Abstract

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has highlighted the importance of reducing occupational exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The reprocessing procedure for reusable flexible bronchoscopes (RFBs) involves multiple episodes of handling of equipment that has been used during an aerosol-generating procedure and thus is a potential source of transmission. Single-use flexible bronchoscopes (SUFBs) eliminate this source. Additionally, RFBs pose a risk of nosocomial infection transmission between patients with the identification of human proteins, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and pathogenic organisms on fully reprocessed bronchoscopes despite full adherence to the guidelines. Bronchoscopy units have been hugely impacted by the pandemic with restructuring of pre- and post-operative areas, altered patient protocols and the reassessment of air exchange and cleaning procedures. SUFBs can be incorporated into these protocols as a means of improving occupational safety. Most studies on the efficacy of SUFBs have occurred in an anaesthetic setting so it remains to be seen whether they will perform to an acceptable standard in complex respiratory procedures such as transbronchial biopsies and cryotherapy. Here, we outline their potential uses in a respiratory setting, both during and after the current pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Disposable bronchoscope, Single-use flexible bronchoscope, Pandemic, SARS-CoV-2

Key Summary Points

| Bronchoscopy is an aerosol-generating procedure and associated with a high risk of viral transmission during the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Single-use flexible bronchoscopes (SUFBs) can reduce the number of healthcare personnel exposed to SARS-CoV-2 |

| SUFBs have many advantages over their reusable counterparts |

| Most of the studies on SUFB efficacy and cost-effectiveness have been in an anaesthetic setting |

| We outline the benefits of SUFBs during the COVID-19 pandemic and provide a rationale for their more frequent use in the pulmonology suite |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.12905990.

Introduction

The development of reusable flexible bronchoscopes (RFBs) in 1968 was a ground-breaking development in diagnostic and therapeutic bronchoscopy. Common indications include diagnostic washings, endobronchial biopsy and brushings and transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA). Many therapeutic procedures are now possible with both rigid and flexible bronchoscopy including foreign body removal and tumour debulking while recent advances include asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) therapies. By comparison, in the intensive care unit (ICU) their uses include the confirmation of endotracheal tube positioning in difficult airways as well as diagnostic sampling.

Bronchoscopy poses challenges from the perspective of infection prevention with a risk of transmission to both the patient and the personnel involved [1–5]. Patient infections can arise exogenously as a result of contaminated equipment [1] and, while the majority of outbreaks of pseudo and actual infection have been linked to breaches in bronchoscope reprocessing guidelines, a recent study demonstrated that even with complete adherence to protocol, contamination and microbial growth persisted on fully reprocessed RFBs [5]. The main risk for the personnel involved is the transmission of acute respiratory infection (ARI) via aerosols generated during the procedure [2, 6]. Currently, the risk of transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) to both patients and healthcare personnel (HCP) is of huge concern [7] and there is evidence of transmission of the virus in healthcare settings [8]. Bronchoscopy should be avoided in people with confirmed or suspected coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [3, 9, 10]; however, if essential, several organisations recommend avoiding RFBs to reduce the risk of viral transmission [11].

Until now, disposable or single-use flexible bronchoscopes (SUFBs) have primarily been used by anaesthetists in an ICU or peri-operative setting where they perform to an acceptable level in comparison to RFBs [12, 13] combined with the distinct advantage of a reduced risk of infection owing to their sterility [14]. Several studies have assessed their cost compared to RFBs [14, 15] and a recent review that incorporated the cost of treating the exogenous infections that might be caused by RFBs found that SUFBs were significantly more cost-effective [16].

In this review, the risk of infection with standard RFBs will be outlined as will the advantages of SUFBs, with comment on their cost profile compared to RFBs and attempt to suggest a rationale for their use during the COVID-19 pandemic and in a respiratory setting. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Standard review article methodology was used. Search terms including ‘reusable bronchoscope’, ‘single-use bronchoscope’, ‘disposable bronchoscope AND covid-19 pandemic’ were placed in Pubmed, Google and Embase search engines and the resulting English language papers that were available were read. Additionally, the references of all these papers were read and any citations deemed appropriate were also sought and read and their references were reviewed.

