–F. Lines connect the means of n=2 or n=3 replicate samples. C) Flow gating was performed by excluding cell debris and multiplet cells. Quadrant gates were used to quantify each population. Flow cytometry results are representative of those obtained in three independent experiments.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Increasing MOI increases viral productivity at sub-saturating, but not saturating MOIs.

Data relate to Figure 2. MDCK or DF-1 cells were infected under single-cycle conditions at a range of MOIs. Low MOI range is shown in panels (A) to (D) and high MOI range is shown in panels (E) and (F). As shown in Extended Data Figure 1, MOIs < 1 PFU/cell were found to be sub-saturating. Viral titers observed at the indicated MOIs are plotted against time post-infection for GFHK99 virus in MDCK cells (A), GFHK99 virus in DF-1 cells (B), MaMN99 virus in MDCK cells (C), NL09 virus in MDCK cells (D), GFHK99 virus in MDCK cells (E), and GFHK99 virus in DF-1 cells (F). Lines connect the mean values for technical replicates sampled at each time point.

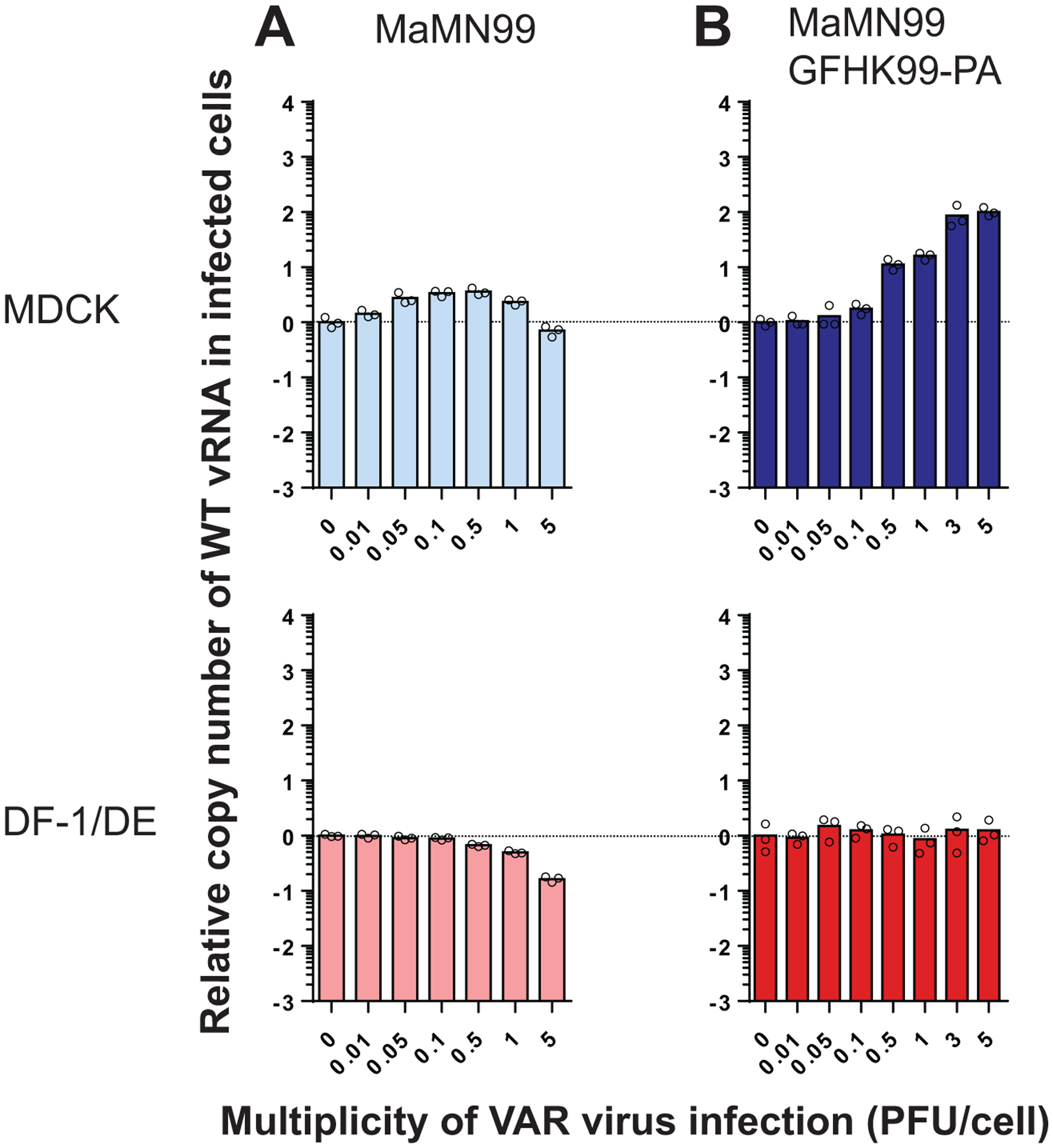

Extended Data Fig. 3. Introduction of the PA gene segment from GFHK99 virus into MaMN99 virus confers increased dependence on multiple infection for vRNA synthesis.

Cells were coinfected with WT virus and increasing doses of VAR virus. WT virus MOI was 0.005 PFU per cell. The fold change in WT vRNA copy number, relative to that detected in the absence of VAR virus, is plotted for MaMN99 virus (A) and MaMN99-GFHK99-PA virus (B). Bars represent the mean of n=3 replicate cell cultures per condition. Data shown in panel (A) are also shown in Figure 3. MaMN99 virus was tested in MDCK and DE cells; MaMN99 GFHK99-PA virus was tested in MDCK and DF-1 cells.

Extended Data Fig. 4. High multiplicity of infection is needed for robust GFHK99 polymerase activity in MDCK cells.

MDCK or DF-1 cells were infected with GFHK99 or MaMN99 virus at low (0.5 RNA copies per cell) or high (3 HA-expressing units per cell) MOI. NS segment vRNA and mRNA was quantified at the indicated time points (A–F). The average fold change from initial (t=0) to peak RNA copy number is plotted for low MOI infections (G) and high MOI infections (H). Mean and standard deviation are plotted for n=3 replicate cell cultures sampled sequentially. Significance was assessed by multiple unpaired, two-sided t-tests with correction for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method, with alpha = 5.0%. Each row was analyzed individually, without assuming a consistent SD.

