Abstract

Background

Digital nutrition apps that monitor or provide recommendations on diet have been found to be effective in behavior change and weight reduction among individuals with obesity. However, there is less evidence on how integration of personalized nutrition recommendations and changing the food purchasing environment through online meal planning and grocery delivery, meal kits, and grocery incentives impacts weight loss among individuals with obesity.

Objective

The objective of this observational longitudinal study was to examine weight loss and predictors of weight loss among individuals with obesity who are users of a digital nutrition platform that integrates tools to provide nutrition recommendations and changes in the food purchasing environment grounded in behavioral theory.

Methods

We included 8977 adults with obesity who used the digital Foodsmart platform, created by Zipongo, Inc, DBA Foodsmart between January 2013 and April 2020. We retrospectively analyzed user characteristics and their associations with weight loss. Participants reported age, gender, height, at least 2 measures of weight, and usual dietary intake. Healthy Diet Score, a score to measure overall diet quality, was calculated based on responses to a food frequency questionnaire. We used paired t tests to compare differences in baseline and final weights and baseline and final Healthy Diet Scores. We used univariate and multivariate logistic regression models to estimate odds ratios and 95% CI of achieving 5% weight loss by gender, age, baseline BMI, Healthy Diet Score, change in Healthy Diet Score, and duration of enrollment. We conducted stratified analyses to examine mean percent weight change by enrollment duration and gender, age, baseline BMI, and change in Healthy Diet Score.

Results

Over a median (IQR) of 9.9 (0.03-54.7) months of enrollment, 59% of participants lost weight. Of the participants who used the Foodsmart platform for at least 24 months, 33.3% achieved 5% weight loss. In the fully adjusted logistic regression model, we found that baseline BMI (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.02-1.03; P<.001), baseline Healthy Diet Score (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.05-1.08; P<.001), greater change in Healthy Diet Score (OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.11-1.14; P<.001), and enrollment length (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.23-1.32; P<.001) were all significantly associated with higher odds of achieving at least 5% weight loss.

Conclusions

This study found that a digital app that provides personalized nutrition recommendations and change in one’s food purchasing environment appears to be successful in meaningfully reducing weight among individuals with obesity.

Keywords: digital, nutrition, meal planning, weight loss, obese, food environment, food ordering, food purchasing, behavioral economics, behavior change, eating behavior, mHealth, app

Introduction

The increasing prevalence of obesity worldwide is a critical public health problem [1,2]. In the United States, about 39.6% of adults 20 and older were considered obese in the years 2015-2016, and the prevalence is projected to increase [3]. Overweight and obesity pose serious health challenges as they are strong risk factors for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, many cancers, and mortality [1,4,5].

The prevention and management of obesity are extremely necessary given the potential health and cost consequences [6]. For decades, there has been mounting evidence from large trials such as the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) showing that change in lifestyle, often related to weight reduction, can have dramatic effects on health and chronic disease [7-12]. However, interventions like DPP have failed to sustain weight loss more than 18-24 months and can be costly due to coaching time and the cycles of losing and regaining weight [13,14].

Digital health technologies that incorporate nutrition education and monitoring have gained increasing popularity to change and manage dietary choices [15-17]. Previous studies on mobile apps to improve nutrition are promising as their results indicate that digital nutrition interventions may be effective in changing dietary behavior to improve weight, glucose, and blood pressure among healthy individuals and people at risk of or with chronic disease [18-21]. While many of these apps provide general diet recommendations, few apps have a decision engine capable of providing personalized dietary advice, meal planning assistance, and online grocery delivery to users [16].

Meal planning and at-home cooking have been found to be associated with greater adherence to dietary guidelines, increased fruit and vegetable intake, and greater variety of foods consumed [22,23]. Meal planning behaviors, including frequency of planning meals ahead of time, grocery shopping and cooking, have been associated with lower likelihood of obesity in men and women [23].

To our knowledge, no studies with meaningful scale have examined the effect of a digital technology that provides personalized healthy meal plans and changes in the food purchasing environment (through online grocery shopping, purchase discounts, delivery, and meal kits) on health outcomes. There is a need for additional evidence on how digital technologies that alter behavioral economics, such as food purchasing, might play a role in improving diet and driving more cost-effective health outcomes for individuals with obesity.

Our goal was to conduct an observational longitudinal study leveraging existing data from a digital nutrition platform to investigate the effectiveness of a personalized nutrition, meal planning, and food purchasing program on weight loss among individuals with obesity.

Methods

Study Population

The current study is a longitudinal analysis of 8977 adults with obesity (aged 18 to 80 years, living in the United States) who enrolled in the Foodsmart platform. Of the 888,999 users who had enrolled up to April 2020, we excluded individuals who did not report weight (n=562,276), those who reported extreme values for height (<54 in or >78 in, ie, <1.37 m or >1.98 m) or weight (<60 lb or >400 lb, ie, <27.2 kg or >181.4 kg) (n=25,946), and those who were not obese (BMI<30 kg/m2) at the time of enrollment (n=200,308). We further excluded those who reported BMI after more than 3 days from joining Foodsmart, those whose BMI changed more than 15 kg/m2 in less than 10 months, and participants with greater than 16% weight change in less than 1 month (n=13,548). We additionally excluded those who did not report weight at least 2 times (n=9023) and participants who did not fill out the Nutriquiz survey twice (n=68,921).

Foodsmart Platform

Foodsmart (Zipongo Inc DBA Foodsmart) built a digital nutrition platform called Foodsmart that is designed to make healthier dietary choices simple and sustainable through personalization of nutrition and meal/recipe recommendations by creating a food purchasing environment that provides healthy options for all people, whether they enjoy cooking, prefer to use meal kits, or prefer prepared meals. Foodsmart is made up of 2 components (FoodSmart and FoodsMart) with self-directed tools that drive knowledge, motivation, and planning to make it easier and more affordable to prepare tasty, healthy food at home (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Components and tools of Foodsmart.

The platform was developed using Prochaska’s Theory of Change model as the baseline theory supplemented with elements from the Behaviour Change Techniques Taxonomy [24,25] (Table 1). The tools from both FoodSmart and FoodsMart are designed to target all stages (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance) of behavior change in healthier eating. These tools encourage users to reflect and assess their dietary habits with Nutriquiz, helping create a specific plan for users to eat healthier daily, offering tools to purchase healthy foods, and providing incentives and communication to maintain healthy behaviors.

