Abstract

Cell death is intrinsically linked with immunity. Disruption of an immune-activated MAPK cascade, consisting of MEKK1, MKK1/2, and MPK4, triggers cell death and autoimmunity through the nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) protein SUMM2 and the MAPK kinase kinase MEKK2. In this study, we identify a Catharanthus roseus receptor-like kinase 1-like (CrRLK1L), named LETUM2/MEDOS1 (LET2/MDS1), and the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein LLG1 as regulators of mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death. LET2/MDS1 functions additively with LET1, another CrRLK1L, and acts genetically downstream of MEKK2 in regulating SUMM2 activation. LET2/MDS1 complexes with LET1 and promotes LET1 phosphorylation, revealing an intertwined regulation between different CrRLK1Ls. LLG1 interacts with the ectodomain of LET1/2 and mediates LET1/2 transport to the plasma membrane, corroborating its function as a co-receptor of LET1/2 in the mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death pathway. Thus, our data suggest that a trimeric complex consisting of two CrRLK1Ls LET1, LET2/MDS1, and a GPI-anchored protein LLG1 that regulates the activation of NLR SUMM2 for initiating cell death and autoimmunity.

Subject terms: Plant genetics, Plant immunity, Plant molecular biology, Plant physiology, Plant signalling

MAPK signaling suppresses autoimmunity mediated by the SUMM2 receptor in Arabidopsis. Here Huang et al. show that a trimeric complex consisting of the GPI anchored protein LLG1, and the two receptor-like proteins LET1 and LET2, promotes activation of SUMM2 according to MAPK signaling status.

Introduction

Being sessile and lacking the adaptive immunity, plants have evolved two-tiered immune receptors to detect infections. The plasma membrane-associated immune receptors, termed pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), sense pathogen- or microbe-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs or MAMPs), or host-derived danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that trigger immune responses against a broad spectrum of pathogens, including non-adapted pathogens1–3. PRRs are often receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and receptor-like proteins (RLPs) in plants4,5. The intracellular immune receptors, which are often nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat proteins (NLRs), recognize directly or indirectly pathogen-delivered effectors and trigger race-specific resistance against adapted pathogens carrying the cognate effectors6–8. The NLR-mediated immune response is usually associated with a rapid and localized cell death at the infection site, known as the hypersensitive response (HR), to restrict pathogen spread.

Plants have evolved a largely expanded number of RLKs9. The most well-studied RLKs contain an extracellular leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain, called LRR-RLKs, which play important roles not only in regulating plant immunity by sensing MAMPs/DAMPs, but also in modulating plant growth and development by perceiving endogenous signals or environmental cues10,11. RLKs with an extracellular malectin-like domain, also called Catharanthus roseus RLK1-like kinases (CrRLK1Ls), have long been known to be key regulators in various developmental processes including cell elongation, polarized growth, and fertilization12–15. Among 17 members in Arabidopsis, FERONIA (FER) is involved in a myriad of biological processes including fertilization, root hair growth, plant hormone signaling, and immunity16–18. ANXUR1 (ANX1) and ANX2, close homologs of FER, play redundant roles in cell wall integrity during pollen tube growth19–21. BUDDHA’S PAPER SEAL 1 (BUPS1) and BUPS2 interact with ANX1/ANX2 in maintaining pollen tube integrity22,23. In addition, both FER and ANXs are involved in plant immunity24–27. FER scaffolds MAMP-induced PRR complex formation24 and suppresses jasmonic acid hormone signaling in plant immunity26. However, ANX1 and ANX2 negatively regulate two-tiered plant immunity by modulating both PRRs and NLRs25. The glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein LORELEI (LRE) and LRE-like proteins LLGs function as co-receptors/adapters for FER in regulating plant growth, reproduction and immunity28,29. Recently, it has been shown that LLG2/LLG3 are co-receptors of BUPSs/ANXs in regulating pollen tube integrity30,31. Interestingly, LLG1 is also involved in plant immunity by association and modulation of PRR FLS232.

Although the recognition of pathogens by the innate immune system differs, common responses and signaling components converge at multiple levels1,2,6. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK or MAP kinase) cascades are among essential modules regulating both PRR and NLR-mediated immune responses in plants33–35. The classical MAPK cascade consists of three sequentially phosphorylated kinases, including MAPK kinase kinases (MAPKKKs, MKKKs, or MEKKs), MAPK kinases (MAPKKs, or MKKs), and MAPKs (MPKs)36. Two parallel MAPK cascades, MKKK3/5-MKK4/5-MPK3/6 and MEKK1-MKK1/2-MPK4, play important roles in PRR signaling37–39. Plants with deficiency in MEKK1, MKK1/2 or MPK4 display autoimmune phenotypes and are seedling lethal40–44. The autoimmunity in mekk1, mkk1/2, and mpk4 mutants is due to the activation of the NLR protein SUPPRESSOR OF mkk1 mkk2 (SUMM2)-mediated defense45. Intriguingly, the MEKK1-MKK1/2-MPK4 cascade negatively regulates another MAPKKK MEKK2, which interacts with MPK4, and positively regulates the NLR SUMM2-triggered autoimmunity46,47. Furthermore, the transcript and protein abundance of MEKK2 is positively correlated with its ability to trigger autoimmunity47. Another kinase, CALMODULIN-BINDING RECEPTOR-LIKE CYTOPLASMIC KINASE 3 (CRCK3), which is phosphorylated by MPK4, is also required for SUMM2-activated autoimmunity48. Apparently, a PRR-activated MAPK cascade, consisting of MEKK1-MKK1/2-MPK4, functions genetically upstream of SUMM2 in regulating autoimmunity.

To gain insights into the mechanisms underlying SUMM2-mediated defense, which is otherwise suppressed by a PRR-activated MAPK cascade, we deployed a transient RNAi-based genetic screen by virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) and screened for suppressors of mekk1 cell death from a collection of T-DNA insertion mutants. We identified lethality suppressor of mekk1 1 (letum1 or let1) that largely suppressed the autoimmunity in mekk1, mkk1/2, and mpk4. LET1 is a member of uncharacterized CrRLK1Ls49. In this study, we have screened additional CrRLK1Ls and identified LET2/MEDOS1 (MDS1) in regulating mekk1, mkk1/2, and mpk4 autoimmunity. Both let1 and let2 single mutants suppressed mekk1, mkk1/2, and mpk4 cell death, however, the let1let2 (called let1/2 henceforth) double mutant showed further suppression, indicating the additive function of LET1 and LET2/MDS1 in modulating SUMM2 activation. Interestingly, LET1 and LET2/MDS1 heteromerize, and LET2/MDS1 promotes LET1 phosphorylation, suggesting a phosphoregulation between different CrRLK1Ls. Similar to LET1 and LET2/MDS1, the GPI-anchored protein LLG1, but not LLG2, LLG3, nor LRE, plays a role in modulating mekk1, mkk1/2, and mpk4 cell death, and functions genetically downstream of MEKK2 and upstream of SUMM2. Likely as a co-receptor, LLG1 interacts with the ectodomain of LET1 and likely LET2/MDS1 and mediates LET1/2 transport to the plasma membrane. Thus, our results suggest that a specific trimeric CrRLK1L module consisting of LET1, LET2/MDS1, and the GPI-anchored LLG1 modulates SUMM2-mediated autoimmunity.

Results

The mutations in the CrRLK1L gene, LET2/MDS1, suppress RNAi-MEKK1 cell death

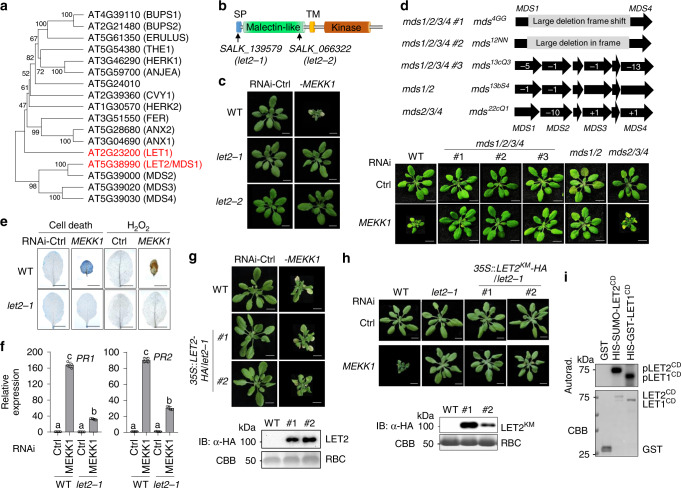

There are 17 CrRLK1L genes in the Arabidopsis genome (Fig. 1a). Among them, LET1 (AT2G23200) was identified as a modulator of autoimmunity in mekk1, mkk1/2, and mpk449. To systematically investigate the CrRLK1L gene family members in this process, we collected the T-DNA insertion lines of individual CrRLK1L genes and determined their roles on silencing MEKK1-triggered cell death through a VIGS approach (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Among 20 T-DNA insertion lines, including the herk1-1the1-4 double mutant, five lines of three genes, AT5G24010 (two lines), AT4G39110 (BUPS1, two lines), and AT2G21480 (BUPS2, one line), do not bear T-DNA insertions in the annotated sites and were characterized as wild type (WT; Supplementary Fig. 1a). It has been shown that the bups mutants have defects in pollen tube growth22. The remaining 15 T-DNA insertion lines are homozygous mutants (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Among them, two mutants, SALK_139579 and SALK_066322, but not the other 13 mutants of 12 CrRLK1Ls, suppressed the growth defects and cell death caused by RNAi-MEKK1 (Fig. 1b, c and Supplementary Fig. 1b). SALK_139579 bears a T-DNA insertion in the signal peptide (SP) motif, and SALK_066322 has a T-DNA insertion in the malectin-like domain of AT5G38990, respectively (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Since they suppressed RNAi-MEKK1-mediated cell death, AT5G38990 was named as LET2, and the corresponding mutants SALK_139579 and SALK_066322 were named as let2-1 and let2-2.

