Abstract

ASCO strives, through research, education, and promotion of the highest quality of patient care, to create a world where cancer is prevented and every survivor is healthy. In this pursuit, cancer health equity remains the guiding institutional principle that applies to all its activities across the cancer care continuum. In 2009, ASCO committed to addressing differences in cancer outcomes in its original policy statement on cancer disparities. Over the past decade, despite novel diagnostics and therapeutics, together with changes in the cancer care delivery system such as passage of the Affordable Care Act, cancer disparities persist. Our understanding of the populations experiencing disparate outcomes has likewise expanded to include the intersections of race/ethnicity, geography, sexual orientation and gender identity, sociodemographic factors, and others. This updated statement is intended to guide ASCO’s future activities and strategies to achieve its mission of conquering cancer for all populations. ASCO acknowledges that much work remains to be done, by all cancer stakeholders at the systems level, to overcome historical momentum and existing social structures responsible for disparate cancer outcomes. This updated statement affirms ASCO’s commitment to moving beyond descriptions of differences in cancer outcomes toward achievement of cancer health equity, with a focus on improving equitable access to care, improving clinical research, addressing structural barriers, and increasing awareness that results in measurable and timely action toward achieving cancer health equity for all.

INTRODUCTION

ASCO is the national organization representing more than 45,000 physicians and other health care professionals specializing in cancer treatment, diagnosis, and prevention. ASCO members are also dedicated to conducting research that leads to improved cancer outcomes and ensuring that evidence-based practices are available to their patients and the communities they serve. Since 2003, ASCO has had a formal body of volunteers composed of cancer health disparities and health equity experts who have focused on improving our understanding, advancing our scientific knowledge, and developing solutions to eliminate disparities in cancer.

In 2013, ASCO established a standing Health Disparities Committee, and in 2018, the ASCO board approved the committee’s request to change its name to reflect the evolution from reporting on differences among populations to one focused on achieving health care equity. Now known as the Health Equity Committee (HEC), this group is charged with guiding the society’s strategic priorities to improve health equity across the cancer care continuum through collaboration within ASCO as well as with other cancer care stakeholders nationally and internationally.

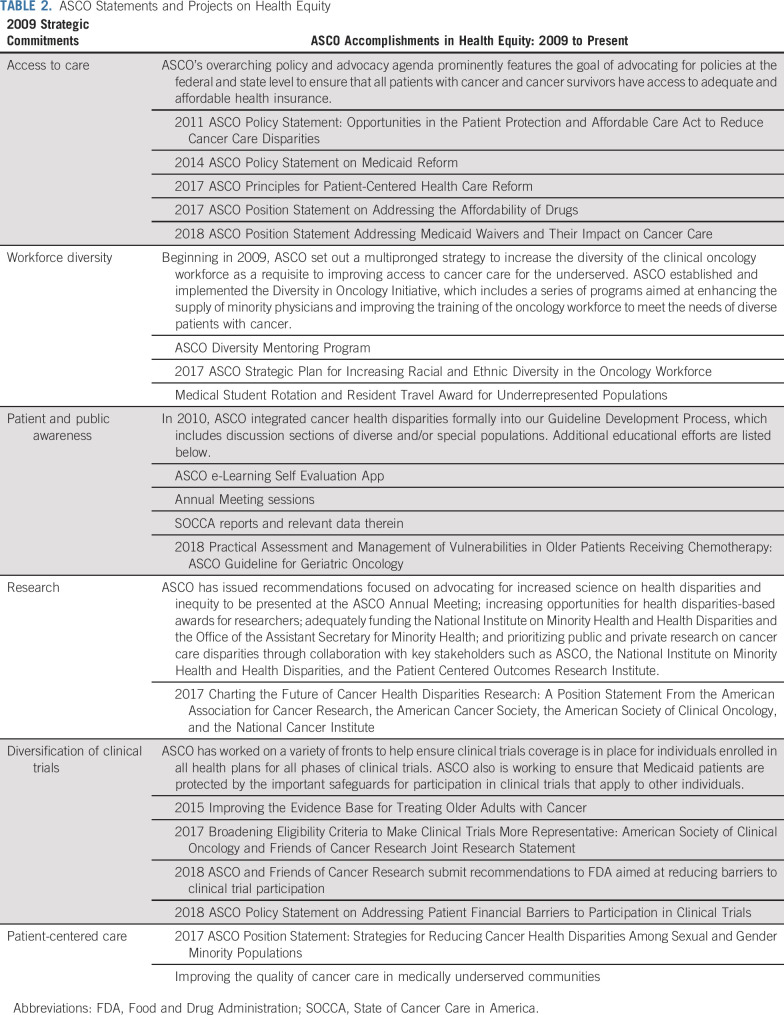

The first ASCO Policy Statement on Cancer Care Disparities was published in 2009.1 It affirmed ASCO’s commitment to addressing disparities in cancer care and laid out a comprehensive set of strategic commitments across three broad areas: enhancing awareness, improving access to care, and supporting research on health disparities. This new statement presents recommendations based on an updated review and analysis of health equity in cancer care, intended to lead ASCO into the future by focusing on four key areas (Table 1): (1) to ensure equitable access to high-quality care, (2) to ensure equitable research, (3) to address structural barriers, and (4) to increase awareness and action.

