Abstract

Background:

Two of the most important causes of global disease fall in the realm of environmental health: household air pollution (HAP) and poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions. Interventions, such as clean cookstoves, household water treatment, and improved sanitation facilities, have great potential to yield reductions in disease burden. However, in recent trials and implementation efforts, interventions to improve HAP and WASH conditions have shown few of the desired health gains, raising fundamental questions about current approaches.

Objectives:

We describe how the failure to consider the complex systems that characterize diverse real-world conditions may doom promising new approaches prematurely. We provide examples of the application of systems approaches, including system dynamics, network analysis, and agent-based modeling, to the global environmental health priorities of HAP and WASH research and programs. Finally, we offer suggestions on how to approach systems science.

Methods:

Systems science applied to environmental health can address major challenges by a) enhancing understanding of existing system structures and behaviors that accelerate or impede aims; b) developing understanding and agreement on a problem among stakeholders; and c) guiding intervention and policy formulation. When employed in participatory processes that engage study populations, policy makers, and implementers, systems science helps ensure that research is responsive to local priorities and reflect real-world conditions. Systems approaches also help interpret unexpected outcomes by revealing emergent properties of the system due to interactions among variables, yielding complex behaviors and sometimes counterintuitive results.

Discussion:

Systems science offers powerful and underused tools to accelerate our ability to identify barriers and facilitators to success in environmental health interventions. This approach is especially useful in the context of implementation research because it explicitly accounts for the interaction of processes occurring at multiple scales, across social and environmental dimensions, with a particular emphasis on linkages and feedback among these processes. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP7010

Introduction

Two environmental risk factors underlie the substantial global disease burden affecting young children and vulnerable populations around the world: household air pollution (HAP) exposure and deficiencies in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). Both HAP and WASH face challenges to underlying assumptions regarding the viability of known interventions to achieve intended and sustained reductions in disease burden. Observational studies of HAP have consistently shown strong associations with adverse health conditions throughout the life course, including pneumonia, hypertension, and adverse birth outcomes (Thakur et al. 2018), as well as all-cause mortality (Hystad et al. 2019). Poor WASH is also associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including enteric viral, bacterial, and protozoan pathogen infections and diarrheal disease, schistosomiasis, and soil-transmitted helminth infections (Clasen et al. 2015; GBD 2016 Risk Factors Collaborators 2017). Technological solutions designed, investigated, and evaluated in laboratory settings, including clean cookstoves and water filters, offer promising solutions, but seldom deliver expected results when implemented in real-world settings (Clasen and Smith 2019; Sesan et al. 2018). Recently completed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have returned disappointing results for interventions that are already in widespread use, raising questions regarding basic assumptions of efficacy, effectiveness, potential for scale-up, and technology and policy options to address these priority environmental health concerns (Luby et al. 2018; Mortimer et al. 2017; Null et al. 2018).

In the present paper we consider HAP and WASH together, despite their different exposures and etiologies, because of four important commonalities. First, the greatest disease burden for both is concentrated in the poorest populations of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially in rural and peri-urban areas. Second, although both HAP and WASH are subject to important policy-based social service and infrastructure challenges, they are commonly addressed with interventions at the household and community levels (e.g., cleaner cookstoves, latrines, and water filtration devices). Third, these technology-focused interventions have both struggled to achieve the high levels of reach, adoption, and adherence necessary to reduce exposure and improve health. Finally, the emissions/effluents from one home have wider ecological impacts or spillover effects, suggesting that high levels of adoption are required in order to achieve favorable health outcomes at individual, household, and community scales (Sesan et al. 2018).

Here we argue that a systems science approach offers powerful, underused tools to develop guidance for intervention design and implementation in HAP and WASH. Systems science is the application of scientific methods to the understanding of complex systems. It allows for consideration of problems and solutions across multiple dimensions, at various scales, and is dynamic in scope. A focus on systems challenges reductionist explanations that seek to explain behavior in terms of properties of constituent parts (Bunge 1997; Capra and Luisi 2014) and considers emergent properties that cannot be understood by reducing behavior to constituent terms. Challenges to implementing and sustaining evidence-based interventions, especially in complex socio-environmental arenas, are often systemic in nature; and thus, systems science methods may be especially appropriate (Luke et al. 2018). Systems science is an important complement to the randomized controlled trial approach that has dominated both HAP and WASH research in recent years. Unexpected and often disappointing trial results suggest that a different approach to studying implementation processes and outcomes is needed.

In public health, systems science methods have been applied to a wide range of issues including tobacco policy and regulation, cancer prevention, infectious disease, obesity and diabetes prevention, intentional injury, health systems, drug abuse/addiction, and others (Luke and Stamatakis 2012). To date, their application to environmental health challenges is limited (Currie et al. 2018).

Where HAP Programs Have Underdelivered

Since the 1950s, many efforts at scales ranging from the local to the national have sought to improve household access to clean cookstoves (Manibog 1984). The vast majority of efforts prior to 2000 focused on decreasing consumption of solid fuels to reduce perceived pressure on forest resources, and subsequently, global warming contributions from the same fuels accelerated interest in the field (Rosenthal 2015; K Smith et al. 2000). With recognition of the enormous health burden of HAP over the past decade, the household energy sector has turned its focus to promoting measures with the greatest potential for mitigating this adverse health burden. Focusing on health goals has raised expectations for clean cooking technologies and their implementation considerably, but supposedly clean cookstove interventions have not always delivered desired improvements in health. Despite air pollution reductions of 50% or more in the most successful programs, post-intervention levels of fine particulate matter ( in aerodynamic diameter) generally remained 2–40 times higher than the World Health Organization interim air quality guideline of 35 average annual concentration in homes with the new stoves (Quansah et al. 2017).

Randomized trials with cleaner stoves or fuels have also returned mixed results (Alexander et al. 2017; Mortimer et al. 2017; Smith et al. 2011; Thompson et al. 2011; Tielsch et al. 2016). Some of the shortfalls are related to inherent limitations of the technologies. A well-understood limitation of previous household energy programs was that air pollution emissions from improved cookstoves in community settings greatly exceeded what was expected based on laboratory testing (Coffey et al. 2017; Eilenberg et al. 2018). Clean fuel interventions with liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), electric induction, ethanol, biogas, and pellet-fueled gasifier stoves have consistently outperformed traditional and improved solid-fuel stoves in both laboratory and field studies (Champion and Grieshop 2019; Jagger et al. 2017; Wathore et al. 2017) and are the most likely to achieve the desired air quality and health benefits.

Beyond these technology lessons, several implementation issues have emerged, leading HAP interventions to fall short of expectations. These include low initial adoption rates for clean fuels and stoves (Lewis and Pattanayak 2012; Mobarak et al. 2012; Troncoso and Soares da Silva 2017), concomitant use of polluting stoves (stove stacking) among adopters (Masera et al. 2000; Puzzolo et al. 2016), and issues with supply chains and cost for both stoves and fuels (Jagger and Das 2018; Puzzolo et al. 2019).

Finally, because most relevant LMIC homes are relatively open to outdoor air, ambient air quality sets the floor for household exposure levels. Evidence is growing that household cooking can be a major contributor to poor local outdoor air quality (Butt et al. 2016; Chowdhury et al. 2019a; Snider et al. 2018) and its associated health effects (Conibear et al. 2018). Still poorly understood are the degree and conditions under which greater density and coverage of clean cooking interventions at scale can reliably reduce background ambient pollution (although see Chowdhury et al. 2019b for estimates for India).

The accumulating body of evidence from experiments, observational studies, and models over the past two decades has led to a consensus in the health science community that achieving major reductions in levels of HAP will require at least three important shifts in the way HAP programs and policies are conceived. First, the technology, including fuels, must emit little to no particulate matter (Wathore et al. 2017; World Health Organization 2014). Second, individual households must rely on clean fuels and stoves for the overwhelming majority of their energy needs, with only very occasional combustion of polluting fuels for any purpose (Johnson and Chiang 2015). Third, local ambient conditions need also be relatively clean, probably requiring high, effective coverage of clean cooking at the community and larger levels (see, e.g., Weaver et al. 2019).

