Abstract

Objective

Patients with advanced coronary artery disease are referred for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and it remains unknown if sleep apnoea is a risk marker. We evaluated the association between sleep apnoea and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) in patients undergoing non-emergent CABG.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study conducted between November 2013 and December 2018. Patients from four public hospitals referred to a tertiary cardiac centre for non-emergent CABG were recruited for an overnight sleep study using a wrist-worn Watch-PAT 200 device prior to CABG.

Results

Among the 1007 patients who completed the study, sleep apnoea (defined as apnoea-hypopnoea index ≥15 events per hour) was diagnosed in 513 patients (50.9%). Over a mean follow-up period of 2.1 years, 124 patients experienced the four-component MACCE (2-year cumulative incidence estimate, 11.3%). There was a total of 33 cardiac deaths (2.5%), 42 non-fatal myocardial infarctions (3.7%), 50 non-fatal strokes (4.9%) and 36 unplanned revascularisations (3.2%). The crude incidence of MACCE was higher in the sleep apnoea group than the non-sleep apnoea group (2-year estimate, 14.7% vs 7.8%; p=0.002). Sleep apnoea predicted the incidence of MACCE in unadjusted Cox regression analysis (HR 1.69; 95% CI 1.18 to 2.43), and remained statistically significant (adjusted HR 1.57; 95% CI 1.09 to 2.25), after adjustment for age, sex, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease and excessive daytime sleepiness.

Conclusion

Sleep apnoea is independently associated with increased MACCE in patients undergoing CABG.

Trial registration number

Keywords: coronary artery disease surgery, cardiac surgery, cardiac risk factors and prevention, chronic coronary disease, heart failure

Introduction

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is the most widely performed cardiac surgical procedure worldwide. Each year, approximately 320 000 cases of CABG (average rate of 44/100 000 individuals) are performed in Europe, while 370 000 cases are performed in the USA.1 2 In patients with high-risk features (left ventricular dysfunction, diabetes mellitus and complex multivessel coronary artery disease), revascularisation via CABG compared with percutaneous coronary intervention provides greater benefits.3 Despite advances in surgical techniques, equipment and adjunctive pharmacological therapies, the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events within 5 years after CABG is high and ranges from 13% to 27%.3

Sleep apnoea is a form of sleep-disordered breathing which is highly prevalent worldwide.4 Increasingly, this condition has also been recognised as an important risk factor for cardiovascular and perioperative adverse outcomes.5–7 Although observational studies and meta-analysis have identified sleep apnoea as an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention,8 9 whether this prognostic effect can be extrapolated to patients indicated for CABG (who usually have more extensive disease and a higher risk profile) remains unclear.

The existing evidence regarding the relationship between sleep apnoea and cardiovascular outcomes is derived from small studies based mainly on short-term follow-up duration.10–14 The majority of these studies yielded conflicting data, and did not report angiographic or surgical details. To date, no clinical study has been sufficiently powered to detect a difference in adverse cardiovascular events. To address this gap, we designed the Sleep Apnoea and Bypass OperaTion (SABOT) study in patients undergoing non-emergent CABG to evaluate the association between sleep apnoea and long-term cardiovascular outcomes. In this study, we investigated the hypothesis that sleep apnoea is associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events.

Methods

Study design and participants

This prospective observational cohort study was conducted at the National University Heart Centre Singapore, a tertiary institution that receives referrals for CABG from four public hospitals in Singapore. The SABOT study has been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, and the abstract has been presented previously.15

Patients aged 18–90 years who were scheduled to undergo non-emergent CABG, defined as an interval of >24 hours between the decision to perform CABG and the operative procedure, were deemed eligible for this study. Patients who underwent minimally invasive CABG and those undergoing other concurrent cardiac procedures (eg, valve surgery and aortic root surgery) were included. Patients who had received continuous positive airway pressure therapy or other forms of treatment for known sleep apnoea, mechanical ventilation or an intra-aortic balloon pump for cardiogenic shock or oxygen therapy for an exacerbation of ongoing heart failure; were considered high risk for malignant arrhythmia; were using long-term α-blocker therapy, or had a history of severe chronic pulmonary disease were excluded.

As per standard practice at our institution, all patients undergoing non-emergent CABG were admitted at least 1 day prior to surgery. Eligible patients underwent an overnight sleep study during the night before CABG. Patients who did not have achieved an adequate sleep duration of at least 4 hours were excluded from analysis. The teams providing clinical care to the patients were blinded to the results of the sleep study. All patients were followed prospectively via a combination of clinic visits, medical records review and/or telephone contact. All subsequent clinical care and management were conducted as per routine clinical practices.

