Abstract

The rising prevalence of multidrug-resistant hospital-acquired infections has increased the need for new antibacterial agents. In this study, a library of 1586 FDA-approved drugs was screened against A. calcoaceticus, a representative of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–baumannii complex. Three compounds were found to have previously undiscovered antibacterial properties against A. calcoaceticus: antifungal Miconazole, anthelminthic Dichlorophen, and Bithionol. These three drugs were tested against a wide range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and confirmed to have broad-spectrum antibacterial properties. Combinations of these three drugs were also tested against the same bacteria, and two novel combination therapies with synergistic effects were discovered. In the future, antibacterial properties of these three drugs and two combination therapies will be evaluated against pathogenic bacteria using an animal model.

Introduction

In recent years, infectious diseases have accounted for about 17% of deaths worldwide.1 Since the discovery of penicillin in 1928, antibiotic development and clinical use against infectious agents have grown into a $40 billion industry in the United States.2 However, the widespread clinical use of microbials has placed selective pressure on pathogens with resistance to multiple antibiotics. Rates of resistance have nearly doubled since 2002, with the CDC estimating that antibiotic-resistant pathogens account for 2 million infections and 23,000 deaths annually in the U.S.3 The rising levels of drug resistance pose serious threats to human health and present extensive therapeutic challenges, as the spread of antibiotic resistance may soon outpace the development of new antimicrobials.

Clinical practice has been complicated by a group of frequently multidrug-resistant organisms termed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America as ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species).4 Of these, the 2017 World Health Organization Priority Pathogens List ranks A. baumannii highest as critical priority and urgently needing new treatments.5

A. baumannii is an opportunistic Gram-negative coccobacillus responsible for 2–10% of all Gram-negative hospital-acquired infections, causing topical and systemic conditions such as ventilator-associated pneumonia, skin and soft tissue infections, and bacteremia.6,7A. calcoaceticus is a related strain with a mean genetic divergence of 9.66% from A. baumannii.(8) Due to their genetic and phenotypic similarities, A. calcoaceticus, A. baumannii, A. pittii, and A. nosocomialis are often collectively termed the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–baumannii complex (ACB).9 The resistance of nosocomial Acinetobacter spp. to desiccation allows survival in both dry and humid conditions and naturally facilitates fomite transmission in a medical environment, with common reservoirs including the hands of healthcare personnel and reusable medical devices like ventilator equipment.10,11

First line therapeutic options for ACB infections include broad-spectrum cephalosporins, carbapenems, and fluoroquinolones.12,13 However, the growing emergence of multidrug resistance (MDR) in Acinetobacter species threatens the usefulness of our current antibiotic measures.9Acinetobacter species have a number of antimicrobial resistance mechanisms, such as an intrinsic BfmRS signal transduction system that enhances virulence and bactericidal resistance at the transcriptome level by allowing rapid genetic reprogramming.14 Through additional acquisitions of beta-lactamases, alterations in outer membrane porin proteins, and overexpression of efflux pumps, drug-resistant Acinetobacter strains have rendered conventional antibiotic therapies ineffective and highlight the urgent need for alternatives with more robust elimination of ACB infection.7,15−17

Traditional identification of new antibiotics through cell culture screens presents significant time and resource limitations, especially against Gram-negative bacteria. A viable alternative that circumvents such financial and temporal challenges is the repurposing of existing FDA-approved drugs into antibiotics.18 In line with this goal, our study aims to identify pre-existing drugs that can be repurposed against ACB infections.

A total of 1586 well-characterized approved drugs from the commercially available Johns Hopkins Clinical Compound Library (JHCCL) were screened against A. calcoaceticus, and Miconazole and Dichlorophen were isolated as hits. The identification of these drugs against A. calcoaceticus provides us with vital insights into alternative treatments for ACB infections and validates drug screening as a productive approach against drug-resistant species.