Where WASH Programs Have Underdelivered

Through the first half of the last century, higher-income settings implemented large-scale infrastructural solutions such as sewerage, centralized water and wastewater treatment, and piped water to homes, achieving significant improvements in health (Cutler and Miller 2005). In contrast, in rural LMIC settings, such investments were (and continue to be) insufficient, especially in sewerage. As such, improvements in water and sanitation were traditionally focused on expanding access to improved, but low-cost, technologies (protected wells and springs, pit latrines) that were suitable for scaling up in rural settings. Other household-scale approaches, including behavior change programs to promote handwashing and promotion of water filtration devices to provide clean water at the point of use, were steadily advanced by development agencies and local nongovernmental organizations (Dangour et al. 2013; Darvesh et al. 2017). These approaches were believed to be cost-effective solutions because they did not require substantial expenditures on infrastructure. With limited resources, lower-income countries continued to implement these low-cost approaches to WASH, with some affirming evidence of efficacy in randomized and nonrandomized trials and systematic reviews through the early 2000s (Esrey et al. 1985, 1991).

In more recent years, a number of rigorous randomized trials of low-cost interventions in WASH yielded findings of little or no effect for most outcomes of interest, including diarrhea, linear growth, stunting, and helminth infections (Clasen et al. 2015). Examples include large sanitation trials in India (Clasen et al. 2014; Patil et al. 2014) and trials of multiple WASH and nutrition interventions in Bangladesh (Luby et al. 2018), Kenya (Null et al. 2018), and Zimbabwe (Humphrey et al. 2019). Except for the Bangladesh trial, which reported protective effects from the sanitation and handwashing interventions, none of these trials showed that WASH interventions were protective against diarrhea or stunting. Some of these studies were effectiveness trials of programmatically delivered interventions in which investigators explored the effects of improved water supplies, household water treatment, improved sanitation, and handwashing with soap (Clasen et al. 2014; Dangour et al. 2013; Patil et al. 2014; Sinharoy et al. 2017). In those cases, the investigators generally found poor intervention quality, coverage, uptake, or use—failures that could explain the lack of protective health effects because of incomplete interruption of exposure to human enteric pathogens.

Correct, consistent, and sustained adoption of healthy WASH practices, including handwashing with soap, was also shown to present important behavior change barriers (Freeman et al. 2014; Martin et al. 2018). Increasingly, poor compliance was shown to be fundamentally limiting for most WASH interventions (Brown and Clasen 2012). However, even in efficacy trials in which the interventions achieved high levels of compliance (Humphrey et al. 2019; Luby et al. 2018; Null et al. 2018), results were disappointing.

These recent studies highlight both our limited understanding of which modes of diarrheal disease transmission are dominant and how these might vary by environmental context. Some pathways, such as food and animals, are not effectively addressed with basic WASH infrastructure. Furthermore, we are learning that many water supply systems periodically deliver unsafe water, often due to intermittent operation (Bivins et al. 2017). Studies of low-cost approaches to drinking water revealed that, even if safe at the point of collection, water was often contaminated with fecal pathogens during storage in the home (Levy et al. 2008; Wright et al. 2004). In some cases, exposures may also arise from zoonotic agents not addressed by conventional sanitation interventions (Berendes et al. 2018; Daniels et al. 2016; Penakalapati et al. 2017).

WASH is considerably more mature than the HAP field and offers experience with more types of interventions. The HAP community can learn a great deal from WASH experiences (Clasen and Smith 2019; Sesan et al. 2018). However, results from these recent WASH trials also suggest that major challenges underlie the successful implementation of environmental health interventions in low-income settings. Despite a much deeper evidence base to draw upon, WASH continues to be a major public health concern for most low-income countries.

Diagnosing the Problem

When outcome measures fall short of expectations, commentators frequently focus on the inadequacies of the technology. As described in the preceding two sections, there are numerous examples of projects that have underdelivered because of shortcomings of the technology. Many improved biomass stoves do not deliver the air pollution reductions required to greatly minimize adverse health impacts, although they do reduce fuel use and may provide some reduction in air pollution (Jagger et al. 2017). Improved water supplies do not necessarily provide water that is safe at the point of collection (Bain et al. 2014), in part because most household water treatment options fail to cover the full array of waterborne pathogens or fail to keep water safe after it is treated (Shaheed et al. 2014). Even if water is effectively treated, the benefits of household-level water quality interventions are realized only if they are used exclusively (Enger et al. 2013).

Furthermore, focusing primarily on the household level may not always be the appropriate scale of implementation and evaluation. Household–to–ambient air pollution interactions (Huang et al. 2015), and herd immunity to diarrheal disease demonstrate substantial indirect effects at the community level (Fuller and Eisenberg 2016). Associated nonlinear exposure–response relationships (Burnett et al. 2014; Jung et al. 2017) mean that density and coverage of the intervention may be critical. In some cases, this becomes evident during efficacy-stage testing under relatively controlled conditions. However, it is more commonly apparent when the interventions are deployed in communities at scale.

Importantly, even effective, scaled interventions may fall short when attempted in a new environment. LPG cooking interventions may be very effective where air pollution exposure is dominated by indoor sources, but in highly polluted urban environments, they may not reduce fine particulate and other air pollutants sufficiently to reach the threshold levels thought necessary to achieve health gains (Liu et al. 2019), but see Chowdhury et al. (2019b) for an estimate of ambient effects of a large-scale clean fuel intervention in India. A WASH intervention that is effective in one setting may be wholly ineffective in another where there is a different dominant pathogen or transmission pathway (Eisenberg et al. 2007). Relevant social variables include individual, community, or institutional behaviors. This may also reflect larger-scale systems problems related to supply chains, availability of substitutes (e.g., freely available biomass fuels), price instability, and regulatory challenges that these technologies confront in real-world settings, especially in LMICs (Thomas 2016).

Finally, sustained effectiveness of most public health interventions is a major challenge. In low resource settings, program leaders often find themselves trapped in cycles of iterative attempts to maintain or improve outcomes in the original communities. Decline in adherence to proven use protocols is common without continual reinforcement of behavior change messages over time (Brown and Clasen 2012) or adequate supply or servicing of new technologies required to achieve exposure reductions (Jagger and Das 2018). For example, wide-scale efforts to encourage community-led total sanitation in rural low-income settings have suffered from backsliding (slippage) to open defecation (Venkataramanan et al. 2018). Importantly, even if an intervention is effective initially, exogenous conditions may change over time. For example, economic factors such as price increases or supply chain failures make clean fuels (Puzzolo et al. 2019) and water treatment devices (Schmidt and Cairncross 2009) and their maintenance less accessible. Migration to and from communities may fundamentally affect social or environmental patterns necessary to maintain the health benefits of the intervention (Eisenberg et al. 2006). Climate change brings unforeseen flooding, potentially distributing contaminants across the household and the village (Mertens et al. 2019). For each of these likely developments, the intervention no longer works in the way it did under prior conditions.

RCTs have enormous power to provide internal validity (i.e., high causal inference/attribution) and insights into adoption and adherence in tightly controlled experimental settings. RCTs also have a critical role in defining the scalable unit of an intervention (e.g., a combined technology and behavior change package). However, external validity of trial results can be often limited by contextual factors that underlie success or shortfalls in programs, including environmental and social differences of the sort described in the preceding paragraphs. Given the recent history of failures of larger effectiveness and translational trials for these environmental health interventions, some may conclude that they just are not effective, or alternatively, that they were inadequately deployed.

However, the importance of both endogenous and contextual factors as critical determinants of sustainability and scalability suggests that different analytical approaches are needed to support the development of effectiveness and translational studies whether these are conducted through RCTs or other approaches.