TABLE 1.

ASCO Recommendations for Promoting Health Equity

DEFINITIONS

Cancer health disparities describe the measurable differences in cancer outcomes in various population groups. When the United States began collecting cancer data in January 1973 through the SEER program,2 differences among populations became apparent in terms of incidence, prevalence, stage at diagnosis, morbidity, and mortality. As SEER and other population data grew more robust, variations in screening, survivorship, quality of life, and compounding health conditions were also observed. Over time, the analytic context of research on health disparities in the United States expanded to include race and ethnicity, age, sexual orientation and gender identity, education, socioeconomic status, insurance access and type of insurance, environmental exposures, and geography, among other factors.

Health equity contextualizes health disparities through a lens of historical and social hierarchy and requires action to remedy injustice and improve health. Health equity is defined as everyone having a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible, an ethical and human rights principle that motivates us to eliminate health disparities.3 In this view, health disparities are the preventable results of structural discrimination and marginalization, which, if left unaddressed, will continue to reinforce social and economic inequities, bias, and poor outcomes that affect us all.4 The concept of cancer health equity acknowledges that much work needs to be done to overcome the historical momentum and the existing social structures responsible for disparate cancer outcomes and that this work can achieve its goal only through collaborative efforts with the communities involved. For ASCO, cancer health equity is a guiding institutional principle that that we strive to apply to all ASCO activities across the cancer care continuum, from advocacy to research to the development of learners and leaders.

STATE OF CANCER DISPARITIES IN THE UNITED STATES

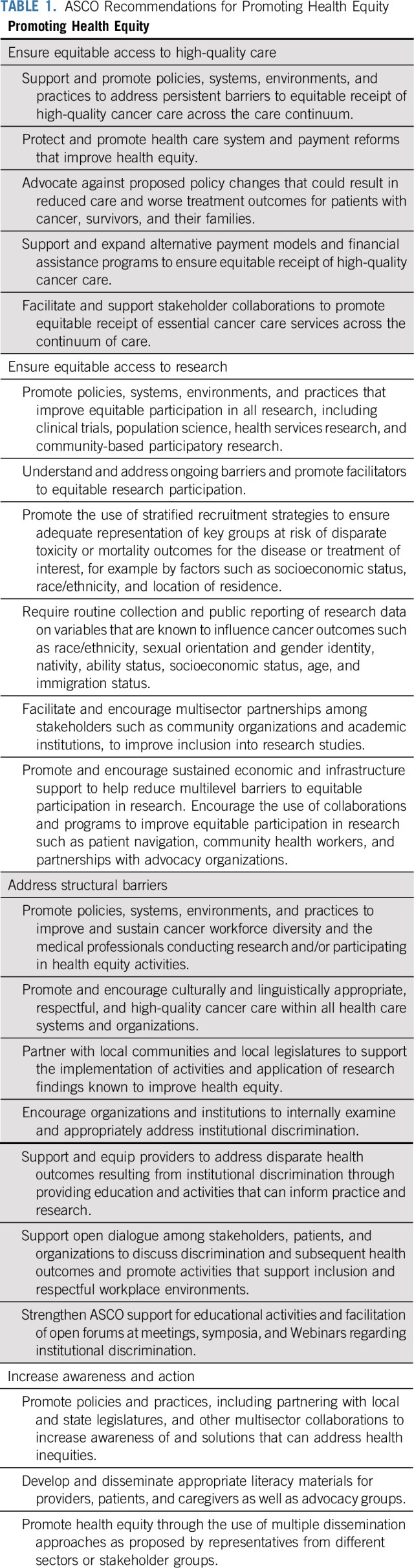

ASCO’s 2009 policy statement focused on key recommendations1 to address cancer disparities. Subsequent to these recommendations, ASCO issued several position statements and enacted programs intended to reduce cancer disparities (Table 2). Although it is difficult to assess the impact of ASCO’s efforts on cancer health disparities overall, outputs from these programs demonstrate their success in addressing previously unmet health professional educational needs. For example, nearly 3,000 oncology professionals have completed ASCO’s online educational courses in cultural literacy and cancer health disparities since they became available in 2016. ASCO’s Annual Meeting has increased workforce diversity– and health disparities–related content more than 5-fold in the past 10 years, and ASCO’s patient-facing online content, Cancer.Net, has likewise expanded to include disparities-related patient education in both English and Spanish. To connect medical students and trainees from historically underrepresented minority groups with oncologists who can provide career and educational guidance, ASCO developed a Diversity Mentoring Program. It was launched in 2013, and it provided one-on-one mentoring opportunities for more than 22 trainees during its most recent year. Other programs include ASCO’s Diversity in Oncology Initiative, which has provided more than $1 million in grant and funding support for clinical research led by historically underrepresented minority trainees to attend and present their research at ASCO’s Annual Meeting. By developing a cadre of health professionals with cancer health equity expertise, ASCO members are witnessing and benefitting from the needle moving forward as evidenced by the increased dissemination of evidence-based programming in cancer health disparities research at ASCO’s Annual Meeting and in the corresponding annual Educational Book.

