Abstract

To examine the prospective associations between total cholesterol (TC) variability and cognitive function in a large sample of Chinese participants aged 45 years and above. A total of 6,377 people who participated in the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) were included. TC variability was defined as the intra-individual standard deviation over two blood tests in CHARLS 2011 and 2015 (Wave 1 and Wave 3). Cognitive function was assessed by a global cognition score, which included three tests: episodic memory, figure drawing and Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status (TICS). Multivariate linear regression models (MRLMs) and generalized estimating equation (GEE) were used to investigate associations between TC variability and cognitive scores. After adjusting for potential confounders, male participants with higher visit-to-visit TC variability showed lower global cognition scores (β = − 0.71, P < 0.001). After further adjustment for baseline cognition, the association remained statistically significant (β = − 0.68, P < 0.001). The domains with declines were focused on episodic memory (β = − 0.22, P = 0.026) and TICS (β = − 0.44, P = 0.004). However, these associations were not found in women (β = − 0.10, P = 0.623). For men, the rates of decline in global cognition increased by 0.14 (β = − 0.14, P = 0.009) units per year while TC variability increased by 1 mmol/L. For males, higher visit-to-visit TC variability correlated with lower cognitive function and an increased rate of decreases in memory. More attention should be paid to cognitive decline in males with high TC variability, and particularly, on decreases in memory, calculation, attention and orientation.

Subject terms: Alzheimer's disease, Cognitive ageing, Cognitive neuroscience, Risk factors

Introduction

Over 90 years ago, Walter Cannon coined the term “homeostatis”1, which hypothesized that the variability in constituents in the body is associated with abnormalities in human’s function. Under the guidance of this theory, recent studies have found that increased variability in lipid levels was related to high risk of mortality, atrial fibrillation, or myocardial infarction2–5. In recent years, patients at high cardiovascular risk receive intensive lipid-lowering therapy, leading to higher cholesterol variability. The effect of lipid-lowering therapy on neurocognitive function is disputable. Some evidence has indicated memory loss, while other studies have suggested beneficial outcomes. In contrast with TC concentration which was used most6–8, TC variability was a new and seldom studied marker. To date, a total of 3 studies have found that cholesterol variability was associated with dementia or cognitive function9–12. RAJ. Smit 2016 showed an association between high variability in low density lipoprotein (LDL) levels and low cognitive function. A. Solomon 2007 reported that changes in serum total cholesterol (TC) was associated with dementia, while HS. Hung 2019 linked high TC variability to high risk of dementia. Nevertheless, the longitudinal associations with cognitive function have yet to be examined. More importantly, there was no knowledge about the cholesterol variability associated with cognitive decline in China. Therefore, we used a national representative database, the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), to investigate cognitive function among people with high variability in cholesterol levels.

Materials and methods

Study sample

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) aimed to collect nationally representative sample of Chinese residents. The Wave 1 of CHARLS included about 17,000 individuals from 150 counties/districts and 450 villages/resident committees. The subjects of the study were Chinese citizens aged 45 years and above13. Baseline data (Wave 1) were collected between June 2011 and March 2012. In addition, the survey was conducted and followed up every 2 years.

