Significance

Neuronal self-avoidance is a conserved process in vertebrates and invertebrates. In Drosophila, self-avoidance is mediated by the Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule (Dscam1) gene that encodes tens of thousands of proteins through alternative splicing. In vertebrates, an analogous function is performed by ∼60 clustered protocadherins (cPcdh) through promoter choice. Here we use cell aggregation assays to study the binding preferences of ∼100 sDscam protein in scorpion. We report that while related in sequence to the fly Dscam, the scorpion sDscam adopts a strategy that is similar to that of vertebrate cPcdhs, of combined specificity when coexpressed. Our findings identify sDscams as likely candidates to mediate neuronal self-avoidance in Chelicerata, as well as provide a remarkable example of convergent evolution.

Keywords: Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule, homophilic binding, combinatorial specificity, self-recognition, Chelicerata

Abstract

Thousands of Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule (Dscam1) isoforms and ∼60 clustered protocadhrein (cPcdh) proteins are required for establishing neural circuits in insects and vertebrates, respectively. The strict homophilic specificity exhibited by these proteins has been extensively studied and is thought to be critical for their function in neuronal self-avoidance. In contrast, significantly less is known about the Dscam1-related family of ∼100 shortened Dscam (sDscam) proteins in Chelicerata. We report that Chelicerata sDscamα and some sDscamβ protein trans interactions are strictly homophilic, and that the trans interaction is meditated via the first Ig domain through an antiparallel interface. Additionally, different sDscam isoforms interact promiscuously in cis via membrane proximate fibronectin-type III domains. We report that cell–cell interactions depend on the combined identity of all sDscam isoforms expressed. A single mismatched sDscam isoform can interfere with the interactions of cells that otherwise express an identical set of isoforms. Thus, our data support a model by which sDscam association in cis and trans generates a vast repertoire of combinatorial homophilic recognition specificities. We propose that in Chelicerata, sDscam combinatorial specificity is sufficient to provide each neuron with a unique identity for self–nonself discrimination. Surprisingly, while sDscams are related to Drosophila Dscam1, our results mirror the findings reported for the structurally unrelated vertebrate cPcdh. Thus, our findings suggest a remarkable example of convergent evolution for the process of neuronal self-avoidance and provide insight into the basic principles and evolution of metazoan self-avoidance and self–nonself discrimination.

Patterning of the developing brain is critically affected by the precision of selective recognition and the strength of the interactions between cell adhesion receptors (1, 2). Two large cell adhesion receptor families, Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule (Dscam1) of the immunoglobulin superfamily and clustered protocadherins (cPcdhs) of the cadherin superfamily, play a central role in neural circuit assembly in insects and vertebrates, respectively. These proteins mediate highly selective homophilic interactions and generate a unique molecular identity at the surface of individual neurons, thereby enabling them to distinguish self from nonself and ultimately to self-avoid. Genetic studies using fly and mouse neurons have described a remarkably similar molecular strategy of self-avoidance (3–12). Homophilic interactions between identical repertoires of Dscam/cPcdh proteins on the surface of the same neuron lead to self-recognition and result in neurite repulsion. In contrast, contact by two arbors from distinct neurons, with differing isoform compositions, does not result in homophilic binding and does not trigger an avoidance mechanism.

In Drosophila, neuronal self-avoidance is mediated by stochastic alternative splicing of a single gene, Dscam1, that can encode as many as 19,008 isoforms with distinct ectodomains (13–16). Different isoforms share the same domain organization with 10 Ig domains, 6 fibronectin type III (FNIII) domains, a single transmembrane (TM) region, and a cytoplasmic domain, but differ in the primary sequences of at least 1 of 3 Ig domains. Individual neuronal identities are determined by the stochastic expression of a small set of 10 to 50 distinct Dscam1 isoforms of the tens of thousands of possible isoforms that can be generated via alternative splicing (8, 14, 17, 18). In contrast to insect Dscam1, vertebrate Dscam genes do not produce extensive isoform diversity (19). In vertebrates, a different set of cell surface adhesion receptors, the cPcdhs, performs an analogous function (20–23). In human and mouse, 53 and 58 cPcdh proteins, respectively, are encoded by three tandemly arranged gene clusters of Pcdhα, Pcdhβ, and Pcdhγ (24, 25). Single neuronal surface identity is achieved by a combination of stochastic promoter selection and alternative splicing (26–28). In addition to engaging in trans (cell-to-cell) through strict homophilic interactions (29, 30), cPcdhs also exhibit an additional independent cis (same cell) interaction that is isoform promiscuous. It is surprising that fewer than 60 proteins are able to mediate the process of neuronal self-avoidance in the complex mammalian brain, as opposed to thousands of isoforms required for an analogous function in Drosophila. Studies using cell aggregation assays have found a possible explanation for this challenge. Specifically, in these assays recognition of cells that express multiple distinct cPcdh isoforms was observed to be dependent on the combined identity of all expressed isoforms (29, 30). That is, two cells that express a mismatched isoform will not bind to each other even if all other expressed cPcdh isoforms are identical.

The Chelicerata subphylum is a basal branch of arthropods that includes animals, such as spiders and scorpions, with relatively complex brains that are similar in magnitude to that of the Drosophila brain (31). In contrast to Drosophila Dscam1, Chelicerata Dscam genes do not generate highly diverse proteins and do not have cPcdh genes. Recently, we discovered a “hybrid” gene family in the subphylum Chelicerata that is particularly relevant to the remarkable functional convergence of Drosophila Dscam1 and vertebrate cPcdhs. This gene family is composed of Dscam-related genes with tandemly arrayed 5′ cassettes, which encode ∼50 to 100 isoforms each with alternative promoters for the number of isoforms varying across Chelicerata species (32, 33). Although these Chelicerata Dscams are evolutionarily related to Drosophila Dscam1, they only have 6 extracellular domains (3 Ig and 3 FNIII domains), making them much shorter compared to the 16 domains of Drosophila Dscam1. We therefore refer to this type of Dscam as shortened Dscam (sDscam) to distinguish it from classic Dscam (33). Based on their different variable 5′ cassettes that encode a single or two Ig domains, these sDscams can be subdivided into sDscamα and sDscamβ subfamilies, respectively. Thus, all sDscam isoforms share the same domain organization with different amino acid primary sequences of at least the N-termini Ig domains.

Interestingly, the 5′ variable regions of Chelicerata sDscams exhibit a remarkable organizational resemblance to those of vertebrate-clustered Pcdhs (32–34). Similar to Drosophila Dscam1 and vertebrate Pcdhs, Chelicerata sDscam are abundantly expressed in the nervous system and their expression is controlled by promoter choice (32, 33). Because Chelicerata sDscams are closely related to Drosophila Dscam1, and exhibit a striking organizational resemblance to the vertebrate-clustered Pcdhs, with the latter two proteins both capable of mediating self-recognition and self-avoidance, we speculate that these sDscam isoforms play analogous roles in Chelicerata species. Therefore, it is essential to perform a systemic examination of the homophilic recognition specificities of these clustered sDscam isoforms to clarify their potential roles in specifying single-cell identities and neural circuit assembly.