Results and Discussion

Drug Screening against A. calcoaceticus

Fifteen non-antibiotic drugs from the JHCCL drug library were identified in our screen after producing notable zones of inhibition relative to that of the antibiotics. Confirmatory retests of each drug were conducted separately using the antibiotic Doxycycline as a positive control. The fifteen drug candidates were narrowed to two based on their reproducibility in inhibiting the bacteria: Miconazole and Dichlorophen (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Drug screening against A. calcoaceticus. Zones of inhibition of A. calcoaceticus growth by 1 μL of 3.3 mM Miconazole, Dichlorophen, Doxycycline (positive control, halo circled with the dotted line for reference), and DMSO (negative control) on lawns of 75 μL of A. calcoaceticus culture incubated overnight at 37 °C. Normalized fold changes of the halos are shown at the bottom right corner of the images.

In noting the bactericidal effects for Dichlorophen, it was hypothesized that its clinically used analogues, Bithionol and Triclosan, could also be effective due to their structural similarity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Chemical structures and indications of the four drugs assessed for anti-Acinetobacter calcoaceticus activity.

Although an anthelmintic, Bithionol has a reported bacteriostatic activity while Triclosan is a well-known antibacterial agent and thus served as a positive control.19,20 After testing, both drugs were found effective against A. calcoaceticus, producing zones of inhibition larger than that of DMSO (Figure 3).

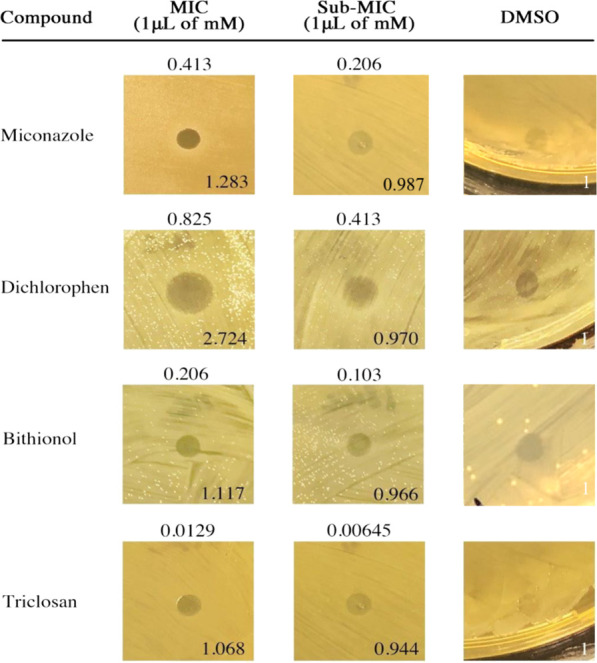

Figure 3.

Diffusion susceptibility test on A. calcoaceticus. Representative zones of inhibition of A. calcoaceticus growth by 1 μL of MIC and sub-MIC of Miconazole, Dichlorophen, Bithionol, and Triclosan. DMSO serves as the negative control. MIC and sub-MIC values are indicated above corresponding halo images. Normalized fold changes of the halos are shown at the bottom right corner of the images.

Solid Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Drug Hits

Diffusion susceptibility tests of Miconazole, Dichlorophen, Bithionol, and Triclosan were run on solid BHI agar to determine their potency as topical medications against A. calcoaceticus. The efficacy of each drug was evaluated by quantitatively assessing the MIC at which the drug formed a zone of inhibition greater than that of DMSO (Figure 3). As expected, Triclosan had the lowest MIC at 1 μL of 0.0129 mM. Miconazole, Bithionol, and Dichlorophen had MICs ranging from 1 μL of 0.825 mM to 0.206 mM.