Reprocessing of Reusable Flexible Bronchoscopes

Bronchoscopy is a semi-critical procedure (Spaulding classification)—there is a moderate risk of infection as the bronchoscope is in contact with mucous membranes but does not enter sterile tissues or the vasculature. Devices in this category warrant high level disinfection (HLD) [4]. When a bronchoscope is used for a procedure that breaches the mucosa, it is recommended that the accessory that breaches the mucosa is either single-use or undergoes sterilisation. HLD involves the elimination of all bacteria, viruses and fungi with the exception of some bacterial spores which are only removed with sterilisation [1].

Reprocessing aims to stop the transmission of exogenous infection to the patient. Outbreaks of bacterial infection associated with RFBs have primarily occurred in the setting of breaches in the reprocessing protocols whilst pseudo infection (cultural evidence of transmission of organisms without evidence of patient infection) has also occurred [1]. The transmission of viral respiratory pathogens via RFBs has not been reported to date.

The major recommendations from the various guidelines [4, 17, 18] regarding the appropriate reprocessing of RFBs are the same. Mechanical cleaning is performed as soon as the procedure is finished with leak testing to assess the integrity of the scope coupled with brushing (ideally with single-use brushes) and flushing. The RFB then undergoes HLD—previously a manual process [4]; however, use of an automated endoscope reprocessor (AER) is now preferred [17]. Bronchoscopes must be stored in a hanging position in a cabinet with appropriate aeration and with adequate space between them to prevent cross-contamination [4]. Staff should receive training and wear personal protective equipment (PPE) while reprocessing the bronchoscopes [17]. If PPE is not used, staff are at an increased risk of infection and may recontaminate fully processed scopes [5]. In some institutions, RFBs are cleaned and then sterilised [15]; however, the chemicals used—either ethylene oxide or hydrogen peroxide—are expensive and interfere with the mechanical properties of flexible bronchoscopes [1].

Certain infectious agents are unusually resistant to standard methods of disinfection, sterilisation and UV radiation e.g. the prions that cause the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs). If a patient undergoing bronchoscopy has a suspected diagnosis of a TSE, the RFB should be incinerated after use; or if there is an expectation of repeat bronchoscopy in the same patient, the RFB should be set apart for use in that patient only [19, 20].

Risk of Infection with Standard Bronchoscopy

A recent study over three different clinical sites inspected RFBs and measured levels of protein, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and infectious organisms both before and after manual cleaning and HLD [5]. At all sites, the patient-ready bronchoscopes had visible defects (100%) and harboured antimicrobial growth (58%). At two of the sites, the reprocessing was inadequate as a result of multiple episodes of non-compliance with the guidelines e.g. disabling of the cycles of the AER, ungloved handling of bronchoscopes and dirty storage cabinets. However, even at the third site where the reprocessing procedures met national guidelines, there was still an unacceptably high level of bio-burden on reprocessed bronchoscopes leading to the conclusion that a movement towards sterilisation of RFBs might be warranted [5], though this has its own disadvantages as outlined earlier.

In 2019, ECRI highlighted the recontamination of flexible endoscopes due to mishandling or improper storage as one of the top ten health technology hazards. They referred particularly to the recontamination of disinfected endoscopes caused by failure of staff to change their gloves between inserting and removing the endoscope from the AER [21].

Assuming that there is no risk of exogenous infection with a SUFB, a systematic review in 2019 used avoidance of this risk as an effect measure while trying to elucidate the true cost of RFBs when cross-contamination and infection are taken into consideration. The 16 studies eligible for inclusion in the analysis involved flexible bronchoscopy performed in both ICU and respiratory units. The results revealed an overall 2.8% infection risk to the patient which considerably decreased the cost-effectiveness of RFBs compared to SUFBs [16].