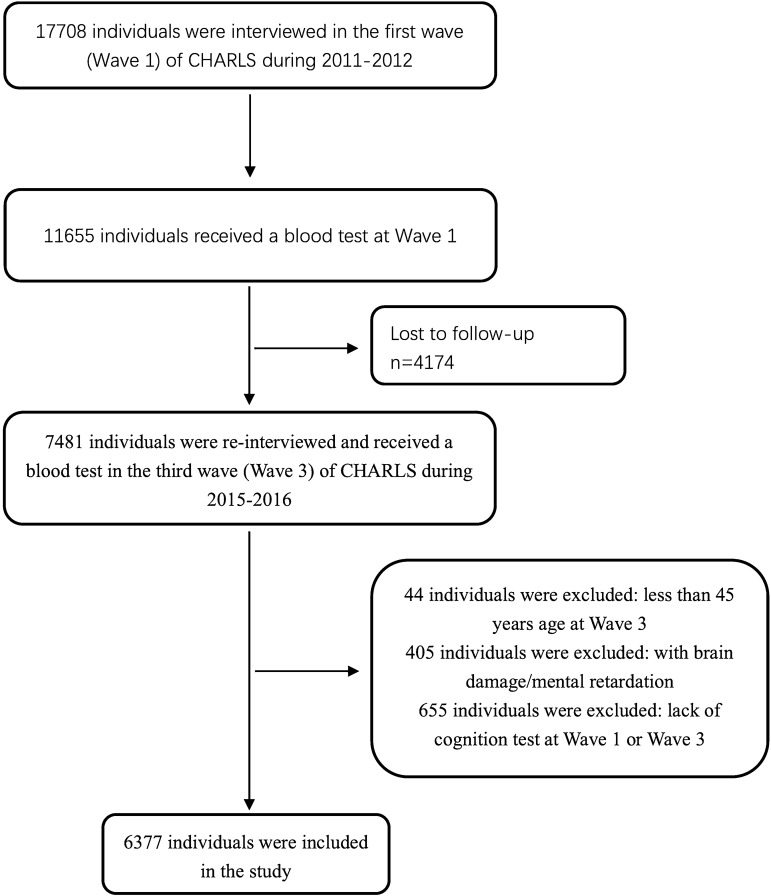

In the CHARLS, a total number of 7,481 participants received blood testing twice, in 2011 (Wave 1) and 2015 (Wave 3). Of the 7,481 individuals, 44 individuals under 45 years old were excluded, 405 individuals with a history of brain damage or mental retardation were excluded, and 655 individuals without the cognitive tests were excluded. Eventually, 6,377 individuals were included in this study. The selection diagram and criteria for exclusion were provided in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the sample selection and exclusion criteria.

Assessment of cognition

Cognitive function was evaluated through three kinds of tests: episodic memory, figure drawing, and Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status (TICS). Serving as the primary outcome, the global cognition score was the sum of the three test scores. The global cognition score ranges from 0 to 21. The average score of all participants was about 10. The cognitive function was tested in Wave 1 and Wave 3, by face-to-face interview. Cognitive function in Wave 3 was used as the outcome.

The episodic memory test reflected individuals’ function of memory. In the test, the participants were asked to memorize and recall the words immediately (immediate recall) and 5 min later (delayed recall) after interviewers read 10 Chinese nouns to them14. The episodic memory score was the average score of the immediate recall and delayed recall tests and could range from 0 to 10. The figure drawing test examined the visuospatial function. In the figure-drawing test, the participants were shown a picture and asked to redraw it. If the participant failed, the figure-drawing score was 0, and if the participant succeeded, the score was 1. The TICS test reflected function of attention, calculation and attention. This test was based on selected questions from the TICS battery in mini-mental state examination (MMSE), and was reliable for research on cognition15,16. In this test, the participants were asked to repeatedly subtract 7 from 100 and to identify the date, season, and day of the week. The TICS scores could range from 0 to 10.

Assessment of TC variability

Blood samples of all the participants were collected after an overnight fast by trained staff in the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Chinese CDC). Venous blood was turned into plasma and buffy coat and was immediately frozen and stored at − 20 °C; the samples were transported to the Chinese CDC in Beijing within 2 weeks, where they were placed in a deep freezer and stored at − 80 °C until quantified at Capital Medical University (CMU) laboratory13. In the statistical analyses, we converted the units from mg/dL to mmol/L.

The CHARLS had three waves, however, the blood testing was only carried out twice, in Wave 1 and Wave 3. The visit-to-visit variability in TC (TC variability) was calculated by intra-individual standard deviations (SDs) across the two tests10.

Because the level of most people’s TC variability was small, and there were no guidelines for abnormal levels of variability, we chose the SD as cut-off points for a simple and clear categorization12. Based on the SD in the TC variability, we divided men into 4 groups: ≤ 0.306 mmol/L, 0.306–0.612 mmol/L, 0.612–0.918 mmol/L, > 0.918 mmol/L as Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4, respectively. In addition, women were grouped as Q1 (≤ 0.278 mmol/L), Q2 (0.278–0.556 mmol/L), Q3 (0.556–0.834 mmol/L) and Q4 (> 0.834 mmol/L).

Potential confounders

Because of socioeconomic status, elderly Chinese females have a lower cognitive function than men17. Some studies have reported the gender differences when taking dementia as the outcome18. Thus, we conducted our research on men and women separately.