In this study, we demonstrate that all tested sDscamαs and some sDscamβs engage in highly specific homophilic interactions via antiparallel self-binding of the variable Ig1 domain. Moreover, we provide compelling evidence that sDscam isoforms associate promiscuously in cis, which is mediated by the constant FNIII1–3. Remarkably, using a cell aggregation assay we found that, as is the case for the cPcdh, cell–cell recognition depends on the combined identity of all isoforms expressed. We propose that these sDscam are able to sufficiently provide the unique single-cell identity necessary for neuronal self–nonself discrimination. Interestingly, in many respects Chelicerata sDscams exhibit more parallels with the genetically unrelated vertebrate Pcdhs than to the closely related fly Dscam1. Thus, our findings provide mechanistic and evolutionary insight into self–nonself discrimination in metazoans and enhance our understanding of the general biological principles required for endowing cells with distinct molecular identities.

Results

Cluster-wide Analysis of sDscam Homophilic Interactions.

The Mesobuthus martensii sDscam gene clusters encode 95 diverse cell adhesion proteins that consist of 40 clustered sDscamα and 55 sDscamβ isoforms. The sDscamβ family is further divided into six additional clusters (β1–β6) with the following distribution: 13 β1, 8 β2, 13 β3, 9 β4, 10 β5, and 2 β6 (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Table S1) (32, 33). To investigate whether sDscam isoforms mediate homophilic binding, we expressed the sDscam proteins in Sf9 cells using an insect baculovirus expression system (Fig. 1B). This system is a powerful tool for investigating homophilic interactions between expressed cell surface adhesion molecules (35). An analogous approach, using different cells, was used in studies of trans binding properties of mouse cPcdh and Drosophila Dscam (7, 29, 30). Sf9 cells that expressed constructs encoding sDscamβ6v2, either full-length (β6v2FL-mCherry) or lacking the cytoplasmic domain (β6v2Δcyto-mCherry), exhibited strong aggregation (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). This finding indicates that the homophilic interaction is mediated by sDscamβ6v2 in trans independent of the cytoplasmic region. We therefore used Δcyto constructs for all sDscam proteins in the cell aggregation assay.

Fig. 1.

Cluster-wide analysis of sDscam-mediated homophilic binding in M. martensii. (A) Overview of the M. martensii sDscam gene clusters. Variable exons (colored) are joined via cis-splicing to the constant exons (black) in sDscamα (Left) and sDscamβ1–β6 (Right) subfamilies. Each variable cassette of sDscamα encodes Ig1 domain, while that of sDscamβ encodes Ig1–2 domains. The constant exons of sDscamα and sDscamβ encode the Ig2–3 or Ig3 domains, FNIII1–3 domains, the TM and cytoplasmic domains. (B) Schematic diagram of the cell aggregation assay. mCherry-tagged sDscam proteins are expressed in Sf9 cells to test their ability to form cell aggregates. As shown in the diagram, cells expressing some sDscam-mCherry alone do not aggregate as negative control-mCherry, while strong cell aggregates were observed with cells expressing other sDscam-mCherry as positive control Dscam1-mCherry. (C) A summary for results of homophilic binding properties, with an evolutionary relationship among distinct sDscam subfamilies shown on the left. (D) The outcome of cell aggregation mediated by 86 sDscam isoforms when assaying individually. mCherry and fly Dscam1 isoform were used as negative and positive control respectively. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C. (Scale bar, 100 µm.)

We performed a systematic analysis of the homophilic interactions for 86 of the 95 sDscam proteins (34 of 40 sDscamα, and 52 of 55 sDscamβ1–β6), as 9 sDscam cDNAs failed to be cloned (SI Appendix, Table S1). We found that all of the 34 sDscamαs, which were individually expressed, formed homophilic aggregates (Fig. 1 C and D). In contrast, only 15 of the 52 sDscamβ isoforms tested formed homophilic aggregates; 8 of these belonged to the β5 cluster (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B and Table S1). The size of the cell aggregates varied markedly across the sDscam subfamilies and the individual isoforms according to quantitative assay (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). Cells expressing sDscamα isoforms exhibited extensive aggregation for all isoforms tested (Fig. 1D, rows 1 to 3, and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Similarly, the 2 β6 cluster isoforms and 8 of the 10 β5 cluster isoforms formed homophilic aggregates (Fig. 1D, rows 8 and 9, and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). In contrast, none of the sDscamβ1 or -β4 cluster isoforms, nor the majority of isoforms of the sDscamβ2 and -β3 clusters, formed any homophilic aggregates (Fig. 1D, rows 4 to 7). We note that aggregates of the cells expressing sDscamβ isoforms were largely smaller than those expressing sDscamαs (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C). Additionally, in some cases, cells expressing individual sDscam isoforms, belonging to the same cluster, which differed only in the N-terminal variable region, exhibited markedly different cell aggregation behavior. For example, only three of the eight tested isoforms within the sDscamβ2 subfamily formed homophilic aggregates, while the other five members did not (Fig. 1D). Isoforms from the sDscamβ3 and β5 clusters exhibited a similar cluster discrepancy in their cell aggregation behavior (Fig. 1D, rows 6 and 8).

This discrepancy in aggregation activity between sDscam isoforms was likely due to differences in expression, membrane localization, or intrinsic trans-binding affinities of the individual isoforms (30). For example, failure to form cell aggregates in mammalian Pcdhα isoforms is reportedly due to a lack of membrane localization (30, 36, 37). However, immunostaining revealed that both sDscamβ4v3, which does not mediate cell aggregation, and sDscamα14, which engages in homophilic interactions, were detected on the surface of Sf9 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D). Moreover, sDscamβ4v1, which does not mediate cell aggregates, was expressed at a similar or higher level to those exhibited by isoforms that mediate cell aggregates (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E). In general, we did not observe a correlation between isoform expression level and cell aggregation outcome among individual isoforms (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E). Further truncation and domain-swapping experiments indicate that the first two N-terminal Ig domains are essential for homophilic trans binding (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3). In particular, we note that at least some sDscamβ isoforms are able to interact homophilically via their membrane distal Ig domains, yet their membrane proximate FNIII domains and the TM region inhibit homophilic binding (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 C–G and S3A).

sDscams Exhibit Highly Specific Isoform Binding.