Liquid Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Drug Hits

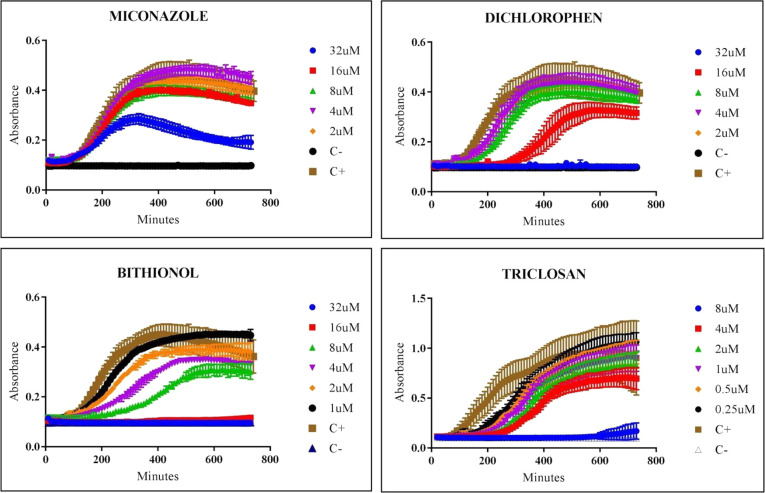

Because ACB infections can manifest systemically, we investigated the efficacy of our hits against A. calcoaceticus in BHI liquid media. The growth curves of A. calcoaceticus in the presence of varying concentrations of Miconazole, Dichlorophen, Bithionol, and Triclosan are shown in Figure 4. MICs were determined as the drug concentration that delays, with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05), the time needed to reach the mid-log OD600 of the positive control. These concentrations were 16 ± 12, 8 ± 6, 2 ± 1, and 0.5 ± 0.3 μM, respectively.

Figure 4.

Kinetic growth of A. calcoaceticus with varying concentrations of hits. Antimicrobial activity of Miconazole, Dichlorophen, Bithionol, and Triclosan at concentrations ranging from 32 to 1 μM on A. calcoaceticus growth.

Bithionol and Triclosan tested similarly between solid and liquid media. Although Miconazole had a greater MIC in liquid than in solid media, Dichlorophen demonstrated a decreased MIC in the liquid assay compared to the solid diffusion susceptibility tests. As expected from an antibacterial agent, Triclosan had the most robust activity, or lowest MIC, amongst the other drugs in both solid and liquid assays.

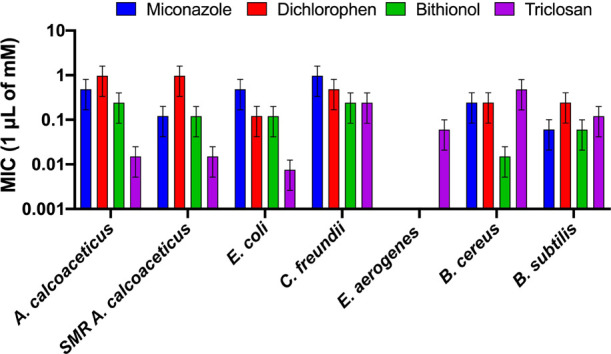

Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial Activity of the Hits

To further explore the broad-spectrum antibacterial activity of Miconazole, Dichlorophen, Bithionol, and Triclosan, our hits were tested against other Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Images of the halos produced by the drugs and their respective normalized folds relative to DMSO are shown in Figure 5. The MICs of the drugs are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Broad-spectrum antibacterial activity of hits. Zones of inhibition by our hits on SMR A. calcoaceticus, E. coli, C. freundii, E. aerogenes, B. cereus, and B. subtilis. Normalized fold changes are indicated at the bottom right corner of images. E. aerogenes was insensitive to Miconazole, Dichlorophen, and Bithionol.

Table 1. Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial Activity of Hits and Analogues as Assessed by MIC on Solid Growth Medium.

| MIC

1 μL of mM (standard deviation) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bacteria | Miconazole | Dichlorophen | Bithionol | Triclosan |

| Gram-Negative Bacteria | ||||

| A. calcoaceticus | 0.413 (0.315) | 0.825 (0.630) | 0.206 (0.157) | 0.0129 (0.0099) |

| SMR A. calcoaceticus | 0.103 (0.08) | 0.825 (0.630) | 0.103 (0.08) | 0.0129 (0.0099) |

| E. coli | 0.413 (0.315) | 0.103 (0.08) | 0.103 (0.08) | 0.00645 (0.00492) |

| C. freundii | 0.825 (0.630) | 0.413 (0.315) | 0.206 (0.157) | 0.206 (0.157) |

| E. aerogenesa | 0.0516 (0.0394) | |||

| Gram-Positive Bacteria | ||||

| B. cereus | 0.206 (0.157) | 0.206 (0.157) | 0.0129 (0.0099) | 0.413 (0.630) |

| B. subtilis | 0.0516 (0.0394) | 0.206 (0.157) | 0.0516 (0.0394) | 0.103 (0.08) |

Only Triclosan inhibited the growth of E. aerogenes on solid growth medium.

Figure 6.