The potential confounders consisted of health factors and diseases recorded in CHARLS Wave 1. They are all known to be associated with blood cholesterol concentration and cognitive function. The average of TC levels in Wave 1 and Wave 3 was adjusted in all models. In Tables 3 and 4, Model 1 was the minimally adjusted model. It included age, education, marital status, residential area, mean TC concentration, and BMI. Model 2 was the fully adjusted model. It further included smoking, drinking, depression, lipid-lowering therapy, and six comorbidities.

Table 3.

Associations between TC variability and cognitive function (dependent variable) in Wave 3.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P value | β (95% CI) | P value | |

| Male | ||||

| Global cognition | − 0.71 (− 0.92, − 0.50) | < 0.001 | − 0.71 (− 0.92, − 0.50) | < 0.001 |

| Episodic memory | − 0.22 (− 0.32, − 0.12) | 0.023 | − 0.22 (− 0.31, − 0.12) | 0.026 |

| Figure drawing | − 0.05 (− 0.08 to − 0.03) | 0.053 | − 0.05 (− 0.08 to − 0.02) | 0.054 |

| TICS | − 0.43 (− 0.59, − 0.29) | 0.004 | − 0.44 (− 0.59, − 0.29) | 0.004 |

| Female | ||||

| Global cognition | − 0.07 (− 0.29, 0.15) | 0.750 | − 0.10 (− 0.32, 0.11) | 0.623 |

| Episodic memory | − 0.00 (− 0.10, 0.10) | 0.982 | 0.01 (− 0.09, 0.11) | 0.903 |

| Figure drawing | 0.01 (− 0.03, 0.02) | 0.816 | 0.01 (− 0.02, 0.03) | 0.800 |

| TICS | − 0.07 (− 0.23 to 0.08) | 0.639 | − 0.13 (− 0.28, 0.03) | 0.423 |

Model 1: adjusted for age, education, mean TC, marital status, residential area, and BMI.

Model 2: adjusted for Model 1 + smoking, drinking, depression, lipid-lowering therapy, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, stroke, heart disease, and cancer.

Using multiple linear regression model, the adjusted unstandardized regression coefficients and P values were calculated with TC variability (mmol/L) used as a continuous measurement.

Table 4.

Associations between TC variability and cognitive function in Wave 3 after adjusting for baseline cognition.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P value | β (95% CI) | P value | |

| Male | ||||

| Global cognition | − 0.67 (− 0.86, − 0.48) | < 0.001 | − 0.68 (− 0.87, − 0.49) | < 0.001 |

| Episodic memory | − 0.23 (− 0.33, − 0.14) | 0.012 | − 0.23 (− 0.32, − 0.14) | 0.014 |

| Figure drawing | − 0.05 (− 0.08 to -0.02) | 0.067 | − 0.05 (− 0.08, − 0.03) | 0.064 |

| TICS | − 0.39 (− 0.53, − 0.25) | 0.005 | − 0.44 (− 0.59, − 0.29) | 0.003 |

| Female | ||||

| Global cognition | − 0.10 (− 0.31, 0.08) | 0.571 | − 0.13 (− 0.33, 0.05) | 0.476 |

| Episodic memory | − 0.01 (0.10, 0.08) | 0.903 | 0.00 (− 0.10, 0.09) | 0.963 |

| Figure drawing | 0.01 (− 0.01 to 0.03) | 0.719 | 0.01 (− 0.02, 0,04) | 0.724 |

| TICS | − 0.10 (− 0.24 to 0.04) | 0.465 | − 0.14 (− 0.31, − 0.03) | 0.298 |

Model 1: adjusted for baseline cognition, age, mean TC, education, marital status, residential area, and BMI.

Model 2: adjusted for Model 1 + smoking, drinking, depression, lipid-lowering therapy, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, stroke, heart disease, and cancer.

Using multiple linear regression model, the adjusted unstandardized regression coefficients and P values were calculated with TC variability (mmol/L) used as a continuous measure.

