Abstract

Background

Palbociclib is highly active in oestrogen-receptor positive (ER+) metastatic breast cancer, but neutropenia is dose limiting. The goal of this study was to determine whether early neutropenia is associated with disease response to single-agent palbociclib.

Methods

Blood count and disease-response data were analysed from two Phase 2 clinical trials at different institutions using single-agent palbociclib: advanced solid tumours positive for retinoblastoma protein and advanced liposarcoma. The primary endpoint was PFS. The primary exposure variable was the nadir absolute neutrophil count (ANC) during the first two cycles of treatment.

Results

One hundred and ninety-six patients (61 breast, 135 non-breast) were evaluated between the two trials. Development of any grade neutropenia was significantly associated with longer median PFS in both the breast cancer (HR 0.29, 95% CI 0.11–0.74, p = 0.010) and non-breast cancer (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.38–0.85, p = 0.006) cohorts. Grade 3–4 neutropenia was significantly associated with prolonged PFS in the non-breast cohort (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.38–0.85, p = 0.006) but not in the breast cohort (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.51–1.47, p = 0.596). Multivariate analysis yielded similar results.

Conclusions

Treatment-related neutropenia in the first two cycles was significantly and independently associated with prolonged PFS, suggesting that neutropenia may be a useful pharmacodynamic marker to guide individualised palbociclib dosing.

Clinical trials registration information

Basket Trial: NCT01037790; Sarcoma Trial: NCT01209598.

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Predictive markers, Sarcoma, Cancer therapeutic resistance

Background

Palbociclib is an orally active cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor that has been practice-changing in the treatment of ER+ metastatic breast cancer.1 The PALOMA-2 and PALOMA-3 studies’ demonstration of improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared to endocrine therapy alone led to palbociclib being the first CDK 4/6 inhibitor to receive Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in combination with letrozole2 or fulvestrant3 in the metastatic, hormone-receptor positive (HR+) setting. Since then, two other CDK 4/6 inhibitors, ribociclib and abemaciclib, have also gained FDA approval for use in combination with endocrine therapy in advanced breast cancer based on improved PFS,4–6 with abemaciclib also being approved as a single agent based on the results of MONARCH 1.7 In addition, overall survival analyses of MONALEESA-7, MONALEESA-3, and MONARCH-2 suggest significantly improved overall survival with the addition of CDK 4/6 inhibition, with the results of PALOMA-3 suggesting a non-significant trend towards improved overall survival.8–11

Though generally well tolerated, the dose-limiting and most frequent adverse effect of these agents is neutropenia,2,3,12 resulting in frequent dose reductions and treatment interruptions.12,13 But despite grade 3–4 neutropenia rates of 62–66% seen in the PALOMA studies,2,3 infectious complications are rare.12 This is likely due to the mechanism that palbociclib exerts on haematopoietic cells. Palbociclib has been demonstrated in vitro to cause bone marrow suppression via cell-cycle arrest, which is reversible upon withdrawal of the medication.14 This is distinct from the marrow suppression caused by cytotoxic chemotherapy, which is the result of DNA damage and apoptosis.14 Importantly, palbociclib’s effect on retinoblastoma protein (Rb)-positive breast cancer cells is also mediated through cell-cycle arrest.15 We hypothesised that the degree of observed palbociclib-induced neutropenia that occurs with initiation of treatment is a reflection of the magnitude of effective systemic cell-cycle inhibition and would therefore predict drug activity and efficacy, regardless of tumour type. To test this hypothesis, we investigated whether neutropenia is associated with disease response in two Phase 2 clinical trials of single-agent palbociclib.

Methods

The methods for the two clinical trials analysed in this study have been previously reported.16–19 Both studies were open-label, non-randomised, Phase 2 clinical trials of single-agent palbociclib in patients with advanced Rb-positive cancers. Briefly, NCT01037790 (the “Basket Trial”) was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania and enrolled adults with advanced/metastatic malignancies that were refractory to standard therapy or had no available standard-of-care options, including breast cancer, Kras- or BRAF-mutated colorectal cancer, oesophageal cancer, gastric cancer, cisplatin-refractory germ cell tumours, or any tumour type (excluding small cell lung cancer and retinoblastoma) positive for CCND1/CCND2 amplification or CDK 4/6 mutations. The CDK 4/6 mutation and CCND1/CCND2 amplification cohorts for the Basket Trial were still open to enrolment at the time of this manuscript’s preparation, but all disease-specific cohorts had completed accrual. All enrolled patients at the time of original data abstraction in January 2016 were included in the analysis. NCT01209598 (the “Sarcoma Trial”) was conducted at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and enrolled patients with advanced well-differentiated/dedifferentiated liposarcoma.17 In both studies, patients were given single-agent palbociclib starting at 125 mg daily for 21 days, followed by 7 days off. Efficacy assessments were conducted every two cycles. Patients were maintained on study treatment until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or physician/patient decision to terminate participation.

