Abstract

Background

Global health organisations advocate gender-transformative programming (which challenges gender inequalities) with men and boys to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) for all. We systematically review evidence for this approach.

Methods

We previously reported an evidence-and-gap map (http://srhr.org/masculinities/wbincome/) and systematic review of reviews of experimental intervention studies engaging men/boys in SRHR, identified through a Campbell Collaboration published protocol (https://doi.org/10.1002/CL2.203) without language restrictions between January 2007 and July 2018. Records for the current review of intervention studies were retrieved from those systematic reviews containing one or more gender-transformative intervention studies engaging men/boys. Data were extracted for intervention studies relating to each of the World Health Organization (WHO) SRHR outcomes. Promising programming characteristics, as well as underused strategies, were analysed with reference to the WHO definition of gender-transformative programming and an established behaviour change model, the COM-B model. Risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane Risk of Bias tools, RoB V.2.0 and Risk of Bias In Non-randomised Studies of Interventions.

Findings

From 509 eligible records, we synthesised 68 studies comprising 36 randomised controlled trials, n=56 417 participants, and 32 quasi-experimental studies, n=25 554 participants. Promising programming characteristics include: multicomponent activities of education, persuasion, modelling and enablement; multilevel programming that mobilises wider communities; targeting both men and women; and programmes of longer duration than three months. Six of the seven interventions evaluated more than once show efficacy. However, we identified a significant risk of bias in the overall available evidence. Important gaps in evidence relate to safe abortion and SRHR during disease outbreaks.

Conclusion

It is widely acknowledged by global organisations that the question is no longer whether to include boys and men in SRHR but how to do so in ways that promote gender equality and health for all and are scientifically rigorous. This paper provides an evidence base to take this agenda for programming and research forward.

Keywords: systematic review, public health, maternal health, health services research, child health

Key questions.

What is already known?

The Cairo and Beijing conferences, some 25 years ago, fundamentally shifted thinking on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) towards gender-transformative programming which challenges gender inequalities.

However, a recently published evidence-and-gap map of experimental research (http://srhr.org/masculinities/wbincome/) identified that male engagement in gender-transformative programming in SRHR remains relatively neglected and requires development.

What are the new findings?

-

Four promising programming characteristics of effective gender-transformative interventions with men and boys were identified.

Multicomponent activities including education, persuasion, modelling and enablement approaches that cover all elements of the COM-B model for successful behaviour change interventions: capability, motivation and opportunity.

Multilevel programming that reaches beyond target groups and mobilises the wider community to adopt egalitarian gender norms and practices.

Working with both women and men, either in mixed sex groups or separately.

Delivery of activities by trained facilitators and for a sufficient duration of time, ideally longer than three months.

The vast majority of available evidence relates to preventing violence against women and girls, and no studies were identified that focussed on two of the seven WHO-SRHR outcome domains, preventing unsafe abortion and SRHR in disease outbreaks.

Key questions.

What do the new findings imply?

This systematic review will be a springboard to advance effective male engagement in gender-transformative programming in SRHR through its identification of promising programming mechanisms, as well as underused strategies and research gaps.

This review is contributing to a global research agenda setting exercise being conducted by WHO to advance the field.

Introduction

Engaging men/boys alongside women/girls in gender-transformative programming designed to challenge gender inequality is recognised as an integral part of global strategy to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals of gender equality and health for all.1 According to the WHO definition, a gender-transformative approach ‘seeks to challenge gender inequality by transforming harmful gender norms, roles and relations through programmatic inclusion of strategies to foster progressive changes in power relationships between women and men’2 as a means to achieve health for all. However, a recent evidence-and-gap map and systematic review of reviews of all experimental evaluation studies of interventions engaging men and boys in sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) showed that only 8% of review evidence relating to the engagement of men and boys applied a gender-transformative approach to such engagement.3 4

To inform the development of gender-transformative programming with men and boys to improve SRHR, it is necessary to identify the effective characteristics of current gender-transformative programmes, to assess the quality of available evidence and to specify the gaps in current evidence. The aim of this review is to synthesise the evidence on gender-transformative programmes engaging with men and boys in the context of SRHR. The objectives are to identify the:

Programme characteristics of gender-transformative interventions with men and boys to improve SRHR, including those programme mechanisms that have shown efficacy in more than one intervention evaluation;

Methodological quality of studies of gender-transformative male engagement programmes;

Gaps in evidence on gender-transformative male engagement programming.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

First, an evidence-and-gap map and systematic review of reviews was conducted and reported elsewhere to identify all systematic reviews of programmes engaging men and boys in SRHR (n=462), and to specifically identify a subset of those reviews which contained at least one explicitly gender-transformative programme evaluation study engaging men and boys to improve SRHR (n=39).3 4 Systematic reviews published between 1 January 2007 and 31 July 2018 were retrieved for the original review of reviews through a Campbell Collaboration registered and published protocol,3 detailing the search strategy with no language restrictions (see online supplemental file 1).

bmjgh-2020-002997supp001.pdf (127.2KB, pdf)

Second, using the identified subset of 39 systematic reviews that included at least one gender-transformative programme evaluation study engaging men and boys in SRHR, the content and reference lists of each of these reviews was searched to retrieve the original intervention studies. Inclusion criteria were experimental evaluation studies and associated process evaluations of interventions using a gender-transformative approach engaging men and boys to improve SRHR (see online supplemental file 2 for reference list of included studies). Based on the WHO definition, gender-transformative programmes were specified as those that included ways to transform harmful gender norms, or gender practices, or gender inequality, and/or addressed the causes of gender-based inequities within the programmes.2

bmjgh-2020-002997supp002.pdf (81.9KB, pdf)

Two authors conducted double-blind independent screening of 10% of the full-text articles (ER-M, KG), and discussion of categorisation variance with a third author (ML). Thereafter, the remaining articles were divided equally and each author continued to screen full-texts independently. Data extraction forms (see online supplemental file 3) were designed based on Cochrane guidance on evidence synthesis and extracted using DistillerSR software.5

bmjgh-2020-002997supp003.pdf (291.3KB, pdf)

Analysis and reporting

The extracted studies were reviewed in accordance with structured assessment criteria with respect to intervention characteristics, risk of bias/methodological quality, categorisation of outcomes and identification of gaps in evidence. Four researchers working in pairs (ER-M, KG; ML, ÁA) coded the studies independently. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2009 checklist6 is provided to summarise reporting standards of this review (online supplemental file 4).

bmjgh-2020-002997supp004.pdf (193.3KB, pdf)

Programme characteristics

Programme characteristics were first categorised according to programme approach (delivery setting and delivery method), second, gender-transformative components and third, behaviour change mechanisms. Analysis of all programme components was conducted for all studies prior to conducting a deeper analysis of identified effective programmes evaluated more than once.

