ABSTRACT

Antibodies play a critical protective role in the host response to blood-stage malaria infection. The role of cytokines in shaping the antibody response to blood-stage malaria is unclear. Interferon lambda (IFNλ), a type III interferon, is a cytokine produced early during blood-stage malaria infection that has an unknown physiological role during malaria infection. We demonstrate that B cell-intrinsic IFNλ signals suppress the acute antibody response, acute plasmablast response, and impede acute parasite clearance during a primary blood-stage malaria infection. Our findings demonstrate a previously unappreciated role for B cell intrinsic IFNλ-signaling in the initiation of the humoral immune response in the host response to experimental malaria.

KEYWORDS: Malaria, plasmodium, type III interferon, interferon-λ, humoral immune response

Introduction

Malaria has the highest incidence, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of any human parasitic infection [1]. Plasmodium-specific antibodies protect against clinical disease but are short-lived after natural infection, suggesting a defect in the memory phase of the humoral response [2–7]. During primary infection, the first antibodies to appear in plasma are generated by short-lived effector B cells (“plasmablasts”) [8]. In contrast, the memory phase of the humoral response is primarily driven by B cells that can be generated in a germinal center (GC) and survive to become either memory B cells or long-lived plasma cells [9–12]. In experimental systems, individual B cell clones with identical B cell receptors (BCR) can both enter into the memory compartment or form plasmablasts early after activation [11,13,14], suggesting that environmental cues extrinsic to the cell are a potential determinant for B cell fate decisions. Insight into the early factors that shape early B cell responses is important for understanding the basis for the poor humoral memory observed after blood-stage malaria infection, a critical obstacle for the development of an effective vaccine.

The cytokine environment where a naive B cell encounters its cognate antigen is important for the initial B cell response [15,16]. Interferons (IFNs) are among the first cytokines produced by the innate immune system in response to infection [17], are abundant during early blood-stage malaria [18], and are therefore logical candidates to influence early Plasmodium-specific B cell fate decisions. There are three families of IFNs: Type I (IFN⍺/β), Type II (IFNγ) and Type III IFN (IFNλ). Despite substantial overlap in the gene programs induced by all IFNs, IFN signaling occurs via three distinct family-specific receptors, and each IFN family can have different effects on the B cell response depending on the context of the immune stimulus [19]. For example, Type I IFN signals in B cells are critical for lymphocyte retention inside lymph nodes [20], development of alloantibodies to exogenous antigens on erythrocytes [21], and initiation of the humoral response during influenza infection [22]. In contrast, blocking Type I IFN signals has been demonstrated to improve humoral function in the context of chronic LCMV infection [23]. For blood-stage malaria infection, our group and others have determined that Type I IFN signals enhance parasite clearance [24–27] whereas other groups have had different results [28,29]. Similar to Type I IFN, Type II IFN can also have different effects on the humoral response depending on the biological context. In both human and murine Plasmodium infection, excess IFNγ signaling has been linked to poorly functional “atypical” memory B cells and reduced antibody formation [30–32]. Additionally, decreased IFNγ signaling is associated with fewer GCs and reduced antibody output in response to either alloantigens or autoantigens [33–35].

In comparison to Type I and Type II IFN, much less is known about how IFNλ (Type III IFN) influences in vivo humoral responses. IFNλ plays a critical in host protection against rotavirus infection in enterocytes and is important for limiting influenza replication in the respiratory epithelia, suggesting a critical role at barrier interfaces [36–38] . The role of IFNλ likely extends beyond the direct effects at mucosal surfaces, however, and likely has important implications for the humoral response. B cells express IFNλ receptor mRNA [39], IFNλ activates B cells in vitro [17,39], and exogenous IFNλ reduces antibody secretion during stimulation with influenza antigens [40]. The magnitude of long-term antibody titers following acute LCMV infection was not affected by IFNλ signals, however, but the role of IFNλ for the acute antibody response is unknown [41]. While IFNλ is one of the top five differentially regulated cytokines in the blood of patients with febrile malaria (as compared to non-febrile malaria) [18], the consequences of IFNλ signals for the host response to blood-stage malaria have not been previously investigated.

Understanding the interplay between IFNλ, blood-stage malaria, and the B cell response is important because polymorphisms in the human IFNλ locus are associated with the immune response to both infections and vaccinations. Strong evolutionary pressure is thought to have caused the striking regional segregation in the population genetics of IFNλ and genetic variation in the IFNλ locus largely explains the poor response to immunotherapy treatment for hepatitis C in patients of African descent [42–44]. While there is consensus that alleles more common in African populations are associated with lower expression of IFNλ, the evolutionary pressures driving this variation are unclear [40,45–47].

IFNλ signals via a specific receptor, the IFNλR which is formed when the the IFNλR1 subunit combines with the beta subunit of the IL-10 receptor to form a functional heterodimer [48]. Mice with a targeted ablation of the IFNλR1 (Ifnlr1−/-) are therefore incapable of responding to IFNλ in a manner similar to mice with targeted disruption of all IFNλ cytokines (Ifnl2−/-/Ifnl3−/-) [37,49]. To explore the potential role that IFNλ plays in the humoral response to blood-stage malaria infection, we infected Ifnlr1−/- mice with Plasmodium yoelii as model non-lethal blood-stage malaria infection. We observed that the absence of IFNλ signaling decreased parasite burden, increased early antibody titers, and increased the number of malaria-specific plasmablasts. Furthermore, these responses depended upon B cell-intrinsic expression of IFNλR in vivo. Our data clearly show that IFNλ signals have strong influence on the acute B cell response during blood-stage malaria infection.

Results

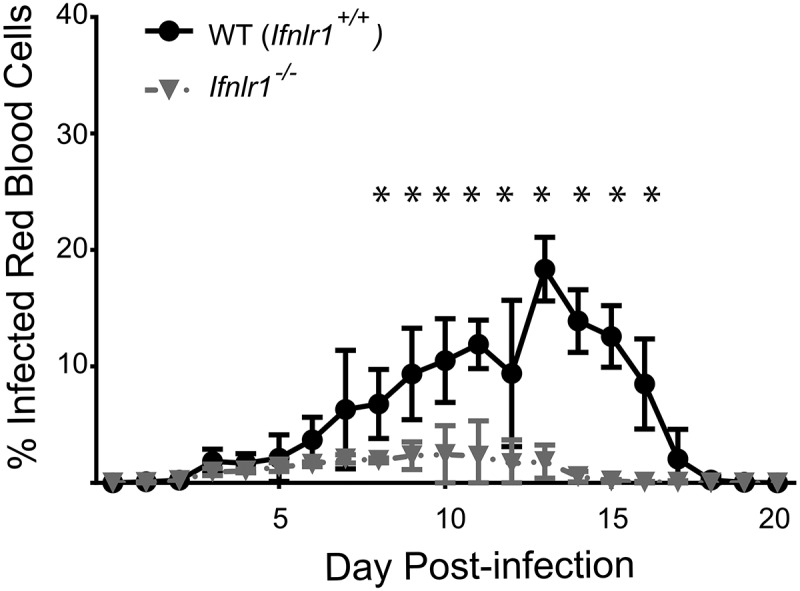

Genetic deletion of IFNλ receptor reduces parasite burden during initial blood-stage malaria infection