Broad-spectrum antibacterial activity of hits. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) and standard deviations of Miconazole, Dichlorophen, Bithionol, and Triclosan versus select bacterial strains on solid growth medium.

All four compounds inhibited the growth of streptomycin-resistant A. calcoaceticus, indicating that the observed antibiotic effect of our drugs is not specific to one particular strain. However, the MICs for Bithionol and Miconazole do vary between these two strains, suggesting that the extent of action of the drugs might be strain-dependent. Regardless, the results highlight the possibility of effectivity against a wide range of Acinetobacter strains, even those with MDR. As expected from a known antibacterial, Triclosan worked best on Gram-negative bacteria and was the only drug that could inhibit E. aerogenes. Notably, Bithionol was the second most effective drug for Gram-negative species. In Gram-positive species, Bithionol had the lowest MICs, showing an even more robust performance than Triclosan.

Combinations of Hits

The hits were tested in combinations in order to identify drug pairs, whose antibacterial efficacy would add or synergize. Miconazole was combined with each of the Dichlorophen analogues on A. calcoaceticus and broad-spectrum strains to determine if the combination of two drugs would produce an effect greater than that of each individual drug (Figure 7). The concentrations of each drug depicted in Figure 7 are shown in Table 2.

Figure 7.

Broad-spectrum antibacterial activity of combinations of hits. Images depict zones of inhibition of B. subtilis, E. coli, C. freundii, B. cereus, A. calcoaceticus, and SMR A. calcoaceticus treated with Miconazole, Dichlorophen, Bithionol, and Triclosan combinations at concentrations shown in Table 2. DMSO serves as the negative control. Normalized fold changes are shown on the bottom right corner of each image.

Table 2. Concentrations of Drugs Used in Broad-Spectrum Analysis of Hit Combination of Hitsa.

| 1 μL

of mM |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bacteria | Miconazole | Bithionol | Miconazole | Triclosan | Miconazole | Dichlorophen |

| B. subtilis | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.013 | 0.026 | 0.05 | 0.206 |

| E. coli | 0.206 | 0.05 | 0.413 | 0.013 | 0.206 | 0.05 |

| C. freundii | 0.413 | 0.103 | 0.413 | 0.103 | 0.413 | 0.206 |

| B. cereus | 0.206 | 0.026 | 0.103 | 0.206 | 0.206 | 0.206 |

| A. calcoaceticus | 0.413 | 0.206 | 0.206 | 0.006 | 0.413 | 0.825 |

| SMR A. calcoaceticus | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.006 | 0.05 | 0.413 |

Underlined are the drug amounts at MIC.

In A. calcoaceticus, the combination of Miconazole and Dichlorophen produced the largest fold of 40.6. The combination of Miconazole and Bithionol also resulted in a large fold of 36.1. In both, the folds of the combinations are similar to the sum of the folds of the individual drugs, indicating an additive effect. However, in SMR A. calcoaceticus, the combination of Miconazole and Bithionol had a synergistic effect with a fold of 33.27, much larger than the sum of each drug’s individual folds.

In the broad-spectrum analysis, the combination therapy of Miconazole and Bithionol in B. subtilis produced the largest difference between the drugs’ individual and combination folds, suggesting a synergistic effect. Miconazole and Dichlorophen in B. subtilis had additive effects, producing a fold of 5.14, roughly equivalent to the sum of the individual drug folds.

To address therapeutic limitations for hospital-acquired ACB infections arising from the emergence of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter strains, our approach involved drug screening 1586 FDA-approved compounds from the JHCCL library. Miconazole, Dichlorophen, and Bithionol were the three compounds successfully isolated as novel hits for repurposing against A. baumannii. Further pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics studies are needed for repurposing these drugs as topical and systemic treatments against Acinetobacter species.

Miconazole is a synthetic imidazole derivative commonly used topically in ringworm and athlete’s foot infections.19 It can also be administered intravenously for systemic mycotic infections like oral or vaginal thrush.21 The wealth of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) data makes Miconazole a particularly attractive candidate for drug repurposing, as its interactions are well investigated and understood. Markedly, although it has a strong safety profile and is well tolerated as an oral medication, Miconazole has low systemic absorption and rapid clearance.22 The discrepancy in MICs that we observed between solid and liquid media is in line with this and suggests that Miconazole is more effective for topical rather than systemic application.

