Abstract

Aberrant fetal growth remains a leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality and is associated with a risk of developing non-communicable diseases later in life. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis combining human and animal studies to assess whether prenatal amino acid (AA) supplementation could be a promising approach to promote healthy fetal growth. PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane libraries were searched to identify studies orally supplementing the following AA groups during gestation: (1) arginine family, (2) branched chain (BCAA), and (3) methyl donors. The primary outcome was fetal/birth weight. Twenty-two human and 89 animal studies were included in the systematic review. The arginine family and, especially, arginine itself were studied the most. Our meta-analysis showed beneficial effects of arginine and (N-Carbamyl) glutamate (NCG) but not aspartic acid and citrulline on fetal/birth weight. However, no effects were reported when an isonitrogenous control diet was included. BCAA and methyl donor supplementation did not affect fetal/birth weight. Arginine family supplementation, in particular arginine and NCG, improves fetal growth in complicated pregnancies. BCAA and methyl donor supplementation do not seem to be as promising in targeting fetal growth. Well-controlled research in complicated pregnancies is needed before ruling out AA supplements or preferring arginine above other AAs.

Keywords: amino acids, arginine, birth weight, branched chain amino acid, fetal growth restriction, meta-analysis, methyl donor, pregnancy

1. Introduction

Divergence in fetal growth—both under- and overgrowth—remains a leading cause of perinatal mortality and morbidity [1,2]. Fetal growth divergence has been associated with the development of non-communicable diseases later in life, including cardio-metabolic disorders [3,4,5,6,7,8].

Normal fetal growth requires adequate amino acid (AA) supply during all trimesters, which depends on the placental capacity to transfer AAs from the maternal to fetal side [9]. Several factors influence this transfer capacity, such as maternal plasma AA concentrations, utero-placental blood flow, and placental surface area [10].

A disruption in fetal supply of AAs might contribute to fetal under- or overgrowth. The major cause of fetal growth restriction (FGR) is placental insufficiency, which often co-occurs with hypertensive disorder during pregnancy. Decreased utero-placental blood flow could result in reduced placental transfer of AAs and consequently FGR. Lower circulating levels of AAs of the arginine family and branched chain AAs (BCAA) and reduced expression or activity of placental AA transporters are indeed observed in FGR pregnancies [11,12,13,14,15,16]. On the other hand, fetal overgrowth is observed in gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in which increased circulating AA levels interact with insulin sensitivity, and increased maternal glucose stimulates nutrient transport over the placenta [17,18,19,20].

Oral supplementation of AAs during pregnancy could be an effective—and relatively safe—therapeutic or prophylactic solution to improving perinatal and long-term health. The arginine family, BCAAs, and methyl donors form three interesting supplementation groups by virtue of their influence on fetal growth. The arginine family plays a key role in placental growth and development through nitric oxide (NO) and polyamine syntheses and through the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway [9,12,21,22,23]. Arginine also stimulates creatine production and skeletal muscle protein synthesis [24]. BCAAs possess strong insulinogenic and anabolic effects, and these essential AAs mediate lean body mass growth through mTOR [12,25]. Methyl donors stimulate fatty acid catabolism [26]. Their ability to donate methyl groups facilitates genetic and epigenetic regulation of placental and fetal programming [27]. The effect of AA supplementation during pregnancy has been studied in both humans and animals, but a clear overview of the resulting effects is currently lacking.

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluates the effect of oral supplementation of the three AA groups on fetal growth in complicated and normal-growth pregnancies. Considering the altered circulating levels of the specific AAs, the activity of placental transporters, and the hypothesized mechanism of action, we speculate that AAs from the arginine family or BCAAs normalize fetal undergrowth, while methyl donors normalize fetal overgrowth. By including different AAs in animal and human studies in one meta-analysis, we aim to identify the most effective AA (group) and other modifiable factors (e.g., dose). This will contribute towards future study designs aimed at developing an AA-based supplementation strategy to prevent fetal growth divergence and its sequels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

This systematic review was conducted according to a prespecified protocol registered at PROSPERO for animal studies (CRD42018098779; based on [28]) and human studies (CRD42018095995) (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO). The sparse amendments to the review protocol that were made post hoc are reported in the Appendix. This review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [29]. No language or publication date restrictions were applied.

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

On 25th July 2018, we searched Pubmed, Embase (via OVID), and the Cochrane Library database to identify animal and human studies reporting on prenatal supplementation of 14 AAs falling within the following three groups: (1) arginine family: arginine, citrulline, glutamate, glutamine, asparagine, aspartate, proline, and ornithine; (2) BCAA: leucine, iso-leucine, and valine; and (3) methyl donors: cysteine, methionine, and the AA derivate choline. Search strings are provided (Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3).

2.3. Study Selection: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Two independent investigators (F.T. and A.T.) screened articles for inclusion using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria in Early Review Organizing Software (EROS, version 2.0)), as described in detail in the Appendix. To be eligible for inclusion, studies needed to (1) to be performed in mammals with a normal-growth pregnancy or a complicated pregnancy resulting in fetal growth divergence: FGR, pre-eclampsia (PE), pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH), GDM/diabetes mellitus, or prematurity; (2) to study the effects of oral supplementation with one of the 14 AAs for more than one day (at lib) or at least twice (as bolus) during pregnancy; and (3) to report one of the following outcomes: fetal/birth weight; maternal blood pressure (BP); maternal glucose or insulin levels; gestational weight gain; or development of pregnancy complications in human risk population including FGR, PE, PIH, GDM, prematurity, and neonates born small or large for gestational age (SGA or LGA). For human studies, we only included randomized controlled trials. The complete list of exclusion criteria is reported in the Appendix.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data were extracted in duplicate by F.T. and A.T. We extracted data on study characteristics, such as supplementation strategy and the (gestational) day of measurement, and for each outcome mean, SD, and number of subjects per experimental group were noted (see Appendix for more details).

2.5. Assessment of Risk of Bias and Study Quality

Risk of bias was assessed in duplicate by F.T. and A.T. using the risk of bias tools from SYRCLE for animal studies [30] and from the Cochrane Collaboration (Review Manager 5.3.5, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) for human controlled trials. Adjustments to the tools are described in Appendix. Studies were not excluded based on poor study quality.

2.6. Meta-Analysis

Meta-analyses were performed separately for normal-growth versus complicated pregnancies versus pregnancies at-risk of complications. All animal species were pooled together, and the analyses were performed for each AA group for each outcome only when more than five studies could be included. Fetal/birth weight (primary outcome) was compared between groups as a ratio of means (ROM) and, in humans, additionally presented as a mean difference (MD). Maternal BP, blood glucose or insulin levels, and gestational weight gain were presented as an MD, and development of pregnancy complication was presented as an odds ratio (OR). Pooled effect size estimates are presented with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Data were analyzed using random- or mixed effects models, using nesting if multiple cohorts from one study were included [31].

Meta-regression analyses were performed to study effects of modifiable factors in the complicated pregnancy group only, and were only performed if at least two studies per category were present. When studies reported data on multiple cohorts (e.g., multiple dose), then these were included in the meta-analysis as independent comparisons. Meta-regression was performed on species, type of pregnancy complications, administration timing (full pregnancy vs. partly), and scheme (continuous vs. interval), intervention type (prevention or treatment), and control diet (isonitrogenous vs. not isonitrogenous in arginine family). For BP analysis, we used mean arterial pressure and, when not available, systolic BP. For the dose–response curves, a metabolic weight conversion was applied by a linear scaling exponent of 0.75 to correct for interspecies pharmacokinetic conversion [31].

A two-sided p-value below 0.05 was considered significant. Potential publication bias was visually examined in funnel plots and tested by Egger’s regression when over twenty studies reported an outcome. Heterogeneity (I2) among studies > 50% was considered significant. An influential case analysis was performed by examining residuals, weights, and Cook’s distances of model fits. A sensitivity analysis was executed by removing influential cases and by shifting cut-outs for meta-regression of MD or ROM. R software (v. 3.5.3, The R Core team, Auckland, New Zealand) and the Metafor package were used for all statistical analyses [32].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Overall Study Characteristics

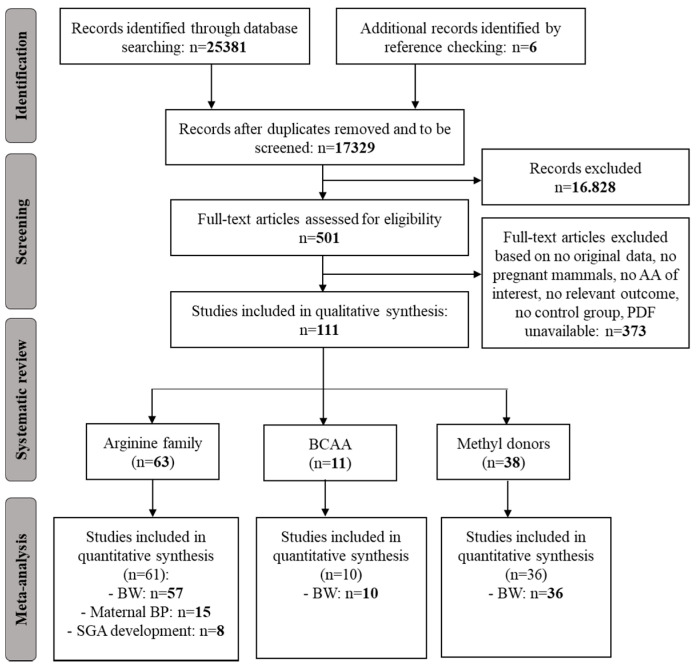

The search resulted in 17.329 hits. The majority of exclusions during the full-text screen was based on no in vivo studies on pregnant animals or humans followed by no supplementation of the amino acids of interest and resulted in 501 studies for full-text screening, of which we included 111 studies in our systematic review (Figure A1). We included 5 mouse, 40 rat, 4 guinea pig, 1 rabbit, 9 sheep, 23 pig, 7 cow, and 22 human studies. None of the included studies reported on asparagine or ornithine supplementation. Table A4 summarizes which outcome was reported per study and total data-extraction per outcome is reported in Table A5, Table A6, Table A7, Table A8 and Table A9.

3.2. Overview Performed Meta-Analyses

We performed meta-analyses on fetal/birth weight following supplementation with AA in the arginine family, BCAA, and methyl donors. Regarding maternal BP and development of SGA, the arginine family was the only AA group for which a meta-analysis could be performed. A meta-analysis on the development of other pregnancy complications was not possible. Data for gestational weight gain were not pooled because, (1) without individual participant data, we had to estimate the mean weight gain and SD for studies that did report gestational weight at two different time points during pregnancy per group; (2) studies reported gestational weight gain over different gestational time periods, which did not consistently match the supplementation periods; and (3) gestational periods are very different between species. Too few studies reported on glucose levels to pool these data. No data on insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) were found. Results on glucose and gestational weight gain are described in the Appendix.

3.3. Arginine Family

3.3.1. Effect of Prenatal AA in Arginine Family on Fetal Growth

Study Characteristics

Data were extracted on fetal growth in response to prenatal supplementation of arginine family AA from 47 animal studies (1 mouse [33], 18 rat [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51], 6 sheep [52,53,54,55,56,57], 20 pig [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77], and 12 human studies [78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89] (Table A5). Most studies were supplemented with arginine (n = 47) [33,34,35,36,37,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89], followed by glutamate (n = 10) [40,41,54,55,56,57,63,65,66,77], citrulline (n = 3) [38,39,44], glutamine (n = 2) [42,67], proline (n = 1) [68], and aspartic acid (n = 1) [43]; 7 studies had two treatments arms, 6 studies with arginine and (N-Carbamyl) glutamate (NCG) [54,55,56,57,63,77] and 1 study with arginine and citrulline [44]. The human studies, all supplementing arginine, were performed in Poland (n = 4) [84,85,86,87], Italy (n = 2) [79,83], Norway (n = 1) [89], France (n = 1) [80], Mexico (n = 1) [78], USA (n = 1) [82], China (n = 1) [81], and India (n = 1) [88].