The biological role of IFNλ produced in response to Plasmodium infection is unknown. Whereas transcription of IFNλ mRNA increases substantially during acute stage blood-stage malaria infection [18], chronic malaria infection is associated with lower levels of plasma IFNλ [50]. We therefore sought to assess the biological role of IFNλ during blood-stage malaria infection in vivo. To test the effects of IFNλ on the outcome of blood-stage malaria, we infected mice with a global deficit in IFNλ signaling (Ifnlr1−/- mice) [51] with Plasmodium yoelli 17XNL, a non-lethal murine model of malaria. Given that both genetic background [52] and differences in microbiome [53] influence the course of murine malaria infection, all experiments were performed using sex-matched littermate controls born from Ifnlr1± by Ifnlr1± heterozygote pairings in order to minimize confounding variables. Using flow cytometry to measure the percentage of erythrocytes containing parasites (parasitemia) [24], we determined that parasitemia was strongly decreased in Ifnlr1−/- starting at day 10 post-infection when compared to littermate controls (Figure 1). Because control animals do not experience mortality or weight loss in this model [24], no differences were observed with respect to these clinical variables (data not shown). From these data, we concluded that genetic deletion of IFNλ signaling is associated with a substantial decrease in parasite burden during primary blood-stage malaria infection.

Figure 1.

Absence of interferon lambda leads to improved parasite control during blood-stage malaria infection.

Genetic deletion of the IFNλ receptor increases plasmablast formation and acute malaria-specific antibody production

The timing of reduction in parasite burden we observed (starting 10 days after infection) suggested a difference in the adaptive immune response. In the P. yoelii 17XNL model, T-and-B cell deficient mice (RAG−/- mice) first develop higher parasitemia compared to WT controls starting around days 8–10 post infection [54–56]; in contrast, control of parasite replication driven by the innate system appears earlier (approximately day 5) [54–56]. Antibodies are absolutely required for both parasite clearance and protection against reinfection in the P. yoelli 17XNL model [57]. We therefore hypothesized that differences in the humoral response driven by the lack of IFNλ signals could explain the observed difference in parasite control. To test this hypothesis, we measured antibody titers against a truncated carboxy terminus of the blood-stage antigen merozoite surface protein (MSP1) shown to be critical for infection by ELISA [24]. We decided to measure specifically the IgG2 c because the IgG2 c antibody appears early in plasma and can confer protection in murine models of blood-stage malaria [58–60]. Furthermore, we decided to measure acute antibody titers immediately prior to divergence of parasite burden between Ifnlr1−/- mice and littermate controls, given that variations in inoculum and ongoing inflammation can have dramatic effects on antibody titers during infection with malaria [24] and other pathogens [61–63]. Titers of anti-MSP1 IgG2 c and IgM were increased at day 7 post-infection in Ifnlr1−/- mice vs. littermate controls (Figure 2A). From these data, we concluded that Ifnlr1−/- mice had higher levels of antibody isotypes associated with protection when compared to littermate controls just prior to the divergence in parasite burden, demonstrating that antibody level did not reflect differences in antigen exposure.

Figure 2.

Absence of interferon lambda leads to increased antibody titers and increased plasmablast numbers.

Next, we determined whether there were differences in the B cell response that could potentially explain the difference in observed plasma antibody titers. The acute antibody response to infection is initiated with a subset of short-lived antibody secreting B cells called plasmablasts [15,64]. These cells are defined by surface expression of CD138+ (syndecan-1), and provide minimal contributions to the memory pool due to rapid cell death from apoptosis [8]. During a primary immune response, antibodies generated by plasmablasts are capable of directly neutralizing some infections [65]. As we had observed differences in plasma titers of antibodies in Ifnlr1−/- mice vs. littermate controls, we hypothesized that there would be differences in the early malaria-specific plasmablast response. To test this hypothesis, we utilized previously described B cell tetramers in combination with conventional flow cytometry [24]. Magnetic bead enrichment of B cells capable of binding a tetramer that incorporates the carboxy terminus of MSP1, enables the enumeration and characterization of the MSP1-specific B cells responding to infection without ex vivo manipulation [24,58]. We determined that the observed differences in antibody titers on day 7 post-infection were reflected in the number of MSP-specific plasmablasts, as Ifnlr1−/- mice had increased numbers and percentages of MSP-specific plasmablasts (Figure 2B). We also observed that the differences in plasma IgG2 c was also reflected in increased numbers and percentages of IgG negative/IgG2 c negative MSP-specific plasmablasts. From these data, we concluded IFNλ signaling suppresses the acute humoral response to blood-stage Plasmodium infection.

