Abstract

Given the recent rise in adolescent mental health issues, many researchers have turned to school-based mental health programs as a way to reduce stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms among large groups of adolescents. The purpose of the current systematic review and meta-analysis is to identify and evaluate the efficacy of school-based programming aimed at reducing internalizing mental health problems of adolescents. A total of 42 articles, including a total of 7310 adolescents, ages 11–18, met inclusion for the meta-analyses. Meta-analyses were completed for each of the three mental health outcomes (stress, depression, and anxiety) and meta-regression was used to determine the influence of type of program, program dose, sex, race, and age on program effectiveness. Overall, stress interventions did not reduce stress symptoms, although targeted interventions showed greater reductions in stress than universal programs. Overall, anxiety interventions significantly reduced anxiety symptoms, however higher doses may be necessary for universal programs. Lastly, depression interventions significantly reduced depressive symptoms, but this reduction was moderated by a combination of program type, dose, race, and age group. Although, school-based programs aimed at decreasing anxiety and depression were effective, these effects are not long-lasting. Interventions aimed at reducing stress were not effective, however very few programs targeted or included stress as an outcome variable. Implications for practice, policy and research are discussed.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Stress, Health policy, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Adolescence is the onset for many mental health problems, including anxiety and depression (Paus et al. 2008). Indeed, current statistics suggest 31.9% of adolescents ages 13–18 have been or are currently diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (Merikangas et al. 2010) and 31.5% have experienced depressive symptoms (Center for Disease Control [CDC] 2018). Recent estimates suggest an increased incidence by as much as 37% from 2005 to 2014 (Mojtabai et al. 2016). Although studies have not been conducted on the prevalence of subclinical levels of stress or anxiety in adolescence, it is likely that subclinical prevalence mirrors that of clinical diagnoses. Moreover, these disorders have high comorbidity and symptoms of one disorder may be predictive of concurrent or future development of other internalizing mental health disorders. Indeed, adolescent depressive and anxiety symptoms predict later levels of stress symptoms among adolescents (Shapero et al. 2013). Therefore, it is important to examine these disorders together in order to understand the profile of internalizing symptoms in this population. Thus, given these startling adolescent mental health statistics, it is imperative to develop programs that can provide education and support to a wide range of adolescents who may be at risk for mental health issues, particularly internalizing issues. Furthermore, reduction of stigma surrounding mental health issues must be prioritized in order to encourage adolescents experiencing internalizing problems to seek help. School-based programming is an increasingly popular and effective method of providing education and support for adolescents with elevated internalizing symptoms (Corrieri et al. 2014; Dray et al. 2017; Werner-Seidler et al. 2017) and reducing mental health stigma (Mellor 2014).

School-based programming has many unique qualities including, the ability to reach a large number of students simultaneously (Creed et al. 2011), reduced logistical constraints to conduct group therapy sessions (Creed et al. 2011), increased connectedness and social-relatedness among classmates (Curran and Wexler 2017), and the ability to create stronger, healthier relationships between students, teachers, and counselors (Durlak and Weissberg 2007; Eccles and Gootman 2002). Furthermore, school-based programs can help identify students who are at elevated risk for clinical mental health-related diagnoses and/or may need additional support beyond school-based programming. Lastly, there is evidence of a relationship between mental health and academic success; school-based mental health programs may also serve as a way to increase students’ academic performance for those experiencing mental health problems (Fletcher 2010; Needham 2009).

The current meta-analyses have not examined intervention dose, gender, or race as moderating variables of internalizing mental health programs. These variables are important as knowledge of how these factors moderate program effectiveness is essential for improving current programs and developing new programs, especially those targeting groups at higher risk for subclinical and/or clinical levels of these disorders (e.g., females, minority groups) (Merikangas et al. 2010). Another limitation of the current meta-analyses is that inclusion criteria have been restricted to randomized control trials (RCTs). Although RCTs are considered higher quality than other study designs, they are often difficult to implement in school systems (Forman et al. 2013; Werner-Seidler et al. 2017). Therefore, the inclusion of non-RCT trials is important to inform further research in this domain. Lastly, very few systematic reviews and meta-analyses have evaluated school-based stress reduction programs and do not include other internalizing symptoms that may be related to stress.

Systematic reviews conducted to date report that school-based mental health programs reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms (Arora et al. 2019; Corrieri et al. 2014; O’Connor et al. 2018), meta-analyses quantifying the efficacy of these programs report small and heterogeneous effect sizes (Dray et al. 2017; Werner-Seidler et al. 2017). In addition to overall effects (treatment vs. control), these meta-analyses have evaluated moderating effects including: program type (universal vs. targeted; Werner-Seidler et al.2017), program content (cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT] vs. other therapies; Dray et al. 2017; Werner-Seidler et al. 2017), and age (Dray et al. 2017; Werner-Seidler et al. 2017). Werner-Seidler et al. (2017) found program type was a significant moderator for depression interventions. However, there are diverging results concerning program content and age. Werner-Seidler et al. (2017) found that program content or age did not moderate program effectiveness, while Dray et al. (2017) found that school-based interventions significantly reduced anxiety symptoms in children, but not adolescents. Furthermore that CBT-based interventions were more effective than non-CBT-based interventions for both depressive and anxiety symptoms (Dray et al. 2017).

Current Study

Given the increased popularity of school-based mental health programming, understanding the efficacy of these programs and the factors that may influence them is vital to their continued success. While current meta-analyses have addressed the efficacy of these program, many factors that likely influence their effectiveness, such as race, sex, and program dose, have not been examined. The purpose of the current systematic review was to identify and evaluate the efficacy of school-based programming aimed at reducing internalizing mental health problems of adolescents (i.e., middle and high school students). The first aim was to identify themes in mental health program goals and quantify the efficacy of different types of school-based programs in reducing stress, anxiety, and depression/depressive symptoms. The second aim was to investigate the moderating effects of demographics (e.g., age, sex, ethnicity, baseline symptom level), program structure (e.g., dose, type of program), and study design (RCT vs. non-RCT) on program effectiveness. The overarching goal of the review was to identify aspects of effective programming in order to establish recommendations for programming and mental health education policies that could be implemented in a wide range of school settings.

Methods

The study was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42019111052) and adhered to PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al. 2009).

Data Sources

Consistent with the PRISMA guidelines, four databases were queried: Academic Search Premiere, ERIC, PsycINFO, and PsycARTICLES. The following search terms were used: (school counseling OR school counselor OR school setting) AND (program*) AND (high school OR middle school OR secondary*) NOT (college readiness OR college preparedness OR college student) NOT (systematic review OR meta-analysis). Additionally, recent systematic reviews (Arora et al. 2019; Corrieri et al. 2014; Erbe and Lohrmann 2015; O’Connor et al. 2018) and meta-analyses (Clarke, 2006; Dray et al. 2017; Werner-Seidler et al. 2017) were searched for additional articles meeting the criteria.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The initial search aimed to identify the goals of school-based programs in the U.S. and review current mental health programming in middle and high schools (i.e., students ages 11–18) in the U.S. The review was limited to the U.S. for two reasons (1) Differing opinions and stigmas regarding mental health between countries (Alonso et al. 2008; Pescosolido et al. 2013) may impact the results and (2) To assist with the goal of making recommendations for U.S. policy surrounding mental health education. To be considered for this review, articles must have implemented or examined programs in U.S. middle and/or high schools aimed at reducing stress, depression/depressive symptoms, anxiety, or other internalizing mental health-related problems and been published between 1990 and 2018. Reviews, epidemiology articles, non-peer reviewed articles, and studies that omitted baseline and/or posttest scores were excluded.