SUFBs are not designed to withstand the standard reprocessing of RFBs. It has been shown that following basic cleaning of a SUFB, there was significant microbial colonisation of the devices at 48 h including high-risk pathogens for causing pneumonia. This study confirms that SUFBs are only appropriate for single use as opposed to single patient use [22].

Risk of Infection with Reusable Flexible Bronchoscopes in the COVID Era

A recent morbidity and mortality report from the USA showed that HCP represented 11% of the population infected with SARS-CoV-2 and the majority (55%) of this group only had exposure to an infected person within a healthcare setting [8]. Occupational status as HCP was only specified in 16% of all submissions so it is likely that their actual infection rates were significantly underestimated. In those HCP on whom outcomes were available, 8–10% required hospitalisation and 0.3–0.6% died from the infection, highlighting the significant risks associated with the occupation [8].

Transmission of the virus occurs via droplets and fomites. Droplets are respiratory aerosols that are larger than 5 µm in diameter while fomites are inanimate objects that can transmit disease if they are contaminated with an infectious agent. Bronchoscopy is considered an aerosol-generating procedure (AGP) [3]. Thus, there is a risk of viral transmission both from the aerosols generated during the bronchoscopy and again during staff reprocessing of contaminated bronchoscopes. As a result, bronchoscopy is relatively contraindicated in patients who are suspected of or confirmed with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a bid to reduce disease transmission and protect HCP [3, 9]. Despite this, a balance must be achieved to ensure that patients who need urgent therapeutic and diagnostic interventions are not neglected.

In situations where bronchoscopy is essential, for instance a suspicion of malignancy in a patient fit for cancer therapy, any day-case bronchoscopy should be delayed by 28 days following confirmed or suspected diagnosis of COVID-19 and if proceeding thereafter, only essential personnel should be present with all staff wearing PPE and avoidance of high flow nasal oxygen [9]. The American Association of Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology (AABIP) has gone as far as to recommend avoiding the use of RFBs in this situation and using SUFBs instead [11] with some institutes having already adopted SUFBs as a result [23].

Exhaled air from a human patient simulator (HPS) receiving 3–5 L/min of oxygen via nasal cannula in a negative pressure room can travel as far as 100 cm. Coughing can cause air dispersal to 68 cm which is reduced to 30 cm with donning of a surgical mask by the HPS. Thus, it is advised that all patients with COVID-19 wear surgical masks to reduce transmission. Additionally, when using a nasal approach during bronchoscopy, the patient’s mouth should be covered by a mask and if they require non-invasive ventilation (NIV), it should be administered through a hole in the patient’s mask [2]. The construction of a surgical tent with disposable drapes may improve the safety of HCP during the procedure [24], although any barrier method needs research to evaluate whether it might reduce COVID-19 transmission whilst increasing the transmission of other hospital-acquired infections.

Similar principles apply in unavoidable surgical procedures in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients that require a general anaesthetic—single-use equipment is recommended where possible e.g. a SUFB could be used to ensure the correct positioning of an endotracheal tube [25].

A systematic review completed in 2012 compared the risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections (ARIs) to HCP involved in AGPs. The ten studies that met the inclusion criteria all pertained to transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) during the outbreak of 2002/2003 and the AGPs included tracheal intubation, bronchoscopy and NIV. The data was only slightly significant for tracheal intubation increasing the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV and there was insufficient data to come to any conclusion about bronchoscopy. Unfortunately, the included studies were categorised as providing very low-quality evidence; however, the review did emphasise the importance of using appropriate PPE during AGPs [6].

Another study in Singapore General Hospital during the SARS-CoV outbreak noted the high risk of transmission to anaesthetists particularly during intubation and bronchoscopy. Following the implementation of stringent infection control measures including single-use devices where possible and appropriate use of PPE, they successfully reduced transmission to HCP even when patients presented asymptomatically or with atypical infections [26].