We analysed the effect of drugs on cognitive function by using “lipid-lowering therapy” as a categorical variable (yes or no). Depression was classified as “yes” and “no”, using the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale (CES-D-10). This score can range from 0 to 30, and the cut-off point for depression was 1219. The comorbidities included hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes, cancer or tumour, heart problems and stroke, which were assessed in Wave 1.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics were presented as the mean ± SD or frequency (percentage). Associations between participants’ characteristics and TC variability were examined using ANOVA or the Pearson χ2 test. The linear correlations between TC variability and cognitive function in Wave 3 were calculated using multivariate linear regression models (MRLMs) after adjustment for potential confounders. In Table 2, TC variability was defined as a categorical variable. Individual in Q1 group had the highest mean global cognition score. We compared Q2, Q3, Q4 with Q1 separately. We also used generalized estimating equation (GEE) to extend the linear model for further analysis of the longitudinal associations. In GEE, the interaction of the time variable with TC variability was conducted to examine whether rates of cognitive decline varied by levels of TC variability. All data were analysed by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA), and P < 0.05 was defined as the significance level.

Table 2.

Mean cognition scores in the four categories of TC variability in Wave 3.

| Sex | TC variability | N | Global cognition | Episodic memory | Figure drawing | TICS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X ± s | P value | X ± s | P value | X ± s | P value | X ± s | P value | |||

| Male | Q1 (≤ 0.306 mmol/L) | 1703 | 11.14 ± 3.91 | Ref | 3.32 ± 1.81 | Ref | 0.71 ± 0.45 | Ref | 7.11 ± 2.60 | Ref |

| Q2 (0.306–0,612 mmol/L) | 829 | 11.05 ± 3.84 | 0.409 | 3.30 ± 1.76 | 0.682 | 0.71 ± 0.45 | 0.683 | 7.04 ± 2.60 | 0.472 | |

| Q3 (0.612–0.918 mmol/L) | 243 | 10.69 ± 4.10 | 0.009 | 3.26 ± 1.72 | 0.250 | 0.66 ± 0.47 | 0.058 | 6.77 ± 2.78 | 0.006 | |

| Q4 (> 0.918 mmol/L) | 122 | 10.88 ± 3.96 | 0.155 | 3.20 ± 1.64 | 0.111 | 0.66 ± 0.47 | 0.210 | 7.02 ± 2.70 | 0.189 | |

| Female | Q1 (≤ 0.278 mmol/L) | 1899 | 9.59 ± 4.46 | Ref | 3.30 ± 1.86 | Ref | 0.54 ± 0.50 | Ref | 5.76 ± 2.97 | Ref |

| Q2 (0.278–0.556 mmol/L) | 1,040 | 9.52 ± 4.57 | 0.728 | 3.27 ± 1.90 | 0.790 | 0.51 ± 0.50 | 0.078 | 5.75 ± 3.02 | 0.766 | |

| Q3 (0.556–0.834 mmol/L) | 361 | 8.93 ± 4.53 | 0.542 | 3.06 ± 1.84 | 0.655 | 0.48 ± 0.50 | 0.844 | 5.40 ± 3.09 | 0.591 | |

| Q4 (> 0.834 mmol/L) | 185 | 9.12 ± 4.93 | 0.427 | 3.13 ± 1.98 | 0.697 | 0.54 ± 0.50 | 0.281 | 5.45 ± 3.19 | 0.413 | |

Adjusted for age, education, mean TC, marital status, residential area, BMI, smoking, drinking, depression, lipid-lowering therapy, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, stroke, heart disease, and cancer.

Ethics statement

Each participant included in this study signed a written informed consent form before taking the survey. Ethics approval for the data collection in the CHARLS was obtained from the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015). We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Demographic and health characteristics of the study population in Wave 1 among the different TC groups

The mean ± SD of TC variability among all people was 0.32 ± 0.29 mmol/L. At baseline, the mean age of the participants was 58.4 ± 8.7 years; 45.4% of the participants were male; 74% of them finished their education in primary school; and 79.7% of the participants were from rural areas.

Higher TC variability was associated with higher mean TC concentrations (P < 0.001). Among all the participants, more than 5% were receiving lipid-lowering therapy for dyslipidaemia. In addition, in the groups with higher TC variability, more individuals were receiving therapy (P < 0.001). Participants with higher TC variability tended to live in urban area (P = 0.004) and drink (P = 0.014). The subjects with higher TC variability were more likely to have depression (P = 0.015), hypertension (P < 0.001) and dyslipidaemia (P = 0.025). We found no associations between TC variability and age, gender, education, marital status, BMI, smoking, and history of diabetes mellitus, heart disease and stroke (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and health characteristics of the study population in Wave 1 among the different TC groups.

