Abstract

Purpose

The lens uses circulating fluxes of ions and water that enter the lens at both poles and exit at the equator to maintain its optical properties. We have mapped the subcellular distribution of the lens aquaporins (AQP0, AQP1, and AQP5) in these water influx and efflux zones and investigated how their membrane location is affected by changes in tension applied to the lens by the zonules.

Methods

Immunohistochemistry using AQP antibodies was performed on axial sections obtained from rat lenses that had been removed from the eye and then fixed or were fixed in situ to maintain zonular tension. Zonular tension was pharmacologically modulated by applying either tropicamide (increased) or pilocarpine (decreased). AQP labeling was visualized using confocal microscopy.

Results

Modulation of zonular tension had no effect on AQP1 or AQP0 labeling in either the water efflux or influx zones. In contrast, AQP5 labeling changed from membranous to cytoplasmic in response to both mechanical and pharmacologically induced reductions in zonular tension in both the efflux zone and anterior (but not posterior) influx zone associated with the lens sutures.

Conclusions

Altering zonular tension dynamically regulates the membrane trafficking of AQP5 in the efflux and anterior influx zones to potentially change the magnitude of circulating water fluxes in the lens.

Keywords: lens, water transport, immunohistochemistry, AQP0, AQP1, AQP5, zonular tension

The transparency and refractive properties of the lens are established and maintained by its unique cellular structure and function.1 Structurally, the lens is attached to the ciliary body via the lens zonules and is bathed on its anterior and posterior surfaces by the aqueous and vitreous humors, from which it exchanges nutrients and waste products. Underneath the capsule, the anterior surface of the lens is covered by a single layer of epithelial cells that, at the equatorial margins, divide and differentiate into lens fiber cells that make up the bulk of the lens (Fig. 1A). These fiber cells undergo a process of differentiation that involves not only a change of the molecular profile of the newly differentiated fiber cells but also a massive increase in cell membranes as the fiber cells elongate toward both poles of the lens. This process continues until either the apical or basal membrane tips of the fibers meet with the membrane tips of fiber cells from the adjacent hemisphere to form the anterior and posterior sutures, respectively.2 As fiber cells differentiate, they lose their light-scattering organelles and internalize older fiber cells into the lens core or nucleus. Since this process occurs throughout life, a gradient of fiber cell age is established, with the oldest fiber cells in the lens nucleus having been laid down during embryogenesis. Since the lens lacks a blood supply, it instead operates an internal microcirculation system (Fig. 1A) that acts to maintain the transparency and refractive properties of the lens by delivering nutrients, removing waste products, and controlling the volume of lens fiber cells.3 This internal microcirculation is generated by circulating ionic and fluid fluxes that enter the lens at both poles via an extracellular pathway, associated with the lens sutures, which directs ions and water toward the deeper regions of the lens (Fig. 1A). Ions and water then cross fiber cell membranes before returning to the lens surface via an intercellular outflow pathway mediated by gap junctions. The gap junctions direct the outflow of ions and water to the lens equator, where the Na+ pumps, which generate the circulating flux of Na+ ions that drive the microcirculation system, and other ion and water channels are localized, allowing ions and water to cross the membranes of surface cells and leave the lens.

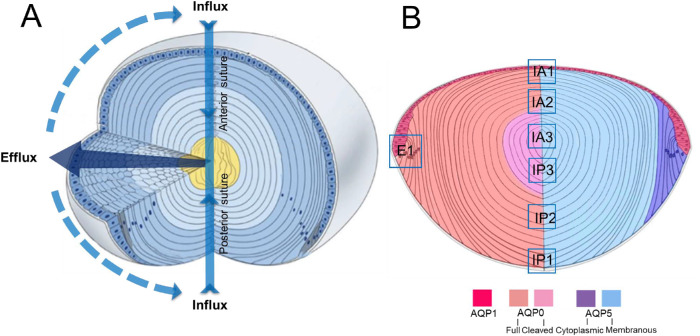

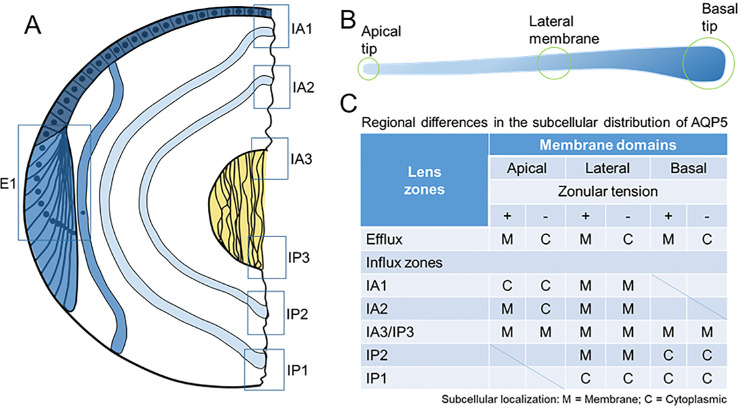

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams illustrating lens structure and function and the distribution of AQPs in different regions of the lens. (A) Three-dimensional diagram of the lens showing ion and water fluxes coming into the lens core (yellow) via an extracellular route located at the anterior and posterior sutures (blue arrows). Ions and water cross fiber cell membranes before traveling via an intercellular pathway mediated by gap junction channels (dark blue arrow) to exit the lens at the equator. (B) Diagram of an axial section of the lens showing subcellular distributions of the lens water channels (AQP) in the different regions of the lens. AQP1 (red) is restricted to the membranes of the lens epithelium. AQP0 (left) is found in the membranes of lens fiber cells across all areas of the lens, but in the core of the lens, the C-terminal tail is cleaved. AQP5 (right) is also found throughout all regions of the lens, but in the epithelial (not shown) and peripheral differentiating fiber (purple) cells, it is associated with the cytoplasm. In deeper regions of the outer cortex, AQP5 becomes associated with the plasma membrane (blue), and this labeling extends into the lens core. In this study, we focused on the subcellular distributions of the three lens AQPs at the equator, which is associated with water efflux (E1), and the anterior (IA1, IA2, IA3) and posterior (IP1, IP2, IP3) poles, which mediate water influx. Adapted with permission from Shi Y, Barton K, De Maria A, Petrash JM, Shiels A, Bassnett S. The stratified syncytium of the vertebrate lens. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1607–1615.

The intercellular outflow of water through the gap junction generates a substantial hydrostatic pressure gradient4 that is not only remarkably similar among different species of lens5 but also highly regulated by a dual-feedback pathway.6 This pathway uses the mechanosensitive nonselective ion channels TRPV1 and TRPV4 to sense changes in lens pressure and to activate signaling pathways that reciprocally modulate the activity of Na+ pumps at the lens equator to ensure the pressure gradient is maintained constant. More recently, Chen et al.7 have shown that altering the zonular tension applied to the lens can alter this constant hydrostatic pressure set point. Thus, while it is apparent that alterations in ionic/osmotic gradients, via modulation of Na+ pump activity, change the flow of water (pressure) through the lens, whether the permeability of lens cells to water is also modulated in parallel to changes in the osmotic gradient has yet to be determined.

