Abstract

The assessment of programmed death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression by Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved predictive marker to select responders to checkpoint blockade anti-PD-1/PD-L1 axis immunotherapies. Different PD-L1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays use different antibodies and different scoring methods in tumor cells and immune cells. Multiple studies have compared the performance of these assays with variable results. Here, we investigate an alternative method for assessment of PD-L1 using a new technology known as digital spatial profiling. We use a previously described standardization tissue microarray (TMA) to assess the accuracy of the method and compare digital spatial profiler (DSP) to each FDA approved PD-L1 assay and one LDT assay and 3 quantitative fluorescence assays. The standardized cell line Index tissue microarray contains 10 isogenic cells lines in triplicates expressing various range of PD-L1. The dynamic range of PD-L1 digital counts was measured in the ten cell lines on the Index TMA using GeoMx DSP assay and readout on the nCounter platform. The digital method shows very high correlation with immunohistochemistry scored with quantitative software and with quantitative fluorescence. High correlation of PD-L1 digital DSP counts were seen between rows on the same Index TMA. Finally, experiments from two Index TMAs showed reproducibility of DSP counts were independent of variable slide storage time over a three-week period after antibody labeling but before collection of cleaved tags. In summary, DSP appears to have quantitative potential comparable to quantitative immunohistochemistry. It is possible that this technology could be used as a PD-L1 protein measurement system for companion diagnostic testing for immune therapy.

Summary:

Digital spatial profiling is a new high-plex technology with potential to multiplex hundreds of proteins on a single slide. Here the authors validate the digital aspect of the technology on a control tissue microarray with known amounts of PD-L1 expression to show it has quantitative capacity comparable to quantitative immunofluorescence.

Introduction

Assessment of Programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression has been evaluated as a predictive diagnostic test to identify patients that may benefit from immune checkpoint blockade therapies such as anti-PD-L1 (atezolizumab and durvalumab) and anti-PD-1 (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) [1–4]. For each drug, a unique diagnostic assay has been developed. Four drug specific tests are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as either companion and/or complementary diagnostic assaysusing four different antibodies and four proprietary protocols to evaluate the PD-L1 expression by chromogenic immunohistochemistry (IHC). Each assay is read subjectively by a pathologist with a range of cutoffs defining expression positivity and cell specific expression either in tumor cell (TC) and/or immune cells (IC) [5–7]. Harmonization studies have been done to compare the assays within specific tumor types [8–15]. Despite strong agreement in TC PD-L1 IHC scoring among experienced pathologists, there is a poor concordance in IC PD-L1 IHC scoring or low PD-L1 scores [8, 12, 14–17]. This diversity of assays and scoring systems has led to confusion amongst both oncologists and pathologist.

A possible solution to this issue would be an objective, reproducible, and accurate measurement of PD-L1 in tissue sections. Digital Spatial Profiling (DSP), has potential to provide a platform technology for this sort of measurement [18]. In its current form, DSP is performed on the GeoMx platform and not amenable to usage as a companion diagnostic test. But the underlying technology could be reconfigured to make a closed system, spatially informed measurement of a biomarker. DSP technology is based on a UV cleavable DNA tag conjugated to an antibody. Spatial information is conveyed by selection of a defined area in which the UV laser directed. This region of interest can be a molecularly defined spatial compartment, for example epithelial cells defined by cytokeratin expression or T-lymphocytes defined by CD3. The region of interest serves as a guide for the UV laser, which cleaves off the DNA tags which are collected and subsequently counted using the Nanostring Barcode system [18]. Thus, there can be digital counts of antibody/antigen interactions in tumor cells, or in immune cells, as defined by a molecular compartmentalization tool. Although a different, CLIA lab friendly, platform would be required, we can envision this underlying technology being used as a digital method for cell specific measurement of PD-L1.

As a proof of concept and first step to determine the digital accuracy and reproducibility of DSP, we used a standardized cell line Index tissue microarray (TMA) with 10 isogenic cells lines expressing negative, weak, intermediate and high levels of PD-L1 protein in triplicate to objectively compare PD-L1 counts to quantitative PD-L1 expression with both chromogenic and fluorescent IHC. We also test various slide storage conditions and reproducibility over time. Future studies have been and will be done on actual tumor tissue, and are separately submitted for publication.