Gender-transformative components of each programme were categorised according to core elements in the operational definition published by WHO2 : (i) transforming harmful gender norms or practices or gender-based inequalities at an individual or group level and (ii) transforming unequal gender norms, practices or gender-based inequalities through a more structural dimension and targeting underlying causes (ie, through implementing changes that impact the social norms, physical or regulatory environments in communities, institutions or at the policy level).

Behaviour change mechanisms applied in the included interventions were matched to the behaviour change wheel (BCW) by Michie et al.7 The BCW distinguishes two layers of behaviour change mechanisms: intervention functions and policy categories. The intervention functions are: education, persuasion, incentivisation, coercion, training, restriction, environmental restructuring, modelling and enablement. The policy-level categories of the model are: large-scale communication/marketing, guidelines, social planning, legislation, service provision, regulation and fiscal measures. At the centre of the model, the BCW identifies the sources of the behaviour that could prove fruitful targets for intervention change-mechanisms known as the COM-B model of behaviour change: ‘capability’, ‘opportunity’, ‘motivation’ and ‘behaviour’. An image of the BCW may be viewed here (http://www.behaviourchangewheel.com/).8

Risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB V.2.0)9 for randomised controlled trials and an adaptation of the Risk of Bias In Non-randomised Studies of Interventions10 tool for quasi-experimental studies(online supplemental file 5).

bmjgh-2020-002997supp005.pdf (445.7KB, pdf)

Categorisation of outcomes and identification of gaps in SRHR programming

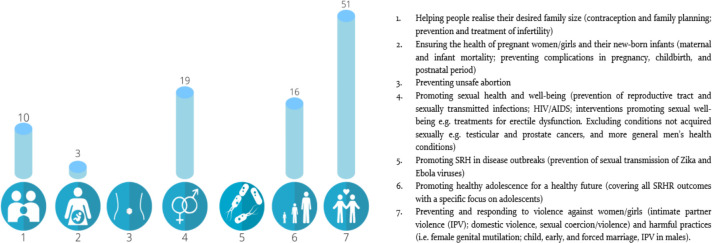

Intervention studies were categorised according to SRHR outcomes of the WHO Reproductive Health Strategy11:

Helping people realise their desired family size

Ensuring the health of pregnant women/girls and their new-born infants.

Preventing unsafe abortion.

Promoting sexual health and well-being.

Promoting sexual and reproductive health (SRH) in disease outbreaks.

Promoting healthy adolescence for a healthy future.

Preventing and responding to violence against women/girls.

The measures used to study the SRHR outcomes were categorised as: attitudinal, behavioural and biological. The first two categories were based on self-reported attitudes and behaviours.

Patient and public involvement

Generating improved programming and evaluation requires consultation and collaboration with experts working on gender equality programming in public health.12 The impetus for this systematic review came from advice received from the Gender and Rights Advisory Panel of the WHO’s Department of Reproductive Health and Research, which includes the UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction. The Gender and Rights Advisory Panel provides critical advice on shaping the department’s portfolio on gender equality and SRHR, including on engaging men and boys. Preliminary conclusions of this review were discussed with a wider WHO convened stakeholder group as the first stage of a global research priorities setting exercise for this field.

Results

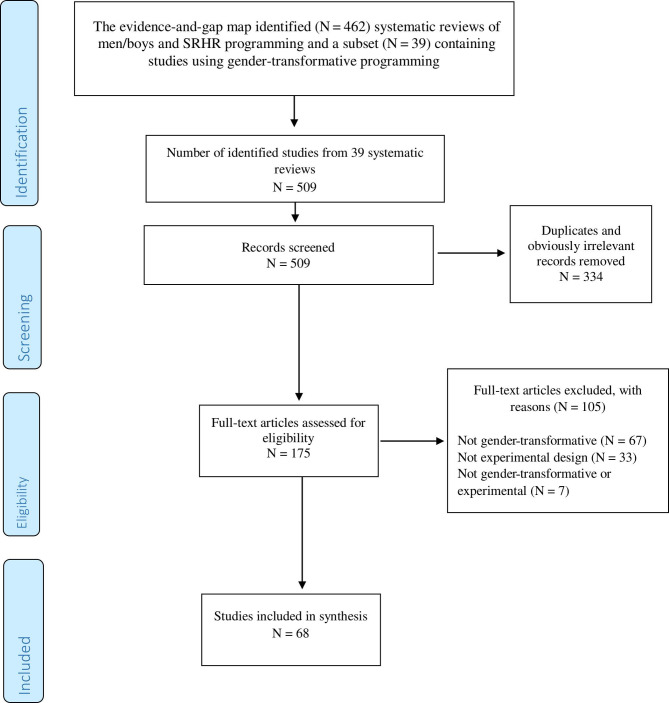

The evidence-and-gap map (http://srhr.org/masculinities/wbincome/) contained 462 systematic reviews, of which 39 included studies which used a gender-transformative approach.3 4 The reference lists of these 39 reviews contained 509 total records (intervention studies), of which 334 were identified as duplicates and removed. The remaining studies were evaluated according to inclusion/exclusion criteria to produce a final collection of 68 studies for review. The flow of search and refinement is displayed in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow. SRHR, sexual and reproductive health and rights.

The 68 studies comprised 36 RCTs (n=56 417 participants) and 32 quasi-experimental studies (n=25 554 participants). The number of studies conducted in low-income countries and middle-income countries (LMICs) combined is roughly equal to those conducted in high-income countries (HIC) (figure 2). This is owing to a shift over time to a growing number of studies conducted in LMICs. See table 1 for list of included studies.

Figure 2.

Country of origin and World Bank Classification for included intervention studies.

Table 1.

