Abstract

Bardet–Biedl syndrome (BBS) is a rare pleiotropic inherited disorder known as a ciliopathy. Kidney disease is a cardinal clinical feature; however, it is one of the less investigated traits. This study is a comprehensive analysis of the literature aiming to collect available information providing mechanistic insights into the pathogenesis of kidney disease by analyzing clinical and basic science studies focused on this issue. The analysis revealed that the syndrome is either clinically and genetically heterogenous, with 24 genes discovered to date, but with 3 genes (BBS1, BBS2, and BBS10) accounting for almost 50% of diagnoses; genotype–phenotype correlation studies showed that patients with BBS1 mutations have a less severe renal phenotype than the other 2 most common loci; in addition, truncating rather than missense mutations are more likely to cause kidney disease. However, significant intrafamilial clinical variability has been described, with no clear explanation to date. In mice kidneys, Bbs genes have relative low expression levels, in contrast with other common affected organs, like the retina; surprisingly, Bbs1 is the only locus with basal overexpression in the kidney. In vitro studies indicate that signalling pathways involved in embryonic kidney development and repair are affected in the context of BBS depletion; in mice, kidney disease does not have a full penetrance; when present, it resembles human phenotype and shows an age-dependent progression. Data on the exact contribution of local versus systemic consequences of Bbs dysfunction are scanty and further investigations are required to get firm conclusions.

Keywords: Bardet–Biedl syndrome, ciliopathies, genetics, kidney disease, physiopathology

Bardet–Biedl syndrome (BBS) is a rare inherited disorder with an estimated incidence of 1 in 160,000 live births. Primary features include rod–cone dystrophy, postaxial polydactyly, obesity, learning disabilities, and renal anomalies.1 Clinical variability is high among patients, and several secondary features have been described, such as behavioral abnormalities, ataxia, hypertonia, orodental anomalies, heart defects, and Hirschsprung disease.2 The diagnosis is established by clinical findings, based on criteria established by Beales et al.2 Considering that several clinical manifestations occur over time, the clinical picture is rarely complete during infancy, making difficult to get an early diagnosis. Beales et al. showed that the average age at diagnosis was 9 years, while the mean age at symptoms onset was 3 years.2 Typically, the natural history is characterized by normal prenatal development. When present, prenatal abnormalities consist of polydactyly and less commonly genitourinary anomalies.3,4 During infancy, speech delay, poor coordination, and other developmental delays are quite common, and 70%–86% of patients develop obesity by 3 years of age.2 Visual impairment occurs much earlier than nonsyndromic retinal degeneration conditions; patients present with night blindness when they are 5–10 years of age and show progressive visual impairment during the following decades.1,2 While polydactyly/syndactyly, retinal dystrophy, and obesity have a quite high penetrance, kidney dysfunction is much more variable. Functional renal abnormalities range from urinary concentrating defect to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).5, 6, 7, 8, 9 The largest BBS cohort study has shown that 31% and 42% of pediatric and adult subjects, respectively, had stage 2–5 chronic kidney disease (CKD).10 Kidney structural abnormalities were even more common and included cysts, fetal lobulation, calyceal clubbing/blunting, kidney dysplasia, horseshoe kidneys, and vesicoureteral reflux. ESRD has been described in 8% of patients.10 Children that reached ESRD did so before 5 years of age, and children that developed any stage of CKD were diagnosed before 10 years of age.10 The others may either develop CKD during adulthood or have stable kidney function. It is not excluded that kidney disease progression may be affected by the combination of structural abnormalities and common risk factors, such as obesity and hypertension, which are more common in patients with BBS than in the general population.11

Genetics of BBS

Traditional linkage analysis conducted on Bedouin families led to the identification of the first chromosomal disease locus (BBS2).12 Soon after, a second locus (BBS1) was described, through a genome-wide scan of 31 North American families.13 Subsequent studies identified the third and fourth loci (BBS3 and BBS4).14,15 At least 6 loci were mapped when the first BBS gene was discovered.16 Given the clinical analogies between BBS and McKusick–Kaufman syndrome, the investigators hypothesized that the gene causing McKusick–Kaufman syndrome would also cause BBS.16 Notably, several other BBS genes were later implicated in other ciliopathies and vice versa; for example, CEP290/NPHP6 mutations are associated with BBS and other ciliopathies, such as Meckel–Gruber, Joubert, Senior–Løcken, nephronophtisis, and Leber congenital amaurosis syndromes.11 The advent of next-generation sequencing has led to the discovery of an increasing number of pathogenic loci; to date, up to 24 genes have been described10,17, 18, 19 (Supplementary Table S1). BBS1, BBS2, and BBS10 are the most commonly mutated genes and account for almost 50% of diagnoses. Some genes have greater ethnic specific frequency than others and some genetic variants have shown clusterization. In the Northern European population, BBS1M390R and BBS10 C91LfsX5 are the most common alleles, while Middle Eastern and North African individuals have a high frequency of BBS4, BBS5, and TTC8 mutations.20 Traditionally, BBS is considered an autosomal recessive condition; given the intrafamilial clinical variability, an oligogenic inheritance has been suggested.21 Zaghloul et al.22 provided some evidence supporting the hypothesis that BBS could be inherited as a multilocus disease.22 This hypothesis did not find confirmation in subsequent studies,23 and to date homozygous mutations are considered sufficient to determine the syndrome. Whether additional variants may affect the severity of clinical presentation remains a possibility.

Correlation Between Genotype and Renal Phenotype in Patients With BBS

The accurate estimation of genotype–phenotype correlation requires large sample size,24 which limits the possibilities to get firm conclusions in rare disorders. This analysis of patients with BBS is further hampered by high genetic heterogeneity. Some case studies and a recent metanalysis have addressed this issue. Kidney disease is undoubtedly highly variable.3,25,26 Independent studies indicate that patients with BBS1 mutations have a mild renal (and extrarenal) phenotype.27, 28, 29 The reason is unclear. The high prevalence of the missense BBS1M390R, a “hypomorphic” variant, may impact this finding; however, in vitro studies suggest that the absence of BBS1 has a minimal effect on the formation and the stability of the BBSome, the multiprotein complex consisting of BBS1 and other BBS proteins.30 Conversely, some studies suggest that patients carrying mutations in chaperonin-like proteins, as BBS6, BBS10, and BBS12, have a more severe renal phenotype. Imhoff et al.31 analyzed a French cohort consisting of 33 patients with BBS, showing that those harboring mutations in these 3 genes displayed more severe kidney disease than patients with BBSome component defects.31 A subsequent study conducted in 350 patients with BBS confirmed that patients with BBS10-mutated disease are more likely to develop CKD than patients with BBS1-mutated disease, especially in the presence of truncating mutations.32

A recent metanalysis has assembled the data of 85 of the most relevant published articles describing both the genotype and the phenotype of patients with BBS, which has led to the creation of the largest cohort, accounting for 899 individuals.33 The study concluded that: 1) renal anomalies have a higher incidence in patients with BBS2, BBS7, and BBS9 (the core of the BBSome) mutations compared with other BBSome components (BBS1, BBS4, and BBS8/TTC8); 2) patients with mutations in BBS1 have a lower incidence of renal anomalies than the other most common BBS genes, namely BBS2 and BBS10, and that this effect is independent on the high incidence of the M390R variant; and 3) patients with BBS3/ARL6 mutations have a low rate of kidney disease and cognitive impairment. The study also confirmed previous analyses suggesting that truncating mutations are significantly correlated with higher disease severity than missense mutations.

