Abstract

Background:

The mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus (Vmes) is not only anatomically adjacent to the locus coeruleus (LC) but is also tightly associated with the function of the LC. The LC can be the first area in which Alzheimer’s disease (AD) develops, although it is unclear how LC neuronal loss occurs.

Objective:

We investigated whether neuronal death in the Vmes can be spread to adjacent LC in female triple transgenic (3×Tg)-AD mice, how amyloid-β (Aβ) is involved in LC neuronal loss, and how this neurodegeneration affects cognitive function.

Methods:

The molars of 3×Tg-AD mice were extracted, and the mice were reared for one week to 4 months. Immunohistochemical analysis, and spatial learning/memory assessment using the Barnes maze were carried out.

Results:

In 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, aggregated cytotoxic Aβ42 was found in granules in Vmes neurons. Neuronal death in the Vmes occurred after tooth extraction, resulting in the release of cytotoxic Aβ42 and an increase in CD86 immunoreactive microglia. Released Aβ42 damaged the LC, in turn inducing a significant reduction in hippocampal neurons in the CA1 and CA3 regions receiving projections from the LC. Based on spatial learning/memory assessment, after the tooth extraction in the 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, increased latency was observed in 5-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice 1 month after tooth extraction, which is similar increase of latency observed in control 8-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice. Measures of cognitive deficits suggested an earlier shift to dementia-like behavior after tooth extraction.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that tooth extraction in the predementia stage can trigger the spread of neurodegeneration from the Vmes, LC, and hippocampus and accelerate the onset of dementia.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid-β, behavior, locus coeruleus, neurodegeneration, tooth loss, trigeminal nuclei

INTRODUCTION

A great deal of research has been performed on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk factors, and aging is commonly recognized as the strongest risk factor for AD. AD is pathologically characterized by plaques containing aggregates of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides derived from amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP/APP), as well as by neurofibrillary tangles containing hyperphosphorylated tau. Since there are currently no effective treatments for AD, many AD studies are shifting focus from the dementia stage to prevention at the mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or preclinical stage [1]. Although many AD risk factors have been identified, it is still unclear what triggers AD progression, and causes the spread of neurodegeneration.

The locus coeruleus (LC) has been shown to be the first brain region in which AD develops [2], and the volume of the human LC decreases according to the Braak stage [3]. It has also been suggested that the decrease in LC volume due to aging is limited; thus, another factor is needed to reduce the volume of the LC. Anatomically, LC is located adjacent to the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus (Vmes) in the lateral part of the periaqueductal gray matter of the fourth ventricle, and LC and Vmes are affecting each other [4]. Based on this notion, it is highly possible that neurodegeneration in Vmes can spread to the LC. Previous studies have shown that the nerve endings of Vmes neurons are distributed in the periodontal ligament as well as muscle spindles of the masticatory muscles [5], and that the degeneration of Vmes neurons leading to neuronal loss in the Vmes occurs after peripheral axotomy [6] and tooth extraction [7].

Clinically, many cohort studies have demonstrated that poor oral health leading to tooth loss and periodontal diseases are major risk factors for the progression of cognitive impairment [8, 9], and recently several studies indicated the association between tooth loss and cognitive function [10–15]. It has been suggested that tooth loss has effects on the progressive development of dementia due to chronic inflammation caused by periodontitis [15, 16], the invasion of oral pathogens and their toxins into the brain [17], reduced masticatory forces [18, 19], and neurodegeneration in the hippocampus [20]. The previous issue of tooth loss has been shown of how masticatory reduction, poor dental hygiene, and edentulism affect cognitive function. However, these proposed mechanisms for the association between tooth loss and the central nervous system (CNS) are indirect, and the direct neurodegenerative pathway from Vmes to the hippocampus after tooth loss needs to be elucidated. That is, it is not how the state of tooth loss affects the progression of AD, but how the neurodegeneration caused by tooth loss is involved in the progression of AD.

If tooth loss is associated with the onset of AD, the question arises as to why elderly but not young people develop AD when they lose their teeth. In elderly individuals in the MCI stage, the amount of Aβ in the cerebrospinal fluid has already reached a plateau [21], and APP transgenic mice show specific learning deficits due to the deposition of Aβ in neurons before amyloid plaque formation [22]. Although major pathological changes are found in the cerebrum, Aβ accumulation occurs in the brainstem in even 2-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice [23]. As the vulnerability of specific brain regions to Aβ deposition has been found in AD [24], the vulnerability of the LC is affected by cytotoxic Aβ spreading after neuronal death in the Vmes. Thus, the death of Vmes neurons with cytotoxic Aβ deposits due to aging may affect the progression of AD through the neurodegeneration of LC neurons.

To evaluate whether the neurodegeneration of Vmes neurons is the trigger for the progression of AD, we investigated whether neurodegeneration in the Vmes induced by tooth extraction can spread to the LC and even the hippocampus. Additionally, we examined the neurodegeneration of Vmes neurons by tooth extraction may accelerate the progression from the predementia stage to the dementia-like stage in female 3×Tg-AD mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Female homozygous 3×Tg-AD mice harboring three AD-related genetic loci, human PS1M146V, human APPswe, and human tauP301L [25], generated from breeding pairs were used in this study. Food and water were available ad libitum, and animals were maintained under a 12 h :12 h light-dark cycle. The experiments were approved by the Committee for Animal Experiments of Kagoshima University (approval number: D17016). Female C57BL/6 mice were used as wild-type controls. For brain histology, we analyzed mice at 2, 4, and 7 months of age. The mice were sacrificed 7, 14, and 30 days after tooth extraction. For the behavior test, 4-, 5-, 6-, 7-, and 8-month-old mice with or without tooth extraction were used. For tooth extraction, mice were deeply anesthetized with a combination anesthetic of medetomidine (0.15 mg/kg; Kobayashi Kako, Fukui, Japan), midazolam (2 mg/kg; Astellas Pharma, Tokyo, Japan), and butorphanol (2.5 mg/kg; Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) [26]. All mice were sacrificed by deep anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital (75 mg/kg body weight) and transcardial perfused with of 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.3), followed by 100 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde, 75% saturated picric acid, and 0.1 M Na2HPO4 (adjusted to pH 7.0 with NaOH). The brains were then removed and postfixed with the same fixative for 4 h at 24°C. After cryoprotection with 30% sucrose in PBS, the brainstems were cut on a freezing microtome, divided into 14 blocks containing six adjacent series of 50-μm sections from the rostral side to the caudal side of the Vmes, and stored at 4°C in PBS.

Surgery

For the tooth loss model, female 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice were anesthetized with a combination anesthetic as described above. In the extraction group, the bilateral 6 maxillary molar teeth were extracted using a dental probe. The mice in the sham group underwent the same general anesthesia and mouth opening without tooth extraction. The animals were given powdered food (Rodent LabDiet 5L37, Nutrition International, Brentwood, MO, USA), and the weight of each animal was checked every month.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on free-floating mouse tissue sections. The primary antibodies used in this study were as follows: mouse anti-Aβ (1 : 2000, 6E10; Covance, Princeton, NJ), rabbit anti-Piezo2 (1 : 1000, NBP1-7862, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), rabbit anti-phosphorylated (p)-Tau (Ser396) (1 : 100, 44-752G, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), mouse anti-Aβ42 (1 : 2000; BC05, Fujifilm/Wako, Osaka, Japan), mouse anti-activat transcription factor 3 (ATF3) (1 : 1000; 44C3a, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (1 : 1000; LNC1, Millipore, Bedford, MA), mouse anti-ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1) (1 : 1000, NCNP24, Fujifilm/Wako, Osaka, Japan), rabbit anti-caspase-3 (1 : 200, NB600-1235, Novus Biologicals), and rabbit anti-CD86 (1 : 200, BS-1035R, Bioss, MA).

For immunofluorescence, the sections were incubated overnight at 24°C with primary antibodies in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100, 0.02% sodium azide, 0.12% lambda-carrageenan, and 1% donkey serum (PBS-XCD) and then for 4 h with 1 mg/ml Alexa Fluor 647-, 555-, and 488- conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibody (1 : 1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PBS-XCD. All of the above incubations were performed at 24°C and were followed by rinsing with PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBS-X). Some sections were incubated with NeuroTrace green (1 : 200, N21480, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The sections were observed under a confocal scanning laser microscope (LSM700, Zeiss; Oberkochen, Germany) or a Nikon Eclipse E800M microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a COMOS MP-102300A digital camera (Bio Tools Inc., Gunma, Japan).