As in other tissues, the water permeability (PH2O) of lens cell membranes is determined by the profile of the different aquaporin (AQP) proteins that are expressed in the different regions of the lens.8 Three different water channels, AQP0, AQP1, and AQP5 (Fig. 1B), all with very different PH2O and regulatory properties, are differentially expressed in the lens.9–11 AQP1, a constitutively active water channel with a high PH2O, is found only in the epithelium.11,12 AQP0, the most abundant membrane protein in the lens, is found only in the fiber cells.13 AQP0 is actually a relative poor water channel9,14,15 but has been shown to have additional roles as an adhesion protein16–18 and a scaffolding protein,19,20 and it undergoes extensive posttranslational cleavage of its C-terminal tail in mature fiber cells.15,21,22 AQP5, in other tissues, has been shown to act as a regulated water channel with a relatively high PH2O, which, when inserted into the membrane, increases the PH2O of epithelial cells.23–26 In the lens, immunohistochemical mapping of the subcellular distribution of AQP5 has shown it to be expressed in both the epithelium and throughout the fiber cell mass.22,27 In peripheral fiber cells, it is initially found as a cytoplasmic pool of protein that undergoes a transition to the membrane as fiber cells differentiate and become internalized. However, unlike AQP0, AQP5 does not undergo extensive cleavage of its C-terminus in the lens nucleus.22

In this study, we have mapped the subcellular distribution of the three lens AQPs to determine whether changes in PH2O contribute to the observed modulation of water transport. We have focused on their relative distributions at the equator and both poles, the regions of the lens involved in water efflux and influx, respectively. Furthermore, in an effort to induce changes in PH2O, we have modified zonular tension, which alters hydrostatic pressure,7 and have used immunohistochemistry to visualize induced changes in the subcellular location of the AQPs in the water efflux and influx zones. Our results suggest that dynamic changes in the subcellular location of AQP5 may differentially alter the PH2O of fiber cell membranes in the efflux and influx zone and therefore may contribute to the regulation of water transport in the lens.

Methods

Reagents

A polyclonal affinity purified anti-AQP0 antibody, directed against the last 17 amino acids of the C-terminus of the human protein, was obtained from Alpha Diagnostic International (San Antonio, TX, USA, catalogue number AQP01-A). An affinity purified polyclonal anti-AQP5 antibody, directed against the last 17 amino acids of the C-terminus of the rat protein, was obtained from Merck Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany, catalogue number AB15858). A rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the last 19 amino acids of the C-terminus of the rat AQP1 protein was purchased from Alpha Diagnostic International. Secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488) and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) conjugated to a fluorophore (WGA–Alexa 594) for labeling of the cell membrane were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). For labeling of the epithelial and fiber cell nuclei, DAPI was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was prepared fresh from PBS tablets. Lenses were organ cultured in artificial aqueous humor (AAH) that consisted of (in mM) 125 NaCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 4.5 KCL, 10 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 5 glucose, 10 sucrose, 10 HEPES (pH 7.4), and 300 mOsml/L. Tropicamide and pilocarpine were used at 1:5 dilution prepared in AAH buffer from 1% w/v eye drops. Unless otherwise stated, all other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Lens Organ Culture

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and approved by the University of Auckland Animal Ethics Committee (# 001893). Eyes were enucleated from 21-day-old Wistar rats and subjected to three different preparation protocols that yielded lenses that were either separated from, or attached to, the ciliary muscle by the zonules. In the first preparation, lenses were separated from the ciliary body by completely removing the lens from the eye. To achieve this, four radiating incisions from the optic nerve head toward the limbus were first made to expose the lens and ciliary body. To release the lens, the zonules were cut with a pair of surgical scissors, the lens was removed from the eye using a glass loop, and the excised lens was organ cultured in AAH for up to 120 minutes before immersing in 0.75% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) prepared in PBS (pH 7.4) and fixed overnight at room temperature. In the second preparation, lenses were prepared with the zonules attached by first cutting a small (∼2 mm) hole into the cornea of the enucleated eye, to provide a pathway to perfuse the lens with AAH in the absence or presence of either tropicamide or pilocarpine. Lenses were maintained in organ culture for up 120 minutes at 37°C in a CO2 incubator (Heracell 150i; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Tropicamide causes a relaxation of the ciliary muscle and increases the tension applied to the lens via the zonules, while pilocarpine, by inducing a contraction of the ciliary muscle, reduces the tension applied to the lens via the zonules. After organ culture, the preparation was perfused with 0.75% PFA and maintained at room temperature overnight to fix the lens in situ. After fixation, lens was dissected free from the surrounding tissue and processed for immunohistochemistry.

The third preparation was used to confirm the ability of tropicamide and pilocarpine to alter zonular tension. The drugs were diluted in AAH and applied to the corneal surface of enucleated eyes, and the native three-dimensional structure of the ciliary body, zonules, and lens was preserved by fixing the eyes in 4% paraformaldehyde while maintaining the intraocular pressure at 18 mmHg28 using the method described by Bassnett.29 After fixation, the posterior sclera and retina were removed, and the ciliary body and lens were photographed using a stereo microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). The distance between the two structures was measured using image analysis software (Adobe Photoshop CC; Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). For each lens, ∼25 measurements were taken to calculate the mean circumferential space distance from at least three different lenses incubated in the absence and presence of either tropicamide or pilocarpine.

Immunohistochemistry

Fixed lenses were washed three times in PBS (pH 7.4) for 10 minutes and cryoprotected using three consecutive incubations in 10% and 20% sucrose for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by an overnight incubation in 30% sucrose at 4°C.30 Cryoprotected lenses were positioned on chucks in an axial orientation, encased in optimal temperature medium (OCT, Sakura Finetek Japan, Tokyo, Japan), and snap frozen for 15 seconds in liquid nitrogen. Axial sections were cut using a Leica CM3050S cryostat (Leica Biosystems), and consecutive sections of ∼14 µm thickness were collected from at least three lenses for each experimental condition to ensure consistency of immunolabeling results. Sections were washed three times for 5 minutes in PBS (pH 7.4) and blocked for 1 hour in blocking solution (3% normal goat serum, 3% BSA dissolved in PBS, pH 7.4). Excess blocking solution first was removed using tissue paper before incubating sections in different anti-AQP primary antibodies diluted 1:100 in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed three times for 5 minutes in PBS (pH 7.4) to remove unbound antibody before incubating sections with a goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488 secondary antibody for 3 hours at room temperature. After washing the secondary antibody three times in PBS (pH 7.4) for 5 minutes, sections were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour in the membrane marker WGA and the nucleus marker 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (0.25 µg/mL), diluted 1:100 and 1:1000 in PBS (pH 7.4), respectively. After a final wash in PBS (pH 7.4), sections were mounted with a cover slip using an antifading agent (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, San Diego, CA, USA) and imaged using either an Olympus FV1000 Fluoview (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) confocal scanning microscope or a Nikon LSM800 with Airyscan superresolution microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The resultant two-dimensional images were prepared using Adobe Photoshop CC software. Three-dimensional reconstruction of fiber cells was performed using Fiji software (a distribution of ImageJ; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), an open-source image-processing platform.

Statistical Analysis

Experimental means are given as ± standard error of the mean (SE). Statistical significance was tested with the Mann-Whitney U test, using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was set at the α = 0.05 level.

Results

In previous studies, we have mapped the distribution of AQP021 and AQP522 from the periphery to the center of the lens using sections taken through the equator of the rodent lenses, which were removed from the eye by cutting the zonules that attach the lens to the ciliary body. In this study, we have used axial sections to map the subcellular distribution of AQPs in the rat lens as this orientation allows us to visualize, in the same section, the anterior and posterior poles of the lens that mediate water influx, as well as the lens equator where water efflux occurs (Fig. 1). Furthermore, to determine the effects of changes in zonular tension on the subcellular distribution of AQPs, axial sections were obtained from lenses that had been subjected to mechanical and pharmacologic manipulations to alter the tension applied to the lens via the zonules. The effects of altering zonular tension on the subcellular localization of the three major AQPs (APQ1, APQ0, and APQ5) in the water efflux and influx pathways are presented in turn.

