Abstract

Sarcopenia is a geriatric syndrome currently defined as pathological loss of muscle mass and function. Sarcopenia is not only a major contributor to loss of physical function in older adults but is also associated with increased risk of morbidity, mortality, and increased healthcare costs. As a complex and multifactorial syndrome, sarcopenia has been associated with numerous degenerative changes during the aging process, but there is building evidence for significant contributions to the development of sarcopenia from neurodegenerative changes in the peripheral nervous system. A variety of interventions have been investigated for the treatment of sarcopenia, but current management is primarily focused on nutrition and therapeutic exercise interventions. Great strides have been made to improve screening procedures and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia, but continued optimization of diagnostic and screening strategies is needed to better identify individuals with sarcopenia or at risk of developing sarcopenia. Understanding and addressing the major drivers of sarcopenia pathogenesis will help develop therapeutics that can reduce the impact of sarcopenia on affected individuals and society.

I. Introduction

Maintaining and optimizing physical function and performance in older adults is becoming an increasingly important task. The geriatric syndrome, sarcopenia, which is currently defined as pathological loss of muscle mass and function, is a major contributor to impaired physical function and loss of independence in older adults. Sarcopenia results not only in physical impairments but only increased risk of mortality and morbidity1. At best, some decline of physical function is an inevitable consequence of aging, but the rates at which individuals lose physical function vary remarkably due to a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

When the term sarcopenia was first coined by Rosenberg in 1989 it was defined simply as loss of muscle mass, and until recently, the majority of research efforts have focused largely on the understanding the mechanisms of muscle wasting and the development of treatments to increase mass 2. Dynapenia, a term coined by Manini and Clark, is defined as age-related loss of muscle strength3. Dynapenia is a multifactorial phenomenon that can be related to deficits in muscle size or quality (muscle function per unit of muscle) as well as neuromuscular control3. What is clear from longitudinal studies is that loss of muscle function in older adults is more tightly associated with physical function and adverse outcomes as compared with muscle mass1. As such the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGOS) developed sarcopenia diagnostic criteria that encompasses both loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia) and either the loss of muscle strength or physical function (dynapenia)1. The worldwide prevalence of sarcopenia in individuals aged 60 or older has been estimated at about 10%, but figures vary widely depending on the diagnostic cut points used and the population being assessed 4.

