Abstract

Herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) causes recurrent mucocutaneous lesions in the eye that may advance to corneal blindness. Nucleoside analogs exemplified by acyclovir (ACV) form the primary class of anti-herpetic drugs but this class suffers limitations due to the emergence of viral resistance and other side effects. While studying the molecular basis of ocular HSV-1 infection, we observed that BX795, a commonly used inhibitor of TANK-binding kinase-1 (TBK1), strongly suppressed infection by multiple strains of HSV-1 in transformed and primary human cells, cultured human and animal corneas, and a murine model of ocular infection. Our investigations revealed that the antiviral activity of BX795 relies on targeting Akt phosphorylation in infected cells leading to the blockage of viral protein synthesis. This small molecule inhibitor, which could also be effective against ACV-resistant HSV-1 strains, shows promise as an alternative to existing drugs and as an effective topical therapy for ocular herpes infection. Collectively, our results obtained using multiple infection models and virus strains establish BX795 as a promising lead compound for broad-spectrum antiviral applications in humans.

One sentence summary:

A kinase inhibitor shows promise as a topical antiviral against ocular herpes.

Introduction

Herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) is among the most common human pathogens, with worldwide prevalence estimated to be in the range of 50–90% (1). It is primarily known to cause orofacial and ocular diseases; however, HSV-1 related genital cases are increasingly reported (2). The virus establishes a lifelong latent infection in the trigeminal ganglia (TG), and recurrent infection leads to complications including vision loss and lethal meningoencephalitis (3). Advanced HSV-1 corneal infection represents the leading cause of infectious blindness, while and virus dissemination to the nervous system may cause lethal meningoencephalitis (3, 4). Acyclovir (ACV) and its analogs are the primary treatment options available for ocular herpes. ACV, Valacyclovir, and Famciclovir are usually administered systemically and Trifluridine (trifluorothymidine) (TFT) and Ganciclovir gel are applied administered topically (5)(6). Although ACV and its analogs have been effective in controlling infection, they suffer from many limitations: (i) as nucleoside analogs they rely on blocking viral DNA duplication and do not act directly to prevent viral protein synthesis (7), (ii) cases of drug resistance including escape mutants are frequently reported (8–12), (iii) prolonged use of TFT can cause other ocular disorders (13–15) and prolonged use of ACV can cause nephrotoxicity (16–18), and (iv) nucleoside analogs have the potential to be a chromosomal mutagen and therefore, often are not prescribed during pregnancy (19). Therefore, there is an imminent need to develop new treatment options with alternative mechanisms of antiviral action (12).

In this study, our findings reveal a promising role of BX795 as an antiviral agent against HSV-1 infection. BX795 is a well-studied inhibitor of TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) (20). TBK1 is one of two IκB kinase related homologs known to play key roles in regulating innate immunity, neuroinflammation, autophagy, cell survival, and cellular transformation (21–24). During HSV-1 infection a virus-encoded neurovirulence factor, γ134.5, blocks the activation of TBK1 and its downstream targets, such as interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) to inhibit the type-I interferon pathway and promote viral replication (25, 26). Given the broad significance of TBK1 in the host antiviral response it is expected that blocking TBK1 activity via an inhibitor should further reduce host response and enhance infection (20, 25, 26). However, in this study, we demonstrate that BX795suppresses HSV-1 protein synthesis in various infection models, and highlights BX795 as a promising non-nucleoside alternative to current antiviral drugs against HSV-1 and potentially other viruses.

Results

BX795 suppresses HSV-1 infection in human corneal epithelial cells.

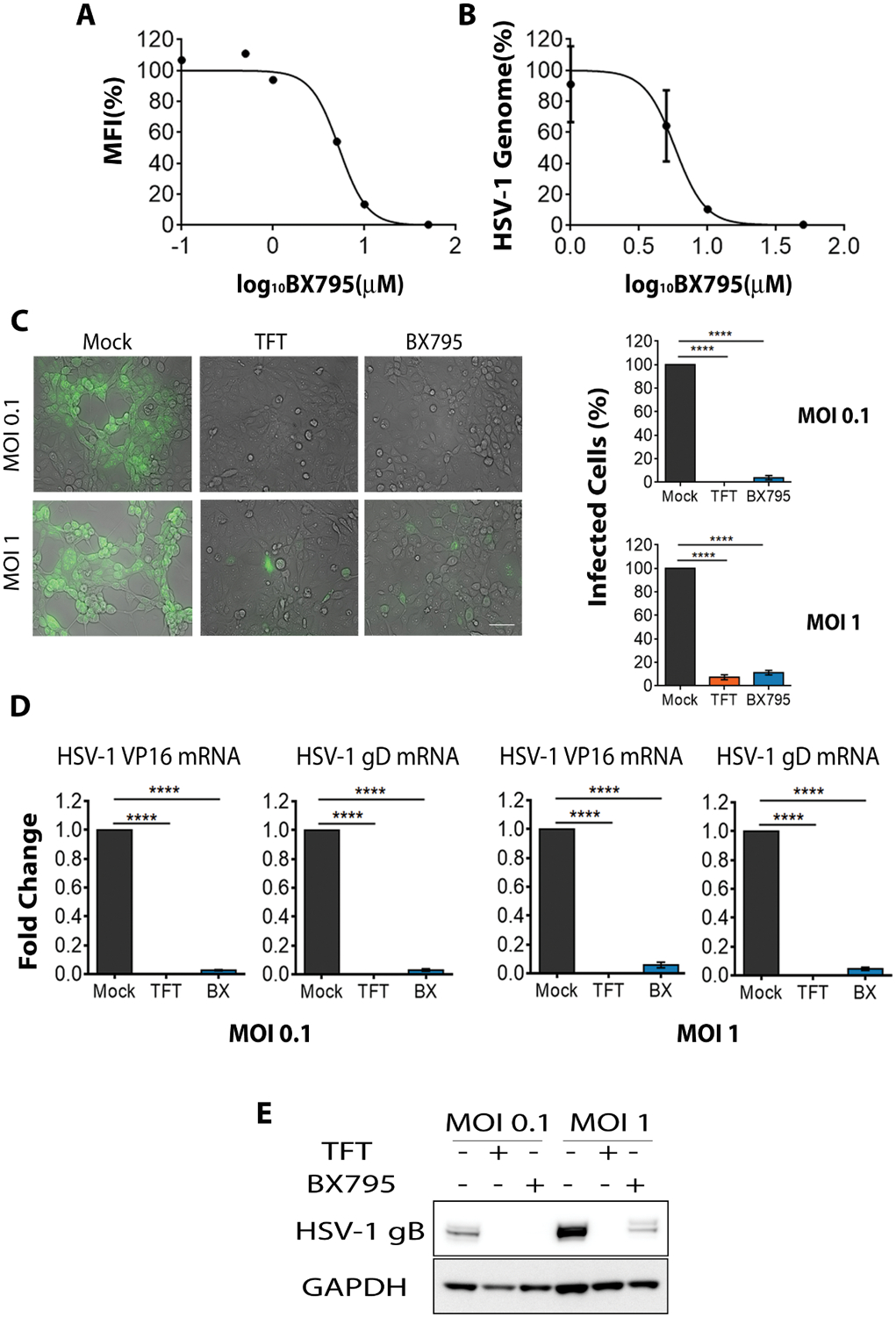

Originally we sought to inhibit the activity of TBK1 via the use of BX795 to address the importance of TBK1 and autophagy in HSV-1 infection. A human corneal epithelial (HCE) cell line was infected with HSV-1-tagged red fluorescent protein (RFP) virus (K26RFP) and treated with different concentrations of BX795 and viral yields were quantitated using flow cytometry and qPCR. To our surprise, we observed a dose-dependent inhibition of infection by BX795 (Figures 1A & 1B) and suppression of viral titers in culture supernatants (Supplementary Figure 1A). Our unexpected findings prompted us to thoroughly investigate the anti-herpetic potential of BX795. From the dose-response curves, BX795 displayed maximum antiviral activity at 10 μM and an IC50 value of 5.0 ±0.5 μM. Using two different initial viral inoculums, and TFT as a positive control, the inhibitory effect of BX795 on green fluorescent protein (GFP) tagged-HSV-1 (K26GFP) infection was monitored by additional assays, which included fluorescence microscopy (Figures 1C), qRT-PCR analysis of viral transcripts (Figure 1D), western blot analysis of a key viral protein (Figure 1E), and a viral plaque analysis to quantify secreted virions (Supplementary Figure 1B). In all cases, BX795 demonstrated inhibition of HSV-1 infection and was comparable to the antiviral activity exhibited by TFT. The unexpected antiviral effect was consistently seen even with additional cell lines of non-human origin (Supplementary Figure 1C). Collectively, we found that BX795 effectively inhibits HSV-1 infection at different viral inoculums.

Figure 1: BX795 suppresses HSV-1 infection.