Subcellular Distribution of Lens AQPs in the Equatorial Water Efflux Zone

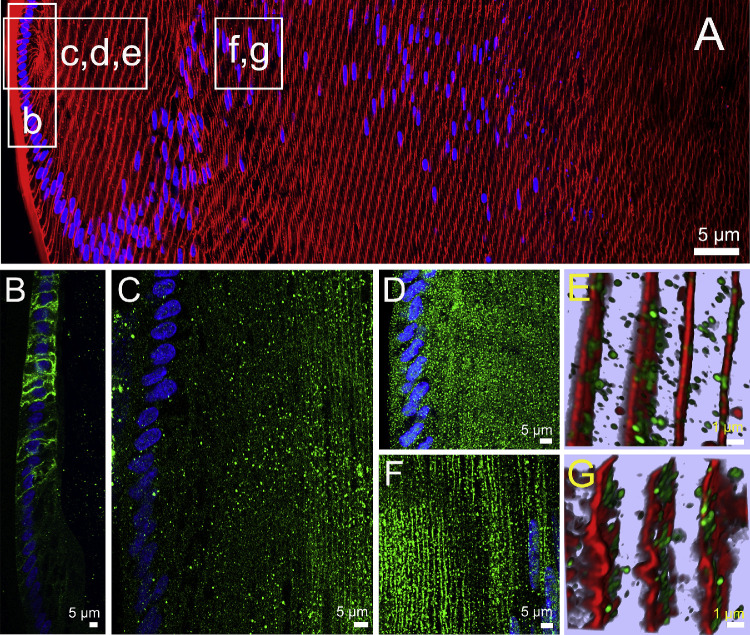

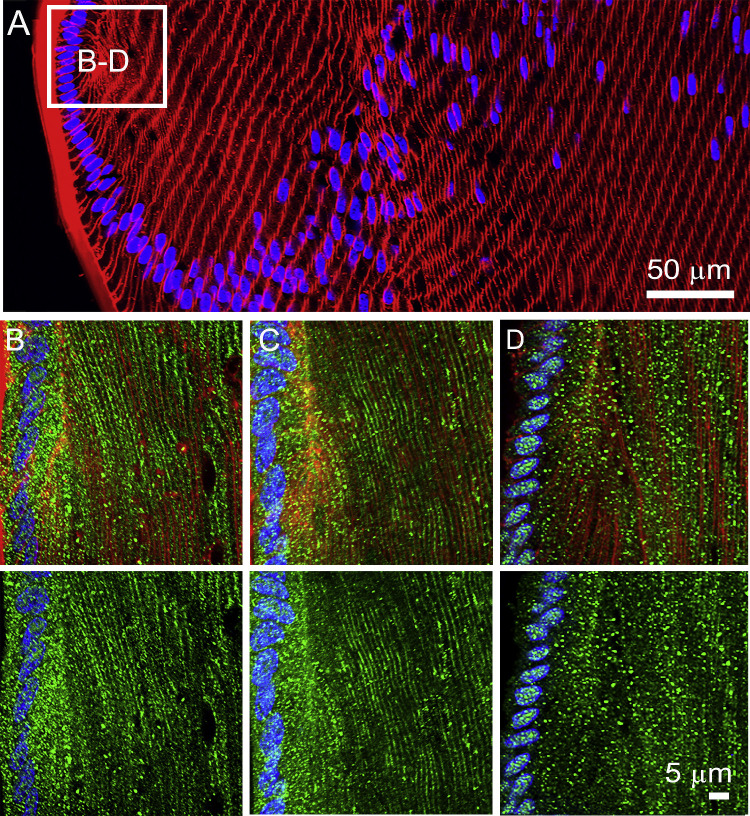

As epithelial cells at the lens equator initiate the process of differentiation into fiber cells in the water efflux zone, they change their AQP expression profile (Fig. 2). As had been shown previously in lenses removed from the eye by cutting the zonules, AQP1 was expressed only in the epithelial cells that cover the anterior surface of the lens,12 with AQP1 labeling being strongly localized to the apical and lateral membrane domains of the cells (Fig. 2B). However, as the epithelial cells elongated into fiber cells, AQP1 labeling abruptly disappeared and was completely lacking in secondary fiber cells (Fig. 2B). In contrast to AQP1, AQP0 protein was not detected in epithelial cells and initially only observed in the newly derived elongating fiber cells as a cytoplasmic punctate labeling pattern, with strong membranous labeling only becoming apparent in fiber cells ∼20 to 25 cell layers in from the capsule (Fig. 2C). AQP5 labeling was initially predominately cytoplasmic in both the epithelial and newly differentiated fiber cells (Figs. 2D, 2E) before becoming localized to the membranes of secondary fiber cells ∼150 to 200 μm in from the capsule in an area just past the bow region where cell nuclei disperse (Figs. 2F, 2G). In summary, we see a change in expression from AQP1 to AQP0 as epithelial cells differentiate into fiber cells, while AQP5 is expressed in both cell types. In the efflux zone, both AQP1 and AQP0 show an exclusive membrane localization that suggests they both contribute to PH2O in this zone, while the localization of AQP5 in the cytoplasm indicates AQP5 is not actively contributing to the PH2O of epithelial cells and peripheral fiber cells in the efflux zone. However, in deeper differentiating fiber cells, the insert of AQP5 in the plasma membrane indicates that in these cells, it does contribute to PH2O.27

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization of lens AQPs in the efflux zone of rat lenses in the absence of zonular tension. (A) Image montage of the water efflux zone taken from an axial section of a rat lens that had been removed from the eye by first cutting the zonules and was then placed immediately into fixative. The section was labeled with the membrane marker WGA (red) and the nuclei marker DAPI (blue). Boxes indicate the areas from which the higher resolution two-dimensional images (B, C, D, F) or three-dimensional airy scan images (E, G) were taken from to investigate the subcellular distribution for each lens AQP (green). (B) AQP1 labeling is localized to the membranes of the epithelial cells but disappears as the epithelial cells differentiate into fiber cells. (C) AQP0 labeling was absent from epithelial cells but became apparently initially as diffuse punctate labeling as epithelial cell differentiated into fiber cells and in later stages of fiber cells differentiation was found strongly associated with the membranes of these deeper localised secondary fiber cells. (D) AQP5 labeling was initially associated with the cytoplasm in the epithelial cells and newly differentiated fiber cells being localized in cytoplasmic vesicles (E). (F) In deeper differentiating fiber cells ∼150 µm in from the capsule, AQP5 labeling became membranous and the number of cytoplasmic vesicles was dramatically reduced (G).