Fig. 1. LET2/MDS1 is involved in RNAi-MEKK1 cell death.

a A phylogenetic tree of CrRLK1L family proteins. The full-length protein sequences were used to generate the phylogenetic tree by the UPGMA method with 1000 bootstrap replicates in MEGA-X. b A schematics depicting LET2/MDS1 protein motifs and T-DNA insertion sites in the let2 mutants. LET2/MDS1 consists of the N-terminal signal peptide (SP), a malectin-like domain, a transmembrane domain (TM), and a cytosolic kinase domain. The arrows indicate the T-DNA insertion sites of the indicated mutant alleles. c The let2 mutants suppress plant dwarfism and leaf chlorosis induced by silencing MEKK1. The plant images were photographed at 3 weeks after inoculation with Agrobacterium carrying the indicated VIGS vectors. Ctrl is the vector containing GFP. Scale bar, 1 cm. d The LET2/MDS1, but not MDS2, MDS3, nor MDS4,is involved in RNAi-MEKK1 cell death. The mds1/2/3/4, mds1/2, and mds2/3/4 CRISPR/Cas knockout plants were inoculated with Agrobacterium carrying the indicated VIGS vectors. The plant images were photographed at 3 weeks after inoculation. The chromosome locations and Indels of MDS1, MDS2, MDS3, and MDS4 on individual mutants are shown on the top. Scale bar, 1 cm. e The let2-1 mutant suppresses cell death and H2O2 accumulation triggered by silencing MEKK1. The leaves were detached from plants in c and stained by trypan blue for cell death (left panel) and DAB for H2O2 accumulation (right panel). Scale bar, 0.5 cm. f The let2-1 mutant suppresses the expression of PR genes triggered by silencing MEKK1. The expression of PR1 and PR2 from plants in c was normalized to the expression of UBQ10 and the data are shown as the mean ± SE of four biological repeats (n = 4). P = 3.00 × 10−14 (PR1, column 1 and 2), P = 1.60 × 10−7 (PR1, column 3 and 4), P = 4.40 × 10−14 (PR1, column 2 and 4), P = 3.00 × 10−14 (PR2, column 1 and 2), P = 3.45 × 10−11 (PR2, column 3 and 4), and P = 5.10 × 10−14 (PR2, column 2 and 4). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). g Expression of LET2/MDS1 in let2-1 restores the cell death triggered by silencing MEKK1. The plant images were taken at 3 weeks after inoculation with Agrobacterium carrying the indicated VIGS vectors. #1 and #2 are two independent 35 S::LET2-HA transgenic lines in let2-1. Scale bar, 1 cm. Protein expression of LET2-HA in transgenic lines is shown on the bottom. The total proteins were immunoblotted by an α-HA antibody (upper panel). Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining of RuBisCO (RBC) is shown as a loading control (lower panel). The molecular weight (MW) was labeled on the left of immunoblots as kDa. h The LET2/MDS1 kinase mutant cannot complement let2-1. Two lines of transgenic plants carrying the kinase-inactive mutant of LET2KM (K554E) driven by a 35S promoter in let2-1 are shown. Scale bar, 1 cm. Protein expression of LET2KM-HA in transgenic lines is shown on the bottom. i LET2/MDS1 bears kinase activity in vitro. GST and the LET2/MDS1 cytosolic kinase domain (HIS-SUMO-LET2CD) proteins were purified from E. coli. The LET1 cytosolic kinase domain (HIS-GST-LET1CD) proteins were purified from insect cells. The kinase assay was performed with [γ-32P] ATP. CBB staining was used as a loading control. The above experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

LET2 has been previously named as MEDOS1 (MDS1) and is involved in growth responses to metal ions50. Notably, LET2/MDS1 belongs to the MDS1-4 subfamily which resides in a tandem repeat region with three additional CrRLK1Ls, MDS2, MDS3, and MDS4 (Fig. 1a, d). MDS3 and MDS4 genes have redundant function in plant growth adaptation upon exposure to excess nickel ions50. We tested whether MDS genes also have redundant function in regulating RNAi-MEKK1 cell death with the CRISPR/Cas9-generated double, triple, and quadruple mds mutants50. The mds1/2/3/4 mutants #1 (mds4GG) and #2 (mds12NN) contain large deletions from MDS1 to MDS4; the mds1/2/3/4 #3 (mds13cQ3) contains deletions in four individual MDS genes; the mds2/3/4 mutant (mds22cQ1) has Indels in MDS2, MDS3, and MDS4; and the mds1/2 mutant (mds13bS4) has deletions in MDS1 and MDS2 (Fig. 1d)50. The individual mutants of mds2, mds3, and mds4 did not affect RNAi-MEKK1 cell death (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Consistent with the role of LET2/MDS1 in MEKK1 cell death regulation, the mds1/2/3/4 (#1, #2, #3), and mds1/2 mutants, but not the mds2/3/4 mutant, largely suppressed RNAi-MEKK1 cell death (Fig. 1d). Thus, the data support that LET2/MDS1 is a major CrRLK1L gene involved in the modulation of mekk1 cell death.

The let2-1 mutant suppressed RNAi-MEKK1 cell death detected by trypan blue staining and H2O2 accumulation by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining compared to WT plants (Fig. 1e). The let2-1 mutant also suppressed the constitutive activation of defense marker genes, including pathogenesis-related 1 (PR1) and PR2, caused by silencing MEKK1 (Fig. 1f). To confirm that the causal mutation in let2 is AT5G38990, we transformed the full-length cDNA of AT5G38990 under the control of a 35S promoter tagged with a double HA epitope at the carboxyl (C)-terminus (35S::LET2-HA) into the let2-1 mutant. The 35S::LET2-HA transgenic plants restored the RNAi-MEKK1 cell death in let2-1 (Fig. 1g). To determine whether the kinase activity of LET2/MDS1 is required for its function in the mekk1 cell death pathway, we mutated a conserved lysine residue in the ATP-binding loop of LET2/MDS1 to glutamic acid (K554E, LET2 kinase-inactive mutant LET2KM) and generated transgenic lines expressing LET2KM in let2-1. Unlike 35S::LET2-HA/let2-1, the 35S::LET2KM-HA/let2-1 transgenic plants did not restore the cell death caused by silencing MEKK1 (Fig. 1h), suggesting that its kinase activity is required for LET2/MDS1 function in mekk1 cell death regulation. Consistently, the LET2/MDS1 cytosolic domain (CD) consisting of the juxtamembrane and kinase domains fused with HIS-tagged SUMO enzyme target peptide (HIS-SUMO-LET2CD) displayed autophosphorylation activity in an in vitro kinase assay, similar with HIS-GST-LET1CD, suggesting that LET2/MDS1 is an active kinase (Fig. 1i).

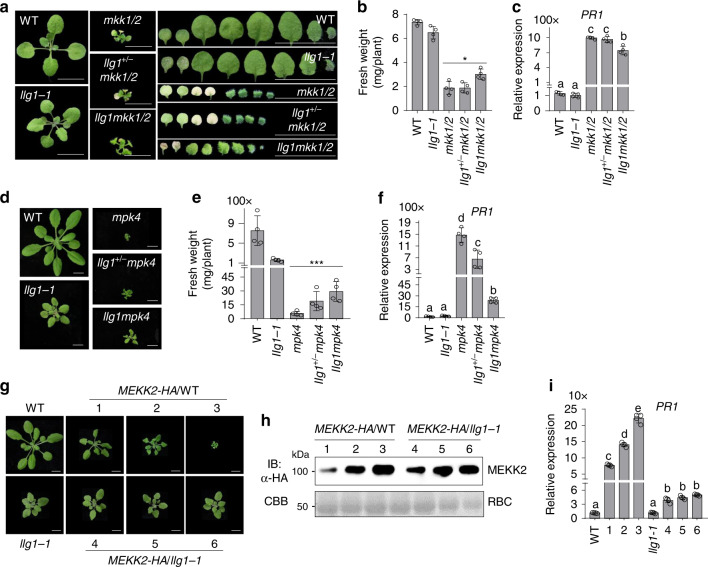

LET1 and LET2/MDS1 function additively in modulating mekk1, mkk1/2, and mpk4 cell death

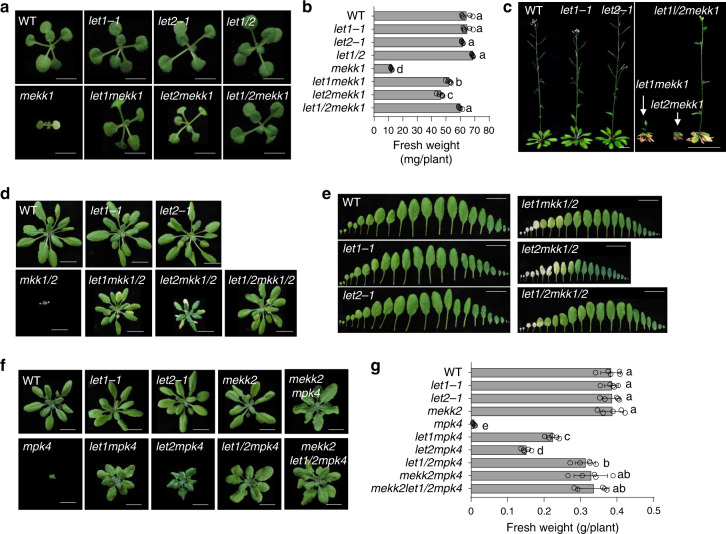

To genetically confirm the function of LET2/MDS1 in mekk1 cell death, we generated the let2mekk1 double mutant by crossing the let2-1 and mekk1+/- (mekk1 is heterozygous) mutants. The let2mekk1 double mutant significantly alleviated the growth defects and dwarfism of mekk1 when grown on ½MS plates (Fig. 2a, b). Since the let1mekk1 double mutant also suppressed the growth defects of mekk149, we compared the phenotype of let2mekk1 and let1mekk1. The let2mekk1 mutant was slightly smaller than let1mekk1 at 2-week-old stage (Fig. 2a, b). At the reproductive stage when grown on soil, the let2mekk1 mutant is obviously smaller than let1mekk1, displaying stronger cell death and failing to bolt (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, the let1/2mekk1 triple mutant grew bigger and had more fresh weight than the let1mekk1 and let2mekk1 mutants at both seedling (Fig. 2a, b) and the reproductive (Fig. 2c) stages. The let1/2mekk1 mutant normally bolted and produced seeds (Fig. 2c). These data indicate that let2 suppresses cell death caused by either silencing or mutation of MEKK1, and LET1 and LET2/MDS1 function additively in modulating mekk1 cell death.

