Abstract

Background

WPV amongst healthcare workers has been reported as a public health challenge across the countries of the world, with more in the developing countries where condition of care and service is very poor.

Objectives

We aimed to systematically produce empirical evidence on the WPV against health care workers in Africa through the review of relevant literature.

Method

We sourced for evidence through the following databases: PubMed, Science direct and Scopus from 30th November to 31st December 2019 as well as the reference list of the studies included. A total of 22 peer reviewed articles were included in the review (8065 respondents). Quality appraisal of the included studies was assessed using critical appraisal tools for cross-sectional studies.

Result

Across the studies, diverse but high prevalence of WPV ranging from 9% to 100% was reported with the highest in South Africa (54%–100%) and Egypt (59.7%–86.1%). The common types were verbal, physical, sexual harassment and psychological violence. The correlates of WPV reported were gender, age, shift duty, emergency unit, psychiatric unit, nursing, marital status and others. Various impacts were reported including psychological impacts and desire to quit nursing. Patients and their relatives, the coworkers and supervisors were the mostly reported perpetrators of violence. Doctors were mostly implicated in the sexual violence against nurses. Policy on violence and management strategies were non-existent across the studies.

Conclusion

High prevalence of WPV against healthcare workers exists in Africa but there is still paucity of research on the subject matter. However, urgent measures like policy formulation and others must be taken to address the WPV as to avert the impact on the healthcare system.

Keywords: Health profession, Public health, Musculoskeletal system, Clinical psychology, Emergency medicine, Clinical research, Violence, Health, Healthcare workers

Health profession; Public health; Musculoskeletal system; Clinical psychology; Emergency medicine; Clinical research; Violence; Health; Healthcare workers.

1. Introduction

Workplace violence(WPV) amongst healthcare workers has been reported as a public health challenge across the countries of the world, with more in the developing countries where the condition of care and service is deplorable (Gates, 2004; Abdellah and Salama, 2017). In the health sector, violence has risen to an epidemic level, with nurses being the most common recipients (Berry, 2013; Nelson, 2014). More than 1/3 of the workplace violence in the world today occurs in the health sector (Boafo and Hancock, 2017). About 88% of healthcare workers in the developing countries reported violence of various types while at work with bullying, abuse and hitting with objects being the most common (Abodunrin et al., 2014). The above warranted the labeling of the healthcare sector as the most violent industry in the world by the Australian Institute of Criminology (Azodo et al., 2011).

WPV undermines the dignity of healthcare providers, safety of the workers, health and social well-being of the health professionals (Blanchar, 2011; Bowie et al., 2012; Magnavita and Heponiemi, 2012). In addition to the effects on the individual workers, workplace violence also has an impact on the organization through reduced output, absenteeism, payment of compensation, loss of experts, job dissatisfaction and workers turnover (Boafo and Hancock, 2017). WPV is reportedly the leading cause of death among workers in the world, with most cases among women (National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, 2018). Yearly, about 1.5 million workers died due to WPV (World Health Organization, 2014). WPV may be underreported in most developing countries, but the aftermath effect is obvious. Although it might be difficult to estimate the cost of violence, empirical evidence suggested that WPV account for 30% of the total cost of violence to the society (Gignon et al., 2014).

Globally, violence targeted at the healthcare workers are public health problem with gross variation in the healthcare system of the countries. The incidence of workplace violence is a serious problem to both developing and developed countries with more workers at risk in developing countries especially in Africa due to poorly developed health system (Seun-Fadipe et al., 2019). Africa as a continent has been reported to have the worst health indices in the world with a population of over 738 million people across the continent (World Health Organization, 2014). The health challenges in African countries have been acknowledged as the major setback to the actualization of millennium development goals (Salami et al., 2016). Human resources for health is a major challenge in most African countries and has been regarded as a contributory factor to the poor health indices in the continent (Salami et al., 2016). These human resources challenge has been linked to poor funding of the health care system, job dissatisfaction, WPV and lack of recruitment and retention of the health professionals(Salami et al., 2016). For instance, South Africa has 0.818 physicians per 1000 patients and 5.229 nurses and midwives per 1000 patients and reportedly the second highest after Libya (WHO, 2016). Nigeria has 15 nurses per 10,000 people, Physicians 3.83 per 10,000 people (World Health Organisation, 2019) yet nurses and other healthcare professionals emigrate the country in good numbers to western countries in search of greener pasture, healthy work environment, and positive career growth (Salami et al., 2016). An estimated 1/5 African healthcare workers migrate to the western world for employment purposes. About 10,684 African physicians left the continent in 2005, 13,584 in 2015 for greener pastures in the European countries (Poppe et al., 2014; Duvivier et al., 2017). Violence against healthcare professionals is a severe cankerworm that has eaten deep into the fabrics of the African health system. It has robbed the continent and other continents of the world numerous experts untimely due to injury, job dissatisfaction and death (Bowie et al., 2012; Magnavita and Heponiemi, 2012). According to World Health Organization, about 18 million healthcare workers are therefore required to achieve universal health care by 2030 in low and middle-income countries. These number of workers are non-existent. The few healthcare workers available face unhealthy situations ranging from violence, poor working condition and health funding (World Health Organisation, 2019). This further threatens the already weakened healthcare system, thereby promoting weaker health indices in Africa. Therefore, there is a need to protect the very few health professionals in the continent through all possible ways, one of which is fighting violence through policy advocacy.

Moreover, in order to revive the healthcare system and change the lousy health records in African countries, healthcare workforces must be increased, protected, retained, and satisfied. To achieve the above landmark in the health care system of Africa and other continents, violence against the healthcare workers must be seriously dealt with to a zero level. Initiation of policy advocacy and wide campaign against violence in healthcare system requires widely sourced evidence. Hence this systematic review on violence against health workers to provide wide-ranged and holistic empirical evidence for policy making.

2. Method

2.1. Aim

This review was conducted to assess the workplace violence against healthcare workers in Africa.

2.2. Design

The systematic review was conducted using the procedure outlined in preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2009).

2.3. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were included:

-

a)

Peer reviewed original research studies.

-

b)

Studies that focused on violence against healthcare workers.

-

c)

The study respondents were healthcare workers only.

-

d)

Studies published in English language.

-

e)

Studies that were done in African Countries between 2000 to 2019. All research articles that did not meet the above criteria were excluded.