BBS Expression Profiles in Organs and Tissues

Data on the spatiotemporal expression pattern of BBS genes are scanty.

Recently, Patnaik et al.34 examined the expression profile of Bbs genes in mouse at baseline and after specific Bbs gene depletion.34 In this study, the authors analyzed the relative mRNA abundance of either Bbs1, Bbs2, Bbs4, Bbs5, Bbs7, Bbs8, Bbs9, or BBIP10/Bbs18, which are known to form a complex named BBSome, and of Bbs6, Bbs10, and Bbs12, encoding for chaperonin-like proteins. Interestingly, BBSome components were differentially expressed among tissues. Their expression pattern was similar in the brain and the kidney, showing no significant difference compared with the internal standard, except for Bbs1, the only overexpressed gene in the kidney. In contrast, most BBSome components were overexpressed in the retina.35 The expression levels of chaperonine-like Bbs proteins were less variable across tissues. Bbs10 and Bbs6 were constant in all analyzed tissues, while Bbs12 showed lower expression in brain and kidney and higher expression in the spleen, oviduct, and retina. In mice lacking Bbs8, one of BBSome components, a significant reduction of most BBSome mRNA levels was observed in several organs, including the retina and the heart. Interestingly, Bbs7 expression was downregulated in all tissues analyzed and it was the only BBSome component downregulated in the kidney and brain. In contrast, Bbs8 depletion had a minor effect on the expression levels of chaperonin-like proteins. Of note, Bbs8 depletion resulted in a similar behavior of BBSome components in the kidney and brain and of chaperonin-like transcripts in the brain and retina, respectively. Knocking down Bbs6 in mice did not have a significant effect on either BBSome and chaperonin-like protein transcription. The overall study indicated that Bbs genes show a relative low expression in the kidney at baseline and that the depletion of Bbs8 resulted in the downregulation of other Bbs components in the retina but not in the kidney.

Previous studies analyzed dynamic changes of Bbs expression during different developmental stages in mice. Bbs6 showed a prominent expression during embryogenesis, especially in the heart, brain, retina, limb buds, and neural tube. The analysis of protein levels showed a detection in ciliated epithelial cells of renal tubules, retina, and olfactory epithelia.36 Similarly, Bbs4 protein was detectable during embryogenesis, at embryonic day 16, in the pericardium and in the epidermal layer surrounding the digits, while in adult mice it localized to the hippocampus and dentate gyrus, the epithelial cells of bronchioles, the retina, and chondrocytes.37 Nishimura et al.38 performed a Northern blot analysis showing that the Bbs2 expression profile was detectable early during mouse embryogenesis; in adult mice it showed a variable abundance among tissues, with a prevalence in the heart, brain, kidney, testes, and eye. Similar findings were described for Bbs8 expression, with high levels during embryogenesis. At embryonic days 14 and 16 it was detected in the telencephalon, the developing ependymal cell layer, and the olfactory epithelium. In adult mice, Bbs8 localized to maturing spermatids, the retina, and bronchial epithelial cells.39 The wide expression profile of Bbs in embryonic mice suggests a role in organ development; in accordance with this finding, several structural abnormalities, with a variable penetrance, have been described in humans and mice. However, it is hard to interpret whether organs that are rarely affected, such as the heart, show a high genetic expression in embryos.

Subcellular Localization of BBS Proteins

The physiological role of BBS proteins has remained unclear for a long time. In 2003, Ansley et al.39 for the first time localized the product of BBS genes to ciliated structures. In this study, they showed that Bbs8 localized to the connecting cilium of the retina and to the columnar epithelial cells in the lung.39 One year later, Kim et al.37 showed that Bbs4 localized to the centriolar satellites of centrosomes and basal bodies of the primary cilia (PC) region; a similar localization was later found for Bbs5, in mouse and Caenorhabditis elegans.40 The centrosome is the main microtubule-organizing center of mammalian cells. It is composed of mother and daughter centrioles and of a surrounding protein matrix. In proliferating cells, centrosomes coordinate spindle pole formation and cytokinesis; in quiescent cells, the centrosome migrates toward the cell surface, where the mother centriole forms the basal body, consisting of the nucleation site of the PC.41 However, the presence of a PC is incompatible with cell division, presumably because the basal body must be released from the cell surface to play its role in mitosis. Since the first studies of Ansley et al.39 and Kim et al.,37 several BBS proteins have been localized to the basal body of the PC.

MKKS/BBS6 was found at the PC level in different mammalian cell lines, including human HeLa, murine inner medullary collecting duct, and murine embryonic fibroblasts, with a cell cycle–dependent localization.36 BBS2, BBS5, and BBS13/MKS1 showed colocalization with basal body markers, as gamma-tubulin.42 Interestingly, several BBS proteins, especially BBSome components, such as BBS1, BBS4, and BBS5, have also been detected along the PC.43 As with BBS6, other chaperonin-like BBS proteins, BBS10 and BBS12, showed centriolar/basal body localization in different cell lines, while they have never been detected along the PC.44 As ciliogenesis and the cell cycle are intimately linked, it is not excluded that Bbs proteins may play a role in mediating the cross-talk between both biological processes and to ensure the correct switch between them.

Further studies demonstrated an extra basal body localization of BBS proteins. BBS8 and BBS9 showed a cellular peripheral distribution resembling actin linear filament in nonconfluent murine inner medullary collecting duct cells, even though no colabeling with F-actin was detected.45 Bbs2 localized to actin-rich structures in developing hair cells in the cochlea and epithelial cells of the choroid plexus.46 Recent studies have shown a nuclear localization of BBS7 in murine embryonic fibroblast cells.47 In addition, Bbs4 product has been localized to the endoplasmic reticulum during early adipogenensis differentiation, at either basal condition and after stressing conditions.48 Taken together, these studies indicate that BBS gene products have also extra–basal body/centrosome localization, suggesting possible extraciliary functions.

Putative Links Between BBS Defective Function and Kidney Disease

Defective Trafficking of Ciliary Proteins

BBS proteins participate to primary cilia-related functions. They have been shown to form 2 multiprotein complexes: the chaperonin complex and the BBSome, as stated above. The chaperonin complex together with CCT/TRiC chaperonins mediate BBSome assembly.49

The latter is a highly conserved complex whose main function is mediating vesicular trafficking of membrane proteins to the PC. Studies conducted in several BBS mouse models demonstrate that the depletion of Bbs does not significantly impact PC formation. In the retina, cilia formation is not impaired in several BBS-mutant mice, even though over time a progressive retinal degeneration with loss of photoreceptors has been described,50 suggesting that they are not required for global cilia assembly but are crucial for the regulation of cilia maintenance and, possibly, for the definition of PC ultrastructure. Also, in Bbs1M390R/M390R knock-in mice, a model mimicking the most common BBS1 mutation in humans, the outer segments of photoreceptors are initially present and then degenerate over time.35 Several studies addressed the effect of Bbs depletion on PC formation along the renal epithelium. Except for Bbs4 null mice, which display shorter PCs that become longer over time, studies conducted in several Bbs knockout (KO) mouse models show that PC is generally present in renal epithelial cells (Table 1).51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 Independent in vitro studies, however, show that Bbs10-, Bbs4-, Bbs6-, and Bbs9-depleted cell models show a reduction of the number of ciliated cells and of PC length.2,45,61

Table 1.