Included study information

| Author | Year | World Bank category | Country | Funder | Sex | Total participants (n=) | Risk of bias (RCT or QE) | |

| Intervention | Study | |||||||

| Abramsky | 2014 | LIC | Uganda | Irish Aid; Sigrid Rausing Trust; 3ie; AusAID; Stephen Lewis Foundation; American Jewish World Service; HIVOS; NoVo Foundation | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 1583; Endline: 2532 |

Some concerns (RCT) |

| Abramsky | 2016 | LIC | Uganda | See above | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 1583; Endline: 2532 |

Some concerns (RCT) |

| Achyut | 2011 | MIC | India | John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; Nike Foundation | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 2896; Follow-up: 203; Endline: 754 |

Serious (QE) |

| Ara | 2010 | LIC | Bangladesh | BRAC & international partners | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 1534; Endline: 797 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Ashburn | 2017 | LIC | Uganda | USAID; Oak Foundation | M (small amount of female partner involvement) | M | Baseline: 435; Endline: 400 |

Serious (QE) |

| Avery-Leaf | 1997 | HIC | USA | NIMH | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 193; Endline: 193 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Baiocchi | 2017 | MIC | Kenya | Ujamaa-Africa | M+F | F | Baseline: 5686; Endline: 6106 |

High (RCT) |

| Bartel | 2010 | MIC | India | Ford Foundation | M+F | F | Baseline: 663; Endline: 668 |

Serious (QE) |

| CAREInternational | 2012 | MIC, HIC | Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Croatia | CARE International North West Balkans | M | M | >100 | Serious (QE) |

| Chamroonsawasdi | 2010 | MIC | Thailand | WHO | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 530; Endline: 530 |

Serious (QE) |

| Chege | 2004 | LIC, MIC | Ethiopia, Kenya | USAID | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 2259; Endline: 2240 |

Serious (QE) |

| Cowan | 2010 | MIC | Zimbabwe | NIMH; DfID Zimbabwe | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 6791; Endline: 4684 |

High (RCT) |

| Daniel | 2008 | MIC | India | David and Lucile Packard Foundation | M+F | F | Baseline: 1995; Endline: 2080 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Das | 2012 | MIC | India | NIKE Foundation | M | M | 610 | Serious (QE) |

| Davis | 2000 | HIC | USA | US DOJ | M | M+F | Baseline: 376; T2: 150*; Endline: 83* |

High (RCT) |

| Davis | 2002 | HIC | USA | Unspecified | M | M | Baseline: 89; T2: 90; Endline: 89 |

High (RCT) |

| Diop | 2004 | MIC | Senegal | USAID; Population Council | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 2623; Endline: 2397 |

Serious (QE) |

| El-Bassel | 2005 | HIC | USA | NIMH | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 298; Endline: 166 |

High (RCT) |

| Erulkar | 2011 | LIC | Ethiopia | USAID/PEPFAR | M | M | 545 | Serious (QE) |

| Exner | 2009 | MIC | Nigeria | NICHD; NIMH; HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies | M | M | Baseline: 281; Endline: 185 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Fay | 2006 | HIC | USA | Unspecified | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 154; Endline: 154 |

High (RCT) |

| Feder | 2000 | HIC | USA | US DOJ | M | M+F | Baseline: 321; Endline: 203 |

High (RCT) |

| Feder | 2002 | HIC | USA | US NIJ | M | M+F | Baseline: 520; Endline: 325 |

High (RCT) |

| Feder | 2004 | HIC | USA | US DOJ | M | M+F | Baseline: 520; T2: 325; Endline: 87 |

High (RCT) |

| Foshee | 1998 | HIC | USA | CDC | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 1886; Endline: 1700 |

High (RCT) |

| Foshee | 2000 | HIC | USA | CDC | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 1886; T2: 1700; Endline: 1603 |

High (RCT) |

| Foshee | 2004 | HIC | USA | CDC | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 1886; T2: 1700; T3: 1603; Endline: 460 |

High (RCT) |

| Foshee | 2005 | HIC | USA | CDC | M+F | M+F | 1566 | High (RCT) |

| Foubert | 1997 | HIC | USA | Unspecified | M | M | Baseline: 105; Endline: 77 |

Serious (QE) |

| Fuertes | 2012 | HIC | Spain | Ministry of Science, Technology, Knowledge and Innovation, Chile | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 169; T2: 169; Endline: 169 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Gidycz | 2011 | HIC | USA | CDC | M | M | Baseline: 635; T2: 529; Endline: 494 |

Some concerns (RCT) |

| Gordon | 2003 | HIC | USA | Unspecified | M | M | 248 | Serious (QE) |

| Gupta | 2013 | MIC | Côte d’Ivoire | World Bank’s SPF; Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS; NIMH | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 981; Endline: 934 |

Some concerns (RCT) |

| Harrell | 1991 | HIC | USA | US State Justice Institute | M | M | Baseline: 237; Endline: 193 |

Serious (QE) |

| Hillenbrand-Gunn | 2010 | HIC | USA | Missouri Department of Health and Senior Service; CDC; NCIPC | M+F | M+F | 212 | Serious (QE) |

| Hossain | 2014 | MIC | Côte d’Ivoire | Novo Foundation; Sigrid Rausing Trust; UK ESRC | M | M+F | Baseline: 578; Endline: 548 |

High (RCT) |

| Instituto Promundo | 2012 | MIC | Brazil, India, Chile | Instituto Promundo; UNTF | India: M+F; Brazil and Chile: M | Not reported |

Brazil Pretest: 210; Post-test: 180 Chile Pretest: 510; Post-test: 303 India Pretest: 370; Midline: 267; Post-test: 258 |

Serious (QE) |

| James | 2006 | MIC | South Africa | Horizons Project (USAID) | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 1141; T2: 844; Endline: 768 |

High (RCT) |

| Jewkes | 2008 | MIC | South Africa | NIMH | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 2776; T2: 2144; Endline: 2069 |

High (RCT) |

| Kalichman | 2009 | MIC | South Africa | NIMH | M | M | Baseline: 475; T2: 452; T3: 455; Endline: 432 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Keller | 2017 | MIC | Kenya | Ujamaa-Africa; No Means No Worldwide | M | M | Baseline: 1543; Endline: 1325 |

Serious (QE) |

| Kyegombe | 2014 | LIC | Uganda | Irish Aid; Sigrid Rausing Trust; 3ie; UKAID; Stephen Lewis Foundation; HIVos; NoVo Foundation | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 1583; Endline: 2532 |