2.4. Search method

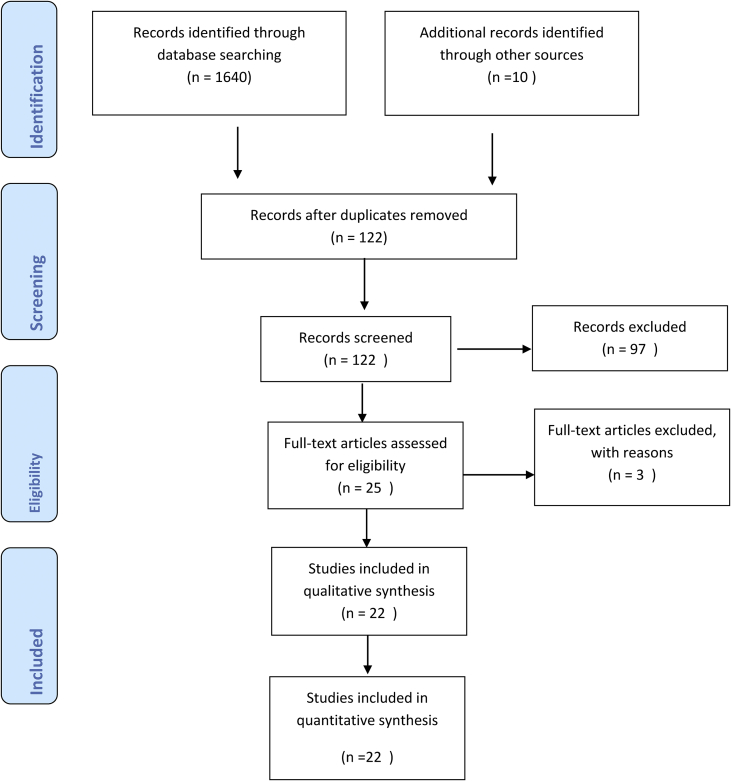

Electronic databases PubMed, Science direct and Scopus were searched. The following MESH words were used in the search: workplace bullying, physical OR verbal violence at work, sub-Saharan Africa, countries in Africa, workers. More peer reviewed research studies were identified using the references of the studies reviewed through Scopus and science direct. The search for all articles published on WPV was done between 30th November to December 31st 2019 for all the above databases. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Screening flowchart of how the articles were examined for inclusion.

2.5. Search outcome

A total of 1,650 articles related to the topic, workplace violence was found; after applying selection criteria and removal of duplications, a total of 122 peer reviewed articles were screened and 25 articles were assessed for eligibility (Figure 1: flowchart for the review). Out of the 25 articles assessed, 22 peer reviewed articles met the inclusion criteria. The study eligibility was ascertained independently by all authors through the review of the abstract and title for each peer reviewed article. Any difference in the eligibility assessment by the authors was resolved through group discussion. The reasons for exclusion were: a). incompleteness, b). not a research article, c). full article not accessible, d). sample size not indicated. e). target population, not healthcare workers.

2.6. Quality appraisal

The included studies were appraised using the critical appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies (AXIS) (Downes et al., 2016) and international standard for survey research studies. Criteria employed were a). random sampling; b). population based representative sample; c). The response rate to the survey instrument and d). If a standardized tool were used to assess the above subject matter. Each of the four elements was determined by two authors and confirmed by the other two. Any disagreement was resolved through group discussion by the authors. Each of the studies was scored 1 for yes or 0 for no or don't know answers respectively.

2.7. Data extraction

The data extraction form was developed and used for this study. Data regarding the reviewed study characteristics (Authors, year of publication, country of study, population studied, sample size, response rate and outcome, study method, prevalence of workplace violence among healthcare workers, types violence, impacts, policy on violence and the test for correlates) were determined independently by each author into data abstraction form designed for the review. Any notable differences were resolved by discussion.

3. Result

3.1. Characteristics of the reviewed studies

A total of 22 peer reviewed research studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review on workplace violence among healthcare workers in Africa (See Table 1). Nineteen out of the twenty-two studies employed a cross-sectional study design (Abdellah and Salama, 2017; Samir et al., 2012; Yenealem et al., 2019; Azodo et al., 2011; Abou-ElWafa et al., 2015; Abodunrin et al., 2014; Boafo, 2016; Olashore et al., 2018; Boafo and Hancock, 2017; Tiruneh et al., 2016; Seun-Fadipe et al., 2019; Sethole et al., 2019; Muzembo et al., 2015; Amkongo et al., 2019; Ogundipe et al., 2013; Boafo, 2018; Banda et al., 2016; Ukpong et al., 2011; Akanni et al., 2019). Two studies employed mixed method (Kennedy and Julie, 2013; Sisawo et al., 2017), while one used ethno-phenomenological design (Khalil, 2009). All other details are as shown in Table 1. Seven studies were excluded (El Ghaziri, Zhu, Lipscomb & Smith, 2014; Muldoon et al., 2017; Hinsenkamp, 2013; Madzhadzhi et al., 2017; Abbas et al., 2010; Ogbonnaya et al., 2012; Asefa et al., 2018) as shown on Table 2 below.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Authors | Country | Population/variables studied | N | Method | Response Rate | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdellah et al., (2017) | Egypt | Health workers/workplace violence against health workers | 142 | Cross-sectional | 94.4% |

Prevalence: overall 59.7% Prevalence by staff: nurses (65.7%), doctors (45.3%), housekeeper (71.4%). By Gender: (60.9%) female, male (39.1%), by age: <30 yrs (54.6%), >35yrs (37.8%), by experience:< or = 5yrs (67.6%) Types: verbal (58.2%), physical (15.7%), Correlates: age (p < 0.00) more in the young people. Profession (p < 0.046) more in nursing than others, duration of work (p < 0.007) more at night, marital status (p < 0.004) more in singles and separated than married. Perpetrators: patients and patients' relatives (90%), Staff& supervisors (25%) Policy on violence: non-existent Cause of Violence: Patient waiting time, unmet patients' needs. |

| Samir et al. (2012) | Egypt | Nurses/workplace violence | 500 | Cross- sectional | 83.2% |

Prevalence: 86.1% in 6 months with 53% having three or more cases. Majority were young age <30 years. Perpetrators: patients (14.7%) patients' relatives (38.5%), colleagues (54.5%). Types: 78.1% (psychological), 27.2% (physical), 4.6% (Sexual). Causes: Workload (40.5%), Carelessness & malpractice (35.8%) & understaffing. Policy: Non-existent but procedure for reporting of violence exist Impacts: 87.2% reported serious impact Correlates: age <30yrs, sex more in females than male, marital status. |

| Yenealem et al., (2019) | Ethiopia | Health workers/workplace violence against | 553 | Cross-sectional | 96.02% |

Prevalence: 58.2% in 12 months. Prevalence by gender: female (verbal = 57.1%), physical attack (59%), Sexual (100%) generally more in females than males. Types: verbal (53.1%), physical attack (22%) and sexual harassment (7.2%) Perpetrators: Patients, patients' relatives & colleagues at work Correlates: emergency department (OR = 3.99,CI = 95%), Shiftwork (OR = 1.98, CI = 95%), Work Experience(OR = 3.09), Being a Nurse (OR = 4.06, CI = 95%) Policy: Non-existence of policy and procedure for violence was reported. |

| Kennedy et al., (2013) | South Africa | Nurses/workplace violence against | 71 | Qualitative | 100% |

Prevalence: 100%of the respondents Types: physical, psychological, verbal Perpetrators: patients, patients' relatives Policy on violence: No existing policy on violence was reported Impacts: feeling of rejection and low morale among the respondents were reported. |

| Azodo et al. (2011) | Nigeria | Dentist/workplace violence against | 175 | Cross-sectional | 78.9% |