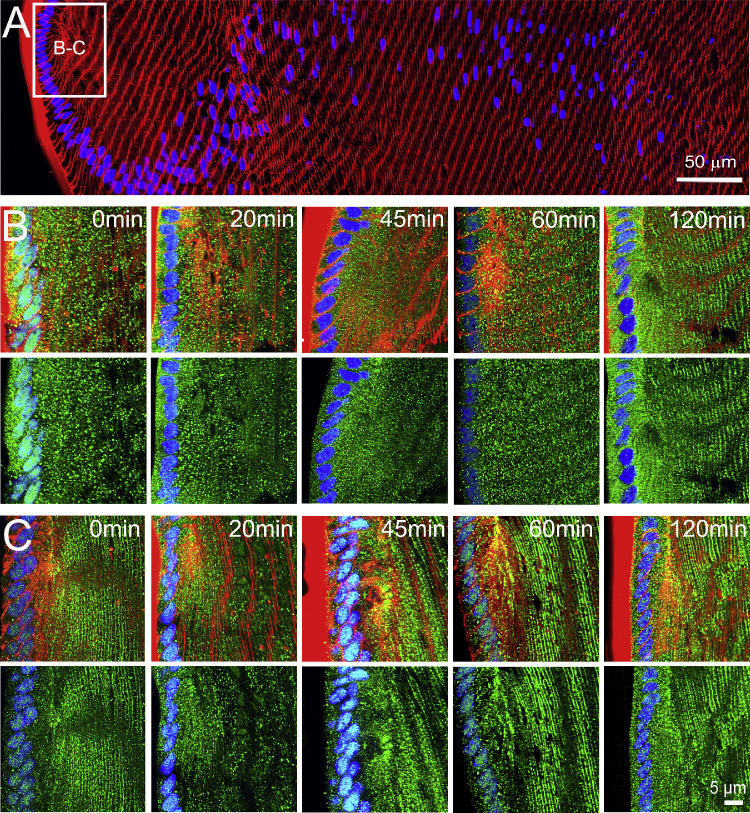

To determine whether altering zonular tension changes the subcellular distribution of the lens AQPs, we organ cultured rat lenses either ex vivo (no zonules) or in situ (with zonules) for different periods of time before fixing the lenses for immunohistochemistry. The pattern of AQP1 (Fig. 2B) and AQP0 (Fig. 2C) labeling observed in lenses organ cultured in lenses with no zonules attached was not altered in lenses with zonules attached (data not shown). However, the subcellular labeling patterns observed for AQP5 were different in lenses maintained in ex vivo or in situ organ culture (Fig. 3). Lenses, maintained in ex vivo organ culture after having their zonules cut, showed an initial predominantly cytoplasmic subcellular localization of AQP5 in both epithelial and fiber cells for up to the first 45 minutes in culture. Then, over the next 60 to 120 minutes, the labeling became increasingly associated with the plasma membrane of peripheral fiber cells in the water efflux zone (Fig. 3B). In contrast, lenses that were fixed in situ, with their zonules intact, exhibited predominately membranous AQP5 labeling in fiber cells throughout the efflux zone that did not change during the entire 120 minutes of organ culture (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results suggest that AQP5 in the water efflux zone is normally membranous and that reducing zonular tension results in the rapid removal of AQP5 from the membrane.

Figure 3.

Effects of mechanically altering zonular tension on the subcellular localization of AQP5 in the efflux zone of the rat lens. (A) Image montage of the water efflux zone taken from a representative axial section of a rat lenses labeled with the membrane marker WGA (red) and the nuclei marker DAPI (blue). The box indicates the area from which high-resolution images (B, C) were captured to monitor the time course of changes to the subcellular distribution of AQP5 (green) over a period of up to 120 minutes, in lenses that had been removed from the eye by cutting the zonules (B), or in lenses maintained in situ with their zonules intact (C). Top panels in B and C show nuclei, membrane, and AQP5 labeling, while bottom panels show only nuclei and AQP5 labeling. In lenses maintained in organ culture with their zonules cut (B), the subcellular localization of AQP5 changes from a cytoplasmic to a membranous labeling pattern over time. In lenses in which the zonular tension is maintained (C), AQP5 labeling is associated with the membrane, and this labeling does not change over time in organ culture.

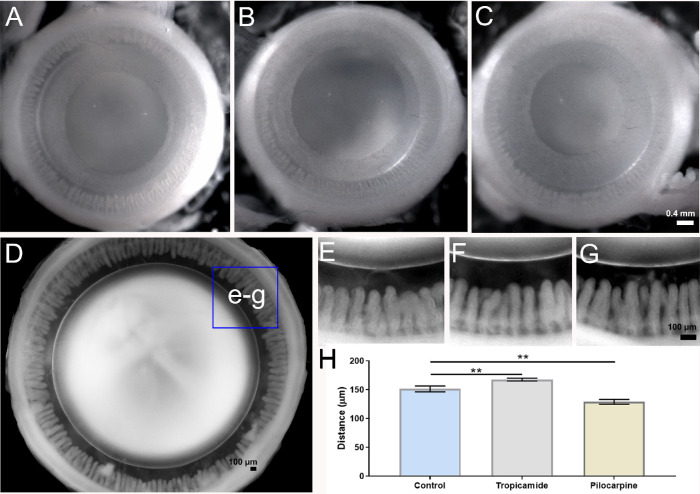

To further test this notion, we incubated enucleated eyes in the absence or presence of either tropicamide or pilocarpine to pharmacologically manipulate iris and ciliary muscle contractility, in order to alter the tension applied to the lens in situ via the zonules (Fig. 4). As expected, tropicamide (Fig. 4B) and pilocarpine (Fig. 4C) evoked dilation and constriction, respectively, of the pupil of the enucleated rat eye, confirming the functionality of drugs on the muscles of the iris. To assess the functionality of the drugs on the ciliary muscle, we first fixed the entire globe before removing the posterior tissues of the eye to reveal the ciliary body and lens in order to allow the distance between the ciliary process and lens, the circumlental space, to be measured. Under control conditions, the circumlental space was 151.51 ± 2.3 µm (n = 5), which was significantly increased in the presence of tropicamide by 11% to 167.67 ± 1.4 µm (n = 3), and significantly decreased by 14% to 129.03 ± 2.5 µm after incubation in pilocarpine (n = 3) (Fig. 4H). Having demonstrated that we could pharmacologically modulate ciliary muscle contractility to alter the distance between the ciliary processes and the lens, we used these pharmacological tools to alter the tension applied to the lens via the zonules.

Figure 4.

Pharmacologic modulation of zonular tension of the rat lens. (A–C) Images looking down on the anterior surface of enucleated rat eyes showing the pupil diameter in untreated eyes (A) and the increase and decrease following treatment with either tropicamide (B) or pilocarpine (C), respectively, for 60 minutes. (D–G) Eyes were then fixed and the posterior sclera and retina removed to visualize the circumlental space (D, E) and how it increased and decreased following treatment with either tropicamide (F) or pilocarpine (G). (H) Summary of measurements taken from high-power images showed that in control eyes (E), the distance between ciliary processes and the lens was 151.51 ± 2.3 µm (mean ± SE). In eyes treated with 0.2% tropicamide (J), the circumlental space was increased to 167.67 ± 1.4 µm (mean ± SE). In eyes treated with 0.2% pilocarpine (I), the circumlental space was reduced to 129.03 ± 2.5 µm (mean ± SE). These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Statistical analysis was performed with a Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.05 for each tested group.

If the assumption that ciliary muscle contractility alters zonular tension in our experimental model is true, we would expect that narrowing of the circumlental space induced by pilocarpine should have a similar effect on the subcellular distribution of AQP5 as that seen in lenses fixed immediately after having their zonules mechanically cut to release the tension applied to the lens. To test this hypothesis, immunohistochemistry for AQP5 was performed on lenses fixed in situ following incubation in the absence or presence of either tropicamide or pilocarpine (Fig. 5). We found that increasing the tension applied to the lens via the zonules by the application of tropicamide had no effect on the membrane location of AQP5 (Fig. 5C) compared to control lenses with intact zonules (Fig. 5B). In contrast, eyes incubated in pilocarpine that reduces the tension applied to the lens exhibited AQP5 labeling that was predominately associated with the cytoplasm of fiber cells in the water efflux zone (Fig. 5D). In summary, it appears that both mechanically and pharmacologically reducing the tension applied to the lens switches AQP5 labeling from the membrane to cytoplasm, which suggests AQP5 functionality can be dynamically regulated to alter water efflux at the lens equator. In the next sections, we investigate whether similar changes in the subcellular distribution of lens AQPs occurred in the water influx zones located at the anterior and posterior poles.

Figure 5.

Effects of pharmacologically altering zonular tension on the subcellular localization of AQP5 in the efflux zone of the rat lens. (A) Image montage of the water efflux zone taken from a representative axial section of a rat lens labeled with the membrane marker WGA (red) and the nuclei marker DAPI (blue). The box indicates the area from which high-resolution images (B–D) were captured in lenses maintained in situ with their zonules intact. (B–D) Top panels show nuclei, membrane, and AQP5 labeling, while bottom panels show only nuclei and AQP5 labeling from control lenses (B) and lenses incubated in tropicamide (C) or pilocarpine (D) for 60 minutes. Note the shift from membranous labeling to cytoplasmic labeling following incubation on pilocarpine.