For immunoperoxidase staining, the sections were incubated with 1% H2O2 in PBS for 30 min, washed with PBS-X. Then the sections were incubated with mouse anti-Aβ (1 : 2000, 6E10; Covance) overnight, biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (1 : 200; Vector Labs, Burlington, CA) in PBS-XCD for 3 h, and then avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (1 : 100; elite variety, Vector) in PBS-X for 1 h. Finally, sections were incubated with 0.02% diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and 0.005% H2O2 in 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6) for 10 min. The sections were mounted on gelatin-coated glass slides and stained with 0.1% cresyl violet solution for 30 min, then observed under an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a DP25 camera (Olympus) and cellSens software (Olympus).

Retrograde labeling

In three female 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, a 2% fluorogold solution (FG; Fluorochrome, Englewood, CA) in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3, was iontophoretically injected into the ipsilateral dorsal hippocampus through a glass micropipette. After 7 days, mouse tissues were fixed as described above. The sections were immunostained by incubating overnight at room temperature with rabbit anti-FG polyclonal primary antibody (1 : 1000; AB153, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) in PBS-X, followed by biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1 : 200; Vector Labs) in PBS-XCD for 3 h, and then avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (1 : 100) in PBS-XCD for 1 h. Finally, the sections were incubated with 0.02% diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and 0.005% H2O2 in 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer for 10 min, and counterstained with Nissl. The sections were observed under an Olympus EX51 microscope (Olympus) equipped with an Olympus OP25 camera (Olympus).

Behavior test

For the assessment of spatial learning and memory, we used a Barnes maze with a diameter of 120 cm and 20 holes. One of these holes was connected to a shelter in a desirably darkened and enclosed target box below the table, which allowed the mouse to escape from an aversive bright light stimulus (150 W) [27]. For habituation to the test equipment, each mouse was carefully placed at the center of the table, and gently guided to the correct escape hole. Next, the mouse was placed in a black cylinder at the center of the maze for 15 s. Subsequently, the cylinder was removed, and the mouse was allowed to explore the maze until it found and entered the target box. A trial ended when the mouse found and escaped into the target box within 3 min. The next day was designated day 1. Two trials were conducted each day for 5 consecutive days. Each mouse was allowed to stay in the target box for 1 min and was then returned to the home cage. If a mouse could not find the escape box after 4 min, it was gently guided toward the escape hole and left there for 35 s. The latency to find the escape hole, the number of passes over the target, freezing time on the target, and freezing time off the target (i.e., on the wrong hole) were recorded. We defined the number of passes over the target as the number of passes through the escape hole before the mouse entered the escape hole. We also defined freezing time on the target as the total freezing time at the edge of the escape hole and freezing time off the target as the total freezing time at the wrong hole edge.

Statistical analysis

All numerical values and error bars in the graphs represent the means±SDs except for the latency data in the Barnes maze test (mean±SEMs). Statistical comparison of mean values was performed using unpaired Student’s t test or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis using R package.

RESULTS

Differences in intraneuronal Aβ deposition by neurons in the trigeminal nervous system

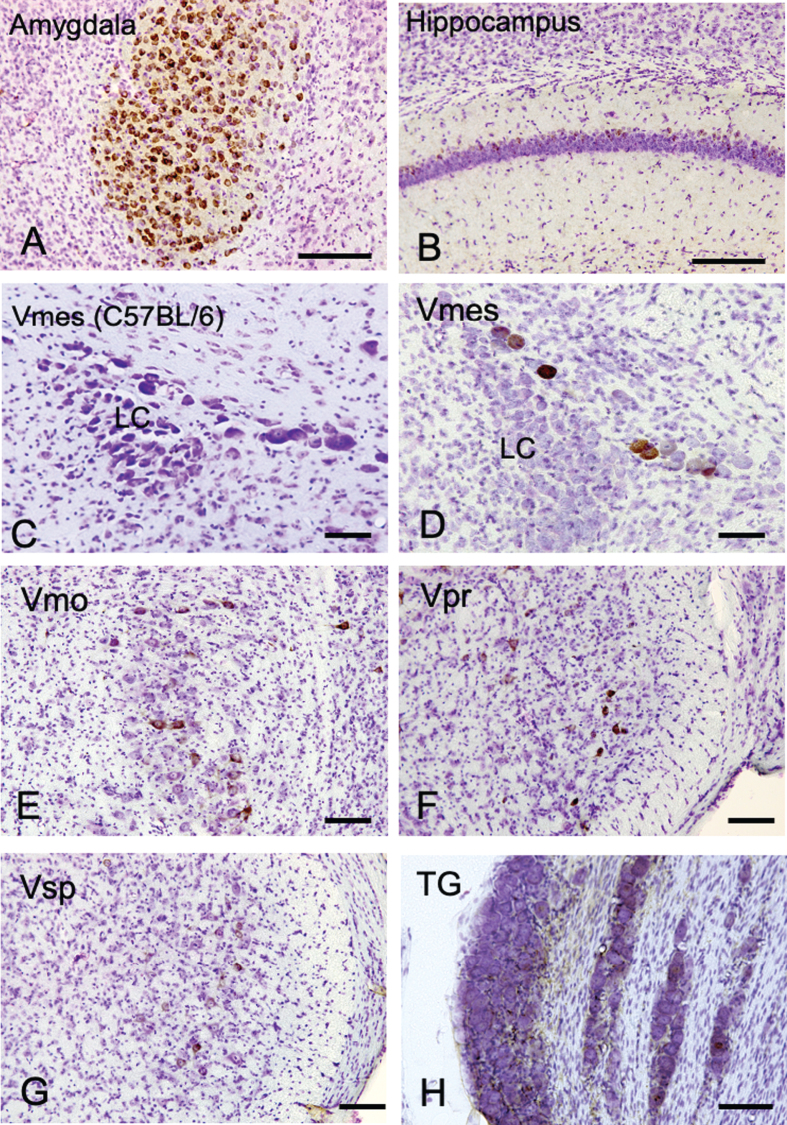

We first examined where Aβ deposits, a characteristic neurodegenerative lesion in AD, appears most prominently in trigeminal neurons using female 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice. As a positive control, the amygdala and hippocampus of female 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice were examined using an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10) (Fig. 1A, B). Strong Aβ immunopositivity was observed in neurons in the amygdala, and weak Aβ immunopositivity was observed on the relatively dorsal region in the hippocampus. Since 6E10 antibody does not react with mouse Aβ, we used tissue of C57BL/6 mice as a negative control, and no immunoreactivity of Aβ was observed in the Vmes in C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1C). Neither C57BL/6 trigeminal nerve cells were positive for 6E10 immunoreactivity (Supplementary Figure 1). In the trigeminal nervous system, intensely Aβ-immunoreactive (IR) neurons were found in the Vmes (Fig. 1D), and no Aβ-IR neurons were found in LC on the ventral side of Vmes. Scattered Aβ-IR neurons were observed in the trigeminal motor nucleus (Vmo) (Fig. 1E), trigeminal principal nucleus (Vpr) (Fig. 1F), and trigeminal spinal nucleus (Vsp) (Fig. 1G). Few Aβ-IR neurons were found in the trigeminal ganglion (TG) (Fig. 1H). Based on these findings, the Vmes had the strongest Aβ deposition in the trigeminal nervous system in 3×Tg-AD mice.

Fig.1.

The distribution of Aβ-IR neurons in the cerebrum and the trigeminal nervous system in 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice using an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10). A, B) In the positive control, strong Aβ-IR neurons were found in amygdala, and relatively weak Aβ immunopositivity was observed in the hippocampus. C) In wild-type C57BL/6 mice, which were used as negative controls, no Aβ-IR Vmes neurons were found. D–H) In the trigeminal nervous system intensely Aβ-IR neurons were found in the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus (Vmes), weak scattered Aβ-IR neurons were observed in the trigeminal motor nucleus (Vmo), trigeminal principal nucleus (Vpr), and trigeminal spinal nucleus (Vsp). Small number of Aβ-IR neurons were found in the trigeminal ganglion (TG). The sections were counterstained with cresyl violet. LC, locus coeruleus. Scale bars: A, B, E-H, 200 μm; C, D, 50 μm.