Meta-Analyses

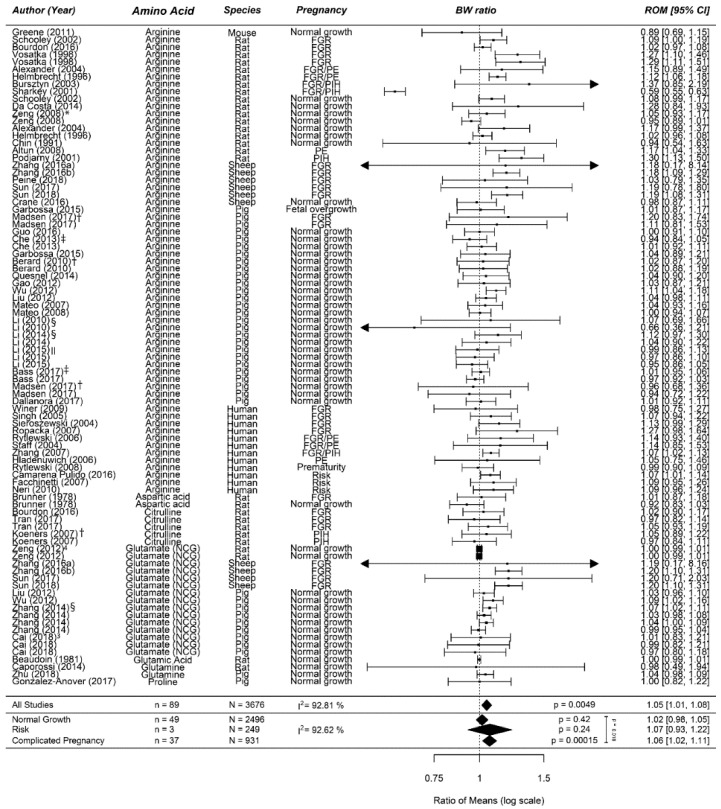

Supplementation of prenatal AA from the arginine family increases birth weight by 6% (1.06 (1.02; 1.11)) in complicated pregnancies (Figure 1). No effect was observed in normal-growth pregnancies (1.01 (0.98; 1.05)) or the risk population (1.07 (0.93; 1.22)). In animal studies only, no differences were observed in normal pregnancies and arginine increased birth weight by 8% (1.08 (1.03; 1.13)) in complicated pregnancies. There were no at-risk studies conducted in animals. In human studies only, no differences were observed in normal-growth pregnancies and an increase in at-risk pregnancies (ROM 1.08 (1.02; 1.13) or MD 219 g (65; 374)) and complicated pregnancies (ROM 1.07 (1.03; 1.11) or MD 162 g (69; 255)).

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis on prenatal supplementation of amino acids from the arginine family on fetal/birth weight (BW): While there was no effect of prenatal supplementation of amino acids from the arginine family in normal-growth pregnancies, it increased the birth weight ratio in a risk population and in complicated pregnancies. The data is ordered within each amino acid from smallest to largest animal. Data represent pooled estimates expressed as a ratio of means (ROM) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) using a random effect model. Residual I2 is shown. Some studies had multiple cohorts and are distinguishable in this figure by the following: * supplementation during full pregnancy in this upper line compared to partial in the next line; † this upper line is female offspring compared to the next line which is male offspring; ‡ in this upper line, the supplementation period was shorter compared to the next line(s); § in this upper line, the daily dose is lower compared to the next line(s); || in this upper line, primigravid animals were used compared to the next two lines of multigravida animals; and in the last two lines, the dose differed with the first one being the highest dose. FGR, fetal growth restriction; I2, heterogeneity; NCG, N-(Carbamyl) glutamate; PE, preeclampsia; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

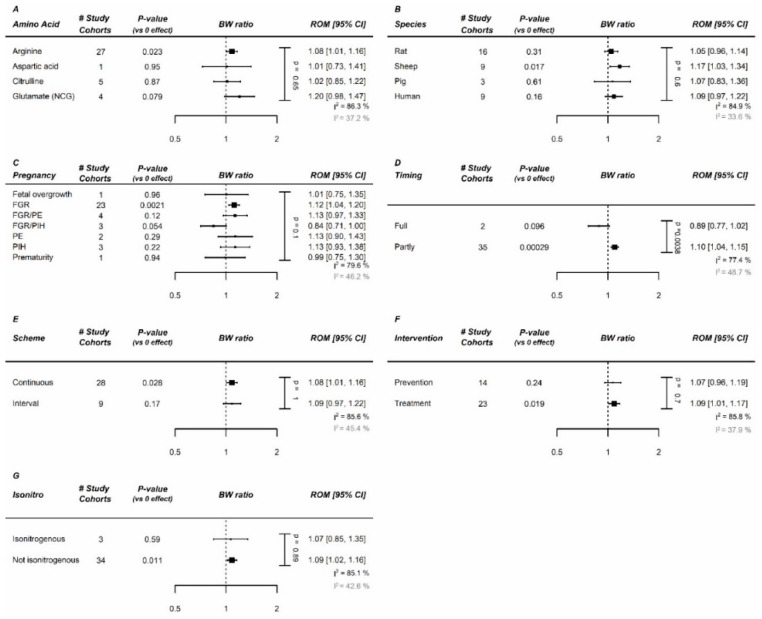

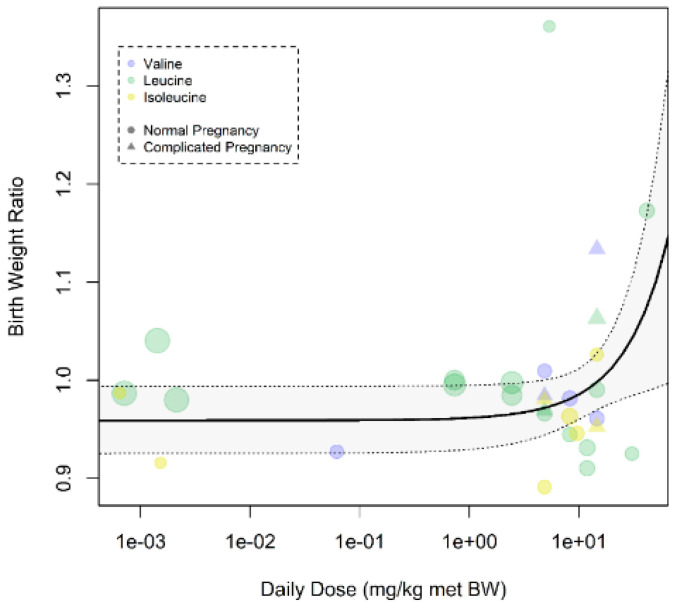

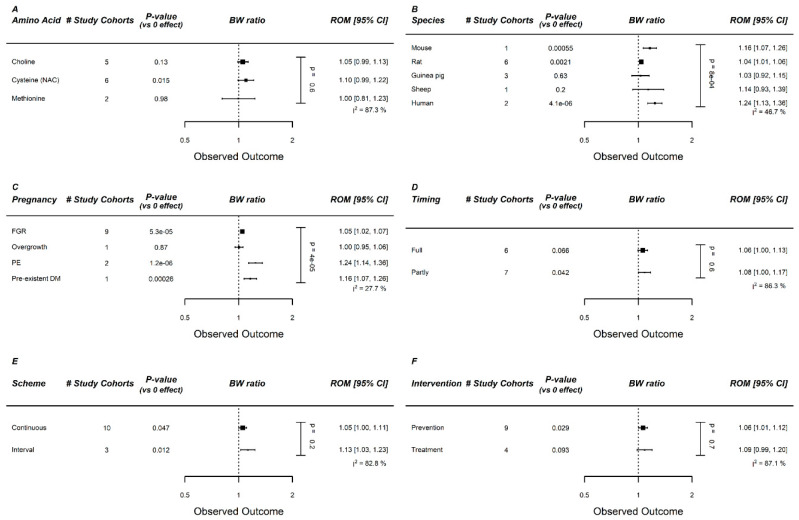

Within complicated pregnancies, arginine and NCG appeared to be the most effective AAs in the arginine family (Figure 2A). The largest increase was noted in sheep (Figure 2B), in which supplementation consisted of either arginine or NCG. For humans, the effect was also significant (increase of 9%). The effect was comparable between different (induced) pregnancy complications (Figure 2C). AAs from the arginine family appeared to be more effective when supplemented during only one phase of pregnancy, but only two studies supplemented AAs during full pregnancy (Figure 2D). The administration scheme (continuous vs. interval) was not influential (Figure 2E). We observed no effect of a preventive approach versus a therapeutic approach (Figure 2F). Note that, while we did not see clear differences between isonitrogenous vs. non-isonitrogenous control diets, most studies (including all human studies) failed to use isonitrogenous control diets (Figure 2G). Interpretation of the significance of each meta-regression remained unchanged after p-value correction for the 7 modifiers (p = 0.05/7 = 0.007). A dose–response relation for birth weight was absent with an effective daily dose already reached at the lowest tested dose (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Meta-regression of arginine family on fetal/birth weight (BW) in complicated pregnancies: Meta-regression in complicated pregnancies on (A) amino acids (AA), (B) species, (C) pregnancy complication, (D) administration duration, (E) administration scheme, (F) Intervention type (prevention vs. treatment), and (G) isonitrogenous vs. non-isonitrogenous in control arms. NCG and arginine are the most effective AAs, and the largest effect is observed in sheep models of pregnancy complication. Data represent pooled estimates expressed as ratio of means (ROM) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) using a random effect model. Residual I2 is shown, and in grey is the residual I2 after removal of the outlier Sharky et al. FGR, fetal growth restriction; I2, heterogeneity; PE, preeclampsia; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

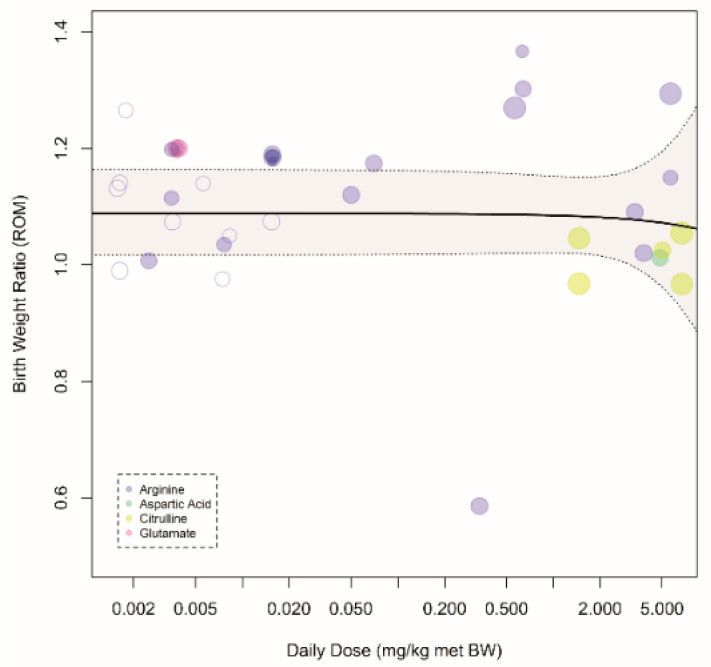

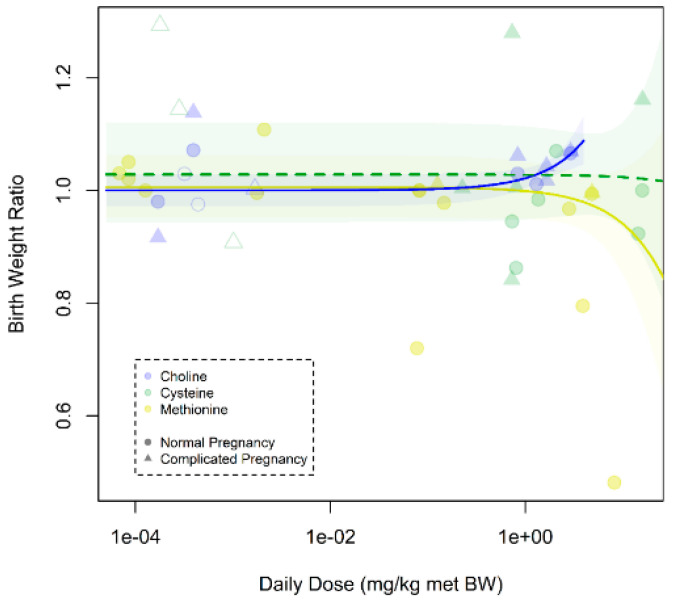

Figure 3.

Dose–response curve of prenatal supplementation of the arginine family on fetal/birth weight in complicated pregnancies: Daily dose is expressed as mg per kg metabolic body weight. Open dots indicate human studies, and closed dots indicate animal studies. There is no dose–response relation between prenatal supplementation of amino acids from the arginine family and birth weight ratio (pslope = 0.81). An increase of 10% was already reached at the lowest dose.