Renal and extrarenal phenotypes of murine models of Bardet-Biedl syndrome

| Murine models | Extrarenal phenotypes | Major renal histologic features | Renal tubular epithelial cells’ PC | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bbs4−/− mice | Obesity, retinal degeneration, and hypertension | Not described | The PC is present but has different length than control mice (shorter since day 7 of culture but longer between days 7 and 10) on immunocytochemistry and TEM analysis | Mokrzan et al.50 and Mykytyn et al.51 |

| Bbs4−/− mice | Obesity, metabolic syndrome, anosmia, perinatal lethality, male infertility, hydrometrocolpos, and neural tube defects | Tubular cystic lesions (data not shown) | Not described | Eichers et al.52 |

| Bbs2−/− mice | Obesity, retinal degeneration, liver lipids accumulation, and male infertility | Inflammatory infiltration and multiple cysts on hematoxylin and eosin staining of 5-mo-old mice | The PC is present but appears tapered compared with WT on TEM analysis | Nishimura et al.38 |

| Bbs6−/− mice | Obesity with hyperphagia and decrease of locomotory activity, hypertension, anosmia, male infertility, and social dominance defects | Not described | The PC is normal in number and size on TEM analysis in young mice | Fath et al.53 |

| Bbs4−/− mice | Previously described by Mykytyn et al.51 | Inflammatory infiltration in 12-wk-old mice and later onset of glomerular cysts | Not described | Guo et al.54 |

| Bbs2−/− mice | Previously described by Nishimura et al.38 | Inflammatory infiltration with no cysts in 12-wk-old and 40-wk-old mice | Not described | Guo et al.54 |

| Bbs1M390R/M390R mice | Obesity, elevated blood levels of leptin, retinal degeneration, male infertility, ventriculomegaly, thinning of cerebral cortex, reduction in size of the corpus striatum and hippocampus, and high heart rates without hypertension | Absence of renal cysts (data not shown) | Not described | Davis et al.55 |

| Bbs7−/− mice | Obesity, hyperleptinemia, retinal degeneration, ventriculomegaly, thinning of cerebral cortex, and reduction in size of the corpus striatum and hippocampus | No cystic lesions on histologic analysis | Normal in number and size on immunofluorescence studies | Zhang et al.56 |

| Bbs3−/− mice | Increase of fat mass without overt obesity, retinal degeneration, hydrocephalus, hypertension, and high heart rates | Not described | Normal in number and size on immunofluorescence studies | Zhang et al.57 |

| Bbs12−/− mice | Obesity with hyperphagia, hyperleptinemia, enhanced insulin sensitivity, and retinal degeneration | No detectable structural abnormalities on toluidine blue staining in 16-wk-old mice | Not described | Marion et al.58 |

| Bppi10−/− mice | Obesity with hyperphagia, retinal degeneration, and male infertility | Not described | Not described | Loktev and Jackson59 |

| Bbs10−/− mice | Obesity, hyperleptinemia, hyperphagia, and retinal degeneration | Reduction of glomerular basement membrane thickness, absence of primary and secondary podocyte structures, and intracytoplasmic inclusions in 12-wk-old mice | Normal in number and size on TEM analysis | Cognard et al.60 |

| Bbs10fl/fl; Cadh16-Cre+/− | Absent for molecular strategy | No abnormalities on TEM analysis in 12-week-old mice | Normal in number and size on TEM analysis | Cognard et al.60 |

PC, primary cilia; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; WT, wild type.

Many transmembrane proteins, including the G protein–coupled receptors Smoothened (Smo) and GPR161, involved in the sonic hedgehog signalling (Shh), require a functional BBsome for correct PC targeting.62 In cultured cells, the transcriptional output of the Shh pathway is in fact reduced30 and Smo levels in cilia are frankly decreased63 in cases of BBSome deficiency. Accordingly, Bbs gene depletion in mice resulted in cilia accumulation of Smo and Patched 1, the sonic hedgehog receptors, and showed a decreased Shh response.30 Shh signalling is a developmental pathway that plays a pivotal role in kidney organogenesis,64 and the deletion of Shh leads to several structural abnormalities.65 Recent studies have shown that the pathway is reactivated in adult mice after kidney injury.66 The signalling is also impaired in conditions of IFT27/Bbs19 and LZTFL1/BbS17 deficiency.67

Whether BBS proteins are required for the correct PC targeting of polycystins is unclear. Polycystins 1 and 2 are transmembrane proteins triggering intracellular signalling pathways in response to fluid flow changes.68 The proteins are the product of the major genes causing autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, the most common inherited renal cystic disorder. Su et al.69 showed that BBS1, BBS4, BBS5, and BBS8 interact with PC1, and that BBS1 depletion led to polycystin mislocalization. In contrast, Zhang et al.56 showed that while BBS7 is required for several proteins targeting the PC membrane, as dopamine D1 receptor, it is not for polycystins, opening a debate on the role of BBS proteins in their PC trafficking. This is only in part surprising. While autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and BBS share some similarities, given that are both associated with a dysfunctional PC, these disorders have several differences. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease is characterized by a typical cystic phenotype, with progressive enlarging kidneys leading to ESRD in adulthood; extrarenal disorders are generally much less significant than kidney disease. BBS is, instead, more similar to syndromic developmental disorders, as Senior–Løcken, Joubert, and Meckel–Gruber syndromes, with a less severe renal cystic phenotype and a more common fibrocystic kidney phenotype.70 Of note, syndromic recessive ciliopathies, such as BBS, show abnormal trafficking from and toward the PC, resulting in impaired PC structure, composition, and signalling. PC removal from kidney tubules resembled these last disorders, showing a cystic phenotype progressing with a slower rate than the Pkd1 model. Surprisingly, PC abrogation in Pkd1 and Pkd2 models blocked cyst growth, suggesting a multimodal pathogenesis of cystic disorders, which is presumably distinct between autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and other ciliopathies.70

Defective Extraciliary Trafficking and Proteosomal Activities

Recently, some studies have demonstrated extraciliary roles of BBS proteins, including cytoplasmic trafficking and proteasomal activities (Table 2).71, 72, 73 Interestingly, either Shh, Notch, and Wnt signalling are evolutionarily conserved signal transductions required for several embryonic organ developments in animals and are all regulated via proteasomal regulation.74,75 The aberration of these pathways in BBS models may be at least in part the result of proteosomal defects. Leitch et al.71 showed that Bbs1 and Bbs4 are required for delivering Notch receptors to the plasma membrane via endosomal trafficking. During embryonic kidney development, Notch establishes proximal tubular epithelial cell fate and cell type specification in the renal collecting system. In the adult kidney, Notch has low expression levels at steady state, while it is increased in several pathologic conditions.76 After binding its ligand, Notch receptor undergoes proteolytic clivage and the Notch intracellular domain translocates to the nucleus to regulate the transcription of downstream targets. Inactive Notch receptor undergoes endosomal sorting for either degradation or recycling to the plasma membrane.77 In their study, Leitch et al.71 showed that loss of Bbs1 or Bbs4 resulted in the upregulation of Notch signalling both in transgenic zebrafish Notch receptor cell line and in human cultured cells. The disruption of Bbs1 and Bbs4 led to the reduction of Notch receptor localization to the plasma membrane and to the PC, with a dramatic accumulation in late endosomes that overwhelmed lysosome capacity, leading to incomplete degradation. The impaired receptor recycling to the membrane, without disrupting endocytosis, resulted in increased accumulation to late endosomes, from where active intracellular domain may be produced, eventually increasing the signalling.71

Table 2.

