Abstract

Potassium channels are widely expressed in most types of cells in living organisms and regulate the functions of a variety of organs, including kidneys, neurons, cardiovascular organs, and pancreas among others. However, the functional roles of potassium channels in the reproductive system is less understood. This mini-review provides information about the localization and functions of potassium channels in the female reproductive system. Five types of potassium channels, which include inward-rectifying (Kir), voltage-gated (Kv), calcium-activated (KCa), 2-pore domain (K2P), and rapidly-gating sodium-activated (Slo) potassium channels are expressed in the hypothalamus, ovaries, and uterus. Their functions include the regulation of hormone release and feedback by Kir6.1 and Kir6.2, which are expressed in the luteal granulosa cells and gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons respectively, and regulate the functioning of the hypothalamus–pituitary–ovarian axis and the production of progesterone. Both channels are regulated by subtypes of the sulfonylurea receptor (SUR), Kir6.1/SUR2B and Kir6.2/SUR1. Kv and Slo2.1 affect the transition from uterine quiescence in late pregnancy to the state of strong myometrial contractions in labor. Intermediate- and small-conductance KCa modulate the vasodilatation of the placental chorionic plate resistance arteries via the secretion of nitric oxide and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Treatment with specific channel activators and inhibitors provides information relevant for clinical use that could help alter the functions of the female reproductive system.

Keywords: Potassium channels, Gonadal steroid hormones, Ovary, Uterus, Placenta

Introduction

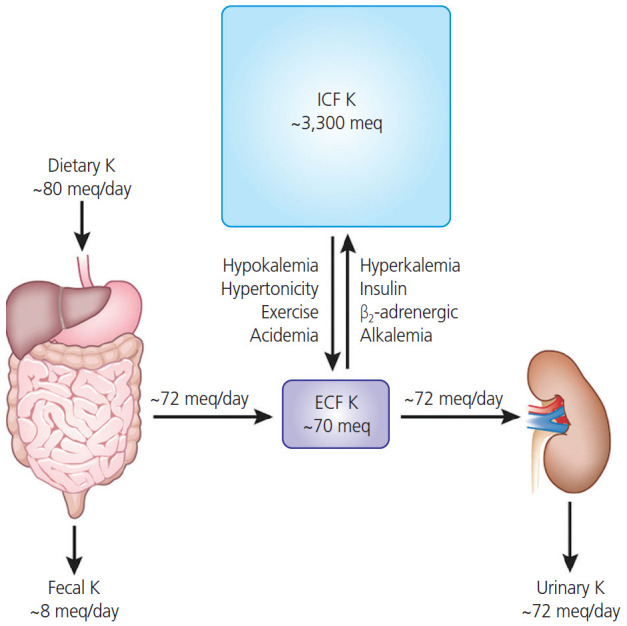

The maintenance of extracellular potassium concentration within a narrow range is vital for numerous cellular functions, particularly for maintaining the electrical excitability of heart and muscle cells [1]. The plasma potassium concentration is usually maintained within narrow limits (typically, 3.5 to 5.0 mmol/L) through multiple mechanisms [2]. The functions of potassium channels are critical for urinary excretion of potassium ions. The long-term maintenance of potassium homeostasis is achieved by alterations in the renal excretion of potassium in response to variations in intake [3]. Fig. 1 shows that 90% of potassium that is derived from dietary intake is excreted by the kidney (up to 80 mEq/day intake vs. 72 mEq/day in the urine) to maintain normal potassium concentrations in the extracellular fluid (up to 70 mEq/day in adults) [1]. In Korea, the recommended dietary intake of potassium in individuals above 12 yr is 3,500 mg; the World Health Organization recommends a similar intake. Intracellular fluids contain approximately 98%, or rather 3,600 mmol (140 g) of the potassium ions in the body, while the other 2% present in the extracellular compartment is usually maintained within a narrow range (3.8–4.5 mEq/L) in serum [4,5]. Since our ancestors could easily obtain potassium-rich fruit and vegetables, the recommended content of 15 g/day was easily exceeded. There are several types of highly evolved potassium channels in the kidney [4]. The balance in potassium ion concentration across the cell membrane is essential for maintaining the resting membrane potential and signal conduction in nerve and muscle cells via the repolarization of action potential. Potassium channels are pore-forming transmembrane (TM) proteins and are classified into 4 major families: calcium-activated, inward-rectifier, voltage-gated, and 2-pore-domain potassium channels [6]. Certain researchers classify ATP-sensitive potassium channels as a fifth family independent of inward-rectifier potassium channels [7,8].

Fig. 1.

The amounts of potassium of daily dietary intake, distribution in intracellular fluid (ICF) and extracelluler fluid (ECF), and daily fecal and urinary excretion. Most dietary potassium is excreted by the kidney (up to 80 mEq/day intake vs. up to 72 mEq/day in the urine) to maintain normal potassium concentrations. Approximately 98% of potassium is present in the ICF (up to 3,300 mEq), while the other 2% present in the extracellular compartment (up to 70 mEq) which is usually maintained within a narrow range (3.8–4.5 mEq/L) in serum. Hypokalemia has many causes including: excessive potassium loss due to diarrhea, excessive sweating from exercise, abuse of alcohol, some diuretics, or laxatives. In contrast, hyperkalemia can be occurred due to acute kidney failure, chronic kidney disease, medication such as angiotensin II receptor blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or beta blockers, and dehydration or excessive potassium supplements.

Potassium channels consist of 2 subunits: primary α-subunits and auxiliary β-subunits. The pore-forming subunits have 2–6 TM domains and the sensitivity of the channels to calcium, ATP, voltage, and oxygen among others is conferred by the α-subunits. Voltage-gated potassium channels (KV channels) comprise of 6 TM domains, calcium-activated potassium channels (BKCa channels) have 6 or 7 TM segments, and inward-rectifying potassium channels have 2 TM segments as α-subunits [9]. In contrast, β-subunits regulate the activities of the channels; e.g., SUR-subunits in Kir6. X channels are involved in the regulation of insulin secretion. The various types of potassium channels are involved in controlling different phases of the action potential—while the majority of KV channels allow K+ ion efflux when the membrane is depolarized, Kir channels conduct K+ ions during hyperpolarization [10]. Table 1 outlines the details of calcium-activated (KCa) and inward-rectifying (Kir) KATP potassium channel families and Table 2 outlines the details of voltage-gated (Kv) and the 2-pore domain (K2P) potassium channel families. The well-known activators and inhibitors are also listed in the tables [11].