Materials and Methods

Standardized cell line index TMA and study design

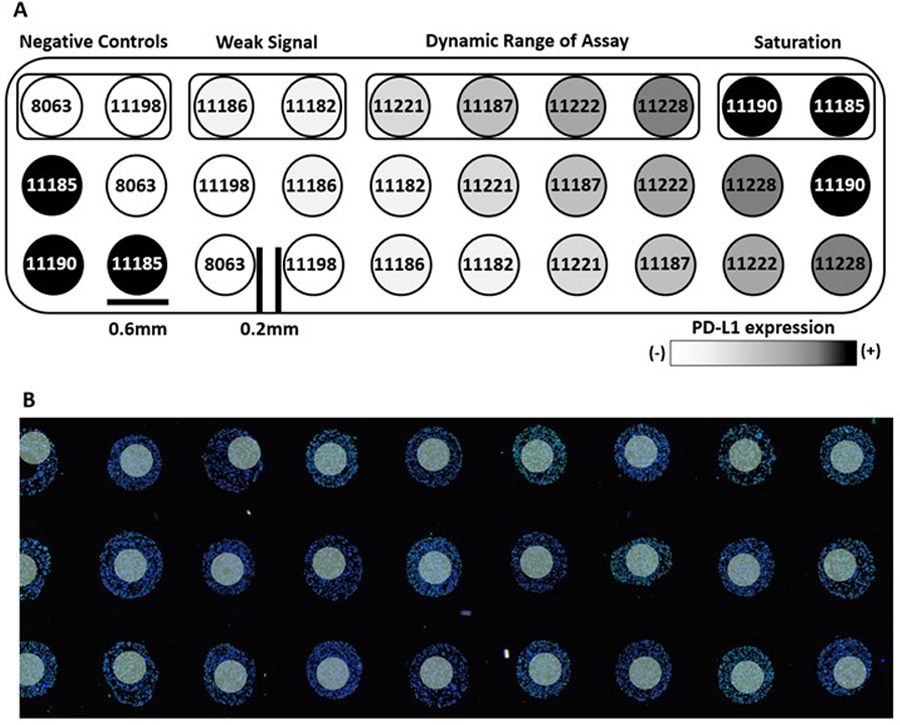

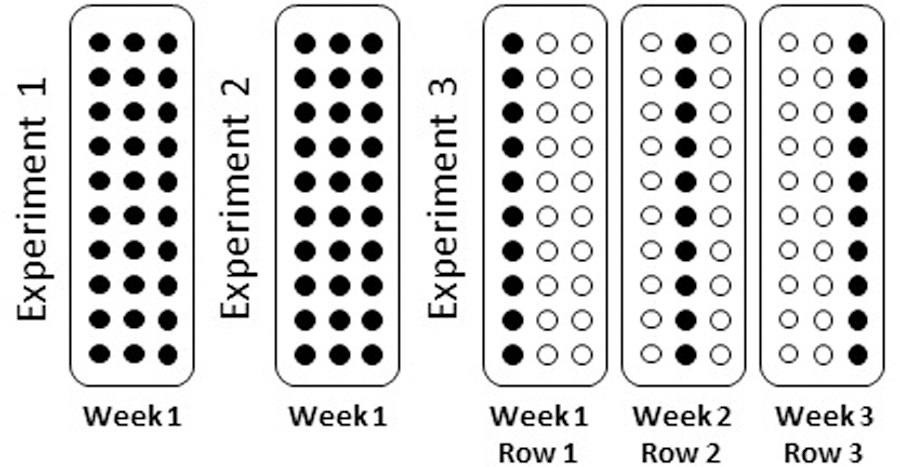

Standardized cell line index TMA map with 3-fold redundancy consists of a 10 isogenic cell line array expressing negative, low, intermediate, and high PD-L1 protein from Horizon Dx (Figure 1a). The study plan was to stain three standardized cell line index TMA’s with a pre-commercial version of the Human Immune Oncology panel, a 45 unique antibody panel conjugated with ultraviolet light photocleavable linker to unique oligonucleotide readout on the nCounter platform for a quantitative measure (Supplemental Table 1). The TMA’s were also stained with a nuclear stain (SYTO 13) as a morphology marker for visualization on the GeoMx platform (Figure 1b) [18]. For first two experiments, slides were stained and collected in the same week, whereas, for the third experiment, the slide was stained, and each row was collected one week apart (Figure 2). For storage in between collections, slides were mounted with ~200ul aqueous mounting media (SouthernBiotech, 0100–01) to cover the cell pellets and stored in the dark at room temperature. To unmount the slides, the slides were place in TBST for 1hr until coverslips easily slid of the cell pellets.

