Abstract

Candida species can readily colonize a multitude of indwelling devices, leading to biofilm formation. These three-dimensional, surface-associated Candida communities employ a multitude of sophisticated mechanisms to evade treatment, leading to persistent and recurrent infections with high mortality rates. Further complicating matters, the current arsenal of antifungal therapeutics that are effective against biofilms is extremely limited. Antifungal biomaterials are gaining interest as an effective strategy for combating Candida biofilm infections. In this review, we explore biomaterials developed to prevent Candida biofilm formation and those that treat existing biofilms. Surface functionalization of devices employing clinically utilized antifungals, other antifungal molecules, and antifungal polymers has been extremely effective at preventing fungi attachment, which is the first step of biofilm formation. Several mechanisms can lead to this attachment inhibition, including contact killing and release-based killing of surrounding planktonic cells. Eliminating mature biofilms is arguably much more difficult than prevention. Nanoparticles have shown the most promise in disrupting existing biofilms, with the potential to penetrate the dense fungal biofilm matrix and locally target fungal cells. We will describe recent advances in both surface functionalization and nanoparticle therapeutics for the treatment of Candida biofilms.

Keywords: Candida, biofilms, biomaterials, antifungal, surface functionalization, nanoparticles, antifungal polymers

Introduction

Candida is one of the most common causes of fungal infections worldwide, responsible for over 400,000 infections per year (Brown et al., 2012; Tsui et al., 2016). A commensal fungus that can readily become pathogenic, Candida, is known to form biofilms (Gulati and Nobile, 2016). These surface-attached, three-dimensional communities of tightly packed fungi can serve as infection strongholds, complicating treatment and leading to persistent fungemia (Li et al., 2018). Candida biofilm related infections have mortality rates as high as 41% (Rajendran et al., 2016). Biofilms protect fungal cells from the host immune system and often increase drug resistance (Mukherjee and Chandra, 2004; Nett, 2014). Biofilm fungi secrete a dense extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) that acts as a physical barrier for antifungal therapeutics, most of which are hydrophobic with limited ability to penetrate this matrix (Singh et al., 2018). Persister cells, which are metabolically dormant, can form as quickly as cell attachment occurs, leading to changes in gene expression, with an initial overexpression of drug efflux pumps, followed by a reduction in membrane sterol content in mature Candida biofilms (Kumamoto and Vinces, 2005; LaFleur et al., 2006). Although persister cells represent a small subpopulation within the biofilm (~1% of all cells), their tolerance to high doses of antimicrobials allows them to readily repopulate the biofilm once the treatment has stopped, resulting in recurring infections (Galdiero et al., 2020). Quorum sensing can mediate the secretion of signaling factors affecting Candida gene expression and behavior, including filamentation (Mallick and Bennett, 2013; Tsui et al., 2016). Changes to the cell wall that enhance drug resistance can also occur; for example, cell walls that are twice as thick as planktonic cells have been observed in biofilm Candida (Nett et al., 2007; Lima et al., 2019).

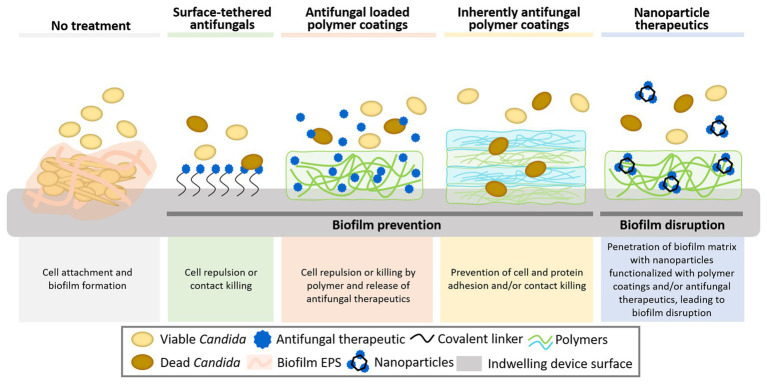

The majority of biofilm-associated Candida infections arise from cells that colonize the surfaces of implanted medical devices (Coad et al., 2016). These devices range from plastic cochlear implants and subcutaneous drug delivery devices, silicone or polyurethane catheters, and acrylic dental implants, to titanium hip implants, glass-ceramics used in bone repair, metal pacemakers, and polymeric contact lenses among many others (Vargas-Blanco et al., 2017; Cavalheiro and Teixeira, 2018; Devadas et al., 2019). Treatments for these biofilm-associated infections are extremely limited, with only three primary antifungal drug classes (polyenes, azoles, and echinocandins) and a total of 21 United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved antifungal drugs (Butts and Krysan, 2012; McKeny and Zito, 2020), of which only a subset have demonstrated some level of antibiofilm activity. Innovations in biomaterials have the potential to combat Candida biofilms (Figure 1). Here, we explore recent promising approaches in this field involving surface modification with antifungal small molecules and polymers aimed at preventing biofilm formation and the design of nanoparticles aimed at both preventing and disrupting Candida biofilms.

Figure 1.

Biomaterials strategies to combat surface-associated Candida biofilms. These strategies include direct surface functionalization with antimicrobial small molecules and natural and synthetic polymers and the use of nanoparticles, which may better penetrate the dense biofilm matrix and potentially target fungal cells. Together these strategies can prevent biofilm formation by inhibiting the initial attachment of fungi to surfaces and eradicate existing biofilms.

