Abstract

Background

Cancer patients who undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are among the most medically fragile patient populations with extreme demands for caregivers. Indeed, with earlier hospital discharges, the demands placed on caregivers continue to intensify. Moreover, an increased number of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantations are being performed worldwide, and this expensive procedure has significant economic consequences. Thus, the health and well-being of family caregivers have attracted widespread attention. Mobile health technology has been shown to deliver flexible, and time- and cost-sparing interventions to support family caregivers across the care trajectory.

Objective

This protocol aims to leverage technology to deliver a novel caregiver-facing mobile health intervention named Roadmap 2.0. We will evaluate the effectiveness of Roadmap 2.0 in family caregivers of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Methods

The Roadmap 2.0 intervention will consist of a mobile randomized trial comparing a positive psychology intervention arm with a control arm in family caregiver-patient dyads. The primary outcome will be caregiver health-related quality of life, as assessed by the PROMIS Global Health scale at day 120 post-transplant. Secondary outcomes will include other PROMIS caregiver- and patient-reported outcomes, including companionship, self-efficacy for managing symptoms, self-efficacy for managing daily activities, positive affect and well-being, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety. Semistructured qualitative interviews will be conducted among participants at the completion of the study. We will also measure objective physiological markers (eg, sleep, activity, heart rate) through wearable wrist sensors and health care utilization data through electronic health records.

Results

We plan to enroll 166 family caregiver-patient dyads for the full data analysis. The study has received Institutional Review Board approval as well as Code Review and Information Assurance approval from our health information technology services. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, the study has been briefly put on hold. However, recruitment began in August 2020. We have converted all recruitment, enrollment, and onboarding processes to be conducted remotely through video telehealth. Consent will be obtained electronically through the Roadmap 2.0 app.

Conclusions

This mobile randomized trial will determine if positive psychology-based activities delivered through mobile health technology can improve caregiver health-related quality of life over a 16-week study period. This study will provide additional data on the effects of wearable wrist sensors on caregiver and patient self-report outcomes.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04094844; https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04094844

International Registered Report Identifier (IRRID)

PRR1-10.2196/19288

Keywords: family caregivers, mobile health app, mHealth, randomized controlled trial, wearable wrist sensor, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, HSCT

Introduction

Approximately 2.8 million people in the United States are currently providing unpaid, informal care to an adult with cancer [1,2]. With the growing number of cancer survivors, family caregivers represent a critical extension of the national health care system [3]. Caregiving tasks are time- and labor-intensive, and include multifaceted activities [4]. Unfortunately, these experiences may lead to significant physical, psychological, emotional, social, and financial burdens, along with deleterious health effects [5-7]. There is broad agreement that caregiving is challenging and stressful. This is perhaps most pronounced in caregivers of patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), also commonly known as blood and marrow transplantation, who must address the intense and persistent caregiving needs of some of the most critically ill cancer patients, which continue throughout a prolonged hospital stay, followed by close outpatient follow up over many months [8,9].

Given the high risks associated with HSCT, a dedicated caregiver is necessary and expected for at least the first 100 days post-transplant [10]. However, HSCT caregivers are often unprepared for this role; thus, it is not surprising that HSCT caregivers experience significant levels of anxiety and distress, especially during the peritransplant period [8,9]. Psychoeducation, skills training, and therapeutic counseling interventions have been shown to benefit caregiver health and well-being [11]. However, there remain major barriers in translating successful interventions to clinical practice, including limited understanding of the mechanism of action of an intervention, and need for expert trainers, intensive training, and monitoring [12]. Thus, interventions that are mechanism-focused, low-cost, and sustainable are needed [13].

The ability to capture the hazards of caregiving (ie, adverse physical and mental health consequences) [14] accurately and in real time has been limited by assessments that have traditionally relied on long-term recall and self-report of symptoms. Mobile health (mHealth) technology remains relatively new in the clinical research area, but is spreading quickly and its costs are declining [15], which may facilitate stronger partnerships between patients, family caregivers, and health care providers [16]. In particular, mHealth technology can serve as a platform for the delivery of multicomponent health interventions while capturing continuous, real-time measures via wearable sensors (eg, sleep, physical activity). The extreme HSCT setting [17] provides an ideal “model” to rigorously test an mHealth intervention owing to (1) the high level of engagement by HSCT caregivers; (2) intense and rapidly evolving caregiving needs of medically fragile patients; and (3) long hospital course followed by frequent outpatient follow up that allow for high-resolution data collection with minimal additional burden [18].

In HSCT, malignant cells are first destroyed by chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, followed by infusion of compatible donor cells to alleviate profound hematologic toxicities (eg, neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia) [19]. The main complications, some of which are life-threatening, include mucositis, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, infections, and bleeding. Therefore, a dedicated 24/7 caregiver is necessary and expected. Frequently, a caregiver is tasked with monitoring treatment side effects, managing the symptom burden, making treatment decisions, administering medications, and performing medical tasks (eg, central line care and dressing changes). After engraftment of donor cells, graft-versus-host disease may ensue, which may further result in prolonged immunosuppression, morbidity, and mortality [20-22]. As such, the HSCT trajectory may be long and unpredictable [23], which creates a complex and multifaceted caregiving process. Caregivers can easily become overwhelmed and must juggle multiple roles: (i) “interpreter” of medical information; (ii) “organizer” of medical appointments and juggling the needs of other family members; and (iii) “clinician” to assess and identify health changes in the patient [23].

