Abstract

Background

Clinical endpoint prediction remains challenging for health providers. Although predictors such as age, gender, and disease staging are of considerable predictive value, the accuracy often ranges between 60 and 80%. An accurate prognosis assessment is required for making effective clinical decisions.

Methods

We proposed an extended prognostic model based on clinical covariates with adjustment for additional variables that were radio-graphically induced, termed imaging biomarkers. Eight imaging biomarkers were introduced and investigated in a cohort of 68 non-small cell lung cancer subjects with tumor internal characteristic. The subjects comprised of 40 males and 28 females with mean age at 68.7 years. The imaging biomarkers used to quantify the solid component and non-solid component of a tumor. The extended model comprises of additional frameworks that correlate these markers to the survival ends through uni- and multi-variable analysis to determine the most informative predictors, before combining them with existing clinical predictors. Performance was compared between traditional and extended approaches using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves, Area under the ROC curves (AUC), Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves, Cox Proportional Hazard, and log-rank tests (p-value).

Results

The proposed hybrid model exhibited an impressive boosting pattern over the traditional approach of prognostic modelling in the survival prediction (AUC ranging from 77 to 97%). Four developed imaging markers were found to be significant in distinguishing between subjects having more and less dense components: (P = 0.002–0.006). The correlation to survival analysis revealed that patients with denser composition of tumor (solid dominant) lived 1.6–2.2 years longer (mean survival) and 0.5–2.0 years longer (median survival), than those with less dense composition (non-solid dominant).

Conclusion

The present study provides crucial evidence that there is an added value for incorporating additional image-based predictors while predicting clinical endpoints. Though the hypotheses were confirmed in a customized case study, we believe the proposed model is easily adapted to various clinical cases, such as predictions of complications, treatment response, and disease evolution.

Keywords: Predictive models, Clinical decision- making, Biomarker, Imaging, Endpoint

Background

The prediction of clinical endpoints or outcome measures has always been the focus of personalized medicine, as well as the key learning applications of ill-health related studies, in an effort to provide clinicians with simple and reproducible risk assessment models. It plays important roles in the clinical decision support system, as it is closely related to the interventions or therapeutic selection, care-planning, and resource allocation [1, 2]. An outcome measure as defined in clinical practice is any characteristic or quality measured as the result of health interventions to assess the impact on a patient’s health status [3], such as the survival period, recurrence or relapse of a cancer, or adverse events. Previous attempts to predict a patient outcome mostly centered to a mortality risk stratification (probability of death), especially for severely ill patients that are admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) [4–7]. There exist prognostic instruments available such as palliative prognostic score (PaP) [8], palliative prognostic index (PPI) [9], acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE), [10] and simplified acute physiology score (SAPS) [11]. However, these tools have significant shortcomings because they are derived from a population of patients that are already determined to be terminally ill, making them less relevant for patients who are still receiving anti-cancer treatment [12].

Generally, an outcome prediction model is developed using one of these two approaches: I) patient similarity or II) predictive modeling. A patient similarity-based model makes predictions by identifying and analyzing past patients who are similar to a present case through a correlation metric [13, 14]. On the other hand, a predictive modeling requires the extraction of features of interest, followed by the modeling of desired outcome using machine learning algorithms [15, 16]. Several studies have demonstrated the comparison of patient similarity vs. predictive modeling, for which the latter outperformed the former in terms of predictive values [17, 18]. Traditionally, clinical prognosis has been derived from clinical covariates or biomarkers available in the electronic medical record (EMR), that usually cover a variety of aspect of a patient’s health state such as vital signs, physiological variables, demographic information, and laboratory test results [12, 13, 17, 18]. These approaches resulted in accuracy between 60 and 80% [19, 20]. Nonetheless, radiographically induced biomarkers have started to show potential in prognostic models [21–23]. The latter claimed to be at advantage due to its non-invasive nature while showing improvement over the traditional approach. In addition, EMR often contains many missing values, imposing great challenges in the traditional method.

In the present study, we seek to investigate the prognostic impact provided by clinical biomarkers (CBMs) and imaging biomarkers (IBMs), as well as the hybrid of both, termed hybrid biomarkers (HBMs). Our hypotheses are as follows: (a) IBMs deliver better discrimination power in a clinical prognostication in comparison to CBMs, (b) IBM approach of modelling the prognostic model is general and applicable to different kind of patient outcome prediction, though our main focus in this work is the survival prediction, and (c) there is an added value provided by IBMs in combination with CBMs while making prediction of patient outcomes. The group of patients targeted to validate these hypotheses are taken from a public Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) archive. Post-surgical prognostic models are developed for patients who show signs of nodule internal features such as cavitation, cysts, reticulation and air bronchogram pre-surgery. The motivation behind this targeted group is to investigate if the pre-operative radiographic features can predict tumor invasiveness based on air/gas to tissue proportion and thus, aiding physicians to determine the most appropriate surgical procedure in such cases. As the literature indicates, lung cancers that show wider section of radiolucency such as Ground Glass Opacity (GGO) are considered to have more favorable diagnosis than solid tumors [24, 25]. The objective of this study is however not to re-iterate what is already known in the literature, but to explore the possibility of improving clinical decisions through an enhanced prognostic model using a collection of so-called informative image-based covariates as well as establishing their relationship to clinical endpoints.