Table 1.

Foodsmart platform components and tools linked with behavior change stages and techniques.

| Foodsmart components and tools | Stages of change [24] | Behaviour Change Techniques [25] | |

| FoodSmart | |||

|

|

Nutriquiz dietary assessment and re-assessment and dietary recommendations |

|

|

|

|

Family meal planning (recipe recommendations for each meal through linkage to recipe database) |

|

|

|

|

Social liking and commenting of recipes |

|

|

|

|

Enrollment and activation marketing (incentives, enrollment emails, newsletters) |

|

|

| FoodsMart (advertising of unhealthy foods is filtered out) | |||

|

|

Online grocery list and food ordering (including prepared meals and meal kits) |

|

|

|

|

Food discounts and incentives |

|

|

The first component is FoodSmart, which contains the in-app Nutriquiz, a dietary assessment (based on the National Cancer Institute’s Diet History Questionnaire). Users can take Nutriquiz to report their dietary habits, which provides immediate and specific feedback on aspects of their diet to improve on as well as personalized meal and recipe planning based on the Nutriquiz results. Over time, users can retake the Nutriquiz assessment to monitor their own progress related to specific nutrients and food groups as well as their progress on health goals, like weight. The second component is FoodsMart, which helps reset one’s default behavioral economics by altering the food purchasing environment. This is achieved through personalized meal plan conversion to a grocery list and integrated online ordering and delivery of groceries, meal kits, and prepared foods, where food advertising paid for by food manufacturers is removed and replaced with nudges to make healthier substitutions that align with user preferences and their personalized meal planning. Customized grocery discounts on healthier options help the user save money and further nudge the user to make healthier choices. The Foodsmart platform has been in use since 2013; and 90% of users enrolled in 2017 or later, after most of the major content and design changes to the platform were made (Multimedia Appendix 1). The platform has evolved over time, with the most significant change being the addition of grocery and food ordering in the last few years. The product is available through certain health plans and employers who have signed up for Foodsmart, and they can provide this product as an option or benefit for their members/employees to enroll in. It is available to be used on the web, iOS, and Android operating systems.

Measurements

All data were self-reported through the Foodsmart app during the study period. When users created their account, they were prompted to fill out a survey created by Foodsmart called Nutriquiz, a 53-item food frequency questionnaire adapted from the National Cancer Institute Diet History Questionnaire, which has been previously validated [26]. The questionnaire ascertains biological sex, birth date, weight, and usual intake of food groups and nutrients. For example, it asks, “How often do you eat fruit?” Possible responses include “never,” “monthly,” “weekly,” and “daily.” Other food groups assessed included vegetables, whole grains, proteins, carbohydrates, fats, fiber, sodium, and water. Foodsmart’s research team created a healthy diet score called Healthy Diet Score, which is based on the Alternative Healthy Eating Index-2010 (AHEI-2010) and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) Healthy Diet Score [27,28]. Similar to the AHEI-2010, the Healthy Diet Score includes fruits, vegetables, and sodium components; and each component is scored 1-10 using absolute cutoffs. In order to keep the score concise, the Healthy Diet Score combined macronutrient components in a similar fashion to the CSIRO Healthy Diet Score, which includes only 1 category each for protein, carbohydrates, and fats. Additionally, it has a component for fluids, which was modified to be hydration in the Healthy Diet Score since percent fluid intake is more relevant than total quantity of fluids. For calculation of the Healthy Diet Score, participants were assigned a score from 0-10 for 7 components: fruit, vegetable, protein ratio (white meat/vegetarian protein to red/processed meat), carbohydrate ratio (total fiber to total carbohydrate), fat ratio (polyunsaturated to saturated/trans fats), sodium, and hydration (percent of daily fluid goal). Higher scores indicated healthier habits. A total Healthy Diet Score to evaluate overall diet quality was calculated by summing the scores of the 7 components, with the total possible score ranging from 0 to 70. Change in Healthy Diet Score was calculated as the difference between the first Healthy Diet Score and the last Healthy Diet Score. We compared participants whose Healthy Diet Score decreased or was stable (no improvement in diet quality) with those participants whose Healthy Diet Score increased (improvement in diet quality) between the first and last report. We collapsed decreased and stable categories due to a low number of participants in the stable category.

Participants were asked to add weight and height data when they joined and could update their weight at any time during usage of the platform. Baseline BMI was calculated as first weight entry in kilograms divided by height in square meters (kg/m2). We categorized participants by baseline obesity class. Class 1 obesity was defined as a BMI between 30 to 34.9 kg/m2; class 2 was defined as a BMI of 35 to 39.9 kg/m2; and class 3 was defined as a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or higher. To calculate a change in weight, we subtracted the last reported weight from the first reported weight. Our primary outcome was 5% or greater weight loss, which has been found to be clinically significant and associated with improvements in cardiometabolic risk factors such as lipid profile and insulin sensitivity [9,12,29,30].

Duration of enrollment (in months) in Foodsmart was calculated as follows: the number of days between the date on which participants initially entered their weight and the date on which they entered their last follow-up weight was calculated and divided by a factor of 30.437 to convert to months. We classified participants into enrollment categories of 0 to 6 months, greater than 6 to 12 months, greater than 12 to 18 months, greater than 18 to 24 months, and 24 months or greater. For stratified analyses, we collapsed the greater than 18 to 24 months and 24 months or greater into one category of greater than 18 months.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine baseline characteristics of the total study population and to compare whether participants lost at least 5% of their initial body weight. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies (%) and continuous variables were reported as mean (SD). Chi-square tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used to test differences for categorical and continuous variables, respectively, between participants who achieved 5% weight loss and participants who did not.

We examined the change in weight and Healthy Diet Score by using paired t tests between baseline and final weights and Healthy Diet Scores of participants. We then used univariate logistic regression models to estimate odds ratios and 95% CI between achievement of 5% weight loss and independent variables: gender, age, baseline BMI, baseline Healthy Diet Score (per 2-point increase), change in Healthy Diet Score (per 2-point increase), and length of enrollment (per 6 months). Multivariate logistic regression models were adjusted for variables that were statistically significant to investigate independent associations with achievement of 5% weight loss.

Further, we conducted stratified analyses to examine differences in percent weight change by enrollment length and stratified by gender, age category, BMI class, and change in Healthy Diet Score. We used bar graphs to visualize differences and ANOVA tests to statistically test for differences, using a Bonferroni-corrected P value of .0031 to account for multiple comparisons.