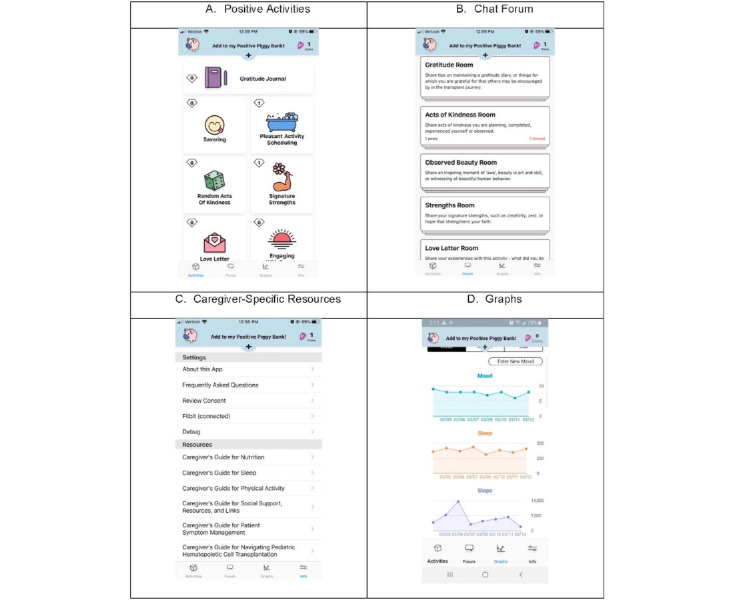

Our research team previously developed Roadmap 1.0 (formerly referred to as BMT Roadmap) as a caregiver-facing mHealth app. Details of the app with descriptions of each of the components have been published previously [24-26]. We iteratively designed and developed the Roadmap 2.0 mHealth app following the following 7 research phases: (1) Roadmap 1.0 prototype [27,28]; (2) design groups to evaluate the Roadmap 1.0 prototype [29]; (3) pilot study of Roadmap 1.0 [30-32]; (4) extensive literature review [33,34]; (5) design and development of Roadmap 2.0 in the outpatient setting [25]; (6) design and development of Roadmap 2.0 in the participant home setting [24]; and (7) deployment of a National Caregiver Health survey [25]. Figure 1 shows screenshots of key app features, and Multimedia Appendix 1 provides a detailed definition of the multicomponent features of the Roadmap 2.0 app.

Figure 1.

Screenshots of the Roadmap 2.0 app.

Our preliminary data showed that family caregivers were interested in and willing to engage in positive psychology interventions to reduce stress and improve their health-related quality of life [18,19]. Herein, we provide a detailed description of the design for a mobile randomized controlled trial to test this investigator-initiated, multicomponent Roadmap 2.0 app comparing a positive psychology-based intervention arm with a control arm in HSCT family caregiver-patient dyads (the Roadmap 2.0 trial). We postulated that simple and intentional pleasant activities that could be developed into routine practices, such as expressing gratitude or scheduling activities that promote positive thoughts, emotions, or behaviors [35-37], may be effective and scalable in the HSCT caregiver population.

Methods

Study Design

Overview

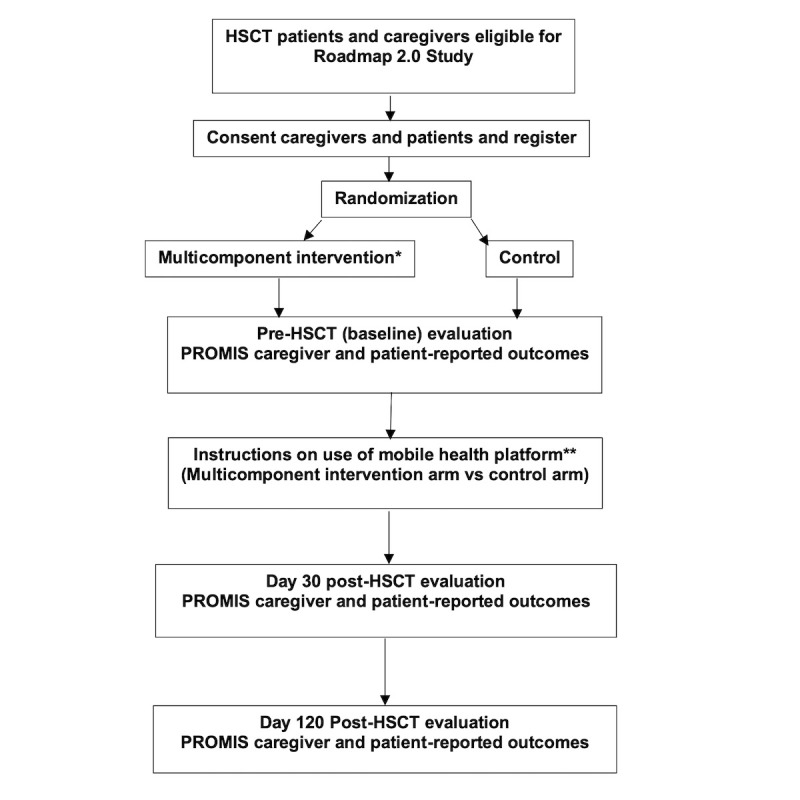

This study will test the effectiveness of a positive psychology intervention delivered via an mHealth technology platform (see Figure 2 for a schema of the study design). The trial is planned according to a two-arm randomized controlled design. Each of the caregiver-patient participants will be randomized to an active treatment arm (Roadmap 2.0 app + multicomponent features + Fitbit Charge 3) or to a control arm (Roadmap 2.0 app + Fitbit Charge 3; that is, the app displays physiological data only without any multicomponent features). The random allocation of participants to the treatment arm or control arm establishes the basis for testing the statistical significance or difference between the groups in the primary measured outcome (caregiver health-related quality of life, assessed by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System [PROMIS] Global Health scale [38]). Caregiver-patient age, gender, and other prognostic baseline characteristics that could potentially confound an observed association, including those that are unknown or unmeasured, will be distributed equally, except through chance alone, through random assignment. Thus, this design is well-suited to our goal of assessing the effectiveness of an mHealth intervention, Roadmap 2.0, on caregivers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Study schema. HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Primary Objective

The primary objective of this proposal is to test Roadmap 2.0 + multicomponent features in caregivers of patients undergoing HSCT. One half of the caregivers will be randomly assigned to the treatment arm and the other half will be assigned to the control arm.