Diagnosis of sleep apnoea

All recruited patients were asked to complete both the Berlin Questionnaire and Epworth Sleepiness Scale questionnaire during face-to-face interviews.16 17 Regardless of questionnaire results, all participants underwent an in-hospital overnight sleep study using a USA Food and Drug Administration-approved wrist-worn portable device (Watch-PAT 200, Itamar Medical, Caesarea, Israel) previously validated using in-laboratory polysomnography.18 The Watch-PAT 200 measures the peripheral arterial tone (PAT), which is a marker of arterial pulsatile volume changes in the finger that are regulated by α-adrenergic nerve activity in the vascular smooth muscle. This parameter reflects the sympathetic nervous system activity and was found to correlate strongly with polysomnography data in a previous meta-analysis of 14 studies (apnoea-hypopnea index, r=0.893; 95% CI 0.857 to 0.920; p<0.001).17 In addition, the Watch-PAT 200 measures three additional channels, namely the heart rate (derived from the PAT signal), pulse oximetry and actigraphy (via a built-in actigraph). Subsequently, the device uses proprietary algorithms to estimate the PAT signal amplitude, increases in heart rate and desaturation, the apnoea-hypopnea index, oxygen desaturation index and respiratory disturbance index. Patients were classified according to the presence or absence of sleep apnoea, defined respectively as a Watch-PAT apnoea-hypopnea index ≥15 or <15 events per hour.

Outcomes

The prespecified primary endpoint of this study was major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), defined as the four-component composite of cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke and unplanned revascularisation. The secondary endpoints included all-cause mortality, sudden cardiac death or resuscitated cardiac arrest, and hospitalisation for heart failure. These events were defined according to the Standardised Data Collection for Cardiovascular Trials Initiative.19 Clinical event data were collected by a team blinded to the sleep study results. All reported adverse events were adjudicated further by an independent clinical event committee that was similarly blinded to the sleep study results.

Statistical analysis

The primary hypothesis of the study was that the incidence of MACCE would be higher in the sleep apnoea group, compared with the non-sleep apnoea group. Accordingly, this study was powered according to the incidence of MACCE between the two groups. Given the lack of a previous large-scale study on the effect of sleep apnoea on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with CABG, we assumed an HR of 1.6 based on a study of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.8 Using the R package powerSurvEpi, we determined that to achieve this HR, the study would need a sample size of 1092, assuming a sleep apnoea prevalence of 35.3%,20 and respective frequencies of MACCE of 16% and 10% in the sleep apnoea and non-sleep apnoea groups with a power of 80% and level of significance of 5%.

Regarding study data, the categorical variables were compared between the sleep apnoea and non-sleep apnoea groups using the χ2 test and are presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables with normally distributed data were compared using the independent samples t-test and summarised as means with SDs; otherwise, skewed data were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test and presented as medians with IQRs. Curves of the cumulative incidence curves of MACCE, all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, sudden cardiac death or resuscitated cardiac arrest, and hospitalisation for heart failure were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between both groups using the log-rank test.

A Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to compare the times to occurrence of MACCE between the sleep apnoea and the non-sleep apnoea groups, with adjustments for potential confounders. The covariates included in the multivariate Cox regressions were selected based on clinical relevance and included age, sex, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease and excessive daytime sleepiness. The model was then optimised by removing statistically insignificant variables using the backward selection method, and the HRs and corresponding 95% CIs were computed. Since left ventricular ejection fraction, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease and excessive daytime sleepiness could be intermediate variables in the pathway between exposure and outcomes, another partially adjusted model including age, sex and body mass index only was included. A similar analysis based on the Cox proportional hazards model was performed to compare the incidence rates of the secondary endpoints between both groups.

To account for potential competing risks due to mortality, the competing risk regression model developed by Fine and Gray21 was used to refit the previous Cox regression models and compute HRs and 95% CIs.21 IBM SPSS Statistics V.25 (IBM) was used to compute the descriptive statistics, Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence curves and Cox regression. The 2-year cumulative incidence and Fine and Gray’s competing risk regression were computed using the cmprsk package in R software (V.3.5.2; 20 December 2018; The R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All two-sided p values <0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant finding.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient and public involvement.

Results

Baseline characteristics

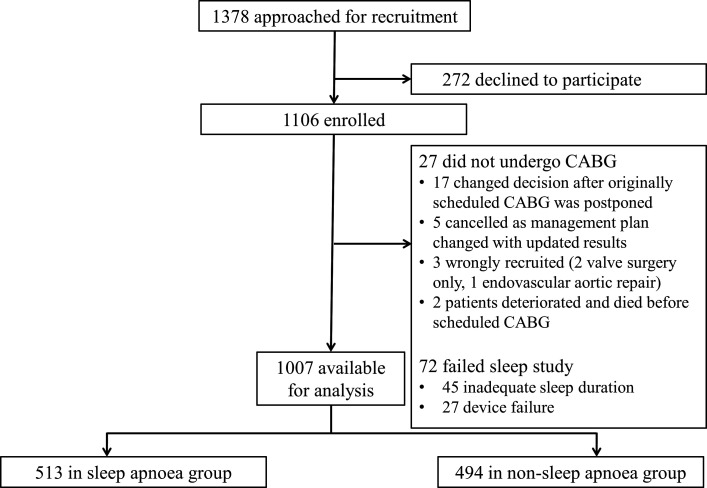

A flow chart of the study is shown in figure 1. Between November 2013 and December 2018, 1378 eligible patients were approached and 1106 were recruited. After excluding 72 patients whose initial sleep studies were unsuccessful and not repeated, and 27 patients who did not undergo their scheduled CABG (details in figure 1), the cohort for this analysis comprised 1007 patients. Of these patients, 513 (50.9%) were diagnosed with sleep apnoea. The baseline demographics, clinical characteristics and sleep study results of the sleep apnoea and the non-sleep apnoea groups are shown in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of screening and recruitment. All patients who met the inclusion criteria were screened for recruitment. CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical characteristics and sleep study results