Prevalence: 39.1% Causes: Long waiting time (27.3%), cancellation of appointment (13.6%), treatment outcome (11.4%), alcohol intoxication (9.1%), psychosis (6.8%), Patients' bill (4.5%), & others (27.3%). Types: physical violence: Shouting (50%), Verbal threat (22.7%), swearing (2.3%), bullying & hitting (18.2%); sexual violence (6.8%). Perpetrators: Patients (54.5%), patients' relatives (18.2%), colleagues (22.7%). Impacts: impaired job performance (15.9%), Psychological trauma (13.6%), Absenteeism from work (9.1%). |

| Abou- Elwafa et al. (2015) | Egypt | Nurses in Emergency & non- emergency units/workplace violence against | 134and152 | Cross-sectional | 96.7% |

Prevalence: 54.7%. 6.8% non-emergency nurses reported fear for violence, 28.1%of emergency nurses reported exposure to types of violence while 46.9% non-emergency reported one type of violence. Types: Verbal and sexual violence were the common types reported. Correlates: Work shift (OR = 0.5), Emergency unit (OR = 2.0), Age (OR = 1.9), Specialty (P < 0.001), Work experience (p < 0.001). Perpetrators: Patients' relatives: physical (61.8%), Verbal (63.6%) and Bullying (50.5%). Staff members (36.4%). Impacts: 24.7% desired to change work environment. Policy: None reported existence of policy of violence. 71.8%, 77.1% & 73,7% never reported nor took any action against violence. |

| Abodunurin et al. (2014) | Nigeria | Health workers/workplace violence against | 242 | Cross-sectional | 96.8% |

Prevalence: Nurses (53.5%), Doctors (21.5%). Annually, 31doctors, 77 nurses, 36 others had violence. Perpetrators: patients (46.1%), patients' relatives (49.5%) Types: Verbal (64.6%), Physical (35.4%) Correlates: Age (young p < 0.0001), Work (p < 0.0045), Unit (p < 0.01). Policy: None reported |

| Boafo et al. (2016) | Ghana | Nurses/workplace violence against | 685 | Cross-sectional | 86.4% |

Prevalence: 64.2% Types: sexual (12.2%), verbal (52.7%) Perpetrators: Doctors (sexual 50%), patients' relatives. Policy: no policy but there is formal violence reporting procedure (72.9%). Correlates: Area of work (p < 0.01), Female (p < 0.01), age (p < 0.01), Marital status (p < 0.01). Impacts: verbal abuse was significantly correlated with quitting nursing (p < 0.05) |

| Khalil (2009) | South Africa | Nurses/workplace violence against | 471 | Ethno-phenomenology | 84% |

Prevalence: 54% Types: psychological (45%), Vertical (33%), covert (30%), horizontal violence (29%), overt violence (26%), physical violence (20%). Causes: lack of effective communication among nurses, lack respect among staff, lack of training on anger management among staff. |

| Olashore et al. (2018) | Botswana | Health Staff/workplace violence against |

210 | Cross-sectional | 85.2% |

Prevalence: 78.1%lifetime, 44.1% annual. Types: Hitting (41.1%), kicking (21.8%), pushing (20.2%) and shaking (12.1%) Perpetrators: patients. Areas: Higher incidence in acute wards (58.1%), other wards (22%). Causes: Provocation of patients (16.9%), attempt to calm patient down (33.3%) Impacts: 28% of the victims sustained injury, 18.5% of required medical attention, 72.6% required emotional support, 8.9%had other supports but 18.5%had no support. Higher level of job dissatisfaction was noted among the victims of violence than others. Correlates: Nursing (p < 0.01), work experience (P < 0.01). Policy: none reported to exist. |

| Boafo & Hancock2017 | Ghana | Nurses/workplace violence against | 592 | Cross-sectional | 100% |

Prevalence: 9% Female (79.2%) & male (20.8%) Types: physical violence (9%) Perpetrators: Patients, Patients' relatives (58.5%), Doctors, nurses Impacts: extreme concerns about violence were reported, 20.8% got injured, 17% received medical attention for the injury 19.9% intend to quit nursing (p < 0.001), loss of least 11 days working days. Policy: no existing policy on violence Correlates: type of hospital (p < 0.01). |

| Tiruneh et al. (2016) | Ethiopia | Nurses/workplace violence against | 386 | Cross-sectional | 90.2% |

Prevalence: 26.7% Types: physical (60.2%), Psychological (39.8%). Gender: male (59.2%), Female (40.8%). Impacts: dissatisfaction with job (38.83%), absent from work (36.9%) Perpetrators: patients and patients' relatives (16.1%), staff (27.18%). Correlates: age (younger than 30yrs AOR = 0.324), Small number of staff (AOR = 2.024), working in male ward (AOR = 7.918), History of violence(AOR = 0.270), Marital status single(AOR = 9.153), Widowed/separated (AOR = 7.914). Policy: non-existent, no actions usually taken by management following notice of violence. |

| Seun-Fadipe et al., 2019 | Nigeria | Health workers/workplace violence against | 380 | Cross-sectional | 95% |

Prevalence: 39% (12months) Types: physical (10.2%), verbal (31.9%), bullying (13.3%), sexual harassment (3.3%). Perpetrators: patients: (physical, 62.2%), verbal (26.1%), bullying (10.4%), sexual (16.7%); patients' relatives: physical (29.7%), verbal (50.4%), bullying (12.5%), sexual (16.7%); staff members: physical(5.4%), verbal(20.9%), bullying (70.9%), sexual (66.7%), supervisors: physical (2.7%), verbal (2.6%), bullying (6.3%) and sexual (0.0%). Impacts: 38.5% high risk for psychiatric morbidity linked to experience of violence (p = 0.037). Correlates: age (21–30yrs) (p < 0.001), gender (female) (p = 0.048), work setting (emergency & psychiatric units) (p < 0.001) were correlated with experience of violence at work. |

| Sethole et al. (2019) | South Africa | Radiographers/workplace violence against | 65 | Cross-sectional | 57% |

Prevalence & types: verbal abuse (73%), Emotional (46%), and physical (27%). Perpetrators: patients: verbal (8%), physical (15.8%) & non-verbal (4.1%). Patients' relatives: verbal (3.6%), physical (2.4%), non-verbal (2.8%). Nurses: verbal (7%), physical (0%), non-verbal (7.2%). Doctors: verbal (7.6%), physical (0%), non-verbal (4%). |

| Muzembo et al. (2015) | D. R. Congo | Health workers/workplace violence against | 2210 | Cross-sectional | 99% |

Prevalence: 80.1% (24.9% had once, 63.6% had two or more exposure). Types: verbal (57.4%), harassment (15.2%), physical (7.5%) & combined (11.9%). Perpetrators: patients (41%), patients' relatives (28–31%). Correlates: work experience (<5years) (p < 0.005), gender (p = 0.024) and marital status (p < 0.009). |

| Amkongo et al. (2019) | Namibia | Radiographers/workplace violence against | 15 | Cross-sectional | 86.7% |

Prevalence: 100% Types: verbal abuse (100%), verbal threat (84.6%), sexual harassment (84.6%), and physical assault (46.2%). Perpetrators: patients and patients' relatives. Impacts: anxiety (53.8%), feeling guilt or ashamed (7.7%), sad (38.5%), heartbroken (15.4%), afraid (38.5%) and others (15.4%). |

| Ogundipe et al. (2013). | Nigeria | Nurses/workplace violence against | 81 | Cross-sectional | 90% |