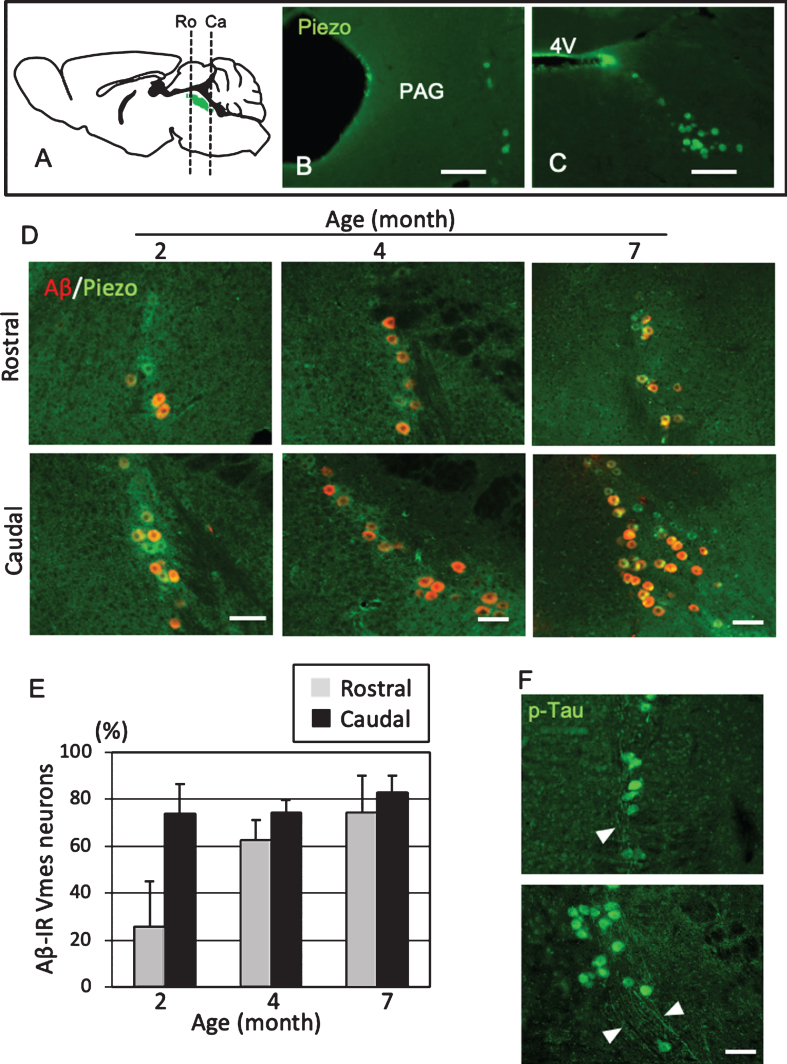

Progression of Aβ deposition in Vmes neurons in 3×Tg-AD mice

To use female 3×Tg-AD mice as a model of predementia, it was necessary to clarify when Aβ deposit appears in Vmes neurons. The level of age-related Aβ deposition in the Vmes of 2-, 4-, and 7-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice was examined. Vmes neurons were widely distributed from the vicinity of the aqueduct at the distal end of the cingulate cortex to the rostral part of the 4th ventricle (Fig. 2A). In the rostral part of the Vmes, several neurons immunoreactive for Piezo2, a marker of Vmes neurons, were distributed along the edge of the periaqueductal gray matter (Fig. 2B). In the caudal part, Piezo2-IR-neurons were spread obliquely from the lateral edge of the fourth ventricle in a triangular pyramid shape (Fig. 2C). In 2-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, 73.7% of neurons in the caudal part of the Vmes were Aβ-IR, while 25.7% of neurons in the rostral part of the Vmes were Aβ-IR. In 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, the ratio of Aβ-IR neurons in the rostral part of the Vmes reached a similar level as that in the caudal part of the Vmes (Ro, 62.5% ±8.8%; Ca, 74.1% ±5.1%). In 7-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, both the rostral and caudal parts of the Vmes showed slight increases in the ratio of Aβ-IR neurons to approximately 80% (Ro, 74.3% ±18.8%; Ca, 82.8% ±7.1%.) (Fig. 2D, E). Additionally, p-Tau-IR neurons were found in the rostral and caudal parts of the Vmes in 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, and the axons of Vmes neurons were also immunopositive for p-Tau (Fig. 2F). Based on these results, 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice were used in subsequent experiments as the state of disease progression was similar to that in the human MCI phase.

Fig.2.

Position- and age-dependent amyloid β (Aβ) deposition in Vmes neurons in 3×Tg-AD mice. A) The positions of the histological sections from the rostral (Ro) and caudal (Ca) sides of the Vmes (Green). B, C) Immunofluorescence images of Piezo2 inVmes neurons in the rostral (B) and caudal (C) regions. PAG, periaqueductal gray; 4V, 4th ventricle. D) Immunofluorescence images of Aβ and Pezo2 in the rostral (Ro) and caudal (Ca) parts of the Vmesin 2-, 4-, and 7-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice. E) Age-dependent ratios of Aβ-IR Vmes neurons in the rostral and caudal regions of the Vmes. The data are the means±SDs, n = 10. F) p-Tau-IR neurons in 7-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice. The rostral (upper) and caudal (lower) parts of Vmes. The arrowheads indicate p-Tau-IR axons of Vmes neurons. Scale bars: B, C, 200μm; D, F, 50μm.

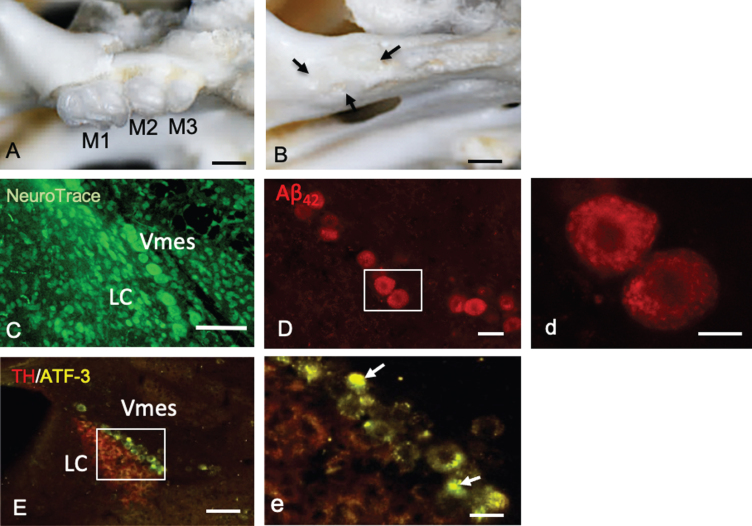

Vmes neurons and microglia after tooth extraction

Mice had three molars (M1–M3) bilaterally in the maxilla (Fig. 3A). One month after maxillary molar extraction, the sockets of the teeth were covered by new bone (Fig. 3B). In female 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, LC neurons were observed along edge of the caudal part of the Vmes (Fig. 3C). Before tooth extraction, Vmes neurons in 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice were strongly immunopositive for cytotoxic Aβ42, as determined using a mouse anti-Aβ42 (BC05) antibody (Fig. 3D). By high-power magnified fluorescence imaging, Aβ42 immunopositivity was observed in granular structures in Vmes neurons (Fig. 3d, rectangular area in D).

Fig.3.

Tooth extraction and damage to Vmes neurons. A, B) The maxillary first to third molars (M1–M3) of 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice and the sockets of the roots were covered by new bone (arrows) 1 month after tooth extraction. C) Fluorescence images of the Vmes and LC stained with Neuro Trace green. LC, locus coeruleus. D) In 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, before tooth extraction, amyloid β1–42 (Aβ42)-IR neurons in the Vmes were found using an anti-Aβ42 antibody (BC05) and Aβ42-IR granules were distributed in Vmes neurons (d, rectangle in D). E) Fluorescence images of the Vmes and LC immunostained for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)/ATF3 at 2 weeks after tooth extraction. In addition to the TH immunoreactivity in the LC, some nuclei of Vmes neurons showed ATF3 immunoreactivity (arrows) (d, rectangle in D). Scale bars: A, B, 1 mm; C, E, 100μm; D, 30μm; d, 10μm, e, 20μm.