Cycles in Environmental Health Intervention Policies

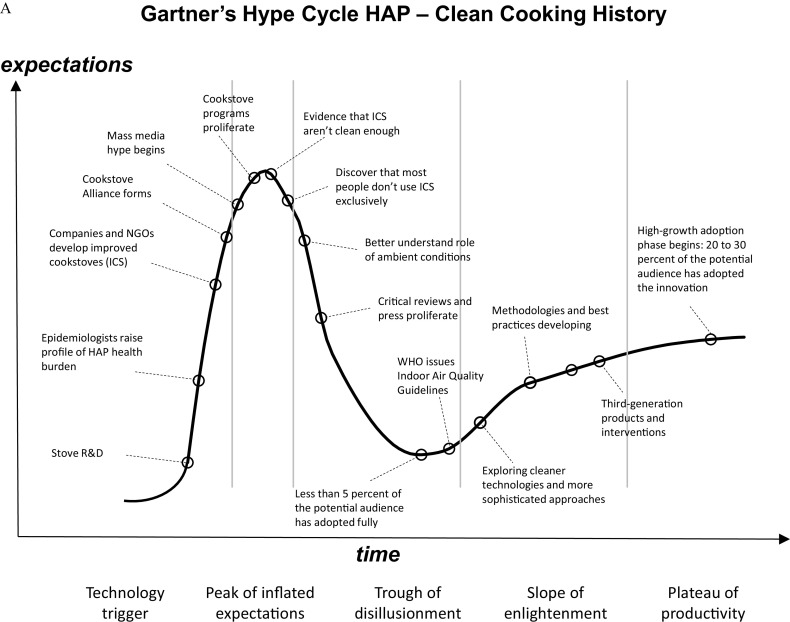

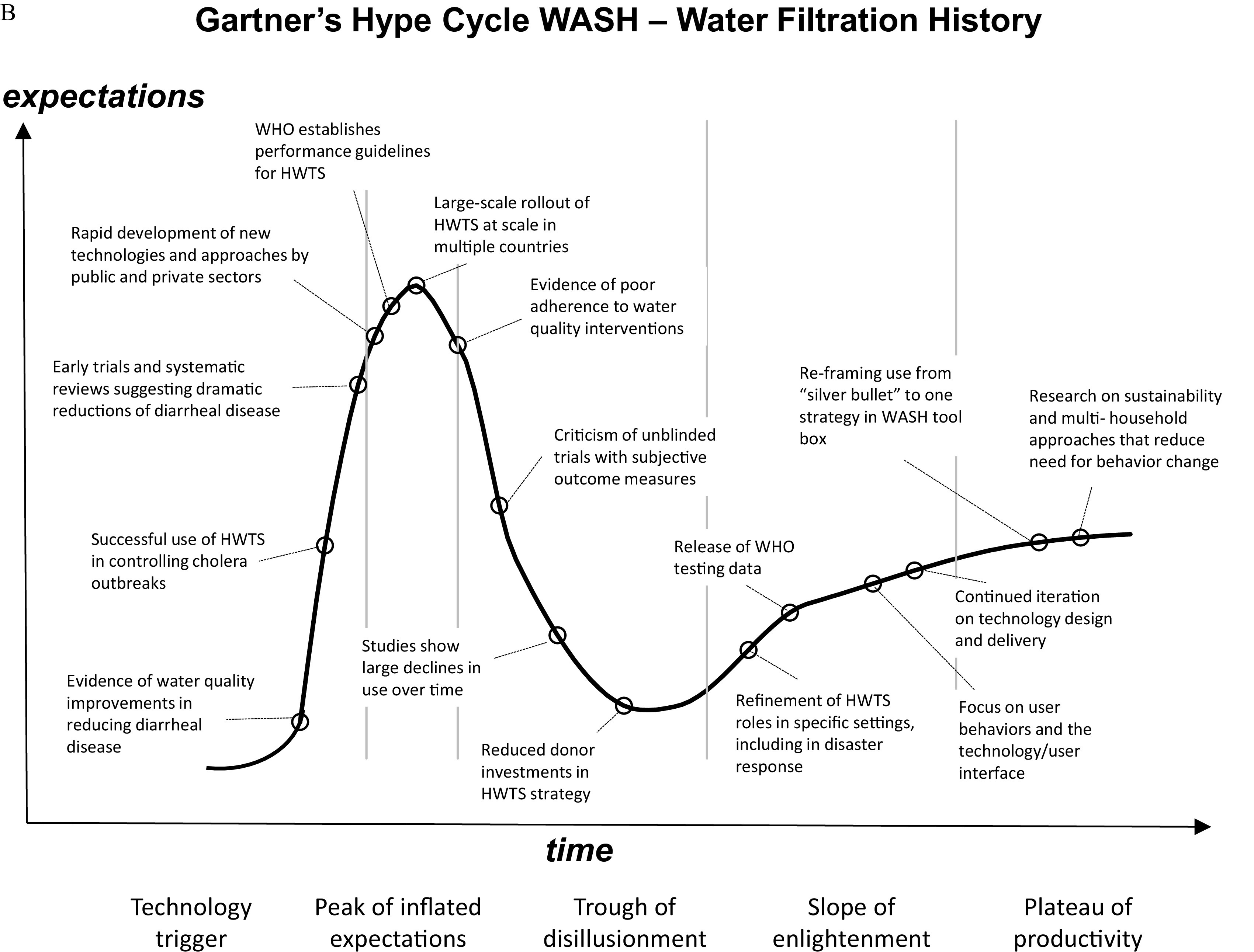

At the policy level, we often see a pattern of initial success, excitement, and hype around a potentially effective intervention, followed by real-world failures or shortfalls and subsequent loss of political and financial support to the next big thing. Even potentially important interventions are often rolled out before there is sufficient evidence to guide them, and a wave of premature enthusiasm and associated financing effectively set them up for failure (Little et al. 2012). Clean cooking and water filtration interventions illustrate this pattern elegantly. Gartner’s Hype Cycle (Fenn and Raskino 2008) is a widely employed conceptual tool from the technology business community to describe and predict the path of development to establishment of a new technology in industry. In Figure 1 we map the history of HAP and WASH interventions onto Gartner’s Hype Cycle to illustrate how a similar pattern has unfolded in the environmental health intervention science and policy communities.

Figure 1.

(A) Household air pollution (HAP)—clean cookstove history mapped onto Gartner’s Hype Cycle (adapted from Fenn and Raskino 2008). (B) Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)—point-of-use water treatment history mapped onto Gartner’s Hype Cycle (adapted from Fenn and Raskino 2008). Note: HWTS, household water treatment and safe storage; NGO, nongovernmental organization; R&D, research and development; WHO, World Health Organization.

The clean cooking movement received new impetus and rapid increases in investment beginning in 2010 when the HAP disease burden was recognized, and improved cookstoves were perceived by the policy community to offer win-win-win solutions for health, climate, and women’s empowerment (Bhattacharyya and Light 2010). As the scientific and development communities gradually uncovered significant shortcomings in cookstove programs enthusiasm began to wane and international funding for this work declined precipitously (Figure 1A). Today, some believe that we may have lost important momentum because of these incautious efforts (Ezzati and Baumgartner 2017). Ironically, this has occurred as the field is maturing scientifically and greater understanding of what benefits are achievable as well as a greatly improved understanding of the socioeconomic and environmental conditions for successful and sustainable interventions are accruing rapidly.

Parallels in WASH include household water filtration technology (Figure 1B) and community-led total sanitation (CLTS), both potentially transformative interventions initially supported by substantial research and programmatic efforts, only to have rigorous trial results reveal limitations to the approaches (Brown et al. 2019). Enthusiasm for household-level chlorination has been tempered by challenges in supply chains, low adoption, and new evidence on the prevalence of chlorine-resistant diarrheagenic agents such as Cryptosporidium (Kotloff et al. 2019). The fact that interventions may not live up to the initial hype should not mask the real benefits such solutions can deliver: for example, household water treatment technologies have shortcomings, but systematic reviews of the evidence base reveal the approach’s potential as an interim solution that can improve water quality and reduce diarrheal disease in vulnerable populations (Clasen et al. 2015).

Whether intervention shortfalls are due to efficacy, effectiveness, implementation challenges, or changes to underlying enabling conditions, failures may result in enormous social and financial costs. Before the Clean Cooking Alliance focused their efforts toward clean fuels, approximately 40 million homes received improved stoves (ISO tiers 1–2) (Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves 2017) for which there is little to no evidence of health benefits (although some reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, quantity of fuel used, and time spent collecting fuels are possible). Worse are projects that have led to large negative unintended consequences, usually due to incomplete knowledge about the context. A tragic example is the arsenic poisoning epidemic in Bangladesh that resulted from a decades-long program to reduce diarrheal disease by installing tube wells into naturally contaminated soil strata (AH Smith et al. 2000). A consequence is that today populations in Bangladesh are still grappling with diarrheal disease from exposure to contaminated surface water, simultaneous with poisoning from exposure to arsenic from tube wells (Yunus et al. 2016) and social conflict regarding access to safe water (Sultana 2011).

