Abstract

The present COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus, has highlighted the vital importance of appropriate personal protective equipment for all exposed health care workers. The single most important part of this armor is the N-95 mask. With the awareness that the virus is spread by both droplets and through the aerosolized route, the N-95 provides protection that a surgical mask cannot match. This timely review looks at the special advantages that an N-95 offers over a surgical mask with specific reference to the COVID-19 epidemic. It also emphasizes the crucial importance of ensuring quality masks with a proper fit. Finally, with acute scarcities of N-95 masks being reported from hospitals globally, it reviews recent literature which attempts to prolong the life of these masks with extended use, reuse and decontamination of used masks.

KEY WORDS: Decontamination measures, extended use, N-95 mask, personal protective equipment

“We can't stop COVID-19 without protecting our health workers,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World health Organization.

“In the pandemic economy, face masks are like bars of gold. Hoarders are hoarding them. Governors are bartering for them. Hospital workers desperately need them.” Michael Schulman. New Yorker.

INTRODUCTION

A humble mask which most health-care workers (HCWs) had taken for granted, or were unfamiliar with, has emerged at the forefront of the medical profession's battle against the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes the clinical syndrome of COVID-19 pneumonia.

China normally makes 10 million masks per day, about half of the world production. During the 2019–2020 coronavirus pandemic, 2500 factories were converted to step up production to 116 million daily according to the latest numbers released late last month by China's National Development and Reform Commission.[1] Even this increased number is proving grossly inadequate, a reflection of the sheer scale and intensity of the pandemic.

Shortages of this vital piece of personal protective equipment (PPE) have contributed to the deaths of some of the 600 HCWs across the globe who have been known to have succumbed to this virus whilst caring for their patients. The sheer scale of the pandemic and the vast numbers of patients needing hospitalization have exposed the state of unpreparedness in hospitals across most of the developing world. Nursing unions and medical bodies have threatened to strike because their front line HCWs are often not supplied with N-95 masks primarily because of shortages.[2] Prime ministers and governments are embarrassed and apologize for not having the foresight to ensure adequate numbers for their HCWs, thus exposing them to unacceptable risks. Unedifying spectacles of countries actually fighting over them and governments caught off guard because of the unavailability of these masks are common. In an incident that hinted of “modern piracy” a consignment of 200,000 N-95 masks meant for Germany was diverted to the US as they were being transferred between planes in Thailand.[3]

This article aims to provide a timely review of the N-95 mask.

WHAT IS AN N-95 AND WHAT DOES IT DO?

An N-95 respirator (mask) is a respiratory protective device designed to achieve a very close facial fit and efficient filtration of airborne particles. In contrast to surgical face masks, which provide only one-way protection to HCWs (by capturing their own droplets and protecting those around), N-95 respirators are tightly fitting masks that seal off the wearer's face and work in a bidirectional sense, in particular for the protection of the wearer.[4] When properly fitted, selected, used, and maintained, particulate-removing respirators have been demonstrated to reduce the amount of aerosols that are inhaled.[5]

The N-95 mask (American classification system) is so-called because it can remove 95% of all particles with a diameter >0.3 μm, and it is comparable to a Filtering Face piece Respirator2 (FFP 2) mask (European classification system.) Table 1 enumerates the classification of respirators according to their filtration efficacy. However, even a properly fitted N-95 respirator does not completely eliminate the risk of contracting the disease, emphasizing the importance of hand-washing and additional precautions that can never be taken for granted by the HCW [Figures 1 and 2] (Types of respirators).

Table 1.