(A-B) HCE cells were infected with MOI 1 HSV-1(K26RFP) with BX795 at the indicated concentrations for 2h and then fresh culture medium containing BX795 was added. Mock treatment was used as a control. Virus yields were determined at 24 hpi using flow cytometry (A, represented as percentage of mock-treated mean fluorescence intensity (MFI)) and qPCR (B, represented as percentage of mock-infected cells) (n=3 replicates). (C) Representative micrographs (left panel) of HCE cells depicting the presence of HSV-1 (green). HCEs were infected with HSV-1(K26GFP) at the indicated MOIs and 2 hpi, fresh culture medium containing mock, TFT (50 μM) or BX795 (10 μM) were added to the cells. Images were captured at 24 hpi using the Axiovision 100 under 10x objectives. Scale bar: 100 μm. The number of GFP-infected cells per field was calculated using the Metamorph imaging software (right panels, n=3 fields). The data shown are represented as percentage of mock-infected cells (). Significance to mock-treated cells was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (D) HSV-1 VP16 and gD transcripts determined by qRT-PCR. Infection was performed as mentioned in (C). Cells were collected at 24 hpi to extract RNA and viral transcripts were quantified by qRT-PCR and represented as fold-change over the mock-treated cells. Significance to mock-treated cells was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (n=4 replicates). (E) Immunoblots of HSV-1 gB protein and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) from infected HCE cells at 24 hpi. Infection was performed as mentioned in (C). Representative blots from three replicates are shown.

Next, we compared the antiviral efficacy of BX795 with that of ACV, Famciclovir, Ganciclovir, and Penciclovir. Using 10 μM as a standard concentration we found that BX795 showed a higher suppression of infection compared to most other treatments as determined by fluorescence microscopy (Supplementary Figure 2A) and flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure 2B). Our additional dose analysis experiments demonstrated that 5-fold higher concentrations of nucleoside analogs were required to achieve a similar antiviral efficacy to BX795 at 10 μM. One exception was Famciclovir, which did not reach similar efficacy even at 50 μM concentration (Supplementary Figure 2B). Interestingly, unlike nucleoside analogs, the antiviral activity of BX795 was also strong against an ACV-resistant strain, HSV-1 (KOS)tk12. This strain lacks the thymidine kinase gene and therefore, does not respond to ACV treatment (27). HCE cells that were infected with HSV-1 (KOS)tk12 and treated with BX795 showed very little expression of HSV-1 gB indicating inhibition of infection (Supplementary Figure 2C). In contrast, ACV or mock treatment did not result in a measurable loss of gB. Taken together these data suggest that BX795 treatment achieves higher efficacy at a lower dose than existing anti-herpesvirus therapies and it could be effectively used against an ACV-resistant strain as well.

Therapeutic concentration of BX795 does not cause toxicity in cells.

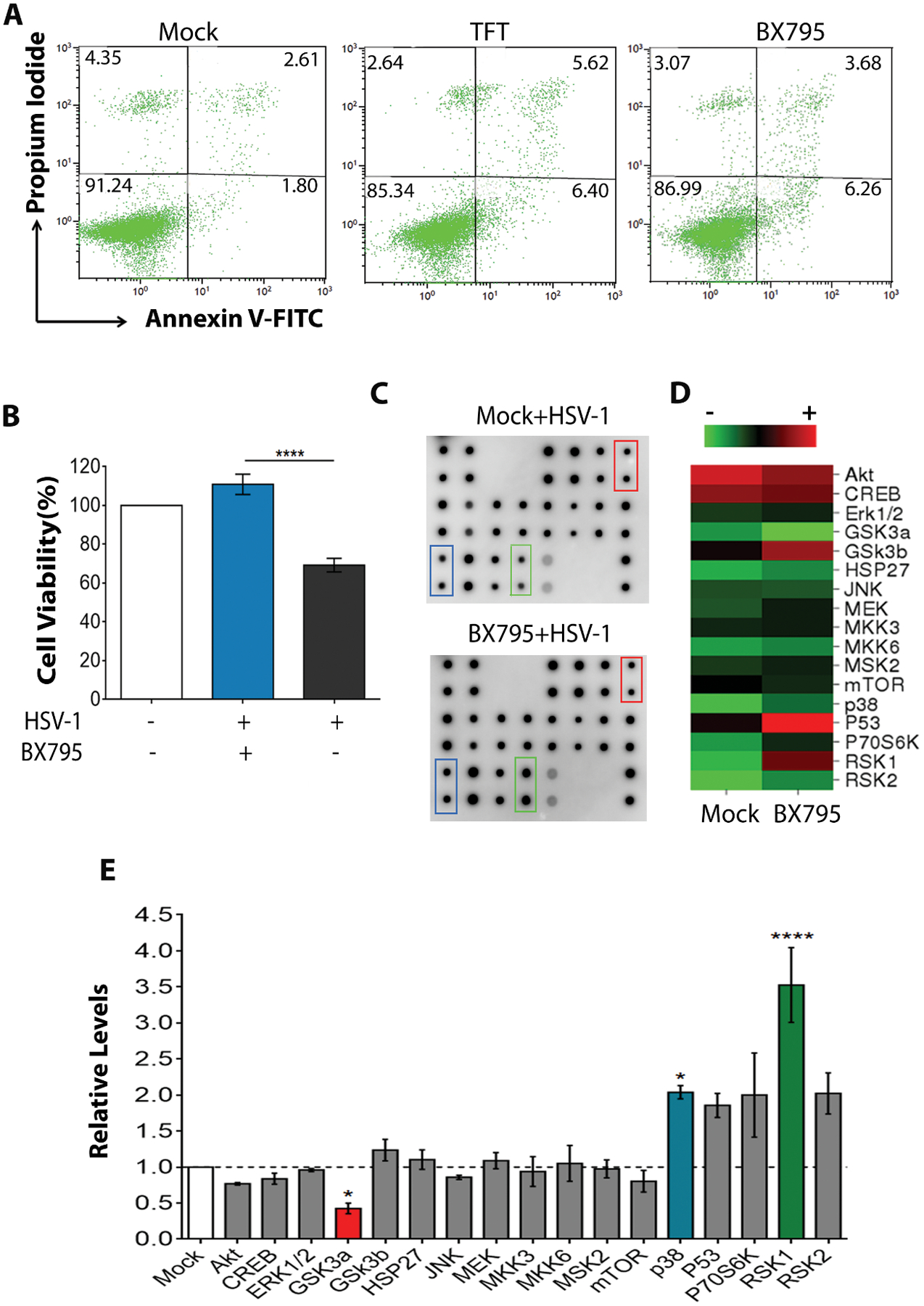

Antiviral effects of a drug should not be accompanied by any adverse toxicity issues Therefore, we tested whether BX795 treatment induces apoptosis or cell death in HCE cells. Using an Annexin V - PI apoptosis assay, we found no adverse effect of BX795 on apoptotic cell percentages (Figure 2A, numbers highlighted in bold). We also visually assessed cell morphology by bright-field imaging and tested viability with a standard cytotoxicity assay (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide, MTT). Images (Supplementary Figure 3A) and MTT assay (Supplementary Figure 3B) showed no adverse cytotoxicity at most concentrations tested, which included the proposed therapeutic concentration (10 μM) of BX795. As a control, TFT was included for cytotoxicity evaluation and we did not observe changes in apoptotic percentages of cells (Figure 2A) or viability (Supplementary Figure 3C) when HCE cells were incubated with TFT.

Figure 2: BX795 is non-toxic to HCE cells at therapeutic concentration.

(A) Apoptosis analysis (Annexin V-FITC vs Propidium Iodide) by flow cytometry. HCE cells were incubated with mock, BX795 (10 μM), or TFT (50 μM) for 24h and assayed for apoptosis using the Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit. The numbers shown in each quadrant indicate the percentage of cells. The numbers in bold in the top-right and the bottom-right quadrants indicate the percentage of early and late apoptotic cells respectively. Representative plots from three replicates are shown. (B) Cell viability of infected and treated HCE cells assessed by MTT assay. The cells were infected with MOI 0.1 HSV-1(KOS) and 2 hpi, treated with mock or BX795 (10 μM). At 24 hpi, viability was assessed by MTT assay. The data (n=9) are represented as percentage of non-treated, non-infected cells. Significance between the mock-treated and BX795-treated cells was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (C-D) Human MAPK Phosphorylation array (C) and a heat map (D) depicting the intensity of the spots on the array from HCE cell lysates. The cells were infected with MOI 5 HSV-1(KOS) and 2 hpi, fresh culture medium containing mock or BX795 (10 μM) treatments were added. At 4 hpi, the cells were collected and the lysates were assayed using the Human MAPK Phosphorylation Kit. Colored boxes indicate the spots on the array which significantly differ between the mock-treated cells and the BX795-treated cells. Duplicate spots for each sample are shown on the array. (E) Quantification of the kinases shown in (C) relative to the mock-treated cells. Colored bars indicate the kinases that are significantly different. Representative array from two replicates are shown. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was performed to determine the significance.