What Implementation Science Offers

Implementation science (IS) is a relatively new field that provides a set of theoretical, analytical, and experimental methods to understand the processes that make interventions successful and sustainable in service delivery programs at scale and over time (Colditz and Emmons 2019; Glasgow et al. 2004; Madon et al. 2007; Rosenthal et al. 2017; Yamey 2011). The field draws on conceptual frameworks that focus analysis on those types of organizational and community processes that are required for broad and sustained uptake of new evidence-based programs and policies (Damschroder et al. 2009; Tabak et al. 2012). Increasingly, implementation science frameworks are linked to RCTs that aim to evaluate hypotheses regarding the importance of specific approaches to, for example, individual or household behavior change, or adoption of an intervention by institutions in a given setting (Curran et al. 2012).

The ability to understand the aspects of programs that enable successful transfer from one setting to another is a key component of successful implementation at scale. Because multisite RCTs are expensive, programs are sometimes launched based on efficacy studies or limited range effectiveness trials (Madon et al. 2007) without examining implementation variables such as context-specific adoption or maintenance needs that may be critical to the success of the intervention. The implicit assumption in these cases is that future projects can invest in adapting effective interventions to new conditions elsewhere in the world. Implementation research uncovers factors that may be influential to success by offering experimental and analytical frameworks to systematically consider and evaluate individual and institutional behaviors and environmental variables that are often obscured or assumed to be constant (Glasgow et al. 1999; Rosenthal et al. 2017).

Systems Science Expands Implementation Science Approaches

Systems science offers powerful, underused tools to develop lessons for intervention design and implementation in both HAP and WASH. Broadly speaking, systems science is the application of scientific methods to the understanding of complex systems (Galea et al. 2010). Systems science has been embraced by some in the implementation science community because of its utility to describe, analyze, and simulate complex systems that defy traditional methods (Burke et al. 2015; Hammond and Dubé 2012). Importantly, systems science does not make an a priori commitment that all phenomena are best understood in terms of systems. Rather, it provides tools for consideration of phenomena that may not be amenable to analyses focusing on decomposed system elements and their properties. Challenges to implementing and sustaining evidence-based interventions, are often systemic in nature and, thus, systems science methods may offer much promise (Luke et al. 2018).

System science methods include a variety of tools that generally fall under the following categories: network analysis (NA), system dynamics (SD), agent-based modeling (ABM), and in some cases Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Some of these methods are more descriptive and oriented toward statistical analysis and visualization of data (e.g., network analysis, geographic information systems), whereas others are more focused on theory development and computational modeling (e.g., system dynamics, agent-based modeling) (Table 1). The use of GIS is already well developed in the environmental health community (see, e.g., Nuckols et al. 2004; Peng et al. 2018). Here, we focus primarily on opportunities for advancing HAP and WASH with three modeling approaches, network analysis, system dynamics, and agent-based modeling. In Table 1 and the following paragraphs we provide a brief description of each of these methods and references for more detailed information.

Table 1.

Three systems science tools.

| Tool | Focus | Key strengths | Source data | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network analysis (NA) | Relationships between actors | Visualization; identification of structure in social systems; can be empirical or model based | Surveys, observations, administrative data (e.g., membership rosters, emails), social media data | Luke and Harris 2007; Valente 2010, 2012 |

| System dynamics (SD) | Dynamic behavior generated by an explicit set of feedback mechanisms over time | Identifying endogenous sources of dynamic behavior in a set of feedback loops; ability to identify key leverage points for system interventions | Time series to establish empirical basis for reference modes; empirical research results that provide estimates for model parameters and initial conditions; key informant interviews, direct observation, group model building, expert panels, and grounded theory approaches to qualitative data analysis for structural relationships | Rahmandad et al. 2015; Sterman 2018 |

| Agent-based modeling (ABM) | Emergent patterns from interaction of actors with structured exposures | Ability to examine interaction of individual or groups of actors with each other and with their social and physical environments; can deal with actor and environmental heterogeneity | ABMs can take advantage of all of the data sources mentioned for NA and SD. For example, theories can be used to design agent rules; empirical data can be used to characterize agents and their physical/social environments | Epstein 2007 |

Network analysis focuses on the relationships among sets of actors. The actors can be any type of entity that can have a relationship or tie with others: point sources, persons, animals, organizations, countries, websites, documents, and even genes. These networks provide information on social structure that can play an important role in either promoting or mitigating disease processes. Almost all NA makes use of one or more of three different analytic modes: network visualization, network description, and statistical modeling of networks.

System dynamics (SD) is based on the idea that system behavior (e.g., the frequency of exposures over continuous time) results from the interplay of a set of feedback mechanisms or loops relating accumulations and their corresponding rates of change or flows. Models of the feedback system can be described informally using a series of causal diagrams or more formally as a system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations that can be simulated on a computer. System behavior is then explained in terms of an explicit set of balancing and reinforcing feedback loops, whether that is at an aggregate, individual, or multilevel system (Richardson 2020; Sterman 2018). The visual conventions of SD (e.g., casual loop diagrams, stock and flow diagrams) have evolved into a set of participatory methods for involving communities and other stakeholders in the process of conceptualizing, formulating, and analyzing the results of models called group model building (e.g., Hovmand 2014; Richardson and Andersen 1995; Vennix 1996).

Agent-based modeling (ABM) uses computer simulation to study complex systems from the ground up, by analyzing how individual elements of a system (agents) behave as a function of individual properties, their environment, and their interactions with each other. Through these behaviors, emergent properties of the overall system are revealed. Compared with SD, this results in a form of decentralized modeling where there is no formalized definition of global system behavior; that is, feedback mechanisms are implicit (vs. explicit in SD) and emerge through the interaction of agents within their environment.

Transparency and replicability remain cornerstones of science, and systems science tools are no exception (Barton et al. 2020). In principle, computational models used in systems science (e.g., system dynamics and agent-based modeling) offer an added level of transparency relative to more traditional statistical approaches by making assumptions fully explicit (e.g., as a set of differential equations or programming code) that can be independently explored and modified to test the implications of assumptions, measurement errors, research designs, and so on through sensitivity analysis. This has the advantage over traditional statistical approaches in that one can explore the robustness of a policy to system states beyond what has been historically observed or collected as part of an experiment—something that is highly relevant when we consider structural changes in environmental health triggered by global trends such as climate change, pandemics, and forced displacement of populations due to conflict and environmental disasters. However, this potential to be more transparent is often lost when computational models become overly complicated, lack adequate documentation, or require computational resources with limited access (Meadows and Robinson 1985; Pilkey and Pilkey-Jarvis 2007). A number of standards have, therefore, emerged for reporting guidelines (e.g., Caro et al. 2012; Rahmandad and Sterman 2012).

Although applications of systems approaches are growing in other health implementation arenas, to date, systems applications in environmental health have been limited. Eisenberg et al. (2012) reviewed the history of diarrheal disease research and identified how systems approaches would be helpful in understanding interdependencies across multiple enteric disease transmission pathways. Zelner et al. (2012) used network analysis to understand connectedness between and within communities in relation to reported diarrheal events and found that high connectedness between communities enhances risk of disease, as expected. However, high connectedness within a community reduces risk of diarrheal disease. More recently, scientists applied systems approaches to understand user behavior in relation to interventions. For example, Kumar et al. (2017) have examined behavioral dynamics at the community scale to understand the process of adopting of LPG cooking, and Chalise et al. (2018) analyzed abandonment of biogas digesters and their stoves.

Systems science methods applied to environmental health can be useful for:

Enhancing understanding of existing system structures and behaviors—and the types of feedback mechanisms causing those behaviors—that can accelerate or impede environmental health aims, including potential unintended consequences.

Developing understanding and agreement on a problem among stakeholders, which is particularly important for WASH and HAP because of their dependence on numerous stakeholders at the household, community, and policy maker levels. Group model building, for example, can help bring the diversity of choices and associated tradeoffs among relevant stakeholders to the surface, and can facilitate decision-making.

Guiding intervention and policy formulation, where simulations can be particularly useful to estimate the effects of interventions before attempting them at scale in populations, potentially sidestepping some of the significant economic and social costs of testing the interventions in situ. For example, Mellor et al. (2014) simulated a water filter intervention to predict sustainability of effectiveness in reducing diarrheal incidence.