| Characteristics | Sleep apnoea (n=513) |

Non-sleep apnoea (n=494) |

P value |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 62 (56–68) | 61 (56–67) | 0.23 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 442 (86.2) | 429 (86.8) | 0.75 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.37 | ||

| Chinese | 338 (65.9) | 314 (63.3) | |

| Malay | 93 (19.1) | 101 (20.4) | |

| Indian | 50 (9.7) | 57 (11.5) | |

| Others | 32 (6.2) | 22 (4.5) | |

| Clinical measurements | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 125 (111–138) | 125 (110–138) | 0.70 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 70 (63–79) | 70 (62–79) | 0.35 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 25.9 (23.3–28.6) | 23.5 (21.8–26.2) | <0.0001 |

| Neck circumference, mean (SD), cm | 39 (37–41) | 38 (36–40) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference, mean (SD), cm | 95 (88–102) | 90 (84–96) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Smoking | 139 (27.1) | 155 (31.4) | 0.23 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 401 (81.2) | 417 (81.3) | 0.96 |

| Hypertension | 404 (78.8) | 349 (70.6) | 0.0030 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 295 (57.5) | 278 (56.3) | 0.69 |

| Family history of premature coronary disease | 37 (7.2) | 43 (8.7) | 0.38 |

| Concomitant conditions, n (%) | |||

| Previous myocardial infarction | 239 (46.6) | 221 (44.7) | 0.56 |

| Previous percutaneous coronary intervention | 119 (23.2) | 101 (20.4) | 0.29 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass surgery | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0.24* |

| Stroke/transient ischaemic attack | 61 (11.9) | 57 (11.5) | 0.86 |

| Chronic kidney disease† | 102 (19.9) | 63 (12.8) | 0.002 |

| Chronic kidney disease on dialysis | 28 (5.5) | 8 (1.6) | 0.001* |

| Pre-existing atrial fibrillation | 24 (4.7) | 23 (4.3) | 1.00* |

| Pacemaker in situ | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1.00* |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator in situ | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 0.63* |

| Sleep study results | |||

| AHI (events per hour), median (IQR) | 30.1 (20.6–44.7) | 5.85 (3.0–10.23) | <0.0001 |

| RDI (events per hour), median (IQR) | 32.9 (24.3–47.4) | 10.4 (6.6–14.4) | <0.0001 |

| ODI (events per hour), median (IQR) | 18.1 (11.2–33.6) | 2.3 (0.9–4.83) | <0.0001 |

| Sleep duration (hour), median (IQR) | 6.40 (5.49–7.30) | 6.30 (5.32–7.10) | 0.24 |

| Duration SpO2<90% (min), median (IQR) | 4.50 (0.60–19.85) | 0.00 (0.00–0.60) | <0.0001 |

| Percentage of sleep SpO2<90% (%), median (IQR) | 1.20 (0.20–5.08) | 0.00 (0.00–0.10) | <0.0001 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale >10, n (%) | 69 (13.5) | 54 (11.0) | 0.23 |

| High-risk Berlin Questionnaire, n (%) | 239 (46.8) | 201 (40.9) | 0.06 |

*P values were computed using Fisher’s exact test.

†Serum estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

AHI, apnoea-hypopnoea index; ODI, oxygen desaturation index; RDI, respiratory disturbance index; SpO2, arterial oxygen saturation.

In the overall cohort, more than 40% and 20% of the included patients had a history of myocardial infarction or percutaneous coronary intervention, respectively. Compared with the non-sleep apnoea group, the sleep apnoea group had a higher average body mass index and higher prevalence of hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Slightly more than 10% of patients in both groups reported excessive daytime sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale >10).

Diagnostic coronary angiography and echocardiography

Table 2 presents the findings from diagnostic coronary angiography and echocardiography evaluations. Notably, the two groups did not differ significantly with respect to angiographic characteristics and SYNTAX scores. Most (84.3%) patients had triple vessel disease, and nearly a third of the patients exhibited ≥50% stenosis (determined visually) of the left main coronary artery. Categorically, the sleep apnoea group included more patients with impaired left ventricular ejection fraction and had a higher left atrial size, left ventricle dimensions, left ventricular mass index and pulmonary artery systolic pressures, compared with the non-sleep apnoea group (all p<0.001).

Table 2.

