Abstract

Amazonian waters are classified into three biogeochemical categories by dissolved nutrient content, sediment type, transparency, and acidity—all important predictors of autochthonous and allochthonous primary production (PP): (1) nutrient-poor, low-sediment, high-transparency, humic-stained, acidic blackwaters; (2) nutrient-poor, low-sediment, high-transparency, neutral clearwaters; (3) nutrient-rich, low-transparency, alluvial sediment-laden, neutral whitewaters. The classification, first proposed by Alfred Russel Wallace in 1853, is well supported but its effects on fish are poorly understood. To investigate how Amazonian fish community composition and species richness are influenced by water type, we conducted quantitative year-round sampling of floodplain lake and river-margin habitats at a locality where all three water types co-occur. We sampled 22,398 fish from 310 species. Community composition was influenced more by water type than habitat. Whitewater communities were distinct from those of blackwaters and clearwaters, with community structure correlated strongly to conductivity and turbidity. Mean per-sampling event species richness and biomass were significantly higher in nutrient-rich whitewater floodplain lakes than in oligotrophic blackwater and clearwater river-floodplain systems and light-limited whitewater rivers. Our study provides novel insights into the influences of biogeochemical water type and ecosystem productivity on Earth’s most diverse aquatic vertebrate fauna and highlights the importance of including multiple water types in conservation planning.

Subject terms: Ecology, Community ecology, Freshwater ecology, Tropical ecology, Wetlands ecology

Introduction

The Amazon basin contains the most diverse riverine vertebrate assemblage on Earth, with ca. 2,800 species (7.8% of planetary fish diversity1) distributed across multiple sub-basins and aquatic habitat types2–4. Efforts to understand the diversity and distribution of Amazonian fish have focused on paleogeographic and paleoclimatic events5, species-area effects6,7, river continuum effects7,8, habitat specialization2,9, ecomorphological, physiological, and sensory specializations10–12, biotic interactions13, and neutral processes14. Nonetheless, our understanding of how fish assemblages are structured by variation in basic physico-chemical water properties is surprisingly incomplete.

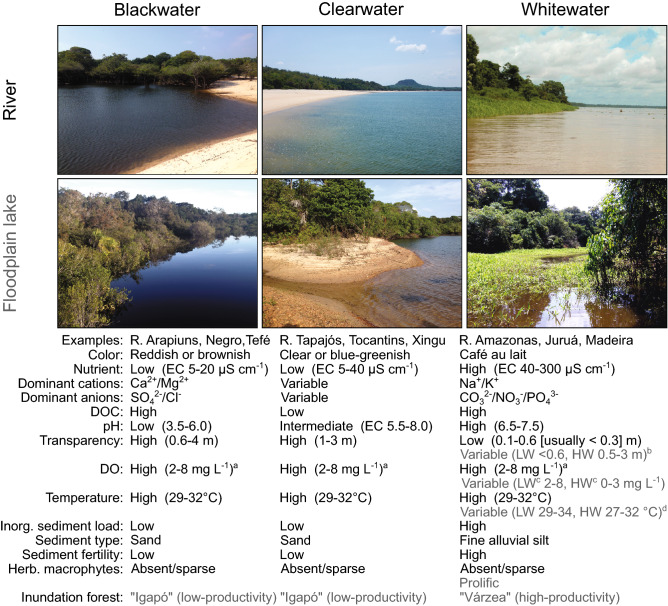

Amazonian waters are classified into three distinct biogeochemical categories (Fig. 1) by a combination of dissolved nutrient content, sediment type, transparency, and acidity—all important determinants of autochthonous and allochthonous primary productivity (PP): (1) nutrient-poor, low-sediment, high-transparency (but humic-stained), and acidic blackwaters originating from deeply weathered soils overlying lowland tropical forests and savannas of the Amazon’s intracratonic basin or shield fringes15–19; (2) nutrient-poor, low-sediment, high-transparency, and neutral clearwaters originating from upland shield formations dominated by non-biogenous Precambrian rocks15,17–19; (3) nutrient-rich, low-transparency, neutral whitewaters, with high loads of fertile alluvial suspended sediment. Whitewaters originate from contemporary or historical Andean headwaters15,17–19 and derive their high sediment load and high concentration of dissolved nutrients (that is, the dissolved ions that limit autotrophic production, e.g. calcium, magnesium, nitrate, phosphate) from the erosion of biogenous sediments of marine provenance20–24. In contrast, the highly weathered soils and dense vegetation of Amazonian blackwaters and clearwater drainages lead to low sediment load and low dissolved nutrient content16,17,19,21,22 (conductivity ca. 5–40 μS cm−1, versus ca. 40–300 [usually > 60] μS cm−1 for whitewaters).

Figure 1.

The Wallace classification of Amazonian rivers, with typical ranges of physico-chemical properties. Values for floodplain lakes (gray text) are given only where they typically differ from parent rivers. Ranges follow Junk et al.17, Crampton2 and Appendix S4 online. EC conductivity, DOC dissolved organic carbon, LW/HW low/high water, DO dissolved oxygen, Inorg. Inorganic, Herb. herbaceous. aPeriodic phytoplankton (including cyanobacteria) blooms induce DO supersaturation (ca. 8–15 mg L−1) and tint clearwater green. bPrecipitation of suspended silt due to reduced flow in WW floodplain lakes substantially increases transparency relative to parent WW river. cHW hypoxia results from litter decomposition in inundation forests; this effect is greater in large WW floodplains. dShallow WW lakes reach extreme high LW temperature. Photographs are of the R. Arapiuns (blackwater), Tapajós (clearwater) and Amazonas (whitewater) near Santarém, Brazil.

The three water types were first described by Alfred Russel Wallace25 in one of the earliest scientific accounts of Amazônia and their biogeochemical bases were later elucidated by geochemical and limnological studies18,21,26,27. Wallace’s classification remains in use and is congruent with modern river classifications based on synthetic aperture radar imaging28. Nonetheless, the effects of biogeochemical water type on Amazonian fish assemblages remain poorly documented. For instance, our understanding of disparities in fish assemblage structure between water types is mostly based on comparisons of sites separated by hundreds or thousands of kilometers, where the influence of water type is confounded by geographical variation in species distributions. In contrast, few studies have compared assemblage structure between water types located in close geographical proximity. These include comparisons of black- versus whitewater by Galacatos et al.29, Henderson and Crampton30, and Saint-Paul et al.31, and black- versus clearwater by Winemiller et al.32; these studies described distinctive communities of species associated with each water type. However, a simultaneous comparison of the fish faunas of adjacent or nearby black-, clear- and whitewater systems has yet to be undertaken to unravel how biogeochemical disparities influence community composition.

The effects of dissolved nutrient content, sediment type, transparency, and acidity on the autochthonous and allochthonous PP of Amazonian aquatic habitats have been well studied. Three main patterns emerge: (1) Phytoplankton and algal periphyton PP is high in sediment-decanted nutrient-rich whitewater floodplain lakes27,33–39, lower in oligotrophic (nutrient-limited) blackwater and clearwater rivers and floodplains16,21,27,34,35,39–41 (especially low in blackwaters with extreme low pH42), and negligible in whitewater river channels, where photosynthesis is light-limited by the high suspended sediment load20,27,43,44. Second, extensive stands of grass-dominated herbaceous macrophytes45–48 and associated algal epiphyton49 develop in whitewater lakes. These grasses have a free-floating high-water stage dependent on the high dissolved nutrient content of whitewaters, but also a rooted low-water stage dependent on the high fertility of the alluvial deposits of whitewaters47. In contrast herbaceous macrophytes are generally absent (or very sparse) in black- and clearwater floodplains due to the low dissolved nutrient content and infertile sand-based lake sediments22,50. Herbaceous macrophytes growth is also minimal in whitewater rivers (despite high nutrient availability) due to the strong currents. Third, high-productivity ‘várzea’ inundation forests and grasslands, with associated high allochthonous inputs (e.g. seeds and arthropods51), develop on the fertile alluvial floodplain deposits surrounding whitewater floodplain lakes17,51–57. In contrast low-productivity, often stunted, ‘igapó’ inundation forests develop on clear- and blackwater floodplains17,52–57.

