Key Points

Question

Was there an association between patient social risk and physician performance in the first year of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), a major Medicare value-based payment program?

Findings

In this cross-sectional observational study of 284 544 physicians, physicians with the highest proportion of patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid had significantly lower MIPS scores compared with physicians with the lowest proportion (mean, 64.7 vs 75.9; range, 0-100; higher scores reflect better performance).

Meaning

Physicians with the highest proportion of socially disadvantaged patients had significantly lower MIPS scores, although further research is needed to understand the reasons underlying the differences in MIPS scores by levels of patient social risk.

Abstract

Importance

The US Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is a major Medicare value-based payment program aimed at improving quality and reducing costs. Little is known about how physicians’ performance varies by social risk of their patients.

Objective

To determine the relationship between patient social risk and physicians’ scores in the first year of MIPS.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Cross-sectional study of physicians participating in MIPS in 2017.

Exposures

Physicians in the highest quintile of proportion of dually eligible patients served; physicians in the 3 middle quintiles; and physicians in the lowest quintile.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the 2017 composite MIPS score (range, 0-100; higher scores indicate better performance). Payment rates were adjusted –4% to 4% based on scores.

Results

The final sample included 284 544 physicians (76.1% men, 60.1% with ≥20 years in practice, 11.9% in rural location, 26.8% hospital-based, and 24.6% in primary care). The mean composite MIPS score was 73.3. Physicians in the highest risk quintile cared for 52.0% of dually eligible patients; those in the 3 middle risk quintiles, 21.8%; and those in the lowest risk quintile, 6.6%. After adjusting for medical complexity, the mean MIPS score for physicians in the highest risk quintile (64.7) was lower relative to scores for physicians in the middle 3 (75.4) and lowest (75.9) risk quintiles (difference for highest vs middle 3, –10.7 [95% CI, –11.0 to –10.4]; highest vs lowest, –11.2 [95% CI, –11.6 to –10.8]; P < .001). This relationship was found across specialties except psychiatry. Compared with physicians in the lowest risk quintile, physicians in the highest risk quintile were more likely to work in rural areas (12.7% vs 6.4%; difference, 6.3 percentage points [95% CI, 6.0 to 6.7]; P < .001) but less likely to care for more than 1000 Medicare beneficiaries (9.4% vs 17.8%; difference, –8.3 percentage points [95% CI, –8.7 to –8.0]; P < .001) or to have more than 20 years in practice (56.7% vs 70.6%; difference, –13.9 percentage points [95% CI, –14.4 to –13.3]; P < .001). For physicians in the highest risk quintile, several characteristics were associated with higher MIPS scores, including practicing in a larger group (mean score, 82.4 for more than 50 physicians vs 46.1 for 1-5 physicians; difference, 36.2 [95% CI, 35.3 to 37.2]; P < .001) and reporting through an alternative payment model (mean score, 79.5 for alternative payment model vs 59.9 for reporting as individual; difference, 19.7 [95% CI, 18.9 to 20.4]; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional analysis of physicians who participated in the first year of the Medicare MIPS program, physicians with the highest proportion of patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid had significantly lower MIPS scores compared with other physicians. Further research is needed to understand the reasons underlying the differences in physician MIPS scores by levels of patient social risk.

This study uses data from the Medicare Physician Compare database to assess associations between patient social risk, defined as dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid, and physicians’ Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) data scores, a proxy for patient outcomes and care value.

Introduction

In 2017, Medicare began making payments to physicians under the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)—one of 2 major paths for physicians to engage in value-based care through the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. With MIPS, eligible physicians can receive rewards or penalties based on their performance across 4 domains: quality, costs, improvement activities, and promoting interoperability. More than 90% of eligible physicians participated in the program in 2017, and payments were adjusted up to 4% in 2019.1 While several types of clinicians participate in MIPS, this study focuses on physicians.

MIPS is Medicare’s latest attempt to link physician payments to the value of care and builds on other recent attempts at pay for performance, most notably the value-based payment modifier.2 Prior studies have found mixed results on whether value-based purchasing improves quality or reduces costs,3,4,5 but there is growing concern that these programs may exacerbate health disparities because they lack adequate adjustment for patient social risk.6,7,8,9 Recognizing this concern, Medicare recently introduced several exemptions and bonuses, including a “complex patient bonus” to adjust for patient medical and social complexity, but it remains unclear how these changes will affect MIPS scores and payment.

Prior research has shown an association between social factors and physician group performance,10,11,12 but to our knowledge, no studies have evaluated how patient social risk is related to performance in MIPS—a program that influences payment for hundreds of thousands of physicians and that will play a larger role in Medicare reimbursement over time. This study examines 3 questions. First, did physicians caring for more socially disadvantaged patients have lower scores in the first year of MIPS? Second, how did MIPS performance vary by medical specialty across the spectrum of patient social risk? Third, among physicians caring for the most socially disadvantaged patients, what characteristics were associated with better scores?

Methods

This study was deemed non–human subjects research by the institutional review board at Weill Cornell Medical College. Patient consent was not required because the study used administrative, deidentified data.

Data and Sample

Using publicly available data in Medicare Physician Compare files, all clinicians who participated in MIPS in 2017 were identified and their MIPS composite scores, category scores, and relevant demographic information were extracted.13 National Provider Identifier (NPI) numbers were used to link to the 2017 Medicare Fee-For-Service Provider Utilization and Payment Data—Physician and Other Supplier Public Use File14 and Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty (MD-PPAS) file15—to identify relevant clinician and practice characteristics.16 Physicians were included in the study population if they had a composite MIPS score in the Physician Compare database in 2017 that could be linked to clinician and practice characteristics relevant to the analysis. Nonphysician clinicians were excluded.