Fig. 2. LET1 and LET2/MDS1 function additively in regulating mekk1, mkk1/2, and mpk4 cell death.

a–c LET1 and LET2/MDS1 function additively in regulating mekk1 cell death. a Two-week-old plants of different genotypes grown on ½MS plates are shown. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. b The fresh weight of the indicated plants in a. The data are shown as the mean ± SE (n = 5). P = 1.00 × 10−13 (column 5 and 6), P = 1.00 × 10−13 (column 5 and 7), P = 1.00 × 10−13 (column 5 and 8), P = 1.53 × 10−5 (column 6 and 8), and P = 5.71 × 10−11 (column 7 and 8). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). c Six-week-old soil-grown plants are shown. Scale bar, 1 cm (left panel) and 2 cm (right panel). d, e LET1 and LET2/MDS1 function additively in regulating mkk1/2 cell death. Four-week-old soil-grown plants (d) and leaves (e) are shown. Scale bar, 1 cm. The leaves from the individual plants were placed with the order of age (from oldest to youngest). f, g LET1 and LET2/MDS1 function additively in regulating mpk4 cell death. Four-week-old soil-grown plants (f) and their fresh weight (g) are shown. Scale bar, 1 cm. The data are shown as the mean ± SE (n = 5) with one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). P = 7.72 × 10−13 (column 5 and 6), P = 3.51 × 10−8 (column 5 and 7), P = 4.71 × 10−13 (column 5 and 8), P = 4.71 × 10−13 (column 5 and 9), and P = 4.71 × 10−13 (column 5 and 10). The above experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

The MEKK1 pathway is mediated through MKK1/2 and MPK4. Similar as mekk1, the mkk1/2 double mutant and the mpk4 mutant are seedling lethal43,44. We tested whether the let2 mutant interferes with mkk1/2 and mpk4 cell death by generating the let2mkk1/2 triple mutant, and the let2mpk4 double mutant. The let2mkk1/2 mutant largely alleviated mkk1/2 cell death (Fig. 2d, e). The let1/2mkk1/2 quadruple mutant grew better than let2mkk1/2 and let1mkk1/2 triple mutants, with fewer dead leaves at the 4-week-old stage (Fig. 2d, e). In addition, the let2mpk4 double mutant suppressed mpk4 cell death (Fig. 2f, g). The data indicate that LET2/MDS1 functions genetically downstream of MPK4 in the mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death pathway. The let2mpk4, let1mpk4, and let1/2mpk4 mutants were in the ascending order of plant size and fresh weight (Fig. 2f, g), corroborating the notion that LET2/MDS1 acts additively with LET1 in modulating the mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death.

MEKK1 belongs to a tandemly duplicated gene family with MEKK2 and MEKK3. The mekk2 mutant suppressed mekk1, mkk1/2, and mpk4 cell death46,47. Notably, the plant size and fresh weight of let1/2mpk4 were similar with those of mekk2mpk4 (Fig. 2f, g). To dissect whether LET1/2 and MEKK2 function independently or in a same pathway in regulating the mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death, we generated the mekk2let1/2mpk4 quadruple mutant. The plant size and fresh weight of mekk2let1/2mpk4 are not significantly different from those of let1/2mpk4 or mekk2mpk4 (Fig. 2f, g), suggesting that LET1 and LET2/MDS1 function genetically in the same pathway with MEKK2. The mpk4 mutant displays the increased root width, which is independent of MEKK246. Similarly, the increased root width in mpk4 was not suppressed in the let1mpk4, let2mpk4, let1/2mpk4, or mekk2let1/2mpk4 mutants (Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting that LET1 and LET2/MDS1 are not involved in MPK4-regulated root development.

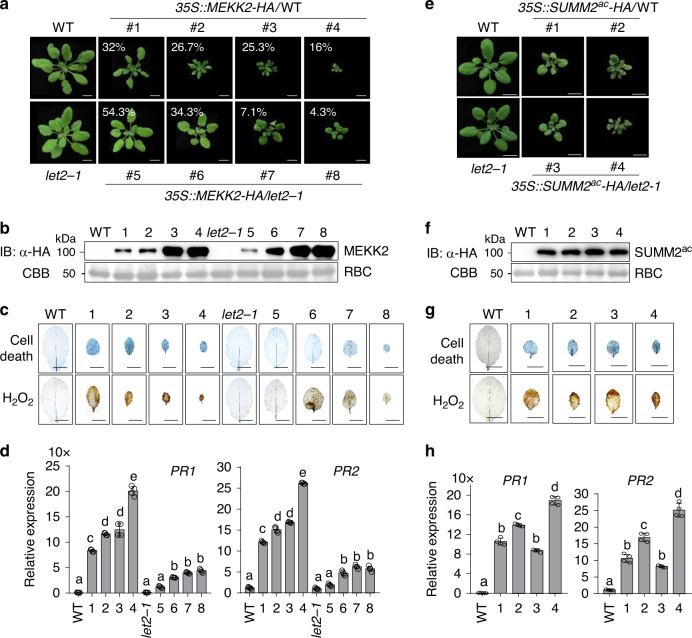

LET2/MDS1 functions genetically downstream of MEKK2 and upstream of SUMM2

Since both LET2/MDS1 and MEKK2 are required for SUMM2 activation, we tested the genetic relationship of LET2/MDS1 with MEKK2 and SUMM2. Overexpression of MEKK2 under a constitutive 35S promoter induced growth defects, cell death, H2O2 accumulation, and expression of PR genes in WT background, which were positively correlated to the MEKK2 protein level (Fig. 3a–d). We have obtained 75 independent transgenic plants carrying 35S::MEKK2-HA at the T1 generation with positive signals by α-HA immunoblots. We further classified them into four categories according to the growth defect severity: 16% (12 out of 75) plants exhibited severe dwarfism and cell death; 25.3% (19 out of 75) showed moderate dwarf and cell death; 26.7% (20 out of 75) exhibited further alleviated dwarfism with relatively big leaves and 32% (24 out of 75) exhibited weak dwarfism (Fig. 3a). We also generated 70 independent transgenic plants at the T1 generation expressing 35S::MEKK2-HA in the let2-1 background with immunoblot positive signals for MEKK2-HA. Overall, the plant dwarfism and growth defects triggered by overexpressing MEKK2 in WT were alleviated in let2-1 with 4.3% (3 out of 70) of plants showing severe dwarfism and cell death, 7.1% (5 out of 70) showing moderate dwarfism, 34.3% (24 out of 70) showing weak dwarfism, and 54.3% (38 out of 70) showing slightly smaller size than let2-1 (Fig. 3a). The cell death, H2O2 accumulation, and expression of PR genes caused by overexpressing MEKK2 were also reduced in let2-1 compared to WT plants (Fig. 3c, d). Notably, the protein expression level of MEKK2 was similar in let2-1 and WT plants (Fig. 3b). The data indicate that LET2/MDS1 is required for overexpressing MEKK2-activated cell death and functions genetically downstream of MEKK2.

Fig. 3. LET2/MDS1 is required for MEKK2-, but not SUMM2ac-mediated autoimmunity.

a Plant dwarfisms and growth defects triggered by overexpressing MEKK2 in WT are alleviated in the let2-1 mutant. 75 and 70 independent primary (T1) transgenic plants carrying 35S::MEKK2-HA in WT and let2-1 were characterized, respectively. Four-week-old plants representing different levels of dwarfisms labeled with the percentage of the cognate category are shown. Scale bar, 1 cm. b Protein expression of MEKK2-HA in transgenic plants. Total proteins were isolated from plants in a and immunoblotted using an α-HA antibody (top panel). CBB staining for RBC is shown as the loading control (bottom panel). c The cell death and H2O2 accumulation triggered by overexpressing MEKK2 in WT are reduced in the let2-1 mutant. Leaves from plants in a were stained by trypan blue for cell death (upper panel) and DAB for H2O2 (lower panel). Scale bar, 0.5 cm. d The elevated expression of PR1 and PR2 triggered by overexpressing MEKK2 in WT is reduced in let2-1. The expression of PR1 and PR2 was normalized to the expression of UBQ10 and the data are shown as the mean ± SE of four biological repeats (n = 4). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). The plants 1–4 are 35S::MEKK2-HA/WT, and 5–8 are 35S::MEKK2-HA/let2-1 (a–d). e Plant dwarfisms and growth defects triggered by overexpressing SUMM2ac are similar in WT and let2-1. In all, 68 and 71 independent primary (T1) transgenic plants carrying 35S::SUMM2ac-HA in WT and let2-1 were characterized respectively. Two represenstative 3-week-old plants, which showed the growth defects, and their controls, are shown in the figure. Scale bar, 1 cm. f Protein expression of SUMM2ac-HA in transgenic plants. g The cell death and H2O2 accumulation triggered by overexpressing SUMM2ac in WT and let2-1. h The expression levels of PR1 and PR2 triggered by overexpressing SUMM2ac in WT and let2-1. The expression of PR1 and PR2 was normalized to the expression of UBQ10 and the data are shown as the mean ± SE of four biological repeats (n = 4). P < 1.00 × 10−15 (PR1, column 1 and 2), P < 1.00 × 10−15 (PR1, column 1 and 3), P = 2.62 × 10−12 (PR1, column 1 and 4), P < 1.00 × 10−15 (PR1, column 1 and 5), P = 1.24 × 10−7 (PR2, column 1 and 2), P = 1.04 × 10−10 (PR2, column 1 and 3), P = 5.86 × 10−6 (PR2, column 1 and 4), P < 1.00 × 10−15 (PR2, column 1 and 5). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). The plants 1–2 are 35S::SUMM2ac-HA/WT, and 3–4 are 35S::SUMM2ac-HA/let2-1 (e–h). The above experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

It has been reported that the active SUMM2 (SUMM2ac), which bears an aspartate-to-valine mutation at the 478th amino acid residue in the methionine-histidine-aspartic acid (MHD) motif triggers cell death in Nicotiana benthamiana45. To delineate the genetic relationship of SUMM2 and LET2/MDS1 in cell death regulation, we generated 35S::SUMM2ac-HA transgenic plants in WT and let2-1. About 52.9% (36 out of 68) of 35S::SUMM2ac-HA transgenic plants in WT showed growth defects, cell death, H2O2 accumulation, and elevated expression of PR genes (Fig. 3e–h). The 35S::SUMM2ac-HA transgenic plants in let2-1 showed a similar level of plant growth defects and dwarfism with 53.5% (38 out of 71) of plants (Fig. 3e–h). The protein expression level of SUMM2ac is comparable in WT and let2-1. The data indicate that LET2/MDS1 is not required for active SUMM2-triggered cell death and might act independently or upstream of SUMM2. Taken together, our results suggest that LET2/MDS1 functions genetically downstream of MEKK2 and upstream of SUMM2 in the mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death pathway. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that LET2/MDS1 functions independently of SUMM2 in the mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death pathway.