List of biological functions of Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins

| Biological functions of BBS proteins | Description | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Ciliary trafficking | BBS1, BBS4, BBS5, and BBS7 mediate the trafficking of several GPCRs, including Smo and GPR161, to the PC; BBS1 and BBS3 target polycystin 1 and 2 to the PC | Zhang et al.,30 Berbari et al.,62 and Su et al.69 |

| Endosomal trafficking | BBS1 and BBS4 are required for delivering Notch receptor to the plasma membrane via endosomal trafficking | Leitch et al.71 |

| Cytoskeleton organization | BBS4, BBS6 and BBS8 regulate actin polymerization by modulation of RhoA activity; BBIP10/ BBS18 is required for cytoplasmic MT polymerization and acetylation | Hernandez-Hernandez et al.45 and Loktev et al.72 |

| Cell division | BBS4 and BBS6 depletion cause cytokinesis defects and produce multinucleate/multicentrosomal cells | Kim et al.36,37 |

| Regulation of proteasomal activity | BBS4 interacts with the proteosomal subunit RPN10BBS11/TRIM32, an E3 ubiquitin ligase promoting several target degradation | Zhang et al.30 and Gerdes et al.73 |

| ER stress response | BBS4 is localized to the ER and participates in UPR activation through regulation of ATF6α and IRE1α | Anosov and Birk48 |

| Regulation of gene expression | BBS7 enters the nucleus and interacts with the chromatin remodeler RNF2, regulating the transcription of its target genes; BBS1–6 and BBS9–11 possess NESs, suggesting a possible nuclear localization in mammalian cells | Gascue et al.47 |

ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GPCR, G protein–coupled receptor; MT, microtubule; NES, nuclear export signal; UPR, unfolding protein response.

BBS3 encodes the small Arf-like guanosine triphosphatase Arl6, which mediates BBSome recruitment to membranes via BBS1 interaction. This process precedes BBSome sorting of specific cargoes to cilia.43 BBS3 modulates Wnt signalling.78 The latter consists of a β-catenin–dependent (the canonical Wnt pathway) and 2 β-catenin–independent (the noncanonical Wnt/planar cell polarity [PCP] pathway and the calcium signalling pathway) signalling pathways. The canonical and PCP signalling pathways are the best studied in the context of kidney development and disease. Both pathways regulate kidney morphogenesis and are involved in kidney repair.79,80 To date the relationship between Wnt pathways and PC dysfunction in cystogenesis is controversial.81,82 The first evidence of a possible link between BBS and Wnt signalling aberration arises from the observation that knocking down Bbs1, Bbs4, and Mkks resulted in a hyperactive Wnt response in cultured mammalian cells. Gerdes et al.73 showed that Bbs proteins regulate Wnt signalling by selective proteolysis of Wnt components. They demonstrated that at baseline, Bbs4 interacted with RPN10, a proteosomal subunit, and modulated β-catenin degradation. So, when Bbs4 is depleted this interaction fails and a stabilization of cytosolic β-catenin is observed.73 Interestingly, depletion of Bbs1, Bbs4, and Bbs6 in mice recapitulated several phenotypic manifestations of PCP mutant mice, such as neural tube defects, perturbation of cochlear stereociliary bundles, and disruption of convergent extension movements.83 In addition, Wiens et al.78 showed that overexpression of BBS3/arl6 in inner medullary collecting duct cells improved cilia resorption followed by hyperactive Wnt response. An additional piece of evidence indicating a role of BBS proteins in proteosomal activities is the finding that BBS11/TRIM32 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase, promoting degradation of several targets.84

Aberrant Cytoskeleton Regulation and Cell Division

Actin cytoskeleton regulation has been shown to be crucial in kidney development; its defect has been associated with the pathogenesis of kidney dysplasia and cysts formation, common abnormalities in patients with BBS.85,86 BBS4, BBS6, and BBS8 have been shown to regulate actin polymerization. In primary kidney cells, when these proteins are absent or their levels are reduced, actin cytoskeleton appears disorganized, with an increased amount of focal adhesions and a colocalization of BBS8 and BBS9 with vinculin. Downregulation of BBS4 and BBS6 also affected cilia, which appear shortened.45 Accordingly, BBIP10/BBS18, a recently discovered BBSome subunit, is required for cytoplasmic microtubule polymerization and acetylation. Interestingly, BBIP10 interacts physically with HDAC6 and promotes microtubule acetylation by inhibiting HDAC6 activity in a BBSome-independent manner.72 Recently, Guo et al.87 reported that fibroblast cells derived from mice and humans harboring the BBS1M390R variant displayed defects in migration and wound healing, suggesting that BBsome may have a role in cell motility and tissue repair.

CCDC28B (MGC1203) was identified as a second site modifier of BBS, encoding a protein of unknown function. Depletion of Ccdc28b in zebrafish resulted in defective ciliogenesis and recapitulated several clinical manifestations of patients with BBS, including renal dysfunction. Recently, Cardenas-Rodriguez et al.88 showed that CCDC28B regulate cilia length through interaction with SN1, a subunit of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2), by affecting its assembly/stability. Given that mTORC2 is involved actin regulation (and as a consequence in cell morphology and polarity), while BBS participate to the PCP pathway, the authors argue whether impaired mTORC2 signalling could exacerbate a PCP-dependent phenotype.88 In addition, indirect data suggest a connection between BBS and mTOR signalling; the kidney cystic phenotype in a zebrafish model of BBS was rescued by culturing embryos with the mTOR signalling inhibitor rapamycin.89

Ciliogenesis and cell cycle are intimately linked, and in fact cilia mutant cells commonly show abnormal cell division, with defective mitotic spindle formation.90 BBS6 knockdown in COS-7 cells resulted in impaired cytokinesis, with cells that remained attached to one another by thin cellular bridges. Similarly, the loss of Bbs4 resulted in binucleate or multinucleate cells, suggesting that BBS4 is required for cell division.36,37

Impaired Transcriptional Regulation

Recent evidence suggests that BBS proteins have a role in transcriptional regulation. Consistent with this, several BBS proteins are predicted to possess nuclear export signals, suggesting their possible detection in the nuclei of mammalian cells.47,91 The effective nuclear localization has been proven only for BBS7. In addition, BBS1, BBS2, BBS4, BBS5, BBS6, BBS7, BBS8, and BBS10 interact with RNF2, a chromatin remodeler of the polycomb group, suggesting their role in the regulation of gene expression. Depletion of BBS4 and BBS7 result in an increase of RNF2 protein levels.47