High (RCT) |

| Kyegombe | 2015 | LIC | Uganda | See above | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 1583; Endline: 2530 |

High (RCT) |

| Labriola | 2005 | HIC | USA | US NIJ | M | M | Baseline: 211; Endline: 209 |

High (RCT) |

| Lin | 2009 | HIC | Taiwan | Department of Health (China) | M | M | Baseline: 340; Endline: 301 |

Serious (QE) |

| Lundgren | 2013 | LIC | Nepal | USAID | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 603; Endline: 603 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Macgowan | 1997 | HIC | USA | National Council of Jewish Women | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 740; Endline: 440 |

Serious (QE) |

| Maxwell | 2004 | HIC | USA | NIJ | M | M | 367 | High (RCT) |

| Miller | 2012 | HIC | USA | CDC | M | M | Baseline: 2006; Endline: 1798 |

Some concerns (RCT) |

| Miller | 2014 | MIC | India | Nike Foundation; US NIH; US HRSA | M | M | Baseline: 663; Endline: 309 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Pulerwitz | 2006 | MIC | Brazil | Horizons Program (USAID); REPSSI | M | M | Baseline: 780; T2: 622; Endline: 407 |

Serious (QE) |

| Pulerwitz | 2010 | LIC | Ethiopia | PEPFAR | M | M | Baseline: 729; Endline: 645 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Pulerwitz | 2015 | LIC | Ethiopia | PEPFAR | M | M | Baseline: 729; Endline: 645 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Rhodes | 2011 | HIC | USA | NIMH | M | M | Baseline: 142; Endline: 139 |

Some concerns (RCT) |

| Salazar | 2006 | HIC | USA | Georgia State University | M | M | Baseline: 47; Endline: 36 |

High (RCT) |

| Salazar | 2014 | HIC | USA | NCIPC; CDC | M | M | Baseline: 743; T2: 451; Endline: 215 |

Some concerns (RCT) |

| Saunders | 1996 | HIC | USA | CDC; University of Michigan | M | M+F | Baseline: 417; Follow-up: 243 |

High (RCT) |

| Schuler | 2012 | LIC | Tanzania | C-Change Project & international partners (USAID) | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 764; Endline: 369 |

High (RCT) |

| Schuler | 2012 | MIC | Guatemala | C-Change Project & international partners (USAID) | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 1122; Endline: 603 |

High (RCT) |

| Schwarz | 2004 | HIC | USA | Unspecified | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 65; Endline: 58 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Shattuck | 2011 | LIC | Malawi | Family Health International; USAID | M | M | Baseline: 397; Endline: 289 |

Some concerns (RCT) |

| Taylor | 2012 | MIC | South Africa | SANPAD | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 816; Endline: 679 |

High (RCT) |

| Taylor | 2001 | HIC | USA | US NIJ | M | M | Baseline: 376; T2: 171, Endline: 186 |

High (RCT) |

| Taylor | 2009 | HIC | USA | US NIJ | M | M | 629 | High (RCT) |

| Verma | 2008 | MIC | India | PEPFAR | M+F | M | Baseline: 1915; Endline: 1138 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Wagman | 2015 | LIC | Uganda | Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; US NIH; WHO; PEPFAR; Fogarty International Center | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 11 448; T2: 7842; Endline: 6526 |

High (RCT) |

| Weisz | 2001 | HIC | USA | Michigan Community Health Department | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 66; T2 & endline: varied by measure: Knowledge=26 Attitudes=29 Perpetration=23 Victimisation=20 |

Moderate (QE) |

| Wolfe | 2003 | HIC | Canada | Ontario Mental Health Foundation; NHRDP (Health Canada); SSHRC (Canada) | M+F | M+F | Baseline: 191; Endline: 158 |

Moderate (QE) |

*Values imputed from percentages reported by study authors.

F, female; HIC, high-income country; LIC, low-income country; M, male; MIC, middle-income country; QE, quasi-experimental study; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Key finding 1: Community mobilisation and education is the most common type of male engagement gender-transformative programmatic approach

The most common approach was Community Mobilisation and Education Programmes (n=17 studies or 25%), followed by School or after-school Education Programmes (n=15, 22%) followed by Court-mandated Batterers Programmes (n=12, 18%).

The remaining types of programming approaches included in studies were Community Education Programmes (n=9, 13%); College/University based Educational Programmes (n=5,7%); Community Health Outreach Programmes (n=4, 6%); Community Health Centre health/parenting Promotion Programmes (n=3. 5%) and Sports-based Educational Outreach Programmes (n=3, 5%).

Interventions were slightly more likely to be delivered to both women and men, either separately as single sex groups or together as mixed sex groups, than to men only. Interventions were equally likely to be delivered by trained professionals/facilitators or by peers with overlap of delivery agents throughout many interventions. The modal intervention dosage period was under three months. Only in nine studies were interventions delivered for longer than 12 months and these were largely Community Mobilisation and Education Programmes (table 2).

Table 2.

Programme characteristics by programming approach

| Programme characteristics | Programme approach | ||||||||

| CMEP | CEP | SEP | UEP | SPOP | CHOP | CHP | CBP | Total | |

| Gender-transformative characteristics | |||||||||

| Transform harmful gender norms/practices at individual/group level | 17 | 9 | 15 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 68 |

| Transform unequal gender relations through more structural dimension | 12 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Programme behaviour-change components | |||||||||

| Education | 17 | 8 | 15 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 65 |

| Persuasion | 16 | 7 | 12 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 57 |

| Incentivisation | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| Coercion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Training | 13 | 8 | 14 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 55 |

| Restriction | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Environmental restructuring | 5 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 16 |

| Modelling | 10 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 37 |

| Enablement (beyond education and beyond environmental restructuring) | 13 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 34 |

| Policy components | |||||||||

| Community marketing | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Target level | |||||||||

| Individual | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 10 |

| Couple | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Group | 12 | 13 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 59 |

| Community | 12 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Delivered by | |||||||||

| Professional | 9 | 3 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 29 |

| Facilitator | 8 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 26 |

| Mentor | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Peer | 8 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 20 |

| Received by | |||||||||

| Males only | 5 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 12 | 32 |

| Males and females | 13 | 5 | 14 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 37 |

| Delivery setting | |||||||||

| Home | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Community | 17 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 11 | 46 |

| Healthcare | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| Educational | 2 | 1 | 15 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| Dosage | |||||||||

| <3 months | 3 | 4 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 32 |

| 3–6 months | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 18 |

| 6–12 months | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 10 |

| >12 months | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

CBP, Court-mandated Batterers Programme; CEP, Community Education Programme; CHOP, Community Health Outreach Programme; CHP, Community Health Centre health/parenting Promotion Programme; CMEP, Community Mobilisation and Education Programme; SEP, School or after-school based Educational Programme; SPOP, Sports-based educational Outreach Programme; UEP, College/University based Educational Programme.