We considered a P value smaller than .05 to be significant for all tests except for the ANOVA tests used for detecting differences in stratified groups. R studio version 1.2.5033 and Stata version 16 (StataCorp) were used for all analyses.

The study was declared exempt from institutional review board oversight by the Pearl Institutional Review Board given the retrospective design of the study and less than minimal risk to participants.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the total study sample and stratified by whether participants achieved 5% weight loss are shown in Table 2. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies (%) and continuous variables were reported as mean (SD).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of Foodsmart users.

|

|

|

Total (N=8977) | Did not lose ≥5% of initial weight (n=6838) | Lost ≥5% of initial weight (n=2139) | P valuea |

| Male, % | 20.1 | 20.1 | 20.2 | .9 | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 46.6 (11.0) | 46.3 (11.0) | 47.3 (11.0) | .01 | |

| Height, m, mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | .1 | |

| Baseline weight, kg, mean (SD) | 101.7 (18.3) | 101.2 (18.1) | 103.4 (18.9) | <.001 | |

| Baseline BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 36.3 (5.6) | 36.2 (5.6) | 36.8 (5.8) | <.001 | |

| Obesity category | <.001 | ||||

|

|

Obesity class 1 (30-34.9 kg/m2), % | 52.3 | 53.4 | 48.7 |

|

|

|

Obesity class 2 (35-39.9 kg/m2), % | 26.7 | 26.6 | 27.0 |

|

|

|

Obesity class 3 (≥40 kg/m2), % | 21.1 | 20.1 | 24.4 |

|

| Baseline Healthy Diet Score (0-70), mean (SD) |

30.3 (8.6) | 30.2 (8.6) | 30.6 (8.6) | .1 | |

| Final Healthy Diet Score (0-70), mean (SD) | 32.6 (8.5) | 31.9 (8.5) | 34.8 (8.3) | <.001 | |

| Change in Healthy Diet Score, mean (SD) | 2.3 (7.5) | 1.7 (7.3) | 4.2 (7.9) | <.001 | |

| Enrollment length, months, mean (SD) | 11.4 (8.3) | 10.7 (8.1) | 13.6 (8.3) | <.001 | |

| Weight change, %, mean (SD) | –1.5 (7.5) | 1.5 (4.9) | –11.1 (6.4) | <.001 | |

| Weight change, kg, mean (SD) | –1.7 (7.9) | 1.4 (5.0) | –11.6 (7.7) | <.001 | |

aChi-square tests and analysis of variances tests were used to test differences for categorical and continuous variables.

Using t tests, we found that final BMI was significantly lower than the baseline BMI (P<.001); and final Healthy Diet Score was significantly higher than the baseline Healthy Diet Score (P<.001). In total, 59% of participants reported losing weight, and 24% reported loss of at least 5% of their initial weight. Compared to participants who did not lose at least 5% of their initial weight, those who did were more likely to be slightly older, have a slightly higher baseline weight, be classified as obesity class 3, have a higher change in Healthy Diet Score, and be enrolled in the Foodsmart program longer (Table 2). Their baseline Healthy Diet Scores were comparable.

Predictors of At Least 5% Weight Loss

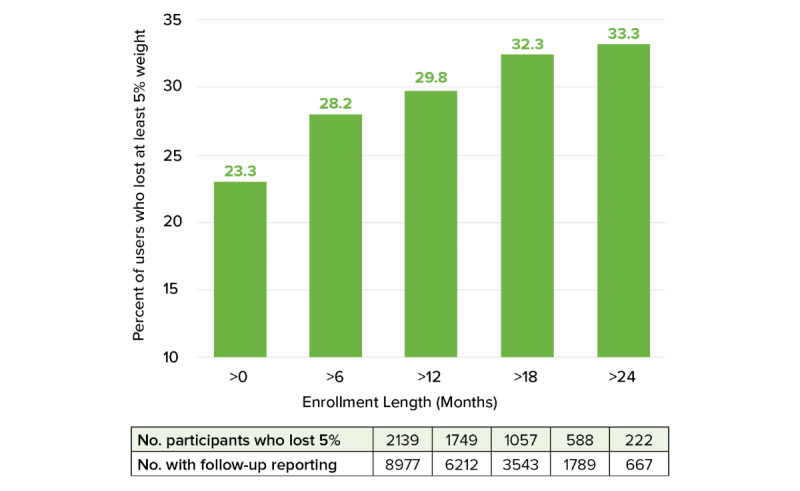

The percentage of users who lost at least 5% of their initial weight increased with longer enrollment duration (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percent of users who lost at least 5% of initial weight by cumulative enrollment duration.

Individual variables contributing to at least 5% weight loss were assessed using univariate logistic regression models (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors contributing to at least 5% weight loss in univariate and multivariate logistic regression models.

|

|

Univariate OR (95% CI) |

P value | Multivariate OR (95% CI) |

P value |

| Gender (male) | 1.01 (0.89-1.14) | .9 | 1.03 (0.91-1.17) | .7 |

| Age, years | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | <.001 | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | .4 |

| Baseline BMI, kg/m2 | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | <.001 | 1.02 (1.02-1.03) | <.001 |

| Baseline Healthy Diet Score, per 2-point increase |

1.01 (1.00-1.02) | <.001 | 1.06 (1.05-1.08) | <.001 |

| Change in Healthy Diet Score, per 2-point increase |

1.09 (1.08-1.11) | <.001 | 1.12 (1.11-1.14) | <.001 |

| Enrollment length, per 6 months | 1.28 (1.24-1.32) | <.001 | 1.28 (1.23-1.32) | <.001 |

We collectively analyzed the variables and 5% weight loss in a multivariate logistic regression model. Baseline BMI, baseline Healthy Diet Score, greater change in Healthy Diet Score, and enrollment length were all directly associated with higher odds of achieving at least 5% weight loss.