Preventing Candida Biofilms Using Surface Modification With Clinically Utilized Antifungals

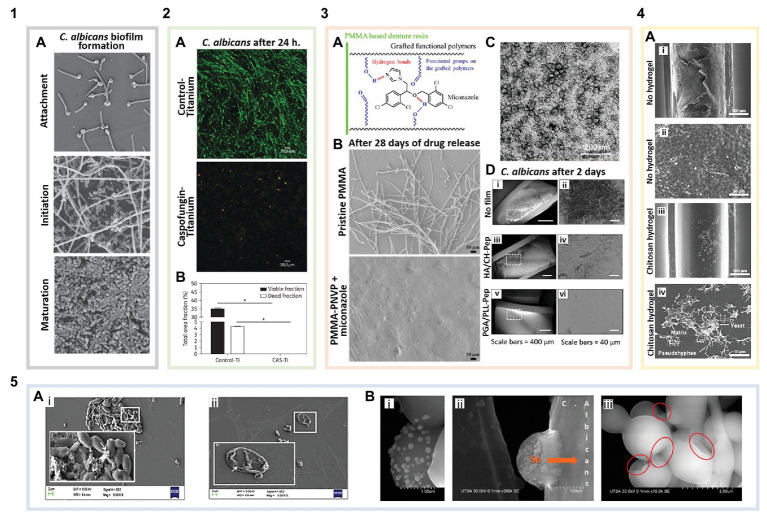

Inhibiting Candida attachment to surfaces, the first step of biofilm formation (Figure 2: 1A), is often the most effective way to combat biofilm-associated infections. Various approaches have been investigated to prevent fungi attachment, including surface functionalization with FDA-approved antifungals using covalent and non-covalent interactions (Zelikin, 2010). Caspofungin, the only echinocandin with primary amines, is most commonly used in direct surface tethering (Coad et al., 2015; Michl et al., 2017). Caspofungin tethered titanium disks cultured with Candida albicans showed complete inhibition of fungal attachment compared to bare titanium (Figure 2: 2A,B). These same caspofungin-tethered disks implanted subcutaneously into the backs of mice and challenged with C. albicans showed 89% less Candida attached after 2 days compared to bare disks (Kucharíková et al., 2016).

Figure 2.

Biomaterials for the prevention and treatment of Candida biofilms. (1) Biofilm formation of non-functionalized surfaces: (1A) Candida albicans biofilm formation (adapted with permission from Ramage et al., 2009). (2) Surface-tethered antifungals: (2A) Live/Dead staining showing caspofungin functionalized titanium disks (with caspofungin surface coverage of ~2,191 pmol/cm2) inhibiting C. albicans attachment and biofilm formation compared to bare titanium (green are live cells, and red indicates membrane compromised cells; adapted with permission from Kucharíková et al., 2016). (2B) Quantification of viable cells per area in the images shown in 2A (adapted with permission from Kucharíková et al., 2016). (3) Antifungal loaded polymer coatings: (3A) Schematic illustrating miconazole-polymer hydrogen bonding (adapted with permission from Wen et al., 2016a). (3B) Miconazole loaded into poly(methyl methacrylate)-poly(1-vinyl-2-pyrrolidinone) (PMMA-PNVP) films inhibits C. albicans attachment and biofilm growth for up to 28 days compared to pristine PMMA (adapted with permission from Wen et al., 2016a). (3C) Antifungal poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) + curcumin (CU) nanocomposites in solution after being released from graphene oxide (GO) coatings (adapted with permission from Devadas et al., 2019). (3D) Layer-by-layer (LbL) coated catheters prevent C. albicans attachment and biofilm formation after 2 days. (i) Uncoated catheters showing C. albicans attachment and biomass deposition. (ii) Magnified region outlined in 3D(i). (iii) Catheters coated with a hyaluronic acid (HA)/chitosan (CH) LbL film with β-peptide showing no C. albicans attachment but some biomass deposition on the surface. (iv) Magnified region outlined in 3D(iii). (v) Poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA)/poly-L-lysine (PLL) LbL film with β-peptide coated catheters showing no cell or biomass attachment. (vi) Magnified region outlined in 3D(v) (adapted with permission from Raman et al., 2016). (4) Inherently antifungal polymer coatings: (4A) Polyurethane catheter-associated Candida parapsilosis biofilms. (i) Uncoated catheters exhibiting Candida attachment and biofilm formation. (ii) Magnified region of image 4A(i) showing a dense C. parapsilosis biofilm. (iii) Catheters coated with low molecular weight CH hydrogels significantly reduce Candida cell attachment and biofilm formation. (iv) Magnified region of image 4A(iii) showing biofilm disruption (adapted with permission from Silva-Dias et al., 2014). (5) Antifungal nanoparticles: (5A) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of C. albicans biofilms on polystyrene. (i) Control biofilm cells [white arrow points to extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs)] and (ii) biofilm inhibition in the presence of ferulic acid-chitosan nanoparticles (white arrow indicates the damaged fungal cell wall; adapted with permission from Panwar et al., 2016). (5B) SEM images of selenium nanoparticles (i,ii) binding to and (iii) disrupting C. albicans cells in biofilms. The red circles indicate areas of the cell membrane, where the nanoparticles have induced shrinking and folding (adapted with permission from Guisbiers et al., 2017).