Table 1.

Summary of calcium activated (KCa) and inwardly-rectifying (Kir) KATP potassium channel families, activators and inhibitors

| Kca channels (8 isoforms & 5 subfamilies): BKCa, SK, IK |

Kir channels (15 isoforms & 7 subfamiles): KATP |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HGCN | IUPHAR | HGCN | IUPHAR |

| KCNMA1 | KCa1.1 | KCNJ1 | Kir1.1 |

| KCNN1-3 | KCa2.1–KCa2.3 | KCNJ2, J12, J4 & J14 | Kir2.1–Kir2.4 |

| KCNN4 | KCa3.1 | KCNJ3, J6, J9 & J5 | Kir3.1–Kir3.4 |

| KCNT1 & T2 | KCa4.1 & KCa4.2 | KCNJ10 & J15 | Kir4.1 & Kir4.2 |

| KCNU1 | KCa4.1 | KCNJ16 | Kir5.1 |

| KCNJ8 & J11 | Kir6.1 & Kir6.2 | ||

| KCNJ13 | Kir7.1 | ||

| Channel opener for Kca: NS1619 | Channel opener for Kir: Pinacidil, cromakalim, aprikalim (Kir6.x) | ||

| Channel blocker for Kca: Iberiotoxin, apamin, charybdotoxin | Channel blocker for Kir: Tetraethylammonium (TEA), 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), glibenclamide, tolbutamide | ||

The table is adopted from reference [11].

Table 2.

Summary of voltage gated (Kv) and the 2-pore domain (K2P) potassium channel families, activators and inhibitors

| KV channels (42 isoforms & 12 subfamilies) |

K2P channels (15 isoforms) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HGCN | IUPHAR | HGCN | IUPHAR |

| KCNA1–A0 | KV1.1–KV 1,10 | KCNK1 | K2P1.1 |

| KCNB1–B2 | KV2.1 & KV2.2 | KCNK2 | K2P2.1 |

| KCNC1–C4 | KV3.1–KV3.4 | KCNK3 | K2P3.1 |

| KCND1–D3 | KV4.1–KV4.3 | KCNK4 | K2P4.1 |

| KCNF1 | KV5.1 | KCNK5 | K2P5.1 |

| KCNG1–G4 | KV6.1–KV6.4 | KCNK6 | K2P6.1 |

| KCNQ1–Q5 | KV7.1–KV7.5 | KCNK7 | K2P7.1 |

| KCNV1& V2 | KV8.1 & KV8.2 | KCNK9 | K2P9.1 |

| KCNS1–3 | KV9.1–KV9.3 | KCNK10 | K2P10.1 |

| KCNH1 & H5 | KV10.1 & KV10.2 | KCNK12 | K2P12.1 |

| KCNH2, H6, and H7 | KV11.1–KV11.3 | KCNK13 | K2P13.1 |

| KCNH8, H3, and H4 | KV12.1–KV12.3 | KCNK15 | K2P15.1 |

| KCNK16 | K2P16.1 | ||

| KCNK17 | K2P17.1 | ||

| KCNK18 | K2P18.1 | ||

| Channel opener for KV: Correolide (KV1.5), Stromatoxin-1 (KV2.1), Flupirtine (KV7) PD118057, NS1643 (KCNH) | Channel opener for K2P: Arachidonic acid (TREK-1), volatile anesthetics (isoflurane) | ||

| Channel blocker for KV: 4-AP (KV), phrixotoxin-2 (KV4), Linopirdine (KV7), dofetilide, E4031, Be-KM1 (KCNH) | Channel blocker for K2P: Fluphenazine, L-methionine (TREK-1), SSRI, antipsychotics (haloperidol) | ||

The table is adopted from reference [11].

Notably, the potassium channels participate not only in the regulation of membrane potential but also in various cellular functions, including volume regulation, cell proliferation, cell migration, angiogenesis, and apoptosis [6]. This mini-review focuses on the multiple potassium channels associated with the cells of the female reproductive system, and discusses their action on the hypothalamus–pituitary–ovarian axis for the regulation of progesterone production from granulosa cells (GCs) in the ovary, myometrial relaxation in the uterus during pregnancy, the induction of uterine contractions in labor, and the modulation of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) production in the syncytiotrophoblast in the placenta [5,12,13].

Expression and roles of potassium channels in the ovary

The ovary facilitates the production and maintenance of oocytes and supports the secretion of female sex hormones, which is essential for the regulation of puberty and pregnancy and determines the reproductive lifespan [14]. The ovary is protected by 3 outer layers: germinal epithelium, connective tissue capsule, and tunica albuginea. The outer cortex and inner medulla are located inside the ovary. Ovarian follicles at various stages of maturation are present in the ovarian cortex, and oocytes or female germ cells are present in each follicle. From puberty, the development and degeneration of follicles from the primordial follicle stage to the corpus luteum is influenced by follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). The follicle primarily consists of oocytes and granulosa; progesterone is produced from luteinized GCs and by the corpus luteum in the ovary in the non-pregnant state. Progesterone concentrations peak 7–8 days after ovulation and rapidly reduce along with the degeneration of the corpus luteum. Progesterone inhibits the synthesis of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) to prevent the maturation of other follicles and prepares the body for a possible pregnancy. If fertilization does not occur, the corpus luteum degenerates and the follicle is excreted via menstrual bleeding [15]. The ovulation of mature follicles in the ovary is induced by a preovulatory surge in the levels of luteinizing hormone (LH), and subsequently, estrogen is secreted by the GCs of the ovarian follicles and the corpus luteum. The concentrations of LH and FSH secreted by the pituitary gland and estradiol secreted by the follicles peak during ovulation in the menstrual cycle [15].