A striking and functionally crucial property of Drosophila Dscam and vertebrate cPcdh isoforms is the strict homophilic specificity recognition in trans. To analyze the specificity of trans interactions between different sDscams, we assessed cell aggregates formed via mixing of two fluorescently labeled cell populations (Fig. 2A). Each sDscam was expressed with mCherry or an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) fused to the C terminus and assayed for binding specificity (Fig. 2 C–G). First, we investigated the specificity of the interaction between sDscamα isoforms, which differed only by their Ig1 domain at the N terminus. To determine the stringency of recognition specificity, we generated pairwise sequence identity heat maps of the variable Ig1 domains (Fig. 2B). Using these heat maps, we identified sDscam pairs that had the highest pairwise sequence identity within their Ig1 domains. We tested 14 of the sDscams with the highest pairwise sequence identity (>87% identity) (Fig. 2B) along with 21 more distantly related sDscams (Fig. 2C). In total, we tested 35 unique pairs of sDscams with the sequence identity for nonself pairs ranging from 50 to 97% in the Ig1 domains. Despite the high sequence identity for many of the pairs, all but a single pair of sDscamα isoforms exhibited exclusively homophilic interaction specificity with no observed heterophilic interactions (Fig. 2 C–G and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). Only self-pairs on the matrix diagonals exhibited intermixing of red and green cell aggregates, while (with one exception) all nonself pairs formed separate, noninteracting homophilic cell aggregates (Fig. 2 C–G and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). Heterophilic binding was only detected for one pair of isoforms, sDscamα20 and sDscamα36, which are closely related with variable Ig domain amino acid sequences that are ∼97% identical (Fig. 2G). Similar results have been obtained for reciprocal binding pairs. These data indicate that similar to Drosophila Dscam and vertebrate cPcdh, the sDscamα isoforms exhibit a strict homophilic specificity. Additionally, these data indicate that the first variable Ig domain of sDscamα determines binding specificity.

Fig. 2.

sDscam isoforms engaged in highly specific homophilic interactions. (A) Schematic diagram of the binding specificity assay. Cells expressing mCherry- or EGFP-tagged sDscam isoforms were mixed and assayed for homophilic or heterophilic binding. The outcome of cell aggregation included red-green cell segregation and red-green cell coaggregation. (B) Heat map of pairwise amino acid sequence identities of the Ig1 domains of sDscamα isoforms and their evolutionary relationship. Subsets of the isoforms marked by an asterisk (*) and within the boxed region were assayed in C–G. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S4A. (C) Pairwise combinations within representative sDscamαs were assayed for their binding specificity. (D–F) sDscamα isoforms with sequence identity for nonself pairs ranging from 87 to 94% in their Ig domains display strict trans homophilic specificity. Mean coaggregation (CoAg) indices were quantified and illustrated as a heat map. (G) Pairwise combinations within sDscamα20, -30, -36 pairs were assayed for their binding specificity. sDscamα36 exhibited strong heterophilic binding to sDscamα20, but not to sDscamα30. (Scale bars, 100 µm.)

We then investigated the specificity of the interactions between sDscamβ isoforms, which differ in their Ig1–2 domains at the N terminus. We tested pairwise combinations of isoforms that belong to the sDscamβ5 cluster and pairwise combinations of isoforms that belong to the sDscamα and -β5/β6 clusters. All of the sDscamβ5/β5, -α/β5, and -α/β6 pairs tested bound strictly homophilically (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 C and D). Taken together with the results of sDscamα analyses (Fig. 2), these observations demonstrate that sDscamα and sDscamβ5/β6 isoforms exhibit strict homophilic trans binding.

Domain Shuffling Identifies Variable Ig1 as the Specificity-Determining Domain.

The sDscamα isoforms differ only in their first Ig domain, which indicates that this domain contributes to the trans binding specificity observed in the cell aggregation assays. In contrast to sDscamαs, all sDscamβ isoforms contain two variable Ig domains at the N terminus. To identify the domains responsible for the specificity of sDscamβ isoform trans interactions, we constructed a series of Ig-domain swapping chimeras. The sDscamβ5v4 Ig1 domain was replaced with the -β5v10 Ig1 domain (Fig. 3A), which share 46.7% pairwise sequence identity within their Ig1 domains. As a result, this chimeric construct no longer interacted with its parent sDscamβ5v4; however, it continued to interact with sDscamβ5v10, with which it shares only the Ig1 domain (Fig. 3 A, ii and iv, and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). In contrast, a chimeric construct encoding sDscamβ5v4 with its Ig2 domain replaced by that of sDscamβ5v10 continued to interact with its parent sDscamβ5v4, but not with sDscamβ5v10 (Fig. 3 A, i and iii). Identical results were obtained by Ig domain swapping between sDscamβ5v8 and -β5v10 (Fig. 3 A, v–viii), and sDscamβ5v5 and -β5v10 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B).

Fig. 3.

sDscam trans-binding specificity is largely dependent on N-terminal Ig1 domain. (A) Domain-shuffled chimeras of sDscamβ5 isoforms and their parental counterparts were assayed for binding specificity. Chimeras in which either the Ig1 or Ig2 domains were replaced with the corresponding domains of cluster-within isoforms swapped or not swapped trans-binding specificity. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S5. (B) Swapped specificity was observed in sDscamβ5v10 and sDscamβ6v1 chimeras. These chimeras were constructed through replacing either the Ig1–2 or single Ig1/Ig2 domains with the corresponding domains of different cluster isoforms. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S5A. (C) Domain-shuffled chimeras between sDscamα and sDscamβ3 and their parental counterparts were assayed for binding specificity. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S5A. (D) Schematic representation of domain-shuffled sDscam chimeras with a summary of results in their binding specificity assay. These data indicated that the presence of a single common Ig1 domain might be essential and sufficient to confer coaggregation between sDscam isoforms. (Scale bars, 100 µm.)

Isoforms belonging to different clusters differ in their entire sequence (i.e., not only in the alternatively spliced exons). Nevertheless, similar to the results above, chimeric constructs that replaced the Ig1 domain between two parent isoforms from distinct clusters only coaggregate with the parent isoform that has an identical Ig1 domain, despite of differences in the constant region (Fig. 3 B and C). We tested the chimera generated by replacing the first Ig domain of isoforms from the β6 and β5 clusters (Fig. 3B), as well as those from the β3 and α clusters (Fig. 3C). Overall, these domain-swapping experiments suggested that the first Ig domain is the primary determinant of trans interaction specificity (Fig. 3D), and that the constant regions of sDscam isoforms are not involved in defining binding specificity.

sDscams Interact in Trans via Antiparallel Ig1 Self-Binding.

To gain insight into how the variable Ig1 domain mediates specific homophilic binding, we carried out homology modeling studies to generate homodimeric complexes of sDscamα Ig1. We used the dimeric structure of the Drosophila Dscam variable Ig7 domain as a template, as previous studies have found that the Ig1 domain of sDscam is homologous to the variable Ig7 domain of Drosophila Dscam1 (33) (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7 A and B). The Ig7 domain of Drosophila Dscam1 is one of three domains (together with the second and third Ig domains) that determine trans binding specificity. We hypothesized that because of the evolutionary relationship, the Ig1 domain of sDscam may maintain the overall molecular mechanism of the Ig7 trans interactions shown in the homodimeric structure of Drosophila Dscam1. Using the SWISS-MODEL program with the crystal structure of Drosophila Dscam1 Ig7.5 (PDB ID code 4WVR, 1.95 Å) (38, 39) as a template, we built an Ig1 homodimeric model of all sDscamα isoforms. These structural models suggested that the Ig1 domain of sDscamα interacts in an antiparallel orientation via residues on the ABDE β-strands (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). Next, we tested these models using mutations designed to disrupt homophilic interactions and binding specificity.