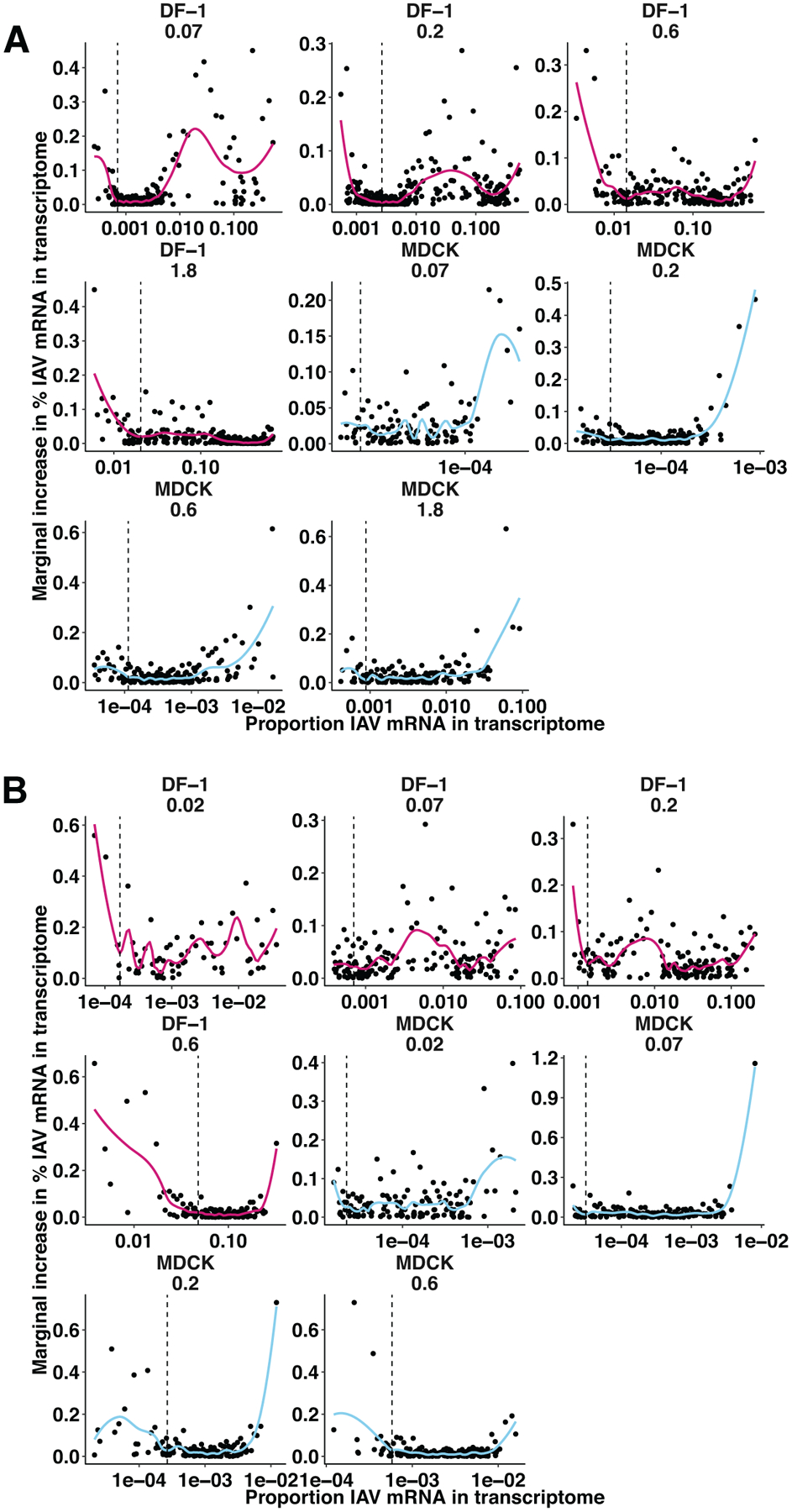

Extended Data Fig. 5. Preliminary analysis of single-cell mRNA sequencing data to exclude cells with viral mRNA that are likely uninfected.

A) Within each infection, cells in which viral RNA was detected were rank ordered by the proportion of their transcriptome that comprised viral RNA (% viral RNA), and the relative gain in % viral RNA from one cell to the next was plotted against the proportion of viral RNA in each cell. Local regression was performed separately for each infection, and the first local minimum of the resulting functions (indicated by dashed lines) indicated the point at which the marginal gain in % viral RNA was more consistent and less sensitive to the % viral RNA of the prior cell. Cells with % viral RNA values below this threshold were deemed falsely positive and considered uninfected for the analyses shown in Figure 5 and Extended Data Figure 6. Facets indicate individual infections, with lines colored by cell type (DF-1 = pink, MDCK = blue). B) The same analysis in panel A) was applied to the data from the second experiment, in which cells were co-inoculated with a 1:1 mixture of WT and mVAR1 viruses, as well as mVAR2 virus at an MOI of 0.1 PFU per cell in DF-1 cells, or 1.0 PFU per cell in MDCK cells. Only cells containing all eight mVAR2 segments were analyzed in this manner.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Validation of single-cell mRNA sequencing data.

(A, B, E) In the first single-cell sequencing experiment, DF-1 or MDCK cells were infected with GFHK99 WT virus at four different MOIs (0.07, 0.2, 0.6, 1.8 NP units per cell), and the transcriptomes of individual cells were sequenced using the 10x Genomics Chromium platform (n = 1,228 DF-1 cells, 645 MDCK cells, 1 sequencing replicate per infection condition). A) The total number of cells sequenced, infected, and containing PB2, PB1, PA, and NP segments are represented by the cumulative heights of the gray, light yellow, and dark yellow bars, respectively. Cells