Respirator filtration efficiency according to the American and European Classification

| Type of mask | Filtration efficiency (%) |

|---|---|

| American classification system | |

| N-95 | ≥95 |

| N 99 | ≥99 |

| European classification system | |

| FFP 1 | ≥80 |

| FFP 2 | ≥94 |

| FFP 3 | ≥99 |

Source: Handbook of Respiratory Protection by Craig E. Colton. FFP: Filtering facepiece

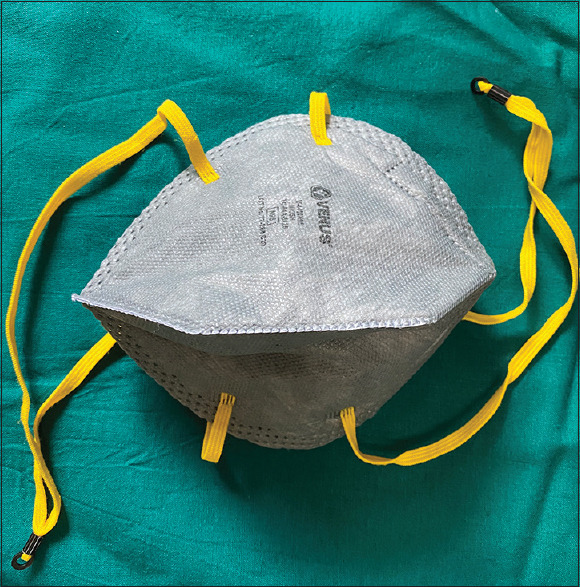

Figure 1.

N-95 Respirator

Figure 2.

Filtering facepiece respirator

WHY IS AN N-95 SUPERIOR TO A SURGICAL MASK?

A properly fitted N-95 will block 95% of aerosolized particles, down to three-tenths of a micron in diameter, from reaching the wearer's face. In contrast, surgical masks, designed to protect patients from a surgeon's respiratory droplets, are not effective at blocking particles smaller than 100 μ. COVID-19 particles were found to measure 1–4 μ in diameter according to an air sampling study where 245 surface samples were collected from 30 isolation rooms at the National Centre for Infectious Diseases, Singapore, where patients with SARS-CoV-2 were being managed.[6] An older, pre-SARS-CoV-2 Chinese study in 2013 had found that twice as many health workers (17%), contracted a viral respiratory illness (like influenza or rhinovirus), when wearing a surgical mask while treating sick patients, compared with 7% of those who continuously used an N-95.[7] Researchers from 2 hospitals in Seoul, Korea, instructed 4 COVID-19 patients admitted in negative pressure isolation rooms to cough five times while wearing cloth and surgical masks. Measuring the median viral load, they found that swabs from the outer mask surfaces were positive for SARS–CoV-2 in both cloth and surgical masks. They concluded that surgical masks were ineffective in preventing the dissemination of SARS–CoV-2 from the coughs of patients with COVID-19 to the environment and external mask surface.[8]

WHY IS IT ESPECIALLY IMPORTANT DURING THE COVID 19 PANDEMIC?

Although earlier studies on SARS-Cov-2 highlighted the risk of droplet and contact transmission of the virus,[9] concerns regarding airborne and aerosol transmission have been more recently recognized. Breathing and talking produce smaller and more numerous particles, known as aerosol particles. These are carried by air currents and dispersed by diffusion and air turbulence.[10] In contrast to inhaled droplets that get deposited in the upper regions of the respiratory tract and subsequently get expelled via nasal secretions or the mucociliary escalator, inhaled aerosols can penetrate into the depths of the lung and may be deposited in the alveoli. A study comparing the aerosol and surface stability of the SARS-CoV-2 virus showed that the novel coronavirus remained viable in aerosols with only a slight reduction in infectivity at the end of 3 h.[10] As we now know, the SARS-CoV-2 is carried by both droplets and aerosols, and hence, an N-95 is essential for the protection of HCWs exposed to these patients.

WHO IS IT RECOMMENDED FOR?