Covariates

This study examined the relationship between physicians’ performance in MIPS and the proportion of socially disadvantaged patients they cared for in 2017. Dual eligibility was used as a proxy for social risk, as has been done in other studies.7,17 The level of social risk of a physician’s patients was determined using variables from the Medicare Public Use File and was defined as the number of unique dually eligible patients divided by all unique Medicare patients seen by a physician. Beneficiaries were classified as dually eligible if they received full or partial Medicaid benefits in any month in a given calendar year. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) uses this variable for risk adjustment in the MIPS program.18

The Medicare Public Use File, which reflects 100% of Medicare enrollment data and fee-for-service Part B noninstitutional claims, was also used to obtain the mean Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) score and total number of unique Medicare beneficiaries for each physician. The Physician Compare data were used to measure physician years in practice, sex, and mode of MIPS data submission (alternative payment model, group, individual, or other). The MD-PPAS file was used to construct a measure of physician group size (number of unique NPIs billing under the same primary tax identification number). Physicians’ zip code, as reported in the Physician Compare data, was used to create an indicator for practice in a rural area, as defined by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy.19 Physicians were grouped into 6 broad specialty categories using data from the MD-PPAS file (primary care, medical subspecialty, surgical subspecialty, obstetrics/gynecology, psychiatry, and hospital-based specialty). For cases in which specialty data were not available from the MD-PPAS file, the primary specialty included in Physician Compare was used. An NPI was identified as belonging to a multispecialty group if the primary tax identification number included less than 80% of NPIs within a single broad specialty.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the final composite MIPS score (range, 0-100). Higher scores reflect better performance; actual 2017 scores ranged from 0 to 100. Secondary outcomes included the 3 MIPS category scores included in the program in 2017: quality (range, 0-100), advancing care information (now called “promoting interoperability”; range, 0-100), and improvement activities (range, 0-40). The cost domain was not scored by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2017. Final MIPS scores reflect a weighted sum of the category scores and other program bonuses.20 The MIPS program is budget neutral, such that more “low performers” leads to larger payment for “high performers” and vice versa. A separate $500 million is reserved for “exceptional performance.” Based on 2017 performance, payments were adjusted in 2019. A composite score difference between 0 and 2.99 resulted in a 4% reduction in payment rates. Each 10-point increase in the composite score between 3.0 and 69.99 resulted in a 0.03% increase in payment. In 2017, the “exceptional performance” threshold was set at 70, and each 10-point increase above 70 resulted in a 0.53% increase in 2019 payment.

Statistical Analysis

To examine the relationship between MIPS scores and social risk, the mean composite MIPS scores across ventiles of the proportion of physicians’ patients who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid was graphed. (Ventiles comprised 20 groups of physicians ordered by the proportion of their patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, with each group containing 1/20th of the study population.) This analysis was repeated after adjusting for patients’ clinical risk (HCC score) and, separately, after adjusting for clinical risk along with a broad set of physician and practice characteristics. The extent to which physician and practice characteristics, as well as MIPS scores, differed across physicians with a low, medium, and high proportion of dually eligible patients was then analyzed using mean-comparison (t) tests. Physicians in the second, third, and fourth quintiles were collapsed into a single “middle” category. The relationship between MIPS scores and social risk was also examined by specialty and by MIPS reporting mode. Less than 10% of observations were excluded for missing covariate data. The characteristics of excluded relative to included observations are presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement. For all of these analyses, MIPS scores were reported after adjusting for mean HCC risk score using ordinary least-squares regression to control for mean HCC score by specialty.

For physicians in the highest quintile, ordinary least-squares multivariable regression with robust standard errors was used to examine the physician and practice characteristics associated with higher MIPS scores. This regression also controlled for mean HCC risk score. Sensitivity analyses included the addition of state fixed effects and the use of the quality domain score as the outcome. Using state fixed effects, we estimated differences in MIPS scores across physicians within the same state. A model with state fixed effects includes a binary indicator for each state. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory.

The study was conducted using Stata statistical software version 14.1 (StataCorp). Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The final population included 284 544 physicians. Of the initial analytic sample of 413 233 observations in the 2017 Physician Compare file, 37 063 observations were excluded because of duplicate NPI numbers; 60 205 were excluded because they were not physicians; and 31 411 were excluded because of missing covariate data (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The mean composite MIPS score across all physicians was 73.3 (of a possible 100). Among physicians in the highest risk quintile, 52.0% of patients were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. For physicians in the middle 3 quintiles group and lowest risk quintile, 21.8% and 6.6%, respectively, of patients were dually eligible (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of MIPS-Participating Physicians by Social Risk of Patient Panel.