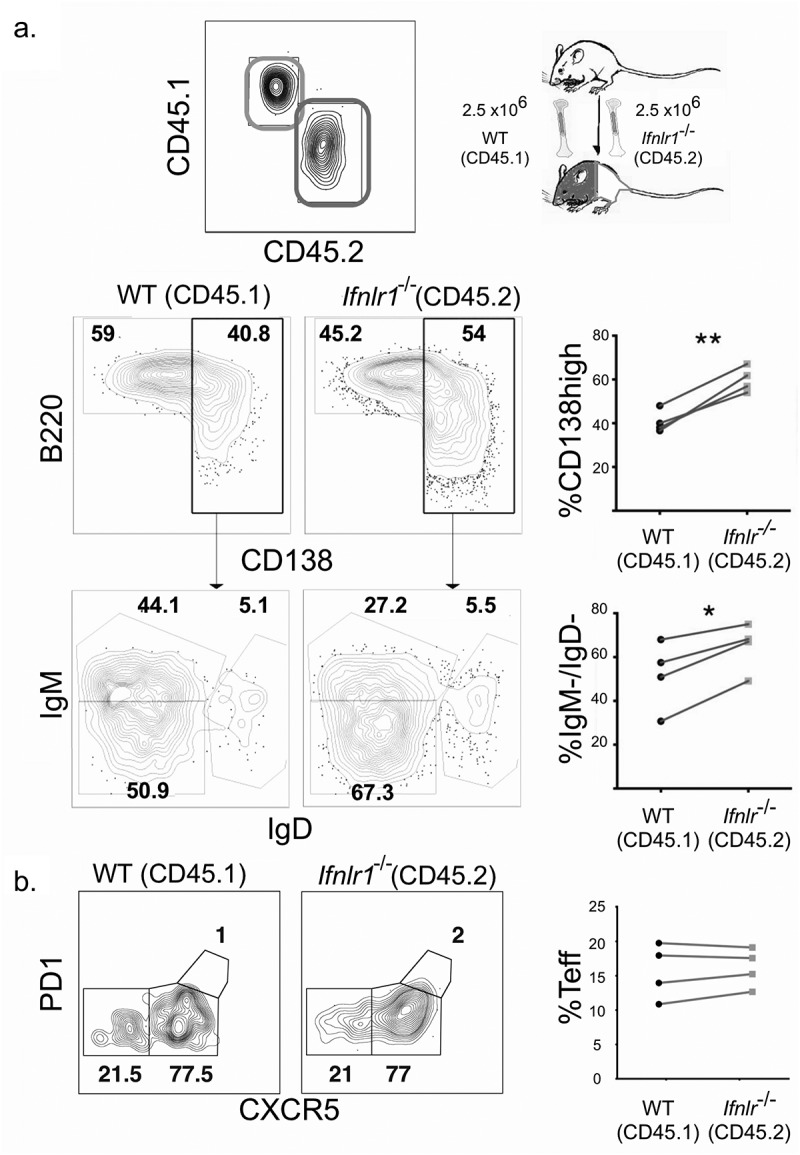

Genetic deletion of IFNλ receptor shifts CD4 + T cell differentiation toward an effector phenotype

Because CD4 + T cells are known to play a critical role in both the activation of B cell responses during a blood-stage Plasmodium infection [66,67], we hypothesized that IFNλ could also influence the CD4 + T cell response. IFNλ has been demonstrated to modulate CD4+ T cell differentiation in both Ifnlr1−/- mice [41] and humans given exogenous IFNλ[68]. To assess the role of IFNλ on the development and differentiation of CD4+ T cells, we used a transgenic P. yoelii 17XNL strain that stably expresses the LCMV epitope GP66+ [24]. This parasite allows for quantitation and phenotypic assessment of antigen-specific CD4+ T cell cells via flow cytometric analysis of CD4+ T cells that bind the fluorescently-conjugated GP66 I:Ab tetramer [69]. Although the total number of GP66+ CD4+ T cells were similar in Ifnlr1−/- mice and littermate controls on day 7 post-infection, there were substantial differences in the cellular phenotype of the antigen-specific CD4+ T cell response. Specifically, Ifnlr1−/- mice had a greater number and percentage of antigen-specific T effector (Teff) (defined as GP66+, CD44+, CXCR5low) [70] and fewer CD4+ T follicular helper (Tfh) cells (defined as GP66+, CD44+, CXCR5high) when compared to littermate controls (Figure 3). From these data, we concluded that the absence of IFNλ signals skews the CD4 + T cell response toward an effector response during the initial phase of the immune response to blood-stage Plasmodium infection prior to divergence in parasite burden.

Figure 3.

Absence of interferon lambda leads to increased CD4+ T effector cells.