Methods

Clinical materials

Imaging and clinical records of patients diagnosed with primary NSCLC, who received surgical excision were obtained from a public repository, the cancer imaging archive (TCIA) [26]. The cohort consists of 211 subjects that underwent both computed tomography (CT) and Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (PET/CT) scans. Semantic annotations and segmentation maps of the tumor were available. Inclusion criteria encompassed subjects of stage I-IV cancer with either cysts, cavitation, reticulation, or air bronchogram sign. There were 48 males and 20 females with mean age of 69.5 and 66.5 years, respectively. Subjects without tumor internal characteristics or incomplete records were all excluded. Five-year survival was calculated from the day of surgery to the last follow-up date. The dataset’s characteristics are supplemented in Table 1. The acquisition protocol varied slightly for different patients, depending on each patient’s size. Exposure settings were constant at 120 kVp, with tube current ranging from 50 to 750 mAs. Pixel spacing and slice thickness ranged from 0.596 to 0.976 mm and 0.625 to 3.75 mm respectively. The images were reconstructed at 512 × 512-pixel matrices.

Table 1.

The details of dataset used in this work

| Dataset characteristics | No | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 211 | 100 |

| Incomplete records | 50 | 24 |

| Complete records | 161 | 76 |

| Internal features present | 68 | 42 |

| I) Air Bronchogram | 24 | 35 |

| II) Cavitation | 15 | 22 |

| III) Cysts | 4 | 6 |

| IV) Reticulation | 5 | 7 |

| V) Mix of above | 20 | 29 |

| Internal features absent | 91 | 58 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | (48/68) | 71 |

| Female | (20/68) | 29 |

| Age | ||

| ≤ 70 | (36/68) | 53 |

| > 70 | (32/68) | 47 |

| Pathological staging | ||

| Primary tumor T | ||

| I | (30/68) | 44 |

| II | (25/68) | 37 |

| III | (9/68) | 13 |

| IV | (4/68) | 6 |

| Lymph node N | ||

| 0 | (56/68) | 82 |

| 1 | (4/68) | 6 |

| 2 | (8/68) | 2 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Metastasis M | ||

| 0 | (66/68) | 97 |

| 1 | (2/68) | 3 |

| Histology | ||

| Squamous cell | (10/68) | 15 |

| Non-Squamous cell | (58/68) | 85 |

| 5-year overall survival | ||

| Survived | (23/68) | 34 |

| Expired | (45/68) | 66 |

Tumor delineation

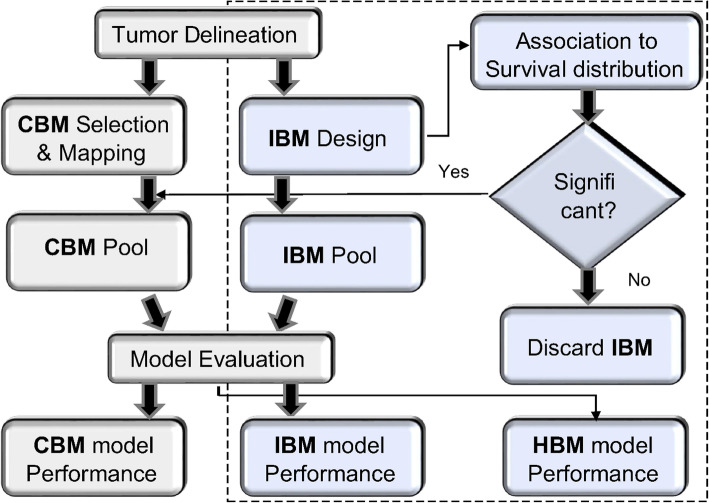

Figure 1 outlines the processes required to achieve the objectives of this study. Tumor delineation was a pre-processing step and was performed using an automated tool developed using geometrical and topological processing to facilitate this process [27]. It eliminates the manual delineation work required in this study.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the proposed model. The extended framework is indicated on the right side of the model, inside the dotted lines

CBM selection and mapping

Two main models were referenced during the selection of clinical biomarkers in this work: Wallington et al. [19] and Jochems et al. [20]. Both investigated the prediction of survival in NSCLC patients using CBM readily available from a patient’s record such as demographics, tumor staging, tumor size, and treatment history. Wallington’s model used age, gender, BMI, tumor staging, income deprivation, performance status, and history of previous treatment as the predictors, whereas Jochems’s model used age, gender, tumor size, tumor staging, total dose, performance status, and chemo-timing. Following their guidelines, we have chosen the nine CBMs most similar to their studies that were available in our dataset, as depicted in Table 1. Accordingly, some of these variables had to go through a feature transformation in order to map those that mostly exist either in nominal or categorical form to more classifier-friendly variables. Gender, for instance, went through a transformation from nominal (female, male) to categorical (0, 1) values while TNM-staging went through a mapping from categorical values (1,2,3,4) to numeric values calculated based on the percentage of their composition in the dataset. This is performed to avoid matrix sparsity. The details of each clinical variable mapping work are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

CBMs selection and their mapping work

| Covariates | Type | Range | Conversion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Nominal | {Male, Female} | (0,1) |

| Age | Real | (42–87) | NA* |

| Weights (lbs) | Real | (80–318) | NA |

| Smoking years | Real | (0–41) | NA |

| Histology | Nominal | {Squamous, Non-Squamous} | (0,1) |

| T | Categorical | [1–4] | Number of patients in a stage divided by total number of patients (e.g., 16 patients categorized as T1; those patients were given 0.235 (16/68) value). |