MTT assay revealed that the infected and BX795-treated cells were healthy and viable compared to the mock-treated cells (Figure 2B). Upon further probing, we found that most of the kinases in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, an essential pathway in cell survival (28, 29), were upregulated in the cells that were infected and treated with BX795 compared to the mock treatment (Figures 2C & 2D). Normalization of the phosphorylation levels of different kinases in the BX795-treated cells to the mock-treated cells revealed that p38 (p<0.05) and RSK1 (p<0.001) kinases were significantly upregulated whereas GSK3a (p<0.05) kinase was downregulated (Figure 2E). These results collectively indicate that BX795 treatment does not adversely affect cell survival in infected cells.

BX795 demonstrates its antiviral action by inhibiting Akt phosphorylation.

After characterizing the antiviral potential of BX795, we proceeded to identify the mechanism by which BX795 achieves its antiviral activity. It appeared to be TBK1-independent since BX795 also blocked infection in the TBK1 knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Supplementary Figure 4A). However, the antiviral activity of BX795 was stronger especially at 10 μM in the wild-type compared to the TBK1 knockout cells, which could possibly arise due to the differences in the levels of interferon production. To determine whether BX795 differentially affected the interferon production in the two cell types, we performed qRT-PCR to evaluate IFN-α and IFN-β transcripts. Although no differences in the production of transcripts were observed in the non-treated cells, a difference was seen under infection conditions where both BX795-treated wild-type as well as TBK1 knockout cells produced significantly (p<0.0001) lower amounts of IFN-α and IFN-β transcripts compared to the mock-treated cells. However, no differences were evident when BX795-treated wild-type or knockout cells were compared with each other (Supplementary Figure 4B) indicating that some unknown interferon-independent factors may contribute to the differences in the antiviral activity between the two cell types.

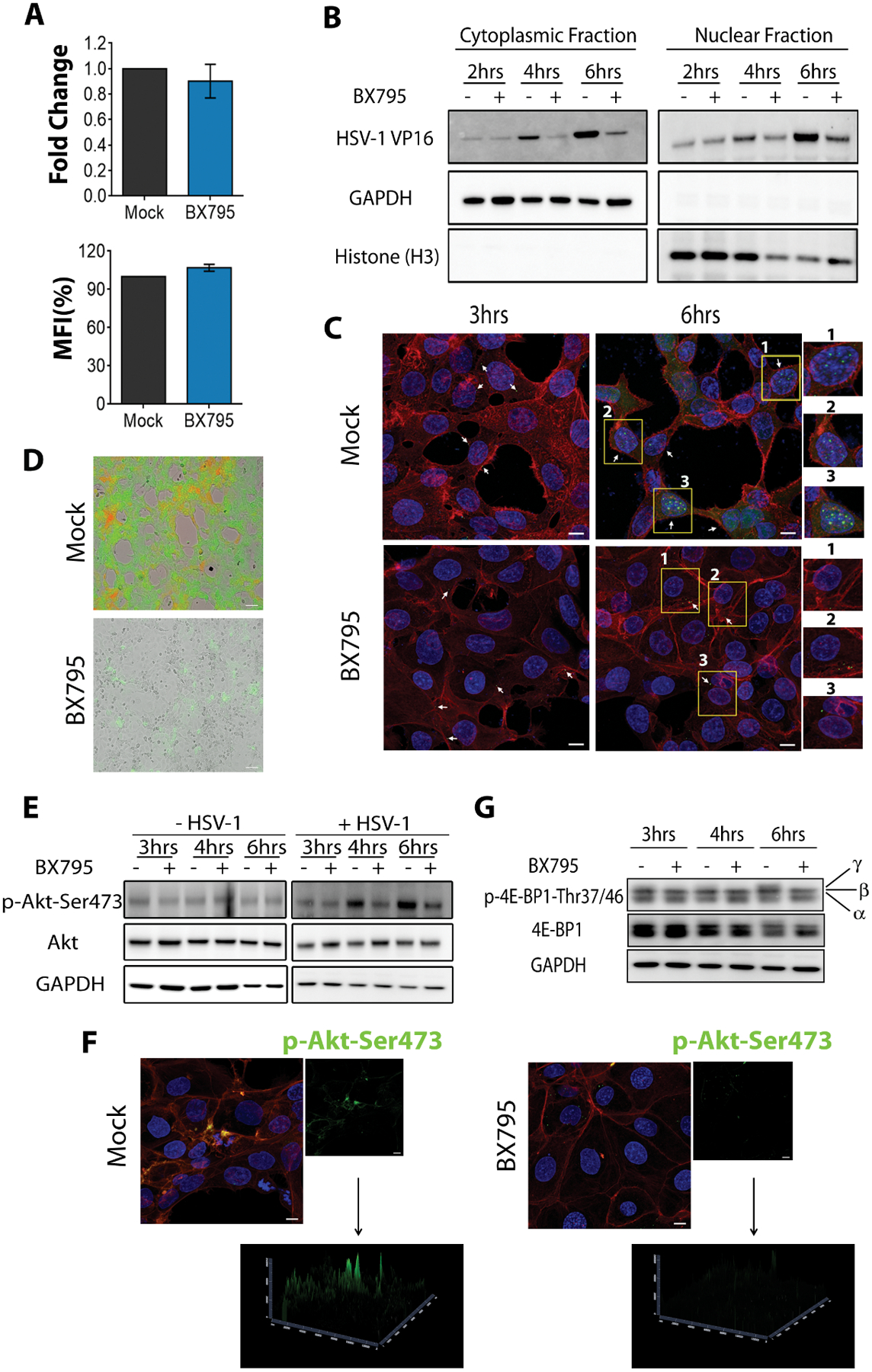

To identify the stage of HSV-1 lifecycle and the target molecule that is affected by BX795, we pursued a stepwise approach. Genome quantification of infected cells that received the treatments at the time of infection and assayed at 2 hours post-infection (hpi) revealed no differences in viral entry between the mock and BX795-treated cells (Figure 3A, left panel). Similar results were obtained when the entry of K26GFP virions was analyzed using flow cytometry (Figure 3A, right panel). Next, we focused on tegument protein delivery to the nucleus. Synthesis of HSV-1 genes intermediate early (IE), early (E) and late (L) occurs sequentially in a cascade to make new progenies. The cascade begins when the viral tegument protein VP16 drives the expression of IE genes (30–32). We, therefore, determined the expression of VP16 protein at different times post-infection in the mock and BX795-treated infected cells. At 2 hpi, the expression of VP16 protein was similar in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, suggesting that tegument protein delivery is not affected by BX795. However, as infection progressed, immunoblots of these cellular fractions revealed lower levels of VP16 expression in the BX795-treated cells (Figure 3B) raising a possibility that BX795 could be blocking viral protein synthesis. This possibility was assessed by confocal imaging where we observed similar amounts of incoming virions in the mock and BX795-treated cells at 3 hpi (Figure 3C, 3 hpi), but as infection progressed, newly generated viral capsids were observed in the mock-treated but not in the BX795-treated cells (Figure 3C, 6 hpi). In addition, we made use of a dual color HSV-1 reporter virus (KOS) pEGFP-ICP0/pRFP-gC that expresses EGFP and RFP from the viral genome. EGFP can be seen very early during infection since it is expressed through an IE gene promoter (infected cell protein 0, ICP0) whereas RFP is observed much later because it is expressed through a late gene promoter (glycoprotein C) (33). HCE cells treated with BX795 showed very little EGFP and no RFP, suggesting that viral protein synthesis stops soon after the addition of the drug (Figure 3D). In contrast, the mock-treated cells showed both EGFP and RFP expression. Taken together, the above-mentioned results strongly suggest that BX795 interferes with viral protein synthesis.

Figure 3: BX795 blocks the synthesis of HSV-1 virions.