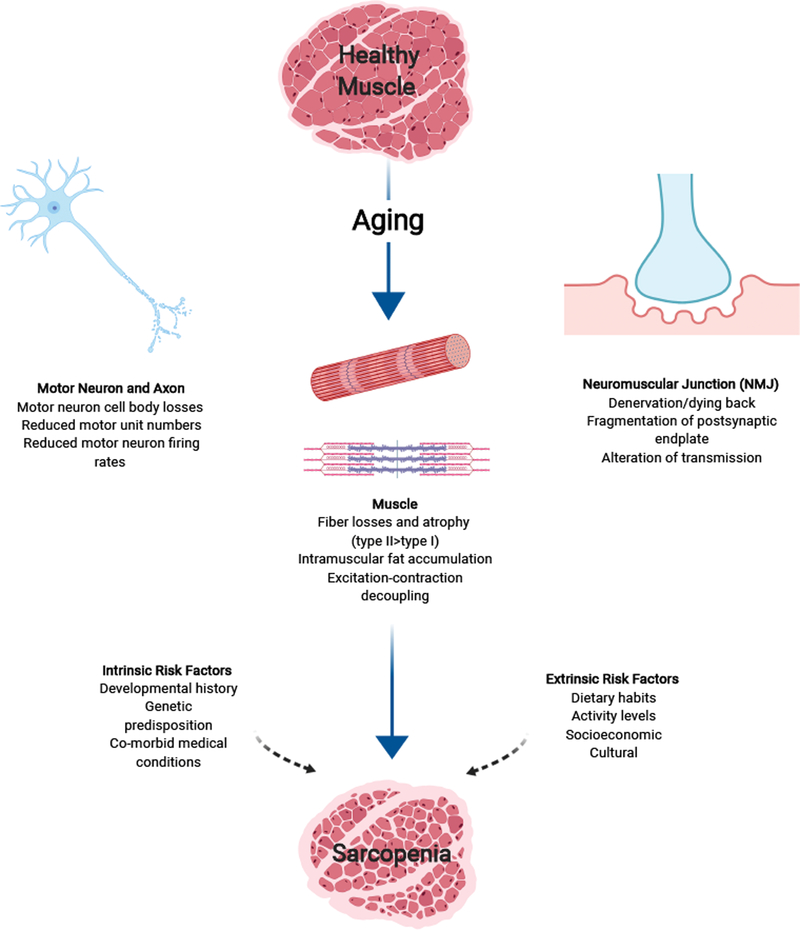

Understanding, modifying, and exploiting the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that modify individual risk can help facilitate development of strategies to mitigate loss of physical function and lessen the burden of healthcare costs on society (Figure 1). In this review, we aim to provide an overview of the current understanding of age-related muscle dysfunction and sarcopenia, current clinical practices and recommendations for managing sarcopenia, and insight into future needs for maintaining and improving muscle function in older adults. The major goal of this review is to provide an overview of the current understanding of muscle dysfunction in older adults from a systems based perspective, outside of the muscle centric view that has historically dominanted the study of sarcopenia. Age-related degeneration and decline results from a variety of disruptions in normal cellular and molecular pathways or “hallmarks” of aging all of which at some point have been implicated in loss of physical funciton in older adults5. A clear understanding of the potential cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying sarcopenia is lacking and is beyond the scope of this review.

Figure 1.

Age-related Neuromuscular Deficits and Risk Factors that contribute to Age-related muscle dysfunction and sarcopenia

II. Impact of Age on Neuromuscular Form and Function

Muscle function is dependent on intact excitation of muscle fibers via sufficient neuromuscular junction transmission, endplate potential generation, and intact coupling of excitation and contraction at the subsarcolemmal level. Not only is neuromuscular integrity required for muscle contraction and force production but also maintenance of trophic support for retained muscle bulk. There has long been interest in the impact of age on the form and function of the neuromuscular system. Historically, contrasts have primary made between young adults and older individuals (or between young and old preclinical models), but more recently the emphasis has shifted to investigating changes that contribute to geriatric syndromes such as sarcopenia or physical frailty by comparing sarcopenic adults to older adults with healthy or successful aging6.

Historically, decline of muscle performance has been simplistically attributed to muscle mass, but longitudinal studies have shown that losses of muscle performance outpace losses of muscle mass at rates that are two fold or greater than that of muscle wasting 7. The discordance between changes of muscle mass and muscle function highlight the importance of muscle “quality” as a measure of muscle function per unit of muscle. An array of changes in muscle are associated with advancing age including losses of muscle size, mass, as well as muscle fiber numbers 8. The effects of aging appear to affect type II fibers to a greater extent as compared with type I fibers 8. There is building evidence for neurological origins of sarcopenia, and neurological factors have increasingly been considered as an important factor in determination of muscle quality9. Over four decades ago, Tomlinson and colleagues demonstrated 25% losses of motor neuron counts in post-mortem tissues from the 2nd to the 9th decade with some individuals losing up to 50%10. Electrophysiological recordings of motor unit numbers have consistently shown significant reductions in older individuals and aged preclinical models, and similarly motor unit firing rates are also reduced11–13. Preclinical studies have consistently shown alterations of neuromuscular junction (NMJ) morphology in aged animals 14. There is much less known about morphological changes at the NMJ in older adults due to challenges in obtaining suitable muscle tissue for analyses14. In two older studies that investigated intercostal muscles post-mortem, using light and electron microscopy, aging was associated with fragmentation and reduced post-synaptic folding15,16. A more recent study demonstrated that human NMJ morphology is much less complex as compared with rodents, and also suggested that no overt changes of NMJ morphology occur across the lifespan in humans17. A major caveat of this study by Jones and colleagues is that muscles analyzed were obtained during limb amputations related to peripheral vascular disease and diabetes, both of which are associated with peripheral nerve pathology17. Therefore, continued work is needed to better understand the consequences of aging on NMJ morphology across the lifespan. Prior work in aged mice suggested that physical function is related to NMJ transmission defects on single fiber electromyography (SFEMG), and more recently aged mice have been demonstrated on SFEMG to have features of NMJ transmission failure likely related to hypoexcitability of muscle fibers rather than synaptic dysfunction18,19. There is less electrophysiological evidence supporting abnormal NMJ transmission in older adults, but in one clinical study, Piasecki and colleagues studied older men with and without sarcopenia and showed that aging was associated with motor unit losses that were indistinguishable between older men with and without sarcopenia 20. Yet, in contrast to the non-sarcopenia older men, the sarcopenic men showed small motor unit potential sizes and increased interpotential variability suggesting less reinnervation capacity and NMJ dysfunction 20.