Prevalence: 88.6% witness and 65% victims, 15% threatened with weapon, 38% in the evening shifts. Perpetrators: patients' relatives. Impacts: declined productivity (24.5%), loss of confidence (15.2%), lack of job satisfaction (75.6%). Policy on Violence: non-existent with 83.6% reporting dissatisfaction with the way violence at work is being managed. |

| Sisawo et al. (2017) | Gambia | Nurses/workplace violence against | 219 | Mixed method | 98.2% |

Prevalence: 62.1% Types: physical (17.4%), verbal (60%), sexual harassment (10%). 22.5% of victims of physical violence had 2-4 times experience while 23% had been threatened with weapons. Perpetrators: patients: physical (33.6%), verbal (39.5%) and sexual (18.2%); patients' relatives: physical (54.2%), verbal (47.4%) & sexual (40.9%); staff: physical (5.34%), verbal (7.9%) and sexual (9.1%); Supervisors: physical (3.05%), verbal (2.6%) and sexual (4.5%). Correlates: Nurses Attendants (OR = 2.9, 95%, CI = 1.04–6.37); Area of work (OR = 2.9, 95%, CI = 1.16–7.35); General Nurses (OR = 4.1, 95%, CI = 1.09–2.59). Policy on violence: non-existent |

| Boafo (2018) | Ghana | Nurses/workplace violence against | 592 | Cross-sectional | 58% |

Prevalence: 73.9% (12 months). Types: Physical (9.0%), verbal (52.7%) and sexual (12.2%). Impact: the nurses were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied with their job due to violence. |

| Banda et al. (2016) | Malawi | Nurses/workplace violence against | 190 | Cross-sectional | 60% |

Prevalence:71% Types: physical assault (22%), sexual (16%), verbal abuse (95%), threatening behaviours (73%) and others (3%). Perpetrators: patients (71%), patients' relatives (47%), & colleagues (43%). Impacts: 80% nurses reported psychological trauma, loss of interest in nursing profession and low job performance. |

| Ukpong et al. (2011) | Nigeria | Mental health staff | 120 | Survey | 84.2% |

Prevalence: 49.5% with 12 months prevalence of 33.7% Profession: nurses (82.3%), doctors (17.6%) Types: push (44%), hit with object (28%), clothes torn (15%), attempted strangling (10%) and rape (2%). Impacts: 88% sustained injuries requiring medical attention. Perpetrators: patients Recommendation: formulation of policy on violence. |

| Akkani et al. (2019) | Nigeria | Mental health professionals | 124 | Cross sectional | 85.5% |

Prevalence: 62.1% career lifetime, 30.6% 12 months prevalence. Types: physical violence (hitting, kicking, striking with objects and attempted strangling). Common antecedent event: calming of aggressive patients, talking to patients, giving instructions to patients, and unprovoked. Impacts: 42.4% experience of posttraumatic stress disorders symptoms, 22.1% sustained injuries requiring hospital care. Correlates: age (p = 0.04), long years of practice (p = 0.01) and job dissatisfaction (0.05). Perpetrator: patients. |

Table 2.

Features of excluded studies.

| Author | Title | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| El Ghaziri et al., 2014 | Work schedule and clients characteristics associated with workplace violence among nurses and midwives in sub-Saharan Africa | Full article not accessible |

| Muldoon et al., 2017 | Policing the epidemics: high burden of workplace violence against sex workers | Not on health workers |

| Hinsenkamp (2013) | Violence against healthcare workers | Editorial article |

| Madzhadzhi et al. (2017) | Work place violence against nurses: Vhembe district hospital south Africa | Full article not accessible |

| Abbas et al. (2010) | Epidemiology of workplace violence against nursing staff in Egypt | Full article not accessible |

| Ogbonnaya et al. (2012) | Workplace violence against health workers in Nigeria tertiary Hospitals | Full article not accessible |

| Asefa et al. (2018) | Service providers experience of disrespectful and abusive behavior towards women during facility based child birth in Ethiopia | Not related |

3.2. Prevalence (6–12months) of workplace violence according to country

Across the literature, variable rates of workplace violence were reported across countries. Out of the fifty-four countries in the continent, Africa, ten countries had studies published on workplace violence against healthcare workers with only one national level study. In Egypt (59.7%–86.1%) experienced one form of or another violence (Abdellah and Salama, 2017; Abou- Elwafa et al., 2015). In Nigeria (31.9%–78%) had WPV and 88.6% witnessed violence (Abodunrin et al., 2014; Azodo et al., 2011; Seun-Fadipe et al., 2019; Ogundipe et al., 2013). In Ethiopia, the prevalence of WPV was 26.7%–58.2% (Yenealem et al., 2019; Tiruneh et al., 2016). In South Africa, WPV stood at 54%–100% (Kennedy and Julie, 2013; Khalil, 2009). Ghana had about 9%–73.9% cases of WPV (Boafo et al., 2016; Boafo, 2018). In Botswana, 78.1% lifetime and 44.1% annual prevalence of workplace violence was reported (Olashore et al., 2018). In Democratic Republic of Congo, 80.1% had WPV (Muzembo et al., 2015) while Namibian radiographers had 100% prevalence(Amkongo et al., 2019); Gambian nurses reported 62.1% prevalence of WPV (Sisawo et al., 2017); Malawian nurses reported 71% prevalence (Banda et al., 2016). See Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Country 6–12 month's prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers.

| Country | First Author | Year | Prevalence % | 95% CI (%) | Sample | Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | Abdellah. Samir Abou-Elwafa |

2017 2012 2015 |

59.7 86.1 61.5 |

48.7–70.7 83.2–89.0 68.5–54.5 |

142 500 286 |

85 430.5 175.9 |

| Nigeria | Abodurin Azodo Ogundipe Seun-Fadipe |

2014 2011 2013 2019 |

78 31.9 65 39.9 |

67.0–89.0 28.9–34.9 61.5–68.5 28.9–40.9 |

242 175 81 380 |

188.8 55.8 52.7 151.6 |

| Ethiopia | Yenealem Tiruneh |

2019 2016 |

58.2 26.7 |

40.6–75.8 24.6–28.8 |

553 386 |

321.8 103.1 |

| South Africa | Kennedy Khalil Sethole |

2013 2009 2019 |

100 54 57 |

99.8–99.9 43.3–64.7 44.3–69.7 |

71 471 65 |

71 254.3 37.1 |

| Ghana | Boafo Boafo Boafo |

2016 2017 2018 |

64.2 9 73.9 |

58.2–70.2 6.3–11.7 67.5–80.2 |

685 592 592 |

439.8 53.3 437.5 |

| Botswana | Olashore | 2018 | 78.1 | 69.1–87.1 | 210 | 164 |

| Congo | Muzembo | 2015 | 80.1 | 64.1–96.1 | 2210 | 1770.2 |

| Namibia | Amkongo | 2019 | 100 | 99.8–99.9 | 15 | 15 |

| Gambia | Sisawo | 2017 | 62.1 | 54.5–69.7% | 219 | 136.0 |

| Malawi | Banda | 2016 | 71 | 62.5–79.5 | 190 | 134.9 |

3.3. Prevalence according to the professions in the healthcare

Five groups of workers were found across literature including doctors, nurses, dentists, radiographers, and others (health assistants, admin staff). Among the doctors, studies revealed the prevalence of WPV to be 21.5%–45.3% (Abdellah and Salama, 2017; Abodurin et al., 2014).