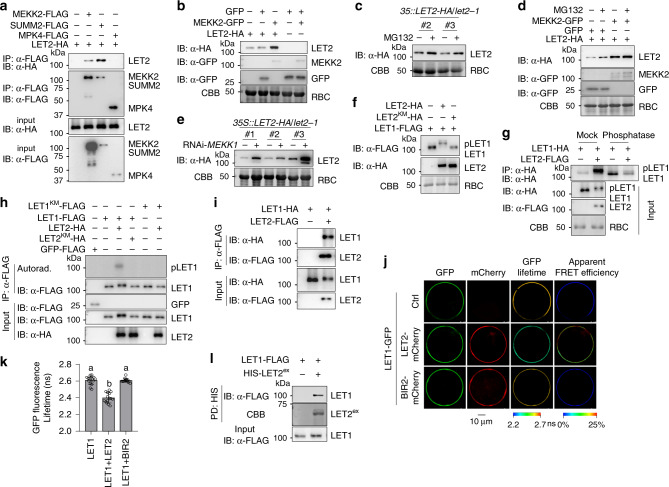

LET2/MDS1 promotes LET1 phosphorylation and heteromerizes with LET1

Consistent with the genetic data, a co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay with HA-tagged LET2/MDS1, and FLAG-tagged MEKK2, SUMM2, or MPK4 co-expressing in Arabidopsis protoplasts indicated that LET2/MDS1 associated with MEKK2 and SUMM2, but not MPK4 (Fig. 4a). We observed an increased protein accumulation of LET2-HA when co-expressing with MEKK2-GFP, but not GFP alone, in N. benthamiana (Fig. 4b). Notably, MEKK2 did not affect GFP proptein level (Fig. 4b). The data suggest that MEKK2 might stabilize LET2/MDS1 in modulating SUMM2 activation. Consistently, LET2/MDS1 proteins were stabilized by the treatment of MG132, a proteasome-dependent protein degradation inhibitor, in 35S::LET2-HA transgenic plants and in N. benthamiana (Fig. 4c, d). Notably, the effect of MG132 was less pronounced in the presence of MEKK2, suggesting that MEKK2 had a similar effect with MG132 on the stabilization of LET2-HA (Fig. 4d). The defect of MEKK1-MKK1/2-MPK4 pathway induced accumulation of MEKK2 transcripts and proteins47, which might lead to the stabilization of LET2/MDS1. Consistent with this hypothesis, the amount of LET2-HA protein was increased in three independent 35S::LET2-HA transgenic plants upon silencing MEKK1 by VIGS (Fig. 4e). Collectively, these results suggest that MEKK2 modulates LET2/MDS1 protein homeostasis.

Fig. 4. LET1 and LET2/MDS1 regulation and heteromerization.

a LET2/MDS1 associates with MEKK2 and SUMM2, but not MPK4. LET2-HA was co-expressed with Ctrl, MEKK2-FLAG, SUMM2-FLAG, or MPK4-FLAG in protoplasts for 12 h. The FLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated by α-FLAG affinity beads, and then immunoblotted by an α-HA or α-FLAG antibody (top two panels). The proteins before immunoprecipitation were immunoblotted by an α-HA or α-FLAG antibody as inputs (bottom two panels). b MEKK2 stabilizes LET2/MDS1 protein accumulation in N. benthamiana. LET2-HA or GFP was co-expressed with MEKK2-GFP or GFP in N. benthamiana for 3 days. The proteins were immunoblotted by an α-HA or α-GFP antibody. CBB staining of RBC was used as a loading control. c MG132 treatment increases LET2/MDS1 protein accumulation in transgenic plants. The 10-day-old seedings of 35S::LET2-HA/let2-1 (Line #2 and #3) transgenic plants were treated with DMSO (Ctrl) or 5 μM MG132 for 6 h. Proteins were immunoblotted using an α-HA antibody, and CBB was used as a loading control. d MG132 treatment increases LET2/MDS1 protein accumulation in N. benthamiana. The leaves of N. benthamiana were inoculated with Agrobacterium carrying LET1-HA and GFP, or LET1-HA and MEKK2-GFP for 12 h, and then treated with DMSO (Ctrl) or 5 μM MG132 for anthor 36 h. Proteins were immunoblotted by an α-HA or α-GFP antibody. CBB was used as a loading control. e Silencing MEKK1 increases LET2/MDS1 protein accumulation. MEKK1 was silenced in the 35S::LET2-HA/let2-1 transgenic plants (Line #1, #2 and #3) by VIGS. Total proteins were extracted 2 weeks after VIGS, and immunoblotted using an α-HA antibody. CBB was used as a loading control. f LET2/MDS1, but not its kinase-inactive mutant LET2KM, induces LET1 mobility shift. LET2-HA or LET2KM-HA was co-expressed with LET1-FLAG in protoplasts for 12 h. LET1-FLAG was separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE. CBB staining of RBC was used as a loading control. g LET2/MDS1 induces LET1 phosphorylation. LET1-HA was co-expressed with Ctrl or LET2-FLAG in protoplasts for 12 h. LET1-HA was immunoprecipitated by α-HA affinity beads. The immunoprecipitated LET1-HA protein was incubated without or with 0.5 μL (200 U) λ-phosphatase (Sigma) for 1 h at 30 °C. LET1-HA was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and detected by an α-HA antibody (top panel). LET1-HA and LET2-FLAG before immunoprecipitation were detected by the corresponding antibody (middle two panels). CBB staining of RBC was used as a loading control (bottom panel). h LET2/MDS1 increases LET1 kinase activity. LET1-FLAG or LET1KM-FLAG was co-expressed with the vector control, LET2-HA or LET2KM-HA, in protoplasts. The FLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates with α-FLAG affinity beads and used in a kinase assay with [γ-32P] ATP. The GFP-FLAG was used as a negative control. The proteins were immunoblotted by an α-FLAG or α-HA antibody for input controls. i LET1 associates with LET2/MDS1. LET1-HA was co-expressed with Ctrl or LET2-FLAG in protoplasts for 12 h. The LET2-FLAG proteins were immunoprecipitated by α-FLAG affinity beads, and then immunoblotted by an α-HA or α-FLAG antibody (top two panels). The proteins before immunoprecipitation were immunoblotted by an α-HA or α-FLAG antibody as inputs (bottom two panels). j, k FRET-FLIM analysis of LET1 and LET2/MDS1 interaction in Arabidopsis protoplasts. The indicated proteins were transiently expressed in protoplasts for 16 h, and FRET-FLIM was visualized using a confocal laser scanning microscopy (j). Localization of the LET1-GFP and LET2-mCherry/BIR2-mCherry is shown with the first (Green) and second column (Red), respectively. The lifetime (τ) distribution (third column), and apparent FRET efficiency (fourth column) are presented as pseudo-color images according to the scale. The GFP mean fluorescence lifetime (τ) values, ranging from 2.2 to 2.7 nanoseconds (ns), were statistically analyzed and are shown as mean ± SD (n = 15) (k). P = 1.07 × 10−12 (column 1 and 2), P = 1.08 × 10−12 (column 2 and 3). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). Scale bar, 10 µm. l LET2ex associates with LET1 in a pull-down assay. Arabidopsis protoplasts expressing LET1-FLAG were incubated with purified HIS-SUMO-LET2ex proteins. The interaction between LET1 and LET2ex was detected by an α-FLAG immunoblot after pull-down with Ni-NTA agarose. HIS-SUMO-LET2ex proteins were stained by CBB. The above experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

Significantly, we observed a mobility shift of LET1 in the presence of LET2/MDS1, but not its kinase mutant LET2KM (Fig. 4f). The mobility shift of LET1 induced by LET2/MDS1 could be removed by the λ-phosphatase treatment (Fig. 4g), suggesting that LET2/MDS1 promotes LET1 phosphorylation in a kinase activity-dependent manner. Apparently, LET2/MDS1 did not induce mobility shift of FER (Supplementary Fig. 3a), and FER also did not affect LET1 mobility (Supplementary Fig. 3b). We also did not observe any mobility shift of LET2/MDS1 in the presence of LET1 in either regular or Phos-tag SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The data indicate that LET2/MDS1 specifically promotes LET1 phosphorylation. Consistently, LET2/MDS1, not its kinase-inactive mutant, activated the kinase activity of LET1 in vitro when LET1 and LET2/MDS1 were co-expressed in protoplasts and immunoprecipitated for an in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 4h). We further observed that LET2/MDS1 complexed with LET1 in a Co-IP assay (Fig. 4i). The Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) measurements revealed that LET1-GFP proteins were in close proximity to LET2-mCherry, but not BIR2-mCherry, when co-expressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts (Fig. 4j, k). Furthermore, LET2/MDS1 extracellular domain (LET2ex) purified from E. coli could pull-down LET1-FLAG expressed in protoplasts (Fig. 4l). Thus, LET2/MDS1 complexes with LET1 and regulates LET1 phosphorylation.

The llg1 mutants specifically suppress RNAi-MEKK1 cell death

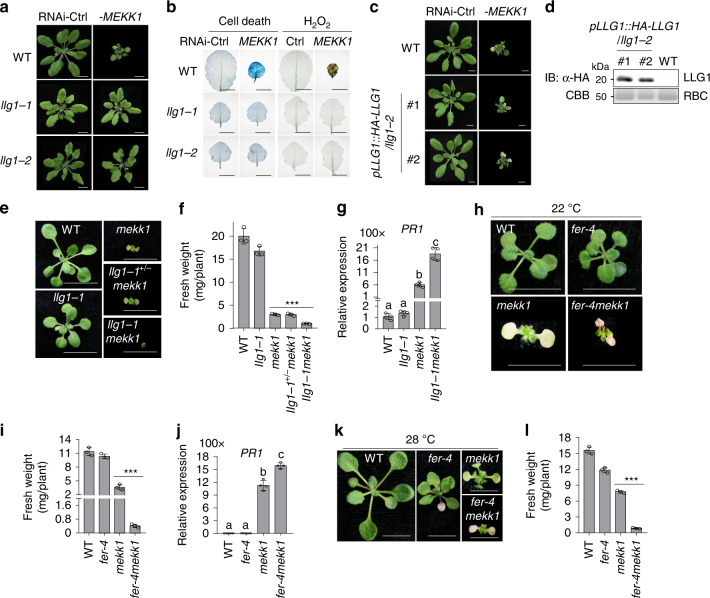

The GPI-anchored proteins LRE, LLG1, LLG2, and LLG3, function as adapters/co-receptors for CrRLK1Ls FER and BUPSs/ANXs28–31. LLG2 and LLG3 function redundantly in regulating pollen tube integrity30,31. We tested whether LRE/LLGs are involved in LET1/2-mediated mekk1 cell death by silencing MEKK1 in the corresponding single and double mutants, including two lre mutant alleles (lre-3 and lre-6), two llg1 mutant alleles (llg1-1 and llg1-2), llg2-1, and llg3-1 single mutants, and llg2-1llg3-1 double mutant. The llg1 mutants, llg1-1 and llg1-2, but not other mutants, suppressed the growth defects (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 4a), cell death, H2O2 accumulation (Fig. 5b), and constitutive expression of PR genes (Supplementary Fig. 4b) caused by silencing MEKK1, suggesting a specific role of LLG1 in controlling mekk1 cell death. Both llg1-1 and llg1-2 mutants display certain growth defects with reduced plant size (Fig. 5a). The llg1-3 mutant, which bears a mutation in glycine at the 114th amino acid to arginine, grew similarly as WT plants (Supplementary Fig. 4c)32. To exclude the effect of growth defect of llg1-1 and llg1-2 on RNAi-MEKK1 cell death, we silenced MEKK1 in the llg1-3 mutant by VIGS. The llg1-3 mutant also suppressed growth retardation, cell death and PR1 expression caused by RNAi-MEKK1 (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d), indicating that LLG1-regulated growth and MEKK1 cell death are uncoupled. We also tested whether LLG1 with a N-terminal HA tag under its native promoter in llg1-2 (pLLG1::HA-LLG1/llg1-2)28 could complement RNAi-MEKK1 cell death. Two representative lines, #1 and #2, restored the cell death and PR gene expression induced by silencing MEKK1 (Fig. 5c, d and Supplementary Fig. 4b). The data implicate that similar to LET1 and LET2/MDS1, LLG1 modulates RNAi-MEKK1 cell death.