It is crucial to stress that N-95 masks should be reserved exclusively for HCWs in direct contact with patients and should not be used by members of the public who need nothing more than cloth or paper surgical masks.[11] HCWs are at increased risk of contracting COVID-19 for different reasons, including repeated exposure to many positive cases, increased duration of exposure because of lengthy shifts, and lack of appropriate administrative and engineering controls in wards hastily designed in the face of this unprecedented pandemic.[12] They are especially vulnerable during aerosol-generating procedures and treatments such as tracheal intubation, noninvasive ventilation, tracheostomy, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, manual ventilation before intubation and bronchoscopy and in these settings the use of N-95 masks is mandatory.[11]

For non aerosol generating procedures involving COVID-19 patients, whilst WHO advocates the use of surgical masks, the Centres for disease control and Prevention (CDC) and European CDC and Prevention differ in their opinion and recommend the use of N-95 respirators even for non aerosol generating procedures. We would agree with the latter and advocate for the use of the N-95 for HCWs, exposed to and caring for COVID-19 patients even where there is no direct aerosol generation. The absence of the masks may clearly be a contributing factor to the high numbers of HCWs who contract COVID-19 infections, currently estimated at 11% of all infections.[13] We would also stress that simply delivering more respirators and PPE to the frontlines is not enough to solve the crisis faced by our HCWs. The focus should also be on training the HCWs on the right use of appropriate PPE in the right setting.

WHY IS QUALITY CONTROL SO IMPORTANT?

The US regulators recently reported that significant numbers of imported and Chinese manufactured N-95 masks were being pushed into the market without meeting National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) standards. Recent tests performed by NIOSH on a batch of 67 different imported masks found that as many as 60% did not meet standards. Some filtered out as few as 35% of particles only, far short of the 95% it advertised. Many were found to have ear loops to secure them to the head instead of the headbands, which are essential to ensure a tighter fit. Thus millions of substandard and sometimes counterfeit masks are flooding the market, adding to the risks posed to HCWs.[14]

WHAT IS THE CORRECT PROCEDURE FOR DONNING AND DOFFING?

Incorrect use of an N-95 mask and other PPE poses a dual risk. An incorrectly worn mask fails to protect the doctor from the risk of infection. Besides, it can also give the HCW a false sense of security, which puts their lives and the lives of their patients at stake. All HCWs caring for COVID-19 patients should be trained in how to put on, remove, and dispose of an N-95. The correct sequence of donning and doffing is outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Steps for donning and doffing

| Donning | Doffing |

|---|---|

| Perform 20 s hand hygiene with an alcohol-based detergent or rub | Perform hand hygiene, using rub/soap and water |

| Carefully place the mask on the face, cover the nose and mouth to minimize the space between the face and mask | Avoid contact with the front surface of mask which is potentially contaminated |

| Secure the two ties/elastic bands tightly, (the upper band above the ears, at the crown of the head and lower band below the ear at the base of the skull around the neck) | Grasp the bottom tie/elastic band of the respirator, bringing this to front |

| Fit and mold the flexible band to the nose bridge, ensure it fits snugly around the nose, face and chin with an adequate seal | Repeat the process with the top tie and remove the mask from the front holding the two ties without touching the mask itself |

| Exhale firmly into the N-95 once fitted and ensure there is no leak of air from the top, sides, or bottom | After removal or when inadvertently touching a used mask, clean your hands using an alcohol-based cleaner or wash your hands using soap and water if visibly soiled |

| Once the respirator is on the face, avoid touching it with your hands | Throw the disposable masks after use in a closed bag and dispose of them immediately after removal |

WHAT IS A FIT TEST AND HOW IS IT PERFORMED?

The protection offered by a respirator or a mask is dependent not just on its filter capacity but even more crucially on the fit factor. A fit test is a way to assess if an N-95 has been correctly applied and fitted. Those individuals who passed a fit test have been shown to have a better protection factor. The highest percentage of subjects passing FFP fit testing was for FFP 1 and FFP 2. Subjects donning FFP3 respirators did not have the highest fit testing pass rates, which indicates that respirators with the highest filtration efficiencies are not necessarily the ones with the best fit and protection factors. No subjects passed fit testing with a surgical mask. The FFP respirators provided about 11.5–15.9 times better protection than the surgical masks, suggesting that surgical masks are not a good substitute for FFP respirators when concerns exist about the airborne transmission of bacterial and viral pathogens.[15] Fit tests are of two types:

Qualitative fit testing

It is a pass/fail test method that uses one's sense of taste or smell or reaction to an irritant to detect leakage into the respirator facepiece. Qualitative fit testing does not measure the actual amount of leakage. Whether the respirator passes or fails, the test is based simply on us detecting leakage of the test substance into the face-piece. There are four qualitative fit test methods accepted by the Occupational Safety and Health Act. These include isoamyl acetate (banana smell), saccharin (sweet taste), bitrex (bitter taste), and irritant smoke, which can cause coughing.

Quantitative fit tests

This uses a machine to measure the actual amount of leakage into the facepiece and does not rely upon an individual's response to stimuli. The respirators used during this type of fit testing will have a probe attached to the facepiece that is connected to the machine by a hose. Quantitative fit testing can be used for any type of tight-fitting respirator.

WHAT ARE THE MEASURES FOR PROLONGING USE DURING THE CRISIS?

Because of shortages of N-95 masks experienced by almost all hospitals, every attempt to prolong their life and use without compromising safety should be explored. Three measures that allow more prolonged use of N-95 respirators have been looked at.

Extended use refers to the concept of wearing the same respirator for repeated close contact encounters with several patients, without removing the respirator between patient encounters. WHO recommends extended use of PPE, if necessary in the current crisis of acute shortage of PPE[11]

Reuse refers to the practice of using the same N-95 respirator for multiple encounters with patients but removing it (”doffing”) after each encounter. The respirator is stored in between encounters to be later put on again (”donned”) prior to the next patient encounter. CDC recommends that even if it is disposable, the same respirator can be reused by the same HCW provided, it maintains its fit and function and used in accordance with the local infection control policies. Limited reuse may also be considered as an option for conserving respirators in hospitals where they are in short supply during this pandemic. Extended use is preferred over reuse as it involves less risk of contact transmission.[16] Some practical points to be considered with regards to extended/limited reuse of respirators are outlined in Table 3

Decontamination to increase the life may compromise the fit, filtration efficiency, and breathability of disposable respirators as a result of changes to the filtering material, straps, nose bridge material, or strap attachments. Decontamination and reuse are not recommended as the standard of care but may be considered at times of crisis.[17] An ideal decontamination method must remove the viral threat, not affect laboratory performance (filter aerosol penetration and filter airflow resistance), should not compromise the fit or integrity of the various elements of the respirator, be harmless to the user. There is a lack of current data supporting the effectiveness of these decontamination methods specifically against SARS-CoV-2; hence, these respirators must be carefully handled even after decontamination. The three most promising decontamination methods are:

Table 3.

Practical points to be considered during extended use/limited reuse of (N-95)

| Discard N-95 respirators following aerosol generating procedures |

| Discard N-95 respirators contaminated with blood or respiratory secretions |

| Consider use of a cleanable face shield over an N-95 respirator |

| Hang used respirators in a designated storage area or keep them in a clean, breathable properly labeled container such as a paper bag between uses |

| Follow the employer’s maximum number of donning (or up to five if the manufacturer does not provide a recommendation) |

| Discard any respirator that is obviously damaged or becomes hard to breathe through |

| Another practical strategy is to issue five respirators to each HCW caring for COVID-19 patients with advice to wear 1 respirator each day and store it in a breathable paper bag at the end of each shift. The order of respirator use should be repeated with a minimum of 5 days between each respirator use |

Source: CDC (NIOSH recommendations). HCW: Health care workers, COVID: Coronavirus disease, CDC: Centers for disease control and Prevention, NIOSH: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI)