TABLE 2.

ASCO Statements and Projects on Health Equity

Nevertheless, despite efforts over the past decade by policymakers and stakeholders, including ASCO, to equalize cancer outcomes, gaps in cancer incidence, treatment, and mortality remain. These inequalities endure within and across multiple cancer diagnoses and population groups. Variations in cancer outcomes continue to be associated with factors such as race/ethnicity, sexual orientation and gender identity, age, geography (eg, rural v urban), socioeconomic status, and health literacy, among many others.5 The intersection of multiple demographic characteristics is also important when evaluating cancer outcomes. The negative impact on cancer outcomes for a given population may be masked when demographic factors are evaluated individually.6,7 Approaches that examine how multiple dimensions of a person’s identity intersect to affect health outcomes are needed to develop effective strategies for reducing cancer disparities.8-10

Over the past decade, progress in cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment has reduced overall cancer mortality in the United States.11 This progress, however, remains inequitably distributed and in some cases poorly characterized across demographic subgroups. For example, Black men and women,6,12 patients living in rural areas,13 and populations with lower income and education levels14,15 continue to experience worse survival for many cancers regardless of stage at diagnosis. These disparate outcomes are compounded when examined through the lens of multiple social factors. For example, although lung cancer rates have declined among Black men overall, among those living in rural areas, incidence and mortality rates surpass those of all other populations.6,16 For some subpopulations, notably sexual and gender minorities, suboptimal access to cancer care and lack of consistency in data collection have made it challenging to evaluate the impact of any gains observed overall.17

The etiologies for these persistent and widening gaps in cancer outcomes across the cancer care continuum from prevention to diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, and care at the end of life, are multifactorial and include many systems-level factors.18 If these etiologies are not addressed now, cancer disparities will continue to persist and may, in fact, worsen. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to disrupted access to health services, including many cancer care services. This disruption seems to be disproportionately experienced by those who face current health inequities, highlighting longstanding barriers to achieving health equity within our health care delivery system. Therefore, to achieve cancer health equity, significant long-term investment, ongoing efforts, strategic initiatives, and strengthened and new collaborations among stakeholders and organizations such as ASCO, cancer stakeholders, policy makers (local, state, and federal), and broader society are required.

ASCO RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PROMOTING HEALTH EQUITY: RECOMMENDATIONS TO ACHIEVE HEALTH EQUITY IN THE NEAR AND LONG TERM

Ensure Equitable Access to High-Quality Care

High-quality cancer care across the care continuum, from prevention, early detection, diagnosis, and treatment to survivorship and end-of-life care, can reduce and in some cases eliminate cancer disparities.19 However, variations in the quality and delivery of cancer care remain a significant barrier to cancer health equity,20 especially as novel and more efficacious innovations such as targeted and immune therapies and technology emerge but remain inequitably delivered. Achieving delivery of high-quality cancer care that is accessible to all requires the engagement of every stakeholder, including those engaged in direct practice, research, education, industry, health care organization, economics, and policy. Efforts to preserve access to health insurance, given the integral link to health care access, can improve cancer health outcomes.21

In 2010, the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was intended to ensure access to comprehensive health insurance. As part of the statute, persons can no longer be denied health insurance coverage because of preexisting conditions, and small group and individual health plans are required to cover a package of essential health benefits that include cancer screening.22,23 The ACA also mandates that private insurance plans cover the routine costs of clinical trials, a policy that had been in place for Medicare since late in the year 2000. This policy is important because of its inclusion of clinical trials in the standard of care for advanced cancers, the absence of which remains a critical coverage gap to this day for many Medicaid programs.24 The ACA provides states with the option to expand Medicaid coverage to include childless adults earning annual incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level. The expansion of Medicaid, formerly limited to impoverished pregnant women or disabled persons, holds great promise to reduce barriers to individual access to health care. The optional nature of Medicaid expansion at the state level, however, has led to state-based variations in progress toward achieving cancer health equity.25 States that chose to expand Medicaid, for example, experienced significant coverage gains and reductions in uninsured rates among low-income and other populations, and improved access to, and affordability of, care and cancer screening services.25 Cancer outcomes improved in Medicaid expansion states and worsened in states that chose not to expand.26 Other challenges to achieving the intended goals of the ACA and removing barriers to accessing high-quality cancer care include the enactment of various restrictions and requirements for Medicaid beneficiaries that could have a negative impact on cancer outcomes.27 Although more mature research on the impact of Medicaid expansion on cancer outcomes is needed, the evidence to date indicates that the uneven expansion of Medicaid may create a new avenue for geographic disparities between patients with access to expanded coverage and those without.28