Diagnostic coronary angiography and echocardiography findings

| Characteristics | Sleep apnoea (n=513) |

Non-sleep apnoea (n=494) |

P value |

| Coronary angiography | |||

| Clinical presentation, n (%) | 0.22 | ||

| ST–segment elevation myocardial infarction | 60 (11.7) | 49 (9.6) | |

| Non–ST–segment elevation myocardial infarction | 205 (40.1) | 185 (36.1) | |

| Unstable angina | 94 (18.4) | 103 (20.1) | |

| Stable angina | 129 (25.2) | 143 (27.9) | |

| Other | 23 (4.5) | 13 (2.5) | |

| Number of diseased coronary vessels, n (%) | 0.27 | ||

| 1 | 20 (3.9) | 14 (2.8) | |

| 2 | 56 (10.9) | 68 (13.8) | |

| 3 | 437 (85.2) | 412 (83.4) | |

| Left main artery stenosis ≥50% | 155 (30.4) | 157 (31.8) | 0.63 |

| Proximal left anterior descending artery stenosis ≥50% | 379 (74.8) | 368 (74.8) | 0.99 |

| SYNTAX score, median (IQR) | 33 (26–41) | 33 (26–41) | 0.92 |

| Echocardiography | |||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, median (IQR), % | 50 (37–60) | 55 (45–60) | <0.0001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| >50% | 223 (48.0) | 264 (61.1) | |

| 30%–50% | 158 (34.0) | 120 (27.8) | |

| <30% | 84 (18.1) | 48 (11.1) | |

| Left atrium diameter, median (IQR), mm | 41 (37–45) | 38 (35–42) | <0.0001 |

| Left ventricular end–diastolic internal diameter, median (IQR), mm | 52 (47–57) | 49 (45–54) | <0.0001 |

| Left ventricular end–systolic internal diameter, median (IQR), mm | 36 (31–44) | 33 (29–39) | <0.0001 |

| Left ventricular mass index, median (IQR), g/m2 | 108 (89–132) | 98 (82–123) | <0.0001 |

| Aortic root diameter, median (IQR), mm | 33 (30–36) | 32 (30–35) | 0.011 |

| E/A, median (IQR) | 0.87 (0.67–1.32) | 0.86 (0.70–1.20) | 0.41 |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure, median (IQR), mm Hg | 30 (25–39) | 29 (24–34) | 0.016 |

Data were missing from the categories of clinical presentation (n=3), left main stenosis (n=3) and left anterior descending artery stenosis (n=8). Preoperative echocardiography data were available in 897 of 1007 patients.

Coronary artery bypass grafting

The details of CABG are presented in table 3. Most (96.7%) patients underwent conventional on-pump CABG with cardiopulmonary bypass. Patients in the sleep apnoea group were more likely to undergo concurrent valve operation, compared with those in the non-sleep apnoea group (8.6% vs 5.1%, p=0.028). However, the groups did not differ in terms of surgical complexity, based on the number of bypass grafts and the estimated blood loss. Fourteen patients died, including nine and five with and without sleep apnoea, respectively, yielding an overall in-hospital mortality rate of 1.4%. Patients with sleep apnoea had a slightly longer length of stay.

Table 3.

Coronary artery bypass grafting characteristics

| Characteristics | Sleep apnoea (n=513) |

Non-sleep apnoea (n=494) |

P value |

| Operation type, n (%) | 0.11 | ||

| On-pump CABG | 502 (97.9) | 472 (95.5) | |

| Off-pump CABG | 10 (1.9) | 21 (4.3) | |

| Hybrid CABG | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Number of bypass grafts, n (%) | 0.077 | ||

| 1–2 | 119 (23.2) | 100 (20.2) | |

| 3–4 | 384 (74.9) | 391 (79.1) | |

| 5–6 | 10 (1.9) | 3 (0.6) | |

| Number of venous grafts, n (%) | 0.31 | ||

| 0–1 | 127 (24.8) | 117 (23.7) | |

| 2–3 | 378 (73.7) | 374 (75.7) | |

| 4–5 | 8 (1.6) | 3 (0.6) | |

| LIMA graft, n (%) | 484 (94.3) | 474 (96.0) | 0.24 |

| Non-LIMA arterial grafts, n (%) | 0.76 | ||

| Radial artery or RIMA | 28 (5.5) | 31 (6.3) | |

| Radial artery and RIMA | 7 (1.4) | 5 (1.0) | |

| Concurrent valve operation, n (%) | 44 (8.6) | 25 (5.1) | 0.028 |

| Total operation time (min), median (IQR) | 295 (255–330) | 287 (253–324) | 0.044 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL), median (IQR) | 200 (110–300) | 200 (100–300) | 0.97 |

| Length of stay (days), median (IQR) | 7.5 (6.0–10.0) | 7.0 (6.0–9.0) | 0.00096 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; LIMA, left internal mammary artery; RIMA, right internal mammary artery.