Fig. 5. LLG1 regulates mekk1 cell death.

a The llg1 mutants suppress growth defects triggered by silencing MEKK1. The plant images were photographed at 3-weeks after inoculation with Agrobacterium carrying the indicated VIGS vectors. Ctrl is the vector containing GFP. Scale bar, 1 cm. b The llg1 mutants suppress cell death and H2O2 accumulation induced by silencing MEKK1. The leaves from plants in a were stained by trypan blue for cell death and DAB for H2O2 accumulation. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. c Expression of HA-LLG1 in llg1-2 restores the cell death triggered by silencing MEKK1. #1 and #2 are two representative pLLG1::HA-LLG1 transgenic lines in llg1-2. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. d Protein expression of HA-LLG1 in pLLG1::HA-LLG1/llg1-2 transgenic plants. e The llg1-1mekk1 mutant enhances growth defects of mekk1. The seedlings grown on ½MS plate at 22 °C were photographed at 2-weeks post-germination. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. f The fresh weight of llg1-1mekk1 is less than mekk1. The data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 3). P = 3.63 × 10−5 (column 3 and 5). The asterisk indicates statistical significance by using two-sided two-tailed Student’s t test (***P < 0.001). g llg1-1 mutant enhances the expression of PR1 in mekk1. The expression of PR1 was determined with the plants in e and normalized to the expression of UBQ10. The data are shown as the mean ± SE of four biological repeats (n = 4). P = 1.04 × 10−7 (column 3 and 4). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). h The fer-4mekk1 mutant enhances growth defects of mekk1. The seedlings grown on ½MS plate at 22 °C were photographed at 2-weeks post-germination. Scale bar, 1 cm. i The fresh weight of fer-4mekk1 mutant is less than mekk1. The data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 3). P = 6.92 × 10−4 (column 3 and 4). The asterisk indicates statistical significance by using two-sided two-tailed Student’s t test (***P < 0.001). j fer-4 mutant enhances the expression of PR1 in mekk1. The expression of PR1 was normalized to the expression of UBQ10 and the data are shown as the mean ± SE of four biological repeats (n = 4). P = 1.87 × 10−6 (column 3 and 4). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). The assay was performed as in g. k High temperature did not alleviate fer-4mekk1 growth defects. The seedlings grown on ½MS plate at 28 °C were photographed at 2-weeks post-germination. Scale bar, 1 cm. l The fresh weight of fer-4mekk1 mutant is less than mekk1 at 28 °C. The seedlings in k were used for measuring fresh weight. The data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 3). P = 1.81 × 10−6 (column 3 and 4). The asterisk indicates statistical significance by using two-sided two-tailed Student’s t test (***P < 0.001). To measure the weight of mekk1, llg1mekk1, and fer-4mekk1 mutants, 10 plants were pooled and the weight of individual plants was averaged. The above experiments were repeated 3–4 times with similar results.

We then generated the llg1-1mekk1 double mutant by genetic crosses. To our surprise, the llg1-1mekk1 double mutant did not suppress mekk1 cell death. In contrast, the llg1-1mekk1 mutant displayed more severe growth defects, reduced fresh weight and elevated PR1 gene expression than the mekk1 mutant of 3-week-old seedlings grown on ½MS plates (Fig. 5e–g). To rule out the allele specific effect of llg1-1, we generated llg1-2mekk1 and llg1-3mekk1 double mutants. Similar to llg1-1mekk1, both llg1-2mekk1 and llg1-3mekk1 mutants displayed further aggravated growth defects compared to mekk1 (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). The data suggest that the llg1 mutants can enhance the growth defects of genetic null mutant mekk1. The mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death is temperature dependent, and the moderately increased temperature could alleviate mekk1 cell death likely through the suppression of the salicylic acid (SA) pathway44. However, unlike mekk1 or llg1-1+/−mekk1 (llg1-1 is heterozygous), the growth defects of llg1-1mekk1 grown at 28 °C were as severe as plants grown at 22 °C (Supplementary Fig. 5c). The data suggest that the enhanced growth defects of llg1mekk1 is temperature-independent, which is different from that of mekk1.

The above data point to an intriguing and apparently contradict observation: the llg1 mutants aggravated the growth defects caused by genetic lesions in mekk1, whereas suppressed cell death triggered by RNAi-mediated silencing of MEKK1. Notably, VIGS was performed using 12-day-old seedlings, and the silence effects of MEKK1 were apparent after 20-days post-germination. Compared to the genetic mutations, VIGS-mediated silencing bypasses the defects associated with embryonic and early seedling development51. The opposing effects of LLG1 on silencing and null mutations of MEKK1 suggest that LLG1 plays one role in regulating initial seedling development in concert with MEKK1, and another role in regulating mekk1 cell death at a later stage. This is in line with the notion that LLG1 acts through interactions with different CrRLK1Ls as an adapter/co-receptor and regulates various biological processes. The mutations of LLG1 and the CrRLK1L FER cause similar growth defects28. We tested whether the fer-4 mutant exerted an effect on the mekk1 growth defects by generating a fer-4mekk1 double mutant. Similar to llg1mekk1, the fer-4mekk1 double mutant showed further aggravated growth defects (Fig. 5h), reduced fresh weight (Fig. 5i), and increased PR1 gene expression (Fig. 5j) compared to the mekk1 mutant. Unlike mekk1, the enhanced growth defects in the fer-4mekk1 mutant cannot be recovered when plants were grown at 28 °C (Fig. 5k, l), consistent with the temperature-independent cell death in the llg1-1mekk1 mutants (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Taken together, LLG1 is required for mekk1 cell death. In addition, LLG1 plays a role together with FER and MEKK1 in regulating early seedling development.

The llg1-1 mutation suppresses mkk1/2 and mpk4 cell death

We further tested whether the mutation in LLG1 affects mkk1/2 and mpk4 cell death by generating the llg1-1mkk1/2 (llg1mkk1/2) triple mutant (Supplementary Fig. 6a), and the llg1-1mpk4 (llg1mpk4) double mutant (Supplementary Fig. 6b). The llg1-1 mutant partially suppressed the cell death in the mkk1/2 mutant when grown on ½MS plates (Fig. 6a). The llg1mkk1/2 mutant was bigger than mkk1/2 in size and had significantly increased fresh weight compared to mkk1/2 (Fig. 6b). The true leaves of llg1mkk1/2 were also larger than those of mkk1/2. At the 2-week-old seedling stage, the first pair of true leaves already senescenced in mkk1/2 but still kept green in llg1mkk1/2 (Fig. 6a). Compared with mkk1/2, the expression of PR1 was partially suppressed in llg1mkk1/2 (Fig. 6c). Notably, the llg1+/− mkk1/2 mutant, in which LLG1 was heterozygous, had no effect on mkk1/2 cell death, suggesting that llg1 is a complete recessive mutation in regulating mkk1/2 cell death.

Fig. 6. LLG1 genetically functions downstream of MEKK2.

a The llg1-1 mutant partially suppresses the mkk1/2 cell death. The seedlings grown on ½MS plate were photographed at 2-weeks post-germination. The leaves from the individual plants were placed with the order of age (from oldest to youngest, right panels). Scale bar, 0.5 cm. b llg1-1 increases the fresh weight of mkk1/2. The data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 4). P = 1.46 × 10−2 (column 3 and 5). The asterisk indicates statistical significance by using two-sided two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05). c The llg1-1 mutant reduces the expression of PR1 in mkk1/2. The expression of PR1 was determined with the plants in a and normalized to the expression of UBQ10. The data are shown as the mean ± SE of four biological repeats (n = 4). P = 2.06 × 10−5 (column 3 and 5). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). d The llg1-1 mutant partially suppresses the mpk4 cell death. The plants grown on soil were photographed at 4-weeks after germination. Scale bar, 1 cm. e llg1-1 increases the fresh weight of mpk4. The data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 4). P = 4.69 × 10−3 (column 3 and 5). The asterisk indicates statistical significance by using two-sided two-tailed Student’s t test (***P < 0.01). f The llg1-1 mutant reduces the expression of PR1 in mpk4. The expression of PR1 was determined with the plants in d and normalized to the expression of UBQ10. The data are shown as the mean ± SE of four biological repeats (n = 4). P = 6.78 × 10−8 (column 3 and 5). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). g Overexpressing MEKK2 triggers growth defects in WT, but not in llg1-1. Three representative lines were used to indicate the phenotype of transgenic lines in WT Col-0 and llg1-1 with different MEKK2-HA expression level. The pictures were taken with 4-week-old soil-grown plants. Scale bar, 1 cm. h The protein accumulation of MEKK2-HA in WT and llg1-1 transgenic plants. Total proteins were isolated from plants in g and immunoblotted using an α-HA antibody (top panel). CBB staining of RBC is shown as the loading control (bottom panel). i The elevated expression of PR1 triggered by overexpressing MEKK2 in WT (Lines 1, 2, and 3) is reduced in llg1-1 (Lines 4, 5, and 6). The expression of PR1 was normalized to the expression of UBQ10 and the data are shown as the mean ± SE of four biological repeats (n = 4). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). To measure the weight of mkk1/2 and mpk4 mutants, 10 plants were pooled and the weight of individual plants was averaged. The above experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

The rosette size of the llg1mpk4 mutant was also bigger than mpk4 when grown on soil (Fig. 6d). The fresh weight of llg1mpk4 was significantly higher than that of mpk4 (Fig. 6e), and the increased PR1 expression in mpk4 was partially reduced in llg1mpk4 (Fig. 6f). Interestingly, the llg1+/−mpk4 mutant behaved in between mpk4 and llg1mpk4 in terms of rosette size, fresh weight, and PR1 gene expression (Fig. 6d–f), indicating that LLG1 regulates mpk4 cell death in a dosage-dependent manner. It was reported that the mekk2 mutant rescued the mpk4 cell death in a dosage-dependent manner47. Altogether, similar as the let2 mutants, the llg1 mutants suppressed mkk1/2 and mpk4 cell death, suggesting that LLG1 functions genetically downstream of MPK4 in regulating mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death.