Therefore, evidence supports the introduction of SUFBs to decrease viral transmission both from and to staff and patients. Furthermore, eliminating the requirement for reprocessing can help to counteract a reduction in staff numbers due to local outbreaks [27].

Types of Single-Use Flexible Bronchoscopes

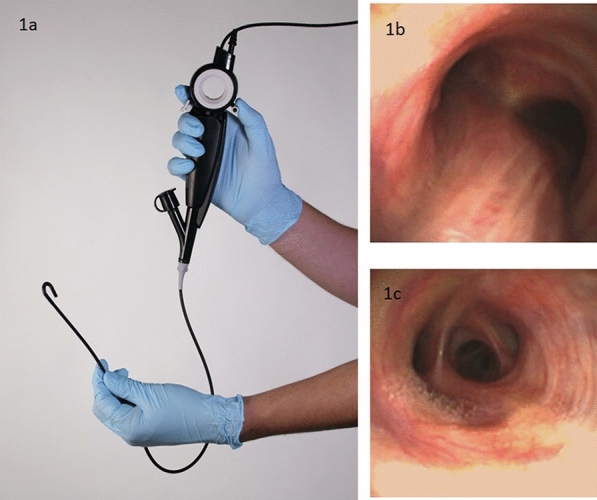

Several companies produce single-use bronchoscopes with some of them currently on fourth-generation devices that have improved image quality and degrees of angulation (Fig. 1). The range of devices includes a selection of channel diameters (Table 1). Each company has produced a small portable reusable screen that is easy to clean and from which videos or images can easily be saved or downloaded.

Fig. 1.

Use of a single-use flexible bronchoscope to perform an airway inspection in a 64-year-old woman with chronic cough. a The SUFB used—Broncoflex®Agilea; Endobronchial images: b The carina. c The trifurcation of the right middle lobe (RML), right lower lobe (RLL) (RB7−10) and the superior segment of the RLL (RB6). aReproduced with permission (Axess Vision)

Table 1.

Characteristics of currently available single-use flexible bronchoscopes

| Single-use flexible bronchoscopes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Company | Vathin Medical | Axess Vision | Ambu |

| Type | Videoscope | Videoscope | Videoscope |

| Trade name | H-Steriscope™ | Broncoflex® | Ambu®aScope™4 |

| Outer diameter (mm) | 2.2, 3.2, 4.9, 5.8, 6.2 | 3.9 (Agile) (Fig. 1), 5.6 (Vortex) | 3.8 (slim), 5.0 (regular), 5.8 (large) |

| Inner diameter (mm) | 0, 1.2, 2.2, 2.8, 3.2 | 1.4 (Agile), 2.8 (Vortex) | 1.2 (slim), 2.2 (regular), 2.8 (large) |

| Working length (mm) | 600 | 605 | 600 |

| Tip deflection up/downward | 210°/210° |

220°/220° (Agile) 200°/200° (Vortex) |

180°/180° (slim) 180°/180° (regular) 180°/160° (large) |

Advantages of Single-Use Flexible Bronchoscopes Over Reusable Flexible Bronchoscopes (Table 2)

Table 2.

Clinical scenarios where single-use flexible bronchoscopes have advantages

| Advantages of single-use flexible bronchoscopes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ease of mobility | Practicality | Specific scenarios where reduced risk of cross infection is critical* | Other applications |

| Bronchoscopy in ICU | Out of hours bronchoscopy | Immunocompromised patient | Bronchoscopy training |

| Bronchoscopy in emergency department/ward | End of day list—staff are not required to stay and clean scopes | Prion disease | Veterinary procedures |

| Emergency bronchoscopy outside healthcare facility | Weekend bronchoscopy where staff are not available to clean scopes | Large animal or cadaveric research | |

| Bronchoscope available for airway inspection with EBUS procedures | |||

*Risk of cross-infection is hypothesised higher in reusable flexible bronchoscopy than single-use bronchoscopy; however, these are scenarios with significant advantages for single-use bronchoscopes

EBUS endobronchial ultrasound

As SUFBs do not require any reprocessing after use, the risk of transmission of infectious particles to HCP is reduced by minimising exposure to fomites or aerosols. The portable screens are also easy to clean and a less complex circuit allows for easier tracing of any potential contaminants [14].