Two weeks after tooth extraction, ATF-3-IR nuclei in Vmes neurons were found close to TH-IR LC neurons, indicating that Vmes neuronal damage was transferred from nerve endings at periodontal ligaments to the soma of Vmes neurons through the extraction of the maxillary molars (Fig. 3E, e).

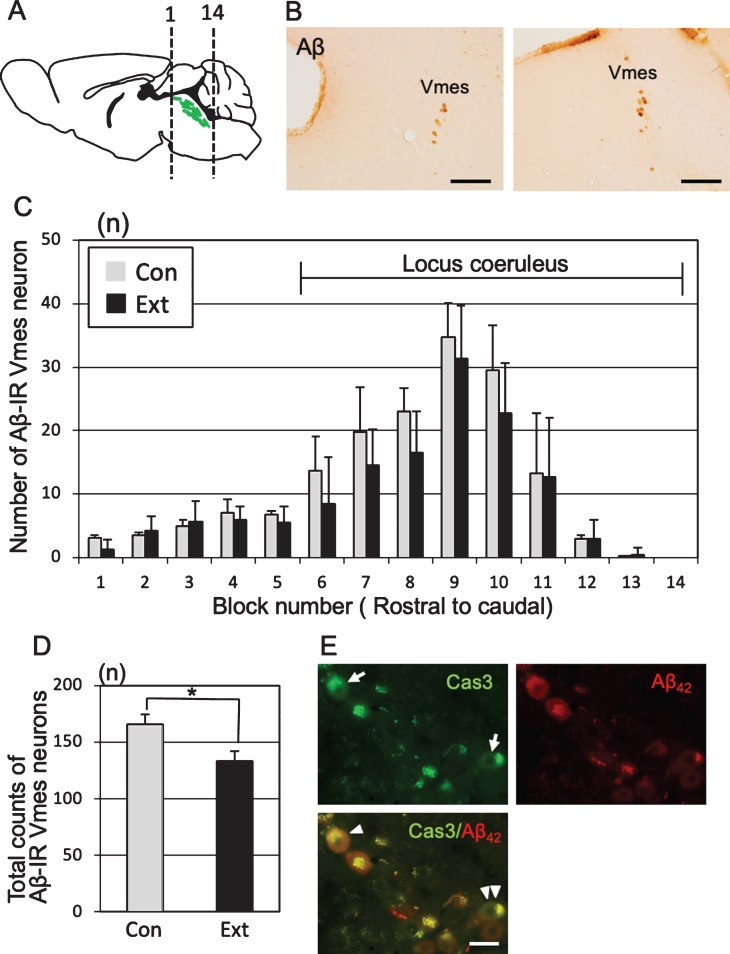

Loss of Vmes neurons after tooth extraction

One month after tooth extraction, the number of Aβ-IR Vmes neurons in a section of each block was examined (Fig. 4A). Control specimens were obtained from age-matched (5-month-old) 3×Tg-AD mice that did not undergo tooth extraction. The Vmes was equally divided into 14 blocks along the rostro-caudal axis, and the number of Aβ-IR Vmes neurons in a section of each block was determined. The sections were visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Fig. 4B). After tooth extraction, the number of Vmes neurons was reduced in blocks 6 to 11, whereas Vmes neurons were localized close to LC neurons in the blocks 9 to 14 (Fig. 4C). The number of Vmes neurons in the control and extraction groups was significantly different (two-way ANOVA, p = 0.002). The total number of Vmes neurons was significantly reduced after tooth extraction (t-test, p = 0.003; Fig. 4D). Furthermore, we confirmed degeneration of Vmes neurons after tooth extraction using cleaved caspase-3 immunocytochemistry and found a cleaved caspase-3/Aβ42-IR neuron in the Vmes at 10 days after tooth extraction (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, we found cleaved caspase-3-IR but Aβ42-immunonegative Vmes neurons in the same section, which means that the intracellular deposition of Aβ42 in Vmes neurons is not always necessary for the death of Vmes neurons after tooth extraction.

Fig.4.

Neuronal loss in the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus (Vmes) after tooth extraction. A) The positions of the histological blocks from the rostral (1) and caudal (14) ends of the Vmes (green). B) Immunocytochemical localization of Aβ (6E10)-IR Vmes neurons in the rostral (left, block #3) and caudal (right, block #10) regions in 5-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice. C) The number of Vmes neurons in each block from rostral (1) to the caudal (14) ends of the Vmes in 5-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice without tooth extraction (Con, control) and with extraction (Ext, 1 month after extraction). Blocks 6–14 from the Vmes were adjacent to the locus coeruleus. D) The total number of Vmes neurons in 14 sections from each 5-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice in the Con and Ext groups. The data are the means±SDs, n = 10. *p < 0.01, unpaired t test. E) Cleaved caspase-3-IR Vmes neurons (arrows), Aβ42-IR Vmes neurons, and cleaved caspase-3-/Aβ42-IR Vmes neuron (arrowhead) and a cleaved caspase-3-IR but Aβ42-immunonegative Vmes neuron (double arrowheads) 10 days after tooth extraction in 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice. Scale bars: B, 200μm; E, 20μm.

Neurodegeneration of Vmes neurons and the activation of microglia after tooth extraction

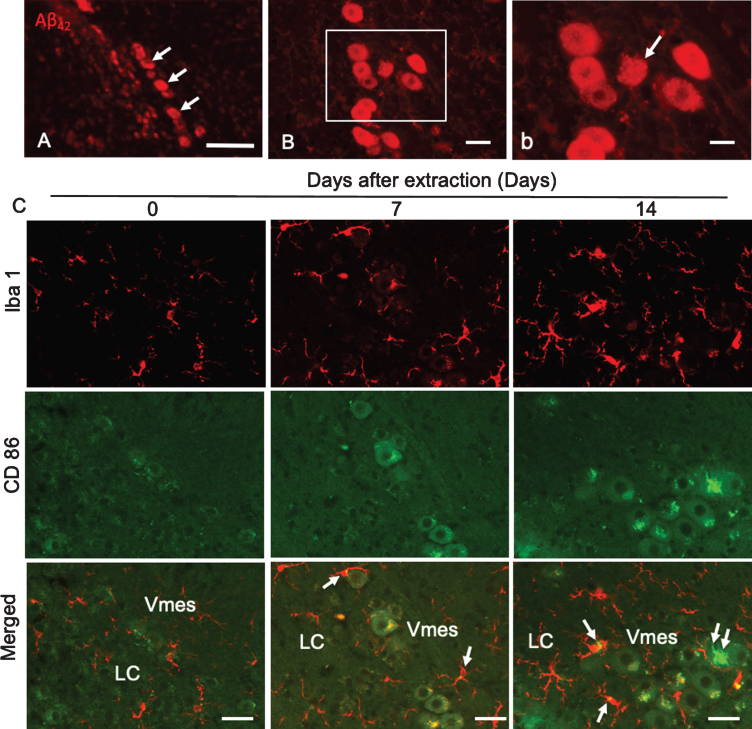

Aβ42 deposition was found in neurons in the caudal part of the Vmes in 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice (Fig. 5A). Two weeks after tooth extraction, Aβ42-IR neurons with unclear cell membranes were observed (Fig. 5B, b), indicating that the extracellular diffusion of Aβ42 occurred after the death of Aβ42-IR Vmes neurons. One and two weeks after tooth extraction, the number of Iba 1-IR microglia on the caudal side of the Vmes and LC increased, and many were larger than those in the controls (Fig. 5C). As the number of CD86-IR microglia is known to be increased in the presence of cytotoxic Aβ42 [28], CD86-IR microglias were also observed in this study, whereas Vmes neurons were thought to be dead and Aβ was found to be diffuse. CD86-IR and Iba 1 immunonegative cell was observed on Vmes neuron.

Fig.5.

Degeneration of Vmes neurons and the activation of microglia after tooth extraction. A) Aβ42 (BC05)-IR Vmes neurons (arrows) in 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice. B) Two weeks after tooth extraction a damaged Aβ42-IR neuron with an unclear cell membrane was observed. b) A higher magnification image of the rectangular area in (B). C) Immunofluorescence images of CD86-IR and Iba1-IR microglia after tooth extraction. Immunofluorescence images of microglia in the Vmes and LC at 0 (Con), 7, and 14 days after tooth extraction. Immunofluorescence images of Iba1-IR, and CD86-IR cells and merged images. The arrows indicate Iba1+/CD86+ microglia. Double arrows indicate an Iba1–/CD86+ cell. Scale bars: A, 100μm; B, 30μm; b, 10μm; C, 50μm.

