Abstract

Background

Depression in childhood frequently involves significant impairment, comorbidity, stress, and mental health problems within the family. Family-Focused Treatment for Childhood Depression (FFT-CD) is a 15-session developmentally-informed, evidence-based intervention targeting family interactions to enhance resiliency within the family system to improve and manage childhood depression.

Methods

We present the conceptual framework underlying FFT-CD, the treatment development process, the intervention strategies, a case illustration, and efficacy data from a recent 2-site randomized clinical trial (N = 134) of 7–14 year old children randomly assigned to FFT-CD or individual supportive psychotherapy (IP) conditions.

Results

Compared to children randomized to IP, those randomized to FFT-CD showed higher rates of depression response (≥50% Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised reduction) across the course of acute treatment (77.7% vs. 59.9%, t = 1.97, p = .0498). The rate of improvement overall leveled off following treatment with a high rate of recovery from index depressive episodes in both groups (estimated 76% FFT-CD, 77% IP), and there was an attenuation of observed group differences. By final follow-up, one FFT-CD child and six IP children had suffered depressive recurrences, and four IP children attempted suicide.

Limitations

Without a no treatment control group it is not possible to disentangle the impact of the interventions from time alone.

Conclusions

While seldom evaluated, family interventions may be particularly appropriate for childhood depression. FFT-CD has demonstrated efficacy compared to individual supportive therapy. However, findings underscore the need for an extended/chronic disease model to enhance outcomes and reduce risk over time.

Keywords: Depression, family-focused therapy, stress, children, mood disorders, interpersonal model, cognitive behavioral, psychoeducation

Depression is a common and impairing disorder, impacting approximately 16.2% of all US adults at some point in their lives (Kessler et al., 2003). Although the first depressive episode typically occurs in adolescence (Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Merikangas et al., 2003), childhood-onset is associated with significant morbidity, high risk of relapse, and high levels of dysfunction due to its early onset and interference with negotiation of developmental tasks (e.g., Birmaher et al., 2002; Puig-Antich et al., 1985; Kovacs, et al., 1996). Of the growing number of treatments for youth depression, the vast majority 1) target adolescents, 2) focus primarily on individual or group-based treatment with limited family involvement, or 3) have been tested on samples not restricted to youth with clinically elevated depression (Weersing et al., 2017). Family-Focused Treatment for Childhood Depression (FFT-CD) addresses these gaps as an effective treatment for children and early adolescents (Tompson, Langer et al., 2017; Tompson, Sugar et al., 2017; Asarnow et al., in press). In FFT-CD, therapists work with youth and families together to learn evidence-based skills, capitalizing on the important role of parents and families in youth development (Ladd, 1999; Steinberg, 2001).

FFT-CD was the first treatment for childhood depression with the individual family unit as the primary focus (see Tompson et al., 2007). Even as other treatments, as described below, have further integrated the family into treatment, FFT-CD remains the only one with a primary focus on working with families to improve depression symptoms through enhancing family relationships. For this reason, FFT-CD fills an important treatment niche. This paper presents the conceptual framework underlying FFT-CD, the treatment development process, the intervention strategies, a case illustration, and efficacy data from a recent 2-site randomized clinical trial (N = 134) of 7–14 year old children randomly assigned to FFT-CD or individual supportive psychotherapy (IP) conditions.

Nature of Depression During Childhood and Rationale for a Family-Based Approach

Although depression is diagnosed in DSM-5 (APA, 2013) using almost the same criteria used to diagnose adult depression, its symptoms and treatment must be viewed through a developmental lens. Depression in childhood differs in its presentation, comorbidity, familiality and stress profile. We argue that these differences underscore the importance of incorporating families into an effective treatment model for depression during this developmental period.

First, depression in childhood may present differently with psychosomatic symptoms (e.g., headaches, stomach aches) and irritability as frequent concomitants (Birmaher et al., 2004), making it likely that parents may fail to recognize the symptoms as part of a depressive picture and rather interpret (and respond to) them as willful misbehavior. Further, symptoms like irritability and anhedonia may reduce the likelihood of positive and rewarding parent–child interactions and increase parental frustration and the likelihood of parent–child conflict. This speaks to the need for a treatment model that helps parents and children build skills together for managing depression.

Second, comorbidity is common in depression across the lifespan, but the nature of that comorbidity differs developmentally (Avenevoli et al., 2008). Childhood depression is often preceded by anxiety and behavioral disorders and may represent an unfolding of a gradual psychopathological process, a complication of preexisting mental health challenges, or shared risk factors (genetic and/or psychosocial) (Maughan et al., 2013). Regardless of the underlying process, this comorbidity requires a treatment model that can be applied flexibly and incorporate interventions targeting a range of symptom presentations and additional targeted intervention components, including parenting strategies, exposure procedures, and consideration of specific learning challenges.

Third, depression in general is highly familial, but this is particularly true among youth with depression, with our data indicating 70% of depressed youth had at least one depressed parent (Tompson et al., 2015). Further, evidence suggests a link in time between depressive episodes in parents and children, with depression in one increasing likelihood of depression in the other (Hammen et al., 1991). Although referring depressed parents to their own treatment may be one strategy, studies suggest such referrals often do not result in treatment (National Research Council, 2009). Incorporating parents in regular treatment for depression in childhood allows us to more directly provide psychoeducation about and build skills applicable to both children and adults struggling with depressive symptoms and disorders.

Finally, depression typically occurs within a context of stress. The nature of the stressors associated with depression risk may differ across development. Given the centrality of families and schools during childhood, it is not surprising to find that stressors occurring in families (e.g., conflict, separation, maltreatment) and peer groups/schools (e.g., bullying, peer conflicts) are major risk factors for depression (Jaffee et al., 2002). This speaks to the need to work closely with families to decrease stress and improve coping.

In sum, our current understanding of the nature of youth depression – its presentation, comorbidity, familiality and stress context – suggests the importance of a treatment model that integrates families as a focus of treatment for depressive disorders.

Conceptual Framework Underlying FFT-CD

The development of FFT-CD was influenced by a vulnerability-stress framework (Hankin and Abela, 2005) and interpersonal models (Rudolph et al., 2008). Youth depression represents a biopsychosocial phenomenon. Biological factors (e.g., genetics, neural dysregulation) and environmental vulnerabilities (e.g., ongoing stressors, socioeconomic deprivations, loss experiences) may contribute to the risk for depression. These vulnerabilities and stressors may then be impacted and altered by negative cognitive processes and subsequent stressors to shape the course and outcome of depression. As noted above, parental depression is a common risk factor for youth depression and may contribute to both genetic and environmental vulnerability. Specific child attributes (e.g., difficult temperament), early emerging mental health challenges (e.g., anxiety and/or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), and cognitive challenges (e.g., learning disorders and autism spectrum disorder) may contribute to depression vulnerability directly and may also fuel the stress that then interacts with vulnerability to increase risk throughout childhood and beyond.