If systems approaches are developed in an iterative participatory process that engages study populations, policy makers, and implementers, they help ensure that research is responsive to local priorities and reflects real-world conditions, making research a more co-creative and less an extractive process (Dilling and Lemos 2011; Eisenberg et al. 2012; Israel et al. 2005; Mauser et al. 2013).

When a model fails to generate the expected outcomes, this can be due to faulty data or model structure. Faulty data are due to measurement error, either systematic or random. Faulty model structure is due to building a model incorrectly (discovered through verification testing) or building a model of a theory correctly, but based on a theory that is faulty (discovered through validation testing). Weak measurement models, verification testing, or validation testing can contribute to a false confidence in a model of a system. A strong program of validating measurements and verifying that a model has been built correctly can, however, falsify a theory. In doing so, a model can typically be advanced that can offer a stronger alternative explanation for emergent behavior of a system. In either case (whether discovering and correcting measurement errors and specification errors or advancing a stronger alternative explanation), the process is consistent with a progressive program of scientific research (Lakatos 1970).

Some Suggested Applications of Systems Science to HAP and WASH Problems

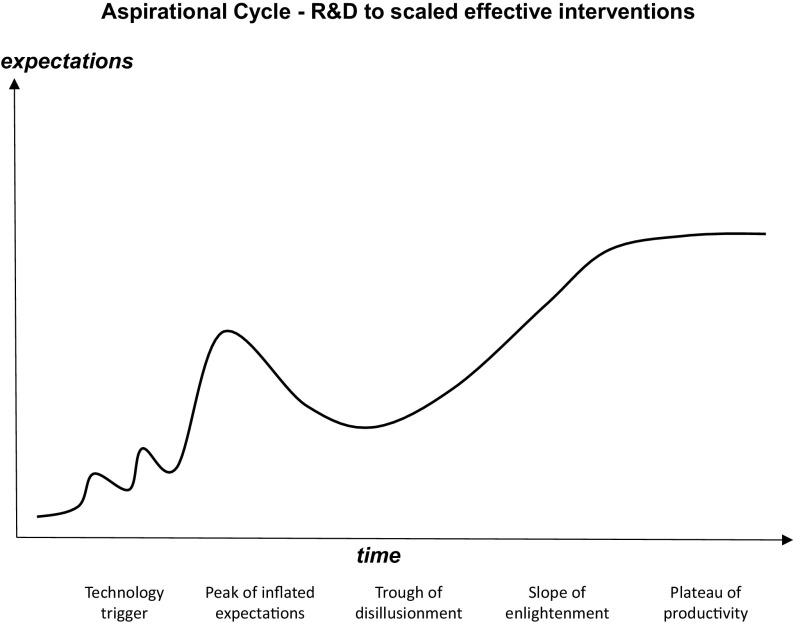

An important goal for the application of systems science in the fields of HAP and WASH is to accelerate learning and flatten the Hype Cycle (Figure 2) to achieve steadier gains in health outcomes. This might be characterized as accelerating the pace of innovation, partly through failing fast or quickly identifying strategies that may not result in changes in exposure. Using systems approaches in the early design and planning stages of a WASH or HAP interventional program can help scientists and policy-makers think more clearly about the larger socioeconomic and environmental context in which disease occurs and about how innovations may work at the development, intervention, program, and sustainment stages over time. In this way, we would hope to head off many pitfalls, reduce the temporal and financial costs of failed trials and interventions, and achieve public health impacts more reliably.

Figure 2.

Aspirational (flattened hype) cycle that accelerates research, development, and scale-up successes of effective environmental health interventions employing systems science methods in the context of implementation science (hypothetical curve). Note: R&D, research and development.

Below are examples of topics in which systems methods might be applied productively to complex questions in WASH and HAP.

Behavioral adherence requirements: Behavioral data—such as from stove use and water filter use monitors—is increasingly integrated into intervention deployment, behavior monitoring, and exposure assessment efforts. These rich, time-series data could be combined with network analysis and agent-based models (Ginexi et al. 2014) to help predict the effects of a program roll out on exposure for different levels of adherence to a HAP or WASH intervention. In this way, investigators could examine their assumptions and identify potential challenges prior to large-scale and expensive exposure and health assessments. Several investigators have done work in this area using quantitative microbial risk assessment (Hayashi et al. 2019).

Community engagement and design: Community engagement is widely understood to be important for acceptability and sustainability of an intervention (Israel et al. 2005). It is especially important when complex individual behaviors have either social or exposure spillover effects on other households. Incorporating community-based system dynamics (Hovmand 2014) or another form of group model building in designing a community-based WASH intervention can be extremely useful to identify critical behaviors and develop a consensus understanding of how the sanitation and hygiene practices of one group affects others. An intervention that emerges from this process is much more likely to be sustained and enforced by the community members individually not only because of acceptability borne of community participation but also because it is more likely to have correctly identified local facilitators and barriers to implementation (Powell et al. 2017).

Predicting effectiveness: Sanitation interventions aim to interrupt transmission of specific enteric infections, but threshold effects reflecting herd immunity can be important mediators of benefits (Fuller and Eisenberg 2016). An analog in HAP interventions would be the question of thresholds for coverage in community-scale programs that reduce ambient pollution sufficiently to yield health benefits for the population. In the sanitation–infection domain, these thresholds have been explored with transmission models in a variety of contexts including drinking water. Population-scale models can be developed using system dynamics tools that force investigators to specify their mechanistic assumptions and to investigate how changing these assumptions around exposures, intervention coverage, and adherence might impact disease incidence. These can be also be linked to networks to evaluate how different features of community structure affect outcomes.

Dissemination/diffusion of interventions: Behaviors, including the adoption of new HAP and WASH technologies, often diffuse through communities through social connections and word of mouth (Rogers 2003; Valente et al. 2015). Social network analysis helps elucidate the underlying structure of social ties and could be useful in determining the patterns of information transfer in a community that will influence the adoption and use of an environmental health technology. Understanding the underlying social network structure, moreover, could shed light on potential interventions that could act through social networks to influence adoption and use. For example, social ties could be used to leverage group incentives for sustained use of LPG cooking (where each member of a group receives the incentive only if all members demonstrate the desired behavior) or to identify well-connected influencers who might be good targets for marketing and outreach efforts.

Emergent patterns from individual variation: Fuel and stove stacking is ubiquitous in clean cooking programs, and yet we have a limited understanding of the choices people will make when multiple clean and traditional cooking options are available. Moreover, population-scale exposure results from hundreds of thousands of individual choices. Individual (agent-based) models based on survey data of the diverse choices people have made and their socioeconomic and environmental covariates may offer opportunities to explore what will happen at scale in relation to diverse influences, as well as the relative strength of these influences on outcomes.

Scale-up, bottlenecks, and delays: Advanced gasifier stoves fueled by compressed wood pellets show promise as a clean cooking technology for both health- and climate-related objectives (Champion and Grieshop 2019). These stove/fuel combinations are being explored in development programs and commercial projects, but the technology faces significant challenges in scale-up and maintenance over time because of feedstock supply, pellet production, distribution, and costs to end users (Jagger and Das 2018). If enough demand is generated, stress to multiple points in the supply chain is likely to emerge and this could in turn dampen demand or create a new problem with unlawful harvesting of trees for feedstock. System dynamics models are particularly well suited to this type of problem because they allow us to model complex conditions and time delays across a wide variety of factors, including policy, economic, social, and physical variables and then to see how these play out over time in a given setting through simulation.

Sustaining interventions: System science approaches are essential to understand and solve implementation problems that result from feedback between technologies, social and cultural norms, and livelihood options that are nonlinear and dynamic. Chalise et al. (2018) identified such feedback mechanisms in sustained use of improved biogas stoves in two communities; one community that sustained high levels of exclusive biogas use and an adjacent community that largely abandoned the technology. Using qualitative group model building and subsequent system dynamics simulation they traced the community interactions that led to solutions for technical and maintenance problems with fuel digesters and thus increased use of the cleaner technology in the one community, compared with frustration and abandonment by the other. The group model building and simulation highlight multiple household, technical, and social factors that are interlinked in a feedback structure and cannot be fully understood in isolation.

Adaptability to environmental change: Behaviors and associated technologies that may function well in avoiding or mitigating environmental health challenges today may change quickly or lag in their ability to adapt to future changes. Climate change raises a host of challenges for WASH programs, in particular, and many of these are influenced by social context. Cherng et al. (2019) illustrated the use of social networks in Ecuadorian communities to measure social cohesion across safe water sourcing practices, and agent-based models to understand how these structured communities will be able to adapt under changing flooding and drought conditions.

