Abstract

To enhance compensation for primary care activities that occur outside of face-to-face visits, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently introduced new billing codes for transitional care management (TCM) and chronic care management (CCM) services. Overall, rates of adoption of these codes have been low. To understand the patterns of adoption, we compared characteristics of the practices that billed for these services to those of the practices that did not and determined the extent to which a practice other than the beneficiary’s usual primary care practice billed for the services. Larger practices and those using other novel billing codes were more likely to adopt TCM or CCM. Over a fifth of all TCM claims and nearly a quarter of all CCM claims were billed by a practice that was not the beneficiary’s assigned primary care practice. Our results raise concerns about whether these codes are supporting primary care as originally expected.

The core features of primary care—first contact care that is continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated1—are poorly supported under the current fee-for-service reimbursement system, which largely restricts outpatient payments to payments for office-based visits. Indeed, a large and potentially growing share of primary care activities are not recognized in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.2–7 Such non-visit-based services include, for example, providing care via phone or electronic messaging, coordinating with staff and other providers in the care of complex patients, and managing population health.

To compensate physicians and their practices for activities that occur outside of traditional face-to-face visits, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced two new payment codes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for services related to transitional care management (TCM) and chronic care management (CCM). Both codes are designed to reimburse practices for coordinating the care of eligible Medicare beneficiaries separate from office visits. This in turn could improve the quality of care and decrease the downstream use of health care services, such as emergency department visits, preventable hospitalizations, and readmissions.8–10 Although the codes can be used by specialists, it was envisioned that the codes would be used most frequently by primary care practitioners.11–13 Therefore, by reimbursing primary care practices for services they frequently provided without any additional compensation, these new codes represent a step toward reducing the large payment disparities that exist between primary care physicians and other specialists.

TCM, introduced in 2013, is designed to facilitate the transition from hospital to home. Billing for a TCM service requires contact with the patient within two days of discharge (either in person or by email or telephone); a dedicated office visit within seven or fourteen days of hospital discharge (depending on complexity); and additional care coordination services outside the office visit over the thirty days following discharge, such as reviewing discharge documents or following up on pending tests.14,15 CCM, introduced in 2015, is a service designed to promote enhanced care coordination for chronically ill patients with multiple conditions. Billing for a CCM service requires the development of a comprehensive care management plan followed by the provision of at least twenty minutes of non-visit-based services per month (for example, reviewing lab results, communicating with specialists, or making adjustments to a patient’s treatment regimen), which can be provided by physicians or their supervised clinical staff members.16,17

TCM and CCM payments represent a potentially important source of additional revenue for primary care practices.18 However, uptake of both codes has been low.19–21 In 2016, TCM and CCM services were delivered to only 9.3 percent and 2.3 percent of potentially eligible beneficiaries, respectively.21 To better understand the adoption of these services, we used Medicare data to examine variation in the uptake of TCM and CCM billing among primary care, specialty, and other types of practices. We sought to understand the characteristics of practices that provided these services as well as the characteristics of patients who received them. An understanding of the uptake of these newly billable services could help inform Medicare’s evolving strategy in optimizing payment for primary care services.

Study Data and Methods

Data Source

We analyzed Medicare claims and enrollment data for 2016 for a random 20 percent sample of fee-for-service beneficiaries as well as data for the period 2010–16 for trend analyses. We included adult beneficiaries (ages eighteen and older) who were enrolled in traditional Medicare for at least one month. Patients with end-stage renal disease were excluded from the analysis, since they do not qualify for TCM or CCM services.

We identified TCM claims for 2013–16 using the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 99495 or 99496 and identified CCM claims for 2015–16 using the CPT code 99490. A beneficiary was considered to have received TCM or CCM services if he or she had at least one claim for either service in the calendar year.

Identifying Practices

To identify distinct provider practices, we used taxpayer identification numbers (TINs), which represent billing entities for professional services in Medicare claims. A single TIN can represent a solo practitioner, a small physician group, or a larger provider organization. A practice was considered to have engaged in providing TCM or CCM services if it billed for the corresponding service at least once in the calendar year. We assigned physicians to one or more practices based on the TIN or TINs through which their claims were billed.

Evaluation and management services are traditionally delivered in the office setting, so we defined office-based practices as those TINs that billed for five or more evaluation and management services (that is, CPT codes 99201–99205, 99211–99215, G0438, G0439, or G0463). We identified primary care practices as office-based practices with at least one primary care physician associated with the practice. For practices with at least ten assigned beneficiaries, we also identified high-adopting practices. We defined these as office-based practices in the top quartile of delivering TCM or CCM services to their eligible patients in the most recent year.