Data Extraction

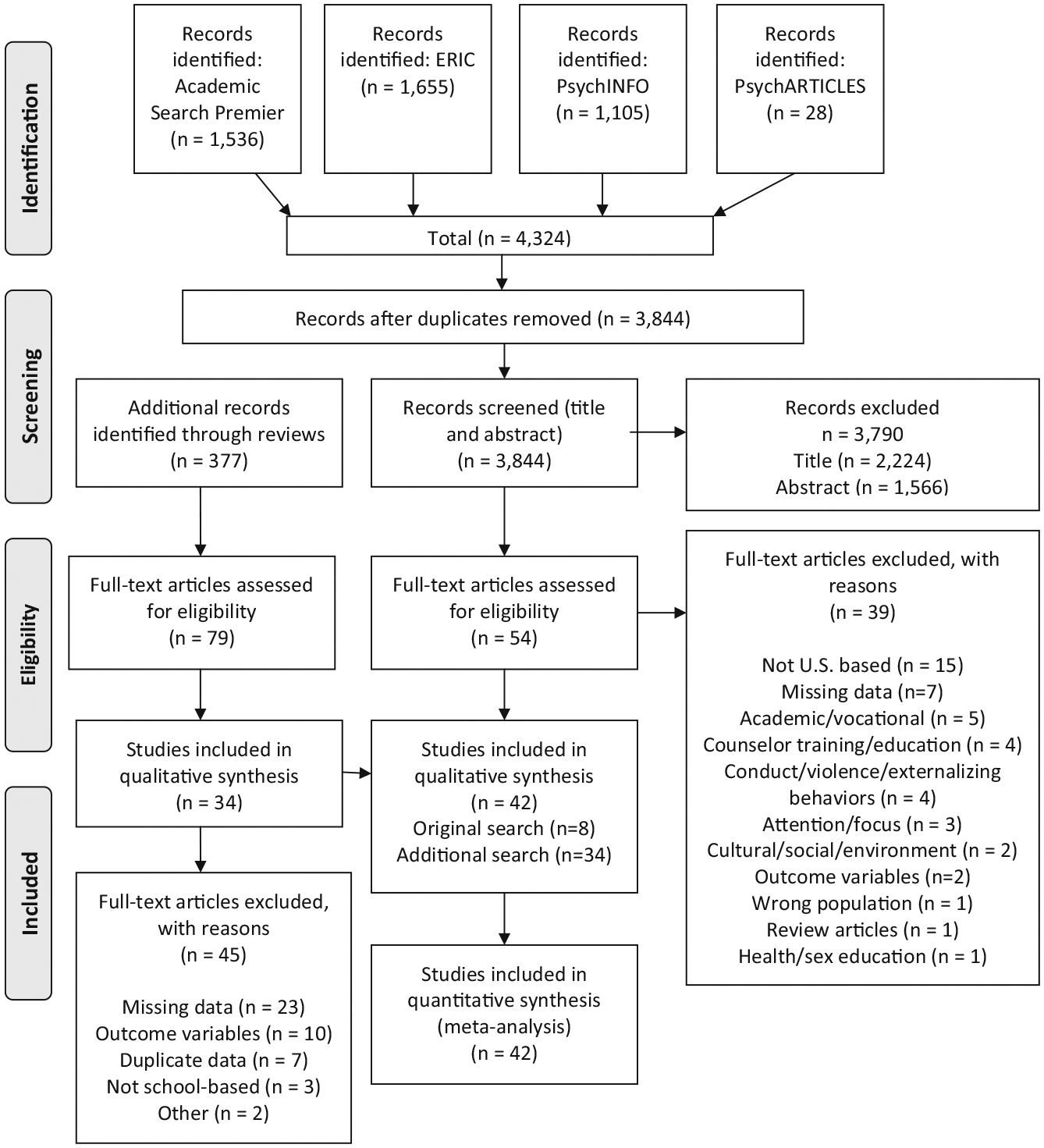

Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA Flow Diagram outlining the different stages of the identification and eligibility review. The initial search conducted on May 1, 2018, returned 4324 articles. After removing duplicates, 3844 articles were screened by title and abstract. A total of 54 articles were submitted for full-text review. Following the full-text review, a total of 39 articles were excluded for the following reasons: not in the U.S. (n = 15), did not include descriptive statistics (n = 7), academic program or vocational training (n = 5), related to counselor training or education (n = 4), examined student conduct, violence, or externalizing behaviors (n = 4), examined attention or focus (n = 3), examined cultural, social, or environmental aspects of mental health (n = 2), outcome variables did not align with the goals of the study (n = 2), discussed or evaluated a program conducted with an adult or elementary school population (n = 1), review article (n = 1), examined health education (n = 1), and examined trauma or harassment (n = 1). Another 377 articles were identified through existing reviews, 79 of these articles were assessed during a full-text review. From these, 45 articles were excluded for the following reasons: did not include descriptive statistics (n = 23), outcome variables did not align with the goals of the study (n = 10), secondary analysis of published data already included in the present study (n = 7), program was not entirely school-based (n = 3), case studies (n = 1), dissertation (n = 1). A total of 42 articles met inclusion criteria and examined the effectiveness of programs in the U.S. aimed at reducing stress, depression/depressive symptoms, or anxiety in middle school or high school students. All steps of the article selection were performed by RF, SBD, KM, ER, and MM.

Fig. 1.

The PRISMA flowchart of the article selection process

Data Analysis and Synthesis

Separate meta-analyses were completed for each of the three primary mental health outcomes (stress, depression/depressive symptoms, and anxiety). After data extraction baseline, post-test, and available follow-up scores and standard deviations were used to compute standardized effect-size estimates (Cohen’s d) (Becker 1988) for each group (i.e., control and experimental, high risk and low risk) for each included study. These effect estimates were then used to calculate standard errors and confidence intervals (Lipsey and Wilson 2001; Nakagawa and Cuthill 2007) and were visualized using a forest plot. Heterogeneity was assessed via consideration of the I2 statistic. Meta-analyses were conducted in MATLAB version R2018a (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Average effects of the experimental and control groups were compared using an independent samples t-test. Meta-regression was used to determine the significant effects (main effects and interactions) predicting changes in mental health effects with respect to the following factors: treatment (control or experimental), type of program (targeted or universal), sex (percentage of females), age (middle school/average age <14 or high school/average age >14), race (percentage of Caucasian/white), and dose (in minutes). The level of significance was set to p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Assessment of Bias

Two researchers independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions guidelines (Reeves et al. 2011; Schünemann et al. 2017). Any disagreements were resolved via discussion. Reporting bias and confidence in cumulative evidence were assessed via the GRADE approach (GRADE Working Group 2004; Guyatt et al. 2008), visual inspection of funnel plots, and a meta-regression using sample size, study ID, and control condition (i.e., active or non-active) as factors.

Results

All studies included in this literature review were published between 1990 and 2018. The results are separated by three outcome variables: stress, anxiety, and depression/depressive symptoms. A total of 42 studies were included in the meta-analyses, with a total of 7310 adolescent participants. Of the 42 studies, 38 measured depressive symptoms, 20 measured anxiety symptoms, and 4 measured stress symptoms. The dose (i.e., duration of intervention in minutes) ranged from 100 to 1800 min, with a median of 650 min and all but 7 programs were considered traditional therapy programs (e.g., CBT-based, stress inoculation). Study designs included RCTs (21 studies), CRCTs (5 studies), Quasi-Experimental (3 studies), One-group-pre-post (7 studies), and blocked randomization (6 studies). Overall 25 studies were targeted interventions and 17 were universal interventions. Follow-up evaluations (<1-year post-intervention) were included in 25 of the studies, however 2 studies did not include control groups in the follow-up and one did not include a true follow-up, as the control group completed the intervention prior to the follow-up. The study details are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study details of school-based prevention programs for stress, anxiety, and depression

| Study | N | Outcome: measures | Design | %Female | Age | %White | Dose (min) | Program content | Program name | Control | Control details | Program type | Program head | Program head details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barnes et al. (2012) | 159 | Anx: BASC-Anx | RCT | 49 | HS | 13.2 | 600 | Traditional | WLS | AC | Health education | Universal | NC | Teacher |

| Benas et al. (2016) | 186 | Dep: YSR | BR | 66.7 | HS | 36.8 | 860 | Traditional | IPT-AST | AC | Group counseling | Targeted | CL&NC | Clinical psychologists and clinical psychology doctoral students |

| Bluth et al. (2016) | 30 | Stress: PSS; Anx: 6-item STAI; Dep: SMFQ | RCT | 39 | HS | 18 | 550 | Alternative | L2B | AC | Substance abuse course | Targeted | NC | First author, mindfulness instructor |

| Britton et al. (2014) | 101 | Dep: YSR | RCT | 45.5 | MS | Not reported; primarily white school | 360 | Alternative | Asian history with mindfulness | AC | African history class | Universal | NC | Teacher |

| Cardemil et al. (2002) | 49 | Dep: CDI | RCT | 58 | MS | 0 | 1080 | Traditional | PRP-CBT based | IN | Usual care | Targeted | CL | Masters students (clinical psychology, counseling, educational psychology) |

| Chaplin et al. (2006) | 208 | Dep: CDI | RCT | 44; 100 | MS | 88 | 1080 | Traditional | PRP-all female, PRP-coed | IN | Usual care | Universal | NC | Teachers, guidance counselors, research assistants |

| Clarke et al. (1993) (Study 1) | 622 | Dep: CES-D | CRCT | 42.2 | HS | 90 | 150 | Traditional | Psychoeducation | AC | Health class | Universal | NC | Health teacher w/training |

| Clarke et al. (1993) (Study 2) | 380 | Dep: CES-D | CRCT | 40.4 | HS | 90 | 150 | Traditional | Psychoeducation + behavioral intervention | AC | Health class | Universal | NC | Health teacher w/training |

| Clarke et al. (1995) | 150 | Dep: CES-D | RCT | 70 | HS | 90 | 675 | Traditional | Coping with stress course | IN | Usual care | Targeted | CL&NC | School psychologists and counselors |

| Frank et al. (2014) | 49 | Anx: BSI; Dep: BSI | OGPP | 55.1 | HS | 2.1 | 1440 | Alternative | TLS | No Control | N/A | Targeted | NC | Certified yoga teachers with certification in TLS administration |

| Fung et al. (2016) | 19 | Dep: YSR | RCT | 55.56 | MS | 0 | 720 | Alternative | L2B | IN | Waitlist | Targeted | CL&NC | Clinical psychology graduate students with training on program |

| Gillham et al. (2006) | 271 | Dep: CDI | RCT | 53.1 | MS | 73 | 1080 | Traditional | PRP-CBT based | IN | Usual care | Targeted | CL | Child psychologist or child social worker |

| Gillham et al. (2007) | 697 | Dep: CDI | RCT | 47 | MS | 67 | 1080 | Traditional | PEP, PRP-CBT based | IN | Usual care | Universal | NC | Teachers, counselors, graduate students |

| Gillham et al. (2012) | 266 | Anx: RMCAS; Dep: CDI, RADS-2 | RCT | 48 | MS | 77 | 900 | Traditional | PRP-CBT based | IN | Usual care | Targeted | NC | School teachers/counselors, trained by staff |

| Ginsburg and Drake (2002) | 12 | Anx: ADIS-CIR, SCARED | Quasi | 83 | HS | 0 | 500 | Traditional | CBT | AC | Attention support control | Targeted | CL | Psychology graduate students trained in CBT |

| Hains (1992) | 6 | Anx: STAI-State, STAI-Trait; Dep: RADS | OGPP | 0 | HS | 83.3 | 600 | Traditional | SIT | No control | N/A | Universal | CL | Author and clinical psychology doctoral student |

| Hains (1994) | 21 | Anx: STAI-State, STAI-Trait; Dep: RADS | RCT | 74 | HS | 84.2 | 260 | Traditional | SIT | IN | Waitlist | Universal | CL | Author and clinical psychology doctoral student |

| Hains and Ellmann (1994) | 21 | Stress: APES; Anx: STAI-State, STAI-Trait; Dep: RADS | RCT | 63.6 | HS | 90.5 | 650 | Traditional | SIT | IN | Waitlist | Universal | CL | Ph.D.-level psychologist, counseling psychology doctoral student, master’s-level counseling student |

| Hains and Szyjakowski (1990) | 21 | Anx: STAI-State, STAI-Trait; Dep: BDI (modified) | RCT | 0 | HS | Not reported; primarily white school | 400 | Traditional | SIT | IN | Waitlist | Universal | CL | Authors |

| Horowitz et al. (2007) | 380 | Dep: CDI, CES-D | RCT | 54 | HS | 79 | 720 | Traditional | CB, IPT-AST | AC | Wellness course | Universal | CL | Clinical psychology graduate students |

| Hoying and Melnyk (2016) | 31 | Anx: BYI-II Anx; Dep: BYI-II Dep | OGPP | 65 | MS | 18 | 900 | Traditional | COPE healthy lifestyles TEEN | No control | N/A | Universal | NC | Health teacher w/training on COPE |

| Hoying et al. (2016) | 102 | Anx: BYI-II Anx; Dep: BYI-II Dep | OGPP | 52 | MS | 100 | 900 | Traditional | COPE + hysical Activity | No control | N/A | Universal | NC | Health teacher w/training on COPE |

| Kahn and Kehle (1990) | 68 | Dep: CDI, RADS | BR | 52.9 | MS | Not reported | 1800 | Traditional | CBT, relaxation, self-modeling | IN | Waitlist | Targeted | CL | First author, school psychologists, graduate students |

| Kiselica et al. (1994) | 48 | Stress: SOSI; Anx: STAI-Trait | Quasi | 46 | HS | 100 | 480 | Traditional | SIT | AC | Group guidance classes | Targeted | CL | School counselor, counseling psychology doctoral student |

| La Greca et al. (2016) | 14 | CES-D | OGPP | 78.6 | HS | 7.1 | 1035 | Traditional | UTalk, version of IPT-AST | No Control | N/A | Targeted | CL & NC | Clinical psychology graduate students with supervision of clinical psychologist |

| Listug-Lunde et al. (2013) | 16 | Anx: MASC; Dep: CDI | BR | 37.5 | MS | 0 | 600 | Traditional | CWD-A | IN | Usual care | Targeted | CL & NC | Indian health services mental health professional, masters-level clinical psychologist |

