Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS including e-cigarettes) are rapidly evolving in the U.S. marketplace. This study reports cross-sectional prevalence and longitudinal pathways of ENDS use across 3 years, among youth (12–17 years), young adults (18–24 years), and adults 25+ (25 years and older) in the U.S.

DESIGN:

Data were from the first three waves (2013–2016) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, a nationally representative, longitudinal cohort study of U.S. youth and adults. Respondents with data at all three waves (youth, N = 11,046; young adults, N = 6,478; adults 25+, N = 17,188) were included in longitudinal analyses.

RESULTS:

Weighted cross-sectional ever use of ENDS increased at each wave. Across all three waves, young adults had the highest percentages of past 12-month, past 30-day (P30D), and daily P30D ENDS use compared to youth and adults 25+. Only about a quarter of users had persistent P30D ENDS use at each wave. Most ENDS users were polytobacco users. Exclusive Wave 1 ENDS users had a higher proportion of subsequent discontinued any tobacco use compared to polytobacco ENDS users who also used cigarettes.

CONCLUSIONS:

ENDS use is most common among young adults compared to youth and adults 25+. However, continued use of ENDS over 2 years is not common for any age group. Health education efforts to reduce the appeal and availability of ENDS products might focus on reducing ENDS experimentation, and on reaching the smaller subgroups of daily ENDS users to better understand their reasons for use.

INTRODUCTION

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), including e-cigarettes, are battery-operated products that produce an aerosolized mixture containing nicotine, flavorings, propylene glycol, glycerin, and/or other additives that the user inhales.1 In the U.S., the tobacco marketplace has seen a rapidly evolving array of ENDS products.2 U.S. representative cross-sectional surveys have shown ever use of e-cigarettes is significantly increasing among youth (12–17 years).3–9 For both high school students and middle school students, ENDS have been the most frequently used tobacco products since 2014.4,7,8,10,11 The 2011–2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) data show significant nonlinear increases in past 30-day (P30D) ENDS use among high school students from 1.5% to 20.8% and among middle school students from 0.6% to 4.9%.8 Aggregated initiation rates of past 12-month (P12M) ENDS use across the approximate 3-years’ time span (2013–2016) of Wave 1 to Wave 3 (W1-W3) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study indicate that most ENDS initiation occurs among youth (ages 12–17) and young adults (ages 18–24) (youth, 22.7%; young adults, 28.4%; adults 25+, 6.7%) and that compared with other tobacco products, ENDS have shown the highest initiation rates during this time period.11 P30D ENDS use has been reported to be less frequent compared to combustible cigarette use, with the vast majority of ENDS use being nondaily.13–15

Most U.S. youth and adult ENDS users are dual or polytobacco product users.1,16,17 Among U.S. youth,16,18 P30D use of cigarettes and ENDS is the most common product combination (15.0%).17 Use of ENDS with combustible cigarettes can result in continued exposure to the toxic combustion products of traditional cigarettes and exposure to unique constituents in ENDS (e.g., flavors, humectants).19,20 Tobacco users who use both ENDS and combustible cigarettes may be using ENDS to gradually substitute ENDS for cigarettes with the intention to reduce or quit cigarettes, or may be adding ENDS to existing cigarette use as a way to cope with smoke-free policies that create discomfort due to nicotine dependence.19 Data on the long-term health effects of dual combustible cigarette and ENDS use are limited, with some studies showing no reduced risk from dual use compared to cigarette smoking alone,21–23 and others suggesting dual use may be associated with more risk of negative health effects.24–26

The first aim of this study is to examine differences between each of the first three waves of cross-sectional weighted estimates of ENDS use from the PATH Study (2013–2016). Differences over time are reported for different definitions of ENDS use, such as ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D ENDS use for U.S. youth, young adults, and adults 25+. Drawing from the first three waves of longitudinal within-person data from the PATH Study, the second aim is to examine age group differences in W1-W2-W3 pathways of persistent use, discontinued use, and reuptake of ENDS among W1 P30D ENDS users. The final aim of these analyses is to compare longitudinal transition pathways among W1 exclusive ENDS users, W1 ENDS polytobacco users including cigarettes (ENDS polytobacco use w/CIGS), and W1 ENDS polytobacco users who do not use cigarettes (ENDS polytobacco use w/o CIGS) to understand product transitions. Comparing longitudinal transitions among exclusive versus polytobacco ENDS users will advance our understanding of patterns of polytobacco use in the US and critical product transitions, such as switching and complete tobacco cessation. These analyses will lay the groundwork for more robust evaluations of the potential health risks and benefits of ENDS use at the population level.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

The PATH Study is an ongoing, nationally representative, longitudinal cohort study of youth (ages 12–17) and adults (ages 18 or older) in the U.S. Self-reported data were collected using audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) administered in English and Spanish. Further details regarding the PATH Study design and W1 methods are published elsewhere.27,28 At W1, the weighted response rate for the household screener was 54.0%. Among screened households, the overall weighted response rate was 78.4% for youth and 74.0% for adults at W1, 87.3% for youth and 83.2% for adults at W2, and 83.3% for youth and 78.4% for adults at W3. Details on interview procedures, questionnaires, sampling, and weighting and information on accessing the data are available at https://doi.org/10.3886/Series606. The study was conducted by Westat and approved by the Westat Institutional Review Board. All participants ages 18 and older provided informed consent, with youth participants ages 12 to 17 providing assent while their parent/legal guardian provided consent.