Algorithms for dose modification and interruption were slightly different for each trial (Supplemental Fig. 1). In general, the dose modification scheme for the Basket Trial was designed to allow for more dose reductions based on varying levels of cytopenia than the Sarcoma Trial, which utilised treatment breaks rather than dose reductions upon development of neutropenia.

The primary endpoint considered for this analysis was PFS, which was defined as the time interval from Day 1/Cycle 1 of treatment initiation to radiographic progression, clinical progression (either before or after first planned scan), or death from any cause.20 The primary exposure variable characterising early neutropenia was the nadir absolute neutrophil count (ANC) during the first 2 cycles of treatment, which was defined as the lowest ANC at any point during the first 56 days after starting study drug. This exposure variable was chosen to limit immortal time bias and to capture the majority of neutropenic events prior to the first planned efficacy assessment. Nadir ANC was represented both as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable, according to grade of neutropenia (per Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3). During cycle one, blood counts were assessed at least once per week. Grade 1 neutropenia is defined in CTCAE v3 as an ANC below “the lower limit of normal” and 1.5 K/μL; the lower limit of normal for ANC used to define grade 1 neutropenia in this analysis was 1.8 K/μL.21 PFS curves were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier22 and compared using log-rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models23 were constructed manually using forward selection and confirmed using backward selection. Candidate variables potentially associated with PFS were Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, number of prior lines of systemic therapy (both chemotherapy and hormonal therapy), baseline ANC, race, sex, study site, body mass index (BMI), age, and chemotherapy as immediate prior line therapy. These variables were screened for inclusion in the model using a significance level of p < 0.2 in a univariate analysis and ultimately retained in the model using a criterion of p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the Stata 14 Statistics/Data Analysis software package (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 196 patients were enrolled between the two trials, with 137 patients enrolled in the Basket Trial and 59 patients enrolled in the Sarcoma Trial. Demographic characteristics stratified by breast cancer vs other tumour subtypes are shown in Table 1. Patients with breast cancer, comprising the largest disease cohort (N = 61), were all female and were more heavily pretreated compared to patients with other tumours. With respect to other demographic differences between the two trials, patients in the Basket Trial were more likely to have a higher baseline ECOG performance status, a higher number of prior lines of therapy, and were more likely to have chemotherapy as the immediate prior line of therapy (Table 2). A total of 186 patients, or 95% of the combined sample, discontinued the study for progressive disease (N = 185) or death from any cause (N = 1). Other reasons for discontinuing study treatment were patient decision (N = 4), toxicity (N = 3), and physician decision (N = 2). One patient remained on active treatment at the time of data cut-off in January 2016, at which time this patient had completed 55 cycles of therapy. The ten patients who did not experience disease progression during the study period were included in the survival analyses below and censored at withdrawal or last known follow-up.

Table 1.

Demographics by tumour type.

| Cancer type | Breast | Other |

|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 61 | 135 |

| Age in years, median (range) | 58 (34–88) | 55 (17–87) |

| Sex, N (%)a | ||

| Female | 61 (100) | 48 (36) |

| Male | 0 (0) | 87 (64) |

| Race, N (%) | ||

| White | 56 (92) | 113 (84) |

| Black | 3 (5) | 9 (7) |

| Asian/other | 2 (3) | 13 (10) |

| BMI, median (range)b | 25 (19–47) | 26 (16–48) |

| Baseline ECOG PS, N (%) | ||

| 0 | 40 (66) | 82 (61) |

| 1 | 21 (34) | 53 (39) |

| # Prior lines of therapy, N (%)a | ||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 24 (18) |

| 1 | 3 (5) | 49 (36) |

| 2 | 4 (7) | 23 (17) |

| ≥3 | 54 (88) | 39 (29) |

| Immediate prior line chemotherapy, N (%) | ||

| Yes | 35 (57) | 86 (64) |

| No | 26 (43) | 49 (36) |

| Baseline ANC (K/μL), median (range) | 4.0 (1.6–10.4) | 4.4 (1.5–31.9) |

aFisher’s Exact p < 0.05 (Wilcoxon rank-sum used for age, BMI, and baseline ANC).

bMissing BMI values for two patients in Basket Trial (due to unrecorded height).

Table 2.