Stratified Analyses

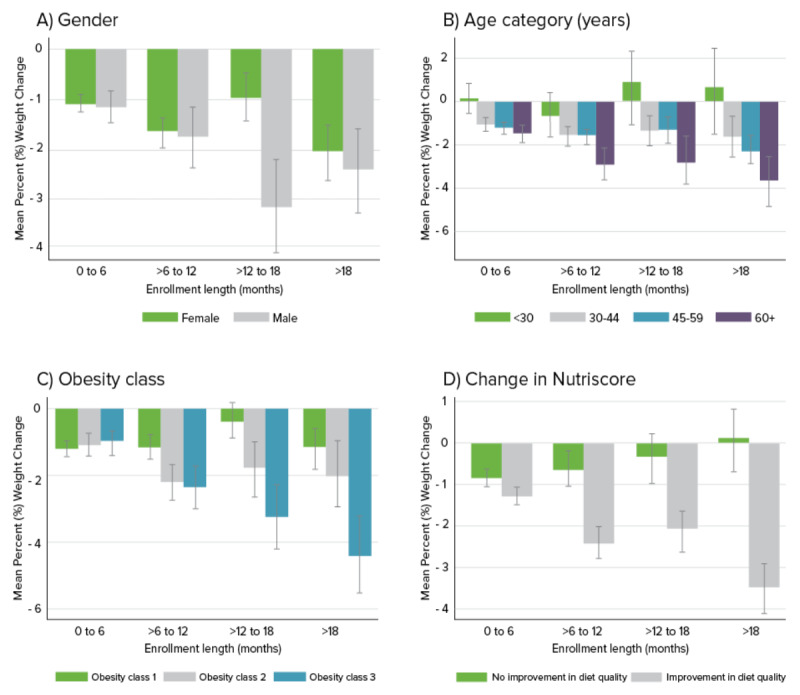

Figure 3A-D shows the mean percent weight change stratified by enrollment length category (less than 6 months, greater than 6 months to 12 months, greater than 12 months to 18 months, greater than 18 months) and by gender, age category, BMI category, and change in Healthy Diet Score (increase vs stayed the same or decrease).

Figure 3.

Mean (SD) percent weight change stratified by enrollment length and A) gender, B) age category, C) baseline obesity class, and D) change in Healthy Diet Score. Gray error bars indicate standard deviations of the mean; * indicates a statistically significant difference between groups assessed using ANOVA tests and a Bonferroni-corrected P value of .0031 to adjust for multiple comparisons.

While male users experienced, on average, greater weight loss compared to female users, the difference was much more pronounced among participants who were enrolled for 12-18 months. We also observed that when stratified by age, participants who were older experienced greater weight loss compared with those who were younger in a dose-response relationship. Participants in the highest age category of 60 and older lost the most weight, and this association became more robust with longer enrollment duration. Similarly, when stratified by baseline obesity class, participants who were in obesity class 3 had the largest improvements in weight, followed by obesity class 2 and then obesity class 1. The associations strengthened with enrollment duration. Participants who increased their Healthy Diet Score between their first and last reports of dietary intake experienced greater weight loss compared with participants whose Healthy Diet Score stayed the same or decreased.

Discussion

In the present study of 8977 Foodsmart platform users with obesity, we found that 59% of participants reported a decrease in weight, and 24% reported at least 5% weight loss of their initial weight while enrolled in the program; median (IQR) duration of follow-up was 9.9 months (0.03-54.7). Baseline BMI, baseline Healthy Diet Score, change in Healthy Diet Score, and longer duration of enrollment were all associated with higher odds of achieving 5% or greater weight loss. Age and gender were not associated with at least 5% weight loss. We found that the percentage of participants achieving 5% weight loss increased with enrollment duration. These findings suggest that Foodsmart platform users with obesity are likely to lose weight and that longer enrollment duration could potentially lead to greater weight loss. We believe these results to be clinically significant as 5% loss of initial weight has been linked to improved health outcomes among people who are obese, with prediabetes, or type 2 diabetes [9,12,29,30].

These results are in line with previous studies that found digital nutrition interventions to be successful in weight loss [31,32]. The majority of prior studies on digital apps has focused on nutrition monitoring and reporting or health coaching. However, the tools of the Foodsmart platform are unique in that, in addition to dietary recommendations, the app offers a personalized meal and recipe planning program and a unique food purchasing environment that addresses barriers to healthy eating by offering healthy options for everyone such as online ordering and delivery of groceries, meal kits, and prepared foods. Meal planning and cooking at home have been found to be associated with better diet quality and lower likelihood of obesity, primarily due to having control of ingredients, cooking methods, and portion sizes [22,23]. Although the use of commercial online grocery shopping, delivery, and meal kits has been increasing in recent years, few studies have examined the impact of these new purchasing behaviors on health outcomes. A study on medically tailored meal delivery for patients with diabetes and food insecurity found that home delivery of 10 meals per week for 12 weeks was associated with improvements in Healthy Eating Index Score, food insecurity, and hypoglycemia [33]. However, this was a short-term study with direct food provisions, which do not precisely mirror the Foodsmart platform. Nonetheless, the study suggests that healthy food delivery may be a viable strategy in improving health outcomes. More research is warranted to evaluate the potential cost savings of these types of programs that change the food purchasing environment to create healthier eating.

The finding that change in Healthy Diet Score was the strongest predictor of achieving 5% weight loss is noteworthy. The Healthy Diet Score captures overall dietary quality and serves as a proxy for engagement with the Foodsmart platform since the program is designed to improve diet quality. This demonstrates that participants who used the Foodsmart program and improved their diet quality were more likely to lose weight. Furthermore, the association between change in Healthy Diet Score and weight loss was compounded by duration of the program (Figure 3D). This finding is in agreement with previous studies that have found weight loss from mobile health apps to be greater with longer enrollment duration [34]. However, these findings showed that among people who used the program for over 12 months, 5% weight loss was achieved by one-third of users. Previous studies have shown that long-term maintenance of weight loss is challenging as more than half of lost weight was regained within 2 years [35,36]. Although this study was not designed to examine whether weight loss was sustained, we found that longer enrolment duration was associated with greater weight loss. Additional research is needed to further examine the sustainability of this type of intervention by examining trends of multiple weight measurements over time.

We found that despite more females using the program compared to males, that on average, male users lost more weight compared to females when stratified by enrollment length and gender (Figure 3A). However, in the fully adjusted logistic regression model, we did not find a statistically significant association between gender and 5% weight loss. While other studies have also found that males lost more weight compared to women when using health apps [34], the reason for the greater percent change could be higher baseline weight in male users. It was also interesting that when mean percent weight change was stratified by enrollment duration and age category, participants who were older consistently lost more weight, and the effect compounded with longer duration of enrollment. For participants under age 30, on average, weight increased if they enrolled for longer than 12 months. This finding was contrary to what some might expect given high rates of technology use by younger adults [37]. It may be that meal planning and food purchasing interventions may be more successful among older adults, or they may be more focused on their health. Or, this may be due to the increasing trend of eating out and less cooking, leading to weight gain, among younger populations [38,39]. Additionally, younger users may have been more likely to disengage with the app and then re-engage after gaining weight.