Assigning Beneficiaries To Practices

Using the attribution rules for the Medicare Shared Savings Program,22 we assigned beneficiaries to the practice that billed for the plurality of their evaluation and management services during the year before the delivery of a TCM service or during the year of a CCM service. Beneficiaries were first assigned based on the plurality of evaluation and management services delivered by a primary care physician (a physician specializing in internal medicine, family medicine, general practice, or geriatrics). Beneficiaries who received no services from a primary care physician were assigned based on evaluation and management services delivered by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or specialists.23–25 Thus, to the extent that patients elected to receive care only from a specialist, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant, that provider would serve as the patient’s assigned primary care provider. See the online appendix for additional details.26

Measures

Practice Characteristics:

We characterized practices based on size (number of physicians), primary care orientation (percentage of physicians with a primary care specialty), setting (metropolitan, micropolitan, small town, or rural),26 region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West), Medicare panel size (number of Medicare beneficiaries per primary care physician, in tertiles), racial composition (percentage of patients within a practice who were nonwhite, in tertiles), Medicaid dual enrollment (percentage of patients within a practice who were dually enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare, in tertiles), participation in a Medicare accountable care organization (ACO; practices in which a majority of beneficiaries were attributed to either a Medicare Shared Savings Program or a Pioneer ACO), uptake of the other care management code (in the TCM analysis, practices that provided CCM, and vice versa), and uptake of the annual wellness visit (a yearly preventive visit offered at no cost to Medicare beneficiaries). Introduced in 2011, the annual wellness visit has a relatively novel code that, similar to the codes for TCM and CCM, enables primary care practices to generate additional revenue by adopting new care delivery approaches to address the health risks of aging adults.27 A detailed definition of each practice characteristic is available in the appendix.26

Patient Characteristics:

We characterized patients by sex, age (ages 18–64, 65–74, 75–84, or 85 and older), race (white, black, or other), family income (low, medium, or high, based on the median family income in the beneficiary’s ZIP code from census data), setting (metropolitan, micropolitan, small town, or rural), region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West), Medicaid dual enrollment status, and number of comorbidities (based on 27 chronic conditions captured by the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse)28 (for a list of the co-morbidities, see the appendix).26

Statistical Analysis:

We assessed the uptake of TCM and CCM across practices by using the total numbers of claims and beneficiaries in 2016. We next compared the characteristics of primary care practices that billed for any TCM or CCM services to those of practices that did not, and we used a logistic regression model to adjust for practice characteristics. We then determined whether patient characteristics were associated with the receipt of TCM or CCM services.