| Q1 (n = 3,607) | Q2 (n = 1,850) | Q3 (n = 605) |

Q4 (n = 315) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables | |||||

| Age, years | 58.4 ± 8.9 | 58.3 ± 8.6 | 58.8 ± 8.5 | 58.8 ± 8.2 | 0.418 |

| Mean TCa, mmol/L | 4.8 ± 0.8 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 5.1 ± 0.9 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| Categorical variables, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 1647 (45.7) | 829 (44.8) | 266 (44.0) | 150 (47.8) | 0.664 |

| Education | 0.579 | ||||

| Illiterate | 905 (25.1) | 494 (26.7) | 173 (28.6) | 91 (28.9) | |

| Primary school | 1562 (43.3) | 789 (42.3) | 258 (42.7) | 135 (42.9) | |

| Middle school | 771 (21.4) | 383 (21.2) | 113 (18.7) | 60 (19.1) | |

| High school and above | 368 (10.2) | 174 (9.4) | 60 (9.9) | 29 (9.2) | |

| Marital status | 0.743 | ||||

| Married | 3,244 (89.9) | 1671 (90.3) | 550 (90.9) | 281 (91.1) | |

| Other status | 363 (10.1) | 179 (9.7) | 55 (9.1) | 38 (8.9) | |

| Residential area | 0.004 | ||||

| Urban | 612 (16.6) | 299 (15.8) | 88 (13.5) | 75 (23.0) | |

| Rural | 3,076 (83.4) | 1,590 (84.2) | 537 (85.9) | 251 (77.0) | |

| Depression | 0.015 | ||||

| Yes | 264 (7.1) | 108 (5.7) | 58 (9.3) | 26 (8.0) | |

| No | 3,431 (92.9) | 1784 (94.3) | 567 (90.7) | 300 (92.0) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.115 | ||||

| < 18.5 | 561 (15.2) | 264 (14.0) | 87 (13.4) | 50 (15.3) | |

| 18.5–28 | 2,742 (74.2) | 1,392 (736.) | 464 (74.2) | 227 (69.6) | |

| > 28 | 392 (10.6) | 236 (12.5) | 74 (11.8) | 49 (15.0) | |

| Current smoker | 1,408 (38.1) | 734 (38.8) | 229 (36.6) | 136 (41.7) | 0.460 |

| Current drinker | 873 (23.6) | 501 (26.5) | 166 (26.6) | 97 (29.8) | 0.014 |

| Hypertension | 872 (23.6) | 474 (25.1) | 192 (30.7) | 105 (42.2) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 346 (9.4) | 177 (9.4) | 76 (12.2) | 43 (13.2) | 0.025 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 192 (5.2) | 115 (6.1) | 49 (7.8) | 18 (5.5) | 0.056 |

| History of heart disease | 423 (11.5) | 236 (12.5) | 82 (13.1) | 45 (13.8) | 0.361 |

| History of stroke | 69 (1.9) | 32 (1.7) | 12 (1.9) | 9 (2.8) | 0.626 |

| Lipid-lowering therapy | 216 (5.9) | 139 (7.4) | 70 (11.2) | 52 (15.9) | < 0.001 |

Four groups were categorized by the SD in TC variability (SD = 0.306 mmol/L): Q1: ≤ 0.306 mmol/L, Q2: 0.306–0,612 mmol/L, Q3: 0.612–0.918 mmol/L, Q4: > 0.918 mmol/L.

Mean cognition scores in the four categories of TC variability in Wave 3

We divided all individuals by gender, into 4 groups (Q1 to Q4) using the same method shown in Table 1. The participants with higher TC variability had lower cognitive function. After defining the dummy variables for the TC variability, P values for each dummy variable were calculated with a linear regression model after adjusting for age. In men, although the mean cognition scores decreased in each group, only the third group showed significance (P < 0.05). In addition, in women, there were no associations in these groups (Table 2).

Associations between TC variability and cognitive function (dependent variable) in Wave 3

For males, higher TC variability was significantly associated with lower global cognition scores in Wave 3 (P < 0.001 for both model 1 and model 2). The domains showing decreased scores were episodic memory (P = 0.023 for model 1 and P = 0.026 for model 2) and TICS (P = 0.004 for both model 1 and model 2). There was no association in the figure drawing test (P = 0.053 for model 1 and P = 0.054 for model 2). For females, we found no evidence for an association between TC variability and cognition scores (Table 3).