| N | Categorical | [0,1,2,3] | |

| M | Categorical | [0,1] | |

| Tumor size (mm) | Real | (11.7–73.9) | NA |

*NA means no conversion work is needed

IBMs design

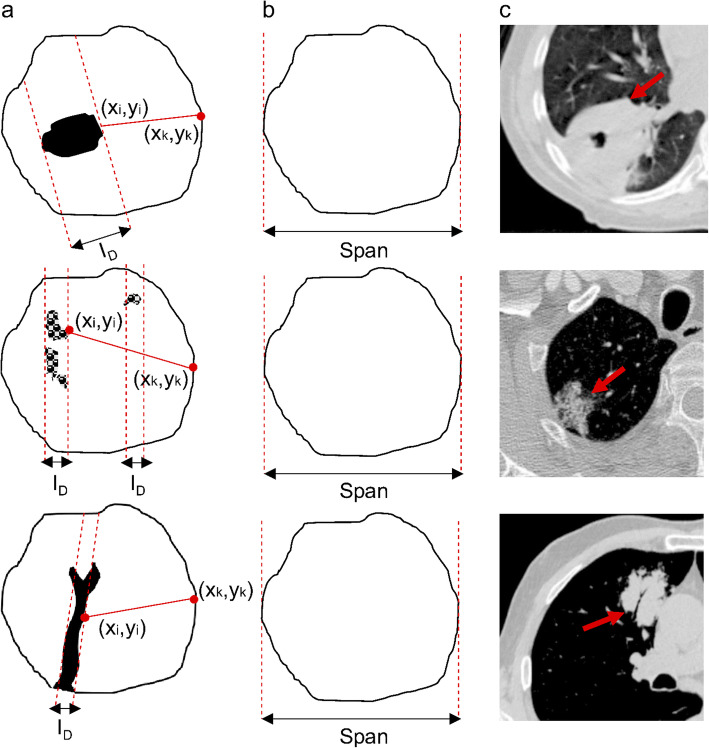

The areas of decreased density in computed tomography are described by specific radiologic lexicons such as cavitation, cysts, reticulation, and air bronchogram signs. Many of these terms are based on the pathogenesis and the opacification characteristics possessed by the lung abnormalities. The decreased in a nodular attenuation pattern develops when the density in parenchyma decrease caused by: (a) abnormal increase in the amount of air, (b) abnormal decrease in blood volume, or (3) loss of soft tissue structures. Each of these phenomena may results in different pattern of decreased density for instance those depicted in Fig. 2 (c).

Fig. 2.

Example of decreased density areas in a tumor. Rows from top to bottom represent cavitation, reticulation, and air-bronchogram sign phenomena, respectively. Meanwhile columns A to C show illustration of the internal features, the tumor mask, and an example of CT scan for each case. The solid and non-solid components are designated by white and black colors in the first column, respectively

To validate our hypothesis, eight customized IBMs were introduced in this work to quantify the solid and non-solid composition of a tumor with internal characteristic. The internal features included were cysts (radiolucency with a thin wall), cavitation (radiolucency with a thick wall), reticulation (lucent spaces created by the intersection of fine, medium or coarse lines) and air-bronchogram sign (gas-filled bronchi surrounded by alveoli filed with fluid, pus or other substances). The gray-level images are first converted to binary images as depicted by a few examples in Fig. 2.a. We created a tumor mask for each binary tumor as depicted by Fig. 2.b. Table 3 shows the definition of covariates we used to design the imaging biomarkers, where we used the term A and B to denote binary images (Fig. 2.a) and mask images (Fig. 2.b), respectively. Our fundamental approach is simple in which the white pixels in both A and B refer to solid areas of tumors, whereas the black pixels refer to the non-solid areas. PA and PB represent the counts of pixel of A and B.

Table 3.

The list of covariates used to derive eq. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8. Active pixels refer to the white pixels in binary images

| Covariates | Definition |

|---|---|

| PA | The number of active pixels in A |

| PB | The number of active pixels in B |

| P (B∩A) | The number of active pixels that are true for both A and B |

| n | The number of effected slices |

| (x,y) |

The contour vertices: - - Air pocket contour vertices (xi,yi) - Solid wall contour vertices (xk,yk) |

| Span | The longest distance between two vertices of the tumor mask |

| ID | Inner diameter of a lucent area. If more than one area is present, the average is calculated. |

Equation 1 measures the proportion of solid component (radiodensity) of a tumor with internal features. The solid components are those that appear opaque white or grey in CT scans. RDC should range between 0 and 1.

| 1 |

A and B are depicted in Fig. 2.

Equation 2 is an IBM that quantifies the proportion of decreased density areas of a tumor with internal features. These so-called non-solid components appear as black in CT scans. Similarly, RLCs fall between 0 and 1 ranges. RDC, and RLC are inter-correlated in a way that each calculates the ratio of radio-density and radio-lucency of the same tumor area.

| 2 |

Difference in composition as depicted in Eq. 3 calculates the difference in the solid and non-solid composition in Eq. 1 and 2.

| 3 |

An IBM computing the fraction of radiolucency to radiodensity (non-solid to solid) areas is introduced in Eq. 4. It measures the air to tissue ratio of a tumor.

| 4 |

Length of the solid area as shown in Eq. 5 searches for the longest path between the radio-lucent to the radio-dense boundaries. It refers to the wall of a tumor with internal features. If more than one radio-lucent area is present, the algorithm chooses the largest one to computes the boundary vertices.

| 5 |

The sixth biomarker as depicts in Eq. 6 quantifies the ratio of LoSA to the diameter of a tumor mask (Span), where no lucent area is observed.

| 6 |

To gain further insight of the possible differences between solid vs non-solid components of a tumor, IBMs measuring the length of a lucent area as well as the ratio of their averaging length (for multi-lucency cases) to the diameter of the tumor were also investigated. Eq. 7 demonstrates the average length of cavities, whereas Eq. 8 shows the quantification of the averaged diameter of the lucent areas over the diameter of the tumor mask (B in Fig. 2)

| 7 |

| 8 |

In order to match the number of CBMs, we included an existing measurement in literature, solidity as the final IBM. Solidity calculates the ratio of true pixels between the tumor and its bounding box.