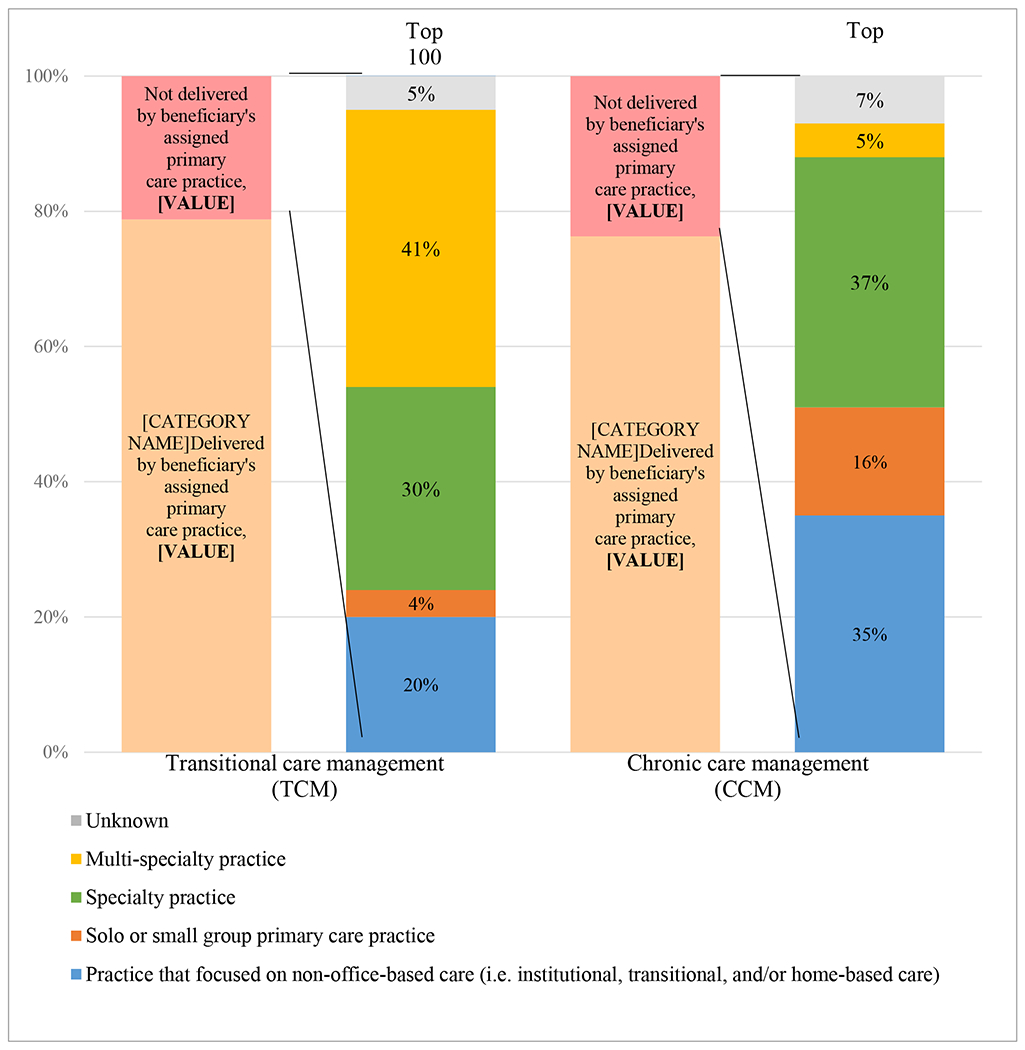

We also determined the extent to which TCM or CCM was billed and delivered by a practice other than the primary care practice to which the beneficiary was assigned. For the top hundred such practices, we used publicly available data to characterize the type of practice: a practice that focused on non-office-based care (that is, institutional, transitional, or home-based care), a solo or small-group primary care practice, a specialty practice, or a large multispecialty practice (for the process used to characterize the type of practice, see the appendix).26

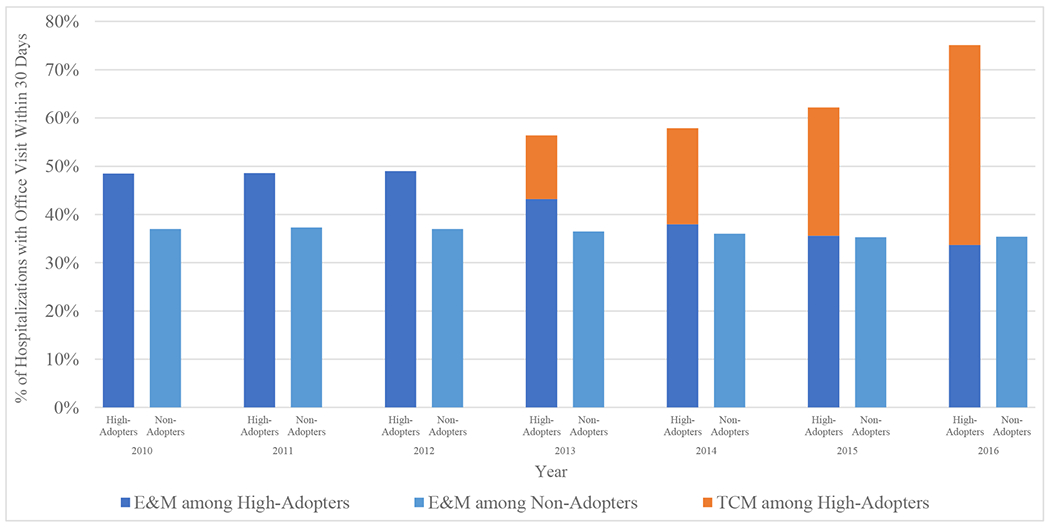

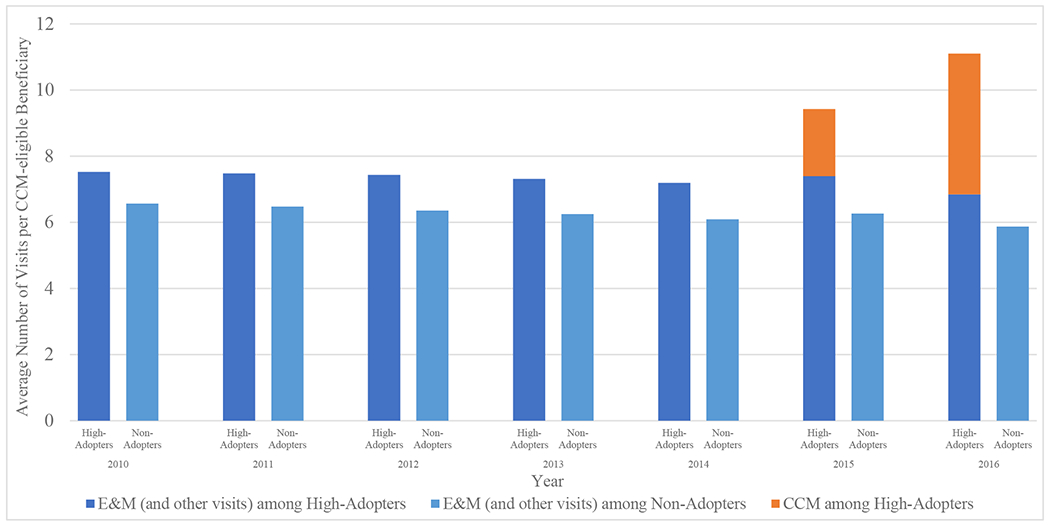

Finally, to examine potential substitutive or additive effects on traditional office visits resulting from the adoption of CCM, we used data for 2010–16 and compared the trend in the yearly number of office visits (including evaluation and management, TCM, and annual wellness visits) versus the yearly number of CCM visits per potentially eligible beneficiary, in high-adopting practices versus nonadopting ones. Similarly, to examine the potential substitutive or additive effects on evaluation and management visits from the adoption of TCM, we compared the trend in the annual percentage of hospitalizations with an evaluation and management visit versus a TCM visit within thirty days of a discharge, in high-adopting practices versus nonadopting ones. We chose thirty days because although the TCM office visit must occur within seven or fourteen days of discharge, many TCM claims are filed toward the end of the thirty-day TCM period.

Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4. This study was approved by the Office of Research Protection at Harvard Medical School.

Limitations

Our analyses were subject to several limitations. First, we defined practices using TINs, which do not necessarily represent a consistent level of organization: In some cases, multiple clinics within a single umbrella organization may bill under the same TIN. Conversely, a single clinic may bill using multiple TINs.

Second, we relied on an attribution algorithm to assign patients to practices. This assignment method has been used in many prior studies,23–25 but residual inaccuracies may persist.29

Third, we lacked information on other important patient attributes that might influence the use of and need for non-visit-based services—including functional status, cognition, and preferred language.

Fourth, we relied on a 20 percent random sample of fee-for-service beneficiaries for our analyses. Random sampling variation limits the ability to estimate the volume of services at the practice level. However, most of our analyses focused on comparisons of practices or patients receiving TCM or CCM services and trends in their use, both of which should be unbiased with the use a 20 percent sample.

Finally, further research is needed to understand the impact of these additional billable services on patient outcomes and total costs of care.

Study Results

In 2016, 11,430 practices billed for at least one TCM service, and 3,847 practices billed for at least one CCM service. (Restricting to primary care practices only, 10,384 practices billed for at least one TCM, and 3,347 practices billed for at least one CCM service.) Within adopting practices, the median practice billed for five TCM services (interquartile range: 2–12) collectively provided to four beneficiaries (IQR: 2–10). This equated to an estimated twenty-five TCM services among twenty beneficiaries when we projected from the 20 percent sample to all traditional fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries (appendix exhibit 1).26 Similarly, the median practice billed for 26 CCM services (IQR: 6–100) provided to eleven beneficiaries (IQR: 3–29), which equated to an estimated 130 CCM services among fifty-five beneficiaries.

Practice And Patient Characteristics

Compared to primary care practices that did not engage in TCM or CCM services, those that did were larger (18.5 percent of TCM practices had eleven or more physicians versus 7.0 percent of non-TCM practices, as did 18.8 percent of CCM practices versus 8.8 percent of non-CCM practices) (exhibit 1). Practices that did engage in the services had more Medicare beneficiaries per primary care physician (49.3 percent of TCM practices were in the top tertile versus 28.1 percent for non-TCM practices, as were 51.2 percent of CCM practices versus 31.3 percent of non-CCM practices). And they were more likely to be participating in an ACO (23.7 percent of TCM practices versus 12.4 percent of non-TCM practices, and 24.5 percent of CCM practices versus 14.1 percent of non-CCM practices).

Exhibit 1:

Characteristics of primary care practices that did or did not engage in transitional care management (TCM) or chronic care management (CCM), 2016

| Practices engaged in any TCM (%) | Practices engaged in any CCM (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Yes (n = 10,384) | No (n = 37,846) | Yes (n = 3,347) | No (n = 44,883) |

| Number of physicians | ||||

| 1 | 46.7 | 64.4 | 42.2 | 62.0 |

| 2–10 | 34.8 | 28.6 | 39.0 | 29.3 |

| 11 or more | 18.5 | 7.0 | 18.8 | 8.8 |

| Mean share of physicians in a practice who were primary care | 85.9 | 86.4 | 84.8 | 86.4 |

| Medicare beneficiaries per primary care physician | ||||

| First tertile (0–24) | 13.6 | 40.6 | 14.0 | 36.4 |

| Second tertile (>24–56) | 37.1 | 31.3 | 34.8 | 32.4 |

| Top tertile (>56) | 49.3 | 28.1 | 51.2 | 31.3 |

| Settinga | ||||

| Metropolitan | 81.8 | 83.3 | 81.9 | 83.1 |

| Micropolitan | 12.6 | 9.4 | 11.6 | 9.9 |

| Small town | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| Rural | 4.1 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 4.7 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 23.7 | 20.5 | 18.2 | 21.4 |

| Midwest | 18.4 | 16.3 | 15.4 | 16.9 |

| South | 41.4 | 40.8 | 48.1 | 40.4 |

| West | 16.6 | 22.5 | 18.3 | 21.4 |

| Percent of nonwhite patients | ||||

| First tertile (0–7%) | 29.3 | 23.9 | 23.8 | 25.2 |

| Second tertile (>7–23%) | 38.3 | 30.5 | 38.4 | 31.7 |

| Top tertile (>23%) | 32.4 | 45.6 | 37.8 | 43.1 |

| Percent of dually enrolledb patients | ||||

| First tertile (0–8%) | 29.2 | 29.8 | 26.7 | 29.9 |

| Second tertile (>8–25%) | 39.7 | 30.5 | 38.1 | 32.1 |

| Top tertile (>25%) | 31.1 | 39.7 | 35.2 | 38.0 |

| Medicare ACO participationc | 23.7 | 12.4 | 24.5 | 14.1 |

| Uptake of other care management coded | 19.7 | 3.5 | 61.7 | 18.9 |

| Uptake of AWVe | 87.6 | 45.9 | 90.1 | 52.3 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data 2016 for a 20 percent random sample of Medicare beneficiaries. NOTES Primary care practices are office-based practices (that is, practices with five or more evaluation and management visits) with at least one primary care physician. All differences between practices that engaged in any TCM or CCM versus those that did not engage were significant (adjusted p <0.001, based on chi-square tests for homogeneity across engaged and not engaged practices), except for mean share of physicians in a practice who were primary care for TCM (p = 0.117) and for CCM (p = 0.005) and setting for CCM (p = 0.140). Models were adjusted for all practice characteristics included in the exhibit.