Primary Endpoint

A single primary endpoint of caregiver health-related quality of life (as assessed by the PROMIS Global Health-10 scale [38]) at day 120 post-transplant is designated for the purpose of planning the sample size (see below) and duration of the study, and to avoid problems of interpreting tests of multiple hypotheses (for caregivers and patients).

Secondary Endpoints

Constructs of both caregiver and patient health-related quality of life include (1) positive aspects of caregiving, assessed by the PROMIS Companionship [39], PROMIS Self-Efficacy for Managing Symptoms [40], PROMIS Self-Efficacy for Managing Daily Activities [41], and Neuro-QoL Positive Affect and Well-Being scales [42]; (2) negative aspects of caregiving, assessed by the PROMIS Sleep Disturbance [43], PROMIS Depression [44], and PROMIS Anxiety scales [39]; and (3) other caregiver-specific well-being or health-related quality of life measures assessed by the TBI-CareQoL Caregiver Anxiety [45,46] and TBI-CareQol Caregiver Strain [45,47] scales (see Multimedia Appendix 2). Additional secondary endpoints will include both caregiver and patient health care utilization (eg, total count of hospital days, readmissions, and ambulatory care clinic visits within the first 120 days post-transplant) and patient infections, graft-versus-host disease, relapse, and survival.

Blinding

Study arm assignments cannot be blinded to the investigators because it will be known whether participants have Roadmap 2.0 on their mobile device or not (for technical purposes).

Intervention Period

The intervention will be delivered from the time of admission for the patient’s HSCT through day 120 post-transplant. Data will be collected preintervention (baseline), during the intervention (day 30 post-transplant), and at the end of the intervention (day 120 post-transplant). The length of the intervention is therefore approximately 16 weeks.

Participant Enrollment and Evaluation

Participants (caregiver-patient dyads) will be approached for inclusion in the study after the decision to proceed with transplantation is made by the patient. Caregivers will be identified by the patient as their primary caregiver who will be providing at least 50% of the caregiving needs. Multiple caregivers are not allowed according to the study design. Participants willing to participate in this trial will sign an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved consent form. Transplant physicians will evaluate the patient eligibility to undergo HSCT as well as eligibility for randomization in this study. Eligibility criteria will be verified by the study team and the clinical trials support office. Ineligible participants will proceed off study and no further follow up will be obtained. The study team personnel (eg, research coordinator) will record the documentation of subject consent in the OnCore Clinical Trials Management System (a web-based system that supports all aspects of clinical research, including protocol management, patient registry, biospecimen repository, and budget tracking) and will be registered through the clinical trials support office.

The inclusion criteria for the caregiver are that they must have an eligible patient (see definition below) for whom they provide at least 50% of care needs, be at least 18 years old, able to read and speak English, and capable of signing an informed consent form. An eligible patient is one who: identifies the eligible caregiver as their primary caregiver (ie, provides at least 50% of their care needs), aged ≥18 years, scheduled to undergo HSCT, and able to read and speak English and to sign informed consent forms.

Patients and caregivers will agree to provide regulatory compliance and IRB-approved informed consent, in accordance with the Clinical Practice Guidelines of the University of Michigan Transplant Program. A patient is considered to be able to undergo HSCT at the University of Michigan only if a designated family caregiver (eg, parent, adult children, spouse, family member, neighbor, friend) accepts the roles outlined in the University of Michigan Caregiver Responsibility Contract, and both the caregiver and patient sign the contract. The exclusion criterion is therefore a patient who does not meet these eligibility criteria to undergo HSCT at the University of Michigan Transplant Program.

Transplant Protocol Registration

Before randomization, the research coordinator must state the baseline caregiver biological characteristics (eg, age, gender, race/ethnicity) through the OnCore Clinical Trials Management System. This will avoid potential biases such as preferential use of gender in one arm of the study. At this stage, the research coordinator will also verify that the patient is still a candidate for transplantation, and that both the caregiver and patient are eligible for the trial.

Randomization

Blocked randomization will be used to limit bias and achieve an equal distribution of participants to the control and treatment arms. Randomization will be overseen by the study statistician (TB).

Once the caregiver is deemed eligible and has provided written informed consent, the research coordinator will confirm their eligibility. The study statistician (TB) will create a randomization list before enrollment using the R statistical software package. The statistician will then forward the list to the clinical trials support office, who will be responsible for enrolling patients and assigning them to the correct study arm. Caregivers will not be randomized more than 21 days from the planned initiation of conditioning. All patient treatments related to the transplant will be scheduled prior to randomization. This includes planning an admission date and ensuring that donors can be used in a coordinated fashion with the planned transplant.

Participants (caregiver-patient dyad) randomized to the treatment arm (Roadmap 2.0 app + multicomponents features + Fitbit Charge 3) will be instructed on how to operate the Roadmap 2.0 app on their own mobile device and to create a password, and to use it freely throughout the intervention period. The caregiver and patient will receive their own respective passwords. Timestamps will be recorded of each participant’s use of Roadmap 2.0 (ie, number of logins and pages viewed, when and how long and in what order). Caregivers and patients will both be provided with Fitbit Charge 3 wearable wrist sensors.

Participants randomized to the control arm (Roadmap 2.0 app without any multicomponent features + Fitbit Charge 3) will be advised to use their own mobile device freely throughout the intervention period. Participants will receive usual care, defined as standard-of-care information provided according to the Clinical Practice Guidelines of the University of Michigan Transplant Program. This version of Roadmap 2.0 has no positive psychology-based activities, but caregivers and patients will both be provided with Fitbit Charge 3 wearable wrist sensors. Their view of the app will only include the “Settings” section but not the “Resources” section (Figure 1).