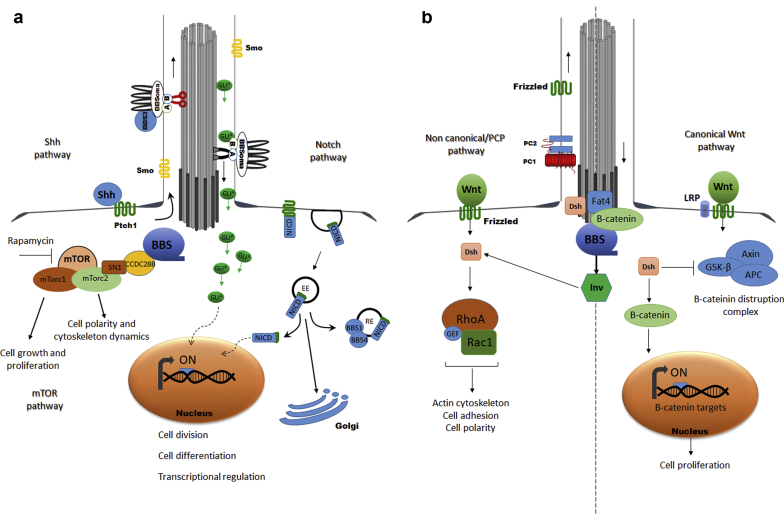

These findings provide several possible molecular aberrations that may participate in the pathogenesis of kidney disease in BBS (Figure 1); however, their exact contribution is currently unknown.

Figure 1.

Putative abnormal signalling pathways contributing to the pathogenesis of kidney disease in Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS). (a) Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signalling: upon binding of Hh to Patched1 (Ptch1), Smoothened (Smo) is released from Ptch1 and accumulates in the primary cilia (PC). In the PC, Smo induces translocation of Gli activated (GliA) proteins to the tip of the PC by intraflagellar transport. The BBSome, via BBS3/arl6, regulates ciliary trafficking of Gli proteins. GliAs translocate to the nucleus and regulates the transcription of several Shh target genes. Notch signalling: Notch receptor undergoes endosomal sorting for either degradation or recycling to the plasma membrane. Plasma membrane recycling requires BBS1 and BBS4. After binding its ligand, Notch receptor undergoes clivation and the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) translocates to the nucleus and regulates the transcription of downstream targets. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling: CCDC28B interacts with several BBSome components. It is a positive regulator of mTorc2 activity by binding directly SN1 and affecting mTorc2 assembly/stability. Rapamycin treatment inhibited mTOR signalling and rescued renal cystic phenotype in a BBS zebrafish model. (b) Wnt signalling: several Wnt signalling components localize to the basal body of the kidney PC, including inversin, dishevelled, and Fat4. Knockdown of several BBS results in overactivation of WNT signaling.

Major Experimental Models of BBS: Focusing on Kidney Disease

Transgenic mice offer the striking opportunity to study the effect of genetic mutations in a systemic and realistic context.92 To date several mice models recapitulating most human BBS clinical features, especially cardinal features, have been developed (Table 1). However, some features show variable expression. This is the case with polydactyly, one of the most common findings in patients with BBS,2 since it has never been described in mice models of disease.

In 2004, Mykytyn et al.57 described a Bbs4 KO mouse model showing major human features. The mice were smaller than their littermates up to 3 weeks of age; they became obese when adults. The renal phenotype consisted of cysts that developed at 6 months of age without specific tubular segment localization. At microscopic levels, PC in both trachea and cultured kidney epithelial cells was present but showed different lengths when compared with control mice.57

Eichers et al.52 characterized another Bbs4 KO model (Bbs4−/−), confirming the presence of obesity and retinal dystrophy. At 6 months of age, mice displayed cystic kidney, predominantly at tubular rather than glomerular levels. Of note, not all newborn Bbs4−/− mice displayed a complete phenotype, in accordance with the interfamilial variability observed in patients.52

Bbs2−/− mice characterized by Nishimura et al.38 developed obesity and retinal degeneration and males failed to synthesize spermatozoa flagella. Polycystic kidney disease was described as a not fully penetrant feature in this model. When present, mutant mice displayed bilateral multicystic kidneys with cysts in the urinary space surrounding glomeruli.38

In 2005, Fath et al.53 described the phenotype of Mkks/Bbs6 KO mice, showing that it closely resembled the phenotype of previously described mice. However, the phenotype was less severe and retinal degeneration appeared later. Polydactyly and kidney defects were not described. The PC of kidney epithelial cells were normal in density and size.53

In 2010, Guo et al.54 compared renal histology of different BBS mouse models. The extrarenal phenotype was similar, except that hypertension was absent in Bbs2−/− mice and present in Bbs4−/− mice. Histologic analysis revealed that while Bbs2−/− mice had minor inflammatory infiltration, Bbs4−/− mice exhibited age-dependent glomerular cysts. Interestingly, calorie restriction prevented the onset of both obesity and kidney abnormalities, suggesting that systemic rather than local BBS defects influence renal disease.93 Davis et al.55 generated a Bbs1M390R/M390R knock-in mouse model. Mice displayed obesity, retinal degeneration, male infertility, and decreased olfaction. There was no evidence of any renal abnormality. Obesity was associated with increase of food intake, elevated blood levels of leptin, and decreased locomotor activity.55

Bbs7 KO mice showed most phenotypic aspects of human disease, including obesity, retinal degeneration, ventriculomegaly, thinning of the cerebral cortex, and reduction of hippocampus and corpus striatum. They did not show renal cysts or polydactyly.56

A Bbs3 KO mouse model developed some unique features: increased fat mass without overt obesity and hydrocephalus. Motile cilia of the ependymal cell layer lining the cerebral ventricles were reduced in number. Instead, PC from kidney, eye, and pancreas appeared normal in size, number, and structure. In addition, kidney development was not affected.57 In 2012, Marion et al.58 generated a Bbs12 KO mouse model. Mutant mice appeared smaller at birth compared with wild-type mice but became obese later in life. Retinal degeneration and structural renal abnormalities were both detectable in adulthood. Hyperleptinemia, another trait in common with humans,31,94 was observed.58

Cognard et al.60 generated either constitutive and kidney-specific BbS10 KO mice, the only kidney-specific BBS mouse model described in the literature. Interestingly, total Bbs10−/− mice displayed obesity, hyperleptinemia, and retinal degeneration. Electron microscopy analysis revealed a significant decrease of glomerular basement membrane thickness, with a lack of primary and secondary podocyte structures. Cilia of kidney epithelial cells were detected, suggesting that BBS10 is not required for primary cilia biogenesis. In addition, tubular epithelial cells were correctly polarized, but showed large intracytoplasmic inclusions of unknown significance. No cysts were detected. Functional analysis revealed polyuria and hyposthenuria.60 Kidney-specific Bbs10 KO mice did not exhibit structural and/or functional kidney defects, suggesting that systemic rather than local factors affect kidney function.95 Finally, Loktev et al.56 described the phenotype of BBPI10/BBS18 null mice; obesity, hyperphagia, retinal degeneration, and male sterility recapitulated most human findings. No information on kidney structure have been provided. In addition, a high percentage of these mice did not survive until weaning.59