Based on rural-urban commuting area codes from census data.

Dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid.

A practice was considered to be participating in an accountable care organization (ACO) if the majority of beneficiaries attributed to the practice belonged to a Medicare Shared Savings Program ACO or a Pioneer ACO.

In the TCM analysis, uptake of other care management code refers to practices that billed for at least one CCM in the same year. In the CCM analysis, uptake of other care management code refers to practices that billed for at least one TCM in the same year.

Uptake refers to practices that provided at least one annual wellness visit (AWV) in 2016.

Primary care practices that engaged in TCM or CCM services were significantly more likely to have used both codes (19.7 percent of TCM practices versus 3.5 percent of non-TCM practices, and 61.7 percent of CCM practices versus 18.9 percent of non-CCM practices). They were also more likely to have adopted Medicare’s annual wellness visit (87.6 percent of TCM practices versus 45.9 percent of non-TCM practices, and 90.1 percent of CCM practices versus 52.3 percent of non-CCM practices).

Patients who received either TCM or CCM were older and had more comorbidities than those who did not (appendix exhibit 2).26 Patients dually enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare were less likely to have received TCM but more likely to have received CCM, compared to those not dually enrolled.

Billing By Non-Primary-Care Practices

Over a fifth (21.2 percent) of all TCM claims and about a quarter (23.7 percent) of all CCM claims were billed by a practice other than a beneficiary’s assigned primary care practice (exhibit 2). Less than 3 percent of TCM and CCM services were delivered to a beneficiary who did not have an assigned primary care practice (appendix exhibit 3).26 Among the top hundred practices that billed for TCM services but were not the assigned primary care practice, 41 percent were multispecialty practices that were often affiliated with or part of a larger hospital system, 30 percent were specialty practices, and 20 percent were practices that focused on non-office-based care (exhibit 2). Among the top hundred practices that billed for CCM services but were not the assigned primary care practice, 37 percent were specialty practices, and 35 percent were practices that focused on non-office-based care.

Exhibit 2:

Percentage of claims and characteristics of the top 100 practices where TCM or CCM was not delivered by a beneficiary’s assigned primary care practice, 2016

Source: Authors’ analysis of data for a 20% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries. Notes: Claims without an associated TIN were excluded from this analysis i.e. of the 181,900 TCM claims, 5,318 did not have an associated TIN, and of 474,192 CCM claims, 6,169 did not have an associated TIN. The total number of TCM or CCM claims accounted by top 100 practices where TCM or CCM was not delivered by a beneficiary’s assigned primary care practice was 7,814 for TCM (21% of all such claims) and 67,202 for CCM (61% of all such claims).

| TCM | CCM | |

|---|---|---|

| Delivered by beneficiary’s assigned primary care practice | 78.8% | 76.3% |

| Not delivered by beneficiary’s assigned primary care practice | 21.2% | 23.7% |

| TCM | CCM | |

|---|---|---|

| Practice that focused on non-office-based care (i.e. institutional, transitional, and/or home-based care) | 20% | 35% |

| Solo or small group primary care practice | 4% | 16% |

| Specialty practice | 30% | 37% |

| Multi-specialty practice | 41% | 5% |

| Unknown | 5% | 7% |

Potential Substitution Or Additive Effects

High-adopting practices (i.e. those in the top quartile of delivering TCM or CCM services to their eligible patients) provided TCM services to at least 22.9 percent of their eligible discharges or CCM services to at least 40.0 percent of their eligible patients in 2016. The introduction of TCM in 2013 was associated with an increase in the proportion of hospitalizations followed by an office visit (whether a TCM or an evaluation and management visit) among high-adopting practices (exhibit 3). Between 2013 and 2016, an increasing proportion of postdischarge visits were TCM visits, and a modestly decreasing proportion of postdischarge visits were evaluation and management visits. This annual trend was consistent with TCM visits’ both substituting for and adding to traditional office visits after hospital discharge. Among high-adopting practices, 75.1 percent of hospitalizations had an office or a TCM visit within thirty days of hospital discharge in 2016, compared to 48.5 percent in 2010.