Confidentiality

Confidentiality will be maintained by individual names being masked and each participant being assigned a patient identifier code. The code relaying the participant’s identity with the ID code will be kept separately at the Clinical Trials Support Office. The outcome measures will be deidentified and masked to the biostatistician/data scientist performing the analyses.

Pretransplant Evaluations

Based on prior work, our study team has experience in obtaining caregiver demographics. The following data will be collected (ie, caregiver self-report) via the Roadmap 2.0 app within 30 days of randomization: demographic, caregiving, and personal health variables such as marital status, alcohol/tobacco use, education, employment, annual household income, use of technology, type of relationship to the patient, number of household members, health insurance status, number of years and number of hours per week (of caregiving), health comorbidities, medications, and caffeine intake.

The following data will be collected within 30 days of randomization, according to the Transplant Program Clinical Practice Guidelines in patients undergoing transplant: history, physical examination, height, weight, Karnofsky performance status [48], HSCT-specific Comorbidity Index Score [49], routine laboratory parameters (eg, complete blood count with differential and platelet count, serum creatinine bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, aspartate transaminase, and alanine aminotransferase), infectious disease titers, electrocardiogram and left ventricle ejection fraction, pulmonary function tests, disease evaluation of underlying blood disease, chest X-ray or chest computed tomography, pregnancy test, pretransplant donor and recipient samples for post-transplant chimerism evaluation, and pretransplant blood samples for future research.

PROMIS caregiver and patient health-related quality of life assessments will be obtained at baseline, preintervention (Multimedia Appendix 2).

Intervention

Overall Design

Participants (caregiver-patient dyad) who are consented, enrolled, and randomized in the study will be scheduled for a 1-hour virtual video training session with the research coordinator prior to admission to undergo the transplant. Based on our experience, these training sessions will be coordinated with other clinic appointments at the hospital in efforts to minimize the burden on the caregiver and patient. Once the intervention has begun, the research coordinator will meet with the participants (caregiver-patient dyad) weekly (virtually) to review any questions or concerns and to ensure adherence to the protocol. HSCT patients are typically inpatients for approximately 4 weeks. During this period, the research coordinator will be available by pager and will schedule weekly visits (virtual or in person if needed) with the participants. Once discharged, HSCT patients return to the clinic on a weekly visit in the ambulatory care setting. The research coordinator will meet with participants during these routine appointments or virtually if possible.

Fidelity

Based on our prior work, it is critical that adherence and fidelity of the protocol are maintained. Thus, our research staff will develop Intervention Fidelity Guidelines (Multimedia Appendix 3) for the study team to follow and monitor participants, which will help to increase confidence that “study outcomes are due to the intervention being investigated and not due to variability in intervention implementation” [50]. Moreover, the Intervention Fidelity Guidelines will assist in future implementation and dissemination efforts. A rigorous Recruitment and Retention Plan has also been developed and will be adhered to according to good clinical practice (Multimedia Appendix 4).

Power Calculation

The power calculation was completed using simulations in the statistical package R. We will enroll 166 caregivers and their care recipients (332 total individuals). Our primary endpoint (ie, caregiver health-related quality of life from the PROMIS Global Health scale) is focused solely on this outcome in caregivers, whereas our secondary endpoints are based on outcomes for both caregivers and patients. Accordingly, we determined the sample size based solely on caregivers. The age- and sex-adjusted norm for the Global Health scale is 50 points, with a standard deviation of 10 points; these statistics have been shown to be generalizable to the HSCT population. With 67 caregivers enrolled in each arm, our study will have power of 0.80, assuming a two-sided type I error rate of 0.05, to detect an effect size of 0.5 between the intervention and control arms. A mean difference of one-half a standard deviation is biologically meaningful and is considered a medium effect size for clinical trials. We will accrue a total of 83 caregivers in each arm to account for dropout, assuming a 5% failure to undergo HSCT, 8% death before day 120, and 10% missing day 120 patient-reported outcomes from participants.

Data Analysis

PROMIS measures are based on the item response theory [51], a family of statistical models that link individual questions to a presumed underlying trait or concept of global health represented by all items in the scale. PROMIS instruments are scored using item-level calibrations. The most accurate way to score a PROMIS instrument is to use the HealthMeasures Scoring Service, which our study team has prior experience with. This method of scoring uses “response pattern scoring,” which scores the responses to each item for each participant. Response pattern scoring is especially useful when there are missing data (ie, a respondent skipped an item, or different groups of participants responded to different items).

Visit Schedule (Occurring and Planned Visits)

The study intervention period includes the time of admission to the transplant unit through day 120 post-transplant. The average length of hospitalization is 4 weeks. The research coordinator will meet with study participants once weekly during the inpatient hospitalization period. Following discharge, the research coordinator will continue meeting with study participants during routine, standard-of-care weekly visits through day 120 post-transplant (study endpoint). Baseline, day 30, and day 120 post-transplant survey instruments will be completed by study participants.

Data and Safety Monitoring

This study will be monitored in accordance with the University of Michigan Data and Safety Monitoring Plan for HSCT-specific study protocols. The study team will meet every 6 months or more frequently depending on the activity of the protocol. The discussion will include matters related to the safety of study participants (adverse event and severe adverse event reporting), validity and integrity of the data, enrollment rate relative to expectations, characteristics of participants, retention of participants, adherence to the protocol (potential or real protocol deviations), and data completeness. At these regular meetings, the protocol-specific Data and Safety Monitoring Report form will be completed and signed by the principal investigator or by one of the coinvestigators. Data and Safety Monitoring Reports will be submitted to the University of Michigan Data and Safety Monitoring Committee and the IRB every 6 months for independent review.

Results

The study protocol complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. This protocol has been approved by the IRB at the University of Michigan and has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04094844).

Due to the current COVID-19 pandemic [52,53], the study has been briefly put on hold. However, recruitment began in August 2020. We have converted all recruitment, enrollment, and onboarding processes to be conducted remotely through video telehealth. Consent will be obtained electronically through the Roadmap 2.0 app.