Dichlorophen is a halogenated phenol and anthelmintic that effectively eliminates intestinal tapeworm infections when given orally.23 Dichlorophen is 95% excreted from the body via urine and feces within 2 days of oral administration but possesses moderate toxicity that most commonly leads to contact dermatitis.24 Additional symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, urticaria, erythema, and site irritation.23 Taking into account its considerable side effects and intermediate anti-Acinetobacter activity, Dichlorophen is less promising for repurposing. However, the discovery of Dichlorophen led to the subsequent study of its analog, Bithionol.

Bithionol is a clinically approved antiparasitic with a well-established pharmacokinetics profile and demonstrated safety in humans.23 As the treatment of choice for fascioliasis, Bithionol is easily absorbed and distributed in the body, reaching its highest blood concentrations within 8 h of administration.25,26 Further demonstrating its promise as a repurposed antibacterial agent, mild side effects follow oral administration of Bithionol, including skin irritation, gastrointestinal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, and colic.27

When comparing the three novel hits and Triclosan, Bithionol worked best consistently in exhibiting antibacterial activity. Among our hits, Bithionol had the lowest MICs in both solid and liquid media and demonstrated the most robust performance against a broad spectrum of bacteria. More specifically, the MIC of Bithionol against A. calcoaceticus in broth dilution tests is 2 μM. This is a considerably safe concentration, as the cytotoxicity of Bithionol at 16 μM is still mild when tested in murine macrophages, with a 66.02% survival rate of RAW264.7 and 97.93% survival rate of C32 cell lines.19,28

To the best of our knowledge, the antibacterial effects of Bithionol have never been suggested by a publication, which supports our proposed novelty for its repurposing in ACB infections. Previous investigations into the in vivo activity of Miconazole found that it effectively inhibited Gram-positive bacteria but not Gram-negative bacteria; however, our study proposes contradicting evidence.29 Experiments by Nenoff et al. added Miconazole directly to freshly prepared agar at 60 °C before plating bacteria.29 Hence, we suspect that temperature and plating conditions prevented Miconazole from inhibiting the complex cell walls of Gram-negative bacteria. Thereupon, our findings illustrate a ground-breaking discovery that Miconazole can inhibit Gram-negative bacteria, including A. calcoaceticus, E. coli, and C. freundii.

Our findings also provide strong evidence that these drugs can be repurposed against systemic and cutaneous Acinetobacter infections. However, we suggest that using both Miconazole and Bithionol may be more effective at eliminating cutaneous A. calcoaceticus than using either drug individually. Based on the solid-phase results obtained in our combination experiments, the Miconazole–Bithionol combination therapy exhibited synergistic effects against A. calcoaceticus. The greater bactericidal effects noted in our experiments demonstrate comparability in treatment modality for ACB infections, which are currently often treated with combination antimicrobial regimens. Also, since the combination was tested successfully against a broad spectrum, with additive effects noted in B. subtilis and SMR A. calcoaceticus, combining Miconazole and Bithionol could likely have positive implications in other bacterial infections, including drug-resistant ones.

The promising results obtained from this study substantiate efforts to develop Bithionol, Dichlorophen, and Miconazole as treatments for ACB infections. An imminent future direction is to simulate systemic use of these drugs by exploring their broad-spectrum activity in broth dilution tests. We suggest an equal fate for our proposed combination therapy of Miconazole and Bithionol. Because A. calcoaceticus served as a surrogate, formal confirmatory tests in A. baumannii and other Acinetobacter strains are also needed. To study the efficacy of our drugs in vivo, Drosophila melanogaster could serve as our insect model to analyze antibacterial properties and interdrug interactions when used in combination therapy. Ultimately, our study provides a realistic and promising direction for alternative treatments of emerging hospital-acquired infections. In the future, we will also test the combinations that include all three of our hits.

Conclusions

Since A. baumannii is an opportunistic nosocomial pathogen, few antibiotics effectively treat the infections. Especially with rising numbers of multidrug resistant infections, new or alternative bactericides targeting Acinetobacter are needed. In screening the commercially available drugs of the JHCCL library, we have identified three drugs capable of inhibiting A. calcoaceticus growth. There is high potential for Bithionol, Miconazole, and Dichlorophen as repurposed drugs.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

A. calcoaceticus (ATCC 31926) was used in this study. A streptomycin-resistant (SMR) strain of A. calcoaceticus was purchased from Carolina Biological Supply Company. A. calcoaceticus cultures grown overnight on Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) solid agar or in BHI broth were incubated at 37 °C.