that were excluded by the analysis shown in Extended Data Figure 5 are contained within the gray bar. B) Each violin plot shows the full distribution of log10-transformed viral mRNA abundance, for all eight viral transcripts combined, in individual infected cells. Vertical lines represent the median of each distribution. The data are stratified by cell type (MDCK cells in blue, DF-1 cells in pink), MOI, and the presence of polymerase complex (light shading = cells missing PB2, PB1, PA, or NP; dark shading = cells in which PB2, PB1, PA and NP are all detected). The absence of a dark shaded distribution for MDCK cells at the lowest MOI is due to the absence of any cells in which all four of these segments were detected. (C, D, E) In the second single-cell sequencing experiment, DF-1 or MDCK cells were infected with GFHK99 WT and mVAR1 viruses at total MOIs of 0.07, 0.2, 0.6, 1.8 NP units per cell, and simultaneously with a constant dose of mVAR2 virus (n = 462 DF-1 cells, 671 MDCK cells, 1 sequencing replicate per infection condition). C) The total number of cells sequenced, containing all eight mVAR2 genome segments, and infected with either WT or mVAR1 virus are represented by the cumulative heights of the gray, light orange, and dark orange bars, respectively. As in panel (A), cells that were deemed falsely positive are contained within the gray bar. D) Distributions of viral UMIs per cell are shown separately for WT (bottom of each cell-MOI pair) and mVAR1 (top of each cell-MOI pair). Vertical lines represent the median of each distribution. As expected, no significant difference was detected between WT and mVAR1 transcript levels (p = 0.061, linear mixed effects model). E) The distributions of total UMIs detected per cell are shown for each cell type, MOI, and infection type, from both experiments. Vertical lines represent the median of each distribution.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Alignment of MaMN99 and GFHK99 virus PA and PA-X amino acid sequences.