| Physician characteristics | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient social risk categorya | Full sample | |||

| High | Medium | Low | ||

| No. | 57 035 | 170 457 | 57 062 | 284 554 |

| Dually eligible patients, mean (SD), % | 52.0 (14.2) | 21.8 (7.1) | 6.6 (2.5) | 24.8 (17.1) |

| Women | 25.5 | 23.2 | 24.4 | 23.9 |

| Men | 74.5 | 76.8 | 75.6 | 76.1 |

| Ruralb | 12.7 | 13.4 | 6.4 | 11.9 |

| Multispecialty practice | 51.2 | 53.3 | 41.1 | 50.4 |

| Patient RISK SCORE, mean (SD)c | 2.4 (1.1) | 1.8 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.8) |

| Specialtyd | ||||

| Hospital-based | 31.0 | 30.6 | 11.3 | 26.8 |

| Medical | 22.0 | 26.0 | 26.4 | 25.3 |

| Obstetrics/gynecology | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 1.0 |

| Primary care | 28.5 | 21.2 | 30.6 | 24.6 |

| Psychiatry | 6.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.8 |

| Surgical | 11.4 | 20.6 | 29.8 | 20.6 |

| Years in practicee | ||||

| 0-5 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.4 |

| 6-19 | 41.2 | 41.0 | 28.6 | 38.5 |

| ≥20 | 56.7 | 57.6 | 70.6 | 60.1 |

| No. of beneficiariesf | ||||

| 11-200 | 21.6 | 14.9 | 7.5 | 14.8 |

| 201-499 | 48.8 | 43.7 | 42.4 | 44.5 |

| 500-999 | 20.1 | 24.1 | 32.4 | 25.0 |

| ≥1000 | 9.4 | 17.2 | 17.8 | 15.8 |

| Group size | ||||

| 1-5 | 40.0 | 25.4 | 37.8 | 30.8 |

| 6-19 | 15.1 | 17.7 | 17.3 | 17.1 |

| 20-49 | 11.8 | 14.8 | 11.7 | 13.6 |

| ≥50 | 33.1 | 42.0 | 33.2 | 38.5 |

| Score sourceg | ||||

| Alternative payment model | 18.7 | 22.7 | 19.7 | 21.3 |

| Group | 50.0 | 47.7 | 39.7 | 46.6 |

| Individual | 25.4 | 21.6 | 28.8 | 23.8 |

| Other | 5.9 | 8.0 | 11.8 | 8.3 |

Abbreviations: CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; HCC, Hierarchical Condition Category; MIPS, Merit-based Incentive Payment System.

Social risk defined as the proportion of Medicare patients treated by a physician who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Variable subcategories may not sum to 100% because of rounding. Physicians in the “high” category of patient panel social risk have a proportion of dually eligible patients in the top quintile among MIPS-participating physicians; those in the “medium” category are in the middle 3 quintiles; those in the “low” category are in the bottom quintile.

Rural indicates whether a physicians’ practice zip code was in a rural area, as defined by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy.

Risk score is the mean HCC score across physicians’ Medicare patients. Patient HCC scores were derived from the CMS HCC risk-adjustment model. A score of 1 represents an individual with average clinical risk, with higher scores representing patients at higher risk.

Additional details on the specific specialties included within each specialty category may be found in the documentation for the Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty file.15

Years in practice indicates years since completion of medical school.

Number of beneficiaries indicates the number of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries treated by a given physician.

Method by which a physician achieved their MIPS score. Other indicates that the score was based on a CMS decision.

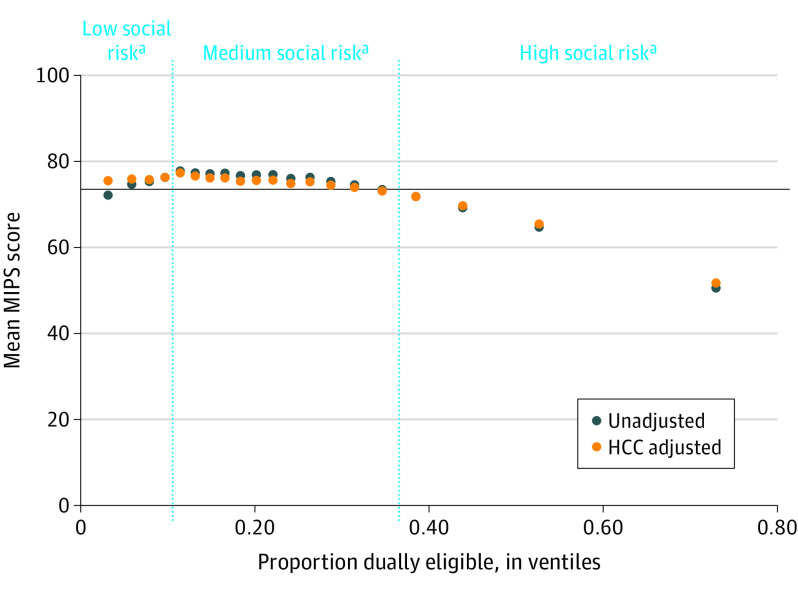

After adjustment for patient medical complexity, physicians with a higher proportion of dually eligible patients had lower MIPS scores, a relationship driven by physicians in the highest quintile (top 4 ventiles) of dually eligible patients served (Figure 1). The mean MIPS score for physicians in the highest risk quintile (64.7) was significantly lower than for physicians in the middle 3 quintiles (75.4) and lowest (75.9) risk quintile (difference for highest vs middle, –10.7 [95% CI, –11.0 to –10.4]; highest vs lowest, –11.2 [95% CI, –11.6 to –10.8]; P < .001) (Table 2). Results were similar before and after adjustment for medical complexity. Adjusting for physician and practice characteristics attenuated this relationship modestly, but a significant difference remained (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Mean Physician MIPS Scores by Ventile of Patient Social Risk, Adjusted and Unadjusted for Patient Medical Complexity.

Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) scores may range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better performance across 3 domains: advancing care information, improvement activities, and quality. The scores reflect a weighted average of performance across those domains, along with additional bonuses and adjustments. Social risk was defined as the proportion of Medicare patients treated by a physician who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Horizontal line indicates the unadjusted mean. Confidence intervals fell within the space of the plotted dots. HCC indicates Hierarchical Condition Category. Physicians were ordered by the proportion of their patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, with each group containing 1/20th of the study population (ventile).

aPhysicians in the “low” category of patient panel social risk have a proportion of dually eligible patients in the bottom quintile among MIPS-participating physicians; those in the “medium” category are in the middle 3 quintiles; those in the “high” category are in the top quintile.

Table 2. Mean Adjusted Physician MIPS Scores by Patient Panel Social Risk and Specialtya.

| Specialtyd | MIPS score by patient social risk category, mean (SD)b | Difference in means (95% CI)c | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | High vs low | P value | High vs medium | P value | Medium vs low | P value | |

| All | 64.7 (38.0) [n = 57 035] |

75.4 (32.1) [n = 170 457] |

75.9 (33.7) [n = 57 062] |

−11.2 (−11.6 to −10.8) | <.001 | −10.7 (−11.0 to −10.4) | <.001 | −0.5 (−0.8 to −0.2) | .001 |

| Hospital-based | 67.5 (35.1) [n = 17 666] |

74.7 (31.4) [n = 52 196] |

74.3 (33.9) [n = 6428] |

−6.8 (−7.8 to −5.8) | <.001 | −7.1 (−7.7 to −6.6) | <.001 | 0.3 (−0.5 to 1.2) | .41 |

| Medical | 68.7 (36.6) [n = 12 547] |

78.3 (29.8) [n = 44 329] |

79.3 (33.7) [n = 15 054] |

−10.6 (−11.4 to −9.7) | <.001 | −9.6 (−10.2 to −9.0) | <.001 | −0.9 (−1.5 to −0.4) | .001 |

| Obstetrics/ gynecology |

40.5 (43.1) [n = 283] |

69.4 (35.3) [n = 1572] |

68.7 (38.1) [n = 971] |

−28.2 (−33.4 to −23.0) | <.001 | −28.9 (−33.5 to −24.3) | <.001 | 0.7 (−2.2 to 3.6) | .62 |

| Primary care | 65.2 (38.6) [n = 16 277] |

74.8 (33.8) [n = 36 178] |

74.8 (33.3) [n = 17 476] |

−9.7 (−10.4 to −8.9) | <.001 | −9.6 (−10.3 to −9.0) | <.001 | −0.0 (−0.6 to 0.6) | .96 |

| Psychiatry | 40.0 (41.3) [n = 3763] |

38.7 (40.3) [n = 1098] |

31.3 (36.1) [n = 131] |

8.7 (1.5 to 15.9) | .02 | 1.4 (−1.4 to 4.1) | .33 | 7.3 (0.1 to 14.6) | .047 |

| Surgical | 63.4 (38.4) [n = 6499] |

74.7 (33.0) [n = 35 084] |

75.3 (33.3) [n = 17 002] |

−11.9 (−12.9 to −10.9) | <.001 | −11.3 (−12.2 to −10.4) | <.001 | −0.6 (−1.2 to −0.0) | .049 |

Abbreviation: MIPS, Merit-based Incentive Payment System.

MIPS scores may range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better performance across 3 domains: advancing care information, improvement activities, and quality. The scores reflect a weighted average of performance across those domains, along with additional bonuses and adjustments. MIPS scores were adjusted for mean patient panel clinical risk (Hierarchical Condition Category) score. Social risk was defined as the proportion of Medicare patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid in a physician’s panel.

Physicians in the “high” category of patient panel social risk have a proportion of dually eligible patients in the top quintile among MIPS-participating physicians; those in the “medium” category are in the middle 3 quintiles; those in the “low” category are in the bottom quintile.

Comparisons reflect mean-comparison (t) test between indicated subgroups.

Additional details on the specific specialties included within each specialty category may be found in the documentation for the Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty file.15

Physicians in the highest risk quintile had different characteristics compared with physicians in the middle 3 quintiles and lowest risk quintile (Table 1). For example, compared with physicians in the lowest risk quintile, physicians in the highest risk quintile were more likely to work in small practices of 1 to 5 clinicians (40.0% vs 37.8%; difference, 2.3 percentage points [95% CI, 1.7 to 2.8]; P < .001) and in rural locations (12.7% vs 6.4%; difference, 6.3 percentage points [95% CI, 6.0 to 6.7]; P < .001). They were less likely to care for more than 1000 Medicare beneficiaries (9.4% vs 17.8%; difference, –8.3 percentage points [95% CI, –8.7 to –8.0]; P < .001) or to have more than 20 years in practice (56.7% vs 70.6%; difference, –13.9 percentage points [95% CI, –14.4 to –13.3]; P < .001). Compared with physicians in the lowest risk quintile, physicians in the highest risk quintile were more likely to practice psychiatry (6.6% vs 0.2%; difference, 6.4 percentage points [95% CI, 6.2 to 6.6]; P < .001) and in hospital-based specialties (31.0% vs 11.3%; difference, 19.7 percentage points [95% CI, 19.2 to 20.2]; P < .001) but were less likely to practice in medical specialties (22.0% vs 26.4%; difference, –4.4 percentage points [95% CI, –4.9 to –3.9]; P < .001) or surgical specialties (11.4% vs 29.8%; difference, –18.4 percentage points [95% CI, –18.9 to –17.9]; P < .001). In addition, they were less likely to report to Medicare through alternative payment models (18.7% vs 19.7%; difference, –1.0 percentage points [95% CI, –1.4 to –0.5]; P < .001) and more likely to report as a group (50.0% vs 39.7%; difference, 10.3 percentage points [95% CI, 9.7 to 10.9]; P < .001).