Demographics by trial.

| Trial | Basket Trial | Sarcoma Trial |

|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 137 | 59 |

| Tumour type, N (%)a | ||

| Breast | 61 (45%) | 0 (0%) |

| Liposarcoma | 1 (<1%) | 59 (100%) |

| Germ cell | 30 (22%) | 0 (0%) |

| Colorectal | 22 (16%) | 0 (0%) |

| Oesophageal | 12 (9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Otherb | 11 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Age in years, median (range)a | 56 (17–88) | 62 (35–87) |

| Gender, N (%) | ||

| Female | 80 (58%) | 29 (49%) |

| Male | 57 (42%) | 30 (51%) |

| Race, N (%) | ||

| White | 122 (89%) | 47 (79%) |

| Black | 8 (6%) | 4 (7%) |

| Asian/other | 7 (5%) | 8 (14%) |

| BMI, median (range)c | 25.8 (16.0–47.1) | 27.2 (17.5–48.0) |

| Baseline ECOG PS, N (%)a | ||

| 0 | 71 (52%) | 51 (86%) |

| 1 | 66 (48%) | 8 (14%) |

| # Prior lines of therapy, N (%)a | ||

| 0 | 2 (1%) | 22 (37%) |

| 1 | 23 (17%) | 29 (49%) |

| 2 | 23 (17%) | 4 (7%) |

| ≥3 | 89 (65%) | 4 (7%) |

| Immediate prior line chemotherapy, N (%)a | ||

| Yes | 38 (28%) | 37 (63%) |

| No | 99 (72%) | 22 (37%) |

| Baseline ANC (K/μL), median (range) | 4.2 (1.5–31.9) | 4.1 (1.5–10.2) |

aFisher’s Exact p < 0.05 (Wilcoxon rank-sum used for age, BMI, and baseline ANC).

bOthers are diagnoses representing <5% of all patients (adrenal, gastric, glioblastoma, renal cell, and thymus cancers).

cMissing BMI values for two patients in Basket Trial (due to unrecorded height).

In the first two cycles, 155 patients (79%) experienced grade 1–4 neutropenia, with 41 patients (21%) not experiencing neutropenia. Of those not experiencing neutropenia, 5 patients had breast cancer (8% of all breast patients), and 36 had non-breast cancers (27% of all non-breast patients). Table 3 examines the clinical factors that were significantly associated with both any grade and grade 3–4 neutropenia within the first two cycles. Women, lower baseline ANC, and breast cancer diagnoses had a significantly increased incidence of any grade and grade 3–4 neutropenia. Patients with an ECOG performance status of 0 had a significantly increased incidence of any grade neutropenia, though not grade 3–4 neutropenia.

Table 3.

Risk of neutropenia in cycles 1–2 by clinical characteristics.

| Patient characteristics, N (%) | No neutropenia (n = 41) | Any grade neutropenia (n = 155) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p Value | Grade 0–2 NTP (n = 129) | Grade 3–4 NTP (n = 67) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||||||

| <50 | 13 (32%) | 47 (30%) | — | 0.9855 | 38 (29%) | 22 (33%) | — | 0.6806 |

| 50–69 | 21 (51%) | 81 (52%) | 1.07 (0.48–2.33) | 70 (54%) | 32 (48%) | 0.79 (0.40–1.55) | ||

| ≥70 | 7 (17%) | 27 (18%) | 1.07 (0.38–3.00) | 21 (16%) | 13 (19%) | 1.07 (0.45–2.55) | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 26 (63%) | 61 (39%) | — | 0.0059 | 68 (53%) | 19 (28%) | — | 0.001 |

| Female | 15 (37%) | 94 (61%) | 2.67 (1.48–3.71) | 61 (47%) | 48 (72%) | 2.82 (1.49–5.31) | ||

| Race | ||||||||

| Black | 1 (2%) | 11 (7%) | — | 0.4263 | 7 (5%) | 5 (7%) | — | 0.2264 |

| White | 36 (88%) | 133 (86%) | 0.33 (0.04–2.69) | 115 (90%) | 54 (81%) | 0.66 (0.20–2.1) | ||

| Other | 4 (10%) | 11 (7%) | 0.25 (0.02–2.61) | 7 (5%) | 8 (12%) | 1.60 (0.35–7.40) | ||

| BMIa | ||||||||

| <Median | 16 (40%) | 80 (52%) | — | 0.1768 | 59 (46%) | 37 (56%) | — | 0.188 |

| ≥Median | 24 (60%) | 74 (48%) | 0.62 (0.30–1.25) | 69 (54%) | 29 (44%) | 0.67 (0.37–1.22) | ||

| ECOG performance status | ||||||||

| 0 | 18 (44%) | 104 (67%) | — | 0.0072 | 76 (59%) | 46 (67%) | — | 0.1791 |

| 1 | 23 (56%) | 51 (33%) | 0.38 (0.19–0.77) | 53 (41%) | 21 (31%) | 0.65 (0.35–1.22) | ||

| # Prior lines of therapy | ||||||||

| 0 | 6 (15%) | 18 (12%) | — | 0.5859 | 17 (13%) | 7 (11%) | — | 0.4799 |

| 1 | 9 (22%) | 43 (28%) | 1.59 (0.49–5.13) | 37 (29%) | 15 (22%) | 0.98 (0.34–2.86) | ||

| 2 | 8 (19%) | 19 (12%) | 0.79 (0.22–2.73) | 19 (15%) | 8 (12%) | 1.02 (0.31–3.42) | ||