Medications upon discharge

Table 4 lists the medications prescribed on hospital discharge. Patients in the sleep apnoea group were relatively more likely to receive oral anticoagulant and diuretic therapy. The prescriptions of other cardiovascular medications were similar between the two groups.

Table 4.

Medications upon hospital discharge

| Medications | Sleep apnoea (n=504) |

Non-sleep apnoea (n=489) |

P value |

| Aspirin | 467 (92.7) | 441 (90.2) | 0.16 |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 386 (76.6) | 392 (80.2) | 0.17 |

| β-blocker | 457 (90.7) | 441 (90.2) | 0.79 |

| ACEI/ARB | 176 (34.9) | 169 (34.6) | 0.91 |

| Statin | 489 (97.0) | 480 (98.2) | 0.24 |

| Ezetimibe | 11 (2.2) | 7 (1.4) | 0.38 |

| Fibrates | 12 (2.4) | 8 (1.6) | 0.40 |

| Oral anticoagulant | 83 (16.5) | 45 (9.2) | 0.0010 |

| Warfarin* | 66 (13.1) | 37 (7.6) | 0.0040 |

| Direct oral anticoagulant† | 17 (3.4) | 8 (1.6) | 0.081 |

| Frusemide | 302 (59.9) | 240 (49.1) | 0.0010 |

| Spironolactone | 40 (7.9) | 18 (3.7) | 0.0040 |

*Indications (warfarin, sleep apnoea group): atrial fibrillation (n=29, 43.9%), endarterectomy (n=20, 30.3%), valve replacement (n=12, 18.2%), miscellaneous (n=5, 7.6%; left ventricular thrombus=4, antiphospholipid syndrome=1). Indications (warfarin, non-sleep apnoea group): atrial fibrillation (n=21, 56.8%), endarterectomy (n=11, 29.7%), valve replacement (n=3, 8.1%), multiple old strokes (n=2, 5.4%).

†Indications (direct oral anticoagulant, sleep apnoea group): atrial fibrillation for all.

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Follow-up and clinical outcomes