The ability of trainees to learn is limited while current recommendations advise that only essential personnel are allowed into the room during bronchoscopy [2, 9, 24, 25]; however, the video function on SUFBs allows you to easily record and store images which can be used to demonstrate clinical anatomy and pathology [14] from a remote location where social distancing can easily be observed. They are also useful as general teaching aids such as simulation training with mannequins which has been shown to reduce the amount of subsequent damage to RFBs [28, 29]. SUFBS clearly have advantages in centres performing bench, cadaveric or large animal research, reducing cost of equipment, cleaning costs and storage. SUFBs may also be of use in training and research in the veterinary field where bronchoscopy is performed for a variety of indications [30, 31].

The other major advantage for SUFBs is the option for parallel as opposed to linear use in the respiratory suite which can decrease delays between procedures and increase the number of bronchoscopies that can be performed. Their immediate availability and the possibility of out-of-hours use is also a distinct advantage in the anaesthetic setting for the unanticipated difficult airway [13, 32]. In the immunocompromised patient and in rare cases of prion contamination due to TSE, they offer a safer alternative to RFBs.

Evidence of Efficacy of Single-Use Flexible Bronchoscopes

SUFBs have been shown to be acceptable compared to RFBs in an anaesthetic setting [12, 13] and for performing bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in healthy volunteers for research purposes [33] (Table 3), though some users comment that image technology and handling is not yet equivalent to RFBs [34].

Table 3.

Evidence of efficacy of single-use flexible bronchoscopes

| Setting | Elective surgery | ENT surgery | Sample collection for research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | Ambu®aScope™2 vs Karl Storz fibrescope | Ambu®aScope vs conventional videoscope | Ambu®aScope vs conventional scope |

| Intervention | Orotracheal intubation in anaesthetised patients | Tracheal intubation in awake patients | BAL collection for research purposes in healthy volunteers |

| Nature of study |

60 patients randomised to either group Operators familiar with both devices |

Pilot study in 20 anaesthetised patients with normal airways Random assignment to either group of 40 awake patients with predicted difficult airways |

SUFB used for RML BAL in 10 volunteers vs BAL with conventional scope in 50 volunteers |

| Outcome | No difference in GRS between devices | Clinically acceptable—two instances of blurred image after lidocaine injection—new SUFBs deployed |

Greater sample volumes in SUFB group No difference in cell yield or viability |

| Reference | [12] | [13] | [33] |

GRS Global Rating Scale (a validated score for benchmarking operators who perform clinical bronchoscopy), BAL bronchoalveolar lavage, RML right middle lobe

The studies of the efficacy of SUFBs to date have compared them to RFBs in an anaesthetic setting only, with no studies analysing their efficacy in a clinical pulmonology setting. In anaesthetics where bronchoscopes are often used in emergency situations such as management of the unanticipated difficult airway [32], it is essential that they are fit for purpose.

The demonstration that SUFBs are adequate in performing BAL for research [33] suggests that they are also likely to be acceptable for diagnostic purposes in a clinical respiratory setting. An increased yield with BAL using SUFBs [33] has the potential to reduce post-procedural side effects and, if this finding is reproducible, could make them the preferred choice over RFBs.