| ≥3 | 18 (44%) | 75 (48%) | 1.39 (0.48–4.00) | 56 (43%) | 37 (55%) | 1.60 (0.61–4.25) | ||

| Immediate prior line chemotherapy | ||||||||

| No | 30 (73%) | 91 (59%) | — | 0.0843 | 79 (61%) | 42 (63%) | — | 0.8432 |

| Yes | 11 (27%) | 64 (41%) | 1.91 (0.90–4.11) | 50 (39%) | 25 (37%) | 0.94 (0.51–1.73) | ||

| Baseline ANC | ||||||||

| <Median | 4 (10%) | 90 (58%) | — | <0.0001 | 44 (34%) | 50 (75%) | — | <0.0001 |

| ≥Median | 37 (90%) | 65 (42%) | 0.08 (0.03–0.23) | 85 (66%) | 17 (25%) | 0.18 (0.09–0.34) | ||

| Trial | ||||||||

| Basket Trial | 32 (78%) | 105 (68%) | — | 0.1906 | 87 (67%) | 50 (75%) | — | 0.2942 |

| Sarcoma Trial | 9 (22%) | 50 (32%) | 1.69 (0.75–3.82) | 42 (33%) | 17 (25%) | 0.70 (0.36–1.37) | ||

| Breast cancer | ||||||||

| No | 36 (88%) | 99 (64%) | — | 0.0017 | 99 (77%) | 36 (53%) | — | 0.0011 |

| Yes | 5 (12%) | 56 (36%) | 4.07 (1.51–10.97) | 30 (23%) | 31 (46%) | 2.84 (1.51–5.34) | ||

ANC absolute neutrophil count, BMI body mass index, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, NTP neutropenia.

aHeight missing from two patients (one patient with no NTP, one with grade 3 NTP).

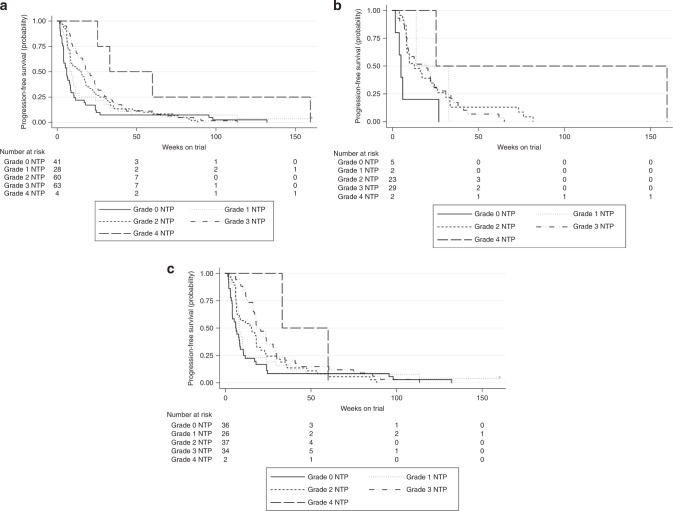

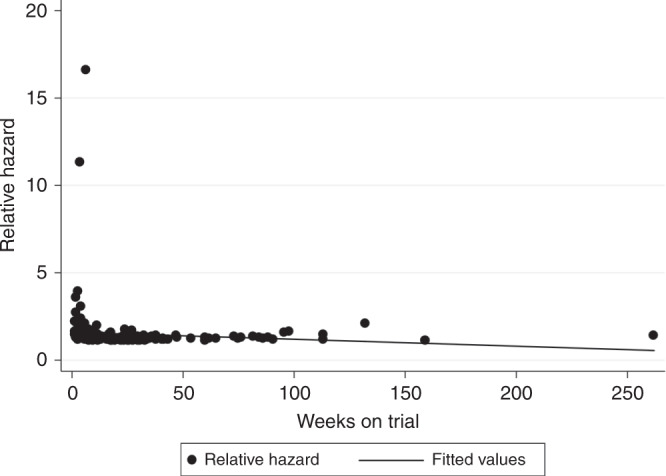

Figure 1 displays the relationship between each patient’s nadir ANC in the first two cycles (as a continuous variable) and PFS weeks as a predicted relative hazard based on a univariate Cox regression model. The Spearman’s rho of −0.41 (p < 0.001) indicates that decreasing values for nadir ANC were significantly associated with prolonged PFS weeks (hazard ratio (HR) 1.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.13–1.32, p < 0.001). In the breast cancer subgroup, nadir ANC in cycle 1–2 (as a continuous variable) was also associated with PFS (HR 1.73, 95% CI 1.02–2.97, p = 0.042). The nadir ANC was also analysed as a categorical variable according to the maximum grade of neutropenia in the first two cycles. For all patients, increasing grade of neutropenia was associated with significantly prolonged median PFS (log-rank p = 0.002), with corresponding HR and median PFS weeks for each grade of neutropenia listed below in Fig. 2a. The relationship between increasing grade of neutropenia and prolonged PFS remained significant after analysing patients with breast (Fig. 2b, log-rank p = 0.028) and non-breast (Fig. 2c, log-rank p = 0.013) tumours separately.