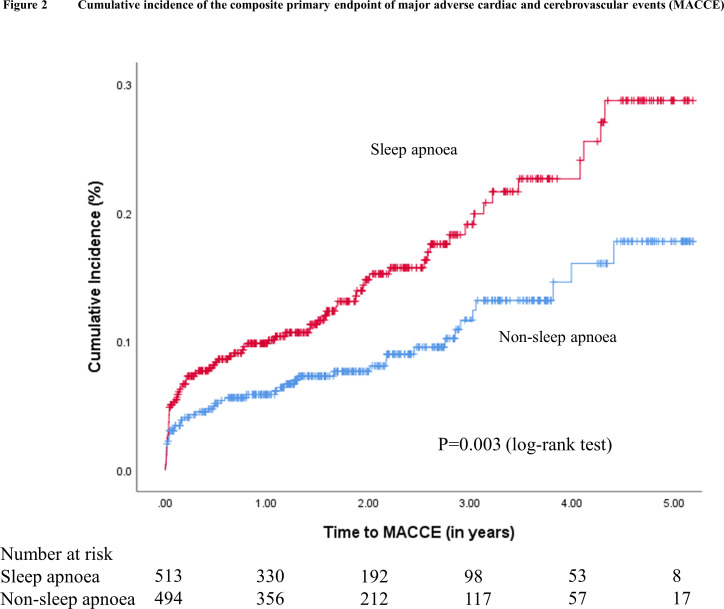

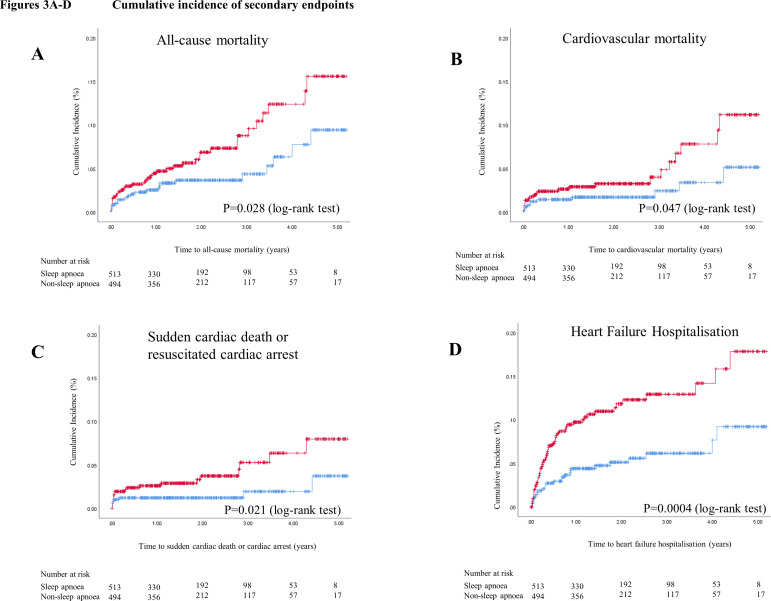

During a mean follow-up of 2.1 years, 124 patients experienced MACCE (2-year cumulative incidence estimate, 11.3%), including 33 cardiovascular deaths (2-year cumulative incidence estimate, 2.5%), 42 non-fatal myocardial infarctions (3.7%), 50 non-fatal strokes (4.9%) and 36 unplanned revascularisations (3.2%). The Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence curves of MACCE, all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, sudden cardiac death or resuscitated cardiac arrest, and hospitalisation for heart failure are shown in figures 2 and 3A–D, respectively. The crude incidence of MACCE was higher in the sleep apnoea group than in the non-sleep apnoea group (2-year estimate, 14.7% vs 7.8%; p=0.002). Likewise, the crude incidence rates of sudden cardiac death or resuscitated cardiac arrest (2-year estimate, 3.7% vs 1.2%, p=0.021) and hospitalisation for heart failure (2-year estimate, 11.5% vs 5.0%; p<0.001) were also higher in the sleep apnoea group.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of the composite primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE). Kaplan–Meier plot showing the cumulative incidence of MACCE in patients with sleep apnoea (in red) and in patients without sleep apnoea (in blue).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of secondary endpoints. Kaplan–Meier plots showing the cumulative incidences of all-cause mortality (A), cardiovascular mortality (B), sudden cardiac death or resuscitated cardiac arrest (C), and hospitalisation for heart failure (D), respectively, in patients with sleep apnoea (in red) and in patients without sleep apnoea (in blue).

As shown in table 5, model 1 demonstrated that the presence of sleep apnoea predicted the incidence of MACCE in an unadjusted competing risk model (HR 1.69; 95% CI 1.18 to 2.43). This association remained statistically significant in both minimally adjusted models (model 2) and after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease and excessive daytime sleepiness in model 3 (adjusted HR 1.57; 95% CI 1.09 to 2.25). Regarding the secondary endpoints, the incidence rates of all-cause mortality, sudden cardiac death or resuscitated cardiac arrests, and hospitalisation for heart failure were higher in the sleep apnoea group, compared with the non-sleep apnoea group. In an analysis including adjustments of the mentioned confounding variables, the association of sleep apnoea with hospitalisation for heart failure remained (adjusted HR 1.78; 95% CI 1.07 to 2.96).

Table 5.

Adjusted HRs for adverse events using competing risk regression

| Characteristics | Model 1: unadjusted HR (95% CI) |

P value | Model 2: adjusted HR* (95% CI) |

P value | Model 3: adjusted HR† (95% CI) |

P value |

| MACCE (cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, unplanned revascularisation) | 1.69 (1.18 to 2.43) | 0.004 | 1.65 (1.12 to 2.43) | 0.012 | 1.57 (1.09 to 2.25) | 0.015 |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 2.03 (0.99 to 4.18) | 0.055 | 2.02 (0.96 to 4.25) | 0.063 | 1.73 (0.82 to 3.61) | 0.150 |

| Non-fatal myocardial infarction | 1.22 (0.67 to 2.24) | 0.520 | 1.26 (0.64 to 2.46) | 0.500 | 1.13 (0.63 to 2.04) | 0.690 |

| Non-fatal stroke | 1.49 (0.85 to 2.62) | 0.170 | 1.45 (0.80 to 2.62) | 0.220 | 1.33 (0.76 to 2.35) | 0.320 |

| Unplanned revascularisation | 1.27 (0.66 to 2.45) | 0.470 | 1.27 (0.64 to 2.52) | 0.500 | 1.28 (0.67 to 2.46) | 0.450 |

| All-cause mortality | 1.81 (1.06 to 3.09) | 0.030 | 1.78 (1.01 to 3.14) | 0.045 | 1.35 (0.77 to 2.36) | 0.300 |

| Sudden cardiac death or resuscitated cardiac arrest | 2.51 (1.11 to 5.71) | 0.028 | 2.41 (0.99 to 5.87) | 0.052 | 2.09 (0.91 to 4.85) | 0.084 |

| Heart failure hospitalisation | 2.22 (1.39 to 3.53) | <0.001 | 2.11 (1.32 to 3.38) | 0.002 | 1.78 (1.07 to 2.96) | 0.026 |

| New-onset atrial fibrillation | 1.16 (0.88 to 1.54) | 0.300 | 1.15 (0.86 to 1.54) | 0.340 | 1.15 (0.86 to 1.53) | 0.340 |

*Model 2: competing risk regression adjusted for age, sex, body mass index and smoking status with backward selection method.

†Model 3: Competing risk regression adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, number of bypass grafts, left ventricular ejection fraction, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease and excessive daytime sleepiness with backward selection method.

MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events.