Sarcopenia is independently associated with cognitive decline21. Therefore, although outside the scope of this article, it is also important to consider loss of integrity and function of the central nervous system in the context of muscle function22 Considering muscle function in the context of deficits within both the peripheral and central nervous systems will be critical for improving diagnostic and therapeutic developments.

III. Development and Evolution of Diagnostic Criteria

Sarcopenia is a complex, multifactorial process which presents significant challenges for designing and implementing simple methods for patient identification, diagnosis, and prognosis. Several diagnostic criteria have been developed originally based only on muscle mass, and more recent criteria have encompassed measures of muscle mass and muscle function. In 2010, the European Working Group developed and published cutpoints and criteria based on the presence of reduced muscle mass and either reduced muscle strength or physical function23. Other groups including the Asian Working Group on Sarcopenia (AWGS), and Foundation for the National Institute of Health have defined cutpoints from different populations (Table 1) 23–26.

Table 1:

Diagnostic Cutpoints for Lean Mass, Muscle Strength, and Physical Function. BMI: body mass index, DXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, aLM: appendicular lean mass

| Expert Group | Diagnostic Cutpoints | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle Mass | Muscle Strength (Grip) | Physical Function and Performance | |

| European Working Group on Sarcopenia |

BIA Women: <6.42 kg/m2 Men: <8.87 kg/m2 or DXA Women: <5.50 kg/m2 Men: <7.26 kg/m2 |

Grip Women: <20 kg Men: <30 kg |

Gait speed <1.0 m/s or SPPB <9/12 |

| Asian Working Group on Sarcopenia |

BIA Women: <5.70 kg/m2 Men: <7.00 kg/m2 or DXA Women: <5.40 kg/m2 Men: <7.00 kg/m2 |

Grip Women: <18kg Men: <28 kg |

Gait speed <1.0 m/s or 5-time chair stand test ≥12 s or SPPB≤ 9 |

| Foundation for the National Institutes of Health |

DXA Women: <19.7 kg Men: <15.0 kg or DXA (aLM per BMI) Women: <0.512 Men: <0.789 |

Grip Women: <16 kg Men: <26 kg or (Grip Per BMI) Women: <0.56 Men: <1.00 |

Gait speed <0.8 m/s |

The EWGSOP reconvened in 2018 (EWGSOP2) and provided updated recommendations regarding the use of a pathway of “Find-Assess-Confirm-Severity” (F-A-C-S) for use across spectrum of clinical practice and research studies1. In clinical practice, EWGSOP2 advises use of the simple SARC-F questionnaire to screen and identify individuals (“Find”) with probable sarcopenia(Table 2)1,27. While developing simple screening strategies is a move in the right direction, it is important to note that the SARC-F is not sensitive (~30%) but dose have good specificity28. Adding calf circumference to the SARC-F has been shown to improve sensitivity to ~61%28. The use of grip strength and chair stand test are recommended for the identification of reduced muscle strength1. Following screening and identification of at risk individuals, the diagnosis of sarcopenia is established on findings of muscle weakness and loss of muscle mass1. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) are recommended for use in usual clinical care for identifying reduced muscle mass, and the methods of DXA, MRI, and CT are recommended for use in research investigations1. Other outcome measures of function suggested for assessment of sarcopenia severity include assessments of physical performance include the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), the Timed-Up-and-Go (TUG), and the 400 m walk tests1.