| McCarty et al. (2010) | 67 | Dep: CDRS, MFQ | RCT | 55.6 | MS | 66.7 | 600 | Traditional | PTA | IN | Usual care | Targeted | CL | Clinical psychology graduate students |

| McCarty et al. (2013) | 120 | Dep: MFQ | RCT | 56.5 | MS | 62.9 | 600 | Traditional | PTA | AC | Individual support program | Targeted | CL | Clinical psychology graduate students |

| Melnyk et al. (2009) | 19 | Anx: BYI-II Anx; Dep: BYI-II Dep | CRCT | 58 | HS | 0 | 350 | Traditional | COPE-CBT based | AC | Health class | Universal | NC | Health teacher w/training on COPE |

| Melnyk et al. (2013) | 779 | Anx: BYI-II Anx; Dep: BYI-II Dep | CRCT | 54.5 | HS | 8.7 | 350 | Traditional | COPE-CBT based | AC | Healthy lifestyles TEEN | Universal | NC | Health teacher w/training on COPE |

| Melnyk et al. (2014) | 16 | Anx: BYI-II Anx; Dep: BYI-II Dep | OGPP | 56 | HS | 31 | 350 | Traditional | COPE-CBT based | No Control | N/A | Targeted | CL & NC | Therapist, clinician, or teacher trained to deliver COPE program |

| Michael et al. (2016) | 20 | Anx: BASC-Anx; Dep: BASC-Dep, BDI-II | OGPP | 50 | MS | 50 | 720 | Traditional | SEED (CBT-based) | No Control | N/A | Targeted | CL & NC | Clinicians placed in schools |

| Nash (2007) | 40 | Anx: MASC-10; Dep: CDI-S | RCT | 72.5 | MS | 22.5 | 405 | Alternative | The Empower Youth Program | IN | Usual school services | Universal | NC | Advanced practice nurses specializing in MRM/MBSP |

| Noel et al. (2013) | 32 | Dep: K-SADS | RCT | 100 | MS | 41.9 | 1080 | Traditional | Talk n Time (CBT) | IN | Waitlist | Targeted | NC | Peers/teachers |

| Pössel et al. (2013) | 518 | Dep: CDI | CRCT | 62.7 | HS | 72.8 | 900 | Traditional | LARS & LISA (CBT Program) | AC | Non-CBT program, wellness course | Universal | CL | Clinical psychology graduate students |

| Puskar et al. (2003) | 89 | Dep: RADS | RCT | 82 | HS | 98.9 | 450 | Traditional | TKC (Psychoeducation) | IN | Inactive | Targeted | CL | Psychiatric nurses |

| Rohde et al. (2014) | 378 | Dep: K-SADS | RCT | 68 | HS | 72 | 360 | Traditional | CBT, bibliotherapy | IN | Informational brochure | Targeted | NC | School counselors and nurses |

| Silbert and Beiry (1991) | 323 | Stress: SSS; Anx: STAI-State | Quasi | 50 | HS | 33 | 100 | Traditional | Suicide prevention unit | IN | Waitlist | Universal | NC | Teacher, overseen by researcher |

| Stice et al. (2006) | 225 | Dep: BDI | BR | 70 | HS | 55 | 240 | Traditional | CBT | AC & IN | Bibliotherapy, SEGT, expressive writing, journaling, or waitlist control | Targeted | CL | Clinical psychology graduate students |

| Stice et al. (2008) | 341 | Dep: BDI, K-SADS | RCT | 56 | HS | 46 | 360 | Traditional | CBT, SEGT | AC & IN | Bibliotherapy or waitlist control | Targeted | CL & NC | Clinical graduate student and undergraduate |

| Young et al. (2006) | 41 | Dep: CES-D, CGAS | RCT | 85.4 | MS | Not reported; 81.6% Hispanic | 720 | Traditional | IPT-AST | AC | School counseling | Targeted | CL | First author, masters-level psychologists, or social workers |

| Young et al. (2012) | 98 | Anx: SCARED; Dep: CES-D | RCT | 77 | HS | Not reported; 92.6% Hispanic | 800 | Traditional | IPT-AST | AC | School counseling | Targeted | CL | Not reported |

| Young et al. (2016) | 186 | Dep: CES-D, CGAS | BR | 66.7 | HS | 36.8 | 860 | Traditional | IPT-AST | AC | School counseling | Targeted | CL & NC | Clinical psychologists and clinical psych doctoral students |

OGPP one-group-pretest-posttest, RCT randomized controlled trial, CRCT cluster randomized controlled trial, BR blocked randomization, MS middle school (age ≤ 14), HS high school (age < 14), WLS Williams lifeskills, IPT-AST interpersonal psychotherapy-adolescent skills training, L2B learning to BREATHE, PRP penn resiliency program, CBT cognitive behavioral therapy, TLS transformative life skills, PEP penn enhancement program, SIT stress inoculation therapy, COPE creating opportunities for personal empowerment, TEEN thinking, emotions, exercise, and nutrition, CWD-A adolescent coping with depression, PTA positive thoughts and actions, SEED student educational and emotional development, TKC teaching kids to cope, SEGT supportive-expressive group therapy, IN inactive, AC active, CL clinical, NC non-clinical, MRM modeling and role modeling, MBSP mind body spirit program

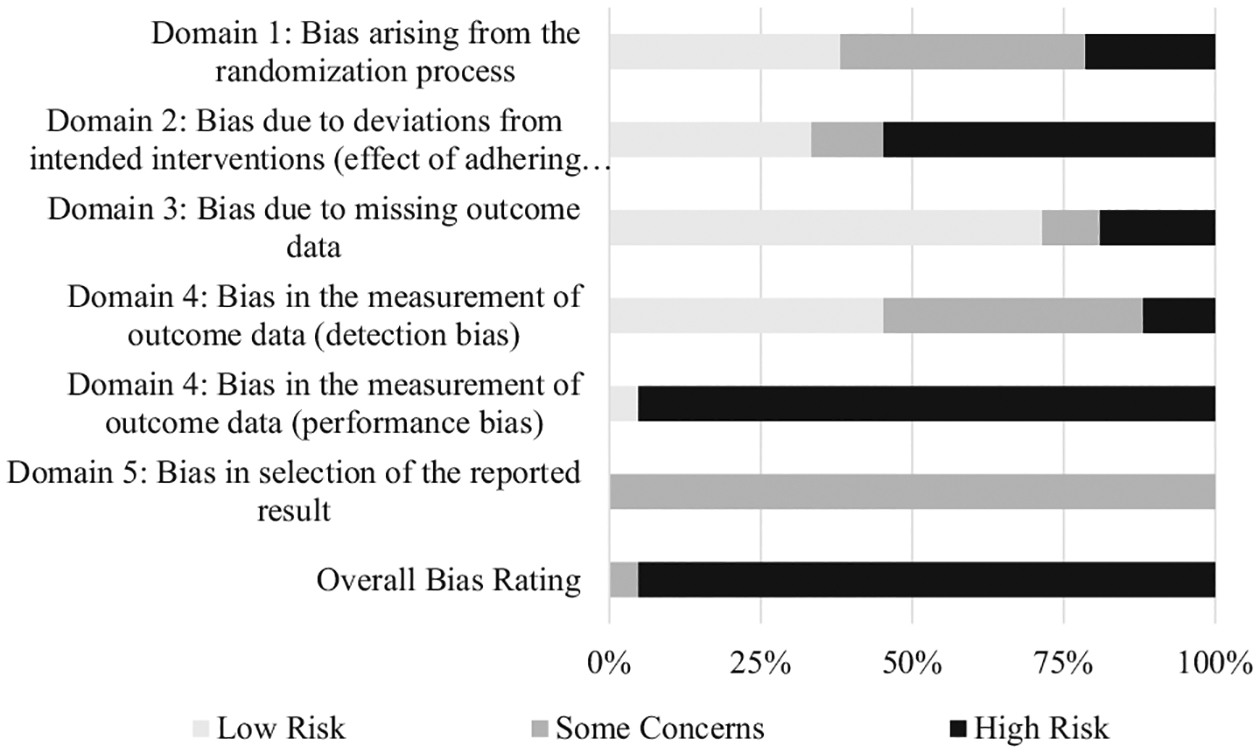

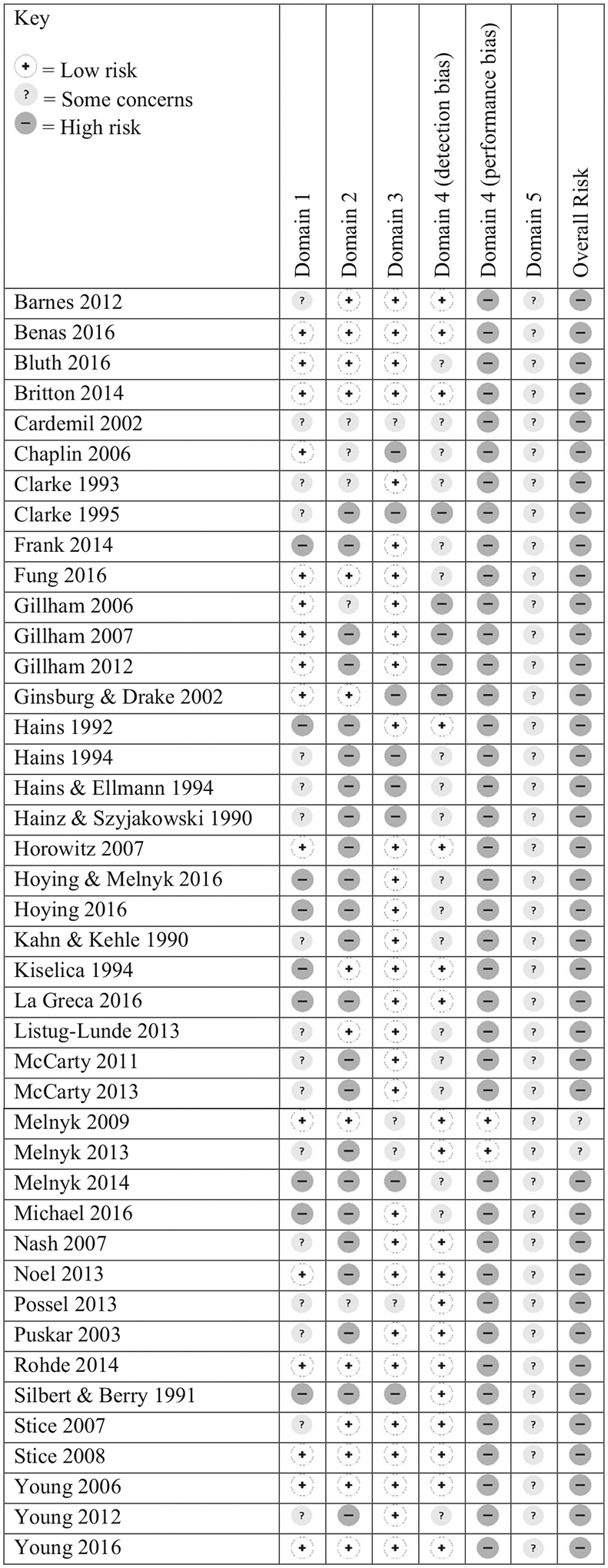

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

All 42 studies included in the meta-analyses were assessed for risk of bias using the RoB2 guidelines (see Figs S1 and S2). All but 2 studies (Melnyk et al. 2009, 2013) were rated as high risk for overall bias. This was largely due to the high risk of performance bias as the nature of these interventions make blinding participants extremely difficult and the use of self-report measures is common. Sixteen studies (38.1%) had a low risk of bias arising from the randomization process; the other 26 studies either did not specify an allocation sequence or were one group designs where randomization was not used. Over half the studies (54.8%) incurred a high risk of bias due to lack of adherence to the intervention. These studies either reported high drop-out rates, lack of attendance, or did not provide any information regarding attendance of intervention sessions. The majority of studies (71.4%) had a low risk of bias due to missing outcome data, as most studies included data for all randomized participants, or missing data was not dependent on its true value (e.g., missing data due to participants leaving the school). Less than half (45.2%) of the studies incurred a low risk of detection bias as many studies did not provide details regarding the blinding of those assessing outcome data and whether they were aware of the participants group assignment. Lastly, all studies exhibited some concerns regarding bias in the selection of the reported result, due to lack of preplanned analyses, lack of clarity regarding un-blinding of the data in the cases where outcome assessors were blind to group assignment, and the existence of multiple self-report measures for stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms.