The mutations in LLG1 block MEKK2-, but not SUMM2ac-triggered cell death

To delineate the genetic position of LLG1 with MEKK2 and SUMM2 in the regulation of cell death, we examined whether llg1 mutants exerted an effect on overexpressing MEKK2 or active SUMM2 (SUMM2ac)-triggered cell death by expressing 35S::MEKK2-HA or 35S::SUMM2ac-HA in llg1 mutants. As shown previously (Fig. 3a), overexpressing MEKK2-HA in WT caused growth defects and elevated PR1 expression in a dosage-dependent manner (Fig. 6g–i). However, multiple transgenic lines expressing 35S::MEKK2-HA in llg1-1 were phenotypically similar to llg1-1 in terms of plant size irregardless of MEKK2-HA protein expression levels (Fig. 6g, h). The increased expression of PR1 triggered by 35S::MEKK2-HA in WT plants was also reduced in llg1-1 (Fig. 6i). In addition, another LLG1 mutant allele, llg1-3, also blocked overexpressing MEKK2-HA-triggered growth defects and cell death (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). The data indicate that LLG1 is required for MEKK2-triggered cell death and acts genetically downstream of MEKK2. However, the llg1-3 mutant did not affect growth defects and cell death caused by overexpressing SUMM2ac-HA compared to WT plants (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). Taken together, similar to LET1 and LET2/MDS1, LLG1 functions downstream of MEKK2 and upstream of SUMM2 in the mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death pathway.

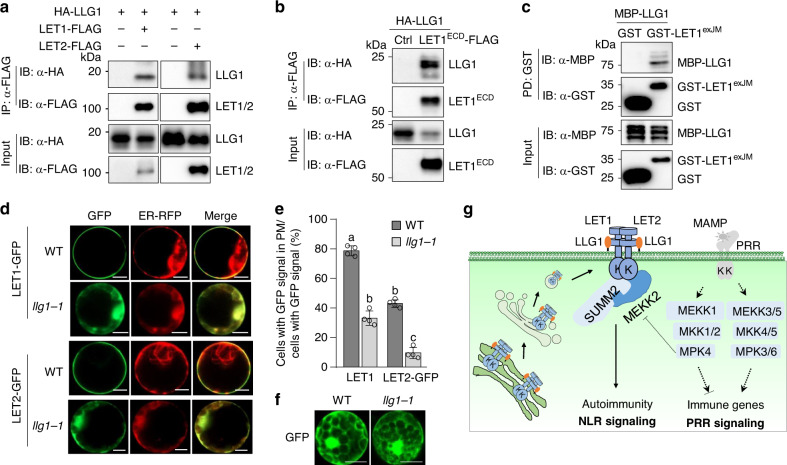

LLG1 associates with LET proteins and is required for their plasma membrane localization

LLGs directly interacts with the extracellular juxtamembrane region of some CrRLK1Ls and function as co-receptors/adapters of CrRLK1Ls in regulating plant growth, reproduction, and immunity28–31. We hypothesized that LLG1 functions in the mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death pathway through interaction and modulation of CrRLK1Ls LET1 and LET2/MDS1. To test this, we performed Co-IP assays between LLG1 and LET1 or LET2/MDS1. When N-terminal HA-tagged LLG1 (HA-LLG1) was co-expressed with C-terminal FLAG-tagged LET1 (LET1-FLAG) or LET2/MDS1 (LET2-FLAG) in Arabidopsis protoplasts, both LET1 and LET2/MDS1 immunoprecipitated LLG1 (Fig. 7a). We further tested whether LLG1 interacted with the extracellular malectin-like domains (ECD) of LET1 (LET1ECD). When co-expressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts, LET1ECD-FLAG could co-immunoprecipitate HA-LLG1 (Fig. 7b). We then determined whether LLG1 directly interacted with the extracellular juxtamembrane (exJM) domain of LET1 with an in vitro pull-down assay. To do this, we purified the exJM domain of LET1 (amino acid 337–400) fused with glutathione S-transferase (GST-LET1exJM), and the LLG1 truncation without the signal peptide (SP; amino acid 24–149) fused with the maltose-binding protein (MBP-LLG1) from E. coli and performed an in vitro pull-down assay with glutathione agarose beads. As shown in Fig. 7c, GST-LET1exJM, but not GST alone, pulled down MBP-LLG1, indicating a direct interaction between LLG1 and the exJM domain of LET1. Taken together, LLG1 likely functions as an adapter/co-receptor of LET1 and LET2/MDS1 in cell death regulation.

Fig. 7. LLG1 interacts with LETs and facilitates their plasma membrane localization.

a LLG1 interacts with LET1 and LET2/MDS1. HA-LLG1 was co-expressed with Ctrl, LET1-FLAG or LET2-FLAG, in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Total proteins were immunoprecipitated with α-FLAG affinity beads and then immunoblotted by an α-HA or α-FLAG antibody (top two panels). Immunoblots using total proteins before immunoprecipitation are shown as protein inputs (bottom two panels). b LLG1 interacts with the LET1 extracellular domain (LET1ECD) in Arabidopsis protoplasts. The assay was performed as in a. c LLG1 directly interacts with LET1 extracellular juxtamembrane domain (LET1exJM) in vitro. MBP-LLG1 (without signal peptide), GST-LET1exJM and GST fusion proteins isolated from E. coli were used for an in vitro pull-down assay using glutathione agarose beads followed by immunoblotting using an α-MBP or α-GST antibody (top two panels). Input proteins were immunoblotted by an α-MBP or α-GST antibody before pull-down (bottom two panels). d Representative subcellular localization patterns of LET1-GFP and LET2-GFP proteins in WT and llg1-1 protoplasts. The images were taken under laser scanning confocal microscopy at 12 h after transfection. ER-RFP was used as an ER marker. Scale bar, 50 μm. e The percentage of LET1-GFP and LET2-GFP signals in PM in WT and llg1-1. The ratio of protoplasts with only PM-localized LET-GFP signals to the total protoplasts with GFP signals was measured over 100 fluorescent cells. The protoplasts without clear PM-localized GFP signals show ER-localized GFP signals. The data are shown as mean ± SE of four independent transfections (n = 4). P = 4.40 × 10−9 (column 1 and 2) and P = 1.39 × 10−7 (column 3 and 4). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.001). f Similar localization of GFP in WT and llg1-1 protoplasts. The images were taken at 12 h after transfection. Scale bar, 100 μm. g A model of LET1-LET2-LLG1 complex in cell death regulation. MAMP-activated MEKK1-MKK1/2-MPK4 cascade regulates PRR-mediated immune signaling, and SUMM2-mediated autoimmunity via suppressing MEKK2 expression. Two CrRLK1Ls, LET1 and LET2/MDS1, together with GPI-anchored protein LLG1, form a trimeric complex to modulate SUMM2 activation. LLG1 likely functions as a co-receptor of LET1/2 and assists LET1/2 protein maturation and delivery from endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi to plasma membrane (PM). The above experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

LLG1 functions as a chaperone assisting FER protein delivery from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the plasma membrane (PM), which is essential for extracellular signal perception and signaling initiation28. To test where LET1 and LET2/MDS1 are localized and whether the localization is mediated by LLG1, we analyzed the subcellular localization of LET1 fused with green fluorescent protein (LET1-GFP) and LET2-GFP in protoplasts of WT and the llg1-1 mutant. In WT protoplasts, the majority of cells with LET1-GFP signals (~80%) displayed PM localization (Fig. 7d, e), whereas in llg1-1, only ~35% of cells with LET1-GFP signals displayed PM localization. The majority of LET1-GFP signals in llg1-1 co-localized with the ER marker (Fig. 7d). Similarly, the ratio of LET2-GFP signals in PM was reduced from ~45% in WT to ~8% in llg1-1, and the ER localization of LET2-GFP was significantly increased in llg1-1 (Fig. 7d, e). The llg1-1 mutant did not affect free GFP localization (Fig. 7f). These data indicate that LLG1 is important for LET1 and LET2/MDS1 transport from ER to PM (Fig. 7g).

Discussion

CrRLK1Ls that carry an extracellular malectin-like domain are key regulators in various developmental processes and plant defense responses to pathogens12–15. In a parallel study of using a VIGS-based RNAi screen of mekk1 cell death suppressors with a collection of Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion lines, we identified the uncharacterized CrRLK1L, LET1, as a specific regulator of mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 autoimmunity49. In this study, by screening individual CrRLK1Ls and revealed that LET2/MDS1 plays an additive role with LET1 in regulating mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 autoimmunity. The LET2/MDS1 closest tandemly arrayed homologs, MDS2, MDS3, and MDS4, had little contribution in modulating this process despite of their partially redundant role in regulating plant responses to ion metal (Fig. 1d).

Similar with LET1, LET2/MDS1 acts genetically downstream of MEKK2 and upstream of SUMM2 (Fig. 3). We also show that LET2/MDS1 interacts with MEKK2 and SUMM2 and its stability is regulated by MEKK2 (Fig. 4a–e). Thus, LET1 and LET2/MDS1 might have similar and additive function in modulating mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 autoimmunity. This is supported by the observation that the let1/2 double mutant further alleviated mekk1, mkk1/2, and mpk4 autoimmunity compared to let1 or let2 single mutants (Fig. 2). Notably, the single mutants of let1 or let2 clearly suppressed mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death (Fig. 2), suggesting that LET1 and LET2/MDS1 might not simply function redundantly in regulating SUMM2 activation. Indeed, we observed that LET1 interacts with LET2/MDS1, and importantly, expression of LET2/MDS1 promotes LET1 phosphorylation (Fig. 4). Consistent with this observation, mutations of either LET1 or LET2/MDS1 in the let1 or let2 single mutants lead to the inactivation of SUMM2 in mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death. The additive effect of LET1 and LET2/MDS1 in regulating mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death also suggests that LET1 and LET2/MDS1 might have independent functions in this pathway. This could be due to that LET1 and LET2 might also form LET1 or LET2/MDS1 homodimers, in addition to LET1/2 heterodimer. In addition, LET1 and LET2/MDS1 might be activated by different ligands in modulating mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death.