Subcellular Distribution of Lens AQPs in the Water Influx Zone

Experiments that have used Ussing chambers31 and magnetic resonance imaging measurements of heavy water penetration into the lens32 have shown that water preferentially enters the lens at its anterior and posterior poles. At the poles, fiber cells from adjacent hemispheres meet to form the lens sutures,2 which in the rat lens form a Y-shaped structure. The sutures form an extracellular pathway that links the mature fiber cells in the center of the lens to the aqueous and vitreous humors that bathe the anterior and posterior poles of the lens, respectively. As such, the sutures represent a pathway to direct ion and fluid movement toward the internalized mature fiber cells.33 In axial sections, it is possible to visualize the sutures as a line extending from the surface to the core of the lens, but it is difficult to observe the anterior and posterior sutures in the same section as they are offset from each other by 60°.34 In this study, we have investigated the distribution of the AQPs in anterior (IA) and posterior (IP) influx zones by mapping the subcellular distribution of the three AQPs along the two suture lines that extend from the anterior and posterior poles to the lens core. To facilitate this comparison, we have designated three spatial regions in the outer cortex (IA1; IP1), inner cortex (IA2; IP2), and core (IA3; IP3) from which higher-resolution images have been taken to enable comparison between the labeling obtained from lenses exposed to different degrees of zonular tension (Fig. 1B). Results from the anterior and posterior poles are presented in turn.

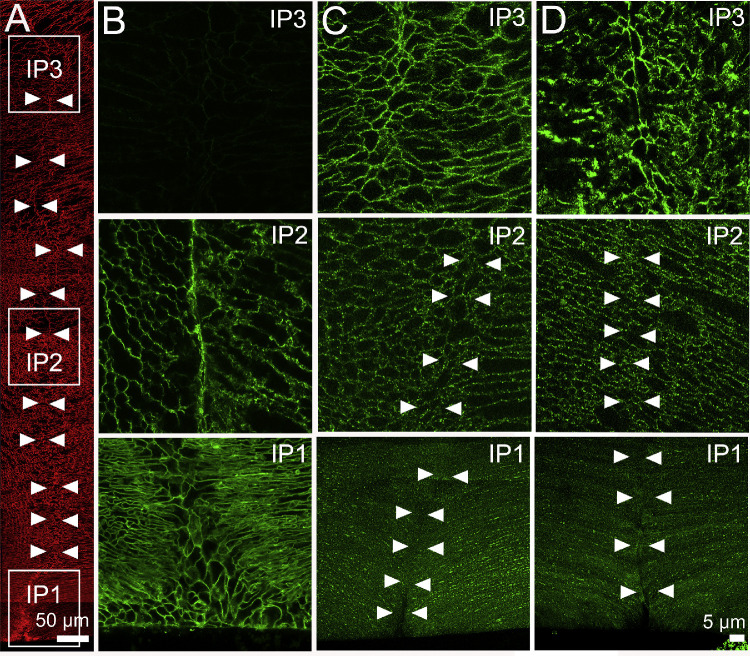

AQP Distributions Along the Posterior Suture. Since AQP1 is not present in the fiber cells below the germinative zone, we examined only the distribution of AQP0 and AQP5 in the posterior influx zone. We found that in lenses with their zonules cut, AQP0 was localized to the lateral membranes of fiber cells and was concentrated in the basal tips of fibers that interact to form the sutures in the outer cortex of the lens (Fig. 6B, IP1). In contrast, AQP5 was cytoplasmic with intermittently sparse clusters of puncta on the lateral membranes of fiber cells, but no localization of AQP5 was observed at the basal tips of fiber cells that interface to form the posterior suture (Fig. 6C, IP1). In the inner cortex, AQP0 remained membranous and associated with the suture, while AQP5 was predominately associated with lateral membranes but not the posterior suture (Figs. 6B and 2C, IP2). In mature fiber cells located in the lens core, AQP0 labeling was abolished, as expected by the C-terminal cleavage of the AQP0 protein as AQP0 protein undergoes a cleavage of its cytoplasmic C-terminus tail, which removes the epitope detected by the AQP0 antibody used in this study.21 In contrast, strong AQP5 labeling was associated with both the lateral membranes and the sutures in the lens nucleus (Figs. 6B and 2C, IP3). Repeating these experiments using lenses fixed in situ to maintain zonular tension had no effect on the subcellular distribution of AQP0 (data not shown) or AQP5 (Fig. 6D) in all regions of interest in the posterior water influx zone. Similarly, pharmacologic modulation of zonular tension using tropicamide or pilocarpine had no effect on the distribution of AQP5 in the posterior influx zone (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Subcellular localization of lens AQP0 and AQP5 in the influx zone of rat lenses—results from the posterior pole. (A) Image montage of the posterior water influx zone taken from an axial section of a rat lens that was labeled with the membrane marker WGA (red) to highlight suture line (arrowheads). Boxes indicate the areas (IP1, IP2, and IP3) from which the higher-resolution images shown in B–D were taken to investigate the subcellular distribution of AQP0 and AQP5 (green). (B) In lenses with cut zonules, AQP0 labeling was membranous and strongly labeled the suture in regions IP1 and IP2, but no labeling was observed from region IP3 in the lens core where AQP0 the C-terminus of the AQP0 protein is cleaved. (C) In lenses with zonules cut, AQP5 labeling was missing from the suture in regions IP1 and IP2, but labeling was present in the deeper IP3 region. (D) Fixing lenses in situ with their zonules attached had no effect on AQP0 (data not shown) or AQP5 labeling in the posterior influx zone.