Key finding 2: Few gender-transformative interventions addressed unequal power relations at the structural level

All of the intervention studies intentionally focused on transforming harmful gender norms, practices or inequalities either among individuals or groups (n=68). A smaller number (n=17) of interventions, all of which were either Community Mobilisation and Education Programmes; School or after-school based Educational Programmes, or Community Health Outreach Programmes included ways of transforming unequal gender relations at the structural level. Interventions were placed in this category when they extended their reach beyond the individual or group context and targeted the intervention to impacting the social norms, physical or regulatory environments of the wider community, institutions or at the policy level.

The predominance of gender-transformative interventions targeting the individual or group level was further triangulated by categorising interventions according to the COM-B model behaviour change components.7 Viewed through this model, only five interventions sought to make changes at the policy level and that too was limited to one strategy, that of large-scale social media and print communication campaigns designed to reach a larger population. Untested in the included studies were other policy level programming characteristics of the BCW such as guidelines, social planning, legislation, service provision, regulation and fiscal measures. Examples of programming mechanisms are presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Definition and examples of Gender-transformative programming mechanisms

| Behaviour change mechanisms | Behaviour change wheel definition | Gender-transformative examples in intervention studies |

| Education | Increasing knowledge or understanding | Information on concepts of sexual freedom, coercion and consent, possible consequences, different contexts, situations and interactions. |

| Persuasion | Using communication to induce positive or negative feelings or stimulate action | Gender Dialogue Groups for women and male partner (or male family member) brought together to reflect on financial decisions and goals and sought to address household gender inequities; underscoring all sessions were messages on importance of non-violence in the home, respect and communication between men and women and value of women in the household. |

| Incentivisation | Creating expectation of reward | Sports, particularly weekly football matches, used as venue for dialogue and opportunity to convey gender equality workshop themes. |

| Coercion | Creating expectation of punishment or cost | Court-ordered requirements for attendance/participation, limitations on confidentiality, protocol around partner safety. Mandatory fee-paying. |

| Training | Imparting skills | Interactive teaching, small group discussion, scripting behaviour through vignettes and role plays, proverbs, songs, stories and games—to engage and facilitate skills development challenging gender-based violence (eg, norms that challenge legally permissible wife beating). Emphasised communication, assertiveness and negotiation skills requisite for practicing safer sex. |

| Restriction | Using rules to reduce the opportunity to engage in the target behaviour | Not available (N/A). Suggested potential example: curfew to prevent underage drinking associated with unintended teenage pregnancy. |

| Environmental restructuring | Changing the physical or social context | Community activities to enhance availability of dating violence services from which adolescents can seek help. |

| Modelling | Providing an example for people to aspire to or imitate | Programme peers or leaders, eg, sports coaches, challenging harmful normative attitudes and behaviours within community such as acceptability of violence against women and encourage positive male behaviours, such as positive parenting, that participants could identify with and emulate in their own lives. Public declaration of community leaders from within communities for abandonment of Female genital cutting. |

| Enablement | Increasing means/reducing barriers to increase capability or opportunity | Postintervention ‘check-in’ sessions with programme facilitators to review and support personal risk reduction goals in prevention of sexual/dating violence. |

| Policies | ||

| Communication/marketing | Using print, electronic, telephonic or broadcast media to convey messages to large population groups | Social marketing campaign targeted to about 3000 young people called ‘Budi muško’ or ‘Be a man’. The overall theme of campaign was to challenge rigid norms of masculinity. |

| Guidelines | Creating documents that recommend or mandate practice. This includes all changes to service provision | N/A. Suggested potential example: national-level support for inclusion of men in antenatal care and women’s health needs in preparation for the birth of an infant. |

| Fiscal | Using the tax system to reduce or increase the financial cost | N/A. Suggested potential example: tax incentives for businesses offering paternity leave. |

| Regulation | Establishing rules or principles of behaviour or practice | N/A. Suggested potential example: national move to mandatory relationship and sexuality education in secondary schools. |

| Legislation | Making or changing laws | N/A. Suggested potential example: national government level legal prohibition of child marriage. |

| Environmental/social planning | Designing and/or controlling the physical or social environment | N/A. Suggested potential example: federal government level provision of sufficient abortion clinics in every state to ensure nationwide access. |

| Service provision | Delivering a service | N/A. Suggested potential example: government level initiative to deliver community youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services. |

Key finding 3: A majority of studies showed either positive or mixed efficacy in relation to behavioural and attitudinal outcomes

A majority of the studies (61/68) showed some evidence of efficacy in relation to behavioural and attitudinal outcomes. Specifically, 38/61 showed positive effect on study outcomes and 23/61 showed mixed effects (ie, showed positive effects on some outcomes, but nil effect on others). No study found a negative effect of intervention on any of the outcomes of interest (online supplemental file 6).

bmjgh-2020-002997supp006.pdf (119.3KB, pdf)

Seven programmes were replicated, some with adaptation to context, and evaluated more than once (table 4). Based on this smaller group of interventions studied through experimental designs more than once, only the Duluth Model demonstrated no evidence of effect in either behavioural or attitudinal SRHR outcomes. The Duluth Model programme targeted individual men perpetrating violence towards their intimate partners and was delivered in a custodial setting as a court-mandated programme for convicted offenders. Literature on working with men on violence against women prevention has shown that it is more challenging to work with convicted offenders of domestic violence because many of them have multiple and long histories of trauma and problem behaviours including involvement in other crimes, alcohol misuse, substance use or mental health conditions.13

Table 4.