In an example of non-covalent drug tethering, β-cyclodextrins (CD) were grafted to polyethylene and polypropylene surfaces (Nava-Ortiz et al., 2010), commonly used in medical devices. CDs were used to promote host-guest interactions with the hydrophobic antifungal, miconazole, while also regulating interactions with proteins and increasing hemocompatibility. These miconazole loaded CD grafted surfaces exhibited up to a 97% reduction in the amount of recovered C. albicans compared to a silicone control incubated with the fungus. Polymers are also commonly used to enable non-covalent functionalization with antifungals, due to their ability to form multivalent interactions promoting loading of antifungal compounds. Wen et al. grafted poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (PHEMA) onto poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) denture resins. There is great interest in preventing Candida biofilms on dental surfaces, including dentures given the prevalence of Candida in the oral microbiota; in fact, Candida is responsible for up to 67% of denture-associated stomatitis (Ramage et al., 2006). PHEMA grafting was used to load the antifungal, clotrimazole, mediated via hydrogen bonding interactions, leading to a clotrimazole surface coverage of up to 46.0 ± 3.2 μg/cm2 compared to 5.2 ± 0.4 μg/cm2 on bare PMMA. A sustained release of clotrimazole was observed from the PHEMA-grafted denture disks over 28 days, yielding approximately a 50 and 36% reduction in C. albicans adhesion after 1 and 28 days, respectively, compared with non PHEMA-grafted disks (Wen et al., 2016b). Grafting poly(1-vinyl-2-pyrrolidinone) (PNVP) to PMMA enabled miconazole loading of 127.0 ± 15.1 μg/cm2, likely mediated via hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding (Figure 2: 3A). PNVP-grafted resins with miconazole showed no Candida adhesion even after 28 days of drug release (Figure 2: 3B; Wen et al., 2016a). Along with superior biocompatibility, these functionalized materials can be used for extended biofilm prevention and have the potential to be reloaded with therapeutics.

Preventing Candida Biofilms Using Surface Modification With New Antifungal Small Molecules and Peptides

Although promising, surface functionalization with FDA-approved antifungals raises concerns for increased resistance to these therapeutics. Thus, there is an interest in alternative approaches to prevent Candida biofilms utilizing non-clinically used small molecules and peptides with inherent antifungal and antibiofilm properties. One example, filastatin, a potent small molecule inhibitor of Candida attachment and filamentation was recently identified in a screen of 30,000 compounds (Fazly et al., 2013). Vargas-Blanco et al. (2017) found that incubation of C. albicans with various biomaterials in the presence of filastatin can inhibit Candida attachment to these materials. Adsorption of filastatin on dental resin and silicone showed that Candida cell attachment was reduced on these materials by 62.7 and 79.7%, respectively, compared to uncoated controls. By incorporating filastatin into the silicone matrix during polymerization a 6.5-fold reduction in C. albicans adhesion compared to untreated silicone controls was observed (Vargas-Blanco et al., 2017). Other small molecule biofilm inhibitors specifically interrupt Candida quorum sensing. These molecules include furanones, which are plant synthesized compounds that prevent microbial fouling on the plant surface. Devadas et al. (2019) coated common catheter materials with a furanone embedded polycaprolactone matrix. These polymer coatings retained 85% or more of the total loaded furanone over at least 30 days in solution. The attachment of clinical isolates of Candida tropicalis, Candida glabrata, and Candida krusei on these coated catheters was completely inhibited as determined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Devadas et al., 2019). Other plant derived compounds have also shown activity against Candida biofilms when combined with biomaterials. Recently, clove oil and red thyme oil incorporated in polycaprolactone electrospun nanofibers led to a 60 and 80% reduction in C. tropicalis attachment, respectively (Sahal et al., 2019). Initial results with these small molecules are promising; future studies will likely examine functionalization via covalent tethering or affinity-based interactions with these compounds to enable long-term antibiofilm activity.

Combination approaches to prevent Candida biofilms involving the inhibition of fungal cell attachment and simultaneous killing of planktonic fungi have also been investigated. Palmieri et al. (2018) developed a multilayered coating by drop-casting graphene oxide (GO) on polyurethane catheters, followed by curcumin (CU) and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). The GO was included to prevent C. albicans attachment due to its ability to generate oxidative stress and physically disrupt the cell wall and membrane. CU + PEG self-assembled nanocomposites (75–125 nm in diameter; Figure 2: 3C) were released from these coatings inhibiting planktonic C. albicans growth, with a minimum inhibitory concentration of 10.6 μg/ml. The complete catheter coating inhibited C. albicans attachment in vitro after 24 h with less than 20% biofilm formation compared to uncoated controls (Palmieri et al., 2018).

As an alternative to solvent casting or vapor deposition approaches, many biomedical surfaces have been coated via layer-by-layer (LbL) self-assembly to develop antifungal coatings. LbL assembly is a multilayer film fabrication method that involves alternating the adsorption of molecules and macromolecules (e.g., polyelectrolytes, peptides, proteins, small molecules, etc.,) with complementary functionalities most commonly by dip coating (Shukla and Almeida, 2014; Alkekhia and Shukla, 2019; Alkekhia et al., 2020). LbL films have been combined with antifungal peptides to exhibit remarkable antibiofilm properties. Antifungal peptides are considered potent and broad-spectrum antifungals; due to their multiple mechanisms of action, fungi are often unable to develop resistance to these peptides (Oshiro et al., 2019). These peptides are most commonly amphiphilic and cationic allowing them to readily interact with the fungal cell membrane, causing cell death (Karlsson et al., 2010). Raman et al. (2016) assembled an LbL film with hyaluronic acid (HA) and chitosan (CH) on catheter surfaces and used it as a reservoir for a synthetic antifungal β-peptide. The luminal surface of polyurethane catheters coated with these LbL films without any β-peptide was able to reduce viable C. albicans by approximately 25-fold after 6 h of exposure when compared to uncoated polyurethane catheters, demonstrating the innate antifungal properties of this polymeric coating. When passively loaded with the antifungal β-peptide, sustained release of the β-peptide was achieved over 50 days with complete eradication of planktonic C. albicans in vitro. Catheters coated with the β-peptide-loaded films tested in a rat central venous catheter model exhibited almost no fungal cells following 2 days [Figure 2: 3D(i–iv)]. However, this coated surface was found to contain a network of host proteins, which can yield complications, including fouling with red blood cells, which can stimulate platelet production. Another film architecture examined in the same study utilizing β-peptide-loaded poly-L-lysine (PLL) and poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA) LbL films exhibited both a complete lack of Candida cell attachment and host proteins when tested in the same in vivo model [Figure 2: 3D(v,vi)], emphasizing the importance of polymer choice in preventing overall fouling (Raman et al., 2016). PMMA denture disks were also recently coated with an LbL film containing the cationic mammalian salivary antifungal peptide, histatin-5 (H-5), and HA with a final H-5 layer. SEM images confirmed over 4 weeks that these LbL coated surfaces were able to completely prevent Candida attachment (Wen et al., 2018).