Stress

Participants

Four studies which utilized school-based programming aimed at reducing stress, included a total of 420 adolescents, none of which included middle school aged students. The number of participants ranged from 21 (Hains and Ellmann 1994) to 323 (Silbert and Berry 1991). One study was comprised of mostly females (Hains and Ellmann 1994), another included half males and half females (Silbert and Berry 1991), while the other two had mostly male participants. Two studies included mostly Caucasian/white participants (Hains and Ellmann 1994; Kiselica et al. 1994), while the other two were comprised of mostly minority adolescents (Bluth et al. 2016; Silbert and Berry 1991). None of the studies discussed the inclusion or exclusion of adolescents with current clinical diagnoses, however all interventions included participants with and without elevated symptoms. See Table 1 for study details.

Programs

Two studies implemented a stress inoculation program led by clinically-trained professionals (Hains and Ellmann 1994; Kiselica et al. 1994), one used the Learning to BREATHE mindfulness program led by the first author (Bluth et al. 2016), and the fourth evaluated stress before and after a suicide prevention program led by school staff (Silbert and Berry 1991). Two studies used a targeted approach (Bluth et al. 2016; Kiselica et al. 1994) and the other two used a universal approach (Hains and Ellmann 1994; Silbert and Berry 1991). The interventions ranged from 100 min (Silbert and Berry 1991) to 650 min (Hains and Ellmann 1994). All four studies implemented group sessions; Hains and Ellmann (1994) also incorporated individual sessions. See Table 1 for study details.

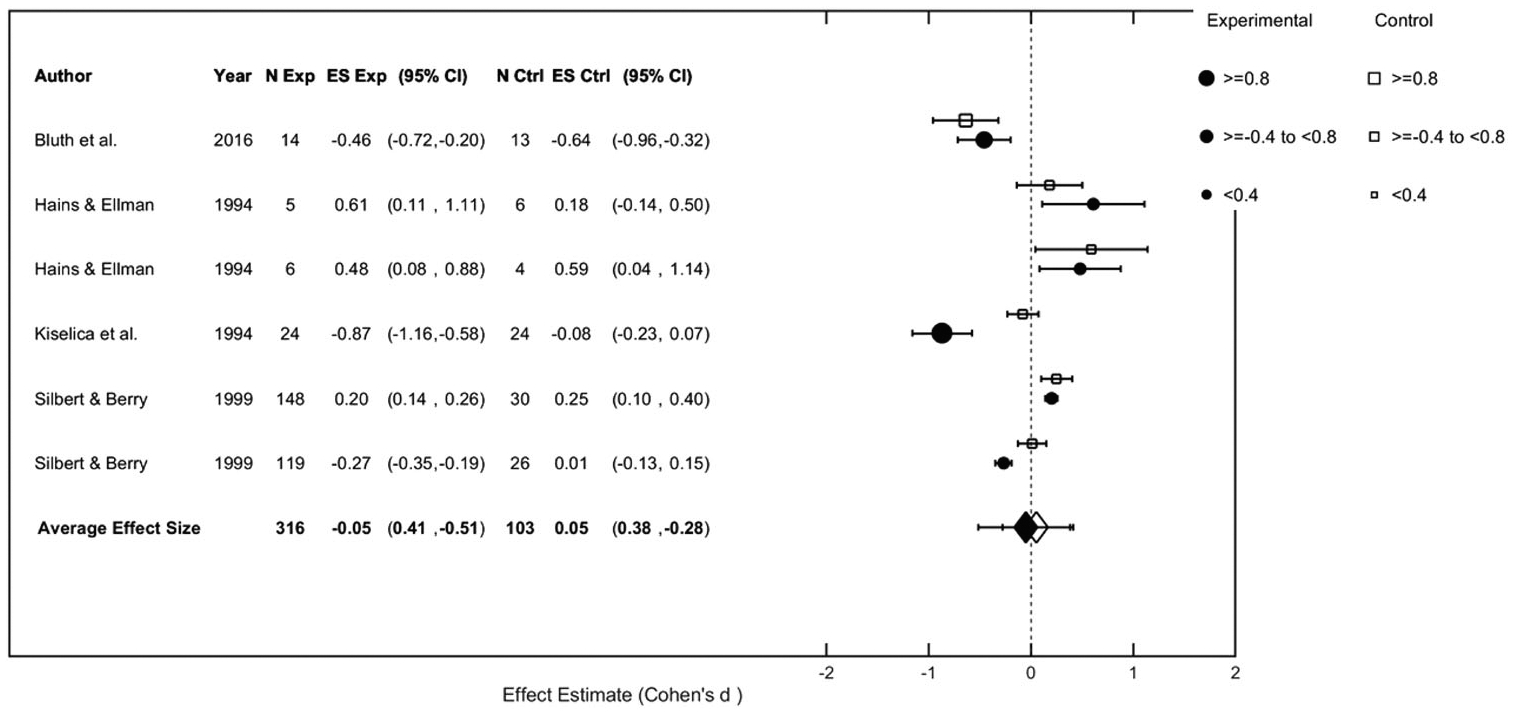

Primary meta-analysis

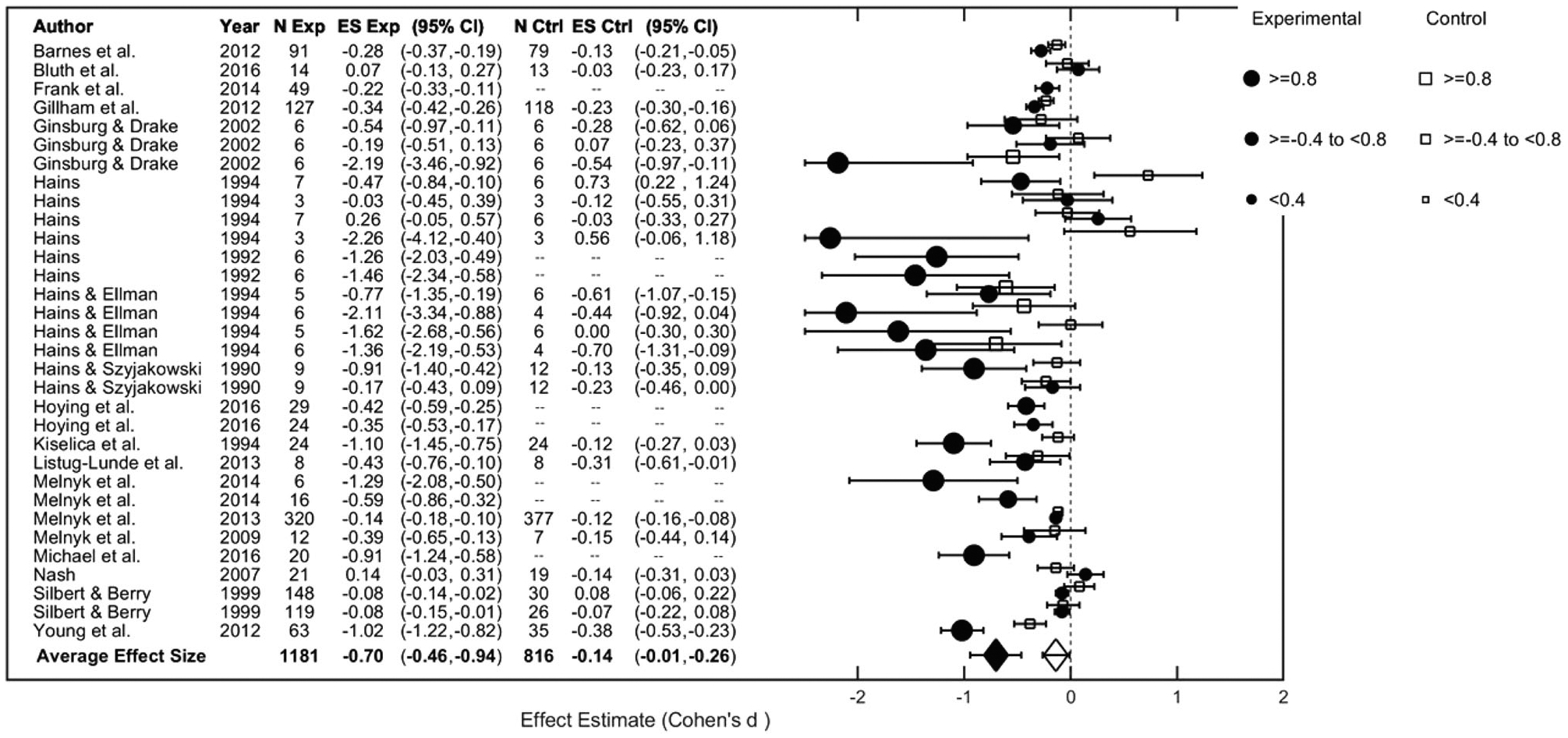

A meta-analysis compared differences in stress symptom changes for the stress interventions and control groups (see Fig. 2 for the forest plot). An assessment of variation revealed high heterogeneity among both intervention (I2 = 96.51%) and control effects (I2 = 84.54%). Overall, stress reduction interventions did not reduce stress symptoms compared to control groups (t(10) = −0.36, p = 0.73, dexp = −0.05, 95%CIexp: −0.58, 0.48, dctri = 0.05, 95% CIctrl: −0.18, 0.28). As none of the studies included a true follow-up for both experimental and control groups, a meta-analysis could not be performed on follow-up data.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias summary graph

Secondary analyses (meta-regression)

The stepwise meta-regression procedure fit a model including dose and type (F(1, 9) = 13.7, p < 0.01). The regression revealed a main effect of type (F(1, 9) = 26.8, p < 0.001) and the main effect of dose contributed to the model, but did not reach significance (F(1, 9) = 4.83, p = 0.06). Targeted interventions showed greater reductions in stress than universal programs. Notably, age was not included in the stepwise regression as none of the studies included middle school-aged participants.