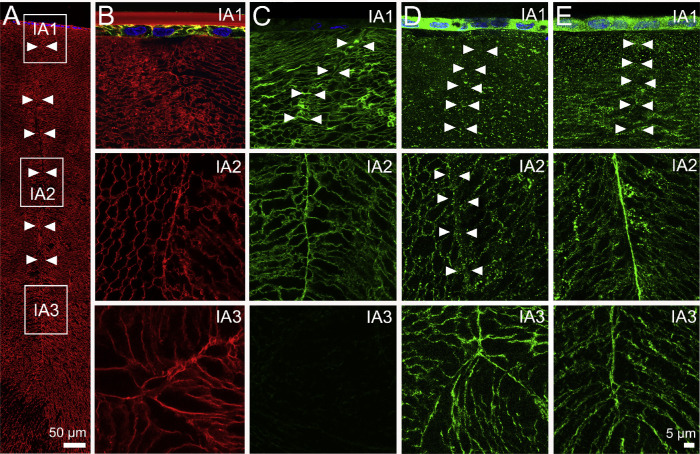

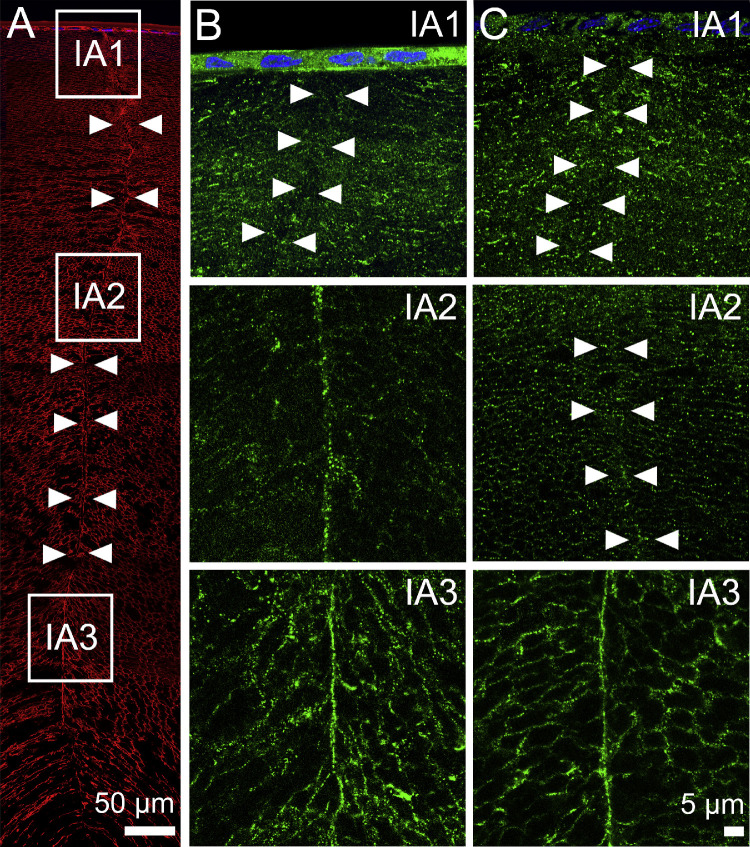

AQP Distributions Along the Anterior Suture. As shown previously for the efflux zone, AQP1 was expressed only in the epithelial cells that cover the anterior surface of the lens, and hence it was not associated with the anterior suture (Fig. 7B, IA1) or expressed in the deeper regions of the lens (Fig. 7B, IA2 and IA3). AQP0 labeling around the anterior suture was essentially similar to that seen in the posterior suture. In the outer cortex of lenses with zonules cut (Fig. 7C), AQP0 was not present in the epithelial cells, was localized to the lateral membranes of fiber cells, and was present in the sutures formed from the apical membrane domains (Fig. 7C, IA1). AQP0 labeling remained membranous in the fiber cells and strongly localized to the suture in the inner cortex (Fig. 7C, IA2). However, as expected, AQP0 labeling was not detected in the lens core due to the loss of the antibody epitope (Fig. 7C, IA3). AQP5 labeling in the anterior influx zone of lenses with their zonules cut was essentially similar to that seen in the posterior influx zone. AQP5 labeling was strongly cytoplasmic in the epithelial cells, with a mixed cytoplasmic and membranous localization in the lateral membranes of fiber cells in the outer cortex, and no labeling of the apical membranes associated with the sutures in this region of the lens (Fig. 7D, IA1). In the inner cortex, AQP5 labeling was associated with the lateral membranes but was absent from the apical tips at the sutures (Fig. 7, IA2), while in the core, AQP5 remained membranous in the lateral domains and was found strongly associated with the sutures (Fig. 7D, IA3). However, changes in zonular tension did differentially alter the AQP5 distribution in the anterior influx zone. While no changes in AQP5 labeling were seen in regions IA1 and IA3, of lenses fixed in situ with their zonules attached, an increased association of AQP5 with the sutures was observed in region IA2 (Fig. 7E). To confirm that a change in zonular tension is the underlying mechanism regulating this observed change in AQP5 labeling in this region of the anterior influx zone, we treated eyes with tropicamide or pilocarpine (Fig. 8). We found that in lenses with their zonules attached, tropicamide had no effect on AQP5 labeling in the anterior suture (Fig. 8B, IA2). However, reducing zonular tension via the application of pilocarpine abolished AQP5 labeling associated with the suture in the inner cortical region of the anterior influx zone (Fig. 8C, IA2). In summary, it appears that AQP5 is differentially associated with the apical and basal membrane domains that form anterior and posterior sutures, respectively, in the water influx zone, and in the anterior pole, this association with the apical membrane domain can be modified by changes in zonular tension.

Figure 7.

Subcellular localization of lens AQPs in the influx zone of rat lenses—results from the anterior pole. (A) Image montage of the anterior water influx zone taken from an axial section of a rat lens that was labeled with the membrane marker WGA (red) to highlight suture line (arrowheads). Boxes indicate the areas (IA1, IA2, and IA3) from which the higher-resolution images shown in B–E were taken to investigate the subcellular distribution for each lens AQP (green). (B) In lenses with cut zonules, AQP1 labeling was present only in the epithelial cells of IA1 and was absent from IA2 and IA3. (C) In lenses with cut zonules, AQP0 labeling was membranous and strongly labeled the suture in regions IA1 and IA2, but no labeling was observed from region IA3 in the lens core where the C-terminus of AQP0 protein is cleaved. (D) In lenses with zonules cut, AQP5 labeling was missing from the suture in regions IA1 and IA2, but labeling was present in the deeper IA3 region. (E) In lenses that were fixed in situ with their zonules attached, AQP5 labeling was still absent from the suture in the peripheral region IA1 but was present in regions IA2 and IA3.

Figure 8.

Subcellular distribution of AQP5 in lenses with pharmacologically modulated zonular tension at the anterior suture. (A) Image montage of the anterior water influx zone taken from an axial section of a rat lens that was labeled with the membrane marker WGA (red) to highlight suture line (arrowheads). Boxes indicate the areas (IA1, IA2, and IA3) from which the higher-resolution images shown in B and C were taken to investigate the subcellular distribution of AQP5 (green) following the application of tropicamide (B) or pilocarpine for 60 minutes. (B) Application of tropicamide did not change AQP5 labeling in the suture (compare to Fig. 6E). (C) In lenses treated with pilocarpine, AQP5 labeling was absent from the sutures of regions IA1 and IA2 but was still present at IA3.

Discussion

Cells move water by actively transporting ions and solutes to establish osmotic gradients that drive the passive diffusion of water through water channels formed from the aquaporin family of proteins.35,36 The lens expresses at least three AQPs with very different PH2O and regulation that show spatially distinct patterns of expression and posttranslational modifications. In this study, we have used immunohistochemistry to visualize the subcellular distribution of the lens AQPs in two spatially discrete areas of the lens that have been shown to be associated water influx and efflux.31,32 Our results have confirmed the restriction of AQP1 labeling to the lens epithelium (Figs. 2B, 7B), the ubiquitous labeling of AQP0 in the membranes of lens fiber cells (Figs. 2C, 6B, 7B), and the loss of AQP0 labeling in the lens nucleus due to the cleavage of the C-terminus of the AQP0 protein (Figs. 6B, 7B). In addition, we have shown that these labeling patterns for both AQP1 and AQP0 are unaffected by either mechanical or pharmacologic modulation of zonular tension. We have also confirmed the cytoplasmic labeling for AQP5 in epithelial and peripheral fiber cells (Figs. 2D, 2E) and membrane labeling in deeper fiber cells (Figs. 2F, 2G), originally observed in equatorial sections obtained from lenses removed from the eye by cutting the zonules.22 However, in addition, we have shown that this labeling pattern is altered by fixing lenses in situ to maintain the zonular tension applied to the lens (Fig. 3C). In the influx zone, we have shown that AQP5 is preferentially localized at the tips of fiber cells that form the anterior (Figs. 7D, 7E) but not the posterior sutures (Figs. 6C, 6D). Furthermore, the membrane localization of AQP5 to the anterior suture was decreased by either the mechanical (Fig. 7E, region A2) or pharmacological (Fig. 8D, region A2) reductions in zonular tension applied to the lens. These changes in the subcellular location of AQP5 in response to change in zonular tension are summarized in Figure 9. Taken together, our findings suggest AQP5 acts as a regulated water channel that can dynamically regulate the PH2O of lens fiber cells in the anterior influx and equatorial efflux zones to potentially modulate lens water transport in response to changes in zonular tension.