There were significant differences by physician specialty in MIPS performance, both overall and across quintiles of social risk (Table 2). Obstetrician-gynecologists and psychiatrists had lower MIPS scores compared with other physicians. MIPS scores across specialty groups except psychiatry were significantly lower for physicians in the highest risk quintile compared with those in the middle 3 group and lowest risk quintile. For example, among physicians practicing in a medical subspecialty, the mean MIPS score for physicians in the highest risk quintile was 68.7 compared with 79.3 for physicians in the lowest risk quintile (difference, –10.6 [95% CI, –11.4 to 9.7]; P < .001). For obstetrician-gynecologists, the decrease in MIPS scores was even greater (mean score, 40.5 for highest risk vs 68.7 for lowest risk; difference, –28.2 [95% CI, –33.4 to –23.0]; P < .001).

The mode through which physicians reported measures to Medicare was also associated with differences in MIPS scores across the spectrum of patient social risk (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Physicians in the highest risk quintile who reported through an alternative payment model had scores that did not significantly differ from physicians in the middle and lowest risk quintiles, but those who reported as a group (mean score, 64.8 for highest risk vs 75.5 for lowest risk; difference, –10.7 [95% CI, –11.4 to –10.0]; P < .001) or as individuals (mean score, 49.2 for highest risk vs 66.9 for lowest risk; difference, –17.8 [95% CI, –18.5 to –17.0]; P < .001) had lower scores.