Species-energy relationships predict higher fish diversity in systems with higher total PP58,59, which would suggest that whitewater floodplains (but not necessarily light-limited whitewater rivers) might support higher species richness than blackwater and clearwater rivers and floodplains. Our current understanding of aquatic species-energy relationships in the Amazon has been greatly influenced by Goulding et al.’s16 book ‘Rio Negro: Rich life in poor water’, which introduced the notion that highly oligotrophic waters can support paradoxically high fish species diversity – mirroring patterns in coral reefs60. The authors proposed that high diversity can occurs despite low autochthonous PP because the energy sustaining fish communities derives primarily from allochthonous inputs from seasonally flooded forests. Nonetheless, only two quantitative comparisons of fish species richness between Amazon water types are available. Saint-Paul et al.31 described higher diversity in the blackwater R. Negro than the mainstem whitewater R. Amazonas, but Henderson and Crampton30 reported a contrary pattern of higher diversity in the R. Amazonas than the blackwater R. Tefé.

To assess the influence of water type on Amazonian fishes we conducted a year-round quantitative sampling program of river margin and floodplain habitats in one of the few areas of Amazônia where all three biogeochemical water types occur in close proximity (near Santarém, Brazil, Fig. 2). Based on the results of this sampling program we discuss the role of water type and habitat in shaping fish assemblage structure, species richness, and biomass. Our analyses also address whether habitats known to exhibit both high autochthonous and allochthonous PP (i.e. whitewater lakes) exhibit higher species richness (and/or biomass) than those known to exhibit low autochthonous PP and relatively reduced allochthonous inputs (i.e. floodplain lakes and main river channels of blackwater and clearwater systems, and nutrient-rich but light-limited whitewater river channels).

Figure 2.

Map of the study area near Santarém, Brazil, with locations of the three sampled water types (blackwater BW, clearwater CW, whitewater WW) and two sampled habitat types (river margin R, floodplain lake F). Solid lines represent boundaries of seasonal floodplains. Arrows indicate river flow. Dark green line in inset map of South America demarcates Amazon river drainage. Sampling was conducted through a full annual hydrological cycle, every two months, at two site replicates (labeled 1 and 2) representing each of the six combinations of water type and habitat type. This yielded a planned total of 72 sample events, one of which was missed due to bad weather, leaving 71. Base map from MFF-maps (https://maps-for-free.com) modified with Inkscape version 0.92 (www.inkscape.org).

Results

Physico-chemical parameters

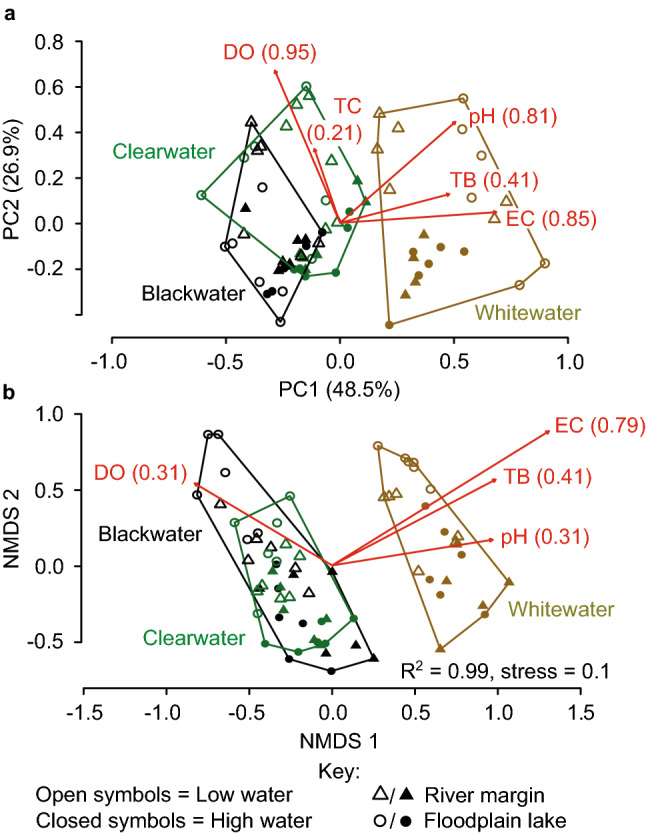

Our measurements of physico-chemical parameters in the blackwater (BW) R. Arapiuns, clearwater (CW) R. Tapajós, and whitewater (WW) R. Amazonas (Supplementary Table S1 online) were within the typical ranges summarized in Fig. 1 for BW, CW and WW rivers. All pairwise combinations of the three water types differed significantly in physico-chemical properties; permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA): BW-CW, (pseudo) F = 7.2, R = 0.73, P < 0.001; BW-WW, F = 67.9, R = 0.77 P < 0.001; CW-WW, F = 42.0, R = 0.69, P < 0.001; global, F = 38.4, R = 0.73, P < 0.001 (Supplementary Table S2 online for differences subdivided by habitat type, i.e. floodplain lake, river margin, all were significant at α = 0.001). In a principal components analysis (PCA) ordination (Fig. 3a), sampling events formed two non-overlapping groups—one represented by BW and CW, and another by WW. Sampling events for BW and CW overlapped at low water and high water. We observed no segregation of the BW and CW sampling events at 3rd or higher PCA axes. The environmental vectors for turbidity, conductivity, and pH increased in the order BW–CW–WW.

Figure 3.

Multivariate analyses of physico-chemical water properties and fish assemblage structure in the study area. (a) Principal component analysis of physico-chemical properties measured at 71 sampling events through a complete annual hydrological cycle. (b) Nonmetric multidimensional scaling ordination based on fish assemblage structure at the same 71 sampling events. Red arrows represent environmental vectors significant at α = 0.05, with R2 values. DO dissolved oxygen, EC conductivity, TB turbidity, TC temperature.

Habitat structure, vegetation, and area

Substrate and vegetation types were typical for Amazon black-, clear-, and whitewater rivers-floodplain systems (Fig. 1). Herbaceous macrophytes were restricted to the whitewater floodplain and comprised dense stands of Echinochloa polystachya and other grasses with a marginal rooted low-water stage and floating high-water stage, as well as some other macrophytes, e.g. Eichhornia spp. In a rectangular cross-river transect of 10 km width at the R2 sites (including both banks and intervening islands), we measured the WW floodplain area as ca. 140 km2 per 10 km river length, 35–47 times the area of BW (4 km2) and CW floodplains (3 km2), respectively.

Fish community composition

We collected 22,398 fish from 310 species, 172 genera, 44 families, and 15 orders (Supplementary Tables S3, Appendix S1 online). 89% of species were identified as valid described species, 6% as undescribed species (listed ‘sp.’), and 5% were assigned ‘conferre’ (cf.) to described species in need of taxonomic revision.

Species richness

WW habitats exhibited higher total species richness than BW and CW habitats (Table 1, Fig. 4a). With the removal of rare species (those with < 4 individuals), WW floodplain still exhibited the highest species richness, but river habitats exhibited similar richness (tied in WW and BW, slightly lower in CW, Table 1). The percentage of rare species in WW rivers greatly exceeded that of other water/habitat type combinations (Table 1). Rarefaction curves (Fig. 4a) reached asymptotes for all water type/habitat combinations, except for WW rivers for which species richness may be underestimated (but nonetheless exceeded that of CW and BW rivers). Rarified species richness estimates were invariably highest in WW and mostly lowest in BW, both for floodplain and river sites, despite low abundance in WW rivers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary results for fish species richness, biomass, and abundance in the study area, including common indices of richness, effective species number, diversity, and evenness. Means refer to mean per sample event.