Many other small molecules and peptides not yet incorporated into biomaterials have demonstrated antibiofilm activity. Among these are newly synthesized imidazole derivatives, which have been found to prevent Candida biofilm formation and disrupt existing biofilms (Ribeiro et al., 2014; Gabriel et al., 2019). Thiazolylhydrazone derivatives have also recently emerged as effective antifungal compounds with low mammalian cell toxicity (Cruz et al., 2018). 2,6-Bis[(E)-(4-pyridyl)methylidene]cyclohexanone, an antiparasitic compound, was also found to exhibit antifungal properties including the inhibition of Candida filamentation, crucial in biofilm formation (de Sá et al., 2018). Antifungal peptide derivatives of H-5 are also being explored (Sultan et al., 2019), and other host defense peptides such as innate defense regulator 1018 and porcine cathelicidins have recently been shown to possess antifungal and antibiofilm properties against Candida (Lyu et al., 2016; Freitas et al., 2017). These compounds are potential candidates for incorporation into antifungal biomaterials.

Preventing Candida Biofilms Using Polymer-Only Coatings

Many polymers themselves possess inherent antifouling, antifungal, and/or antibiofilm properties, while being less susceptible to resistance compared with small molecule antifungals; therefore, the use of polymer-only coatings for combating Candida biofilms has gained significant interest. For example, chitosan, a naturally derived polysaccharide, has been widely incorporated into hydrogels and coatings to prevent Candida attachment and biofilm formation (Carlson et al., 2008; Ailincai et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2016). It is hypothesized that chitosan interacts electrostatically via its positively charged amino groups with anionic moieties on microbial species leading to increased membrane permeability and eventual cell death (Jung et al., 2020). In a recent study, polyurethane intravenous catheters were coated with low molecular weight (50 kDa) chitosan hydrogels, implanted subcutaneously into mice, and subsequently challenged with Candida parapsilosis. Following 7 days, the chitosan-coated catheters reduced Candida metabolic activity by ~96% when compared to uncoated catheters, showcasing the ability of polymer-only coatings free of small molecule antifungals to achieve excellent antibiofilm activity. Reduced biomass on these chitosan coated catheters was shown using SEM (Figure 2: 4A; Silva-Dias et al., 2014). Chitosan has also been modified to enhance its antibiofilm properties. Jung et al. (2019) examined the use of amphiphilic quaternary ammonium chitosans (AQACs) in LbL coatings. LbL films containing sodium alginate and AQAC, effectively prevented cell attachment on coated PMMA substrates (Jung et al., 2019). AQACs have been shown to disrupt mature Candida biofilms by interacting electrostatically with the negatively charged biofilm surface (Jung et al., 2020). Coatings with other polymers including imidazolium salt (IS) conjugated poly(L-lactide) (PLA) have also been used to effectively prevent Candida attachment on coated surfaces (Schrekker et al., 2016).

Nanoparticles for the Prevention of Fungal Cell Attachment and Biofilm Eradication

Despite the progress that has been made in antifungal surface functionalization, these approaches are limited in their ability to treat mature biofilms. Nanoparticles are a promising strategy to eradicate existing biofilms, with the potential to carry, stabilize, and protect therapeutic payloads, penetrate the EPS, target fungal cells, and be internalized (Ikuma et al., 2015; Qayyum and Khan, 2016; Stone et al., 2016). Several strategies have been used to develop nanoparticles for the treatment of fungal infections, from using inorganic compounds to antimicrobial polymers (Ahmad et al., 2016; Amaral et al., 2019). In an example of the latter approach, chitosan nanoparticles (20–30 nm diameter) were recently examined for their ability to inhibit C. albicans biofilm growth, following initial cell attachment. Incubation with chitosan nanoparticles for 3 h led to a greater than 50% reduction in biofilm mass compared to non-treated controls (Ikono et al., 2019). While these chitosan nanoparticles exhibited some inherent antibiofilm activity, they were unable to entirely inhibit or disrupt Candida biofilms. Panwar et al. (2016) instead incorporated ferulic acid, a plant derived small molecule with known antibiofilm properties (Teodoro et al., 2015), into chitosan nanoparticles (~115 nm diameter). On its own, ferulic acid cannot efficiently penetrate fungal biofilms; however, when incorporated into chitosan nanoparticles and incubated with C. albicans biofilms, a significant reduction in fungal metabolic activity was observed (22.5% normalized to an untreated biofilm following 24 h). While the mechanism of these nanoparticles is not fully understood, it is believed that their strong cationic surface charge allows them to localize to and disrupt the fungal cell membrane while the surface bound ferulic acid interrupts Candida oxidative phosphorylation. This cell damage is evident in SEM images [Figure 2: 5A(ii)] when compared to healthy biofilm cells [Figure 2: 5A(i); Panwar et al., 2016].