Quality control

The stepwise meta-regression using sample size, study design, and control condition (i.e., active or non-active) determined that control condition influenced stress symptoms such that programs with active control groups (e.g., groups participated in general health courses, typical school-based counseling, etc.) were more effective than those with non-active control groups (F(1, 10) = 16.3, p < 0.01).

Anxiety

Participants

Twenty studies examined school-based interventions intended to reduce or help manage anxiety including a total of 2166 adolescents. Most of the studies (14 out of 20) employed high school students, with the other six using middle school students. The number of participants ranged from 6 (Hains 1992) to 779 (Melnyk et al. 2013) with an average of 108 participants. Two studies included only males (Hains 1992; Hains and Szyjakowski 1990); about half the studies were nearly evenly split between male and female participants. Five studies included all or nearly all (>80%) Caucasian/white participants and eight studies included all or nearly all minority participants. Many of the studies did specifically target minority or other at-risk adolescents, particularly African American, Hispanic, rural and/or low-income adolescents. Fourteen studies did not discuss the inclusion or exclusion of adolescents with current clinical diagnoses. Two studies specifically excluded adolescents who had a current clinical depression or anxiety diagnosis (Barnes et al. 2012; Young et al. 2012) and two studies were limited to adolescents with clinical anxiety or depression (Ginsburg and Drake 2002; Melnyk et al. 2014). Two studies did not exclude adolescents with clinical mental health diagnoses, but also included adolescents with subclinical symptoms as well (Gillham et al. 2012; Michael et al. 2016). See Table 1 for study details.

Programs

The majority (15 out of 20) of the interventions were group sessions. All studies implemented traditional programs (e.g., CBT, stress inoculation) except for three studies using alternative methods such as meditation or other holistic interventions (Bluth et al. 2016; Frank et al. 2014; Nash 2007). The programs ranged in dose from 100 min (Silbert and Berry 1991) to 1440 min (Frank et al. 2014). Nine studies employed targeted programs. Eight interventions were administered by clinically-trained professionals, 10 were led by non-clinically trained staff (e.g., school staff, mindfulness program leaders), and one used a combination of school staff and clinical professionals (Melnyk et al. 2014). See Table 1 for study details.

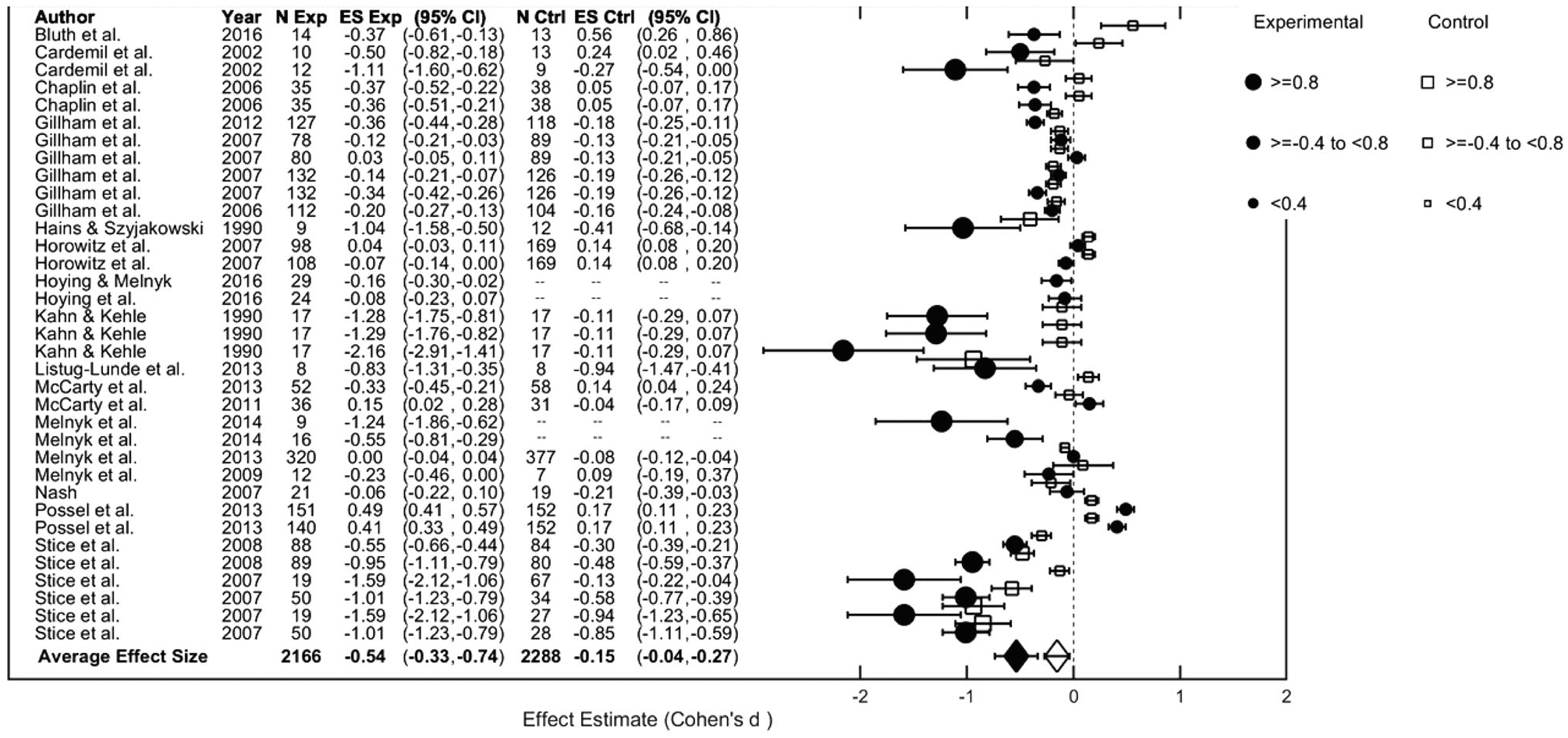

Primary meta-analysis

A meta-analysis compared differences in anxiety symptoms changes for the anxiety interventions and control groups (see Fig. 3 for the forest plot). An assessment of variation revealed high heterogeneity among intervention effects (I2 = 89.26%) and moderate to high heterogeneity among control effects (I2 = 63.24%). Anxiety reduction interventions significantly reduced anxiety symptoms compared to control groups (t(54) = −3.72, p < 0.001, dexp = −0.70, 95%CIexp: −0.94, −0.46, dctrl = −0.14, 95%CIctrl: −0.26, −0.01). Six studies included short-term follow-up data (3–6 months post-intervention) for both intervention and control groups. No differences in anxiety symptoms were present between the two groups at follow up (t(20) = −0.72, p = 0.48, dexp = −1.0, 95%CIexp: −1.29, −0.71, dctrl = −0.77, 95%CIctrl: −0.76, 0.48).

Fig. 3.

Risk of bias summary chart including judgements regarding risk of bias for all five domains of the RoB2 and the overall risk for each included study

Secondary analyses (meta-regression)

The stepwise meta-regression procedure fit a model including treatment, dose, type, and the interaction between dose and type (F(1, 51) = 5.71, p < 0.001). The regression revealed main effects of treatment (F(1, 51) = 12.43, p < 0.001) and a dose by type interaction (F(1, 51) = 5.93, p = 0.02). After accounting for the effects of treatment, dose was not related to changes in anxiety symptoms in targeted interventions (F(1, 18) = 1.17, p = 0.26). However, for universal interventions higher dose was associated with greater reduction of anxiety (F(1, 34) = 5.85, p = 0.02).

Quality control

A stepwise regression including sample size, study design, and control condition did not reveal any factors that significantly influenced the reduction in anxiety symptoms.

Depressive Symptoms and Depression

Participants

Thirty-eight studies implemented school-based programs aimed at reducing depression and/or depressive symptoms including a total of 6741 adolescents. Over half of the studies (22 out of 38) included high school students, with the other 17 using middle school students. The number of participants ranged from 6 (Hains 1992) to 779 (Melnyk et al. 2013), with an average of 173 participants. Two studies included only males (Hains 1992; Hains and Szyjakowski 1990), one study included only females (Noel et al. 2013) and another had one intervention group of only females (Chaplin et al. 2006). Again, about half the studies (20 out of 38) were nearly evenly split between male and female participants. Nine studies included all or nearly all (>80%) Caucasian/white participants and nine studies included all or nearly all minority participants. Again, many of the studies specifically targeted minority or other at-risk adolescents, particularly African American, Hispanic, rural and/or low-income adolescents. Twenty-one studies did not discuss the inclusion or exclusion of adolescents with current clinical diagnoses. Fourteen studies specifically excluded adolescents who had a current clinical depression or anxiety diagnosis and two studies were limited to adolescents with clinical anxiety or depression (Kahn and Kehle 1990; Melnyk et al. 2014). Lastly, two studies did not exclude adolescents with clinical mental health diagnoses, but also included adolescents with subclinical symptoms as well (Gillham et al. 2012; Michael et al. 2016). See Table 1 for study details.

Programs

All interventions were traditional programs (i.e., CBT-based, stress inoculation), except for five studies using alternative methods such as meditation or other holistic interventions. Additionally, one study included both CBT and alternative intervention groups (Kahn and Kehle 1990). All studies used group sessions except for Hains (1992) and Michael et al. (2016), and 6 studies incorporated individual sessions as well as group sessions (Hains 1994; Hains and Ellmann 1994; Hains and Szyjakowski 1990; La Greca et al. 2016; Young et al. 2006, 2016). Sixteen of the studies used targeted interventions while the other 22 used universal. The dose of intervention ranged from 150 (Clarke et al. 1993) to 1800 min (Kahn and Kehle 1990). Fourteen interventions were led by non-clinically trained staff (e.g., school staff, research assistants, mindfulness program leaders), four interventions were led by a combination of clinical and non-clinical personnel, and the remaining 20 interventions required a clinically-trained professional (e.g., clinical psychologist, clinical psychology graduate student). See Table 1 for study details.