Model evaluation

To test the first hypotheses, three set of test cases were drawn as shown in Table 4. The predictors were fed into four off-the-shelf classifiers to predict the probability of patients survived or expired 5 years after surgery. The classifiers were chosen based on recent similar published works of predicting survival of lung cancer: Wallington et al., Logistic Regression (LR) [19], Jochems et al., Random Forest (RF) [20], Hazra et al., Support Vector Machines (SVM) [28], and Rodrigo et al., Artificial Neural Network (ANN) [29].

Table 4.

The set of predictors forming three test cases; CBM, IBM, and HBM. The HBM are a combination of CBMs and selected IBMs

| CBM pool | IBM pool | HBM pool | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | RDC | Age | + | Selected imaging biomarkers based on correlation testing. |

| Gender | RLC | Gender | ||

| Weights | DoC | Weights | ||

| Smoking years | ATR | Smoking years | ||

| Histology | LoSA | Histology | ||

| T stage | LoSAR | T stage | ||

| N stage | LoCA | N stage | ||

| M stage | LoCAR | M stage | ||

| Tumor size | Solidity | Tumor size | ||

The predictive performance was evaluated using a cost-sensitive measure which is area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) or AUC. Cost insensitive measures such as accuracy, precision, and recall, might be biased in our case due to the nature of the dataset that is skewed towards one class. AUC is visualization tool for which may appropriately determine the appropriateness of a classifier. On top of that, to mitigate the concern on skewed dataset, the 10-fold cross validation was incorporated to stratify the samples and ensure that the ratio between positive and negative case in each fold are similar to that in the entire dataset. In other words, the dataset is first divided into two strata, then random assignment to the folds is carried out in each stratum independently [30]. Integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) was implemented to measure the significant difference, if it exists, between the AUCs returned by each model [31]. IDI index is commonly used to compare two risk prediction models or taking the difference between two competing models. For instance, when comparing the CBM-based model to the IBM-based model performance, the index tells the improvement in prediction without the inherit problems of directly comparing c-statistics.

Correlating IBMs to survival distribution

In this section, the prognostic impact of the proposed IBMs performed through uni- and multi-variable analyses, with the chi-squared test or D’Agosstino-Pearson opted for normality testing for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival curve, Cox Proportional Hazard model, and the log-rank test were the methods used to investigate these correlations. KM estimator used to estimate the survival function from life-time data, for example, the fraction of patients living for a certain amount of time after treatment [32], while the log-rank test is a hypothesis test to compare the survival distribution between two groups. Both KM and the log-rank test are examples of univariable analysis and non-parametric statistic. They describe the survival according to one factor under investigation but ignore the impact of another. Cox Proportional Hazards is a regression model that extends survival analysis to assess simultaneously, the effect of several factors on survival time. It allows the examination on how specific covariate influence the event of interest at a particular point of time. The rate is known as hazard ratio [33]. Descriptive data were summarized as mean and median with 95% confidence interval, while categorical data was given as count or proportion. Statistical significance is given by a two-tailed p-value lower than 0.05.

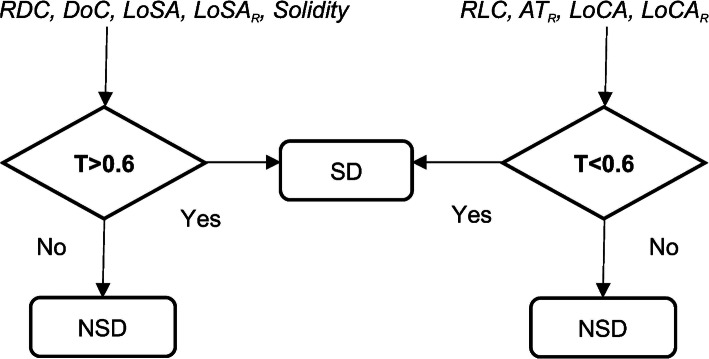

The subjects were divided into two comparative groups using the proposed IBMs. RDC, DoC, LoSA, LoSAR, and Solidity are IBMs that are associated to quantify denser composition of a tumor, whereas RLC, ATR, LoCA, and LoCAR, are the IBMs that concentrated on quantifying the less dense portion of a tumor. All IBMs measurements are in the range of 0–1 hence a threshold of 60% (0.6) was set to divide the subjects into two groups that we named as solid dominant (SD) and non-solid dominant (NSD). Figure 3 presents how this work took place. All algorithms were implemented using MATLAB (R2015b) and all statistical analyses were conducted using MedCalc software version 17.5.5.

Fig. 3.

Two sub-groups created based on the threshold by each IBM. In the case a measurement that is not a ratio, such as LoSA and LoCA, a posterior probability is calculated prior the threshold setting

Results

Prediction of 5-year survival

The prediction of 5-year survival were evaluated between models that were built based on CBM versus models built using the proposed IBM. Table 5 depicts the performance metric AUC and IDI for the prediction of post-surgery survival for patients with nodule internal features by both methods. All four classifiers demonstrated significant improvement in the proposed IBM model with IDI ranged between 0.47–0.54 (p < 0.05) in which the ANN and RF showing the highest jump from CBM to IBM model. IBM seemed to successfully boost the prediction accuracy above 0.80 in all classifiers tested in comparison to its counterpart, CBM model that demonstrated AUC ranged between 0.59–0.75. We observed that Logistic Regression outperformed the Random Forest classifier in both CBM and IBM models, which is actually contradictory to the finding in Jochems et al. [20] that we used as our main reference. Interestingly, in terms of the percentage of improvement, Random Forest is indeed among the classifiers having significant boosting performance (p < 0.001). We believe parameters tuning has something to do with these observations, as Random Forest required a few parameters to be tuned, for instance, the number of branches. This experiment confirmed our first hypothesis.