Table 2:

SARC-F

| Questions | Scoring |

|---|---|

| How much difficulty do you have in lifting and carrying 10 pounds? | None = 0 Some = 1 A lot or unable = 2 |

| How much difficulty do you have walking across a room? | None = 0 Some = 1 A lot, use aids, or unable = 2 |

| How much difficulty do you have transferring from a chair or bed? | None = 0 Some = 1 A lot or unable without help = 2 |

| How much difficulty do you have transferring from a chair or bed? | None = 0 Some = 1 A lot or unable = 2 |

| How many times have you fallen in the past year? | None = 0 1–3 falls = 1 4 or more falls = 2 |

Scoring range: 0–10, 4 points or greater is predictive of sarcopenia, loss of independence with actitivities of daily living and increased risk of mortality

The EWGSOP suggested that sarcopenia be divided into diagnostic subcategories denoting chronicity as well as sarcopenia that is associated with other medical conditions1. Acute sarcopenia is defined as an acute condition with less than 6 months duration versus chronic sarcopenia has a duration equal to or greater than 6 months1. Individuals with co-morbid medical conditions including organ failure, inflammatory conditions, degenerative and inflammatory joint diseases, and neurological conditions, such as Alzheimer disease, are at increased risk of developing sarcopenia29,30. The term secondary sarcopenia is used to describe sarcopenia that is associated with a potential cause or risk factor as compared with primary sarcopenia which is associated with only advanced age1. Degenerative joint disease is another leading cause of disability that is closely associated with age-related loss of muscle function31. Sarcopenic obesity is a variant of sarcopenia in the context of excess adiposity and is associated with worsened physical function and increased risk of mortality1. Future work is needed to more fully understand whether stratifying patients into these potential different variants of sarcopenia is clincially meaningful in regards to potential treatments and prognosis.

Similar to EWGSOP, the AWGS more recently reconvened in 2019 to update recommendations regarding the diagnosis and treatment of sarcopenia26. The updated AGWS recommendations included a case finding, assessment, and diagnostic testing strategy26. Methods for case finding include calf circumference of <34 cm for men and <33 cm for woman, SARC-F of ≥4, or SARC-CalF ≥11. A diagnosis of “Possible sarcopenia” is based on findings of reduced muscle strength (handgrip strength) or reduced physical performance (5-time chair stand test) (Table 1)26. Diagnostic testing with measures of muscle strength, phyiscal peformance, and apendicular skeletal muscle mass are recommended. The diagnosis of “Sarcopenia” is based on low apendicular skeletal muscle mass combined with findings of reduced muscle strength or reduced physical performance based on cutpoints in Table 126. The diagnosis of “Severe sarcopenia” is based on reduced muscle strength, reduced physical performance, and reduced apendicular skeletal muscle mass based on cutpoints in Table 126.

It is important to point out that cachexia and disuse atrophy are other muscle wasting conditions with some similarities and differences as compared with sarcopenia. In contrast to sarcopenia which is a degenerative condition resulting in loss of muscle mass and strength and is associated increased intramuscular fat, cachexia is a catabolic disorder that results in loss of muscle and fat mass32. While sarcopenia results in atrophy and loss of muscle fibers, disuse atrophy, in contrast, results in atrophy without fiber losses. Importantly, all three, cachexia, sarcopenia, and disuse atrophy, can co-exist in the same patient compounding the effects of muscle dysfunction.