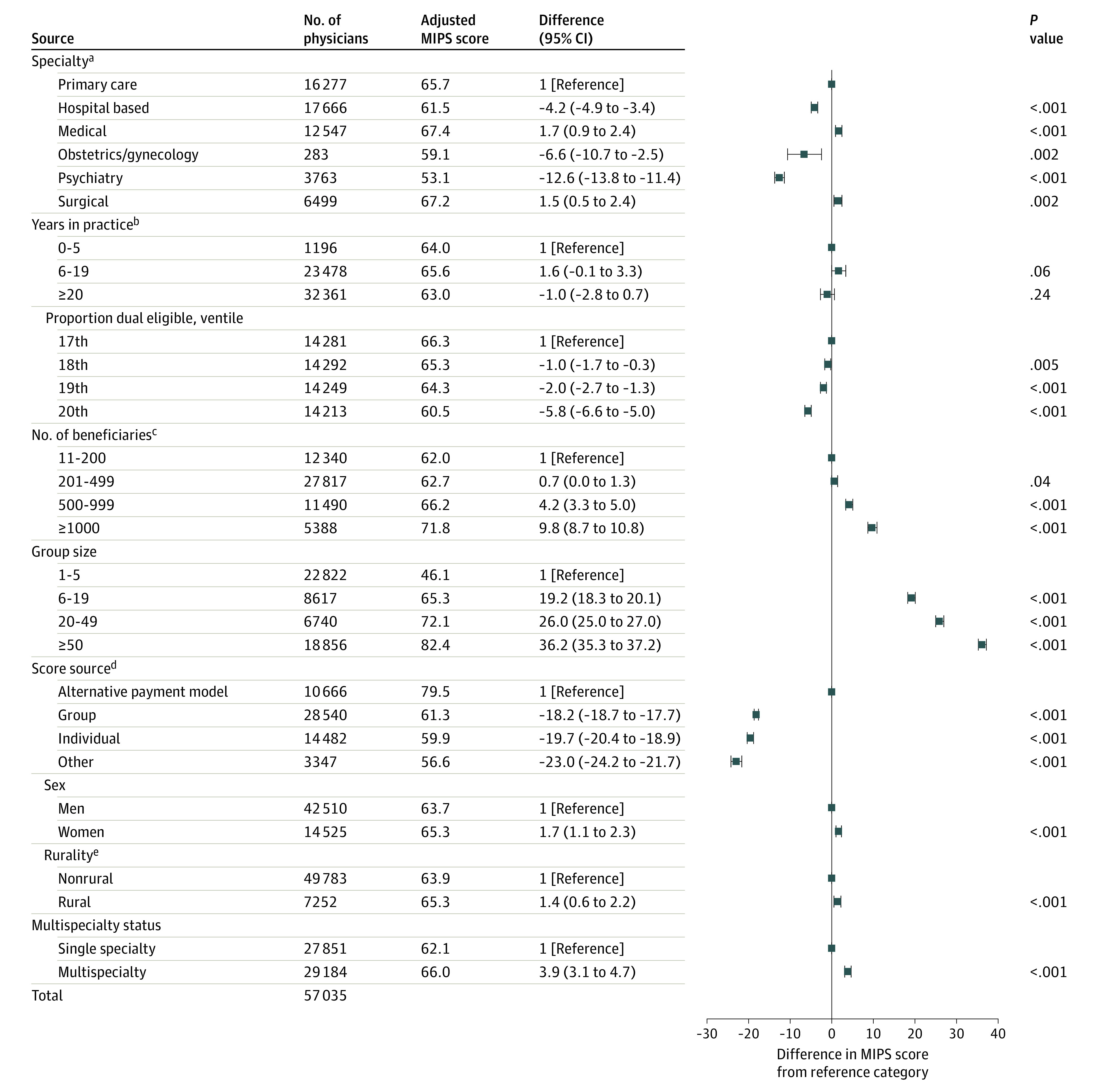

Among physicians in the highest risk quintile, several characteristics were associated with higher MIPS scores (Figure 2). For example, better MIPS performance was associated with practicing in a larger group (mean score, 82.4 for >50 physicians vs 46.1 for 1-5 physicians; difference, 36.2 [95% CI, 35.3 to 37.2]; P < .001) and caring for more Medicare beneficiaries (mean score, 71.8 for >1000 beneficiaries vs 62.0 for 11-200 beneficiaries; difference, 9.8 [95% CI, 8.7 to 10.8]; P < .001). Even among physicians in the highest risk quintile, those with a relatively higher proportion of dually eligible patients had lower MIPS scores. For example, physicians in the highest risk quintile who cared for the highest proportion of dually eligible patients had mean MIPS scores 5.8 points lower (95% CI, –6.6 to –5.0; P < .001) than those caring for the smallest proportion (mean score, 60.5 for highest proportion vs 66.3 for smallest proportion). Results were not meaningfully different in sensitivity analyses using state fixed effects or using the quality domain score as the outcome (eTables 3 and 4 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Association Between Adjusted MIPS Scores and Physician Characteristics Among Physicians With Patients of High Social Risk.

Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) scores may range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better performance across 3 domains: advancing care information, improvement activities, and quality. The scores reflect a weighted average of performance across those domains, along with additional bonuses and adjustments. “High social risk” corresponds to physicians whose proportion of dually eligible patients was in the top quintile among MIPS-participating physicians. Results obtained from ordinary least-squares regression of MIPS composite scores on listed covariates, adjusted for patient clinical risk (mean Hierarchical Condition Category score).

aAdditional details on the specific specialties included within each specialty category may be found in the documentation for the Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty file.15

bYears in practice indicates years since completion of medical school.

cNumber of beneficiaries indicates the number of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries treated by a given physician.

dSource indicates the method by which a physician achieved their MIPS score. Other indicates that the score was based on a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services decision.

eRural indicates whether a physician’s practice zip code was in a rural area, as defined by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy.

In 2017, CMS calculated MIPS scores across 3 domains: quality, advancing care information, and improvement activities. (The cost domain was scored starting in 2018.) Scores did not differ meaningfully between physicians in the middle 3 quintiles group and lowest risk quintile in any score domain (Table 3). However, physicians in the highest risk quintile had significantly lower scores in all 3 domains. For example, compared with physicians in the lowest risk quintile, those in the highest risk quintile had lower quality scores (64.0 vs 75.4; difference, –11.4 [95% CI, –11.8 to –10.9]; P < .001), lower advancing care information scores (63.4 vs 73.6; difference, –10.2 [95% CI, –10.7 to –9.7]; P < .001), and lower improvement activities scores (29.4 vs 33.3; difference, –3.9 [95% CI, –4.1 to –3.7]; P < .001).

Table 3. Mean Adjusted Physician MIPS Scores by Patient Panel Social Risk and Score Domaina.

| Domain | MIPS score by patient social risk category, mean (SD)b | Difference in means (95% CI)c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | High vs lowd | High vs mediumd | Medium vs lowd | |

| Advancing care information | 63.4 (42.7) [n = 45 298] |

75.3 (36.4) [n = 139 028] | 73.6 (39.9) [n = 53 371] | −10.2 (−10.7 to −9.7) | −11.9 (−12.3 to −11.5) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.1) |

| Improvement activities | 29.4 (17.3) [n = 57 035] |

33.0 (14.5) [n = 170 457] |

33.3 (15.1) [n = 57 062] |

−3.9 (−4.1 to −3.7) | −3.6 (−3.8 to −3.5) | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.1) |

| Quality | 64.0 (39.4) [n = 56 868] |

74.7 (33.6) [n = 168 414] |

75.4 (35.0) [n = 56 237] |

−11.4 (−11.8 to −10.9) | −10.6 (−11.0 to −10.3) | −0.7 (−1.1 to −0.4) |

Abbreviation: MIPS, Merit-based Incentive Payment System.

MIPS scores may range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better performance across 3 domains: advancing care information, improvement activities, and quality. The scores reflect a weighted average of performance across those domains, along with additional bonuses and adjustments. Examples of measures in these categories include conducting or reviewing a security risk analysis and e-prescribing (advancing care information), advance care planning (improvement activities), and tobacco use screening and cessation (quality domain). Social risk was defined as the proportion of Medicare patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid in a physician’s panel. All results adjusted for mean patient panel clinical risk (Hierarchical Condition Category) score.

Physicians in the “high” category of patient panel social risk have a proportion of dually eligible patients in the top quintile among MIPS-participating physicians; those in the “medium” category are in the middle 3 quintiles; those in the “low” category are in the bottom quintile.

Comparisons reflect mean-comparison (t) test between indicated subgroups.

P < .001 for all.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional analysis of physicians participating in the first year of the Medicare MIPS program, physicians in the highest quintile of proportion of dually eligible patients served had composite scores more than 11 points lower compared with other physicians. Even among physicians in the highest risk quintile, those who cared for the most dually eligible patients had MIPS scores 6 points lower than those who cared for the fewest dually eligible patients. The relationship between patient social risk and MIPS performance held across specialties, with the exception of psychiatry. Lower composite MIPS scores for physicians in the highest risk quintile was not driven by any one score domain but rather reflected lower scores in each of the quality, improvement activities, and advancing care information domains.