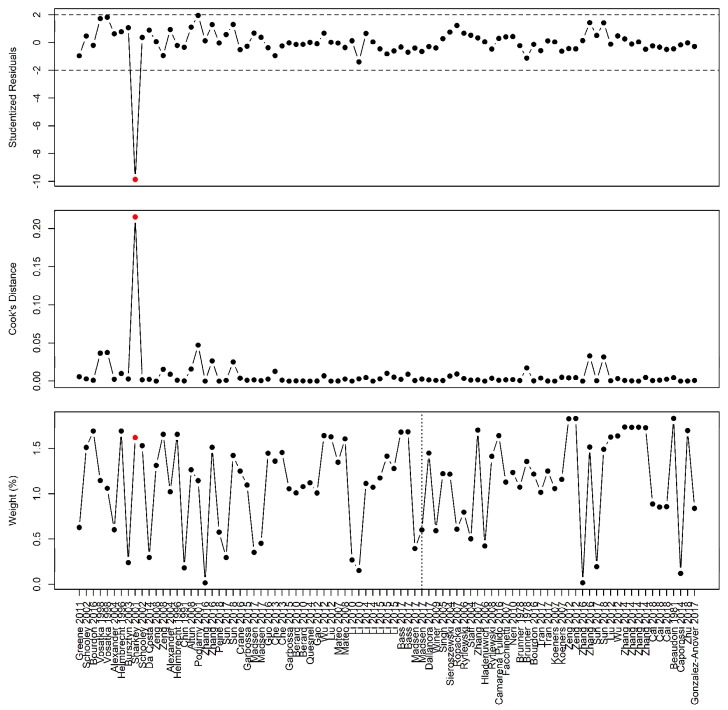

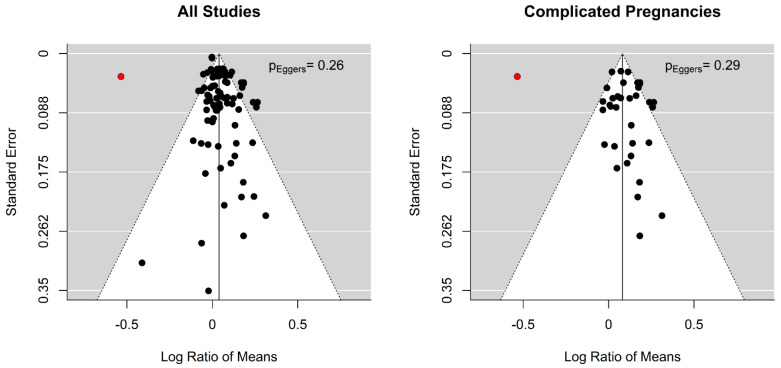

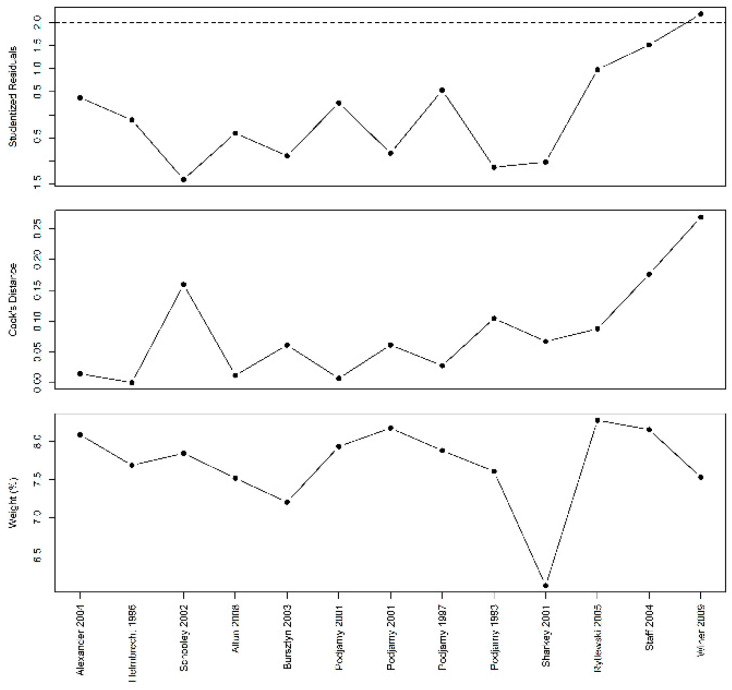

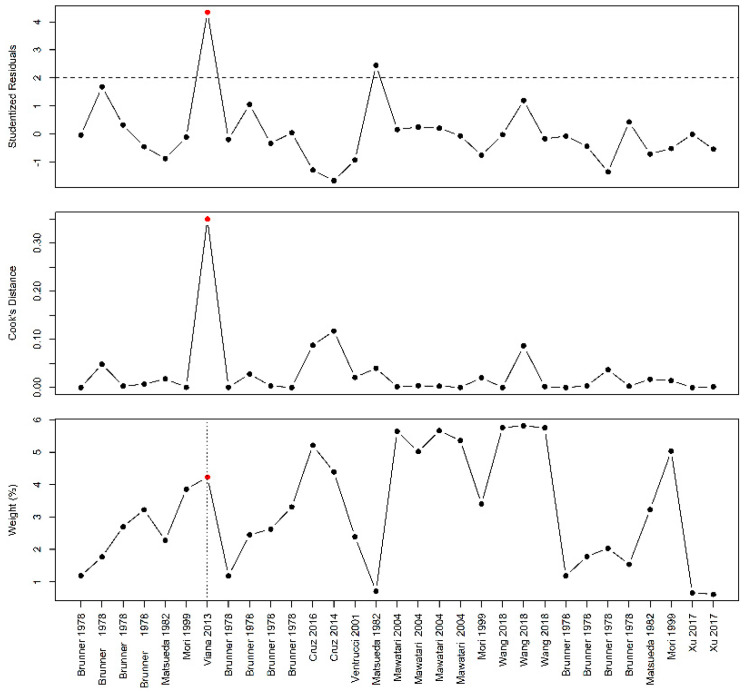

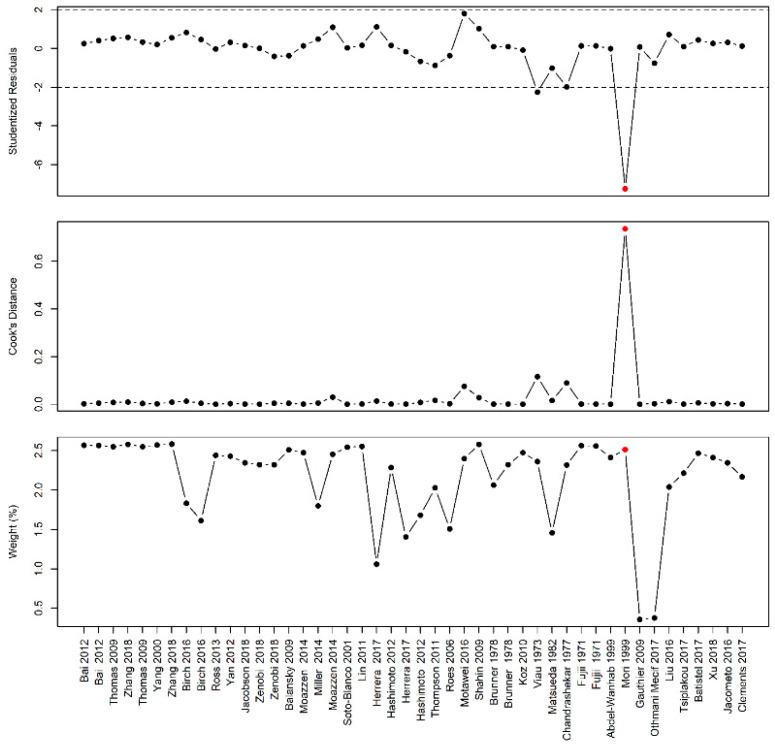

The sensitivity analysis identified the rat study by Sharkey et al. [51] as a sensitive case (Figure A2). Removing this study resulted in an increase in body weight by 9% (5; 12) in complicated pregnancy and a reduction of I2 from 93% to 77%. Visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested publication bias (Figure A3). However, Eggers regression did not confirm this (p = 0.26 for all studies and p = 0.29 for studies in complicated pregnancies).

3.3.2. Effect of Prenatal AA in Arginine Family on Maternal Blood Pressure

Study Characteristics

The effect on BP was reported in ten rat [34,35,45,48,49,50,51,90,91,92] and six human [78,80,83,89,93,94] studies following supplementation of either arginine (n = 15) [34,35,45,48,49,50,51,78,80,83,89,90,91,92,93] or citrulline (n = 1 [94] (Table A6). The human studies were performed in France [80], Italy [83], Norway [89], Poland [93], USA [94], and Mexico [78].

Meta-Analyses

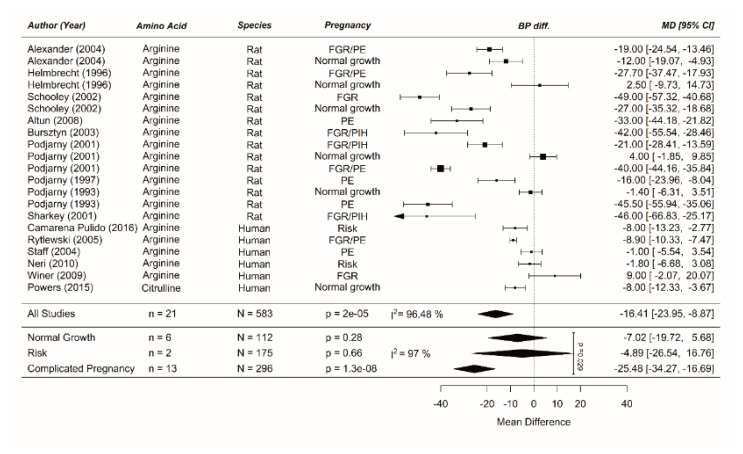

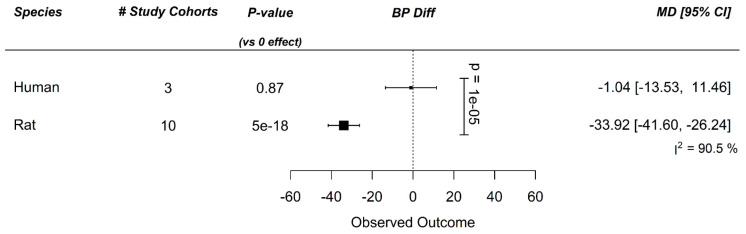

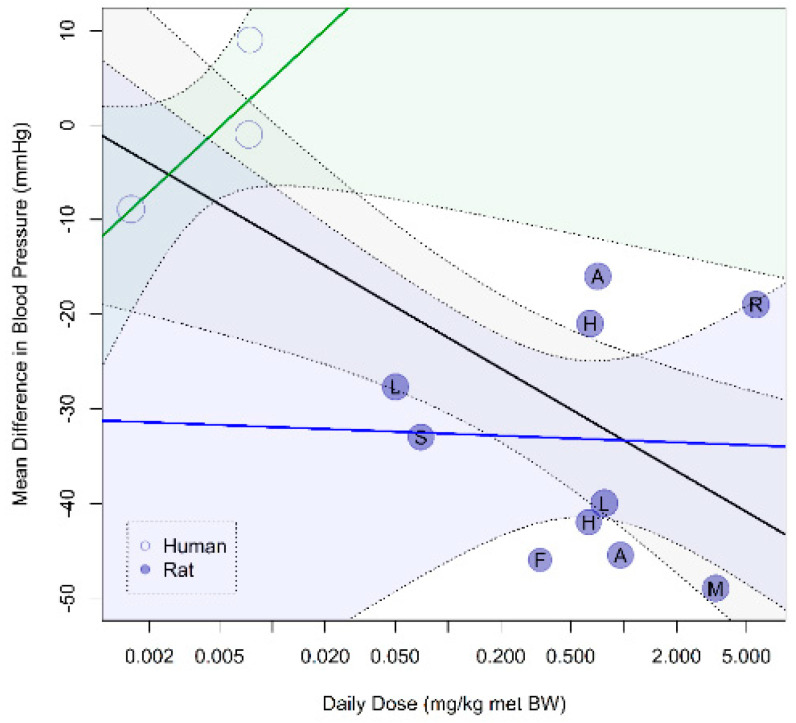

While prenatal supplementation with AAs from the arginine family did not affect BP in normal-growth pregnancies or the risk population, it reduced BPs, with 25 mmHg (−34; −17) in complicated pregnancies (Figure A4). However, this reduction was completely driven by animal studies. In human studies only, no significant BP reduction was observed in either normal-growth (−8 (−21; 5)), at-risk (−5 (−14; 5)), or complicated (−2 (−10; 6)) pregnancies. The BP difference was comparable for the type of BP (mean arterial pressure or systolic BP; data not shown; p = NS) [7,31]. Meta-regression showed high interspecies difference in the ten rat and three human study cohorts including pregnancy complications, thus we did not consider further meta-regression analysis rational (Figure A5). In contrast to birth weight outcome, higher doses did result in larger BP differences (Figure A6). Sensitivity analysis did not reveal specific influential cases (Figure A7).