Lipid-based self-assembled nanoparticles have also shown promise in penetrating the biofilm matrix and in targeting fungal cells. AmBisome®, a widely utilized liposomal formulation of amphotericin B, is able to disrupt Candida biofilms while free amphotericin B is unable to do this (Stone et al., 2016). AmBisome has a strong affinity for Candida cells, electrostatically interacting with the cell wall before binding to the cell membrane at sites of high ergosterol content (Soo Hoo, 2017), which may promote their activity against biofilm Candida cells, which have been shown to have thicker cell walls (Nett et al., 2007). Liposomal amphotericin B has also been immobilized on biomaterial surfaces for the prevention of biofilm formation (Alves et al., 2019). In our recent work, we have shown that liposomes encapsulating anidulafungin, the latest echinocandin approved by the FDA, are effective against mature C. albicans biofilms, reducing metabolic activity to approximately 46% compared to untreated controls over 24 h. Biofilms treated with an equivalent concentration of free anidulafungin did not reduce metabolic activity, further emphasizing the importance of nanoformulations in the treatment of Candida biofilms (Vera-González et al., 2020).

In addition to organic nanoparticles, inorganic nanoparticles have also been widely utilized for their antimicrobial properties, most commonly including silver and silica nanoparticles (Cousins et al., 2007; Monteiro et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2013). Silver nanoparticles were recently shown to inhibit biofilm formation of multi-drug resistant Candida auris (Lara et al., 2020), an emerging fungal threat with the unique ability to survive on surfaces for several weeks (Welsh et al., 2017). Selenium nanoparticles, which are less toxic to mammalian cells than silver nanoparticles, have only recently been explored for their antimicrobial properties (Huang et al., 2016). Guisbiers et al. (2017) demonstrated that ~100 nm selenium nanoparticles successfully inhibited the formation of C. albicans biofilms by attaching to and penetrating through the cell wall (Figure 2: 5B), replacing sulfur with selenium in important biochemical processes. These particles were able to reduce fungal burden in mature biofilms by over 50% at a nanoparticle concentration of as low as 26 ppm (Guisbiers et al., 2017). Inorganic nanoparticles have also been combined with antimicrobial therapeutics, to enhance antifungal properties. de Alteriis et al. (2018) conjugated the mammalian antimicrobial cathelicidin peptide, indolicidin, to the surface of gold nanoparticles (5 nm diameter) in order to protect it from proteolytic degradation and self-aggregation. These particles were able to penetrate and disrupt mature biofilms, eradicating over 50% of the cells for the most C. albicans and C. tropicalis strains tested after 24 h of treatment when compared to untreated biofilms, with a hypothesized mechanism involving penetration of the fungal cell membrane and inhibition of intracellular targets, arresting cell metabolism (de Alteriis et al., 2018).

Conclusions and Perspectives

We have discussed several biomaterials strategies from surface functionalization to nanoparticle drug delivery for the prevention and disruption of Candida biofilms. Other approaches that can be combined with biomaterials to functionalize surfaces prone to the biofilm formation in the near future include the use of enzymes that target and digest EPS components (Nett, 2014), identification of new drug targets, including inhibition of Candida extracellular vesicles (Zarnowski et al., 2018), and incorporation of polymers, such as nylon-3 that have potent and selective activity against Candida biofilms (Liu et al., 2014, 2015).

While many advances have been made, development of antifungal biomaterials lags behind the development of antibacterial materials. There is a need for expansion and innovation in antifungal biomaterials, and an emphasis must be placed on advancing technologies beyond preclinical testing. Attention must also be given to polymicrobial biofilms, comprised of multiple fungal and bacterial species, which are currently understudied (Harriott and Noverr, 2009). It is estimated that more than 50% of C. albicans infections are polymicrobial in nature (Harriott and Noverr, 2011; Nash et al., 2016). Undoubtedly, it will be critical to use multi-pronged strategies combining effective biomaterials approaches (e.g., surface coatings with nanoparticles) to successfully combat Candida and other microbial biofilms.

Author Contributions

NV-G and AS organized, prepared, and approved the final version of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

AS and NV-G thank Brown University graduate student, Carly Deusenbery, and postdoctoral researcher, Dr. Akram Abbasi, for useful discussions related to figure preparation.

Footnotes

Funding. AS and NV-G acknowledge support from the Office of Naval Research (grant N000141712651) awarded to AS and from a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship awarded to NV-G (grant 1644760).