Depression throughout development occurs within an interpersonal context (Joiner and Coyne, 1999; Hammen and Shih, 2014). Research specifically focused on middle and late childhood underscores its relational/interpersonal sequelae (Rudolph et al., 2000; Rudolph et al., 2008). An interpersonal model posits that depressive symptoms and interpersonal stress interact bidirectionally. Interpersonal stress contributes to depressive symptoms and those symptoms increase risk of further interpersonal stress. Depressive symptoms, particularly irritability, anhedonia and social withdrawal, contribute to interpersonal problems, and this worsened stress context further contributes to depressive symptoms, fueling a downward spiral of intensifying symptoms and stress. Families play a central role during middle childhood and early adolescence, and they may be particularly likely to be drawn into this downward spiral. During childhood these processes may increasingly contribute to negative thoughts about the world, negative perceptions of the self, negative attribution about events, and reduced engagement in enjoyable activities and interpersonal interactions. Although depression may develop as a function of numerous interacting vulnerability and stress factors, the symptoms are increasingly maintained by an environment to which the symptoms contribute, and so on.

Current status of child depression treatments

Despite the longstanding recognition of childhood depression as a related but distinct diagnosis from adult depression (Cantwell and Carlson, 1979) and accumulating evidence of the long-term course of childhood depression (Weissman et al., 1999), the evidence base for child-focused (as opposed to adolescent-focused) psychosocial depression treatments remains sparse (Weersing et al., 2017). As of Weersing et al.’s evidence base update on psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression (2017), there were multiple adolescent-focused treatment approaches reaching “Level 1: Well-Established” criteria (Southam-Gerow and Prinstein, 2014), yet for child depression treatment, no treatment approach surpassed “Level 3: Possibly Efficacious.” In other words, no child depression treatment approach had at least two methodologically rigorous randomized experiments (see Chambless and Hollon, 1998) showing the treatment is superior to a control group. In part, this likely reflects the limited number of studies conducted on child depression (e.g., seven randomized trials testing CBT in children compared to 27 trials of CBT in adolescents). It is possible that challenges in creating developmentally appropriate treatments for children with less advanced psychosocial and cognitive skills has slowed the development and testing of treatments targeting childhood depression. The absence of any treatment approach meeting Level 2 support or higher likely also reflects the challenges specific to treating child depression (e.g., only one of the seven randomized trials testing CBT demonstrated positive findings for CBT over a waitlist or psychologically inert control condition). Although there was family involvement in many of these individual and group-based treatments (e.g., periodic parent meetings and brief inclusion of the parent at the conclusion of each session; Weisz, et al., 2009), the family was neither the focus of nor regular participants in these treatments, representing a potential barrier to treatment effectiveness, in light of our understanding of childhood depression, discussed above.

The Weersing et al. (2017) review, published prior to publication of the FFT-CD findings (Tompson, Sugar et al., 2017; Asarnow et al., in press), included only one treatment study with a family-based intervention condition for childhood depression. In this study, children and families receiving “Systems Integrative Family Therapy” showed significant improvement from baseline that was equivalent in strength to the comparison condition of individual psychodynamic therapy (Trowell et al., 2007). Thus, family-based interventions for child depression met criteria for only “Level 4: Experimental.” However, although not included in the timeframe of the Weersing et al. (2017) review, Dietz et al. (2015) found that Family-Based Interpersonal Psychotherapy (FB-IPT) outperformed child-centered therapy (CCT) on diagnostic remission and symptom reduction in a sample of preadolescents. FB-IPT targeted parent–child conflict and interpersonal impairment. Parents and children met individually with the therapist for the first third of treatment, and for the remainder of treatment, sessions were split such that the second half of the sessions had parents, children, and therapists meeting together. Other child depression treatments (which did not meet Weersing et al., 2017 inclusion criteria) have included the parents, yet the focus was primarily on parent education or developing parenting skills in sessions with only parents. For example, Asarnow et al. (2002) reported on a multi-week group treatment for fourth- through sixth-graders who self-reported depressive symptoms. After nine group sessions there was a 90-minute multi-family session in which therapists and children reviewed with and taught their parents the skills the children had learned throughout the treatment. This treatment outperformed a waitlist control. Fristad et al. (2009) found that multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy plus treatment as usual led to decreased symptoms relative to a treatment as usual condition for eight to 12-year-olds with mood disorders. Multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy focused on parent skill development, though there were separate groups for parents and children. Taken together, the need for more research on child depression treatments is clear, and multiple studies support the inclusion of parents in treatment.

FFT-CD Overview

FFT-CD was developed with the vulnerability-stress and interpersonal models clearly in mind (Tompson, Langer, et al., 2017). The goal is to assist children and families to see the powerful links between mood and interpersonal processes in their lives and to use this model to effect change – decreasing negative interactions and building on their relational strengths. FFT-CD is designed to reverse the downward spiral of depression and negative interpersonal interactions and provide enhanced support in combating the negative thoughts and feelings associated with depression. Table 1 summarizes the five treatment modules, the typical number of sessions, and the modules’ goals; we detail these below, and then provide a brief case illustration.

Table 1.

FFT-CD Session Goals and Strategies

| Module Name, Number of Sessions | Goals |

|---|---|

| Module 1: | Join with family |

| Understanding Depression | Present interpersonal model |

| 3 sessions | Conceptualize treatment goals in terms of upward and downward spirals |

| Module 2: | Increase positive feedback |

| Families Talking Together 3 – 4 sessions | Promote active listening |

| Improve skill in providing negative feedback | |

| Module 3: | Identify pleasurable events/activities |

| Things We Do Affect How We Feel 2 – 3 sessions | Promote assertiveness |

| Plan enjoyable family and individual activities | |

| Module 4: | Enhance problem-identification |

| We Can Solve Problems Together | Institute mood monitoring |

| 3 – 4 sessions | Teach the problem-solving model |

| Solve family problems | |

| Module 5: | Promote skill generalization |

| Saying Goodbye | Empower family to continue process |

| 1 – 2 sessions | Plan for future |

Initial Evaluation/Assessment

Prior to beginning treatment, we conduct a thorough evaluation of the child’s depressive symptoms and comorbidities, parent(s) mental health, and family and other stressors in the child’s life. Through understanding the current levels and areas of conflict, positive interactions with the family and community, and degree of agreement between members, we can develop a model for understanding factors contributing to the current symptoms and how they are maintained.

Structure of Treatment

We typically conduct FFT-CD over 12–16 sessions. After one individual session each for the parent(s) and the child, the remaining sessions are conjoint and may include siblings when helpful. Sessions typically maintain a regular structure: (1) the therapist meets briefly with the child to assess depressive symptoms, (2) the parent(s) joins the session and family members briefly discuss any recent important events and review the previous session’s assigned skill practice, (3) the therapist presents a new concept or skill, connecting each new concept or skill to the family’s interactional spirals and impacts on moods, (4) the therapist guides the family in practicing and applying what they learned through role plays, games, discussions, and problem-solving exercises, and (5) the therapist assigns at-home skill practice to encourage generalization of skills to the home environment.

