Abstract

This study describes trends in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma within the Veterans Health Administration from 2002 to 2018 before and after widespread direct-acting anti–hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment.

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is an important cause of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the US. HCV eradication has been associated with a reduced risk of HCC.1 Despite effective direct-acting antiviral therapies that have been available since 2013, only 14% of patients with HCV in the US were cured as of 2016.2 In contrast, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, provides unrestricted access to HCV treatments and approximately 85% of its case load has achieved cure.3 We examined trends in HCC incidence within the VHA from 2002 to 2018, according to HCV status, to determine whether the burden of HCC changed following mass HCV treatment.

Methods

We identified all patients diagnosed with HCC annually from 2002 to 2018 using electronic health record data. We defined HCC using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (155.0) or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (C22.0) codes validated in VHA health records (positive predictive value, 84%-94%).4,5 Infection with HCV was determined by any history of detectable viral load in VHA data, with cure defined as negative viral load at least 12 weeks after completion of antiviral treatment.6 We categorized patients into 3 groups as of the time of HCC diagnosis: HCC/HCV viremic (latest HCV RNA before HCC diagnosis was positive), HCC/HCV cured (HCV eradicated before HCC diagnosis), and HCC/non-HCV (no positive lifetime HCV RNA). Total HCV-related HCC (HCC/HCV total) consisted of the sum of HCC/HCV viremic plus HCC/HCV cured.

We calculated the annual incidence of HCC among all patients receiving VHA health care each year and HCV-related HCC among patients with a history of HCV. We used interrupted time-series analysis to test whether incidence for all-cause HCC, HCC/HCV total, and HCC/non-HCV changed after 2015. We obtained the number of antiviral treatments initiated each year.

The institutional review board of the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Healthcare System approved the study and waived informed consent. The analysis was performed using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp). A 2-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

The incidence of HCC/HCV total in the VHA increased from 2000 to 2015, peaked in 2015 at 31.0 per 100 000 patients receiving VHA care, then declined 29.6% to 21.8 per 100 000 patients receiving VHA care in 2018 (Table). Among patients with a history of HCV, HCC incidence peaked in 2015 (1061 per 100 000 patients with HCV receiving VHA care) and declined 27.2% to 773 per 100 000 patients with HCV receiving VHA care from 2015 to 2018. In an interrupted time-series analysis, incidence decreased after 2015 for both HCC/HCV total and all-cause HCC (P <.001) and increased for HCC/non-HCV (P = .002), with between-group differences in incidence after 2015 for HCC/HCV total vs HCC/non-HCV (P <.001).

Table. Incidence of HCC in the VHA, 2002-2018.

| Year of first HCC diagnosis | VHA population, No.a | HCC in all VHA users | HCC in VHA users with HCV (HCV-related HCC) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause HCC | HCC not associated with HCV (HCC/non-HCV) | HCV-related HCC (HCC/HCV total) | HCC with HCV viremia (HCC/HCV viremic) | HCC with previously treated HCV (HCC/HCV cured) | ||||||||||

| All veterans | HCV | Cases, No. | Incidenceb | Cases, No. | Incidenceb | Cases, No. | Incidenceb | Cases, No. | Incidenceb | Cases, No. | Incidenceb | Cases, No. | Incidencec | |

| 2002 | 4 246 084 | 152 412 | 774 | 18.2 | 609 | 14.3 | 165 | 3.9 | 165 | 3.9 | 0 | 0.00 | 165 | 108.3 |

| 2003 | 4 494 425 | 160 155 | 927 | 20.6 | 651 | 14.5 | 276 | 6.1 | 274 | 6.1 | 2 | 0.04 | 276 | 172.3 |

| 2004 | 4 659 196 | 167 216 | 1120 | 24.0 | 726 | 15.6 | 394 | 8.5 | 384 | 8.2 | 9 | 0.19 | 394 | 235.6 |

| 2005 | 4 806 345 | 170 985 | 1195 | 24.9 | 697 | 14.5 | 498 | 10.4 | 484 | 10.1 | 12 | 0.25 | 498 | 291.3 |

| 2006 | 4 900 800 | 173 898 | 1389 | 28.3 | 755 | 15.4 | 634 | 12.9 | 611 | 12.5 | 22 | 0.45 | 634 | 364.6 |

| 2007 | 4 950 501 | 177 024 | 1589 | 32.1 | 793 | 16.0 | 796 | 16.1 | 781 | 15.8 | 15 | 0.30 | 796 | 449.7 |

| 2008 | 4 999 106 | 181 074 | 1670 | 33.4 | 779 | 15.6 | 891 | 17.8 | 862 | 17.2 | 25 | 0.50 | 891 | 492.1 |

| 2009 | 5 139 285 | 186 668 | 2042 | 39.7 | 848 | 16.5 | 1194 | 23.2 | 1157 | 22.5 | 36 | 0.70 | 1194 | 639.6 |

| 2010 | 5 351 873 | 190 274 | 2253 | 42.1 | 899 | 16.8 | 1354 | 25.3 | 1304 | 24.4 | 47 | 0.88 | 1354 | 711.6 |

| 2011 | 5 499 498 | 191 946 | 2366 | 43.0 | 930 | 16.9 | 1436 | 26.1 | 1393 | 25.3 | 43 | 0.78 | 1436 | 748.1 |

| 2012 | 5 598 829 | 191 955 | 2614 | 46.7 | 1014 | 18.1 | 1600 | 28.6 | 1544 | 27.6 | 54 | 0.96 | 1600 | 833.5 |

