The killing of Eric Garner in 2014 at the hands of the New York Police Department and the footage that circulated of his death after he was put in a chokehold elevated the phrase “I can't breathe” to a protest chant for those in the fight against structural racism worldwide. Its repetition by George Floyd in Minneapolis, MN, USA, in 2020 and by others in anti-racism protests amid the COVID-19 pandemic has deepened the salience of these words. While much public health research has shown that racism is a fundamental determinant of health outcomes and disparities, racist policy and practice have also been integral to the historical formation of the medical academy in the USA.

The term structural violence has its origins in peace studies in the 1960s as a way of understanding the iniquities of imperialism that persisted in the post-colonial world. As Paul Farmer and colleagues have described, structural violence explains how the organisation of society “puts individuals and populations in harm's way. The arrangements are structural because they are embedded in the political and economic organization of our social world; they are violent because they cause injury to people (typically, not those responsible for perpetuating such inequalities).” While no single concept can capture the complexity or full dynamics of racism, the brief historical examples we discuss here show that structural violence is helpful for understanding how the histories of violence, neglect, and oppression that crisscross law enforcement, politics, medical care, and public health are inextricably linked and manifested in the present.

Like the history of US policing, the history of medicine and health care in the USA is marked by racial injustice and myriad forms of violence: unequal access to health care, the segregation of medical facilities, and the exclusion of African Americans from medical education are some of the most obvious examples. These, together with inequalities in housing, employment opportunities, wealth, and social service provision, produce disproportionate health disparities by race. The health community needs to confront these painful histories of structural violence to develop more effective anti-racist and benevolent public health responses to entrenched health inequalities, the COVID-19 pandemic, and future pandemics.

Since 1619 when the first enslaved people were brought to the British Colony of Virginia until June 19, 1865, when the last enslaved Black person was emancipated in the USA, Black people, and especially Black women, endured violent medical treatment and experimentation against their will. Enslaved Black people's bodies were exploited for the development of some aspects of US medical education in the 19th century. Medical schools relied on enslaved Black bodies as “anatomical material” and recruited students in southern states by advertising its abundance. This practice was widespread in the 19th and early 20th centuries. American medical education relied on the theft, dissection, and display of bodies, many of whom were Black. The Virginia Medical College, for example, employed a Black man named Chris Baker as its “resurrectionist” to steal freshly buried Black bodies to use for dissection. Baker was the resurrectionist from the 1880s until his death in 1919. The Medical College of Georgia purchased an enslaved man, Grandison Harris, to work as the resurrectionist in 1852 and he remained in the position after emancipation. Although White people also worked as resurrectionists, Black people's entry into segregated cemeteries attracted less attention.

Similar to dissection, some medical specialties relied on experimentation on enslaved peoples and their labour. James Marion Sims, widely held as the founder of US gynaecology, came to many of his discoveries in the 19th century by experimenting on enslaved women, while also forcing them to perform domestic duties and serve as nurses in his clinic. In the words of historian Deirdre Cooper Owens, to early gynaecologists enslaved women were “flesh-and-blood contradictions, vital to their research yet dispensable once their bodies and labour were no longer required”.

The coercive nature of this history resonates with attitudes towards reproductive rights decades later. Native American, African American, and Puerto Rican women were overwhelmingly targeted for involuntary, coercive, and compulsory sterilisation under early 20th century eugenics laws. The first compulsory sterilisation law was passed in Indiana in 1907, but compulsory sterilisation laws did not gain traction until the 1920s. In 1924, the US Supreme Court validated Virginia's sterilisation law with the landmark case Buck vs Bell. Carrie Buck, a young White woman institutionalised involuntarily after being raped and impregnated, challenged the state's decision to sterilise her for being eugenically unfit. The case went to the Supreme Court that ruled against her, with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr famously stating that “three generations of imbeciles are enough”. Buck vs Bell provided legal support for a growing movement across states to pass compulsory sterilisation laws that would lead to the sterilisation of an estimated 60 000 people. California had the largest sterilisation programme by far and had sterilised nearly 15 000 people by 1942. Eugenicist Harry Laughlin drafted the California law that would serve as a model for other states and for the sterilisation law in Nazi Germany. The states of North Carolina and Virginia each sterilised roughly 8000 people. Compulsory sterilisation laws targeted poor, disabled, and institutionalised people, and were disproportionately weaponised against people of colour. For example, of the nearly 8000 people sterilised through the North Carolina Eugenics Board, nearly 5000 of them were African American.