3.3.3. Effect of Prenatal AA in Arginine Family on Prevention of Pregnancy Complications in Risk Populations

Study Characteristics

Prevention of pregnancy complications in human risk populations was mostly studied after arginine supplementation (n = 8) [78,79,83,85,86,87,95,96] Table A7). All studies reported on the prevalence of SGA. Neri et al. [83] assessed different cut-offs for SGA and showed that, with the same treatment strategy, the risk of developing SGA was lower when a lower cut-off for birth weight was used. This means that especially the more severe FGR was prevented. Only the cut-off of <p10 was included in our meta-analysis. Some of the cohorts also reported lower risk of preterm birth (n = 3) [78,79,83] and PE (n = 2) [78,79] and no effect on GDM risk (n = 1) [78], but there were too few studies to pool data for individual pregnancy complications. The human studies supplementing arginine were performed in Poland (n = 4) [85,86,87,95], Mexico (n = 2) [83,96], and Italy (n = 2) [79,83].

Meta-Analyses

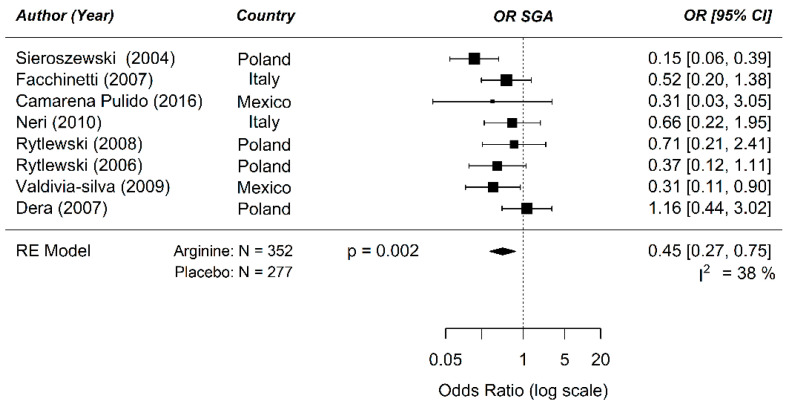

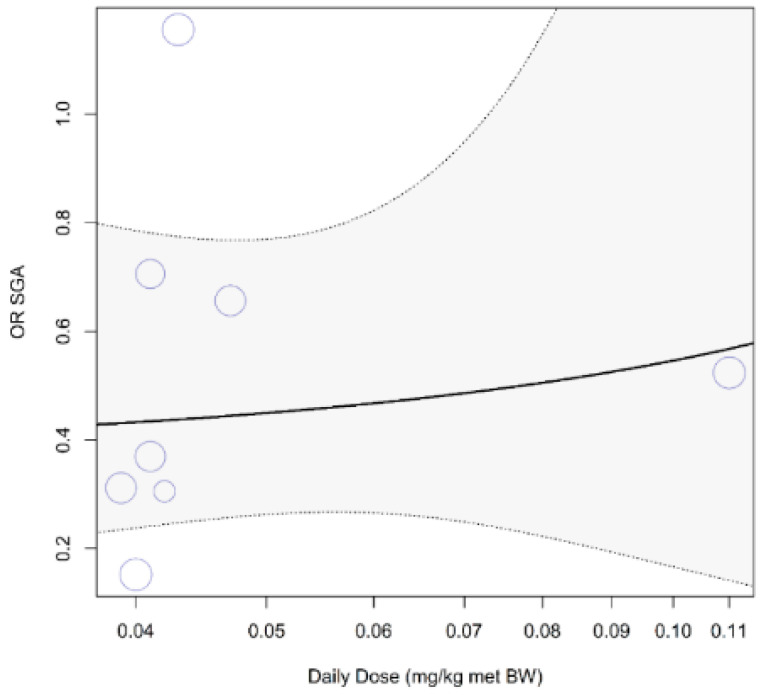

The odds ratio for developing SGA in a risk population between prenatal supplementation of arginine and placebo was 0.45 ((0.27; 0.75); p = 0.002) (Figure 4). The treatment strategies were similar in these studies (interval, partly, and non-isonitrogenous control diet). Therefore, further meta-regression analysis could not be performed. Based on the sparse data-points, mostly centered around the dose of 0.04 mg/kg, there does not appear to be a clear dose–response relationship (Figure A8).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis on the prenatal supplementation of arginine on the development of small for gestational age (SGA) in a human risk population: The odd ratio (OR) for developing SGA in a risk population was 0.45 following arginine supplementation during pregnancy compared to placebo (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.27; 0.75) using a random effect model. Residual I2 for heterogeneity is shown.

3.4. BCAA

3.4.1. Effect of Prenatal BCAA on Fetal Growth

Study Characteristics

Most studies reporting on fetal growth after BCAA supplementation were performed in rats (n = 7) [43,97,98,99,100,101,102], with a few in mice (n = 1) [103] and pigs (n = 2) [104,105]; no human studies were found (Table A5). Leucine was the most investigated BCAA (n = 9) [43,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,105], followed by valine (n = 4) [43,97,98,104], and isoleucine (n = 3) [43,98,99]. The studies performed by Brunner [43], Matsueda [97], and Mori [98] used all three BCAAs.

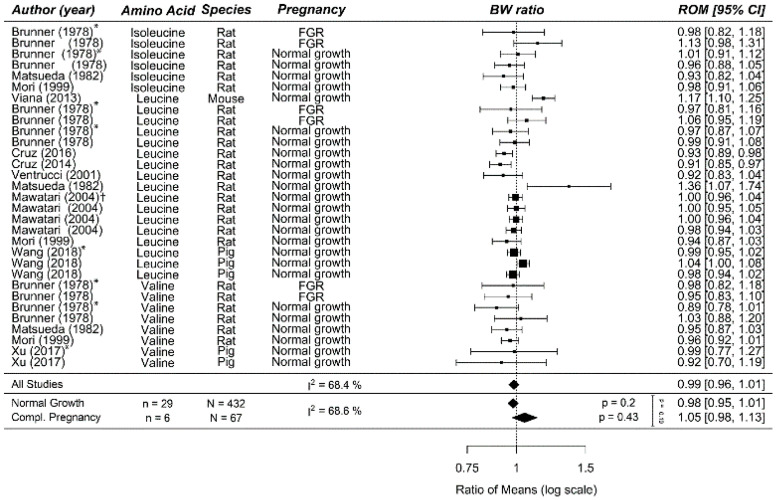

Meta-Analyses

Prenatal BCAA supplementation did not improve fetal/birth weight in normal-growth (0.98 (0.95; 1.01)) or complicated pregnancy (1.05 (0.98; 1.13), p = 0.24, I2 = 69%; Figure A9). We were unable to perform meta-regression because Brunner et al. [43] was the only study performed in pregnancy complications (phenylketonuria (PKU)-induced FGR). Brunner et al. [43] tested different dosages and showed that the highest tested dose of leucine and isoleucine were more effective in pregnancy complications. The dose–response curve showed that higher doses of leucine resulted in exponentially higher birth weight in all pregnancies (Figure A10). This effect was less clear for valine or for isoleucine.

Sensitivity analysis showed that Viana et al. [103], the only mouse study, was an influential case (Figure A11); removing this study had no significant effect on the pooled effect estimate (0.97 (0.95–0.99); p < 0.01), but did reduce I2 to 30%.

3.5. Methyl Donors

3.5.1. Effect of Prenatal Methyl Donors on Fetal Growth

Study Characteristics

We included 30 animal studies (mice n = 3 [106,107,108]; rats n = 14 [43,97,98,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119]; guinea pigs n = 4 [120,121,122,123]; rabbits = 1 [124]; sheep n = 3 [125,126,127]; and cows n = 5 [128,129,130,131,132]) and 6 human studies [133,134,135,136,137,138] reporting on fetal growth in response to prenatal methyl donor supplementation. In 16 of these studies, methionine was used [43,97,98,115,116,117,118,119,123,124,125,126,128,129,130,131] while 11 studies supplemented cysteine [106,107,108,113,114,120,121,122,133,134,137] and nine used choline [109,110,111,112,127,132,135,136,138]. Interestingly, considering our hypothesis, only one study used an overgrowth population [113] and only one used an at-risk-of-overgrowth population [132]. The human studies supplementing cysteine were performed in Egypt (n = 2) [133,137] and The Netherlands (n = 1) [134]. Studies supplementing choline were performed in USA (n = 2) [135,136] and South Africa (n = 1) [138].

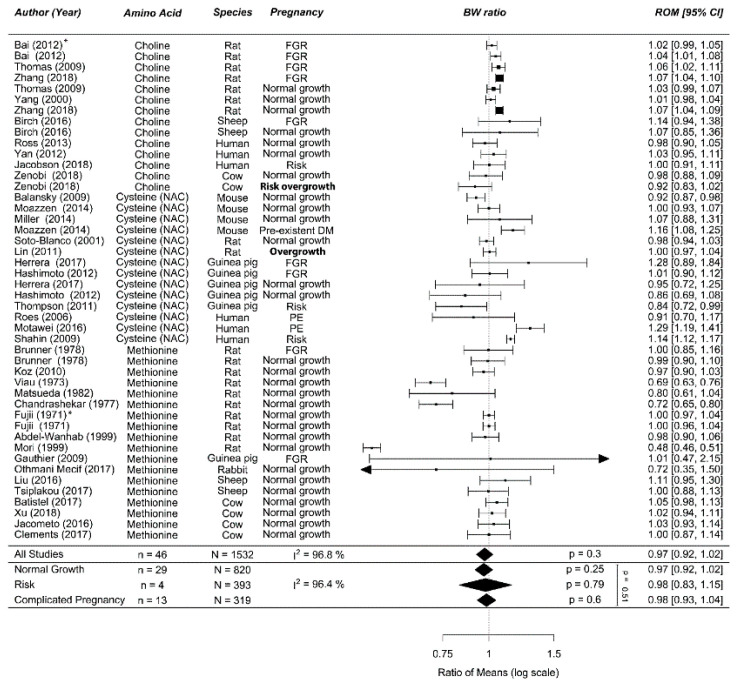

Meta-Analyses

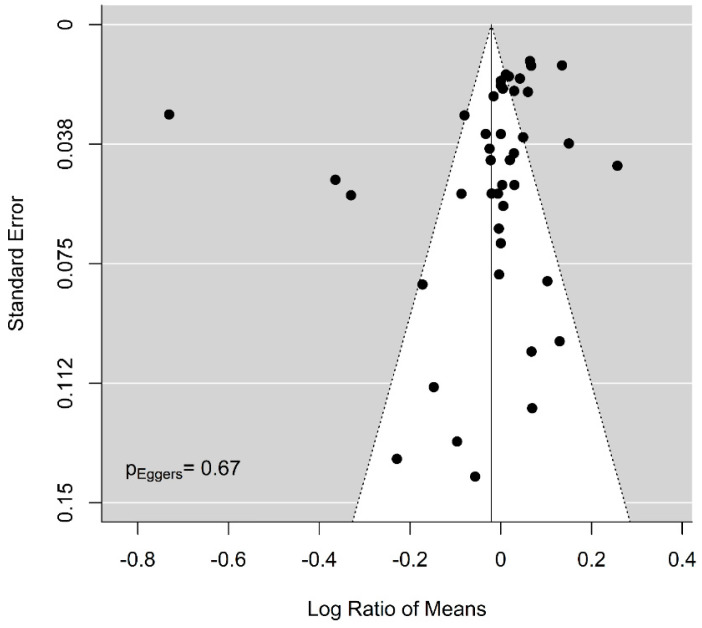

Overall, methyl donor supplementation during normal-growth (0.97 (0.92; 1.02)), risk population (0.98 (0.83; 1.15)), or complicated pregnancy (0.98 (0.93; 1.04)) did not alter birth weight (p = 0.46; I2 = 96%; Figure 5). The two Egyptian studies were the only human studies showing an improvement in birth weight. The dose–response curve showed that higher (excess) doses of methionine and cysteine resulted in a larger reduction of birth weight as was also visible in the forest plot for prenatal methionine in normal-growth pregnancies (Figure A12). Meta-regression showed a lack of effect for all three methyl donors in complicated pregnancies (Figure A13A). Methyl donor supplementation in the two overgrowth (risk) animal studies induced by excess energy and high fat diet failed to influence birth weight [113,132]. However, methyl donors appeared to increase birth weight especially in human pregnancies complicated by PE (Figure A13B,C). Meta-regression did not identify a more effective treatment strategy (Figure A13D–F). Interpretation of the significance of each meta-regression remained unchanged when the p-value was corrected for the 6 modifiers (p = 0.05/7 = 0.008). There was no clear publication bias visible in the funnel plot (Figure A14), which was supported by Eggers regression (p = 0.67). Sensitivity analysis showed that Mori et al. [98] was an influential case (Figure A15). Removing this study had no significant effect on the pooled effect estimate (0.99 (0.95; 1.02), p = 0.19, I2 = 91%) in normal-growth pregnancies. We speculate that the difference in effect in this study is caused by the high dose of methyl donor.