The current study reports cross-sectional estimates from 13,651 youth and 32,320 adults who participated in W1 (data collected September 12, 2013 through December 14, 2014), 12,172 youth and 28,362 adults at W2 (October 23, 2014 through October 30, 2015), and 11,814 youth and 28,148 adults at W3 (October 19, 2015 to October 23, 2016). The differences in the number of completed interviews between W1, W2, and W3 reflect attrition due to nonresponse, mortality, and other factors, as well as youth who enroll in the study at W2 or W3.27 We also report longitudinal estimates from W1 youth (N = 11,046), W1 young adults (N = 6,478), and W1 adults 25+ (N = 17,188) with data collected at all three waves. See Supplemental Figure 1 for a detailed description of the analytic sample for longitudinal analysis.

Measures

Tobacco use

At each wave, adults and youth were asked about their tobacco use behaviors for cigarettes, ENDS, traditional cigars, cigarillos, filtered cigars, pipe tobacco, hookah, snus pouches, other smokeless tobacco (loose snus, moist snuff, dip, spit, or chewing tobacco), and dissolvable tobacco. Participants were asked about “e-cigarettes” at W1 and “e-products” (e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes, and e-hookah) at W2 and W3; all electronic products are referred to as ENDS in this paper. In addition, youth were asked about their use of bidis and kreteks but these data were not included in the analyses due to small sample sizes.

At W1, ENDS were described as “e-cigarettes that look like regular cigarettes, but are battery-powered and produce vapor instead of smoke. Some common brands include NJOY, Blu, and Smoking Everywhere.” At W2 and W3, ENDS were described as “electronic nicotine products such as e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes, e-hookahs, and personal vaporizers, as well as vape pens and hookah pens that are battery-powered, use nicotine fluid rather than tobacco leaves, and produce vapor instead of smoke. Some common brands include Fin, NJOY, Blu, e-Go and Vuse.” Participants were shown generic pictures of the product at all three waves.

Outcome measures

Cross-sectional definitions of use included ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D use. Longitudinal outcomes included persistent ENDS use, discontinued ENDS use, and reuptake of ENDS use, as well as transitions among exclusive and polytobacco ENDS users. The definition of each outcome is included in the footnote of the table/figure in which it is presented.

Analytic Approach

To address Aim 1, weighted cross-sectional prevalence of ENDS use was compared across waves for each age group for ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D use. For Aim 2, irrespective of other tobacco product use, longitudinal W1-W2-W3 transitions in P30D ENDS use were compared by age group within three separate user groups persistent any P30D ENDS use (defined as continued P30D ENDS use at W2 and W3), discontinued any P30D ENDS use (stopped ENDS use at W2 and W3 or just W3), and reuptake of any P30D ENDS use (used ENDS at W1, discontinued ENDS use at W2, and used ENDS again at W3). Finally, to address Aim 3, longitudinal W1-W2-W3 ENDS use pathways that flow through seven mutually exclusive and exhaustive transition categories were examined for W1 P30D exclusive ENDS use, W1 P30D ENDS polytobacco use w/CIGS, and W1 P30D ENDS polytobacco use w/o CIGS (see Supplemental Figure 2). For each aim, weighted t-tests were conducted on differences in proportions to assess statistical significance. To correct for multiple comparisons, Bonferroni post-hoc tests were conducted. Given that cigarettes are the most commonly used tobacco product with the most robust evidence base of potentially harmful health consequences,6 two polytobacco use groups were examined separately to compare longitudinal transitions among polytobacco users who use and do not use cigarettes. These pathways represent building blocks that may be aggregated to reflect higher-level behavioral transitions.

Cross-sectional estimates (Aim 1) were calculated using PATH Study cross-sectional weights for W1 and single-wave (pseudo-cross-sectional) weights for W2 and W3. The weighting procedures adjusted for complex study design characteristics and nonresponse. Combined with the use of a probability sample, the weighted data allow these estimates to be representative of the noninstitutionalized, civilian, resident U.S. population aged 12 or older at the time of each wave. Longitudinal estimates (Aims 2 and 3) were calculated using the PATH Study W3 all-waves weights. These weighted estimates are representative of the resident U.S. population aged 12 and older at the time of W3 (other than those who were incarcerated) who were in the civilian, noninstitutionalized population at W1.

All analyses were conducted using SAS Survey Procedures, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Variances were estimated using the balanced repeated replication (BRR) method29 with Fay’s adjustment set to 0.3 to increase estimate stability.30 Analyses were run on the W1-W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8). Estimates with low precision (fewer than 50 observations in the denominator or with a relative standard error greater than 0.30) were flagged and are not discussed in the Results.