Fig. 1. Nadir ANC in cycles 1–2 vs PFS weeks—Cox predicted relative hazard values.

Spearman’s rho = −0.4073 (p < 0.001). HR 1.22 (95% CI 1.13–1.32).

Fig. 2. Kaplan-Meier survival by cycle 1–2 maximum grade neutropenia.

a All patients. Grade 0: (reference); median PFS 6.0 weeks. Grade 1: HR 0.65 (0.40–1.07), p = 0.092; median PFS 8.1 weeks. Grade 2: HR 0.60 (0.40–0.90), p = 0.014; median PFS 15.6 weeks. Grade 3: HR 0.49 (0.33–0.74), p = 0.001; median PFS 19.4 weeks. Grade 4: HR 0.19 (0.06–0.62), p = 0.006; median PFS 60.0 weeks. Overall log-rank p = 0.002. b Breast patients. Grade 0: (reference); median PFS 5.0 weeks. Grade 1: HR 0.30 (0.05–1.56), p = 0.152; median PFS 13.9 weeks. Grade 2: HR 0.27 (0.10–0.75), p = 0.012; median PFS 16.3 weeks. Grade 3: HR 0.33 (0.12–0.87), p = 0.024; median PFS 19.4 weeks. Grade 4: HR 0.05 (0.01–0.52), p = 0.011; median PFS 25.4 weeks. Overall log-rank p = 0.028. c Non-breast patients. Grade 0: (reference); median PFS 6.0 weeks. Grade 1: HR 0.73 (0.43–1.23), p = 0.232; median PFS 8.0 weeks. Grade 2: HR 0.66 (0.41–1.06), p = 0.083; median PFS 15.6 weeks. Grade 3: HR 0.46 (0.28–0.75), p = 0.002; median PFS 18.0 weeks. Grade 4: HR 0.20 (0.02–1.17), p = 0.071; median PFS 60.0 weeks. Overall log-rank p = 0.013.

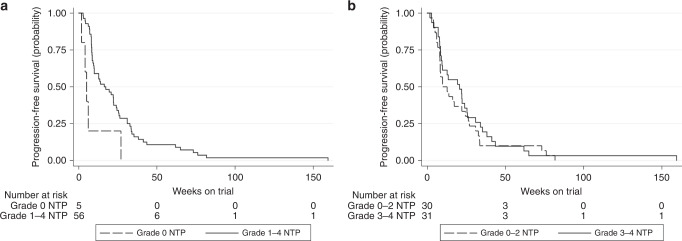

Examining the patients with breast cancer in closer detail, those who experienced grade 1–4 neutropenia in the first two cycles had significantly prolonged PFS compared to those who experienced grade 0 neutropenia, with median PFS of 17.3 and 5 weeks, respectively (HR 0.29, 95% CI 0.11–0.74, p = 0.010, Fig. 3a). Nine patients who had HER2-positive disease also received concurrent trastuzumab. Excluding these patients from the above analysis resulted in similar findings (HR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12–0.82, p = 0.018). There was no difference in median PFS for breast cancer patients who experienced grade 3–4 neutropenia compared to those with grade 0–2 neutropenia (20.7 vs 12.7 weeks, respectively, HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.51–1.47, p = 0.596, Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. Kaplan-Meier survival by cycle 1–2 any grade or grade 3–4 neutropenia (breast patients).

a Any grade neutropenia. Grade 0: (reference); median PFS 5.0 weeks. Grade 1–4: HR 0.29 (95% CI 0.11–0.74), p = 0.010; median PFS 17.3 weeks. b Grade 3–4 neutropenia. Grade 0–2: (reference); median PFS 12.7 weeks. Grade 3–4: HR 0.87 (95% CI 0.51–1.47), p = 0.596; median PFS 20.7 weeks.

Non-breast cancer patients who experienced any grade neutropenia also had significantly prolonged PFS compared to those with grade 0 neutropenia (median PFS 16.1 vs 6 weeks, respectively, HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.38–0.85, p = 0.006). In addition, grade 3–4 neutropenia was significantly associated with prolonged PFS compared to grade 0–2 neutropenia in the non-breast group (median PFS 20.6 vs 9.5 weeks, respectively, HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.38–0.85, p = 0.006).

Multivariate Cox regression models were constructed for all patients, as well as both the breast and non-breast cohorts, and are shown in Table 4. The screening univariate Cox analysis is also provided in Supplementary Table 1. Using both forward and backward variable selection, any grade of neutropenia within the first two cycles, age (above the median value), and immediate prior line consisting of chemotherapy remained significantly associated with PFS in the breast group. In the non-breast group as well as the overall population, any grade of neutropenia within the first two cycles, ECOG performance status, and number of prior lines of therapy were significantly associated with PFS. Adjusting for these variables, any grade of neutropenia remained significantly and independently associated with prolonged PFS (overall: HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.34–0.70, p < 0.001; breast: HR 0.19, 95% CI 0.07–0.52, p = 0.001; non-breast: 0.56 95% CI 0.37–0.83, p = 0.004).