Exhibit 3:

Potential substitutive or additive effects on post-discharge office visits from adoption of TCM, 2010–2016

Source: Authors’ analysis of data for a 20% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries. Notes: We calculated the percent of hospitalizations with an office visit within 30 days of discharge, whether an evaluation and management (E&M) visit or TCM visit. E&M visits are non-specific and could have been related or unrelated to the preceding hospitalization. High-adopters (n = 1,223) included those practices (with or without a primary care physician) that were in the top quartile of delivering TCM services to their eligible patients. Non-adopters (n = 24,993) provided TCM to 0% of their eligible patients.

| E&M among High-Adopters | E&M among Non-Adopters | TCM among High-Adopters | TCM among Non-Adopters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | High-Adopters | 48.5% | 0.0% | ||

| Non-Adopters | 37.0% | 0.0% | |||

| 2011 | High-Adopters | 48.6% | 0.0% | ||

| Non-Adopters | 37.3% | 0.0% | |||

| 2012 | High-Adopters | 49.0% | 0.0% | ||

| Non-Adopters | 37.0% | 0.0% | |||

| 2013 | High-Adopters | 43.2% | 13.2% | ||

| Non-Adopters | 36.5% | 0.0% | |||

| 2014 | High-Adopters | 38.0% | 19.9% | ||

| Non-Adopters | 36.0% | 0.0% | |||

| 2015 | High-Adopters | 35.6% | 26.6% | ||

| Non-Adopters | 35.3% | 0.0% | |||

| 2016 | High-Adopters | 33.7% | 41.4% | ||

| Non-Adopters | 35.4% | 0.0% |

Similarly, the introduction of CCM in 2015 was associated with an increase in the total number of visits per year (whether CCM or office visits) among eligible beneficiaries in high-adopting practices (exhibit 4). The number of office visits remained relatively unchanged. Instead, the increase in the total number of visits was associated with additional CCM visits. This annual trend was consistent with CCMs’ being primarily additive and not replacing existing office visits.

Exhibit 4:

Potential substitutive versus additive effects on traditional offices visits from adoption of CCM, 2010–2016

Source: Authors’ analysis of data for a 20% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries. Notes: We calculated the number of visits received at each practice per eligible beneficiary (i.e. at least 2 chronic conditions). Baseline office visits included evaluation and management (E&M) visits and other types of office visits i.e. annual wellness visits (AWV) and TCM. High-adopters (n = 577) included those practices (with or without a primary care physician) that were in the top quartile of delivering CCM services to their eligible patients. Non-adopters (n = 31,212) provided CCM to 0% of their eligible patients.

| E&M (and other visits) among High-Adopters | E&M (and other visits) among Non-Adopters | CCM among High-Adopters | CCM among Non-Adopters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | High-Adopters | 7.52 | 0 | ||

| Non-Adopters | 6.56 | 0 | |||

| 2011 | High-Adopters | 7.48 | 0 | ||

| Non-Adopters | 6.47 | 0 | |||

| 2012 | High-Adopters | 7.43 | 0 | ||

| Non-Adopters | 6.35 | 0 | |||

| 2013 | High-Adopters | 7.31 | 0 | ||

| Non-Adopters | 6.25 | 0 | |||

| 2014 | High-Adopters | 7.19 | 0 | ||

| Non-Adopters | 6.09 | 0 | |||

| 2015 | High-Adopters | 7.39 | 2.03 | ||

| Non-Adopters | 6.26 | 0 | |||

| 2016 | High-Adopters | 6.84 | 4.26 | ||

| Non-Adopters | 5.87 | 0 |

Discussion

In this national study of the provision of newly reimbursed primary care services to Medicare beneficiaries, we found that larger practices and those that adopted other novel billing codes such as that for the annual wellness visit were more likely to bill for TCM or CCM services. Moreover, approximately a fifth of TCM claims and a quarter of CCM claims were billed by practices other than a beneficiary’s assigned primary care practice. In comparison, over 90 percent of annual wellness visits were billed by the assigned primary practice.27 These additional billing codes were introduced by CMS as part of a broader strategy to not only encourage enhanced care coordination but also provide additional reimbursement for primary care services previously unrecognized in the Physician Fee Schedule—particularly those services that occur outside of the traditional face-to-face encounter.30 However, to the extent that these codes were expected to support primary care, our findings raise several concerns about whether payments for TCM and CCM are accomplishing this goal.

Several factors may account for the higher uptake among larger practices—a group that includes both practices that are part of larger health care systems and large, independent practices. Larger practices naturally have more beneficiaries who would be eligible for TCM or CCM. They benefit from economies of scale that raise the potential revenue from these codes, relative to their costs. Although some small practices have successfully implemented TCM or CCM services, in general, smaller practices may be less likely to adopt TCM or CCM services because they do not care for enough Medicare beneficiaries to justify changing how they provide care.31 Furthermore, larger practices may be better equipped to provide these services. They are more likely to have the financial and managerial resources needed to develop the infrastructure (for example, electronic medical records and additional personnel) and ensure compliance.