Has a promising role in inactivating human respiratory viruses, including coronaviruses, on various models of N-95s. It has been shown to keep the antimicrobial efficacy >99.99% (for influenza, SARS-CoV-1 and 2 and MERS-CoV) without compromising on fit even after 3 cycles of decontamination with UVGI.[17] The levels of UVGI used to inactivate the virus is well below that which adversely affects the fit and filtration characteristics of N-95 masks;[18] UVGI exposures of 1 J/cm2 are effective in decontaminating influenza virus on these masks and exposures as low as of 2–5 mJ/cm2 are capable of inactivating coronaviruses on surfaces. One study by Lowe et al. has used UVGI at a dose of 300 mJ/cm2, the dose being several folds the amount of exposure needed to inactivate SARS-CoV-2, thus providing a wide margin of safety against the virus. UVGI can be safely administered when appropriate safeguards are in place.[19,20] There is uncertainty regarding how long a UVGI treated N-95 maintains properties to achieve an adequate fit, requiring health care providers to carefully inspect them before and after each reuse for any visible damage.

Vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VHP)

VHP decontamination for a single cycle does not significantly affect filter aerosol penetration and airflow resistance. The filtration efficacy was found to be more than 99.99% for the tested fungal spores. The fit was unaffected even after 20 cycles of treatment. The time for decontamination is less than an hour. It may cause tarnishing of metallic nosebands and straps of the respirator after about 20 cycles.[17] Because of the acute shortages of N-95s in this pandemic, the FDA, has recently approved and fast-tracked a Columbus-based company Battelle's new technology, which uses vapor phase hydrogen peroxide to disinfect N-95 masks, conceding to the company's request for permission to clean up to 80,000 masks a day. Their technology allows the masks to be reused about 20 times without significant compromise on their filtration capacity. The company has developed this technology years ago, but the present COVID 19 pandemic has forced the company to ramp up their machines to disinfect masks on a larger scale, which is truly the need of the hour.[21]

Moist heat

Moist heat (60°C and 80% relative humidity) caused minimal degradation in the filtration and fit performance of the tested respirators against two strains of influenza viruses. Heimbuch disinfected FFPs contaminated with H1N1 using moist heat and achieved a 99.99% reduction in virus load. An important limitation of the moist heat method is the uncertainty of the disinfection efficacy for various pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2.[17]

Currently, what is being used in some centers due to shortages, but cannot be recommended is the use of ethylene oxide (EtO) and autoclaving. While EtO does not compromise the filtration efficacy, it may be carcinogenic and teratogenic and hence is not recommended.[17,22] Autoclaving and the use of disinfectant wipes are not recommended as they may alter respirator performance.[17]

Concluding remarks

In the present coronavirus pandemic, the humble N-95 mask has proved to be the HCW's most essential weapon. The shortages of these masks experienced in hospitals across the world have only served to underline their importance in protecting HCWs from this deadly airborne pandemic. Their absence has also highlighted how unprepared the world was for the pandemic that began in January and swept across >200 countries. This article provides an update on the N-95 and gives some emerging information on prolonging and extending their use when supply is critically limited.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Xie J. World Depends on China for Face Masks, but can Country Deliver VOA. [Last accessed on 2020 May 05; Last accessed on 2020 May 04]. Available from: https://wwwvoanewscom/science-health/coronavirus-outbreak/world-depends-china-face-masks-can-country-deliver .

- 2.Ten California nurses Suspended for Refusing to work without N95 Masks. The Guardian. [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]. Available from: https://wwwtheguardiancom/world/2020/apr/16/santa-monica-nurses-suspended-n95-masks-coronavirus\ .

- 3.US Accused of “Modern Piracy” after Diversion of Masks Meant for Europe. The Guardian. [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]. Available from: https://wwwtheguardiancom/world/2020/apr/03/mask-wars-coronavirus-outbidding-demand .

- 4.Ferioli M, Cisternino C, Leo V, Pisani L, Palange P, Nava S. Protecting healthcare workers from SARS-CoV-2 infection: Practical indications. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29:200068. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0068-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Technical data Bulletin. Respiratory Protection for Airborne Exposures to Biohazards M Science Applied to Life; 04 April, 20202. [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]. Available from: https://multimedia3mcom/mws/media/409903O/respiratory-protection-against-biohazardspdf .