We have shown that MEKK2 likely plays a structural role, rather than functions as a kinase, in regulating SUMM2 activation52. Consistently, MEKK2 scaffolds LET1 and SUMM2 for signaling activation49. However, both LET1 and LET2/MDS1 have autophosphorylation activity, and their kinase activity is required for their functions (Fig. 1g–i)49. Thus, LET1 and LET2/MDS1 are authentic kinases in the activation of SUMM2. It has been proposed that NLRs are kept in an inactive form by intramolecular interaction (such as interaction between NBS and LRR domains), and disruption of intramolecular interaction activates NLRs6,8. LET1/2 may activate SUMM2 through a phosphorylation-based conformational change of SUMM2 to disrupt its intramolecular interaction. LET1/2 phosphorylation may also induce oligomerization of SUMM2 for NLR activation53. It has been proposed that CRCK3, a MPK4 substrate, is guarded by SUMM2 to monitor the integrity of the MEKK1-MKK1/2-MPK4 cascade48. It will be interesting to determine whether there is a connection between LET1/2 and CRCK3-mediated phosphorylation in the activation of SUMM2.

The GPI-anchored proteins LRE and LLGs have been proposed as co-receptors of FER, BUSP1/2 and ANX1/2, in regulating plant growth, reproduction, and immunity28–31. Our VIGS screen indicates that LLG1, but not LLG2, LLG3, nor LRE, regulates mekk1, mkk1/2, and mpk4 autoimmunity (Figs. 5 and 6). This is consistent with the observation that LLG1 is expressed in seedlings, whereas LRE is a female gametophyte-expressed gene54. LLG2 and LLG3 are strongly expressed in pollens and regulate pollen cell wall integrity30. Epistasis analysis indicates that, similar with LET1/2, LLG1 functions downstream of MEKK2 and upstream of SUMM2 in the mekk1-mkk1/2-mpk4 cell death pathway (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 7). LLG1 interacts with the ectodomain of LET1/2 and mediates LET1/2 transport to the plasma membrane (Fig. 7). Thus, LRE and LLGs function as shared co-receptors of different CrRLK1Ls, and their function specificity is determined by their spatiotemporal expression pattern. Interestingly, LLG1 also associates with PRR complex, contributing to the accumulation of PRR FLS2 and regulating plant immunity32. This suggests that, in addition to CrRLK1Ls, LRR-RLKs could also be regulated by LRE and LLGs. However, it remains unknown whether LLG1 functions in plant immunity through an independent pathway, or through interaction with CrRLK1Ls, such as FER and ANX, both of which have been shown to regulate plant immunity via modulating PRR complexes24,25. Emerging evidence indicates the extracellular peptides of the RALF family act as the ligands of CrRLK1Ls22,24,29,55,56. RALFs or other type of ligands could be the potential ligands of LET1/2-LLG1 module in regulating SUMM2 activation.

Altogether, our results reveal that two CrRLK1Ls, LET1 and LET2/MDS1, together with GPI-anchored protein LLG1, form a trimeric complex to modulate NLR SUMM2, which is activated in the absence of MEKK1-MKK1/2-MPK4 cascade. LLG1 likely functions as a co-receptor of LET1/2 and assists LET1/2 protein maturation and delivery from endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi to plasma membrane (PM) (Fig. 7g).

Methods

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data for quantification analyses are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) or standard deviation (SD). The different letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test (P < 0.05). Number of replicates is shown in the figure legends.

Plant materials

The Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Col-0 was used as wild type (WT). The T-DNA insertion lines, SALK_139579 (let2-1, AT5G38990), SALK_066322 (let2-2, AT5G38990), SALK_074670C (mds3-1, AT5G39020), SALK_007613C (mds4-1, AT5G39030), SALK_029056C (AT3G51550), SALK_133057C (anx2-2, AT5G28680), SALK_016179C (anx1-1, AT3G04690), SALK_105055C (herk2, AT1G30570), SALK_083442C (cap1-1, AT5G61350), SALK_018797C (curvy1, AT2G39360), SALK_114667C (anj-1, AT5G59700), SALK_008043C (herk1-1, AT3G46290), SALK_007108 (mds2-1, AT5G39000), SAIL_907_G02 (AT5G24010), SAIL_809_D01 (AT5G24010), SALK_033062 (AT4G39110), SAIL_33_C06 (AT4G39110), and SAIL_448_D02 (AT2G21480), of different CrRLK1L family members, SAIL_47_G04 (llg1-1) for LLG1, SALK_040289 (ire-3) and CS66103 (ire-6) for LORELEI, SALK_018793C (let1-1), SALK_052557 (mekk1), and SALK_150039C (mekk2) were ordered from Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC). The seeds of herk1-1the1-4 were obtained from Dr. Yanhai Yin57. The seeds of fer-4 (CS69044), llg1-2 (SALK_086036) and pLLG1::HA-LLG1/llg1-2 were obtained from Dr. Alice Cheung28. The seeds of llg1-3 were obtained from Dr. Dingzhong Tang32. The seeds of llg2-1, llg3-1, and llg2-1llg3-1 were obtained from Dr. Lijia Qu30. The seeds of mkk1/2 were obtained from Dr. Patrick Krysan47. The seeds of CRISPR/Cas9-generated double, triple, and quadruple mds mutants were previously reported50. The genotype of all the mutants was confirmed with PCR using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Growth conditions

Plants were grown in the growth rooms with 22 °C, 50–60% relative humidity, 70 µE m−2 s−1 light under 10/14 h light/dark cycles, except where indicated. The seedlings were grown on ½MS medium plates supplemented with 0.5% sucrose, 0.8% agar, and 2.5 mM MES at pH 5.7. The seeds were cold treated for two days at 4 °C before moving to a growth room. For investigating recovery of cell death at high temperature, the seedlings were grown on a ½MS plates in a 22 °C growth room with for 3 days after cold treatment, and then transferred to a 28 °C growth room with the indicated time.

Plasmid constructs

The constructs of pTRV–RNA1 and pTRV–RNA2 of pYL156-GFP and pYL156-MEKK1 have been reported51. The DNA sequence of LET2/MDS1 contains the restriction enzyme sites of BamHI and StuI, which are commonly used in our plant expression and binary vectors. The LET2/MDS1 cDNA fragment containing NcoI-BglII at 5′ and SmaI-SnaBI at 3′ was amplified by PCR and digested by NcoI and SnaBI. The digested fragment was cloned into the linearized pHBT-HA vector digested by NcoI and StuI to get the intermediate construct of pHBT-LET2-HA. The fragment of LET2/MDS1 digested by BglII and SmaI from the pHBT-LET2-HA were cloned into the linearized vectors of pHBT-HA, pHBT-FLAG, pHBT-GFP, pCB302-HA, and pHBT-mCherry digested by BamHI and StuI or SmaI to generate the constructs of pHBT-LET2-HA, pHBT-LET2-FLAG, pHBT-LET2-GFP, pCB302-LET2-HA, and pHBT-LET2-mCherry. The pHBT-LET2KM-HA was generated by Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase-mediated site-directed mutagenesis with pHBT-LET2-HA as a template. The fragment of LET2KM digested by BglII and SmaI from the pHBT- LET2KM-HA was cloned into linearized vectors of pCB302-HA digested by BamHI and StuI to generate the construct of pCB302- LET2KM-HA.

The LET1 (AT2G23200) gene (2502 bp) was amplified by PCR from Col-0 cDNA using the primers containing BamHI at the 5′ end and StuI at the 3′ end49. Due to LET1 fragment containing an internal BamHI site, the LET1 PCR products were digested by BamHI and StuI into two fragments, LET1N (BamHI-LET11-1969 bp-BamHI) and LET1C (BamHI-LET11970-2502 bp-StuI). LET1C was firstly cloned into linearized pHBT-HA digested by BamHI and StuI, and subsequently, LET1N was introduced by BamHI digestion and ligation to obtain pHBT-LET1-HA49. To sub-clone LET1 into other vectors by BamHI and StuI, site-directed mutagenesis by Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase-mediated PCR was used to mutate the internal BamHI site without changing its codons in LET1 and generate pHBT- LET1mBamHI-HA. Then LET1mBamHI were sub-cloned into HBT-HA, HBT-GFP, and pCB302-HA vector through BamHI and StuI. The fragments of MPK4 (AT4G01370, 1128 bp), MEKK2 (AT4G08480, 2319 bp), and SUMM2 (AT1G12280, 2682 bp) were amplified from Col-0 cDNA using the primers containing BamHI at the 5′ end and StuI at the 3′ end, and ligated into pHBT-FLAG vector49. LET1KM and SUMM2ac were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase-mediated PCR. MEKK2 and SUMM2ac were sub-cloned into the binary vectors pMDC32-2x35S::HA or pMDC32-2x35S::GFP by BamHI and StuI digestions. The fragments of extracellular malectin-like domain (ECD) of LET1 (LET1ECD, 1-400aa) and the extracellular juxtamembrane (exJM) of LET1 (LET1exJM, 338-400aa) were amplified by PCR and cloned into the vector of pHBT-HA or a modified Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein expression vector pGSTu by BamHI and StuI digestion to generate the constructs of pHBT-LET1ECD-HA and pGSTu-LET1exJM. The p35S::HA-LLG1 construct in plant expression vector was obtained from Dr. Alice Cheung28. The fragment of LLG1 without signal peptide (△SP, 25-168aa) was amplified by PCR and digested by BglII and PstI, then ligated with a linearized maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion protein expression vector pMAL (New England BioLabs, USA) by BamHI and PstI digestion to generate pMAL-LLG1△SP. LET1CD (1273-2502 bp) was amplified by PCR from pHBT-35S::LET1-HA using the primers containing StuI at the 5′ end and KpnI at the 3′ end and cloned into an insect cell expression vector pAcGHLT-C to generate pAcGHLT-LET1CD 49 LET2ex (64-1320 bp) and LET2CD (1390-2640 bp) were amplified by PCR from pHBT-35S::LET2-HA using the primers containing BamHI at the 5′ end and HindIII at the 3′ end and cloned into pET28 to generate pET28- LET2ex and pET28- LET2CD.

All the primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 1. The sequences of all genes and mutation were verified by the Sanger-sequencing. The binary plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 and introduced into Arabidopsis using the floral dipping method. Transgenic plants were selected by Glufosinate-ammonium (Basta, 50 μg/mL) for the pCB302 vector and hygromycin (50 μg/mL) for the pMDC32 vector. Multiple transgenic lines were analyzed by immunoblot (IB) for protein expression.

Agrobacterium-mediated virus-induced gene silencing assay

The binary TRV vector pTRV-RNA1 and pTRV-RNA2 derivatives, pTRV-MEKK1, pTRV-CLA1, and pTRV-GFP (the vector control), were transferred into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electroporation. Positive transformants were selected on LB plates containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin and 25 µg/mL gentamicin by incubating at 28 °C for 36 h. An individual transformant was transferred into 2 mL LB liquid medium containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin and 25 µg/mL gentamicin in 20 mL glass culture tubes for overnight at 28 °C in a roller drum, and sub-cultured in 100 times of volume of fresh LB liquid medium containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin, 25 µg/mL gentamicin, 10 mM MES, and 20 µM acetosyringone for overnight at 28 °C with 200 rpm shaking. Cells were pelleted by 1300 g centrifugation, re-suspended in buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, and 200 μM acetosyringone, adjusted to OD600 of 1.5 and incubated at 25 °C for at least 3 h. Bacterial cultures containing pTRV-RNA1 and pTRV-RNA2 derivatives were mixed at a 1:1 ratio and inoculated into the first pair of true leaves of 2-week-old soil-grown plants using a needleless syringe.