Efficacy of named interventions evaluated more than once

| Intervention | Number RCTs | Number QE | Intervention studies | Risk of bias | Countries | WB country income | SRHR domain 1–7† | Outcome level/conclusions (+: positive effect; −: nil effect, −: some positive/nil effects) |

|||

| Behavioural | Attitudinal | Biological | Overall | ||||||||

| C-Change | 2 | 0 | 152 Schuler (2012)* | High | Tanzania | LIC | 1 | – | + | +- | |

| 153 Schuler (2012)* | High | Guatemala | MIC | 1 | – | + | |||||

| Coaching Boys into Men | 1 | 1 | 121 Miller (2012) | Some concerns | USA | HIC | 6 | +− | +− | +− | |

| 122 Miller (2014)* | Moderate | India | MIC | 7 | +− | +− | |||||

| 35 Das (2012)* | Serious | India | MIC | 7 | +− | + | |||||

| Duluth Model | 6 | 2 | 56 Feder (2000) | High | USA | HIC | 7 | - | - | – | |

| 57 Feder (2002) | High | - | - | ||||||||

| 58 Feder (2004) | High | - | - | ||||||||

| 110 Labriola (2005) | High | USA | HIC | 7 | – | ||||||

| 36 Davis (2000)* | High | USA | HIC | 7 | +− | ||||||

| 164 Taylor (2009)* | High | USA | HIC | 7 | +− | ||||||

| 119 Maxwell (2004)* | High | USA | HIC | 7 | + | ||||||

| 163 Taylor (2001)* | High | USA | HIC | 7 | +− | ||||||

| 75 Harrel (1991)* | Serious | USA | HIC | 7 | – | – | |||||

| 112 Lin (2009)* | Serious | Nepal | LIC | 7 | +− | ||||||

| Male Norms Initiative | 0 | 2 | 141 Pulerwitz (2006) | Serious | Brazil | MIC | 4 to 7 | + | + | + | + |

| 142 Pulerwitz (2010) | Moderate | USA | HIC | 4 to 7 | + | + | |||||

| Program H | 0 | 4 | 141 Pulerwitz (2006)* | Serious | Brazil | MIC | 3 | + | + | + | + |

| 142 Pulerwitz (2010)* | Serious | Ethiopia | LIC | 4 to 7 | + | + | |||||

| 169 Verma (2008)* | Moderate | India | MIC | 3 | + | + | |||||

| 85 Instituto Promundo (2012)* | Serious | Brazil, India, Chile | MIC, HIC | 7 | + | + | |||||

| Safe Dates | 2 | 0 | 60 Foshee (1998) | High | USA | HIC | 6 | + | + | +− | +− |

| 61 Foshee (2000) | High | – | +− | ||||||||

| 63 Foshee (2005) | High | + | + | ||||||||

| 62 Foshee (2004)* | High | USA | HIC | 6 | – | ||||||

| Stepping Stones | 3 | 1 | 91 Jewkes (2008) | High | South Africa | MIC | 4 to 7 | +− | +− | +− | |

| 85 Instituto Promundo (2012)* | Serious | Brazil, India, Chile | MIC, HIC | 7 | + | + | |||||

| 152 Schuler (2012)* | High | Tanzania | LIC | 1 | – | + | |||||

| 153 Schuler (2012)* | High | Guatemala | MIC | 1 | – | + | |||||

*Study/Paper examines adaptation or element of intervention.

†WHO SRHR domains: (1) helping people realise their desired family size; (2) ensuring the health of pregnant women/girls and their new-born infants; (3) preventing unsafe abortion; (4) promoting sexual health and well-being; (5) promoting sexual and reproductive health in disease outbreaks; (6) promoting healthy adolescence for a healthy future; (7) preventing and responding to violence against women/girls.

HIC, high-income country; LIC, low-income country; MIC, middle-income country; QE, quasi-experimental study; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SRHR, sexual and reproductive health and rights; WB, World Bank.

Only three of the seven studies evaluated biological outcomes. In the case of Program H and Male Norms Initiative, biological outcomes were assessed through self-reported sexually transmitted infection (STI) symptoms, which reduces confidence in demonstrating efficacy. The Stepping Stones RCT, the only study in this analysis to use biomarkers, showed the intervention reduced rates of herpes simplex virus 2 among men but did not show a reduction on the primary outcome of HIV.

Key finding 4: Programme characteristics consistently employed across effective interventions evaluated more than once were: multicomponent activities; multilevel programming; working with both women and men and trained facilitation of interventions of at least three-month duration

Programme characteristics consistently employed across effective interventions evaluated more than once were: first, multicomponent activities and specifically: education, persuasion, modelling and enablement. These programming mechanisms span the three elements of the COM-B model for effective behaviour change interventions: capability, motivation and opportunity.7 Second, there was most evidence for Community Mobilisation and Education Pogrammes that included multilevel programming which sought to address gender inequality from a more structural dimension through implementing changes that impact the social norms, physical or regulatory environments in communities, institutions or at the policy level. However, just as when all included studies are examined, only a limited range of policy or structural level programming mechanisms has been tested within this subset of effective programmes evaluated more than once. To date, based on programme descriptions in studies, only the application of ‘wider community and mass media campaigns’ has been tested.

Successful programmes also tended to be delivered to both women and men either in separate or mixed sex groupings. Further delivery characteristics associated with positive effects were programmes implemented in community settings and delivered by professionals or trained facilitators, including peer mentors and a programme duration of longer than three months (three months was identified as the modal dosage intervention time across all interventions). Programmes implemented effectively in a different country first underwent significant cultural adaptation prior to evaluation in the new context.

Key finding 5: All included studies had moderate to high risk of bias and hence, the quality of evidence needs to be improved

All 32 quasi-experimental studies were assessed to have serious/moderate risk of bias (serious n=14; moderate n=18) and all 36 RCTs were assessed to have high risk of bias (n=28) or some concerns (n=8). The risk of bias among studies was typically related to participant selection, randomisation, deviations from the intended intervention, missing data and overall reporting standards (online supplemental file 7).

bmjgh-2020-002997supp007.pdf (84.4KB, pdf)

In many cases, however, the resultant risk of bias was due to large-scale challenges encountered in the implementation environment during intervention or study enactment. For example, the implementation of two interventions, SASA! in Uganda and Regai dzive Shiri in Zimbabwe was adversely affected by political and economic unrest in the study locations, causing significant population out-migration.14 15 Hence, there were challenges with programme implementation as well as participant follow-up and modifications had to be made, for example, intervention delivery in communities rather than schools.13 Hence, despite the high risk of bias identified across studies as a whole in this review, potentially promising conclusions from implementing well-planned interventions in complex environments should not be ignored.16

Key finding 6: There are significant gaps in the evidence with respect to SRHR in disease outbreaks and facilitating women’s access to safe abortion

There were no gender-transformative male engagement programmes that addressed prevention of unsafe abortion, and sexual and reproductive health in disease outbreaks (eg, Zika and Ebola). As shown in figure 3, the majority of studies addressed the prevention of violence against women and girls (n=51). The next most frequently intervened SRHR domains were promotion of sexual health and well-being (n=16), healthy adolescence (n=16), helping people realise their desired family size (n=10) and ensuring the health of pregnant women (n=3). Over half of the intervention studies (n=38) focused on a single SRHR topic or domain. The remaining intervention studies addressed multiple SRHR domains concurrently.