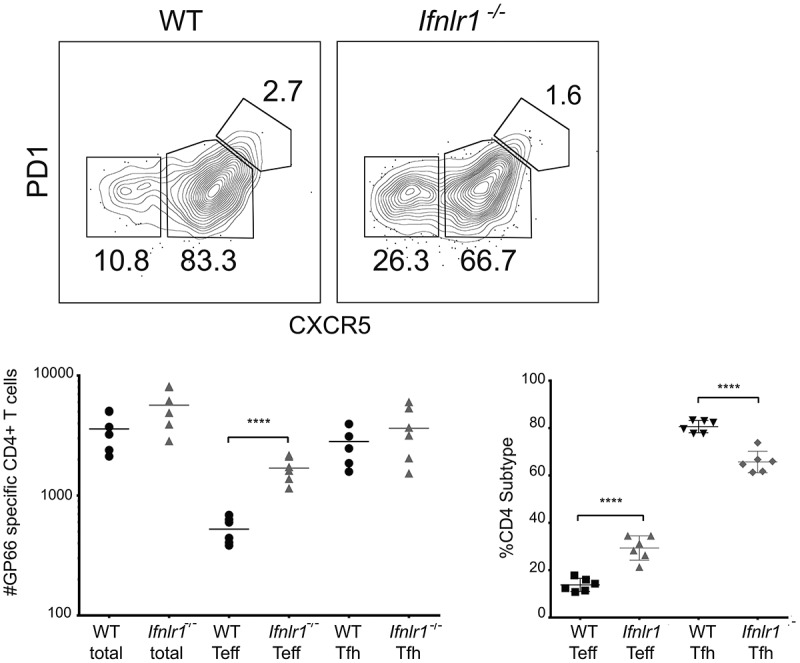

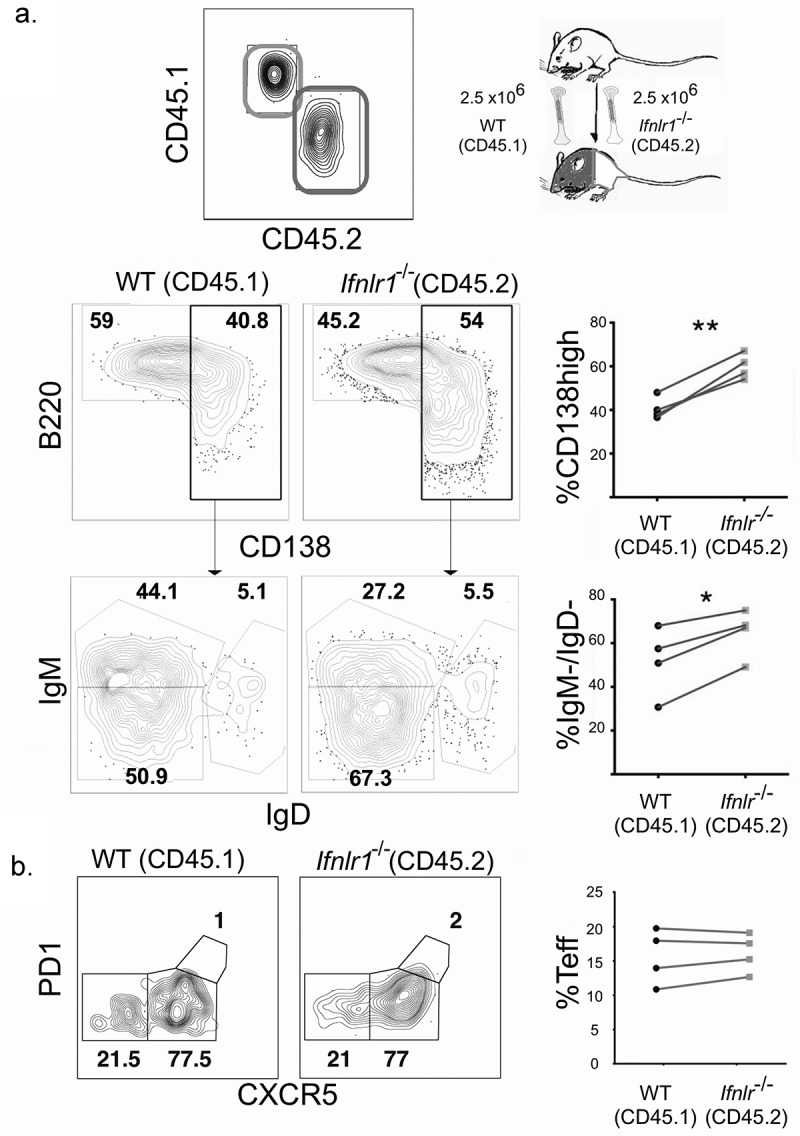

Absence of cell-intrinsic IFNλ signals favors plasmablast formation but does not affect CD4 + T cell differentiation

We had observed differences in the cellular differentiation of both CD4 + T cells and B cells, so we decided to investigate which effects, if any, were a result of direct IFNλ signals. Both direct and indirect cellular effects on lymphocytes could be plausible. IFNλ has been shown indirectly mediate the differences in CD4+ T cell response [41,71]. B cells are directly responsive to IFNλ in vitro [72]. Additionally, in vivo interactions between CD4+ T cells and B cells can also affect the differentiation of each cell type, suggesting that either B cells (or CD4+ T cells) could be driving the effector phenotype [15].

We hypothesized that the effects of IFNλ for B cell differentiation were due to B cell intrinsic signals because IFNλ suppresses B cell proliferation and antibody secretion in vitro in PBMCs [40]. To test this hypothesis, we utilized a congenically-labeled mixed bone marrow chimera system in which cell intrinsic effects can be examined in the same mice. Lethally irradiated CD45.1/CD45.2 mice were reconstituted with bone marrow from both WT CD45.1 and Ifnlr1−/- CD45.2 mice. The resulting experimental system allowins for testing whether the effects of IFNλ are intrinsic to any hematopoietic cell of interest. Additionally, the system normalizes the cytokine environment, antigen load, host background, and cellular interactions. After allowing the mixed bone marrow chimera mice to reconstitute, we infected mice with non-lethal transgenic P. yoelii 17XNL GP66 as before. We assessed the antigen-specific CD4+ T cell and B cell responses on day seven post-infection. We observed that the Ifnlr1−/- (CD45.2) B cells formed isotype-switched MSP1-specific plasmablasts at a higher frequency than WT (CD45.1) cells (Figure 4A). When plasmablasts were gated out from the total B cell population, no differences were observed in the formation of isotype-switched memory B cells or germinal center precursors (data not shown). We observed no effects on CD4+ T cell differentiation. From these data, we concluded that IFNλ signals acting directly upon B cells were responsible for the difference in plasmablast formation in response to blood-stage malaria infection. Consistent with other infectious models [41,71], we observed no differences in the antigen-specific CD4 + T cell response between WT (CD45.1) and Ifnlr1−/- (CD45.2) cells (Figure 4B), demonstrating the shift toward an effector response we observed in the CD4 + T cells of Ifnlr1−/- mice was due to indirect (cell-extrinsic) effects.

Figure 4.

Interferon lambda signals suppress plasmablast formation in a B cell-intrinsic fashion.

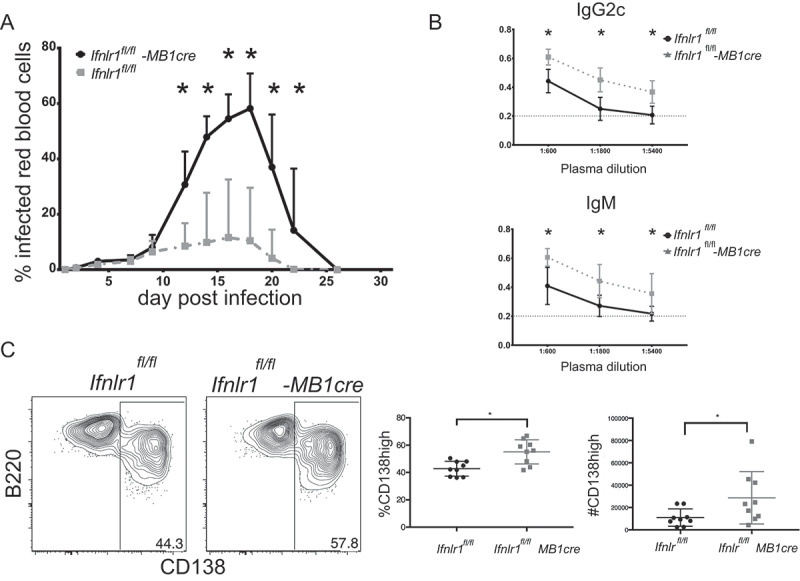

IFNλ−mediated control of parasitemia and plasmablasts is due to B cell-intrinsic signals