| 2013 | 5 720 614 | 181 168 | 2649 | 46.3 | 990 | 17.3 | 1659 | 29.0 | 1598 | 27.9 | 59 | 1.0 | 1659 | 915.7 |

| 2014 | 5 869 487 | 180 439 | 2716 | 46.3 | 972 | 16.6 | 1744 | 29.7 | 1670 | 28.5 | 74 | 1.3 | 1744 | 966.5 |

| 2015 | 5 958 849 | 174 027 | 2863 | 48.0 | 1016 | 17.1 | 1847 | 31.0 | 1694 | 28.4 | 153 | 2.6 | 1847 | 1061.3 |

| 2016 | 5 995 048 | 180 337 | 2824 | 47.1 | 1034 | 17.2 | 1790 | 29.9 | 1390 | 23.2 | 400 | 6.7 | 1790 | 992.6 |

| 2017 | 6 040 248 | 177 924 | 2590 | 42.9 | 1080 | 17.9 | 1510 | 25.0 | 964 | 16.0 | 546 | 9.0 | 1510 | 848.7 |

| 2018 | 6 128 988 | 172 886 | 2468 | 40.3 | 1132 | 18.5 | 1336 | 21.8 | 666 | 10.9 | 670 | 10.9 | 1336 | 772.8 |

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

Total VHA population receiving health care was obtained from the Office of the Assistant Deputy Undersecretary for Health for Policy and Planning as of October 11, 2019.

Incidence calculated as the number of HCC cases per 100 000 veterans in care in each year.

Incidence calculated as the number of HCC cases per 100 000 veterans with a lifetime history of HCV (viremic plus cured) in care in each year.

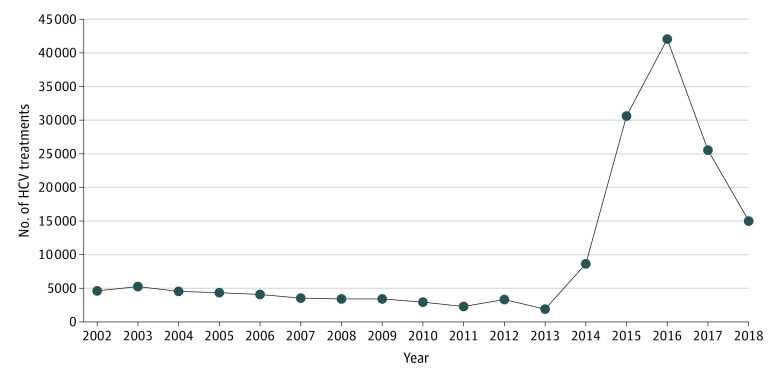

The incidence of HCC/HCV cured increased and the incidence of HCC/HCV viremic decreased after 2013 (Table). In 2018, the number of patients with HCC/HCV cured began exceeding the number of HCC/HCV viremic. Among patients with HCC/HCV cured who were diagnosed with HCC in 2018, the mean time since cure was 2.8 (SD, 2.2) years. Annual HCV antiviral treatments peaked at 42 031 in 2016 (Figure).

Figure. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Treatment Initiations per Year in Individuals Receiving Veterans Health Administration Care, 2002-2018.

Discussion

Incidence of HCV-related HCC among VHA patients decreased from 2015 to 2018 following viral eradication efforts from 2014 to 2016. In contrast, the incidence of non–HCV-related HCC increased after 2015. Although observational data cannot prove causation, the timing of HCV eradication and declining HCC incidence, lack of decline in non–HCV-related HCC, and prior studies demonstrating that HCV eradication reduces HCC risk1 provide indirect evidence that this decline may be related to widespread HCV treatment.

The number of people with HCC/HCV cured increased to exceed that of HCC/HCV viremic because antiviral treatment does not completely eliminate residual HCC risk, especially in patients with advanced fibrosis.6 Among people with HCC/HCV cured, cancer diagnosis occurred a mean of 2.8 years after HCV therapy, further suggesting that HCV will continue to be an important cause of HCC even after managing the majority of HCV infections.

Limitations of this study include the use of International Classification of Diseases codes to define HCC rather than chart review; the VHA population, with unknown generalizability; lack of data on liver disease severity prior to treatment; and the short term of the study. HCC incidence trends should continue to be monitored closely because patients cured of HCV may have yet to experience the full potential of risk reduction. These findings support large-scale HCV elimination campaigns, with continued vigilance for HCC in those achieving eradication.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Meringer H, Shibolet O, Deutsch L. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the post-hepatitis C virus era: should we change the paradigm? World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(29):3929-3940. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i29.3929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chirikov VV, Marx SE, Manthena SR, Strezewski JP, Saab S. Development of a comprehensive dataset of hepatitis C patients and examination of disease epidemiology in the United States, 2013-2016. Adv Ther. 2018;35(7):1087-1102. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0721-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belperio PS, Chartier M, Ross DB, Alaigh P, Shulkin D. Curing hepatitis c virus infection: best practices from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(7):499-504. doi: 10.7326/M17-1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramer JR, Giordano TP, Souchek J, Richardson P, Hwang LY, El-Serag HB. The effect of HIV coinfection on the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in U.S. veterans with hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(1):56-63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40670.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davila JA, Henderson L, Kramer JR, et al. . Utilization of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among hepatitis C virus-infected veterans in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):85-93. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ioannou GN, Beste LA, Green PK, et al. . Increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma persists up to 10 years after HCV eradication in patients with baseline cirrhosis or high FIB-4 scores. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(5):1264-1278. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]