Individuals with private or employer-based insurance coverage also experience challenges regarding access to high-quality cancer care. Rising health care premiums, high-deductible insurance plans, and narrowed networks29,30 are linked to delays in cancer care, delays that adversely affect cancer control and survival.31 A similar pattern will likely emerge in conjunction with the discontinuity of employer-based insurance and short-term coverage for those who lose employment or are employed as “gig” workers or temporary and/or independent contractors. The projected and unsustainable rise in total cancer costs and the resulting economic strain on society, patients, and families will exacerbate the barriers preventing access to high-quality cancer care. Although the risk is greatest for populations currently without access and those who are at risk of lack of access, the anticipated economic strain caused by rising cancer health costs threatens everyone.

ASCO remains strongly committed to the elimination of barriers to access and payment coverage across the continuum of cancer care through policy reforms and advocacy. First steps should include the full expansion of Medicaid in every state, in addition to the expansion of alternative payment models to include incentives that promote access for those populations most at risk of experiencing cancer health inequities across the cancer care continuum. Stakeholders should collaborate to promote the mandatory coverage of essential cancer care services from prevention to diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, and care at the end of life, as well as the expansion of alternative payment models, incentives, and other programs and strategies that can improve equitable high-quality cancer care access across the continuum of care.

Financial toxicity is particularly important for patients with limited financial resources who may be at risk of disproportionate harm because of cost-containment strategies deployed in oncology care. ASCO supports the appropriate implementation of novel programs that contain cancer care costs and emphasize high-value care, but with appropriate safeguards to ensure that such interventions are benefitting, rather than harming or restricting, care access for patients with public insurance or limited financial resources. Accountable care organizations (ACOs), for example, can improve access to high-value cancer care services. However, ACOs are limited to patients in a small minority of states across the United States and vary in the comprehensiveness of services they cover.32,33 Other steps such as payer-provider collaborations that incentivize high-value cancer care services among low-income, elderly, and minority patients have recently been undertaken to lessen place-based geographic disparities; these steps also include rural access to care or financing for known interventions that can reduce disparities (eg, telephone-based health interventions).34,35 These collaborations can also address access to care by financing aspects of health equity, such as housing, transportation, childcare, and food, that fall outside of the traditional medical sector but can affect appropriate cancer care delivery. One such payer-provider collaboration is currently being tested in a randomized study to determine the impact on cancer health disparities.36 In conjunction with state Medicaid programs and ACOs, novel collaborations and payment models should be prioritized to ensure financing for known interventions that can reduce disparities.

Ensure Equitable Access to Research

As cancer care becomes more complex and personalized, the research through which new advances are developed must include the representation of all populations who stand to benefit. Given the lack of access to basic, evidence-based care among many populations,19 gains in achieving health equity will be limited if novel advancements continue to be developed via research that does not include representation from all populations. All populations should have an equal opportunity to participate in, be recognized for, and benefit from research across the spectrum, including clinical trials, health services research, and other types of research studies and methodologies. Stakeholders, including patients, caregivers, providers, policy leaders, pharmaceutical organizations, and advocacy groups, can work together to develop appropriate targeted approaches to achieve this goal. For example, although single-institution studies exploring efforts to improve health equity, such as access to clinical trials,37 may be limited in their generalizability, the publication of such efforts can be invaluable in laying the groundwork for broader health equity improvements. Therefore, the peer review process and publication of such studies must be identified as valuable. Research sponsors, journals, and scientific meetings should prioritize the publication of these studies to enable subsequent broader implementation of promising interventions that can improve cancer health equity.

Routine collection and reporting of data regarding demographic and clinical characteristics can increase the likelihood that research will acknowledge and potentially address health disparities.38 All studies should routinely collect and publicly report aggregated data on demographic and clinical factors (including race/ethnicity, sexual orientation and gender identity, nativity, ability status, socioeconomic status, age, immigration status, and stage of disease, comorbidities, and treatment, among others) because such data elements are necessary to understand differences in treatment effectiveness, tolerance, and outcomes. Researchers should be encouraged to use recruitment strategies that ensure adequate representation of populations afflicted with the disease being studied and those at risk of disparate outcomes, including, but not limited to, populations with diverse socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and geographic location (urban/rural).