(A) HSV-1 viral entry in the presence and absence of BX795 assessed by qPCR (left panel) and flow cytometry (right panel). HCE cells were infected with MOI 5 HSV-1(KOS). Mock or BX795 (10 μM) treatments were added along with the virus. At 2 hpi, the cells were collected and genome levels were detected by qPCR. For flow cytometry, HCE cells were infected with MOI 1000 HSV-1(K26GFP). Mock or BX795 (10 μM) treatments were added along with the virus. At 45 minutes post-infection, the cells washed and processed for flow cytometry. Data (n=3 replicates) is represented as percentage of mock-treated MFI. (B) Immunoblots of HSV-1 VP16, human GAPDH and human histone H3 in the organelle fractions of infected HCE cells. HCE cells were infected with MOI 5 HSV-1(KOS) and 15 minutes later, mock or BX795 (10 μM) treatments were added. The cells were collected at the indicated times and fractioned. The lysates were then electrophoresed to detect HSV-1 VP16, human GAPDH and human histone H3. The numbers shown below the blot are the intensities of the VP16 band relative to GAPDH in the cytoplasmic fraction and relative to H3 in the nuclear fracion. (C) Representative confocal microscopy images of infected and mock-treated or BX795-treated HCE cells indicating the presence of virus (green, white arrows) at different times post-infection. The cells were infected with MOI 5 HSV-1(K26GFP) with or without BX795 (10 μM) and at the indicated times actin (red) and the nuclei (blue) were stained and imaged under 63x objectives. Magnified images of the cells highlighted in yellow boxes and labeled with numbers, for each treatment, are shown on the right. Scale bar: 10 μm. (D) Representative images showing the presence of ICP0-GFP (green) and gC-RFP (red) HSV-1 in the mock and BX795-treated HCE cells. The cells were infected with MOI 0.1 dual-fluorescent HSV-1(KOS) after which the mock and BX795 (10 μM) treatments were added. The cells were imaged 24 hpi. Scale bar: 100 μm. (E) Immunoblots of the total and phosphorylated Akt and human GAPDH in non-infected and infected HCE cell lysates. The cells were either non-infected or infected with MOI 5 HSV-1(KOS) and at 2 hpi, fresh culture medium containing the mock or BX795 (10 μM) treatments were added to both the non-infected and the infected cells. At the indicated times, the cells were collected and the lysates were electrophoresed. The numbers shown below are the intensities of the p-Akt band relative to GAPDH. (F) Representative confocal images of phosphorylated Akt in the infected and mock- or BX795-treated HCE cells. The cells were infected as in (E) and at 6 hpi, the cells were stained for actin (red), nuclei (blue) and phosphorylated-Akt (green) and imaged under 63x objectives. Scale bar: 10 μm. (G) Immunoblots of the total and phosphorylated 4E-BP1 in infected HCE cell lysates. The cells were infected as in (E) and at the indicated times, cells were collected and the lysates were electrophoresed. α, β and γ indicate the phosphorylation status of 4E-BP1 with γ being hyper-phosphorylated. Representative blots from three replicates are shown.

Since we had evidence that synthesis of viral proteins including IE proteins was inhibited upon treatment (Figure 3D), we reasoned that BX795 could target a host molecule that is needed for the initiation of HSV-1 protein synthesis. Evidence suggests that HSV-1 induces protein kinase B (PKB) or Akt to manipulate host cell function (34–36)and that HSV-1 Us3 kinase is an Akt mimetic that activates mTORC1 to stimulate viral protein synthesis (37, 38). On this basis, we decided to pursue Akt as a host molecular target for BX795. This possibility was further supported by our observation that blocking Akt activity using an Akt inhibitor (AZD5363) resulted in the loss of VP16 protein expression (Supplementary Figure 4C). To understand this further, the phosphorylation status of Akt was monitored at different times post-infection. We observed that BX795 treatment blocked the phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 (pSer473) only in the infected cells but, for reasons unclear, it did not have an impact on the non-infected cells (Figure 3E). We performed immunofluorescence imaging that confirmed our immunoblot findings that little or no p-Akt-Ser473 was found in cells infected and treated with BX795 (Figure 3F). Additionally, we performed a time course study to determine the phosphorylation status of the downstream effector of Akt involved in protein synthesis: eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF) 4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1). It is known that 4E-BP1 is hyperphosphorylated upon HSV-1 infection and then degraded causing uninterrupted protein synthesis and thus allowing generation of more virions (34, 37, 39). In the mock-treated cells, HSV-1 infection induced hyperphosphorylation (γ band) of 4E-BP1 over time whereas in cells treated with BX795 these bands were not observed (Figure 3G). This indicates that blocking Akt activity via BX795 prevents the hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP1 thus resulting in little to no new virions.

Because BX795 and the existing antivirals work on two separate targets to block HSV-1 infection, we next tested the synergistic ability of BX795 and TFT to block infection. We first evaluated the toxicity of the drug combination on HCE cells. MTT assay on HCE cells incubated with the drugs showed no toxicity at 60 μM or lower concentrations (Supplementary Figure 4D). Next, the synergism of the drugs to block HSV-1 infection was tested by monitoring GFP levels from HSV-1 tagged GFP virus using flow cytometry. We observed a dose-response relationship when the cells were infected and treated with TFT. Interestingly, when BX795 and TFT were given together as a cocktail at concentrations lower than their individual most effective concentrations (10 μM and 50 μM respectively) we saw a lower inhibition of infection except at the highest concentrations of BX795 and TFT, but little to no synergy was evident (Supplementary Figure 4E).

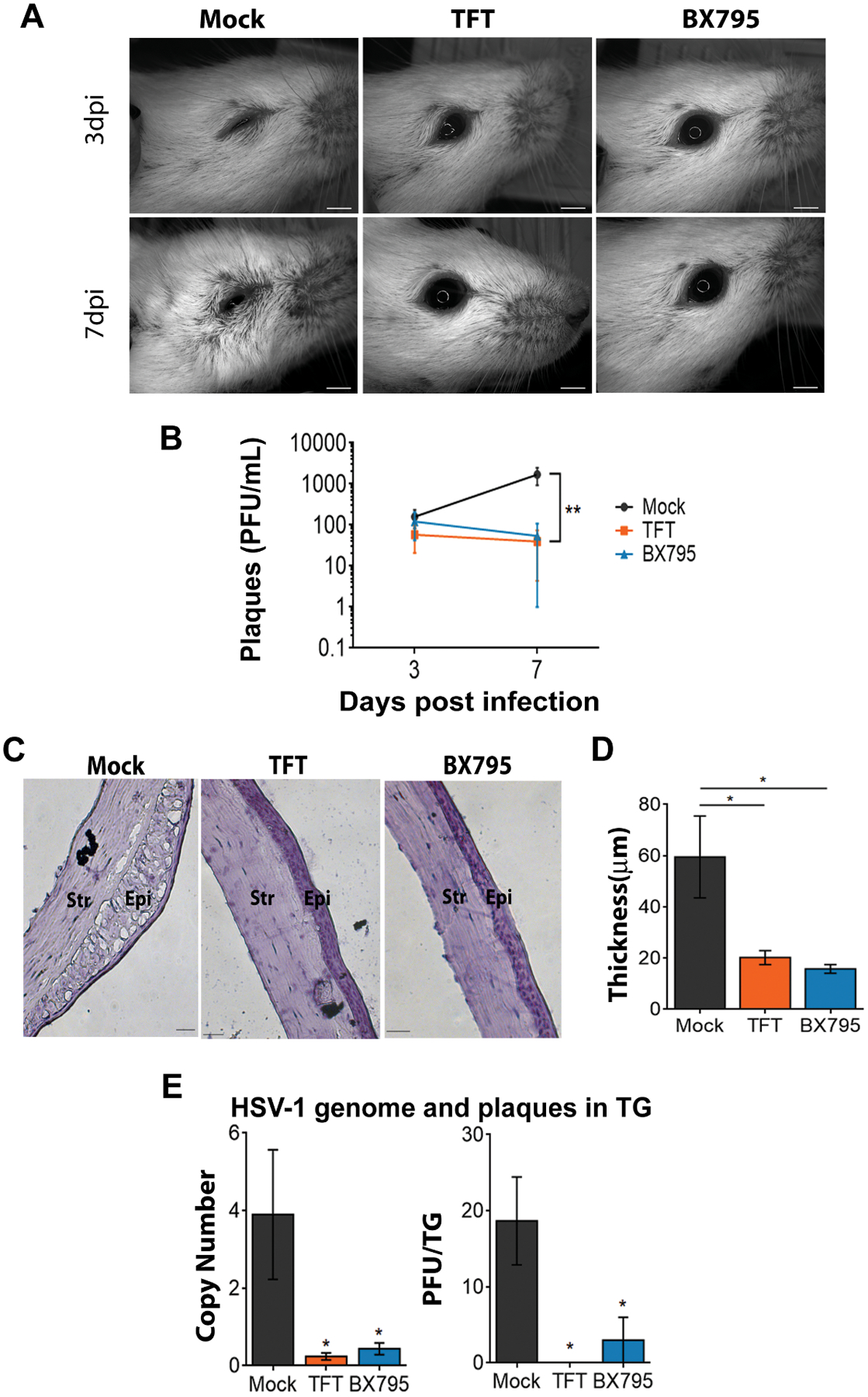

Topical application of BX795 suppresses corneal HSV-1 infection in a mouse model.