The nurses the prevalence were 65.7% in Egypt (Abdellah and Salama, 2017), 86.1% among nurses in obstetrics and gynecology unit(Samir et al., 2012), 54.7% emergency nurses & 6.8% non-emergency nurses (Abou-Elwafa et al., 2015). In South Africa, 54% WPV among nurses in public hospitals (Khalil, 2009), 100% WPV among trauma and emergency nurses (Kennedy et al., 2013). Nigeria nurses reported 53.5%–65% WPV across studies (Abodurin et al., 2014; Ogundipe et al., 2013). About 62.1% prevalence among Gambian nurses(Sisawo et al., 2017); 71% prevalence among nurses in Malawi (Banda et al., 2016). Boafo (2018) revealed a 73.9% WPV among nurses in Ghana.

Among the other staff were reported varied cases of workplace violence. The prevalence varied from 25% to 71.4% among other staff (Abdellah and Salama, 2017; Abodurin et al., 2014), 31.9% among dental staff (Azodo et al., 2011). Studies reported 73%–100% WPV among radiographers (Sethole et al., 2019; Amkongo et al., 2019).

According to the work setting, across literature, emergency unit (59–100%), psychiatric setting (>78.1%), obstetrics and gynecology (86.1%) and outpatient units had the highest prevalence rate (Kennedy et al., 2013; Olashore et al., 2018; Samir et al., 2012). See Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Prevalence according to profession.

| Profession | Author | Year | Prevalence % | 95% CI | Sample | Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctors | Abodurin Abdellah |

2014 2017 |

21.5 45.3 |

17.8–25.2 39.4–51.2 |

54/242 56/142 |

31 24 |

| Nurses | Abdellah Samir Abou-Elwafa Khalil Kennedy Abodurin Ogundipe Sisawo Banda Boafo |

2017 2012 2015 2009 2013 2014 2013 2017 2016 2018 |

65.7 86.1 61.5 54 100 53.5 65 62.1 71 73.9 |

51.7–79.7 75.8–96.4 48.8–74.2 37.8–70.2 99.8–99.9 36.8–70.2 50.5–79.5 49.2–75.0 60.5–81.5 62.8–85.0 |

71/142 500 286 471 71 77/242 81 219 190 592 |

44 431 176 254 71 41 53 136 135 437 |

| Radiographers | Sethole Amkongo |

2019 2019 |

73 100 |

62.2–83.8 99.8–99.9 |

65 15 |

47 15 |

| Dentist | Azodo | 2011 | 31.9 | 26.4–37.4 | 175 | 56 |

| Others | Abdellah | 2017 | 71.4 | 60.7–81.7 | 10/242 | 7 |

| Units of Work | ||||||

| Emergency Unit | Ogundipe Abou-Elwafa Kennedy |

2013 2015 2013 |

65 54.7 100 |

50.5–79.5 38.2–71.2 99.8–99.9 |

81 134 71 |

53 73 71 |

| Psychiatric unit | Olashore | 2018 | 44.1 | 38.0–50.2 | 210 | 93 |

| Obstetrics & gynecology | Samir | 2012 | 86.1 | 75.8–96.4 | 500 | 431 |

| Clinic | Azodo | 2011 | 31.9 | 26.4–37.4 | 175 | 56 |

3.4. Prevalence according to gender

Only four studies specified the gender differences in the prevalence of workplace violence (Abdellah and Salama, 2017; Yenealem, 2019; Tiruneh et al., 2016; Seun-Fadipe et al., 2019). About 60.9% female and 20% male (Abdellah and Salama, 2017); 57.1% (verbal), physical attack(59%), sexual (100%) than the males were reported among female health workers in Ethiopia (Yenealem, 2019); 59.2% male and 40.8% females (Tiruneh et al., 2016).

3.5. Types of workplace violence among healthcare workers

Across the literature, the types of WPV ranged from physical, verbal, emotional or psychological, and sexual violence with variations in rates across studies (Sethole et al., 2019; Samir et al., 2012; Abdellah et al., 2017; Abou-Elwafa et al., 2015). Common physical forms of WPV were verbal (53.1%–73%) (Abdellah et al., 2017; Sethole et al., 2019; Abou-Elwafa et al., 2015); bullying (18.2%–50.8%), shouting (50%), threat (22.7%), swearing (2.3%), Vertical (33%), covert (30%), horizontal (29%) hitting (41.1%), kicking (21.8%), pushing (20.2%) and shaking (12.1%) (Khalil, 2009; Abou-Elwafa et al., 2015; Abdellah et al., 2017; Azodo et al., 2011; Olashore et al., 2018). Psychological violence ranged from 39.8% -46% (Khalil, 2009; Tiruneh et al., 2016; Sethole et al., 2019). Sexual harassment was reported to be 7.2% - 84. 6% among the healthcare workers (Samir et al., 2012; Yenealem et al., 2019; Azodo et al., 2011; Amkongo et al., 2019; Sisawo et al., 2017). See more details in Table 1.

3.6. Perpetrators of violence against healthcare workers

Across the studies reviewed, the perpetrators of violence against health workers were revealed to include patients, patients’ relatives, visitors, doctors, coworkers and supervisors in diverse rates across the studies. Patient relatives (18.2%–100%) (Abdellah et al., 2017; Kennedy et al., 2013; Abou-Elwafa et al., 2015; Azodo et al., 2011). The patients as perpetrators of WPV was reported at (46.1%–54.2%) (Abodurin et al., 2014; Banda et al., 2016; Azodo et al., 2011). coworkers and supervisors (22.3%–54.5%) (Azodo et al., 2011; Abdellah et al., 2017; Sisawo et al., 2017). Supervisors were responsible for (10.6%) WPV (Sisawo et al., 2017). See more details on Table 1.

3.7. Correlates of violence among healthcare workers

Across the studies reviewed, the correlates of workplace violence against healthcare workers were Age of the workers(21–30years) (Abdellah et al., 2017; Seun-Fadipe et al., 2019; Boafo et al., 2016; Abodurin et al., 2014; Tiruneh et al., 2016; Abou-Elwafa et al., 2015); profession (Abou-Elwafa et al., 2015; Abdellah et al., 2017; Olashore et al., 2018; Yenealem et al., 2019); emergency unit (Yenealem et al., 2019; Abou-Elwafa et al., 2015). Other commonly reported correlates of workplace violence were marital status (single or separated or widowed), shift work, work setting and work experience as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Correlates of violence against healthcare workers.

| Author | Year | Factors | P value/OR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abodurin | 2014 | Young age Work experience |

0.0001 0.045 |

| Muzembo | 2015 | Work Experience(<5years) Gender Marital status |

0.005 0.024 0.009 |

| Abou-Elwafa | 2015 | Work shift Emergency unit Younger age Specialty Work experience |

0.0(OR) 0.20(OR) 1.9(OR) 0.001 0.001 |

| Tiruneh | 2016 | Age(Young) Small number of staff on duty History Marital status (single) Working in male ward Widowed/separated |