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of the subcellular localization of AQP5 in the efflux and influx zones of the rat lens in the presence and absence of zonular tension. (A) Epithelial cells (dark blue) that differentiate into fiber cells (blue) in the equatorial efflux zone (E1) are initially attached by their apical membrane domains to form the modiolus. As fiber cells detach from the modiolus, their apical and basal tips migrate along the epithelium and capsule, respectively, and their lateral membranes undergo massive elongation. This process of elongation continues until the apical and basal tips of fiber cells (light blue) from the opposing lens hemisphere meet to form the anterior and posterior sutures, respectively. As this process continues throughout life, newly differentiated secondary fiber cells internalize older mature fiber cells, which in turn internalize the primary fiber cells (yellow) laid down during embryonic development. Boxes represent the regions in the efflux and influx zones where the subcellular localization of AQP5 was measured. (B) Schematic representation of a fiber cell depicting its three specific membrane domains consisting of the apical tip, lateral membranes, and basal tip. (C) Table summarizing the regional differences of AQP5 subcellular localization observed in the efflux and influx zones in the presence and absence of zonular tension.

The existence of a pool of cytoplasmic membrane proteins that translocate to the plasma membrane of fiber cells, either as a function of fiber cell differentiation or dynamically in response to applied stimuli, to confer a specific function required by lens fiber cells, appears to be a recurring theme in the lens.37,38 In this study, we have shown that in lenses fixed in situ, the default subcellular location for AQP5 is the membrane, and that upon reducing the zonular tension AQP5 is removed from the membrane, presumably to reduce the PH2O of fiber cell membranes in the anterior and equatorial zones of water influx and efflux, respectively. Interestingly, this removal of AQP5 from the membrane is only transient in lenses organ cultured without their zonules attached (Fig. 3B). In an earlier study, we showed a similar increase in AQP5 membrane labeling in the equatorial efflux zone and, in addition, showed that this increase in membrane labeling was associated with an increase in the Hg+-sensitive PH2O measured in fiber membrane vesicles derived from organ-cultured rat lenses.27 This earlier study indicates that the changes in the subcellular location of AQP5 labeling observed using immunohistochemistry in the current study are associated with changes in PH2O and support the suggestion that AQP5 functions as a regulated water channel in the anterior influx and equatorial efflux zones of the rat lens.

Despite its potential contributions to the regulation of lens water transport, it was surprising to see that the deletion of the AQP5 gene did not induce a cataract in AQP5-Knockout (KO) lenses.39 However, it does appear that when AQP5-KO lenses are organ cultured under hyperglycemic conditions, they are more susceptible to the development of cataract than wild-type lenses.39 This is most probably due to the inability of the AQP5-KO lens to alter its PH2O in response to the osmotic stress induced by the hyperglycemia, supporting the suggestion that AQP5 plays a role in regulating water fluxes under both steady-state conditions and conditions of stress. Consistent with this idea, an increased expression of AQP5 was observed in epithelial cells removed from patients undergoing cataract surgery.40 In these patients, not only were the expression levels of both AQP5 and AQP1 increased, but AQP5 was found to be more strongly localized to the membranes of lens epithelial cells obtained from cataract patients relative to epithelial cells obtained from age-matched noncataractic lenses. Thus, it appears that as a regulated water channel AQP5 can respond to imposed stresses to modulate water transport in an effort to maintain fluid homeostasis and preserve lens transparency.

In other epithelial tissues, AQP5 has been also shown to act as a regulated water channel that inserts into the apical plasma membrane following phosphorylation of the channel through the cAMP-dependent PKA pathway.23 In addition, exposure to hypertonic challenge was shown to upregulate AQP5 protein expression through an extracellular signal–regulated kinase–dependent pathway in mouse lung epithelial (MLE-15) cells.25 From the current study, we can add the tension applied to the lens via the zonules as a stimulus capable of regulating the trafficking of AQP5 to the membrane. The observation of this phenomenon raises questions about how changes in zonular tension are sensed and translated to alterations in AQP5 membrane trafficking. Again, in other tissues, a synergistic association between the mechanosensitive Transient receptor potential vanilloid isoform 4 (TRPV4) and aquaporin water channels has been shown to effect changes in fluid transport to preserve cell volume.41–43 In the lens, TRPV4 and TRPV1 channels have been shown to not only reciprocally regulate the hydrostatic pressure generated by water flow through gap junction channels6 but also transduce changes to the magnitude of this pressure gradient induced by pharmacologically modulating the zonular tension applied to the lens.7 Furthermore, changes in zonular tension induced either mechanically by cutting the zonules44 or pharmacologically via application of tropicamide or pilocarpine also altered the subcellular location of TRPV1 and TRPV4 (data presented at the Sixth International Conference on the Lens by Nakazawa et al., unpublished data). Taken together, these observations suggest that in addition to the modulation of the osmotic gradients that drive the transport of water,6,45 changes to PH2O are also required to maintain the gradient in hydrostatic pressure that has been measured in all lenses studied to date.5 Finding a link between TRPV1/4-mediated signaling pathways and the membrane trafficking of AQP5 in lens fiber cells will be a focus of ongoing work.

While similar effects on the membrane localization of AQP5, and presumably the PH2O, were evident in the anterior influx and equatorial efflux zones following changes in zonular tension, AQP5 labeling in the posterior influx zone was unaffected, suggesting that changes in zonular tension may differentially affect water influx at the anterior and posterior poles. Structurally, the differences in AQP5 localization at the anterior and posterior sutures can be explained by the maintenance of the apical-basal membrane polarity of lens epithelial cells as they differentiate and elongate into fiber cells that then become internalized (Fig. 9). The anterior suture is formed by the apical domains of fiber cells that originate from opposing sides of the lens, while the basal domains form the posterior suture.46 From the current study, it would appear that in the outer and inner cortical regions of the lens, the apical domains contain AQP5, but the basal domains do not (Figs. 6 and 7). Interestingly, in the oldest fiber cells in the lens nucleus, this apical-basal polarity is lost and AQP5 is associated with the posterior suture in the nucleus (Fig. 7, IP3). This change could be associated with the loss of components of the lens cytoskeleton in the lens nucleus that mediate the anchoring of membrane proteins to specific membrane domains.47–51

In summary, using a series of simple immunohistochemical labeling experiments, guided by our knowledge of water transport in the lens, we have shown that a decrease in zonular tension removes AQP5 from the membranes of fiber cells in the equatorial water efflux zone and the anterior water influx zones. Studying how these observations affect the regulation of lens water transport, which is emerging as being essential to the maintenance of the transparent and refractive properties of the lens, has the potential to increase our understand of not only the normal function of the lens but also how dysfunction of lens water transport can result in lens cataract.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund (16-UOA-251) and the National Eye Institute USA (EY013462-16).

Disclosure: R.S. Petrova, None; N. Bavana, None; R. Zhao, None; K.L. Schey, None; P.J. Donaldson, None