There are several limitations of the present study. Due to the observational nature of this study, we cannot conclude any causal associations between change in diet quality and weight loss. Since we did not have a control group, it is difficult to attribute a weight loss to the Foodsmart platform itself. This study serves as an exploration in which factors are associated with weight loss among Foodsmart users. Since we did not have exact dates for leaving the program, we used the last entry of weight as a proximal end date. Because we are using real-world data rather than the settings of a controlled study, participants were free to start and stop usage of the app as they wished. Therefore, it is challenging to draw firm conclusions on how duration of usage was associated with weight loss. Another limitation is that measures of height, weight, and diet were self-reported by participants. However, prior studies suggest that there is moderate to high agreement between online self-reported and measured anthropometric data [40]. Unfortunately, we did not have information on other factors that may be important predictors of weight loss such as total energy intake, race, or socioeconomic status. We did not assess engagement level or usage among participants since our goal was to examine the overall Foodsmart program. All users in this analysis took and retook the Nutriquiz and weight change assessments, which may, in and of themselves, have driven an impact due to their ability to motivate and drive self-insight and knowledge about nutrition and to track progress.

This study also had several strengths. With almost 9000 participants, this study included a large number of participants with obesity that provided us with sufficient power to examine percent weight change stratified by 2 variables. We also had a broad range of enrollment lengths, allowing us to examine weight change and maintenance in a time span of more than 2 years. Few studies, especially randomized clinical trials, on digital apps have follow-up data for weight change after more than 2 years.

In conclusion, this was one of the first studies of this scale and time length to examine weight loss among individuals with obesity who were users of a digital nutrition platform with personalized dietary recommendations and online meal planning, food ordering, grocery discounts, and incentives. Future studies are warranted to determine the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of weight loss through a digital nutrition intervention with these features vs other alternatives. Randomized clinical trials are needed to tease out causal associations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Christine Vaughan for performing initial analyses for this study. The study was funded by Foodsmart.

Abbreviations

- AHEI-2010

Alternative Healthy Eating Index-2010

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CSIRO

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization

- DPP

Diabetes Prevention Program

Appendix

Major changes to the Foodsmart platform since 2013.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: EAH analyzed data, interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript. VN acquired data. JL and DS interpreted results. All the authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and take responsibility for the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: EAH, VN, JL, and DS are employees of and own stocks of Zipongo, Inc DBA Foodsmart.