Table 5.

Performance comparisons of AUC for the survival prediction in both models

| Classifiers | CBM (AUC) | IBM (AUC) | IDI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 0.75 | 0.93 | 0.47 | 0.002* |

| Random Forest | 0.61 | 0.83 | 0.54 | < 0.001* |

| Support Vector Machine | 0.74 | 0.92 | 0.50 | < 0.001* |

| Artificial Neural Network | 0.59 | 0.82 | 0.52 | < 0.001* |

* representing significance data

Association to survival ends

We have seen IBM outperformed CBM method in survival prediction. To derive further insights on the probable reason underlying this observation, association test was conducted on both type of biomarkers. Tables 6 and 7 depict the correlation of CBM and IBM to overall survival respectively. The univariable analysis has demonstrated that four CBMs were found to be significant factors predicting the overall survival in the studied case; age [HR: 2.235, (r = 0.26, p = 0.037)], lymph node involvement [HR: 3.797, (r = 0.23, p = 0.056)], metastasis event [HR: 4.863, (r = 0.11, p = 0.368)], and tumor size [HR: 1.059, (r = 0.37, p = 0.002)]. The multivariable analysis only retained age and lymph node involvement from this pool; [χ2 (2) =14.498, p = 0.0007]. With these observations, we have concluded that age and lymph node involvement were the risk factors useful in the survival prediction.

Table 6.

Uni- and multi-variable survival analysis for CBMs were performed through KM and Cox proportional hazard model, respectively

| Biomarkers | Univariable | Multivariable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Demographic factors | ||||

| Age | ||||

| ≤ 70 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 70 | 2.235 | 1.097–4.556a | 2.257 | 1.240–4.111 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | |||

| Female | 1.015 | 0.560–1.837 | ||

| Weights | ||||

| ≤ 150 | 1 | |||

| > 150 | 1.070 | 0.604–1.897 | ||

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Yes | 1 | |||

| No | 1.623 | 0.872–3.021 | ||

| Clinical factors | ||||

| Primary Tumor | ||||

| ≤ T2 | 1 | |||

| > T2 | 0.904 | 0.446–1.830 | ||

| Lymph Node | ||||

| N0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ N1 | 3.797 | 1.038–13.887a | 4.163 | 1.858–9.326 |

| Metastasis | ||||

| M0 | 1 | |||

| M1 | 4.863 | 0.238–99.479a | ||

| Histology | ||||

| Squamous | 1 | |||

| Non-Squamous | 1.194 | 0.582–2.452 | ||

| Tumor size | ||||

| Longest diameter | 1.059 | 1.010–1.110a | ||

* representing significant data; HR Hazard ration, CI Confidence interval

Table 7.

Uni- and multi-variable survival analysis for IBMs were performed through KM and Cox proportional hazard model, respectively

| Biomarkers | Univariable | Multivariable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Solid Composition | ||||

| RDC | ||||

| SD | 1 | 1 | ||

| NSD | 2.225 | 1.149–4.307* | 0.431 | 0.232–0.769 |

| DoC | ||||

| SD | 1 | |||

| NSD | 1.583 | 0.749–3.342 | ||

| LoSA | ||||

| SD | 1 | |||

| NSD | 1.963 | 1.019–3.781 | ||

| LoSAR | ||||

| SD | 1 | 1 | ||

| NSD | 2.445 | 1.345–4.443* | 0.395 | 0216–0.708 |

| Solidity | ||||

| SD | 1 | |||

| NSD | 1.908 | 0.930–3.915* | ||

| Lucent Composition | ||||

| RLC | ||||

| SD | 1 | |||

| NSD | 2.225 | 1.149–4.307* | ||

| ATR | ||||

| SD | 1 | |||

| NSD | 2.018 | 1.011–4.028* | ||

| LoCA | ||||

| SD | 1 | |||

| NSD | 0.643 | 0.337–1.225 | ||

| LoCAR | ||||

| SD | 1 | 1 | ||

| NSD | 2.274 | 1.153–4.488* | 0.422 | 0.232–0.769 |

* representing significant data; HR Hazard ration, CI Confidence interval

On the other hand, only DoC, LoSA, and LoCA were not statistically significant in predicting survival between two groups (SD vs. NSD) using IBMs. We also observed that two IBMs; RDC and RLC showing similar prognostic impact [HR: 2.225, (r = ±0.67, p < 0.0001)], which was believed due to the reason that they are correlated to each other in a way that one complements another. Multivariable analysis retained three IBMs from the significant pool which were RDC, LoSAR, and LoCAR; [χ2 (3) =42.631, p < 0.0001]. Following these observations, the comparison of mean and median survival time between the subjects grouped were also investigated and shown in Table 8. It was observed that the groups differed between 1.64–2.23 years in the mean survival and 0.46–2.00 years in the median survival. The survival curves are supplemented in supplementary file S1.

Table 8.