Having established the antiviral effects of BX795 in vitro, we then sought to investigate the effect of BX795 as a potential topical antiviral against HSV-1 infection in vivo. We compared the antiviral potency of BX795 to mock treatment (DMSO) and TFT, the only topically administered drug currently prescribed to treat ocular herpes infection. BX795 was used at its therapeutic concentration - 10 μM and TFT at its clinically prescribed dose - 1% solution (~34mM) (6). To determine infectivity, we visually assessed the infected eye of all the treated mice. The mock-treated eye showed signs of ocular infection at day 3 post-infection and the symptoms worsened by day 7 (Figure 4A). In contrast, the BX795 and TFT-treated eyes were healthy (Figure 4A). To rule out the possibility that topical application of the treatments was causing distress to the eye, the left eyes of these mice, which received the topical treatments but no virus, were imaged. We did not observe any visible signs of infection or ocular distress confirming that the treatments did not impart any toxicity to the eyes (Supplementary Figure 5A). We assayed the secreted virus titers from the tears at two different days post-infection (dpi). Both BX795 and TFT treatments significantly (p<0.01) reduced the viral titers present in the eye (Figure 4B). We also performed histological staining to examine the pathology of the eye. The mock-treated tissues presented with loss of cells in the corneal epithelium and epithelial thickening typical of acute infection (Figure 4C, 4D). After active infection in the eye, HSV-1 travels to the trigeminal ganglia (TG) where it establishes latency after primary infection. To assess whether BX795 treatment blocked the transmission of HSV-1 to the TG, TGs from the infected mice were harvested and assayed to evaluate the number of HSV-1 genomes and viral titers. The BX795 and TFT-treated mice had significantly (p<0.05) fewer HSV-1 genomes (Figure 4E, left panel) and titers (Figure 4E, right panel) present in the TG compared to the mock-treated mice indicating that the treatments block the transmission of the virus to the TG from the active site of infection. Survival curves were generated for each treatment group to assess the effect of the treatments. A significant (p<0.05) difference was observed in the number of survivors between the BX795 and mock-treated mice (Figure 5A). Loss of corneal sensation has been implicated as an important pathology associated with ocular HSV-1 infection (40, 41), so we assessed corneal sensitivity by recording esthesiometer scores at two different dpi, where higher scores indicate a loss in corneal sensitivity. The BX795-treated mice showed significantly (p<0.05) less or no loss of sensation compared to the mock-treated mice (Figure 5B). The TFT-treated mice also showed better corneal sensitivity compared to the mock-treated mice (Figure 5B). Clinical signs of acute ocular herpes infection were also monitored and scored in a blinded fashion. Mice that were treated with BX795 had significantly (p<0.05) lower disease scores compared to the mock–treated mice at days 3, 4 and 7 dpi (Figure 5C). The TFT-treated mice also presented fewer symptoms compared to the mock treatment but the symptoms were marginally pronounced compared to the BX795 treatment (Figure 5C). The disease scores were further analyzed to observe whether the effect of treatments was influenced by the gender of the mice. No significant gender differences were observed among the treatments although cumulative disease scores at 7 dpi indicate that around 56% males and 44% females presented eye disease symptoms in mock and TFT-treated mice respectively whereas equal numbers of male and female mice presented eye disease symptoms with BX795 treatment. Finally, body weights were recorded at different dpi. Among the female mice, the BX795 and TFT-treated mice did not show significant loss of weights compared to the mock-treated mice (Figure 5D, left panel). However, among the male mice, only at 7 dpi, we observed a significant loss (p<0.05) of body weight in the mock-treated compared to the BX795-treated mice over time (Figure 5D, right panel). Collectively, data from these experiments indicate that compared to the mock-treated mice, the BX795-treated mice were healthier and resist infection. In addition, the health of the BX795-treated mice was equal or marginally better compared to the TFT-treated mice although the drugs were used at different concentrations.

Figure 4: BX795 suppresses HSV-1 corneal infection in vivo.

BALB/c mice were infected on the right eye with 106 PFU HSV-1(McKrae) and 24 hpi, mock, TFT (50 μM), or BX795 (10 μM) were topically added to the eyes. (A) Representative micrographs of right eyes from infected and treated mice. Scale bar: 2mm. (B) Secreted virus titers assessed from the swabs of right eyes (n=7 per treatment group). Significance between the mock-treated mice and the TFT/BX795-treated mice were determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Representative corneal histology sections taken from the right eye at 9 dpi. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Thickness of the corneal epithelium assessed from histology. Data was obtained from the mice (n=3 per treatment group) in (C). Significance between the mock-treated mice and the TFT/BX795-treated mice were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (E) HSV-1 genomes and titers in the trigeminal ganglia (TG) assessed by qPCR and plaques assays respectively at 9dpi. Mice (n=3 per treatment group) were euthanized to extract the TGs. Homogenized TG lysates were used for qPCR to detect HSV-1 genomes (left panel) and were also used to titer HSV-1 (right panel) on Vero cells. Significance between the mock-treated mice and the TFT- and BX795-treated mice were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test.

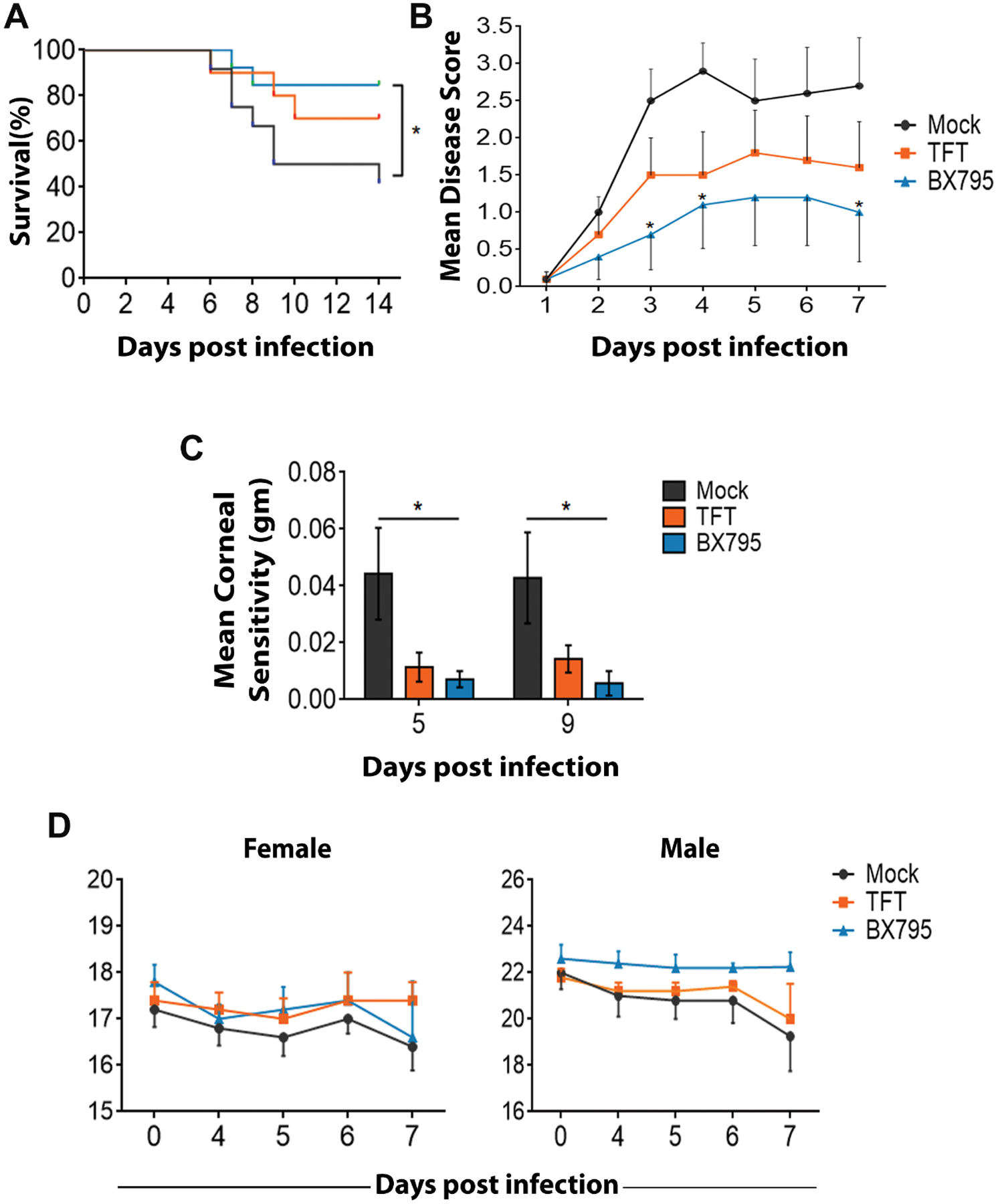

Figure 5: BX795 suppresses HSV-1 associated corneal disease pathologies.

The right eyes of BALB/c mice were infected with 106 PFU HSV-1(McKrae) and at 24 hpi, mock (n=12), 1% TFT (n=10) and 10 μM BX795 (n=13) were added topically to both the eyes. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Significance between the mock-treated and the BX795-treated mice was calculated by log-rank test followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test. (B) Corneal sensitivity measured using an electronic Von-Frey Esthesiometer scores in mice (n=7 per treatment group)..Higher scores indicate loss in corneal sensitivity. Significance between the mock-treated and TFT/BX795-treated mice was determined by two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Ocular disease scores (0–5, 5 being severe) in mice (n=10 per treatment group). Significance between the mock-treated and the BX975-treated mice was determined by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. (D) Body weights (n=10 per treatment group) for the female (left panel) and the male mice (right panel) were recorded. Significance between the mock-treated and BX795-treated mice was determined by two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test.