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis on prenatal supplementation of methyl donors on fetal/birth weight (BW): Prenatal supplementation of methyl donors did not affect birth weight in normal-growth, risk populations or complicated pregnancies. Data are ordered within each amino acid (AA) from smallest to largest animal. Data represent pooled estimates expressed as a ratio of means (ROM) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) using a random effect model. Residual I2 is shown. Only two studies included (risk of) overgrowth as their study population (bold). Some studies had multiple cohorts split up by sex indicated by *, in which the upper line represents male offspring compared to the next line which represents female offspring. FGR, fetal growth restriction; I2, heterogeneity; NAC, N-acetyl Cysteine; PE, preeclampsia; DM, diabetes mellitus.

3.5.2. Effect of Prenatal Methyl Donors on Prevention of Pregnancy Complications in Risk Population

Study Characteristics

Prevention of pregnancy complications in a human risk population was studied using choline (n = 2, USA and South Africa) [135,138] and cysteine (n = 2, Egypt and The Netherlands) [134,137] (Table A7). The included cohorts reported on the prevalence of SGA (n = 4) [134,135,137,138], LGA (n = 1) [135], preterm birth (n = 2) [135,137], PIH (n = 2) [135,138], PE (n = 1) [138], and GDM (n = 2) [135,138]. Three out of four methyl donor studies appeared to reduce the risk of developing SGA [134,137,138], while choline supplementation seemed to worsen GDM and LGA incidence [135,138]. However, there were not enough study cohorts to perform a meta-analysis. The two studies on PIH and the two studies on prematurity showed conflicting results.

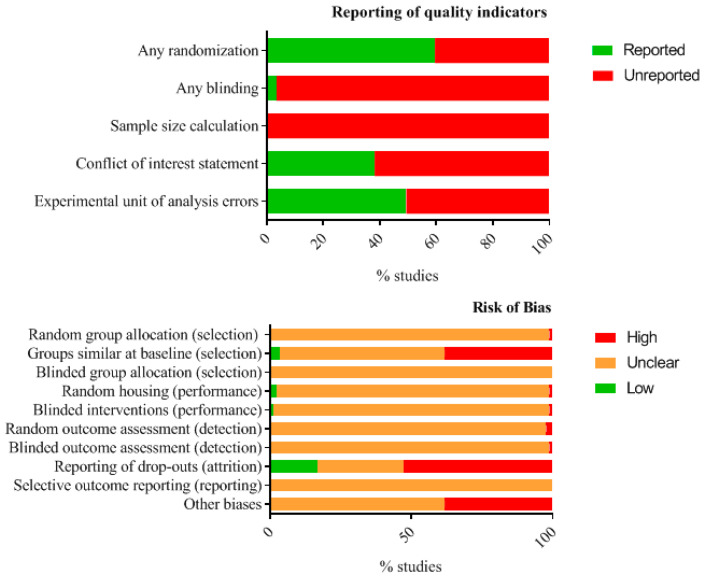

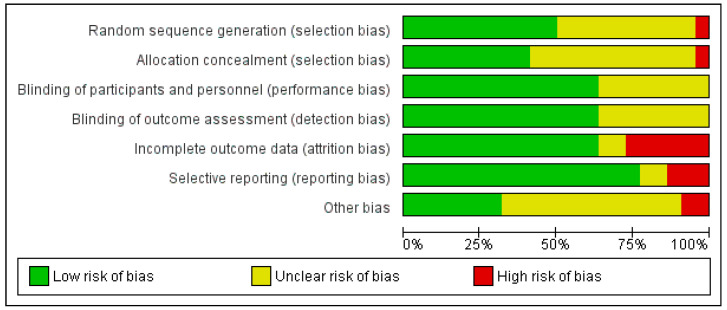

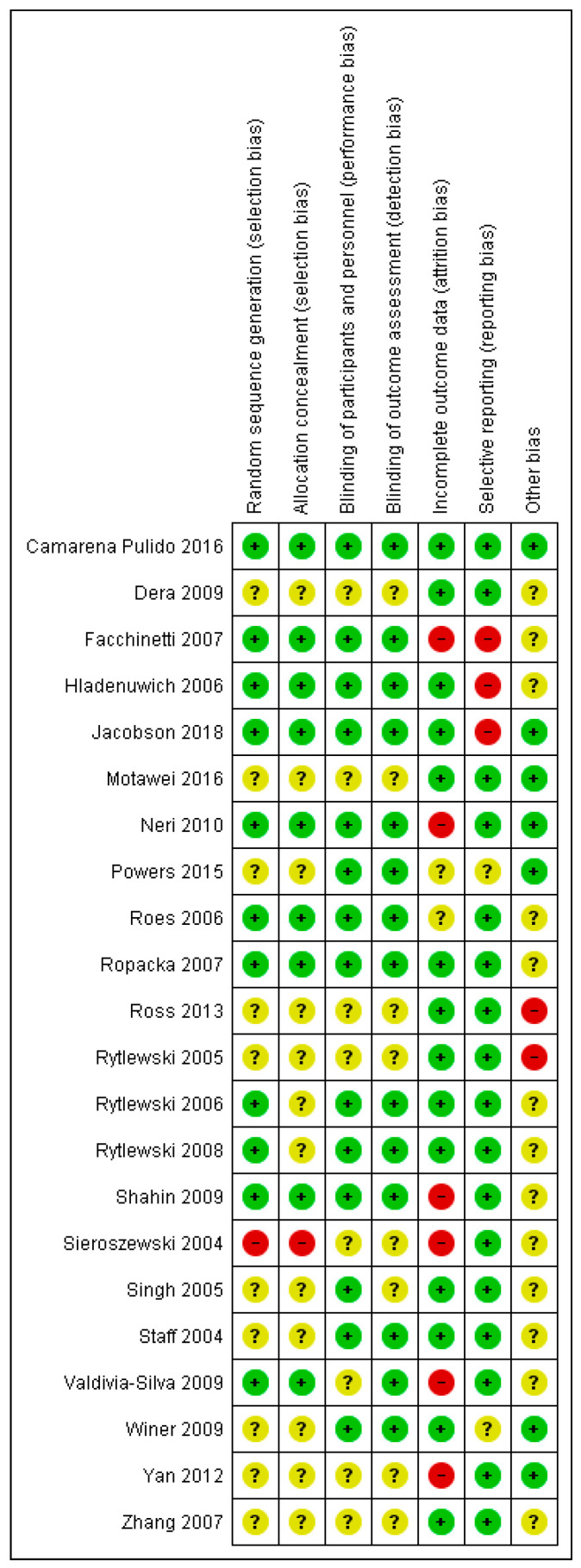

3.6. Study Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

The items to determine the risk of bias in animal studies were poorly reported and mostly unclear (Figure A16 and Table A10). The reporting of key indicators of study quality was poor. Especially blinding at any level of the experiment (3%) and power calculations (0%) were hardly reported. The item on experimental unit was important to detect potential statistical errors in the data analysis. In 51% of the studies, it was unclear whether respectively the mothers, or the individual offspring were used as a statistical unit. For risks of bias, a high risk of bias was most often observed for attrition bias (53%), followed by selection bias based on group similarity at baseline (38%). Nearly all studies had an unclear risk of bias for items concerning blinding and randomization (98–100%), because blinding and randomization were either not mentioned at all, or because the methodology used was not described. In human studies, attrition bias constituted the highest risk of bias as well. In addition, the methods used to achieve randomization and blinding were frequently unclear, as was the risk of potential conflict of interest (Figure A17). Only one study had a low risk of bias on all parameters, and the worst score included 3 high risk, 3 unclear risk, and 1 low risk item (Figure A18).

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis are unique in providing an elaborate overview of prenatal AA supplementation on fetal growth and related pregnancy complications in both humans and animals. Almost all studies focused on the effect of supplementation to target fetal undergrowth. Although 12 of the 14 searched AAs were included, arginine was by far the most studied for all outcome parameters.

4.1. Fetal Undergrowth

None of the three AA supplementation groups affected fetal growth in normal-growth pregnancies. Specifically, the arginine family improved fetal growth by 6% in complicated pregnancies. BCAA and methyl donors did not indicate an effect on fetal undergrowth; however, these data were sparse with, for example, only one BCAA study performed in growth-restricted pregnancies and no human studies at all. Within the competent arginine family, arginine and NCG were identified as the most potent, but due to co-linearity in sheep studies, and potential confounding by total nitrogen intake, we cannot conclude this with certainty. The beneficial effect of prenatal arginine supplementation on fetal growth was also reflected by the reduced risk of SGA development in the at-risk human population.

Our observed reduction of BP in hypertensive disorders during pregnancy could prolong pregnancy, thereby improving fetal growth. While there was a strong dose–response curve observed when data across species were combined, no effect or even a potential worsening of BP was observed after supplementation with arginine in women with PE and/or FGR. Arginine might therefore be indicated at low doses to prevent FGR but not as maternal indication to directly treat hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

The effects evaluated in the present studies might be related to the ability of the placenta to secure adequate essential AA supply towards the fetus, assuming that maternal protein (and nitrogen) intake is of adequate quantity and quality. This would plead for a combined intervention with multiple AAs. Beneficial effects of arginine family supplementation might be mediated through the NO pathway [22]. However, at this stage, we cannot rule out that the effects partially result from arginine stimulating placental nutrient transport or (fetal) protein synthesis through the mTOR pathway [24,139]. This would align with the mTOR-mediated alleviation of FGR observed after leucine supplementation [140].

4.2. Fetal Overgrowth

We hypothesized that methyl donors could potentially normalize overgrowth. Unfortunately, only two studies used methyl donor supplementation (and one used arginine) in overgrowth (risk) pregnancies, leaving the answer to the research question inconclusive. Methionine at (very) high doses reduced fetal growth in normal-growth pregnancies. This is potentially due to reduced maternal food intake and a reduction in ovarian steroidogenic pathway activity that could be rescued by administration of exogenous estrone and progesterone [98,116,119]. However, even in rats administered estrone and progesterone, fetal weight was still reduced compared to pair-fed controls, so additional mechanisms may be involved [116,119]. Several human studies have also reported side effects of methionine at extremely high levels [141].

Very little research was performed in diabetic pregnancies regarding the possible effect of AA supplementation on glucose and insulin levels. However, oral administration of choline prior to and during pregnancy in mouse models of maternal obesity has been reported to reduce fetal overgrowth [26,142], which is a common complication in diabetic pregnancy.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

The major strength of this meta-analysis involves integration of data across species. This relatively novel but increasingly used methodology has been shown to be of great value to improve translation from animal studies to humans in several fields since (1) they provide insight on the safety of interventions because of the larger range of dosages, (2) they aid in determining factors influencing the effect size, (3) they reveal biases thus leading to less misinterpretation, and (4) they clarify differences in design between animal and human studies [143,144]. For instance, we previously showed that a large RCT might not have not observed benefits of a treatment due to underdosage [31]. In this integrated meta-analysis, we additionally combined different groups of AAs that act through different pathways, but included only oral supplementation, and different dosages, all to get one step closer to the bedside. This was a valuable approach for the arginine family, but the relative scarcity of studies performed in complicated pregnancy settings compared to normal-growth ones for the BCAAs and methyl donors limited our ability to draw conclusions about which AAs would be most efficient.

Higher heterogeneity in this integrated type of meta-analysis compared to clinical meta-analyses is inevitable due to the inclusion of different experimental designs. Of note, the aim of a meta-analysis of animal studies alone or combined with human studies is not to pinpoint the effect estimated to directly drive clinical practice. Rather, their goal is to investigate factors influencing treatment efficacy, by determining sources of heterogeneity. As such, high heterogeneity provides the chance to explore its source, and the results generate new hypotheses on how to improve efficacy of the intervention or design of future (human) studies. However, the relatively high heterogeneity in our meta-analysis could not always be fully explained by the performed meta-regression. Socio-economic status taken as a surrogate for baseline nutritional status could influence in particular the results of human supplementation, but included studies were performed either in countries with a similar socio-economic status/ethnics division or that did not have a different impact on effect size. Furthermore, animal models represent a part of a complex syndrome and could influence the results, with our main concern regarding studies supplementing with arginine in compromised animal models by a manipulated NO-pathway However, we could not identify an effect on birth weight or blood pressure when excluding studies using L-NAME-induced animal models.

Our risk of bias tool revealed that most human and animal studies failed to report on quality items or risk of bias items. The unclear risk of bias must be taken into account when interpreting the results (of the individual studies and of our meta-analysis). As we did not exclude any studies based on their risk of bias score, this may have contributed to the high heterogeneity (although it was unclear to what extent, as they were not reported). One study [51] could be considered an influential case in our meta-analysis, since removal of this study would result in a significant drop in I2 value in both the overall meta-analysis and meta-regressions on the effect of arginine family supplementation and birth weight. However, we could not find any reason for the apparent atypical result found in this study (and have therefore not excluded this study from analysis).

Furthermore, fetal/birth weight is an interesting direct pregnancy outcome, but it does not necessarily correlate with other important obstetric, neonatal, and developmental programming outcomes related to improved long-term health. Hence, BCAA or methyl donors could have no effect on birth weight while still having beneficial or adverse developmental programming effects [145,146]. This was beyond the scope of our meta-analysis.