Module 1, Understanding Depression

This module includes 3 sessions – individual sessions with the parent(s) and child and one joint session. The individual sessions focus on offering developmentally appropriate feedback from the evaluation and psychoeducation about depression. By presenting a model in which the child’s unique combination of risk factors and circumstances have combined to produce the current depression and emphasizing the role of the family in helping build skills toward recovery, the therapist builds the rationale for the family-based approach. In the child meeting, the therapist introduces the CBT model, emphasizing the interplay between thoughts, feelings, and actions, and emphasizing that treatment will focus particularly on the link between moods/feelings and family interactions. In the final session of this model, the parent(s) and child are brought together to review the interpersonal model of depression and rationale for treatment. The therapist describes upward spirals (i.e., positive interpersonal interactions contribute to positive emotions, further fueling positive interpersonal interactions) and downward spirals (negative interpersonal communication contributes to negative emotions, further fueling negative interactions) and assists families in sharing their own spirals. The therapist emphasizes the therapy goals of “starting upward spirals and keeping them going” and “stopping downward spirals.” During our early treatment development work and in the time since, we have found that youth as young as 7 years of age appear to readily understand the concept of spirals, making it a useful framework for the FFT-CD intervention (Tompson et al., 2007; Tompson et al., 2012).

Module 2, Families Talking Together

This 3–4 session module focuses on increasing the child’s assertiveness skills, decreasing depressive withdrawal and irritability, and encouraging the development of empathy between family members. Therapists teach giving positive feedback (“saying what you liked”), active listening, and giving negative feedback (“saying what you didn’t like”) skills. By starting out communication training with a positive focus and by regularly normalizing difficulties, the therapist builds on the still-new relationship with the child and family and enhances the likelihood that more difficult issues can be addressed over time.

Giving positive feedback to one another is framed as an important strategy for creating upward spirals; giving positive feedback serves two important functions: 1) it makes family members feel appreciated and valued and 2) it gives others important information for future behavior. Having developed “positive feedback” skills, the family progresses to focus on “Active Listening.” When learning the active listening communication skill, one member (usually a parent) practices active listening while another (usually the child) describes a benign activity, for example, “how to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.” As we move forward, we address more emotional content about someone else, for example, role playing a child who just found out about a bad test grade. We then focus on personal experience, for example asking the child (or parent) to describe a time when they felt sad. This process allows the child to become comfortable with role playing and the parent to become increasingly skilled in the listener role before approaching more sensitive material. Finally, the focus turns to giving negative feedback, which is a strategy to stop downward spirals. The negative feedback steps ensure that the person providing the feedback shares specific, behavioral information and limits overly general feedback and harsh or emotionally-laden criticism. The family practices offering negative feedback using hypothetical examples they draw from an envelope before moving to examples from their own family. As with our active listening exercise, families begin with benign, less personal content (e.g., cracker crumbs on the sofa) to more personally relevant, affectively charged examples (e.g., homework isn’t completed).

Module 3, Things We Do Affect How We Feel

This 2–3 session module uses behavioral activation strategies to increase reinforcers in the child’s environment through positive family interactions. The therapist presents doing enjoyable activities together as another strategy for initiating and maintaining upward spirals and reversing downward spirals. Family members write down fun activities that make themselves feel better when in a bad mood and regular enjoyable activities that promote wellness on a regular basis. The therapist introduces the “asking for what you want” communication skill and the family role-plays asking others to engage in activities together, formulating specific requests and conveying how the activity would make them feel. In addition to planning mutually enjoyable activities, these activities increase awareness of others’ needs and desires and stresses, building greater empathy within the family. The therapist assigns at-home practice of planning and implementing enjoyable (and feasible) family activities.

Module 4, We Can Solve Problems Together

This 3–4 session module is divided into two portions—identifying problems and solving problems. Emphasizing that unsolved problems can lead to downward spirals, the therapist normalizes problems and reframes them as choices/opportunities to problem solve. The therapist guides families in identifying problems outside, and then inside the family environment. At this point, the therapist introduces taking one’s “emotional temperature” to monitor mood. The therapist explains how problems are especially difficult to solve when people are upset and encourages at-home practice identifying family problems and using the feeling thermometer to monitor mood associated with each problem.

The second portion of this module focuses on how to solve the problems that the family identified — developing conflict resolution skills, empowering the family to better solve problems, and encouraging flexibility. In these sessions, the therapist provides a step-by-step problem-solving model, including collaboratively (a) agreeing on the problem, (b) brainstorming possible solutions, (c) discussing the pros and cons of each option, (d) choosing an initial solution to try, (e) implementing the solution, and (f) reviewing/troubleshooting/praising after the solution has been implemented. The therapist guides the family through solving a specific problem and assigns family problem-solving (a solvable problem) for at-home practice.

Throughout treatment the therapist is looking for “core” downward spirals. These are conflicts that repeat and represent ongoing, unsolved relationship dynamics and/or individual problems. Typical spirals in families include difficulties with sibling conflicts, chores, family responsibilities, and academic demands. The core downward spirals often become the focus of intensive communication and problem-solving efforts.

Module 5, Saying Goodbye

The last two sessions are spent consolidating treatment gains, discussing high risk situations, considering relapse prevention strategies, and preparing for treatment termination. To consolidate treatment gains, the therapist gives the child a booklet with all the handouts used during therapy and has the child briefly recount their memories of each. High risk situations – those that may trigger a relapse of symptoms – differ significantly for each child but may include going back to school, final exams, traveling, and other challenging situations. Using the problem-solving approach, the therapist works with the family to develop a relapse prevention plan that includes attending to early signs of depression relapse/recurrence and managing anticipated future stressors. We frequently ask the family to problem-solve about strategies to maintain therapy gains after treatment, including implementing weekly family meetings. Finally, the family discusses gains yet to be made (e.g., comorbid conditions) and potential treatment options.

Addressing Barriers to Treatment and Working across the Age Span

Numerous barriers need to be overcome when attempting to implement a family-based treatment. For example, contending with difficult family scheduling issues, separated parents, and highly strained family relationships can all prove quite challenging. We are usually able to address treatment barriers through flexibility in the times when families can be seen, providing the opportunity to include younger siblings (e.g., toddlers) in treatment sessions, using the problem-solving framework to engage families in finding solutions, working with specific subsystems of the family (e.g., child with one parent, parents only, child and siblings), and teaching communication skills that emphasize specific, focused communication and avoid harsh and generalized complaints/criticisms.

We have also found that we can use FFT-CD with a wide range of youth between ages 7 and 14. Despite significant variations in cognitive capacity, need for autonomy and privacy, and communication abilities, we find that only minor adjustments are needed for our oldest to our youngest participants. Specifically, with our youngest participants, we tend to use brightly colored poker chips as tokens of appreciation throughout session and in at-home work, whereas with our older participants we used brightly colored sticky notes or “thanks notes” to convey appreciation. We also provide slightly more individual time at the outset of our sessions with our older participants, although the difference has only been 5 to 10 minutes typically. With the younger children we include more games and practice (a gradual approach); with the older youth we can dig right in to concerns and conflicts using our communication training and problem-solving skills models.