VI. Management of Sarcopenia

There are currently no pharmacological interventions available that are specifically designed for the treatment of sarcopenia. Management of sarcopenia currently includes reducing risk factors, minimizing the impact of contributory co-morbid medical conditions, and initiation of interventions such as nutrition and exercise.

Exercise

The primary intervention for prevention and management of sarcopenia is physical exercise. Importantly, while it is well established that resistance exercise, in isolation or in combination with other modes of training, demonstrates positive effects in older adults, the evidence in sarcopenic older adults is more limited and is based on short term studies33–36. Ideally, physical exercise interventions should be designed and implemented to address all attributes of physical fitness including strength, stamina, endurance, coordination, balance, and body composition. In particular, consideration should be given in regards to an individual’s current abilities and fitness, available resources, as well as needs during daily activities. It is also important to consider some of the challenges posed by exercise interventions which may include inadequate patient engagement, lack of resources, or limitations imposed by co-morbid medical conditions such as degenerative or inflammatory joint disease.

When considering muscle function, often muscle mass and strength are primarily emphasized, but aerobic, range of motion, and balance training are also important considerations to consider depending on patient function and needs. Aerobic exercise interventions have been less frequently implemented and studied in sarcopenic populations, likely due to expectations of less muscle strength and mass improvements. Yet, combining strengthening and aerobic exercise may offer more comprehensive fitness and be protective effects against muscle loss with aging37. Functional movements not only depend on contractile function but also adequate passive and active range of motion and adequate balance. Prior work has suggested that limitations of joint mobility may even play a primary role in the limitation of mobility and physical function in older adults 38,39. Therefore, strategies and interventions for maintaining sufficient active and passive range of motion are critically important aspects of exercise interventions.

Nutrition

Nutrition is an important consideration in the management of sarcopenia. The relationship between physical activity, nutrition and health-related quality of life in older adults has been described in the literature over the past decades in cross-sectional studies40. Adequate nutritional intake is a prerequisite for a good quality of life in older persons to prevent deficiencies and malnutrition, but metanalysis have shown variable results regarding the effects nutritional interventions, alone or in combination with exercise interventions, to improve lean mass and muscle strength41. Generally, protein intake of 1.2–1.5 grams/kg of body mass is recommended40. A recent interventional trial in community dwelling, sarcopenic, older adults demonstrated no benefit with protein supplementation when combined with a low intensity exercise program and it was proposed that nutritional support may only be beneficial in populations with deficiency or subclinical deficiency of nutrtion42. Another study demonstrated a synergistic effect with amino acid supplementation combined with a moderate intensity comprehensive exercise intervention43. Adequate vitamin D is essential for muscle contraction and induces protein synthesis, muscle performance, strength, improves muscle fiber composition and morphology, and therefore assessment and repletion of vitamin D levels, if deficient, is an important consideration44. Older adults may be at increased risk for vitamin D deficiency due to decreased sun exposure44. Beta-hydroxy beta-methylbutyrate (a metabolite of the essential amino acid leucine) has been shown to have possible positive effects on muscle mass but effects on muscle function have been less consistent 40.

Lifestyle Factors and Modifications

The influences of lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption and smoking may also contribute to loss of muscle mass and function45,46. For example, chronic alcoholic myopathy is characterized by selective atrophy of type II muscle fibers, leading to reduction of muscle mass by up to 30% [57]. Alcohol abuse appears to affect skeletal muscle severely, promoting its damage and wasting. Although alcohol consumption is not known as a direct cause of sarcopenia, the adverse effects of alcohol on skeletal muscle suggest that chronic alcohol consumption may promote loss of muscle mass and strength in old age47. Some in vivo studies indicate that alcohol-induced muscle damage may be the result of impaired synthesis of muscle protein rather than increased muscle catabolism47. Therefore, high alcohol intake is a lifestyle habit that may contribute to the development of sarcopenia. Montes de Oca et al. explored the effects of smoking on skeletal muscle by studying biopsies of the vastus lateralis muscle and found structural and metabolic damage in skeletal muscle of smokers, including decreased cross-sectional area of type I muscle fibers, and a similar trend in type IIa fibers of smokers46. Petersen et al. studied the effect of smoking on protein metabolism in skeletal muscle of smokers and non-smokers about the age of 60 and found that the fractional synthesis rate of muscle was significantly lower in smokers compared with non-smokers48. Petersen et al. concluded that smoking may increase the risk of sarcopenia by impairing muscle protein synthesis and up-regulating genes associated with impaired muscle maintenance.48 Thus, lifestyle habits regarding alcohol and tobacco use have a substantial impact on the progression of sarcopenia and the ability to prevent and treat the loss of muscle mass and function in old age.