Since we observed that absence of B cell-intrinsic IFNλ signaling increased plasmablast formation, we hypothesized these effects were also responsible for mediating the improved control of parasite burden in Ifnlr1−/- mice. However, CD4+ T cells have also been demonstrated to directly mediate protection against blood-stage Plasmodium [73]. To test whether the absence of IFNλ signals on B cells was directly responsible for improved parasite control, we generated a mouse that conditionally lacked IFNL1 R in the B cell compartment. Transgenic mice that express Cre under the B cell – specific MB1 promoter were crossed with mice with a floxed IFNλ receptor allele (MB1-cre x Ifnlrfl/fl) [74,75]. The resulting offspring therefore lack expression of the IFNλ receptor in the B cell compartment [75]. To test whether B cell-restricted IFNλ signaling recapitulated the results we see in the chimeric setting and were responsible for parasite control, we infected MB1-cre Ifnlr1fl/fl mice with P. yoelli 17XL GP66 and measured daily parasitemia. Similar to our observations in mice with a global deficit in the IFNλ receptor, we observed improved control of parasitemia starting at day 10 in MB1-cre Ifnlr1fl/fl mice when compared to littermate controls that lack the cre allele (Ifnlr1fl/fl) (Figure 5A). When we assessed the MSP1-specific B cell response, we again determined that there were increased plasmablasts (Figure 5B) in cre-sufficient mice as compared to littermates who lack the cre-allele. Similar to Ifnlr1-/- mice, MB1-cre fnlr1fl/fl mice had increased titers when compared to littermate controls. As expected, we observed no effects on the CD4 + T cell response (data not shown). These data indicate that IFNλ signals on B cells control parasite burden; moreover, consistent with the data from mixed bone-marrow chimeras (see Figure 4), the observed increased formation of plasmablasts was due to B-cell intrinsic IFNλ signals. We would note, however, that the parasite burden in the control Ifnlr1fl/fl mice was higher (~50% peak) than the burden in the original C57BL6/J-background control mice (Ifnlr1+/+) at peak (~20%), suggesting potential differences in experimental conditions or host genetic background.

Figure 5.

Improved control of blood-stage infection with absence of Interferon lambda-specific B cells.

Discussion

Using a murine model of blood-stage malaria infection, we have determined that the absence of IFNλ improves early parasite control via direct effects on B cells. Our findings that IFNλ signals impede parasite clearance during non-lethal blood-stage infection with P. yoelii are reminiscent of the role of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, as mice with disrupted IL-10 signaling have reduced parasite burdens during non-lethal blood-stage malaria infection [76]. Our findings that removal of IFNλ improves acute parasite control are consistent with its physiological role in other systems, as IFNλ has been shown to directly suppress neutrophil-mediated inflammation in models of drug induced colitis [77] and thrombosis [78]. The inferred “suppressive” effect during non-lethal blood-stage malaria (where removal improves the acute host response) is interesting given that the functional receptor for IFN-λ shares a common subunit with the IL-10 receptor [48] and the IL-10 family has been described as the prototypical anti-inflammatory cytokine [79].

Our findings that the in vivo effects of IFNλ signals repress plasmablast formation add to the understanding of the biological role of this cytokine during the humoral response to systemic pathogens. Previous in vitro investigations have reached differing conclusions regarding the biological effects of IFNλ signaling for B cells. Exogenous administration of IFNλ reduced both proliferation and activation of B cells during stimulation with influenza antigens [40] whereas in vitro administration of IFNλ in conjunction with TLR7 agonists enhanced Ab secretion and proliferation [39]. The discrepancies between whether IFNλ stimulates or suppresses the B cell effector functions are similar to the discrepancies of the biological role of both Type I and Type II IFN. We suspect that, like other IFNs, the in vivo role of IFNλ depends on the immune context. In general, our observation that IFNλ-deficient B cells form plasmablasts at a higher rate during blood-stage malaria infection are more in keeping with an “suppressive” role of IFNλ. While we did not formally assess proliferation, plasmablasts undergo rapid proliferation and are strongly associated with inflammatory disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus [80]. An alternative, non-exclusive explanation could be that IFNλ induces plasmablast-specific cell death as was recently demonstrated in intestinal cells [81]. The exact mechanism by which IFNλ signals reduce the number of plasmablasts should remain an active area of investigation.

IFNλ signals appears to influence the CD4+ T cell response during blood-stage malaria in an indirect fashion. There is no consensus as to whether T cells can respond to IFNλ directly, as some groups have reported direct effects of exogenous IFNλ for CD4 + T cells (typically on ex vivo human T cells) [82,83] whereas other groups using both human or murine systems have not found direct effects [41,71,84,85]. Our mixed bone marrow chimera experiments demonstrate that the shift toward an effector response in Ifnlr1−/- mice during blood-stage infection is not mediated by direct IFNλ signals on CD4 + T cells, in keeping with observations using similar approaches [41,71]. Furthermore, our experiments in MB1-cre Ifnlr1fl/fl mice demonstrate that the CD4+ T cell effector bias we observed is not mediated by IFNλ signals on B cell. The cell type responsible for IFNλ-mediated alterations in the CD4+ T cell response during blood-stage malaria infection should be a focus of further investigations. Because conflicting evidence exists regarding the role of CD8 + T cells during experimental acute blood stage malaria [86–91], we did not investigate the role of the CD8 + T cell population in our model. As other groups have reported increased numbers of CD8+ T cells in Ifnlr1−/- mice during the acute response to LCMV, [41], there could be a potential role for alterations in the CD8+ T cell population in Ifnlr1−/- mice. Potential effects of IFNλ on the CD8+ T cell population should remain an active area of investigation for future studies. Similar to CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells do not respond directly to IFNλ signals, suggesting that any potential role would be indirect [41,71].

Our findings also add to the body of literature suggesting that the biological role of IFNλ is distinct from other IFNs. Forero et al. recently demonstrated that Type III IFNs preferentially elicit genetic programs associated with tissue repair when compared to Type I IFNs [92] Additionally, Ifnlr1−/- mice had different alterations in the immune response during intransal vaccination with attenuated influenza compared when compared Type I IFN receptor-deficient (IFNAR1−/-) mice [93,94].

Our findings demonstrating that IFNλ suppresses the acute B cell response to blood-stage malaria suggest that the biological role of IFNλ extends beyond the barrier interface. Our findings have potential implications for antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases where plasmablasts are thought to contribute to disease pathogenesis such as SLE or rheumatoid arthritis. Additionally, our findings suggest that IFNλ can modulate the acute humoral response. The effects of B-cell intrinsic IFNλ for the memory response should be an active area of future investigation.

Materials and methods

Study approval

All experiments involving animals were performed in accordance with the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Mice

Male 6-to-8 week old C57BL/6 J, SJL 45.1, and MB1cre/cre mice were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories and maintained under specific-pathogen free conditions per the University of Washington Guidelines. Ifnlr1−/- and Ifnlr1fl/fl mice were provided as a kind gift by Michael Gale Jr. Ifnlr1−/- mice were bred from heterozygotes pairings with genotyping as previously described [41]. All experiments were performed in accordance with University of Washington Institutional Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Mixed bone marrow chimeras

Mixed bone marrow chimeras were generated as previously described [70]. Bone marrow cells were depleted of T and NK cells and C57BL/6 J SJL.1 (CD45.1) and Ifnlr1−/- cells were counted and mixed in equal proportions with 2.5 million cells of each type. Recipient mice were lethally irradiated with 1000 rads, and bone marrow was reconstituted via retroorbital injection of marrow cells. Mice were allowed to reconstitute at least eight weeks prior to infection. Representative flow cytometry gating scheme for identification of congenically marked, antigen-specific B cells on day seven post infection. Plots representative of four mice from two separate experiments are shown. Statistical analysis was performed using the paired Student’s t test.