BX795 blocks HSV-1 infection in human primary cells and ex vivo human and porcine corneas.

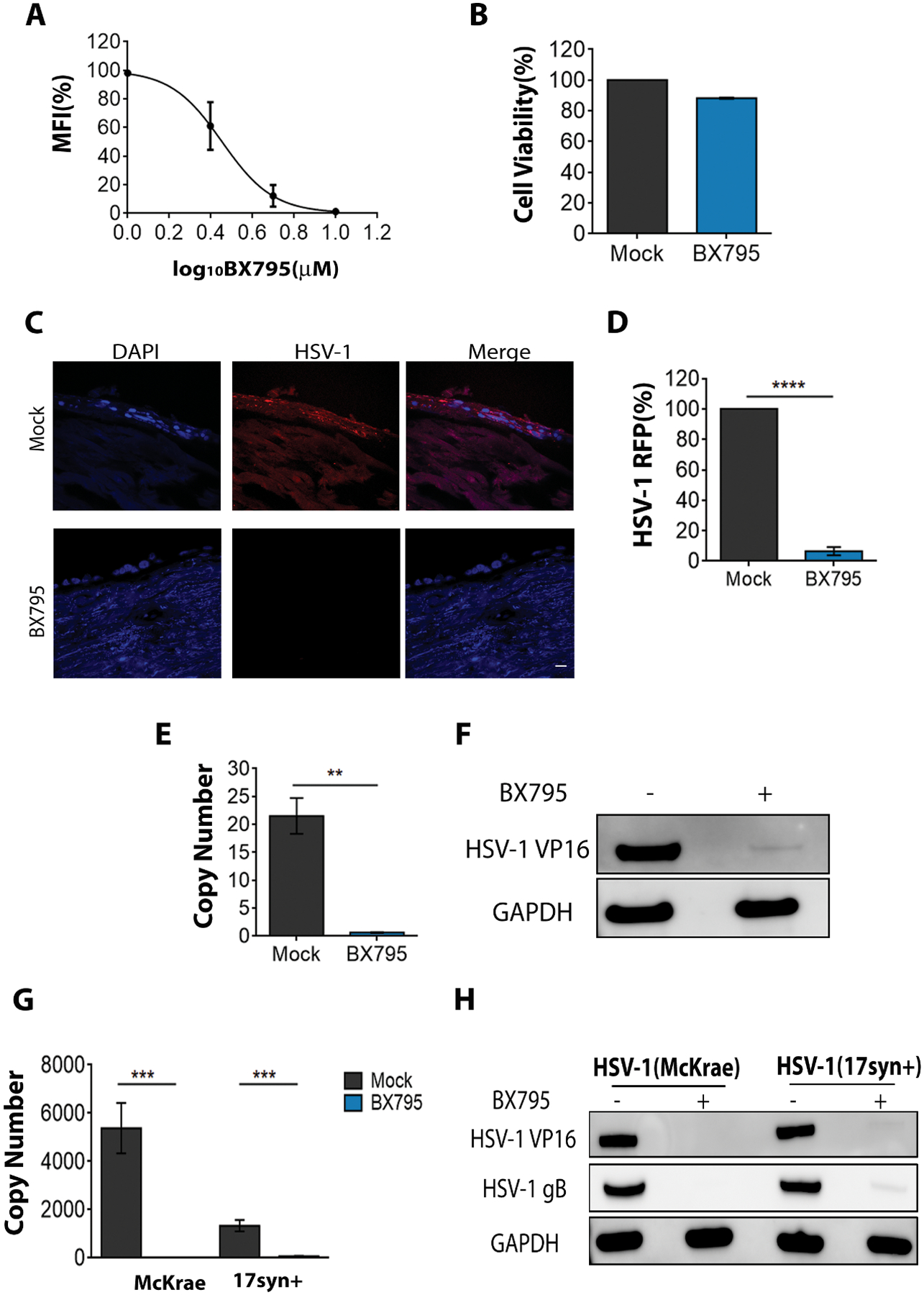

Finally, we investigated the antiviral potential of BX795 in primary human corneal cells and human cornea buttons, which were obtained from tissue banks. The results were consistent with our earlier in vitro results, (Figure 6A). Two interesting observations were noted: (i) BX795 at 5 μM also showed significant antiviral activity and (ii) the IC50 from the dose-response curve was estimated to be ~2.8 μM which is lower than the IC50 we observed in HCE cell lines. Additionally, BX795 did not adversely affect the viability of primary cells at its therapeutic concentration (Figure 6B). We then transitioned to organ cultures of the human corneas. A single human cornea was divided into two halves and each half was infected and treated with either mock or BX795. Immunofluorescence imaging with the tissue sections at 48 hpi revealed that BX795-treated corneal sections significantly suppressed infection compared to the mock-treated sections (Figures 6C & 6D). In parallel, to account for human variability and the possibility that a drug may show varied efficacy in different individuals, random groups of corneas were infected and treated. Infection was assessed by determining the viral genome and viral protein levels. In concurrence with our previous results, the corneas treated with BX795 showed loss of infection (Figures 6E & 6F). Providing additional support, similar antiviral effects of BX795 were seen against two other highly pathogenic strains of HSV-1 (Figures 6G & 6H). In parallel, we also used a porcine cornea culture model to determine the antiviral activity of BX795 (42–44). Consistent with our findings, BX795 treatment blocked HSV-1 infection in porcine corneas as seen from representative immunofluorescence images (Supplementary Figure 5B), immunoblot and HSV-1 protein levels (Supplementary Figures 5C & 5D). These data further elucidate the promise of BX795 as a therapeutic agent against HSV-1 infection in diverse models of infection.

Figure 6: BX795 blocks HSV-1 infection in primary HCE cells and organ cultures of the human cornea.

(A) Primary HCE cells were infected with MOI 0.1 HSV-1(K26GFP) and at 2 hpi, fresh culture medium containing various concentrations of BX795 were added. At 24 hpi, the amount of GFP present in the cells was quantified by flow cytometry. Individual data points from two replicates are shown and are represented as percentage of mock-related MFI. (B) Cell viability of primary HCE cells assessed by MTT assay (n=8 replicates). Primary HCE cells were incubated with mock or BX795 (10 μM) for 24h and cell viability was assessed. (C) Representative confocal images of human corneal tissue sections depicting the presence of virus (red) in the corneal epithelium cells (blue). Human corneas were infected with 107 PFU HSV-1 (K26RFP). One-half of the corneal tissue was treated with mock and the other half treated with BX795 (10 μM). At 48 hpi, the tissues were frozen, sectioned and stained. Images were captured under 63x objectives. Scale bar: 10 μm. (D) Percentage of fluorescent (RFP) virus present in (C) (n=10 corneal sections) via Metamorph imaging software and is represented as percentage of mock-treated tissues. Significance was determined by t-test (two-tailed). (E-F) HSV-1 genome and VP16 protein levels assessed by qPCR (E) and immunoblotting (F) respectively. Human corneas (n=3) were infected as in (C) and at 48 hpi, the corneal epithelium was isolated and used to detect genomes by qPCR or used to detect VP16 protein by immunoblotting. Significance was determined by t-test (two-tailed). (G-H) HSV-1 genome and protein levels assessed by qPCR (G) and immunoblotting (H) respectively. Human corneas (n=3) were infected with 106 PFU of virulent HSV-1(McKrae and 17syn+) and at 48 hpi, the corneal epithelium was isolated and used to detect genomes by qPCR or used to detect VP16 protein by immunoblotting. Significance was determined by t-test (two-tailed).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated the antiviral activity of a kinase inhibitor, BX795, in inhibiting HSV-1 infection. Using several different infection models, we observed that BX795 was highly effective in reducing HSV-1 infection and the levels of antiviral activity were similar to TFT, a currently prescribed topical antiviral for ocular herpes. At its therapeutic concentration, we show that BX795 does not induce any adverse toxicity to cells. The role of p38 in cell survival is well-documented and evidence suggests that inhibiting Akt allows p38 to promote cell survival (45, 46), which may be the case in our study as we show that BX795 blocks Akt activity. RSK1 also regulates cell survival (47) and downregulates the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 R1 (48). ICP0, encoded in the HSV-1 genome, is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that requires the E2 enzyme to perform various roles in HSV-1 infection including the efficient establishment of infection (49). It is thus possible that upregulation of RSK1 with BX795 treatment results in the downregulation of E2 activity that prevents ICP0 from performing the necessary proviral activities. GSK3a was the only kinase downregulated upon BX795 treatment which is consistent with previous findings that inhibiting GSK3a activity results in a pro-survival signaling (50, 51). In addition, mice that received topical BX795 treatment in the eye showed no adverse effects or detectable toxicity.