In the ovary, the KATP potassium channels and the BKCa channels participate in the regulation of progesterone secretion, and the intracellular potassium and calcium concentrations affect the secretion of progesterone [16]. BKCa channels induce the repolarization of the plasma membrane and play an important role in the cellular response depending on the Ca2+ concentration. The acetylcholinergic agonist carbachol and oxytocin increase intracellular Ca2+ concentration in cultured human granulosa-lutein cells. The intracellular calcium signal affects progesterone release in lutein-GCs via BKCa [16-18]. hCG stimulates the release of oxytocin, which, along with acetylcholine, acts as an ovarian signaling molecule. Kunz et al. [16] reported that the activation of the BKCa channels in GCs is generally necessary for endocrine function, and BKCa channel blockade using iberiotoxin causes a marked reduction in hCG-stimulated progesterone secretion. Notably, hCG does not play a role in BKCa activation; acetylcholine and oxytocin, which are local neuroendocrine substances released by GCs, participate in this process by causing a transient increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentrations [19]. In summary, the activities of the BKCa channel in GCs is mediated by intra-ovarian signaling involving neurotransmitters (e.g., acetylcholine) and peptide hormones (e.g., oxytocin). Traut et al. [20] reported the expression (in vitro and ex vivo) of several classes of KCa channels (IK, SK, and BK) in human GCs, which participate in gonadotropin-stimulated sex steroid hormone production.

In addition to the intracellular calcium levels, the intracellular potassium levels also affect progesterone secretion from luteal cells [21]. Typical KATP channels consist of an inwardrectifier K+ ionophore (Kir6.x) and a sulfonylurea receptor (SURx); there are 2 Kir6.x isoforms (Kir6.1 and 6.2), and 3 SUR isoforms (SUR1, SUR2A, and SUR2B). Although 6 combinations of Kir6.x and SURx can be formed, only 4 types of KATP channel have been reported: those found in pancreas β-cells (SUR1/Kir6.2), cardiac and skeletal muscles (SUR2A/Kir6.2), smooth muscles (SUR2B/Kir6.2), and vascular smooth muscles (SUR2B/Kir6.1) [22]. Of these, only Kir6.1/SUR2B is detected in the corpus luteum of the ovary and myometrium of the rat, while the placenta expresses Kir6.1 with SUR1 and SUR2B [23]. These ovarian KATP channels are involved in the production of progesterone in luteinized GCs [5]. The KATP inhibitor glibenclamide triggers the depolarization of the plasma membrane induced by the blockage of the KATP channels; it reduces hCG-induced progesterone production in ovarian GCs [5]. However, the exact underlying mechanism remains unclear. Other ion channels, including Kv4.2 (KCND2) and L-type and T-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and a KATP-independent progesterone production process are also involved in hormone regulation [24,25]. Therefore, progesterone production is likely regulated via complex physiological processes.

Expression and role of KATP channels in pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the hypothalamus

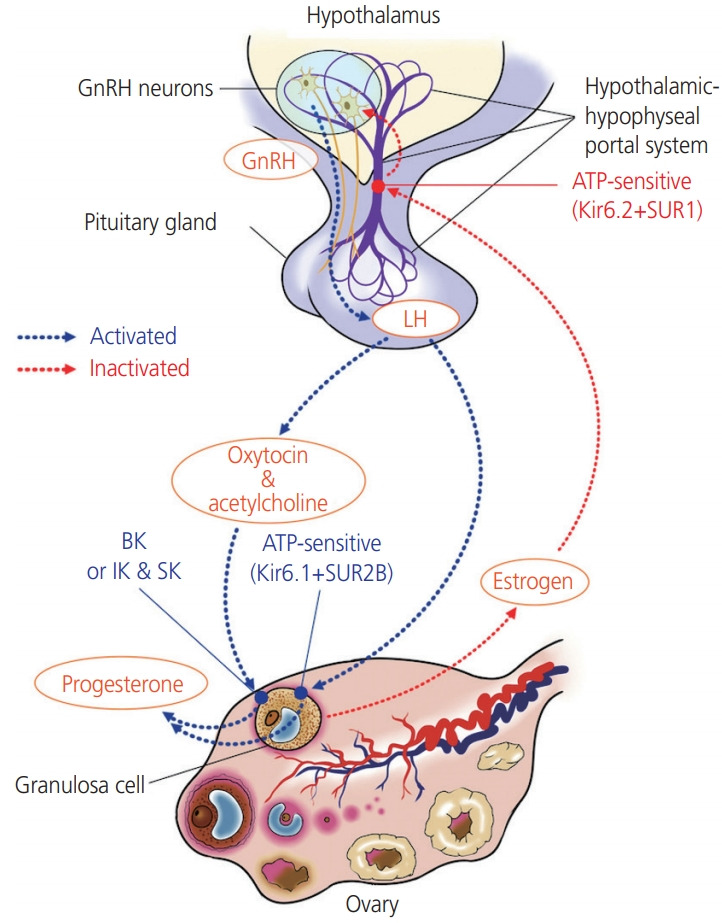

Progesterone secretion is mediated by the Kir6.1/SUR2B KATP channel subtype in the ovary. KATP channels are also involved in modulating the excitability of GnRH neurons in an estrogen-sensitive manner (Fig. 2). The pancreatic β-cell subtype of channels containing Kir6.2/SUR1 subunits is the KATP channel subtype that is predominantly expressed in GnRH neurons in the hypothalamus [26]. The KATP channel Kir6.2/SUR1 modulates the pulsatile release of GnRH, and negative feedback from ovarian steroids affects the release of hormones in the hypothalamus and pituitary by altering the activity of the KATP channels. The Kir6.2 mRNA levels in the preoptic area responds to treatment with both E2 and progesterone. The KATP channel blocker tolbutamide enhances the frequency of pulsatile GnRH release under steroid treatment [27]. In contrast, the KATP channel activator diazoxide prevents the increase in the frequency of the LH pulse. As the Kir6.2/SUR1 subtype has a sulfonylurea receptor, this channel is activated by diazoxide, while it is blocked by sulfonylureas, including glibenclamide and tolbutamide [28]. Zhang et al. [26] reported that the glucose concentration and the presence of glucokinases also influence the excitability of GnRH neurons; whereas GnRH neurons are excited in high glucose concentrations, neuron excitability is inhibited in conditions of low glucose concentrations, such as starvation. Glucokinase facilitates the phosphorylation of glucose to glucose-6-phosphate and is expressed in GnRH neurons. While Kir6.2 and SUR1 transcripts were found to be expressed in all neuronal cells, 66.7% of neuronal pooled cells expressed glucokinase mRNA. This suggests that glucokinase plays a role in regulating GnRH release via the KATP channels [26].