Transient expression in Arabidopsis protoplasts

The indicated pHBT constructs were used for protoplast transfection following the protocol58. Briefly, for Co-IP assay, 100 μL of plasmid DNA (2 µg/µL) was mixed with 1 mL of protoplasts (2 × 105 cells/mL) for the PEG-mediated transfection.

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

Proteins were expressed overnight in Arabidopsis protoplasts or N. benthamiana leaves for 3 days. Protoplasts were lysed by vortexing and leaves were grounded in the extraction buffer (100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 2 mM NaF, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, and 1 x protease inhibitor). After centrifugation at 12,500×g at 4 °C for 15 min, 250 μL of extraction buffer were added to dissolve pellets, and 20 μL of supernatant were collected for input controls, and the remaining was incubated with α-FLAG affinity beads (Sigma, USA) at 4 °C for 2 h with gentle shaking. Beads were collected and washed three times with washing buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100), and once with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. Proteins were eluted by 2 × SDS-PAGE loading buffer and boiled at 94 °C for 5 min. Immunoprecipitated and input proteins were analyzed by immunoblot with indicated antibodies.

Trypan blue and DAB staining

For investigating cell death and H2O2 accumulation in leaves, the cotyledons or leaves were detached and soaked into 2.5 mg/mL trypan blue solution (the powder of trypan blue was dissolved in lactophenol with 1:1:1:1 ratio of lactic acid, glycerol, liquid phenol, and ddH2O) or DAB solution (1 mg/mL DAB dissolved in ddH2O, pH 3.8) for overnight incubation. Samples were then destained by trypan blue destaining solution (the mixture of lactophenol and ethanol with 1:2 ratio) or DAB destaining solution (the mixture of glycerol, acetic acid and ethanol with 1:1:3 ratio) respectively with gentle shaking at 70 rpm at room temperature for 1 day. The samples were observed and recorded under a dissecting microscope.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis

Plant total RNAs were extracted by TRIzol reagent (Sigma/Invitrogen, USA). Genomic DNA was degraded by treatment with RNase-free DNase I (NEB, USA). Complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were synthesized with M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (NEB, USA) and oligo(dT) primers. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed by iTaq Universal SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad, USA) with a Bio-Rad CFX384 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, USA). UBQ10 was used as an internal reference.

Recombinant protein isolation from E. coli and in vitro pull-down assay

Fusion proteins were produced from E. coli BL21 at 16 °C using LB medium with 0.25 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). HIS-SUMO-LET2ex and HIS-SUMO-LET2CD were purified with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen, USA). GST and GST-LET1exJM fusion proteins were purified with Pierce glutathione agarose (Thermo Scientific, USA), and MBP-LLG1 fusion proteins were purified using amylose resin (New England Biolabs, USA) according to the standard protocol from companies. MBP-LLG1 proteins were incubated with GST or GST-LET1exJM in the pull-down buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100) for 1 h with gentle shaking, subsequently incubated with 20 μL of glutathione agarose beads at 4 °C for another 2 h with gentle shaking. Beads were washed five times with pull-down buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.2% Triton X-100). Beads were boiled in 50 μL of 2x SDS protein loading buffer for 10 min and detected by immunoblotting with an α-MBP or α-GST antibody. For HIS fusion protein pull-down assay, about 10 μg of HIS-SUMO-LET2ex or HIS-SUMO-LET2CD proteins were mixed with the LET1-FLAG cell lysates in the IP buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.5% Triton X-100) at 4 °C for 30 min with gentle shaking, subsequently incubated with 20 μL of Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen, USA) at 4 °C for another 30 min with gentle shaking. The beads were harvested by centrifugation and washed five times with the IP buffer and one time with washing buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazol). The pull-down proteins were eluted by 50 μL of elution buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 250 mM imidazole) and detected by an immunoblot with an α-FLAG antibody.

In vitro kinase assay

The in vitro kinase assays were performed with 0.5 μg fusion proteins of GST, HIS-GST-LET1CD or HIS-SUMO-LET2CD in 20 μL of kinase reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 1 μL [γ-32P] ATP). After gentle shaking at room temperature for 2 hr, samples were denatured with 4x SDS loading buffer and separated by 10% SDS-PAGE gel. Phosphorylation was analyzed by autoradiography. For immunocomplex kinase assay, GFP-FLAG, LET1-FLAG, or LET1KM-FLAG were transiently co-expressed with LET2-HA or LET2KM-HA in protoplasts for 10 h, and purified by α-FLAG agarose. The proteins were incubated with 20 μL of kinase reaction buffer at room temperature for 3 hr with gentle shaking. The reactions were stopped by adding 4× SDS protein loading buffer. The phosphorylation of proteins was analyzed by autoradiography after separation with 10% SDS-PAG.

Confocal Microscopy and FLIM-FRET assays

The GFP and mCherry fusion proteins were detected using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal laser scanning microscope (Germany). The GFP fluorescence was excited at 488 nm, and emissions were detected between 490 and 530 nm. The mCherry fluorescence was excited at 587 nm, and emissions were detected between 590 and 620 nm. The pinhole was set at 1 Airy unit. Images and FLIM/FRET analyses were performed by using Leica Application Suite X (LAS X) software as described59. Briefly, FRET measurements were done with a pair of GFP/mCherry fusion proteins. The image of GFP donor fluorescence was analyzed and scanned at 488 nm and detected between 490 and 530 nm. The fluorescence lifetime (τ) was calculated as the average of 20τ values randomly measured in the protoplast cells. The values obtained for 15 protoplasts were used to determine the average value of τ for each pair of proteins analyzed. The relative fluorescence intensity (I) in a certain region of interest (ROI), lifetime (τ) and FRET efficiency were measured by the Leica LAS X software. FRET efficiency (E) was calculated by using the formula E = 1-(τDA/τD), τDA is the lifetimes of the donor in the presence of acceptor and τD is fluorescence lifetime of the donor alone.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC) for Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion library and various mutant seeds, Drs. Alice Cheung (University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA), Patrick Krysan (University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA), Yanhai Yin (Iowa State University), Dingzhong Tang (Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, China), Lijia Qu (Peking University, China), and Yuelin Zhang (University of British Columbia, Canada) for Arabidopsis seeds and constructs, Tanja Pfeiler, Doris Keck and Peter Stasnik for genotyping the MDS CRISPR/Cas mutants, and members of the laboratories of L.S. and P.H. for discussions and comments of the experiments. The work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01GM092893) and National Science Foundation (NSF) (MCB-1906060) to P.H., NIH (R01GM097247) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (A-1795) to L.S, PEW Latin American Fellows Program to F.A.O.M., and the Austrian Science Fund project FWF I 1725-B16 to M.T.H. Y.H., C.Y., and D.G. were partially supported by China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Source data

Author contributions

Y.H., C.Y., J.L., L.S., and P.H. conceived the project, designed experiments and analyzed data. Y.H., C.Y., J.L., B.F., D.G., L.K. and F.A.O.M. performed experiments and analyzed data. J.R., and M.T.H. generated mds CRISPR/Cas lines. W.M.W. analyzed data and provided critical feedback. Y.H., L.S., and P.H. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all co-authors.

Data availability

The source data for Figs. 1 and 3–7 and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 6–7 are provided as a Source Data File. Other original data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yanyan Huang, Chuanchun Yin, Jun Liu.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-18600-8.

References

- 1.Couto D, Zipfel C. Regulation of pattern recognition receptor signalling in plants. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16:537–552. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu X, Feng B, He P, Shan L. From chaos to harmony: responses and signaling upon microbial pattern recognition. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2017;55:109–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080516-035649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gust AA, Pruitt R, Nurnberger T. Sensing danger: key to activating plant immunity. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22:779–791. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jamieson PA, Shan LB, He P. Plant cell surface molecular cypher: receptor-like proteins and their roles in immunity and development. Plant Sci. 2018;274:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohm H, Albert I, Fan L, Reinhard A, Nurnberger T. Immune receptor complexes at the plant cell surface. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014;20:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui H, Tsuda K, Parker JE. Effector-triggered immunity: from pathogen perception to robust defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015;66:487–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elmore JM, Lin ZJ, Coaker G. Plant NB-LRR signaling: upstreams and downstreams. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011;14:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeYoung BJ, Innes RW. Plant NBS-LRR proteins in pathogen sensing and host defense. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:1243–1249. doi: 10.1038/ni1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiu SH, Bleecker AB. Expansion of the receptor-like kinase/Pelle gene family and receptor-like proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:530–543. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belkhadir Y, Yang L, Hetzel J, Dangl JL, Chory J. The growth-defense pivot: crisis management in plants mediated by LRR-RK surface receptors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014;39:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohmann U, Lau K, Hothorn M. The structural basis of ligand perception and signal activation by receptor kinases. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017;68:109–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042916-040957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nissen KS, Willats WG, Malinovsky FG. Understanding CrRLK1L function: cell walls and growth control. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:516–527. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li C, Wu HM, Cheung AY. FERONIA and her pals: functions and mechanisms. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:2379–2392. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindner H, Muller LM, Boisson-Dernier A, Grossniklaus U. CrRLK1L receptor-like kinases: not just another brick in the wall. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012;15:659–669. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franck CM, Westermann J, Boisson-Dernier A. Plant malectin-like receptor kinases: from cell wall integrity to immunity and beyond. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018;69:301–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escobar-Restrepo JM, et al. The FERONIA receptor-like kinase mediates male-female interactions during pollen tube reception. Science. 2007;317:656–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1143562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan Q, Kita D, Li C, Cheung AY, Wu HM. FERONIA receptor-like kinase regulates RHO GTPase signaling of root hair development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:17821–17826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005366107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, et al. FERONIA interacts with ABI2-type phosphatases to facilitate signaling cross-talk between abscisic acid and RALF peptide in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E5519–E5527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608449113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boisson-Dernier A, et al. Disruption of the pollen-expressed FERONIA homologs ANXUR1 and ANXUR2 triggers pollen tube discharge. Development. 2009;136:3279–3288. doi: 10.1242/dev.040071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyazaki S, et al. ANXUR1 and 2, sister genes to FERONIA/SIRENE, are male factors for coordinated fertilization. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1327–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]