We show that BX795 targets Akt to block viral protein synthesis. Akt can regulate protein synthesis by controlling the activity of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and its downstream effectors 4E-BP1 and S6K (52–55). HSV-1 is known to activate the Akt pathway to manipulate protein synthesis in addition to aiding in viral entry, replication, and reactivation (56, 57). We provide evidence that BX795 reduces phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and prevents hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP1 in infected cells thus blocking viral protein synthesis. BX795 is an inhibitor of TBK1 and can also inhibit 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) (20). Both these kinases are known to phosphorylate Akt (58). During the time our work was in progress, a published study demonstrated anti-HSV activity of BX795 and found it to be independent of TBK1 and PDK1 (59) and we also found in this study that BX795 can function independent of TBK1. Thus, whether BX795 affects Akt directly or indirectly is unclear.

Despite having a unique mode of antiviral action, it was evident that BX795 and TFT together do not show synergism. This finding was surprising since both the drugs act on two separate targets and was expected to show synergism. An explanation for lack of synergism includes the possibility that the action of both BX795 and TFT depends heavily on a threshold concentration. A minimum overall concentration of BX795 may be needed before it demonstrates its lower affinity off-target antiviral effect. Nevertheless, BX795 may have attributes of a broad-spectrum antiviral since many other viruses are known to subvert the host protein synthesis machinery via Akt (60, 61). Since it targets a host molecule, any long-term toxicity associated with BX795 treatment remains unclear. Likewise, systemic delivery of BX795 was not tested, and it is likely to have its own benefits and limitations.

In conclusion, our study characterizes the antiviral activity of BX795. It reduces infection via a mechanism that is distinct from the conventional antivirals currently available against HSV-1. BX795 could represent an emerging class of small molecule antiviral compounds which may potentially act against multiple human viruses that use Akt for their pathogenesis (60, 61). It is thus worthy of further investigation and future development as an effective inhibitor of infection and potentially a broad-spectrum antiviral drug.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The objective of this study was to characterize the unexpected antiviral activity of a small molecule kinase inhibitor BX795. The antiviral activity and drug toxicity were determined and confirmed in vitro using human corneal epithelial (HCE) cells that are natural target cells for HSV-1 infection. BX795 was further compared to existing front-line antiherpetic treatments to demonstrate its efficacy and its potential synergism with trifluridine (TFT) was also evaluated. The mechanism of antiviral action was assessed by a step-wise approach using flow cytometry, immunofluorescence and immunoblotting in non-infected and infected cells. The antiviral activity of BX795 was compared to TFT in the mouse models of corneal HSV-1 infection by topically administering the drugs and monitoring the infection and associated pathologies. Finally, using porcine and human cornea organ cultures, the antiviral activity of BX795 was assessed to highlight the BX795’s promise as a lead compound for future translational research. The animals and ex vivo corneas were randomly assigned to the treatment groups. Ocular disease scoring and sample analysis was conducted in a blinded fashion. Primary data are located in table S1.

Statistical Analysis:

The data shown in figures are means ± standard error of means (SEM). The statistical tests were performed on GraphPad Prism version 6.01 (GraphPad Software) and are described in each figure legend. Dose-response curves were also generated using GraphPad Prism. Asterisks indicate significant difference: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: BX795 blocks virus secretion and shows antiviral activity in other cell types.

Supplementary Figure 2: BX795 shows higher potency compared to existing antivirals.

Supplementary Figure 3: Therapeutic concentration of BX795 is non-toxic in HCE cells.

Supplementary Figure 4: BX795 does not mediate antiviral activity through TBK1.

Supplementary Figure 5: Antiviral activity of BX795 in the in vivo and ex vivo models of corneal infection.

Supplementary Figure 6: Uncropped blots for figures.

Supplementary Figure 7: Uncropped blots for supplementary figures.

Table S1. Primary data

Acknowledgements:

We thank Dr. Ali Djalilian (UIC) for help with obtaining the human corneas and primary HCE cells Dr. Balaji Ganesh and Dr. Suresh Ramasamy (Flow Cytometry Services, UIC) for helping us with acquiring and analyzing the apoptosis data and Dr. Paul R. Kinchington (University of Pittsburgh) for providing the dual fluorescent virus.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the National Eye Institute (R01 EY024710) to DS