Fig. 2.

Involvement potassium channels in hypothallus-pituitary-ovarian axis. While progesterone secretion is mediated by the Kir6.1/SUR2B, KATP channels subtype in the ovary, Kir6.2/SUR1 subunits is predominantly expressed in gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons in the hypothalamus. The KATP channel Kir6.2/SUR1 modulates the pulsatile release of GnRH, and activity of the KATP channels responds to negative feedback from ovarian steroids-E2 and progesterone. The acetylcholine and oxytocin increase intracellular Ca2+ concentration in lutein-granulosa cells, the intracellular calcium signal affects progesterone release via BKCa. human chorionic gonadotropin stimulates the release of oxytocin, which, along with acetylcholine, acts as an ovarian signaling molecule. LH, luteinizing hormone.

Potassium channels in GnRH neurons form a rich substrate for the modulation of activity. As 2 main components of voltage-gated potassium channel currents in cells, both the slowly inactivating potassium current (IK) and the fast inactivating A-type potassium current (IA) are generated in GnRH neurons. In recent studies, estradiol was shown to suppress both IK and IA, these voltage-gated potassium conductance are largely responsible for the overall excitability and discharge activity in GnRH neurons [29-31]. The expression of genes encoding potassium channel proteins is altered in GnRH neurons at different stages of estrus in mice [32].

Expression and role of potassium channels in the uterus

The human uterus expands drastically during pregnancy owing to uterine smooth muscle hypertrophy, and the myometrium is one of the strongest uterine muscles that facilitates birth [33,34]. The uterus does not play any major role during pregnancy. Uterine quiescence during pregnancy is necessary for preventing preterm labor. Potassium efflux leads to the repolarization of the plasma membrane, which is responsible for maintaining the resting membrane potential. Inadequate repolarization of smooth muscle cells in the myometrium can lead to aberrant uterine activities, such as dystocia, preterm labor, and post-term labor [12]. The myometrium expresses several types of potassium channels, including BKCa, KATP, small-conductance Ca2+-sensitive, voltage-gated, and 2-pore potassium channels [12]. The role of each type of potassium channel in the regulation of basal myometrial contractility and their contribution to molecular expression varies depending on the gestational stage [35].

BKCa channels play a prominent role in inducing smooth muscle relaxation as they mediate the depolarization of the plasma membrane and contribute to the generation of approximately 35% of the total cell repolarizing potassium current [36]. The potassium current density in term mouse myometrium was observed to decrease significantly. The functional importance of the BKCa channels decreases as a result of several factors, including a change in surface negative charges, decreased channel density, a positive shift in voltage-activation relation, and reduced sensitivity to calcium ions [24,37]. Furthermore, BKCa channels are replaced by smaller conductance delayed rectifier channels in the abovementioned period; these remove the noises in the current and generate a smooth current that requires limited rectification [36]. However, there is another explanation for the turnover from uterine quiescence to the state of uterine contraction. First, the sensitivity of BKCa to the intracellular calcium and voltage levels changes owing to alternative splicing of transcripts of the BKCa channel, which is accompanied by post-translational modifications as well. Second, protein kinases exert different modulatory effects based on the gestational stage. Third, Ca2+ levels increase during pregnancy [37,38]. Notably, the differences in the regulation of channel transcripts implies that different populations of channels exist in the myometrium; this alteration in transcripts during pregnancy may be regulated by sex hormones [21,38]. In particular, the expression of β1-subunit transcripts is partially regulated by estrogen and it is observed to peak in early pregnancy [39]. The regulatory β-subunit helps modulate uterine excitability by exhibiting sensitivity to both Ca2+ and voltage during gestation [37].

As BKCa channels play a prominent role in myometrial contraction, several agents that activate and inhibit these channels, including β-adrenoceptor agonists, relaxin, hCG, and nitric oxide (NO), have been studied based on their role in controlling myometrial contraction [35]. Notably, although the BKCa channel is the most abundant potassium channel in the myometrium and contributes to the regulation of myometrial functions, it does not play a role in the regulation of basal or uterine relaxation during late pregnancy or labor [35,40]. The BKCa channels are activated by NS1619, a benzimidazole derivate that promotes the activation of BKCa channels; the administration of this agent did not significantly affect the contractile activity in human term-pregnant myometrium when oxytocin was secreted [41]. These results suggest that although BKCa channels play a more significant role than other potassium channels in myometrial relaxation during the non-pregnancy period and in early gestation, the significance of their regulation is lesser in late gestation.

Instead of the BKCa channel, the KATP, KV, and Slo2.1 (rapidly-gating sodium-activated) potassium channels affect the transition from uterine quiescence in late pregnancy to the state of active contractions that aids the expulsion of the fetus in labor [35,41,42]. The intracellular Na+, K+, and Ca2+ ions and the ion channels are involved in the regulation of uterine relaxation and contraction. The Kir6.1/SUB2B KATP channel is the predominant subtype in the myometrium and ovary [43]. The expression patterns of the BKCa and KATP channels are similar in each gestational stage, while the expression of Kir6.1 and SUR2B transcripts is significantly higher in the non-pregnant state than in late pregnancy before or during labor [43]. The KATP channel activator pinacidil inhibits oxytocin-induced uterine contractions (both in terms of amplitude and frequency) in the myometrium in late pregnancy and in non-pregnant women; its effect was attenuated in the laboring myometrium owing to the differences in expression during gestation and labor [41].