Figure 1: Index TMA layout for PD-L1 quantification.

(A) Schematic map along with ten standardized cell line codes and (B) representative image of the stained standardized TMA and 300um diameter ROIs as white circles.

Figure 2: Overview of Experimental Plan.

Three standardized TMA were stained with Human IO panel and nuclear stain. First two experiments were stained and collected in the same week. Third experiment was stained and each row was collected one week apart.

Sample preparation for protein digital spatial profiling

TMA slides were stained using a protocol previously described [19]. Briefly, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) 5µm sections were deparaffinized at 60°C for 30 minutes, then incubated thrice in CitriSolv (Decon Labs, Inc., 1601) for 5 min. Rehydration was performed with 100% ethanol twice for 10 min, 95% ethanol twice for 10 min and dH2O twice for 5 min. Antigen retrieval was performed with 1× citrate buffer pH 6.0 (Sigma-Aldrich, C9999) in a lid covered metal jar placed into a pressure cooker (BioSB, BSB 7008) on high pressure and temperature setting for 15 min. The metal jar was removed from the pressure cooker and cooled at room temperature for 25 min. Slides were washed with 1XTBST (Cell Signaling Technology, 9997) five times for 2 min and blocked with buffer W (NanoString, Seattle WA) for 1 h. Tissue sections were then stained with the Beta Human IO Protein panel and a nuclear stain as a morphology markers in Buffer W overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed with 1XTBST thrice for 10 min, fixed with 4% PFA (Thermo Scientific, 28906) for 30 min and washed again with 1XTBST twice for 5 min. DNA was counterstained with 500 nM SYTO 13 (NanoString, Seattle WA) diluted in 1XTBS (Cell Signaling Technology, 12498) for 15 min. Excess SYTO 13 was removed with one wash of 1XTBS for 5 min, and each slide was processed in an automated manner on the GeoMx DSP platform. SYTO 13 DNA dye was used as a visualization marker to identify regions of interest (ROIs). Per section, one ROI of 300um was selected and photocleaved oligonucleotides were released upon ultraviolet radiation exposure (Figure 1b). Released photocleaved oligonucleotides were collected via a microcapillary tube inspiration robotic system and transferred into a 96-microwell plate.

Hybridization assay

Hybridization of photocleaved oligonucleotides to optical fluorescent barcodes or GeoMx Hyb codes was performed using the nCounter Protein HybCode (NanoString) as directed by the manufacture’s protocol. In short, the photocleaved oligonucleotides were dried down and resuspended in 10μl of DEPC water. For the hybridization reaction 3μl of the reconstituted oligonucleotides, 5μl of ddH20 and 8μl of the appropriate GeoMx HybCode was combined and hybridized at 67°C for 18h with a 70°C heated lid on a thermocycler. Post-hybridization, 3μl per hybridization is pooled and processed using the nCounter PrepStation and Digital Analyzer according to the manufacturer’s instructions (NanoString, Seattle WA).

nCounter data analyses

Digital raw counts from barcodes corresponding to protein probes were first normalized with internal spike-in controls (ERCCs) to account for system variation, and then normalized to the endogenous control Histone H3. For signal to noise ratio, ERCC normalized digital counts were divided by geometric mean of all isotype controls (Mouse IgG1, Mouse IgG2a and Rabbit IgG).

Quantitative immunofluorescence

TMA slides were stained using a protocol described in our previous study [15]. Primary antibodies for PD-L1 E1L3N and SP142 were incubated overnight at 4 °C and clone SP263 was incubated for 20 minutes at 37 °C. Then, slides were incubated in rabbit EnVision reagent for 1 h at RT and Cy5-Tyramide was used to amplify target signal. Finally, TMAs were stained with 1:250 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 10 min at RT and mounted with Prolong Gold antifade mounting reagent. Image analysis was performed using AQUA method of QIF (NavigateBP), which generates a score by dividing the sum of target pixel intensities by the area of all nuclei compartment (DAPI staining). Three independent experiments were performed for each antibody.