RESULTS

Cross-Sectional Weighted Prevalence

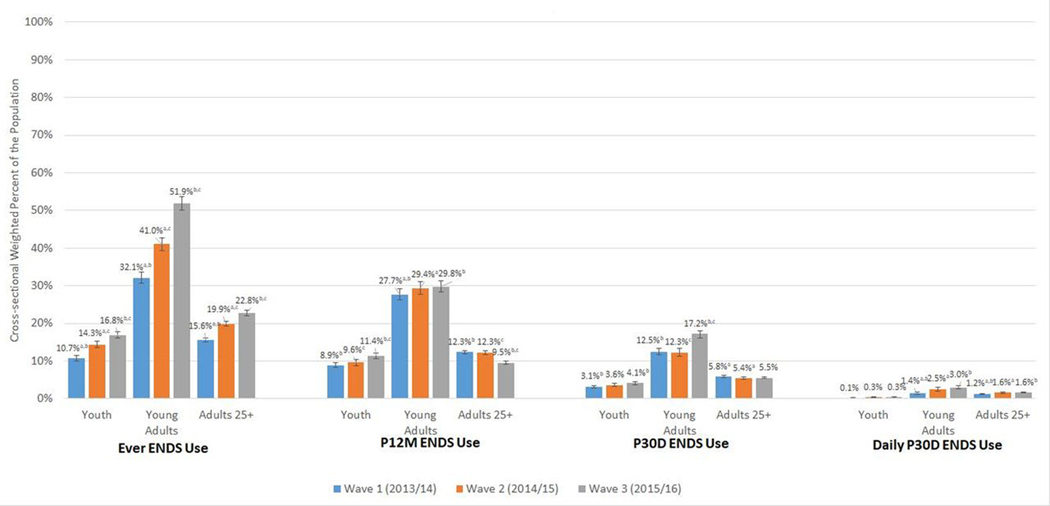

As shown in Figure 1, across age groups, ever use of ENDS significantly increased at each wave. Prevalence of P12M ENDS use did not change in young adults across waves, although among youth it increased 2.5% from W1 to W3, and among adults 25+ it dropped 2.8% at W3 from W1 and W2. Prevalence of P30D use did not change in youth or adults 25+ between W2 and W3, but among young adults P30D use increased by 4.9% at W3 compared to W2. Daily P30D ENDS use among young adults increased from 1.4% (95% CI: 1.2–1.7) at W1 to 2.5% (95% CI: 2.1–3.1) at W2 and to 3% (95% CI: 2.6–3.4) at W3. Across all three waves, young adults had the highest percentages of ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D ENDS use. Described differences are absolute percent differences, not relative percent differences.

Figure 1:

Cross-sectional weighted percent of ever, P12M, P30D and daily P30D electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) use among youth, young adults and adults 25+ in W1, W2 and W3 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study.

Abbreviations: P12M = past 12-month; P30D = past 30-day; ENDS* = electronic nicotine delivery system; W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3 W1/W2/W3 ever ENDS use unweighted Ns: youth (ages 12–17) = 1,451/1,715/1,930; young adults (ages 18–24) = 3,887/3,968/4,702; adults 25+ (ages 25 and older) = 7,634/8,065/8,634W1/W2/W3 P12M ENDS use unweighted Ns: youth = 1,193/1,130/1,296; young adults = 3,356/2,777/2,802; adults 25+ = 6,062/4,957/3,741W1/W2/W3 P30D ENDS use unweighted Ns: youth = 418/415/454; young adults = 1,516/1,180/1,630; adults 25+ = 2,914/2,199/2,163W1/W2/W3 daily P30D ENDS use unweighted Ns: youth = 20/37/29; young adults =170/240/280; adults 25+ = 619/639/642 X-axis shows four categories of ENDS use (ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D). Y-axis shows weighted percentages of W1, W2, and W3 users. Sample analyzed includes all W1, W2, and W3 respondents at each wave. All respondents with data at one wave are included in the sample for that wave's estimate and do not need to have complete data at all three waves. The PATH Study cross-sectional (W1) or single-wave weights (W2 and W3) were used to calculate estimates at each wave.

Ever ENDS use is defined as having ever used ENDS, even once or twice in lifetime. P12M ENDS use is defined as any ENDS use within the past 12 months. P30D ENDS use is defined as any ENDS use within the past 30 days. Daily P30D ENDS use is defined as use of ENDS on all 30 of the past 30 days. All use definitions refer to any use that includes exclusive or polytobacco use of ENDS.

a denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 and W2

b denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 and W3

c denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W2 and W3

*Respondents were asked about “e-cigarettes” at W1 and “e-products” (i.e., e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes, and e-hookah) at W2 and W3.

The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% confidence intervals.

Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

Longitudinal Weighted W1-W2-W3 Pathways

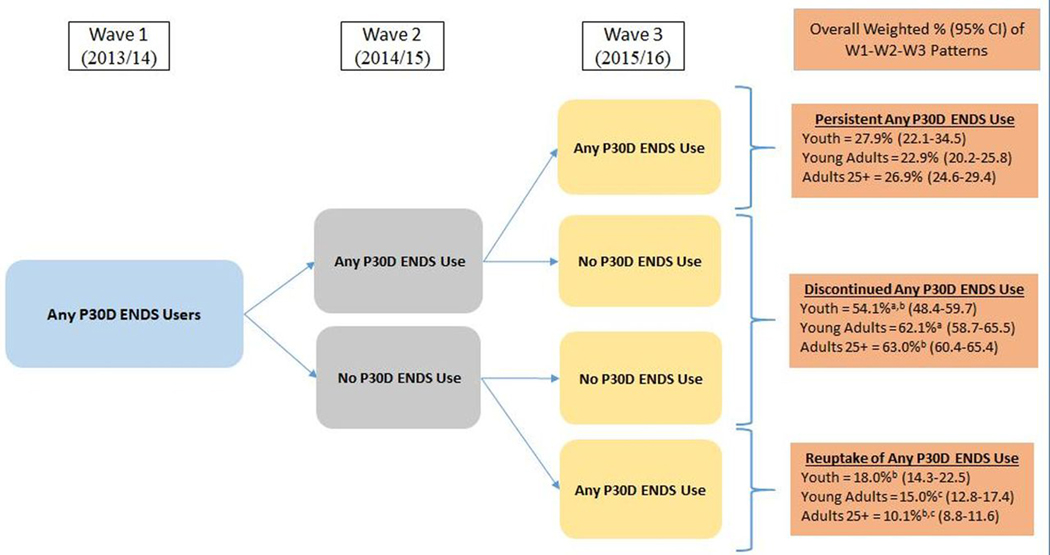

Among any P30D ENDS users at W1

Among those with data at all three waves, 3.0% (95% CI: 2.6–3.4) of youth, 12.5% (95% CI: 11.6–13.5) of young adults, and 5.8% (95% CI: 5.5–6.1) of adults 25+ had P30D ENDS use at W1. As illustrated in Figure 2, persistent P30D ENDS use, defined as P30D ENDS use at all three waves, irrespective of concurrent use of other products, was similar across each age group. Discontinued ENDS use, defined as stopping ENDS use at W2 or W3 among W1 P30D ENDS users, was higher among young adults (62.1% [95% CI: 58.7–65.5]) and adults 25+ (63.0% [95% CI: 60.4–65.4]) compared to youth (54.1% (95% CI: 48.4–59.7). ENDS reuptake, defined as ENDS use at W1, no ENDS use at W2, and ENDS use again at W3, was lowest among adults 25+ (10.1% [95% CI: 8.8–11.6]) compared to youth (18.0% [95% CI: 14.3–22.5]) and young adults (15.0% [95% CI: 12.8–17.4]).

Figure 2:

Patterns of W1-W2-W3 persistent any P30D ENDS use, discontinued any P30D ENDS use and reuptake of any P30D ENDS use among W1 any P30D ENDS users.

Abbreviations: W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3; P30D = past 30-day; ENDS* = electronic nicotine delivery system; CI = confidence interval Wave 1 any P30D ENDS use weighted percentages (95% CI) out of total U.S. population: youth (ages 12–17) = 3.0% (2.6–3.4); young adults (ages 18–25) = 12.5% (11.6–13.5); adults 25+ (ages 25 and older) = 5.8% (5.5–6.1)Analysis included W1 youth, young adults, and adults 25+ P30D ENDS users with data at all three waves. Respondent age was calculated based on age at W1. W3 longitudinal (all-waves) weights were used to calculate estimates. These rates vary slightly from those reported in Figure 1 or Supplemental Table 1 because this analytic sample in Figure 2 includes only those with data at each of the three waves to examine weighted longitudinal use and non-use pathways.

Any P30D ENDS use was defined as any ENDS use within the past 30 days. Respondent could be missing data on other P30D tobacco product use and still be categorized into the following three groups:1) Persistent any P30D ENDS use: Defined as exclusive or ENDS polytobacco use at W2 and W3.2) Discontinued any P30D ENDS use: Defined as any non-ENDS tobacco use or no tobacco use at either W2 and W3 or just W3.3) Reuptake of any P30D ENDS use: Defined as discontinued ENDS use at W2 and any ENDS use at W3.

a denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between youth and young adults

b denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between youth and adults 25+

c denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between young adults and adults 25+

*Respondents were asked about “e-cigarettes” at W1 and “e-products” (i.e., e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes, and e-hookah) at W2 and W3.

The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% CIs.

Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files(https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

Among Wave 1 P30D ENDS user types (exclusive, polytobacco users w/CIGS, and polytobacco users w/o CIGS)

Among the longitudinal sample of W1 P30D ENDS users, most were ENDS users who also used another tobacco product: 63.8% (95% CI: 58.8–68.5) of youth, 87.4% (95% CI: 85.0–89.35) of young adults, and 86.2% (95% CI: 84.5–87.7) of adults 25+. Among ENDS polytobacco users, 70.6% (95% CI: 63.1–77.1) of youth, 84.7% (95% CI: 82.1–86.9) of young adults, and 94.8% (95% CI: 93.4–95.9) of adults 25+ also used cigarettes. Less than half of youth and young adult ENDS users who also used cigarettes used only cigarettes and e-cigarettes, but most adults 25+ (69.4% [95% CI: 66.6–72.0]) with ENDS polytobacco use w/CIGS used only cigarettes and e-cigarettes.

To address the third aim and compare user types, 49 possible W1-W2-W3 pathways were examined across seven mutually exclusive categories (see conceptual map in Supplemental Figure 2) among three separate W1 user type categories: 1) P30D exclusive ENDS users (Supplemental Table 1a), 2) P30D ENDS polytobacco users w/CIGS (Supplemental Table 1b), and 3) P30D ENDS polytobacco users w/o CIGS (Supplemental Table 1c). Pathways from Supplemental Table 1a–c estimate broad behavioral transitions such as persistent use type, discontinued all tobacco use, and tobacco use reuptake which were compared across the three user types.

Among Youth (Table 1), W1 exclusive P30D ENDS users had higher rates of discontinued all tobacco use (53.9% [95% CI: 44.6–63.0]) compared to W1 P30D ENDS polytobacco users w/CIGS (17.9% [95% CI: 12.2– 25.6]) and W1 P30D ENDS polytobacco users w/o CIGS (28.3% [95% CI: 16.6– 43.8]).