Discussion

Caregiver burden is defined as a “negative reaction to the impact of providing care on the caregiver’s social, occupational, and personal roles” [54]. To date, substantial focus has been placed on the wide range of negative implications associated with caregiving [55] (eg, depression, anxiety) [56]. Nevertheless, a majority of caregivers have recognized the benefits of caregiving [57,58]. The imbalance of focusing primarily on negative aspects may limit our ability to develop new assessment and intervention methods [59]. Thus, a “corrective focus” is needed in caregiving research to expand knowledge on the positive aspects of caregiving [60,61]. Research on self-management suggests that self-efficacy, a positive aspect, can promote caregiver health, well-being, and positive health behaviors (ie, improved sleep and physical activity) [62,63].

The positive aspects of caregiving, such as self-efficacy and positive attitudes toward the caregiver role, may explain how caregivers can positively engage patients in self-care activities [64]. Caregivers with better self-efficacy and well-being (eg, health-related quality of life) may positively impact patients’ health outcomes [65-67]. Simple strategies aimed at enhancing positive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors have been shown to be effective and highly scalable [35-37]. Positive activity interventions such as daily positive reflection, gratitude journals, and conducting acts of kindness have been used in the context of heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and chronic pain [68-73]. Our preliminary data suggest that HSCT caregivers desire these activities to reduce stress and improve well-being.

Caregivers experience significant stress, anxiety, and poor sleep that lead to physiological changes [74]. Indeed, long-term caregiving has been associated with increased physical morbidity [75]. Although caregiver interventions have been shown to reduce emotional distress and increase well-being [76], less is known about the impact of physiological changes on caregiver health and well-being [14]. Previous caregiver assessments have relied on snapshot self-report measures (ie, patient-reported outcomes) [77]. Recent advances in wearable sensors facilitate the noninvasive collection of continuous, real-time measures (eg, sleep, physical activity). These highly time-resolved, objective parameters correlated with subjective patient-reported outcomes may help us to further identify the mechanism of action of an intervention. Further, newer data science techniques may enable data patterns, relationships, and interpretation in ways that were not previously possible [78].

Emerging literature on family caregivers suggests a wide range of health information technology studies that are being conducted [79-82], which have been embraced by both caregivers and patients [16]. We have described the design and research protocol of an mHealth app for HSCT caregivers and patients, which will be tested in a Roadmap 2.0 mobile randomized trial. We outlined the multicomponent features of the mHealth app, study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, how the intervention will work, recruitment and retention, intervention fidelity guidelines, and data safety monitoring plans. Our multicomponent intervention is innovative, and our mHealth app could have significant impact and wide-ranging clinical applications. Alternatively, even if the primary endpoint of the intervention is not met, we will be able to use the caregiver and patient experiences and secondary outcome findings to create new hypotheses and explore alternative strategies. We are excited about the large multiparameter dataset that will be collected from diverse sources, including caregiver- and patient-reported outcomes, interviews, and physiological markers. Thus, the data streams of Roadmap 2.0 have the potential to provide new understanding about what component of the intervention is driving a desired or undesired outcome. Furthermore, this study has potential to generate new insights into the relationship between caregiver burden, well-being, and health without the dependence on expert trainers, intensive training, or monitoring given its remote features. Ultimately, we anticipate that this study will inform more personalized interventions for caregivers and patients in the future, and address gaps in previous interventions that required face-to-face interactions.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by an American Society of Hematology Bridge Grant and NIH/NHBLI grant (1R01HL146354) and the Edith S. Briskin and Shirley K Schlafer Foundation (Sung Won Choi).

Abbreviations

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- IRB

institutional review board

- mHealth

mobile health

- PROMIS

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

Appendix

Definitions of multicomponent features of Roadmap 2.0.

Caregiver- and patient-reported outcome measures.

Intervention Fidelity Guidelines.

Recruitment and Retention Plan.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: MR and MD were responsible for writing the original draft, data curation, and visualization; AM and MT reviewed and edited the manuscript; AH, DB, NC, and DH were involved in protocol development, study design, and writing-review/editing; TB contributed to protocol development, study design, and the power calculation; SC is in charge of data curation, investigation, methodology, data analysis, resources, supervision, visualization, and manuscript writing and review.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Caregiving in the US 2015. The National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) and the AARP Public Policy Institute. [2020-08-13]. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/caregiving-in-the-united-states-2015-report-revised.pdf.

- 2.Cancer Caregiving in the U.S. An Intense, Episodic, and Challenging Care Experience. National Alliance for Caregiving in partnership with the National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Support Community. 2016. Jun, [2020-08-13]. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CancerCaregivingReport_FINAL_June-17-2016.pdf.

- 3.Caregiver Statistics: Demographics. Family Caregiver Alliance, National Center on Caregiving. [2020-08-13]. https://www.caregiver.org/caregiver-statistics-demographics.