The hyperpolarization of the plasma membranes of myometrial cells depends on the K+ efflux for the maintenance of uterine quiescence, while the depolarization of the membrane potential owing to increased Na+ influx is essential for countering uterine contractions by myocytes. KNa channels, which are high-conductance K+ channels activated by Na+, require high concentrations of intracellular Na+ instead of Ca2+ ions. Recently, Ferreira et al. [42] reported that oxytocin could regulate myometrial smooth muscle cell excitability via the Na+-activated Slo2.1 K+ channel. The peptide-hormone oxytocin regulates the transition from uterine quiescence to contraction. Slick, a rapidly-gating sodium-activated potassium channel, induces K+ efflux and opposes Na+ influx via NALCN (Na+ leak channel, non-selective) at low levels of oxytocin [42]. However, when the levels of oxytocin increase at the end of pregnancy and it binds to its receptors, protein kinase C is activated and SLO2.1 expression is inhibited. As a result, after K+ efflux is reduced, the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels are activated. When Ca2+ influx occurs and actin– myosin cross-bridging is initiated, myometrial contractility is augmented [42].

Small-conductance Ca2+-sensitive and voltage-insensitive potassium channels (SK), voltage-gated potassium channels (KV), and 2-pore potassium channels are also expressed in the myometrium [44,45]. While small-conductance K+ (SKCa) channels and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated K+ (IKCa) channels are expressed in smooth muscle cells, including those of the myometrium, IKCa channels are primarily expressed in immune/inflammatory cells. The role of IKCa channels in the myometrium has not been studied thoroughly [46-48]. Dimethylamine-nitric oxide (DEA/NO) inhibits myometrial contraction via a NO-induced relaxation mechanism. Apamin and scyllatoxin specifically block Ca2+-dependent apamin-sensitive K+ channels (SKCa1 to SKCa3); the administration of 10 nM apamin or scyllatoxin could completely inhibit the DEA/NO-induced relaxation of the myometrium [45]. This indicates that the participation of the SKCa channels in NO-induced myometrial relaxation, especially in the overexpression of the SKCa3 isoform, results in uterine dysfunction and delayed parturition [49]. In mice, the expression of the SKCa3 channel decreases from the midgestational stages; sensitivity of this channel to apamin also reduces from late gestation. SKCa3 immunoreactivity was also observed in telocytes, formerly referred to as interstitial cells of Cajal or interstitial Cajal-like cells (ICLC), in non-pregnant myometrium, as well as in the glandular and luminal endometrial laminal epithelia in rats [46,50,51]. Although similar ICLC have been observed in rodent and human myometrial tissue, the functional role of these cells in the uterus remains unclear [52].

KV channels are the most diverse of potassium channels. The α-subunits of voltage-gated KV channels form the conductance pore and there are 12 classes and 40 types of α-subunits of KV channels. Voltage-gated KV channels are blocked by 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) or tetraethylammonium (TEA). The administration of both 1 and 5 mM 4-AP significantly enhanced myometrial contractility in the non-pregnant, as well as mid- and late-pregnant myometrium [35]. These results indicate that voltage-gated KV channels contribute to uterine quiescence during mid to late pregnancy. Although treatment with TEA and 4-AP did not affect the contraction interval, the duration and amplitude of myometrial contractions were increased in both cases. The blockade response of Kv channels by 4-AP is not mediated by BKCa channels of the endometrium and nerves in the myometrium [44]. It has been suggested that several different KV channel subtypes are present in the myometrium of both non-pregnant and term-pregnant mice. Myometrial contractions in non-pregnant mice were induced even at surprisingly low concentrations of 4-AP [53]. The Kv4.3 channel is not expressed in term-pregnant tissues. Phrixotoxin-2, which is a KV4.2/KV4.3 blocker, induced contractions in non-pregnant myometrium, whereas the same was not induced in pregnant myometrium [44]. The genes encoding voltage-gated KV channels can be categorized into 9 families, named KCNA to KCNV gene families (Table 2). Two types of KV channels encoded by members of the KCNQ (Kv7) and KCNH (Kv11) gene families appear to act as key regulators of uterine contractility and may serve as novel therapeutic targets [52]. All isoforms of KCNQ are expressed in non-pregnant mice, with KCNQ1 (Kv7.1) as the dominant form [54]. The KCNQ and KCNE isoforms are expressed in early and late gestational stages in mice as well, the majority of KCNQ isoforms are upregulated in late pregnancy [54]. KCNE is a type of β-subunit associated with voltage-gated KCNQ α-subunits. These findings suggest that instead of facilitating the maintenance uterine quiescence in early pregnancy, these proteins primarily regulate myometrial contractility in the late stages of pregnancy. All KCNQ genes, except KCNQ5, were also observed to be expressed in human term myometrium. Flupirtine and retigabine, which are activators to the KCNQ-encoded K+ channel (K7), rapidly inhibited spontaneous and oxytocin-mediated myometrial contractility by 40–70% [54]. Ether-à-go-go-related genes or ERGs (ERG1–3) are members of the KCNH gene family (KCNH1–3). The ERG-encoded channel blockers dofetilide, E4031, and Be-KM1 increased oxytocin-mediated contractions in mouse myometrium, while the ERG activators PD118057 and NS1643 inhibited spontaneous contraction [55]. In summary, although several types of KV channels are expressed in uterine myometrium, there are contradictory results with respect to their upregulation or downregulation based on the gestational stage. K7 (KCNQ) and K11 (KCNH) channels play central roles in regulating myometrial activity at term and are possible targets for tocolytic agents in preterm labor [54].