Immunohistochemistry and digital analyses

Automated systems were used for different chromogenic PD-L1 assays, using protocols specified by corresponding manufacturer. Per the FDA-approved assays, 22C3 and 28–8 were stained with the Dako Autostainer Link 8 Instrument, and SP263 and SP142 were used on the Benchmark Ultra from Ventana Medical Systems, Inc. The LDT E1L3N assay was performed on a Leica Bond Autostainer. After chromogenic staining using DAB (3,3’-Diaminobenzidine), slides were scanned on the Aperio ScanScope XT platform. PD-L1 expression was quantified using the open source software QuPath [20]. An optimized algorithm was used for cell segmentation based on the size of the nucleus and cell expansion, and for DAB intensity quantification of PD-L1 expression based on DAB optical density (OD) mean. The settings were adjusted to avoid false positive detection. Results were shown as percentage of PD-L1+ cells or as OD of the chromogenic staining divided by mm2. Ten independent experiments were performed for each assay, including two slides per experiment.

Statistical analyses

Pearson’s correlation (R2) was computed for regression within GeoMx DSP or among GeoMx DSP, quantitative immunofluorescence (QIF) and IHC DAB results. All data sets were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism v7.0 software for Windows (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results

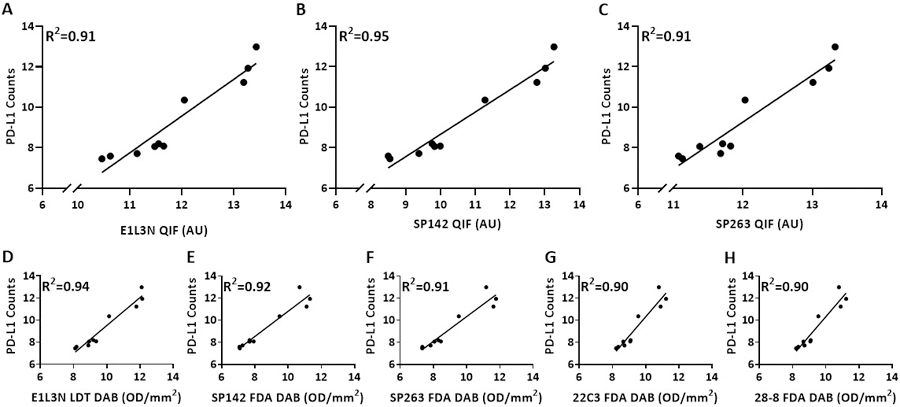

To compare the DSP technology to conventional methods of assessment of protein on slides, we assessed PD-L1 expression compared to QIF and IHC DAB using standardized cell line index TMA. An average of six cores per cell line were evaluated for PD-L1 counts (three cores per cell line/two experiments) by DSP. This was compared to QIF quantification using three different PD-L1 antibodies on an average of 9 cores per cell line. Concordance of PD-L1 measurement between QIF scores obtained with three antibodies E1L3N, SP142, and SP263 and DSP counts was high, with coefficients >0.91 (Figure 3a–c). Five conventional IHC assays based on chromogenic visualization were performed and an average of 60 cores per cell line were measured for each assay (three cores per cell line/ten experiments/two slides per experiment). Four of the IHC assays are those currently FDA approved for companion or complementary testing for immunotherapy including assays named SP142, SP263, 22C3 and 28–8. A commonly used LDT assay based on the E1L3N antibody was also tested [15]. In each case, agreement with DSP counts for PD-L1 expression was excellent with coefficients ranging from 0.90 to 0.94 (Figure 3d–h).

Figure 3: Correlation of Log2 transformed PD-L1 data from GeoMx DSP, QIF and IHC DAB.

Regression of PD-L1 protein expression by DSP with (A-C) QIF assay performed using 3 antibodies (E1L3N, SP142, and SP263) and (D-H) IHC DAB assay performed using 5 antibodies (E1L3N, SP142, SP263, 22C3 and 28–8). Each dot represents average of 2 TMAs (GeoMx DSP), 3 TMAs (QIF) and 20 TMAs (IHC DAB) with 3 pellet per cell clone in one TMA.