Case Illustration

Initial Presentation

“Ayanna,” a fictional 10-year-old, African American girl, is an amalgamation of real cases that will serve as an illustration of FFT-CD. As many of the families reported in the FFT-CD randomized trial (Tompson, Sugar et al., 2017), Ayanna’s parents noted that Ayanna had been a “sensitive soul” for as long as they could remember. Early in elementary school, Ayanna began to withdraw, saying that she didn’t want to attend school, and that no one liked her, and she didn’t like anyone else. Her teachers have consistently told Ayanna’s parents that she is frequently tired and distracted. When Ayanna’s parents encourage Ayanna to join extracurricular activities, she responds irritably and tells them she wouldn’t have fun there and that they should stop annoying her. Ayanna tells the therapist she’s been feeling really sad most of the time, and that she’s had trouble sleeping and paying attention at school. Overall, she says she just doesn’t want to do anything and she feels really bad about herself. She doesn’t think that treatment will help, but she’s willing to give it a shot.

Early Phase of Treatment

The first session, a parent psychoeducation session, provided an opportunity for the therapist and parents to discuss how the course of Ayanna’s depression had developed, to allay concerns and misconceptions about depression, and for the therapist to frame FFT-CD as a way to help families better cope with stress. The therapist, while acknowledging that an early onset of depression does increase the likelihood of future depressive episodes, emphasized the positive: that there are skills that could help and that treatment early in Ayanna’s life provides many opportunities to build those skills. The therapist reinforced that parents hold a lot of power and influence in their child’s life, and praised Ayanna’s parents for working hard to help Ayanna, including by committing to treatment. The therapist normalized the stress that the parents reported as Ayanna had struggled in recent years, and the therapist worked to instill hope.

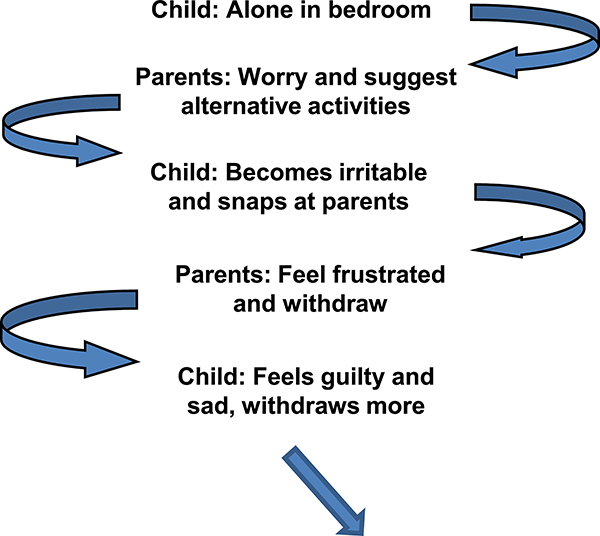

When the therapist met alone with Ayanna for the second session, Ayanna linked feelings with colors (e.g., anger felt orange to her) and shared with the therapist times at which she felt different emotions. The therapist validated for Ayanna that 1) almost everyone experiences a wide range of emotions like her, but also that 2) she’s been “feeling crappy” a lot for a while now, and that this is something that we’re going to work on. The therapist used one of Ayanna’s emotion/color examples to map out how thoughts, actions, and feelings change within an interpersonal context. They drew out this downward spiral (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ayanna’s Downward Spiral

In the final Module 1 session, Ayanna shared information about downward and upward spirals with her parents. The therapist highlighted the interpersonal nature of the family’s example spirals, and reinforced that everyone in the family is involved in these spirals, and therefore, everyone in the family will need to work to change them.

Middle Phase of Treatment

To begin the transition to skill building, the therapist noted instances in which Ayanna would get frustrated with her parents’ responses to her low mood, her parents would feel more helpless and withdraw from Ayanna, and then Ayanna would feel even lonelier. The therapist used the first communication skill, “Saying What You Liked,” to help parents (and Ayanna) shift their focus to positive behaviors, changing family interaction patterns. This early communication work helped to start some new upward spirals and parents reported that it helped them identify other ways to interact with Ayanna instead of offering her suggestions. Given the family’s encouraging response, the therapist began each session by giving family members opportunities to provide positive feedback. Ayanna and her parents continued to work on active listening and providing negative feedback (“Saying What You Didn’t Like”), interspersing the provision of positive feedback with negative feedback to keep family members’ emotional temperatures in a range that is conducive to learning and practicing new skills. Once the family had sufficient practice with all communication skills, the therapist facilitated family discussion about some of the core downward spirals (illustrated in Figure 1)

Following Communication Training the therapist introduced Behavioral Activation. Given Ayanna’s withdrawal from (and lack of interest in) a range of activities, the therapist expected this skill to be challenging for Ayanna, and also especially important. The therapist began by guiding the parents in generating and sharing ideas for themselves that were both practical and included activities done individually, with family, and with friends. After demonstrating that this is a task for everyone, the therapist helped Ayanna generate some ideas. To encourage Ayanna’s buy-in, the therapist (after conferring with parents about which special activities were practical) worked with Ayanna on the “asking for what you want” skill, and gently guided Ayanna to pick one of the special activities that she knew Ayanna’s parents could do.

With improved communication skills and some improvement in Ayanna’s (and the family’s general) mood, the family began to work on solving problems together. Ayanna and her parents needed some help in selecting more easily solvable, less fraught problems at first. The therapist helped by focusing the family’s attention on simpler problems that involved everyone in the family (e.g., movie choice) to have success early on and make clear that everyone in the family was working to solve problems. The parents learned that trying to engage Ayanna in problem solving when Ayanna was already upset is ineffective. Instead, the family set up regular times to discuss and solve problems each week in addition to the weekly therapy sessions.

Final Phase of Treatment

Ayanna and her parents were consistently engaged throughout treatment, and though they had not solved all problems, the family was communicating better and was more optimistic about their ability to figure out solutions together. The final sessions focused on maintaining gains, anticipating potential challenges, and continuing to practice relevant skills, with the therapist becoming less and less active as the family used the skills more independently.

Empirical Support for FFT-CD

FFT-CD was developed through a three-stage process – from initial open trial pilot testing and treatment development, to a small RCT comparing it to waitlist, and, finally, to a larger RCT comparing it to another active depression-focused intervention. Our initial NIH-funded treatment development research integrated feedback from families to develop our handouts, to design and test our games and strategies to help families learn skills, and to hone the intervention model (Tompson et al., 2007). Through this early work, we learned a number of important lessons. First, families are busy and, even in 2-parent families, it is often not possible for both parents to attend. We are flexible in our approach, including sessions with parents separately, together and in other constellations. Second, and relatedly, we realized that, even when our focus was on the parents and the target child, we frequently had to include siblings. For families of target children with very young siblings, the inclusion of these siblings was often necessary logistically for families. For families of target children with school-aged siblings, sibling conflicts were frequently a source of downward spirals, and including those siblings in at least some sessions was helpful. Third, although medication may be a common and potentially necessary component of many interventions for both children (e.g., stimulant medications in ADHD) and adults (e.g., mood stabilizers in bipolar disorder) with a range of mental health problems, this is not necessarily the case in youth depression. Further, we found many parents wanted to avoid medications if possible. Thus, the FFT-CD approach does not assume medication is a regular part of treatment for all youth. Where medications are used for either the depression or associated problems, challenges around adherence can be addressed within this interpersonal framework and using problem-solving. Given positive findings in this trial, we commenced with a fully powered RCT.