Figure 3.

WHO sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) domains addressed by interventions in review.

There were also gaps in gender-transformative male engagement programmes on important areas within SRHR domains. Within the desired family size domain, no interventions were identified to address infertility. nor were there interventions to enhance desired family size in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) relationships. Within the domain of health of pregnant women, while all three studies included involving men in preparedness for birth, only one addressed male involvement in supporting women to breast feed. In the promoting sexual health and well-being domain, the predominant focus was on preventing and treating STIs, including HIV. While some studies (n=3) focused on wider sexual health and well-being through factors such as communication and shared decision-making, none addressed sexual dysfunction. In the healthy adolescence domain, the focus was predominantly on preventing intimate partner violence (IPV), and few addressed preventing adolescent pregnancy (n=1), STIs (n=3) or improving sexual decision-making (n=1). Finally, within the preventing violence against women and girls domain, the focus was on IPV, with fewer studies addressing harmful practices such as female genital mutilation (n=2); child, early and forced marriage (n=2) or IPV on males (n=3) (online supplemental table 8).

bmjgh-2020-002997supp008.pdf (321.9KB, pdf)

Discussion

While other studies have addressed specific SRHR topics such as preventing violence against women or HIV17 18 or specifically focused on adolescents,19 20 this is the first systematic review of the evaluation evidence on what has been done programmatically to engage boys and men in gender-transformative programming across all WHO SRHR outcomes. This is important because there is now greater evidence for implementing multitargeted programmes, rather than single issue programmes.21

The review identifies specific positive programming mechanisms of gender-transformative interventions to guide others working on male engagement programmes. Given the increasing policy, donor and programmatic investments in engaging men and boys in gender-transformative approaches, it is vital that these are driven by a methodologically robust understanding and framework of gender-transformative programming and with the same evaluation rigour that is applied to other public health programming and policy making.

The synthesis offers the following appraisal of the available evidence and gaps. First, since the first literature review conducted in this field in 200722 and up to July 2018, we identified only 68 experimental evaluations engaging men and boys in gender-transformative interventions. The vast majority of these relates to preventing violence against women and girls (75% percent) and only seven interventions have been evaluated more than once.

Second, analysis of programming characteristics highlights that the most common type of gender-transformative programmatic intervention approach was Community Mobilisation and Education Programmes. Promising programming mechanisms of gender-transformative interventions (based on an analysis of effective interventions evaluated more than once) include: (I) multicomponent activities of education, persuasion, modelling and enablement approaches that cover all elements of the COM-B model for successful behaviour change interventions: capability, motivation and opportunity; (II) multilevel programming that reaches beyond the individual or groups and mobilises the wider community to adopt egalitarian gender norms and practices (ie, includes gender-transformative component at the structural level); (III) working with both women and men either in mixed sex groups or separately and (IV) delivery of activities by trained facilitators and for a sufficient duration of time to allow for diffusion and sustaining of change to occur.

Third, there is evidence of efficacy in relation to gender attitudes and some SRHR behavioural outcomes, but not primary biological outcomes when assessed through biomarker measurement. The evidence on attitudes and behaviours should be regarded as promising rather than firm, given the observed significant risk of bias in the available evidence. Consistent with guidelines for evaluating the evidence of complex interventions, these promising conclusions should appropriately inform the evolution of more robust studies, including studies that clearly distinguish apriori primary and secondary outcomes.

Finally, a number of gaps in evidence have been identified most notably in areas of gender-transformative programming with men to support women’s access to safe abortion, SRHR during disease outbreaks, addressing infertility, men’s engagement in supporting women during the postpartum period and in relation to breast feeding, sexual well-being and adolescent pregnancy. To advance the field, a particular contribution would be greater cooperation between researchers and programmers in designing dynamic logic modelling of interventions over time and tracing descriptions of programming, for example, by using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication guidelines.23 This would inform richer and more rigorous evaluations of what programme mechanisms are impactful and why and for whom. The review also highlights the limitations of gender-transformative programming mechanisms that are limited to bringing behaviour change through targeting individuals or small groups. It highlights the need to build on these programmes to include gender-transformative programming mechanisms at the structural level—that is either at the community, institutional or societal level. Very few interventions in this review went beyond the small group and community level to include larger structural change, which literature in the field of gender-transformative programming overall shows is critical to bringing change in gender norms and power relations at scale and to sustain this change.19 24–28 Furthermore, our review highlights that the evaluation science on male engagement in gender-transformative interventions is heavily weighted towards heteronormative over LGBTQ relationships. Our recommendation for future research is to consider programming with males that also addresses homophobic aspects of masculinity and promotes SRHR for LGBTQ communities, either by using or expanding the WHO SRHR outcome domains.

Conclusions drawn from the evidence should be considered in light of review limitations. As data were derived from a first stage systematic review of reviews, evidence that was not included in existing systematic reviews and those in systematic reviews published after July 2018 have not been included. The published extensive search strategy3 conducted without language restrictions included nine data bases and supplementary internet searches to cover both scientific and grey literature, including Global Health Library, but did not include foreign-language databases. The focus on experimental and quasi-experimental studies and exclusion of cross-sectional and solely qualitative studies, while providing a more robust pool of data, can overlook important other information. Qualitative research in particular would yield important insights into users’ experiences of gender-transformative programming. The inclusion of qualitative evaluations alongside experimental designs in systematic reviews is likely more feasible in systematic reviews that are not covering the whole spectrum of SRHR outcomes and the authors intend to join others in taking up this challenge in further systematic reviews. Meta-analysis of all included studies was not possible owing to heterogeneity in outcomes, outcome measures and research designs.