Discussion

This study provides insights into the role of sleep apnoea as a predictor of cardiovascular outcomes after CABG. Notably, half of the patients in our cohort had sleep apnoea, which was associated with an increased incidence of MACCE. After adjustments for age, sex, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease and excessive daytime sleepiness, patients in the sleep apnoea group had a 1.57-fold increase in the risk of experiencing MACCE during a mean follow-up of 2.1 years. Although the effect of sleep apnoea trended towards an increased risk in all four components classified as MACCE (cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke and unplanned revascularisation) although non-significant, the adjusted HR was highest for cardiovascular mortality. Moreover, sleep apnoea was associated with a 1.78-fold increase in the risk of hospitalisation for heart failure.

To the best of our knowledge, the SABOT study is the largest prospective study in patients undergoing non-emergent CABG to evaluate the prognostic implication of sleep apnoea with respect to MACCE. In the only previous relevant study reporting long-term outcomes, Uchôa and colleagues reported an association of sleep apnoea with an increased risk of repeat revascularisation after CABG but not cardiovascular mortality.10 Although the prevalence (>50%) of sleep apnoea was high in both studies, we found no difference in revascularisation but instead a higher incidence of cardiovascular mortality. We attribute the interstudy discrepancies to the ability of our study to detect differences in mortality at a higher level of power through our larger (1007 patients vs 67 patients in Uchôa et al) sample size. The lack of an observed intergroup difference in the repeated revascularisation rate may be attributed to the shorter follow-up duration of our study (2.1 years vs 4.5 years in Uchôa et al), as the risk of disease progression or graft failure is usually more apparent during a longer follow-up.

The mechanisms underlying the negative prognostic effects of sleep apnoea remain unknown, although previous studies have suggested chronic hypoxaemia, sympathetic hyperactivity and endothelial dysfunction.22 We previously reported that in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, sleep apnoea independently predicted the occurrence of MACCE.8 Therefore, regardless of the mode of revascularisation, sleep apnoea appears to be a marker of poor outcomes in patients with severe coronary artery disease. Sleep apnoea additionally predicted hospitalisation for heart failure in patients undergoing CABG, which warrants attention as repeated hospitalisation after CABG is an important cause of morbidity and escalating healthcare costs.

The design of the SABOT study was critically challenged by concerns regarding the safety of subjecting patients of high cardiac risk awaiting CABG to laboratory-based polysomnography. Accordingly, we decided to implement the Watch-PAT 200. In our studies and other studies, the Watch-PAT 200 appears to enable successful sleep study completion and is consistent with global trends in ambulatory monitoring and digital medicine.23 The use of a portable sleep study to guide clinical management of patients with sleep apnoea compared with evaluation via conventional polysomnography has been proven to be non-inferior with additional benefits in cost savings.24 Moreover, the use of portable sleep studies has been increasingly adopted for use in large-scale studies.14 25

Our study has several limitations of note. First, although the study patients were referred from four public hospitals, all CABG procedures were performed by the same team of cardiothoracic surgeons at a single institution. Although the generalisability of the findings may be limited, the composition of our cardiothoracic team was unchanged throughout the study period and therefore the internal consistency was maintained. Additionally, the inclusion criteria were broad, and the recruited patients were representative of practice in the real world. Second, the Watch-PAT 200 could not differentiate between obstructive and central sleep apnoea. Still, two prior studies involving sleep apnoea screening in patients undergoing CABG or cardiovascular surgery did not identify any cases of central sleep apnoea,10 26 and a similarly large cohort study of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention found that only 5% of the patients had central sleep apnoea.8 Therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that the majority of patients in our sleep apnoea group had obstructive sleep apnoea. Third, the sleep study was not repeated after CABG, and therefore we could not determine whether the sleep apnoea had improved or deteriorated postoperatively. Fourth, there may be other residual confounding factors that we have not accounted for due to the observational nature of this study. This could especially be the case for the secondary endpoint of hospitalisation for heart failure, where patients with sleep apnoea had more advanced cardiac impairment noted on echocardiography, and other variables beyond that of ejection fraction could account for the differences observed. Lastly, although a sufficient number of patients provided consent to participate (n=1106), dropouts due to sleep study failures and cancellations of CABG meant that we missed our target cohort size of 1092 by 85 patients (7.8%). Still, we decided to analyse the 1007 patients to accommodate the temporal limitations of the research grant (end date: December 2018). Based on the presented results, we do not believe that additional patients would materially alter the findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that half of all study patients undergoing non-emergent CABG had sleep apnoea. This condition was associated independently with higher incidence rates of MACCE and hospitalisation for heart failure. The growing burdens of obesity and sedentary lifestyle habits have increased the global prevalence of sleep apnoea and cardiovascular disease. Our data compellingly support that the detection and management of sleep apnoea in patients undergoing coronary revascularisation needs improvement.

Key questions.

What is already known on this subject?

In patients undergoing coronary revascularisation via percutaneous coronary intervention, sleep apnoea is associated with increased adverse cardiovascular outcomes. There are limited studies examining the association between sleep apnoea and cardiovascular outcomes in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. These studies used different definitions, had small sample sizes and yielded equivocal results.

What might this study add?

To date, this study examining the association between sleep apnoea and cardiovascular outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting is the largest study. This study is the only study to date powered to detect a difference in cardiovascular outcomes.