0.324(OR) 2.024(OR) 0.270(OR) 9.153(OR) 7.918(OR) 7.914(OR) |

| Boafo | 2016 | Area of work Gender(Female) Age (21–30 years) Marital status (Single) |

0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 |

| Olashore | 2018 | Nursing Work experience(>10 years) |

0.01 0.01 |

| Yenealem | 2019 | Emergency Shift work Short work experience Nursing |

3.99(OR) 1.98(OR) 3.09(OR) 4.08(OR) |

| Fadipe | 2019 | Age(21–30yrs) Gender Work setting Previous training on violence Level of worry |

0.001 0.048 0.001 0.017 0.001 |

| Abdellah | 2017 | Age Profession Night work Marital Status |

0.00 0.046 0.007 0.004 |

3.8. Impacts of violence among healthcare workers

Across studies, different impacts of WPV violence was noted among health care workers. Most nurses in Ghana considered quitting their nursing jobs (Boafo and Hancock, 2017). Injuries of different degrees, hospitalization as a result of the injuries, psychological distress requiring supports were also noted among the workers as a result of WPV (Azodo et al., 2011; Olashore et al., 2018; Boafo and Hancock, 2017). Gross dissatisfaction with their job, absent from work for one-week and impaired job performance were also reported (Azodo et al., 2011; Tiruneh et al., 2016; Olashore et al., 2018). Desire to change work environment, a feeling of rejection and low morale among nurses with experience of violence (Abou-Elwafa et al., 2015; Kennedy et al., 2013). High risk of psychiatric morbidity, anxiety, feeling of guilt and ashamed, sad, heartbroken and fear related to WPV were reported across studies (Seun-Fadipe et al., 2019; Amkongo et al., 2019; Banda et al., 2016). Institutional decline in productivity, loss of confidence and low performance of job among the health care workers was reported across studies (Ogundipe et al., 2013; Banda et al., 2016).

3.9. Availability of policy on violence

Across studies reviewed no existing institutional policy on WPV management was reported (Samir et al., 2012; Kennedy et al., 2013; Abdellah et al., 2017; Abodurin et al., 2014; Azodo et al., 2011; Natan et al., 2011; Boafo et al., 2016; Tiruneh et al., 2016). In Ethiopia, 31.6% of the respondent healthcare workers reported non-existence of policy and reporting procedure on violence (Yenealem et al., 2019). The absence of a policy on violence in Gambia was repored (Sisawo et al., 2017), lack of proper reporting system for WPV. Lack of administrative action against the perpetrators of the violence even when notified was reported (Tiruneh et al., 2016; Abou-Elwafa et al., 2015). However, Boafo et al. (2016) found that 72.9% of respondents reported the existence of a procedure for reporting of violence, with 18% reporting that managers took action to investigate it further.

4. Discussion

This study is the first comprehensive literature review on workplace violence across African countries involving most widely sourced evidence across reliable databases and involving 20 peer reviewed articles in the continent. A global systematic review on the workplace violence against healthcare workers included only 11 peer reviewed articles in the continent yet Africa was the fourth with the highest cases of violence against health professionals(Liu et al., 2019). This review has significantly added new things to knowledge in that a broader and Africa focused studies (20) with in-depth findings have been explored to bring to limelight the true prevalence of the issue in the continent. Across the 54 countries in Africa, only ten countries have one or more research articles on workplace violence against healthcare workers. These countries include Nigeria, South Africa, Ghana, Gambia, Namibia, Egypt, Malawi, Ethiopia, Botswana, and Democratic Republic of Congo. Despite the lack of research studies, an overwhelmingly high rate of violence across the countries towards health workers has been reported ranging from 9% to 100% across studies and population. Of the ten countries with studies reviewed, only one country, Congo had one national level survey of the prevalence of WPV against healthcare workers (Muzembo et al., 2015).

Moreover, some of the other individual countries with studies at different setting had a low response rate and applied non-randomized sampling approach; hence the result is seen as having a high level of bias. Therefore, this poses a challenge in making a definite conclusion on the prevalence of WPV against healthcare workers in Africa. However, based on the individual countries, South African had the highest prevalence (54%–100%), Egypt had the second highest prevalence of WPV (59.7%–86.1%) across studies at CI 95%, followed by Nigeria (31.9%–78%) while the least was Ghana (9%–73.99%). Compared to other studies outside African countries, the rate WPV is similar to report of study on WPV against health workers in Pakistan, in which WPV stood at 73.1% with physical violence being the most common (Jafree, 2017). However, higher cases were noted in China were 29 cases of murder of health workers and124 cases of WPV of different degrees (Hesketh et al., 2012). According to global review on WPV against healthcare workers, the one year pooled rate reportedly varied across regions as follows Europe (26.38%), America (23.61%), Africa (20.71%), Eastern Mediterranean (17.09%), western pacific (14.53%) and South Asia (5.6%). The above differences were attributed to under reporting and continents’ specific peculiarities (Li et al., 2020). From the above, it would be just say that WPV is a global epidemic that has left no continent untouched hence requires continental policy adjustment to address.

This study systematically produced evidence on the prevalence of the workplace violence against health care workers such as doctors, nurses, dental staff, radiographers, mental health professionals and others across Africa. Across the above group of workers, nurses have received more attention in terms of research on the WPV (Khalil, 2009; Samir et al., 2012; Kennedy et al., 2013; Boafo et al., 2016, 2017; 2018; Tiruneh et al., 2016). Moreover, from the studies reviewed, nurses consistently recorded the highest number of cases of WPV followed by radiographers both in studies specifically on nurses as target population and those targeting the entire healthcare workers. This could be because nurses are usually the most available healthcare workforce and readily accessible to the patients and the visitors. They are also the first point of contact to the patients hence most likely to be the first victims of WPV before others. As reported by Olashore et al. (2018) being a nurse has been statistically linked to workplace violence. However, more definite and empirical stand regarding the above cannot be made owing to the lack of adequate research studies on the other group of workers.

With regards to the types of violence among the healthcare workers, this review has shown diverse types of WPV among healthcare workers to include physical, verbal, bullying, hitting, a threat with weapons, sexual harassment, psychological violence and shouting. Across all literature, verbal violence followed by physical, psychological and sexual harassment were the most frequently reported types of WPV. This is in agreement with the review by Liu et al. (2019) in which verbal abuse was reported as the most common form of violence against health workers. Threat with a weapon was reported among study on nurses which is very dangerous and need to be seriously addressed.