Sequences and functional domains of the PA protein are displayed in panel (A), and those of the PA-X protein are shown in panel (B). N-ter = the N-terminal endonuclease domain69; C-ter = C-terminal domain69; X-ORF = the 61 amino acid region of PA-X encoded in frame 2 of the PA gene37; Active site = the active site of the endonuclease39; Dim. Loop = dimerization loop important for formation of polymerase dimers40; Site 1 and Site 2 = sites mediating the interaction of PA with cellular Pol II C-terminal domain70.

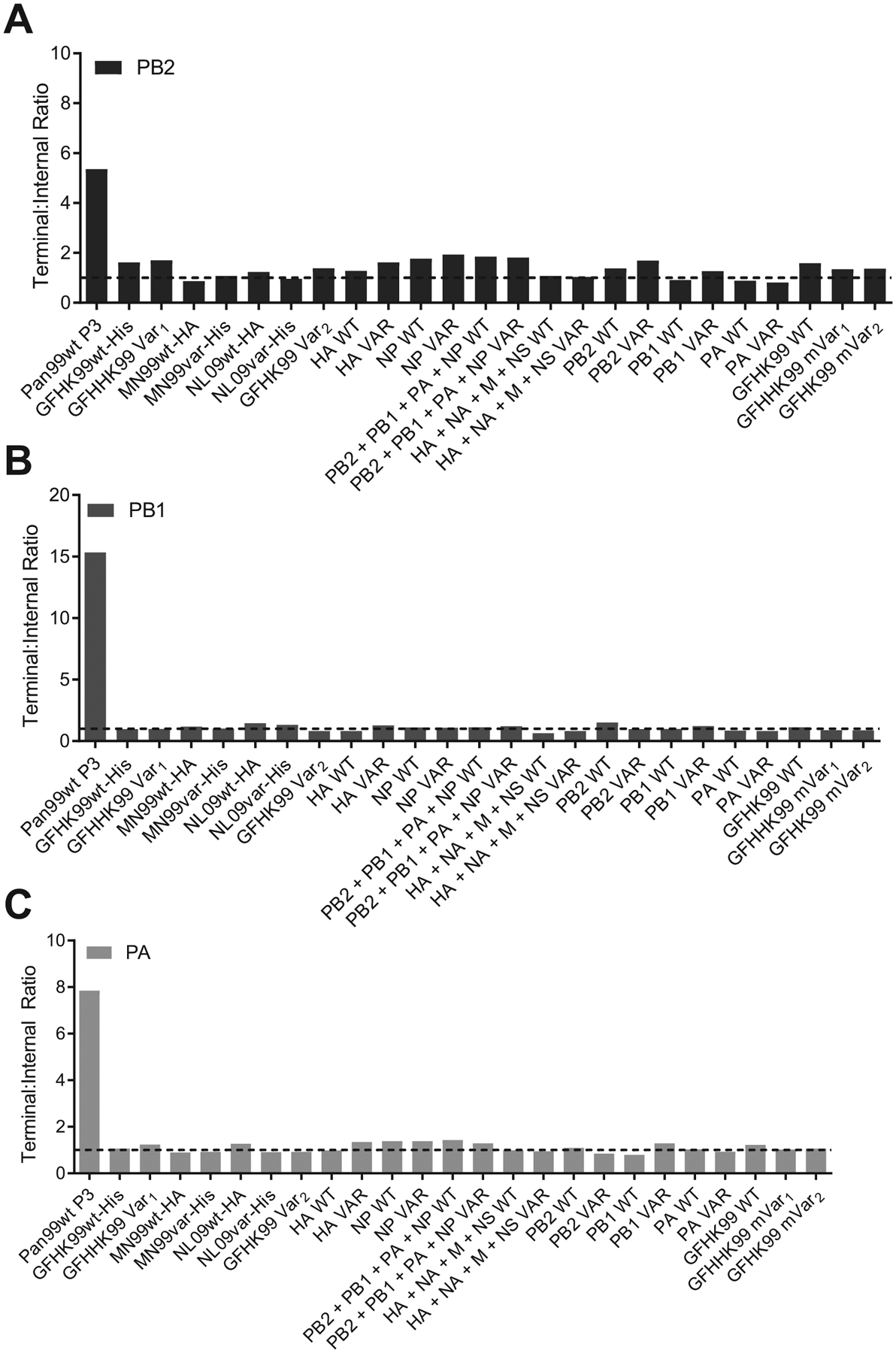

Extended Data Fig. 8. Quantification of defective interfering RNA content in virus stocks.

Defective interfering RNA content for A) PB2, B) PB1 and C) PA segments was determined by ddPCR using primer pairs targeting terminal and internal portions of each polymerase gene segment to determine their absolute copy number and produce a ratio of terminal:internal copies. All virus stocks used in this study contained low DI content (terminal:internal ratio less than or equal to 2). A DI-rich control virus, Pan99wt P3 (A/Panama/2007/99 [H3N2]), is included for comparison. This virus stock was passaged three times in MDCK cells at high MOI. For the MaMN99-GFHK99 chimeric viruses, the segments derived from GFHK99 virus are listed in place of the full strain names.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Example gating for flow cytometry to evaluate HA positive cell numbers.

Plots shown were generated in the course of experiments reported in Figure 1 and are representative of results obtained in at least three independent experiments. Following staining for cell-surface HA protein: 1) A population of cells was selected by gating out cell debris by SSC-A vs FSC-A. 2) Multiplets were excluded by gating for single cells in SSC-H vs SSC-W. 3) Populations of infected cells were gated based on expression of the appropriate epitope tag.