Although TCM and CCM were intended to support primary care, our findings raise the concern that, in some cases, the codes are not being adopted as expected. First, we found that, conditional on our assignment methodology, a nontrivial proportion of TCM and CCM services were being delivered by practices other than the beneficiary’s assigned primary care practice. This pattern was particularly true for CCM services. Such practices included not only specialty practices but also practices that specialized specifically in providing institutionally based services, postacute care services, or home-based services. Although it remains unclear whether such practices provide any improvement in care for beneficiaries, there is some qualitative evidence that the use of third-party vendors that provide CCM services led to increasingly fragmented care.32 Second, the codes were meant to help bring additional resources to all types of primary care practices, yet as discussed above, the adoption of TCM and CCM was much greater among larger practices. Small practices, which are more likely to be physician owned, are a vital component of primary care,33–36 but they appear to be less likely to benefit from these new codes.

Another key consideration is the potential financial impact of these codes on Medicare beneficiaries. Both TCM and CCM are subject to the deductible and 20 percent coinsurance requirements under Medicare Part B. Thus, for CCM, patients would incur a monthly charge that would total about $100 per year.16 We observed that dually enrolled beneficiaries were more likely to receive CCM services than non-dually-enrolled beneficiaries were—possibly because Medicaid would cover the monthly charge. Patients without supplemental insurance, such as a Medigap policy, may be reluctant to incur new out-of-pocket spending for CCM. Furthermore, physicians might find discussions about the cost of these services to be uncomfortable or find it difficult to offer these services to just the subset of patients who can or are willing to pay.

To better understand how TCM and CCM are being used by practices, we also examined whether trends in the adoption of the codes for these services were consistent with a pattern of substituting or supplementing traditional office visits. CCM services appeared to be supplementing office visits in high-adopting practices, which suggests that this further investment in care coordination was not decreasing the use of in-office care. Trends in the use of TCM services showed that postdischarge visits were increasingly being billed as TCM rather than evaluation and management visits, which suggests that these practices may be making a more concerted effort to both turn traditional office visits into TCM visits and see more hospitalized patients after discharge in clinic. One study has suggested that the adoption of TCM led to fewer hospital readmissions, lower health care costs, and reduced mortality in the period 31–60 days after discharge.19

Codes for TCM and CCM are just two of several codes recently introduced to the Physician Fee Schedule for primary care practices. Other new codes provide payment for the provision of an annual wellness visit, advance care planning, cognitive impairment assessment, behavioral health integration, and telehealth services. Although the new billing codes have been welcomed by many primary care physicians,37,38 each code comes with its own distinct set of rules and requirements, and in the aggregate, these can become onerous. Moreover, the breadth of primary care may be greater than one-off codes can capture.

In response to feedback from providers, CMS changed several of the requirements of CCM in 2017 to encourage greater uptake among practices—for instance, adding CCM codes that allow for higher payments and simplifying some of the administrative rules.39 Whether these changes had any effect remains to be seen, but our analysis suggests that CMS faces two related challenges: how to increase uptake and how to do so specifically among primary care practices. CMS might consider streamlining rules (including documentation requirements), eliminating cost sharing (particularly for CCM), and encouraging other payers to adopt similar codes. Additionally, CMS might consider auditing the use of the codes by non-primary-care practices or modifying the regulations to restrict the types of providers that can bill using these codes.32

In summary, our results suggest that some providers are successfully implementing TCM and CCM services into their practices and billing for them. However, our results also raise concerns that the adoption of TCM and CCM has been concentrated in larger practices and that practices other than the beneficiary’s assigned primary care practice are using these codes to a nontrivial degree. Further investigation will be needed to determine the extent to which these services improve care coordination, mitigate health risks in aging adults, and improve outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

An earlier version of this work was presented as an oral presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine in Denver, Colorado, April 14, 2018, and as a poster presentation at the Annual Research Meeting of AcademyHealth in Seattle, Washington, in June 24, 2018. Sumit Agarwal’s salary is supported by a National Research Service Award for Primary Care (Award No. T32-HP10251) from the Health Resources and Services Administration and the Ryoichi Sasakawa Fellowship Fund. Michael Barnett has received funding from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. K23 AG058806). Bruce Landon has received funding from the National Institute on Aging (Grant No. P01 AG032952).

Biographies

Bios for 2019–00329_Agarwal

Bio 1: Sumit D. Agarwal (sagarwal14@bwh.harvard.edu) is a primary care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston, Massachusetts and a PhD candidate in health policy at Harvard University, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Bio 2: Michael L. Barnett is an assistant professor of health policy and management in the Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, in Boston, and a primary care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Bio 3: Jeffrey Souza is a programmer and biostatistician in the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, in Boston.

Bio 4: Bruce E. Landon is a professor in the Departments of Health Care Policy and of Medicine and a faculty member in the Center for Primary Care, all at Harvard Medical School.

Contributor Information

Sumit D. Agarwal, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, and a Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Michael L. Barnett, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, and a Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Jeff Souza, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston Massachusetts.