Table 1:

Transitions in P30D Product Use at W2 and W3 Among W1 P30D ENDS Users.

| Youth | Young Adults | Adults 25+ | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 Exclusive ENDS Use | W1 ENDS PTU w/CIGS | W1 ENDS PTU w/o CIGS | W1 Exclusive ENDS Use | W1 ENDS PTU w/CIGS | W1 ENDS PTU w/o CIGS | W1 Exclusive ENDS Use | W1 ENDS PTU w/CIGS | W1 ENDS PTU w/o CIGS | ||||||||||

| Mutually Exclusive Pathways | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI |

|

Persistent ENDS use type at all waves Continuing the same W1 use type (exclusive, PTU w/CIGS, or PTU w/o CIGS) at each wave |

3.7†a | (1.1–11.6) | 26.3a | (18.9–35.4) | N/A | N/A | 4.3†a | (1.5–11.6) | 19.2a,c | (16.5–22.3) | 9.5†c | (4.7–18.6) | 34.3a,b | (29.2–39.9) | 18.8a,c | (16.9–21.0) | 5.7†b,c | (2.4–13.1) |

|

ENDS use type reuptake The same broad use type (exclusive or PTU) at W1 and W3 (but a different tobacco use at W2) |

4.6†a,b | (1.7–12.1) | 21.8a | (14.9–30.6) | 39.0b | (25.9–54.0) | 5.9†a,b | (3.0–11.4) | 15.6a,c | (12.9–18.8) | 27.6b,c | (20.6–35.9) | 7.1b | (4.3–11.6) | 11.7 | (9.8–13.9) | 19.2b | (11.7–29.8) |

|

ENDS use type transition Transition from W1 exclusive use to PTU by W3, or transition from W1 PTU to exclusive use by W3 (without discontinuing all tobacco use at W2) |

18.7a,b | (12.0–28.0) | 2.5†a | (0.8–7.7) | 5.7†b | (1.4–20.7) | 10.5a | (6.2–17.2) | 3.4a | (2.1–5.3) | 4.1† | (1.8–8.9) | 9.5 | (6.2–14.3) | 5.4 | (4.2–6.9) | 5.5† | (2.7–10.7) |

|

Switch or discontinue ENDS use, but continue other tobacco use W1 exclusive user who switches to another tobacco product by W3 or W1 polytobacco user that discontinues ENDS use by W3 but uses another tobacco product (without discontinuing all tobacco use at W2) |

6.9†a | (3.5–13.1) | 26.5a | (19.2–35.5) | 18.2† | (9.3–32.7) | 22.5a | (15.6–31.2) | 44.8a,c | (40.8–48.8) | 28.0c | (19.9–37.9) | 9.3a,b | (6.4–13.5) | 54.1a | (51.2–57.0) | 40.1b | (27.5–54.2) |

|

Tobacco use reuptake W1 users who discontinue all tobacco use at W2 and use again at W3 |

12.2 | (6.8–20.9) | 5.0† | (2.2–10.9) | 8.8† | (3.5–20.2) | 11.0b | (6.8–17.5) | 5.1 | (3.5–7.3) | 3.6†b | (1.4–8.5) | 5.7a,b | (3.5–9.1) | 1.7a | (1.1–2.5) | 0.7†b | (0.1–5.1) |

|

Discontinue all tobacco use W1 users who discontinue all tobacco use at either W2 and W3 or just W3 |

53.9a,b | (44.6–63.0) | 17.9a | (12.2–25.6) | 28.3b | (16.6–43.8) | 45.8a,b | (35.3–56.5) | 11.9a,c | (9.5–14.9) | 27.2b,c | (18.8–37.6) | 34.0a | (28.3–40.1) | 8.3a,c | (6.9–9.9) | 28.8c | (18.7–41.4) |

Notes:

Abbreviations: P30D = past 30-day; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3; W1 = Wave 1; ENDS* = electronic nicotine delivery system; polytobacco use = PTU; w/ = with; CIGS = cigarettes; w/o = without; CI = confidence interval; N/A = not applicable

Analysis included youth (ages 12–17), young adult (ages 18–24), and adult 25+ (ages 25 and older) W1 P30D ENDS users with data at all three waves. Respondent age was calculated based on age at W1. W3 longitudinal (all-waves) weights were used to calculate estimates. All tobacco use is defined as P30D use. Use type refers to exclusive use, PTU w/CIGS, or PTU w/o CIGS.

denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 Exclusive ENDS Use and W1 ENDS PTU w/CIGS

denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 Exclusive ENDS Use and W1 ENDS PTU w/o CIGS

denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 ENDS PTU w/CIGS and W1 ENDS PTU w/o CIGS

Respondents were asked about “e-cigarettes” at W1 and “e-products” (i.e., e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes, and e-hookah) at W2 and W3.

The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% CIs.

Estimate should be interpreted with caution because it has low statistical precision. It is based on a denominator sample size of less than 50, or the coefficient of variation of the estimate or its complement is larger than 30%.

Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

Among Young Adults (Table 1), W1 exclusive P30D ENDS users had higher rates of discontinued all tobacco use (45.8% [95% CI: 35.3–56.5]) compared to W1 P30D ENDS polytobacco users w/CIGS (11.9% [95% CI: 9.5– 14.9]) and W1 P30D ENDS polytobacco users w/o CIGS (27.2% [95% CI: 18.8– 37.6]). Discontinuing ENDS use but continuing other tobacco use was the highest among W1 ENDS polytobacco users w/CIGS (44.8% [95% CI: 40.8–48.8]) than ENDS polytobacco users w/o CIGS (28.0% [95% CI: 19.9– 37.9]) and exclusive ENDS users who switch to other tobacco products by W3 (22.5% [95% CI: 15.6–31.2]).