4.4. Perspectives

Overall, this systematic review gives a broad overview of the reported effects of oral prenatal AA supplementation on fetal growth and related pregnancy outcomes. We conclude that none of the AA groups had any adverse effects on fetal growth at low doses. Supplementation with AAs from the arginine family improved birth weight in complicated pregnancies, and reduced risk of SGA development in a human risk population. However, the potency on maternal BP was less clear and the arginine family might not be indicated as maternal treatment for hypertensive disorders of pregnancies. Based on this systematic review and meta-analysis, we formed recommendations for future research, which are summarized in Table 1. We plead for better and well-controlled study designs by using the most suitable study population and animal models, isonitrogenous control diets, and similar baseline nutritional state. In addition, the risk of bias could be reduced by a preplanned protocol describing the intended outcomes, and blinding and randomization methods. Supplementation of BCAA and methyl donors requires more research in animal studies to subsequently determine their potential on fetal growth, blood glucose, and HOMA-IR in models of pregnancies complicated by GDM or fetal overgrowth. The optimal combination of several AAs complemented with potential co-factors should be determined in future research. However, the beneficial effects that this review presents encourages a human RCT on supplementation of arginine family members, with an isonitrogenous control diet, to treat and prevent fetal growth restriction.

Table 1.

Recommendations for future research.

| Type of AA | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Arginine family |

|

| BCAA |

|

| Methyl donors |

|

| General |

|

AA, amino acid; BCAA, branched chain amino acids; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; NCG, N-Carbamylglutamate; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alice Tillema for her help with the search string, and Dongdong Xia for his help with Chinese translation of the study published by Zhang et al. (2007).

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Expanded Methods

Appendix A.1.1. Study Selection: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The screening of hits was conducted by two independent investigators, first based on their title and abstract and, subsequently, eligible articles were screened for final inclusion based on their full-text. A third investigator was consulted when consensus was not reached.

Appendix A.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded in cases of combined intervention (e.g., supplementation with two or more AAs in the treatment arm), other administration routes than oral, intervention not during pregnancy, pre-conceptional administration, supplementation other than the 14 specified AAs, no control treatment group present, non-mammals, no outcome of interest as previously mentioned, irretrievable full-text or meeting abstract irretrievable, or if the research articles on the studies did not contain unique primary data.

Appendix A.1.3. Data-Extraction

Data was extracted on study characteristics, including species, strain, animal model, pregnancy complication, and maternal weight. Pregnancies complicated by placental insufficiency were labelled as one or a combination of the following: fetal growth restriction (FGR), preeclampsia (PE), or pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH). Regarding supplementation strategy, we extracted data on the dose in grams per kg body weight per day, the duration of supplementation, the timing during pregnancy (partly or full), the administration scheme (continuous versus interval), the intervention type (prevention or treatment), and whether an isonitrogenous control diet was provided. Maternal weight was used to calculate the dose in grams per kg body weight per day, and maternal weight was estimated when not provided. For birth/fetal weight, the number of offspring and sex was also extracted. For maternal BP, the method and type of measurement were extracted. We also extracted whether BP measurements were performed under stressful condition; in humans, whether it concerned a 24 h or office BP measurement; and in animals, whether BP was measured under restrained or unrestrained conditions.

When data was only presented graphically, we used a graph digitizer to extract the data (http://arohatgi.info/WebPlotDigitizer/). We contacted corresponding authors once per email in case of missing data. SEM and pooled SEM were converted to SDs. The Hozo formula was used to estimate the mean and SD when the median was reported [147].

Appendix A.1.4. Amendments to Protocol

The following amendments to the review protocol were made post hoc: dose–response curves, meta-regression in type of pregnancy complication, and isonitrogenous versus non-isonitrogenous control diet in arginine family. We also changed the categories early, mid, late, and full gestational to partly vs. full gestational, because most studies reported overlapping parts during pregnancy (e.g., early-mid) which resulted in multiple categories with only one study per category. Also, pregnancy “trimesters” and the stage of development were difficult to compare between species. We extracted data on basal protein intake, but we could not perform our initial planned meta-regression. Since the cut-off of when basal protein intake is too low differs per species, and the individual intake and maternal weight (gain) were not reported, we could not convert the extracted data into a unit of measurement that we could pool.

Appendix A.1.5. Adjustments Made to the Risk of Bias Tools

To the SYRCLE tool, we added the reporting item whether the correct experimental unit was used. For the item of comparable baseline characteristics, we assessed (1) whether induction of the animal model occurred at the same gestational age, (2) whether the age or weight of pregnant animal was similar (<10% difference), and (3) whether parity (virgin or multiple pregnancies) was similar between groups. Other risks of bias within the Cochrane tool entailed a statement of no conflict of interest.

Appendix A.2. Expanded Results

We also searched each paper for data on protein intake and body composition. Body composition was never mentioned; therefore, meta-regression was not possible. Below, we describe, in the few studies where these data were available, the effect of prenatal supplementation of AA from the arginine family, BCAA, and methyl donors on maternal weight gain and blood glucose levels.

Appendix A.2.1. Effect of Prenatal AA in Arginine Family on Maternal Weight Gain and Blood Glucose Levels

Gestational weight gain was reported in 23 animal studies (1 mouse [33], 10 rat [36,37,43,44,45,46,49,90,91,148], 3 sheep [53,54,55], and 9 pig/swine [58,59,66,67,69,74,75,76,149]) and only 1 human study (Poland) [95] (Table A8). Again, the most studied amino acid was arginine (n = 19) [33,36,37,44,45,46,49,53,54,55,58,59,69,74,75,76,90,91,95], but also glutamate (n = 5) [54,55,66,148,149], citrulline (n = 1) [44], and glutamine (n = 1) [67] were studied. Thirteen studies were conducted in normal-growth pregnancies only [33,37,46,58,59,66,67,69,74,75,76,148,149], seven were conducted in complicated pregnancies only [36,44,45,49,53,54,55], three studies had both normal-growth and complicated pregnancy arms [43,90,91], and one study was conducted in a risk population [95]. Of the 10 studies including complicated pregnancies, only 4 showed an increase in gestational weight gain [36,54,55]. As none of these studies included any normal-growth pregnancies, it is not possible to see whether the increase meant a normalization of gestational weight gain. The other 6 studies reported no significant effects on gestational weight gain. One of the two studies in at-risk cohorts showed a positive effect as well [49].

None of the studies reported HOMA-IR levels, and only seven animal studies reported blood glucose levels: two rat [45,49], one sheep [57], and three pig studies [67,74,77] (Table A9). All studies supplemented with arginine and two studies had an extra cohort with NCG supplementation [57,77]. None of the studies in normal-growth pregnancies (n = 3), complicated (n = 2), or at-risk pregnancies (n = 1) reported significant effects of arginine supplementation on maternal blood glucose levels.

Appendix A.2.2. Effect of Prenatal BCAA on Maternal Weight Gain and Glucose Levels

Maternal weight gain was reported in four rat studies; of these, Brunner [43], Matsueda [97], and Mori [98] tested in different treatment arms the effects of valine, leucine, and isoleucine and Ventrucci [101] studied only leucine supplementation (Table A8). Almost all studies included normal-growth pregnancies in which no effect was observed. The one study including pregnancies complicated by FGR found some effects in high-dose groups: a reduction in gestational weight gain following valine, an increase following leucine, and no significant effects of isoleucine [43]. Glucose levels could only be extracted from one study, using leucine supplementation in normal-growth pregnant rats [150]. In this study, leucine supplementation increased maternal blood glucose levels. As for the arginine family and maternal weight gain, we were unable to pool the data.

Appendix A.2.3. Effect of Prenatal Methyl Donors on Maternal Weight Gain and Glucose Levels

We included 9 animal studies on maternal weight gain, which were performed in mice (n = 1) [108], rats (n = 6) [43,97,98,109,112,114], sheep (n = 1) [125], and cows (n = 1) [151], and 3 human studies [135,136,138] (Table A8). Most studies used choline (n = 6) [109,112,135,136,138,151], but also methionine (n = 4) [43,97,98,125] and cysteine (n = 2) [108,114] were investigated. Nine studies used normal-growth pregnancies [97,98,108,114,125,135,136,151], one of which also included a complicated pregnancy arm [43]. Two studies used complicated pregnancies [109,112], and one study was conducted in an at-risk population [138]. None of the studies in complicated or at-risk pregnancies reported an effect.

We included four animal studies reporting on maternal blood glucose level in response to methyl donor supplementation [107,113,132,152] (Table A9). Maternal blood glucose levels remained in the same range following choline supplementation in two cow studies including normal-growth, FGR, or overgrowth risk [132,152]. However, the two cysteine studies reported significant increases in maternal blood glucose levels in a streptozotocin-induced pre-existent diabetes mellitus (DM) type 1 mice model [107] and an overgrowth risk rat model using high fat diet [113].

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Flow chart of the study selection process: Our search strategy retrieved 17,329 unique hits, of which we included 111 studies reporting on amino acid (AA) supplementation in our systematic review. Of these, 63 studies reported on arginine supplementation, 11 reported on branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) supplementation, and 38 reported on methyl donor supplementation. We pooled data on the effect of arginine supplementation on birth weight (BW) in 57 studies, on maternal blood pressure (BP) in 15 studies, and on small for gestational (SGA) development in risk populations in 8 studies. We were able to pool data on the effect of BCAA on BW in 10 studies and of methyl donor supplementation in 36 studies. Adapted from PRISMA [29].

Figure A2.

Influential case analysis of studies reporting on arginine family supplementation and fetal/birth weight: A sensitivity analysis revealed Sharkey et al. as an influential case [51].

Figure A3.

Funnel plot for amino acids of the arginine family and fetal/birth weight in all studies and in studies with only pregnancy complications: These funnel plots and Egger’s regression did not indicate publication bias in all studies or studies in complicated pregnancies. Black dots are the included studies. Sharkey et al., as an influential case, was highlighted by the colour red [51].

Figure A4.

Meta-analysis on prenatal supplementation of arginine on maternal blood pressure: Blood pressure was unaffected in normal-growth pregnancies following arginine supplementation, but was reduced in the risk population and complicated pregnancies. The data is ordered within each amino acid (AA) from smallest to largest animal. Blood pressure difference (BP diff) data represent pooled estimates expressed as mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence interval (CI) using a random effect model. Residual is shown. FGR, fetal growth restriction; I2, heterogeneity; PE, preeclampsia; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Figure A5.

Species meta-regression of amino acids (AA) in arginine family on maternal blood pressure (BP) in pregnancy complications: Meta-regression revealed large interspecies differences, although only two human study cohorts versus seven rat study cohorts reported on the effect of prenatal supplementation of AA of the arginine family in complicated pregnancies. Data represent pooled estimates expressed as a mean difference (MD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) using a random effect model. I2, heterogeneity.

Figure A6.

Dose–response curve of prenatal supplementation of arginine family on blood pressure (BP) in complicated pregnancies: Higher doses of arginine result in lower maternal blood pressure in complicated pregnancies (pslope = 0.0031). However, this dose–response relation is influenced by an interspecies difference as the higher doses are tested in animal studies and the lowest doses are tested in human studies. Animal models for pregnancy complication included adriamycin nephropathy-induced preeclampsia (A), spontaneous hypertension and heart failure (F), hyperinsulinemic-induced PIH/FGR (H), L-NAME-induced fetal growth restriction/preeclampsia (L), magnesium deficiency-induced fetal growth restriction (M), reduced uterine perfusion pressure-induced fetal growth restriction/preeclampsia (R), and sonic stress-induced preeclampsia (S). Daily dose is expressed as mg per kg metabolic body weight. Open dots indicate human studies, and closed dots indicate animal studies. The black line is drawn for all studies, the yellow line is for animal studies only, and no line is drawn for human studies since only 3 studies were available.

Figure A7.

Sensitivity analysis of studies reporting on arginine family supplementation and maternal blood pressure: The sensitivity analysis revealed no clear outlier in studies reporting on arginine family supplementation on maternal blood pressure.

Figure A8.

Dose–response curve on the prenatal supplementation of arginine on development of small for gestational age (SGA): The available data points do not show a dose–response relation between odd ratio (OR) of development of SGA and daily arginine dose (pslope = 0.73) in a human risk population. Almost all studies clustered at the lower end of the dose spectrum.

Figure A9.

Meta-analysis on prenatal supplementation of branched chain amino acid on fetal/birth weight (BW): Prenatal branched chain amino acid supplementation did not affect birth weight, neither in normal-growth pregnancies nor in complicated pregnancies. Data are ordered within each amino acid (AA) from smallest to largest animal. Data represent pooled estimates expressed as a ratio of means (ROM) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) using a random effect model. Residual I2 is shown. Some studies had multiple cohorts and are distinguishable in this figure by the following: * in this upper line, the daily dose is lower compared the next line(s) in increasing order; † the upper two lines are in the lower dose compared to the next two lines, and per dose, the outcomes are separately reported for males first and then females. FGR, fetal growth restriction; I2, heterogeneity.