References

- Ahmad A., Wei Y., Syed F., Tahir K., Taj R., Khan A. U., et al. (2016). Amphotericin B-conjugated biogenic silver nanoparticles as an innovative strategy for fungal infections. Microb. Pathog. 99, 271–281. 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.08.031, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ailincai D., Marin L., Morariu S., Mares M., Bostanaru A. -C., Pinteala M., et al. (2016). Dual crosslinked iminoboronate-chitosan hydrogels with strong antifungal activity against Candida planktonic yeasts and biofilms. Carbohydr. Polym. 152, 306–316. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.07.007, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkekhia D., Hammond P. T., Shukla A. (2020). Layer-by-layer biomaterials for drug delivery. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 22, 1–24. 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-060418-052350, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkekhia D., Shukla A. (2019). Influence of poly-L-lysine molecular weight on antibacterial efficacy in polymer multilayer films. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 107, 1324–1339. 10.1002/jbm.a.36645, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves D., Vaz A. T., Grainha T., Rodrigues C. F., Pereira M. O. (2019). Design of an antifungal surface embedding liposomal amphotericin b through a mussel adhesive-inspired coating strategy. Front. Chem. 7:431. 10.3389/fchem.2019.00431, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral A. C., Saavedra P. H. V., Oliveira Souza A. C., de Melo M. T., Tedesco A. C., Morais P. C., et al. (2019). Miconazole loaded chitosan-based nanoparticles for local treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis fungal infections. Colloids Surf. B 174, 409–415. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.11.048, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. D., Denning D. W., Gow N. A. R., Levitz S. M., Netea M. G., White T. C. (2012). Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci. Transl. Med. 4:165rv13. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts A., Krysan D. J. (2012). Antifungal drug discovery: something old and something new. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002870. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002870, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson R. P., Taffs R., Davison W. M., Stewart P. S. (2008). Anti-biofilm properties of chitosan-coated surfaces. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 19, 1035–1046. 10.1163/156856208784909372, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalheiro M., Teixeira M. C. (2018). Candida biofilms: threats, challenges, and promising strategies. Front. Med. 5:28. 10.3389/fmed.2018.00028, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coad B. R., Griesser H. J., Peleg A. Y., Traven A. (2016). Anti-infective surface coatings: design and therapeutic promise against device-associated infections. PLoS Pathog. 12:e1005598. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005598, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coad B. R., Lamont-Friedrich S. J., Gwynne L., Jasieniak M., Griesser S. S., Traven A., et al. (2015). Surface coatings with covalently attached caspofungin are effective in eliminating fungal pathogens. J. Mater. Chem. B 3, 8469–8476. 10.1039/C5TB00961H, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins B. G., Allison H. E., Doherty P. J., Edwards C., Garvey M. J., Martin D. S., et al. (2007). Effects of a nanoparticulate silica substrate on cell attachment of Candida albicans. J. Appl. Microbiol. 102, 757–765. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03124.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz L., Lopes L., de Camargo Ribeiro F., de Sá N., Lino C., Tharmalingam N., et al. (2018). Anti-Candida albicans activity of thiazolylhydrazone derivatives in invertebrate and murine models. J. Fungi 4:134. 10.3390/jof4040134, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alteriis E., Maselli V., Falanga A., Galdiero S., Di Lella F. M., Gesuele R., et al. (2018). Efficiency of gold nanoparticles coated with the antimicrobial peptide indolicidin against biofilm formation and development of Candida spp. clinical isolates. Infect. Drug Resist. 11, 915–925. 10.2147/IDR.S164262, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sá N. P., de Paula L. F. J., Lopes L. F. F., Cruz L. I. B., Matos T. T. S., Lino C. I., et al. (2018). In vivo and in vitro activity of a bis-arylidenecyclo-alkanone against fluconazole-susceptible and -resistant isolates of Candida albicans. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 14, 287–293. 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.04.012, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devadas S. M., Nayak U. Y., Narayan R., Hande M. H., Ballal M. (2019). 2,5-Dimethyl-4-hydroxy-3(2H)-furanone as an anti-biofilm agent against non-Candida albicans Candida species. Mycopathologia 184, 403–411. 10.1007/s11046-019-00341-y, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazly A., Jain C., Dehner A. C., Issi L., Lilly E. A., Ali A., et al. (2013). Chemical screening identifies filastatin, a small molecule inhibitor of Candida albicans adhesion, morphogenesis, and pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 13594–13599. 10.1073/pnas.1305982110, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas C. G., Lima S. M. F., Freire M. S., Cantuária A. P. C., Júnior N. G. O., Santos T. S., et al. (2017). An immunomodulatory peptide confers protection in an experimental candidemia murine model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e02518–e02616. 10.1128/AAC.02518-16, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel C., Grenho L., Cerqueira F., Medeiros R., Dias A. M., Ribeiro A. I., et al. (2019). Inhibitory effect of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carbohydrazonamides derivatives against Candida spp. biofilm on nanohydroxyapatite substrate. Mycopathologia 184, 775–786. 