Among Adults 25+ (Table 1), W1 P30D ENDS polytobacco users w/CIGS had the lowest rates of discontinued all tobacco use (8.3% [95% CI: 6.9– 9.9]) compared to W1 exclusive P30D ENDS users (34.0% [95% CI: 28.3– 40.1]) and polytobacco users w/o CIGS (28.8% [95% CI: 18.7– 41.4]). Similar to young adults, switching from exclusive ENDS to other tobacco products was the lowest among W1 exclusive ENDS users (9.3% [95% CI: 6.4– 13.5]) compared to W1 ENDS polytobacco users w/CIGS (54.1% [95% CI: 51.2– 57.0]) and ENDS polytobacco users w/o CIGS (40.1% [95% CI: 27.5– 54.2]). Persistent use was higher among W1 exclusive ENDS users (34.3% [95% CI: 29.2–39.9]) compared to ENDS polytobacco users w/CIGS (18.8% [95% CI: 16.9–21.0]).

DISCUSSION

As rates of smoking cigarettes continue to decline among U.S. youth and adults,7,31 nationally representative cross-sectional surveys have shown an increase in both initiation (new ever use) and P30D ENDS use over the past 5 years, especially among youth and young adults.3,7,21,32 Consistent with other reports, data from the first three waves of the PATH Study found that ever use of ENDS increased at each wave for youth, young adults, and adults 25+. ENDS product availability, device sophistication, e-liquid variability (e.g., nicotine salts), and marketing also increased from 2013–2016, making access and product awareness a potential reason for increased new ever use over this time period.33–37

Differences in trends of ENDS use based on the definition of use were also noted. For example, prevalence of P12M ENDS use did not change among young adults across waves, although among youth it increased 2.5% from W1 to W3, and among adults 25+ it dropped 2.8% at W3. Prevalence of P30D use did not change in youth or adults 25+ from W2 to W3, but among young adults, there was a 4.9% increase of P30D ENDS use at W3 compared to W2. While generally less than 3% of P30D ENDS use is daily, daily P30D ENDS use among young adults increased incrementally at each wave (W1, 1.4% (95% CI:1.2–1.7); W2, 2.5% (95% CI: 2.1– 3.1); W3, 3.0% (95% CI: 2.6–3.4)); prevalence did not change in youth or adults 25+. Extending previous reports,1,3 compared to youth and older adults, young adults had the highest percentages of P12M, P30D, and daily P30D ENDS use at each of the three waves. Thus, young adults are a subpopulation of significant concern if these rising rates of use lead to the potential harms of early exposure to e-cigarette toxins and the well-established harms of subsequent combustible tobacco use.19

Longitudinal patterns across the three waves revealed that P30D ENDS use is not stable, with only about a quarter of users having persistent P30D ENDS use at each wave. The most common pattern of use across the three waves was marked by discontinued use, with about half of youth and about 60% of all adults discontinuing W1 ENDS use for the next 2 years at W2 and W3 or for 1 year at W3. Less than 20% (18.0% [95% CI: 14.3–22.5]) of youth, 15.0% (95% CI: 12.8–17.4) of young adults, and 10.1% (95% CI: 8.8– 11.6) of adults 25+ who were W1 P30D ENDS users discontinued ENDS at W2 and then returned to P30D ENDS use at W3. These findings are similar to Coleman et al.’s findings, in which half of adult e-cigarette users at W1 had discontinued their use of e-cigarettes at W2 and approximately half of W1 dual e-cigarette and cigarette users had discontinued ENDS use at W2.38 Thus, despite rising rates of ever use of ENDS, patterns over this 3-year period (2013–2016) showed that ENDS use does not persist among most who try the product.

The majority of ENDS users in each age group also used another tobacco product. There were notably different patterns of ENDS use for exclusive versus polytobacco users (Table 1). Among all age groups, more W1 exclusive ENDS users stopped using all tobacco products compared to those with W1 ENDS polytobacco use w/CIGS. Patterns of use among W1 ENDS polytobacco users w/CIGS were marked by inconsistent use across the waves and discontinued ENDS use but continued use of other tobacco products. Other studies using PATH Study data have shown similar trends in discontinued use between dual users of ENDS and cigarettes compared to exclusive ENDS users.38 Moreover, persistent use of ENDS polytobacco use w/CIGS was more common than ENDS polytobacco use w/o CIGS (Table 1). These results suggest that ENDS users also using other tobacco products have patterns of use that are not likely to include quitting all tobacco and that these users are more likely to persist either using ENDS with cigarettes or switching to other tobacco products.

Longitudinal patterns of ENDS use over the first three waves of the PATH Study (2013–2016) differ notably from trends presented in parallel reports of PATH Study data focused on other tobacco products.39–42 The most common ENDS use patterns over 3 years were either discontinued use, inconsistent use, or switching to other products. In contrast, combustible cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products, products that have been on the market in the U.S. for decades, were used persistently across the waves. Products with rising market presence in the U.S., such as hookah and cigars (including little cigars and cigarillos), have more inconsistent patterns of use similar to those of ENDS, particularly among young adults. The literature reports that product characteristics (e.g., flavors),43 cost and taxation,44,45 access in social settings such as vape shops and hookah bars,46 as well as differences in targeted marketing and risk perceptions,47–49 may be driving differences between traditional products and these emerging products, which are poised for intervention to reduce young adults’ attraction to these emerging products.