Cost of Single-Use Flexible Bronchoscopes

During the COVID-19 pandemic the cost of healthcare services and management of resources will ultimately affect patient outcomes. One might anticipate that SUFBs will be more expensive than RFBs; however, in addition to the initial cost of the RFB, a significant amount of resources are required for the appropriate training of personnel, provision of designated cleaning areas, PPE, maintenance of the AER as well as supply of disinfectants, enzyme reagents and detergents [1]. The limited number of studies in this area (none conducted solely in a bronchoscopy unit) have demonstrated that SUFBs can be as cost-effective as RFBs in a variety of situations (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cost-effectiveness of single-use flexible bronchoscopes

| Setting | Fibre optic intubation in the operating theatre & emergency department | Tracheal intubation & double-lumen tube position verification peri-operatively | BAL & percutaneous tracheostomy in the ICU of a university hospital | Reprocessing of an RFB vs SUFB use in a university hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature of study | Retrospective study of cost of RFBs (with eyepieces) for fibre-optic intubations with comparison to SUFB costs | Micro-costing analysis for RFBs with comparison to SUFB costs | Compare cost of RFBs & SUFBs in BAL & percutaneous tracheostomy | Comparison of the environmental impact of Ambu®Scope™4 to that of RFB |

| Detail |

Allowed for initial outlay, storage & cleaning (sterilisation) costs Delays between procedures decreased the cost-effectiveness of RFBs |

Incorporated cost of treating a 2.8% infection risk Assumed no infection risk with SUFBs as no reports of same to date High ratio of repairs per use (18:1) |

Decontamination procedures done manually (no AER) Included cost of RFB purchase, tax write-off, insurance policy, repairs & decontamination Vs cost of purchase, decontamination & waste management of SUFBs |

Simplified life cycle assessment with comparison of CO2-equivalent emissions & resource consumption consumables to produce the RFB & cost of screen for SUFB not incorporated Incineration as disposal method for SUFB |

| Conclusion | At a procedure frequency of up to 200 fibre-optic intubations a year, it was more useful to use SUFBs | SUFBs more cost-effective owing to elimination of infection risk |

Cost of RFBs varied greatly depending on procedure performed & number of interventions per year Cost of SUFB is comparable to cost of RFB |

Nil conclusion could be drawn about which had the greatest environmental impact Amount of PPE changes during reprocessing could sway the balance of impact |

| Reference | [15] | [16] | [35] | [37] |

Local factors such as initial purchase price, service agreements and reprocessing protocols influence the cost-effectiveness of RFBs—repair costs can vary significantly between different hospitals which will alter the cost per use [15, 16]. Additionally, different procedures require higher maintenance or are associated with greater damage to bronchoscopes e.g. more write-offs when performing percutaneous tracheostomy compared to BAL [35]. There is a procedure number at which RFBs become more cost-effective than SUFBs [15, 35] with mathematical modelling tools available to assess the cost-effective number of RFBs or SUFBs that should be purchased whilst allowing for locally variable factors. When device demand is incorporated into these algorithms, there is a suggestion that units performing a smaller number of interventions could manage solely with SUFBs whilst RFBs become more economical with increased demand [36] and it is likely to be cost-effective to have a subset of SUFBs available for emergency use [16, 36]. To date, no studies have been published looking at the cost-effectiveness of SUFBs in a respiratory setting, and the costs associated with RFB maintenance and repair in an anaesthesia department may not be comparable.

Prior to the recommendation to introduce SUFBs into bronchoscopy units, it would be important to optimise the current costs associated with maintenance and repairs of RFBs. It has been shown that as much as 50.9% of the cost of bronchoscope repair can be attributed to preventable damage e.g. unsheathing a biopsy needle within a working channel [38], and the introduction of educational programmes which focus on the cost of RFB repairs as well as emphasising safety regulations and procedure could drop the repair cost as much as 84% per procedure [28]. Quality improvement campaigns are similarly useful in reducing the incidence of scope damage and decreasing episodes of RFB unavailability [29]. Purchasing an insurance policy for an RFB is another way of reducing the cost of repairs [35].

In developing countries, adherence to bronchoscopy guidelines may impose prohibitively expensive costs on the development of high-quality flexible bronchoscopy units e.g. because of the recommendation for AERs to reprocess RFBs [39]. Depending on the anticipated number of procedures SUFBs may be a solution to this problem.