Extended Data Fig. 10. Titration of virus stocks for HA expressing units and NP expressing units by flow cytometry.

A) The doses to be used in RNA kinetics studies shown in Extended Data Figure 4 were determined via flow titration of HA-expressing units in the relevant cell lines. GFHK99 and MaMN99 virus mixtures were titrated in MDCK and DF-1 cells to calculate HA-èxpressing units/mL for each virus-cell combination. Serial dilutions of virus were used to infect cells under synchronized, single cycle conditions. Cells were harvested at 24 h post infection and stained for epitope tags. Data within the linear range were used to calculate the viral titer. B) GFHK99 viruses used in mRNA sequencing experiments shown in Figure 5 were titered in DF-1 cells. DF-1 cells are more permissive to infection and thus give more sensitive detection of infectious virus compared to MDCK cells. As the virus strains used did not contain epitope tags, virus detection was accomplished through cell permeabilization and detection of the viral NP protein. Data within the linear range were used to calculate viral titers. Representative flow plots show gates used following exclusion of cell debris and doublets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank David Stallknecht (University of Georgia) for providing the A/mallard/MN/199106/99 (H3N8) biological isolate. We are grateful to Jessica Shartouny for helpful discussion and preparation of Extended Data Figure 7. We thank Hui Tao, Shamika Danzy, and Ginger Geiger for technical assistance. This work was funded in part by NIH R01 AI127799 (to ACL and DRP); NIH/NIAID Centers of Excellence in Influenza Research and Surveillance (CEIRS), contract numbers HHSN272201400004C (to ACL and GST) and HHSN272201400008C (to DRP). Additional funds were provided by the Georgia Research Alliance and the Georgia Poultry Federation (to DRP) and NIH/NIAID Genomic Centers for Infectious Diseases (GCID), Award Number U19 AI110819 (to GST). KLP was supported by T32 AI10669.