| Habitat type | Water type | Total species richness | Mean species richness | Species richness minus rare species | % rare | Rarefied species richness | Chao1 estimated species richness | Jost diversity | Simpson diversity | Pielou evenness | Total Biomass (kg) | Mean Biomass (kg) | Total Abundance (n fish) | Mean abundance (n fish) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| River margin | Blackwater | 91 | 20.6 | 75 | 21.3 | 62.2 | 122.6 | 17.7 | 0.88 | 0.64 | 45.8 | 3.81 | 4,098 | 223.3 |

| Clearwater | 96 | 17.5 | 71 | 35.2 | 77.7 | 121.4 | 21.4 | 0.88 | 0.67 | 31.3 | 2.61 | 1,739 | 144.9 | |

| Whitewater | 130 | 19.5 | 75 | 73.3 | 130.0 | 181.3 | 53.6 | 0.97 | 0.82 | 35.0 | 3.17 | 911 | 38.2 | |

| Total | 207 | 112.0 | 6,748 | |||||||||||

| Floodplain lake | Blackwater | 84 | 16.3 | 61 | 37.7 | 84.0 | 105.1 | 25.6 | 0.93 | 0.73 | 28.0 | 1.97 | 2,519 | 209.9 |

| Clearwater | 112 | 21.2 | 87 | 28.7 | 97.8 | 135.6 | 20.4 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 54.2 | 2.36 | 4,166 | 97.4 | |

| Whitewater | 172 | 43.9 | 117 | 47.0 | 123.9 | 194.9 | 33.8 | 0.94 | 0.68 | 136.5 | 11.38 | 8,965 | 533.8 | |

| Total | 255 | 218.8 | 15,650 | |||||||||||

| River margin & Floodplain lake | Blackwater | 128 | 28.75 | 105 | 21.9 | 124.6 | 186.1 | 30.1 | 0.93 | 0.70 | 73.8 | 4.80 | 6,617 | 328.3 |

| Clearwater | 149 | 28.10 | 122 | 22.1 | 149.0 | 190.0 | 29.3 | 0.93 | 0.68 | 85.6 | 3.79 | 5,905 | 193.6 | |

| Whitewater | 224 | 41.45 | 163 | 37.4 | 199.6 | 253.6 | 44.1 | 0.95 | 0.70 | 171.50 | 8.86 | 9,876 | 305.1 | |

| Total | 310 | 330.8 | 22,398 |

The highest values for each habitat type are reported in bold for emphasis (tied highest values in bold and italics).

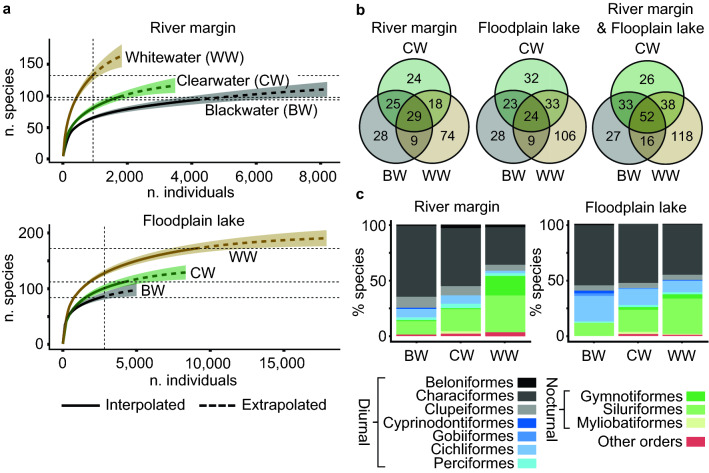

Figure 4.

Patterns of fish species richness and taxonomic composition among the three water types and two habitat types of the study area. (a) Rarefaction curves; see Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5 online for similar patterns in rarefaction curves divided by site replicate and by gear type, respectively. (b) Species occupancy Venn diagrams per habitat type, reporting number of exclusive and shared species; see Supplementary Fig. S6 online for similar patterns in Venn Diagrams restricted to single site replicates. (c) Habitat specialization (% species occurrences per habitat type); Other Orders are Osteoglossiformes, Tetraodontiformes, Pleuronectiformes, Synbranchiformes, and Ceratodontiformes. Orders are assigned to predominantly diurnal or nocturnal activity following the literature cited in Supplementary Appendix S5 online.

Biomass and abundance

Total biomass and abundance in floodplains substantially exceeded that of rivers (Table 1). For floodplains, both total biomass and total abundance were higher in WW than in BW and CW. However, in rivers, the highest biomass and abundance was observed in BW. The total abundance of river fish was largely decoupled from total biomass due to variation in average fish weight: in BWs (0.011 kg), CW (0.017 kg), and WW (0.038 kg).

Assemblage structure

The proportion of species exclusive to WW exceeded that of BW and CW. This pattern occurred in rivers, floodplains, and both habitats pooled (Fig. 4b). In both river and floodplain habitats, the predominantly diurnally-active Characiformes, Clupeiformes, Cichliformes, and Perciformes decreased in species richness in the order BW–CW–WW, while the nocturnally active Siluriformes and Gymnotiformes exhibited an opposite pattern (Fig. 4c). Siluriformes and Gymnotiformes were especially abundant in the whitewater river samples.

Assemblage structure differed significantly for all pairwise combinations of water type by PERMANOVA, with BW and CW exhibiting the greatest similarity (lowest R); BW-CW, (pseudo) F = 3.8, R = 0.27, P < 0.001; BW-WW, F = 8.5, R = 0.4, P < 0.001; CW-WW, F = 42.0, R = 9.8, P < 0.001; global, F = 7.4, R = 0.41, P < 0.001. Supplementary Table S4 online reports disparities subdivided by habitat type (all significant at α = 0.001).

About half the variation in assemblage structure was attributable to variation in physico-chemical parameters; co-inertia analysis (COIA) RV value = 0.46, P < 0.001, null model 95% CIs 0.125–0.134. In an analysis presented in Supplementary Appendix S2 online we confirmed that the relationship between assemblage structure and physico-chemical parameters had negligible spatial dependence (was unaffected by hydrological distances among pairs of sites).

Like in the PCA of physico-chemical properties (Fig. 3a), an ordination of assemblage structure by nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) (Fig. 3b) revealed two non-overlapping groups: one corresponding to WW habitats, and another to BW and CW habitats. For all three water types, floodplain and river sampling events overlapped considerably in the NMDS ordination of assemblage structure, indicating that community composition is more strongly affected by water type than by habitat structure (Fig. 3b). The environmental vectors for turbidity, conductivity, and pH loaded positively in a direction from the BW + CW group to the WW group, with conductivity and turbidity exhibiting the strongest correlation with assemblage structure. Similar outcomes occurred if rare species were removed (Supplementary Fig. S1, online), demonstrating that rare species have little influence on variation in assemblage structure. Similar outcomes also occurred in separate ordinations for the two utilized gear types (gill nets and seine nets) (Supplementary Fig. S2, online)—confirming that our analyses of community composition were not biased by gear type, as well as in separate ordinations for site replicates 1 and 2 (Supplementary Fig. S3, online)—confirming that none of our site replicate pairs had major discrepancies in species composition.