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, SUFBs have the potential to create a safer working environment in situations where AGPs such as bronchoscopy or intubation are unavoidable. Prior to introduction of SUFBs under normal circumstances, it would be necessary to assess their use and cost-effectiveness in a respiratory setting. In the interim, there are many strategies that can be employed to improve the cost-effectiveness of RFBs. It is likely that in the future, mathematical modelling tools will be used to guide procurement decisions for single-use and reusable bronchoscopes depending on local maintenance agreements, the number of procedures performed and SUFBs would be purchased to make up the capacity shortage until the demand reaches a level that makes further purchase of reusable devices more cost-effective.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Sarah P Barron and Marcus P Kennedy have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Footnotes

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.12905990.

References

- 1.Kovaleva J, Peters F, van der Mei HC, Degener JE. Transmission of infection by flexible gastrointestinal endoscopy and bronchoscopy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(2):231–254. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00085-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferioli M, Cisternino C, Leo V, Pisani L, Palange P, Nava S. Protecting healthcare workers from SARS-CoV-2 infection: practical indications. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29(155):2000068. 10.1183/16000617.0068-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Lentz RJ, Colt H. Summarizing societal guidelines regarding bronchoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Respirology. 2020;25(6): 574–77. 10.1111/resp.13824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Mehta AC, Prakash UBS, Garland R, et al. American College of Chest Physicians and American Association for Bronchoscopy consensus statement: prevention of flexible bronchoscopy-associated infection. Chest. 2005;128(3):1742–1755. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ofstead CL, Quick MR, Wetzler HP, et al. Effectiveness of reprocessing for flexible bronchoscopes and endobronchial ultrasound bronchoscopes. Chest. 2018;154(5):1024–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa-Silva CL, Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lancet. COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395(10228):922. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Burrer SL, de Perio MA, Hughes MM, et al. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19—United States, February 12-April 9, 2020. Morbidity Mortality Wkly Rep. 2020:477–81. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Baldwin D, Lim W, Rintoul R, et al. Bronchoscopy services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br Thorac Soc. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/quality-improvement/covid-19/bronchoscopy-services-during-the-covid-pandemic/

- 10.Irish Thoracic Society. Irish Thoracic Society statement on bronchoscopy and SARS COVID-19. Statement. Ir Thorac Soc. https://irishthoracicsociety.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/ITS-Bronchoscopy-STatement-24.03-Final.pdf

- 11.Wahidi MM, Lamb C, Murgu S. American Association for Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology (AABIP) statement on the use of bronchoscopy and respiratory specimen collection in patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7141581/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Chan JK, Ng I, Ang JP, et al. Randomised controlled trial comparing the Ambu® aScope™2 with a conventional fibreoptic bronchoscope in orotracheal intubation of anaesthetised adult patients. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2015;43(4):479–484. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1504300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristensen MS, Fredensborg BB. The disposable Ambu aScope vs. a conventional flexible videoscope for awake intubation—a randomised study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57:888–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Châteauvieux C, Farah L, Guérot E, et al. Single-use flexible bronchoscopes compared with reusable bronchoscopes: positive organizational impact but a costly solution. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;9(24):528–535. doi: 10.1111/jep.12904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCahon RA, Whynes DK. Cost comparison of re-usable and single-use fibrescopes in a large English teaching hospital. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(6):699–706. doi: 10.1111/anae.13011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mouritsen JM, Ehlers L, Kovaleva J, Ahmad I, El-Boghdadly K. A systematic review and cost effectiveness analysis of reusable vs. single-use flexible bronchoscopes. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(4):529–540. doi: 10.1111/anae.14891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du Rand IA, Blaikley J, Booton R, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy in adults. Thorax. 2013;16(68):i1–i44. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.HSE National Decontamination of Reusable Invasive Medical Devices Advisory Group. Health Service Executive Standards and recommended practices for endoscope reprocessing units. Health Technical Memorandum. Nenagh, Co. Tipperary, Ireland: HSE, National Quality and Patient Safety Directorate; 2012. Report No.: QPSD-D-005-2.2.