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis.

| Covariate | HR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| All patients | ||

| Any NTP in C1–2 | ||

| No | ||

| Yes | 0.49 (0.34–0.70) | <0.001 |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | ||

| 1 | 1.51 (1.12–2.04) | 0.007 |

| # Prior lines of therapy | ||

| 1–2 | ||

| 3+ | 1.39 (1.02–1.87) | 0.033 |

| Breast patients | ||

| Any NTP in C1–2 | ||

| No | ||

| Yes | 0.19 (0.07–0.52) | 0.001 |

| Age | ||

| <Median | ||

| ≥Median | 0.50 (0.29–0.89) | 0.017 |

| Immediate prior line chemo | ||

| No | ||

| Yes | 1.76 (1.02–3.03) | 0.042 |

| Non-breast patients | ||

| Any NTP in C1–2 | ||

| No | ||

| Yes | 0.56 (0.37–0.83) | 0.004 |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | ||

| 1 | 1.68 (1.15–2.43) | 0.006 |

| # Prior lines of therapy | ||

| 1–2 | ||

| 3+ | 1.81 (1.22–2.70) | 0.003 |

Discussion

Neutropenia is the most important adverse effect of palbociclib because of both its high frequency and impact on drug dosing. We found that neutropenia following single-agent palbociclib was strongly associated with higher PFS across a variety of diseases and was independent of other clinical factors. The strong association of early neutropenia with PFS suggests that the neutrophil count in cycles 1 and 2 may predict likelihood of disease response. Because patients remained on trial until clinical or radiographic progression, these findings also support improved duration of response.

Our findings confirm and expand on analyses of the PALOMA-3 trial in breast cancer in which PFS was also examined in relation to neutrophil count and dose-reduction status.24 In PALOMA-3, grade 3 or 4 neutropenia was not associated with prolonged PFS in the experimental group, a finding confirmed in the present analysis. However, our data suggest that early grade 0 neutropenia may predict reduced response to palbociclib. While a “dose effect” association of decreasing nadir ANC and increasing median PFS was observed (Figs. 1 and 2a, b), grades 2 and 3 neutropenia represented the majority of maximum cycle 1–2 grade neutropenia in the breast cohort. The predominance of grades 2 and 3 neutropenia is the likely explanation for no observed difference in PFS between grade 3–4 and grade 0–2 neutropenia in the breast cohort. This may also be the reason why the data from PALOMA-3 do not suggest an association between neutropenia and PFS, as only grade 3–4 vs grade 0–2 neutropenia was analysed in this trial.24 The improved PFS with grade 3–4 neutropenia in the non-breast cohort was likely driven by the significantly increased proportion of patients with grade 0 neutropenia compared to the breast cohort.

It is important to recognise that while patients experiencing neutropenia within the first two cycles had longer PFS, it is possible that patients who did not experience neutropenia might still have received some benefit from the drug. Both studies were single-arm trials, therefore there is no control arm against which the PFS for the grade 0 neutropenia group can be compared. The basis for favourable outcomes in patients with some degree of toxicity is potentially suggested by previous studies of neutropenia in Phase 2 and Phase 2 data sets. Sun et al.25 used a population pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic model to study the relationship between drug levels and ANC by combining data from three different clinical trials that studied palbociclib either alone or in combination with letrozole. They found that higher levels of palbociclib exposure were associated with lower ANC values and that this neutropenia was rapidly reversible and noncumulative. In addition, there is further preclinical evidence from Hu et al.14 of a dose–response relationship between increasing palbociclib dose and increasing levels of neutropenia. Furthermore, Im et al. performed an analysis of the PALOMA-2 data in Asian women and found both higher rates of neutropenia as well as higher palbociclib trough concentrations compared to non-Asians.26 Conversely, Iwata et al.27 reported safety and efficacy data from PALOMA-3 comparing rates of neutropenia, relative dose intensity, and palbociclib trough concentrations between Asian and non-Asian patients. While patients in the Asian arm had higher rates of neutropenia and required more dose reductions for neutropenia than non-Asian patients, the palbociclib trough concentrations were not significantly different between the two groups.

The fact that our study utilised data from a variety of malignancies and included two partner studies that handled dose modification in different ways are particular strengths, suggesting that this is not a disease-specific effect but rather a pharmacodynamic one. The overall sample size, as well as relatively higher numbers of patients with breast cancer and liposarcoma, provides adequate power to detect the HRs in both the overall group and specific disease subsets, as described above. In addition, the multivariate models constructed strongly suggest that this association is independent of other clinical factors. However, patients with other malignancies are represented in smaller numbers, and careful consideration should be taken when applying findings to these patients. Also, it is important to acknowledge that many patients with early clinical progression will contribute shorter PFS times, therefore these results should be interpreted cautiously, and further confirmation of these findings is needed. Finally, the lack of pharmacokinetic data is a limitation of this study, preventing any investigation of the association between circulating drug levels and serum neutropenia, and should be incorporated into future studies of this relationship.