This study showed that more than half of all patients undergoing non-emergent coronary artery bypass grafting had sleep apnoea. Sleep apnoea was predictive for the primary endpoint of cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke and unplanned revascularisation. Sleep apnoea was also predictive for heart failure hospitalisations.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Our data suggest the importance of detection and management of sleep apnoea in patients undergoing coronary revascularisation in order to improve cardiovascular outcomes.

Footnotes

Presented at: The abstract of this paper was presented at the annual European Society of Cardiology Congress 2019 and published in the European Heart Journal, volume 40, issue supplement_1, October 2019, ehz745.1108.

Contributors: CYK and CHL were the chief investigators and designed the trial. ZC and WK adjudicated the study endpoints. ATA, HWS, WWT, CFG and KAT monitored the data and performed the analyses. GSK, VS, PJLO, PK, AMR, HCT and TK provided critical feedback on the study design and activities. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding: This study was supported by a Transition Award and Clinician Scientist Award from the National Medical Research Council of Singapore (award numbers: NMRC/TA/012/2012; NMRC/CSA-INV/002/2015).

Disclaimer: Easmed provided support for the overnight sleep studies but had no role in the study design, data interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the local institutional review board (Domain Specific Review Board-C, National Healthcare Group).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. European Heart Network European cardiovascular disease statistics, 2017. Available: http://www.ehnheart.org/cvd-statistics/cvd-statistics-2017.html [Accessed 22 Mar 2019].

- 2. Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. . Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2019 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation 2019;139:e56–66. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Head SJ, Milojevic M, Taggart DP, et al. . Current practice of state-of-the-art surgical coronary revascularization. Circulation 2017;136:1331–45. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, et al. . Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:687–98. 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30198-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, et al. . European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The fifth joint Task force of the European Society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J 2012;33:1635–701. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task force on perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology 2014;120:268–86. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sánchez-de-la-Torre M, Campos-Rodriguez F, Barbé F. Obstructive sleep apnoea and cardiovascular disease. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1:61–72. 10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70051-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee C-H, Sethi R, Li R, et al. . Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 2016;133:2008–17. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xie C, Zhu R, Tian Y, et al. . Association of obstructive sleep apnoea with the risk of vascular outcomes and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013983 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Uchôa CHG, Danzi-Soares NdeJ, Nunes FS, et al. . Impact of OSA on cardiovascular events after coronary artery bypass surgery. Chest 2015;147:1352–60. 10.1378/chest.14-2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao L-P, Kofidis T, Lim T-W, et al. . Sleep apnea is associated with new-onset atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Crit Care 2015;30:1418.e1–5. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nagappa M, Ho G, Patra J, et al. . Postoperative outcomes in obstructive sleep apnea patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Anesth Analg 2017;125:2030–7. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rupprecht S, Schultze T, Nachtmann A, et al. . Impact of sleep disordered breathing on short-term post-operative outcome after elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a prospective observational study. Eur Respir J 2017;49:1601486 10.1183/13993003.01486-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan MTV, Wang CY, Seet E, et al. . Association of unrecognized obstructive sleep apnea with postoperative cardiovascular events in patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2019;321:1788–98. 10.1001/jama.2019.4783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koo CY, group Sstudy. P4732Sleep apnoea and cardiovascular events after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Eur Heart J 2019;40:P4732 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz745.1108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, et al. . Using the Berlin questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:485–91. 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991;14:540–5. 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yalamanchali S, Farajian V, Hamilton C, et al. . Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea by peripheral arterial tonometry: meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;139:1343–50. 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.5338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hicks KA, Mahaffey KW, Mehran R, et al. . 2017 cardiovascular and stroke endpoint definitions for clinical trials. Circulation 2018;137:961–72. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Loo G, Tan AY, Koo C-Y, et al. . Prognostic implication of obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed by post-discharge sleep study in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome. Sleep Med 2014;15:631–6. 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the Subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509. 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. . Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American heart Association/american College of cardiology Foundation scientific statement from the American heart association Council for high blood pressure research professional education Committee, Council on clinical cardiology, stroke Council, and Council on cardiovascular nursing. in collaboration with the National heart, lung, and blood Institute national center on sleep disorders research (National Institutes of health). Circulation 2008;118:1080–111. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.189375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jaiswal SJ, Topol EJ, Steinhubl SR. Digitising the way to better sleep health. Lancet 2019;393:639 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30240-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Corral J, Sánchez-Quiroga Maria-Ángeles, Carmona-Bernal C, et al. . Conventional polysomnography is not necessary for the management of most patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnea. Noninferiority, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:1181–90. 10.1164/rccm.201612-2497OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McEvoy RD, Antic NA, Heeley E, et al. . Cpap for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med 2016;375:919–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Foldvary-Schaefer N, Kaw R, Collop N, et al. . Prevalence of undetected sleep apnea in patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery and impact on postoperative outcomes. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11:1083–9. 10.5664/jcsm.5076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]