V. Consideration of Sarcopenia as a Multifactorial Syndrome

Sarcopenia is a complex geriatric syndrome, and the major factors that drive phenotype of muscle weakness and wasting in older adults remain to be fully defined. As such, it is unclear whether we should we consider sarcopenia primarily a myopathic or neurogenic condition (or a combination). There is strong evidence for degenerative changes in both the neurological and muscular components of the neuromuscular system, and it remains a clear possibility that different pathological processes may occur between different populations affected by sarcopenia (i.e. neurogenic and myopathic variants of sarcopenia). Why should we care? It is possible that future studies may reveal that determining the main drivers of a sarcopenia phenotype is important for prognosis or for the design and implementation of effective therapeutic strategies. In the future, different aspects (or stages) of neuromuscular degeneration may need to be addressed with differing potential therapeutic strategies and mechanisms. Table 3 presents a forward looking view on how different sarcopenia phenotypes could require specifically designed therapeutics. A phenotype specific approach to therapeutic design and testing may be critical to acheive satisfactory patient stratification and positive outcomes in the future.

Table 3:

Potential Neuromuscular Targets for Therapeutic Design

| Targeting Therapies for Sarcopenia as Potential Multifactorial Syndrome | ||

|---|---|---|

| Neuromuscular Deficit | Pathophysiological Mechanism of Dysfunction | Possible Therapeutic Strategies? |

| Motor Neuron and Axon | ||

| Cell body or axonal loss or dysfunction 10 | Cellular death or dysfunction | Neuro or cytoprotective agents |

| Motor neuron discharge deficits 13 | Changes of motor neuron excitability | Modulation of ion currents |

| Neuromuscular Junction (NMJ) | ||

| Fragmentation/Denervation 11,15–17 | Dying back of motor axons or primary NMJ degeneration | Encourage reinnervation or NMJ assembly/stability |

| Transmission Failure 19,48 | Loss of safety factor at the NMJ | Increase presynpatic acetylcholine release, postsynpatic endplate response, or alter postsynpatic threshold |

| Muscle | ||

| Muscle atrophy and wasting 8,49 | Atrophy and loss of muscle fibers (type II>type I), imbalance of catabolism/anabolism | Modulation of muscle mass |

| Excitation-contraction decoupling 50 | Altered calcium release/recycling, disruption of dihydropyridine and ryanodine receptors | Subsarcolemmal skeletal muscle activators |

VI. Conclusions

Improved strategies are needed for screening, diagnosis and management of sarcopenia. Fortunately, the neuromuscular system retains remarkable plasticity even in older ages, and because of this, exercise interventions can improve physical function. Additionally, addressing other modifiable risk factors such as optimizing nutritional status and aggressive management of co-morbid medical conditions that contribute to secondary sarcopenia and other factors such as suboptimal nutritional status can help reduce the burden of sarcopenia. Future needs for sarcopenia include a more comprehensive understanding of the primary drivers of muscles weakness and wasting in older adults and improved therapeutic interventions for individuals for whom exercise is not feasible or ineffective.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging 5R03AG050877 and R56AG055795 to WA.