To drive equitable inclusion into research, health care professionals and stakeholders should engage in meaningful and ongoing partnerships with private and public entities, academic and community practices, patients, caregivers, advocacy groups, and other organizations. Such efforts would include understanding the existing barriers to, and potential facilitators for, research participation in underrepresented communities and populations. Novel strategies include informed consent methods that are more accessible to participants from a wide range of cultural and linguistic backgrounds such as multimedia consent content with concise text blocks, visual icons, and videos on smartphone-optimized Web interfaces.39,40 Social media and use of patient-centered recruitment messaging is also gaining traction in assisting with recruiting patients for clinical research who may traditionally have been underrepresented.41 Other programs that have improved inclusion in research include patient navigation, efforts led by community health workers, and partnerships with community and advocacy organizations. Such efforts can assist with overcoming other known barriers to participation in research, such as transportation and childcare. These approaches, among others, should be incorporated into strategies to improve the recruitment and retention of diverse participant representation in research.42-44 Organizations should also provide and sustain research funding and infrastructure support to achieve these goals.

Organizations should also work to assist clinicians and other stakeholders to achieve equitably diverse representation in research, such as through meetings and symposia. To achieve the recommendations in this section, there is also a need for a quality data management infrastructure to support research activities, broaden the inclusion criteria of clinical trials and other research, address financial barriers to participation in research, and promote access to research in underrepresented areas.

Address Structural Barriers

Structural barriers refer to societal conditions such as interpersonal, institutional, and systemic drivers that preserve and promote health inequities. The structures that make up the cancer care delivery system include the cancer care team, the larger health care organizations (including payers and hospital systems), and the political and economic environment surrounding the health care system. At present, many factors and forces across these structures contribute to inequities in cancer outcomes. Overcoming these barriers requires a commitment to mitigating explicit and implicit bias through commitment to workforce diversity, development and strengthening of community partnerships, and addressing institutional discrimination.

Workforce diversity.

In 2009, ASCO prioritized programs focused on improving diversity in the cancer care workforce.45 One important solution to reduce health disparities lies in improving diversity and inclusion in the care delivery and biomedical cancer research workforce.46 Less than 9% of active physicians in the United States identify as Black, Hispanic, American Indian, or Alaska Native.47 These figures are worse for practicing oncology specialists, with less than 6% self-identifying as Hispanic and less than 3% self-identifying as Black.48 Workforce disparities are also reflected among health researchers, few of whom identify as nonwhite,49 which results in additional downstream effects that can have a chilling effect on research into health equity. For example, inequitable research funding remains a barrier for Black researchers, who are less likely than White researchers to be funded by the National Institutes of Health. One of the underlying causes of this funding gap is driven by research topic. Specifically, research focused on the community and population level, such as health equity research, which Black investigators are more likely to propose, is much less likely to be funded than is research focused on cellular and molecular science.50 Nevertheless, ASCO remains committed to improving the diversity of the workforce. ASCO will continue efforts in this regard through its Diversity and Inclusion Task Force, charged with developing recommendations and proposals for ASCO to achieve its diversity and inclusivity goals. In addition, ASCO will continue its efforts to achieve the goals of the board-approved ASCO Strategic Plan to Increase Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the Oncology Workforce and the Women in Oncology Strategic Plan.45

Institutions involved in cancer care can conduct a variety of activities to address persistent concerns regarding workforce diversity. Organizations should expand the focus of workforce diversity and inclusion to increase the number of professionals who are conducting and/or participating in cancer health equity research, providing care to populations at risk of cancer health inequities, and performing other cancer health equity activities. Organizations should also provide ongoing educational opportunities, funding opportunities, and infrastructure support to encourage and sustain health equity practice and research as a viable career focus and to remove barriers that tend to disproportionately discourage underrepresented groups from remaining in the research workforce. Stakeholder and professional organizations should create a variety of ongoing educational opportunities to ensure that the professional workforce has the necessary methods and training with which to achieve cancer health equity through practice and research. These include workshops, open forums, and virtual mentorship opportunities. Organizations should commit to providing and sustaining funding opportunities and infrastructural support for professional involvement in health equity activities and research. Such opportunities include ongoing research funding to include a health equity focus, such as expanding calls for merit and young investigator and career development awards that specifically support the professional workforce who are interested in and/or currently conduct health equity research.

Community partnerships.

Achieving cancer health equity requires broad approaches that address the social, economic, and environmental factors that influence health. The social determinants of health, which are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age and factors such as socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood, employment, and social support, should be addressed, in addition to access to health care. Addressing the social determinants of health is critical to achieving health equity, and community-engaged strategies are an essential way to do so.51,52 To achieve the goal of cancer health equity, professional organizations must partner with community organizations to support communities in health promotion activities over the lifespan. Community efforts may address multiple conditions that are important drivers of health and wellness, including safe, physical environments and neighborhoods that promote health; access to early, high-quality education; affordable housing; structurally safe sidewalks; open spaces, such as parks; access to recreation centers; and clean drinking water, food, and transportation.