For physicians caring for the most socially disadvantaged patients, several factors were associated with higher MIPS scores, some of which are modifiable. For example, physicians in the highest risk quintile who practiced in larger groups, practiced in multispecialty practices, or submitted information through alternative payment models had higher MIPS scores, possibly reflecting the greater infrastructure and resources these practices have to collect, analyze, and report measures to CMS.21,22 Specialties that care for relatively few Medicare patients, such as psychiatry and obstetrics/gynecology, may choose not to invest significant attention or resources in Medicare quality reporting, resulting in relatively low MIPS scores compared with other specialties.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between MIPS scores and patient social risk. These results are consistent with prior research in other value-based programs, suggesting that clinicians and health care organizations serving poorer patients tend to have lower performance scores.23 For example, studies have found that greater patient social risk was associated with lower scores for physicians in the value-based modifier program and that adjustment for social factors substantially narrowed these differences.7,17 Similarly, social factors such as poverty and housing instability seem to be associated with differences in hospital readmission rates but are not currently incorporated into Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program.24,25 Many value-based payment programs may thus penalize clinicians for social factors outside their control and inadvertently transfer resources from those caring for less affluent patients to those caring for more affluent patients—the so-called reverse Robin Hood effect.26

In the first year of MIPS, the potential financial penalties and rewards were relatively small (4% of payment rates).27,28 However, because the program is budget-neutral and because there were more high than low performers in 2017, actual adjustments ranged from a 4.0% penalty to a 1.9% bonus.27 For example, physicians who had a composite MIPS score of 60 received a 0.16% rate increase for services delivered, while those who had a score of 80 received a 0.82% increase.28 This gap may grow substantially in the coming years, as the maximum MIPS penalties and bonuses are set to increase, such that physicians could receive payment adjustments of up to 9% in 2022 based on performance in 2020.27 If there is an imbalance between low and high performers, payment adjustments could be higher than 9%, and small differences in scores could lead to large differences in penalties and rewards.29

Furthermore, the exceptional performance threshold, above which physicians receive additional bonuses, will increase to 85 in 2020.28,30 In 2017, it was given for a score of 70 or above, meaning that the median physician in our highest risk quintile did not receive it, while the median physician in the middle group and lowest risk quintile did.28 Similarly, the minimum score needed to avoid a penalty was 3 in 2017 but increased incrementally each year to 45 in 2020 (and will increase to 60 in 2021).31

While the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission has recommended eliminating MIPS in its current form, Congress has not provided any indication it intends to do so.32 Regardless of what drives differences in MIPS scores across the spectrum of patient social risk, CMS could consider levers to ensure it compares physicians with similar patients. CMS could, for example, compare physicians only within the same category of patient social risk.23,33 While CMS has recently introduced policies aimed at supporting practices serving high proportions of medically and socially complex patients, these may not be effective in reducing differences in MIPS scores and payment associated with patient social risk. For example, CMS has introduced a “complex patient bonus” of up to 5 points based on the average HCC score and proportion of dually eligible patients under a clinician’s care. However, CMS’ own analysis suggests this is unlikely to substantially reduce differences in MIPS scores.34

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, dual eligibility was used as a proxy for social risk. While many other studies have also done so, dual eligibility may not fully capture patients with social disadvantage, and dual-eligibility criteria vary from state to state.35,36,37 Second, because this study was cross-sectional, it could not determine whether a causal link exists between patient social risk and MIPS performance, although efforts were made to control for confounders, including medical risk and various practice characteristics. Third, this study focused on the first year of MIPS, the only year for which data are available. Fourth, in the absence of patient-level data on outcomes, it was not possible to examine whether differences in scores reflected worse care quality or more limited ability to effectively collect and report various MIPS measures.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional analysis of physicians who participated in the first year of the Medicare MIPS program, physicians with the highest proportion of patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid had significantly lower MIPS scores compared with other physicians. Further research is needed to understand the reasons underlying the differences in physician MIPS scores by levels of patient social risk.

eFigure 1. Generation of the Analytic Sample

eFigure 2. Mean Physician MIPS Scores by Ventile of Patient Social Risk, Adjusted and Unadjusted for Physician and Practice Characteristics

eTable 1. Characteristics of Observations Excluded From the Analytic Sample

eTable 2. Mean Adjusted Physician MIPS Scores by Patient Panel Social Risk and Source of Score

eTable 3. Association Between Adjusted MIPS Quality Domain Scores and Physician Characteristics Among Physicians With Patients of High Social Risk

eTable 4. Association Between Adjusted MIPS scores and Physician Characteristics Among Physicians With Patients of High Social Risk, After Adjustment for State Fixed Effects

eReferences

References

- 1.Navathe AS, Dinh CT, Chen A, Liao JM Findings and implications from MIPS year 1 performance data. Health Affairs Published January 18, 2019. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190117.305369/full/

- 2.Frakt AB, Jha AK. Face the facts: we need to change the way we do pay for performance. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(4):291-292. doi: 10.7326/M17-3005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee GM, Kleinman K, Soumerai SB, et al. Effect of nonpayment for preventable infections in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(15):1428-1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardach NS, Wang JJ, De Leon SF, et al. Effect of pay-for-performance incentives on quality of care in small practices with electronic health records: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(10):1051-1059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werner RM, Kolstad JT, Stuart EA, Polsky D. The effect of pay-for-performance in hospitals: lessons for quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):690-698. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine Accounting for Social Risk Factors in Medicare Payment: Identifying Social Risk Factors National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Published 2016. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/21858/accounting-for-social-risk-factors-in-medicare-payment-identifying-social [PubMed]