Figure A10.

Dose–response curve on prenatal supplementation of branched chain amino acid (BCAA) on fetal/birth weight in all pregnancies: There was a dose–response effect in which the highest doses resulted in a larger improvement of birth weight (pslope = 0.006). Only animal studies were included. Daily dose is expressed as mg per kg metabolic body weight.

Figure A11.

Sensitivity analysis of studies reporting on branched-chain amino acids supplementation and fetal/birth weight: The sensitivity analysis revealed Viana et al. [103] as an influential case.

Figure A12.

Dose–response curve on prenatal supplementation of methyl donors on fetal/birth weight in all pregnancies: There was a dose–response relationship between birth weight ratio and daily dose of methyl donors (pslope = 0.0002). Excessive doses of methionine and cysteine resulted in lower birth weight (methionine pslope = 1.09 * 10–5; cysteine pslope = 0.16). Daily dose is expressed as mg per kg metabolic body weight. Open dots indicate human studies, and closed dots indicate animal studies.

Figure A13.

Meta-regression of methyl donors on birth weight (BW): Meta-regression on (A) Amino acid (AA), (B) species, (C) pregnancy complication, (D) administration duration, (E) administration scheme, and (F) intervention type (prevention vs. treatment). No specific methyl donor was identified to be the most optimal. Methyl donor supplementation increased birth weight in human and preeclamptic studies (similar studies). Data represent pooled estimates expressed as a ratio of means (ROM) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) using a random effect model. FGR, fetal growth restriction; I2, heterogeneity; PE, preeclampsia; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Figure A14.

Funnel plot for methyl donors and fetal/birth weight in all studies: The funnel plot and Eggers regression do not indicate publication bias in studies reporting the effect of methyl donor supplementation on fetal or birth weight. Dots are the included studies.

Figure A15.

Sensitivity analysis of studies reporting on methyl donor supplementation and fetal/birth weight: The sensitivity analysis revealed Mori et al. [98] as a potential influential case.

Figure A16.

Reporting quality and risk of bias in animal studies: Reporting of key indicators of study quality and risk of bias in animal studies was assessed for all items, but especially blinding, randomization, and sample size calculation scored as unreported, unclear, or high risk.

Figure A17.

Risk of bias in human studies: Risk of bias assessment in human studies appeared to be very unclear for most items.

Figure A18.

Quality assessment of the included human studies by the Cochrane tool. Quality assessment using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. − = high risk of bias; + = low risk of bias; ? = unclear risk of bias.

Table A1.

Search terms in Pubmed.

| 14 amino acids AND administration | (“Arginine/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Arginine/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Arginine/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Arginine/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Arginine/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Arginine/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Arginine/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Arginine/therapy” [Mesh] OR “Leucine/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Leucine/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Leucine/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Leucine/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Leucine/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Leucine/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Leucine/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Isoleucine/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Isoleucine/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Isoleucine/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Isoleucine/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Isoleucine/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Isoleucine/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Isoleucine/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Valine/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Valine/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Valine/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Valine/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Valine/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Valine/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Valine/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Valine/therapy” [Mesh] OR “Cysteine/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Cysteine/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Cysteine/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Cysteine/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Cysteine/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Cysteine/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Cysteine/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Cysteine/therapy” [Mesh] OR “Methionine/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Methionine/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Methionine/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Methionine/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Methionine/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Methionine/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Methionine/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Methionine/therapy” [Mesh] OR “Glutamic Acid/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Glutamic Acid/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Glutamic Acid/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Glutamic Acid/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Glutamic Acid/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Glutamic Acid/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Glutamic Acid/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Glutamine/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Glutamine/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Glutamine/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Glutamine/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Glutamine/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Glutamine/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Glutamine/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Glutamine/therapy” [Mesh] OR “Citrulline/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Citrulline/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Citrulline/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Citrulline/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Citrulline/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Citrulline/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Citrulline/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/therapy” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Asparagine/therapy” [Mesh] OR “Aspartic Acid/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Aspartic Acid/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Aspartic Acid/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Aspartic Acid/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Aspartic Acid/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Aspartic Acid/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Aspartic Acid/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Aspartic Acid/therapy” [Mesh] OR “Proline/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Proline/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Proline/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Proline/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Proline/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Proline/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Proline/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Ornithine/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Ornithine/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Ornithine/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Ornithine/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Ornithine/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Ornithine/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Ornithine/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Choline/administration and dosage” [Mesh] OR “Choline/adverse effects” [Mesh] OR “Choline/deficiency” [Mesh] OR “Choline/drug effects” [Mesh] OR “Choline/pharmacology” [Mesh] OR “Choline/physiology” [Mesh] OR “Choline/therapeutic use” [Mesh] OR “Choline/therapy” [Mesh]) OR ((“Arginine” [Mesh] OR Arginine [tiab] OR L-Arginine [tiab] OR “Leucine” [Mesh] OR “Isoleucine” [Mesh] OR Leucine [tiab] OR L-Leucine [tiab] OR Leucin [tiab] OR Isoleucine [tiab] OR Isoleucin [tiab] OR Alloisoleucine [tiab] OR Alloisoleucin [tiab] OR “Valine” [Mesh] OR Valine [tiab] OR L-Valine [tiab] OR Valsartan [tiab] OR Valerate [tiab] OR “Cysteine” [Mesh] OR Cysteine [tiab] OR L-Cysteine [tiab] OR Cysteinate [tiab] OR Acetylcysteine [tiab] OR Carbocysteine [tiab] OR Cysteinyldopa [tiab] OR Cystine [tiab] OR cystein [tiab] OR cysthion [tiab] OR Selenocysteine [tiab] OR “Methionine” [Mesh] OR Methionine [tiab] OR L-Methionine [tiab] OR Liquimeth [tiab] OR Pedameth [tiab] OR Formylmethionine [tiab] OR Racemethionine [tiab] OR Adenosylmethionine [tiab] OR Selenomethionine [tiab] OR Vitamin U [tiab] OR acimetion [tiab] OR cotameth [tiab] OR lobamine [tiab] OR menin [tiab] OR menine [tiab] OR meonine [tiab] OR methiolate [tiab] OR methionin [tiab] OR methiotrans [tiab] OR methnine [tiab] OR methurine [tiab] OR metione [tiab] OR methidin [tiab] OR neutrodor [tiab] OR oradash [tiab] OR urosamine [tiab] OR Methyl Donor [tiab] OR “Glutamic Acid” [Mesh] OR glutamic acid [tiab] OR glutamate [tiab] OR MSG [tiab] OR vestin [tiab] OR “aminoglutaric acid” [tiab] OR “aminopentanedioic acid” [tiab] OR acidogen [tiab] OR acidoride [tiab] OR acidothym [tiab] OR acidulin [tiab] OR aciglumin [tiab] OR aciglut [tiab] OR aclor [tiab] OR antalka [tiab] OR flanithin [tiab] OR gastuloric [tiab] OR glusate [tiab] OR glutadox [tiab] OR glutamidin [tiab] OR “glutamin acid” [tiab] OR “glutaminic acid” [tiab] OR glutaminol [tiab] OR glutan [tiab] OR glutansin [tiab] OR glutasin [tiab] OR glutaton [tiab] OR hydrionic [tiab] OR hypochylin [tiab] OR levoglutamate [tiab] OR “levoglutamic acid” [tiab] OR muriamic [tiab] OR pepsdol [tiab] OR “Glutamine” [Mesh:NoExp] OR glutamine [tiab] OR “aminoglutaramic acid” [tiab] OR acutil [tiab] OR “adamin G” [tiab] OR glumin [tiab] OR glutamin [tiab] OR levoglutamide [tiab] OR levoglutamine [tiab] OR nutrestore [tiab] OR “Citrulline” [Mesh] OR citrulline [tiab] OR “ureidopentanoic acid” [tiab] OR ureidonorvaline [tiab] OR “ureidovaleric acid” [tiab] OR citrullin [tiab] OR carbamylornithine [tiab] OR “Asparagine” [Mesh] OR asparagine [tiab] OR asparagin [tiab] OR “aminosuccinamic acid” [tiab] OR “Aspartic Acid” [Mesh:NoExp] OR “D-Aspartic Acid” [Mesh] OR “Potassium Magnesium Aspartate” [Mesh] OR “aspartic acid” [tiab] OR aspartate [tiab] OR Magnesiocard [tiab] OR Mg-5-Longoral [tiab] OR Mg 5 Longoral [tiab] OR Mg5 Longoral [tiab] OR panangin [tiab] OR astra 2045 [tiab] OR “aminosuccinic acid” [tiab] OR “asparagic acid” [tiab] OR asparaginate [tiab] OR “asparaginic acid” [tiab] OR aspartyl [tiab] OR aspatofort [tiab] OR “levoaspartic acid” [tiab] OR “Proline” [Mesh:NoExp] OR proline [tiab] OR prolin [tiab] OR levoproline [tiab] OR “pyrrolidinecarboxylic acid” [tiab] OR pyrrolidine carboxylate [tiab] OR “Ornithine” [Mesh:NoExp] OR ornithine [tiab] OR ornithin [tiab] OR “Diaminopentanoic Acid” [tiab] OR “diaminovaleric acid” [tiab] OR “Choline” [Mesh:NoExp] OR choline [tiab] OR bursine [tiab] OR vidine [tiab] OR fagine [tiab] OR trimethylammonium hydroxide [tiab] OR amonita [tiab] OR bilineurine [tiab] OR biocholine [tiab] OR biocolina [tiab] OR cholin [tiab] OR hepacholine [tiab] OR laevocholine [tiab] OR levocholine [tiab] OR lipotril [tiab] OR luridine [tiab] OR sincaline [tiab] OR urocholine [tiab]) AND (“Dietary Supplements” [Mesh] OR “Administration, Oral” [Mesh] OR administration * [tiab] OR administer * [tiab] OR dose [tiab] OR doses [tiab] OR dosage [tiab] OR treatment [tiab] OR treated [tiab] OR supplement * [tiab] OR diet [tiab] OR diets [tiab] OR dietary [tiab] OR intake [tiab] OR intakes [tiab] OR consumption [tiab] OR consumptions [tiab] OR consume [tiab] OR nutraceutical * [tiab] OR nutriceutical * [tiab] OR therapy [tiab] OR therapies [tiab])) |

| AND | AND |

| Healthy pregnancy OR Complicated pregnancy | “Pregnancy” [Mesh] OR “gravidity” [Mesh] OR “Fetus” [Mesh] OR Pregnancy [tiab] OR Pregnancies [tiab] OR Pregnant [tiab] OR Gestation [tiab] OR Gestations [tiab] OR Gestational [tiab] OR gravidity [tiab] OR gravidities [tiab] OR gravid [tiab] OR fetus [tiab] OR foetus [tiab] OR fetal [tiab] OR foetal [tiab] OR childbearing [tiab] OR “child bearing” [tiab] OR “Fetal Growth Retardation” [Mesh] OR “Infant, Low Birth Weight “ [Mesh] OR “Infant, Premature” [Mesh] OR “Premature Birth” [Mesh] OR FGR [tiab] OR Intrauterine growth retardation [tiab] OR Intra-uterine growth retardation [tiab] OR Intrauterine growth restriction [tiab] OR Intra-uterine growth restriction [tiab] OR IUGR [tiab] OR Small for Gestational Age [tiab] OR SGA [tiab] OR Low birth weight [tiab] OR Premature baby [tiab] OR Pre-mature baby [tiab] OR Preterm baby [tiab] OR Pre-term baby [tiab] OR Premature babies [tiab] OR Pre-mature babies [tiab] OR Preterm babies [tiab] OR Pre-term babies [tiab] OR Premature child [tiab] OR Pre-mature child [tiab] OR Preterm child [tiab] OR Pre-term child [tiab] OR Premature children [tiab] OR Pre-mature children [tiab] OR Preterm children [tiab] OR Pre-term children [tiab] OR Premature infant * [tiab] OR Pre-mature infant * [tiab] OR Preterm infant * [tiab] OR Pre-term infant * [tiab] OR Premature newborn * [tiab] OR Pre-mature newborn * [tiab] OR Preterm newborn * [tiab] OR Pre-term newborn * [tiab] OR Premature neonate * [tiab] OR Pre-mature neonate * [tiab] OR Preterm neonate * [tiab] OR Pre-term neonate * [tiab] OR Premature birth * [tiab] OR Pre-mature birth * [tiab] OR Preterm birth * [tiab] OR Pre-term birth * [tiab] OR Neonatal prematurity [tiab] OR prematuritas [tiab] OR “Hypertension, Pregnancy-Induced” [Mesh] OR Pre-Eclampsia [tiab] OR Preeclampsia [tiab] OR pre-eclamptic [tiab] OR preeclamptic [tiab] OR preclampsia [tiab] OR Proteinuria Edema Hypertension Gestosis [tiab] OR Edema Proteinuria Hypertension Gestosis [tiab] OR EPH Gestosis [tiab] OR EPH Toxemia * [tiab] OR EPH Complex [tiab] OR “Placental Insufficiency” [Mesh] OR “placenta insufficiency” [tiab] OR “placental insufficiency” [tiab] OR “placenta insufficiencies” [tiab] OR “placental insufficiencies” [tiab] OR “placenta deficiency” [tiab] OR “placental deficiency” [tiab] OR “placenta deficiencies” [tiab] OR “placental deficiencies” [tiab] OR “placenta failure” [tiab] OR “placental failure” [tiab] OR “Fetal Macrosomia” [Mesh] OR Macrosomia * [tiab] OR high birth weight [tiab] OR “overweight infant” [tiab] OR “overweight infants” [tiab] OR “overweight newborn” [tiab] OR “overweight newborns” [tiab] OR “overweight neonate” [tiab] OR “overweight neonates” [tiab] OR “Diabetes, Gestational” [Mesh] OR “Pregnancy in Diabetics” [Mesh] OR diabetes gravidarum [tiab] |

Fourteen amino acids during pregnancy: arginine, citrulline, glutamate, glutamine, asparagine, aspartic acid, proline, ornithine, (iso-)leucine, valine, cysteine, methionine, and choline. The search was performed on 25 July 2018, with 14,169 records.