10.1007/s11046-019-00400-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdiero E., de Alteriis E., De Natale A., D’Alterio A., Siciliano A., Guida M., et al. (2020). Eradication of Candida albicans persister cell biofilm by the membranotropic peptide gH625. Sci. Rep. 10:5780. 10.1038/s41598-020-62746-w, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guisbiers G., Lara H. H., Mendoza-Cruz R., Naranjo G., Vincent B. A., Peralta X. G., et al. (2017). Inhibition of Candida albicans biofilm by pure selenium nanoparticles synthesized by pulsed laser ablation in liquids. Nanomedicine 13, 1095–1103. 10.1016/J.NANO.2016.10.011, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati M., Nobile C. J. (2016). Candida albicans biofilms: development, regulation, and molecular mechanisms. Microbes Infect. 18, 310–321. 10.1016/j.micinf.2016.01.002, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harriott M. M., Noverr M. C. (2009). Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus form polymicrobial biofilms: effects on antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 3914–3922. 10.1128/AAC.00657-09, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harriott M. M., Noverr M. C. (2011). Importance of Candida–bacterial polymicrobial biofilms in disease. Trends Microbiol. 19, 557–563. 10.1016/j.tim.2011.07.004, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Chen X., Chen Q., Yu Q., Sun D., Liu J. (2016). Investigation of functional selenium nanoparticles as potent antimicrobial agents against superbugs. Acta Biomater. 30, 397–407. 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.10.041, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikono R., Vibriani A., Wibowo I., Saputro K. E., Muliawan W., Bachtiar B. M., et al. (2019). Nanochitosan antimicrobial activity against Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans dual-species biofilms. BMC Res. Notes 12:383. 10.1186/s13104-019-4422-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikuma K., Decho A. W., Lau B. L. T. (2015). When nanoparticles meet biofilms-interactions guiding the environmental fate and accumulation of nanoparticles. Front. Microbiol. 6:591. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00591, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J., Bae Y., Kwan Cho Y., Ren X., Sun Y. (2020). Structural insights into conformation of amphiphilic quaternary ammonium chitosans to control fungicidal and anti-biofilm functions. Carbohydr. Polym. 228:115391. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115391, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J., Li L., Yeh C. -K., Ren X., Sun Y. (2019). Amphiphilic quaternary ammonium chitosan/sodium alginate multilayer coatings kill fungal cells and inhibit fungal biofilm on dental biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 104:109961. 10.1016/j.msec.2019.109961, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson A. J., Flessner R. M., Gellman S. H., Lynn D. M., Palecek S. P. (2010). Polyelectrolyte multilayers fabricated from antifungal β-peptides: design of surfaces that exhibit antifungal activity against Candida albicans. Biomacromolecules 11, 2321–2328. 10.1021/bm100424s, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharíková S., Gerits E., De Brucker K., Braem A., Ceh K., Majdič G., et al. (2016). Covalent immobilization of antimicrobial agents on titanium prevents Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans colonization and biofilm formation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71, 936–945. 10.1093/jac/dkv437, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto C. A., Vinces M. D. (2005). Alternative Candida albicans lifestyles: growth on surfaces. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59, 113–133. 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121034, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFleur M. D., Kumamoto C. A., Lewis K. (2006). Candida albicans biofilms produce antifungal-tolerant persister cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 3839–3846. 10.1128/AAC.00684-06, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara H. H., Ixtepan-Turrent L., Jose Yacaman M., Lopez-Ribot J. (2020). Inhibition of Candida auris biofilm formation on medical and environmental surfaces by silver nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 21183–21191. 10.1021/acsami.9b20708, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. -S., Chen Y. -C., Kuo S. -F., Chen F. -J., Lee C. -H. (2018). The impact of biofilm formation on the persistence of candidemia. Front. Microbiol. 9:1196. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01196, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima S. L., Colombo A. L., de Almeida Junior J. N. (2019). Fungal cell wall: emerging antifungals and drug resistance. Front. Microbiol. 10:2573. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02573, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Chen X., Falk S. P., Masters K. S., Weisblum B., Gellman S. H. (2015). Nylon-3 polymers active against drug-resistant Candida albicans biofilms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 2183–2186. 10.1021/ja512567y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Chen X., Falk S. P., Mowery B. P., Karlsson A. J., Weisblum B., et al. (2014). Structure–activity relationships among antifungal nylon-3 polymers: identification of materials active against drug-resistant strains of Candida albicans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4333–4342. 10.1021/ja500036r, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu Y., Yang Y., Lyu X., Dong N., Shan A. (2016). Antimicrobial activity, improved cell selectivity and mode of action of short PMAP-36-derived peptides against bacteria and Candida. Sci. Rep. 6:27258. 10.1038/srep27258, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallick E. M., Bennett R. J. (2013). Sensing of the microbial neighborhood by Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003661. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003661, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeny P. T., Zito P. M. (2020). Antifungal antibiotics. StatPearls publishing. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30844195 (Accessed February 6, 2020). [PubMed]