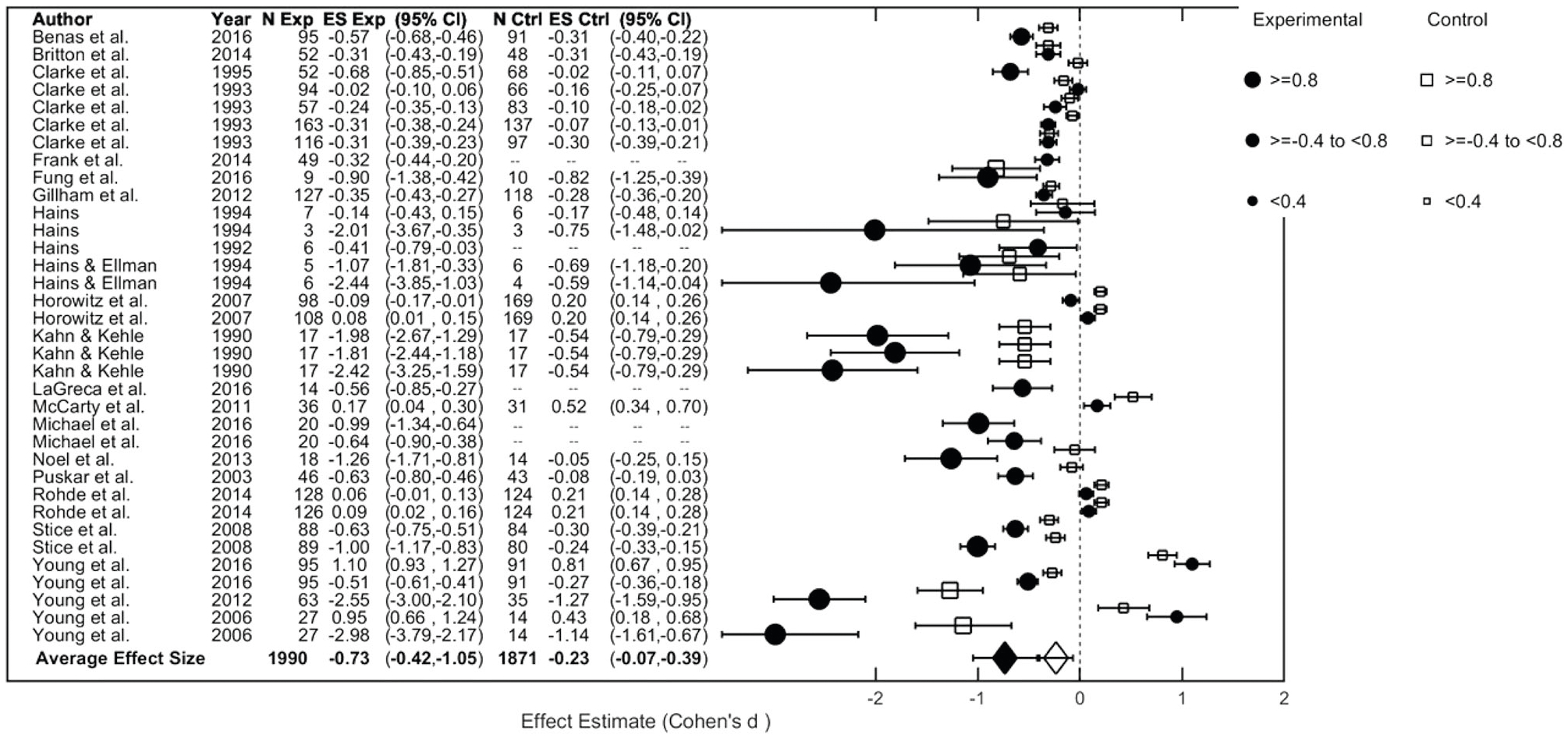

Primary meta-analysis

A meta-analysis compared differences in depressive symptom changes for the depression interventions and control groups (see Figs 4 and 5 for the forest plots). An assessment of variation revealed high heterogeneity among both intervention effects (I2 = 96.91%) and control effects (I2 = 95.07%). Depression interventions significantly reduced depressive symptoms compared to control groups (t(116) = −3.120, p < 0.01, dexp = −0.62, 95%CIexp: −0.81, −0.43, dctrl = −0.22, 95%CIctrl: −0.34, −0.10). Seventeen studies included short-term follow-up (3–8 months post-intervention) data for both intervention and control groups. No differences in anxiety symptoms were present between the two groups at follow up (t(78) = −0.009, p = 0.99, dexp = −0.56, 95%CIexp: −0.81, −0.31, dctrl = −0.56, 95%CIctrl: −0.89, −0.22).

Fig. 4.

Forrest plot of effect sizes for comparisons between intervention and control groups on changes in stress symptoms immediately post-intervention

Fig. 5.

Forrest plot of effect sizes for comparisons between intervention and control groups on changes in anxiety symptoms immediately post-intervention

Secondary analyses (meta-regression)

The stepwise meta-regression procedure fit a model with all five predictors (age, race, treatment, dose, and type) and their interactions (F(1, 81) = 4.67, p < 0.001). The regression revealed main effects of treatment (F(1, 81) = 15.34, p < 0.001), dose (F(1, 81) = 7.09, p < 0.01), and type (F(1, 81) = 9.95, p < 0.01). Additionally there were significant age by race (F(1, 81) = 4.66, p = 0.03), age by dose (F(1, 81) = 10.1, p < 0.01), age by race by type (F(1, 81) = 9.20, p < 0.01), age by dose by type (F(1, 81) = 5.58, p = 0.02), race by dose by type (F(1, 81) = 10.09, p < 0.01), and age by race by dose by type (F(1, 81) = 16.97, p < 0.001) interactions. The main effects of age and race and the other interactions contributed to the overall model but did not reach significance. To begin to parse apart the four-way age by race by dose by type interaction, a second stepwise regression was run on the middle and high school studies separately. For the middle school studies, after accounting for the effect of treatment, there was still a significant race by dose interaction (F(1, 32) = 12.68, p < 0.01), however type was no longer included in the interaction. For the high school studies, after accounting for the effect of treatment, the three-way race by dose by type interaction was still significant (F(1, 53) = 21.10, p < 0.001). While these interactions could not be further explored statistically due to insufficient data, visualization of these data provides some explanation for this four-way interaction. Studies with middle-school aged participants all had doses above 400 min and showed little variation in dose for the universal programs. Additionally, there were no targeted programs with nearly all white participants. Programs with high-school aged participants had a broader range of doses in general, however there was no variation in the dose for non-white, universal programs.

Quality control

A stepwise meta-regression procedure fit a model including study design, sample size, and the interaction between sample size and study design (F(1, 110) = 6.20, p < 0.001). There was a main effect of sample size where smaller studies exhibited greater effects while larger studies exhibited smaller effects (F(1, 110) = 12.95, p < 0.01). The one group pretest-posttest (OGPP) designs had only nine groups (from seven different studies), all with sample sizes less than 50. The estimated effect of the sample size was very large (small samples had larger effects than larger samples). This estimate was likely overinflated due to the lack of precision in the estimate because of the small number of studies and small sample sizes. In contrast, for the RCTs, there was a greater number of studies with a larger range of sample sizes (up to 169 participants) resulting in greater precision of the estimated effect of sample size. The effect of sample size for this group was attenuated compared to the OGPP Figs 6 and 7.

Fig. 6.

Forrest plot of effect sizes for comparisons between intervention and control groups on changes in depressive symptoms using the BDI, BDI-II, BYI-II, CDI, CDI-S, MFQ, or SMFQ immediately post-intervention

Fig. 7.

Forrest plot of effect sizes for comparisons between intervention and control groups on changes in depressive symptoms using the BASC-2, BSI, CDRS, CES-D, CGAS, K-SADS, RADS, RADS-2, or YSR immediately post-intervention

Discussion

The current study builds upon previous meta-analyses examining school-based anxiety and depression programs (Dray et al. 2017; Werner-Seidler et al. 2017). The study also adds to the current literature by examining the effects of dose, gender, and race on program effectiveness. The present study found that dose, and race influence the effectiveness of depression programs. Knowledge of how gender, dose, and race moderate program effectiveness is important to increase the effectiveness of future programs. For example, the implementation of culturally-sensitive practices, such as incorporating group sessions of same-race participants, may be particularly important for school-based programs that serve minority, low-income, and/or rural populations (Griner and Smith 2006; Planey et al. 2019). Overall, this study found that programs aimed at reducing depression and/or anxiety symptoms in adolescents are generally effective, however, programs for stress reduction are not. Program type influenced program efficacy for stress, anxiety, and depression, consistent with previous meta-analyses regarding anxiety and depressive symptoms (Werner-Seidler et al. 2017).

Few school-based internalizing mental health interventions have incorporated measures of stress symptoms. Although only 4 studies met criteria inclusion, the programs varied in the type of program (targeted or universal), control group (active vs. inactive), and dose; however, none of the programs were aimed at middle-school-aged adolescents. Taken together, the current stress reduction interventions are heterogeneous and are not effective in reducing student stress. With that said, the present results suggest that targeted programs were associated with greater reductions in stress, compared with universal programs and that programs with active control groups exhibited greater effects than those with inactive control groups. However, these findings are likely due to the larger effect sizes of Bluth et al. (2016) and Kiselica et al. (1994) which both implemented targeted programs with active controls. Additionally, it is important to note that these programs usually had lower doses than the programs aimed at anxiety and depressive symptoms, which may have impacted their ability to reduce symptoms of stress. Lastly, no programs used the same measure of stress, contributing to the variability in the results. Future programs should seek to increase the dose of these programs and include measures used in previous research.

While there are more school-based programs aimed at reducing anxiety evaluated presently, the programs varied greatly in dose, program type, and program personnel. Although overall these interventions were able to reduce anxiety symptoms, the efficacy of these programs was extremely variable (as indicated by the I2 = 89.26%) and these reductions were no longer present six months after the intervention. These findings are similar to those of Werner-Seidler et al. (2017) in that overall these programs were effective in reducing anxiety symptoms. However, unlike previous studies, the present meta-analysis did not find that anxiety symptoms remained decreased after a short-term follow up (Dray et al. 2017; Werner-Seidler et al. 2017). Furthermore, universal anxiety reduction programs with higher doses were more effective, but dose did not influence the effectiveness of targeted programs. These differences in dose may be due to the fact that universal programs typically have larger group sizes and heterogenous samples. Another explanation is that on average, targeted interventions were 190 min longer than universal interventions (Mtargeted = 626, SDtargeted = 249.77; Muniversal = 435.83, SDuniversal = 216.51). This could indicate that the dose necessary for a reduction in anxiety symptoms may have been met by more of the targeted programs than the universal programs.

Interventions to reduce depression/depressive symptoms were the most common of the internalizing mental health interventions evaluated presently. Overall, the interventions were successful in reducing depressive symptoms. However, these interventions varied in the type of intervention, dose, and program personnel, which likely contributed to the high variation in both the experimental (I2 = 96.91%) and control group effects (I2 = 95.07%). The present results add to the findings of Werner-Seidler et al. (2017) that targeted programs were more effective in reducing depressive symptoms than universal programs. The present results suggest that age, race, and dose moderate the effect of program type. However, due to insufficient data, it was not possible to fully decompose these interactions. Knowledge gaps are evident regarding the range of doses for middle-school programs, existence of targeted programs for mostly white students, and the range of doses for non-white, universal, high-school programs. Future research should aim to address these gaps to enable a better understanding of how demographic factors and dose may influence the effect of program type. Additionally, the quality control regression indicated that studies with smaller sample sizes and no control group showed greater reductions in depressive symptoms, indicating outcome reporting biases (Chan and Altman 2005).