Associations between TC variability and cognitive function in Wave 3 after adjusting for baseline cognition

These associations were essentially unchanged in the model that added baseline (Wave 1) cognition as a covariate. For males, high TC variability was significantly associated with lower global cognition scores (P < 0.001 for both model 1 and model 2). The domains showing decreased score were episodic memory (P = 0.012 for model 1 and P = 0.014 for model 2) and TICS (P = 0.005 for model 1 and P = 0.003 for model 2). This association was not seen in the figure drawing test (P = 0.067 for model 1 and P = 0.064 model 2). For females, we found no evidence for associations between TC variability and cognition scores (Table 4).

Longitudinal cognitive changes by TC variability using GEE model*

Among males, the TC variability-by-time interaction was statistically significant (β = -0.14, P = 0.009). As TC variability increased 1 mmol/L in males, the decline rate in global cognition increased 0.14 units (global cognition score) per year (Table 5). The specific domain was episodic memory (β = − 0.06, P = 0.031). Figure drawing and TICS were not significant.

Table 5.

Longitudinal cognitive changes by TC variability using GEE model.

| Cognition test | Intercept β (95% CI) |

P value | Time β (95% CI) |

P value | TC variability × time β (95% CI) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | ||||||

| Global cognition | 10.34 (9.76, 10.92) | < 0.001 | − 0.03 (− 0.06, − 0.01) | 0.174 | − 0.14 (− 0.19, − 0.09) | 0.009 |

| Episodic memory | 4.50 (4.23, 4.77) | < 0.001 | 0.04 (0.02, 0.05) | 0.007 | − 0.06 (− 0.08, − 0.04) | 0.031 |

| Figure drawing | 0.62 (0.56, 0.69) | < 0.001 | − 0.01(− 0.01, 0.00) | 0.044 | − 0.02 (− 0.02, 0.00) | 0.238 |

| TICS | 5.22 (4.82, 5.62) | < 0.001 | − 0.06 (− 0.08, − 0.05) | < 0.001 | − 0.07 (− 0.11, − 0.03) | 0.081 |

Adjusted for all potential confounders.

Discussion

We examined the longitudinal relationship between visit-to-visit total cholesterol (TC) variability and cognitive function among 6,377 middle-aged and elderly Chinese participants. It was identified that higher TC variability was associated with lower global cognition scores and higher rates of decline in global cognition scores over a period of 4 years in men, even after adjustments for mean TC variability at baseline and other potential confounders. For cognitive scores in Wave 3, the main affected domains were episodic memory and TICS. For rates of cognitive decline, the main affected domain was episodic memory. However, we found no associations in women.

Our results were similar to those from a previous study10, which reported that participants with high cholesterol variability had lower cognitive function. Nevertheless, our study had three differences. First, using MRLMs and GEE, we examined the longitudinal relationship that higher TC variability was associated with faster rates of decline over a period of 4 years. Second, we found this association did not exist in women. Third, we provided additional evidence for previous findings that the cognitive degeneration domains were episodic memory and TICS which represented abilities in memory, calculation and orientation. Individuals’ visuospatial ability, reflected by “figure drawing”, also declined but was not significant. Last but not least, in the past 3 years, some studies have reported other effects of TC variability or LDL variability2–5. Together with our study, there are indications that cholesterol variability could be a target for further research.

The association was not significant between LDL variability and cognition in our study, although the relationship was also negative (Supplementary Material 3). In serum, TC is mainly composed of LDL. LDL is sometimes called “bad” cholesterol, for it moves cholesterol around the blood and deposits it on the artery walls20. Therefore, compared with TC, LDL is viewed as a more “precise” target in the treatment of atherosclerosis cardiovascular disease21. In many studies which learned cholesterol, if TC made significance, LDL would make significance. However, we did not find LDL variability was associated with lower cognition. One previous study also reported, variability in TC, instead of LDL, was associated with lower cognition9. Limited by current studies, we could not explain this phenomenon.

There are several explanations for our findings. Both animal22 and clinical23 studies have demonstrated that lipid-lowering therapy could reconstruct carotid atherosclerotic plaques and make the plaques unstable. Thus, cholesterol variability might break the plaque into tiny pieces, thereby increasing the risk of subclinical cerebrovascular damage24,25. Furthermore, studies have reported that high LDL variability was associated with lower cerebral blood flow and endothelial dysfunction, which are linked to poor cognition26,27.