Conclusion

This review shows that gender-transformative interventions engaging men and boys in SRHR are promising and warrant further rigorous development in terms of conceptualisation, design and evaluation. In particular, this review draws out the primary programming mechanisms or ‘active ingredients’ at play in successfully engaging men in challenging gender inequalities, male privilege and harmful or restrictive masculinities to improve SRHR for all. In addition, the review identifies a range of underused but promising programming mechanisms targeting a more structural or policy level within gender-transformative programming. Critical gaps identified by the review in gender-transformative SRHR programming with men and boys relate to whole WHO SRHR domains as well as subdomains. The identification of these gaps can inform future programming and research in this field. The findings of this review are also contributing to developing a priority research agenda for engaging men and boys in SRHR programming that is ongoing by WHO’s Human Reproduction Programming. The central question going forward is not whether or not to engage men and boys in SRHR, but how to do so in ways that do no harm, promote gender equality and health for all and are scientifically rigorous.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the WHO Human Reproduction Programme Gender Advisory Panel for the contribution in setting the agenda for this review and attendees at a WHO convened stakeholders group in December 2019 comprised of researchers and programmers from the global north and south who assisted in reflecting on the findings and recommendations for directions in future research.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Soumyadeep Bhaumik

Twitter: @EimearRMcA, @AvniNAmin, @QUBSoNM

Contributors: ER-M, ML, AA, JH and ÁA designed review protocol and procedures. ER-M and KG conducted database search and removed obviously irrelevant records. ER-M and KG screened records for inclusion under guidance from ML. ER-M and KG conducted data extraction, including for quality appraisal under guidance from JH. MR, ML, KG and ÁA conducted initial analysis of the findings. ML, MR, AA, KG and ER-M drafted the manuscript. ÁA, JH and RK provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Funded by the Human Reproduction Programme (UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank collaboration) at WHO.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the 'Methodology' section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Any further data required are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.UN General Assembly Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [Internet]. A/RES/70/1, 2015. Available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030AgendaforSustainableDevelopmentweb.pdf

- 2.World Health Organization Gender mainstreaming for health managers: a practical approach [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501064_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruane‐McAteer E, Hanratty J, Lynn F, et al. . Protocol for a systematic review: interventions addressing men, masculinities and gender equality in sexual and reproductive health: an evidence and gap map and systematic review of reviews. Campbell Syst Rev 2018;14:1–24. 10.1002/CL2.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruane-McAteer E, Amin A, Hanratty J, et al. . Interventions addressing men, masculinities and gender equality in sexual and reproductive health and rights: an evidence and gap map and systematic review of reviews. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001634. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Distiller SR. Evidence partners. Ottawa, Canada, 2019. Available: https://www.evidencepartners.com/

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med 2009;21:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel. A guide to designing interventions. 1st edn Great Britain: Silverback Publishing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. . The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. . ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization (WHO) Reproductive health strategy to accelerate progress towards the attainment of international development goals and targets [Internet. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/general/RHR_04_8/en/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollock A, Campbell P, Struthers C, et al. . Stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews: a scoping review. Syst Rev 2018;7:208. 10.1186/s13643-018-0852-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellsberg M, Arango DJ, Morton M, et al. . Prevention of violence against women and girls: what does the evidence say? Lancet 2015;385:1555–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61703-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, et al. . A community mobilisation intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV/AIDS risk in Kampala, Uganda (the SASA! study): study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 2012;13:96. 10.1186/1745-6215-13-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowan FM, Pascoe SJS, Langhaug LF, et al. . The Regai Dzive Shiri project: results of a randomized trial of an HIV prevention intervention for youth. AIDS 2010;24:2541–52. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833e77c9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norris SL, Rehfuess EA, Smith H, et al. . Complex health interventions in complex systems: improving the process and methods for evidence-informed health decisions. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e000963. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricardo C, Eads M, Barker GT. Engaging boys and young men in the prevention of sexual violence: a systematic and global review of evaluated interventions. Sexual violence research initiative and Promundo. Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Small E, Nikolova SP, Narendorf SC. Synthesizing gender based HIV interventions in Sub-Sahara Africa: a systematic review of the evidence. AIDS Behav 2013;17:2831–44. 10.1007/s10461-013-0541-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy JK, Darmstadt GL, Ashby C, et al. . Characteristics of successful programmes targeting gender inequality and restrictive gender norms for the health and wellbeing of children, adolescents, and young adults: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e225–36. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30495-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcus R, Stavropoulou M, Archer-Gupta N. Programming with adolescent boys to promote gender-equitable masculinities: a rigorous review [Internet]. London, 2018. Available: https://www.gage.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Masculinities-Review-WEB1.pdf

- 21.Clark H, Coll-Seck AM, Banerjee A, et al. . A future for the world's children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020;395:605–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32540-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO Engaging men and boys in changing gender-based inequity in health: evidence from programme interventions. 76 World Health Organisation Library, 2007. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Engaging+men+and+boys+in+changing+gender-based+inequity+in+health:#0 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. . Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta GR, Oomman N, Grown C, et al. . Gender equality and gender norms: framing the opportunities for health. Lancet 2019;393:2550–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30651-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M, et al. . Questioning gender norms with men to improve health outcomes: evidence of impact. Glob Public Health 2010;5:539–53. 10.1080/17441690902942464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heymann J, Levy JK, Bose B, et al. . Improving health with programmatic, legal, and policy approaches to reduce gender inequality and change restrictive gender norms. Lancet 2019;393:2522–34. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30656-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lohan M. Advancing research on men and reproduction. Int J Mens Health 2015;14:214–32. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohan M, Aventin Á, Clarke M, et al. . Can teenage men be targeted to prevent teenage pregnancy? A feasibility cluster randomised controlled intervention trial in schools. Prev Sci 2018;19:1079–90. 10.1007/s11121-018-0928-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2020-002997supp001.pdf (127.2KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2020-002997supp002.pdf (81.9KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2020-002997supp003.pdf (291.3KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2020-002997supp004.pdf (193.3KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2020-002997supp005.pdf (445.7KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2020-002997supp006.pdf (119.3KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2020-002997supp007.pdf (84.4KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2020-002997supp008.pdf (321.9KB, pdf)