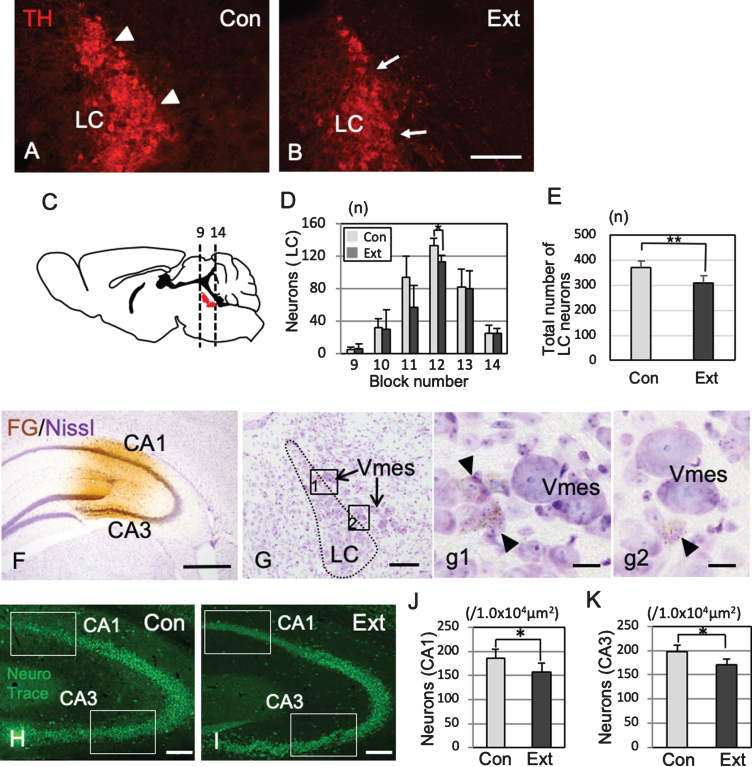

LC neurons and hippocampal neurons after tooth extraction

TH-IR neurons in the LC nucleus were found on the ventral side of the Vmes in rectilinear contact with Vmes neurons (Fig. 6A). One month after tooth extraction, TH-IR neurons was in irregular contact with Vmes neurons (Fig. 6B), and the number of LC neurons in sections from blocks 9 to 14 was examined (Fig. 6C). The number of TH-IR LC neurons decreased significantly from the center to the rostral side (two-way ANOVA, p = 0.027), and a significant difference was found at the center of the LC (Tukey’s post hoc analysis, p = 0.034; Fig. 6D). The total number of LC neurons was significantly different between the control and extraction groups (t test, p = 0.007, Fig. 6E). After the injection of FG into the hippocampus (Fig. 6F), retrograde labeling of FG was found in the LC neurons close to the central and caudal parts of the Vmes (Fig. 6G, g1,g2). The number of hippocampal neurons in the CA1 and CA3 regions in 3×Tg-AD mice at one month after tooth extraction (H) and in sham-operated mice was investigated (Fig. 6H) and were significantly reduced in both the CA1 and CA3 regions after tooth extraction (CA1, t test, p = 3.7×10–5, Fig. 6I; CA3, t test, p = 0.0014, Fig. 6J).

Fig.6.

Association of neuronal loss between the LC and hippocampus after tooth extraction. A, B) Immunofluorescence images of TH-IR LC neurons in 5-month-old control 3×Tg-AD mice (Con) and 5-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice (1 month after tooth extraction) (Ext). The LC neurons linearly contact with the Vmes (arrowheads) (A), whereas irregularly contacts the Vmes (arrows) after tooth extraction (B). C) The number of LC neurons (red) in each block from the rostral (9) to caudal (14) ends of the Vmes. The block positions are the same as in Fig. 3. D) The number of LC neurons in each block from the rostral (9) to caudal (14) ends of the LC in 5-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice in the Con and Ext groups. The data are the means±SDs, n = 6. *p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis. **p < 0.01, unpaired t test. E) The total number of LC neurons in 5-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice in the Con and Ext groups. The data are the means±SDs, n = 10. *p < 0.01, unpaired t test. F) Fluorogold labeling was visualized with DAB in the CA1 and CA3 regions of the hippocampus. Nissl staining with 0.1% cresyl violet was used to visualize neurons. G) Retrograde labeling of the LC close to the Vmes. g1, 2) Higher magnification images of the rectangle in (G). Fluorogold labeling in LC neurons (arrowheads). H, I) The position of the measured area (rectangular area) was in the CA1 and CA3 regions of the hippocampus in 7-month-old control 3×Tg-AD mice without tooth extraction (Con) (H) and 3×Tg-AD mice with tooth extraction (Ext) (I). Neuro Trace green staining. J, K) The number of neurons in the CA1 (J) and CA3 (K) regions of the hippocampus in 7-month-old control 3×Tg-AD mice without tooth extraction (Con) and 3×Tg-AD mice with tooth extraction (Ext). The data are the means±SDs, n = 10. *p < 0.01, unpaired t test. Scale bars: B, F, H, I, 500μm; G, 200μm; g1, g2, 10μm.

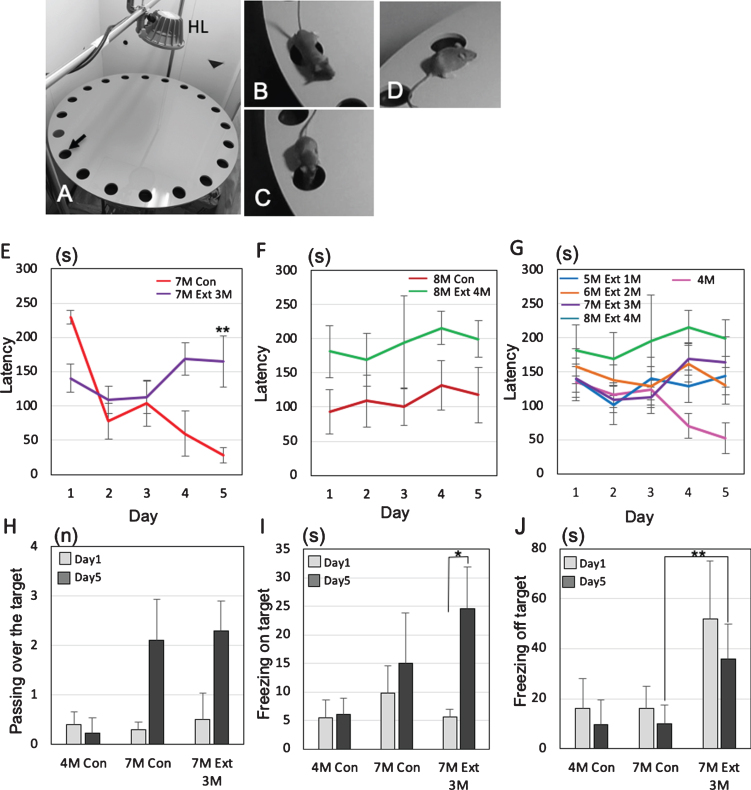

Behavioral changes observed after tooth extraction

Finally, we performed the Barnes maze experiments to assess how tooth loss affects the cognitive functions of female 3×Tg-AD mice (Fig. 7A). No significant differences in body weight were observed between the control group and the tooth extraction group (Supplementary Figure 2). To identify the changes in behavior between mild and progressed dementia in 3×Tg-AD mice, the latency to escape into the target, the number of passes through the target (Fig. 7B), the freezing time on the target (Fig. 7C), and the freezing time off the target (i.e., on the wrong hole) (Fig. 7D) were investigated. In 7-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, sham mice showed that the latency to escape into the target decreased gradually from day 1 to day 5, while tooth extracted mice did not show the decrease from day 1 to day 5. On the 5th day, a significant difference in latency was observed between the sham group and the tooth extraction group (Tukey’s post hoc analysis; day 5, p = 0.0031: Fig. 7E). In 8-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, no decreases in latency between day 1 and day 5 were found in both sham and tooth extraction groups (Fig. 7F). A significant increase in latency was generally observed in the extracted group compared to the sham group (two-way ANOVA, p = 0.0004). Assuming that the behavior pattern of dementia in mice does not decrease latency, it was considered that the control was pre-dementia up to 7-month-old and the dementia stage from 8-month-old.