References:

- 1.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age and ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. Clin Geriatr Med. August 2011;27(3):337–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark BC, Manini TM. Sarcopenia =/= dynapenia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. August 2008;63(8):829–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shafiee G, Keshtkar A, Soltani A, Ahadi Z, Larijani B, Heshmat R. Prevalence of sarcopenia in the world: a systematic review and meta- analysis of general population studies. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2017;16:21–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark BC, Manini TM, Wages NP, Simon JE, Clark LA. Voluntary vs Electrically Stimulated Activation in Age-Related Muscle Weakness. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(9):e1912052-e1912052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delmonico MJ, Harris TB, Visser M, et al. Longitudinal study of muscle strength, quality, and adipose tissue infiltration. The American journal of clinical nutrition. December 2009;90(6):1579–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lexell J, Taylor CC, Sjostrom M. What is the cause of the ageing atrophy? Total number, size and proportion of different fiber types studied in whole vastus lateralis muscle from 15- to 83-year-old men. Journal of the neurological sciences. April 1988;84(2–3):275–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon YN, Yoon SS. Sarcopenia: Neurological Point of View. Journal of bone metabolism. May 2017;24(2):83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomlinson BE, Irving D. The numbers of limb motor neurons in the human lumbosacral cord throughout life. Journal of the neurological sciences. November 1977;34(2):213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piasecki M, Ireland A, Jones DA, McPhee JS. Age-dependent motor unit remodelling in human limb muscles. Biogerontology. 2016;17:485–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheth KA, Iyer CC, Wier CG, et al. Muscle strength and size are associated with motor unit connectivity in aged mice. Neurobiol Aging. July 2018;67:128–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ling SM, Conwit RA, Ferrucci L, Metter EJ. Age-associated changes in motor unit physiology: observations from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2009;90(7):1237–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taetzsch T, Valdez G. NMJ maintenance and repair in aging. Current Opinion in Physiology. 2018/August/01/ 2018;4:57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wokke JHJ, Jennekens FGI, van den Oord CJM, Veldman H, Smit LME, Leppink GJ. Morphological changes in the human end plate with age. Journal of the neurological sciences. 1990/March/01/ 1990;95(3):291–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oda K Age changes of motor innervation and acetylcholine receptor distribution on human skeletal muscle fibres. Journal of the neurological sciences. Nov-Dec 1984;66(2–3):327–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones RA, Harrison C, Eaton SL, et al. Cellular and Molecular Anatomy of the Human Neuromuscular Junction. Cell reports. November 28 2017;21(9):2348–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung T, Tian Y, Walston J, Hoke A. Increased Single-Fiber Jitter Level Is Associated With Reduction in Motor Function With Aging. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists. August 2018;97(8):551–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chugh D, Iyer CC, Wang X, Bobbili P, Rich MM, Arnold WD. Neuromuscular junction transmission failure is a late phenotype in aging mice. Neurobiol Aging. November 5 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piasecki M, Ireland A, Piasecki J, et al. Failure to expand the motor unit size to compensate for declining motor unit numbers distinguishes sarcopenic from non-sarcopenic older men. The Journal of physiology. May 1 2018;596(9):1627–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang KV, Hsu TH, Wu WT, Huang KC, Han DS. Association Between Sarcopenia and Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. December 1 2016;17(12):1164.e1167–1164.e1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.James EG, Leveille SG. Coordination Impairments Are Associated With Falling Among Older Adults. Oct-Dec 2017;43(5):430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cruz-Jentoft, European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older P. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Aging. 2010;39:412–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen LK, Liu LK, Woo J, et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. February 2014;15(2):95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Studenski SA, Peters KW, Alley DE, et al. The FNIH sarcopenia project: rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. May 2014;69(5):547–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen L-K, Woo J, Assantachai P, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020;21(3):300–307.e302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. SARC-F: A Simple Questionnaire to Rapidly Diagnose Sarcopenia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013/August/01/ 2013;14(8):531–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang M, Hu X, Xie L, et al. Screening Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: SARC-F vs SARC-F Combined With Calf Circumference (SARC-CalF). J Am Med Dir Assoc. March 2018;19(3):277.e271–277.e278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogawa Y, Kaneko Y, Sato T, Shimizu S, Kanetaka H, Hanyu H. Sarcopenia and Muscle Functions at Various Stages of Alzheimer Disease. Frontiers in Neurology. 