How to Approach Systems Modeling Productively in Environmental Health

Environmental health scientists are increasingly turning from assessing risks to designing and testing interventions. Research outcomes can catalyze programs and policies that operate at large spatial scales, and as in HAP and WASH, with great dependence on individual and community behaviors, it behooves us to approach interventions with an appreciation of the complexity of these systems. Environmental health research provides rigorous methodologies and a wide variety of large data sets from both interventional and observational studies on population-based exposures, behaviors, and correlated health outcomes. Combining rich data sources with systems modeling may be especially productive to explore the sensitivity of hoped-for outcomes to assumptions regarding implementation variables such as household, community, or institutional adoption and adherence. This may also help us consider potential effects of adapting effective interventions to locally important contextual variables such as other exposure sources, cost constraints, policy, and infrastructure influences.

As in any interdisciplinary team, depth in both analytical methods and the environmental health challenge is necessary for success. System scientists come from diverse backgrounds, including sociology, ecology, physics, operations research, management, engineering, public health, and computer science, to name a few. Spending time at the outset of a collaboration between environmental health, systems scientists, and where relevant, policy experts, is critical to familiarizing one another with basic concepts and terminology in their respective fields and to agreeing on the aims, value, and limitations of various approaches.

For the systems science community, it is important to recognize that most environmental health scientists are trained to undertake population-based risk assessments using inferential statistics. Systems approaches often include expert opinion, key informant inputs, or other soft evidence in addition to experimental results to parameterize a working model. Furthermore, systems modeling is often conducted with significant data gaps [indeed, this can be a primary reason for undertaking such modeling, see Wallace et al. (2015)]. Significant discussions at the outset may be necessary to ensure that environmental health scientists understand and are comfortable with the approach.

For environmental health scientists, it may be useful to approach systems modeling as a means of exploring and testing their own assumptions. We recommend, where possible, an iterative process including participatory or co-creative activities to frame questions, conceptualizing an initial model, collecting data to parameterize it, evaluating model output in relation to observations, improving the model, and then testing interventions in silico before beginning larger population-based studies. Such approaches can allow for evaluation of the plausibility of health effects via changes in exposure at levels that may be health-relevant—before undertaking large trials using distal outcomes. Engagement with social, behavioral, and political scientists in the conceptualization, parameterization, and analysis of systems models can be important to avoid the omission of critical sociodemographic, economic, institutional, and macro-level processes that shape implementation. Participatory methods, such as group model building, may be particularly useful, especially with community-based research activities.

There are a variety of ways to build an interdisciplinary team that include systems scientists within the constraints of project budgets. At the most basic level, integrating systems modeling into environmental health research can be done by bringing a single experienced systems modeler into a project at the design stage and continuing through analyses and interpretation of results. At this level, the additional expertise may not be a large cost burden for a project, and it could conceivably fit within, for example, a National Institutes of Health R21 exploratory grant designed to assess basic feasibility of an intervention. Of course, modelers may raise questions that require new data, including, for example, relationships between community members, expectations of policy-makers, or economic influences. Modelers may also suggest participatory processes, surveys, and focus group exercises that the environmental health researchers did not anticipate. These in turn may require engagement of more disciplinary expertise or significant computational coding time and, thus, further expansion of the team to the R01 or larger level. However, one of the strengths of modeling generally is the ability to work within the constraints posed by the available data by drawing on a variety of existing or easily acquired sources to parameterize factors that may be especially challenging to estimate from what can be collected within a given project. The key here is understanding which factors require greater certainty for a given question and end-use plan, and which factors may allow for greater uncertainty.

Summary and Conclusion

Systems science approaches offer important and underexploited tools for environmental health, especially in complex environments that change over time. We work in a time of rapid innovation and with a public health policy community that increasingly seeks evidence to support decision-making. Both observational and experimental studies in environmental health generate large data sets that can be used in both a priori and post hoc systems modeling. These data have often been gathered using extended, multiyear efforts, often with high collection costs. Increased use of systems modeling in implementation research for environmental health may offer cost-effective approaches with both heuristic value and practical output to improve design and deployment of interventions to improve public health. HAP and WASH science are particularly suitable to systems modeling given the complexity of the socioeconomic and environmental contexts that often regulate their effectiveness, implementability, and scale-up potential. Many other environmental health interventions may also benefit from their use. Increased collaboration among systems and environmental health scientists has the potential to accelerate lessons and flatten the Hype Cycle that slows and sometimes dooms promising interventions for public health before we understand their potential.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the NIH Common Fund’s Global Health program for the Clean Cooking Implementation Science Network and from the Boston College School of Social Work enabled the 2018 workshop where these ideas were initially developed. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. National Institutes of Health or Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- Alexander D, Northcross A, Wilson N, Dutta A, Pandya R, Ibigbami T, et al. 2017. Randomized controlled ethanol cookstove intervention and blood pressure in pregnant Nigerian women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195(12):1629–1639, PMID: 28081369, 10.1164/rccm.201606-1177OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain R, Cronk R, Hossain R, Bonjour S, Onda K, Wright J, et al. 2014. Global assessment of exposure to faecal contamination through drinking water based on a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 19(8):917–927, PMID: 24811893, 10.1111/tmi.12334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton CM, Alberti M, Ames D, Atkinson J-A, Bales J, Burke E, et al. 2020. Call for transparency of COVID-19 models. Science 368(6490):482–483, PMID: 32355024, 10.1126/science.abb8637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendes DM, Yang PJ, Lai A, Hu D, Brown J. 2018. Estimation of global recoverable human and animal faecal biomass. Nat Sustain 1(11):679–685, 10.1038/s41893-018-0167-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya A, Light A. 2010. United States joins alliance to promote clean cooking in developing countries. Center for American Progress. 22 September 2010. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/green/news/2010/09/22/8353/united-states-joins-alliance-to-promote-clean-cooking-in-developing-countries/ [accessed 15 July 2020].