Conclusions

Patients who experienced palbociclib-related neutropenia in the first two cycles of treatment had significantly improved PFS compared to patients who did not experience neutropenia. This effect was seen across multiple tumour types, including breast cancer, and remained significant in a multivariate analysis. Even though patients experiencing grade 0 neutropenia exhibited reduced PFS relative to those experiencing any grade neutropenia, it is still possible that they received some benefit from the drug. These findings, validating preclinical data and the clinical findings in PALOMA-3, have the potential to impact clinical decision-making and future palbociclib development. Future research is needed to better understand the underlying mechanism of this effect and, if confirmed, whether it can be exploited to optimise therapeutic effect by matching an individual’s palbociclib dose to a target ANC. A prospective trial comparing flat dosing to dosing tailored to a target ANC is warranted to determine whether neutropenia could be clinically utilised as a predictive biomarker and identify patients who may be under-dosed and not achieving effective cell-cycle inhibition with the FDA-approved dose.

Supplementary information

Supplemental Table 1 (A-C) and Supplemental Figure 1 (A-B)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Pfizer, who provided the study drug, palbociclib, in the two trials described in this paper. At the time the trials opened, palbociclib was a novel agent and not available commercially.

Author contributions

N.P.M.: study concept and design, quality control of data, data analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation, editing, and review. M.A.D.: study concept and design, quality control of data, manuscript editing, and review. A.S.C., D.V., and G.K.S.: study concept and design, manuscript review. A.B.T.: study concept, data analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis, manuscript editing, and review. M.H.O.: study concept, manuscript review. C.C., M.G., K.G., and K.Z.: data acquisition, manuscript review. P.J.O. and A.D.: study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript editing, manuscript review.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Each of the clinical trials in this study, including the informed consent forms authorising patient agreement and participation in each study, were approved by their respective institutional review boards of the University of Pennsylvania and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data availability

The data analysed in this study are securely managed by the study team and not available as part of a public database but can be made available in a deidentified fashion if requested by the editorial board.

Competing interests

N.P.M. received research funding from Novartis and Daiichi Sankyo; advisory board honorarium from Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo, and Genomic Health; consulting honorarium from Daiichi Sankyo and Novartis; travel accommodation from TRIO, Daiichi Sankyo, and Roche, as well as speaking honorarium from Novartis. M.A.D. has received research funding from Pfizer, Eli-Lilly, and AADi, along with providing consultation and advisory to Pfizer and Celgene. A.S.C. has received research funding from Novartis. D.V. received research funding from Merck, Astellas, and Genetech, along with providing consultation and sitting on the advisory board to Merck. M.H.O. received research support from Eli Lilly, BMS, and Celldex and received Honoraria from Astra Zeneca, along with providing consultation to Karyopharm and Exelixis. P.J.O. has received research funding from Amgen, Bayer, BBI Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Five Prime Therapeutics, Forty Seven, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Mirati Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, and Pharmacyclics, along with providing consultation and advising to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Five Prime Therapeutics, Forty Seven, and Genentech. A.D. has received research funding from Novartis, Pfizer, Genentech, Calithera, and Menarini, along with providing consultation to Contact Therapeutics, Pfizer, Novartis, and Calithera. All remaining authors have declared no conflict of interests.

Funding information

This work was supported by the NIH [grant number T32-CA-09679 to N.P.M.] and the NCI at NIH [grant numbers P01CA047179 and P50CA140146 to G.K.S; grant number P30CA008748 to M.A.D.]. The authors acknowledge the additional following funds, companies, and grants that contributed to this research: the Penn–Pfizer Alliance (to A.D. and P.J.O.) and Pfizer (research support to M.A.D.).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41416-020-0967-7.