- 4.Bevans M, Sternberg EM. Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. JAMA. 2012 Jan 25;307(4):398–403. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.29. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22274687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one's physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003 Nov;129(6):946–972. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S, Colditz GA, Berkman LF, Kawachi I. Caregiving and risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. women: a prospective study. Am J Prev Med. 2003 Feb;24(2):113–119. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz R, Newsom J, Mittelmark M, Burton L, Hirsch C, Jackson S. Health effects of caregiving: the caregiver health effects study: an ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19(2):110–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02883327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bevans MF, Mitchell SA, Marden S. The symptom experience in the first 100 days following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) Support Care Cancer. 2008 Nov 6;16(11):1243–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0420-6. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18322708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simoneau TL, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Natvig C, Kilbourn K, Spradley J, Grzywa-Cobb R, Philips S, McSweeney P, Laudenslager ML. Elevated peri-transplant distress in caregivers of allogeneic blood or marrow transplant patients. Psychooncology. 2013 Sep 25;22(9):2064–2070. doi: 10.1002/pon.3259. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23440998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laudenslager ML, Simoneau TL, Kilbourn K, Natvig C, Philips S, Spradley J, Benitez P, McSweeney P, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK. A randomized control trial of a psychosocial intervention for caregivers of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients: effects on distress. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015 Aug 11;50(8):1110–1118. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.104. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25961767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gemmill R, Cooke L, Williams AC, Grant M. Informal Caregivers of Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Patients. Cancer Nursing. 2011;34(6):E13–E21. doi: 10.1097/ncc.0b013e31820a592d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinhard SC, Given B, Petlock NH, Bemis A. Supporting family caregivers in providing care. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. Apr 01, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Committee on Family Caregiving for Older Adults. Board on Health Care Services. Health and Medicine Division. National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine . In: Families Caring for an Aging America. Schulz R, Eden J, editors. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuster PA, Merkle CJ. Caregiving stress, immune function, and health: implications for research with parents of medically fragile children. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2004 Jul 10;27(4):257–276. doi: 10.1080/01460860490884165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demographics of Mobile Device Ownership and Adoption in the United States. Pew Research Center. 2017. [2020-08-13]. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/

- 16.Wolff JL, Darer JD, Larsen KL. Family Caregivers and Consumer Health Information Technology. J Gen Intern Med. 2016 Jan 27;31(1):117–121. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3494-0. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26311198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Applebaum AJ, Bevans M, Son T, Evans K, Hernandez M, Giralt S, DuHamel K. A scoping review of caregiver burden during allogeneic HSCT: lessons learned and future directions. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016 Nov 13;51(11):1416–1422. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.164. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27295270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buyuktur AG. Temporality and Information Work in Bone Marrow Transplant, PhD Dissertation. University of Michigan. 2015. [2020-08-13]. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/111491/abuyuktu_1.pdf;sequence=1.

- 19.Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006 Apr 27;354(17):1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paczesny S, Choi SW, Ferrara JL. Acute graft-versus-host disease: new treatment strategies. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009 Nov;16(6):427–436. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283319a6f. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19812490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi SW, Levine JE, Ferrara JL. Pathogenesis and management of graft-versus-host disease. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010 Feb;30(1):75–101. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2009.10.001. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20113888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi SW, Reddy P. Current and emerging strategies for the prevention of graft-versus-host disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014 Sep 24;11(9):536–547. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.102. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24958183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Von Ah D, Spath M, Nielsen A, Fife B. The Caregiver's Role Across the Bone Marrow Transplantation Trajectory. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(1):E12–E19. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaar D, Shin JY, Mazzoli A, Vue R, Kedroske J, Chappell G, Hanauer DA, Barton D, Hassett AL, Choi SW. A Mobile Health App (Roadmap 2.0) for Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant: Qualitative Study on Family Caregivers' Perspectives and Design Considerations. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019 Oct 24;7(10):e15775. doi: 10.2196/15775. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2019/10/e15775/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kedroske J, Koblick S, Chaar D, Mazzoli A, O'Brien M, Yahng L, Vue R, Chappell G, Shin JY, Hanauer DA, Choi SW. Development of a National Caregiver Health Survey for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant: Qualitative Study of Cognitive Interviews and Verbal Probing. JMIR Form Res. 2020 Jan 23;4(1):e17077. doi: 10.2196/17077. https://formative.jmir.org/2020/1/e17077/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maher M, Hanauer DA, Kaziunas E, Ackerman MS, Derry H, Forringer R, Miller K, O'Reilly D, An L, Tewari M, Choi SW. A Novel Health Information Technology Communication System to Increase Caregiver Activation in the Context of Hospital-Based Pediatric Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Pilot Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015 Oct 27;4(4):e119. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4918. https://www.researchprotocols.org/2015/4/e119/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaziunas E, Buyuktur A, Jones J, Choi S, Hanauer D. Transition and Reflection in the Use of Health Information: The Case of Pediatric Bone Marrow Transplant Caregivers. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW); 2015; Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaziunas E, Hanauer DA, Ackerman MS, Choi SW. Identifying unmet informational needs in the inpatient setting to increase patient and caregiver engagement in the context of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016 Jan 28;23(1):94–104. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv116. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26510878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maher M, Kaziunas E, Ackerman M, Derry H, Forringer R, Miller K, O'Reilly D, An LC, Tewari M, Hanauer DA, Choi SW. User-Centered Design Groups to Engage Patients and Caregivers with a Personalized Health Information Technology Tool. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 Feb;22(2):349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.08.032. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1083-8791(15)00593-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Runaas L, Hanauer D, Maher M, Bischoff E, Fauer A, Hoang T, Munaco A, Sankaran R, Gupta R, Seyedsalehi S, Cohn A, An L, Tewari M, Choi SW. BMT Roadmap: A User-Centered Design Health Information Technology Tool to Promote Patient-Centered Care in Pediatric Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017 May;23(5):813–819. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.01.080. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1083-8791(17)30227-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Runaas L, Hoodin F, Munaco A, Fauer A, Sankaran R, Churay T, Mohammed S, Seyedsalehi S, Chappell G, Carlozzi N, Fetters MD, Kentor R, McDiarmid L, Brookshire K, Warfield C, Byrd M, Kaziunas S, Maher M, Magenau J, An L, Cohn A, Hanauer DA, Choi SW. Novel Health Information Technology Tool Use by Adult Patients Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: Longitudinal Quantitative and Qualitative Patient-Reported Outcomes. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2018 Dec;2:1–12. doi: 10.1200/CCI.17.00110. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/CCI.17.00110?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fauer AJ, Hoodin F, Lalonde L, Errickson J, Runaas L, Churay T, Seyedsalehi S, Warfield C, Chappell G, Brookshire K, Chaar D, Shin JY, Byrd M, Magenau J, Hanauer DA, Choi SW. Impact of a health information technology tool addressing information needs of caregivers of adult and pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients. Support Care Cancer. 2019 Jun 20;27(6):2103–2112. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4450-4. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30232587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin JY, Kang TI, Noll RB, Choi SW. Supporting Caregivers of Patients With Cancer: A Summary of Technology-Mediated Interventions and Future Directions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018 May 23;38:838–849. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_201397. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/EDBK_201397?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin JY, Choi SW. Online interventions geared toward increasing resilience and reducing distress in family caregivers. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2020 Mar;14(1):60–66. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000481. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31842019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2009 May;65(5):467–487. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health. 2013 Feb 08;13(1):119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-119. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hassett AL, Finan PH. The Role of Resilience in the Clinical Management of Chronic Pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016 Jun 26;20(6):39. doi: 10.1007/s11916-016-0567-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009 Sep 19;18(7):873–880. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19543809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) Scoring PROMIS Companionship Short Form v2.0. U.S. Department of Human and Health Services. 2014. Oct, [2020-08-13]. http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/promis/manuals/PROMIS_Companionship_Scoring_Manual.pdf.