Bruce E. Landon, Departments of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Notes

- 1.Starfield B Is primary care essential? Lancet. 1994;344(8930):1129–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farber J, Siu A, Bloom P. How much time do physicians spend providing care outside of office visits? Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(10):693–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilchrist V, McCord G, Schrop SL, King BD, McCormick KF, Oprandi AM, et al. Physician activities during time out of the examination room. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):494–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottschalk A, Flocke SA. Time spent in face-to-face patient care and work outside the examination room. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):488–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, Prgomet M, Reynolds S, Goeders L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tai-Seale M, Olson CW, Li J, Chan AS, Morikawa C, Durbin M, et al. Electronic health record logs indicate that physicians split time evenly between seeing patients and desktop medicine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):655–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Burriss TC, Shanafelt TD. Providing primary care in the United States: the work no one sees. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1420–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong CS, Abrams MK, Ferris TG. Toward increased adoption of complex care management. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(6):491–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiest D, Yang Q, Wilson C, Dravid N. Outcomes of a citywide campaign to reduce Medicaid hospital readmissions with connection to primary care within 7 days of hospital discharge. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; revisions to payment policies under the Physician Fee Schedule, DME face-to-face encounters, elimination of the requirement for termination of non-random prepayment complex medical review and other revisions to Part B for CY 2013. Final rule with comment period. Fed Regist. 2012;77(222):68982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; revisions to payment policies under the Physician Fee Schedule, Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule and other revisions to Part B for CY 2014. Final rule with comment period. Fed Regist. 2013;78(237):74423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; revisions to payment policies under the Physician Fee Schedule, Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule, access to identifiable data for the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation Models and other revisions to Part B for CY 2015. Final rule with comment period. Fed Regist. 2014;79(219):67715–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bindman AB, Blum JD, Kronick R. Medicare’s transitional care payment—a step toward the medical home. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(8):692–4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medicare Learning Network. Transitional care management services [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2019. Jan [cited 2020 Mar 4]. (Fact Sheet). Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Transitional-Care-Management-Services-Fact-Sheet-ICN908628.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards ST, Landon BE. Medicare’s chronic care management payment—payment reform for primary care. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(22):2049–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medicare Learning Network. Chronic care management services [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2019. Jul [cited 2020 Mar 4]. (Booklet). Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/ChronicCareManagement.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basu S, Phillips RS, Bitton A, Song Z, Landon BE. Medicare chronic care management payments and financial returns to primary care practices: a modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):580–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bindman AB, Cox DF. Changes in health care costs and mortality associated with transitional care management services after a discharge among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(9):1165–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardner RL, Youssef R, Morphis B, DaCunha A, Pelland K, Cooper E. Use of chronic care management codes for Medicare beneficiaries: a missed opportunity? J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(11):1892–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwal SD, Barnett ML, Souza J, Landon BE. Adoption of Medicare’s transitional care management and chronic care management codes in primary care. JAMA. 2018;320(24):2596–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CMS.gov. Program guidance and specifications [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [last modified 2020 Feb 25; cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/program-guidance-and-specifications.html [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts ET, Mehrotra A, McWilliams JM. High-price and low-price physician practices do not differ significantly on care quality or efficiency. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5):855–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Early performance of accountable care organizations in Medicare. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(24):2357–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz AL, Zaslavsky AM, Landon BE, Chernew ME, McWilliams JM. Low-value service use in provider organizations. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(1):87–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganguli I, Souza J, McWilliams JM, Mehrotra A. Practices caring for the underserved are less likely to adopt Medicare’s annual wellness visit. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(2):283–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; c 2020. [cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/home [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heiser S, Conway PH, Rajkumar R. Primary care selection: a building block for value-based health care. JAMA. 2019. Sep 12. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burton R, Berenson RA, Zuckerman S. Medicare’s evolving approach to paying for primary care [Internet]. Washington (DC): Urban Institute; 2017. Dec [cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/95196/2001631_medicares_evolving_approach_to_paying_for_primary_care_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Landon BE. Tipping the scale—the norms hypothesis and primary care physician behavior. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):810–1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Malley AS, Sarwar R, Keith R, Balke P, Ma S, McCall N. Provider experiences with chronic care management (CCM) services and fees: a qualitative research study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(12):1294–300 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khullar D, Burke GC, Casalino LP. Can small physician practices survive?: sharing services as a path to viability. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1321–2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Squires D, Blumenthal D. Do small physician practices have a future? To the Point [blog on the Internet]. 2016. May 26 [cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2016/may/do-small-physician-practices-have-a-future

- 35.Liaw WR, Jetty A, Petterson SM, Peterson LE, Bazemore AW. Solo and small practices: a vital, diverse part of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(1):8–15 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine DM, Linder JA, Landon BE. Characteristics and disparities among primary care practices in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(4):481–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin S AAFP’s advocacy efforts paved way for new care management code. In the Trenches [blog on the Internet]. 2014. Dec 16 [cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/news/blogs/inthetrenches/entry/aafp_s_advocacy_efforts_paved.html [Google Scholar]

- 38.American College of Physicians. Top 10 things ACP advocacy and policy development did in 2013 to make your practice and professional life better [Internet]. Philadelphia (PA): ACP; [cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.acponline.org/advocacy/where-we-stand/other-issues/top-10-things-acp-advocacy-and-policy-development-did-in-2013to-make-your-practice-and-professional [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Medicare Learning Network. Chronic care management services changes for 2017 fact sheet [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2016. [cited 2020 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/MLN-Publications-Items/ICN909433.html [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.