Even as states began to repeal compulsory sterilisation laws in the 1960s and 1970s, sterilisation abuse continued. Dorothy Roberts has shown in Killing the Black Body that some Black women were sterilised without their knowledge or consent into the 1970s and 1980s. Additionally, thousands of Native American women were subjected to involuntary sterilisations by the Indian Health Service in the 1960s and 1970s, causing deep psychological and cultural harm to the women, their families, and their communities. Sterilisation abuse continued for incarcerated women. After reports of forced sterilisations in Californian prisons, the state launched an investigation and determined that at least 144 incarcerated women were illegally sterilised between 2006 and 2010. Of those sterilisations, 24% were on Black women and 37% were on Latinx women. Although reversed, in 2017 a Tennessee judge ordered that incarcerated men and women could receive a 30-day reduction on their sentences if they submitted to a sterilisation procedure. And in 2020, allegations by a whistleblower of involuntary hysterectomies in a US Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility are concerning if confirmed.

Another notable violation of medical ethics was the infamous US Public Health Service “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male”, a 40-year study that began in 1932 and involved hundreds of Black men without their informed consent. Most of the men who took part in the study were poor sharecroppers from Macon County, AL, who laboured for White farmers under a system of debt peonage. Treatments for syphilis, notably penicillin, which became available in 1947, were withheld from these men, who were told they were being treated for “bad blood”. The shocking revelations of the Tuskegee study in the 1970s had a direct impact on the development of medical ethics and of regulations to protect human participants in research.

© 2020 Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse (CARASA) News, vol 3, no 9, 1979, New York, NY, USA, from the Joseph A Labadie Collection, University of Michigan/Image courtesy of the University of Michigan Joseph A Labadie Collection

The practice of involuntary medical experimentation continued to cast a long shadow on the medical community's relationship with Black Americans. Henrietta Lacks (1920–51) was a woman with cervical cancer whose HeLa cells contributed to advancing medical research in many areas, including immunology, oncology, and the development of the polio vaccine. Samples of Lacks' cancerous cells were taken during her treatment in the segregated ward of Johns Hopkins Hospital and were experimented on, reproduced, and disseminated without her knowledge or consent. Despite belated acknowledgment, financial compensation to her family has not been forthcoming.

Recently, attempts have been made to incorporate these histories of structural violence in bioethical approaches. Notable here is sociologist Ruha Benjamin's conceptualisation of informed refusal, the corollary to informed consent, as a way of understanding why, for example, Black patients may refuse to enrol in research studies and clinical trials. Histories of exploitation, marginalisation, and disempowerment are embedded in some personal decisions of non-participation and Benjamin argues for a rebuilding of institutional expectations that takes these structural forces into account.

In the realms of public health and disease intervention in the USA, people of colour have been historically penalised, oppressed, and harmed. For example, the American Civil War (1861–65) and the project of Reconstruction failed to ensure the free and equal existence for the formerly enslaved. Displaced, lacking basic necessities, and deprived of access to medical care—all of which were forms of structural violence that reproduced the experiences of slavery—they were disproportionately exposed to the ravages of infectious diseases such as smallpox, typhoid, and cholera. Although no longer enslaved, the material conditions of Black people's lives did not improve greatly in the period after emancipation. Freedom did not guarantee relief from the unhealthy living conditions and excess morbidity and mortality that existed under slavery. A powerful reminder of this is the fact that Lacks was born in the same cabin that her enslaved ancestors lived in. And such inequalities persist into the present. Housing, employment, education, and access to and quality of health care continue to shape racial health inequities. The disparity in infant mortality between White and Black people in the USA is even higher now than it was in the Antebellum period; hospitals serving predominantly Black and Latinx patients are underfunded; even certain diagnostic calculations such as pulmonary function and renal function tests incorporate race in the USA.