Regarding the correlates of WPV against healthcare workers, this review brought to open the numerous socio-demographic and environmental correlates of violence. Consistently reported by most of the studies as the correlates were age, work setting, year of experience, gender, profession, marital status, duration of work, number of staff on duty, work shift and others (Abodurin et al., 2014; Muzembo et al., 2015; Abou-Elwafa et al., 2015; Tiruneh et al., 2016; Boafo et al., 2016; Abdellah et al., 2017; Olashore et al., 2018; Yenealem et al., 2019; Seun-Fadipe et al., 2019). These factors are statistically associated with the incidences of violence among healthcare workers and calls for urgent attention across the continents as to avert the intending dangers on the healthcare system of the countries. Worthy of note is that WPV against healthcare workers are reported to vary across age and sex of the respondents (Abdellah et al., 2017; Samir et al., 2012; Abou- Elwafa et al., 2015; Seun-Fadipe et al., 2019). More cases of violence against the young than the elderly was reported (Abou- Elwafa et al., 2015; Tiruneh et al., 2016). The female healthcare workers had more cases of violence than the males while more case were noted among the single, divorced or separated than the married healthcare workers (Tiruneh et al., 2016; Seun-Fadipe et al., 2019). In terms of the units of work, emergency unit has been repeatedly linked to workplace violence across studies followed by psychiatric setting and outpatient units (Seun-Fadipe et al., 2019; Yenealem et al., 2019). This may be attributed to the urgency of need for attention and the frequently unorganized nature of emergency setting in most African settings. The psychiatric unit obviously houses people with altered psychological state hence could account for the high rate of violence. These correlates, therefore, need to be put into consideration in the staff allocation and reshuffling. For instance, adequate ratio of male to female combination may be utilized in those high-risk units for violence so that the males would provide form of psychological support to the females.

Also noted in the reviewed articles are the impacts of WPV on both the health care workers and the institutions. The impacts reported include physical, psychological, emotional, organizational and professional impacts of violence in the countries. Several cases of injuries and hospitalization of healthcare workers and gross job dissatisfaction among workers were recorded in a good number of the studies reviewed due to violence (Olashore et al., 2018). High risk for psychiatric morbidity Seun-Fadipe et al. (2019), feeling of rejection, low morale was also reported (Kennedy et al., 2012). Absenteeism from work due to violence and reduced efficiency at work was also reported across studies. Also worthy of note is the high rate at which healthcare workers are leaving the shore African countries which could be an indirect impact of the WPV and neglected healthcare system in the continent. Research evidence has associated WPV with intention to travel to other foreign countries among Ghanaian Healthcare workers with higher emigration intention among younger professionals and those with WPV experience (Boafo, 2016). There is grossly non-existence of policy on violence across the numerous health institutions in the countries within the continent, covered in this review. Therefore, this demands that key steps be taken to set up policy and strategies for violence management to save health workers and encourage them to put more effort to improve the condition.

4.1. Strength and limitation

This study has much strength. First, it is the first systematic review on the WPV against healthcare workers in Africa and has revealed that only ten countries in the continent have studies on the above subject matter and one country, Congo has nationwide based epidemiological survey of the workplace violence among health workers. Secondly, the study involved 22 peer reviewed articles published in reliable databases thereby provide wider view of the concept. Thirdly, this study also brought to limelight the fact that across the studies reviewed, no policy on violence was reported despite the high rate of violence against health workers. Therefore, this calls for urgent attention of the hospital administrators in various countries to save the already weak healthcare system and the policymakers to enact policy on violence prevention among health workers.

The major limitation of this review is limiting of the review to period of 2000–2019 which may have excluded other important articles on the subject matter. Secondly, the unavailability of qualitative research on the WPV may have not revealed the nature of the violence as it is in the view of the workers since quantitative studies does not frequently allow for detailed exploration of the situation.

5. Conclusion

This review has shown high rates of WPV against health workers across the countries in Africa from 2000 to 2019. The WPV were correlated with age, gender, profession and unit of work. Moreover, nurses reported the highest rate of violence across all professions. The common perpetrators of WPV as found in the literature were patients, their relatives, health care workers and the supervisors. WPV were reported to exert impacts on the workers and the institutions. Also found across the studies reviewed was the gross lack of policy on WPV. Urgent attention is by this study demanded of the policymakers to come up with a sound policy on violence prevention among healthcare workers in the continents as none has been reported to exist. However, more studies are needed to make a conclusive statement on the prevalence of WPV in Africa since only ten countries have research on the subject matter.

5.1. Implication to occupational health practice

-

✓

WPV is a serious threat to the occupational and environmental safety of the healthcare workers and therefore calls for the timely response of the occupational health experts in Africa and the world to advocate for change as to improve this ugly situation.

-

✓

Safety at workplaces is one of the targets of the World Health Organization, and this cannot be achieved without a sound policy at country levels and hospital level. Across the literature, there is no existing policy on violence management in the whole of Africa. Therefore, this calls on occupational health experts to rise and clamour for policy to meet the universal health for all goal of the world.

-

✓

Training on violence recognition and management by health professionals is seriously implicated.

5.2. Recommendation for further research

All African countries should sponsor a nationwide survey of WPV against healthcare workers to enable the conclusive stand to be reached on the state of the public health issue in the continent.

More researchers should be stimulated in the other parts of Africa on this subject matter and more appropriate sampling approach like random sampling should be employed to avoid bias which was seen in some of the studies reviewed.

5.3. In summary

-

❖

Healthcare workers in African countries encounter outrageous rate of violence from patients, patients' relatives and co-workers.

-

❖

Nurses were reported as having the highest cases of violence and three times more at risk than others.

-

❖

There is no existing policy on workplace violence management in health sectors across the continent.

-

❖

Healthcare workers are by this review charged to rise and advocate for policy making and changes in the health sectors to improve the working condition.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Abbas M.A., Fiala L.A., Abdel Rahman A.G., Fahim A.E. Epidemiology of workplace violence against nursing staff in Ismailia Governorate, Egypt. J. Egypt. Publ. Health Assoc. 2010;85(1–2):29–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdellah R.F., Salama K.M. Prevalence and risk factors of workplace violence against health care workers in emergency department in Ismailia, Egypt. Pan African Medical Journal. 2017;26:1–8. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.26.21.10837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abodunrin O.L., Adeoye A.O., Adeomi A.A., Akande A.A. Prevalence and forms of violence against health care professionals in a South-Western city, Nigeria. Sky Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences. 2014;2(8):67–72. http://www.skyjournals.org/SJMMS Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Abou-ElWafa H.S., El-Gilany A.H., Abd-El-Raouf S.E., Abd-Elmouty S.M., El-Sayed Hassan El-Sayed R. Workplace violence against emergency versus non-emergency nurses in mansoura university hospitals, Egypt. J. Interpers Violence. 2015;30(5):857–872. doi: 10.1177/0886260514536278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akanni O.O., Osundina A.F., Olotu S.O., Agbonile I.O., Otakpor A.N., Fela-thomas A.L. 2019. Prevalence , Factors , and Outcome of Physical Violence against Mental Health Professionals at a Nigerian Psychiatric Hospital; pp. 15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amkongo M., Hattingh C., Daniels E., Kalondo L., Karera A., Nabasenja C. Workplace violence involving radiographers at a state radiology department in Windhoek Namibia. South Afr. Radiogr. 2019;57(1):19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Asefa A., Bekele D., Morgan A., Kermode M. Service providers' experiences of disrespectful and abusive behavior towards women during facility based childbirth in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reprod. Health. 2018;15(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0449-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azodo C.C., Ezeja E.B., Ehikhamenor E.E. Occupational violence against dental professionals in Southern Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2011;11(3):486–492. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banda C.K., Mayers P., Duma S. Violence against nurses in the southern region of Malawi. Health SA Gesondheid. 2016;21:415–421. [Google Scholar]