We completed a two-site (Boston University and UCLA) randomized clinical trial to evaluate FFT-CD against individual therapy (IP). The IP model used a manualized supportive, client-centered approach (adapted from Cohen and Mannarino, 1996) and emphasized empathic listening, support, encouragement, and nondirective problem-solving. Youth ages 7–14 (n = 134) with diagnoses of Major Depressive Disorder, Dysthymic Disorder, or Depression Not Otherwise Specified were recruited through advertisements and outreach. To enhance generalizability, we included participants with comorbid anxiety and behavioral disorders. However, we excluded youth with thought or other disturbances that might interfere with treatment or assessment (e.g., psychotic disorder, autism spectrum disorder, severe OCD, active substance abuse/dependence, mental retardation) or a conduct disorder that might threaten stability of the home environment (e.g., recent arrests, juvenile justice and/or children’s protective service involvement). Table 2 provides demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample; there were no differences between the IP and FFT-CD groups on any of these variables at baseline.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the RCT Sample

| Total | FFT-CD | IP | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 134) | (N = 67) | (N = 67) | ||

| Child Age -- Mean (SD) | 10.84 (2.09) | 10.73 (2.10) | 10.96 (2.09) | .54 |

| Child Gender | .86 | |||

| Female | 75 (56%) | 37 (55%) | 38 (57%) | |

| Male | 59 (44%) | 30 (45%) | 29 (43%) | |

| Child Race/Ethnicity | .57 | |||

| Caucasian | 68 (51%) | 37 (55%) | 31 (46%) | |

| Latino/Hispanic | 20 (15%) | 10 (15%) | 10 (15%) | |

| African-American | 35 (26%) | 14 (21%) | 21 (31%) | |

| Other | 11 (8%) | 6 (9%) | 5 (8%) | |

| Family Composition | .31 | |||

| Two Parents | 80 (60%) | 43 (64%) | 37 (55%) | |

| One Parent/Guardian | 54 (40%) | 24 (36%) | 30 (45%) | |

| Family Income - Mean (SD) | 3.84 (1.31) | 3.95 (1.26) | 3.72 (1.36) | .31 |

| Child Depression Diagnosis | .71 | |||

| Major Depression | 89 (66%) | 43 (64%) | 46 (69%) | |

| Dysthymic Disorder | 24 (18%) | 12 (18%) | 12 (18%) | |

| Double Depression | 7 (5%) | 3 (4%) | 4 (5%) | |

| Depressive Disorder NOS | 14 (11%) | 9 (14%) | 5 (8%) | |

| Diagnostic Comorbidity | ||||

| Anxiety Disorders | 50 (37%) | 21 (31%) | 29 (43%) | .15 |

| Disruptive Behavior Disorder | 56 (42%) | 24 (36%) | 32 (48%) | .16 |

| Any Psychiatric Medication | 32 (24%) | 14 (21%) | 7 (26%) | .54 |

| Current Antidepressant | 15 (10%) | 6 (9%) | 9 (13%) | .41 |

Income ranges from 1 (< $14,000 annually) to 5 (> $75,000 annually).

Disruptive Behavior Disorder - Attention Deficit Hyperactivity, Oppositional Defiant and Conduct Disorders.

Following assessment with the KSADS-P and Child Depression Rating Scale – Revised (CDRS-R; Poznanski et al.,1985) to confirm diagnostic eligibility and assess symptom severity, youth were randomly assigned to FFT-CD or IP on a 1:1 ratio with stratification by site, gender, baseline depression diagnosis (MDD or DD vs. Depressive Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified), and the presence versus absence of antidepressant medication treatment. The same therapists conducted both the FFT-CD and the IP interventions at each site. This design has the advantage of controlling for therapist effects, whereby treatment group differences may be attributable to particularly strong therapist skills in one group. On the other hand, this design risks the possibility that treatment conditions will “bleed” into one another.

For our 2-site RCT, we developed rigorous training and quality assurance procedures to ensure fidelity of both interventions and closely monitor for and prevent bleeding across treatment conditions. Following separate 2-day trainings for each intervention, each session of the first two cases in each condition for each therapist was reviewed and weekly supervision provided in each model. Once therapists were certified, weekly supervision and periodic review of audio and/or video-recording continued. To assess fidelity three sessions were randomly chosen for each case (to represent early, middle and late sessions) and rated by two separate raters – one for adherence to FFT-CD and one for adherence to IP. Each of the adherence teams used assessment checklists that included both prescribed (e.g., discussing downward spirals in FFT-CD) and proscribed interventions (e.g., introducing a problem-solving model in IP) and made 7-point ratings for overall adherence and competence. As illustrated in Table 3, IP cases received high ratings for both IP adherence and competence and low ratings for FFT-CD adherence and competence; in contrast, FFT-CD cases received high ratings for FFT-CD adherence and competence and low ratings for IP adherence. Interestingly, FFT-CD cases received high ratings on IP competence. The IP competence questions were designed to assess therapist warmth and genuineness – something our therapist demonstrated regardless of treatment type. Thus, we were able to ensure a true separation of our treatments; our therapists were implementing each of the assigned interventions with fidelity. Thus, this approach provided a particularly rigorous comparison of these two conditions, controlling for therapist time and skill.

Table 3.

Fidelity to Treatment

| Type of Treatment | FFT-CD | IP |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| FFT-CD | ||

| Competence in FFT-CD | 6.43 (1.10) | 1.75 (1.26) |

| Adherence to FFT-CD | 6.34 (1.44) | 1.07 (0.26) |

| IP | ||

| Competence in IP | 6.95 (0.17) | 7.00 (0) |

| Adherence to IP | 1.03 (0.25) | 6.57 (1.38) |

Note: All scales were rated from (1) not at all competent/adherent to (7) extremely competent/adherent

Child participants underwent blind clinical and diagnostic assessment immediately post-treatment and at 4-month and 9-month follow-up points. Children and their parents also completed the Child Depression Inventory at all assessment points and at the 5th and 10th treatment sessions; additional information on study design and implementation can be found in our previous publications (Tompson, Sugar et al., 2017; Asarnow et al., in press). The primary outcome examined was adequate clinical depression response, defined as a decrease in the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R) of ≥50%, consistent with adolescent depression treatment trials (Lynch et al., 2011; Tompson et al., 2012); additionally, we examined clinical depression remission, defined as a post-treatment CDRS-R score ≤ 28, consistent with antidepressant treatment trials in youth (Bridge et al., 2007; Cipriani et al., 2016). We have included information on treatment completion in Table 4, which illustrates that the majority of participants (74%) completed 10 or more treatment sessions (an adequate dose), and there were no treatment group differences in either dropout or number of sessions attended. These rates are similar to those found in other RCTs of family-based treatments for youth with mood disorders (Dietz et al., 2015; Miklowitz et al., 2008). It should be noted that where possible we continued to follow-up all participants regardless of treatment dropout; in examining outcomes we reported results of both completer and intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses.

Table 4.