ASCO supports policies and practices that address the social determinants of health. Multisector collaborations can help promote and sustain health equity. In addition, attention should be paid to local capacity building to improve health equity. Such efforts to enhance community capacity building include partnering with and expanding collaboration with local health professionals and health care teams, community health workers, and other community leaders. These efforts can assist in identifying strategies to address the social determinants of health and can promote and sustain the infrastructure, policies, and implementation activities that are crucial to reducing disparities.53,54 Importantly, the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Center Support Grants renewal process now explicitly includes requirements related to catchment area (eg, related to clinical trial recruitment populations) and community outreach and engagement. ASCO encourages other institutions to similarly prioritize health equity in these requirements to better fund and enable lasting relationships with community partners. Partnering with communities is key to understanding how best to support local programs and research led by the community to improve cancer health equity. Such partnerships can lead to state and local legislative action, which can help improve health equity locally.

Addressing institutional discrimination.

Institutional discrimination through implicit and explicit biases, institutional structures, and interpersonal relationships supports health inequities and adversely affects health outcomes.55,56 Disparities caused by inequitable institutional and geographic distribution of high-quality cancer care have a significant and negative impact on health and well-being. All health systems should promote access to socially, culturally, and linguistically appropriate, respectful, and high-quality cancer care. Health systems and health care professionals should embrace, respect, and welcome the opportunity to deliver high-quality cancer care to all patients and families.

To address systemic variations in the delivery of high-quality cancer care for all patients and families, health systems and institutions should conduct ongoing root cause analyses to understand and address cancer outcome disparities. Such analyses should use patient-level quality measures to identify institution-specific gaps or variations in care delivery and outcomes that are caused at the systems-level by factors such as race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, insurance status, and neighborhood, among others. Health systems should also integrate the role of intersectionality (defined as the intersection of an individual’s many identities and/or dimensions) on discrimination and subsequent health outcomes.57 All institutions, organizations, and health care professionals should respect and welcome the conduct of these introspection opportunities to change their organizations and practices.

All health systems, organizations, and cancer care professionals should be adequately and appropriately prepared to address the disparate health outcomes resulting from institutional discrimination, to examine their own biases, and to participate in activities that can inform and ensure more respectful, equitable practices, research, and workplace environments. Institutions and organizations should facilitate opportunities for safe, open forums and activities that allow discussion internally regarding the effect of institutional discrimination on health, respect, and respectful care for patients and families, as well as their own staff. Activities that directly expose the impact that institutional discrimination has on longitudinal health outcomes should be continued and expanded. Any implicit and explicit bias toward patients, families, and staff should be acknowledged and addressed by the institution. All institutions and organizations should respect and embrace these internal quality-assurance assessments, introspection, and discussion to create a safe, respectful medical home for patients and families and workplace environment for staff. ASCO will continue to advocate for policies and programs that support the elimination of institutional discrimination.

Educational activities and open forums provide critical opportunities to examine, discuss, and consider solutions to the effect of implicit and explicit biases on cancer health equity and the quality of cancer care delivery. Online educational portals can be developed and in-person educational sessions can be held at meetings and symposia to directly address the topic of institutional discrimination and its impact on cancer outcomes.

Increase Awareness and Action

Achieving health equity requires efforts that inform, educate, and empower all individuals. Continued efforts to ensure awareness are crucial for the general public, health care professionals, policy makers, health systems, and other stakeholders. Increasing awareness of health inequities is insufficient by itself; however, when accompanied by the recommendations in this statement, awareness can lead to additional actions necessary to achieve cancer health equity. Although awareness of cancer health inequities has improved modestly over the past decade, educational efforts should extend to those policies, programs, activities, and research that have proven successful at ameliorating cancer health inequities.

Public awareness and information campaigns require multisector organizations and stakeholders to ensure awareness of cultural literacy, as well as provide appropriate literacy materials58,59 that are freely accessible to health professionals, patients, and caregivers, health systems, and advocacy groups. Dissemination activities such as annual meetings, online Webinars, and print media should include information on health inequities and ways to improve those inequities. Partnerships among patients and advocacy groups should aim to disseminate this information to the general public.

As a follow-on effort to developing this updated policy statement on cancer health equity, ASCO’s HEC has begun preliminary work on a Strategic Plan to address ASCO’s role in carrying out these new recommendations. This Strategic Plan will ensure the integration of health care equity into ASCO’s efforts to conquer cancer through research, education, and the promotion of the highest quality of patient care and will incorporate measurable goals into program design whenever possible.

ASCO and the cancer care community as a whole have made important progress in the past 10 years in addressing health care disparities. This policy statement describes past activities that ASCO has undertaken to improve multiple areas of the health care system, including education, quality of care, workforce diversity, and research. However, ongoing and persistent cancer disparities motivate ASCO to renew a long-standing commitment to reduce cancer health inequities for all populations, expanding our focus to include factors such as economic inequality, advanced age, sexual and gender minority status, and geographic differences.