For the analysis of the broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties of hits, additional bacteria including Bacillus cereus (ATCC 14579), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), Escherichia coli (C600), Citrobacter freundii (ATCC 8090), and Enterobacter aerogenes (ATCC 51697) were used. B. cereus, B. subtilis, and E. coli were cultured in lysogeny broth (LB) and on solid LB agar at 37 °C with shaking overnight. C. freundii and E. aerogenes were incubated in tryptic soy broth (TSB) or on solid TSB agar (TSA) at 30 °C overnight. For most of the experiments, 75 μL of A. calcoaceticus and 100 μL of all other bacterial species diluted to OD 0.1were utilized for lawn spreads, unless stated otherwise.

Chemicals

The library of compounds screened against A. calcoaceticus consisted of 1586 drugs from the Johns Hopkins Clinical Compound Library (JHCCL) version 1.33. As previously described by Kim et al., the drugs were prepared with DMSO to a stock concentration of 3.3 mM in 96-well plates and stored at −20 °C before thawing to room temperature prior to use.30

Miconazole and Dichlorophen were identified as hits during first screening and were retested as follows. Solid Miconazole nitrate salt was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and Dichlorophen was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA). Dichlorophen structural analogues, Bithionol and Triclosan, were obtained from Fluka Analytical and Alfa Aesar, respectively. DMSO from Amresco was utilized as a solvent to dilute the drugs to various concentrations.

Drug Screening of Anti-Acinetobacter calcoaceticus Activity

The sensitivity of A. calcoaceticus to our chemical library was tested by dropping 1 μL of each drug at 3.3 mM onto a 100 μL lawn of A. calcoaceticus spread on BHI agar plates. After incubating overnight at 37 °C, the plates were examined. Disruption of bacterial growth, visualized as a halo of bacterial clearance or growth stagnation, was noted. Drugs that created observable halos were prioritized on the basis of novelty as a Gram-negative bactericide, practicality of administration, and known contraindications. The antibacterial effects of the drugs of interest were then retested using the same drop test method on identically prepared Petri dishes, and their halos were compared to that of Doxycycline antibiotic (positive control) and DMSO (negative control).

ImageJ software was used to digitally quantify the mean inverted pixels of the zones of inhibition and corrected by that of the background.31 Normalized fold changes were subsequently calculated by dividing the corrected mean pixels of the halos by that of DMSO. Drugs that produced halos with a normalized fold change larger than 1 and comparable to that of Doxycycline continued on to the determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC).

Diffusion Susceptibility and Broth Dilution Tests of Identified Hits

We performed a modified Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) diffusion susceptibility assay, where two-fold serial dilutions of 3.3 mM drug stock concentration were prepared for all tests by first mixing one part stock solution with equal parts DMSO. For subsequent dilutions, aliquots from the previous dilution were mixed with equal parts DMSO.

In MIC determinations for A. calcoaceticus and broad-spectrum analysis, customized diffusion susceptibility tests were used. Agar plates were spread with respective amounts of bacteria. One μL of each drug dilution ranging from 3.3 to 0.00645 mM was spotted using 1 μL of DMSO as a negative control. The plates were incubated at their respective temperatures for 24 h. Normalized fold change was calculated as previously mentioned. The MIC was determined as the lowest drug concentration that produced a halo greater than that produced by DMSO, with a normalized fold change larger than 1.

For broth dilution testing, overnight bacterial cultures were diluted in BHI media at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1. A total of 100 μL of the diluted culture was aliquoted into each well of a 96-well plate, and 1 μL of the drugs at concentrations of 3.3, 1.65, 0.825, 0.413, 0.206, 0.103, and 0.0516 mM was added to their respective wells. The corresponding final drug concentrations ranged from 33 to 0.5 μM. A total of 100 μL of bacteria suspended in BHI media with 1 μL of DMSO served as the positive control, while 100 μL of media without bacteria served as the negative control. Plates were incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 14 h, and the OD600 of each well was measured and recorded every 10 min. The MIC was determined as the lowest concentration of drug that produced a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to the positive control. Tests in solid and liquid media were run in triplicate.