The TWIK-related K+ (TREK-1) channel is a 2-pore K+ channel. TREK-1 is a stretch-activated tetraethyl ammoniuminsensitive K+ channel that is sensitive to pH, hypoxia, stretching, temperature, phosphorylation, and NO [56]. This channel is expressed in human myometrium, particularly during pregnancy. Its expression is upregulated during pregnancy and is induced upon stretching [57]. The TREK-1 channel plays a role in the regulation of uterine contractions. The TREK-1 activator arachidonic acid was observed to reduce uterine contractions, while the TREK-1 blocker L-methionine exerted the opposite effect. Interestingly, this response is related to the effect of progesterone on uterine relaxation. Both progesterone and arachidonic acid were observed to exert similar effects on TREK-1 activity. The progesterone-induced inhibition of uterine contraction was reversed in the presence of the TREK-1 inhibitor L-methionine [33]. Furthermore, since the expression and activity of this channel are essentially induced in response to uterine wall stretching, TREK-1 may play a significant role in the determination of the type of pregnancy. Different TREK-1 expression patterns and activities in preterm versus term and in singleton versus twin pregnancies may help explain the differences in the uterine contractile response in each case [58].

Expression of potassium channels in the placenta

The placenta partakes in gas exchange, nutrient delivery, and waste transfer between the mother and fetus and has immunological and metabolic functions. Chorionic villi are in contact with maternal blood and are covered by a continuous layer of syncytiotrophoblasts. Two different lineages of undifferentiated cytotrophoblastic stem cells differentiate into villous and interstitial cytotrophoblastic cells. Syncytiotrophoblastic cells secrete pregnancy-associated hormones, including hCG and progesterone. hCG is a glycoprotein hormone and shares a common α-subunit with LH and FSH. hCG is produced by placental syncytiotrophoblasts after implantation in a process modulated by the partial pressure of oxygen, the presence of reactive oxygen species, and potassium channels [13]. It stimulates progesterone production, decidualization, angiogenesis, and cytotrophoblast differentiation [59]. KV1.5 and KV2.1 are classic delayed rectifier KV channels that are sensitive to oxygen and TEA [7]. These channels are expressed in the syncytiotrophoblast. Díaz et al. [13] reported that the expression oxygen-sensitive KV channels could be downregulated under hypoxic conditions (1% PO2) and lead to lower hCG secretion from the placenta. Oxidative stress mediates hCG secretion and K+ permeability, and the regulation of this mechanism depends on the partial pressure of oxygen [13].

Other potassium channels, including Kv9.3, Kir6.1, TASK-1, and BKCa channels are expressed in the human placental vasculature. It was also reported that all calcium-activated potassium channels (BKCa, IKCa, and SKCa) and KV channels are expressed in the smooth muscle cells of chorionic plate resistance arteries (CPAs) [60,61]. The low-resistance feto–placental circulation and vasodilatation are essential for the successful maintenance of pregnancy. Local vasodilators such as NO, prostacyclin, and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors (EDHFs) mediate vasorelaxation [62-64]. EDHFs are as potent as NO and prostaglandin as blood pressure regulators. Endothelial intermediate and small-conductance KCa channels (IKCa and SKCa) are major components of EDHFs [65]. IKCa and SKCa are primarily expressed in the endothelial and smooth muscle cells of placental CPAs. In the endothelium, these channels may play a more important role in vascular function. Endothelial K+ currents were observed to be inhibited in hypoxic conditions owing to the downregulation of IKCa and SKCa expression in the ovine uterine arteries and in porcine coronary arteries [66,67]. Endothelium-derived NO may regulate IKCa- and SKCa-dependent vasodilatation; the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and inducible NOS was observed to be significantly downregulated in women with preeclampsia. Therefore, the abnormal expression or dysregulation of IK and SK channels in the endothelium and smooth muscle cells of CPAs, NO, and EDHFs may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia [62]. In human placental mitochondria, the potassium channel is formed by the subunit Kir6.1, which contributes to placental mitochondrial steroidogenesis by facilitating cholesterol uptake and intermembrane translocation through a mechanism independent of the transport of K+ ions inside the mitochondria [68].

Conclusion

This mini-review provides insight into the roles of potassium channels, which form the largest and most diverse ion channel family, in the relaxation of smooth muscle cells and vasodilatation via the regulation of cell membrane potential as well as in specialized cellular functions, such as the regulation of female sex hormone secretion, relaxation of uterine muscles in pregnancy, turnover into labor, and the successful maintenance of pregnancy mediated by the regulation of vascular tone in placental CPAs. Among the ATP-sensitive potassium channels, Kir6.1/SUR2B in GCs and Kir6.2/SUR1 expressed in GnRH neurons in the hypothalamus modulate progesterone release and a negative feedback mechanism. All 5 types of potassium channels are expressed in uterine myometrium. Calcium-activated potassium channels play a major role in the relaxation of smooth muscles in non-pregnant state as well as in early to mid-term pregnancy. Other channels affect the transition from uterine quiescence to active myometrial contractions in late pregnancy, including voltage-activated and rapidly-gating sodium-activated potassium channels. The prevention of hypoxia in the placenta is important for treating preeclampsia. Endothelial intermediate- and small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels mediate the vasodilatation of placental CPAs via the secretion of NO and EDHFs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Korean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and NIH NIDDK RO1-DK099284 (TW). We thank Ms. Leah Sanders for editing this paper and Dr. Bin Zhang, from Nanjing Medical University, Jiangsu China, for providing Fig. 2.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Ethical approval

This study does not require approval of the Institutional Review Board because no patient data is contained in this article. The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent

Written informed consent and the use of images from patients are not required for the publication.