Of the 42 studies meeting qualifications for the meta-analysis, less than half (16 studies) assessed more than one of the included outcome variables (stress, anxiety, and depression). Given the negative impact stress may have on adolescents likelihood to respond to CBT-based interventions (Shirk et al. 2009) and high comorbidity rates among internalizing disorders (Merikangas et al. 2010), future studies should include assessments of multiple internalizing disorders and work to incorporate stress reduction techniques to extend the positive results to those with higher stress levels.

At the individual study level, Gillham et al. (2012) observed decreases in Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) (Kovacs 2001) scores, but not Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale-2 (RADS-2) (Reynolds 2002) scores. This may point to inconsistencies and different focal points (i.e., focusing on one symptom more than another) between different measures. Given the diversity of self-report measures used to identify elevated stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, future research in this field should be informed of these differences and how they may influence results. Lastly, the slightly divergent findings regarding effects of programs on clinical levels of depression (Gillham et al. 2012; Hains 1994; Young et al. 2012) indicate a need for further research in this domain.

Limitations and Future Research

Though it is widely agreed upon that reducing both clinical and subclinical levels of stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in adolescents is extremely important, relatively few school-based efforts have been made towards this end in the U.S. Of the school-based studies evaluated presently, programs aimed at reducing stress, depression/depressive symptoms, and anxiety in adolescents appear to be effective overall. However, many of these studies have used a small sample size of adolescents, focusing on those with elevated levels of depression or anxiety symptoms. As the prevalence of these disorders in adolescents continues to rise, the development of a method of assisting these adolescents on a larger scale without decreasing the quality of care is imperative. Additionally, school-based programming should continue to include students who do not meet clinical criteria for internalizing disorders as these programs may benefit a wide range of students. For example, these programs may help prevent future instances of clinical cases by teaching coping mechanisms before a crisis occurs, reducing the stigma surrounding mental health disorders through psychoeducation, as well as assisting students who may be falling just under the clinical radar. Additionally, schools usually prefer universal programs (Horowitz et al. 2007), which eliminate the need to screen participants. Lastly, although the present results suggest that universal programming is less effective than targeted programming, this may be due to the fact that the majority of participants in universal programs do not exhibit elevated symptoms, and therefore there may be a floor effect to the degree of symptom reduction possible. Interestingly, many of the programs targeted underserved populations such as racial minorities or rural communities, however, the socioeconomic status of many of the study participants was not available. Future studies should continue to support programs for these populations as they may experience higher rates of mental health issues than the typical population (Center for Disease Control 2018; Garcia et al. 2008; Ivey-Stephenson et al. 2017).

Although there are many benefits to school-based programs (Creed et al. 2011; Curran and Wexler 2017; Durlak and Weissberg 2007; Eccles and Gootman 2002), studies did note limitations of school-based programming. Researchers have noted the difficulty in scheduling around students’ classes, school cancellations, and holidays (Chu et al. 2009; Garcia et al. 2010). Additionally, many programs required access to a clinical mental health professional or graduate student in a clinical program (i.e., psychologist, psychiatrist, counseling graduate student). Many schools, especially those in lower SES or rural areas, may not have the access or funding necessary to implement these types of programs. Future programs should aim to be flexible enough to accommodate varying school and student schedules and may want to consider a program that can be implemented without direct contact with a clinical mental health professional (i.e., telehealth). Furthermore, peer-based programs may be an effective way to reduce stigma and improve mental health outcomes across a broad population for schools with limited resources.

All studies included at least some risk of bias, suggesting the need for higher quality research methods and reporting in this domain. However, much of the bias was due to lack of information or lack of clarity in the information provided. For example, nearly all studies including multiple groups stated that random assignment was used, but did not specify the allocation method. Additionally, many studies lack information regarding session attendance, the blinding of outcome assessors, and the un-blinding of the data in the cases that blinding did occur. Future studies should clarify these aspects to allow for a better assessment of the quality of their research.

Although this systematic review and meta-analysis addressed some important gaps in the literature, there are some limitations. One limitation is the dichotomization of age in the meta-regressions, which was necessary because of inconsistencies in the reporting of age across studies (e.g., some studies reported an age range of their participants, others reported a mean age). Future meta-analyses incorporating age should treat age as a continuous variable, if possible, to provide insights regarding differences across the full age range. Another limitation was the inclusion of only U.S.-based interventions. While factors that may be unique to the U.S. (e.g., racial disparities) were examined presently, generalizability of the findings are limited to U.S. adolescents and excludes several school-based intervention studies from other countries. Lastly, we were unable to examine the effect of SES or environment (rural vs. urban) due to a lack of or inconsistencies in reporting these variables. Given the impact of low SES and rural environments on the mental health status of adolescents (Douthit et al. 2015; Priester et al. 2016; Reiss 2013), future studies should ensure both SES of participants and their environment are adequately described.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Schools

Overall, the school-based programs aimed at decreasing internalizing mental health symptoms including stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms were effective in both healthy adolescents and those with elevated mental health symptoms. As the prevalence of these mental health disorders continues to increase among adolescents, both education and health policies must be put into place to assist in the prevention, detection, and treatment of these disorders. Mental health education should continue to be included in school curriculums. For example, “blocked approach” may be appropriate for universal treatments and embedded into a health unit vs. weekly extended session may be more appropriate for targeted treatments (consistent with outpatient therapies) and could be implemented as elective courses or after-school activities.

State-level policies such as those implemented by New York (Bill Number: A03887B) and Virginia (Bill Number: SB953), in which schools are required to provide mental health education may improve student outcomes (Jorm 2012) and reduce mental health stigma (Mellor 2014). Research should continue to build upon and improve the current programs in efforts to reduce mental health issues among adolescents and support policies requiring mental health education and suicide prevention programs in schools.

Conclusion

Previous meta-analyses have examined reductions in anxiety and depressive symptoms, however, these studies have not considered program dose, race, or gender as moderating factors of symptom reduction. The current meta-analysis investigated the effectiveness of school-based interventions on stress, anxiety, and depressive symptom interventions in adolescents. School-based interventions aimed at reducing stress among adolescents were not effective, however fewer studies have investigated stress reduction programs, compared with the number aimed at reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms. In line with previous findings, school-based programs were effective in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescents. For anxiety, program type and dose influenced effectiveness. For depressive symptoms, effectiveness was moderated by a combination of participant age, race, dose, and program type. However, how each of these factors influenced the reduction of symptoms was not entirely clear. The present findings provide additional support that school-based programs can reduce anxiety and depression and that both demographic and program characteristics influence the efficacy school-based mental health programs. The present study highlights effective methods for tackling the growing issue of mental health burdens among adolescents while also exposing new gaps in the current literature and school-based programming.

Biography

Robyn Feiss is a doctoral candidate in Kinesiology with a concentration in sport psychology at Auburn University under Dr. Melissa Pangelinan. Her research interests include the relationships between mental and physical health in adolescents, particularly the role of stress in injury amongadolescent and college athletes.

Sarah Beth Dolinger is an undergraduate research fellow at Auburn University. Her researchinterests include the relationship between mental health burdens and physical health burdens, and how these factors impact injury and rehabilitation.

Monaye Merritt is a doctoral student at Auburn University. Her major research examines resilience and performance psychology.

Elaine Reiche is an Athletic Trainer in Nashville, Tennessee working with youth and adultathletics. She was an Athletic Trainer with Team USA Handball while completing her masters at Auburn University. Her research interests include physiological adaptation in muscle during injury and rehabilitation.

Karley Martin completed her masters at Auburn University and is currently an Athletic Trainer at The Orthopaedic Clinic in Auburn, Alabama. Her research interests include ACL prevention andmanagement, sport-related concussions, biomechanics, orthopedic injuries and rehabilitation.

Julio A. Yanes is a graduate research assistant at Auburn University. His research interests include behavioral and neuroimaging meta-analyses, functional neuroimaging, cannabis, and pain.

Chippewa M. Thomas is an Associate Professor of Counselor Education in the Department of Special Education, Rehabilitation, and Counseling at Auburn University. Dr. Thomas’ research examines culturally competent counseling practice, social justice in action, community engagement/publicly-engaged scholarship, and wellness/vitality in higher education. She isactively involved with and presents at professional counseling, education and outreach and engaged scholarship conferences. She is roster-listed as a Fulbright Specialist in Counselor Education.

Melissa M. Pangelinan is an Assistant Professor in the School of Kinesiology at Auburn University. Her research examines the impact of motor skill and physical activity interventions on brain development as well as mental and physical health outcomes in pediatric populationswith and without developmental disabilities and acquired neurological conditions.