Whether lipid-lowering treatment affects cognition remains unclear28–32. Due to the sample size and cross-sectional nature of this study, we could not find strong evidence that lipid-lowering treatment led to cognitive change (Supplementary Material 1). In our study, receiving lipid-lowering therapy might be the result of dyslipidaemia and vascular diseases, which have been associated with lower cognition. Nevertheless, our findings highlight the need for concern about TC variability among people receiving lipid-lowering treatment. Currently, an expanding extent of lipid-lowering treatment has been recommended by doctors to prevent people at high risk from cardiovascular disease. A meta-analysis showed more intensive lipid-lowering therapy could reduce cardiovascular mortality33. In China, the proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 (PCSK9) monoclonal antibodies have been in clinical use since 2019, which are known to produce high TC variability34. On the basis of our results, it is imperative to monitor the cognitive consequences in patients receiving active lipid-lowering therapies.

The advantages of our study were its large number of subjects from a prospective study, and conclusions based on longitudinal design. However, our study had several limitations. First, in our study, TC variability was calculated from the result of two blood tests (Wave 1 and Wave 3), while other studies had a larger number of blood tests ranging from 2 to 4. Second, 655 of 7,481 (8.76%) participants were excluded for the lack of cognition test results. The exclusion might have influenced the results. Third, the cognitive tests were limited. It could examine the major part of cognition. Considering that it was not a standardized test, there was no robust cut-off point for diagnosis of dementia, mild cognitive impairment, or significant cognitive decline.

The gender difference may be our new discovery. One previous study had not separated men and women, and viewed gender as a categorical variable when using MRLMs10. If we defined gender as a categorical confounder, we would have reached a similar conclusion: TC variability was significantly associated with cognition in Wave 3 through MRLMs (Supplementary Material 2). However, Tables 3 and 4 showed that the association did not exist in females.

There are some possible mechanisms to explain the gender difference. First, a previous study reported that decreases in serum TC increased the risk (OR 2.3) of dementia after approximately 20 years12. As the mean TC level in women was 0.3 mmol/L higher than that in men in our study (Supplementary Material 4), we hypothesized that the high TC levels protected women from the negative effects. Second, women had lower cognitive function than men. One previous study17, learning cognitive difference in CHARLS, attributed the cognitive difference to schooling, family and community levels of economic resource. Women might be tolerant to the impact of TC variability through unknown process.

Conclusion

For men, individuals with higher visit-to-visit TC variability had lower cognitive function and suffered from a faster cognitive decline over a period of 4 years. The main domains showing decreases were memory, calculation, attention and orientation. The associations were not shown in women and need further research.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We appreciated the China Center for Economic Research, the National School of Development of Peking University for providing the data.

Author contributions

J.H. contributed conception and design of the study. Y.S. organized the database. J.H., C.K. and Y.Q. performed the statistical analysis. J.H. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Y.S. and C.K. reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (project number 81973143) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Data availability

The data used in this manuscript from the China Health and retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). We applied the permission for the data access (https://charls.pku.edu.cn/zh-CN) and got the access to use it. Prof. Yaohui Zhao (National School of Development of Peking University), John Strauss (University of Southern California), and Gonghuan Yang (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention) are the principle investigators.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jianian Hua and Yanan Qiao.

Contributor Information

Chaofu Ke, Email: cfke@suda.edu.cn.

Yueping Shen, Email: shenyueping@suda.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-72601-7.