References

- 1.Aronson PS, Giebisch G. Effects of pH on potassium: new explanations for old observations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1981–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011040414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gumz ML, Rabinowitz L, Wingo CS. An integrated view of potassium homeostasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:60–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1313341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer BF. Regulation of potassium homeostasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1050–60. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08580813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DuBose TD., Jr Regulation of potassium homeostasis in CKD. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017;24:305–14. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunz L, Richter JS, Mayerhofer A. The adenosine 5'-triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel in endocrine cells of the human ovary: role in membrane potential generation and steroidogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1950–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comes N, Serrano-Albarrás A, Capera J, Serrano-Novillo C, Condom E, Ramón Y Cajal S, et al. Involvement of potassium channels in the progression of cancer to a more malignant phenotype. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1848 10 Pt B:2477–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burg ED, Remillard CV, Yuan JX. K+ channels in apoptosis. J Membr Biol. 2006;209:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0838-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hebert SC. An ATP-regulated, inwardly rectifying potassium channel from rat kidney (ROMK) Kidney Int. 1995;48:1010–6. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian C, Zhu R, Zhu L, Qiu T, Cao Z, Kang T. Potassium channels: structures, diseases, and modulators. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2014;83:1–26. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuang Q, Purhonen P, Hebert H. Structure of potassium channels. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:3677–93. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1948-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wareing M, Greenwood SL. Review: potassium channels in the human fetoplacental vasculature. Placenta. 2011;32 Suppl 2:S203–6. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brainard AM, Korovkina VP, England SK. Potassium channels and uterine function. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:332–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Díaz P, Sibley CP, Greenwood SL. Oxygen-sensitive K+ channels modulate human chorionic gonadotropin secretion from human placental trophoblast. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hummitzsch K, Anderson RA, Wilhelm D, Wu J, Telfer EE, Russell DL, et al. Stem cells, progenitor cells, and lineage decisions in the ovary. Endocr Rev. 2015;36:65–91. doi: 10.1210/er.2014-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engel S, Klusmann H, Ditzen B, Knaevelsrud C, Schumacher S. Menstrual cycle-related fluctuations in oxytocin concentrations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2019;52:144–55. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunz L, Thalhammer A, Berg FD, Berg U, Duffy DM, Stouffer RL, et al. Ca2+-activated, large conductance K+ channel in the ovary: identification, characterization, and functional involvement in steroidogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:5566–74. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayerhofer A, Föhr KJ, Sterzik K, Gratzl M. Carbachol increases intracellular free calcium concentrations in human granulosa-lutein cells. J Endocrinol. 1992;135:153–9. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1350153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayerhofer A, Sterzik K, Link H, Wiemann M, Gratzl M. Effect of oxytocin on free intracellular Ca2+ levels and progesterone release by human granulosa-lutein cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:1209–14. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.5.8077313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Copland JA, Zlatnik MG, Ives KL, Soloff MS. Oxytocin receptor regulation and action in a human granulosalutein cell line. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1230–6. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.5.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traut MH, Berg D, Berg U, Mayerhofer A, Kunz L. Identification and characterization of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in granulosa cells of the human ovary. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross SA, Newton JM, Hughes FM., Jr Decreased intracellular potassium levels underlie increased progesterone synthesis during ovarian follicular atresia. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:1755–60. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.6.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujita R, Kimura S, Kawasaki S, Watanabe S, Watanabe N, Hirano H, et al. Electrophysiological and pharmacological characterization of the K(ATP) channel involved in the K+-current responses to FSH and adenosine in the follicular cells of Xenopus oocyte. J Physiol Sci. 2007;57:51–61. doi: 10.2170/physiolsci.RP010006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chien EK, Zhang Y, Furuta H, Hara M. Expression of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel subunits in female rat reproductive tissues: overlapping distribution of messenger ribonucleic acid for weak inwardly rectifying potassium channel subunit 6.1 and sulfonylurea-binding regulatory subunit 2. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1121–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70604-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agoston A, Kunz L, Krieger A, Mayerhofer A. Two types of calcium channels in human ovarian endocrine cells: involvement in steroidogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4503–12. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunz L, Rämsch R, Krieger A, Young KA, Dissen GA, Stouffer RL, et al. Voltage-dependent K+ channel acts as sex steroid sensor in endocrine cells of the human ovary. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:167–74. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang C, Bosch MA, Levine JE, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons express K(ATP) channels that are regulated by estrogen and responsive to glucose and metabolic inhibition. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10153–64. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1657-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang W, Acosta-Martínez M, Levine JE. Ovarian steroids stimulate adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel subunit gene expression and confer responsiveness of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator to KATP channel modulation. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2423–32. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashcroft FM, Gribble FM. New windows on the mechanism of action of K(ATP) channel openers. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:439–45. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01563-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv OK, Ibrahim N, Lagrange AH, Wagner EJ. Estrogen modulation of K(+) channel activity in hypothalamic neurons involved in the control of the reproductive axis. Steroids. 2002;67:447–56. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(01)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pielecka-Fortuna J, DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. Voltage-gated potassium currents are targets of diurnal changes in estradiol feedback regulation and kisspeptin action on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in mice. Biol Reprod. 2011;85:987–95. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.093492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norberg R, Campbell R, Suter KJ. Ion channels and information processing in GnRH neuron dendrites. Channels (Austin) 2013;7:135–45. doi: 10.4161/chan.24228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vastagh C, Solymosi N, Farkas I, Liposits Z. Proestrus differentially regulates expression of ion channel and calcium homeostasis genes in GnRH neurons of mice. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:137. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin Z, Li Y, He W, Li D, Li H, Yang Y, et al. Progesterone inhibits contraction and increases TREK-1 potassium channel expression in late pregnant rat uterus. Oncotarget. 2017;9:651–61. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin Z, Sada AA, Reslan OM, Narula N, Khalil RA. Increased MMPs expression and decreased contraction in the rat myometrium during pregnancy and in response to prolonged stretch and sex hormones. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303:E55–70. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00553.