Mean and median survival as calculated from Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Only IBM which gives statistical significance as demonstrated by the univariate analysis in Table 7 is included in this table

| Biomarkers | 5-Year Overall Survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Difference | Median | 95% CI | Difference | |

| Solid Composition | ||||||

| RDC | ||||||

| SD | 5.20 | 4.27–2.57 | 2.04 | 4.43 | 2.93–5.48 | 1.17 |

| NSD | 3.16 | 2.57–3.74 | 3.26 | 2.49–3.90 | ||

| LoFAR | ||||||

| SD | 5.50 | 4.46–6.61 | 2.23 | 5.20 | 3.11–5.24 | 2.00 |

| NSD | 3.27 | 2.75–3.79 | 3.20 | 2.71–3.84 | ||

| Solidity | ||||||

| SD | 4.96 | 4.08–5.85 | 1.64 | 3.90 | 2.85–5.48 | 0.58 |

| NSD | 3.32 | 2.68–3.96 | 3.32 | 3.15–3.84 | ||

| Lucent Composition | ||||||

| RLC | ||||||

| SD | 5.20 | 4.27–2.57 | 2.04 | 4.43 | 2.93–5.48 | 1.17 |

| NSD | 3.16 | 2.57–3.74 | 3.26 | 2.49–3.90 | ||

| ATR | ||||||

| SD | 5.05 | 4.11–5.99 | 1.69 | 3.78 | 2.76–5.48 | 0.46 |

| NSD | 3.36 | 2.82–3.90 | 3.32 | 3.15–3.90 | ||

| LoCAR | ||||||

| SD | 5.17 | 4.24–6.11 | 2.03 | 3.99 | 3.32–5.48 | 0.83 |

| NSD | 3.14 | 2.59–3.69 | 3.16 | 2.49–3.84 | ||

Data are presented in years

Leveraging the hybrid biomarkers for patient outcome predictions

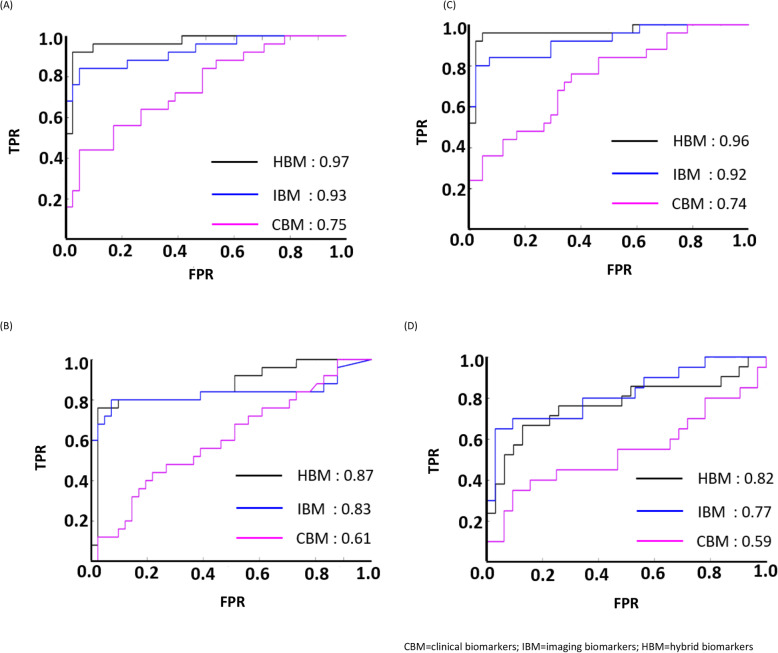

Based on findings in the previous section, four IBMs (RDC, RLC, LoSAR, LoCAR) with prognostic values were leveraged into a hybrid model that combine them with all of the clinical predictors. This hybrid model is termed as hybrid biomarkers (HBM). Similar survival predictions were conducted and the ROC curves and AUCs were plotted to compare the performance of all three models. Figure 4 demonstrates the comparison between all models for the survival prediction. We observed that HBM based model, to some extent boosted the performance of IBM further by 4% in all but ANN classifier. Though HBM managed to surpass the performance of CBM based model, IBM was seen to work best for ANN.

Fig. 4.

The comparison of ROC curves in the survival prediction for all models in: a Logistic Regression, b Random Forest, c Support Vector Machines and d Artificial Neural Network

Discussion

We have investigated the efficacy of combining archival clinical data with radiographically induced data in personalizing the risk stratification of NSCLC patients undergoing anti-cancer treatment. Eight image-based biomarkers were introduced customized to the case being studied, in which six demonstrated statistical significance in the mean and median survival. This finding could be a useful input for the precision medicine community in identifying patients with higher risk to be put under additional therapeutic planning. The proposed biomarkers may provide alternative factors for oncologists investigating tumor-specific factors during treatment planning, which is a less-invasive method than biopsy or resection sampling.

The results support all hypotheses made in which the imaging measures are superior predictors in comparison to clinical measures, and thus confirms the utility of incorporating image-based predictors into the traditional approach of using clinical-based predictors in modeling the patient outcome prediction. Although significant improvement was observed in the image-based predictive model over the traditional model, the hybrid between them was seen to outperform both standalone models, in most cases. Although there was a standout case in ANN classifier, where the hybrid predictors fall slightly short behind imaging predictors, which merits further investigation, this does not forfeit the third hypothesis since the clinical predictors still underperformed in comparison to the hybrid predictors.

Demographics, histology and pathological staging are among clinical indicators that have been proven in the literature [34–36], hence previous works on predicting survival among NSCLC patients are concentrated on mixing these readily available clinical factors with AUCs range between 0.62–0.79 [19, 20, 27, 28]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study establishing the fusion of both clinical with imaging covariates, which has been proven to better predict survival (AUCs between 0.77 and 0.97). Even though the concept of imaging measures as biomarkers is not relatively new [22, 23, 37], the thought of having to go through complex imaging analysis with advanced software might have hindered the unique benefit it may provide. Imaging biomarkers are the corner stone of modern radiology. They might be a major player in therapeutic decisions and drugs evaluation in the near future; thus, multi-disciplinary experts are expected to co-work in order to make this possible.