- 19.NHS. Management and decontamination of flexible endoscopes. Health Technical Memorandum. National Health Service; 2013 March 20. Report No.: HTM01-06.

- 20.Spongiform Encephalopathy Advisory Committee. Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy agents: safe working and the prevention of infection. 1998.

- 21.ECRI . Top 10 health technology hazards. Executive brief. Pennsylvania: ECRI Institute, Health devices; 2019. p. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGrath BA, Ruane S, McKenna J, Thomas S. Contamination of single-use bronchoscopes in critically ill patients. Anaesthesia. 2017;72(1):36–41. doi: 10.1111/anae.13622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honore PM, Mugisha A, Kugener L, et al. With the current COVID-19 pandemic: should we use single-use flexible bronchoscopes instead of conventional bronchoscopes? Crit Care. 2020;18:24 (234). 10.1186/s13054-020-02965-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Francom CR, Javia LR, Wolter NE, et al. Pediatric laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic: a four-center collaborative protocol to improve safety with perioperative management strategies and creation of a surgical tent with disposable drapes. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;134(110059). 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Coccolini F, Perrone G, Chiarugi M, et al. Surgery in COVID-19 patients: operational directives. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15(25). 10.1186/s13017-020-00307-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Tan TK. How severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) affected the department of anaesthesia at Singapore General Hospital. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2004;32(3):394–400. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0403200316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barron S, Kennedy M. Single use bronchoscopes: applications in COVID-19 pandemic. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2020. https://journals.lww.com/bronchology/Citation/9000/Single_Use_Bronchoscopes__Applications_in_COVID_19.99773.aspx [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Lunn W, Garland R, Gryniuk L, Smith L, Feller-Kopman D, Ernst A. Reducing maintenance and repair costs in an interventional pulmonology program. Chest. 2005;127(4):1382–1387. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.4.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu HF, Hung KC, Chiang MH, et al. Implementation of an anaesthesia quality improvement programme to reduce fibreoptic bronchoscope repair incidents. Biomed Res Int. 2020;21:2020. doi: 10.1155/2020/1091239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finke MD. Transtracheal wash and bronchoalveolar lavage. Top Companion Anim Med. 2013;28(3):97–102. doi: 10.1053/j.tcam.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanthorn CJ, Dewell RD, Cooper VL, et al. Randomized clinical trial to evaluate the pathogenicity of Bibersteinia trehalosi in respiratory disease among calves. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:89. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-10-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frerk C, Mitchell VS, Mcnarry AF, et al. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(6):827–848. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaidi SR, Collins AM, Mitsi E, et al. Single use and conventional bronchoscopes for broncho alveolar lavage (BAL) in research: a comparative study (NCT 02515591). BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(83). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Shulimzon T, Chatterji S, Gan R. Infections and damaged flexible bronchoscopes—time for a change. Chest. 2018;155(6):1299. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perbet S, Blanquet M, Mourgues C, et al. Cost analysis of (Ambu®aScope™) and reusable bronchoscopes in the ICU. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7(3):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0228-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edenharter GM, Gartner D, Pförringer D. Decision support for the capacity management of bronchoscopy devices: optimizing the cost-efficient mix of reusable and single-use devices through mathematical modeling. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(6):1963–1967. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sørensen BL, Grüttner H. Comparative study on environmental impacts of reusable and single-use bronchoscopes. Am J Environ Prot. 2018;7(4):55–62. doi: 10.11648/j.ajep.20180704.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rozman A, Duh S, Petrinec-Primozic M, Triller N. Flexible bronchoscope damage and repair costs in a bronchoscopy teaching unit. Respiration. 2009;77(3):325–330. doi: 10.1159/000188788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veaudor M, Couraud S, Chan S, et al. Implementing flexible bronchoscopy in least developed countries according to international guidelines is feasible and sustainable: example from Phnom-Penh, Cambodia. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.