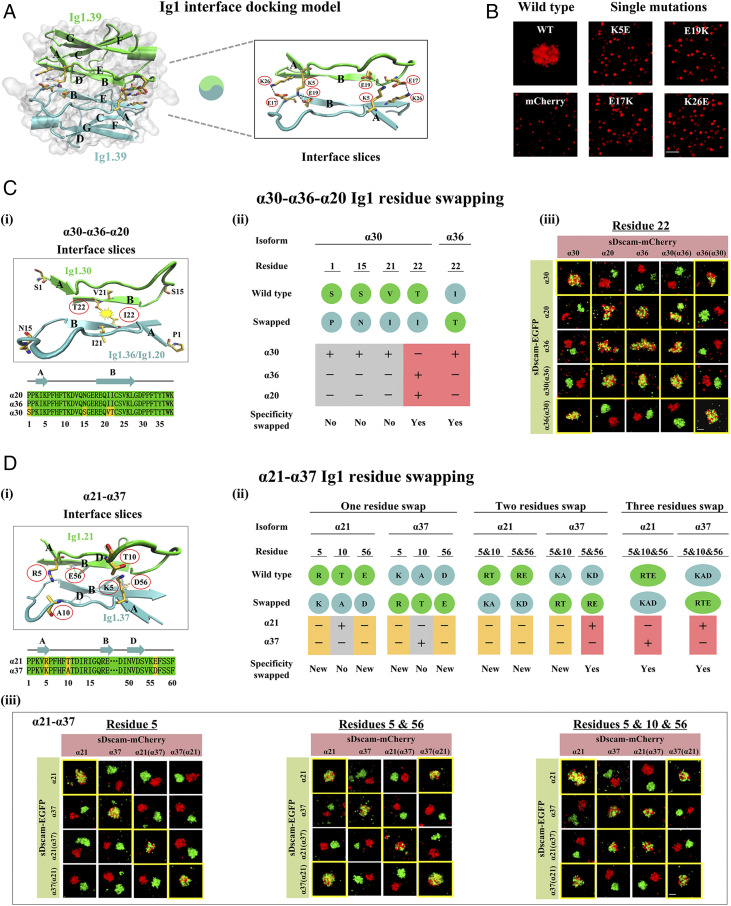

Fig. 4.

Identification of Ig1 specificity-determining residues. (A) Ig1.39 domain structural modeling. Structural modeling shows that Ig1.39 domain might interact in an antiparallel fashion. (Left) The interaction residues (predicted by PDBePISA) represented in licorices have been shown in the homodimer model. (Right) Slices of the Ig1.39–Ig1.39 interface between strand AB subunits. Potential interaction residues (K5 and E19; E17 and K26) are shown in licorices. (B) The single point mutations of these candidate residues were assayed for cell aggregation. The single point mutation disrupted cell aggregates, supporting the antiparallel binding fashion. (C) Residues swapping between sDscamα20, -α30, -α36 were designed to assess specificity-determining residues. (i) Ig1 docking model and sequence alignments of shuffled regions. Four candidate specificity-determining residues were located on adjacent B strands. (ii) Schematic representation of residue swapping mutants used in the experiments, along with a summary of results from binding specificity. (iii) The binding specificity of isoforms containing wild-type and swapped residue 22. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S9A. (D) Residues swapping of variable Ig1 between sDscamα21 and -α37. (i) Ig1 docking model and sequence alignments of the shuffled regions. Three candidate specificity-determining residues were located on adjacent A, B, and D strands. (ii) Schematic diagrams of residue swapping mutants used in the experiments, along with observed binding specificity. (iii) Cell aggregation assays of isoforms containing wild-type and residue-swapped Ig1 domains. Swapping of either one of three residues in Ig1.21 to Ig1.37 did not swap the binding specificity, and swapping of two of three residues partially swapped the binding specificity, and swapping of all three residues fully swapped the binding specificity. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S9G. (Scale bars, 100 µm.)

Based on the structural models of two isoforms, sDscamα30 and sDscamα39, we predicted the formation of two salt bridges at the interface. One salt bridge was formed by lysine residue 5 (K5, sDscamα Ig1 numbering) in the A strand and glutamic acid residue 19 (E19) in the B strand, and a second was formed by E17 in the AB loop and K26 in the B strand (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). To experimentally test this binding model, we performed single mutations, swapping the charges of the predicted salt-bridge residues (K5E, E19K, E17K, and K26E), and assessed their ability to mediate cell aggregation. As a result, sDscamα39 mutants did not aggregate homophilically and sDscamα30 mutants exhibited smaller aggregates (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A and B). We note that the mutant protein expression levels and protein stability did not significantly differ from those of wild-type proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 C and D). Although we did not directly investigate the effect that Ig1 domain point mutations have on cellular localization, a series of ΔIg1 mutants were all cell surface-located (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 D, i–vi).

We next identified Ig1 specificity-determining residues. Candidate residues were selected if they were located at the sDscamα trans dimer model interface and differed between closely related sDscamα isoforms. We tested specificity determining residues by swapping these residues between closely related isoforms and analyzed their recognition preferences in our Sf9 cell aggregation assay (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 A and B). For example, the closely related sDscamα20, -α30, and -α36 isoforms had a greater than 91% sequence identity within their Ig1 domain. As shown above, sDscamα20 and sDscamα36 exhibited both homophilic as well as heterophilic recognition to each other but not with sDscamα30. Only four residues are identical between sDscamα20 and -α36 but differ in the sDscamα30 sequence (1S/P, 15S/N, 21V/I, and 22I/T) (Fig. 4 C, i); however, only residue 22I/T is found at the interface in our structural trans dimer model. Swapping residue 22 between sDscamα36 and sDscam30 resulted in switching their binding preferences (Fig. 4 C, ii and iii). Mutated I22T sDscamα36 no longer binds to sDscamα36 or sDscamα20 but does bind to sDscamα30. Similarly, mutated T22I sDscamα30 binds to sDscamα36 and sDscamα20 but not to its parent isoform, sDscamα30 (Fig. 4 C, ii and iii). In contrast, mutating the remaining three residues (1S/P, 15S/N, and 21V/I) did not result in a change in binding specificity, thereby strengthening the validity of our postulated trans binding interface model.

Importantly, we identified the equivalent position of residue 22 as a specificity-determining candidate residue in a different group of three closely related sDscamα isoforms: sDscamα11, -13, and -15. Swapping residue 22 between sDscamα11 and -α15, or between sDscamα13 and -α15, produced a novel homophilic binding specificity without swapping their binding specificity (SI Appendix, Fig. S9C). The finding that the same structural position determines binding specificity in distantly related sDscamα suggests that this region likely contributes to binding specificity in additional sDscamα isoforms. These observations also suggest that additional residues at the Ig1/Ig1 interface contribute to binding specificity. Using a similar approach, we analyzed the sequences of other closely related isoforms and identified additional candidate specificity-determining residues located at the putative interface (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 D–G). We found that shuffling residues 52 between sDscamα11 and -α13 and between sDscamα23 and -α27 altered, but did not swap binding specificity (SI Appendix, Fig. S9E). In addition, we found that swapping residues 5, 10, and 56 between sDscamα21 and -α37 and residues 6, 19, and 52 between sDscamα23 and -α27 swapped binding specificity (Fig. 4D and SI Appendix, Fig. S9F). The key residues identified in the above experiments were frequently located at the ABED strands. Overall, the binding preferences of the designed mutations support the structural model based on the Drosophila Dscam Ig7 homophilic interface.

sDscams Form Cis-Multimers Independently of Trans Interactions.