The data for broth dilution tests are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The possible statistical differences among different concentrations of hits were tested using non-parametric T-test. A probability value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The EC50 value, defined as the concentration that effectively eliminates half of the bacterial population, was calculated using the area under the curve (AUC) measurements by GraphPad Prism7 software.

Diffusion Susceptibility Tests of Combination Therapies

To investigate the combination therapy potential of Miconazole with Dichlorophen, Bithionol, or Triclosan, diffusion susceptibility tests were performed on all bacterial strains with the exception of E. aerogenes, as only Triclosan inhibited its growth. Combinations were not tested between Dichlorophen, Triclosan, and Bithionol because as structural analogues, they are predicted to have similar mechanisms of action and not behave synergistically when combined.

Three 1 μL drops of Miconazole were added at MIC and two subsequent dilutions at sub-MIC. A 1 μL drop of Dichlorophen, Bithionol, or Triclosan was added to a second row in the same manner. Combinations were tested in the third row by dropping 1 μL of Miconazole and allowing it to be fully absorbed by the agar before dropping 1 μL of Dichlorophen, Bithionol, or Triclosan in the same spot. Two negative controls were used: 1 μL of DMSO (for individually dotted drugs) and 1 μL of DMSO atop an absorbed drop of 1 μL of DMSO (for combined drugs). Drug concentrations are shown in Table 2 and Figure 7. The normalized fold changes of the drug halos were calculated with ImageJ. A successful drug combination was determined as a normalized combined drug fold greater than the sum of individual drug.

Image Capture and Processing

All images were taken using a 12MP wide-angle iSight camera with F1.8 aperture and touch-to-focus capabilities. Images are unaltered stock photos.

Acknowledgments

A.L. acknowledges support from The Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation. M.M.S. acknowledges support from City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center through the KL2 Mentored Career Development Award Program of the Inland California Translational Consortium (GR720001).

Glossary

Abbreviations Used

- ATCC

American Tissue Culture Collection

- JHCCL

Johns Hopkins Clinical Compound Library

- OD

optical density

- US FDA

United States Food and Drug Administration

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- CLSI

Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute

- LB

lysogeny broth

- TSB

tryptic soy broth

- BHI

brain heart infusion.

Author Contributions

† T.H.K. and S.N.M.W. contributed equally to this manuscript.

Author Contributions

A.L. and M.M.S. designed the research; J.P.G.D., G.H., T.H.K., A.L., S.N.M.W., and S.A. performed the research. All authors contributed to the framework of the article; T.H.K. and S.N.M.W. took the lead in writing the paper. T.H.K. contributed critical revisions to the final manuscript with the oversight of A.L. and M.M.S. S.N.M.W. created the graphical abstract with edits from T.H.K.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Abubakar I. I.; Tillmann T.; Banerjee A. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015, 385, 117–171. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/antibiotic-market

- https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/index.html

- Rice L. B. Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: no ESKAPE. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 197, 1079–1081. 10.1086/533452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed

- Antunes L. C. S.; Visca P.; Towner K. J. Acinetobacter baumannii: evolution of a global pathogen. Pathog. Dis. 2014, 71, 292–301. 10.1111/2049-632X.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith M. E.; Ceremuga J. M.; Ellis M. W.; Guymon C. H.; Hospenthal D. R.; Murray C. K. Acinetobacter skin colonization of US Army Soldiers. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2006, 27, 659–661. 10.1086/506596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diancourt L.; Passet V.; Nemec A.; Dijkshoorn L.; Brisse S. The population structure of Acinetobacter baumannii: expanding multiresistant clones from an ancestral susceptible genetic pool. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10034 10.1371/journal.pone.0010034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. K.; Hospenthal D. R. Treatment of multidrug resistant Acinetobacter. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 18, 502–506. 10.1097/01.qco.0000185985.64759.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow J. M. III; Wells G.; Pesci E. C. Desiccation tolerance in Acinetobacter baumannii is mediated by the two-component response regulator BfmR. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0205638 10.1371/journal.pone.0205638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawad A.; Snelling A. M.; Heritage J.; Hawkey P. M. Exceptional desiccation tolerance of Acinetobacter radioresistens. J. Hosp. Infect. 1998, 39, 235–240. 10.1016/S0195-6701(98)90263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra S.; Galande A. A fluoroquinolone-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii without the quinolone resistance-determining region mutations. J Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 2668–2670. 10.1093/jac/dkr364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbain J.; Peleg A. Y. Treatment of Acinetobacter infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 79–84. 10.1086/653120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisinger E.; Mortman N. J.; Vargas-Cuebas G.; Tai A. K.; Isberg R. R. A global regulatory system links virulence and antibiotic resistance to envelope homeostasis in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007030 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomo R. A.; Szabo D. Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, S49–S56. 10.1086/504477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnier P.; Poirel L.; Pitout M.; Nordmann P. Carbapenem-resistant and OXA-23-producing Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in the United Arab Emirates. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 879–882. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg A. Y.; Adams J.; Paterson D. L. Tigecycline Efflux as a Mechanism for Nonsusceptibility in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 2065–2069. 10.1128/AAC.01198-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drown B. S.; Hergenrother P. J. Going on offense against the gram-negative defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 6530–6532. 10.1073/pnas.1807278115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi W.; Zilbermintz L.; Cheng L. W.; Zozaya J.; Tran S. H.; Elliott J. H.; Polukhina K.; Manasherob R.; Li A.; Chi X.; Gharaibeh D.; Kenny T.; Zamani R.; Soloveva V.; Haddow A. D.; Nasar F.; Bavari S.; Bassik M. C.; Cohen S. N.; Levitin A.; Martchenko M. Bithionol blocks pathogenicity of bacterial toxins, ricin, and Zika virus. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34475. 10.1038/srep34475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5564

- Fan S.; Liu X.; Liang Y. Miconazole nitrate vaginal suppository 1,200 mg versus oral fluconazole 150 mg in treating severe vulvovaginal candidiasis. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2015, 80, 113–118. 10.1159/000371759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade T. R.; Jones H. E.; Chanda J. J. Intravenous miconazole therapy of mycotic infections. Arch. Intern. Med. 1979, 139, 784–786. 10.1001/archinte.1979.03630440046016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamarik T. A. Safety assessment of dichlorophene and chlorophene. Int. J. Toxicol. 2004, 23, 1–27. 10.1080/10915810490274289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langrand J.; Moesch C.; Le Grand R.; Bloch V.; Garnier R.; Baud F. J.; Megarbane B. A life-threatening dichlorophen poisoning case: clinical features and kinetics study. Clin. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 178–181. 10.3109/15563650.2013.776069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyagari V. N.; Brard L. Bithionol inhibits ovarian cancer cell growth in vitro - studies on mechanism(s) of action. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 61. 10.1186/1471-2407-14-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacq Y.; Besnier J. M.; Duong T.-H.; Pavie G.; Metman E.-H.; Choutet P. Successful treatment of acute fascioliasis with bithionol. Hepatology 1991, 14, 1066–1069. 10.1002/hep.1840140620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokogawa M.; Yoshimura H.; Okura T.; Sano M.; Tsuji M.; Iwasaki M.; Hirose H. Chemotherapy of Paragonimiasis with Bithionol. II. Clinical Observations on the Treatment with Bithionol. Jpn. J. Parasitol. 1961, 10, 317–327. [Google Scholar]

- Zilbermintz L.; Leonardi W.; Jeong S.-Y.; Sjodt M.; McComb R.; Ho C.-L. C.; Retterer C.; Gharaibeh D.; Zamani R.; Soloveva V.; Bavari S.; Levitin A.; West J.; Bradley K. A.; Clubb R. T.; Cohen S. N.; Gupta V.; Martchenko M. Identification of agents effective against multiple toxins and viruses by host-oriented cell targeting. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13476. 10.1038/srep13476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenoff P.; Koch D.; Krüger C.; Drechsel C.; Mayser P. New insights on the antibacterial efficacy of miconazole in vitro. Mycoses 2017, 60, 552–557. 10.1111/myc.12620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.; Zilbermintz L.; Martchenko M. Repurposing FDA approved drugs against the human fungal pathogen, Candida albicans. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2015, 14, 32. 10.1186/s12941-015-0090-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/