- 7.Chen LM, Epstein AM, Orav EJ, Filice CE, Samson LW, Joynt Maddox KE. Association of practice-level social and medical risk with performance in the Medicare physician value-based payment modifier program. JAMA. 2017;318(5):453-461. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McWilliams JM. MACRA: big fix or big problem? Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(2):122-124. doi: 10.7326/M17-0230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joynt KE, Zuckerman R, Epstein AM. Social risk factors and performance under Medicare’s value-based purchasing programs. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(5):e003587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu J, Kind AJH, Nerenz D. Area Deprivation Index predicts readmission risk at an urban teaching hospital. Am J Med Qual. 2018;33(5):493-501. doi: 10.1177/1062860617753063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chien AT, Wroblewski K, Damberg C, et al. Do physician organizations located in lower socioeconomic status areas score lower on pay-for-performance measures? J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):548-554. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1946-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sequist TD, Fitzmaurice GM, Marshall R, Shaykevich S, Safran DG, Ayanian JZ. Physician performance and racial disparities in diabetes mellitus care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(11):1145-1151. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Physician Compare datasets. Data.Medicare.Gov. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://data.medicare.gov/data/physician-compare

- 14.Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data: Physician and Other Supplier. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Updated November 19, 2019. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Physician-and-Other-Supplier

- 15.Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty (MD-PPAS). Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Published 2018. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/md-ppas

- 16.OneKey Web. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states/solutions/commercial-operations/essential-information/onekey-reference-assets/onekey-web

- 17.Roberts ET, Zaslavsky AM, McWilliams JM. The value-based payment modifier: program outcomes and implications for disparities. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(4):255-265. doi: 10.7326/M17-1740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2019 Merit-based Incentive Payment System complex patient bonus fact sheet. Accessed March 1, 2020. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/0/2019%20Complex%20Patient%20Bonus%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf

- 19.Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) Data Files. Health Resources and Services Administration. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/datafiles.html

- 20.Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Overview. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/overview

- 21.Rosenkrantz AB, Duszak R, Golding LP, Nicola GN. The alternative payment model pathway to radiologists’ success in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(4):525-533. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khullar D, Burke GC, Casalino LP. Can small physician practices survive? sharing services as a path to viability. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1321-1322. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joynt Maddox KE. Financial incentives and vulnerable populations—will alternative payment models help or hurt? N Engl J Med. 2018;378(11):977-979. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1715455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joynt Maddox KE, Reidhead M, Hu J, et al. Adjusting for social risk factors impacts performance and penalties in the hospital readmissions reduction program. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(2):327-336. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fahrenbach J, Chin MH, Huang ES, Springman MK, Weber SG, Tung EL. Neighborhood disadvantage and hospital quality ratings in the Medicare Hospital Compare Program. Med Care. 2020;58(4):376-383. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joynt KE, Jha AK. Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342-343. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.94856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Program; Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and Alternative Payment Model (APM) incentive under the Physician Fee Schedule, and criteria for physician-focused payment models: final rule with comment period. Fed Regist. 2016;81(214):77008-77831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.2019 MIPS rules. MDinteractive. Published July 12, 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020. https://mdinteractive.com/2019-mips-rules

- 29.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Published March 2019. Accessed August 5, 2020. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar20_entirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

- 30.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Program; CY 2020 Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment Policies. 84 FR 62568. Published November 15, 2019. Accessed August 7, 2020. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/11/15/2019-24086/medicare-program-cy-2020-revisions-to-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-and-other

- 31.MIPS 2020 Final Rule now available—what does it mean for you? MDinteractive. Published November 4, 2019. Accessed June 18, 2020. https://mdinteractive.com/mips-blog/mips-2020-final-rule-now-available-what-does-it-mean-you

- 32.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy: Chapter 15: Moving Beyond the Merit-based Incentive Payment System. Published March 2018. Accessed August 7, 2020. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch15_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

- 33.Joynt KE, De Lew N, Sheingold SH, Conway PH, Goodrich K, Epstein AM. Should Medicare value-based purchasing take social risk into account? N Engl J Med. 2017;376(6):510-513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1616278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS): scoring 101 guide for the 2019 performance year. Accessed March 1, 2020. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/0/2019%20MIPS%20Scoring%20Guide.pdf

- 35.Roberts ET, Mellor JM, McInerney M, Sabik LM. State variation in the characteristics of Medicare-Medicaid dual enrollees: implications for risk adjustment. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(6):1233-1245. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Courtemanche C, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D.. Impacts of the Affordable Care Act on Health Insurance Coverage in Medicaid Expansion and Non-Expansion States. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2016. doi: 10.3386/w22182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Courtemanche CJ, Marton J, Yelowitz A. Medicaid Coverage Across the Income Distribution Under the Affordable Care Act. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2019. doi: 10.3386/w26145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Generation of the Analytic Sample

eFigure 2. Mean Physician MIPS Scores by Ventile of Patient Social Risk, Adjusted and Unadjusted for Physician and Practice Characteristics

eTable 1. Characteristics of Observations Excluded From the Analytic Sample

eTable 2. Mean Adjusted Physician MIPS Scores by Patient Panel Social Risk and Source of Score

eTable 3. Association Between Adjusted MIPS Quality Domain Scores and Physician Characteristics Among Physicians With Patients of High Social Risk

eTable 4. Association Between Adjusted MIPS scores and Physician Characteristics Among Physicians With Patients of High Social Risk, After Adjustment for State Fixed Effects

eReferences