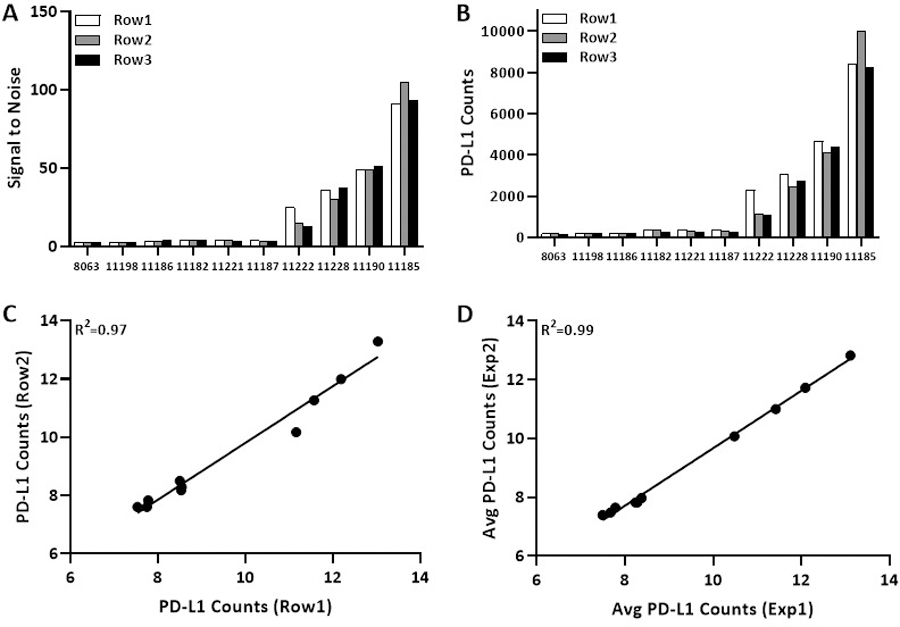

In order to assess the PD-L1 expression dynamic range between IHC and DSP, the Index TMA was used. The dynamic range of PD-L1 expression on the Index TMA was evaluated either as signal to noise ratio or PD-L1 counts. Signal to noise ratio in cell lines 8063 and 11198 was below 3 for all three rows in both the Index TMAs. Thus, confirming them as negative control. As expected, signal to noise ratio was highest in the highest expressing cell lines with one line averaging nearly 10,000 counts and a signal to noise ratio of nearly 100 (Figure 4 and Supp Figure 1).

Figure 4: Reproducibility across rows and experiments stained and collected in the same week.

Bar graph show (A) signal to noise ratio and (B) PD-L1 counts for three rows from same experiment. Regression on Log2 scale for PD-L1 counts (C) between two rows from same experiment and (D) average PD-L1 counts of three rows between two experiments.

Correlation of PD-L1 counts in ten cell lines on the same index TMA were also assessed for reproducibility between rows and experiments on different days. The concordance was very high between rows (R2=0.97, figure 4c) and experiments on different days (average of three cores per cell line) from two Index TMAs (R2=0.99, figure 4d). Similar associations were observed for DSP counts of all targets from same cell line across two rows from same Index TMA and two experiments (average of three cores per cell line) from two Index TMAs, with coefficient 0.98 (Supp Figure 2a,b).