- 6.Chia PY, Coleman KK, Tan YK, Ong SW, Gum M, Lau SK, et al. Detection of Air and surface contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Hospital Rooms of Infected Patients Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS) 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 May 03; Last accessed on 2020 May 05]. Available from: http://medrxivorg/lookup/doi/101101/2020032920046557 .

- 7.MacIntyre CR, Wang Q, Seale H, Yang P, Shi W, Gao Z, et al. A randomized clinical trial of three options for N95 respirators and medical masks in health workers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:960–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201207-1164OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bae S, Kim M-C, Kim JY, Cha H-H, Lim JS, Jung J, et al. EffectivenessEffectiveness of Surgical and Cotton Masks in Blocking SARS-CoV-2: A Controlled Comparison in 4. Patients Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.Wu D, Wu T, Liu Q, Yang Z. The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: What we know. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:44–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meselson M. Droplets and Aerosols in the Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 15; doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009324. NEJMc2009324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO Interim Guidance. Rational use of Personal Protective Equipment for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and Considerations During Severe Shortages. [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]. Available from: https://appswhoint/iris/handle/10665/331498 .

- 12.Udwadia ZF, Raju RS. How to protect the protectors: 10 lessons to learn for doctors fighting the COVID-19 coronavirus. Medical Journal Armed Forces India. 2020 Mar; doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.03.009. S0377123720300472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CDC. Characteristics of Health Care Personnel with COVID-19 — United States; 12 February, April 9, 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 May 05; Last accessed on 2020 May 03]. Available from: https://wwwcdcgov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6915e6htm .

- 14.Austen Hafford Mark Maremont. Low-Quality Masks Infiltrate US Coronavirus. Supply The Wall street Journal [Internet] 2020. May 3, cited 2020 May 4. Available from: https://wwwmsncom/en-us/news/us/low-quality-masks-infiltrate-us-coronavirus-supply/ar-BB13xHSO .

- 15.Lee SA, Hwang DC, Li HY, Tsai CF, Chen CW, Chen JK. Particle size-selective assessment of protection of European Standard FFP respirators and surgical masks against particles-tested with human subjects. J Healthc Eng. 2016;2016:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2016/8572493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC-NIOSH. Recommended Guidance for Extended Use and Limited Reuse of N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirators in Healthcare Settings. [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]. Available from: https://wwwcdcgov/niosh/topics/hcwcontrols/recommendedguidanceextusehtml .

- 17.CDC. Decontamination and Reuse of Filtering Facepiece Respirators-Using Contingency and Crisis Capacity Strategies-COVID 19. [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]. Available from: https://wwwcdcgov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/decontamination-reuse-respiratorshtml .

- 18.Lowe JJ, Paladino KD, Farke JD, Boulter K, Cawcutt K, Emodi M, et al. N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirator Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation (UVGI) Process for Decontamination and Reuse [Internet] 2020. Available from: https://wwwnebraskamedcom/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19/n-95-decon-processpdf .

- 19.Tseng CC, Li CS. Inactivation of viruses on surfaces by ultraviolet germicidal irradiation. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2007;4:400–5. doi: 10.1080/15459620701329012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mills D, Harnish DA, Lawrence C, Sandoval-Powers M, Heimbuch BK. Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation of influenza-contaminated N95 filtering facepiece respirators. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46:e49–e55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marty Schladen. FDA lifts restrictions on Ohio-based Battelle's Mask-Sterilizing Technology amid Coronavirus Shortages US Today 29 March 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]. Available from: https://wwwusatodaycom/story/news/nation/2020/03/29/coronavirus-fda-eases-restrictions-mask-sterilization-technology/2936670001/

- 22.Viscusi DJ, Bergman MS, Eimer BC, Shaffer RE. Evaluation of five decontamination methods for filtering facepiece respirators. Ann Occup Hyg. 2009;53:815–27. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mep070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]