References

- 1.Salkeni MA, Hall SJ. Metastatic breast cancer: endocrine therapy landscape reshaped. Avicenna J. Med. 2017;7:144–152. doi: 10.4103/ajm.AJM_20_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finn RS, Martin M, Rugo HS, Jones S, Im S-A, Gelmon K, et al. Palbociclib and letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:1925–1936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner NC, Ro J, André F, Loi S, Verma S, Iwata H, et al. Palbociclib in hormone-receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:209–219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA, Yap Y-S, Sonke GS, Paluch-Shimon S, et al. Ribociclib as first-line therapy for HR-positive, advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:1738–1748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George W, Sledge J, Toi M, Neven P, Sohn J, Inoue K, Pivot X, et al. MONARCH 2: abemaciclib in combination with fulvestrant in women with HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer who had progressed while receiving endocrine therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:2875–2884. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slamon DJ, Neven P, Chia S, Fasching PA, Laurentiis MD, Im S-A, et al. Phase III randomized study of ribociclib and fulvestrant in hormone receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced breast cancer: MONALEESA-3. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:2465–2472. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.9909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickler MN, Tolaney SM, Rugo HS, Cortés J, Diéras V, Patt D, et al. MONARCH 1, a phase II study of abemaciclib, a CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitor, as a single agent, in patients with refractory HR+/HER2− metastatic breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23:5218. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Im SA, Lu YS, Bardia A, Harbeck N, Colleoni M, Franke F, et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus endocrine therapy in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381:307–316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slamon, D. J., Neven, P., Chia, S., Fasching, P. A., De Laurentiis, M., Im, S. A. et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 514–524 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sledge, G. W., Toi, M., Neven, P., Sohn, J., Inoue, K., Pivot, X. et al. The effect of abemaciclib plus fulvestrant on overall survival in hormone receptor-positive, ERBB2-negative breast cancer that progressed on endocrine therapy-MONARCH 2: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 6, 116–124 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Turner NC, Slamon DJ, Ro J, Bondarenko I, Im SA, Masuda N, et al. Overall survival with palbociclib and fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:1926–1936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1810527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa R, Costa RB, Talamantes SM, Helenowski I, Peterson J, Kaplan J, et al. Meta-analysis of selected toxicity endpoints of CDK4/6 inhibitors: palbociclib and ribociclib. Breast. 2017;35:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colleoni M, Sun Z, Price KN, Karlsson P, Forbes JF, Thürlimann B, et al. Annual hazard rates of recurrence for breast cancer during 24 years of follow-up: results from the International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I to V. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:927–935. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu W, Sung T, Jessen BA, Thibault S, Finkelstein MB, Khan NK, et al. Mechanistic Investigation of bone marrow suppression associated with palbociclib and its differentiation from cytotoxic chemotherapies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22:2000–2008. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark AS, Karasic TB, DeMichele A, et al. Palbociclib (pd0332991)—a selective and potent cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor: a review of pharmacodynamics and clinical development. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:253–260. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flaherty KT, LoRusso PM, DeMichele A, Abramson VG, Courtney R, Randolph SS, et al. Phase I, dose-escalation trial of the oral cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor PD 0332991, administered using a 21-day schedule in patients with advanced cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:568. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickson MA, Schwartz GK, Keohan M, et al. Progression-free survival among patients with well-differentiated or dedifferentiated liposarcoma treated with cdk4 inhibitor palbociclib: a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:937–940. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaughn DJ, Hwang W-T, Lal P, Rosen MA, Gallagher M, O’Dwyer PJ. Phase 2 trial of the cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in patients with retinoblastoma protein-expressing germ cell tumors. Cancer. 2015;121:1463–1468. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeMichele A, Clark AS, Tan KS, Heitjan DF, Gramlich K, Gallagher M, et al. CDK 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib (PD0332991) in Rb+ advanced breast cancer: phase II activity, safety, and predictive biomarker assessment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:995–1001. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McPherson, R. & Pincus, M. Table A5-9 Hematology. Henry’s Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods 23rd edn (Elsevier, St. Louis, 2017).

- 22.Dudley WN, Wickham R, Coombs N. An introduction to survival statistics: Kaplan-Meier analysis. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2016;7:91–100. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2016.7.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sedgwick, P. Cox proportional hazards regression. BMJ347, f4919 (2013).

- 24.Verma S, Bartlett CH, Schnell P, DeMichele AM, Loi S, Ro J, et al. Palbociclib in combination with fulvestrant in women with hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative advanced metastatic breast cancer: detailed safety analysis from a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III study (PALOMA-3) Oncologist. 2016;21:1165–1175. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun W, O’Dwyer PJ, Finn RS, Ruiz-Garcia A, Shapiro GI, Schwartz GK, et al. Characterization of neutropenia in advanced cancer patients following palbociclib treatment using a population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling and simulation approach. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017;57:1159–1173. doi: 10.1002/jcph.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Im SA, Mukai H, Park IH, Masuda N, Shimizu C, Kim SB, et al. Palbociclib plus letrozole as first-line therapy in postmenopausal asian women with metastatic breast cancer: results from the phase III, randomized PALOMA-2 Study. J. Glob. Oncol. 2019;5:1–19. doi: 10.1200/JGO.19.11000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwata H, Im S-A, Masuda N, Im Y-H, Inoue K, Rai Y, et al. PALOMA-3: phase III trial of fulvestrant with or without palbociclib in premenopausal and postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative metastatic breast cancer that progressed on prior endocrine therapy—safety and efficacy in Asian patients. J. Glob. Oncol. 2017;3:289–303. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.008318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1 (A-C) and Supplemental Figure 1 (A-B)

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed in this study are securely managed by the study team and not available as part of a public database but can be made available in a deidentified fashion if requested by the editorial board.