CONCLUSIONS

Crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic have brought to national attention the dire consequences of failing to provide accessible, equitable care for all individuals in our society. As we move forward as an organization, we recognize that there is still much work to be done to reduce inequities in cancer care, and we acknowledge the need for measurable programs to assess progress toward cancer health equity. To that end, the ASCO HEC is currently developing a strategic plan to address and help implement the recommendations in this statement over the coming years. The 4 areas of recommendation for future action reflect lessons learned over the decade since our original 2009 statement, and we encourage other cancer care stakeholders to partner with us in moving oncology care closer to achieving our shared goal of cancer health equity.

SUPPORT

Supported in part by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award No. K23MD013474 (M.I.P.).

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

See accompanying editorial on page 3361

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Manali I. Patel, Ana Maria Lopez, Katherine Reeder-Hayes, Allyn Moushey, Jonathan Phillips, William Tap

Administrative support: Allyn Moushey

Collection and assembly of data: Manali I. Patel, Ana Maria Lopez, Allyn Moushey, William Tap

Data analysis and interpretation: Manali I. Patel, Ana Maria Lopez, William Blackstock, Allyn Moushey, William Tap

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Cancer Disparities and Health Equity: A Policy Statement From the American Society of Clinical Oncology

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Manali I. Patel

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene

William Tap

Leadership: Certis Oncology Solutions, Atropos Pharmaceuticals

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Certis Oncology Solutions, Atropos

Consulting or Advisory Role: EMD Serono, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Blueprint Medicines, Agios, GlaxoSmithKline, NanoCarrier, Deciphera

Research Funding: Novartis, Eli Lilly, Plexxikon, Daiichi Sankyo, TRACON Pharma, Blueprint Medicines, Immune Design, BioAtla, Deciphera

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Companion Diagnostic for CDK4 inhibitors - 14/854,329

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goss E, Lopez AM, Brown CL, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: Disparities in cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2881–2885. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White MC, Babcock F, Hayes NS, et al. The history and use of cancer registry data by public health cancer control programs in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:4969–4976. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braveman PA, Arkin E, Orleans T, et al. What Is Health Equity? And What Difference Does a Definition Make? Princeton, NJ: Robert Woods Johnson Foundation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braveman PA, Kumanyika S, Fielding J, et al. Health disparities and health equity: The issue is justice. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:S149–S155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NCI Understanding Cancer Disparities. 2018. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/disparities

- 6.Mariotto AB, Zou Z, Johnson CJ, et al. Geographical, racial and socio-economic variation in life expectancy in the US and their impact on cancer relative survival. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noone A, Miller D, Brest A, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2015. based on November 2017 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2018. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz AJ, Mullings LE. Gender, Race, Class, & Health: Intersectional Approaches. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weber L, Fore ME: Race, ethnicity, and health: An intersectional approach, in Vera E, Feagin FR (eds): Handbooks of the Sociology of Racial and Ethnic Relations. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Boston, MA, Springer 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am Psychol. 2009;64:170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: Progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:290–308. doi: 10.3322/caac.21340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henley SJ, Anderson RN, Thomas CC, et al. Invasive cancer incidence, 2004-2013, and deaths, 2006-2015, in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties—United States. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66:1–13. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6614a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. doi: 10.1155/2011/107497. Singh GK, Williams SD, Siahpush M, et al: Socioeconomic, rural-urban, and racial inequalities in US cancer mortality: Part I-All cancers and lung cancer and Part II-Colorectal, prostate, breast, and cervical cancers. J Cancer Epidemiol [epub ahead of print on February 14, 2012] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. doi: 10.1155/2017/2819372. Singh GK, Jemal A: Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the United States, 1950-2014: Over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J Environ Public Health [epub ahead of print on March 20, 2017] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houston KA, Mitchell KA, King J, et al. Histologic lung cancer incidence rates and trends vary by race/ethnicity and residential county. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:497–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griggs J, Maingi S, Blinder V, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement: Strategies for reducing cancer health disparities among sexual and gender minority populations. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2203–2208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine . Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel MI, Ma Y, Mitchell B, et al. How do differences in treatment impact racial and ethnic disparities in acute myeloid leukemia? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:344–349. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedman RA, He Y, Winer EP, et al. Trends in racial and age disparities in definitive local therapy of early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:713–719. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa048. Yabroff KR, Reeder-Hayes K, Zhao J, et al: Health insurance coverage disruptions and cancer care and outcomes: Systematic review of published research. J Natl Cancer Inst 112:671-687, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davidoff AJ, Guy GP, Jr, Hu X, et al. Changes in health insurance coverage associated with the Affordable Care Act among adults with and without a cancer history: Population-based national estimates. Med Care. 2018;56:220–227. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han X, Yabroff KR, Robbins AS, et al. Dependent coverage and use of preventive care under the Affordable Care Act N Engl J Med 3712341–2342.2014[Erratum: N Engl J Med 373:782, 2015] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winkfield KM, Phillips JK, Joffe S, et al. Addressing financial barriers to patient participation in clinical trials: ASCO policy statement J Clin Oncol[epub ahead of print on September 13, 2018] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jemal A, Lin CC, Davidoff AJ, et al. Changes in insurance coverage and stage at diagnosis among nonelderly patients with cancer after the Affordable Care Act. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3906–3915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adamson BJS, Cohen AB, Estevez M, et al. Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion impact on racial disparities in time to cancer treatment J Clin Oncol[epub ahead of print on June 5, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ASCO . American Society of Clinical Oncology Position Statement Addressing Medicaid Waivers & Their Impact on Cancer Care. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi SK, Adams SA, Eberth JM, et al. Medicaid coverage expansion and implications for cancer disparities. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:S706–S712. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wharam JF, Zhang F, Lu CY, et al. Breast cancer diagnosis and treatment after high-deductible insurance enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1121–1127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wharam JF, Zhang F, Wallace J, et al. Vulnerable and less vulnerable women in high-deductible health plans experienced delayed breast cancer care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:408–415. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eriksson L, Bergh J, Humphreys K, et al. Time from breast cancer diagnosis to therapeutic surgery and breast cancer prognosis: A population-based cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2018;143:1093–1104. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. NAACOS (National Association of ACOs): State ACO Activities. https://www.naacos.com/medicaid-acos.