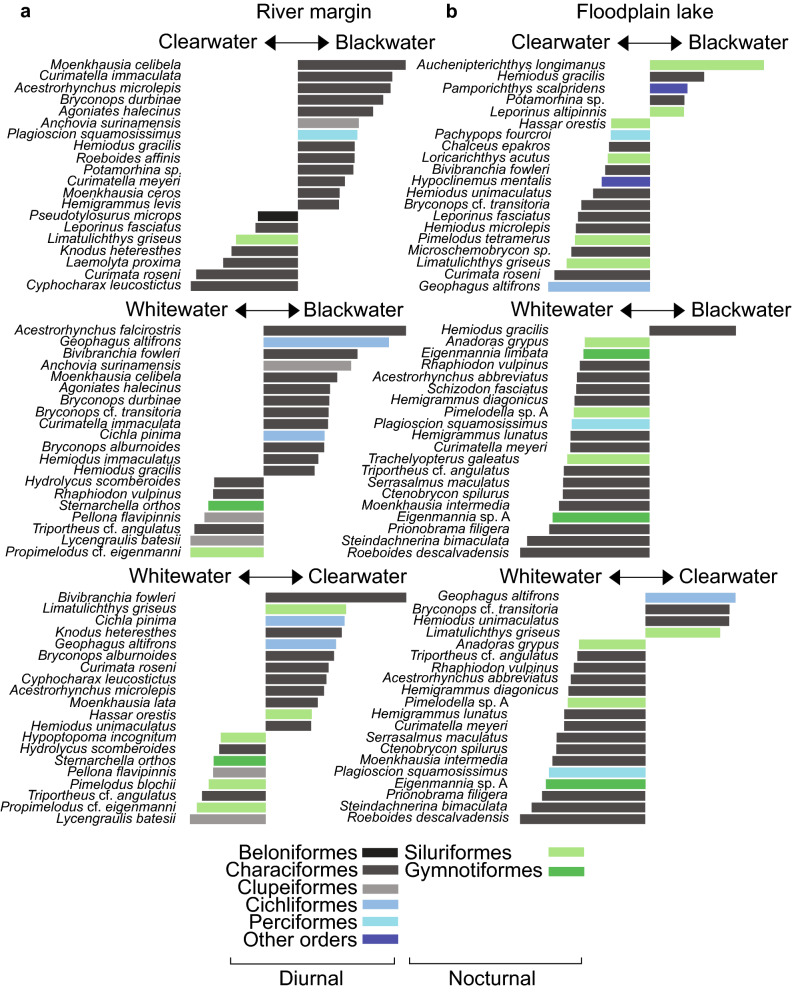

Species diagnostic of WW (especially rivers) comprised a mixture of diurnally active groups and nocturnally active Siluriformes and Gymnotiformes (Fig. 5). In contrast, species exerting the strongest influence on differences in assemblage structure between BW and CW belonged to the predominantly diurnal orders Clupeiformes, Characiformes, and Cichliformes.

Figure 5.

Contributions of the 20 most influential species to the differences in assemblage structure between water types, based on PERMANOVA coefficients. Length of bars represent the magnitude of contribution to difference between each pairwise combination of water type.

Quantitative comparisons of species richness, biomass, and abundance

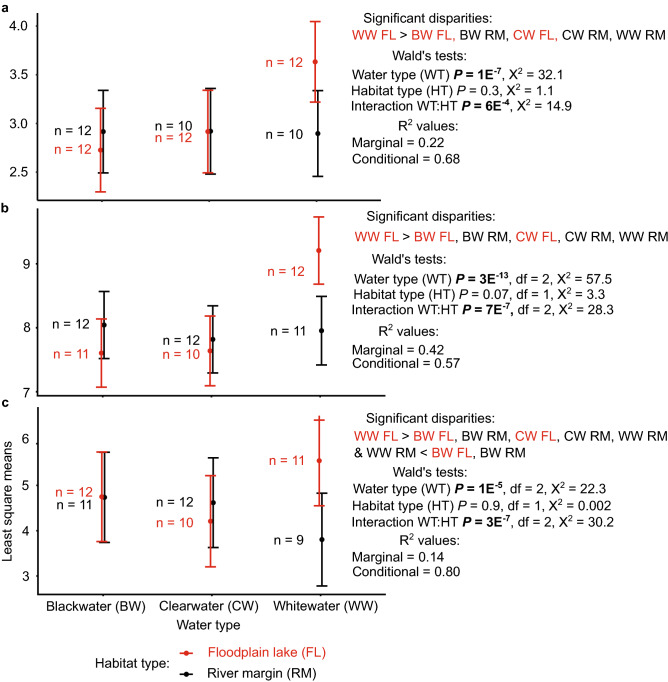

Generalized linear mixed-effect models (GLMMs) showed that WW floodplain lakes significantly exceeded all other water/habitat type combinations for mean (per-sampling event) species richness (Fig. 6a), biomass (Fig. 6b), and abundance (Fig. 6c). Species richness: Mean WW floodplain species richness exceeded that of BW and CW floodplains 2.7-fold and 2.1-fold, respectively, and exceeded that of all river margin sites (2.1–2.5-fold). In river margins, we observed no significant differences in species richness among water types, although the highest values were reported for BW. Biomass: Mean WW floodplain biomass exceeded that of BW and CW floodplains 4.9-fold and 2.5-fold, respectively, and exceeded that of all river margin sites (3.0–4.3-fold) (Table 1). Abundance: Finally, mean WW floodplain abundance exceeded that of BW and CW floodplains 2.5-fold and 5.4-fold, respectively, and exceeded that of all river margin sites (2.3–14.0-fold). Mean BW river abundance exceeded that of WW rivers 5.8-fold (although this disparity was lost in most of the repeat analyses reported in Table S3), but abundance in CW did not differ significantly from BW or WW. Due to lower average fish weight in BW than WW river habitats (see above), the difference in mean abundance between BW and WW rivers (5.8-fold) was larger than the difference in mean biomass (1.3-fold).

Figure 6.

Generalized linear mixed-effect models for the effects of water type and habitat type on: (a) species richness, (b) biomass, and (c) abundance. Plots show least square means for the fixed effects (water type, habitat) with 95% confidence intervals. Disparities are reported where significant at α = 0.05 by Tukey post-hoc test (see Supplementary Table S5 online for model details). Sample sizes (n) refer to sampling events. Here outlier sampling events (reported in Supplementary Fig. S7 online) were excluded, hence variation in sample sizes between models.

The significant differences reported in Fig. 6 are robust because they were also recovered in: (1) GLMMs for richness, biomass, and abundance in which outlier sampling events were included; (2) GLMMs for biomass excluding large-sized fish (defined as those > 3 standard deviations above the mean mass of all sampled fish); (3) GLMMs for abundance and richness excluding rare species (defined as those represented by < 4 individuals in all samples combined), dominant species (defined as the top 10% most numerically-abundant species in all samples combined), and both rare and dominant species (see Supplementary Table S5 online). In only one case (GLMM for abundance, with outliers included) were WW floodplain lakes no longer significantly greater than all other water/habitat type combinations.

Discussion

Our results avoid confounding variation associated with geographical variation in species distributions to conclude that fish communities in whitewater systems are distinct from those in blackwater and clearwater systems. Assemblage structure is correlated most strongly to turbidity and conductivity, and to a lesser degree to pH. We propose that variation in species composition between the three biogeochemical water types arises, in part, because each water type contains sets of species adapted to characteristic ranges of physico-chemical conditions, habitat structure and floodplain vegetation type. Amazonian fishes are known to exhibit a tremendous diversity of physiological, morphological, and sensory adaptations to water chemistry—including for hypoxia tolerance61,62, ion regulation under conditions of varying pH and ion concentration63,64, vision, phototransduction, and visual signaling under varying optical conditions12,65, and, in the case of Gymnotiformes, electrolocation and electrocommunication in waters of varying conductivity66. Gradients of water type are therefore expected to act as filters to dispersal32, influence the outcome of competitive interactions14, and regulate genetic exchange between populations67—in turn leading to the accumulation of distinctive communities of fishes in different water types.

We noted that high-transparency black- and clearwaters, as well as whitewater lakes (where transparency increases with sediment precipitation), host a larger proportion of species belonging to orders with well-developed visual systems and diurnal activity, e.g. Characiformes, Cichliformes, and Perciformes. In contrast, low-transparency whitewater river waters host a larger proportion of species belonging to orders with reduced eye size, predominantly nocturnal activity, and sensory systems that function independently of light—notably the well-developed olfactory systems of Siluriformes, active electroreception in Gymnotiformes, and passive electroreception in Siluriformes, Gymnotiformes, Myliobatiformes, and Ceratodontiformes66. These observations suggest that adaptive trade-offs between visual and non-visual sensory systems may contribute to the distinct species assemblages in waters of different transparency. Physiological adaptations for ion regulation in low waters with low ion concentrations (low conductivity) and low pH have been well documented from fishes specialized to blackwaters11,64,68,69, and likely also play a strong role in structuring fish communities.

We also observed greater differences in community structure associated with water type than with habitat type (i.e. river versus floodplain) and postulate that the similarity of adjacent floodplain and river communities arises from lateral movements of fish across the river-floodplain ecotone. These movements are documented to occur in response to the seasonal availability of food51,70,71 and dissolved oxygen62, or for reproduction72.