- 40.Hong I, Velozo CA, Li C, Romero S, Gruber-Baldini AL, Shulman LM. Assessment of the psychometrics of a PROMIS item bank: self-efficacy for managing daily activities. Qual Life Res. 2016 Sep 5;25(9):2221–2232. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1270-1. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27048495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Self-Efficacy for Managing Symptoms. PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) [2020-08-13]. http://www.healthmeasures.net/administrator/components/com_instruments/uploads/PROMIS%20Bank%20v1.0%20-%20Self-Effic-ManagSymptoms_8-5-16.pdf.

- 42.Salsman JM, Victorson D, Choi SW, Peterman AH, Heinemann AW, Nowinski C, Cella D. Development and validation of the positive affect and well-being scale for the neurology quality of life (Neuro-QOL) measurement system. Qual Life Res. 2013 Nov 23;22(9):2569–2580. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0382-0. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23526093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jensen RE, King-Kallimanis BL, Sexton E, Reeve BB, Moinpour CM, Potosky AL, Lobo T. Teresi JA: Measurement properties of PROMIS Sleep Disturbance short forms in a large, ethnically diverse cancer cohort. Psychol Test Assess Model. 2016;58(2):353–370. https://www.psychologie-aktuell.com/fileadmin/download/ptam/2-2016_20160627/06_Jensen.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schalet BD, Pilkonis PA, Yu L, Dodds N, Johnston KL, Yount S, Riley W, Cella D. Clinical validity of PROMIS Depression, Anxiety, and Anger across diverse clinical samples. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 May;73:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.036. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26931289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlozzi NE, Kallen MA, Hanks R, Hahn EA, Brickell TA, Lange RT, French LM, Kratz AL, Tulsky DS, Cella D, Miner JA, Ianni PA, Sander AM. The TBI-CareQOL Measurement System: Development and Preliminary Validation of Health-Related Quality of Life Measures for Caregivers of Civilians and Service Members/Veterans With Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019 Apr;100(4S):S1–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.08.175. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30195987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carlozzi NE, Kallen MA, Sander AM, Brickell TA, Lange RT, French LM, Ianni PA, Miner JA, Hanks R. The Development of a New Computer Adaptive Test to Evaluate Anxiety in Caregivers of Individuals With Traumatic Brain Injury: TBI-CareQOL Caregiver-Specific Anxiety. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019 Apr;100(4S):S22–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.027. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29958902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carlozzi NE, Kallen MA, Ianni PA, Hahn EA, French LM, Lange RT, Brickell TA, Hanks R, Sander AM. The Development of a New Computer-Adaptive Test to Evaluate Strain in Caregivers of Individuals With TBI: TBI-CareQOL Caregiver Strain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019 Apr;100(4S):S13–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.033. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29966647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Karnofsky performance status revisited: reliability, validity, and guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 1984 Mar;2(3):187–193. doi: 10.1200/jco.1984.2.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sorror M, Maris M, Storb R, Baron F, Sandmaier B, Maloney D, Storer B. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005 Oct 15;106(8):2912–2919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/15994282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sineath A, Lambert L, Verga C, Wagstaff M, Wingo BC. Monitoring intervention fidelity of a lifestyle behavioral intervention delivered through telehealth. Mhealth. 2017 Aug 25;3:35–35. doi: 10.21037/mhealth.2017.07.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.PROMIS Standards PROMIS Instrument Maturity Model. U.S. Department of Human and Health Services. [2020-08-13]. http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/PROMISStandards_Vers_2_0_MaturityModelOnly_508.pdf.