Treatment Completion/Attrition

| FFT-CD | IP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 67) | (n = 67) | |||

| N | % | N | % | |

| Completer (10–15 sessions) | 48 | 72 | 51 | 76 |

| Partial Completer (5–9 sessions) | 9 | 13 | 7 | 11 |

| Early Dropout (1–4 session) | 10 | 15 | 9 | 13 |

| Pretreatment dropout | 4 | 6 | 3 | 5 |

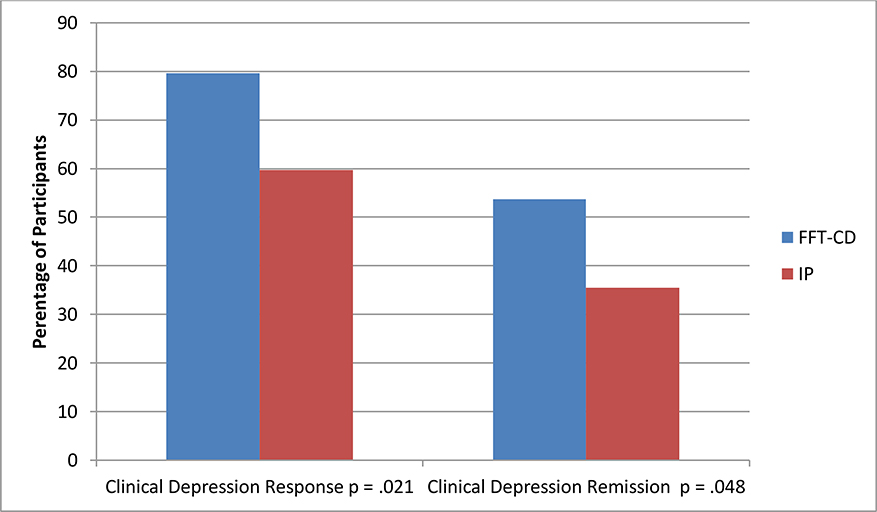

We examined both immediate post-treatment outcomes as well as longer term outcomes and response trajectories. As illustrated in Figure 2, children assigned to FFT-CD showed higher rates of adequate clinical depression response immediately post-treatment compared to those in IP (completer OR = 2.64, p = .02, 79.6% vs. 59.7%; ITT OR = 2.29, p = .05, estimated rates 77.7% vs. 59.9%). For clinical depression remission those assigned to FFT-CD showed higher rates in completer analyses (OR = 2.11, p = .05, 53.7% vs. 35.5%) and a trend toward higher rates in ITT analyses (OR = 1.84, p = .10, estimated rates 52.3% vs 37.3%). However, change in overall CDRS-R score did not differ between groups, as there was significant intragroup variability in degree of response. Analyses of age effects were consistent with our prediction that advantages of FFT-CD would be most evident for younger youths, aged 7–11 years. We found that youth aged 7–11 had an odds ratio for adequate depression clinical response of almost 3 to 1 favoring FFT-CD, a similar response rate to that found in the Dietz et al. study (2015) which included children ages 8–12. In contrast, the odds ratio for adequate depression clinical response among 12–14-year-olds in this study was roughly to 1:1 across treatment conditions. This suggests that FFT-CD may be most beneficial during the childhood years, supporting the developmental rationale for the treatment, but comparable to IP as youth enter adolescence. However, our study was underpowered to detect treatment group by age group interaction effects [dummy_incomplete para]

Figure 2.

Immediate Post-Treatment Outcomes Comparing Family-Focused Treatment for Depression in Childhood (FFT-CD) to Individual Psychotherapy (IP)

Note: Clinical Depression Response > or = 50% reduction on Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R); Clinical Depression Remission < or = 28 on CDRS-R.

After examining immediate post-treatment impacts, we conducted analyses to examine longer term effects and response trajectories, following children for 52-weeks, roughly 9 months after treatment completion (Asarnow et al., in press). We confirmed our previously reported findings of a significant FFT-CD advantage at the end of acute treatment using the longitudinal model. Further, having used a more intensive data collection schedule for child- and parent-reported depressive symptoms on the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI-C and CDI-P), we evaluated the trajectories for these measures from baseline to mid-treatment (weeks 5 and 10), post-treatment (week-16), and weeks 32 and 52. With this longitudinal model, having six time-points, there was a significant FFT-CD advantage on the CDI-C over the acute treatment period (p = .037), and an overall trend for differential trajectories across groups on child-reported depression (CDI-C, omnibus test: F (2,506) = 2.33, p =.098). In both groups there was significant initial improvement in symptoms, followed by a leveling off over the follow-up (all p’s < .0008). For the parent CDI-P, both treatment groups showed significant initial gains, followed by leveling off over the follow-up (p’s < .0001), with no evidence of differential treatment effects. These findings provide further support for an acute advantage for FFT-CD and are consistent with meta-analysis results indicating significant treatment benefits only for child-reported depression (Weisz et al., 2006). Parents and children tend to have only moderate agreement on symptoms of depression, and the agreed-upon symptoms are those that are generally more observable (De Los Reyes and Kazdin, 2005). The CDI-C may have been more sensitive to subtle, less-outwardly-observable changes best reported by youth.

Across diverse depression measures (CDRS response, total score, remission), we observed a consistent pattern of greater improvement in depression levels among youths receiving FFT-CD at the post-treatment point. However, over the follow-up period (post-treatment assessment through week-52), children assigned to IP continued to gradually improve and those assigned to FFT-CD leveled out. Indeed, most children recovered from their depressive episodes by week-52 (roughly 12-months): 77% in FFT-CD; 78% IP. However, recurrent episodes also emerged. One FFT-CD and 6 IP children suffered recurrent episodes yielding estimated recurrence rates of 3% and 14% respectively. Results of survival analyses examining time to recurrence among children who recovered indicate a trend towards an FFT-CD advantage in preventing recurrence, Wilcoxon χ2 (1) =3.34, p = .068.

We also examined suicidal behavior, self-harm, mental-health-related emergency department (ED) visits, and psychiatric hospitalizations (Asarnow et al., in press). Suicidal behavior: Over the course of the trial, four children made five suicide attempts (1 hanging, 2 overdoses, 1 cutting, 1 method unknown), and all were children assigned to IP (one during treatment and four during weeks 16–52). Non-suicidal self-injury: NSSI was reported in 15 children, including 7 FFT-CD (6 children for 15 episodes during treatment, 1 child for 1 episode during weeks 16–52) and 8 IP (6 children for 12 episodes during treatment; 5 children for 9 episodes during weeks 16–52). Mental health-related ED visits were similar across treatment arms, including 4 FFT-CD children with 7 total ED visits (2 children with 3 total visits during treatment, 2 children with 4 total visits weeks 16–52) and 4 IP children with 5 total ED visits (2 children, 2 total visits, during treatment-period; 2 children with 3 total visits weeks 16–52). Mental health-related hospitalizations were uncommon in both groups, including 3 FFT-CD children with 5 total hospitalizations (2 children with 2 total hospitalizations during treatment; 1 child with 3 total hospitalizations during weeks 16–52) and 2 IP children with 2 total hospitalizations (1 during treatment, 1 during weeks 16–52).