In the last decades, zebrafish has become a key model for studying organ development and disease and to test new therapeutic approaches, given the low cost, rapid development, embryonic transparency, easy manipulation, and large fecundity rates.96 Several advances in kidney-related ciliopathies have been derived from zebrafish studies.97 Nevertheless, major studies on zebrafish BBS models focused on developmental extrarenal defects, in particular the morphogenesis of the Kupffer vesicle, a ciliated organ essential for the establishment of left–right symmetry,98 while relatively few studies investigated kidney phenotypes. The latter has been described in at least 4 BBS models. BBS4, BBS6, and BBS8 knockdown resulted in kidney cysts formation.89 Interestingly, rapamycin and roscovitine restored structural and functional kidney anomalies, providing the first application of preclinical treatment of kidney disease in zebrafish models of BBS. Recently, Aldahmesh et al.99 generated a zebrafish BBS19 (IFT27) model, recapitulating most BBS phenotypes, including cystic kidney disease, that was described in 36.1% of morphants, confirming the absence of a full penetrance of kidney disease, similarly to mice models.

Conclusions

BBS is a pleiotropic disorder and kidney disease is among the cardinal features; however, CKD severity is variable, with some patients showing only mild urine concentrating defects and others severe CKD requiring dialysis or kidney transplant. Both the rarity and the genetic heterogeneity of the disease make difficult to get firm conclusions in term of genotype–phenotype correlation; a recent metanalysis suggests that patients with BBS1 mutations have a less severe renal phenotype than patients carrying mutations in the BBSome core components and in the most common BBS2 and BBS10 genes. Interestingly, BBS genes have a relative low expression level in the kidney compared with the retina. Whether genetic expression may increase in specific stressing condition remains a possibility, demonstrated for some BBS loci. Independent studies have shown that BBS proteins participate to PC signalling, with a partial role in overall PC formation and a crucial role in the trafficking of ciliary proteins. Interestingly, extraciliary functions have been shown and several signalling pathways involved in embryonic kidney development and kidney repair are impaired in BBS-depleted cell models.100 The exact contribution of these aberrations into the pathogenesis of kidney disease requires further analysis. In vivo studies suggest that kidney disease shows a not full penetrance; when present, kidney abnormalities resemble defects observed in patients. These findings suggest that factor(s) in addition to the biallelic BBS mutations might be required for cysts formation and other abnormalities. Whether comorbidities and/or additional genetic variants may serve as a “second hit” phenomenon cannot be excluded. Little information is available on the contribution of local versus systemic factors in determining the onset and the progression of kidney disease because most animal models are constitutive-total KO models.101 Interestingly, 2 studies indicate that systemic factors, i.e. obesity and total rather than kidney-specific Bbs10 deficiency, are associated with more significant kidney impairment.87 In conclusion, intensive investigations have elucidated the major functions of BBS proteins and have provided some clues to put forward hypotheses on the pathogenesis of kidney dysfunction; further studies are still needed to better address the exact pathomechanism underlying kidney disease.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work is generated within the European Reference Network for Rare Kidney Diseases and MZ was partially funded by a grant from Università degli Studi della Campania, L. Vanvitelli, Progetto Valere.