- Bivins A, Sumner T, Kumpel E, Howard G, Cumming O, Ross I, et al. 2017. Estimating infection risks and the global burden of diarrheal disease attributable to intermittent water supply using QMRA. Environ Sci Technol 51(13):7542–7551, PMID: 28582618, 10.1021/acs.est.7b01014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Albert J, Whittington D. 2019. Community-led total sanitation moves the needle on ending open defecation in Zambia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 100(4):767–769, PMID: 30860017, 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Clasen T. 2012. High adherence is necessary to realize health gains from water quality interventions. PLoS One 7(5):e36735, PMID: 22586491, 10.1371/journal.pone.0036735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge M. 1997. Mechanism and explanation. Philos Soc Sci 27(4):410–465, 10.1177/004839319702700402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JG, Lich KH, Neal JW, Meissner HI, Yonas M, Mabry PL. 2015. Enhancing dissemination and implementation research using systems science methods. Int J Behav Med 22(3):283–291, PMID: 24852184, 10.1007/s12529-014-9417-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett RT, Pope CA III, Ezzati M, Olives C, Lim SS, Mehta S, et al. 2014. An integrated risk function for estimating the global burden of disease attributable to ambient fine particulate matter exposure. Environ Health Perspect 122(4):397–403, PMID: 24518036, 10.1289/ehp.1307049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt EW, Rap A, Schmidt A, Scott CE, Pringle KJ, Reddington CL, et al. 2016. The impact of residential combustion emissions on atmospheric aerosol, human health, and climate. Atmos Chem Phys 16(2):873–905, 10.5194/acp-16-873-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capra F, Luisi PL. 2014. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caro JJ, Briggs AH, Siebert U, Kuntz KM, ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force. 2012. Modeling good research practices—overview: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-1. Value Health 15(6):796–803, PMID: 22999128, 10.1016/j.jval.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalise N, Kumar P, Priyadarshini P, Yadama GN. 2018. Dynamics of sustained use and abandonment of clean cooking systems: lessons from rural India. Environ Res Lett 13(3):03510, 10.1088/1748-9326/aab0af. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Champion WM, Grieshop AP. 2019. Pellet-fed gasifier stoves approach gas-stove like performance during in-home use in Rwanda. Environ Sci Technol 53(11):6570–6579, PMID: 31037940, 10.1021/acs.est.9b00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherng ST, Cangemi I, Trostle JA, Remais JV, Eisenberg JNS. 2019. Social cohesion and passive adaptation in relation to climate change and disease. Glob Environ Change 58:101960, PMID: 32863604, 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Chafe ZA, Pillarisetti A, Lelieveld J, Guttikunda S, Dey S. 2019a. The contribution of household fuels to ambient air pollution in India—a comparison of recent estimates. New Delhi, India: Collaborative Clean Air Policy Centre; https://ccapc.org.in/policy-briefs/2019/5/30/the-contribution-of-household-fuels-to-ambient-air-pollution-in-india-a-comparison-of-recent-estimates [accessed 15 July 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Dey S, Guttikunda S, Pillarisetti A, Smith KR, Di Girolamo L. 2019b. Indian annual ambient air quality standard is achievable by completely mitigating emissions from household sources. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116(22):10711–10716, PMID: 30988190, 10.1073/pnas.1900888116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasen T, Boisson S, Routray P, Torondel B, Bell M, Cumming O, et al. 2014. Effectiveness of a rural sanitation programme on diarrhoea, soil-transmitted helminth infection, and child malnutrition in Odisha, India: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health 2(11):e645–e653, PMID: 25442689, 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasen T, Smith KR. 2019. Let the “A” In WASH stand for air: integrating research and interventions to improve household air pollution (HAP) and water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) in low-income settings. Environ Health Perspect 127(2):25001, PMID: 30801220, 10.1289/EHP4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasen TF, Alexander KT, Sinclair D, Boisson S, Peletz R, Chang HH, et al. 2015. Interventions to improve water quality for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(10):CD004794, PMID: 26488938, 10.1002/14651858.CD004794.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey ER, Muvandimwe D, Hagar Y, Wiedinmyer C, Kanyomse E, Piedrahita R, et al. 2017. New emission factors and efficiencies from in-field measurements of traditional and improved cookstoves and their potential implications. Environ Sci Technol 51(21):12508–12517, PMID: 29058409, 10.1021/acs.est.7b02436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, Emmons KM. 2019. The promise and challenges of dissemination and implementation research. In: Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health. Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, eds. 2nd ed Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Conibear L, Butt EW, Knote C, Arnold SR, Spracklen DV. 2018. Residential energy use emissions dominate health impacts from exposure to ambient particulate matter in India. Nat Commun 9(1):617, PMID: 29434294, 10.1038/s41467-018-02986-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. 2012. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 50(3):217–226, PMID: 22310560, 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie DJ, Smith C, Jagals P. 2018. The application of system dynamics modelling to environmental health decision-making and policy—a scoping review. BMC Public Health 18(1):402, PMID: 29587701, 10.1186/s12889-018-5318-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler D, Miller G. 2005. The role of public health improvements in health advances: the twentieth-century United States. Demography 42(1):1–22, PMID: 15782893, 10.1353/dem.2005.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. 2009. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 4:50, PMID: 19664226, 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangour A, Watson L, Cumming O, Boisson S, Che Y, Velleman Y, et al. 2013. Interventions to improve water quality and supply, sanitation and hygiene practices, and their effects on the nutritional status of children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(8):CD009382, PMID: 23904195, 10.1002/14651858.CD009382.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels ME, Smith WA, Schmidt W-P, Clasen T, Jenkins MW. 2016. Modeling Cryptosporidium and Giardia in ground and surface water sources in rural India: associations with latrines, livestock, damaged wells, and rainfall patterns. Environ Sci Technol 50(14):7498–7507, PMID: 27310009, 10.1021/acs.est.5b05797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvesh N, Das JK, Vaivada T, Gaffey MF, Rasanathan K, Bhutta ZA, et al. 2017. Water, sanitation and hygiene interventions for acute childhood diarrhea: a systematic review to provide estimates for the Lives Saved Tool. BMC Public Health 17(suppl 4):776, PMID: 29143638, 10.1186/s12889-017-4746-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilling L, Lemos MC. 2011. Creating usable science: opportunities and constraints for climate knowledge use and their implications for science policy. Glob Environ Change 21(2):680–689, 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eilenberg SR, Bilsback KR, Johnson M, Kodros JK, Lipsky EM, Naluwagga A, et al. 2018. Field measurements of solid-fuel cookstove emissions from uncontrolled cooking in China, Honduras, Uganda, and India. Atmos Environ 190:116–125, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.06.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg JNS, Cevallos W, Ponce K, Levy K, Bates SJ, Scott JC, et al. 2006. Environmental change and infectious disease: how new roads affect the transmission of diarrheal pathogens in rural Ecuador. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103(51):19460–19465, PMID: 17158S216, 10.1073/pnas.0609431104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg JNS, Scott JC, Porco T. 2007. Integrating disease control strategies: balancing water sanitation and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrheal disease burden. Am J Public Health 97(5):846–852, PMID: 17267712, 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg JNS, Trostle J, Sorensen RJD, Shields KF. 2012. Toward a systems approach to enteric pathogen transmission: from individual independence to community interdependence. Annu Rev Public Health 33:239–257, PMID: 22224881, 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enger KS, Nelson KL, Rose JB, Eisenberg JNS. 2013. The joint effects of efficacy and compliance: a study of household water treatment effectiveness against childhood diarrhea. Water Res 47(3):1181–1190, PMID: 23290123, 10.1016/j.watres.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JM. 2007. Generative Social Sciences: Studies in Agent-Based Computation Modeling. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Esrey SA, Feachem RG, Hughes JM. 1985. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: improving water supplies and excreta disposal facilities. Bull World Health Organ 63(4):757–772, PMID: 3878742. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esrey SA, Potash JB, Roberts L, Shiff C. 1991. Effects of improved water supply and sanitation on ascariasis, diarrhoea, dracunculiasis, hookworm infection, schistosomiasis, and trachoma. Bull World Health Organ 69(5):609–621, PMID: 1835675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Baumgartner JC. 2017. Household energy and health: where next for research and practice? Lancet 389(10065):130–132, PMID: 27939060, 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn J, Raskino M. 2008. Mastering the Hype Cycle: How to Choose the Right Innovation at the Right Time. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman MC, Clasen T, Dreibelbis R, Saboori S, Greene LE, Brumback B, Muga R, Reingans R. 2014. The impact of a school-based water supply and treatment, hygiene, and sanitation programme on pupil diarrhoea: a cluster-randomized trial. Epidemiol Infect 142(2):340–351, PMID: 23702047, 10.1017/S0950268813001118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller JA, Eisenberg JNS. 2016. Herd protection from drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions. Am J Trop Med Hyg 95(5):1201–1210, PMID: 27601516, 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Riddle M, Kaplan GA. 2010. Causal thinking and complex system approaches in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 39(1):97–106, PMID: 19820105, 10.1093/ije/dyp296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2016 Risk Factors Collaborators. 2017. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390:1345–1422, PMID: 28919119, 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32366-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginexi EM, Riley W, Atienza AA, Mabry PL. 2014. The promise of intensive longitudinal data capture for behavioral health research. Nicotine Tob Res 16(suppl 2):S73–S75, PMID: 24711629, 10.1093/ntr/ntt273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Estabrooks P. 2004. The future of health behavior change research: what is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Ann Behav Med 27(1):3–12, PMID: 14979858, 10.1207/s15324796abm2701_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. 1999. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 89(9):1322–1327, PMID: 10474547, 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves. 2017. Clean Cooking: Key to Achieving Global Climate and Development Goals, 2016 Progress Report. Washington, DC: Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves; https://www.cleancookingalliance.org/binary-data/RESOURCE/file/000/000/495-1.pdf [accessed 15 July 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond RA, Dubé L. 2012. A systems science perspective and transdisciplinary models for food and nutrition security. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(31):12356–12363, PMID: 22826247, 10.1073/pnas.0913003109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi MAL, Eisenberg MC, Eisenberg JNS. 2019. Linking decision theory and quantitative microbial risk assessment: tradeoffs between compliance and efficacy for waterborne disease interventions. Risk Anal 39(10):2214–2226, PMID: 31529800, 10.1111/risa.13381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovmand PS. 2014. Community Based System Dynamics. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Baumgartner J, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Schauer JJ. 2015. Source apportionment of air pollution exposures of rural Chinese women cooking with biomass fuels. Atmos Environ 104:79–87, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.12.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey JH, Mbuya MNN, Ntozini R, Moulton LH, Stoltzfus RJ, Tavengwa NV, et al. 2019. Independent and combined effects of improved water, sanitation, and hygiene, and improved complementary feeding, on child stunting and anaemia in rural Zimbabwe: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health 7(1):e132–e147, PMID: 30554749, 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30374-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hystad P, Duong M, Brauer M, Larkin A, Arku R, Kurmi OP, et al. 2019. Health effects of household solid fuel use: findings from 11 countries within the prospective urban and rural epidemiology study. Environ Health Perspect 127(5):57003, PMID: 31067132, 10.1289/EHP3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, Salvatore A, Minkler M, López J, et al. 2005. Community-based participatory research: lessons learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect 113(10):1463–1471, PMID: 16203263, 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger P, Das I. 2018. Implementation and scale-up of a biomass pellet and improved cookstove enterprise in Rwanda. Energy Sustain Dev 46:32–41, PMID: 30449968, 10.1016/j.esd.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger P, Pedit J, Bittner A, Hamrick L, Phwandapwhanda T, Jumbe C. 2017. Fuel efficiency and air pollutant concentrations of wood-burning improved cookstoves in Malawi: implications for scaling-up cookstove programs. Energy Sustain Dev 41:112–120, PMID: 29731584, 10.1016/j.esd.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MA, Chiang RA. 2015. Quantitative stove use and ventilation guidance for behavior change strategies. J Health Commun 20(suppl 1):6–9, PMID: 25839198, 10.1080/10810730.2014.994246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YT, Lou W, Cheng Y-L. 2017. Exposure–response relationship of neighbourhood sanitation and children’s diarrhoea. Trop Med Int Health 22(7):857–865, PMID: 28449238, 10.1111/tmi.12886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotloff KL, Nasrin D, Blackwelder WC, Wu Y, Farag T, Panchalingham S, et al. 2019. The incidence, aetiology, and adverse clinical consequences of less severe diarrhoeal episodes among infants and children residing in low-income and middle-income countries: a 12-month case-control study as a follow-on to the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS). Lancet Glob Health 7(5):e568–e584, PMID: 31000128, 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30076-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Dhand A, Tabak RG, Brownson RC, Yadama GN. 2017. Adoption and sustained use of cleaner cooking fuels in rural India: a case control study protocol to understand household, network, and organizational drivers. Arch Public Health 75:70, PMID: 29255604, 10.1186/s13690-017-0244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos I. 1970. Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programmes. In: Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge. Lakatos I, Musgrave A, eds. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 91–196. [Google Scholar]