Many cell adhesion and signaling receptors form stable homo- and hetero-oligomers, which are important for trans interactions. Studies of classic cadherins have shown that cooperation between cis and trans interactions is crucial for ordered junction formation (40). The evolutionarily related cPcdhs have been shown to form stable homo and hetero cis dimers independent of trans interactions and are thought to be critical in forming large oligomeric (zipper) assemblies and in recognition specificity (41, 42). To test the ability of sDscam isoforms to form cis interactions, lysate from Sf9 cells cotransfected with sDscam-HA and sDscam-Myc were coimmunoprecipitated (co-IP) using an HA antibody and detected by Western blot analysis with Myc antibody (Fig. 5A). Because our data indicate that deletion of the cytoplasmic domain did not significantly affect sDscam interactions (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 A and B), we used the Δcyto constructs to study sDscam cis interactions. When HA-sDscamβ6v2 and Myc-sDscamβ6v2, -β4v1, or -β4v2 were coexpressed by coinfection with individual recombinant viruses, Myc-tagged proteins strongly co-IP with HA-β6v2 (Fig. 5B). Similar results were obtained for co-IP experiments with isoforms from different clusters, indicating that sDscam proteins interact with each other and exhibit no specificity between isoforms of the same or different clusters (Fig. 5B and SI Appendix, Fig. S10C). To ensure that the interactions we observed were not trans interactions, we performed similar co-IP experiments with mutant isoforms designed to lack trans interactions. HA-sDscamβ4v1 and Myc-β4v2, which did not exhibit homophilic trans interactions in cell aggregation assays, were immunoprecipitated with HA antibody and detected using Western blot analysis with Myc-antibody (SI Appendix, Fig. S10C). Moreover, Ig1 domain deletions, which ablated homophilic trans interactions in cell aggregation assays, did not affect the co-IP outcome (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 D and E). These results support the notion that sDscams multimerize in cis independently of trans interactions and indicate that the robust sDscam multimers result from cis interactions.

Fig. 5.

sDscams form promiscuous cis-multimers mediated by FNIII1–3 domains. (A) Schematic diagram of cis and trans interaction of sDscam. sDscam monomers interacted in a parallel fashion to form a homomultimer or heteromultimer complex, while trans-multimers are formed between two opposing cells in an antiparallel fashion. (B) All sDscamα and sDscamβ isoforms tested interacted strongly with each other in co-IP experiments. Lysates from Sf9 cells cotransfected with sDscamα1 and sDscamβ6v2 bearing a C-terminal HA-tag, and different Myc-tagged sDscam isoforms were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA antibody and probed with anti-Myc or anti-HA antibodies. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S10C. (C) sDscamβ6v2 expressed in Sf9 cells formed cis-multimers. Boiled and unboiled samples were analyzed by Western blot with Myc antibody (Left), and with sDscamβ6v2 antibody (Right). (D) Multimerization assay of lysates from Sf9 cells expressing distinct sDscam isoforms (i) and the scorpion cephalothorax (ii). (E) sDscams formed cis-multimers in the absence of trans interaction. (i) Proteins lacking Ig1–2, which have abolished homophilic trans interactions, could also form robust multimers. (ii) Single residue mutations, which abolished homophilic cell aggregation, caused increased multimerization. (F) A series of N-terminal truncations of the extracellular domain of sDscamβ6v2 fused with Myc-tag were examined for multimerization assay. Unboiled and boiled samples were analyzed by Western blot (i and ii). See also SI Appendix, Fig. S10G. (G) Co-IP and multimerization assay of FNIII1–3 domains. sDscamβ6v2 interacted strongly with each truncated protein expressing individual or combined domain of FNIII1–3s (i), and the truncated proteins could form strong cis-multimers (ii).

To further characterize the cis interaction between sDscam isoforms, we performed multimer analysis by Western blotting with Myc antibody or antibodies specific to isoform (SI Appendix, Fig. S10F) in both boiled and unboiled samples. The boiled sDscamβ6v2 migrated with a single molecular mass of ∼80 kDa, which corresponded to the size of the monomer (Fig. 5C). However, several large bands migrated behind the monomer in the unboiled samples, which corresponded to the size of sDscam assembly of putative dimer, tetramer, and larger multimers (Fig. 5C). We observed multimerization to different extents in all sDscam proteins investigated, suggesting that sDscam proteins from different subfamilies are able to cis-multimerize (Fig. 5 D, i). Furthermore, we observed in vivo abundant endogenous sDscamβ6v2 multimers in the cephalothorax of scorpions (Fig. 5 D, ii). Using a series of sDscamβ6v2 extracellular domain truncations from the N terminus, we identified the extracellular region that contributes to cis interactions (Fig. 5F). We found that the truncated proteins lacking Ig1 (β6v2ΔIg1), Ig1–2 (β6v2ΔIg1–2), and Ig1–3 (β6v2ΔIg1–3) exhibited robust multimerization (Fig. 5 F, i, lanes 2–4). Similar results have been obtained in other sDscamα, -β1, -β2, and -β5 proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S10G). Co-IP experiments and multimerization assays revealed that the deletion constructs containing individual or multiple continuous FNIII domains were capable of binding to sDscamβ6v2 (Fig. 5G). This result is also consistent with computational modeling using the ZDOCK server (43), by which sDscamβ6v2 could form a homodimer via multiple parallel interfacial regions involving the FNIII1–3 domains (SI Appendix, Fig. S10H). Because the sDscamβ6v2 FNIII1–3 domains lack cysteine residues (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), they likely mediate cis multimerization by noncovalent mechanisms. Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that the Ig1–3 domains of sDscam that include the region that contributes to trans interactions are not required for cis interactions, and that membrane-proximal FNIII1–3 domains are sufficient for efficient cis multimerization.

To further investigate whether the TM domain of sDscam contributes to cis multimerization, we first examined the effect of TM deletion on self-multimerization of sDscam. Each of the truncated ΔTM proteins was capable of multimerizing, indicating that the extracellular domain is sufficient to confer efficient cis multimerization (SI Appendix, Fig. S12A). However, multimerization efficiency was markedly reduced in most sDscamΔTM mutants. Additionally, we observed dimerization of TM peptides expressed from all six sDscams investigated (SI Appendix, Fig. S12B). A further mutation experiment revealed that mutation of a cysteine residue in the TM domain did not markedly affect the formation of cis-multimers in both the β6v2 and β6v2ΔIg1–3 constructs (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 C and D). Collectively, these results suggest that the TM domain of each sDscam likely mediated cis-multimerization.

Coexpression of Multiple sDscam Isoforms Diversifies Homophilic Specificities.