Experimental murine malaria infection

P. yoelii 17XNL GP66 and P. yoelii 17XL were maintained by passage through donor mice with no more than 3 inoculations prior to recirculation through mosquitoes. Infections were induced by intraperitoneal injection of 106 infected erythrocytes from donor mice with parasitemia of 1–5%. The transgenic parasite stably expressing the GP66 epitope was generated as previously described [24].

Tetramer production

Biotinylated I-Ab LCMV GP 66–77 DIYKGVYQFKSV monomers were obtained from the NIH tetramer core and tetramerized with SA-APC as previously described [95]. For antigen-specific B cell experiments, a 14 kDA truncated carboxy terminus of PyMSP1 was cloned, purified, biotinylated, and tetramerized with streptavidin-PE (Prozyme) [12,96]. Decoy reagent to detect B cells specific for tetramer components was constructed as previously described [58,97].

Cell enrichment, flow cytometry, and antibodies

Single cell suspensions of spleen and cervical, mediastinal, axillary, brachial, pancreatic, renal, mesenteric, inguinal and lumbar lymph nodes (SLO) were prepared by mashing through Nitex mesh (amazon.com) and resuspending in 2% FBS and Fc Block (2.4G2). Cells were then stained with decoy reagent at a concentration of 10 nM at room temperature for 15 minutes, followed by MSP1-PE tetramer for 30 minutes on ice, washed, and then stained with anti-PE beads prior to a magnetic enrichment. All bound cells then were stained with antibodies shown in Supplemental Table 1, detected on an LSRII Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences), and analyzed using Flowjo 9.94 (Treestar).

ELISA-based malaria-specific antibody assay

96 well ELISPOT plates (Millipore) were coated overnight at 4 C with MSP1+ protein at 1 µg/mL. Plates were then blocked with 5% dehydrated milk prior to sample incubation. Plates were incubated with serially diluted serum. Bound antibodies were detected using either IgM Biotin (Clone II/41) or IgG2 c Biotin (Clone 5.7) followed by Streptavidin-HRP (BD). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an iMark Microplate Reader (Bio-Rad).

Statistics

When data were parametric, unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t tests were applied to determine the statistical significance of the difference between groups with Prism 6 (Graphpad) software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Gale for providing kindly Ifnlr1−/- and the Ifnlr1fl/fl mice. We thank Brian Hondowicz for experimental advice and technical assistance. This work was supported by grants to WOH (NIH Grant T32 AI007044-39) and MP (NIH Grant RO1 AI-118803).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [AI-118803]; National Institutes of Health (US) [AI007044-39].