Footnotes

Supplementary Table S1. Major gene disease of Bardet-Biedl syndrome

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Zaghloul N.A., Katsanis N. Mechanistic insights into Bardet-Biedl syndrome, a model ciliopathy. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:428–437. doi: 10.1172/JCI37041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beales P.L., Elcioglu N., Woolf A.S. New criteria for improved diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome: results of a population survey. J Med Genet. 1999;36:437–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zacchia M., Zacchia E., Zona E. Renal phenotype in Bardet-Biedl syndrome: a combined defect of urinary concentration and dilution is associated with defective urinary AQP2 and UMOD excretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311:F686–F694. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00224.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harnett J.D., Green J.S., Cramer B.C. The spectrum of renal disease in Laurence-Moon-Biedl syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:615–618. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809083191005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zona E., Zacchia M., Di Iorio V. Patho-physiology of renal dysfunction in Bardet-Biedl syndrome [in Italian] G Ital Nefrol. 2017;34:62–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atmis B., Karabay-Bayazit A., Melek E. Renal features of Bardet Biedl syndrome: a single center experience. Turk J Pediatr. 2019;61:186–192. doi: 10.24953/turkjped.2019.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viggiano D., Zacchia M., Simonelli F. The renal lesions in Bardet-Biedl syndrome: history before and after the discovery of BBS genes. G Ital Nefrol. 2018;35:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caterino M., Zacchia M., Costanzo M. Urine proteomics revealed a significant correlation between urine-fibronectin abundance and estimated-GFR decline in patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2018;43:389–405. doi: 10.1159/000488096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zacchia M., Capolongo G., Rinaldi L. The importance of the thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop in renal physiology and pathophysiology. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2018;11:81–92. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S154000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsythe E., Kenny J., Bacchelli C. Managing Bardet-Biedl syndrome-now and in the Future. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:23. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zacchia M., Capolongo G., Trepiccione F. Impact of local and systemic factors on kidney dysfunction in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2017;42:784–793. doi: 10.1159/000484301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwitek-Black A.E., Carmi R., Duyk G.M. Linkage of Bardet-Biedl syndrome to chromosome 16q and evidence for non-allelic genetic heterogeneity. Nat Genet. 1993;5:392–396. doi: 10.1038/ng1293-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leppert M., Baird L., Anderson K.L. Bardet-Biedl syndrome is linked to DNA markers on chromosome 11q and is genetically heterogeneous. Nat Genet. 1994;7:108–112. doi: 10.1038/ng0594-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheffield V.C., Carmi R., Kwitek-Black A. Identification of a Bardet-Biedl syndrome locus on chromosome 3 and evaluation of an efficient approach to homozygosity mapping. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:1331–1335. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.8.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmi R., Rokhlina T., Kwitek-Black A.E. Use of a DNA pooling strategy to identify a human obesity syndrome locus on chromosome 15. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:9–13. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katsanis N., Beales P.L., Woods M.O. Mutations in MKKS cause obesity, retinal dystrophy and renal malformations associated with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;26:67–70. doi: 10.1038/79201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morisada N., Hamada R., Miura K. Bardet-Biedl syndrome in two unrelated patients with identical compound heterozygous SCLT1 mutations. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:260–265. doi: 10.1007/s13730-020-00472-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindstrand A., Davis E.E., Carvalho C.M. Recurrent CNVs and SNVs at the NPHP1 locus contribute pathogenic alleles to Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:745–754. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wormser O., Gradstein L., Yogev Y. SCAPER localizes to primary cilia and its mutation affects cilia length, causing Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27:928–940. doi: 10.1038/s41431-019-0347-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Billingsley G., Deveault C., Heon E. BBS mutational analysis: a strategic approach. Ophthalmic Genet. 2011;32:181–187. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2011.567319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eichers E.R., Lewis R.A., Katsanis N. Triallelic inheritance: a bridge between Mendelian and multifactorial traits. Ann Med. 2004;36:262–272. doi: 10.1080/07853890410026214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaghloul N.A., Liu Y., Gerdes J.M. Functional analyses of variants reveal a significant role for dominant negative and common alleles in oligogenic Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10602–10607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000219107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abu-Safieh L., Al-Anazi S., Al-Abdi L. In search of triallelism in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:420–427. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sodini S.M., Kemper K.E., Wray N.R. Comparison of genotypic and phenotypic correlations: Cheverud’s conjecture in humans. Genetics. 2018;209:941–948. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.300630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Putoux A., Attie-Bitach T., Martinovic J. Phenotypic variability of Bardet-Biedl syndrome: focusing on the kidney. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:7–15. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1751-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nigro M., Viggiano D., D’Angiò P. Inflammation in kidney diseases [in Italian] G Ital Nefrol. 2020;34 2020–vol3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esposito G., Testa F., Zacchia M. Genetic characterization of Italian patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome and correlation to ocular, renal and audio-vestibular phenotype: identification of eleven novel pathogenic sequence variants. BMC Med Genet. 2017;18:10. doi: 10.1186/s12881-017-0372-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daniels A.B., Sandberg M.A., Chen J. Genotype-phenotype correlations in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:901–907. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Estrada-Cuzcano A., Koenekoop R.K., Senechal A. BBS1 mutations in a wide spectrum of phenotypes ranging from nonsyndromic retinitis pigmentosa to Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol0. 2012;130:1425–1432. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Q., Seo S., Bugge K. BBS proteins interact genetically with the IFT pathway to influence SHH-related phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1945–1953. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imhoff O., Marion V., Stoetzel C. Bardet-Biedl syndrome: a study of the renal and cardiovascular phenotypes in a French cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:22–29. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03320410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forsythe E., Sparks K., Best S. Risk factors for severe renal disease in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:963–970. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015091029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niederlova V., Modrak M., Tsyklauri O. Meta-analysis of genotype-phenotype associations in Bardet-Biedl syndrome uncovers differences among causative genes. Hum Mutat. 2019;40:2068–2087. doi: 10.1002/humu.23862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patnaik S.R., Farag A., Brucker L. Tissue-dependent differences in Bardet-Biedl syndrome gene expression. Biol Cell. 2020;112:39–52. doi: 10.1111/boc.201900077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Datta P., Allamargot C., Hudson J.S. Accumulation of non-outer segment proteins in the outer segment underlies photoreceptor degeneration in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E4400–E4409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510111112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J.C., Ou Y.Y., Badano J.L. MKKS/BBS6, a divergent chaperonin-like protein linked to the obesity disorder Bardet-Biedl syndrome, is a novel centrosomal component required for cytokinesis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1007–1020. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim J.C., Badano J.L., Sibold S. The Bardet-Biedl protein BBS4 targets cargo to the pericentriolar region and is required for microtubule anchoring and cell cycle progression. Nat Genet. 2004;36:462–470. doi: 10.1038/ng1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishimura D.Y., Fath M., Mullins R.F. Bbs2–null mice have neurosensory deficits, a defect in social dominance, and retinopathy associated with mislocalization of rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16588–16593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405496101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ansley S.J., Badano J.L., Blacque O.E. Basal body dysfunction is a likely cause of pleiotropic Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nature. 2003;425:628–633. doi: 10.1038/nature02030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J.B., Gerdes J.M., Haycraft C.J. Comparative genomics identifies a flagellar and basal body proteome that includes the BBS5 human disease gene. Cell. 2004;117:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joukov V., De Nicolo A. The centrosome and the primary cilium: the yin and yang of a hybrid organelle. Cells. 2019;8:701. doi: 10.3390/cells8070701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dawe H.R., Smith U.M., Cullinane A.R. The Meckel-Gruber syndrome proteins MKS1 and meckelin interact and are required for primary cilium formation. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:173–186. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin H., White S.R., Shida T. The conserved Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins assemble a coat that traffics membrane proteins to cilia. Cell. 2010;141:1208–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marion V., Stoetzel C., Schlicht D. Transient ciliogenesis involving Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins is a fundamental characteristic of adipogenic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1820–1825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812518106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hernandez-Hernandez V., Pravincumar P., Diaz-Font A. Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins control the cilia length through regulation of actin polymerization. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:3858–3868. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.May-Simera H.L., Petralia R.S., Montcouquiol M. Ciliary proteins Bbs8 and Ift20 promote planar cell polarity in the cochlea. Development. 2015;142:555–566. doi: 10.1242/dev.113696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gascue C., Tan P.L., Cardenas-Rodriguez M. Direct role of Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins in transcriptional regulation. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:362–375. doi: 10.1242/jcs.089375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anosov M., Birk R. Bardet-Biedl syndrome obesity: BBS4 regulates cellular ER stress in early adipogenesis. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;126:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seo S., Baye L.M., Schulz N.P. BBS6, BBS10, and BBS12 form a complex with CCT/TRiC family chaperonins and mediate BBSome assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1488–1493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910268107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mokrzan E.M., Lewis J.S., Mykytyn K. Differences in renal tubule primary cilia length in a mouse model of Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2007;106:e88–e96. doi: 10.1159/000103021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mykytyn K., Mullins R.F., Andrews M. Bardet-Biedl syndrome type 4 (BBS4)-null mice implicate Bbs4 in flagella formation but not global cilia assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8664–8669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402354101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eichers E.R., Abd-El-Barr M.M., Paylor R. Phenotypic characterization of Bbs4 null mice reveals age-dependent penetrance and variable expressivity. Hum Genet. 