Previous studies have shown that coexpression of distinct cPcdh isoforms results in new cell recognition that depends on the combination of all isoforms expressed. The expression of even a single mismatched isoform between cells expressing common cPcdh isoforms prevented intermixed cell aggregation (29, 30). Similar to cPcdh, sDscamα isoforms and some sDscamβs interact through homophilic trans binding (Fig. 1D) while simultaneously demonstrating promiscuous specificity in cis (Fig. 5). We therefore tested the manner in which combinatorial expression of multiple sDscam isoforms diversified binding specificities. In almost all cases, cells coexpressing a set of two sDscamα isoforms failed to coaggregate with cells expressing a different set of two sDscamαs (Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Fig. S13 A–C). In contrast, cells that coexpressed the same set of sDscamα isoforms demonstrated robust intermixing of cell aggregates. Consistent with these observations, co-IP experiments revealed that different sDscamαs interact with each other when coexpressed (SI Appendix, Fig. S13D, lanes 1 and 2). Similar data were obtained for each of the sDscamα/β pairs (Fig. 6B and SI Appendix, Fig. S13D, lanes 3 and 4). These results suggest that the identity of both isoforms determine the recognition specificity of cells coexpressing two distinct isoforms.

Fig. 6.

Combinatorial coexpression of multiple sDscam isoforms generates unique cell surface identities. (A and B) Combinatorial coexpression of multiple sDscam isoforms generates unique cell surface identities. Cells coexpressing an identical or a distinct set of sDscamα (A) and sDscamβ5–β6 isoforms (B) were assayed for coaggregation. Mean CoAg indices for each experiment were shown in the upper right of each representative image. (C) Cells coexpressing three distinct mCherry-tagged sDscam isoforms were assayed for interaction with cells expressing an identical or a distinct set of GFP-tagged sDscam isoforms. The nonmatching isoforms between two cell populations were underlined. (Scale bars A–C, 100 μm.) (D) Illustration of the outcome of cell–cell interaction dictated by combinatorial homophilic specificity of two (Left) and three (Right) distinct sDscam isoforms. This schematic diagram presented here does not reflect the cis-multimer, and the nonmatching isoform is shown with the asterisk.

We also coexpressed distinct sets of three sDscam isoforms and evaluated their ability to coaggregate with cells containing various numbers of mismatches (Fig. 6C). We found that only cells expressing identical isoform combinations formed intermixed aggregates, while cells expressing mismatched isoforms largely displayed separate red and green aggregates (Fig. 6C). Remarkably, even when two of the three isoforms were identical, the cells did not coaggregate (Fig. 6C, panel 3). However, we also observed a “mixed state” with an intermediate coaggregation index, where separate red and green aggregates coexisted with intermixing aggregates (Fig. 6C, panels 2 and 10). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that sDscams interact in cis to create new homophilic specificities that differ from the specificities of the individual sDscam isoforms.

Discussion

Here, we provide compelling evidence that different combinations of sDscam isoforms interact in cis to significantly expand the homophilic trans recognition specificities in Chelicerata. Specifically, we demonstrated that sDscam isoforms engage in a strict homophilic interaction in trans via their Ig1 domains. Furthermore, the Ig1:Ig1 interactions are likely to occur in an antiparallel orientation and be structurally similar to the trans interactions observed for the Ig7 domains of Drosophila Dscam1. We found that different sDscam isoforms interact in cis promiscuously and that the cis interaction is independent of the trans interaction. Our results indicate that sDscam cis interactions are mediated via the membrane-proximal FNIII1–3 domains. Importantly, we found that when multiple sDscam isoforms are coexpressed, cellular recognition depends on the identity of all expressed isoforms. Cells will only bind if both cells express the same set of isoforms. Below, we discuss our data with a particular emphasis on comparison of the Chelicerata sDscam with fly Dscam1 and vertebrate cPcdhs, both of which carry out the role of self-avoidance in insects and vertebrates, respectively. We also discuss the challenges and requirements for neuronal self-avoidance.

sDscams Mediate Highly Specific Homophilic Recognition via Self-Binding Variable Ig1.

Our findings indicate that all sDscamα and some sDscamβ isoforms engage in specific homophilic interactions (Figs. 1D and 2 B–E and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The strict preference for homophilic interactions is exemplified by our observation that most pairs of sDscams, with sequence identities >90%, do not demonstrate heterophilic interactions. In contrast, the majority of sDscamβ1–β6 isoforms did not interact homophilically in our assay (Fig. 1D). However, sDscamβ chimeric constructs (i.e., sDscamβ4v1 and -β4v3) produced by deleting or replacing their partial constant region, did, in fact, engage in homophilic interactions (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 C, xv and xvi, SI Appendix, Fig. S2 F, i and ii, and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A, panels 15–17). This finding indicates that the failure in homophilic recognition is not due to incompatibility of the trans self-binding interface. Thus, it seems likely that at least some of these sDscamβs mediate self-recognition, although the underlying mechanism remains unknown.

Our structural modeling and mutagenesis experiments demonstrated that sDscam homophilic specificity is determined by an antiparallel Ig1/Ig1 self-binding (Fig. 4 A and B). Because the Ig1 domain of Chelicerata sDscams is homologous to the Ig7 of fly Dscam1 (32, 33), we hypothesized that they have a similar antiparallel self-binding architecture. Indeed, site-directed swapping mutagenesis revealed that Ig1 of Chelicerata sDscams share several key specificity-determining residue positions with Ig7 of fly Dscam1 isoforms (Fig. 4 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S6) (38, 39). These findings further support the evolutionary relationship between Drosophila Dscam1 and Chelicerata sDscams.

However, while the homophilic recognition of sDscam is achieved via association of a single Ig domain, the homophilic specificity of fly Dscam1 is determined via combined specificity of three independent antiparallel self-binding domains, Ig2/Ig2, Ig3/Ig3, and Ig7/Ig7 (18, 38, 39, 44). Notably, self-binding of sDscam Ig1 was sufficient for cell adhesion in our cell aggregation assay. In contrast, self-binding of fly Dscam1 Ig7-Ig7 (single domain) was insufficient to sustain homophilic recognition (18). Although structural models are not accurate enough to study details of the interface, we note that the modeled interface of sDscam buries ∼30% more surface area compared to the Drosophila Dscam1 Ig7 interface (SI Appendix, Fig. S7D). Additionally, fly Dscam with 16 extracellular domains is a significantly longer and more flexible molecule than sDscam, which has only six domains. It is possible that because of the additional degrees of freedom in the fly Dscam, the affinity generated by Ig7 self-binding is insufficient and requires the joint participation of other trans interacting domains to achieve binding.

Chelicerata sDscams Form Promiscuous Cis Interactions.

cPcdh recognition is mediated by a mechanism coupling nonspecific cis and specific trans interactions (29, 30, 41, 42, 45). cPcdh isoforms engage homophilically in trans via four membrane distal domains (EC1–EC4) and in cis via a nonoverlapping and independent interface involving the membrane proximal EC5–EC6 domains (30, 41, 42, 45–49). Our data indicate that although Chelicerata sDscams and cPcdhs are evolutionarily unrelated, they form similar interactions. sDscams interact in trans via a membrane distal Ig1 domain and in cis via a nonoverlapping and independent interface involving the membrane proximal FNIII domains. Several lines of independent evidence support the ability of sDscams to form robust cis interactions. First, distinct sDscam isoforms form different clusters that can be co-IP (Fig. 5B and SI Appendix, Fig. S10C); second, sDscams are present in high molecular-weight detergent-solubilized assembly complexes from the scorpion cephalothorax (Fig. 5 D, ii); third, high-order oligomers are observed with unboiled sDscam samples; and fourth, we observed an altered recognition specificity when multiple sDscam isoforms were coexpressed (Fig. 6). Importantly, our co-IP experiments revealed that sDscam cis interactions are mediated by membrane proximal FNIII domains independently from trans interactions. However, the data presented here largely represent biochemical evidence for sDscam cis interactions using in vitro systems. More structural and biophysical measurements will be needed to define the overall architecture of the sDscam recognition unit.