In addition to influencing ion regulation physiology, variation in conductivity (a measure of dissolved nutrient content) between water types may exert indirect impacts on fish community composition by influencing aquatic vegetation. For instance, the dense floating macrophyte stands unique to whitewater floodplains host distinctive communities of fishes70, many of which we encountered only in our whitewater lake samples (especially small-bodied Characidae, Supplementary Table S3 online). Similar disparities in species composition associated with nutrient availability have been reported in Amazonian bird and mammal communities, where distinct assemblages are associated with differences in tree species composition and forest biomass on nutrient-rich versus nutrient-poor soils73,74.

One important limitation of our analyses of community composition is that we sampled only the marginal habitats of river channels, thus excluding deep benthic communities dominated by Gymnotiformes and Siluriformes75,76, as well as large open-water migratory Siluriformes and Characiformes51. Future work is needed to integrate these faunal components into comparisons of assemblage structure between Amazon water types.

Species richness

Suggestive of a positive correlation between ecosystem productivity and species richness, we documented high mean (per sampling event) species richness in systems in habitats known to support high autochthonous and allochthonous PP (i.e. nutrient-rich sediment-decanted whitewater floodplain lakes), but lower mean species richness in habitats known to support lower PP (i.e. low-nutrient blackwater and clearwater rivers and floodplain lakes, and light-limited whitewater rivers). We acknowledge that we did not directly measure PP in our study sites. However, we did demonstrate that the physico-chemical conditions and other environmental parameters measured at our black-, clear-, and whitewater sites are typical for the basin and should conform to the well-documented disparities in ecosystem productivity summarized above (see “Introduction” for details).

Species-energy hypotheses predict elevated species richness under conditions of increased energy availability due to an increased number of trophic levels, heightened speciation rates (e.g. via metabolic effects on growth rates, generation times, and fecundity), or lowered extinction rates (e.g. via influences on effective populations sizes)59. Such relationships have been documented in freshwater habitats77–79 and are a well-described feature of terrestrial ecosystems58,59, including for Amazonian mammals80. However, the two previously published quantitative comparisons of fish species richness between Amazonian water types provided contradictory results; Saint-Paul et al.31 reported higher diversity in blackwaters than whitewaters, but Henderson and Crampton30 reported the opposite.

We hesitate to interpret our observations of mean species richness as evidence for a generalized species-energy relationship across Amazonian water types and habitats. In the first place, we reported the highest total, rarefied, and Chao1-estimated species richness in whitewater habitats of the mainstem R. Amazonas (with a basin size of ca. 6.3 × 106 km2), followed by clearwater habitats of the smaller R. Tapajós sub-basin (ca. 2.4 × 105 km2), and then by blackwater habitats of the much smaller R. Arapiuns sub-basin (ca. 1.8 × 103 km2). Because freshwater fish species richness is known to correlate positively with river basin size78, including for the Amazon basin7, we cannot exclude the possibility that the water-type variation in species richness we report here is biased by basin-size effects. Second, our results may also be biased by the larger area of whitewater than black- and clearwater floodplains in our study area; whitewater floodplains are generally larger than the floodplains of black- or clearwater rivers of similar size because of their high sediment load17,81. Third, although we reported less than half the mean (per sampling event) species-richness in whitewater rivers than whitewater floodplains, total and rarified species richness, as well as other indices of species diversity were all higher in whitewater rivers than whitewater floodplains (we presume the discrepancy arises from a higher rate of seasonal species turnover in whitewater rivers than floodplains). Our mean per-sampling event estimates of species richness in whitewater rivers may therefore underestimate species richness, which in turn challenges the notion that the low autochthonous PP of this habitat is associated with low species richness. Fourth, the extent to which fish populations in rivers are subsidized by energy from adjacent floodplains is poorly known. For example, studies of terrestrial-aquatic trophic linkages in blackwater rivers have confirmed that allochthonous inputs from flooded forests are the dominant energy source for riverine fish82. Likewise, stable isotope analyses suggest that detritivorous characiform fish in whitewater rivers mostly assimilate carbon originating from phytoplankton (of floodplain origin), while siluriform whitewater riverine fish assimilate carbon from trees and C3 macrophytes (also of floodplain origin)83. Much of this carbon is thought to enter the rivers as detritus, which accumulates on the river bed and supports food chains based on heterotrophic bacteria27. If these allochthonous inputs are included, rivers (whitewater in particular) may have more energy available for fish populations than implied by the low levels of autochthonous PP. Finally, because we did not sample deep benthos-specialized riverine fish and large migratory species, our estimates of riverine species richness are incomplete.

In light of these limitations, establishing a generalized habitat-wide positive species-energy relationship for Amazonian fish will ultimately require quantitative comparisons of fish species richness between the three biogeochemical water types at a larger geographical scale. Future studies should ideally select sites in river basins of variable size as well as in floodplains of varying area, and would benefit from the inclusion of whitewater systems of the upper Amazon, which exhibit higher dissolved nutrient content than those of the lower Amazon20,21,84. Our results also highlight the need for a more complete understanding of the trophic pathways by which energy is transferred from autochthonous and allochthonous primary production to fishes.

A recent basin-wide model-based analysis of Amazon fish species richness7 reported a positive correlation between species richness and “energy availability”, when corrected for sub-basin size. However, in this study energy availability was defined by terrestrial net PP estimates from the WorldClim1 dataset, which are based on solar radiation and rainfall. We suspect that this approach may be only partially informative of species-energy relationships for Amazonian fish because the PP of Amazonian aquatic systems is determined by water biogeochemistry, which is not known to correlate to solar radiation or local rainfall across the basin.

Biomass and abundance

Mirroring the patterns we report above for species richness, we documented greater mean per-sampling-event fish biomass in the systems with high ecosystem productivity (whitewater floodplains lakes) than in systems with relatively low PP (blackwater and clearwater lakes and rivers, and whitewater rivers). These relationships were not predicted a priori, because food chain models typically predict top-down trophic cascades in which elevated PP may increase consumer abundance and biomass at some trophic levels, but not others85. Moreover, evidence for positive correlations between PP and freshwater consumer biomass is fragmentary86,87. In Amazonian aquatic systems, Arbeláez et al.88 reported a strong positive correlation between water nutrient content and fish biomass in upland terra firme streams draining different geological formations. Saint-Paul et al.31 reported higher biomass in whitewaters than nearby blackwaters. However, Henderson and Crampton30 reported no year-round differences in biomass between blackwaters and adjacent whitewaters. Pereira et al.89 documented higher bat biomass (but lower species richness) in the inundation forests of nutrient-rich whitewater floodplains than in nutrient-poor blackwater floodplains.

Again, we are hesitant to interpret our result as evidence for a generalized positive energy-biomass relationship. First, our estimates of biomass were standardized by capture per unit effort (CPUE) but were not adjusted for habitat area. Second, we recall that our sampling program excluded deep river and large migratory river species, and therefore omitted an important component of riverine biomass. Nonetheless, our observations of higher biomass in whitewater floodplains than black- and clearwater habitats are consistent with the fact that whitewater floodplains have supported large commercial fisheries in the central and lower Brazilian Amazon since the 1970s, while no major commercial fishing operations occur in blackwater and clearwater river-floodplain systems—even where these form large areas near major cities (e.g. the middle-lower Rio Negro)29,90,92. Disentangling the effects of ecosystem productivity and habitat area on fish biomass and fisheries production will require sampling floodplains of variable size from all three water types, over a wider geographical area.

In conclusion, our study represents the first direct quantitative comparison of the fish faunas of the three Amazonian water types first recognized over 160 years ago by Wallace. We demonstrate for the first time that whitewater fish assemblages are distinct from the fish assemblages of oligotrophic blackwater and clearwater systems. Our study also provides novel perspectives on how PP, determined mainly by dissolved nutrient content, sediment type, water transparency, and acidity, may influence fish assemblage structure within a single megadiverse biome. Our results provide some support for a positive relationship between ecosystem productivity and both species richness and biomass. However, to confirm whether these energy richness/biomass relationships are generalized across all Amazonian water types and river-floodplain habitats, while excluding sub-basin and habitat size effects, a sampling program covering a much larger geographical area will ultimately be required. The freshwater habitats and fish biodiversity of the Amazon face unprecedented pressure from habitat degradation, over-fishing, and climate change91. Our study highlights the importance of including multiple water types and habitats in conservation monitoring and planning. Nonetheless, long-term strategies for aquatic biodiversity protection will require a fuller understanding of the effects of habitat and water type on fish diversity and distributions.