This study is not without limitations. One of the weaknesses is the number of subjects available, since we have to exclude a rather large number of subjects with incomplete records (23.7%) from the dataset. Such issue arises when dealing with archival data originating from routine clinical practice. Furthermore, the dataset is skewed towards negative cases which may have been the compounding factor in some of the classifier performance reported in this study. A more complete and balanced sample may give us better representation of the proposed model, thus warranting further investigation of the technique that will allow us to improve the current work. One possible solution to both problems, the skewed dataset and small sample size, is a synthetic data generator. As we are dealing with CT images, several studies have demonstrated the application of Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to generate synthetic medical images through this generator-discriminator dual network [38–40]. This new data augmentation technique that works through image-to-image translation is a potential novel method on a limited dataset of medical images like ours. This could be a fascinating follow up work after this study, and in fact a preliminary screening of similar work has been started. Lastly, the present subjects included in this study originated from a single center. Additional studies in multiple centers are needed to confirm these results, particularly on the selection of the threshold value of dividing the solid versus non-solid dominant by the proposed biomarkers.

Despite these issues, we have confidence that it is possible to improve the current model such that it leads to more discoveries that can possibly enhance cancer care as more data become available. On top of this, with the recent pandemic of COVID-19, the proposed methodology holds potential in predicting the severity of COVID-19 in patients with lung cancer who tested positive with a SARS-CoV-2 by combining traditional biomarkers such as lab data including blood count, serum creatinine, and inflammatory markers with imaging data taken either on the same day, or the day after patient tested positive. Such a finding is an essential part of the international response to the pandemic, especially with regards to lung cancer patients.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that our customized model has shown better prognostic impact in comparison to the one-fits-all traditional model. The so-called patient specific model provides empirical evidence for the personalized medicine community as well as data-driven decision support system.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 : Fig. 1. The survival distribution is plotted as KM curves using each of the proposed biomarkers as a risk factor. The comparison groups are given as patients clustered into solid-dominant (SD) and non-solid dominant (NSD) tumor groups.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- IBMs

Imaging biomarkers

- NSCLC

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

- ROC

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- AUC

Area under the ROC curves

- KM

Kaplan-Meier

- APACHE

acute physiology and chronic health evaluation

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- PaP

Palliative prognostic score

- PPI

Palliative prognostic index

- EMR

Electronic medical record

- CBMs

Clinical biomarkers

- IBMs

Imaging biomarkers

- HBMs

Hybrid biomarkers

- GGO

Ground Glass Opacity

- TCIA

The cancer imaging archive

- CT

Computed tomography

- ROI

Region of interest

- LR

Logistic Regression

- RF

Random Forest

- ANN

Artificial Neural Network

- IDI

Integrated discrimination improvement

- SD

Solid dominant

- NSD

Non-solid dominant

Authors’ contributions

MS and IHL both contributed to the study design and manuscript preparation. MS also performed all experiments, analyses, and interpretations. IHL supervised the process and revised the manuscript accordingly for the submission. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program (2017R1D1A1B03033526) and Priority Research Centers Program (NRF-2017R1A6A1A03015562) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the ministry of Education. The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset was collected from TCIA (10.7937/K9/TCIA.2017.7hs46erv). This collection is freely available to browse, download, and use for commercial, scientific and educational purposes as outlined in the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. The dataset consists of DICOM images, AIM annotations, clinical data, and RNA sequence data (GSE103584).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study used data from a publicly available archive; hence, no informed consent or ethics approval gain prior to the study were necessary. However, the original authors who submitted this dataset to TCIA mentioned that the dataset is IRB approved.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Maliazurina Saad, Email: mbs@illinois.edu.

Ik Hyun Lee, Email: ihlee@kpu.ac.kr.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12911-020-01262-3.