Footnotes

Data availability

10x Genomics single-cell sequencing data is available on the GEO database with the accession number GSE135553. Other data are included as Source Data or are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Code used for 10x Genomics analysis is available at: https://github.com/njacobs627/GFHK99_Multiplicity. Code used to run the agent-based model on influenza A virus reassortment was reported previously7,8 and is also available at https://github.com/njacobs627/GFHK99_Multiplicity.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Leeks A, Sanjuan R & West SA The evolution of collective infectious units in viruses. Virus Res 265, 94–101, doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2019.03.013 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooke CB Population Diversity and Collective Interactions during Influenza Virus Infection. J Virol 91, doi: 10.1128/JVI.01164-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanjuan R Collective Infectious Units in Viruses. Trends Microbiol 25, 402–412, doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.02.003 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooke CB, Ince WL, Wei J, Bennink JR & Yewdell JW Influenza A virus nucleoprotein selectively decreases neuraminidase gene-segment packaging while enhancing viral fitness and transmissibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 16854–16859, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415396111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooke CB et al. Most influenza a virions fail to express at least one essential viral protein. J Virol 87, 3155–3162, doi: 10.1128/JVI.02284-12 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun J & Brooke CB Influenza A Virus Superinfection Potential Is Regulated by Viral Genomic Heterogeneity. MBio 9, doi: 10.1128/mBio.01761-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonville JM, Marshall N, Tao H, Steel J & Lowen AC Influenza Virus Reassortment Is Enhanced by Semi-infectious Particles but Can Be Suppressed by Defective Interfering Particles. PLoS Pathog 11, e1005204, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005204 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs NT et al. Incomplete influenza A virus genomes occur frequently but are readiliy complemented during localized viral spread. Nature Communications (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nayak DP Defective interfering influenza viruses. Annu Rev Microbiol 34, 619–644, doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.34.100180.003155 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Magnus P Incomplete forms of influenza virus. Adv Virus Res 2, 59–79 (1954). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooke CB Biological activities of ‘noninfectious’ influenza A virus particles. Future Virol 9, 41–51, doi: 10.2217/fvl.13.118 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Timm C, Gupta A & Yin J Robust kinetics of an RNA virus: Transcription rates are set by genome levels. Biotechnology and bioengineering 112, 1655–1662, doi: 10.1002/bit.25578 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulle M et al. HIV Cell-to-Cell Spread Results in Earlier Onset of Viral Gene Expression by Multiple Infections per Cell. PLoS Pathog 12, e1005964, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005964 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanjuán R & Thoulouze M-I Why viruses sometimes disperse in groups?(†). Virus Evol 5, vez014–vez014, doi: 10.1093/ve/vez014 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sigal A et al. Cell-to-cell spread of HIV permits ongoing replication despite antiretroviral therapy. Nature 477, 95–98, doi: 10.1038/nature10347 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webster RG, Hinshaw VS, Bean WJ Jr., Turner B & Shortridge KF Influenza viruses from avian and porcine sources and their possible role in the origin of human pandemic strains. Dev Biol Stand 39, 461–468 (1977). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright PF, Neumann G & Kawaoka Y in Fields Virology Vol. 1 (ed D. M & Howley Knipe PM) 1691–1740 (Lippincott-Raven, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM & Kawaoka Y Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev 56, 152–179 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webster RG, Shortridge KF & Kawaoka Y Influenza: interspecies transmission and emergence of new pandemics. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 18, 275–279, doi:S0928–8244(97)00058–8 [pii] (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taubenberger JK & Morens DM 1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Emerg Infect Dis 12, 15–22 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viboud C, Miller M, Olson D, Osterholm M & Simonsen L Preliminary Estimates of Mortality and Years of Life Lost Associated with the 2009 A/H1N1 Pandemic in the US and Comparison with Past Influenza Seasons. PLoS Curr, RRN1153, doi:k/−/−/35hpbywfdwl4n/8 [pii] (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall N, Priyamvada L, Ende Z, Steel J & Lowen AC Influenza virus reassortment occurs with high frequency in the absence of segment mismatch. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003421, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003421 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez DR et al. Role of quail in the interspecies transmission of H9 influenza A viruses: molecular changes on HA that correspond to adaptation from ducks to chickens. J Virol 77, 3148–3156, doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.5.3148-3156.2003 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell AB, Trapnell C & Bloom JD Extreme heterogeneity of influenza virus infection in single cells. Elife 7, doi: 10.7554/eLife.32303 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]