Materials and methods

Sampling

For the BW Arapiuns, CW Tapajós, and WW Amazonas rivers (Fig. 2), we sampled repeatedly at two sites (‘site replicates’ R1, R2) on the main river channel margin and two adjacent floodplain lake sites (site replicates F1, F2). Our sampling design therefore comprised six ‘water type’/’habitat type’ combinations, each replicated twice to yield 12 repeatedly sampled sites. Our sampling sites (Fig. 2) were located ca. 25 km upstream of a zone of seasonal mixing at the three-way Arapiuns-Tapajós and Tapajós-Amazonas confluence, but within the range over which most fish species would be expected to freely disperse in the absence of barriers. We selected perennial floodplain lakes (those with permanent water content for 30 + years, based on historical satellite images) of similar area (blackwater F1 = 0.17 km2, F2 = 0.25 km2; clearwater F1 = 0.18 km2, F2 = 0.21 km2; whitewater F1 = 0.18 km2, F2 = 0.26 km2). Sampling was conducted through a full year (beginning October 2014), including during low-water (October, December, February) and high-water (April, June, August), for a planned total of 72 sample events (one WW river sampling event was missed due to storms, leaving 71). For each sampling event we measured temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and conductivity with a Hanna HI-9829 meter, and turbidity with a LaMotte 2020 meter, always at 6 am, 10 cm depth, and 10 m from the shore. To maximize the diversity of sampled fish we utilized two ‘gear types’, gill and seine nets, each of which is selective of different species and body sizes. Gill nets were deployed in batteries of four (25 × 3 m, 15, 30, 45, 60 mm mesh) from 6 to 9 am and from 6 to 9 pm for every sampling event, thereby targeting species with both diurnal and nocturnal activity. Seine netting was conducted during the low-water months only—when the net could reach the bottom. We deployed a 30 × 3 m net with 5 mm mesh three times between 6 and 9 am, and three times between 6 and 9 pm. In the low-water months we pooled the results of the gill and seine nets. We emphasize that CPUE sampling effort over the year was identical for the three water types and two habitats—permitting equitable comparisons between all water type and habitat type combinations (but not between seasons). Fish were euthanized with 600 mg L−1 eugenol, fixed in 10% formalin, and preserved in 70% EtOH. Our collections were deposited at the biodiversity collections listed in Supplementary Appendix S3 online and identified using descriptions and keys from the taxonomic literature on Amazonian fish; see van der Sleen and Albert92 for recent review. Field sampling was authorized by the Brazilian Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (Scientific Expedition 02448/2012-2) and Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (permits 37742-1-4). Animal use was approved by the Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais, Pontifícia Universidade Católica, Rio Grande do Sul (Protocol 15/00,456), and by the University of Central Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocols 12–31 W, 15–24 W).

Data conditioning and statistical analysis

All procedures were performed in R93 using functions from vegan94 and MASS95, unless otherwise stated.

Physico-chemical parameters

We compiled a matrix of physico-chemical properties, henceforth ‘abiotic matrix’, at each of the 71 sampling events, conditioned by unity-based normalization. We used PERMANOVA to test for differences in physico-chemical properties between water types, and PCA to visualize groupings of sampling events by physico-chemical properties.

Comparisons of species richness, biomass, and abundance between water types and habitats

We compiled a matrix of the abundances of all species at each of the 71 sampling events, henceforth ‘biotic matrix’, from which we calculated the descriptors of richness and diversity presented in Table 1. We then performed the following three sets of analyses: (1) GLMMs, using the R package lme496 to evaluate disparities in species richness, biomass, and abundance as a function of habitat nested inside water type, and with ‘time of the year’ (month) and ‘site replicate’ (the two replicates of each water type/habitat combinations) assigned as random effect variables, e.g. biomass ~ water type/habitat type + (1|time of year) + (1|site replicate). We specified negative binomial distributions (log link) for abundance and species richness, and Gamma distributions (log link) for biomass. We confirmed that residual distributions satisfied model assumptions. Finally, we calculated the least square means and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each habitat/water type combination using the R package emmeans97, and tested the significance of differences by Tukey’s HSD. (2) NMDS based on ranked Bray–Curtis dissimilarity indices of square root-transformed species abundances, with five dimensions, to visualize differences in assemblage structure between water types and habitats. (3) PERMANOVA to test for differences in assemblage structure between water types. We also used the PERMANOVA coefficients as indices of the relative contributions of the 20 most influential species to the differences among the three pairs of water types.

Correlation of assemblage structure to physico-chemical properties

We performed co-inertia analysis (COIA) to assess the correlation between a Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) of Bray–Curtis distances in the biotic matrix and a PCA of the abiotic matrix. A Monte Carlo-based permutation test estimated significance of the coefficient of correlation (RV value) from this COIA. We also generated a null model based on 1,000 randomizations of the biotic matrix (with species shuffled between water/habitat types but row and column totals constrained) from which we derived a mean COIA RV value with 95% CIs. We assumed observed RV values outside the null 95% CIs did not arise by chance.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by US National Science Foundation grant DEB-1146374 (Aquatic Faunal Survey of the Lower Amazon) to WGR Crampton. B. Calegari, A. Colares-Canto, P. Campos, J. Fontanelle, B. Luiza, K. Mandrekar, G. Matos-Silva, D. McGrath, H. Napoleão, R. Silva-Oliveira, P. Tavares, and A. Van Nynatten provided field and lab assistance.

Author contributions

W.G.R.C. and J.D.B. conceived and designed the study, with advice from F.C.T.L., S.B.C., D.G.J., and N.R.L. J.D.B., F.C.T.L., C.S., F.R.R., and W.G.R.C. performed field work and specimen-based data collection. S.B.C. and D.G.J. provided statistical advice. J.D.B. and W.G.R.C. wrote the manuscript; F.C.T.L., S.B.C., C.S., D.G.J., F.R.R., N.R.L., and R.E.R. provided editorial advice.

Data availability

All data in support of the results presented herein are provided in supplementary documents.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-72349-0.

References

- 1.Fricke, R., Eschmeyer, W. N. & van der Laan, R. Eschmeyer's catalog of fishes: genera, species, references (https://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/fishcatmain.asp) (Electronic version accessed 01 December 2019) (2019).

- 2.Crampton, W. G. R. in Historical biogeography of neotropical freshwater fishes (eds J. S. Albert & R. E. Reis) 165–189 (University of California Press, California, 2011).

- 3.Dagosta FCP, de Pinna M. The fishes of the Amazon: Distribution and biogeographical patterns, with a comprehensive list of species. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. N. Y. 2019;1–163:2019. doi: 10.1206/0003-0090.431.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reis RE, et al. Fish biodiversity and conservation in South America. J. Fish Biol. 2016;89:12–47. doi: 10.1111/jfb.13016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albert JS, Reis RE. Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albert, J. S., Petry, P. & Reis, R. E. in Historical biogeography of neotropical freshwater fishes (eds J. S. Albert & R. E. Reis) 21–58 (University of California Press, California, 2011).