- 52.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W, China Novel Coronavirus Investigating Research Team A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 20;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31978945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, Spitters C, Ericson K, Wilkerson S, Tural A, Diaz G, Cohn A, Fox L, Patel A, Gerber SI, Kim L, Tong S, Lu X, Lindstrom S, Pallansch MA, Weldon WC, Biggs HM, Uyeki TM, Pillai SK, Washington State 2019-nCoV Case Investigation Team First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 05;382(10):929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32004427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001 Jul 01;51(4):213–231. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.4.213. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0007-9235&date=2001&volume=51&issue=4&spage=213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pinquart M, Sörensen Silvia. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003 Jun;18(2):250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barata A, Wood WA, Choi SW, Jim HSL. Unmet Needs for Psychosocial Care in Hematologic Malignancies and Hematopoietic Cell Transplant. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016 Aug 25;11(4):280–287. doi: 10.1007/s11899-016-0328-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Farran CJ, Keane-Hagerty E, Salloway S, Kupferer S, Wilken CS. Finding meaning: an alternative paradigm for Alzheimer's disease family caregivers. Gerontologist. 1991 Aug 01;31(4):483–489. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanders S. Is the Glass Half Empty or Half Full? Soc Work Health Care. 2005 May 11;40(3):57–73. doi: 10.1300/j010v40n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Northouse L. The Impact of Cancer on the Family: An Overview. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1995 Jan;14(3):215–242. doi: 10.2190/c8y5-4y2w-wv93-qdat. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller B, Lawton MP. Introduction: Finding Balance in Caregiver Research. Gerontologist. 1997 Apr 01;37(2):216–217. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.2.216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mosher CE, Adams RN, Helft PR, O'Neil BH, Shahda S, Rattray NA, Champion VL. Positive changes among patients with advanced colorectal cancer and their family caregivers: a qualitative analysis. Psychol Health. 2017 Jan 24;32(1):94–109. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2016.1247839. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27775432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Au A, Lau K, Sit E, Cheung G, Lai M, Wong SKA, Fok D. The Role of Self-Efficacy in the Alzheimer's Family Caregiver Stress Process: A Partial Mediator between Physical Health and Depressive Symptoms. Clin Gerontol. 2010 Aug 31;33(4):298–315. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2010.502817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Northouse L, Williams A, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Apr 10;30(11):1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Badr H, Yeung C, Lewis MA, Milbury K, Redd WH. An observational study of social control, mood, and self-efficacy in couples during treatment for head and neck cancer. Psychol Health. 2015;30(7):783–802. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.994633. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25471820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D. The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012 Nov;28(4):236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.006. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0749-2081(12)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Porter LS, Sutton LM, McBride CM, Pope MS, McKinstry ET, Furstenberg CP, Dalton J, Baucom DH. The self-efficacy of family caregivers for helping cancer patients manage pain at end-of-life. Pain. 2003 May;103(1-2):157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Garst J, McBride CM, Baucom D. Self-efficacy for managing pain, symptoms, and function in patients with lung cancer and their informal caregivers: associations with symptoms and distress. Pain. 2008 Jul 15;137(2):306–315. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.09.010. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/17942229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huffman JC, Mastromauro CA, Boehm JK, Seabrook R, Fricchione GL, Denninger JW, Lyubomirsky S. Development of a positive psychology intervention for patients with acute cardiovascular disease. Heart Int. 2011 Sep 29;6(2):e14. doi: 10.4081/hi.2011.e14. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23825741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moskowitz JT, Hult JR, Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Maurer S, Bussolari C, Acree M. A positive affect intervention for people experiencing health-related stress: development and non-randomized pilot test. J Health Psychol. 2012 Jul;17(5):676–692. doi: 10.1177/1359105311425275. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22021272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cohn MA, Pietrucha ME, Saslow LR, Hult JR, Moskowitz JT. An online positive affect skills intervention reduces depression in adults with type 2 diabetes. J Posit Psychol. 2014 Jan 01;9(6):523–534. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.920410. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25214877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hausmann LR, Parks A, Youk AO, Kwoh CK. Reduction of bodily pain in response to an online positive activities intervention. J Pain. 2014 May;15(5):560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Müller R, Gertz KJ, Molton IR, Terrill AL, Bombardier CH, Ehde DM, Jensen MP. Effects of a Tailored Positive Psychology Intervention on Well-Being and Pain in Individuals With Chronic Pain and a Physical Disability: A Feasibility Trial. Clin J Pain. 2016 Jan;32(1):32–44. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Casellas-Grau A, Font A, Vives J. Positive psychology interventions in breast cancer. A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014 Jan;23(1):9–19. doi: 10.1002/pon.3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Laudenslager ML, Simoneau TL, Philips S, Benitez P, Natvig C, Cole S. A randomized controlled pilot study of inflammatory gene expression in response to a stress management intervention for stem cell transplant caregivers. J Behav Med. 2016 Apr;39(2):346–354. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9709-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shaffer KM, Kim Y, Carver CS, Cannady RS. Effects of caregiving status and changes in depressive symptoms on development of physical morbidity among long-term cancer caregivers. Health Psychol. 2017 Aug;36(8):770–778. doi: 10.1037/hea0000528. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28639819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Badr H, Carmack CL, Diefenbach MA. Psychosocial interventions for patients and caregivers in the age of new communication technologies: opportunities and challenges in cancer care. J Health Commun. 2015;20(3):328–342. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.965369. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25629218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shilling V, Matthews L, Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Patient-reported outcome measures for cancer caregivers: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2016 Aug;25(8):1859–1876. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1239-0. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26872911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Barua S, Begum S, Ahmed MU. Supervised machine learning algorithms to diagnose stress for vehicle drivers based on physiological sensor signals. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;211:241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zulman DM, Piette JD, Jenchura EC, Asch SM, Rosland A. Facilitating out-of-home caregiving through health information technology: survey of informal caregivers' current practices, interests, and perceived barriers. J Med Internet Res. 2013 Jul 10;15(7):e123. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2472. https://www.jmir.org/2013/7/e123/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kernisan LP, Sudore RL, Knight SJ. Information-seeking at a caregiving website: a qualitative analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2010 Jul 28;12(3):e31. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1548. https://www.jmir.org/2010/3/e31/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marteau TM, Dormandy E. Facilitating informed choice in prenatal testing: how well are we doing? Am J Med Genet. 2001;106(3):185–190. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ploeg J, McAiney C, Duggleby W, Chambers T, Lam A, Peacock S, Fisher K, Forbes DA, Ghosh S, Markle-Reid M, Triscott J, Williams A. A Web-Based Intervention to Help Caregivers of Older Adults With Dementia and Multiple Chronic Conditions: Qualitative Study. JMIR Aging. 2018 Apr 23;1(1):e2. doi: 10.2196/aging.8475. https://aging.jmir.org/2018/1/e2/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Definitions of multicomponent features of Roadmap 2.0.

Caregiver- and patient-reported outcome measures.

Intervention Fidelity Guidelines.

Recruitment and Retention Plan.