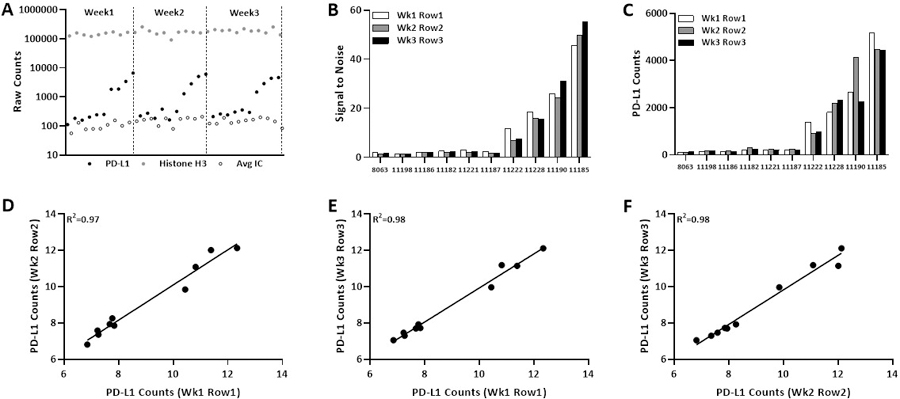

Finally, to test the robustness and reproducibility of GeoMx DSP count upon slide storage after antibody labeling but before cleavage and sipping of cleaved tags, we stained a standardized cell line index TMA with 45 markers and collected cleaved tags one week apart from each row for three consecutive weeks (Figure 2). For ten cell lines collected in three consecutive weeks, the distribution of un-normalized Histone H3 and average isotype control counts were consistent whereas the raw PD-L1 counts showed dynamic range of the PD-L1 expression in each week as expected (Figure 5a). Similar to previous finding described above, signal to noise ratio and PD-L1 counts were consistent and unchanged by longer storage prior to tag cleavage and collection (Figure 4b,c). Regression analysis of PD-L1 counts after progressively longer storage showed excellent concordance between three rows of ten cell lines collected on three consecutive weeks, with coefficients ranging from 0.97 to 0.98. Excellent correlations were observed for DSP counts of all targets from same cell line between rows of ten cell lines collected one week apart from each other from same Index TMA, with coefficient 0.97 (Supp Figure 2c,d).

Figure 5: Reproducibility across rows collected one week apart from same staining.

(A) Distribution of PD-L1, Histone H3 and average IC raw counts from all cell pellet collected one week apart. Bar graph show (B) signal to noise ratio and (C) PD-L1 counts for three rows. Regression on Log2 scale for PD-L1 counts (D-E) between two rows collected on different weeks.

Discussion

Expression of PD-L1 protein by IHC has been utilized to predict response to the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 axis immunotherapies in more than 15 cancer types [21]. There are currently four FDA approved PD-L1 IHC assays as companion and/or complementary diagnostic tests, with different antibodies, cut points, scoring systems and cell specific expression associated with each test resulting in confusion in pathology labs for patients and their physicians. Since many studies have showed variable results with current assays [8–15], we have begun efforts to generate more quantitative and reproducible results. While DSP is not ready for the clinic, the technology behind the platform shows the kind of robustness and reproducibility that is typical for laboratory medicine pathology tests (generally better than IHC).

DSP instrument uses DMD mirrors to perform the spatially resolved profiling. This technology allows selection of regions of different shape or size, including regular (i.e. grid pattern) or irregular (i.e. areas defined by cell borders or proximity to specific tissue type) boundaries. The current platform on which the DSP assay is delivered has a number of limitations, representing the early state of the technology. First, profiling with DSP is expensive and it is inconvenient to fit the assay into an 8-hour day over current pathology IHC laboratory assays, but DSP has the ability to get high-multiplexed, quantitative and reproducible information. Second, DSP system is challenging for profiling every cell in the tissue at single cell resolution. Although imaging based methods have ability to generate multiplexed information on every cell in the tissue, DSP offers high-plex profiling capabilities in ROIs and tissue compartments. Therefore, imaging based methods and DSP are complementary to each other. Third, DSP technology aligns well with Laser Capture Microdissection technologies. However, DSP offers advantage of being high-throughput and automated. Lastly, DSP assay also requires manual or molecular selection of compartments for analysis which would need to be more accurately defined prior to clinical translation. The results of this study allow protocol modifications that may facilitate the development of this technology by increasing operator convenience. A major limitation of this study includes the usage of isogenic cell line for assessing PD-L1 sensitivity and reproducibility instead of tissue. Future studies will assess tissue where expression of PD-L1 may be different or possess post-translational modifications in tumors that might not be reflected in these cell lines. However, in testing analytic validity, this approach has advantages including elimination of tissue heterogeneity from the experiment in the comparison of platform reproducibility.

In summary, we were able to objectively quantity the PD-L1 expression in this standardized cell line Index TMA and report the DSP assay to be highly reproducible and independent of slide storage. While not yet “packaged” for the pathology lab, we believe the underlying DSP technology is truly digital and has the potential to accurately measure protein expression on a slide in a “closed box” system. We look forward to next generation DSP devices that may have the capacity to automate, standardize and quantify protein within spatially defined compartments in an objective manner.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This study was supported by instrumentation from NanoString and funding from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and the Yale SPORE in Lung Cancer.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PD-L1