Table A2.

Search terms in Embase.

| 14 amino acids AND administration | (exp Arginine/OR (Arginine OR L-Arginine).ti,ab.) OR (exp Leucine/OR exp Isoleucine/OR (Leucine OR L-Leucine OR Leucin OR Isoleucine OR Isoleucin OR Alloisoleucine OR Alloisoleucin).ti,ab.) OR (exp Valine/OR (Valine OR L-Valine OR Valsartan OR Valerate).ti,ab.) OR (exp Cysteine/OR (Cysteine OR L-Cysteine OR Cysteinate OR Acetylcysteine OR Carbocysteine OR Cysteinyldopa OR Cystine OR cystein OR cysthion OR Selenocysteine).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp Methionine/OR (Methionine OR L-Methionine OR Liquimeth OR Pedameth OR Formylmethionine OR Racemethionine OR Adenosylmethionine OR Selenomethionine OR Vitamin U OR acimetion OR cotameth OR lobamine OR menin OR menine OR meonine OR methiolate OR methionin OR methiotrans OR methnine OR methurine OR metione OR methidin OR neutrodor OR oradash OR urosamine OR Methyl Donor).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp glutamic acid/OR (glutamic acid OR glutamate OR MSG OR vestin OR aminoglutaric acid OR aminopentanedioic acid OR acidogen OR acidoride OR acidothym OR acidulin OR aciglumin OR aciglut OR aclor OR antalka OR flanithin OR gastuloric OR glusate OR glutadox OR glutamidin OR glutamin acid OR glutaminic acid OR glutaminol OR glutan OR glutansin OR glutasin OR glutaton OR hydrionic OR hypochylin OR levoglutamate OR levoglutamic acid OR muriamic OR pepsdol).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp glutamine/OR (glutamine OR aminoglutaramic acid OR acutil OR adamin G OR glumin OR glutamin OR levoglutamide OR levoglutamine OR nutrestore).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp Citrulline/OR (citrulline OR ureidopentanoic acid OR ureidonorvaline OR ureidovaleric acid OR citrullin OR carbamylornithine).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp asparagine/OR (asparagine OR asparagin OR aminosuccinamic acid).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp aspartic acid/OR (aspartic acid OR aspartate OR Magnesiocard OR Mg-5-Longoral OR Mg 5 Longoral OR Mg5 Longoral OR panangin OR astra 2045 OR aminosuccinic acid OR asparagic acid OR asparaginate OR asparaginic acid OR aspartyl OR aspatofort OR levoaspartic acid).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp Proline/OR (proline OR prolin OR levoproline OR pyrrolidinecarboxylic acid OR pyrrolidine carboxylate).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp ornithine/OR (ornithine OR ornithin OR Diaminopentanoic Acid OR diaminovaleric acid).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp Choline/OR (choline OR bursine OR vidine OR fagine OR trimethylammonium hydroxide OR amonita OR bilineurine OR biocholine OR biocolina OR cholin OR hepacholine OR laevocholine OR levocholine OR lipotril OR luridine OR sincaline OR urocholine).ti,ab,kw.) AND (exp dietary supplement/OR exp nutrition supplement/OR (administration * OR administer * OR dose OR doses OR dosage OR treatment OR treated OR supplement * OR diet OR diets OR dietary OR intake OR intakes OR consumption OR consumptions OR consume OR nutraceutical * OR nutriceutical * OR therapy OR therapies).ti,ab,kw.) |

| AND | AND |

| Healthy pregnancy OR Complicated pregnancy | (exp pregnancy/OR exp fetus/OR (Pregnancy OR Pregnancies OR Pregnant OR Gestation OR Gestations OR Gestational OR gravidity OR gravidities OR gravid OR fetus OR foetus OR fetal OR foetal OR childbearing OR child bearing).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp intrauterine growth retardation/OR exp Low Birth Weight/OR exp prematurity/OR (FGR OR Intrauterine growth retardation OR Intra-uterine growth retardation OR Intrauterine growth restriction OR Intra-uterine growth restriction OR IUGR OR Small for Gestational Age OR SGA OR Low birth weight OR Premature baby OR Pre-mature baby OR Preterm baby OR Pre-term baby OR Premature babies OR Pre-mature babies OR Preterm babies OR Pre-term babies OR Premature child OR Pre-mature child OR Preterm child OR Pre-term child OR Premature children OR Pre-mature children OR Preterm children OR Pre-term children OR Premature infant OR Premature infants OR Pre-mature infant OR Pre-mature infants OR Preterm infant OR Preterm infants OR Pre-term infant OR Pre-term infants OR Premature newborn OR Premature newborns OR Pre-mature newborn OR Pre-mature newborns OR Preterm newborn OR Preterm newborns OR Pre-term newborn OR Pre-term newborns OR Premature neonate OR Premature neonates OR Pre-mature neonate OR Pre-mature neonates OR Preterm neonate OR Preterm neonates OR Pre-term neonate OR Pre-term neonates OR Premature birth OR Premature births OR Pre-mature birth OR Pre-mature births OR Preterm birth OR Preterm births OR Pre-term birth OR Pre-term births OR Neonatal prematurity OR prematuritas).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp maternal hypertension/OR (Pre-Eclampsia OR Preeclampsia OR pre-eclamptic OR preeclamptic OR preclampsia OR Proteinuria Edema Hypertension Gestosis OR Edema Proteinuria Hypertension Gestosis OR EPH Gestosis OR EPH Toxemia * OR EPH Complex).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp Placenta Insufficiency/OR (placenta insufficiency OR placental insufficiency OR placenta insufficiencies OR placental insufficiencies OR placenta deficiency OR placental deficiency OR placenta deficiencies OR placental deficiencies OR placenta failure OR placental failure).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp Macrosomia/OR (Macrosomia * OR high birth weight OR overweight infant OR overweight infants OR overweight newborn OR overweight newborns OR overweight neonate OR overweight neonates).ti,ab,kw.) OR (exp pregnancy diabetes mellitus/OR diabetes gravidarum.ti,ab,kw) |

Fourteen amino acids during pregnancy: arginine, citrulline, glutamate, glutamine, asparagine, aspartate, proline, ornithine, (iso-)leucine, valine, cysteine, methionine, and choline. The search was performed on 25 July 2018, with 10,393 records.

Table A3.

Search terms in Cochrane.

| 14 amino acids AND administration | (MeSH descriptor: [Glutamine] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage-AD, Adverse effects-AE, Deficiency-DF, Drug effects-DE, Pharmacology-PD, Physiology-PH, Therapeutic use-TU] OR MeSH descriptor: [Glutamic Acid] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Citrulline] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects-AE, Deficiency—DF, Drug effects—DE, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU] OR MeSH descriptor: [Asparagine] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects—AE, Deficiency—DF, Drug effects—DE, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU] OR MeSH descriptor: [Aspartic Acid] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects—AE, Deficiency—DF, Drug effects—DE, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU] OR MeSH descriptor: [Proline] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects—AE, Deficiency—DF, Drug effects—DE, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU] OR MeSH descriptor: [Ornithine] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects—AE, Deficiency—DF, Drug effects—DE, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU] OR MeSH descriptor: [Choline] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects—AE, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU]MeSH descriptor: [Arginine] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects—AE, Deficiency—DF, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU] OR MeSH descriptor: [Leucine] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects—AE, Deficiency—DF, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU] OR MeSH descriptor: [Isoleucine] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects—AE, Deficiency—DF, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU] OR MeSH descriptor: [Valine] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects—AE, Deficiency—DF, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU] OR MeSH descriptor: [Cysteine] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects—AE, Deficiency—DF, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU] OR MeSH descriptor: [Methionine] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Administration & dosage—AD, Adverse effects—AE, Deficiency—DF, Pharmacology—PD, Physiology—PH, Therapeutic use—TU]) OR ((MeSH descriptor: [Dietary Supplements] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Administration, Oral] explode all trees OR administration * OR administer * OR dose OR doses OR dosage OR treatment OR treated OR supplement * OR diet OR diets OR dietary OR intake OR intakes OR consumption OR consumptions OR consume OR nutraceutical * OR nutriceutical * OR therapy OR therapies:ti,ab,kw ) AND (MeSH descriptor: [Glutamic Acid] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Glutamine] this term only OR MeSH descriptor: [Citrulline] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Asparagine] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Aspartic Acid] this term only OR MeSH descriptor: [D-Aspartic Acid] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Proline] this term only OR MeSH descriptor: [Choline] this term only OR MeSH descriptor: [Ornithine] this term only OR glutamic acid OR glutamate OR MSG OR vestin OR “aminoglutaric acid” OR “aminopentanedioic acid” OR acidogen or acidoride OR acidothym OR acidulin OR aciglumin OR aciglut OR aclor OR antalka OR flanithin OR gastuloric OR glusate OR glutadox OR glutamidin OR “glutamin acid” OR “glutaminic acid” OR glutaminol OR glutan OR glutansin OR glutasin OR glutaton OR hydrionic OR hypochylin OR levoglutamate OR “levoglutamic acid” OR muriamic OR pepsdol or glutamine OR “aminoglutaramic acid” or acutil OR “adamin G” OR glumin OR glutamin OR levoglutamide OR levoglutamine OR nutrestore or citrulline OR “ureidopentanoic acid” OR ureidonorvaline OR “ureidovaleric acid” OR citrullin OR carbamylornithine OR asparagine OR asparagin OR “aminosuccinamic acid” OR “aspartic acid” OR aspartate OR Magnesiocard OR Mg-5-Longoral OR Mg 5 Longoral OR Mg5 Longoral OR panangin OR astra 2045 OR “aminosuccinic acid” OR “asparagic acid” OR asparaginate OR “asparaginic acid” OR aspartyl OR aspatofort OR “levoaspartic acid” OR proline OR prolin OR levoproline OR “pyrrolidinecarboxylic acid”OR pyrrolidine carboxylate OR ornithine OR ornithin OR “Diaminopentanoic Acid” OR “diaminovaleric acid” OR choline OR bursine OR vidine OR fagine OR trimethylammonium hydroxide OR amonita OR bilineurine OR biocholine OR biocolina OR cholin OR hepacholine OR laevocholine OR levocholine OR lipotril OR luridine OR sincaline OR urocholine:ti,ab,kw OR MeSH descriptor: [Arginine] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Leucine] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Isoleucine] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Valine] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Cysteine] explode all trees OR MeSH descriptor: [Methionine] explode all trees OR Arginine OR L-Arginine OR Leucine OR L-Leucine OR Leucin OR Isoleucine OR Isoleucin OR Alloisoleucine OR Alloisoleucin OR Valine or L-Valine OR Valsartan OR Valerate OR Cysteine OR L-Cysteine OR Cysteinate OR Acetylcysteine OR Carbocysteine OR Cysteinyldopa OR Cystine OR cystein OR cysthion OR Selenocysteine OR Methionine OR L-Methionine OR Liquimeth OR Pedameth OR formylmethionine OR Racemethionine OR Adenosylmethionine OR Selenomethionine OR Vitamin U OR acimetion OR cotameth OR lobamine OR menin OR menine OR meonine OR methiolate OR methionin OR methiotrans OR methnine OR methurine OR metione OR methidin OR neutrodor OR oradash OR urosamine OR Methyl Donor:ti,ab,kw)) |

| AND | AND |