Fig.7.

Effects of tooth extraction on the behavioral performance in 3×Tg-AD mice. All tooth extracted 3×-Tg-AD mice had the operation at the age of 4-month-old. A-D) The Barnes maze system. HL, halogen light. The arrow indicates the target hole (A), representative photographs showing passing over the target (B), freezing on the target (C), and freezing off the target (D). E–G) The latency(s) to locate the escape hole is plotted. A trial ended when the mouse found the escape box or 3 min had elapsed. The changes of average latency (s) from day 1 to day 5, comparing to sham 3×Tg-AD mice (no tooth extraction) and the 3×Tg-AD mice that underwent tooth extraction. Graphs shows the comparisons of latency in 7-month-old (E) and 8-month-old (F) 3×Tg-AD mice with and without tooth extraction on days 1 to 5. The changes of latency after the tooth extraction are shown in (G). The data are the means±SEMs, n = 10. **p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis. H–J) The effects of tooth extraction on the number of passes over the target (H), total time of on-target freezing (I), and total time of off-target freezing (J) on days 1 and 5. The data are the means±SDs, n = 10. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis.

From 1 to 4 months after tooth extraction, the latency to escape into the target of all tooth-extracted mice increased gradually on day 5 (Fig. 7G). In the extracted group, a pattern of dementia stage was already observed at 5-month-old, 1 month after the tooth extraction. In 7-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, the number of passes over the target increased on day 5 compared with day 1 in both the control and extraction groups, but the difference was not significant (Tukey’s post hoc analysis; day 1, p = 0.69, day 5, p = 0.84; Fig. 7H). Interestingly, 3×Tg-AD mice in the tooth extraction group showed a significantly longer on-target freezing time even on day 5 compared with day 1 (Tukey’s post hoc analysis, p = 0.033; Fig. 5I). The off-target freezing time of 7-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice on day 5 was significantly longer in the extraction group than in the control group (Tukey’s post hoc analysis, p = 2.5×10–4; Fig. 5J).

DISCUSSION

The progression of AD requires both aging, which is the greatest risk factor, and other triggers. In this study, we focused on Aβ deposition in neurons due to aging, and the neurodegeneration of Vmes neurons resulting from tooth extraction as triggers. The results of pathological analyses provided evidence for the induction of neurodegeneration, the deposition of cytotoxic Aβ42, and the activation of microglia in Vmes neurons due to tooth loss in 3×Tg-AD mice. The loss of neurons in the Vmes was associated with loss of LC neurons and even the loss of hippocampal neurons. All of these events resulted in the acceleration of the onset of dementia-like behavior.

The initiation of human MCI is characterized by a plateau in the deposition of Aβ in the CNS [21]; thus, it was necessary to examine the deposition of Aβ in 3×Tg-AD mice, as the genetic alterations in each AD model mouse line can be very different. Initially, Aβ is deposited in neurons rather than as amyloid plaques [29, 30], and the deposition time of Aβ differs between neuronal populations. Therefore, it is important to determine which neurons should be used as the baseline. There are three sensory trigeminal nuclei, i.e., the trigeminal mesencephalic, principal, and spinal trigeminal nuclei. Our results showed that Aβ was deposited earliest and strongest in Vmes neurons among neurons in the three sensory trigeminal nuclei of 3×Tg-AD mice. Consistent with our findings, a previous study showed that Aβ deposition begins on Vmes neurons in 2-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice [23]. In the present study, the deposition of Aβ in rostral Vmes neurons also reached a high level similar to that in the caudal region in 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice. In addition, the ratio of Aβ between these two regions reached a plateau between 4 and 7 months of age. Therefore, we used 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice as an experimental model of the predementia state and performed tooth extraction in these animals.

In human AD, Aβ peptides are known to exist in various forms, among which Aβ42 is known to be a highly toxic subtype [31, 32]. In terms of Aβ cytotoxicity, the aggregation of Aβ42 in neurons is toxic to neurons [33]. Granules containing Aβ42 were also observed in Vmes neurons in 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice. Although it is not well understood where in the cell membrane APP is processed to produce Aβ, especially highly cytotoxic Aβ42, our findings suggest that Aβ42 is produced in the granules of neurons. According to the recently proposed traffic jam theory [34], aging attenuates dynein dysfunction reproduces age-dependent endocytic disturbances, resulting in the intracellular accumulation of AβPP and its β-cleavage products in neurons in cynomolgus monkeys. Another study reported that kinesin phosphorylation is involved in AβPP processing [35]. In 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, most of Vmes neurons possessed strong Aβ42-IR vesicles: however, we did not observe any abnormal behavior at this age, which suggests that the accumulation of Aβ42-IR granules in neurons itself is not a trigger for the progression of AD.

The Vmes is not only the area where Aβ shows the earliest and strongest deposition among the trigeminal nuclei in 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice [31] but also the region where neurons can sense stress from the periodontal ligament. Vmes neurons project to the periodontal ligament, and tooth extraction causes degeneration of the nerve endings of Vmes neuron [36]. After tooth extraction, ATF3 immunoreactivity was found in some Vmes neurons adjacent to the LC. The presence of ATF3 immunoreactivity in Vmes neurons was considered to be the result of damage responses due to the extraction of maxillary molars. Indeed, damage to Vmes neurons by peripheral nerve transection has been reported [6]. The results of the present study revealed cell death in Aβ42-IR Vmes neurons 2 weeks after tooth extraction. These findings suggested that extracting the molars of 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice leads to damage to Vmes neurons, resulting in the release of cytotoxic Aβ42 peptides into the extracellular space. Interestingly, we found cleaved caspase-3-IR but Aβ42-immunonegative Vmes neurons in the same section, which means that the intracellular deposition of Aβ42 in Vmes neurons is not always necessary for the neuronal death of Vmes neurons after tooth extraction. An increase in the number of activated microglia was found in the Vmes and LC 1–2 weeks after tooth extraction. Most of the microglia were immunonegative for CD86, which is a marker of M1 polarity. However, some microglia adjacent to the Vmes were positive for CD86, possibly due to the release of Aβ42 peptide in this brain region as a result of the death of Vmes neurons. As M1 microglia are involved in the removal of amyloid plaques and the initiation of proinflammatory responses [37], the presence of M1 microglia in the Vmes and LC may be another factor that facilitates the spread of neurodegeneration to the hippocampus. CD86+/Iba1– cells were also observed, it may be active astrocyte, but further study is needed about this type of cell.

The LC is located adjacent to the Vmes in the brainstem. As the Vmes is involved in occlusion and chewing [4], it has been suggested that there is some interaction between the Vmes and LC. However, axons projecting from the Vmes to the LC have scarcely been found [38]. In this study, the release of cytotoxic Aβ peptides due to the death of Vmes neurons triggered by tooth loss, may have played an important role in how the Vmes affected LC neurons. These findings suggest that the effects of Vmes neurons on LC neurons are not caused by the loss of neuronal connections but by the cytotoxic effects of Aβ42 released from degenerated Vmes neurons.

Early neurodegeneration has been reported to occur in the olfactory area, basal nucleus of Meynert, and LC during the development of dementia in humans [39]. Of these, only the LC is directly involved in the trigeminal nervous system. In addition, the LC projects axons to many areas and plays an important role as a central noradrenaline producer, and damage to the LC is known to affect hippocampal function directly [40]. As norepinephrine protects against amyloid-induced toxicity via the activation of cAMP/PKA signaling pathway by beta-adrenergic receptors. [41, 42], the loss of norepinephrine in the LC might induce neuronal cell death in the hippocampus. In this study, FG was injected into the CA1 and CA3 regions of the hippocampus, and axonal projections in the LC were found to be close to the Vmes. In our experiments, as in a previous report [20], a significant decrease in the number of hippocampal neurons after tooth extraction was confirmed.