Infectious disease risk in Black communities has often been used historically as justification for forced home removals, increased surveillance (often accompanied by police violence), and unsolicited medical interventions, as well as calls for racial residential segregation. Tuberculosis, residential segregation, and racist attitudes to morality and health came together and were given spatial expression in the idea of the “Lung Block”. Whenever the term “Lung Block” was used, it was regarded as a space where the social ills of city life were distilled. In New York, where the phrase was coined in the early 20th century, the Lung Block demarcated Jewish, Irish, and Italian communities living in Manhattan's Lower East Side tenements. African Americans with tuberculosis were the focus of Lung Blocks in Baltimore and St Louis where, writes historian Taylor Desloge, “coercive and often discriminatory policies [were] designed to control and monitor patients”. Furthermore, at various times, public health departments were complicit in perpetuating racial stereotypes and placing the blame on the Black population for their health conditions.

These examples of historical racial injustices prompted responses from Black communities who challenged and actively subverted racist structures in medicine to care for their health. Time after time, White dominance was rejected and alternatives were proposed. While health care remained segregated, Black communities established, funded, and operated hospitals in underserved areas. Black physicians established the National Medical Association (NMA) in 1895 because the American Medical Association was segregated. Black hospitals and medical schools like Howard University and Meharry Medical College provided medical education and training when Black physicians were barred from other institutions. Black physicians, nurses, and students led the charge for the desegregation of medical institutions for the benefit of staff and patients. Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T Washington originated the National Negro Health Week in 1915 to focus on the poor health status of Black populations.

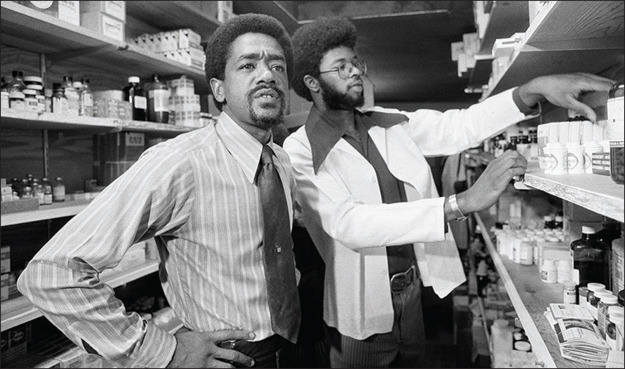

And there were many community-based initiatives. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the Black Panther Party organised free medical clinics and children's breakfasts. Also during this time, Black citizens in Pittsburgh ran the Freedom House Ambulance Service that pioneered paramedic-staffed emergency medical services and contributed to the development of national standards in emergency care. More recently, activists led by Black women and other people of colour have sought to meld the historically limited approach of reproductive rights with a social justice framework. Instead of a movement that largely emphasised access to abortion services, these activists have argued for access to safe childbirth through better maternal health care, anti-sterilisation efforts, and child care alongside access to reproductive health services, while also addressing the structural causes of poverty and inequality. Advocates tie reproductive justice to other movements that address forms of oppression and violence disproportionately impacting minority communities.

Bobby Seale and William Elder at a Black Panther Party free health clinic, 1972

© 2020 Robert Klein/Associated Press/Shutterstock

Black self-determination and resistance lay to waste the assumption that White supremacy in our medical past was simply “of its time”. Nor were Black, Indigenous, and people of colour passive victims of oppression. Black, Indigenous, and Latinx counter-narratives offer sustenance in the present confluence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement that a better future is possible. Placing these efforts at front and centre of medical history allows us to confront the shameful history of structural racial violence in medicine.

In sum, racism has not just been incidental to the history of American medicine, and much medical practice around the world, but entrenched in it. In The Souls of Black Folk (1903), W E B Du Bois begins the book by asking “How does it feel to be a problem?” Du Bois reframed the conversation of racial difference not from the perspective of those seeking explanations for supposed racial inferiority but from the perspectives of those subjected to racism. In this work and in his earlier study The Philadelphia Negro (1899), Du Bois introduced structural explanations for racial inequalities in health outcomes not rooted in specious beliefs about the biological inferiority of Black people but in the environmental, political, and socioeconomic circumstances that lead to ill health, prefacing latter 20th-century discussions on the social determinants of health. While education and history lessons give us awareness of the legacies of racism, we must also denaturalise our beliefs that racial differences are material indicators of significant biological and physiological differences. We must resist the re-biologisation of race. When we allow for racist assumptions to go unquestioned and the structures that allow the perpetuation of racist inequalities to go uncontested, we allow them to persist. Only when we consider racism and racial inequality to be persistent and implicit in our norms of practice and the ordering of society and not the exception, can we effectively begin to confront this issue.