References

- 1.GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators. Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, Marczak L, Mokdad AH, Moradi-Lakeh M, Naghavi M, Salama JS, Vos T, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Ahmed MB, Al-Aly Z, Alkerwi A, Al-Raddadi R, Amare AT, Amberbir A, Amegah AK, Amini E, Amrock SM, Anjana RM, Ärnlöv J, Asayesh H, Banerjee A, Barac A, Baye E, Bennett DA, Beyene AS, Biadgilign S, Biryukov S, Bjertness E, Boneya DJ, Campos-Nonato I, Carrero JJ, Cecilio P, Cercy K, Ciobanu LG, Cornaby L, Damtew SA, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dharmaratne SD, Duncan BB, Eshrati B, Esteghamati A, Feigin VL, Fernandes JC, Fürst T, Gebrehiwot TT, Gold A, Gona PN, Goto A, Habtewold TD, Hadush KT, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hay SI, Horino M, Islami F, Kamal R, Kasaeian A, Katikireddi SV, Kengne AP, Kesavachandran CN, Khader YS, Khang Y, Khubchandani J, Kim D, Kim YJ, Kinfu Y, Kosen S, Ku T, Defo BK, Kumar GA, Larson HJ, Leinsalu M, Liang X, Lim SS, Liu P, Lopez AD, Lozano R, Majeed A, Malekzadeh R, Malta DC, Mazidi M, McAlinden C, McGarvey ST, Mengistu DT, Mensah GA, Mensink GBM, Mezgebe HB, Mirrakhimov EM, Mueller UO, Noubiap JJ, Obermeyer CM, Ogbo FA, Owolabi MO, Patton GC, Pourmalek F, Qorbani M, Rafay A, Rai RK, Ranabhat CL, Reinig N, Safiri S, Salomon JA, Sanabria JR, Santos IS, Sartorius B, Sawhney M, Schmidhuber J, Schutte AE, Schmidt MI, Sepanlou SG, Shamsizadeh M, Sheikhbahaei S, Shin M, Shiri R, Shiue I, Roba HS, Silva DAS, Silverberg JI, Singh JA, Stranges S, Swaminathan S, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Tadese F, Tedla BA, Tegegne BS, Terkawi AS, Thakur JS, Tonelli M, Topor-Madry R, Tyrovolas S, Ukwaja KN, Uthman OA, Vaezghasemi M, Vasankari T, Vlassov VV, Vollset SE, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Wesana J, Westerman R, Yano Y, Yonemoto N, Yonga G, Zaidi Z, Zenebe ZM, Zipkin B, Murray CJL. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N Engl J Med. 2017 Dec 06;377(1):13–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28604169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators. Forouzanfar Mohammad H, Alexander Lily, Anderson H Ross, Bachman Victoria F, Biryukov Stan, Brauer Michael, Burnett Richard, Casey Daniel, Coates Matthew M, Cohen Aaron, Delwiche Kristen, Estep Kara, Frostad Joseph J, Astha K C, Kyu Hmwe H, Moradi-Lakeh Maziar, Ng Marie, Slepak Erica Leigh, Thomas Bernadette A, Wagner Joseph, Aasvang Gunn Marit, Abbafati Cristiana, Abbasoglu Ozgoren Ayse, Abd-Allah Foad, Abera Semaw F, Aboyans Victor, Abraham JP, Abraham Jerry Puthenpurakal, Abubakar Ibrahim, Abu-Rmeileh Niveen M E, Aburto Tania C, Achoki Tom, Adelekan Ademola, Adofo Koranteng, Adou Arsène K, Adsuar José C, Afshin Ashkan, Agardh Emilie E, Al Khabouri Mazin J, Al Lami Faris H, Alam Sayed Saidul, Alasfoor Deena, Albittar Mohammed I, Alegretti Miguel A, Aleman Alicia V, Alemu Zewdie A, Alfonso-Cristancho Rafael, Alhabib Samia, Ali MK, Ali Mohammed K, Alla François, Allebeck Peter, Allen Peter J, Alsharif Ubai, Alvarez Elena, Alvis-Guzman Nelson, Amankwaa Adansi A, Amare Azmeraw T, Ameh Emmanuel A, Ameli Omid, Amini Heresh, Ammar Walid, Anderson Benjamin O, Antonio Carl Abelardo T, Anwari Palwasha, Argeseanu Cunningham Solveig, Arnlöv Johan, Arsenijevic Valentina S Arsic, Artaman Al, Asghar Rana J, Assadi Reza, Atkins Lydia S, Atkinson Charles, Avila Marco A, Awuah Baffour, Badawi Alaa, Bahit Maria C, Bakfalouni Talal, Balakrishnan Kalpana, Balalla Shivanthi, Balu Ravi Kumar, Banerjee Amitava, Barber Ryan M, Barker-Collo Suzanne L, Barquera Simon, Barregard Lars, Barrero Lope H, Barrientos-Gutierrez Tonatiuh, Basto-Abreu Ana C, Basu S, Basu Sanjay, Basulaiman Mohammed O, Batis Ruvalcaba Carolina, Beardsley Justin, Bedi Neeraj, Bekele Tolesa, Bell Michelle L, Benjet Corina, Bennett Derrick A, Benzian Habib, Bernabé Eduardo, Beyene Tariku J, Bhala Neeraj, Bhalla Ashish, Bhutta Zulfiqar A, Bikbov Boris, Bin Abdulhak Aref A, Blore Jed D, Blyth Fiona M, Bohensky Megan A, Bora Başara Berrak, Borges Guilherme, Bornstein Natan M, Bose Dipan, Boufous Soufiane, Bourne Rupert R, Brainin Michael, Brazinova Alexandra, Breitborde Nicholas J, Brenner Hermann, Briggs Adam D M, Broday David M, Brooks Peter M, Bruce Nigel G, Brugha Traolach S, Brunekreef Bert, Buchbinder Rachelle, Bui Linh N, Bukhman Gene, Bulloch Andrew G, Burch Michael, Burney Peter G J, Campos-Nonato Ismael R, Campuzano Julio C, Cantoral Alejandra J, Caravanos Jack, Cárdenas Rosario, Cardis Elisabeth, Carpenter David O, Caso Valeria, Castañeda-Orjuela Carlos A, Castro Ruben E, Catalá-López Ferrán, Cavalleri Fiorella, Çavlin Alanur, Chadha Vineet K, Chang Jung-Chen, Charlson Fiona J, Chen W, Chen Z, Chen Zhengming, Chiang Peggy P, Chimed-Ochir Odgerel, Chowdhury Rajiv, Christophi Costas A, Chuang Ting-Wu, Chugh Sumeet S, Cirillo Massimo, Claßen Thomas K D, Colistro Valentina, Colomar Mercedes, Colquhoun Samantha M, Contreras Alejandra G, Cooper Cyrus, Cooperrider Kimberly, Cooper Leslie T, Coresh Josef, Courville Karen J, Criqui Michael H, Cuevas-Nasu Lucia, Damsere-Derry James, Danawi Hadi, Dandona R, Dandona Rakhi, Dargan Paul I, Davis Adrian, Davitoiu Dragos V, Dayama Anand, de Castro E Filipa, De la Cruz-Góngora Vanessa, De Leo Diego, de Lima Graça, Degenhardt Louisa, del Pozo-Cruz Borja, Dellavalle Robert P, Deribe Kebede, Derrett Sarah, Des Jarlais Don C, Dessalegn Muluken, deVeber Gabrielle A, Devries Karen M, Dharmaratne Samath D, Dherani Mukesh K, Dicker Daniel, Ding Eric L, Dokova Klara, Dorsey E Ray, Driscoll Tim R, Duan Leilei, Durrani Adnan M, Ebel Beth E, Ellenbogen Richard G, Elshrek Yousef M, Endres Matthias, Ermakov Sergey P, Erskine Holly E, Eshrati Babak, Esteghamati Alireza, Fahimi Saman, Faraon Emerito Jose A, Farzadfar Farshad, Fay Derek F J, Feigin Valery L, Feigl Andrea B, Fereshtehnejad Seyed-Mohammad, Ferrari Alize J, Ferri Cleusa P, Flaxman Abraham D, Fleming Thomas D, Foigt Nataliya, Foreman Kyle J, Paleo Urbano Fra, Franklin Richard C, Gabbe Belinda, Gaffikin Lynne, Gakidou Emmanuela, Gamkrelidze Amiran, Gankpé Fortuné G, Gansevoort Ron T, García-Guerra Francisco A, Gasana Evariste, Geleijnse Johanna M, Gessner Bradford D, Gething Pete, Gibney Katherine B, Gillum Richard F, Ginawi Ibrahim A M, Giroud Maurice, Giussani Giorgia, Goenka Shifalika, Goginashvili Ketevan, Gomez Dantes Hector, Gona Philimon, Gonzalez de Cosio Teresita, González-Castell Dinorah, Gotay Carolyn C, Goto Atsushi, Gouda Hebe N, Guerrant Richard L, Gugnani Harish C, Guillemin Francis, Gunnell David, Gupta R, Gupta Rajeev, Gutiérrez Reyna A, Hafezi-Nejad Nima, Hagan Holly, Hagstromer Maria, Halasa Yara A, Hamadeh Randah R, Hammami Mouhanad, Hankey Graeme J, Hao Yuantao, Harb Hilda L, Haregu Tilahun Nigatu, Haro Josep Maria, Havmoeller Rasmus, Hay Simon I, Hedayati Mohammad T, Heredia-Pi Ileana B, Hernandez Lucia, Heuton Kyle R, Heydarpour Pouria, Hijar Martha, Hoek Hans W, Hoffman Howard J, Hornberger John C, Hosgood H Dean, Hoy Damian G, Hsairi Mohamed, Hu H, Hu Howard, Huang JJ, Huang John J, Hubbell Bryan J, Huiart Laetitia, Husseini Abdullatif, Iannarone Marissa L, Iburg Kim M, Idrisov Bulat T, Ikeda Nayu, Innos Kaire, Inoue Manami, Islami Farhad, Ismayilova