Limitations

First, given that FFT-CD and IP differed both in format (family versus individual) and content (skill building versus supportive), it is not possible to determine whether the format, the content or the interaction of the two might be responsible for outcome differences. Additional studies comparing FFT-CD to individual CBT may be able to answer this question. Second, we are not able to determine the role of homework completion in determining outcomes, as homework was only included in the FFT-CD condition. Third, although we see some initial evidence of longer-term protective effects for FFT-CD compared to IP, we do not have additional follow-up data to evaluate these effects beyond one-year post-baseline. Finally, FFT-CD would benefit from greater evaluation in community settings.

Conclusions

Our results support the value of a family-focused treatment approach for children suffering from depressive disorders. Even with a rigorous comparison group and the same therapists delivering both treatment conditions, we observed an FFT-CD advantage at the post-treatment point and a suggestion of protection from depression recurrence and suicide attempts over 52 weeks of follow-up, compared to IP.

Similar to other depression treatment RCTs in children and adolescents, differential treatment effects faded over the 52 weeks of follow-up as children returned to usual treatment services and most depressions recovered with time (77–78%). These results underscore the importance of examining trajectories over time. Had we focused only on the acute period, we would have missed that the initial FFT-CD advantage did not last; and focusing only on the final 52-week outcome point, we would have missed the earlier FFT-CD benefits. Examining trajectories over the full follow-up period allowed us to see differences in pathways to recovery and longer-term outcomes in the two treatment conditions. Information regarding change trajectories across different treatment strategies can help us to move towards an evidence-based approach to the timing of treatments and optimal care strategies during acute and post-acute treatment periods. This is particularly important given observations from the largest longitudinal evaluation of depression in childhood which indicated that up to 72% of children who recovered from their first major depressive episodes suffered recurrent episodes (median between-episode interval 3–5 years; Kovacs et al., 2016).

The natural tendency towards depression recovery over time, personal and economic costs of mental health treatment, a desire on the part of many children and parents to move beyond the mental health problems, and constraints of health and mental health care systems, have contributed to a tendency to emphasize effective, acute treatment. However, our results and those of others underscore the need to adopt longer-term care models that attend to post-acute and continuing care to prevent recurrent depressions and other adverse outcomes associated with childhood-onset depression such as suicide attempts, deaths, and other self-harm tendencies (Kovacs et al., 2016).

Although we were not powered to examine formally the effect of treatment on suicide attempts, we did see fewer suicide attempts in the FFT-CD condition. This is consistent with our hypothesis that a family-focused approach mobilizes protective strengths. This observation is also consistent with accumulating research showing benefits of treatments with strong family components for reducing the risk of suicide attempts (Asarnow et al., 2017; Ougrin et al., 2015; McCauley et al., 2018; Glenn et al., 2019).

Although youths receiving FFT-CD had a quicker response to treatment, most children in FFT-CD and IP recovered. However, with time and as expected, recurrent episodes emerged, potentially contributing to the long-term adverse impact depressive disorders have for many children with depression (Weissman et al., 1999). The challenge ahead is to develop the science to optimize clinical decision-making, personalize our approach such that individual children are matched to the treatment approach that is most likely to be beneficial, and clarify the treatment mechanisms that will enable improved treatments. Given the potential long-term course of childhood depression and the relevance of family members in the course and treatment of childhood depression, family involvement in treatment planning to personalize treatment based on child and family needs, preferences, and values may be especially important (Langer and Jensen-Doss, 2018). Additionally, pediatric patient-centered medical homes hold promise for detecting youth with mental health needs such as depression, improving access to treatment and serving as a setting to assess for continuing treatment needs following treatment (Asarnow et al., 2017).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Family-Focused Treatment for Childhood Depression is an evidence-based, developmentally adapted intervention for the treatment of depressed youth ages 7–14.

Family-Focused Treatment for Childhood Depression is based on an interpersonal model that utilizes the idea of upward and downward interactional spirals in which family interactions impact mood and vice versa.

Using an interpersonal framework, Family-Focused Treatment for Childhood Depression assists families in developing skills to improve their interpersonal functioning, built resilience and combat depression.

Compared to individual supportive therapy, Family-Focused Treatment for Childhood Depression has demonstrated quicker recovery from depression.

Acknowledgements:

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants MH60378, MH082856 (M.C. Tompson, PI), MH082861 (J.R. Asarnow, PI), and MH101238 (D.A. Langer, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr. Tompson has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, honoraria for work as Associate Editor for Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, and royalties from BVT Publishing and Guilford Press. Dr. Langer has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health. Dr Asarnow has received grant support from the National Institute of Mental Health, U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, and the American Psychological Foundation. Dr. Asarnow also reported receiving support from the Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, and consulting on quality improvement interventions for depression and suicidal/self-harm behavior. She is on the Scientific Council for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and Scientific Advisory Board for the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Martha C. Tompson, Boston University, Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences, Boston, MA.

David A. Langer, Suffolk University, Department of Psychology, Boston, MA

Joan R. Asarnow, UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Los Angeles, CA