It is not easy to judge by behavioral tests whether mice ultimately experience dementia. A previous study reported that human MCI stage and AD correspond to stages of moderate and severe impairment, respectively [43]. A number of behavioral tests, such as the Morris water maze [44], Y-maze test [45], and Barnes maze test [46], have been used to determine the stage of dementia, however, some behavioral tests seem too stressful to mice to be used to examine changes in cognitive function. The Barnes maze has been reported to be the most sensitive test for detecting these cognitive deficits in 3×Tg-AD mice [27]. Furthermore, memory deficits have been observed in 3×Tg-AD mice using a modified Barnes maze protocol [48]. In our study, we used 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice in which the neuronal deposition of Aβ had reached a plateau as a predementia model and to compensate for latency analysis, we measured the number of passes over the target, freezing time on the target, and freezing time off the target. Our results of modified Barnes maze analysis showed a gradual decrease in the latency for the mice to escape into the target box from day 1 to day 5 in the control group until 7 months of age, whereas 8-month-old mice did not show the decrease in the latency. The increased latency observed in 8-month-old mice was also observed in 5-month-old mice 1 month after tooth extraction, and the average latency increased according to the time after tooth extraction. Based on our protocol, we found that the progression of dementia was associated with increased latency, and off-target freezing and on-target freezing. Furthermore, there was a tendency toward dementia in 8-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice that did not undergo tooth extraction, whereas 1 month after tooth extraction, the progression of dementia had already occurred.

In our study, the neurodegeneration cascade triggered by tooth extraction was shown to accelerate the onset of dementia-like behavior in 3×Tg-AD mice. Applying these findings to humans suggests that the loss of teeth in elderly people who already have Aβ deposition in Vmes neurons may accelerate the progression to dementia. Periodontal disease has been suggested as a risk factor of AD in the elderly, and the effects of bacterial toxins due to periodontal disease and masticatory disorders due to tooth loss following periodontal disease have been pointed out. Here we demonstrated that neurodegeneration during tooth loss could directly trigger neuronal loss in the hippocampus. Regardless tooth loss due to periodontal disease or surgical tooth extraction, we suggest that tooth loss in the elderly may accelerate the progression of AD. Further research is needed on the relationship between the timing of tooth extraction and progression of dementia in the elderly. In addition, patients with Down’s syndrome or familial AD patients have Aβ deposition even when they are young [48]; therefore, a high standard of oral health should be maintained to prevent tooth loss and thus prevent the acceleration of dementia in such patients.

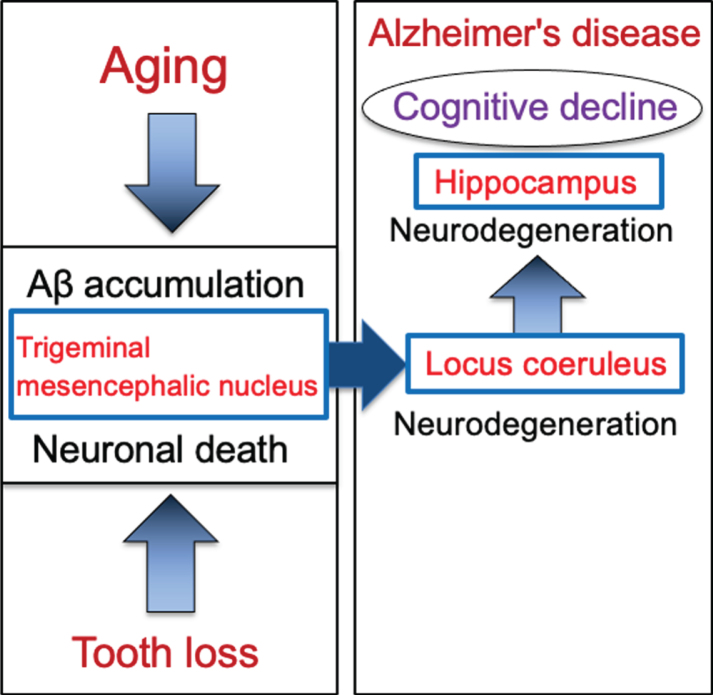

Based on evidences that the loss of teeth causes neurodegeneration in the Vmes neurons, the involvement of the LC in the initial development of dementia was examined by performing tooth extraction when cytotoxic Aβ42 was sufficiently accumulated in Vmes neurons. In 4-month-old 3×Tg-AD mice, aggregated cytotoxic Aβ42 was found in granules in Vmes neurons. Neuronal death in the Vmes occurred after tooth extraction, resulting in the release of Aβ42 and an increase in activated microglia. Released Aβ42 damaged LC, and then induced a significant reduction in hippocampal neurons receiving projections from the LC. Measures of cognitive deficits using the Barnes maze revealed an earlier shift toward dementia-like behavior after tooth extraction. The cascade of neurodegeneration from tooth loss to the progression of AD is summarized in Fig. 8. These findings suggest that tooth extraction in predementia stage can trigger spread of neurodegeneration from the Vmes to the LC and hippocampus and accelerate the onset of dementia-like behavior.

Fig.8.

Schematic to show the cascade from tooth loss to the progression of Alzheimer’s disease via the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus, locus coeruleus, and hippocampus. Aging leads to increase the intracellular Aβ accumulation in trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus (Vmes) neurons, and tooth loss leads to Vmes neuronal death. Release of Aβ by Vmes neuronal death causes neurodegeneration of adjacent locus coeruleus (LC) neurons, resulting in neuronal degeneration of hippocampal neurons that the LC neurons project. This neurodegenerative cascade of Vmes, LC and hippocampus accelerates the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Frank LaFerla (University of California, Irvine) for originally providing breeding pairs of 3×Tg-AD mice to Dr. Y. Ohyagi who is a coauthor of the manuscript. This research was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for challenging Exploratory Research (17K19772, to Goto), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (16K09680 to Matsumoto, 19K10058 to Kuramoto, 20K10296 to Goto), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas, “Brain Information Dynamics” (17H06311 to Kuramoto) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, and the Akaeda Medical Research Foundation (to Kuramoto).

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/20-0257r2).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200257.