- 7.Oberdorff T, et al. Unexpected fish diversity gradients in the Amazon basin. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:8681. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandes CC, Podos J, Lundberg JG. Amazonian ecology: Tributaries enhance the diversity of electric fishes. Science. 2004;305:1960–1962. doi: 10.1126/science.1101240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig JM, et al. Using community phylogenetics to assess phylogenetic structure in the Fitzcarrald region of Western Amazonia. Neotrop. Ichthyol. 2020;18:1–16. doi: 10.1590/1982-0224-2020-0004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willis SC, Winemiller KO, Lopez-Fernandez H. Habitat structural complexity and morphological diversity of fish assemblages in a Neotropical floodplain river. Oecologia. 2005;142:284–295. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1723-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Val AL, Almeida-Val VMF. Fishes of the Amazon and their Environment. Physiological and Biochemical Aspect. Berlin: Springer; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Nynatten AD, et al. To see or not to see: Molecular evolution of the rhodopsin visual pigment in neotropical electric fishes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B: Biol. Sci. 2019;286:20191182. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez MA, Lewis WM. Regulation and stability in fish assemblages of neotropical floodplain lakes. Oecologia. 1994;99:166–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00317098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Etienne RS, Olff H. Confronting different models of community structure to species-abundance data: A Bayesian model comparison. Ecol. Lett. 2005;8:493–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sioli, H. in The Amazon: Limnology and landscape ecology of a mighty tropical river and its basin Vol. 56 Monographiae Biologicae (ed H. Sioli) 127–165 (Junk, 1984).

- 16.Goulding, M., Carvalho, M. L. & Ferreira, E. G. Rio Negro, rich life in poor water: Amazonian diversity and foodchain ecology as seen through fish communities. (SPB Academic Publishing, 1988).

- 17.Junk WJ, et al. A classification of major naturally-occurring Amazonian lowland wetlands. Wetlands. 2011;31:623–640. doi: 10.1007/s13157-011-0190-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ríos-Villamizar EA, Piedade MTF, Da Costa JG, Adeney JM, Junk WJ. Chemistry of different Amazonian water types for river classification: a preliminary review. Water Soc. 2014;2(178):17–28. doi: 10.2495/13WS0021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbs RJ. Water chemistry of the Amazon river. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1972;36:1061–1066. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(72)90021-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dustan P. Terrestrial limitation of Amazon river productivity: why the Amazon River is not green. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2009;11:421–432. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furch, K. in The Amazon: Limnology and landscape ecology of a mighty tropical river and its basin (ed H. Sioli) 168–199 (Dr W. Junk, 1984).

- 22.Junk, W. J. & Furch, K. in Amazonia (eds G.T. Prance & T.E. Lovejoy) 3–17 (Pergamon/IUCN, 1985).

- 23.Devol, A. H. & Hedges, J. I. in The biogeochemistry of the Amazon basin (eds M. E. McClain, R. L. Victoria, & J. E. Richey) 275–306 (Oxford University Press, 2001).

- 24.Seyler, P. T. & Boaventura, G. R. in The biogeochemistry of the Amazon basin (eds M. E. McClain, R. L. Victoria, & J. E. Richey) 307–327 (Oxford University Press, 2001).

- 25.Wallace, A. R. A narrative of travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro, with an account of the native tribes, and observations on the climate, geology and natural history of the Amazon valley. (Reeve and Co., 1853).

- 26.Sioli H. The Amazon: Limnology and landscape ecology of a mighty tropical river and its basin. Dordrecht: Junk; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melack, J. M. & Forsberg, B. R. in The biogeochemistry of the Amazon basin (eds M.E. McClain, R. L. Victoria, & J. E. Richey) 235–274 (Oxford University Press, 2001).

- 28.Melack, J. M. & Hess, L. L. in Amazonian floodplain forests: Ecophysiology, biodiversity and sustainable management (eds W. J. Junk et al.) 43–59 (Springer, 2010).

- 29.Galacatos K, Stewart DJ, Ibarra M. Fish community patterns of lagoons and associated tributaries in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Copeia. 1996;2:875–894. doi: 10.2307/1447650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henderson PA, Crampton WGR. A comparison of fish diversity and abundance between nutrient-rich and nutrient-poor lakes in the Upper Amazon. J. Trop. Ecol. 1997;13:175–198. doi: 10.1017/S0266467400010403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saint-Paul U, et al. Fish communities in central Amazonian white- and blackwater floodplains. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 2000;57:235–250. doi: 10.1023/A:1007699130333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winemiller KO, Lopez-Fernandez H, Taphorn DC, Nico LG, Duque AB. Fish assemblages of the Casiquiare River, a corridor and zoogeographical filter for dispersal between the Orinoco and Amazon basins. J. Biogeogr. 2008;35:1551–1563. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.01917.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher TR. Plankton and primary production in aquatic systems of the Central Amazon basin. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1979;62A:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(79)90739-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fittkau, E. J., Irmler, U., Junk, W. J., Reiss, F. & Schimdt, G. W. in Tropical ecological systems: trends in terrestrial and aquatic research (eds F.B. Golley & E. Medina) 284–311 (Springer, Berlin, 1975).

- 35.Putz, R. & Junk, W. J. in The central Amazon floodplain: ecology of a pulsing system (ed W. J. Junk) 147–181 (Springer, Berlin, 1997).

- 36.Rai, H. & Hill, G. E. in The Amazon: Limnology and landscape ecology of a mighty tropical river and its basin (ed H. Sioli) 311–335 (Dr. W. Junk Publishers, 1984).

- 37.Schmidt GW. Primary production of phytoplankton in the three types of Amazonian waters II. The limnology of a tropical floodplain lake in Central Amazonia (Lago do Castanho) Amazoniana. 1973;4:139–203. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt GW. Primary production of phytoplankton in the three types of Amazonian waters III. Primary productivity of phytoplankton in a tropical floodplain lake of Central Amazonia, Lago do Castanho, Amazonas, Brazil. Amazoniana. 1973;4:379–404. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt GW. Studies on the primary productivity of phytoplankton in the three types of Amazonian waters I. Introduction. Amazoniana. 1973;4:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidt GW. Primary production of phytoplankton in the three types of Amazonian waters. IV. On the primary productivity of phytoplankton in a bay of the lower Rio Negro (Amazonas, Brazil) Amazoniana. 1976;5:517–528. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Putz R. Periphyton communities in Amazonian black- and whitewater habitats: Community structure, biomass and productivity. Aquat. Sci. 1997;59:74–93. doi: 10.1007/BF02522552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moreira-Turcq P, Seyler P, Guyot JL, Etcheber H. Exportation of organic carbon from the Amazon River and its main tributaries. Hydrol. Process. 2003;17:1329–1344. doi: 10.1002/hyp.1287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wissmar RC, Richey JE, Stallard RF, Edmond JM. Plankton metabolism and carbon processes in the Amazon River, its tributaries, and floodplain waters, Peru-Brazil, May–June 1977. Ecology. 1981;62:1622–1633. doi: 10.2307/1941517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costa MPF, Novo EMLM, Telmer KH. Spatial and temporal variability of light attenuation in large rivers of the Amazon. Hydrobiologia. 2013;702:171–190. doi: 10.1007/s10750-012-1319-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engle DL, Melack JM, Doyle RD, Fisher TR. High rates of net primary production and turnover of floating grasses on the Amazon floodplain: Implications for aquatic respiration and regional CO2 flux. Glob. Change Biol. 2008;14:369–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01481.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Junk WJ. Investigations on the ecology and production-biology of the "floating meadows" (Paspalo-Echinochloetum) on the middle Amazon Part I: The floating vegetation and its ecology. Amazoniana. 1970;2:449–495. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Junk, W. J. & Piedade, M. T. F. in The Central Amazon floodplain. Ecological Studies (ed W. J. Junk) 147–185 (Springer, Berlin, 1997).

- 48.Junk, W. J. & Piedade, M. T. F. in Amazonian floodplain forests: Ecophysiology, biodiversity and sutainable management (eds W. J. Junk et al.) 3–25 (Springer, Berlin, 2010).

- 49.Engle DL, Melack JM. Floating meadow epiphyton—biological and chemical features of epiphytic material in an Amazon floodplain lake. Freshwat. Biol. 1989;22:479–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1989.tb01120.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piedade MTF, Junk W, D'Ângelo SA, Wittmann F, Schöngart J. Aquatic herbaceous plants of the Amazon floodplains: State of the art and research needed. Acta Limnol. Brasil. 2010;22:165–178. doi: 10.4322/actalb.02202006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goulding M. The fishes and the forest. California: University of California Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Worbes, M. in The Central Amazon floodplain. Ecological Studies (ed W. J. Junk) 223–260 (Springer, Berlin, 1997).