Requirement of Neuronal Self-Avoidance.

Neuronal self-avoidance requires that interacting neurons have unique cell surface identities so that they will not recognize each other as self and repel. When neuron arbors do not overlap with other neurons of the same type, simple receptor–ligand interactions are sufficient for self-avoidance. For example, the PVD nociceptive neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans separately innervate the left and right body walls and use a single unc40/DCC receptor to control dendritic self-avoidance (50). However, neurons with dendrite arbors that overlap with homotypic neurons require a diverse population of receptors and ligands to discriminate self from nonself interactions.

Insects such as Drosophila generate diverse cell surface populations by randomly expressing a small set of Dscam1 proteins from a pool of tens of thousands of isoforms, each with homophilic specificity (22, 23). In vertebrates, only 50 to 60 cPcdh proteins mediate self-avoidance; it is therefore clear that vertebrate cell surface diversity is not generated solely based on the number of isoforms (20–23). Cell aggregation assays revealed that two populations of cells expressing cPcdhs that differ only by a single isoform segregate into aggregates expressing identical isoforms (30). These results suggest that vertebrate cell surface diversity is achieved through the combined identities of all expressed cPcdh isoforms.

While the Chelicerata sDscam proteins are evolutionary related to Drosophila Dscam1, they encode only 50 to 100 isoforms, which is two orders-of-magnitude less than the number of Drosophila Dscam1 isoforms. Thus, they are unable to produce cell surface diversity in a manner similar to that of Drosophila, which relies solely on the number of isoforms. However, our findings demonstrate that, similar to cPcdhs, the recognition of cells depends on the combined identity of all expressed sDscam isoforms. That is, a single mismatched sDscam isoform ensures that two cells will not recognize each other as self (Fig. 6D). Note that in this study we only showed the potential for sDscam to mediate neuronal self-avoidance in Chelicerata. Further studies, both in vitro and in vivo, will be required before we can confidently state the role of sDscam in neuronal development.

Chelicerata sDscams Have More Parallels with Vertebrate Pcdhs than Drosophila Dscam1.

Our findings indicate that Chelicerata sDscams have striking parallels to Drosophila Dscam1 and vertebrate Pcdhs, thereby suggesting analogous roles. These three cell surface adhesion receptor families encode large numbers of neuronal TM protein isoforms, and the encoded proteins interact strictly homophilically (SI Appendix, Fig. S14) (20, 23, 34). In addition, such a striking isoform diversity has been shown to underlie neuronal self–nonself discrimination for Drosophila Dscam1 and vertebrate Pcdhs (3–6, 51). Although the functional evidence for sDscam diversity is lacking, our results support and extend the notion that different phyla use distinct molecules or mechanisms to underlie the analogous principle for mediating self-recognition and self-avoidance during neuronal arborization (SI Appendix, Fig. S14) (20, 22).

From an evolutionary viewpoint, Chelicerata sDscams are related to Drosophila Dscam1 and have no evolutionary relationship with vertebrate cPcdhs (23, 33). In addition, all Chelicerate investigated have two to eight genes corresponding to the canonical (long) Dscam (32), which is on similar scale to the number of Dscam genes in mammals and non-Dscam1 isoforms in insects. Since fly Dscam2–4 and mammalian Dscams have function in neuronal assembly (52–54), we speculate that chelicerate canonical Dscams would play similar roles in neuronal assembly. However, in many respects, Chelicerata sDscams exhibit more parallels to vertebrate cPcdhs (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). Both are organized in a tandem array in the 5′ variable region, encoding the same order-of-magnitude of isoforms (50 ∼ 100) via alternative promoters. Both have a similar structural composition comprising six extracellular domains, a single TM domain, and a cytoplasmic region. We have now shown that scorpion sDscam, like mouse Pcdhs, exhibits combinatorial recognition specificities based on the assembly of cis interactions. Thus, our findings highlight molecular strategies for neuronal self-avoidance as striking examples of convergent evolution. It will be interesting to learn if convergent examples for self-avoidance in other animals are available. Finally, based on the remarkable parallels between Chelicerata sDscams and vertebrate Pcdhs, we wonder whether cadherins, in the animal kingdom, generate extraordinary isoform diversity via alternative splicing like their fly Dscam1 counterparts. One thing is certain: Insights from extraordinary isoform diversity continue to deepen our understanding of basic biological principles.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Cell Lines.

Sf9 cells (a gift from Jian Chen, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, Hanzhou, China) were cultured in Sf-900 II SFM (Gibco, 10902088) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, 10099141), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, 15140163) at 27 °C.

Cell Aggregation Assays.

Cell aggregation assay was performed as previously reported with some modification (35). Sf9 cells were infected with recombinant viruses of mCherry or EGFP tagged target proteins and incubated at 27 °C for 3 d. Then, the infected cells were allowed to aggregate for 30 min at 27 °C on gyratory shaker (IKA KS260) at 60 rpm. Finally, the Nikon Ti-S inverted fluorescence microscope was used to capture images (details are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods).

Binding Specificity Assay for Cells Expressing Single or Multiple sDscam Isoforms.

Sf9 cells were infected with differentially tagged sDscam isoforms as described above. Images were captured using the Nikon Ti-S inverted fluorescence microscope and counted for analysis of binding specificity (details are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods).

Additional methods can be found in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Heng Ru for technical assistance for homology modeling and for discussion and comments; and Mu Xiao for technical assistance for multimerization assay and comments. This work was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31630089, 31430050, 91740104) and Israel Science Foundation Grant 1463/19. R.R. is supported by the Israel Cancer Research Fund (ICRF 19-203-RCDA).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1921983117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All data used for the study are available in the main text figures and SI Appendix figures and table.