References

- 1. Bassnett S, Shi Y, Vrensen GFJM. Biological glass: structural determinants of eye lens transparency. Phil Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2011; 366: 1250–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kuszak JR, Zoltoski RK, Tiedemann CE. Development of lens sutures. Int J Dev Biol. 2004; 48: 889–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mathias RT, Kistler J, Donaldson P. The lens circulation. J Membrane Biol. 2007; 216: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gao J, Sun X, Moore LC, White TW, Brink PR, Mathias RT. Lens intracellular hydrostatic pressure is generated by the circulation of sodium and modulated by gap junction coupling. J Gen Physiol. 2011; 137: 507–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gao J, Sun X, Moore LC, Brink PR, White TW, Mathias RT. The effect of size and species on lens intracellular hydrostatic pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gao J, Sun X, White TW, Delamere NA, Mathias RT. Feedback regulation of intracellular hydrostatic pressure in surface cells of the lens. Biophys J. 2015; 109: 1830–1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen Y, Gao J, Li L, et al.. The ciliary muscle and zonules of zinn modulate lens intracellular hydrostatic pressure through transient receptor potential vanilloid channels. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019; 60: 4416–4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kozono D, Yasui M, King LS, Agre P. Aquaporin water channels: atomic structure molecular dynamics meet clinical medicine. J Clin Invest. 2002; 109: 1395–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Varadaraj K, Kushmerick C, Baldo GJ, Bassnett S, Shiels A, Mathias RT. The role of MIP in lens fiber cell membrane transport. J Membrane Biol. 1999; 170: 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grey AC, Walker KL, Petrova RS, et al.. Verification and spatial localization of aquaporin-5 in the ocular lens. Exp Eye Res. 2013; 108: 94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruiz-Ederra J, Verkman AS.. Accelerated cataract formation and reduced lens epithelial water permeability in aquaporin-1-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 3960–3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Varadaraj K, Kumari SS, Mathias RT. Functional expression of aquaporins in embryonic, postnatal, and adult mouse lenses. Dev Dynamics. 2007; 236: 1319–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bok D, Dockstader J, Horwitz J. Immunocytochemical localization of the lens main intrinsic polypeptide (MIP26) in communicating junctions. J Cell Biol. 1982; 92: 213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang B, Verkman AS.. Water and glycerol permeabilities of aquaporins 1-5 and MIP determined quantitatively by expression of epitope-tagged constructs in Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997; 272: 16140–16146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ball LE, Little M, Nowak MW, Garland DL, Crouch RK, Schey KL. Water permeability of C-terminally truncated aquaporin 0 (AQP0 1-243) observed in the aging human lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44: 4820–4828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lo W-K, Harding CV.. Square arrays and their role in ridge formation in human lens fibers. J Ultrastructure Res. 1984; 86: 228–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zampighi GA, Hall JE, Ehring GR, Simon SA. The structural organization and protein composition of lens fiber junctions. J Cell Biol. 1989; 108: 2255–2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gonen T, Cheng Y, Sliz P, et al.. Lipid-protein interactions in double-layered two-dimensional AQP0 crystals. Nature. 2005; 438: 633–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rose KML, Gourdie RG, Prescott AR, Quinlan RA, Crouch RK, Schey KL. The C terminus of lens aquaporin 0 interacts with the cytoskeletal proteins filensin and CP49. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 1562–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang Z, Schey KL.. Aquaporin-0 interacts with the FERM domain of ezrin/radixin/moesin proteins in the ocular lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 5079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grey AC, Li L, Jacobs MD, Schey KL, Donaldson PJ. Differentiation-dependent modification and subcellular distribution of aquaporin-0 suggests multiple functional roles in the rat lens. Differentiation. 2009; 77: 70–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Petrova RS, Schey KL, Donaldson PJ, Grey AC. Spatial distributions of AQP5 and AQP0 in embryonic and postnatal mouse lens development. Exp Eye Res. 2015; 132: 124–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Woo J, Chae YK, Jang SJ, et al.. Membrane trafficking of AQP5 and cAMP dependent phosphorylation in bronchial epithelium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008; 366: 321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ishikawa Y, Eguchi T, Skowronski MT, Ishida H. Acetylcholine acts on M 3 muscarinic receptors and induces the translocation of aquaporin5 water channel via cytosolic Ca 2+ elevation in rat parotid glands. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998; 245: 835–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoffert JD, Leitch V, Agre P, King LS. Hypertonic induction of aquaporin-5 expression through an ERK-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000; 275: 9070–9077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moore M, Ma T, Yang B, Verkman A. Tear secretion by lacrimal glands in transgenic mice lacking water channels AQP1, AQP3, AQP4 and AQP5. Exp Eye Res. 2000; 70: 557–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Petrova RS, Webb KF, Vaghefi E, Walker K, Schey KL, Donaldson PJ. Dynamic functional contribution of the water channel AQP5 to the water permeability of peripheral lens fiber cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2018; 314: C191–C201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang W-H, Millar JC, Pang I-H, Wax MB, Clark AF. Noninvasive measurement of rodent intraocular pressure with a rebound tonometer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 4617–4621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bassnett S. A method for preserving and visualizing the three-dimensional structure of the mouse zonule. Exp Eye Res. 2019; 185: 107685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jacobs MD, Donaldson PJ, Cannell MB, Soeller C. Resolving morphology and antibody labeling over large distances in tissue sections. Microsc Res Techn. 2003; 62: 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Candia OA, Mathias R, Gerometta R. Fluid circulation determined in the isolated bovine lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 7087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vaghefi E, Pontre BP, Jacobs MD, Donaldson PJ. Visualizing ocular lens fluid dynamics using MRI: manipulation of steady state water content and water fluxes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011; 301: R335–R342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zampighi GA, Simon SA, Hall JE. The specialized junctions of the lens. Int Rev Cytol. 1992; 136: 185–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Al‐Ghoul KJ, Lindquist TP, Kirk SS, Donohue ST. A novel terminal web‐like structure in cortical lens fibers: architecture and functional assessment. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2010; 293: 1805–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Verkman AS, Ruiz-Ederra J, Levin MH. Functions of aquaporins in the eye. Prog Retinal Eye Res. 2008; 27: 420–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schey KL, Wang Z, Wenke JL, Qi Y. Aquaporins in the eye: expression, function, and roles in ocular disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014; 1840: 1513–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Donaldson PJ, Grey AC, Merriman-Smith BR, et al.. Functional imaging: new views on lens structure and function. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004; 31: 890–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Donaldson PJ, Lim J. Membrane transporters. In: Tombran-Tink J, Barnstable CJ, eds. Ocular Transporters in Ophthalmic Diseases and Drug Delivery. Totowa, NJ, United States: Springer; 2008: 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kumari SS, Varadaraj K. Aquaporin 5 knockout mouse lens develops hyperglycemic cataract. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013; 441: 333–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barandika O, Ezquerra-Inchausti M, Anasagasti A, et al.. Increased aquaporin 1 and 5 membrane expression in the lens epithelium of cataract patients. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016; 1862: 2015–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu X, Bandyopadhyay B, Nakamoto T, et al.. A role for AQP5 in activation of TRPV4 by hypotonicity concerted involvement of AQP5 and TRPV4 in regulation of cell volume recovery. J Biol Chem. 2006; 281: 15485–15495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Benfenati V, Caprini M, Dovizio M, et al.. An aquaporin-4/transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (AQP4/TRPV4) complex is essential for cell-volume control in astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011; 108: 2563–2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Taguchi D, Takeda T, Kakigi A, Takumida M, Nishioka R, Kitano H. Expressions of aquaporin‐2, vasopressin type 2 receptor, transient receptor potential channel vanilloid (TRPV) 1, and TRPV4 in the human endolymphatic sac. Laryngoscope. 2007; 117: 695–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nakazawa Y, Donaldson PJ, Petrova RS. Verification and spatial mapping of TRPV1 and TRPV4 expression in the embryonic and adult mouse lens. Exp Eye Res. 2019; 186: 107707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shahidullah M, Mandal A, Delamere NA. Activation of TRPV1 channels leads to stimulation of NKCC1 cotransport in the lens. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2018; 315: C793–C802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zampighi GA, Eskandari S, Kreman M. Epithelial organization of the mammalian lens. Exp Eye Res. 2000; 71: 415–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sandilands A, Prescott AR, Carter J, et al.. Vimentin and CP49/filensin form distinct networks in the lens which are independently modulated during lens fibre cell differentiation. J Cell Sci. 1995; 108: 1397–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Blankenship TN, Hess JF, FitzGerald PG. Development-and differentiation-dependent reorganization of intermediate filaments in fiber cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001; 42: 735–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. FitzGerald PG. Lens intermediate filaments. Exp Eye Res. 2009; 88: 165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Oka M, Kudo H, Sugama N, Asami Y, Takehana M. The function of filensin and phakinin in lens transparency. Mol Vis. 2008; 14: 815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xu L, Overbeek PA, Reneker LW. Systematic analysis of E-, N-and P-cadherin expression in mouse eye development. Exp Eye Res. 2002; 74: 753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]