- Levy K, Nelson K, Hubbard A, Eisenberg JNS. 2008. Following the water: a controlled study of drinking water storage in northern coastal Ecuador. Environ Health Perspect 116(11):1533–1540, PMID: 19057707, 10.1289/ehp.11296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JJ, Pattanayak SK. 2012. Who adopts improved fuels and cookstoves? A systematic review. Environ Health Perspect 120(5):637–645, PMID: 22296719, 10.1289/ehp.1104194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little M, Kaoukji D, Truesdale B. 2012. Achieving lasting impact at scale. Part two: assessing system readiness for delivery of family health innovations at scale. A convening hosted by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Synthesis and summary by the Social Research Unit at Dartington, UK. https://www.impactstrategist.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Achieving-Lasting-Impact-at-Scale-Part-2.pdf [accessed 15 July 2020].

- Liu J, Kiesewetter G, Klimont Z, Cofala J, Heyes C, Schopp W, et al. 2019. Mitigation pathways of air pollution from residential emissions in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region in China. Environ Int 125:236–244, PMID: 30731373, 10.1016/j.envint.2018.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby SP, Rahman M, Arnold BF, Unicomb L, Ashraf S, Winch PJ, et al. 2018. Effects of water quality, sanitation, handwashing, and nutritional interventions on diarrhoea and child growth in rural Bangladesh: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 6(3):e302–e315, PMID: 29396217, 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30490-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke DA, Harris JK. 2007. Network analysis in public health: history, methods, and applications. Annu Rev Public Health 28(1):69–93, PMID: 17222078, 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke DA, Morshed AB, McKay VR, Combs TB. 2018. Systems science methods in dissemination and implementation research. In: Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, eds. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Luke DA, Stamatakis KA. 2012. Systems science methods in public health: dynamics, networks, and agents. Annu Rev Public Health 33:357–376, PMID: 22224885, 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madon T, Hofman KJ, Kupfer L, Glass RI. 2007. Public health. Implementation science. Science 318(5857):1728–1729, PMID: 18079386, 10.1126/science.1150009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manibog FR. 1984. Improved cooking stoves in developing countries: problems and opportunities. Annu Rev Energy 9(1):199–227, 10.1146/annurev.eg.09.110184.001215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin NA, Hulland KRS, Dreibelbis R, Sultana F, Winch PJ. 2018. Sustained adoption of water, sanitation and hygiene interventions: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 23(2):122–135, PMID: 29160921, 10.1111/tmi.13011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masera OR, Saatkamp BD, Kammen DM. 2000. From linear fuel switching to multiple cooking strategies: a critique and alternative to the energy ladder model. World Dev 28(12):2083–2103, 10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00076-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mauser W, Klepper G, Rice M, Schmalzbauer BS, Hackmann H, Leemans R, et al. 2013. Transdisciplinary global change research: the co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 5(3–4):420–431, 10.1016/j.cosust.2013.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows D, Robinson JM. 1985. The Electronic Oracle: Computer Models and Social Decisions. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor J, Abebe L, Ehdaie B, Dillingham R, Smith J. 2014. Modeling the sustainability of a ceramic water filter intervention. Water Res 49:286–299, PMID: 24355289, 10.1016/j.watres.2013.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens A, Balakrishnan K, Ramaswamy P, Rajkumar P, Ramaprabha P, Durairaj N, et al. 2019. Associations between high temperature, heavy rainfall, and diarrhea among young children in rural Tamil Nadu, India: a prospective cohort study. Environ Health Perspect 127(4):47004, PMID: 30986088, 10.1289/EHP3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobarak AM, Dwivedi P, Bailis R, Hildemann L, Miller G. 2012. Low demand for nontraditional cookstove technologies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(27):10815–10820, PMID: 22689941, 10.1073/pnas.1115571109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer K, Ndamala CB, Naunje AW, Malava J, Katundu C, Weston W, et al. 2017. A cleaner burning biomass-fuelled cookstove intervention to prevent pneumonia in children under 5 years old in rural Malawi (the Cooking and Pneumonia Study): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 389(10065):167–175, PMID: 27939058, 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32507-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuckols JR, Ward MH, Jarup L. 2004. Using Geographic Information Systems for exposure assessment in environmental epidemiology studies. Environ Health Perspect 112(9):1007–1015, PMID: 15198921, 10.1289/ehp.6738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Null C, Stewart CP, Pickering AJ, Dentz HN, Arnold BF, Arnold CD, et al. 2018. Effects of water quality, sanitation, handwashing, and nutritional interventions on diarrhoea and child growth in rural Kenya: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 6(3):e316–e329, PMID: 29396219, 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30005-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil SR, Arnold BF, Salvatore AL, Briceno B, Ganguly S, Colford JM Jr, et al. 2014. The effect of India’s total sanitation campaign on defecation behaviors and child health in rural Madhya Pradesh: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 11(8):e1001709, PMID: 25157929, 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penakalapati G, Swarthout J, Delahoy MJ, McAliley L, Wodnik B, Levy K, et al. 2017. Exposure to animal feces and human health: a systematic review and proposed research priorities. Environ Sci Technol 51(20):11537–11552, PMID: 28926696, 10.1021/acs.est.7b02811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C, den Dekker M, Cardenas A, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gibson H, Agha G, et al. 2018. Residential proximity to major roadways at birth, DNA methylation at birth and midchildhood, and childhood cognitive test scores: project Viva (Massachusetts, USA). Environ Health Perspect 126(9):97006, PMID: 30226399, 10.1289/EHP2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkey OH Jr, Pilkey-Jarvis L. 2007. Useless Arithmetic: Why Environment Scientists Can’t Predict the Future. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, Aarons GA, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. 2017. Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res 44(2):177–194, PMID: 26289563, 10.1007/s11414-015-9475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]