- Berry P. Stressful incidents of physical violence against emergency nurses. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2013;18(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boafo I.M. The effects of workplace respect and violence on nurses’ job satisfaction in Ghana: a cross-sectional survey. Hum. Resour. Health. 2018;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0269-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boafo I.M., Hancock P. Workplace violence against nurses: a cross-sectional descriptive study of Ghanaian nurses. SAGE Open. 2017;7(1) [Google Scholar]

- Boafo I.M., Hancock P., Gringart E. Sources, incidence and effects of non-physical workplace violence against nurses in Ghana. Nursing Open. 2016;3(2):99–109. doi: 10.1002/nop2.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boafo I.M. Ghanaian nurses’ emigration intentions: the role of workplace violence. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2016;5:29–35. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214139116300427 [Google Scholar]

- Blanchar Y. Violence in the health care sector: a global issue. World Med. J. 2011;57(3):87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie V., Fisher B.S., Cooper C. Routledge; London, England: 2012. Workplace violence. [Google Scholar]

- Downes M.J., Brennan M.L., Williams H.C., Dean R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS) BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvivier R.J., Burch V.C., Boulet J.R. A comparison of physician emigration from Africa to the United States of America between 2005 and 2015. Hum. Resour. Health. 2017;15(41) doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0217-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Ghaziri M., Zhu S., Lipscomb J., Smith B.A. Work schedule and client characteristics associated with workplace violence experience among nurses and midwives in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care : J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(1 Suppl):S79–S89. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates D.M. The epidemic of violence against healthcare workers Editorial. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004;61:649–650. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.014548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gignon M., Verheye J.C., Manaouil C., Ammirati C., Turban-Castel E., Ganry O. Fighting violence against health workers: a way to improve quality of care. Workplace Health & Saf. 2014;62(6):220–222. doi: 10.1177/216507991406200601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh T., Wu D., Mao L., Ma N. Violence against doctors in China. BMJ. 2012;2012:345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5730. (sep07 1):e5730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinsenkamp M. Violence against healthcare workers. Int. Orthop. 2013;37:2321–2322. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2129-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafree S.R. Workplace violence against women nurses working in two public sector hospitals of Lahore, Pakistan. Nurs. Outlook. 2017;65(4):420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.01.008. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0029655417300441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M., Julie H. Nurses’ experiences and understanding of workplace violence in a trauma and emergency department in South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid. 2013;18(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil D. 2009. Khalil-2009-Nurs Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Gan Y., Jiang H., Li L., Dwyer R., Lu K. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019;76(12):927–937. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2019-105849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.L., Li R.Q., Qiu D., Xiao S.Y. Prevalence of workplace physical violence against health care professionals by patients and visitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(1):299. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madzhadzhi L.P., Akinsola H.A., Mabunda J., Oni H.T. Workplace violence against nurses: vhembe district hospitals, South Africa. Res. Theor. Nurs. Pract. 2017;(1):28–38. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.31.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnavita N., Heponiemi T. Violence towards health care workers in a public health care facility in Italy: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012;12(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff Jennifer, Altman Douglas. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. Br. Med. J. 2009;8:336–341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon Katherine A., Akello Monica, Godfrey Muzaaya, Simo Annick, Shoveller Jean, Shannon Kate. Policing the epidemic: high burden of workplace violence among female sex workers in conflict-affected northern Uganda. Global Publ. Health. 2017;12(1):84–97. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1091489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzembo B.A., Mbutshu L.H., Ngatu N.R., Malonga K.F., Eitoku M., Hirota R., Suganuma N. Workplace violence towards Congolese health care workers: a survey of 436 healthcare facilities in Katanga province Democratic Republic of Congo. J. Occup. Health. 2015;57(1):69–80. doi: 10.1539/joh.14-0111-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natan M. Ben, Hanukayev A., Fares S. Factors affecting Israeli nurses’ reports of violence perpetrated against them in the workplace: a test of the theory of planned behaviour. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2011;17(2):141–150. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health . 2018. Assaults Fourth Leading Cause of Workplace Deaths.https://www.nsc.org/work-safety/safety-topics/workplace-violence [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. Tackling violence against health-care workers. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1373–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60658-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbonnaya G.U., Ukegbu A.U., Aguwa E.N., Emma-Ukaegbu U. A study on workplace violence against health workers in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Nigerian J Med J National Ass Resident Doctors of Nigeria. 2012;21:174–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogundipe K.O., Etonyeaku A.C., Adigun I., Ojo E.O., Aladesanmi T., Taiwo J.O., Obimakinde O.S. Violence in the emergency department: a multicentre survey of nurses’ perceptions in Nigeria. Emerg. Med. J. 2013;30(9):758–762. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-201541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olashore A.A., Akanni O.O., Ogundipe R.M. Physical violence against health staff by mentally ill patients at a psychiatric hospital in Botswana. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018;18(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3187-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppe A., Jirovsky E., Blacklock C., Laxmikanth P., Moosa S., De Maeseneer J., Kutalek R., Peersman W. Why sub-Saharan African health workers migrate to European countries that do not actively recruit: a qualitative study post-migration. Glob. Health Action. 2014;7:24071. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.24071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salami B., Dada F.O., Adelakun F.E. Human resources for health challenges in Nigeria and nurse migration. Pol. Polit. Nurs. Pract. 2016;17(2):76–84. doi: 10.1177/1527154416656942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samir N., Mohamed R., Moustafa E., Abou Saif H. 198 Nurses’ attitudes and reactions to workplace violence in obstetrics and gynaecology departments in Cairo hospitals. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2012;18(3):198–204. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethole K.M., van Deventer S., Chikontwe E. Workplace abuse: a survey of radiographers in public hospitals in tshwane, South Africa. J. Radiol. Nurs. 2019;38(4):272–276. [Google Scholar]

- Seun-Fadipe C.T., Akinsulore A.A., Oginni O.A. Workplace violence and risk for psychiatric morbidity among health workers in a tertiary health care setting in Nigeria: prevalence and correlates. Psychiatr. Res. 2019 (June 2018);272:730–736. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisawo E.J., Ouédraogo S.Y.Y.A., Huang S.L. Workplace violence against nurses in the Gambia: mixed methods design. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017;17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2258-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiruneh B.T., Bifftu B.B., Tumebo A.A., Kelkay M.M., Anlay D.Z., Dachew B.A. Prevalence of workplace violence in Northwest Ethiopia: a multivariate analysis. BMC Nurs. 2016;15(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0162-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukpong D.I., Owoeye O., Udofia O., Abasiubong F. 2011. Violence against Mental Health Staff : a Survey in a Nigerian Psychiatric Hospital; pp. 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2014. Injuries and Violence - the Facts 2014.http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/en WHO Geneva, Swiss [20 p., Available at:] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . 2016. The health worker shortage in Africa: are enough physicians and nurses being trained.https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/87/3/08-051599/en/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . 2019. Health Workforce Requirement for Universal Coverage and Sustainable Development. [Google Scholar]

- Yenealem D.G., Woldegebriel M.K., Olana A.T., Mekonnen T.H. Violence at work: determinants & prevalence among health care workers, northwest Ethiopia: an institutional based cross sectional study. Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2019;31(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s40557-019-0288-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]