References

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth ed. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Hughes JL, Babeva KN, Sugar CA, 2017. Cognitive-behavioral family treatment for suicide attempt prevention: a randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Psy 56, 506–514. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Kolko DJ, Miranda J, Kazak AE, 2017. The pediatric patient-centered medical home: innovative models for improving behavioral health. Am. Psychol 72, 13–27. 10.1037/a0040411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Scott CV, Mintz J, 2002. A combined cognitive-behavioral family education intervention for depression in children: a treatment development study. Cognitive Ther. Res 26, 221–229. 10.1023/A:1014573803928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Tompson MC, Klomhaus AM, Babeva K, Langer DA, Sugar CA, 2019. Randomized controlled trial of family-focused treatment for child depression compared to individual psychotherapy: one-year outcomes. J. Child. Psychol. Psyc In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Knight E, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, 2008. Epidemiology of depression in children and adolescents, in: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL (Eds.), Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. The Guilford Press, New York, pp. 6–32. [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Arbelaez C, Brent D, 2002. Course and outcome of child and adolescent major depressive disorder. Child Adol. Psych. Cl 11, 619–638. 10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Williamson DE, Dahl RE, Axelson DA, Kaufman J, Dorn LD, Ryan ND, 2004. Clinical presentation and course of depression in youth: does onset in childhood differ from onset in adolescence? J. Am. Acad. Child Psy 43, 63–70. 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, Barbe RP, Birmaher B, Pincus HA, Ren L, Brent DA, 2007. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials. J. Amer. Med. Assoc 297, 1683–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell DP, Carlson G, 1979. Problems and prospects in the study of childhood depression. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 167, 522–529. 10.1097/00005053-197909000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD, 1998. Defining empirically supported therapies. J. Consult. Clin. Psych 66, 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani A, Zhou X, Del Giovane C, Hetrick SE, Qin B, Whittington C, Coghill D, Zhang Y, Hazell P, Leucht S, Cuijpers P, Pu J, Cohen D, Ravindran AV, Liu Y, Michael KD, Yang L, Liu L, Xie P, 2016. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 388, 881–890. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Mannarino AP, 1996. Child-centered therapy treatment manual MCP Hahnemann University School of Medicine, Pittsburgh. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE, 2005. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol. Bull 131, 483–509. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz LJ, Weinberg RJ, Brent DA, Mufson L, 2015. Family-based interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed preadolescents: examining efficacy and potential treatment mechanisms. J. Am. Acad. Child Psy 54, 191–199. 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Verducci JS, Walters K, Young ME, 2009. Impact of multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy in treating children aged 8 to 12 years with mood disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiat 66, 1013–1020. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Esposito EC, Porter AC, Robinson DJ, 2019. Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. J. Clin. Child Adolesc 48, 357–392. 10.1080/15374416.2019.1591281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Burge D, Adrian C, 1991. Timing of mother and child depression in a longitudinal study of children at risk. J. Consult. Clin. Psych 59, 341–345. 10.1037/0022-006X.59.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Shih J, 2014. Depression and interpersonal processes, in: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL (Eds.), Handbook of depression. Guilford Press, New York, pp. 277–295. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abela JRZ (Eds.), 2005. Development of psychopathology: a vulnerability-stress perspective Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Fombonne E, Poulton R, Martin J, 2002. Differences in early childhood risk factors for juvenile-onset and adult-onset depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiat 59, 215–222. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Coyne JC (Eds.), 1999. The Interactional Nature of Depression: Advances in Interpersonal Approaches American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS, 2003. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). J. Amer. Med. Assoc 289, 3095–3105. 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, 1996. Presentation and course of major depressive disorder during childhood and later years of the life span. J. Am. Acad. Child Psy 35, 705–715. 10.1097/00004583-199606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Obrosky S, George C, 2016. The course of major depressive disorder from childhood to young adulthood: recovery and recurrence in a longitudinal observational study. J. Affect. Disorders 203, 374–381. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, 1999. Peer relationships and social competence during early and middle childhood. Annu. Rev. Psychol 50, 333–359. 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer DA, Jensen-Doss A, 2018. Shared Decision-Making in youth mental health care: using the evidence to plan treatments collaboratively. J. Clin. Child Adolesc 47, 821–831. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F15374416.2016.1247358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P, 1994. Major depression in community adolescents: age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. J. Am. Acad. Child Psy 33, 809–818. 10.1097/00004583-199407000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch FL, Dickerson JF, Clarke G, Vitiello B, Porta G, Wagner KD, Emslie G, Asarnow JR, Keller MB, Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Kennard B, Mayes T, DeBar L, McCracken JT, Strober M, Suddath RL, Spirito A, Onorato M, Zelazny J, Iyengar S, Brent D, 2011. Incremental cost-effectiveness of combined therapy vs medication only for youth with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor–resistant depression: treatment of SSRI-resistant depression in adolescents trial findings. Arch Gen Psychiat 68, 253–262. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan B, Collishaw S, Stringaris A, 2013. Depression in childhood and adolescence. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 22, 35–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley E, Berk MS, Asarnow JR, Adrian M, Cohen J, Korslund K, Avina C, Hughes J, Harned M, Gallop R, Linehan MM, 2018. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide: a randomized clinical trial. J. Amer. Med. Assoc 75, 777–785. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Zhang H, Avenevoli S, Acharyya S, Neuenschwander M, Angst J, 2003. Longitudinal trajectories of depression and anxiety in a prospective community study. Arch. Gen. Psychiat 60, 993–1000. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, George EL, Taylor DO, Schneck CD, Beresford CA, Dickinson LM, Craighead WE, Brent DA, 2008. Family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar disorder: results of a 2-year randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiat 65, 1053–61. 10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Depression, Parenting Practices, and the Healthy Development of Children; England MJ, Sim LJ (Eds.), 2009. Depression in parents, parenting, and children: opportunities to improve identification, treatment, and prevention National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, Asarnow JR, 2015. Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Psy 54, 97–107. 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski E, Hartmut MB, Grossman J, Freeman LN, 1985. Diagnostic criteria in childhood depression. Am. J. Psychiat 142, 1168–1173. 10.1176/ajp.142.10.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J, Lukens E, Davies M, Goetz D, Brennan-Quattrock J, Todak G, 1985. Psychosocial functioning in prepubertal major depressive disorders: I. interpersonal relationships during the depressive episode. Arch. Gen. Psychiat 42, 500–507. 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790280082008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M, Abaied JL, 2008. A developmental perspective on interpersonal theories of youth depression, in: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL (Eds.), Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. Guilford Press, New York, pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D, Lindberg N, Herzberg D, Daley SE, 2000. Toward an interpersonal life-stress model of depression: the developmental context of stress generation. Dev. Psychopathol 12, 215–234. 10.1017/S0954579400002066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Prinstein MJ, 2014. Evidence base updates: the evolution of the evaluation of psychological treatments for children and adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc 43, 1–6. 10.1080/15374416.2013.855128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, 2001. We know some things: parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. J. Res. Adolescence 11, 1–9. 10.1111/1532-7795.00001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tompson MC, Asarnow JR, Mintz J, Cantwell DP, 2015. Parental depression risk: comparing youth with depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and community controls. J. Psychol. Psychother 5, 1–9. 10.4172/2161-0487.1000193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tompson MC, Boger KD, Asarnow JR, 2012. Enhancing the developmental appropriateness of treatment for depression in youth: integrating the family in treatment. Child Psychiatr. Clin. North Am 21, 345–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompson MC, Langer DA, Hughes JL, Asarnow JR, 2017. Family-focused treatment for childhood depression: model and case illustrations. Cogn. Behav. Pract 24, 269–287. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompson MC, Pierre CB, Haber FM, Fogler JM, Groff AR, Asarnow JR, 2007. Family-focused treatment for childhood-onset depressive disorders: results of an open trial. Clin. Child Psychol. P 12, 403–420. 10.1177/1359104507078474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompson MC, Sugar CA, Langer DA, Asarnow JR, 2017. A randomized clinical trial comparing family-focused treatment and individual supportive therapy for depression in childhood and early adolescence. J. Am. Acad. Child Psy 56, 515–523. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowell J, Joffe I, Campbell J, Clemente C, Almqvist F, Soininen M, Koskenranta-Aalto U, Weintraub S, Kolaitis G, Tomaras V, Anastasopoulos D, Grayson K, Barnes J, Tsiantis J, 2007. Childhood depression: a place for psychotherapy. An outcome study comparing individual psychodynamic psychotherapy and family therapy. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 16, 157–167. 10.1007/s00787-006-0584-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weersing VR, Jeffreys M, Do MT, Schwartz KT, Bolano C, 2017. Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. J. Clin. Child Adolesc 46, 11–43. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1220310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wolk S, Goldstein RB, Moreau D, Adams P, Greenwald S, Klier CM, Ryan ND, Dahl RE, Wickramaratne P, 1999. Depressed adolescents grown up. J. Amer. Med. Assoc 281, 1707–1713. 10.1001/jama.281.18.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SM, 2006. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull 132, 132–149. 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Southam-Gerow MA, Gordis EB, Connor-Smith JK, Chu BC, Langer DA, McLeod BD, Jenson-Doss A, Updegraff A, Weiss B, 2009. Cognitive–behavioral therapy versus usual clinical care for youth depression: an initial test of transportability to community clinics and clinicians. J. Consult. Clin. Psych 77, 383–396. 10.1037/a0013877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.