References

- 1.Cannon WB. Organization for physiological homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 1929;9:399–431. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1929.9.3.399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark D, 3rd, et al. Visit-to-visit cholesterol variability correlates with coronary atheroma progression and clinical outcomes. Eur. Heart. J. 2018;39:2551–2558. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim MK, et al. Cholesterol variability and the risk of mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke: A nationwide population-based study. Eur. Heart J. 2017;38:3560–3566. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin YH, et al. Greater low-density lipoprotein cholesterol variability is associated with increased progression to dialysis in patients with chronic kidney disease stage 3. Oncotarget. 2018;9:3242–3253. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roh E, et al. Total cholesterol variability and risk of atrial fibrillation: A nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0215687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reitz C, Tang MX, Luchsinger J, Mayeux R. Relation of plasma lipids to Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2004;61:705–714. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernando RL, et al. Controlling the proportion of false positives in multiple dependent tests. Genetics. 2004;166:611–619. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.1.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kivipelto M, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele, elevated midlife total cholesterol level, and high midlife systolic blood pressure are independent risk factors for late-life Alzheimer disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002;137:149–155. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-3-200208060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SH, et al. Variability in metabolic parameters and risk of dementia: A nationwide population-based study. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2018;10:110. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0442-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smit RAJ, et al. Higher visit-to-visit low-density lipoprotein cholesterol variability is associated with lower cognitive performance, lower cerebral blood flow, and greater white matter hyperintensity load in older subjects. Circulation. 2016;134:212. doi: 10.1161/Circulationaha.115.020627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung HS, et al. Variability in total cholesterol concentration is associated with the risk of dementia: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Front. Neurol. 2019;10:2. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomon A, et al. Serum cholesterol changes after midlife and late-life cognition: Twenty-one-year follow-up study. Neurology. 2007;68:751–756. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256368.57375.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014;43:61–68. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McArdle JJ, Ferrer-Caja E, Hamagami F, Woodcock RW. Comparative longitudinal structural analyses of the growth and decline of multiple intellectual abilities over the life span. Dev. Psychol. 2002;38:115–142. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin T, et al. Association between anemia and cognitive decline among Chinese middle-aged and elderly: Evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:305. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng Q, et al. Validation of neuropsychological tests for the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019;31:1709–1719. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei X, Hu Y, McArdle JJ, Smith JP, Zhao Y. Gender differences in cognition among older adults in China. J. Hum. Resour. 2012;47:951–971. doi: 10.3368/jhr.47.4.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ancelin ML, et al. Sex differences in the associations between lipid levels and incident dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34:519–528. doi: 10.3233/Jad-121228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng ST, Chan AC. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in older Chinese: Thresholds for long and short forms. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2005;20:465–470. doi: 10.1002/gps.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hevonoja T, Pentikainen MO, Hyvonen MT, Kovanen PT, Ala-Korpela M. Structure of low density lipoprotein (LDL) particles: Basis for understanding molecular changes in modified LDL. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1488:189–210. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mach F, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 2020;41:111–188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bjorkegren JLM, et al. Plasma cholesterol-induced lesion networks activated before regression of early, mature, and advanced atherosclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crisby M, et al. Pravastatin treatment increases collagen content and decreases lipid content, inflammation, metalloproteinases, and cell death in human carotid plaques: Implications for plaque stabilization. Circulation. 2001;103:926–933. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z, et al. Cholesterol in human atherosclerotic plaque is a marker for underlying disease state and plaque vulnerability. Lipids Health Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1476-511x-9-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quinn TJ, et al. Association between circulating hemostatic measures and dementia or cognitive impairment: Systematic review and meta-analyzes. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011;9:1475–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de la Torre JC. Is Alzheimer's disease a neurodegenerative or a vascular disorder? Data, dogma, and dialectics. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:184–190. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davignon J, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109:27–32. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131515.03336.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane RM, Farlow MR. Lipid homeostasis and apolipoprotein E in the development and progression of Alzheimer's disease. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:949–968. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400486-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hottman DA, Chernick D, Cheng S, Wang Z, Li L. HDL and cognition in neurodegenerative disorders. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014;72(Pt A):22–36. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Appleton JP, Scutt P, Sprigg N, Bath PM. Hypercholesterolaemia and vascular dementia. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2017;131:1561–1578. doi: 10.1042/cs20160382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banach M, et al. Intensive LDL-cholesterol lowering therapy and neurocognitive function. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017;170:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olsson AG, et al. Can LDL cholesterol be too low? Possible risks of extremely low levels. J. Intern. Med. 2017;281:534–553. doi: 10.1111/joim.12614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navarese EP, et al. Association between baseline LDL-C level and total and cardiovascular mortality after LDL-C lowering: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319:1566–1579. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ballantyne CM, et al. Results of bococizumab, a monoclonal antibody against proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, from a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study in statin-treated subjects with hypercholesterolemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015;115:1212–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this manuscript from the China Health and retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). We applied the permission for the data access (https://charls.pku.edu.cn/zh-CN) and got the access to use it. Prof. Yaohui Zhao (National School of Development of Peking University), John Strauss (University of Southern California), and Gonghuan Yang (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention) are the principle investigators.