Author contributions

WOH, WCL, and MP designed experiments and analyzed data. WOH performed experiments. WOH, WCL, and MP wrote the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Murray CJL, Ortblad KF, Guinovart C, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. [Internet]. 2014;384(9947):1005–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Weiss GE, Traore B, Kayentao K, et al. The Plasmodium falciparum-specific human memory B cell compartment expands gradually with repeated malaria infections. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tran TM, Li S, Doumbo S, et al. An intensive longitudinal cohort study of Malian children and adults reveals no evidence of acquired immunity to Plasmodium falciparum infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Portugal S, Pierce SK, Crompton PD.. Young lives lost as B cells falter: what we are learning about antibody responses in malaria. J Immunol. 2013;190:3039–3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Raj DK, Nixon CP, Nixon CE, et al. Antibodies to PfSEA-1 block parasite egress from RBCs and protect against malaria infection. Science. 2014;344(6186):871–877. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kinyanjui SM, Conway DJ, Lanar DE, et al. IgG antibody responses to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite antigens in Kenyan children have a short half-life. Malar J. 2007;6:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kinyanjui SM, Bull P, Newbold CI, et al. Kinetics of antibody responses to Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocyte variant surface antigens. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:667–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sze DM, Toellner KM, García de Vinuesa C, et al. Intrinsic constraint on plasmablast growth and extrinsic limits of plasma cell survival. J Exp Med. 2000;192:813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Suan D, Sundling C, Brink R. Plasma cell and memory B cell differentiation from the germinal center. Curr Opin Immunol. 2017;45:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pape KA, Taylor JJ, Maul RW, et al. Different B cell populations mediate early and late memory during an endogenous immune response. Science. 2011;331:1203–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Corcoran LM, Tarlinton DM. Regulation of germinal center responses, memory B cells and plasma cell formation-an update. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;39:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Taylor JJ, Pape KA, Jenkins MK. A germinal center-independent pathway generates unswitched memory B cells early in the primary response. J Exp Med. 2012;209:597–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Moffett HF, Harms CK, Fitzpatrick KS, et al. B cells engineered to express pathogen-specific antibodies protect against infection. Sci Immunol. 2019;4:eaax0644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Taylor JJ, Pape KA, Steach HR, et al. Humoral immunity. Apoptosis and antigen affinity limit effector cell differentiation of a single naïve B cell. Science. 2015;347:784–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Harms Pritchard G, Pepper M. Memory B cell heterogeneity: remembrance of things past. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;103:269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yoon H-K, Shim Y-S, Kim P-H, et al. The TLR7 agonist imiquimod selectively inhibits IL-4-induced IgE production by suppressing IgG1/IgE class switching and germline ε transcription through the induction of BCL6 expression in B cells. Cell Immunol. 2019;338:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Syedbasha M, Egli A. Interferon lambda: modulating immunity in infectious diseases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tran TM, Jones MB, Ongoiba A, et al. Transcriptomic evidence for modulation of host inflammatory responses during febrile Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hillyer P, Mane VP, Schramm LM, et al. Expression profiles of human interferon-alpha and interferon-lambda subtypes are ligand- and cell-dependent. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90:774–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shiow LR, Rosen DB, Brdicková N, et al. CD69 acts downstream of interferon-alpha/beta to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature. 2006;440:540–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gibb DR, Liu J, Santhanakrishnan M, et al. B cells require Type 1 interferon to produce alloantibodies to transfused KEL-expressing red blood cells in mice. Transfusion. 2017;57:2595–2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Denton AE, Innocentin S, Carr EJ, et al. Type I interferon induces CXCL13 to support ectopic germinal center formation. J Exp Med. [Internet]. 2019;216(3):621–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Daugan M, Murira A, Mindt BC, et al. Type I interferon impairs specific antibody responses early during establishment of LCMV infection. Front Immunol. 2016;7:564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hahn WO, Butler NS, Lindner SE, et al. cGAS-mediated control of blood-stage malaria promotes Plasmodium-specific germinal center responses. JCI Insight. 2018;3. [Internet]. DOI: 10.1172/jci.insight.94142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vigário AM, Belnoue E, Grüner AC, et al. Recombinant human IFN-alpha inhibits cerebral malaria and reduces parasite burden in mice. J Immunol. 2007;178:6416–6425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Morrell CN, Srivastava K, Swaim A, et al. Beta interferon suppresses the development of experimental cerebral malaria. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1750–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wu J, Tian L, Yu X, et al. Strain-specific innate immune signaling pathways determine malaria parasitemia dynamics and host mortality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E511–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zander RA, Guthmiller JJ, Graham AC, et al. Type I interferons induce T regulatory 1 responses and restrict humoral immunity during experimental malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sebina I, James KR, Soon MSF, et al. IFNAR1-signalling obstructs ICOS-mediated humoral immunity during non-lethal blood-stage plasmodium infection. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Obeng-Adjei N, Portugal S, Holla P, et al. Malaria-induced interferon-γ drives the expansion of Tbethi atypical memory B cells. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ryg-Cornejo V, Ioannidis LJ, Ly A, et al. Severe malaria infections impair germinal center responses by inhibiting T follicular helper cell differentiation. Cell Rep. [Internet]. 2015. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Guthmiller JJ, Graham AC, Zander RA, et al. Cutting Edge: IL-10 Is essential for the generation of germinal center B cell responses and anti-plasmodium humoral immunity. J Immunol. 2017;198:617–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Domeier PP, Chodisetti SB, Soni C, et al. IFN-γ receptor and STAT1 signaling in B cells are central to spontaneous germinal center formation and autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2016;213:715–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jackson SW, Jacobs HM, Arkatkar T, et al. B cell IFN-γ receptor signaling promotes autoimmune germinal centers via cell-intrinsic induction of BCL-6. J Exp Med. 2016;213:733–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rubtsova K, Rubtsov AV, Halemano K, et al. T cell production of IFNγ in Response to TLR7/IL-12 stimulates optimal B cell responses to viruses. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lazear HM, Nice TJ, Diamond MS. Interferon-λ: immune functions at barrier surfaces and beyond. Immunity. 2015;43:15–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nice TJ, Baldridge MT, McCune BT, et al. Interferon-λ cures persistent murine norovirus infection in the absence of adaptive immunity. Science. 2015;347:269–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Klinkhammer J, Schnepf D, Ye L, et al. IFN-λ prevents influenza virus spread from the upper airways to the lungs and limits virus transmission. Elife. 2018;7. [Internet]. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.33354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].de Groen RA, Groothuismink ZMA, Liu B-S BA. IFN-λ is able to augment TLR-mediated activation and subsequent function of primary human B cells. J Leukoc Biol. [Internet]. 2015. DOI: 10.1189/jlb.3A0215-041RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Egli A, Santer DM, O’Shea D, et al. IL-28B is a key regulator of B- and T-cell vaccine responses against influenza. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Misumi I, Whitmire JK. IFN-λ exerts opposing effects on T cell responses depending on the chronicity of the virus infection. J Immunol. 2014;192:3596–3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1105–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chinnaswamy S. Gene-disease association with human IFNL locus polymorphisms extends beyond hepatitis C virus infections. Genes Immun. 2016;17:265–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].O’Brien TR, Pfeiffer RM, Paquin A, et al. Comparison of functional variants in IFNL4 and IFNL3 for association with HCV clearance. J Hepatol. 2015;63:1103–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Egli A, Levin A, Santer DM, et al. Immunomodulatory Function of Interleukin 28B during primary infection with cytomegalovirus. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:717–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kotenko SV, Gallagher G, Baurin VV, et al. IFN-lambdas mediate antiviral protection through a distinct class II cytokine receptor complex. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Peterson ST, Kennedy EA, Brigleb PH, et al. Disruption of type III interferon genes Ifnl2 and Ifnl3 recapitulates loss of the type III IFN receptor in the mucosal antiviral response. J Virol. [Internet]. 2019. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.01073-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Djontu JC, Siewe Siewe S, Mpeke Edene YD, et al. Impact of placental Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection on the Cameroonian maternal and neonate’s plasma levels of some cytokines known to regulate T cells differentiation and function. Malar J. 2016;15(1):561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lazear HM, Daniels BP, Pinto AK, et al. Interferon-λ restricts West Nile virus neuroinvasion by tightening the blood-brain barrier. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:284ra59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Geurts N, Martens E, Verhenne S, et al. Insufficiently defined genetic background confounds phenotypes in transgenic studies as exemplified by malaria infection in Tlr9 knockout mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yilmaz B, Portugal S, Tran TM, et al. Gut microbiota elicits a protective immune response against malaria transmission. Cell. 2014;159:1277–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Choudhury HR, Sheikh NA, Bancroft GJ, et al. Early nonspecific immune responses and immunity to blood-stage nonlethal Plasmodium yoelii malaria. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6127–6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Couper KN, Blount DG, Hafalla JCR, et al. Macrophage-mediated but gamma interferon-independent innate immune responses control the primary wave of Plasmodium yoelii parasitemia. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5806–5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Vigário AM, Belnoue E, Cumano A, et al. Inhibition of Plasmodium yoelii blood-stage malaria by interferon alpha through the inhibition of the production of its target cell, the reticulocyte. Blood. 2001;97:3966–3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Grun JL, Weidanz WP. Antibody-independent immunity to reinfection malaria in B-cell-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 1983;41:1197–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Krishnamurty AT, Thouvenel CD, Portugal S, et al. Somatically hypermutated plasmodium-specific IgM(+) memory B cells are rapid, plastic, early responders upon malaria rechallenge. Immunity. 2016;45:402–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].White WI, Evans CB, Taylor DW. Antimalarial antibodies of the immunoglobulin G2a isotype modulate parasitemias in mice infected with Plasmodium yoelii. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3547–3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Borges da Silva H, Machado de Salles É, Lima-Mauro EF, et al. CD28 deficiency leads to accumulation of germinal-center independent IgM+ experienced B cells and to production of protective IgM during experimental malaria. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0202522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Taylor-Robinson T-R, Phillips P. Infective dose modulates the balance between Th1- and Th2-regulated immune responses during blood-stage malaria infection. Scand J Immunol. 1998;48(5):527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Galani IE, Triantafyllia V, Eleminiadou -E-E, et al. Interferon-λ mediates non-redundant front-line antiviral protection against influenza virus infection without compromising host fitness. Immunity. 2017;46:875–90.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Redeker A, Welten SPM, Arens R. Viral inoculum dose impacts memory T-cell inflation. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:1046–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ellebedy AH, Jackson KJL, Kissick HT, et al. Defining antigen-specific plasmablast and memory B cell subsets in human blood after viral infection or vaccination. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1226–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kalinke U, Bucher EM, Ernst B, et al. The role of somatic mutation in the generation of the protective humoral immune response against vesicular stomatitis virus. Immunity. 1996;5:639–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Borges da Silva H, Fonseca R, Cassado ADA, et al. In vivo approaches reveal a key role for DCs in CD4+ T cell activation and parasite clearance during the acute phase of experimental blood-stage malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Roberts DW, Rank RG, Weidanz WP, et al. Prevention of recrudescent malaria in nude mice by thymic grafting or by treatment with hyperimmune serum. Infect Immun. 1977;16:821–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Phillips S, Mistry S, Riva A, et al. Peg-interferon lambda treatment induces robust innate and adaptive immunity in chronic hepatitis B patients. Front Immunol. 2017;8:621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].MKL M, McKee A, Crawford F, et al. CD4 memory T cells divide poorly in response to antigen because of their cytokine profile. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14521–14526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Pepper M, Pagán AJ, Igyártó BZ, et al. Opposing signals from the Bcl6 transcription factor and the interleukin-2 receptor generate T helper 1 central and effector memory cells. Immunity. 2011;35:583–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Hemann EA, Green R, Turnbull JB, et al. Interferon-λ modulates dendritic cells to facilitate T cell immunity during infection with influenza A virus. Nat Immunol. [Internet]. 2019;20(8):1035–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Kelly A, Robinson MW, Roche G, et al. Immune cell profiling of IFN-λ response shows pDCs express highest level of IFN-λR1 and are directly responsive via the JAK-STAT pathway. J Interferon Cytokine Res. [Internet]. 2016;36(12):671–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Amante FH, Good MF. Prolonged Th1-like response generated by a Plasmodium yoelii-specific T cell clone allows complete clearance of infection in reconstituted mice. Parasite Immunol. 1997;19:111–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Baldridge MT, Lee S, Brown JJ, et al. Expression of Ifnlr1 on intestinal epithelial cells is critical to the antiviral effects of IFN-lambda against norovirus and reovirus. J Virol. [Internet]. 2017. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.02079-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Hobeika E, Thiemann S, Storch B, et al. Testing gene function early in the B cell lineage in mb1-cre mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13789–13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Couper KN, Blount DG, Wilson MS, et al. IL-10 from CD4CD25Foxp3CD127 adaptive regulatory T cells modulates parasite clearance and pathology during malaria infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Broggi A, Tan Y, Granucci F, et al. IFN-λ suppresses intestinal inflammation by non-translational regulation of neutrophil function. Nat Immunol. [Internet]. 2017;18(10):1084–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Chrysanthopoulou A, Kambas K, Stakos D, et al. Interferon lambda1/IL-29 and inorganic polyphosphate are novel regulators of neutrophil-driven thromboinflammation. J Pathol. [Internet]. 2017;243(1):111–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Ouyang W, Rutz S, Crellin NK, et al. Regulation and functions of the IL-10 family of cytokines in inflammation and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29(1):71–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Banchereau R, Hong S, Cantarel B, et al. Personalized immunomonitoring uncovers molecular networks that stratify lupus patients. Cell. 2016;165:551–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Günther C, Ruder B, Stolzer I, et al. Interferon lambda promotes paneth cell death via STAT1 signaling in mice and is increased in inflamed ileal tissues of patients with crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. [Internet]. 2019;157(5):1310–1322.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Jordan WJ, Eskdale J, Srinivas S, et al. Human interferon lambda-1 (IFN-λ1/IL-29) modulates the Th1/Th2 response. Genes Immun. 2007;8(3):254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Dai J, Megjugorac NJ, Gallagher GE, et al. IFN-lambda1 (IL-29) inhibits GATA3 expression and suppresses Th2 responses in human naive and memory T cells. Blood. 2009;113:5829–5838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Nordström I, Eriksson K. HHV-6B induces IFN-lambda1 responses in cord plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR9. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Arasteh J, Ebtekar M, Pourpak Z, et al. The effect of IL-28A on human cord blood CD4+ T cells. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2010;32:339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].van der Heyde HC, DD M, DC R, et al. Resolution of blood-stage malarial infections in CD8+ cell-deficient beta 2-m0/0 mice. J Immunol. 1993;151:3187–3191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Weidanz WP, Melancon-Kaplan J, Cavacini LA. Cell-mediated immunity to the asexual blood stages of malarial parasites: animal models. Immunol Lett. 1990;25:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Vinetz JM, Kumar S, Good MF, et al. Adoptive transfer of CD8+ T cells from immune animals does not transfer immunity to blood stage plasmodium yoelii malaria. J Immunol. 1990;144:1069–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Imai T, Ishida H, Suzue K, et al. Cytotoxic activities of CD8+ T cells collaborate with macrophages to protect against blood-stage murine malaria. Elife. 2015;4. [Internet]. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.04232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Imai T, Suzue K, Ngo-Thanh H, et al. Fluctuations of spleen cytokine and blood lactate, importance of cellular immunity in host defense against blood stage malaria plasmodium yoelii. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Horne-Debets JM, Karunarathne DS, Faleiro RJ, et al. Mice lacking Programmed cell death-1 show a role for CD8(+) T cells in long-term immunity against blood-stage malaria. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Forero A, Ozarkar S, Li H, et al. Differential activation of the transcription factor IRF1 underlies the distinct immune responses elicited by Type I and Type III interferons. Immunity. [Internet]. 2019;51(3):451–464.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Ye L, Schnepf D, Becker J, et al. Interferon-λ enhances adaptive mucosal immunity by boosting release of thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Ye L, Ohnemus A, Ong LC, et al. Type I and type III interferons differ in their adjuvant activities for influenza vaccines. J Virol. [Internet]. 2019;93. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.01262-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Moon JJ, Chu HH, Hataye J, et al. Tracking epitope-specific T cells. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:565–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Keitany GJ, Kim KS, Krishnamurty AT, et al. Blood stage malaria disrupts humoral immunity to the pre-erythrocytic stage circumsporozoite P rotein. Cell Rep. 2016;17:3193–3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Taylor JJ, Martinez RJ, Titcombe PJ, et al. Deletion and anergy of polyclonal B cells specific for ubiquitous membrane-bound self-antigen. J Exp Med. 2012;209:2065–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.