- 53.Adis, J., Erwin, T. L., Battirola, L. D. & Ketelhut, S. in Amazonian floodplain forests: Ecophysiology, biodiversity and sutainable management (eds W. J. Junk et al.) 313–325 (Springer, Berlin, 2010).

- 54.Prance GT. Notes on the vegetation of Amazonia. III. The terminology of Amazonian forest types subject to inundation. Brittonia. 1979;31:26–38. doi: 10.2307/2806669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Junk WJ, Piedade MTF. Biomass and primary-production of herbaceous plant communities in the Amazon floodplain. Hydrobiology. 1993;263:155–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00006266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Junk WJ, Wittmann F, Schöngart J, Piedade MTF. A classification of the major habitats of Amazonian black-water river floodplains and a comparison with their white-water counterparts. Wetlands Ecol. Manag. 2015;23:677–693. doi: 10.1007/s11273-015-9412-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Junk WJ, Teresa T, Piedade F, Schöngart J, Wittmann F. A classification of major natural habitats of Amazonian white-water river floodplains (várzeas) Wetlands Ecol. Manag. 2012;20:461–475. doi: 10.1007/s11273-012-9268-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosenzweig ML. Species diversity in space and time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Evans KL, Warren PH, Gaston KJ. Species-energy relationships at the macroecological scale: A review of the mechanisms. Biol. Rev. 2005;79:1–25. doi: 10.1017/S1464793104006517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fraser RH, Currie DJ. The species richness-energy hypothesis in a system where historical factors are thought to prevail: Coral reefs. Am. Nat. 1996;148:138–159. doi: 10.1086/285915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kramer DL, Lindsey CC, Moodie GEE, Stevens ED. The fishes and the aquatic environment of the Central Amazonian basin, with particular reference to respiratory patterns. Can. J. Zool. 1978;56:717–729. doi: 10.1139/z78-101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crampton WGR. Effects of anoxia on the distribution, respiratory strategies and electric signal diversity of gymnotiform fishes. J. Fish Biol. 1998;53:307–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1998.tb01034.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gonzalez RJ, Wilson RW, Wood CM, Patrick ML, Val AL. Diverse strategies for ion regulation in fish collected from the ion-poor, acidic Rio Negro. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2002;75:37–42. doi: 10.1086/339216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gonzalez, R. J., Wilson, R. W. & Wood, C. M. in The Physiology of Tropical Fishes (eds A. L. Val, V.M.F. Almeida-Val, & D.J. Randall) 397–442 (Academic Press, 2006).

- 65.Van Nynatten AD, Bloom DD, Chang BSW, Lovejoy NR. Out of the blue: Adaptive visual pigment evolution accompanies Amazon invasion. Biol. Lett. 2015;11:20150349. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crampton WGR. Electroreception, electrogenesis and signal evolution. J. Fish Biol. 2019;95:92–134. doi: 10.1111/jfb.13922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cooke GM, Landguth EL, Beheregaray LB. Riverscape genetics identifies replicated ecological divergence across an Amazonian ecotone. Evolution. 2014;87:1–14. doi: 10.1111/evo.12410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gonzalez RJ, et al. Effects of water pH and calcium concentration on ion balance in fish of the Rio Negro, Amazon. Physiol. Zool. 1998;71:15–22. doi: 10.1086/515893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duncan WP, Costa OTF, Fernandes MN. Ionic regulation and Na+–K+-ATPase activity in gills and kidney of the freshwater stingray Paratrygon aiereba living in white and blackwaters in the Amazon Basin. J. Fish Biol. 2009;74:956–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.02156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Correa SB, Crampton WGR, Chapman LJ, Albert JS. A comparison of flooded forest and floating meadow fish assemblages in an upper Amazon floodplain. J. Fish Biol. 2008;72:629–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01752.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fernandes CC. Lateral migration of fishes in Amazon floodplains. Ecol. Freshwat. Fish. 1997;6:36–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0633.1997.tb00140.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sánchez-Botero JI, Araujo-Lima CARM. As macrófitas aquáticas como bercário para a ictiofauna da várzea do Rio Amazonas. Acta Amazon. 2001;31:437–447. doi: 10.1590/1809-43922001313447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Emmons LH. Geographic varition in densities and diversities of non-flying mammals in Amazonia. Biotropica. 1984;16:210–222. doi: 10.2307/2388054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pomara LY, Ruokolainen K, Tuomisto H, Young KR. Avian composition co-varies with floristic composition and soil nutrient concentration in Amazonian upland forests. Biotropica. 2012;44:545–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2011.00851.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crampton, W. G. R. in Fish life in special environments (eds P. Sebert, D. W. Onyango, & B. G. Kapoor) 283–339 (Science Publishers, 2007).

- 76.Duarte C, Magurran AE, Zuanon J, Deus CP. Trophic ecology of benthic fish assemblages in a lowland river in the Brazilian Amazon. Aquat. Ecol. 2019;53:707–718. doi: 10.1007/s10452-019-09720-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hugueny B, Oberdorff T, Tedesco PA. Community ecology of river fishes: a large-scale perspective. Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. 2010;73:29–62. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guégan JF, Lek S, Oberdorff T. Energy availability and habitat heterogeneity predict global riverine fish diversity. Nature. 1998;391:382–384. doi: 10.1038/34899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dodson SI, Arnott SE, Cottingham KL. The relationship in lake communities between primary productivity and species richness. Ecology. 2000;81:2662–2679. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2000). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kay RF, Madden RH, Van Schaik CP, Higdon D. Primate species richness is determined by plant productivity: Implications for conservation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:13023–13027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pires, J. M. & Prance, G. T. in Amazonia (eds G.T. Prance & T.E. Lovejoy) 109–145 (Pergamom, 1985).

- 82.Correa SB, Winemiller KO. Terrestrial-aquatic trophic linkages support fish production in a tropical oligotrophic river. Oecologia. 2018;186:1069–1078. doi: 10.1007/s00442-018-4093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Araujo-Lima CARM, Forsberg B, Victoria R, Martinelli L. Energy sources for detritivorous fishes in the Amazon. Science. 1986;234:1256–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.234.4781.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duncan WP, Fernandes MN. Physicochemical characterization of the white, black, and clearwater rivers of the Amazon Basin and its implications on the distribution of freshwater stingrays (Chondrichthyes, Potamotrygonidae) Pan-Am. J. Aquat. Sci. 2010;5:454–464. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wootton TJ, Power ME. Productivity, consumers, and the structure of a river food chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:1384–1387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Prepas EE. Total dissolved solids as a predictor of lake biomass and productivity. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1983;40:92–95. doi: 10.1139/f83-015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nixon SW. Nutrient dynamics, primary production and fisheries yields of lagoons. Oceanol. Acta. 1982;2:357–371. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arbeláez F, Duivenvoorden JF, Maldonado-Ocampo JA. Geological differentiation explains diversity and composition of fish communities in upland streams in the southern Amazon of Colombia. J. Trop. Ecol. 2008;24:505–515. doi: 10.1017/S0266467408005294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pereira MJR, et al. Structuring of Amazonian bat assemblages: the roles of flooding patterns and floodwater nutrient load. J. Anim. Ecol. 2009;78:1163–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Smith, N. J. H. A pesca no Rio Amazonas. (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, 1979).

- 91.Castello L, et al. The vulnerability of Amazon freshwater ecosystems. Conserv. Lett. 2013;6:217–229. doi: 10.1111/conl.12008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.van der Sleen P, Albert JS. Field guide to the fishes of the Amazon, Orinoco, and Guianas. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 93.R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, 2019).

- 94.Oksanen J, et al. The Vegan Package. Commun. Ecol. Pack. 2019;10:631–637. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ripley, B., Bates, D. M., Hornik, K., Gebhardt, A. & Firth, D. MASS: Functions and datasets to support Venables and Ripley, “Modern Applied Statistics with S” (4th Edition, 2002). (CRAN, 2017).

- 96.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015;67:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lenth RV, Singmann H, Love J, Buerkner P, Herve M. Package emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. Compr. R. Arch. Netw. 2019;2019:1–67. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data in support of the results presented herein are provided in supplementary documents.