References

- 1.Honig B., Shapiro L., Adhesion protein structure, molecular affinities, and principles of cell-cell recognition. Cell 181, 520–535 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanes J. R., Zipursky S. L., Synaptic specificity, recognition molecules, and assembly of neural circuits. Cell 181, 536–556 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefebvre J. L., Kostadinov D., Chen W. V., Maniatis T., Sanes J. R., Protocadherins mediate dendritic self-avoidance in the mammalian nervous system. Nature 488, 517–521 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mountoufaris G. et al., Multicluster Pcdh diversity is required for mouse olfactory neural circuit assembly. Science 356, 411–414 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hattori D. et al., Robust discrimination between self and non-self neurites requires thousands of Dscam1 isoforms. Nature 461, 644–648 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hattori D. et al., Dscam diversity is essential for neuronal wiring and self-recognition. Nature 449, 223–227 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matthews B. J. et al., Dendrite self-avoidance is controlled by Dscam. Cell 129, 593–604 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhan X. L. et al., Analysis of Dscam diversity in regulating axon guidance in Drosophila mushroom bodies. Neuron 43, 673–686 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes M. E. et al., Homophilic Dscam interactions control complex dendrite morphogenesis. Neuron 54, 417–427 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soba P. et al., Drosophila sensory neurons require Dscam for dendritic self-avoidance and proper dendritic field organization. Neuron 54, 403–416 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hummel T. et al., Axonal targeting of olfactory receptor neurons in Drosophila is controlled by Dscam. Neuron 37, 221–231 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu H. et al., Dendritic patterning by Dscam and synaptic partner matching in the Drosophila antennal lobe. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 349–355 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miura S. K., Martins A., Zhang K. X., Graveley B. R., Zipursky S. L., Probabilistic splicing of Dscam1 establishes identity at the level of single neurons. Cell 155, 1166–1177 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neves G., Zucker J., Daly M., Chess A., Stochastic yet biased expression of multiple Dscam splice variants by individual cells. Nat. Genet. 36, 240–246 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmucker D. et al., Drosophila Dscam is an axon guidance receptor exhibiting extraordinary molecular diversity. Cell 101, 671–684 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun W. et al., Ultra-deep profiling of alternatively spliced Drosophila Dscam isoforms by circularization-assisted multi-segment sequencing. EMBO J. 32, 2029–2038 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wojtowicz W. M., Flanagan J. J., Millard S. S., Zipursky S. L., Clemens J. C., Alternative splicing of Drosophila Dscam generates axon guidance receptors that exhibit isoform-specific homophilic binding. Cell 118, 619–633 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wojtowicz W. M. et al., A vast repertoire of Dscam binding specificities arises from modular interactions of variable Ig domains. Cell 130, 1134–1145 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmucker D., Chen B., Dscam and DSCAM: Complex genes in simple animals, complex animals yet simple genes. Genes Dev. 23, 147–156 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mountoufaris G., Canzio D., Nwakeze C. L., Chen W. V., Maniatis T., Writing, reading, and translating the clustered protocadherin cell surface recognition code for neural circuit assembly. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 34, 471–493 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yagi T., Molecular codes for neuronal individuality and cell assembly in the brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 5, 45 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zipursky S. L., Grueber W. B., The molecular basis of self-avoidance. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 36, 547–568 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zipursky S. L., Sanes J. R., Chemoaffinity revisited: Dscams, protocadherins, and neural circuit assembly. Cell 143, 343–353 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu Q., Maniatis T., A striking organization of a large family of human neural cadherin-like cell adhesion genes. Cell 97, 779–790 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Q. et al., Comparative DNA sequence analysis of mouse and human protocadherin gene clusters. Genome Res. 11, 389–404 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ribich S., Tasic B., Maniatis T., Identification of long-range regulatory elements in the protocadherin-alpha gene cluster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19719–19724 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tasic B. et al., Promoter choice determines splice site selection in protocadherin alpha and gamma pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 10, 21–33 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X., Su H., Bradley A., Molecular mechanisms governing Pcdh-gamma gene expression: Evidence for a multiple promoter and cis-alternative splicing model. Genes Dev. 16, 1890–1905 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schreiner D., Weiner J. A., Combinatorial homophilic interaction between gamma-protocadherin multimers greatly expands the molecular diversity of cell adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 14893–14898 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thu C. A. et al., Single-cell identity generated by combinatorial homophilic interactions between α, β, and γ protocadherins. Cell 158, 1045–1059 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf H., The pectine organs of the scorpion, Vaejovis spinigerus: Structure and (glomerular) central projections. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 37, 67–80 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao G. et al., A chelicerate-specific burst of nonclassical Dscam diversity. BMC Genomics 19, 66 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yue Y. et al., A large family of Dscam genes with tandemly arrayed 5′ cassettes in Chelicerata. Nat. Commun. 7, 11252 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin Y., Li H., Revisiting Dscam diversity: Lessons from clustered protocadherins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 76, 667–680 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zondag G. C. et al., Homophilic interactions mediated by receptor tyrosine phosphatases mu and kappa. A critical role for the novel extracellular MAM domain. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 14247–14250 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonn S., Seeburg P. H., Schwarz M. K., Combinatorial expression of alpha- and gamma-protocadherins alters their presenilin-dependent processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 4121–4132 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murata Y., Hamada S., Morishita H., Mutoh T., Yagi T., Interaction with protocadherin-gamma regulates the cell surface expression of protocadherin-alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49508–49516 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawaya M. R. et al., A double S shape provides the structural basis for the extraordinary binding specificity of Dscam isoforms. Cell 134, 1007–1018 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li S. A., Cheng L., Yu Y., Wang J. H., Chen Q., Structural basis of Dscam1 homodimerization: Insights into context constraint for protein recognition. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501118 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrison O. J. et al., The extracellular architecture of adherens junctions revealed by crystal structures of type I cadherins. Structure 19, 244–256 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubinstein R. et al., Molecular logic of neuronal self-recognition through protocadherin domain interactions. Cell 163, 629–642 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brasch J. et al., Visualization of clustered protocadherin neuronal self-recognition complexes. Nature 569, 280–283 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pierce B. G. et al., ZDOCK server: Interactive docking prediction of protein-protein complexes and symmetric multimers. Bioinformatics 30, 1771–1773 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meijers R. et al., Structural basis of Dscam isoform specificity. Nature 449, 487–491 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodman K. M. et al., Protocadherin cis-dimer architecture and recognition unit diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E9829–E9837 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodman K. M. et al., Structural basis of diverse homophilic recognition by clustered α- and β-protocadherins. Neuron 90, 709–723 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicoludis J. M. et al., Structure and sequence analyses of clustered protocadherins reveal antiparallel interactions that mediate homophilic specificity. Structure 23, 2087–2098 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nicoludis J. M. et al., Antiparallel protocadherin homodimers use distinct affinity- and specificity-mediating regions in cadherin repeats 1-4. eLife 5, e18449 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicoludis J. M. et al., Interaction specificity of clustered protocadherins inferred from sequence covariation and structural analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 17825–17830 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith C. J., Watson J. D., VanHoven M. K., Colón-Ramos D. A., Miller D. M. 3rd, Netrin (UNC-6) mediates dendritic self-avoidance. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 731–737 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen W. V. et al., Pcdhαc2 is required for axonal tiling and assembly of serotonergic circuitries in mice. Science 356, 406–411 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Millard S. S., Flanagan J. J., Pappu K. S., Wu W., Zipursky S. L., Dscam2 mediates axonal tiling in the Drosophila visual system. Nature 447, 720–724 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tadros W. et al., Dscam proteins direct dendritic targeting through adhesion. Neuron 89, 480–493 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garrett A. M., Khalil A., Walton D. O., Burgess R. W., DSCAM promotes self-avoidance in the developing mouse retina by masking the functions of cadherin superfamily members. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E10216–E10224 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used for the study are available in the main text figures and SI Appendix figures and table.