2018-August-28 2018;9(710). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landi F, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Liperoti R, et al. Sarcopenia and mortality risk in frail older persons aged 80 years and older: results from ilSIRENTE study. Age Ageing. March 2013;42(2):203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shorter E, Sannicandro AJ, Poulet B, Goljanek-Whysall K. Skeletal Muscle Wasting and Its Relationship With Osteoarthritis: a Mini-Review of Mechanisms and Current Interventions. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2019;21(8):40–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tisdale MJ. Mechanisms of Cancer Cachexia. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(2):381–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu CJ, Latham NK. Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. July 08 2009(3):Cd002759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore SA, Hrisos N, Errington L, et al. Exercise as a treatment for sarcopenia: an umbrella review of systematic review evidence. Physiotherapy. August 9 2019;107:189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Vries NM, van Ravensberg CD, Hobbelen JSM, Olde Rikkert MGM, Staal JB, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MWG. Effects of physical exercise therapy on mobility, physical functioning, physical activity and quality of life in community-dwelling older adults with impaired mobility, physical disability and/or multi-morbidity: A meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews. 2012/January/01/ 2012;11(1):136–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denison HJ, Cooper C, Sayer AA, Robinson SM. Prevention and optimal management of sarcopenia: a review of combined exercise and nutrition interventions to improve muscle outcomes in older people. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:859–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laurin JL, Reid JJ, Lawrence MM, Miller BF. Long-term aerobic exercise preserves muscle mass and function with age. Current Opinion in Physiology. 2019/August/01/ 2019;10:70–74. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jung H, Yamasaki M. Association of lower extremity range of motion and muscle strength with physical performance of community-dwelling older women. J Physiol Anthropol. 2016;35(1):30–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beissner KL, Collins JE, Holmes H. Muscle force and range of motion as predictors of function in older adults. Phys Ther. June 2000;80(6):556–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beaudart C, McCloskey E, Bruyère O, et al. Sarcopenia in daily practice: assessment and management. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):170–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao CD, Chen HC, Huang SW, Liou TH. The Role of Muscle Mass Gain Following Protein Supplementation Plus Exercise Therapy in Older Adults with Sarcopenia and Frailty Risks: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis of Randomized Trials. Nutrients. July 25 2019;11(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bjorkman MP, Suominen MH, Kautiainen H, et al. Effect of Protein Supplementation on Physical Performance in Older People With Sarcopenia-A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. February 2020;21(2):226–232.e221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim HK, Suzuki T, Saito K, et al. Effects of Exercise and Amino Acid Supplementation on Body Composition and Physical Function in Community-Dwelling Elderly Japanese Sarcopenic Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(1):16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia M, Seelaender M, Sotiropoulos A, Coletti D, Lancha AH. Vitamin D, muscle recovery, sarcopenia, cachexia, and muscle atrophy. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.). 2019/April/01/ 2019;60:66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rom O, Kaisari S, Aizenbud D, Reznick AZ. Lifestyle and sarcopenia-etiology, prevention, and treatment. Rambam Maimonides Med J. October 2012;3(4):e0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montes de Oca M, Loeb E, Torres SH, De Sanctis J, Hernandez N, Talamo C. Peripheral muscle alterations in non-COPD smokers. Chest. January 2008;133(1):13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steiner JL, Lang CH. Dysregulation of skeletal muscle protein metabolism by alcohol. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2015;308(9):E699–E712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petersen AM, Magkos F, Atherton P, et al. Smoking impairs muscle protein synthesis and increases the expression of myostatin and MAFbx in muscle. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. September 2007;293(3):E843–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]