Programmed cell death ligand 1

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- TC

tumor cells

- IC

immune cells

- TMA

tissue microarray

- DSP

GeoMx Digital Spatial Profiler

- FFPE

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- ROIs

regions of interest

- ERCCs

internal spike-in controls

- QIF

quantitative immunofluorescence

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

DLR is a consultant/advisor to Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Agendia, Biocept, Biocept, BMS, Cell Signaling Technology, Cepheid, Daiichi Sankyo, GSK, InVicro/Konica Minolta, Lilly, Merck, Perkin Elmer, PAIGE.AI, Sanofi and Ultivue. KF is an employee of Nanostring. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente D, Murakami S, Hui R, et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377(20):1919–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387(10027):1540–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horn L, Spigel DR, Vokes EE, Holgado E, Ready N, Steins M, et al. Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Patients With Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Two-Year Outcomes From Two Randomized, Open-Label, Phase III Trials (CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057). J Clin Oncol 2017;35(35):3924–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDermott DF, Sosman JA, Sznol M, Massard C, Gordon MS, Hamid O, et al. Atezolizumab, an Anti-Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Antibody, in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Long-Term Safety, Clinical Activity, and Immune Correlates From a Phase Ia Study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(8):833–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-L1 Expression as a Predictive Biomarker in Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther 2015;14(4):847–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366(26):2455–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadiot J, Hooijkaas AI, Kaiser AD, van Tinteren H, van Boven H, Blank C. Overall survival and PD-L1 expression in metastasized malignant melanoma. Cancer. 2011;117(10):2192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batenchuk C, Albitar M, Zerba K, Sudarsanam S, Chizhevsky V, Jin C, et al. A real-world, comparative study of FDA-approved diagnostic assays PD-L1 IHC 28–8 and 22C3 in lung cancer and other malignancies. J Clin Pathol 2018;71(12):1078–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tretiakova M, Fulton R, Kocherginsky M, Long T, Ussakli C, Antic T, et al. Concordance study of PD-L1 expression in primary and metastatic bladder carcinomas: comparison of four commonly used antibodies and RNA expression. Mod Pathol 2018;31(4):623–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujimoto D, Sato Y, Uehara K, Ishida K, Fukuoka J, Morimoto T, et al. Predictive Performance of Four Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Assay Systems on Nivolumab Response in Previously Treated Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13(3):377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendry S, Byrne DJ, Wright GM, Young RJ, Sturrock S, Cooper WA, et al. Comparison of Four PD-L1 Immunohistochemical Assays in Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13(3):367–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rimm DL, Han G, Taube JM, Yi ES, Bridge JA, Flieder DB, et al. A Prospective, Multi-institutional, Pathologist-Based Assessment of 4 Immunohistochemistry Assays for PD-L1 Expression in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017;3(8):1051–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratcliffe MJ, Sharpe A, Midha A, Barker C, Scott M, Scorer P, et al. Agreement between Programmed Cell Death Ligand-1 Diagnostic Assays across Multiple Protein Expression Cutoffs in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23(14):3585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch FR, McElhinny A, Stanforth D, Ranger-Moore J, Jansson M, Kulangara K, et al. PD-L1 Immunohistochemistry Assays for Lung Cancer: Results from Phase 1 of the Blueprint PD-L1 IHC Assay Comparison Project. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12(2):208–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaule P, Smithy JW, Toki M, Rehman J, Patell-Socha F, Cougot D, et al. A Quantitative Comparison of Antibodies to Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 1. JAMA Oncol 2017;3(2):256–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsao MS, Kerr KM, Kockx M, Beasley MB, Borczuk AC, Botling J, et al. PD-L1 Immunohistochemistry Comparability Study in Real-Life Clinical Samples: Results of Blueprint Phase 2 Project. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13(9):1302–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunnstrom H, Johansson A, Westbom-Fremer S, Backman M, Djureinovic D, Patthey A, et al. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry in clinical diagnostics of lung cancer: inter-pathologist variability is higher than assay variability. Mod Pathol 2017;30(10):1411–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merritt CR, Ong GT, Church S, Barker K, Geiss G, Hoang M, et al. High multiplex, digital spatial profiling of proteins and RNA in fixed tissue using genomic detection methods. bioRxiv 2019. Available from 10.1101/559021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toki MI, Merritt CR, Wong PF, Smithy JW, Kluger HM, Syrigos KN, et al. High-Plex Predictive Marker Discovery for Melanoma Immunotherapy-Treated Patients Using Digital Spatial Profiling. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25(18):5503–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernandez JA, Dombrowski Y, McArt DG, Dunne PD, et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep 2017;7(1):16878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348(6230):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.