2006;120:211–226. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0197-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fath M.A., Mullins R.F., Searby C. Mkks-null mice have a phenotype resembling Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1109–1118. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo D.F., Beyer A.M., Yang B. Inactivation of Bardet-Biedl syndrome genes causes kidney defects. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F574–F580. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00150.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis R.E., Swiderski R.E., Rahmouni K. A knockin mouse model of the Bardet-Biedl syndrome 1 M390R mutation has cilia defects, ventriculomegaly, retinopathy, and obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19422–19427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708571104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Q., Nishimura D., Vogel T. BBS7 is required for BBSome formation and its absence in mice results in Bardet-Biedl syndrome phenotypes and selective abnormalities in membrane protein trafficking. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:2372–2380. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Q., Nishimura D., Seo S. Bardet-Biedl syndrome 3 (Bbs3) knockout mouse model reveals common BBS-associated phenotypes and Bbs3 unique phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20678–20683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113220108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marion V., Mockel A., De Melo C. BBS-induced ciliary defect enhances adipogenesis, causing paradoxical higher-insulin sensitivity, glucose usage, and decreased inflammatory response. Cell Metab. 2012;16:363–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loktev A.V., Jackson P.K. Neuropeptide Y family receptors traffic via the Bardet-Biedl syndrome pathway to signal in neuronal primary cilia. Cell Rep. 2013;5:1316–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cognard N., Scerbo M.J., Obringer C. Comparing the Bbs10 complete knockout phenotype with a specific renal epithelial knockout one highlights the link between renal defects and systemic inactivation in mice. Cilia. 2015;4:10. doi: 10.1186/s13630-015-0019-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zacchia M., Esposito G., Carmosino M. Knockdown of the BBS10 gene product affects apical targeting of AQP2 in renal cells: a possible explanation for the polyuria associated with Bardet–Biedl syndrome. J Genet Syndr Gene Ther. 2014;5:3. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berbari N.F., Lewis J.S., Bishop G.A. Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins are required for the localization of G protein-coupled receptors to primary cilia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4242–4246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klink B.U., Zent E., Juneja P. A recombinant BBSome core complex and how it interacts with ciliary cargo. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.27434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu J., Carroll T.J., McMahon A.P. Sonic hedgehog regulates proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal cells in the mouse metanephric kidney. Development. 2002;129:5301–5312. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.22.5301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tran P.V., Talbott G.C., Turbe-Doan A. Downregulating hedgehog signaling reduces renal cystogenic potential of mouse models. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2201–2212. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013070735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fabian S.L., Penchev R.R., St-Jacques B. Hedgehog-Gli pathway activation during kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:1441–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eguether T., San Agustin J.T., Keady B.T. IFT27 links the BBSome to IFT for maintenance of the ciliary signaling compartment. Dev Cell. 2014;31:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kotsis F., Boehlke C., Kuehn E.W. The ciliary flow sensor and polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:518–526. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Su X., Driscoll K., Yao G. Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins 1 and 3 regulate the ciliary trafficking of polycystic kidney disease 1 protein. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:5441–5451. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ma M., Gallagher A.R., Somlo S. Ciliary mechanisms of cyst formation in polycystic kidney disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017;9:a028209. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leitch C.C., Lodh S., Prieto-Echague V. Basal body proteins regulate Notch signaling through endosomal trafficking. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:2407–2419. doi: 10.1242/jcs.130344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Loktev A.V., Zhang Q., Beck J.S. A BBSome subunit links ciliogenesis, microtubule stability, and acetylation. Dev Cell. 2008;15:854–865. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gerdes J.M., Liu Y., Zaghloul N.A. Disruption of the basal body compromises proteasomal function and perturbs intracellular Wnt response. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1350–1360. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Anvarian Z., Mykytyn K., Mukhopadhyay S. Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15:199–219. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0116-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gerhardt C., Leu T., Lier J.M. The cilia-regulated proteasome and its role in the development of ciliopathies and cancer. Cilia. 2016;5:14. doi: 10.1186/s13630-016-0035-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sirin Y., Susztak K. Notch in the kidney: development and disease. J Pathol. 2012;226:394–403. doi: 10.1002/path.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Le Borgne R. Regulation of Notch signalling by endocytosis and endosomal sorting. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wiens C.J., Tong Y., Esmail M.A. Bardet-Biedl syndrome-associated small GTPase ARL6 (BBS3) functions at or near the ciliary gate and modulates Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16218–16230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.070953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kawakami T., Ren S., Duffield J.S. Wnt signalling in kidney diseases: dual roles in renal injury and repair. J Pathol. 2013;229:221–231. doi: 10.1002/path.4121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iervolino A., Trepiccione F., Petrillo F. Selective dicer suppression in the kidney alters GSK3beta/beta-catenin pathways promoting a glomerulocystic disease. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gascue C., Katsanis N., Badano J.L. Cystic diseases of the kidney: ciliary dysfunction and cystogenic mechanisms. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1181–1195. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1697-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim E., Arnould T., Sellin L.K. The polycystic kidney disease 1 gene product modulates Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4947–4953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ross A.J., May-Simera H., Eichers E.R. Disruption of Bardet-Biedl syndrome ciliary proteins perturbs planar cell polarity in vertebrates. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1135–1140. doi: 10.1038/ng1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang Q., Yu D., Seo S. Intrinsic protein-protein interaction-mediated and chaperonin-assisted sequential assembly of stable bardet-biedl syndrome protein complex, the BBSome. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:20625–20635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.341487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Elias B.C., Das A., Parekh D.V. Cdc42 regulates epithelial cell polarity and cytoskeletal function during kidney tubule development. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:4293–4305. doi: 10.1242/jcs.164509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mathieson P.W. The podocyte cytoskeleton in health and in disease. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5:498–501. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfs153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Guo D.F., Rahmouni K. The Bardet-Biedl syndrome protein complex regulates cell migration and tissue repair through a Cullin-3/RhoA pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2019;317:C457–C465. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00498.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cardenas-Rodriguez M., Irigoin F., Osborn D.P. The Bardet-Biedl syndrome-related protein CCDC28B modulates mTORC2 function and interacts with SIN1 to control cilia length independently of the mTOR complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4031–4042. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tobin J.L., Beales P.L. Restoration of renal function in zebrafish models of ciliopathies. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:2095–2099. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0898-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.AbouAlaiwi W.A., Ratnam S., Booth R.L. Endothelial cells from humans and mice with polycystic kidney disease are characterized by polyploidy and chromosome segregation defects through survivin down-regulation. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:354–367. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Caterino M., Ruoppolo M., Fulcoli G. Transcription factor TBX1 overexpression induces downregulation of proteins involved in retinoic acid metabolism: a comparative proteomic analysis. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1515–1526. doi: 10.1021/pr800870d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.White J.K., Gerdin A.K., Karp N.A. Genome-wide generation and systematic phenotyping of knockout mice reveals new roles for many genes. Cell. 2013;154:452–464. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Trepiccione F., Zacchia M., Capasso G. The role of the kidney in salt-sensitive hypertension. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2012;16:68–72. doi: 10.1007/s10157-011-0489-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Feuillan P.P., Ng D., Han J.C. Patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome have hyperleptinemia suggestive of leptin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E528–E535. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zacchia M., Di Iorio V., Trepiccione F. The kidney in Bardet-Biedl syndrome: possible pathogenesis of urine concentrating defect. Kidney Dis (Basel) 2017;3:57–65. doi: 10.1159/000475500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Castro-Sanchez S., Suarez-Bregua P., Novas R. Functional analysis of new human Bardet-Biedl syndrome loci specific variants in the zebrafish model. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12936. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49217-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gehrig J., Pandey G., Westhoff J.H. Zebrafish as a model for drug screening in genetic kidney diseases. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:183. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Swanhart L.M., Cosentino C.C., Diep C.Q. Zebrafish kidney development: basic science to translational research. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2011;93:141–156. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Aldahmesh M.A., Li Y., Alhashem A. IFT27, encoding a small GTPase component of IFT particles, is mutated in a consanguineous family with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:3307–3315. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zacchia M, Marchese E, Trani EM, et al. Proteomics and metabolomics studies exploring the pathophysiology of renal dysfunction in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and other ciliopathies [e-pub ahead of print]. Nephrol Dial Transplant.https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz121. Accessed July 19, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 101.Trepiccione F., Soukaseum C., Iervolino A. A fate-mapping approach reveals the composite origin of the connecting tubule and alerts on “single-cell”–specific KO model of the distal nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311:F901–F906. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00286.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.