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aaronson PI, Sarwar U, Gin S, Rockenbauch U, Connolly M, Tillet A, et al. A role for voltage-gated, but not Ca2+-activated, K+ channels in regulating spontaneous contractile activity in myometrium from virgin and pregnant rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:815–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang SY, Yoshino M, Sui JL, Wakui M, Kao PN, Kao CY. Potassium currents in freshly dissociated uterine myocytes from non-pregnant and late-pregnant rats. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:737–56. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.6.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benkusky NA, Fergus DJ, Zucchero TM, England SK. Regulation of the Ca2+-sensitive domains of the maxi-K channel in the mouse myometrium during gestation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27712–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000974200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pérez G, Toro L. Differential modulation of large-conductance KCa channels by PKA in pregnant and non-pregnant myometrium. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:C1459–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.5.C1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benkusky NA, Korovkina VP, Brainard AM, England SK. Myometrial maxi-K channel beta1 subunit modulation during pregnancy and after 17beta-estradiol stimulation. FEBS Lett. 2002;524:97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okawa T, Longo M, Vedernikov YP, Chwalisz K, Saade GR, Garfield RE. Role of nucleotide cyclases in the inhibition of pregnant rat uterine contractions by the openers of potassium channels. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:913–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sadlonova V, Franova S, Dokus K, Janicek F, Visnovsky J, Sadlonova J. Participation of BKCa2+ and KATP potassium ion channels in the contractility of human term pregnant myometrium in in vitro conditions. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:215–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreira JJ, Butler A, Stewart R, Gonzalez-Cota AL, Lybaert P, Amazu C, et al. Oxytocin can regulate myometrial smooth muscle excitability by inhibiting the Na+ -activated K+ channel, Slo2.1. J Physiol. 2019;597:137–49. doi: 10.1113/JP276806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curley M, Cairns MT, Friel AM, McMeel OM, Morrison JJ, Smith TJ. Expression of mRNA transcripts for ATP-sensitive potassium channels in human myometrium. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:941–5. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.10.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith RC, McClure MC, Smith MA, Abel PW, Bradley ME. The role of voltage-gated potassium channels in the regulation of mouse uterine contractility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2007;5:41. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-5-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Modzelewska B, Kostrzewska A, Sipowicz M, Kleszczewski T, Batra S. Apamin inhibits NO-induced relaxation of the spontaneous contractile activity of the myometrium from non-pregnant women. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noble K, Floyd R, Shmygol A, Shmygol A, Mobasheri A, Wray S. Distribution, expression and functional effects of small conductance Ca-activated potassium (SK) channels in rat myometrium. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenbaum ST, Larsen T, Joergensen JC, Bouchelouche PN. Relaxant effect of a novel calcium-activated potassium channel modulator on human myometrial spontaneous contractility in vitro. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2012;205:247–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jensen BS, Hertz M, Christophersen P, Madsen LS. The Ca2+-activated K+ channel of intermediate conductance:a possible target for immune suppression. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2002;6:623–36. doi: 10.1517/14728222.6.6.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bond CT, Sprengel R, Bissonnette JM, Kaufmann WA, Pribnow D, Neelands T, et al. Respiration and parturition affected by conditional overexpression of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel subunit, SK3. Science. 2000;289:1942–6. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenbaum ST, Svalø J, Nielsen K, Larsen T, Jørgensen JC, Bouchelouche P. Immunolocalization and expression of small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in human myometrium. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:3001–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01627.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rahbek M, Nazemi S, Odum L, Gupta S, Poulsen SS, Hay-Schmidt A, et al. Expression of the small conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channel subtype 3 (SK3) in rat uterus after stimulation with 17β-estradiol. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greenwood IA, Tribe RM. Kv7 and Kv11 channels in myometrial regulation. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:503–9. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.075754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gutman GA, Chandy KG, Adelman JP, Aiyar J, Bayliss DA, Clapham DE, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XLI. Compendium of voltage-gated ion channels: potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:583–6. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCallum LA, Pierce SL, England SK, Greenwood IA, Tribe RM. The contribution of Kv7 channels to pregnant mouse and human myometrial contractility. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:577–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greenwood IA, Yeung SY, Tribe RM, Ohya S. Loss of functional K+ channels encoded by ether-à-go-go-related genes in mouse myometrium prior to labour onset. J Physiol. 2009;587:2313–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heyman NS, Cowles CL, Barnett SD, Wu YY, Cullison C, Singer CA, et al. TREK-1 currents in smooth muscle cells from pregnant human myometrium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C632–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00324.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buxton IL, Heyman N, Wu YY, Barnett S, Ulrich C. A role of stretch-activated potassium currents in the regulation of uterine smooth muscle contraction. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32:758–64. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yin Z, He W, Li Y, Li D, Li H, Yang Y, et al. Adaptive reduction of human myometrium contractile activity in response to prolonged uterine stretch during term and twin pregnancy. Role of TREK-1 channel. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;152:252–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weedon-Fekjær MS, Taskén K. Review: Spatiotemporal dynamics of hCG/cAMP signaling and regulation of placental function. Placenta. 2012;33 Suppl:S87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brereton MF, Wareing M, Jones RL, Greenwood SL. Characterisation of K+ channels in human fetoplacental vascular smooth muscle cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wareing M, Bai X, Seghier F, Turner CM, Greenwood SL, Baker PN, et al. Expression and function of potassium channels in the human placental vasculature. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R437–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00040.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li FF, He MZ, Xie Y, Wu YY, Yang MT, Fan Y, et al. Involvement of dysregulated IKCa and SKCa channels in preeclampsia. Placenta. 2017;58:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.07.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kang KT. Endothelium-derived relaxing factors of small resistance arteries in hypertension. Toxicol Res. 2014;30:141–8. doi: 10.5487/TR.2014.30.3.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choi SK, Hwang JY, Lee J, Na SH, Ha JG, Lee HA, et al. Gene Expression of Heme Oxygenase-1 and Nitric Oxide Synthase on Trophoblast of Preeclampsia. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54:341–8. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Köhler R, Hoyer J. The endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor: insights from genetic animal models. Kidney Int. 2007;72:145–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu R, Hu XQ, Xiao D, Yang S, Wilson SM, Longo LD, et al. Chronic hypoxia inhibits pregnancy-induced upregulation of SKCa channel expression and function in uterine arteries. Hypertension. 2013;62:367–74. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang Q, Huang JH, Man YB, Yao XQ, He GW. Use of intermediate/small conductance calcium-activated potassium-channel activator for endothelial protection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:501–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Milan R, Flores-Herrera O, Espinosa-Garcia MT, OlveraSanchez S, Martinez F. Contribution of potassium in human placental steroidogenesis. Placenta. 2010;31:860–6. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]