REFERENCES

- [1]. Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MM, de Strooper B, Frisoni GB, Salloway S, Van der Flier WM (2016) Alzheimer’s diseas. Lancet 388,, 505–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Mather M, Harley CW (2016) The locus coeruleus: Essential for maintaining cognitive function and the aging brai. Trends Cogn Sci 20, 214–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Theofilas P, Ehrenberg AJ, Dunlop S, Di Lorenzo Alho AT, Nguy A, Leite REP, Rodriguez RD, Mejia MB, Suemoto CK, Ferretti-Rebustini REL, Polichiso L, Nascimento CF, Seeley WW, Nitrini R, Pasqualucci CA, Jacob Filho W, Rueb U, Neuhaus J, Heinsen H, Grinberg LT (2017) Locus coeruleus volume and cell population changes during Alzheimer’s disease progression: A stereological study in human postmortem brains with potential implication for early-stage biomarker discover. Alzheimers Dement 13, 236–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Takahashi T, Shirasu M, Shirasu M, Kubo KY, Onozuka M, Sato S, Itoh K, Nakamura H (2010) The locus coeruleus projects to the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus in rat. Neurosci Res 68, 103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Linden RW, Scott BJ (1989. a) Distribution of mesencephalic nucleus and trigeminal ganglion mechanoreceptors in the periodontal ligament of the ca. J Physiol 410, 35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Raappana P, Arvidsso J (1992) The reaction of mesencephalic trigeminal neurons to peripheral nerve transection in the adult ra. Exp Brain Res 90, 567–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Linden RW, Scott BJ (1989) The effect of tooth extraction on periodontal ligament mechanoreceptors represented in the mesencephalic nucleus of the ca. Arch Oral Biol 34, 937–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Delwel S, Binnekade TT, Perez RSGM, Hertogh CMPM, Scherder EJ, Lobbezoo F (2018) Oral hygiene and oral health in older people with dementia: A comprehensive review with focus on oral soft tissue. Clin Oral Investig 22, 93–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Fereshtehnejad SM, Garcia-Ptacek S, Religa D, Holmer J, Buhlin K, Eriksdotter M, Sandborgh-Englund G (2018) Dental care utilization in patients with different types of dementia: A longitudinal nationwide study of 58,037 individual. Alzheimers Dement 14, 10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Grabe HJ, Schwahn C, Völzke H, Spitzer C, Freyberger HJ, John U, Mundt T, Biffar R, Kocher T (2009) Tooth loss and cognitive impairmen. J Clin Periodontol 36, 550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Kato H, Takahashi Y, Iseki C, Igari R, Sato H, Sato H, Koyama S, Tobita M, Kawanami T, Iino M, Ishizawa K, Kato T (2019) Tooth loss-associated cognitive impairment in the elderly: A community-based study in Japa. Intern Med 58, 1411–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Luo J, Wu B, Zhao Q, Guo Q, Meng H, Yu L, Zheng L, Hong Z, Ding D (2015) Association between tooth loss and cognitive function among 3063 Chinese older adults: A community-based stud. PLoS One 10, e0120986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Yoo JJ, Yoon JH, Kang MJ, Kim M, Oh N (2019) The effect of missing teeth on dementia in older people: A nationwide population-based cohort study in South Kore. BMC Oral Health 19, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Takeuchi K, Ohara T, Furuta M, Takeshita T, Shibata Y, Hata J, Yoshida D, Yamashita Y, Ninomiya T (2017) Tooth loss and risk of dementia in the community: The Hisayama Stud. J Am Geriatr Soc 65, e95–e100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Kamer AR, Craig RG, Dasanayake AP, Brys M, Glodzik-Sobanska L, de Leon MJ (2008) Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease: Possible role of periodontal diseases. Alzheimers Dement 4, 242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Noble JM, Scarmeas N, Papapanou PN (2013) Poor oral health as a chronic, potentially modifiable dementia risk factor: Review of the literatur. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 13, 384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F, Benedyk M, Marczyk A, Konradi A, Nguyen M, Haditsch U, Raha D, Griffin C, Holsinger LJ, Arastu-Kapur S, Kaba S, Lee A, Ryder MI, Potempa B, Mydel P, Hellvard A, Adamowicz K, Hasturk H, Walker GD, Reynolds EC, Faull RLM, Curtis MA, Dragunow M, Potempa J (2019) Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv 5, eaau3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Lexomboon D, Trulsson M, Wårdh I, Parker MG (2012) Chewing ability and tooth loss: Association with cognitive impairment in an elderly population stud. J Am Geriatr Soc 60, 1951–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Weijenberg RA, Scherder E, Lobbezoo F (2011) Mastication for the mind—the relationship between mastication and cognition in ageing and dementia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35, 483–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Oue H, Miyamoto Y, Okada S, Koretake K, Jung CG, Michikawa M, Akagawa Y (2013) Tooth loss induces memory impairment and neuronal cell loss in APP transgenic mic. Behav Brain Res 252, 318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Sperling RA, Aisen S, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH (2011) Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s diseas. Alzheimers Dement 7, 280–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Koistinaho M, Ort M, Cimadevilla JM, Vondrous R, Cordell B, Koistinaho J, Bures J, Higgins S (2001) Specific spatial learning deficits become severe with age in beta-amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice that harbor diffuse beta -amyloid deposits but do not form plaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 14675–14680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Overk CR, Kelley CM, Mufson EJ (2009) Brainstem Alzheimer’s-like pathology in the triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s diseas. Neurobiol Dis 35, 415–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Bero AW, Yan P, Roh JH, Cirrito JR, Stewart FR, Raichle ME, Lee JM, Holtzman DM (2011) Neuronal activity regulates the regional vulnerability to amyloid-β depositio. Nat Neurosci 14, 750–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM (2003) Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: Intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunctio. Neuron 39, 409–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Kurihara Y, Takechi M, Kurosaki K, Kobayashi Y, Kurosaw T (2013) Anesthetic effects of a mixture of medetomidine, midazolam and butorphanol in two strains of mic. Exp Anim 62, 173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Stover KR, Campbell MA, Van Winssen CM, Brown RE (2015) Early detection of cognitive deficits in the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s diseas. Behav Brain Res 289, 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Caldeira C, Cunha C, Vaz AR, Falcão AS, Barateiro A, Seixas E, Fernandes A, Brites D (2017) Key aging-associated alterations in primary microglia response to beta-amyloid stimulatio. Front Aging Neurosci 9, 277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Iulita MF, Allard S, Richter L, Munter LM, Ducatenzeiler A, Weise C, Do Carmo S, Klein WL, Multhaup G, Cuello AC (2014) Intracellular Aβ pathology and early cognitive impairments in a transgenic rat overexpressing human amyloid precursor protein: A multidimensional study. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Mukhin VN, Pavlov KI, Klimenko VM (2017) Mechanisms of neuron loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Behav Physiol 47, 508–516. [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Gao ZY, Collins H, Matschinsky FM, Lee VM, Wolf BA (1998) Cytotoxic effect of beta-amyloid on a human differentiated neuron is not mediated by cytoplasmic Ca2+ accumulatio. J Neurochem 70, 1394–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Yang AJ, Knauer M, Burdick DA, Glabe C (1995) Intracellular A beta 1-42 aggregates stimulate the accumulation of stable, insoluble amyloidogenic fragments of the amyloid precursor protein in transfected cell. J Biol Chem 270, 14786–14792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Jonson M, Nyström S, Sandberg A, Carlback M, Michno W, Hanrieder J, Starkenberg A, Nilsson KPR, Thor S, Hammarström P (2018) Aggregated Aβ1-42 is selectively toxic for neurons, whereas glial cells produce mature fibrils with low toxicity in Drosophil. Cell Chem Biol 25, 595–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Kimura N, Samura E, Suzuki K, Okabayashi S, Shimozawa N, Yasutomi Y (2016) Dynein dysfunction reproduces age-dependent retromer deficiency: Concomitant disruption of retrograde trafficking is required for alteration in β-amyloid precursor protein metabolis. Am J Pathol 186, 1952–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Mórotz GM, Glennon EB, Greig J, Lau DHW, Bhembre N, Mattedi F, Muschalik N, Noble W, Vagnoni A, Miller CCJ (2019) Kinesin light chain-1 serine-460 phosphorylation is altered in Alzheimer’s disease and regulates axonal transport and processing of the amyloid precursor protei. Acta Neuropathol Commun 7, 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Muramoto T, Takano Y, Soma K (2000) Time-related changes in periodontal mechanoreceptors in rat molars after the loss of occlusal stimul. Arch Histol Cytol 63, 369–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Tang Y, Le W (2016) Differential roles of M1 and M2 microglia in neurodegenerative disease. Mol Neurobiol 53, 1181–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Iida C, Oka A, Moritani M, Kato T, Haque T, Sato F, Nakamura M, Uchino K, Seki S, Bae YC, Takada K, Yoshida A (2010) Corticofugal direct projections to primary afferent neurons in the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus of rats. Neuroscience 169, 1739–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Arendt T, Brückner MK, Morawski M, Jäger C, Gertz HJ (2015) Early neurone loss in Alzheimer’s disease: Cortical or subcortical. Acta Neuropathol Commun 3, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Kelly SC, He B, Perez SE, Ginsberg SD, Mufson EJ, Counts SE (2017) Locus coeruleus cellular and molecular pathology during the progression of Alzheimer’s diseas. Acta Neuropathol Commun 5, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Counts SE, Mufson EJ (2010) Noradrenaline activation of neurotrophic pathways protects against neuronal amyloid toxicit. J Neurochem 113, 649–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Liu X, Ye K, Weinshenker D (2015) Norepinephrine protects against amyloid-β toxicity via Trk. J Alzheimers Dis 44, 251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Webster SJ, Bachstetter AD, Nelson PT, Schmitt FA, Van Eldik LJ (2014) Using mice to model Alzheimer’s dementia: An overview of the clinical disease and the preclinical behavioral changes in 10 mouse model. Front Genet 5, 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Morris R (1984) Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Methods 11, 47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Ranje C, Ungerstedt U (1977) Lack of acquisition in dopamine denervated animals tested in an underwater Y-maz. Brain Res 134, 95–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Barnes CA (1979) Memory deficits associated with senescence: A neurophysiological and behavioral study in the ra. J Comp Physiol Psychol 93, 74–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Attar A, Liu T, Chan WT, Hayes J, Nejad M, Lei K, Bitan G (2013) A shortened Barnes maze protocol reveals memory deficits at 4-months of age in the triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 8, e80355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Tcw J, Goate AM (2017) Genetics of β-amyloid precursor protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 7, a024539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.