Footnotes

Data Sharing and Declaration The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Alonso J, Buron A, Bruffaerts R, He Y, Posada-Villa J, & Lepine JP et al. (2008). Association of perceived stigma and mood and anxiety disorders: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 118(4), 305–314. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora PG, Collins TA, Dart EH, Hernández S, Fetterman H, & Doll B (2019). Multi-tiered systems of support for school-based mental health: a systematic review of depression interventions. School Mental Health. 10.1007/s12310-019-09314-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes VA, Johnson MH, Williams RB, & Williams VP (2012). Impact of Williams LifeSkills® training on anger, anxiety, and ambulatory blood pressure in adolescents. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 2(4), 401–410. 10.1007/s13142-012-0162-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker BJ (1988). Synthesizing standardized mean-change measures. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 41, 257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Benas JS, McCarthy AE, Haimm CA, Huang M, Gallop R, & Young JF (2016). The depression prevention initiative: impact on adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms in a randomized trial. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 48(1), 1–15. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1197839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluth K, Campo RA, Prutenau-Malinici S, Reams A, Mullarkey M, & Broderick PC (2016). A school-based mindfulness pilot study for ethnically diverse at-risk adolescents. Mindfulness, 7(1), 90–104. 10.1007/s12671-014-0376-1.A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton WB, Lepp NE, Niles HF, Rocha T, Fisher NE, & Gold JS (2014). A randomized controlled pilot trial of classroom-based mindfulness meditation compared to an active control condition in sixth-grade children. Journal of School Psychology, 52(3), 263–278. 10.1016/j.jsp.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardemil EV, Reivich KJ, & Seligman MEP (2002). The prevention of depressive symptoms in low-income minority middle school students rationale for working with low-income minorities. Prevention & Treatment, 5, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Survelliance—United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 1–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A, & Altman DG (2005). Identifying outcome reporting bias in randomised trials on PubMed: review of publications and survey of authors. BMJ, 330(7494), 753 10.1136/bmj.38356.424606.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Gillham JE, Reivich K, Elkon AGL, Freres DR, Winder B, & Seligman MEP (2006). Depression prevention for early adolescent girls a pilot study of all girls versus co-ed groups. Journal of Early Adolescence, 26(1), 110–126. 10.1177/0272431605282655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BC, Colognori D, Weissman AS, & Bannon K (2009). An initial description and pilot of group behavioral activation therapy for anxious and depressed youth. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 16(4), 408–419. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AT (2006). Coping with interpersonal stress and psychosocial health among children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(1), 11–24. 10.1007/s10964-005-9001-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GN, Hawkins W, Murphy M, & Sheeber LB (1993). School-based primary prevention of depressive symptomology in adolescents: findings from two studies. Journal of Adolescent Research, 8(2), 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GN, Hawkins W, Murphy M, Sheeber LB, Lewinsohn PM, & Seeley JR (1995). Targeted prevention of unipolar depressive disorder in an at-risk sample of high school adolescents: a randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(3), 312–321. 10.1097/00004583-199503000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrieri S, Heider D, Conrad I, Blume A, König HH, & Riedel-Heller SG (2014). School-based prevention programs for depression and anxiety in adolescence: a systematic review. Health Promotion International, 29(3), 427–441. 10.1093/heapro/dat001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed TA, Reisweber J, & Beck Aaron, T. (2011). Cognitive therapy for adolescents in school settings (Vol. 17). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Curran T, & Wexler L (2017). School-based positive youth development: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of School Health, 87(1), 71–80. 10.1111/josh.12467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, & Biswas S (2015). Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health, 129(6), 611–620. https://doi.org/10.1016Zj.puhe.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dray J, Bowman J, Campbell E, Freund M, Wolfenden L, & Hodder RK, et al. (2017). Systematic review of universal resilience-focused interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health in the school setting. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(10), 813–824. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, & Weissberg RP (2007). The impact of after-school programs that promote personal and social skills. Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) 10.3102/0034654308325693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, & Gootman JA (2002). Community programs to promote youth development. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erbe R, & Lohrmann D (2015). Mindfulness meditation for adolescent stress and well-being: a systematic review of the literature with implications for school health programs. Health Educator, 47(2), 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM (2010). Adolescent depression and educational attainment: results using sibling fixed effects. Health economics, 19 (2009), 855–871. 10.1002/hec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman SG, Shapiro ES, Codding RS, Gonzales JE, Reddy LA, & Rosenfield SA, et al. (2013). Implementation science and school psychology. School Psychology Quarterly, 28, 77–100. 10.1037/spq0000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JL, Bose B, & Schrobenhauser-Clonan A (2014). Effectiveness of a school-based yoga program on adolescent mental health, stress coping strategies, and attitudes toward violence: findings from a high-risk sample. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 30(1), 29–49. 10.1080/15377903.2013.863259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fung J, Guo S, Jin J, Bear L, & Lau A (2016). A pilot randomized trial evaluating a school-based mindfulness intervention for ethnic minority youth. Mindfulness, 7(4), 819–828. 10.1007/s12671-016-0519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C, Pintor JK, & Lindgren S (2010). Feasibility and acceptability of a school-based coping intervention for latina adolescents. Journal of School Nursing, 26(1), 42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C, Skay C, Sieving R, Naughton S, & Bearinger LH (2008). Family and racial factors associated with suicide and emotional distress among Latino students. Journal of School Health, 78 (9), 487–495. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham JE, Hamilton J, Freres DR, Patton K, & Gallop R (2006). Preventing depression among early adolescents in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled study of the penn resiliency program. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34 (2), 203–219. 10.1007/s10802-005-9014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham JE, Reivich KJ, Brunwasser SM, Freres DR, Chajon ND, & Kash-MacDonald VM et al. (2012). Evaluation of a group cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for young adolescents: a randomized effectiveness trial. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(5), 621–639. 10.1080/15374416.2012.706517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham JE, Reivich KJ, Freres DR, Chaplin TM, Shatte AJ, & Samuels B et al. (2007). School-based prevention of depressive symptoms: a randomized controlled study of the effectiveness and specificity of the penn resiliency program. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 75(1), 9–19. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.9. School-Based. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg GS, & Drake KL (2002). School-based treatment for anxious African-American adolescents: a controlled pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(7), 768–775. 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRADE Working Group (2004). Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ, 328, 1490–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, & Smith TB (2006). Culturally adapted mental health intervention: a meta-analytic review. Special issue: culture, race, and ethnicity in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 43, 531–548. 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, & Schunemann HJ (2008). GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ, 336, 924–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains AA (1992). A stress inoculation training program for adolescents in a high school setting: a multiple baseline approach. Journal of Adolescence, 15(2), 163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains AA (1994). The effectiveness of a school-based, cognitive-behavioral stress management program with adolescents reporting high and low levels of emotional arousal. School Counselor, 42(2), 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hains AA, & Ellmann SW (1994). Stress inoculation training as a preventative intervention for high school youths. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 8(3), 219–232. 10.1891/0889-8391.8.3.219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hains AA, & Szyjakowski M (1990). A cognitive stress-reduction intervention program for adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 37(1), 79–84. 10.1037/0022-0167.37.1.79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JL, Garber J, Ciesla JA, Young JF, & Mufson L (2007). Prevention of depressive symptoms in adolescents: a randomized trial of cognitive—behavioral and interpersonal prevention programs. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 75(5), 693–706. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoying J, & Melnyk BM (2016). COPE: a pilot study with urban-dwelling minority sixth-grade youth to improve physical activity and mental health outcomes. Journal of School Nursing, 32(5), 347–356. 10.1177/1059840516635713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoying J, Melnyk BM, & Arcoleo K (2016). Effects of the COPE cognitive behavioral skills building TEEN program on the healthy lifestyle behaviors and mental health of appalachian early adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 30(1), 65–72. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Crosby AE, Jack SPD, Haileyesus T, & Kresnow-Sedacca M (2017). Suicide trends among and within urbanization levels by sex, race/ethnicity, age group, and mechanism of death—United States, 2001–2015. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 66(18), 1–16. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6618a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF (2012). Mental health literacy: empowering the community to take action for better mental health. American Psychologist, 67, 231–243. 10.1037/a0025957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JS, & Kehle TJ (1990). Comparison of cognitive-behavioral, relaxation, and self-modeling interventions for depression. School Psychology Review, 19(2), 196–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kiselica MS, Baker SB, Thomas RN, & Reedy S (1994). Effects of stress inoculation training on anxiety, stress, and academic performance among adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41(3), 335–342. 10.1037/0022-0167.41.3.335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M (2001). Children’s depression inventory manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Ehrenreich-May J, Mufson L, & Chan S (2016). Preventing adolescent social anxiety and depression and reducing peer victimization: intervention development and open trial. Child and Youth Care Forum, 45(6), 905–926. 10.1007/s10566-016-9363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, & Wilson DB (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Listug-Lunde L, Vogeltanz-Holm N, & Collins J (2013). A cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in rural American Indian middle school students. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 20(1), 16–34. 10.5820/aian.2001.2013.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Violette HD, Duong MT, Cruz RA, & McCauley E (2013). A randomized trial of the positive thoughts and action program for depression among early adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(4), 554–563. 10.1080/15374416.2013.782817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Violette HD, & McCauley E (2010). Feasibility of the positive thoughts and actions prevention program for middle schoolers at risk for depression. Depression Research and Treatment, 2011 10.1155/2011/241386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor C (2014). School-based interventions targeting stigma of mental illness: systematic review. Psychiatric Bulletin, 38(4), 164–171. 10.1192/pb.bp.112.041723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk B, Jacobson D, Kelly S, O’Haver J, Small L, & Mays MZ (2009). Improving the mental health, healthy lifestyle choices, and physical health of hispanic adolescents: a randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of School Health, 79(12), 575–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk BM, Jacobson D, Kelly S, Belyea M, Shaibi G, & Small L et al. (2013). Promoting healthy lifestyles in high school adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(4), 407–415. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk BM, Kelly S, Lusk P, Melnyk BM, Kelly S, & Lusk P (2014). Outcomes and feasibility of a manualized cognitive-behavioral skills building intervention: group COPE for depressed and anxious adolescents in school settings. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 27(1), 3–13. 10.1111/jcap.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K, Jian-ping H, Burstein M, Swanson S, Avenevoli S, & Lihong C et al. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in us adolescents: results from the national comorbidity study-adolescent supplement. Journal of the American Academy Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017.Lifetime. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael K, George M, Splett J, Jameson J, Sale R, & Bode A et al. (2016). Preliminary outcomes of a multi-site, school-based modular intervention for adolescents experiencing mood difficulties. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 25, 1903–1915. 10.1007/s10826-016-0373-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, & Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. (2009). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, & Han B (2016). National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics, 138(6), e20161878 10.1542/peds.2016-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, & Cuthill IC (2007). Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biological Reviews, 82(4), 591–605. 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash KA (2007). Implementation and evaluation of the empower youth program. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 25(1), 26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL (2009). Adolescent depressive symptomatology and young adult educational attainment: an examination of gender differences. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(2), 179–186. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel LT, Rost K, & Gromer J (2013). Depression prevention among rural preadolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. School Social Work Journal, 38(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor CA, Dyson J, Cowdell F, & Watson R (2018). Do universal school-based mental health promotion programmes improve the mental health and emotional wellbeing of young people? A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(3–4), e412–e426. 10.1111/jocn.14078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Keshavan M, & Giedd JN (2008). Why do many psychiatric disroders emerge during adolescence? Nature Review Neuroscience, 9(12), 947–957. 10.1038/nrn2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, Medina TR, Martin JK, & Long JS (2013). The “backbone” of stigma: identifying the global core of public prejudice associated with mental illness. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 853–860. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planey AM, Smith SMN, Moore S, & Walker TD (2019). Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking among African American youth and their families: a systematic review study. Children and Youth Services Review, 101, 190–200. 10.1016/jxhildyouth.2019.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pössel P, Martin NC, Garber J, & Hautzinger M (2013). A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral program for the prevention of depression in adolescents compared to non-specific and no-intervention control conditions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priester MA, Browne T, Iachini A, Clone S, DeHart D, & Seay KD (2016). Treatment access barriers and disparities among individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: an integrative literature review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 61, 47–59. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puskar K, Sereika S, & Tusaie-Mumford K (2003). Effect of the teaching kids to cope (TKC) program on outcomes of depression and coping among rural adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 16(2), 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves B, Deeks J, Higgins J, & Wells G (2011). Chapter 13: Including non-randomised studies In Higgins J & Green S (Eds), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Version 5). The Cochrane Collaboration. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss F (2013). Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Social Science and Medicine, 90, 24–31. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM (2002). Reynolds adolescent depression scale. 2nd edn Odessa, FL: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Stice E, Shaw H, & Briere FN (2014). Indicated cognitive-behavioral group depression prevention compared to bibliotherapy and brochure control: acute effects of an effectiveness trial with adolescents. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 82(1), 65–74. 10.1002/cyto.a.20594.Use. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Higgins JPT, Vist GE, Glasziou P, Akl E, & Guyatt GH (2017). Chapter 11: Completing ‘summary of findings’ tables and grading the confidence in or quality of the evidence In Higgins J, Churchill R, Chandler J, & Crumpston M (Eds), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Version 5). The Cochrane Collaboration. [Google Scholar]