Limitations

These data predate the rapid increase in ENDS from 2017–2018 among youth2,8,21 and transition patterns among youth may be different over time. Specifically, data collection occurred before the explosive growth of Juul, which delivers a high dose of nicotine and therefore has a greater potential for addictiveness compared to other ENDS brands, and may reduce rates of discontinued use and increase rates of reuptake.50–53 The potential for recall bias from a self-report questionnaire is noted. Additionally, the PATH Study asked about “e-cigarettes” (the predominant e-product on the market) at W1 and “e-products” at W2 and W3 which may have resulted in misclassification of ENDS product-specific use between W1 and the subsequent waves. Weighted longitudinal analyses excluded participants who were missing data at one of the waves. The extent of missing data and the small number of observations for low-prevalence pathways may limit interpretation. Other reports suggest that the frequency and intensity of ENDS use may be a critical factor in pathways such as discontinued use and switching.18,21,32 Future studies can examine adjusted models to determine which factors predict priority pathways, including frequency of use and other factors that may drive different patterns of use. Kasza et al.53,54 and Edwards et al.55 examine demographic correlates of initiation, cessation, and relapse to further explore predictors of these critical outcomes.

Summary and Implications

Evidence to-date suggests that ever use of ENDS among youth may contribute to ever combustible tobacco use. This report identifies patterns of P30D ENDS use that are unstable, with common longitudinal pathways of quitting all tobacco, switching to other products, or ENDS polytobacco use with cigarettes. While ever use of ENDS has increased among U.S. youth and young adults,12 only a small percentage of the population (less than 1.0% of youth, 3.0% of young adults, and 1.6 % of adults 25+) were using ENDS daily. Differences in patterns of use among exclusive ENDS users and ENDS polytobacco users were identified, suggesting it is important to make these distinctions. Health education efforts to reduce the appeal and availability of ENDS products might focus on reducing ENDS experimentation, and on reaching the smaller subgroups of ENDS users who are using daily to better understand their reasons for use.

Supplementary Material

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS:

This study includes a three-wave examination of ENDS use in the U.S. across multiple definitions of use for three different age groups. Across all three waves, young adults had the highest percentages of P12M use, P30D, and daily P30D ENDS use compared to youth and adults 25+.

While rates of ever use of ENDS increased within each age group, only young adults increased P30D use between W2 and W3. Daily P30D use remained very low (less than 3%) for all age groups.

Longitudinal pathways indicate that P30D ENDS use is not stable, as only about a quarter of users showed persistent P30D ENDS use across the three waves.

The majority of ENDS use is polytobacco use, and ENDS polytobacco users who also use cigarettes are less likely to stop using tobacco 2 or 3 years later compared to exclusive ENDS users.

Acknowledgments

Funding statement: This manuscript is supported with Federal funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Center for Tobacco Products, Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, under a contract to Westat (Contract No. HHSN271201100027C).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

Financial disclosure: Wilson Compton reports long-term stock holdings in General Electric Company, 3M Company, and Pfizer Incorporated, unrelated to this manuscript. No financial disclosures were reported by the other authors of this paper.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen Total US xAOC/Convenience Database & Wells Fargo Securities LLC in Wells Fargo Securities. Nielsen: Tobacco ‘All Channel’ Data Through 8/11. August 21, 2018.