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors claim no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Roizman B, Knipe DM, Whitley RJ, Herpes simplex viruses Fields Virology. 5th Edition Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD, USA, 2503–2602 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaishankar D, Shukla D, Genital Herpes: Insights into Sexually Transmitted Infectious Disease. Microb. Cell 3, 438–450 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitley RJ, Roizman B, Herpes simplex virus infections. Lancet. 357, 1513–1518 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farooq AV, Shukla D, Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv. Ophthalmol 57, 448–462 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel A, Cholkar K, Agrahari V, Mitra AK, Ocular drug delivery systems: An overview. World J. Pharmacol 2, 47–64 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsatsos M, MacGregor C, Athanasiadis I, Moschos MM, Hossain P, Anderson D, Herpes simplex virus keratitis: an update of the pathogenesis and current treatment with oral and topical antiviral agents. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol 44, 824–837 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordheim LP, Durantel D, Zoulim F, Dumontet C, Advances in the development of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues for cancer and viral diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 12, 447–464 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lass JH, Langston RH, Foster CS, Pavan-Langston D, Antiviral medications and corneal wound healing. Antiviral Res. 4, 143–157 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chilukuri S, Rosen T, Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol. Clin 21, 311–320 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimberlin D. W. a. W. R.J., in Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis(Cambridge University Press; 2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yakoub AM, Shukla D, Autophagy stimulation abrogates herpes simplex virus-1 infection. Sci. Rep 5, 9730 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang Y, Feng H, Lin Y, Guo X, New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 8, 1–6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maudgal PC, Van Damme B, Missotten L, Corneal epithelial dysplasia after trifluridine use. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol 220, 6–12 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Udell IJ, Trifluridine-associated conjunctival cicatrization. Am. J. Ophthalmol 99, 363–364 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayamanne DGR, Vize C, Ellerton CR, Morgan SJ, Gillie RF, Severe reversible ocular anterior segment ischaemia following topical trifluorothymidine (F3T) treatment for herpes simplex keratouveitis. Eye 11, 757–759 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spiegal DM, Lau K, Acute renal failure and coma secondary to acyclovir therapy. JAMA. 255, 1882–1883 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleischer R, Johnson M, Acyclovir nephrotoxicity: a case report highlighting the importance of prevention, detection, and treatment of acyclovir-induced nephropathy. Case Rep. Med 2010, 10.1155/2010/602783. Epub 2010 Aug 31 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yildiz C, Ozsurekci Y, Gucer S, Cengiz AB, Topaloglu R, Acute kidney injury due to acyclovir. CEN Case Rep. 2, 38–40 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clive D, Turner NT, Hozier J, Batson AG, Tucker WE Jr, Preclinical toxicology studies with acyclovir: genetic toxicity tests. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol 3, 587–602 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark K, Plater L, Peggie M, Cohen P, Use of the Pharmacological Inhibitor BX795 to Study the Regulation and Physiological Roles of TBK1 and IkB Kinase ε: A DISTINCT UPSTREAM KINASE MEDIATES SER-172 PHOSPHORYLATION AND ACTIVATION. J. Biol. Chem 284, 14136–14146 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helgason E, Phung QT, Dueber EC, Recent insights into the complexity of Tank-binding kinase 1 signaling networks: the emerging role of cellular localization in the activation and substrate specificity of TBK1. FEBS Lett. 587, 1230–1237 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delhase M, Kim S, Lee H, Naiki-Ito A, Chen Y, Ahn E, Murata K, Kim S, Lautsch N, Kobayashi KS, Shirai T, Karin M, Nakanishi M, TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) controls cell survival through PAI-2/serpinB2 and transglutaminase 2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109, E177–E186 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad L, Zhang S, Casanova J, Sancho-Shimizu V, Human TBK1: A Gatekeeper of Neuroinflammation. Trends Mol. Med 22, 511–527 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumoto G, Shimogori T, Hattori N, Nukina N, TBK1 controls autophagosomal engulfment of polyubiquitinated mitochondria through p62/SQSTM1 phosphorylation. Hum. Mol. Genet 24, 4429–4442 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verpooten D, Ma Y, Hou S, Yan Z, He B, Control of TANK-binding Kinase 1-mediated Signaling by the g(1)34.5 Protein of Herpes Simplex Virus 1. J. Biol. Chem 284, 1097–1105 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma Y, Jin H, Valyi-Nagy T, Cao Y, Yan Z, He B, Inhibition of TANK Binding Kinase 1 by Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Facilitates Productive Infection. J. Virol 86, 2188–2196 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frobert E, Ooka T, Cortay JC, Lina B, Thouvenot D, Morfin F, Herpes Simplex Virus Thymidine Kinase Mutations Associated with Resistance to Acyclovir: a Site-Directed Mutagenesis Study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 49, 1055–1059 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W, Liu HT, MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell Res. 12, 9–18 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cargnello M, Roux PP, Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 75, 50–83 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honess RW, Roizman B, Regulation of herpesvirus macromolecular synthesis: sequential transition of polypeptide synthesis requires functional viral polypeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 72, 1276–1280 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batterson W, Roizman B, Characterization of the herpes simplex virion-associated factor responsible for the induction of alpha genes. J. Virol 46, 371–377 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harkness JM, Kader M, DeLuca NA, Transcription of the Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Genome during Productive and Quiescent Infection of Neuronal and Nonneuronal Cells. J. Virol 88, 6847–6861 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Aiuto L, Prasad KM, Upton CH, Viggiano L, Milosevic J, Raimondi G, McClain L, Chowdari K, Tischfield J, Sheldon M, Moore JC, Yolken RH, Kinchington PR, Nimgaonkar VL, Persistent Infection by HSV-1 Is Associated With Changes in Functional Architecture of iPSC-Derived Neurons and Brain Activation Patterns Underlying Working Memory Performance. Schizophr. Bull 41, 123–132 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walsh D, Mohr I, Phosphorylation of eIF4E by Mnk-1 enhances HSV-1 translation and replication in quiescent cells. Genes Dev. 18, 660–672 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benetti L, Roizman B, Protein Kinase B/Akt Is Present in Activated Form throughout the Entire Replicative Cycle of ΔUS3 Mutant Virus but Only at Early Times after Infection with Wild-Type Herpes Simplex Virus 1. Journal of Virology. 80, 3341–3348 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diehl N, Schaal H, Make Yourself at Home: Viral Hijacking of the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Viruses. 5, 3192–3212 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chuluunbaatar U, Roller R, Feldman ME, Brown S, Shokat KM, Mohr I, Constitutive mTORC1 activation by a herpesvirus Akt surrogate stimulates mRNA translation and viral replication. Genes Dev. 24, 2627–2639 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chuluunbaatar U, Mohr I, A herpesvirus kinase that masquerades as Akt: You don’t have to look like Akt, to act like it. Cell. Cycle 10, 2064–2068 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elia A, Constantinou C, Clemens MJ, Effects of protein phosphorylation on ubiquitination and stability of the translational inhibitor protein 4E-BP1. Oncogene. 27, 811–822 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamrah P, Cruzat A, Dastjerdi MH, Zheng L, Shahatit BM, Bayhan HA, Dana R, Pavan-Langston D, Corneal sensation and subbasal nerve alterations in patients with herpes simplex keratitis: an in vivo confocal microscopy study. Ophthalmology. 117, 1930–1936 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chucair-Elliott AJ, Jinkins J, Carr MM, Carr DJ, IL-6 Contributes to Corneal Nerve Degeneration after Herpes Simplex Virus Type I Infection. Am. J. Pathol 186, 2665–2678 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duggal N, Jaishankar D, Yadavalli T, Hadigal S, Mishra YK, Adelung R, Shukla D, Zinc oxide tetrapods inhibit herpes simplex virus infection of cultured corneas. Mol. Vis 23, 26–38 (2017). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thakkar N, Jaishankar D, Agelidis A, Yadavalli T, Mangano K, Patel S, Tekin SZ, Shukla D, Cultured corneas show dendritic spread and restrict herpes simplex virus infection that is not observed with cultured corneal cells. Sci. Rep 7, 42559 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jaishankar D, Buhrman JS, Valyi-Nagy T, Gemeinhart RA, Shukla D, Extended Release of an Anti-Heparan Sulfate Peptide From a Contact Lens Suppresses Corneal Herpes Simplex Virus-1 Infection. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 57, 169–180 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutierrez-Uzquiza A, Arechederra M, Bragado P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Porras A, p38a Mediates Cell Survival in Response to Oxidative Stress via Induction of Antioxidant Genes: EFFECT ON THE p70S6K PATHWAY. J. Biol. Chem 287, 2632–2642 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phong MS, Horn RDV, Li S, Tucker-Kellogg G, Surana U, Ye XS, p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Promotes Cell Survival in Response to DNA Damage but Is Not Required for the G2 DNA Damage Checkpoint in Human Cancer Cells. Mol. Cell. Biol 30, 3816–3826 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimamura A, Ballif BA, Richards SA, Blenis J, Rsk1 mediates a MEK-MAP kinase cell survival signal. Current Biology. 10, 127–135 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katayama K, Fujiwara C, Noguchi K, Sugimoto Y, RSK1 protects P-glycoprotein/ABCB1 against ubiquitin–proteasomal degradation by downregulating the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 R1. Open. 6, srep36134 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abadal E, HSV-1 ICP0: An E3 Ubiquitin Ligase That Counteracts Host Intrinsic and Innate Immunity (Ledizioni, Milano, 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marchand B, Arsenault D, Raymond-Fleury A, Boisvert F, Boucher M, Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) inhibition induces prosurvival autophagic signals in human pancreatic cancer cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 290, 5592 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fang X, Yu SX, Lu Y, Bast RC, Woodgett JR, Mills GB, Phosphorylation and Inactivation of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 by Protein Kinase A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 97, 11960–11965 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richter JD, Sonenberg N, Regulation of cap-dependent translation by eIF4E inhibitory proteins. Nature. 433, 477–480 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruggero D, Sonenberg N, The Akt of translational control. Oncogene. 24, 7426–7434 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, Proud CG, The mTOR pathway in the control of protein synthesis. Physiology (Bethesda). 21, 362–369 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma XM, Blenis J, Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 10, 307–318 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tiwari V, Shukla D, Phosphoinositide 3 kinase signalling may affect multiple steps during herpes simplex virus type-1 entry. J. Gen. Virol 91, 3002–3009 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu X, Cohen JI, The role of PI3K/Akt in human herpesvirus infection: From the bench to the bedside. Virology. 479–480, 568–577 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xie X, Zhang D, Zhao B, Lu M, You M, Condorelli G, Wang C, Guan K, IkB kinase e and TANK-binding kinase 1 activate AKT by direct phosphorylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108, 6474–6479 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Su AR, Qiu M, Li YL, Xu WT, Song SW, Wang XH, Song HY, Zheng N, Wu ZW, BX-795 inhibits HSV-1 and HSV-2 replication by blocking the JNK/p38 pathways without interfering with PDK1 activity in host cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin 38, 402–414 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walsh D, Mohr I, Viral subversion of the host protein synthesis machinery. Nat Rev Micro 9, 860–875 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dunn EF, Connor JH, HijAkt: The PI3K/Akt pathway in virus replication and pathogenesis. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci 106, 223–250 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gidfar S, Milani FY, Milani BY, Shen X, Eslani M, Putra I, Huvard MJ, Sagha H, Djalilian AR, Rapamycin Prolongs the Survival of Corneal Epithelial Cells in Culture. Sci. Rep 7, 40308 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Desai P, Person S, Incorporation of the Green Fluorescent Protein into the Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Capsid. J. Virol 72, 7563–7568 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yakoub AM, Shukla D, Basal Autophagy Is Required for Herpes simplex Virus-2 Infection. Sci. Rep 5, 12985 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yakoub AM, Shukla D, Autophagy stimulation abrogates herpes simplex virus-1 infection. Sci. Rep 5, 9730 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jaishankar D, Yakoub AM, Bogdanov A, Valyi-Nagy T, Shukla D, Characterization of a proteolytically stable D-peptide that suppresses herpes simplex virus 1 infection: implications for the development of entry-based antiviral therapy. J. Virol 89, 1932–1938 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hadigal SR, Agelidis AM, Karasneh GA, Antoine TE, Yakoub AM, Ramani VC, Djalilian AR, Sanderson RD, Shukla D, Heparanase is a host enzyme required for herpes simplex virus-1 release from cells. Nat. Commun 6, 6985 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agelidis AM, Hadigal SR, Jaishankar D, Shukla D, Viral Activation of Heparanase Drives Pathogenesis of Herpes Simplex Virus-1. Cell. Rep 20, 439–450 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jaishankar D, Buhrman JS, Valyi-Nagy T, Gemeinhart RA, Shukla D, Extended Release of an Anti-Heparan Sulfate Peptide From a Contact Lens Suppresses Corneal Herpes Simplex Virus-1 Infection. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 57, 169–180 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yorek MS, Davidson EP, Poolman P, Coppey LJ, Obrosov A, Holmes A, Kardon RH, Yorek MA, Corneal Sensitivity to Hyperosmolar Eye Drops: A Novel Behavioral Assay to Assess Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 57, 2412–2419 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: BX795 blocks virus secretion and shows antiviral activity in other cell types.

Supplementary Figure 2: BX795 shows higher potency compared to existing antivirals.

Supplementary Figure 3: Therapeutic concentration of BX795 is non-toxic in HCE cells.

Supplementary Figure 4: BX795 does not mediate antiviral activity through TBK1.

Supplementary Figure 5: Antiviral activity of BX795 in the in vivo and ex vivo models of corneal infection.

Supplementary Figure 6: Uncropped blots for figures.

Supplementary Figure 7: Uncropped blots for supplementary figures.

Table S1. Primary data