- 33.Alderwick H, Hood-Ronick CM, Gottlieb LM. Medicaid investments to address social needs in Oregon and California. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:774–781. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitten P, Buis L. Private payer reimbursement for telemedicine services in the United States. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13:15–23. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. https://www.aha.org/news/insights-and-analysis/2019-12-16-provider-payer-collaboration-looks-opportunities-eliminate Bhatt J: Provider-payer collaboration looks at opportunities to eliminate health disparities.

- 36.Patel MI, Khateeb S, Coker T. A randomized trial of a multi-level intervention to improve advance care planning and symptom management among low-income and minority employees diagnosed with cancer in outpatient community settings. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;91:105971. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2020.105971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nipp RD, Lee H, Powell E, et al. Financial burden of cancer clinical trial participation and the impact of a cancer care equity program. Oncologist. 2016;21:467–474. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burke S, Bruno M, Ulmer C. Future Directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kraft SA, Doerr M. Engaging populations underrepresented in research through novel approaches to consent. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2018;178:75–80. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Institutes of Health All of Us ResearchProgram, National Institutes of Health, US Dept. of Health and Human ServicesBethesda, MD2020 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Applequist J, Burroughs C, Ramirez A, Jr, et al. A novel approach to conducting clinical trials in the community setting: Utilizing patient-driven platforms and social media to drive Web-based patient recruitment. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20:58. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-00926-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tapp H, Dulin M. The science of primary health-care improvement: Potential and use of community-based participatory research by practice-based research networks for translation of research into practice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010;235:290–299. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2009.009265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fouad MN, Johnson RE, Nagy MC, et al. Adherence and retention in clinical trials: A community-based approach. Cancer. 2014;120:1106–1112. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greiner KA, Friedman DB, Adams SA, et al. Effective recruitment strategies and community-based participatory research: Community networks program centers’ recruitment in cancer prevention studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:416–423. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winkfield KM, Flowers CR, Patel JD, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology strategic plan for increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the oncology workforce. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2576–2579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nelson A. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94:666–668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. AAMC (American Association of Medical Colleges): Diversity in Medical Education. https://www.aamcdiversityfactsandfigures2016.org/

- 48.American Society of Clinical Oncology The state of cancer care in America, 2017: A report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e353–e394. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.020743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Institutes of Health . Physician-Scientist Workforce Working Group Report. National Institutes of Health, US Dept. of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7238. Hoppe TA, Litovitz A, Willis KA, et al: Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/Black scientists. Sci Adv 5:eaaw7238, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ortega AN, Albert SL, Sharif MZ, et al. Proyecto MercadoFRESCO: A multi-level, community-engaged corner store intervention in East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights. J Community Health. 2015;40:347–356. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9941-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cummins S, Flint E, Matthews SA. New neighborhood grocery store increased awareness of food access but did not alter dietary habits or obesity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:283–291. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Brien MJ, Whitaker RC. The role of community-based participatory research to inform local health policy: A case study. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1498–1501. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1878-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Cancer Care in Low-Resource Areas: Cancer Prevention and Early Detection: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32:20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trent M, Dooley DG, Dougé J, et al. The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20191765. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf.

- 58.Barksdale CL, Rodick WH, III, Hopson R, et al. Literature review of the National CLAS Standards: Policy and practical implications in reducing health disparities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4:632–647. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0267-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Department of Health and Human Services . National Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services Standards. Office of Minority Health; Rockville, MD: 2019. [Google Scholar]