- 3.Jamal A, Gentzke A, Hu S, et al. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students-United States, 2011–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(23):597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE. Youth tobacco product use in the United States. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014:943. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang TW, Gentzke A, Sharapova S, Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Jamal A. Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gentzke AS, Creamer M, Cullen KA, et al. Vital Signs: Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry KM, Fetterman JL, Benjamin EJ, et al. Association of Electronic Cigarette Use With Subsequent Initiation of Tobacco Cigarettes in US Youths. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(2):e187794-e187794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh T, Arrazola R, Corey C, et al. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students--United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(14):361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students-United States, 2011–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(14):381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanton CA, Sharma E, Seaman EL, et al. Initiation of any tobacco and five tobacco products across 3 years among youth, young adults, and adults in the United States: findings from the path study waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s178–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu S-H, Gamst A, Lee M, Cummins S, Yin L, Zoref L. The use and perception of electronic cigarettes and snus among the US population. PloS one. 2013;8(10):e79332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vardavas CI, Filippidis FT, Agaku IT. Determinants and prevalence of e-cigarette use throughout the European Union: a secondary analysis of 26 566 youth and adults from 27 Countries. Tobacco control. 2015;24(5):442–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Steinberg MB, et al. Patterns of electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;18(5):715–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins LK, Villanti AC, Pearson JL, et al. Frequency of Youth E-Cigarette, Tobacco, and Poly-Use in the United States, 2015: Update to Villanti et al., “Frequency of Youth E-Cigarette and Tobacco Use Patterns in the United States: Measurement Precision Is Critical to Inform Public Health”. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2017:ntx073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasza KA, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Tobacco-Product Use by Adults and Youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villanti AC, Pearson JL, Glasser AM, et al. Frequency of Youth E-Cigarette and Tobacco Use Patterns in the United States: Measurement Precision Is Critical to Inform Public Health. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2016;19(11):1345–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maglia M, Caponnetto P, Di Piazza J, La Torre D, Polosa R. Dual use of electronic cigarettes and classic cigarettes: a systematic review. Addiction Research & Theory. 2017:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olmedo P, Goessler W, Tanda S, et al. Metal Concentrations in e-Cigarette Liquid and Aerosol Samples: The Contribution of Metallic Coils. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126(2):027010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine,. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shahab L, Goniewicz ML, Blount BC, et al. Nicotine, carcinogen, and toxin exposure in long-term e-cigarette and nicotine replacement therapy users: a cross-sectional study. Annals of internal medicine. 2017;166(6):390–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goniewicz ML, Gawron M, Smith DM, Peng M, Jacob P, Benowitz NL. Exposure to nicotine and selected toxicants in cigarette smokers who switched to electronic cigarettes: a longitudinal within-subjects observational study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2017;19(2):160–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osei AD, Mirbolouk M, Orimoloye OA, et al. Association Between E-Cigarette Use and Cardiovascular Disease Among Never and Current Combustible-Cigarette Smokers. The American journal of medicine. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King JL, Reboussin BA, Wiseman KD, et al. Adverse symptoms users attribute to e-cigarettes: Results from a national survey of US adults. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2019;196:9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li D, Sundar IK, McIntosh S, et al. Association of smoking and electronic cigarette use with wheezing and related respiratory symptoms in adults: cross-sectional results from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study, wave 2. Tobacco Control. 2019:tobaccocontrol-2018–054694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tobacco Control. 2016:tobaccocontrol-2016–052934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tourangeau R, Yan T, Sun H, Hyland A, Stanton CA. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) reliability and validity study: selected reliability and validity estimates. Tobacco control. 2018:tobaccocontrol-2018–054561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarthy PJ. Pseudoreplication: further evaluation and applications of the balanced half-sample technique. 1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Judkins DR. Fay’s method for variance estimation. Journal of Official Statistics. 1990;6(3):223. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(2):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glasser AM, Collins L, Pearson JL, et al. Overview of electronic nicotine delivery systems: a systematic review. American journal of preventive medicine. 2017;52(2):e33–e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins L, Glasser AM, Abudayyeh H, Pearson JL, Villanti AC. E-Cigarette Marketing and Communication: How E-Cigarette Companies Market E-Cigarettes and the Public Engages with E-cigarette Information. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2018;1:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brandon TH, Goniewicz ML, Hanna NH, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: a policy statement from the American Association for Cancer Research and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Clinical Cancer Research. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagoner KG, Song EY, King JL, et al. Availability and Placement of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems at the Point-of-Sale. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagoner KG, Song EY, Egan KL, et al. E-cigarette availability and promotion among retail outlets near college campuses in two southeastern states. Nicotine & tobacco research. 2014;16(8):1150–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu S-H, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tobacco control. 2014;23(suppl 3):iii3–iii9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coleman B, Rostron B, Johnson SE, et al. Transitions in electronic cigarette use among adults in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, Waves 1 and 2 (2013–2015). Tobacco control. 2018:tobaccocontrol-2017-054174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor KA, Sharma E, Edwards KC, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco cigarette use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma E, Bansal-Travers M, Edwards KC, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco hookah use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s155–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards KC, Sharma E, Halenar MJ, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco cigar use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s163–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma E, Edwards KC, Halenar MJ, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco smokeless use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s170–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen JC, Green KM, Arria AM, Borzekowski DL. Prospective predictors of flavored e-cigarette use: A one-year longitudinal study of young adults in the US. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2018;191:279–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Miller Lo EJ. Changes in the mass-merchandise cigar market since the Tobacco Control Act. Tobacco regulatory science. 2017;3(2):8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gammon DG, Loomis BR, Dench DL, King BA, Fulmer EB, Rogers T. Effect of price changes in little cigars and cigarettes on little cigar sales: USA, Q4 2011–Q4 2013. Tobacco control. 2016;25(5):538–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silveira ML, Hilmi NN, Conway KP. Reasons for Young Adult Waterpipe Use in Wave 1 (2013–2014) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duke JC, Lee YO, Kim AE, et al. Exposure to electronic cigarette television advertisements among youth and young adults. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):e29–e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giovenco DP, Casseus M, Duncan DT, Coups EJ, Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD. Association between electronic cigarette marketing near schools and e-cigarette use among youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;59(6):627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wackowski OA, Delnevo CD. Young adults’ risk perceptions of various tobacco products relative to cigarettes: results from the National Young Adult Health Survey. Health Education & Behavior. 2016;43(3):328–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willett JG, Bennett M, Hair EC, et al. Recognition, use and perceptions of JUUL among youth and young adults. Tobacco control. 2019;28(1):115–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Patrick ME. Adolescent vaping and nicotine use in 2017–2018—US national estimates. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380(2):192–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vallone DM, Bennett M, Xiao H, Pitzer L, Hair EC. Prevalence and correlates of JUUL use among a national sample of youth and young adults. Tobacco control. 2018:tobaccocontrol-2018–054693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hammond D, Wackowski OA, Reid JL, O’Connor RJ. Use of JUUL e-cigarettes among youth in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kasza K, Edwards KC, Tang Z, et al. Correlates of tobacco product initiation among youth and adults in the United States: findings from the path study waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kasza K, Edwards KC, Tang Z, et al. Correlates of tobacco product cessation among youth and adults in the United States: findings from the path study waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s203–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edwards KC, Kasza K, Tang Z, et al. Correlates of tobacco product relapse among youth and adults in the United States: findings from the path study waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s216–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.