- Michl T. D., Giles C., Mocny P., Futrega K., Doran M. R., Klok H. -A., et al. (2017). Caspofungin on ARGET-ATRP grafted PHEMA polymers: enhancement and selectivity of prevention of attachment of Candida albicans. Biointerphases 12:05G602. 10.1116/1.4986054, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro D. R., Gorup L. F., Silva S., Negri M., de Camargo E. R., Oliveira R., et al. (2011). Silver colloidal nanoparticles: antifungal effect against adhered cells and biofilms of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata. Biofouling 27, 711–719. 10.1080/08927014.2011.599101, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P., Chandra J. (2004). Candida biofilm resistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 7, 301–309. 10.1016/j.drup.2004.09.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash E. E., Peters B. M., Fidel P. L., Noverr M. C. (2016). Morphology-independent virulence of Candida species during polymicrobial intra-abdominal infections with Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 84, 90–98. 10.1128/IAI.01059-15, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nava-Ortiz C. A. B., Burillo G., Concheiro A., Bucio E., Matthijs N., Nelis H., et al. (2010). Cyclodextrin-functionalized biomaterials loaded with miconazole prevent Candida albicans biofilm formation in vitro. Acta Biomater. 6, 1398–1404. 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.10.039, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nett J. E. (2014). Future directions for anti-biofilm therapeutics targeting Candida. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 12, 375–382. 10.1586/14787210.2014.885838, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nett J., Lincoln L., Marchillo K., Massey R., Holoyda K., Hoff B., et al. (2007). Putative role of β-1,3 glucans in Candida albicans biofilm resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 510–520. 10.1128/AAC.01056-06, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshiro K. G. N., Rodrigues G., Monges B. E. D., Cardoso M. H., Franco O. L. (2019). Bioactive peptides against fungal biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 10:2169. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02169, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri V., Bugli F., Cacaci M., Perini G., De Maio F., Delogu G., et al. (2018). Graphene oxide coatings prevent Candida albicans biofilm formation with a controlled release of curcumin-loaded nanocomposites. Nanomedicine 13, 2867–2879. 10.2217/nnm-2018-0183, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panwar R., Pemmaraju S. C., Sharma A. K., Pruthi V. (2016). Efficacy of ferulic acid encapsulated chitosan nanoparticles against Candida albicans biofilm. Microb. Pathog. 95, 21–31. 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.02.007, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qayyum S., Khan A. U. (2016). Nanoparticles vs. biofilms: a battle against another paradigm of antibiotic resistance. Med. Chem. Commun. 7, 1479–1498. 10.1039/C6MD00124F [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran R., Sherry L., Nile C. J., Sherriff A., Johnson E. M., Hanson M. F., et al. (2016). Biofilm formation is a risk factor for mortality in patients with Candida albicans bloodstream infection-Scotland, 2012-2013. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 22, 87–93. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.09.018, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramage G., Martínez J. P., López-Ribot J. L. (2006). Candida biofilms on implanted biomaterials: a clinically significant problem. FEMS Yeast Res. 6, 979–986. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00117.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramage G., Mowat E., Jones B., Williams C., Lopez-Ribot J. (2009). Our current understanding of fungal biofilms. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 35, 340–355. 10.3109/10408410903241436, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman N., Marchillo K., Lee M. -R., de L Rodríguez López A., Andes D. R., Palecek S. P., et al. (2016). Intraluminal release of an antifungal β-peptide enhances the antifungal and anti-biofilm activities of multilayer-coated catheters in a rat model of venous catheter infection. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2, 112–121. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00427, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro A. I., Gabriel C., Cerqueira F., Maia M., Pinto E., Sousa J. C., et al. (2014). Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of novel 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamidrazones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 4699–4702. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.08.025, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahal G., Nasseri B., Ebrahimi A., Bilkay I. S. (2019). Electrospun essential oil-polycaprolactone nanofibers as antibiofilm surfaces against clinical Candida tropicalis isolates. Biotechnol. Lett. 41, 511–522. 10.1007/s10529-019-02660-y, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrekker C. M. L., Sokolovicz Y. C. A., Raucci M. G., Selukar B. S., Klitzke J. S., Lopes W., et al. (2016). Multitask imidazolium salt additives for innovative poly(L-lactide) biomaterials: morphology control, Candida spp. biofilm inhibition, human mesenchymal stem cell biocompatibility, and skin tolerance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 21163–21176. 10.1021/acsami.6b06005, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla A., Almeida B. (2014). Advances in cellular and tissue engineering using layer-by-layer assembly. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 6, 411–421. 10.1002/wnan.1269, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva S., Pires P., Monteiro D. R., Negri M., Gorup L. F., Camargo E. R., et al. (2013). The effect of silver nanoparticles and nystatin on mixed biofilms of Candida glabrata and Candida albicans on acrylic. Med. Mycol. 51, 178–184. 10.3109/13693786.2012.700492, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Dias A., Palmeira-de-Oliveira A., Miranda I. M., Branco J., Cobrado L., Monteiro-Soares M., et al. (2014). Anti-biofilm activity of low-molecular weight chitosan hydrogel against Candida species. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 203, 25–33. 10.1007/s00430-013-0311-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Kumari A., Kaur K., Sethi P., Chakrabarti A. (2018). Relevance of antifungal penetration in biofilm-associated resistance of Candida albicans and non-albicans Candida species. J. Med. Microbiol. 67, 922–926. 10.1099/jmm.0.000757, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soo Hoo L. (2017). Fungal fatal attraction: a mechanistic review on targeting liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome®) to the fungal membrane. J. Liposome Res. 27, 180–185. 10.1080/08982104.2017.1360345, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone N. R. H., Bicanic T., Salim R., Hope W. (2016). Liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome®): a review of the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, clinical experience and future directions. Drugs 76, 485–500. 10.1007/s40265-016-0538-7, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan A. S., Vila T., Hefni E., Karlsson A. J., Jabra-Rizk M. A. (2019). Evaluation of the antifungal and wound-healing properties of a novel peptide-based bioadhesive hydrogel formulation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, e00888–e00919. 10.1128/AAC.00888-19, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y., Leonhard M., Moser D., Ma S., Schneider-Stickler B. (2016). Inhibition of mixed fungal and bacterial biofilms on silicone by carboxymethyl chitosan. Colloids Surf. B 148, 193–199. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.08.061, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodoro G. R., Ellepola K., Seneviratne C. J., Koga-Ito C. Y. (2015). Potential use of phenolic acids as anti-Candida agents: a review. Front. Microbiol. 6:1420. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01420, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui C., Kong E. F., Jabra-Rizk M. A. (2016). Pathogenesis of Candida albicans biofilm. Pathog. Dis. 74:ftw018. 10.1093/femspd/ftw018, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Blanco D., Lynn A., Rosch J., Noreldin R., Salerni A., Lambert C., et al. (2017). A pre-therapeutic coating for medical devices that prevents the attachment of Candida albicans. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 16:41. 10.1186/s12941-017-0215-z, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera-González N., Bailey-Hytholt C. M., Langlois L., de Camargo Ribeiro F., de Souza Santos E. L., Junqueira J. C., et al. (2020). Anidulafungin liposome nanoparticles exhibit antifungal activity against planktonic and biofilm Candida albicans. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 108, 2263–2276. 10.1002/jbm.a.36984, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh R. M., Bentz M. L., Shams A., Houston H., Lyons A., Rose L. J., et al. (2017). Survival, persistence, and isolation of the emerging multidrug-resistant pathogenic yeast Candida auris on a plastic health care surface. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55, 2996–3005. 10.1128/JCM.00921-17, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J., Jiang F., Yeh C. -K., Sun Y. (2016a). Controlling fungal biofilms with functional drug delivery denture biomaterials. Colloids Surf. B 140, 19–27. 10.1016/J.COLSURFB.2015.12.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J., Yeh C. -K., Sun Y. (2016b). Functionalized denture resins as drug delivery biomaterials to control fungal biofilms. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2, 224–230. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J., Yeh C. -K., Sun Y. (2018). Salivary polypeptide/hyaluronic acid multilayer coatings act as “fungal repellents” and prevent biofilm formation on biomaterials. J. Mater. Chem. B 6, 1452–1457. 10.1039/C7TB02592K, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarnowski R., Sanchez H., Covelli A. S., Dominguez E., Jaromin A., Bernhardt J., et al. (2018). Candida albicans biofilm–induced vesicles confer drug resistance through matrix biogenesis. PLoS Biol. 16:e2006872. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006872, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelikin A. N. (2010). Drug releasing polymer thin films: new era of surface-mediated drug delivery. ACS Nano 4, 2494–2509. 10.1021/nn100634r, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]