Further reading

- Benjamin R. Informed refusal: toward a justice-based bioethics. Sci Technol Human Values. 2016;41:967–990. [Google Scholar]

- Berry DR. Beacon Press; Boston, MA: 2017. The price for their pound of flesh: the value of the enslaved from womb to grave in the building of a nation. [Google Scholar]

- Bioethics.net; Bioethics and race #BlackBioethics. #BlackBioethics Toolkit. 2020. http://www.bioethics.net/2020/06/toolkit-bioethics-and-race-blackbioethics

- Cooper Owens D. University of Georgia Press; Athens, GA: 2018. Medical bondage: race, gender, and the origins of American gynecology. [Google Scholar]

- Desloge TH. Creating the Lung Block: racial transition and the “New Public Health” in a St Louis neighborhood, 1907–1940. Missouri Historical Rev. 2017;111:124–150. [Google Scholar]

- Dula A. Toward an African-American perspective on bioethics. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1991;2:259–269. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ML. Pittsburgh's Freedom House Ambulance Service: the origins of emergency medical services and the politics of race and health. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2019;74:440–466. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/jrz041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer PE, Nizeye B, Stulac S, Keshavjee S. Structural violence and clinical medicine. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev Soc Sci Res Race. 2011;8:115–132. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayapal P, Chu J, Nadler J. Congress of the United States Letter. Sept 15, 2020. http://jayapal.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/DHS-IG-Letter-9.15.pdf

- Johnson AS, Mitchell EA, Nuriddin A. Syllabus: a history of anti-Black racism in medicine. AAIHS. Aug 12, 2020 https://www.aaihs.org/syllabus-a-history-of-anti-black-racism-in-medicine/ [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence J. The Indian Health Service and the sterilization of Native American women. Am Indian Quart. 2000;24:400–419. doi: 10.1353/aiq.2000.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo PA. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2010. Three generations, no imbeciles: eugenics, the Supreme Court and Buck v. Bell. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney G. Washington and Welch talk about race: public health, history and the politics of exclusion. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1317–1328. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustakeem SM. University of Illinois Press; Urbana, IL: 2016. Slavery at sea: terror, sex, and sickness in the Middle Passage. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J. NYU Press; New York: 2003. Women of color and the reproductive rights movement. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Link BG. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health?”. Ann Rev Sociol. 2015;41:311–330. [Google Scholar]

- Paul K. ICE detainees faced medical neglect and hysterectomies, whistleblower alleges. The Guardian. Sept 14, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DE. 1st edn. Vintage books; New York: 1997. Killing the Black body: race, reproduction, and the meaning of liberty. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill, NC: 2009. Infectious fear: politics, disease, and the health effects of segregation. [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe RJ., Jr Foreword: racism and health. Ethnicity Dis. 2020;30:369–372. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.3.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusert B. “A study in nature”: the Tuskegee experiments and the new South Plantation. J Med Humanit. 2009;30:155–171. doi: 10.1007/s10912-009-9086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skloot R. Broadway Paperbacks; New York: 2011. The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks. [Google Scholar]

- Stern AM. Sterilized in the name of public health: race, immigration, and reproductive control in modern California. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1128–1138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whatcott J. No selves to consent: women's prisons, sterilization, and the biopolitics of informed consent. Signs J Women Culture Soc. 2018;44:131–153. [Google Scholar]

- White AIR. Historical linkages: epidemic threat, economic risk, and xenophobia. Lancet. 2020;395:1250–1251. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30737-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association . American Public Health Association; 2018. Addressing law enforcement as a public health issue: the 2018 statement.https://www.endingpoliceviolence.com/ [Google Scholar]