References

- 1.Simss L, Barraclough H, Govindan R. Biostatistics primer: what a clinician ought to know-prognostic and predictive factors. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:808–813. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318292bdcd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atashi A, Sarbaz M, Marashi S, Hajialiasgari F, Eslami S. Intensive care decision making: using prognostic models for resource allocation. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2018;251:145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith PG, Morrow RH, Ross DA. Field Trials of Health Interventions: A Toolbox. 3rd Ed. Oxford. 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pirracchio R, Petersen ML, Carone M, Rigon MR, Chevret S, Mark J. Van der LAAN. Mortality prediction in the ICU: can we do better? Results from the super ICU learner algorithm (SICULA) project, a population-based study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(1):42–52. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awad A, Bader-El-Den M, McNicholas J, Briggs J. Early hospital mortality prediction of intensive care unit patients using an ensemble learning approach. Int J Med Inf. 2017;108:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipshutz AKM, Feiner JR, Grimes B, Gropper MA. Predicting mortality in the intensive care unit: a comparison of the university health consortium expected probability of mortality and the mortality prediction model III. J Intensive Care. 2016;4(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s40560-016-0158-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J, Dubin JA, Maslove DM. Mortality prediction in the ICU. In: Secondary Analysis of Electronic Health Records. Cham: Springer; 2016. pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pirovano M, Maltoni M, Nanni O. A new palliative prognostic score: a first step for the staging of terminally ill Cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1999;17(4):231–239. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S. The palliative prognostic index: a scoring system for survival prediction of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 1999;7:128–133. doi: 10.1007/s005200050242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner DP, Draper EA. Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE II) and medicare reimbursement. Health Care Financ Rev. 1984:91–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Gall LJR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPSII) based on a European/north American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270(24):2957–2963. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.24.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramchandran KJ, Shega JW, Roenn JV, Schumacher M, Szmuilowicz E, Rademaker A, Weitner BB, Loftus PD, Chu IM, Weitzman S. A predictive model to identify hospitalized cancer patients at risk for 30-day mortality based on admission criteria via the electronic medical record. Cancer. 2013;119(11):2074–2080. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J, Maslove DM, Dubin JA. Personalized mortality prediction driven by electronic medical data and a patient similarity metric. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0127428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Sharafoddini A, Dubin JA, Lee J. Patient similarity in prediction models based on health data: a scoping review. JMIR Med Inform. 2017;5(1):e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Wojtusiak J, Elashkar E, Nia RM. C-Lace: Computational model to predict 30-day post-hospitalization mortality. 2017. pp. 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S, Kim W, Park RW. A comparison of intensive care unit mortality prediction models through the use of data mining techniques. Healthc Inform Res. 2011;17(4):232–243. doi: 10.4258/hir.2011.17.4.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoogendoorn M, El Hassouni A, Mok K, Ghassemi M, Szolovits P. 38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) 2016. Prediction using patient comparison vs. modeling: a case study for mortality prediction. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morid MA, Liu Sheng OR, Abdelrahman S. PPMF: A patient-based predictive modeling framework for early ICU mortality prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.07499. 2017.

- 19.Wallington M, Saxon EB, Bomb M, et al. 30-day mortality after systemic anticancer treatment for breast and lung cancer in England: a population-based, observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):1203–1216. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30383-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jochems A, El-Niqa I, Kessler M, et al. A prediction model for early death in non-small cell lung cancer patients following curative-intent chemoradiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(2):226–230. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1385842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carneiro G, Oakden-Rayner L, Bradley AP, Nascimento J, Palmer L. Automated 5-year mortality prediction using deep learning and radiomics features from chest computed tomography. IEEE Int Symp Biomed Imaging. 2017. p. 130–4.

- 22.Saad M, Choi TS. Computer-assisted subtyping and prognosis for non-small cell lung cancer patients with unresectable tumor. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2017;67:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aerts HJWL, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RTH, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4006. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsutani Y, Miyata Y, Yamanaka T, et al. Solid tumors versus mixed tumors with a ground glass opacity component in patients with clinical stage 1A lung adenocarcinoma: prognostic comparison using high-resolution computed tomography findings. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hattori A, Suzuki K, Maeyashiki T, et al. The presence of air bronchogram is a novel predictor of negative nodal involvement in radiologically pure-solid lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;45(4):699–702. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bakr S, Gevaert O, Echegaray S, et al. Data for NSCLC Radiogenomics Collection. The Cancer Imaging Archive. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saad M, Lee IH, Choi TS. Automated delineation of non-small cell lung cancer: a step towards quantitative reasoning in medical decision science. Int J Imaging Syst Technol. 2019:1–16.

- 28.Hazra A, Bera N, Mandal A. Predicting lung cancer survivability using SVM and Logistic Regression Algorithms. Int J Comp Appl. 2017:174(2).

- 29.Rodirigo H, Tsokos CP. Artificial neural network model for predicting lung cancer survival. JDAIP. 2017;5:33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kriegeskorte N. Cross validation in brain imaging analysis. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Louis M, et al. Dynamic data during hypotensive episode improves mortality predictions among patients with sepsis and hypotension. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(4):954–962. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182772adb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manish KG, Pardeep K, Jugal K. Understanding survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimate. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1(4):274–278. doi: 10.4103/0974-7788.76794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christensen E. Multivariate survival analysis using Cox’s regression model. Hepatology. 1987;7:1346–1358. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brzezniak C, Satram-Hoang S, Goerts HP, et al. Survival and racial differences of non-small cell lung cancer in the United States military. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1406–1412. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3280-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lara JD, Brunson A, Riess JW, et al. Clinical predictors of survival in young patients with small cell lung cancer: results from the California Cancer registry. Lung Cancer. 2017;112:165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Veisani Y, Delpisheh A, Sayehmiri K, et al. Demographic and histological predictors of survival in patients with gastric and esophageal carcinoma. Iranian Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15(7):547–553. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.11847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grove O, Berglund AE, Schabath MB, et al. Quantitative computed tomographic descriptor associate with tumor shape complexity and intratumor heterogeneity with prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0118261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yi X, Walia E, Babyn P. Generative adversarial network in medical imaging: a review. Computer Science, Mathematics, Medicine. Medical Image Analysis. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandfort V, Yan K, Pickhardt PJ, et al. Data augmentation using generative adversarial networks (CycleGAN) to improve generalizability in CT segmentation tasks. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16884. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52737-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frid-Adar M, Diamant I, Klang E, et al. GAN-based synthetic medical image augmentation for increased CNN performance in liver lesion classification. Neurocomputing. 2018;321(10):321–331. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 : Fig. 1. The survival distribution is plotted as KM curves using each of the proposed biomarkers as a risk factor. The comparison groups are given as patients clustered into solid-dominant (SD) and non-solid dominant (NSD) tumor groups.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset was collected from TCIA (10.7937/K9/TCIA.2017.7hs46erv). This collection is freely available to browse, download, and use for commercial, scientific and educational purposes as outlined in the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. The dataset consists of DICOM images, AIM annotations, clinical data, and RNA sequence data (GSE103584).