Samaya, Jacobsen Kathryn H, Jansen Henrica A, Jarvis Deborah L, Jassal Simerjot K, Jauregui Alejandra, Jayaraman Sudha, Jeemon Panniyammakal, Jensen Paul N, Jha Vivekanand, Jiang G, Jiang Y, Jiang Ying, Jonas Jost B, Juel Knud, Kan Haidong, Kany Roseline Sidibe S, Karam Nadim E, Karch André, Karema Corine K, Karthikeyan Ganesan, Kaul Anil, Kawakami Norito, Kazi Dhruv S, Kemp Andrew H, Kengne Andre P, Keren Andre, Khader Yousef S, Khalifa Shams Eldin Ali Hassan, Khan Ejaz A, Khang Young-Ho, Khatibzadeh Shahab, Khonelidze Irma, Kieling Christian, Kim S, Kim Y, Kim Yunjin, Kimokoti Ruth W, Kinfu Yohannes, Kinge Jonas M, Kissela Brett M, Kivipelto Miia, Knibbs Luke D, Knudsen Ann Kristin, Kokubo Yoshihiro, Kose M Rifat, Kosen Soewarta, Kraemer Alexander, Kravchenko Michael, Krishnaswami Sanjay, Kromhout Hans, Ku Tiffany, Kuate Defo Barthelemy, Kucuk Bicer Burcu, Kuipers Ernst J, Kulkarni VS, Kulkarni Veena S, Kumar G Anil, Kwan Gene F, Lai Taavi, Lakshmana Balaji Arjun, Lalloo Ratilal, Lallukka Tea, Lam Hilton, Lan Qing, Lansingh Van C, Larson Heidi J, Larsson Anders, Laryea Dennis O, Lavados Pablo M, Lawrynowicz Alicia E, Leasher Janet L, Lee Jong-Tae, Leigh James, Leung Ricky, Levi Miriam, Li Y, Li Yongmei, Liang X, Liang Xiaofeng, Lim Stephen S, Lindsay M Patrice, Lipshultz Steven E, Liu Y, Liu Yang, Lloyd Belinda K, Logroscino Giancarlo, London Stephanie J, Lopez Nancy, Lortet-Tieulent Joannie, Lotufo Paulo A, Lozano Rafael, Lunevicius Raimundas, Ma S, Ma Stefan, Machado Vasco M P, MacIntyre Michael F, Magis-Rodriguez Carlos, Mahdi Abbas A, Majdan Marek, Malekzadeh Reza, Mangalam Srikanth, Mapoma Christopher C, Marape Marape, Marcenes Wagner, Margolis David J, Margono Christopher, Marks Guy B, Martin Randall V, Marzan Melvin B, Mashal Mohammad T, Masiye Felix, Mason-Jones Amanda J, Matsushita Kunihiro, Matzopoulos Richard, Mayosi Bongani M, Mazorodze Tasara T, McKay Abigail C, McKee Martin, McLain Abigail, Meaney Peter A, Medina Catalina, Mehndiratta Man Mohan, Mejia-Rodriguez Fabiola, Mekonnen Wubegzier, Melaku Yohannes A, Meltzer Michele, Memish Ziad A, Mendoza Walter, Mensah George A, Meretoja Atte, Mhimbira Francis Apolinary, Micha Renata, Miller Ted R, Mills Edward J, Misganaw Awoke, Mishra Santosh, Mohamed Ibrahim Norlinah, Mohammad Karzan A, Mokdad Ali H, Mola Glen L, Monasta Lorenzo, Montañez Hernandez Julio C, Montico Marcella, Moore Ami R, Morawska Lidia, Mori Rintaro, Moschandreas Joanna, Moturi Wilkister N, Mozaffarian Dariush, Mueller Ulrich O, Mukaigawara Mitsuru, Mullany Erin C, Murthy Kinnari S, Naghavi Mohsen, Nahas Ziad, Naheed Aliya, Naidoo Kovin S, Naldi Luigi, Nand Devina, Nangia Vinay, Narayan K M Venkat, Nash Denis, Neal Bruce, Nejjari Chakib, Neupane Sudan P, Newton Charles R, Ngalesoni Frida N, Ngirabega Jean de Dieu, Nguyen NT, Nguyen Nhung T, Nieuwenhuijsen Mark J, Nisar Muhammad I, Nogueira José R, Nolla Joan M, Nolte Sandra, Norheim Ole F, Norman Rosana E, Norrving Bo, Nyakarahuka Luke, Oh In-Hwan, Ohkubo Takayoshi, Olusanya Bolajoko O, Omer Saad B, Opio John Nelson, Orozco Ricardo, Pagcatipunan Rodolfo S, Pain Amanda W, Pandian Jeyaraj D, Panelo Carlo Irwin A, Papachristou Christina, Park Eun-Kee, Parry Charles D, Paternina Caicedo Angel J, Patten Scott B, Paul Vinod K, Pavlin Boris I, Pearce Neil. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity and Severe Obesity Prevalence in US Youth and Adults by Sex and Age, 2007-2008 to 2015-2016. JAMA. 2018 Apr 24;319(16):1723–1725. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3060. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29570750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seidell JC, Halberstadt J. The global burden of obesity and the challenges of prevention. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66 Suppl 2:7–12. doi: 10.1159/000375143. https://www.karger.com?DOI=10.1159/000375143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kopelman P G. Obesity as a medical problem. Nature. 2000 Apr 06;404(6778):635–43. doi: 10.1038/35007508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet. 2011 Aug 27;378(9793):815–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60814-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston BC, Kanters S, Bandayrel K, Wu P, Naji F, Siemieniuk RA, Ball GDC, Busse JW, Thorlund K, Guyatt G, Jansen JP, Mills EJ. Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014 Sep 03;312(9):923–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kouvelioti R, Vagenas G, Langley-Evans S. Effects of exercise and diet on weight loss maintenance in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2014 Aug;54(4):456–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM, Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002 Feb 07;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/11832527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, Vetter ML, Tsai AG, Berkowitz RI, Kumanyika S, Schmitz KH, Diewald LK, Barg R, Chittams J, Moore RH. A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med. 2011 Nov 24;365(21):1969–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109220. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22082239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodpaster BH, Delany JP, Otto AD, Kuller L, Vockley J, South-Paul JE, Thomas SB, Brown J, McTigue K, Hames KC, Lang W, Jakicic JM. Effects of diet and physical activity interventions on weight loss and cardiometabolic risk factors in severely obese adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010 Oct 27;304(16):1795–802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1505. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20935337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, Safford M, Knowler WC, Bertoni AG, Hill JO, Brancati FL, Peters A, Wagenknecht L, Look ARG. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011 Jul;34(7):1481–6. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2415. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21593294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacLean PS, Wing RR, Davidson T, Epstein L, Goodpaster B, Hall KD, Levin BE, Perri MG, Rolls BJ, Rosenbaum M, Rothman AJ, Ryan D. NIH working group report: Innovative research to improve maintenance of weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015 Jan;23(1):7–15. doi: 10.1002/oby.20967. doi: 10.1002/oby.20967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhee E. Weight Cycling and Its Cardiometabolic Impact. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2017 Dec 30;26(4):237–242. doi: 10.7570/jomes.2017.26.4.237. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31089525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azar KMJ, Lesser LI, Laing BY, Stephens J, Aurora MS, Burke LE, Palaniappan LP. Mobile applications for weight management: theory-based content analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2013 Nov;45(5):583–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franco RZ, Fallaize R, Lovegrove JA, Hwang F. Popular Nutrition-Related Mobile Apps: A Feature Assessment. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016 Aug 01;4(3):e85. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5846. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2016/3/e85/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burke LE, Styn MA, Sereika SM, Conroy MB, Ye L, Glanz K, Sevick MA, Ewing LJ. Using mHealth technology to enhance self-monitoring for weight loss: a randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012 Jul;43(1):20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.03.016. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22704741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kankanhalli A, Shin J, Oh H. Mobile-Based Interventions for Dietary Behavior Change and Health Outcomes: Scoping Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019 Jan 21;7(1):e11312. doi: 10.2196/11312. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2019/1/e11312/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin CK, Miller AC, Thomas DM, Champagne CM, Han H, Church T. Efficacy of SmartLoss, a smartphone-based weight loss intervention: results from a randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015 May;23(5):935–42. doi: 10.1002/oby.21063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Block G, Azar KM, Romanelli RJ, Block TJ, Hopkins D, Carpenter HA, Dolginsky MS, Hudes ML, Palaniappan LP, Block CH. Diabetes Prevention and Weight Loss with a Fully Automated Behavioral Intervention by Email, Web, and Mobile Phone: A Randomized Controlled Trial Among Persons with Prediabetes. J Med Internet Res. 2015 Oct 23;17(10):e240. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4897. http://www.jmir.org/2015/10/e240/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirwan M, Vandelanotte C, Fenning A, Duncan MJ. Diabetes self-management smartphone application for adults with type 1 diabetes: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(11):e235. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2588. http://www.jmir.org/2013/11/e235/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monsivais P, Aggarwal A, Drewnowski A. Time spent on home food preparation and indicators of healthy eating. Am J Prev Med. 2014 Dec;47(6):796–802. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.033. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0749-3797(14)00400-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ducrot P, Méjean C, Aroumougame V, Ibanez G, Allès B, Kesse-Guyot E, Hercberg S, Péneau S. Meal planning is associated with food variety, diet quality and body weight status in a large sample of French adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017 Feb 02;14(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0461-7. https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-017-0461-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983 Jun;51(3):390–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008 May;27(3):379–87. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, McIntosh A, Rosenfeld S. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires : the Eating at America's Table Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Dec 15;154(12):1089–99. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, Hu FB, McCullough ML, Wang M, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr. 2012 Jun;142(6):1009–18. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.157222. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22513989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendrie GA, Baird D, Golley RK, Noakes M. The CSIRO Healthy Diet Score: An Online Survey to Estimate Compliance with the Australian Dietary Guidelines. Nutrients. 2017 Jan 09;9(1):47. doi: 10.3390/nu9010047. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=nu9010047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douketis JD, Macie C, Thabane L, Williamson DF. Systematic review of long-term weight loss studies in obese adults: clinical significance and applicability to clinical practice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005 Oct;29(10):1153–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blackburn G. Effect of degree of weight loss on health benefits. Obes Res. 1995 Sep;3 Suppl 2:211s–216s. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00466.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1071-7323&date=1995&volume=3&issue=&spage=211s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel ML, Hopkins CM, Brooks TL, Bennett GG. Comparing Self-Monitoring Strategies for Weight Loss in a Smartphone App: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019 Feb 28;7(2):e12209. doi: 10.2196/12209. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2019/2/e12209/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Senecal C, Collazo-Clavell M, Larrabee BR, de Andrade M, Lin W, Chen B, Lerman LO, Lerman A, Lopez-Jimenez F. A digital health weight-loss intervention in severe obesity. Digit Health. 2020;6:2055207620910279. doi: 10.1177/2055207620910279. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2055207620910279?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berkowitz SA, Delahanty LM, Terranova J, Steiner B, Ruazol MP, Singh R, Shahid NN, Wexler DJ. Medically Tailored Meal Delivery for Diabetes Patients with Food Insecurity: a Randomized Cross-over Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Mar;34(3):396–404. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4716-z. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30421335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chin SO, Keum C, Woo J, Park J, Choi HJ, Woo J, Rhee SY. Successful weight reduction and maintenance by using a smartphone application in those with overweight and obesity. Sci Rep. 2016 Nov 07;6:34563. doi: 10.1038/srep34563. doi: 10.1038/srep34563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001 Nov;74(5):579–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall KD, Kahan S. Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018 Jan;102(1):183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.012. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29156185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Vaart R, van Driel D, Pronk K, Paulussen S, Te Boekhorst S, Rosmalen JGM, Evers AWM. The Role of Age, Education, and Digital Health Literacy in the Usability of Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Form Res. 2019 Nov 21;3(4):e12883. doi: 10.2196/12883. https://formative.jmir.org/2019/4/e12883/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartmann C, Dohle S, Siegrist M. Importance of cooking skills for balanced food choices. Appetite. 2013 Jun;65:125–31. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larson NI, Perry CL, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Food preparation by young adults is associated with better diet quality. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006 Dec;106(12):2001–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pursey K, Burrows TL, Stanwell P, Collins CE. How accurate is web-based self-reported height, weight, and body mass index in young adults? J Med Internet Res. 2014 Jan 07;16(1):e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2909. https://www.jmir.org/2014/1/e4/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Major changes to the Foodsmart platform since 2013.